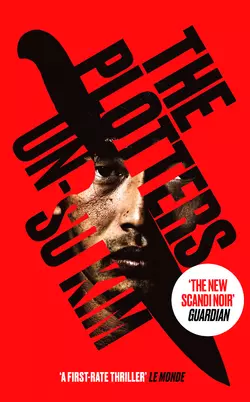

The Plotters

Un-su Kim

A thriller like you’ve never read one before, from the hottest new voice in Korean fiction‘A work of literary genius’ Karen Dionne, internationally bestselling author of Home‘I loved it!’ M. W. Craven, author of The Puppet Show‘You’ll be laughing out loud every five minutes’ You-jeong Jeong, author of The Good Son‘A mash-up of Tarantino and Camus set in contemporary Seoul’ Louisa Luna, author of Two Girls Down‘An incredible cast of characters’ Le monde‘Smart but lightning fast’ Brian Evenson, author of Last DaysPlotters are just pawns like us. A request comes in and they draw up the plans. There’s someone above them who tells them what to do. And above that person is another plotter telling them what to do. You think that if you go up there with a knife and stab the person at the very top, that’ll fix everything. But no-one’s there. It’s just an empty chair.Reseng was raised by cantankerous Old Raccoon in the Library of Dogs. To anyone asking, it’s just an ordinary library. To anyone in the know, it’s a hub for Seoul’s organised crime, and a place where contract killings are plotted and planned. So it’s no surprise that Reseng has grown up to become one of the best hitmen in Seoul. He takes orders from the plotters, carries out his grim duties, and comforts himself afterwards with copious quantities of beer and his two cats, Desk and Lampshade.But after he takes pity on a target and lets her die how she chooses, he finds his every move is being watched. Is he finally about to fall victim to his own game? And why does that new female librarian at the library act so strangely? Is he looking for his enemies in all the wrong places? Could he be at the centre of a plot bigger than anything he’s ever known?

Copyright (#uc0517b04-3f0a-5260-9af5-51ca19463d72)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Un-Su Kim 2010

English translation copyright © Sora Kim-Russell 2018, 2019

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Cover photograph © Plainpicture / Phillippe Lesprit

Un-Su Kim asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work; Sora Kim-Russell asserts the moral right to be identified as the translator of this work

This book is published with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea)

This translation originally published in Australia, in slightly different form, by The Text Publishing Company

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008315771

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008315795

Version: 2018-12-12

Contents

Cover (#u2c6218b7-7cae-5fff-9101-7ebd7853358d)

Title Page (#uc7d0ed7d-4020-5d6f-a6a5-1ddbd4b16e9b)

Copyright

On Hospitality (#ud6aa2252-e4fa-54f9-bc49-82a00cd8f228)

Achilles’ Heel (#uf47d864a-e506-5a8c-baf4-d769cca2c3ab)

Bear’s Pet Crematorium (#u63c80a39-8143-58aa-9340-66422ca6f38f)

The Doghouse Library (#litres_trial_promo)

Beer Week (#litres_trial_promo)

The Meat Market (#litres_trial_promo)

Mito (#litres_trial_promo)

Knitting (#litres_trial_promo)

Frog Eat Frog (#litres_trial_promo)

The Barber and His Wife (#litres_trial_promo)

The Door to the Left (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ON HOSPITALITY (#ulink_cafcbab5-b419-513f-8eb5-ad0c061ab508)

The old man came out to the garden.

Reseng tightened the focus on the telescopic sight and pulled back the charging handle. The bullet clicked loudly into the chamber. He glanced around. Other than the tall fir trees reaching for the sky, nothing moved. The forest was silent. No birds took flight, no bugs chirred. Given how still it was out here, the noise of a gunshot would travel a long way. And if people heard it and rushed over? He brushed aside the thought. No point in worrying about that. Gunshots were common out here. They would assume it was poachers hunting wild boar. Who would waste their time hiking this deep into the forest just to investigate a single gunshot? Reseng studied the mountain to the west. The sun was one hand above the ridgeline. He still had time.

The old man started watering the flowers. Some received a gulp, some just a sip. He tipped the watering can with great ceremony, as if he were serving them tea. Now and then he did a little shoulder shimmy, as if dancing, and gave a petal a brief caress. He gestured at one of the flowers and chuckled. It looked like they were having a conversation. Reseng adjusted the focus again and studied the flower the old man was talking to. It looked familiar. He must have seen it before, but he couldn’t remember what it was called. He tried to recall which flower bloomed in October—cosmos? zinnia? chrysanthemum?—but none of the names matched the one he was looking at. Why couldn’t he remember? He furrowed his brow and struggled to come up with the name but soon brushed aside that thought, too. It was just a flower—what did it matter?

A huge black dog strolled over from the other end of the garden and rubbed its head against the old man’s thigh. A mastiff, purebred. The same beast Julius Caesar had brought back from his conquest of Britain. The dog the ancient Romans had used to hunt lions and round up wild horses. As the old man gave the dog a pat, it wagged its tail and wound around his legs, getting in his way as he tried to continue his watering. He threw a deflated soccer ball across the garden, and the dog raced after it, tail wagging, while the old man returned to his flowers. Just as before, he gestured at them, greeted them, talked to them. The dog came back immediately, the flattened soccer ball between its teeth. The old man threw the ball farther this time, and the dog raced after it again. The ferocious mastiff that had once hunted lions had been reduced to a clown. And yet the old man and the dog seemed well suited to each other. They repeated the game over and over. Far from getting bored, they looked like they were enjoying it.

The old man finished his watering and stood up straight, stretching and smiling with satisfaction. Then he turned and looked halfway up the mountain, as if he knew Reseng was there. The old man’s smiling face entered Reseng’s crosshairs. Did he know the sun was less than a hand above the horizon now? Did he know he would be dead before it dipped below the mountain? Was that why he was smiling? Or maybe he wasn’t actually smiling. The old man’s face seemed fixed in a permanent grin, like a carved wooden Hahoe mask. Some people just had faces like that—people whose inner feelings you could never guess at, who smiled constantly, even when they were sad or angry.

