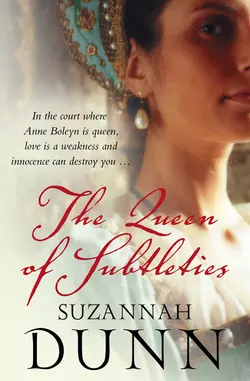

The Queen of Subtleties

Suzannah Dunn

A tremendously vivid, page-turning and plausible novel that depicts the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn, the most spirited, independent and courageous of Henry’s queens, as viewed from both the bedrooms and the kitchens of the Tudor court.Everyone knows the story of Anne Boleyn. Henry VIII divorced his longstanding, long-suffering, older, Spanish wife for a young, black-eyed English beauty, and, in doing so, severed England from Rome and indeed from the rest of the western world. Then, when Henry had what he wanted, he managed a mere three years of marriage before beheading his wife for alleged adultery with several men, among them his own best friend and her own brother.This is the context for Suzannah Dunn's wonderful new novel, which is about – and told by – two women: Anne Boleyn, king's mistress and fated queen; and Lucy Cornwallis, the king's confectioner, an employee of the very highest status, who made the centrepiece of each of the feasts to mark the important occasions in Anne's ascent. There's another link between them, though: the lovely Mark Smeaton, wunderkind musician, the innocent on whom, ultimately, Anne's downfall hinged…Suzannah Dunn has all the equipment needed for literary-commercial success: wit, a mastery of dialogue, brilliant characterization, lack of pretence, and good humour. The Queen of Subtleties adds to that mix a wonderfully balanced, strong story; Dunn has plumped for a fascinating retelling of one of the most often-told, most compelling stories of our islands' history. In doing so, she's turning from contemporary stories to historical fiction. The result is sensational.

The Queen of Subtleties

Suzannah Dunn

For my own little

Tudor-redheaded heir,

Vincent

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ue3c5df66-52e2-5b80-a45e-be8269bcdc61)

Title Page (#ue6c3c8c7-f162-5bef-9192-63d8d55ee21b)

Dedication (#ue58ca53c-1a3f-5072-82f9-fead78926e57)

Anne Boleyn (#u185e55e2-a735-5555-aafd-f0aba72faa68)

Lucy Cornwallis SPRING 1535 (#u075261d7-35d5-5daf-a03d-bb9203ad493a)

Anne Boleyn (#uf0301959-d43e-500a-a318-c57270beed93)

Lucy Cornwallis SUMMER 1535 (#u5f0f1b50-25ff-5024-9114-b80384f8c39e)

Anne Boleyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy Cornwallis AUTUMN 1535 (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne Boleyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy Cornwallis WINTER 1535-6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne Boleyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy Cornwallis SPRING 1536 (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne Boleyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Lucy Cornwallis SUMMER 1536 (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne Boleyn (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Suzannah Dunn (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne Boleyn (#ulink_8c737419-1715-5383-94a4-bac2e797287d)

Elizabeth, you’ll be told lies about me, or perhaps even nothing at all. I don’t know which is worse. You, too, my only baby: your own lifestory is being re-written. You’re no longer the king’s legitimate daughter and heir. Yesterday, with a few pen-strokes, you were bastardized. Tomorrow, for good measure, a sword-stroke will leave you motherless.

There are people who’d have liked to have claimed that you’re not your father’s daughter at all, but you’ve confounded them. You’re a Tudor rose, a pale redhead, whereas I’m a black-haired, olive-skinned, coal-eyed Englishwoman as dark as a Spaniard. No one has felt able to suggest that you’re other than your father’s flesh and blood.

You won’t remember how I look, and I don’t suppose you’ll ever come across my likeness. Portraits of me will be burned. You’ll probably never even come across my handwriting, because my letters and diaries will go the same way. Even my initial will be chiselled from your father’s on carvings and masonry all around the country. And it starts tomorrow, with the thud of the sword to my bared neck in time for my husband’s public announcement of his forthcoming marriage. As his current wife, I pose a problem. Not such a big one, though, that the thinnest of blades can’t solve it.

I want you to know about me, Elizabeth. So, let’s start at the beginning. I was born at the turn of the century. And what a turn, what a century: the sixteenth, so different from every one before it. The changes I’ve seen. Gone, quite suddenly, is the old England, the old order of knights and priests. England used to be made of old men. Men born to their place, knowing their place. We Boleyns have always prided ourselves on knowing just about everything there is to know about anything, with the exception of our place.

I was born in Norfolk. My mother is a Howard. Her brother is the Duke of Norfolk. I was born in Blickling Hall. I’ve no memories of Norfolk, but I’m told that the land is flat, the sky high and wide. So, from the beginning, it seems, I’ve had my sights on the horizon. The climate, in Norfolk, is something I’ve heard about: blanketed summers and bare, bone-cracking winters. Inhospitable and uncompromising, like the Howards. If the world had never changed, that would have suited the Howards.

Something else I’ve heard about the Howards: that the Duke, my Uncle Norfolk, has the common touch. At first, it seems a strange thing to hear about the last man in England to have owned serfs; but in a way, it’s true, because, for him, business is everything and he’s unafraid to get his hands dirty. No airs and graces. Land and money: that’s what matters to a Howard. My uncle has never read a book, and he’s proud of the fact. Ruthlessness and efficiency: that’s what matters. He’ll clap you on the back, one day; stab you in it, the next. No hard feelings, just business as usual. Never trust a Howard, Elizabeth, not even if you are one. Look where it got me, sent here to the Tower by my own uncle.

But I’m a Boleyn first and foremost. My father didn’t have the Howard privileges; he’s had to make his own way in the world. And he has; oh, he has: cultured, clever, cool-eyed Thomas Boleyn. England has never seen the likes of him. For a start, he has a talent almost unknown here: he speaks French like a Frenchman. Which has made him indispensable to the King.

We Boleyns have lived a very different life from everyone else, in this country; from everyone else under these heavy English skies, in their musty old robes and gowns, slowly digesting their stews. I lived in France from when I was twelve until I was twenty. I grew up to be a Frenchwoman, I came back to England as a Frenchwoman. There are women in France who are strong, Elizabeth, because they’re educated. Unlike here, where the only way to be a strong woman is to be a harridan. Imagine how it was, for me, to come back. For years, I’d been thinking in French. In France, anything seems possible, and life is to be lived. Even now, stuck in the Tower, a day away from death, I’m alive, Elizabeth, in a way that most people here haven’t ever been and won’t ever be. I pity their bleak, grovelling little lives.

Forget Norfolk, Elizabeth; forget the Howards, and old England and Catholicism and creaky Blickling Hall. Think Hever: the castle which we, the Boleyn family, made our home. Mellow-coloured, grand and assured. Perhaps you’ll go there, one day. I grew up there.

I was a commoner, but I became queen. No one thought it possible, but I did it. I supplanted the woman who’d been England’s queen for nineteen years, a woman who’d been born ‘the daughter of the Catholic Kings’. Her royal blood, her regal bearing, her famed grace and benevolence were nothing against me, in the end. She was a fat old pious woman when I’d finished with her. And England was changed for ever. It had to be done. I got old England by the throat, and shook it until it died.

Forget the ex-wife, for now, and let’s start instead with men. Because the story of my life—and now, it seems, my death—is largely a story of me and men. I like them. They’re easy to impress. I like male openness, eagerness. When I came to the English court, twenty and fresh from France, I fell in love with Harry, Lord Percy. Nothing particularly unusual in that. Women did it all the time. What made the difference was that Harry was in love with me. Twenty-two-year-old Harry Percy: that lazy smile; the big, kissable mouth. He dressed beautifully, but with none of the awful, old-fashioned flamboyance of his fellow-Englishmen. He was stylish. He could afford to be: he was one of the wealthiest heirs in the country. Which was another point in his favour.

Too easy-going for the saddle, and clearly bored by the prospect of tennis, he managed to be surprisingly popular with the men. He was a drinker, though, even then, which might explain it. He was somehow in the thick of things yet an outsider, an observer; and that appealed to me, newly arrived at court. Women loved him because he loved women: loved women’s company, women’s bodies. That was obvious, or at least to women. Men, clueless, probably didn’t see him for the competition that he was. We women instinctively understood that Harry was a pleasure-seeker and that if we granted him his pleasures, he’d savour them. Nevertheless, as far as I could discover, he had no reputation for sleeping around. On the contrary, it seemed that he was choosy, and unwilling to play the game of big romances. There was a take-it-or-leave-it air to him, a clarity of purpose and refusal to compromise that intrigued me and which I admired.

We circled each other for a couple of weeks, if ‘circled’ isn’t too active a word for Harry. I knew he’d noticed me. How could he not?—I was the new girl at court, wearing the latest French fashions. One late afternoon, when I was sauntering down a passageway, he stepped from behind a door to stop me in my tracks.

‘Walk with me,’ he said.