Should he pull the trigger now? If he pulled it, he could be back in the city before midnight. He’d take a hot bath, down a few beers until he was good and drunk, or put an old Beatles record on the turntable and think about the fun he’d soon have with the money on its way into his bank account. Maybe, after this final job, he could change his life. He could open a pizza shop across from a high school, or sell cotton candy in the park. Reseng pictured himself handing armfuls of balloons and cotton candy to children and dozing off under the sun. He really could live that life, couldn’t he? The idea of it suddenly seemed so wonderful. But he had to save that thought for after he pulled the trigger. The old man was still alive, and the money was not yet in his account.

The mountain was swiftly casting its shadow over the old man and his cabin. If Reseng was going to pull the trigger, he had to do it now. The old man had finished watering and would be going back inside any second. The job would get much harder then. Why complicate it? Pull the trigger. Pull it now and get out of here.

The old man was smiling, and the black dog was running with the soccer ball in its mouth. The old man’s face was crystal clear in the crosshairs. He had three deep wrinkles across his forehead, a wart above his right eyebrow, and liver spots on his left cheek. Reseng gazed at where his heart would soon be pierced by a bullet. The old man’s sweater looked hand-knit, not factory-made, and was about to be drenched in blood. All he had to do was squeeze the trigger just the tiniest bit, and the firing pin would strike the primer on the 7.62 mm cartridge, igniting the gunpowder inside the brass casing. The explosion would propel the bullet forward along the grooves inside the bore and send it spinning through the air, straight toward the old man’s heart. With the high speed and destructive force of the bullet, the old man’s mangled organs would explode out the exit wound in his lower back. Just the thought of it made the fine hairs all over Reseng’s body stand on end. Holding the life of another human being in the palm of his hand always left him with a funny feeling.

Pull it.

Pull it now.

And yet for some reason, Reseng did not pull the trigger and instead set the rifle down on the ground.

“Now’s not the right time,” he muttered.

He wasn’t sure why it wasn’t the right time. Only that there was a right time for everything. A right time for eating ice cream. A right time for going in for a kiss. And maybe it sounded stupid, but there was also a right time for pulling a trigger and a right time for a bullet to the heart. Why wouldn’t there be? And if Reseng’s bullet happened to be sailing straight through the air toward the old man’s heart just as the right moment fortuitously presented itself to him? That would be magnificent. Not that he was waiting for the best possible moment, of course. That auspicious moment might never come. Or it could pass by right under his nose. It occurred to him that he simply didn’t want to pull the trigger yet. He didn’t know why, but he just didn’t. He lit a cigarette. The shadow of the mountain was creeping past the old man’s cottage.

When it turned dark, the old man took the dog inside. The cottage must not have had electricity, because it looked even darker in there. A single candle glowed in the living room, but Reseng couldn’t make out the interior well enough through the scope. The shadows of the man and his dog loomed large against a brick wall and disappeared. Now the only way Reseng could kill him from his current position would be if the old man happened to stand directly in the window with the candle in his hand.

As the sun sank below the ridge, darkness descended on the forest. There was no moon; even objects close at hand were hard to make out. There was only the glimmer of candlelight from the old man’s cottage. The darkness was so dense that it made the air seem damp and heavy. Why didn’t Reseng just leave? Why linger there in the dark? He wasn’t sure. Wait for daybreak, he decided. Once the sun came up, he’d fire off a single round—no different from firing at the wooden target he’d practiced with for years—and then go home. He put his cigarette butt in his pocket and crawled into the tent. Since there was nothing else to do to pass the time, he ate a packet of army crackers and fell asleep wrapped up in his sleeping bag.

Reseng was awakened abruptly about two hours later by heavy footsteps in the grass. They were coming straight toward his tent. Three or four irregular thuds. A torso sweeping through tall grass. He couldn’t decipher what was coming his way. Could be a wild boar. Or a wildcat. Reseng disengaged the safety and pointed his rifle at the darkness, toward the approaching sound. He couldn’t pull the trigger yet. Mercenaries lying in wait had been known to fire into the dark out of fear, without checking their targets, only to discover that they’d hit a deer or a police dog or, worse, one of their fellow soldiers lost in the forest while out scouting. They would sob next to the corpse of a brother in arms felled by friendly fire, their beefy, tattooed bodies shaking like a little girl’s as they told their commanding officers, “I didn’t mean to kill him, I swear.” And maybe they really hadn’t meant to. Since they’d never before had to face their fear of things going bump in the night, the only thing someone with muscles for brains knew how to do was point and shoot into the dark. Reseng waited calmly for whatever was out there to reveal itself. To his surprise, what emerged was the old man and his dog.

“What are you doing out here?” the old man asked.

Now, this was funny. As funny as if the bull’s-eye at the firing range had walked right up to him and said, Why haven’t you shot me yet?

“What’re you doing out here? I could’ve shot you,” Reseng said, his voice trembling.

“Shot me? How’s that for turning the tables?” the old man said with a smile. “This is my land. You’re the one who doesn’t belong, crashing on someone else’s property.” He looked relaxed. The situation was unusual, to say the least, and yet he didn’t seem at all taken aback. Instead, the one taken aback was Reseng.

“You startled me. I thought you were a wild animal.”

“You’re a hunter?” the old man asked, looking pointedly at Reseng’s rifle.

“Yes.”

“That’s a Dragunov. You only see those in museums. So poachers these days hunt with Vietnam War rifles?”

“I don’t care how old the gun is as long as it can take down a boar.” Reseng tried to sound nonchalant.

“True. If it stops a boar, then it doesn’t matter what gun you use. Hell, if you can stop a boar with chopsticks—or a toothpick, for that matter—you can skip the gun altogether.”

The old man laughed. The dog waited patiently at his side. It was much bigger than it had looked through the scope. And much more intimidating than when it was chasing after a deflated soccer ball.

“That’s a nice dog,” Reseng said. The old man looked down at the dog and stroked its head.

“He is a nice dog. He’s the one who sniffed you out. But he’s old now.”

The dog never took its eyes off of Reseng. It didn’t growl or bare its teeth, but it wasn’t exactly friendly, either. The old man gave the dog’s head another pat.

“Since you insist on staying the night, don’t catch cold out here. Come to the house.”

“Thank you for the offer, but I wouldn’t want to trouble you.”

“It’s no trouble.”

The old man turned and strode back down the slope, the dog at his heels. He didn’t have a flashlight, but he seemed to have no trouble finding his way through the dark. Reseng’s mind was in a whirl. His rifle was charged and ready, and his target was only five meters away. He watched the old man disappear into the darkness. A second later, he shouldered the rifle and headed down after him.

The cottage was warm. A fire blazed in the redbrick fireplace. There were no furnishings or decorations, save for a threadbare rug and small table in front of the fire and a few photos on the mantelpiece. The photos were all of the old man, sitting or standing with others, always at the center of the group, the people at his sides smiling stiffly, as if honored to be photographed with him. None of the photos seemed to be of family.

“Kind of early in the year for a fire,” Reseng said.

“The older you get, the more you feel the cold. And I’m feeling it more than ever this year.”

The old man stuffed a few pieces of dry wood into the fire, the flames balking briefly at the new addition. Reseng unslung his rifle from his shoulder and leaned it against the doorjamb. The old man stole a glance at the gun.

“Isn’t October closed season for hunting?”

There was a twinkle in his eye. He’d been using banmal, the familiar form of speech, as if he and Reseng were old friends, but it didn’t bother Reseng.

“A man could starve to death trying to follow every law.”

“True, not all laws need to be followed,” the old man murmured. “You’d be stupid to try.”

As he stirred the logs with a metal poker, the flames rose and licked at a piece of wood that had not yet caught fire.

“Well, I’ve got booze and I’ve got tea, so pick your poison.”

“Tea sounds good.”

“You don’t want something stronger? You must’ve been freezing.”

“I don’t usually drink when I’m hunting. Besides, it’s dangerous to drink if you’re going to sleep outdoors.”

“Then indulge tonight,” the old man said with a smile. “Not much chance of freezing to death in here.”

He went to the kitchen and returned with two tin cups and a bottle of whiskey, then used a pair of tongs to carefully retrieve a kettle of black tea from inside the fireplace. He poured tea into one of the cups. His movements were smooth and measured. He handed the cup to Reseng and filled his own, then surprised Reseng by topping it off with whiskey.

“If you’re not warmed up yet, a touch of whiskey’ll get you the rest of the way. You can’t go hunting until daybreak anyway.”

“Does tea go with whiskey?” Reseng asked.

“Why not? It’s all the same going down.”

The old man wrinkled his eyes at him. He had a handsome face. He looked like he would have received a lot of compliments in his younger days. His chiseled features made him seem somehow tough and warm at the same time. As if the years had gently filed down his rough edges and softened him. Reseng held out his cup as the old man tipped a little whiskey into it. The scent of alcohol wafted up from the warm tea. It smelled good. The dog sauntered over from the other end of the living room and lay down next to Reseng.

“You’re a good person.”

“Pardon?”

“Santa likes you,” the old man said, gesturing at the dog. “Dogs know good people from bad right away.”

Up close, the dog’s eyes were surprisingly gentle.

“Maybe it’s just stupid,” Reseng said.

“Drink your tea.”

The old man smiled. He took a sip of his spiked tea, and Reseng followed suit.

“Not bad,” Reseng said.

“Surprising, huh? Tastes good in coffee, too, but black tea is better. Warms your stomach and your heart. Like wrapping your arms around a good woman,” he added with a childish giggle.

“If you’ve got a good woman, why stop at hugging?” Reseng scoffed. “A good woman is always better than some boozy tea.”

The old man nodded. “I suppose you’re right. No tea compares to a good woman.”

“But the taste is memorable, I’ll give you that.”

“Black tea is steeped in imperialism. That’s what gives it its flavor. Anything this flavorful has to be hiding an incredible amount of carnage.”

“Interesting theory.”

“I’ve got some pork and potatoes. Care for some?”

“Sure.”

The old man went outside and came back with a blackened lump of meat and a handful of potatoes. The meat looked awful. It was covered in dirt and dust and still had patches of hair, but even worse was the rancid smell. He shoved the pork into the hot ash at the bottom of the fireplace until it was completely coated, then skewered it on an iron spit and propped it over the fire. He stirred the flames with the poker and tucked the potatoes into the ash.

“I can’t say that looks all that appetizing,” Reseng said.

“I lived in Peru for a while. Learned this method from the Indians. Doesn’t look clean but tastes great.”

“Frankly, it looks pretty terrible, but if it’s a secret native recipe, then I guess there must be something to it.”

The old man grinned at Reseng.

“Just a few days ago, I discovered something else I have in common with the native Peruvians.”

“What’s that?”

“No refrigerator.”

The old man turned the meat. His face looked earnest in the glow of the fire. As he pricked the potatoes with a skewer, he murmured at them, “You’d better make yourselves delicious for our important guest.” While the meat cooked, the old man finished off his spiked tea and refilled his cup with just whiskey, then offered more to Reseng.

Reseng held out his cup. He liked how the whiskey burned on its way down his throat and radiated smoothly up from his empty stomach. The alcohol spread pleasantly through his body. For a moment, everything felt unreal. He would never have imagined it: a sniper and his target sitting in front of a roaring fire, pretending to be best friends … Each time the old man turned the meat, a delicious aroma wafted toward him. The dog moved closer to the fireplace to sniff at the meat, but he hung back at the last moment and grumbled instead, as if afraid of the fire.

“There, there, Santa. Don’t worry,” the old man said, patting the dog. “You’ll get your share.”

“The dog’s name is Santa?”

“I met this fellow on Christmas Day. That day, he lost his owner and I lost my leg.”