I said nothing—biding my time—and simply did as he requested, moving ahead of him through the doorway into a courtyard. The air was warmer than I’d anticipated. All day long, I’d been stuck indoors, doing my lady-in-waiting duties: playing cards, playing music. Outside, my eyes seemed to open properly, wide, and I felt my shoulders drop. I wondered, briefly, why I didn’t do this more often: get away, walk away.

We went towards the rose garden. ‘Back home,’ he said, breaking the silence, ‘in our gardens, we can smell the sea. I miss it. I feel so hemmed in, here.’

‘Oh, so, we’re walking and talking, are we?’

That shut him up. Good. Walk with me, indeed.

I had a question for him: ‘What did you think of the play, last night?’

He looked about to offer up a platitude, but caught himself in time. His shrug was pitched somewhere between non-committal and despondent.

I said, ‘Yes, but you laughed all through it.’

He was defensive. ‘We’re at court.’ Court: eat, drink, and be merry. Then came that smile of his: ‘And, anyway, so were you; you were laughing.’

My turn to shrug. ‘We’re at court.’

‘You were probably laughing the most of anyone. You’re very good at it, aren’t you.’

‘At laughing?’

‘At being at court.’

I said, ‘I don’t do anything by halves.’

In the garden, we sat on a bench, and I said, ‘Do you want to know what I really think, Harry Percy, about that play? And all the plays, here? And the music, the poetry, the food, clothes, manners?’ I sat back, crossed my ankles. ‘The gardens, even?’

Elbows on thighs, he stared at the ground. ‘You miss France.’

I snatched a petal, rolled it between my fingertips. ‘Don’t get me started. I mean it. Tell me about where you miss. Tell me about that home of yours.’

So, we started with the places we’d come from, and ended, hours later, with the books that were changing our lives. I remember asking him how he’d got hold of one of them, still banned in England, and him replying that he had his sources. I said that was a secret I’d like him to let me in on, when he felt able.

He took the fragment of petal from me and said, ‘Oh, I don’t envisage keeping any secrets from you.’

Dusk had closed over us. The palace was emerging as a constellation of lit porches, lit windows. Passers-by, spellbound by the half-light, talked less guardedly than usual. Harry and I were adrift from the rest of the world, yet right at the heart of it. On dark water, but in the shallows.

‘Anne?’ He sounded almost weary. The kiss was the barest brush of his lips, very slowly, over mine. And mine over his.

From that moment onwards, all that mattered to us was being together. Whenever I saw him across a room being sweet and attentive to some woman, I’d smile to think how, a little later, he’d have his mouth jammed against mine and I’d have him helpless. I lived in a permanent state of offering silent thanks to God for Harry’s existence. I couldn’t believe my luck; I couldn’t believe how close I’d come, unknowingly, to a living death of never having known him.

But I’d reckoned without the man who, in England, at that time, played God: Cardinal Wolsey. Wolsey had other plans for Harry, for various political reasons. He had plans for Harry’s family which didn’t include a Boleyn. He contacted Harry’s father, who came and gave him hell before dragging him home and marrying him to a woman he didn’t know and grew to hate. And he’s still there: up there in Northumberland, rattling around his ancestral home, childless and drunk.

The worst that happened to me was that I was sent home to Hever for the summer; but, of course, at the time, it felt like a fate worse than death. I spent that summer railing against Wolsey. It wasn’t long before I was joined in that by the rest of my family, because that was the summer when my father was made a peer—Lord Rochford—and it looked as if all his hard work was paying off until Wolsey forced his resignation as Lord Treasurer. Some rubbish about a conflict of interests. We Boleyns lost a salary, and Wolsey gained considerably in our animosity.

My father hadn’t been alone, kneeling to be honoured in that crowded and unbearably hot Presence Chamber. In front of him was six-year-old Fitz, the king’s bastard son. Dimple-faced, apricot-haired Fitz, brought from his nursery in Durham House on the Strand. He was made Duke of Richmond, then he sat for the rest of the ceremony on the royal dais at his father’s right hand. Officially welcomed to court. A month later, he was sent away again, but only because of the sweating sickness that drove into London’s population. Suddenly he was the owner of a castle up north, and recipient of an income from eighty manor houses. Travelling up there with him was a staff of three hundred, including a retinue of the very best tutors. My point is that he left court not as he’d arrived—as Betsy Blount’s lovely little boy, the king’s adored bastard boy—but as a kind of prince.

Of course, something similar had to be seen to be done for the princess. Ludlow, for her, in August. I didn’t see Fitz’s departure but I was there in the courtyard for Mary’s; I remember the vivid livery of those two hundred servants: blue and green. I was one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting. The queen was snivelling; she snivelled not only when the princess was taken away through the gates but for days afterwards. She was already becoming hard to please. Certainly the pomp of her daughter’s departure for Ludlow wasn’t enough to mollify her. She’d sat through little Fitz becoming a knight of the garter in April, but his peerage in June and the northern palace in July was, in her view, going too far. Wolsey dismissed three of her women for moaning about Fitz’s fortunes, and, worse, when she appealed, he refused to reinstate them. He had his uses, he had his moments. This was quite a shot across Catherine’s bows. And at a bad time, for her, too: the previously talked-of Spanish betrothal for her under-sized brat having been scuppered. My point is that quite suddenly, that summer, no one of any standing was taking Catherine seriously, nor did they look set to.

The story that everyone tells is that Henry divorced his long-suffering, sweet-natured, middle-aged queen for me, a younger woman, a dark-eyed, gold-digging, devil-may-care temptress. The truth is more complicated. Take my age. I was twenty-six when Henry fell for me. No girl, then. At that age, I really should have been married (and would have been—I’d have been Countess of Northumberland—but for Wolsey). I should have had children. At twenty-six, I was worldly, educated, ambitious. No wide-eyed plaything. Yes, I was younger than Catherine—but who wasn’t? She was forty, and seemed half as old again. It was all over, for her: the supposed bearer of heirs, she hadn’t been pregnant for a decade. She was a dead weight on Henry.

And what a weight! What she lacked in stature, she made up for in girth. With all the health problems that you’d expect. And no wonder: all those failed pregnancies. And no wonder they failed, with everything that she put herself through: the ritual fasting, the rising during the small hours to pray, the arduous pilgrimages, trekking in all weathers, for weeks on end, to Walsingham. All this took a toll on her spirits, too. She retreated among her pious Spanish ladies and their Spanish priests. Ceased to live in the real world. But, then, in many ways, she never had. I’ll not deny what people say, that she always had a kind word for everyone. The problem was in understanding it. Despite all her years in England, she was hopelessly foreign.

Why had Henry ever married her? Let’s not forget it was his choice. His father had died. Only just died, in fact, and there’s the answer: the marriage was Henry’s choice, his first; the first big decision of a new, seventeen-year-old king. Marrying Catherine, he all at once made his mark and a prudent political move, an alliance with Spain. And, anyway, Henry was a chivalrous man; big-hearted, and determined to do the right thing. He wanted to end Catherine’s misery: this kind, stoical, scholarly young woman, as he saw her, who was stuck in England, widowed, orphaned, and impoverished.

Anyway, there they were, years later: an odd couple. They even looked mismatched: she was the shortest woman at court; he, probably the tallest man in England. She waddled, whereas he was one of the best tennis players in Europe. She played cards with her ladies and then retired early to her bed. He partied until the early hours. She’d become an old lady while he was still a young man. She was looking forward to grandchildren, he was still hoping for heirs. There was, too, a fundamental difference in their attitudes to their faith. Henry’s relationship with God was robust, direct. He didn’t so much kneel before priests, in Catherine’s manner, as clap them on the back and challenge them to debate.

By the time that I was one of her ladies-in-waiting, her life revolved around that scrappy, priest-worshipping daughter of hers. A repulsively colourless child. It was ridiculous, the idea that the dwarf daughter of an old Spaniard from a defunct lineage could ever follow in Henry’s footsteps and rule England.

When Henry made his first move on me, my attention was elsewhere, albeit reluctantly. I hadn’t bothered with love since Harry Percy. I didn’t seem to have the heart for it. I didn’t quite have the heart for Thomas Wyatt. Don’t get me wrong, I was very fond of him: we’d been friends since childhood, and he was probably one of the best friends I had. But as a lover? I wasn’t convinced. His feelings on this matter were unequivocal, though, and he was making them known. Easy, if you’re a poet; and he was—is—one of England’s finest. Everyone was reading the poems. No one could understand my reticence. The consensus among my friends was that Tommy was the ultimate catch: dashing, and clever; sensitive, and baby-blond.

Henry made his first move with a gift: a sugar rosebud. Placed on my pillow. Someone had come into my room while I was out, and placed on my pillow a bud cast in molten sugar. Glassy; rosewater-tinted. I didn’t know it was from Henry until I read the tag, HR.