The old man lifted the hem of his left pant leg to reveal a prosthesis.

“He saved me. Dragged me over nearly five kilometers of snow-covered road.”

“That’s a hell of a way to meet.”

“Best Christmas gift I ever got.”

The old man continued to stroke the dog’s head.

“He’s very gentle for his size.”

“Not exactly. I used to have to keep him leashed all the time. One glimpse of a stranger and he’d attack. But now that he’s old, he’s gone soft. It’s odd. I can’t get used to the idea of an animal being this friendly with people.”

The meat smelled cooked. The old man poked at it with the skewer and took it off the fire. Using a serrated knife, he carved the meat into thick slices. He gave a piece to Reseng, a piece to himself, and a piece to Santa. Reseng brushed off the ash and took a bite.

“What an unusual flavor. Doesn’t really taste like pork.”

“Good, yeah?”

“It is. But do you have any salt?”

“Nope.”

“No fridge, no salt—that’s quite a way to live. Do the native Peruvians also live without salt?”

“No, no,” the old man said sheepishly. “I ran out a few days ago.”

“Do you hunt?”

“Not anymore. About a month ago, I found a wild boar stuck in a poacher’s trap. Still alive. I watched it gasp for breath and thought to myself, Do I kill it now or wait for it to die? If I waited for it to die, then I could blame its death on the poacher who left that trap out, but if I killed it, then I’d be responsible for its death. What would you have done?”

The old man’s smile was inscrutable. Reseng gave the tin cup a swirl before polishing off the alcohol.

“Hard to say. I don’t think it really matters who killed the boar.”

The old man seemed to ponder this for a moment before responding.

“I guess you’re right. When you really think about it, it doesn’t matter who killed it. Either way, here we are enjoying some Peruvian-style roasted boar.”

The old man laughed loudly. Reseng laughed, too. It wasn’t much of a joke, but the old man kept laughing, and Reseng followed suit with a loud laugh of his own.

The old man was in high spirits. He filled Reseng’s cup with whiskey until it was nearly overflowing, then filled his own and raised it in a toast. They downed their drinks in one gulp. The old man picked up the skewer and fished a couple of potatoes from the hot ashes. After taking a bite of one, he pronounced it delicious and gave the other to Reseng. Reseng brushed off the ashes and took a bite. “That is delicious,” he said.

“There’s nothing better than a roasted potato on a cold winter’s day,” the old man said.

“Potatoes always remind me of someone …” Reseng started to babble. His face was red from the alcohol and the glow of the fire.

“I’m guessing this story doesn’t have a happy ending,” the old man said.

“It doesn’t.”

“Is that someone alive or dead?”

“Long dead. I was in Africa at the time, and we got an emergency call in the middle of the night. We jumped in a truck and headed off. It turned out that a rebel soldier who’d escaped camp had taken an old woman hostage. He was just a kid—still had his baby fat. Must’ve been fifteen, maybe even fourteen? From what I saw, he was worked up and scared out of his wits, but not an actual threat. The old woman kept saying something to him. Meanwhile, he was pointing an AK-47 at her head with one hand and cramming a potato into his mouth with the other. We all knew he wasn’t going to do anything, but then the order came over the walkie-talkie to take him out. Someone pulled the trigger. We ran over to take a closer look. Half of the kid’s head was blown away, and in his mouth was the mashed-up potato that he never got the chance to swallow.”

“The poor thing. He must’ve been starving.”

“It felt so strange to look into the mouth of a boy with half his head missing. What would’ve happened if we’d waited just ten more seconds? All I could think was, If we had waited, he would’ve been able to swallow the potato before he died.”

“Not like anything would’ve changed for that poor boy if he had swallowed it.”

“No, of course not.” Reseng’s voice wavered. “But it still felt weird to think about that chewed-up potato in his mouth.”

The old man finished the rest of his whiskey and poked around in the ashes with the skewer to see if there were any more potatoes. He found one in the corner and offered it to Reseng, who gazed blankly at it and politely declined. The old man looked at the potato; his face darkened and he tossed it back into the ashes.

“I’ve got another bottle of whiskey. What do you say?” the old man asked.

Reseng thought about it for a moment. “Your call,” he said.

The old man brought another bottle from the kitchen and poured some for him. They sipped in silence as they watched the flames dance in the fireplace. As Reseng grew tipsy, a feeling of profound unreality washed over him. The old man’s eyes never left the fire.

“Fire is so beautiful,” Reseng said.

“Ash is more beautiful once you get to know it.”

The old man slowly swirled his cup as he gazed into the flames. He smiled then, as if recalling something funny.

“My grandfather was a whaler. This was back before they outlawed whaling. He didn’t grow up anywhere near the ocean—he was actually from inland Hamgyong Province, but he went down south to Jangsaengpo harbor for work and ended up becoming the best harpooner in the country. During one of the whaling trips, he got dragged under by a sperm whale. Really deep under. What happened was, he threw the harpoon into the whale’s back, but the rope tangled around his foot and pulled him overboard. Those flimsy colonial-era whaling boats and shoddy harpoons were no match for an animal that big. A male sperm whale can grow up to eighteen meters long and weigh up to sixty tons. Think about it. That’s like fifteen adult African elephants. I don’t care if it were just a balloon animal—I would never want to mess with anything that big. No way, no how. But not my grandfather. He stuck his harpoon right in that giant whale.”

“What happened next?” Reseng asked.

“Utter havoc, of course. He said the shock of falling off the bow made him woozy, and he couldn’t tell if he was dreaming or hallucinating. Meanwhile, he was being dragged helplessly into the dark depths of the ocean by a very angry whale. He said the first thing he saw when he finally snapped out of his daze was a blue light coming off the sperm whale’s fins. As he stared at the light, he forgot all about the danger he was in. When he told me the story, he kept going on about how mysterious and tranquil and beautiful it was. An eighteen-meter-long behemoth coursing through the pitch-black ocean with glowing blue fins. I tried to break it to him gently—he was practically in tears just recalling it—that since whales are not bioluminescent, there was no way its fins could have glowed like that. He threw his chamber pot at my head. Ha! What a hothead! He told the story to everyone he met. I told him everyone thought he was lying because of the part about the fins. But all he said to that was, ‘Everything people say about whales is a lie. Because everything they say comes from a book. But whales don’t live in books, they live in the ocean.’ Anyway, after the whale dragged him under, he passed out.”

The old man refilled his cup halfway and took a sip.

“He said that when he came to, there was a big full moon hanging in the night sky, and waves were lapping at his ear. He thought luck was on his side and the waves had pushed him onto a reef. But it turned out he was on top of the whale’s head. Incredible, wouldn’t you say? There he was, lying across a whale, staring at a buoy, a growing pool of the whale’s slick red blood all around him, and the whale itself, propping him up out of the water with its head, that harpoon still sticking out of its back. Can you imagine anything stranger or more incomprehensible? I’ve heard of whales lifting an injured companion or a newborn calf out of the water so they can breathe. But this wasn’t a companion or a baby whale, or even a seal or a penguin. It was my grandfather, a human being, and the same person who’d shoved a harpoon in its back! I honestly don’t understand why the whale saved him.”

“No, it doesn’t make any sense,” Reseng said, taking a sip of whiskey. “You’d think that whale would have torn him apart.”

“He just lay there on the whale’s head for a long time, even after he’d regained consciousness. It was awkward, to say the least. What can you do when you’re stuck on top of a whale? There was nothing out there but the silvery moon, the dark waves, a sperm whale spilling buckets of blood, and him—well and truly up shit creek. My grandfather said the sight of all that blood in the moonlight made him apologize to the whale. It was the least he could do, you know? He wanted to pull out the harpoon, too, but easier said than done. Throwing a harpoon is like making a bad life decision: so easy to do, but so impossible to take back once the damage is done. Instead, he cut the line with the knife he kept on his belt. The moment he cut it, the whale dove and resurfaced some distance away, then headed straight back to where my grandfather was clinging to the buoy, struggling to stay afloat. He said it watched as he flailed pathetically, filled with shame, all tangled up in the line from the harpoon he himself had thrown. According to my grandfather, the beast came right up and gazed at him with one enormous dark eye, a look of innocent curiosity that seemed to say, How did such a little scaredy-cat like you manage to stick a harpoon in the likes of me? You’re braver than you look! Then, he said, it gave him a playful shove, as if to say, Hey, kid, that was pretty naughty. Better not pull another dangerous stunt like that! All the blood it had lost was turning the water murky, and yet it seemed to brush off the whole matter of my grandfather stabbing it in the back. Each time my grandfather got to this part of the story, he used to slap his knee and shout, ‘That monster’s heart was as big as its body! Completely different from us small-minded humans.’ He said the whale stayed by his side all night, until the whaleboat caught up to them. The other whalers had been tracking the buoys in search of my grandfather. As soon as the ship appeared in the distance, the whale swam in a circle around him, as if it were saying good-bye, and then dove again, even deeper than before, the harpoon with my grandfather’s name carved into it still quivering in its back. Incredible, huh?”

“Yeah, that’s quite a story,” Reseng said.

“I guess that after that narrow escape from a watery death, my grandfather had some serious second thoughts about whaling. He told my grandmother he didn’t want to go back. My grandmother was a very kind and patient woman. She hugged him and said if he hated catching whales that much, then he should stop. He said he sobbed like a baby in her arms and told her, ‘I felt so scared, so terribly scared!’ And then he really did keep his distance from whaling for a while. But those crybaby days of his didn’t last long. They were poor, there were too many mouths to feed, and whaling was the only trade he’d ever learned. He didn’t know how else to provide for all those hungry children squawking at him like baby sparrows. So he went back to work and launched his harpoon at every whale he saw in the East Sea until he retired at the age of seventy. But there was one more funny thing that happened: In 1959, he ran into the same sperm whale again. Exactly thirty years after his miraculous survival. His rusted old harpoon was still stuck in its back, but the whale was just swimming along, all gallant and free, as if that harpoon had always been there and were simply a part of its body. Actually, it’s not uncommon to hear about whales surviving long after a harpoon attack. They even say that once, in the nineteenth century, a whale was caught with an eighteenth-century harpoon still stuck in it. Anyway, the whale didn’t swim off when it saw the whaling ship; in fact, it cruised right up to my grandfather’s boat, the harpoon sticking straight up like a periscope, and slowly circled it. As if it were saying, Hey! Long time no see, old friend! But what’s this? Still hunting whales? You really don’t know when to quit, do you?” The old man laughed.

“Your grandfather must have felt pretty embarrassed,” Reseng said.

“You bet he did. The sailors said my grandfather took one look at that sperm whale and dropped to his knees. He threw himself on the deck and let out a howl. He wept and called out, “Whale, forgive me! I’m so sorry! How awful for you, swimming all those years with a harpoon stuck in your back! After we said good-bye, I wanted to stop, I swear. You probably don’t know this, since you live in the sea, but things have been really tough up on land. I’m still living in a rental, and my brats eat so much, you’d be shocked at what it costs to feed them. I had to come back because I could barely make ends meet. Forgive me! Let’s meet again and have a drink together. I’ll bring the booze if you catch us a giant squid to snack on. Ten crates of soju and one grilled giant squid should do it. I’m so sorry, Whale. I’m sorry I stabbed you in the back with a harpoon. I’m sorry I’m such a fool. Boo-hoo-hoo!’”

“Did he really yell all of that at the whale?” Reseng asked.

“They say he really did.”

“He was a funny guy, your grandfather.”