The presents that started coming were sometimes sugar, sometimes gold, and sometimes the sugary-gold of marchepane. Brooches, emblems, statuettes; stars, unicorns, Venus herself. Of course I thanked him for every one of them. But I hated it. With every ounce of sugar and gold, he must have felt that he was putting down another payment. And I wasn’t for buying. Eventually I decided that something would have to be said, and asked him for a moment in private. I hated it, that I had to go and ask and he got what he wanted: word from me.

I told him, ‘I don’t mean to seem ungrateful—and I’m not—but you should stop giving me presents.’

He said, ‘Should I?’ Amused. Lofty and amused.

Which annoyed me, although of course I was careful not to show it. Careful to act the gracious girl. Everything was always easy for him, nothing could ever compromise him: king, doing just as he pleased. ‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Oh? Why?’

The honest answer? ‘Because it makes things difficult for me.’

‘Oh.’

Yes. You, sailing through life, the rest of us eddying in your wake.

He switched tactics, to wheedling. ‘I like giving you presents.’

I commanded myself, Stay gracious. ‘And I like receiving them,’ and I did; of course I did, ‘But—’

An imperious wave of that jewelled hand, No buts. ‘They suit you. Gold suits you. Presents suit you.’ A grin. ‘You’re a presents sort of person.’

True. Damn. The hook, the reeling in.

He said, ‘They’re only presents.’ Then, quieter, ‘I have to give you presents.’ Then, ‘Please.’

It stopped nothing, my confrontation. On the contrary…The first letter came: I should explain…

And what was it, that he explained? Oh, that he’d never known anyone like me. That kind of thing.

So then I had to go to him about the letter. ‘Your letter—’

‘Yes?’

Well? ‘Thank you for it.’

‘Oh. And?’

And? ‘That’s all: thank you for your letter.’

He laughed as if I’d made a joke. ‘You’ll write back to me?’ He was still amused, but there was another look, too: his eyes clear and steady.

‘Oh. Yes.’ Damn. ‘Yes, if you like.’

‘If you like.’

I nodded while it sank in. ‘I do.’ But I had to, didn’t I.

A week or so later, when I couldn’t put if off any longer, when he’d mentioned it several times, I wrote that letter. I can’t, I wrote. I’m touched and honoured but I can’t. It’s not you, it’s me. I can’t be anyone’s mistress, not even yours.

He’d had mistresses; of course he had, married to Catherine. No surprise, there. The surprise was his discretion: Henry, the consummate showman, becoming low-key, cloak and dagger, keeping it all under wraps. There were times when everyone had suspected there was someone, but no one seemed to know who. A considerable achievement, such secrecy, at court. Other times, though, all was revealed and revelled in. Six or seven years before Henry wrote that first love letter to me, his mistress of the time had given birth to a baby boy. Mother of the king’s only son, Betsy Blount was fêted. Little Fitz was given a grand christening, with Cardinal Wolsey, no less, named as Godfather. Catherine attended, fixed with that serene smile. Gracious, people said. Stupid, would be another way of putting it.

All my poor sister achieved was to have Henry name a battleship in her honour. Fitting, I imagine people said: Mary Boleyn, they probably said, has a lot of sailors in every port; Mary Boleyn rides the swell.

Any mistress of his known to us—my sister no exception—was of a certain type. Giggly. Fun. Fun is what a mistress is; it’s what she’s for. Henry loved fun, in those days; nothing was more important, to him, so nothing was more important to us at court. Court seemed to exist solely for that purpose: Henry’s fun, day and night, summer and winter. Jousts, banquets, charades. Singing, hunting, gambling. And a mistress played her role. Knew her place, too. Fun while it—she—lasted. No misunderstandings. After Betsy had produced Fitz, in a residence provided for the purpose by the king, she never returned to court. Instead, she was married off to a man who was then favoured for various lucrative appointments. They’ve since had several children. My sister, too, in time, had had marital arrangements made on her behalf. Again, no problem: it was a happy marriage. No hard feelings, and no complications. For Henry, mistresses were mistresses, not potential wives. He had a wife.

I could never have been a mistress; it simply wasn’t my style. Don’t think that I couldn’t be fun with the rest of them; more fun than the rest of them. (Remember: nothing by halves.) But I could never have been discarded, like that; passed over, married off. All good things come to an end, Henry had said to my sister. But of course she’d had no say in when.

Henry said to me, ‘I don’t want you to be my mistress.’ We were sitting side by side in his private garden at Greenwich; a private moment at his request. ‘“Mistress”,’ he quoted, full of impatience, derision. ‘You’re not—you couldn’t be.’ He shook his head as if to clear it. ‘I don’t want a mistress; I want you.’ A shrug, helpless. ‘I want to be with you.’

That’s all very nice, I said; noble sentiments, I said; but—face it—what I’d be is a mistress. His long, blank look was unreadable; I anticipated a berating for being hard-hearted.

But he muttered, ‘I wish—’ Then closed his eyes, gave up, said nothing.

Never mind: it would pass in any case, I assumed; this crush on me. I was intriguing, he was intrigued: that was all it was. When nothing happened, he’d lose interest. But I was wrong: six months later, his infatuation was worse. There was no escaping him, not even when I retreated to Hever: letters came (Listen to me: there has never been and never will be anyone but you; I knew nothing until I met you); presents came (clusters of jewels, sugar-shapes, and haunches of venison); and on one occasion he came (dining with my family and staying overnight).

I wouldn’t have known those letters were from Henry but for the handwriting, the signature. They had nothing in them of the king that I or anyone else knew; our valiant, bombastic king. In these letters was someone at sea, in the dark.

Anne, yesterday you said…

Anne, please, may I just…?

His problem was that he’d never been in love. This was unknown territory, for him. He’d lusted after women, yes. And there’d been women whose company he’d loved: he was a man who loved company, and there had been women. His marriage was testament to his chivalry, if nothing else. But in love? At someone’s mercy? No, never. Not until me.

Not that this was enough, for me. Not enough to make me love him. Enough to stop me in my tracks, certainly, but to turn my head? No. All those letters, the walks in the gardens, the trysts that he requested: lovely though they were, they didn’t do the trick. During those first weeks, he confided in me: his family, his horses, music, books, buildings, faith, France and Spain. I did warm to him, I’ll admit, finding him mostly untouched despite the weight of the world on his shoulders. I listened, but deflected his questions. Keeping my distance, giving no ground.

It wasn’t that I didn’t like him. I did; by this time I liked him a lot. Funnily enough, what I liked in him was something that I loathe in everyone else: conservatism. It was understandable, in his case: part of the job. He wasn’t a natural at it, though, which made him perfect prey for me to rib. And I do love to rib. And with no one but him was there ever enough danger, for me; no getting beneath the skin. He loved to be ribbed, perhaps because no one had ever dared do it. He was ripe for it, and I was match enough for him.

Winter came and there wasn’t a single day, I don’t think, when it didn’t rain. Wolsey began 1526 cheerfully, though, with a springclean. His vision was a tidied royal household. One result was that my brother George lost his place in the Privy Chamber. Nothing personal, we were assured. He was just one of the six closest companions to the king to lose his job. Another, incidentally, was our cousin Francis. Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber down from twelve to six; just one of the cuts.

George was livid to have been so close to the centre and now be just another courtier. And—worse—guess who was in? Our brother-in-law, Mary’s new husband: inoffensive William. William Carey: the name speaks for itself. And nice Harry Norris: Groom of the Stool, now, and Keeper of the Privy Purse (and who could be closer to a constipated, spendthrift king?). And cute Franky Weston, with his then not-quite-broken voice: he was taken on as a page. No one could ever have said that my brother or cousin were caring or nice or cute; theirs were different strengths. Not that it made much difference, in the end. Because they’re all dead now, except Francis. Francis probably couldn’t die unless a stake were driven through his heart. If he had a heart.

Not a stake through the heart, but a splinter in an eye: dashing Francis lost more than his place in the Privy Chamber, that year. It happened at the usual Shrovetide joust. Henry had ridden into the tiltyard on Govenatore, who was new to him then and perhaps even keener than him to make an impression. The horse played to the audience; and Henry, though loving the challenge and the spectacle, had his hands full. Hannibal Zinzano, the horsekeeper, was, I noticed, watchful at the side. It wasn’t for Govenatore, though, that the crowd gasped; it was for what was embroidered in scarlet across the king’s gold-and-silver chest: No Comment. Recognition rippled through the crowd as Henry cantered around and people saw it or had it translated for them. Everyone knew what it meant: there was someone; someone new. They thrilled to it; it was a game to them, a laugh. His own smile, if there was one, was behind his visor. I don’t think he looked at me. He didn’t need to. Me, I had no such luxury. Like everyone else, I was there to spectate.