“He was indeed. Anyway, after that, he gave up whaling and left Jangsaengpo harbor for good. He came up to Seoul and spent all his time drinking. I imagine he felt pretty trapped, given that he couldn’t go out to sea anymore, and with barbed wire strung all across the thirty-eighth parallel, he couldn’t go back north to his hometown, either. So whenever he got drunk, he latched on to people and started up with that same boring old whale tale. He told it over and over, even though everyone had already heard it hundreds of times and no one wanted to hear it again. But he wasn’t doing it to brag about his adventures on the high seas. He believed that people should emulate whales. He said that people had grown as small and crafty as rats, and that the days of taking slow, huge, beautiful strides had vanished. The age of giants was over.”

The old man swigged his whiskey. Reseng refilled his cup and took a sip.

“Toward the end, he found out he was in the final stages of liver cancer. It wasn’t exactly a surprise. As a sailor, he’d been guzzling booze from the age of sixteen to the age of eighty-two. But I guess the news meant nothing at all to him, because no sooner did he return from seeing the doctor than he hit the bottle again. He gathered his kids together and told them, ‘I’m not going to any hospital. Whales accept it when their time comes.’ And he never did go back to the doctor. After about a month, my grandfather put on his best clothes and returned to Jangsaengpo harbor. According to the sailors there, he loaded a small boat up with ten crates of soju, just like he’d said he would, and rowed until he disappeared over the horizon. And he never came back. His body was never found. Maybe he really did row until he caught the scent of ambergris and tracked down his whale. If he did, then I’m sure he broke open all ten crates of soju that night as they caught up on the years they’d missed, and if he didn’t, then he probably drifted around the ocean, drinking alone, until he died. Or maybe he’s still out there somewhere.”

“That’s quite an ending.”

“It’s a dignified way to go. In my opinion, a man ought to be able to choose a death that gives his life a dignified ending. Only those who truly walk their own path can choose their own death. But not me. I’ve been a slug my whole life, so I don’t deserve a dignified death.”

The old man smiled bitterly. Reseng was at a loss for a response. The look on the old man’s face was so dark that Reseng felt compelled to say something comforting, but he really couldn’t think of what to say. The old man refilled his cup with whiskey and polished it off again. They sat there for a long time. Each time the flames died down, Reseng added more wood to the fire. While Reseng and the old man sipped whiskey in comfortable silence, each new piece caught fire, crackled and flared up hot and ferocious, then slowly burned down to glowing charcoal, and then to white ash.

“I really talked your ear off tonight. They say the older you get, the more you’re supposed to keep your purse strings open and your mouth shut.”

“Oh, no, I enjoyed it.”

The old man shook the whiskey bottle and eyed the bottom. There was only about a cup left.

“Mind if I finish this off?”

“Go right ahead,” Reseng said.

The old man poured the rest of the whiskey into his cup and downed it.

“We’d better call it a night. You must be exhausted. I should’ve let you sleep, but instead I kept talking.”

“No, it was a nice evening, thanks to you.”

The old man curled up on the floor to the right of the fireplace. Santa sauntered over and lay down next to him. Reseng lay down to the left of the fireplace. The shadows of the two men and the dog danced on the brick wall opposite them. Reseng looked at his rifle propped against the door.

“Have some breakfast before you leave tomorrow,” the old man said, rolling onto his side. “You don’t want to hunt on an empty stomach.”

Reseng hesitated before saying, “Of course, I’ll do that.”

The crackling fire and the dog’s steady breaths sounded unusually loud. The old man didn’t say another word. Reseng listened for a long time to the old man and the dog breathing in their sleep before he finally joined them. It was a peaceful sleep.

When he awoke, the old man was preparing breakfast. A simple meal of white rice, radish kimchi, and doenjang soup made with sliced potatoes. The old man didn’t say much. They ate in silence. After breakfast, Reseng hurried to leave. As he stepped out the door, the old man handed him six boiled potatoes wrapped in a cloth. Reseng took the bundle and bade him a polite farewell. The potatoes were warm.

By the time Reseng returned to his tent, the old man was watering the flowers again. Just as before, he tipped the watering can with care, as if pouring tea. Then, just as before, he spoke to the flowers and trees and gestured at them. Reseng made a minor adjustment to the scope. The familiar-looking flower grew sharp and distinct in the lens and blurred again. He still could not remember its name. He should have asked the old man.

It was a nice garden. Two persimmon trees stood nonchalantly in the courtyard, while the flowers in the garden beds waited patiently for their season to come. Santa went up to the man and rubbed his head against the man’s thigh. The old man gave the dog a pat. They suited each other. The old man threw the deflated soccer ball across the garden. While Santa ran to fetch it, the old man watered more flowers. What was he saying to them? On closer inspection, he did indeed have a slight limp. If only Reseng had asked him what had happened to his left leg. Not that it makes any difference, he thought. Santa came back with the ball. This time, the old man threw it farther. Santa seemed to be in a good mood, because he ran around in circles before racing off to the end of the garden to fetch the ball. The old man looked like he had finished watering. He put down the watering can and smiled brightly. Was he laughing? Was that carved wooden mask of a face really laughing?

Reseng fixed the crosshairs on the old man’s chest and pulled the trigger.

ACHILLES’ HEEL (#ulink_fedd6e2d-3046-53eb-acab-4981dd0addc7)

Reseng was found in a garbage can. Or, who knows, maybe he was born in that garbage can.

Old Raccoon, who had served as Reseng’s foster father for the last twenty-eight years, liked to tease Reseng about his origins whenever he got to drinking. “You were found in a garbage can in front of a nunnery. Or maybe that garbage can was your mother. Hard to say. Either way, it’s pretty pathetic. But look on the bright side. A garbage can used by nuns is bound to be the cleanest garbage can around.”

Reseng wasn’t bothered by Old Raccoon’s teasing. He decided that being born from a clean garbage can had to be better than being born to the type of parents who’d dump their baby in the garbage.

Reseng lived in the orphanage run by the convent until he was four, after which he was adopted by Old Raccoon and lived in his library. Had Reseng continued to grow up in the orphanage, where divine blessings showered down like spring sunshine and kindly nuns devoted themselves to the careful raising of orphans, his life might have turned out very differently. Instead, he grew up in a library crawling with assassins, hired guns, and bounty hunters. Just as a plant grows wherever it sets down roots, so all your life’s tragedies spring from wherever you first set your feet. And Reseng was far too young to leave the place where he’d set down roots.