I couldn’t quite believe he’d done it. Indeed, I wasn’t quite sure what it was that he’d done. Didn’t know quite what to make of it. This declaring that he wouldn’t declare. This being so public about his privacy. Was I in on the joke, or was the joke on me? And then, as I watched him skittering around the yard, it was as if the joke unfurled. This is what I saw: that when he’d had the idea, he would have had to go to Mr Jaspar, his tailor, and discuss design and colour; and later, he’d have had to take delivery of it, and express his appreciation. And on the morning of the joust, he’d have had to arrive at the stables in it to do his best with Govenatore. What I saw wasn’t the seriousness of Henry’s pursuit of me. Quite the opposite. What I saw was that it was a practicality, sometimes; and others, almost an irrelevancy. It was a fact of his life.

I saw it, and I turned away; I turned to my little cousin Maria. She and Hal, Uncle Norfolk’s children, were at court for distraction from the worst of their parents’ separation, and they’d come along with me to the joust. Maria was snuggled up to me and I turned to check she was wrapped tight against the cold. Behind me came a distinctive crowd-gasp: low, blunt. I snapped back to see Harry Norris sprinting across the tiltyard. He was aiming for Henry and Francis, who were dismounted and fighting, or so it looked: Henry, trying to hold Francis’s visored head; and Francis, frantic, reeling, crouching, pushing him away. The horses stood by, helpless; Governatore, subdued. Henry’s shouting was becoming words, a name: Vicary; get Vicary. His surgeon.

Vicary’s good but he can’t perform miracles. In the days after the accident, Francis’s eye dried up and he never again removed the patch. It doesn’t seem to have hampered him. On the contrary. Somehow he looks more dashing with it. No one knew how it had happened, that splinter into Francis’s eye; not even Henry or Francis. Francis and I were good friends, back then; Francis and George and I. He was one of us. But that hasn’t been true for a while now, to say the least, and I have found myself wishing that I’d seen it and could relish the memory of it: that sly, stunning blow.

No comment? But those in the know, already knew. Privacy at court is scarce; and, of course, the bigger you are, the less you have. There was all the Dance with me, Anne; and only so many ruby earrings that I could explain away and sugar stallions that I could get the boys to eat. I was beginning to understand that my resistance was, to a great extent, irrelevant. Word was that the king was obsessed with Anne Boleyn; and no one cared about the details, such as which favours he was or wasn’t being granted. Why not play along with it, then? Go with it, get what I could from it? In a way, I didn’t have a choice. Or, that wasn’t the choice; the choice was not to end up as mother to some half-royal son and wife to some compliant, paid-off nonentity. That, I definitely wouldn’t have. But why not have some fun, for a while? I should have been Countess Northumberland, with my own vast household, but instead I was still in the queen’s rooms—all that praying and sewing—with no other suitor daring to raise his head. Why shouldn’t I have a little fun, perhaps, and some jewellery?

So, I went to Henry, one evening, after a year or more of his attentions; I went changed, resolved, chancing it. He didn’t register my change and was as unassumedly welcoming as usual: this king who, for my sake, was learning to live with so little of what he most wanted. I loved it, that evening: his guilelessness, openness. It dizzied me, made me tender. He was a sweet-natured man, in those days. His real nature is that of a soft-hearted man. At the end of that evening, when everyone had gone, I was still there. Me, the six weary musicians, and a whey-faced Franky Weston who was on duty to prepare Henry’s bed. Outstaying my brother and the others—cousin Francis, Harry, Billy—had taken some doing, even for me. Did I say evening? The small hours, more like. The banquet table was littered with sugar lemons, oranges, figs and walnuts that had been cracked open and chiselled away at, bitten into: shells, now, on a sugary sand. I told Henry that I’d like a word. ‘In private,’ I said, quietly.

He leaned towards me, expectant.

‘Strictly private,’ I whispered.

He indicated to the others: Skedaddle, would you?

Six lots of strings winding to a sudden silence, seven pairs of feet released across the carpet. He turned to me, pleasant; nothing too much trouble. I felt both solemn—this was some undertaking, this was it—and ridiculously giggly. I kissed him, and he took up the kiss and carried it on.

Later that night, that dawn, he asked me if I’d stay, and I said no. He didn’t mind; he was happy, it was a novelty, and there was everything to look forward to. Not long now, he was probably thinking. ‘You,’ he chided: indulgent, familiar.

Those early days were bliss, for me. It had been a long time since someone had placed his lips on my pulse. Too long since someone’s forefinger had run down my naked ring finger. Every evening, that summer, we stayed alone on the riverbank when the shadows were too blue for comfort.

But that was all we did. Every night, he asked me if I’d stay; every night, I said no. I wouldn’t be his mistress. Our relationship, as far as I was concerned, was a dalliance. I even liked the word, dalliance. And of course I liked the jewellery. But then, one day, sometime late in 1526, something happened. All that happened was that he walked into a room, smiling, and sat down. That was all, but that was it. He didn’t see me, when he came through that door. He came in with Billy Brereton, relating some tale that had Billy weak with laughter. I don’t think he saw any of us in particular, merely raised a hand to the room, Don’t get up. He strode past us all and slung himself into his throne; a long-limbed, loose-limbed man. He was grinning, pleased with himself: this king, this most kingly of kings, grinning like a boy. His hand flicked through his hair before he settled back and closed those gem-like eyes. Look at you, I thought, and knew, in that instant, that I’d been naive: we would have to spend our lives together. It was time, I saw, for him to move on. His marriage was over. Not that it was ever a marriage. Only ever a formality.

So, later that same evening, I asked him: ‘If you love me so very much—’

‘—Oh, I do, I do,’ punctuated with kisses to my shoulder.

‘—why don’t you marry me?’

He laughed, ‘Well—’ Stopped. Stopped laughing.

Yes. Precisely. You’re already married.

Shaken, he tried to make light of it: ‘Anyway, you wouldn’t marry me.’

‘Wouldn’t I?’

That smile was frozen; behind it, I could see, he was thinking fast. ‘A clever young girl like you.’

‘I thought there was no one like me.’

‘There isn’t.’

‘Well, then.’

He sat back, the better to see my face. ‘But you wouldn’t, would you?’

And now I allowed him a smile. ‘You asking?’

The next time he asked me to sleep with him, he tried to bolster his case by reminding me that we were going to be married.

‘When we’re married,’ I said, ‘I’ll stay.’

I could see that he barely believed it—that I was still refusing him—and was about to laugh me down, to protest long and loud. But of course there was no denying it: when we were married, we’d sleep together.

I pressed on: ‘Henry, Henry, listen: what you don’t need is another bastard.’

He might not have liked hearing it, but it was the truth. He said nothing for a moment, and then he conceded, ‘Well, it’d better be soon, anyway.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘that’s right, it’d better be.’

Why hadn’t it happened sooner? If it was the perfect match that I claim it was, a meeting of minds, why didn’t it begin as soon as we met? I’ve been thinking about that. I’ve been thinking about those six years we lived alongside each other at court before he asked his confectioner to make me that sugar rose. It wasn’t as if we hadn’t been well-acquainted. The Boleyns couldn’t have been closer to Henry: my father was Treasurer; my brother was a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, one of the elite attending to the king; my sister doing the same, but differently, for her year or so as royal mistress. I suspect it was for precisely that reason: Henry was always there, and he was everything; defining our lives, our lives revolving around him. Because of that, he was almost irrelevant to me. I was busy, in my early twenties, with my girl-life. Smitten with a pretty-boy. Henry was a man, in his thirties and into his second decade of marriage. Moreover, of course, he was the king. For me, he wasn’t a potential lover; it never crossed my mind. And if it had, Henry wouldn’t have appealed to me. Oh, he impressed me, yes, of course. And intrigued me. But the sheer spectacle of him…Well, that was what it was: spectacle. He wasn’t for falling in love with.

Henry didn’t divorce Catherine because of me. For me, yes; in the end, yes. But not because of me. He was thinking of doing so anyway, in time, probably to marry some French princess. Wolsey was keen on that idea. He was late to catch on to what was happening, was know-all Wolsey. Even though he did know about me. Or thought he did. But what he knew—or thought he did—was that I was the king’s new bit on the side. I’d been suitable to invite again and again to lavish dinners at his gorgeous Hampton Court (a thousand rooms, a thousand crimson-clad servants) on the arm of the king…but I was nothing more. As wife-to-be, I rather crept up on Wolsey. But that’s because he’d been kept in the dark. Replaced as the king’s confidant. By me, funnily enough, as it happens. Right-hand man replaced by bit on the side: no wonder he was caught off-guard.

Leviticus 20, verse 21: And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless. Henry’s wife was his—had been his—brother’s wife, briefly, before his brother’s death. The marriage had been deemed a non-event because, according to Catherine, Arthur hadn’t been up to doing his husbandly duty. The problem was, Henry and Catherine still had no children. Well, no sons. There was of course the daughter, pathetic example though she was. A mis-translation, said Henry, turning sudden specialist in Hebrew: it should read ‘sonless’. Henry and Catherine’s lack of a surviving son, he decided, was God’s judgement on a sinful marriage. That’s what he said, and he believed it; he talked himself into believing it and from then onwards his fervour was unshakeable.

I didn’t suggest Leviticus to him. Why would I? In my view, he had grounds enough to rid himself of that Spaniard: she’d proved no use at all, and now—aunt of a rampaging emperor—she was a liability. And Leviticus was no discovery for him: he’d quoted it, years before we met, in his book on Luther. As for the dubious validity of his marriage: he knew that it had been an issue at the time; and he knew, too, that for some the misgivings had persisted. A French bishop, for example, had queried the brat’s legitimacy during a round of marriage-brokering. None of it was news, and none of it—yet—was due to me.

Like anyone else at court, I’d heard speculation from time to time about a royal divorce: Why doesn’t he just get rid of her? Marriage breakdown and separation happens all the time. Sometimes an annulment, or a divorce. And in this particular case? Our lovely young king married to a babbling old nun? Worse: a babbling old Spanish nun, when England’s focus was firmly on France. Her being a Spaniard could be overlooked, though; she’d been here a long time. What really mattered was that distinct lack of live baby boys.

If Wolsey had had his way, he’d have got Henry his divorce and then shipped in some French flesh to produce princes, and to have French friends and deck up for functions. Well, I could do that. And more. And I wouldn’t have to be royal; Elizabeth Woodville hadn’t been, and it hadn’t stopped her marrying Edward IV. And anyway I wasn’t completely un-royal; I had that smidgeon of Plantagenet blood. (Didn’t we all, though. All except Wolsey, that is.) Surely I could produce sons—my useless sister had just managed one—and I was practically French, I’d done a long stint at the French court and was liked by anyone, there, who was anyone. There was another way in which I was queen material, too: no one in England rivalled my dress sense. I dressed the part. So, I’d do. Better still, I’d be no homesick half-wit. But best of all, this was my country and I had plans for it, along with the guts to see them through. And one of those plans was going to make me very popular with just about anyone who wasn’t Wolsey: I wanted rid of Wolsey.

I’d say Wolsey was too big for his boots, but let’s not beat about the bush: what Wolsey was too big for was England. Never before had there been a man in England so rich and powerful who wasn’t a king. Moreover, this was a man who wasn’t anything at all, not originally: a nobody turned cleric, a butcher’s boy become cardinal. The nobles had a thing or two to say about that, behind his back.

I suppose that’s why Henry trusted him with the kingdom: no friends to favour; no claim to the throne. Henry’s talent—the best talent of all—is for recognizing other’s talents. I wonder, now, if I should include myself in that. Did he see that I’d flinch at nothing to rid him of that used-up wife? He recognizes talent and he trusts: he trusts absolutely; right up until when, suddenly, he doesn’t. It’s Thomas Cromwell whom he trusts now: Cromwell, the next and even better Wolsey. Wolsey’s talent had been running the country for Henry. And serious statesman though Henry is…well, when he was young, his passion was for the good life. He’d do a certain amount of work, but then he’d want to go hunting or dancing. Wolsey would stay behind and pick up the pieces. And build palaces from them.

If anyone was a match for Wolsey, glorified butcher’s boy, then it was me, king-favoured granddaughter of a merchant. I knew where he was coming from. He, however, didn’t even know I was coming. Me being a woman, he didn’t see me coming. And I was ample match for him: no chinless wonder; no Stafford, who, four or five years earlier, had assumed he could click his fingers and have the nobility collect quietly behind him while he asked the Tudors a few awkward questions about their lineage. When Stafford clicked his fingers, Henry overheard. Henry did some clicking of his own—for quill, ink, warrant—and Stafford went to the block. This, from a king not given in those days to bloodshed; a king who loved to be loved. Stafford’s execution had left them all—even my Uncle Norfolk—sulking, subdued. But me, no. Stafford was history for me, I’d never known the man and wouldn’t have liked him if I had. He was no loss for me: one more English aristocrat peering down his pox-eroded nose at the likes of us Boleyns. What had happened to Stafford was no warning to me. I wasn’t about to lose my nerve.

Lucy Cornwallis SPRING 1535 (#ulink_c4f1516e-ba4d-50d3-b772-92a9c1932f4a)

The door’s opening, and there’s someone in the doorway. The someone’s asking, ‘Miss Cornwallis?’ Male, young, not a voice I know. Bad timing: I can’t take my eyes from this pan of boiling sugar, it’s just about to reach the crucial point. He shouldn’t be knocking at the confectionery door; he should know better. There’s delicate work going on, in here; everyone knows that. What’s the matter with these boys, knocking on this door all day long? ‘Richard’s not here,’ I tell him. ‘Can you shut the door, please?’ I can’t have the temperature drop; and it’s barely spring, outside.

He obliges. But he’s still here. True, I didn’t actually say, With you on the other side of it. Swiping the pan from the flame, I glimpse him. Glossy black hair; pale-faced, kid-pale; dark eyes. I settle the pan in a basin of water; and through the hiss of steam, I hear him saying, ‘You’ve a sore throat.’ Concerned. For me, by the sound of it; not for himself, for the prospect of contagion.

‘Dry,’ I clarify; feel obliged to. ‘Sticky. Comes of working in here.’ Our confectionery kitchen is purpose-built, here, at Hampton Court: we’re on the first floor above the pastry ovens. Good for sugar, not so good for me. ‘And from the sugar.’ Sugar, powdered, gets everywhere. In my hair and down my throat. When I glimpsed him, just now, it was through sugared eyelashes. ‘Look,’ I ask him, ‘if you find Richard, can you tell him to get back here?’

He draws breath, as if he’s about to say something, but I hear no more.

Good. I’m not passing messages.

And he goes. Gently closing the door. Not a typical Richard-visitor, in that respect.

Time to take the pan to the marble slab, to drop and settle the syrup, bit by bit, into the warmed, oiled moulds. Three dozen Tudor roses, each the size of the circle made by forefinger and thumb. Old-fashioned sugar plate, the boiled-up kind. The temperamental kind. Why isn’t Richard doing this? I could be getting on with something else. It’s not as if there isn’t a lot else for me to do.

And lo and behold: Richard, slipping into the room as if his absence has been of no consequence. In his twenties, but acting as if he’s still in his teens. An odd mix, Richard: worldly and other-worldly. Whatever he says—and whatever I feel—I’m not in fact old enough to be his mother. Yet it’s as if there’s not just a generation’s difference between us, but a lifetime’s. He steps out of his clogs and, shoeless, pads across the warm oak floor. Standing a head above me, he looks down over my shoulder at the glistening, amber roses. And keeps looking. Which makes me uneasy. I scan the roses for imperfections—bubblings, darkenings—and wonder how it happened that he checks up on my work.

Now he has his back to me, bending down, putting his leather slippers on. ‘What needs doing?’

‘You know what needs doing. Because you did half of it, earlier.’

We both look at it: a Marchepane, an embossed disc of marzipan as big as the king’s biggest dinner plates. Not long out of the mould, it’s cooling. But if Richard isn’t quick, it’ll be too cool and the goldleaf won’t stick.

‘Did we get the goldleaf?’ he asks.

‘I got the goldleaf, yes. I need this pan washed—where is Stephen?’ A glance out of the window reveals nothing but wet cobbles and a smile from the yeoman guarding the spicery office. ‘Oh—’ I remember—‘did he find you?’

‘Stephen?’ Richard’s peering into Kit’s abandoned mortar; shifting the pestle among the grains, his eyes closed and head cocked.

‘No. That boy, just now.’

‘Who?’ He touches a fingertip to the inside of the mortar, then raises the hand, palm upwards, into the light, as if setting something free.

‘He didn’t, then.’

‘Who?’

‘I don’t know. Someone came looking for you.’

He dabs the forefinger into the basin of water, rubs it with his thumb. ‘What’d he look like?’

‘Nice-looking.’ Because it occurs to me that this was what he’d been.

‘Nice-looking?’ Richard regards me admiringly. He enunciated the expression as if it had never been used before. ‘Well, could have been anyone,’ he concludes, breezily. ‘You know what I always say: if he wants me badly enough, he’ll come looking again.’

‘Is that—’ I nod towards the mortar—‘up to it?’ Down to it: ground sufficiently for today’s purposes.

‘Of course. Kit’s a good man.’

True, but Richard rarely says so. He can be a hard taskmaster, even though it isn’t his job to be any kind of taskmaster at all; it’s mine. I say, ‘You’re in a good mood.’

He’s browsing along the shelves of spices, doesn’t look at me. ‘Yeah, well,’ is all he says.