The day he turned nine, Reseng was snuggled up in Old Raccoon’s rattan rocking chair, reading The Tales of Homer. Paris, the idiot prince of Troy, was right in the middle of pulling back his bowstring to sink an arrow into the heel of Achilles, the hero whom Reseng had come to love over the course of the book. As everyone knows, this was a very tense moment, and so Reseng was completely unaware that Old Raccoon had been standing behind him for a while, watching him read. Old Raccoon looked angry.

“Who taught you to read?”

Old Raccoon had never sent Reseng to school. Whenever Reseng asked, “How come I don’t go to school like the other kids?” Old Raccoon had retorted, “Because school doesn’t teach you anything about life.” Old Raccoon was right on that point. Reseng never attended school, and yet in all of his thirty-two years, it had not once caused him any problems. Problems? Ha! What kind of problems would he have had anyway? And so Old Raccoon looked gobsmacked to discover Reseng, who hadn’t spent a single day in school, reading a book. Worse, the look on his face said he felt betrayed to learn that Reseng knew how to read.

As Reseng stared up at him without answering, Old Raccoon switched to the low, deep voice he used to intimidate people.

“I said, Who. Taught. You. To. Read?”

His voice was menacing, as if he was going to catch the person who had taught Reseng how to read and do something to them right then and there. In a small, quavering voice, Reseng said that no one had taught him. Old Raccoon still had his scary face on; it was clear he didn’t believe a word of it, and so Reseng explained that he’d taught himself how to read from picture books. Old Raccoon smacked Reseng hard across the face.

As Reseng struggled to stifle his sobs, he swore that he really had learned to read from picture books. It was true. After he’d managed to dig through the 200,000 books crammed on the shelves of Old Raccoon’s gloomy, labyrinthine library to find the few books worth looking at (a comic book adaptation about American slavery, a cheap adult magazine, and a dog-eared picture book filled with giraffes and rhinoceroses), he’d deciphered how the Korean alphabet worked by matching pictures to words. Reseng pointed to his stash of picture books in the corner of the study. Old Raccoon hobbled over on his lame leg and examined each one. He looked dumbfounded; he was clearly wondering how on earth those shoddy books had found their way into his library. Hobbling back, he stared hard at Reseng, his eyes still filled with suspicion, and yanked the hardback copy of The Tales of Homer from his hands. He looked back and forth between the book and Reseng for the longest time.

“Reading books will doom you to a life of fear and shame. So, do you still feel like reading?”

Reseng stared blankly at him—staring blankly was all he could do, as he had no idea what Old Raccoon was talking about. Fear and shame? As if a mere nine-year-old could comprehend such a life! The only life a boy who’d just turned nine could imagine was complaining about a dinner that someone else had prepared. A life in which random events just kept happening to you, as impossible to stop as a piece of onion that keeps slipping out of your sandwich. What Old Raccoon said sounded less like a choice and more like a threat, or a curse being put on him. It was like God saying to Adam and Eve, “If you eat this fruit, you’ll be cast out of Paradise, so do you still want to eat it?” Reseng was afraid. He had no idea what this choice meant. But Old Raccoon was staring him down and waiting for an answer. Would he eat the apple or not?

At last, Reseng stiffly raised his head and composed himself, fists clenched, his face a picture of determination, and said, “I will read. Now, give me back my book.” Old Raccoon gazed down at the boy, who was gritting his teeth, barely containing his tears, and handed back The Tales of Homer.

Reseng’s demand to retrieve his book did not come from an actual desire to read or to defy Old Raccoon. It was because he was clueless about this whole “life of fear and shame” thing.

After Old Raccoon left the room, Reseng wiped away the tears that had only then begun to spill, and curled up into a ball on the rattan rocker. He looked around at Old Raccoon’s dim study, which grew dark early because the windows faced northwest, at the books stacked to the ceiling in some complex and incomprehensible order, at the maze of shelves quietly staked out by dust, and wondered why Old Raccoon was so upset about him reading. Even now, at the age of thirty-two, whenever he pictured Old Raccoon, who had spent most of his life sitting in the corner of the library with a book in his hands, he couldn’t wrap his head around it. For that nine-year-old, the whole incident had felt as awful as if one of his buddies with a pocketful of sweets had stolen Reseng’s single sweet from his mouth.

“Stupid old fart, I hope you get the shits!”

Reseng put his curse on Old Raccoon and wiped the last of his tears with the back of his hand. Then he reopened the book. How could he not? Reading was no longer just some simple way to pass the time. It was now this boy’s Great and Inherent Right, a right won with much difficulty, even if it meant being hit and cursed to live a Life of Fear and Shame. Reseng returned to the scene in The Tales of Homer where the idiot prince of Troy pulls back his bowstring. The scene where the arrow leaves the string and hurtles toward his hero, Achilles. The scene where that cursed arrow pierces Achilles’ heel.

Reseng trembled as Achilles bled to death at the top of Hisarlik Hill. He had been certain his hero would easily pluck that damn arrow from his heel and immediately run his spear through Paris’s heart. But the unthinkable had happened. What had gone wrong? How could the son of a god die? How could a hero with an immortal body, unfellable by any arrow, unpierceable by any spear, be undone by an imbecile like Paris, and, worse, die like an imbecile because he hadn’t protected his one, tiny, no-bigger-than-the-palm-of-his-hand weak spot? Reseng reread Achilles’ death scene over and over. But he could not find a line about Achilles’ coming back to life.

Oh, no! That stupid Paris really did kill Achilles!