And yet again I wonder: how come he’s so familiar with me, and I know so little about him? I brought him up from an orphan, an under-sized urchin living on his wits. I made him who he is, now: confident, respected assistant to the king’s confectioner. (Equal, really: face it. Equal, now, in skill. Rival, if he so chose.) But in so many ways he’s a mystery to me. Sometimes I can barely believe that we’ve spent a decade living alongside each other, working together all day every day and then spending our nights in adjacent lodgings. All these years living like sister and brother. Perhaps that’s why he still captivates me. I find myself watching him when he’s absorbed, when a peculiar clarity comes into those river-green eyes of his and everything that is Richard dissolves away in them, leaving them with a life of their own. For all the contrived appearance to the contrary, he’s deadly serious about his work. That’s something I do know about him. Something I’ve learned. It’s probably the only aspect of life that he’s serious about. I’m probably the only person who ever gets to see beyond his flippancy.

When he arrived, a decade ago, to chance his luck in the royal kitchens, he was just one of so many boys hanging around in hope of paid work. Who could blame them? Doubtless they’d heard how there were wages to be earned as well as two meals a day and, at night, space to curl up near the massive ovens. A job in the royal household is a job for life, and it’s a good life; and when we’re not up to the job—sick, or old—we’re still paid. Less, yes, of course, but enough to keep body and soul. It’s hard work, in the kitchens, but worth it. If the boys couldn’t find paid work, they worked anyway and made it pay: muscling in on household life, and trading in the leftovers which were supposed to go to beggars. They made lives for themselves, even if they were barely clothed. My own little kitchen had a bevy of such boys, always coming and going. I’d inherited a situation which had been gaining ground, unchecked, for years. I didn’t like it; didn’t like the chaos. I only managed any serious work after the boys had gone away to sleep and before they returned in the mornings. And then, inevitably, there was the filching. The sticky fingers. The Chief Clerks hold me personally accountable for the most valuable substance in all the kitchens, but how could I watch every grain? How could I supervise hordes of hungry, destitute children around sugar?

The day I came across Richard, I was doing just as I was doing a moment ago: boiling sugar syrup. One of the boys wanted my attention. Mrs Cornwallis? Mrs Cornwallis? Mrs Cornwallis? I was very busy; surely that was obvious. No? Well, I’d make it obvious, by ignoring him. Not that I had much choice—I couldn’t take my attention from the sugar—but I could have spoken. I could have said, Hang on, please, Joseph, or whoever. Just a moment, John. Missuscornwallismissuscornwallismissuscornwallis—Before I knew it, I’d shot round and was glaring at him, furious with myself for having been distracted. Heat bloomed in the pan behind me, and there was a coppery flash as I whirled back to it. It was gone from the charcoal brazier; it was sinking into a basin of water. I was there, instantly, assessing the damage: none. It was saved, it was saved. I took a moment to appreciate that some kid had done it. Some boy had not only judged the critical point—and from across the room—but had acted without hesitation, snatching a weight of flame-hot and explosive gold from the king’s own confectioner. Then he’d relinquished it, immediately; he was already busy wiping a workbench. He didn’t look at me.

I asked him: ‘Who are you?’

Strange eyes: green, slanted. Elfin. He could have been any age between seven and twelve. ‘Richard.’ He shrugged.

‘Richard,’ I repeated, stupidly, because I didn’t know what else to say; where to start. And, anyway, he was wiping again. His mousy hair was a little matted at the back, I noticed.

Less than a fortnight later, we were visited by a representative of the Cofferer. A not unexpected visit. Word was that Cardinal Wolsey had decreed a great clean-up, a great head-count in the household: enough is enough; time’s up for hangers-on, and hangers-on of hangers-on. When the representative had finished remarking on the fact that I’m the only woman working in the kitchens, which was hardly news to me or to anyone else, he explained his mission: ‘When I’ve finished, there should be around two hundred people working in the kitchens. Not…’ he faltered. ‘Well, not more.’ He said, ‘Basically, anybody who’s not somebody has to go.’ He looked at Kit. ‘Obviously the yeoman here is somebody.’ Kit smiled. Kit, in his yeoman’s green. What Kit is, actually, is a pair of hands, and a very useful, capable one, at that. The man asked me. ‘And you have a groom?’

Someone to wash up and run errands, yes. ‘Geoffrey,’ I said. (These were the days before Stephen; the days before Geoffrey moved on up in the world into the Privy Kitchen and Stephen stepped into his shoes.) ‘He’s at the scullery.’

‘And…these.’ It might have been intended as a question but it fell flat, leaving us facing them. The boys. Seven or so of them; or ten, perhaps. They looked back, as nonchalant and calculating as cats.

I sighed. Their days were numbered, here, and they knew it. Turning so that they couldn’t see me, I said so that they couldn’t hear me, ‘Richard has to stay.’

‘Richard?’ The man frowned; he wanted no difficulties.

I lied, ‘He’s my assistant.’

The man consulted his notes.

I came clean. ‘He’ll be my assistant,’ I said, and folded my arms, which was, and still is, the only way I know to stand my ground. ‘Confectionery is skilled work,’ I proclaimed; I was trying hard, now.

He sighed. ‘Richard who?’

I had to turn around and face them all; to brazen it out. I half-turned, and quietly asked Richard: ‘Richard who?’

He shrugged.

I looked back at the man, and shrugged in turn.

The man sighed, frowned, and opened his mouth to say something.

‘Cornwallis,’ I said.

It’s the nice-looking boy, again; the black-haired one who came here the other day. Luminous complexion.

‘He’s not here.’ I roll my eyes; more biddable, today.

‘Richard?’

‘Yes. Richard. Not here.’ Seeds scuttle beneath my fingertips—fennel, aniseed, caraway, coriander—as syrup dries around them, making sugar hailstones. ‘Any message?’

‘For Richard?’

‘Yes.’ What is this? ‘For Richard.’ I spoon more syrup into the pan, and the stranger raises his eyes back to mine. Presumably he hasn’t ever seen this before: a pan swinging on cords above a brazier. His eyes aren’t dark, I see now; they’re shadowed by dark eyelashes, lots of them. The eyes are blue. I nod at the pan. ‘There’s a good reason for it. Maintains an even heat.’

He nods, still wide-eyed.

This is no kitchen-lad: no yeoman’s uniform, and his clothes are much better than a groom’s. Much better than any household employee’s, it occurs to me. But nor is he a courtier. He doesn’t have the pristine, polished appearance. Doesn’t have the strut; there’s no trace of it in his stance. He’s wearing battered clogs. What’s his link with Richard? What on earth does Richard—fastidious Richard—make of him?

He says, ‘I don’t know…Richard.’ It’s a gentle voice.

‘Well, he’ll be back later, if you want to try again then.’

‘No—’ the eyes dip away into a smile, ‘I mean, I’m not here to see Richard.’

‘Oh. Oh. Sorry. It’s just that…well, everyone always is.’ We exchange smiles, now. ‘Can I help?’

This is somehow unhelpful in itself, because he freezes, lips parted. Mute. I can wait; I’ve plenty to occupy me. Comfits take hours; hours and hours of this, to get them perfectly round.

‘This is stupid, probably, but it’s you I’ve come to see. I’ve been at the king’s banquets and feasts, and I’ve seen…’ He stops, shuts his eyes briefly but emphatically; a lavish blink. ‘You remember the Saint Anne you made?’

Well, of course I do; it took me long enough. This man, this boy, has been at the king’s banquets and feasts? He’s a server, that’s what he is. Must be. A privileged young man putting in his time at the tables before moving on to better things. But presumably not in those clogs.

‘And that leopard? It’s just that they’re so…’ He looks upwards, skyward.

So…?

‘Lovely.’ His gaze back to mine. ‘Detailed. Perfect. And I wanted to meet the person who made them. Everyone talks about you. The king—’ He leaves it there: enough said.

‘The king’s very kind.’ And it’s true.

‘I just wanted to meet you, and to see how you do it.’

What a strange request: everyone’s very interested in the finished articles, but I’ve never come across anyone who cares how they’re made. ‘Well, I’m afraid, as you can see, it’s not really happening today. Today is comfits.’

A wince of a smile from him, as if it’s his fault. He glances appreciatively around the room, making the best of it now that he’s here.

‘If you come back on Friday, I’ll be sculpting.’

‘Right.’ He snaps to attention. ‘See you on Friday.’

I’m saying, ‘Well, only if you want to,’ but he’s already gone.

This next time, funnily enough, they pass each other in the doorway. When he’s shut the door, Richard asks me, ‘What was Smeaton doing here?’

‘Smeaton?’

He comes over to look at what I’ve been doing.

‘His name’s Mark.’

‘Yep. Mark Smeaton.’

‘How do you know who he is?’

He saunters away with a smirk. ‘I know anyone who’s anyone, Lulabel.’

‘But he’s a musician.’ That’s what he’s just told me.

He stops, turns back to me. ‘A musician?’ He looks amused. ‘Is that what he told you?’

My heart flounders: what does he mean? what’s going on?

‘He’s the musician, more like. The up-and-coming musician. In the king’s opinion.’ He ties his apron around his waist.

‘Mark?’ The Mark who was in here, just now?

‘Smeaton. Otherwise known as Angel-voice.’

Angel-voice? ‘Is he?’

‘Well, no, but he could be.’ He’s washing his hands. ‘His voice is what he’s famous for.’

‘Famous?’

‘Well, kind of. Known for.’ Slant-eyes sideways. ‘Let’s face it, it isn’t for his dress sense, is it.’

Sometimes Richard is so shallow. He has a lot to learn about what matters in life.

‘Anyway,’ he dries his hands on his apron, ‘what was he doing in here? Ol’ Angel-face.’

Angel-face. Angel-voice, Angel-face. Which is it? I don’t seem able to see him, hear him, now, in my memory, as if Richard’s names for him have brought me up too close. ‘He wanted to see me.’

‘What about?’

‘Nothing. He wanted to…see what we do. How we do it.’ It sounds ridiculous. Spoken, it’s become ridiculous.

Richard is craning along a shelf of moulds. ‘Thinking of becoming a confectioner, is he? Nice little sideline for when his voice breaks.’

Right, that’s enough. I reach around him, on tip-toe, and swipe a tiger from the shelf: ‘This one.’

He whips around, his weird eyes on mine. Amused, again. ‘What do you get up to when I leave you in here? Do Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber usually drop by?’

And now he’s getting carried away. ‘No, but he’s not a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, is he. He’s a musician.’ As if any musicians ever come in here. As if anyone at all ever comes in here, when Richard’s not around.

‘Yes, and, Lulatrix, he’s a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber.’

But this is absurd: what does Richard take me for? ‘He’s a musician. You just said so. Which means he works. Doesn’t joust, all day long. And he’s…he’s nice.’

‘Oh, come on, Lucy. You, of all people, should know that our dear good king can be…unconventional, shall we say, when it comes to staffing. He likes talented people. Recognizes talented people. Likes them around. And he loves music. Is there anything he loves more than music? Well, except…well, except a lot of things.’

‘Mark’s really a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber?’

Richard’s busy checking that the mould is clean, dry, undamaged. ‘The king likes him; I mean, really likes him. God knows why, but he does.’

‘What d’you mean, God knows why?’

‘Well, he’s hardly Privy Chamber material, is he.’

And isn’t that good? Perhaps not in Richard’s view, but certainly in mine. I lose track of who’s in the Privy Chamber, but anyway they’re all the same in that merry band: top-heavy with titles, too handsome to be true, too clever for their own good and a law unto themselves.

I ask him, ‘How do you know all this?’

He grins. ‘I have friends in high places.’

For once, I’m not going to let him get away with his usual flippancy. ‘Who?’

He seems genuinely surprised; he puts the mould aside. ‘In particular? At the moment?’ He means it: it’s a proper question.

I nod.

‘Silvester Parry. One of Sir Henry Norris’s pages.’

‘Silvester.’ Unusual name.

‘Silvester,’ he agrees, as if I’m a clever child.

‘Well, you’re going up in the world.’

Something amuses him; he’s about to say, but seems to think better of it.

Sir Henry Norris, I’m thinking. Isn’t he the king’s best friend? A Gentleman of the Privy Chamber; I do know that. And the one who is indeed a gentleman, by all accounts. Or perhaps by Richard’s account; I don’t remember where I heard it. Isn’t he the widower? With the little boy? ‘Is he a recent friend? Silvester?’

‘Very recent. But very good.’ Richard, gathering ingredients, laughs even as he’s turning his nose up at the remains of my gum tragacanth mix.

‘Good,’ I say. ‘Good.’ And I made a friend, today.

He’d hesitated—Mark—as before, in the doorway, and said, ‘Well, here I am.’

Presumably it seemed just as odd to him as to me that we’d made the arrangement. If ‘Friday’ could be said to be an arrangement. It seemed to have worked as one, though, because—as he said—here he was. And early. Calling to him to come in, I tried to make it sound as if I did this all the time: welcomed spectators. As he crossed the threshold, he took a deep, slow breath.

‘The smell in here…’ He sounded appreciative, and full of wonder.

I confided my suspicion that I can’t smell it, any more; not really, not how it smells to an outsider.

He looked stricken, on my behalf. ‘You need a stronger dose. You’ll have to stroll through some sugar-and-spices orchards; perhaps that’d do the trick.’

‘Yes, but first I’d have to go to sea for weeks on end.’

‘Ah. Yes.’ He made a show of shuddering.

That, we were agreed on. I indicated for him to draw up a stool, and he settled beside me. The scent of him was of outside: his lodgings’ woodsmoke and the incense of chapel; and, below all that, was…birdsong. Birdsong? Morning air. He smells alive, I thought, and presumably I smell preserved. Even when I do manage to get outside, I’m usually only crossing the yard between my lodgings and here. The air in the yard throbs with baking bread, brewing and roasting. ‘And I’m not sure about those “orchards”,’ I said. ‘I’m not sure that sugar, when it’s growing…well, that it’s anything like what turns up at Southampton. Unless it grows in blue paper wrappers.’

‘Oh.’ He glanced around, expectantly, presumably looking for them, our conical sugar loaves. I broke it to him that he wouldn’t find any, here. They’re locked in a trunk in the spicery. Even I have to apply to the Chief Clerk for my requirements. Then he asked me about spices, about whether they grow. ‘I just can’t imagine them growing,’ he said.

I explained that they’re seeds, mostly.

‘Yes, but that’s it: I can’t imagine the plants.’

I considered this. Reaching into a bowl, I took a rose-petal. With it on my palm, I said, ‘I wonder, if you’d never seen a rosebush, whether you could imagine where this came from.’ I passed it to him.

He held it and then rubbed it slowly between forefinger and thumb. It kept its shape, bounced back from every fold; effectively remained untouched. ‘I’d never thought of them as tough,’ he said, and he was as surprised as I’d known he would be. ‘They’re not really delicate at all, are they.’

‘Not at all,’ I agreed. ‘But nor is a rose-bush.’

It wasn’t until then that we exchanged names: ‘I’m Mark, by the way,’ he said.

‘Lucy,’ I said. Well, why not? Richard calls me Lucy.

He thanked me for allowing him in to watch, and I asked, ‘Didn’t you ever watch anyone making confectionery, when you were little?’ His mother, if he had a mother. If she lived until he could remember her. Few women are so grand that they don’t cook, and all of them aspire to confectionery.

‘I didn’t have that kind of childhood,’ was his cheerful answer. ‘I was a choirboy.’

Oh. So, another orphan of a kind.

‘Here, usually.’

‘Hampton Court?’ And then it sank in.

But he said it anyway: ‘I was in Cardinal Wolsey’s choir.’

I was careful to echo his even tone when I said, ‘How things change.’ Which could, of course, be taken to refer to the palace itself and not the cardinal’s demise. And it partly did, because what is Hampton Court other than endless building-work? It’s been five or six years, now, since the king took it over, and will he ever stop? Wine cellars are the latest addition to our kitchens; massive, vaulted wine cellars. It’s said that the palace was colossal in the cardinal’s time. What’s the word for it now that it’s twice the size?

He said, ‘Some things change, others don’t: I’m still singing.’ He smiled. ‘Rather lower, though.’

He’s a chorister, still. Then I’ll have heard him, in Chapel. His is one of the voices making that shining wall of sound. It’s a strange feeling that those voices cause in me; coolheaded, everyday me. As if the coping that I’ve been doing is nothing; as if everything I am and everything I do is nothing, a sham. And isn’t that wonderful, in a way? Isn’t it a kind of relief?

When he’d gone, I decided to take a break, a stroll. I don’t get enough air. I walked past the chapel, but it was silent. Walked on into the rose gardens, and, there, savoured the fragrance. It’s the faintest of scents, but steady. No muskiness, no headiness to it. Just a single, clean, high note.

Rose shapes, though, are anything but simple. Here in the kitchen we have stamps and flat moulds of roses that are regularly-petalled. Tudor roses. And we have one old mould of a rosebud which yields a rosebud-shaped pebble of sugar. But real roses have intricate whorls of petals as individual as fingerprints. If I were to try to make a faithful reproduction of a rose, I’d have to build it petal by petal, modelling each petal by hand; each one bowed and tapered between fingertip and thumb.

‘By the way,’ Richard says, ‘if you want the latest royal gossip, it’s that Henri fait l’amour avec Meg Shelston.’

‘Thank you, Richard. I don’t.’ And I wish he wouldn’t be so disrespectful. Someone will hear him, one day; someone other than me. And his ridiculous attempts at code: I should feign ignorance. He’s persuaded someone to teach him a little French, over the last year or so. Regrettably, not to broaden his mind. He’s aware that I know some French, but not how much. And in fact it isn’t much. I trained with a French cook, and I know what people say about the French but he really didn’t have much time or use for expressions like fait l’amour. I can work it out, though. What I don’t know is, who’s Meg Shelston?

‘And Le Corbeau isn’t best pleased about, to put it very, very mildly indeed.’

Initially, Le Corbeau stumped me. He had to tell me that it’s a translation of a name for her that’s been in use for a while. According to some people, he says, it was Cardinal Wolsey’s own name for her, in his time; except that the cardinal’s name was The Midnight Crow, and although Richard can manage minuit, it makes it a bit much. I’m surprised to hear Richard using such a name at all; because, until recently, he was all for her. ‘Richard, sometimes I think you like to make something out of nothing.’

‘Yes, I know. I know that’s what you think.’ He’s offended that I’ve rejected this titbit that I never asked for.

Which annoys me. ‘Richard, why would he? Think about it: he turned this country upside-down and re-wrote all the rules, two years ago, just two years ago, so that he could marry—’ What do I call her? I don’t like calling her the queen. ‘So that he could marry. He went through all that—took us all through that—and now they have the lovely little princess—’ Say what you like, she’s a treasure; born under a waning moon, so the next one’s bound to be a boy. ‘Why would he bother with any…Meg?’ I do honestly think, sometimes, that Richard lives in fairyland.

‘Well…’ He stops, seems to abandon whatever point he was about to make, and merely says, pleasantly, ‘You don’t understand men at all, do you, Lucy.’

I knew he’d come again. Somehow, though, I’m still surprised to see him. A shock: that’s how it feels; a jolt. This time, Richard’s here; but absorbed, sculpting. Hungover. Choosing not to respond to the knock at the door, but now glancing up, apparently goodnatured and almost smiling. ‘Morning, Mr Smeaton.’ So casual, yet somehow making everything so awkward. Well, that’s a Richard-speciality, and I must rise above it.

‘Richard.’ I indicate him to Mark: an introduction. A flicker of amusement between us: Richard seems to have become our private joke; Ah, Richard, at last.

‘…Cornwallis,’ Richard adds, with the same goodnatured near-smile that isn’t either goodnatured or a smile. Never mind: no one else knows the difference.

‘Mr Cornwallis.’ Mark nods.

I’d like to say, He’s not my son; I’m not his mother. I don’t know how to address Mark, now; after all the Mister this and Mister that. Did I imagine that he ever introduced himself as Mark?

He’s saying, ‘I hope you don’t mind; you must have a lot on your hands, this time of year.’

‘You, too.’

He agrees. ‘We do have a bit of a rush on, around Easter.’

I only realize we’ve giggled when Richard gives us an irritated flick of a glance. I indicate for Mark to sit.

He says, ‘This is the warmest place I know. Chapel’s freezing, and we were in there for hours.’

It is cold outside, and we’ve candles lit. His hair is catching the shine of them; he’s brightening the room. ‘It went well, though?’ I wish I knew how to talk about his work.

‘Could be better.’ Cheerful, though. ‘Will be better.’

We smile at each other. ‘Good,’ I say. ‘Good.’

He says, ‘It’s just that it’s so comforting, in here. The royal apartments haven’t been a comfortable place to be, lately.’

He could mean physically, because of all the building-works, but his demeanour suggests otherwise: he’s tense, tentative. I recall what Richard said: Le Corbeau isn’t best pleased about it, to put it very, very mildly. It’s true, then? I don’t look at Richard; resolutely, I don’t. Not that he’s looking at me: what I can feel is him listening. Perhaps this is how he does it: not jubilant, ribald exchanges of gossip, but stealth. Taking what he can, when he can. And now here’s me doing the same.

Mark almost whispers, ‘It’s a gift, isn’t it, to be so full of life. To be so sure. So sure of yourself.’

Ah, yes, but that’s the life of a king, isn’t it.

‘She’s—’ he frowns, thinking, ‘true to herself.’

She? ‘Who?’

‘The queen. True to herself. In this place, where everyone’s saying one thing and thinking another. Where everyone’s saying something to one person, and something else to the next. Which means, though, that she’s very alone.’

Alone? Anne Boleyn? Whenever I’ve seen her, she’s been the centre of attention: the king’s attention, indulgent and lavish; the Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, playing up to her. Her family: that brother, father, uncle. It’s Queen Catherine who’s alone. Banished to some old castle. Forbidden, even, to see her own daughter. And she’s never had family, here: shipped, at sixteen, a thousand miles from her happy childhood home. Imagine: to be told, over the years, of the deaths; her mother, first, then father, big sister, little brother. Friends, though, she does have; and has always had. Proper friends. There was no playing up to Queen Catherine; no need for it. By all accounts, she made friends and kept them: a few came with her on that galleon and are locked away with her now in that castle.

Mark sighs. ‘I can’t understand why he’s doing it.’

The king, he means. The mistress. Well, yes: that, we can agree on.

‘He married for love,’ he says. ‘Married a fascinating woman: a clever and stunning woman. Had—has—a child by her.’

‘Beautiful kid,’ it has to be said.

‘So, why should he need to do this? If I were him, I’d never look at another woman.’

He is so serious that, oddly, I can’t help but smile. He’s looking tired, too, though. ‘Listen, Mark, I’m going to mix you a tonic.’ Perhaps even risk passing him a manus christi, one of the amber roses I was making when I first saw him, one of the few to which I added rosewater and later gilded. Let’s see if sugar, rosewater and gold can’t work their powers to wash away that lavender tint around his eyes.

His gloom vanishes. ‘Really? A potion? Later, though. I have to go.’

‘Go? Already?’

‘I shouldn’t be here. Things to do. I only dropped by. Just wanted to—’ He shrugs. ‘Lucy, you’re so…’

I’m so…?

‘…sane.’

Sane?

‘I’ll be back,’ he promises.

And he’s gone. I’d sort of forgotten about Richard; that he’s here. But here he is; as he has been, all along. The only sound, his blade scratching at a chunk of sugarloaf. Between us, nothing; silence. It’ll be me who breaks it. ‘Poor Mark.’ Something which means nothing at all; which simply means, Mark was here.

‘Oh, he’s always like that.’ This comes back very quickly.

And it surprises me in all kinds of ways. Not least, ‘Like what?’ And, anyway, how does he know?

‘That’s what Silvester says: Smeaton’s always like that. All chivalrous.’ Said as if it’s a dirty word. Which is a new one on me.

‘And since when has there been anything wrong with chivalry?’

He still doesn’t look up. ‘Oh, come on, Lucy,’ he murmurs, low-key, casual. ‘He’s like some fifteenth-century knight. Love and devotion. He’s kidding himself. This is the real world.’

Is it?

‘Of course, he’d like to be a knight; but he’s the son of a seamstress, you know, and a Dutch father who’s dead. You won’t know, of course, because he doesn’t like it known.’

Scrape, scrape, scrape.

He could at least look at me. If he’s going to be that rude about a friend of mine, he could at least look at me when he does it. ‘So? At least he knows who he’s the son of.’

Richard’s expression as he does look up isn’t the one I’m already cringing from. It’s one of surprise. ‘Oh, Lucy.’ And disappointment has softened his voice. ‘That was a bit close to the bone.’

But he deserved it; he deserved it, didn’t he? ‘Well, don’t be so quick to judge people!’

How on earth did I bring him up to be so shallow? Why have I always let him get away with it?

He makes a small show of giving in gracefully. Resumes his work. Says nothing.

Me, likewise.

So, we’re not speaking. Which has never happened before.

Anne Boleyn (#ulink_3e2007a5-e1a7-5c53-8225-7bc90b8083da)

We moved into 1527 and it seemed that the rain that’d started a year earlier still didn’t let up. Spring was slow off the ground. Our rooms were choked with woodsmoke, our clothes bitter-smelling with it. I remember my brother’s wife at a window, wondering, ‘When will this weather break?’ I remember the longing in her voice. The weather didn’t bother me greatly; I was happy and had so much to look forward to. Henry would be divorced, that year, and he’d marry me. I’d be queen, we’d have a baby prince, and there would be a long-overdue new beginning: a young, strong monarchy, busy and respected in Europe. There’d be reform, if I had my way, and of course I would have my way. I wasn’t interested in looking out of windows at monotonous, drenching rain.

Mid-May, when summer should have been peeking from the trees but was in fact still slithering in the mud, Henry asked for an ecclesiastical court to meet in secret to rule his marriage invalid. Wolsey, Warham—the old archbishop—and the other bishops, and a lot of church lawyers, they were all there: the great and the good, in most people’s view, although I can think of other ways to describe them. They informed Henry that he’d be called to give evidence. He did his homework. He was nervous, and asked me to listen to him rehearsing his case. As far as I could see, there was no case to answer; it was open and shut: she was no wife to him. And anyway, why answer to them? ‘Who’s king?’ I’d complain. It infuriated me that he had to go scraping and bowing to those old men in their dingy robes.