Reseng sat lost in thought until Old Raccoon’s study was pitch-black. He couldn’t yell, he couldn’t move. Now and then the rocking chair creaked. The books were submerged in darkness, and the pages rustled like dry leaves. All he had to do was stick his hand out to reach the light switch, but it didn’t occur to Reseng to turn on the light. He trembled in the dark like a child trapped in a cave teeming with insects. Life made no sense. Why had Achilles bothered to cover his torso in armor, when he should have protected his left heel, his one and only mortal weakness? Stupid idiot, even nine-year-olds knew better. It burned Reseng up to think that Achilles had failed to protect his fatal weak spot. He couldn’t forgive his hero for dying like that.

Reseng wept in the dark. On every page of the sea of library books that he was either itching to read or would eventually get bored enough to read, heroes and beautiful, charming women, countless people struggling to overcome hardship and frustration and achieve their goals, all died at the arrows of idiots because they failed to protect their one tiny weakness. Reseng was shocked at how treacherous life was. It didn’t matter how high you rose, how invincible your body was, or how firmly you clung to greatness, because all of it could vanish with a tiny, split-second mistake.

An overwhelming distrust in life overcame him. He might fall at any moment into any number of traps lying in wait. His tender life could one day be struck by luck so bad, it would leave him in utter turmoil; he would be gripped by terror he couldn’t shake off no matter how hard he fought. Reseng was possessed by the strange and unfamiliar conviction that everything he held dear would one day crumble in an instant. He felt empty, sad, and completely alone.

That night, Reseng sat in Old Raccoon’s library for a very long time. The tears kept falling, and he cried himself to sleep on Old Raccoon’s rocking chair.

BEAR’S PET CREMATORIUM (#ulink_9b6fe5fa-94b2-5382-8958-1791d8174aa8)

“If things don’t pick up, I’m in deep shit. Business has been so slow, I’m stuck cremating dogs all day.”

Bear flicked his cigarette to the ground. He was squatting down, and the seat of his pants threatened to rip open under his hundred-plus-kilogram frame. Reseng wordlessly pulled on a pair of cotton work gloves. Bear heaved himself up, brushing off his backside.

“Do you know some people are such morons, they’re actually dumping bodies in the forest? Your job doesn’t end when the target’s dead; you also have to clean up after yourself. I mean, what day and age is this? Dumping bodies in the forest? You wouldn’t even bury a dog out there. Nowadays, if you so much as tap a mountain with a bulldozer, bodies come pouring out. No one takes their job seriously anymore, I swear. No integrity! Stabbing someone in the gut and walking away? That’s for hired goons, not professional assassins! And anyway, it’s not like it’s easy to bury a body in the woods. A bunch of idiots from Incheon got caught dragging a huge suitcase up a mountain a few days ago.”

“They were arrested?” Reseng asked.

“Of course. It was pretty obvious. Three big guys carrying shovels and dragging a giant suitcase into the forest. You think people living nearby saw them and thought, Ah, they’re taking a trip, in the dead of night, to the other side of the mountain? Stupid! So my point is, instead of dumping bodies in the mountains, why not cremate them here? It’s safe, it’s clean, and it’s better for the environment. Business is so slow, I’m dying!”

Bear pulled on work gloves as he grumbled. He always grumbled. And yet this grumbling, orangutan-size man seemed as harmless as Winnie-the-Pooh. That might have been because he looked like Winnie-the-Pooh. Or maybe Pooh looked like Bear. Bear provided a corpse-disposal service, albeit an illegal one. Pets, of course, were legal. He was licensed to cremate cats and dogs. The human bodies were done on the sly. He was surprisingly cuddly-looking for someone who burned corpses for a living.

“I swear, you wouldn’t believe the things I’ve seen. Not long ago, this couple came in with an iguana. Had a name like Andrew or André. What kind of a name is that for an iguana? Why not something simpler, something that rolls off the tongue, like Iggy or Spiny? Anyway, it’s ridiculous the names people come up with. So this stupid iguana died, and this young couple kept hugging each other and crying and carrying on: ‘We’re so sorry, Andrew, we should have fed you on time, it’s all our fault, Andrew.’ I was dying of embarrassment for them.”

Bear was on a roll. Reseng opened the warehouse door, half-listening to his rant.

“Which cart?” he asked.

Bear took a look inside and pointed to a hand cart.

“Is it big enough?” Reseng asked.

Bear sized it up and nodded.

“You’re not moving a cow. Where’d you park?”

“Behind the building.”

“Why so far away? And it’s uphill.”

Bear manned the cart. He had an easy, optimistic stride that belied his penchant for grumbling. Reseng envied him. Bear didn’t have a greedy bone in his body. He wasn’t one to run himself into the ground trying to drum up more business. He got by on what he made from his small pet crematorium and had even raised two daughters by himself. His eldest was now at college. “I stick to light meals,” he liked to claim. “To stretch my food bill. I just have to hold out for a few more years, until my girls are on their own.” Bear spooked easily. He never took on anything suspicious, even if he needed the money. And so, in a business where the average life span was ridiculously short, Bear had lasted a long, long time.

Reseng popped open the trunk. Bear tilted his head quizzically at the two black body bags inside.

“Two? Old Raccoon said there’d be only one package.”

“One man, one dog,” Reseng said.

“Is that the dog?” Bear asked, pointing at the smaller of the bags.

“That’s the man. The big one’s the dog.”

“What kind of dog is bigger than a man?”

Bear opened the bag in disbelief. Inside was Santa. His long tongue flopped out of the open zipper.

“Holy shit! Now I’ve seen it all. Why’d you kill the dog? What’d it do, bite your balls?”

“I just thought it was too old to get used to a new master.”

“Well, look at you, meddling with the instructions you were given,” Bear said with a snigger. “You need to watch your step. Don’t get tripped up worrying over some dog.”

Reseng zipped the bag back up and paused. Why had he killed the dog? When he’d gone back to collect the old man’s body, the dog had been quietly standing watch. With his back to the sun, Reseng had looked down at the sunlight spilling into the dog’s cloudy brown eyes. The dog hadn’t growled. It was probably wondering why its master wasn’t moving. Reseng had stared at the dog, which was now too old to learn any new tricks. No one’s left in this quiet, beautiful forest to feed you, he thought. And you’re too old to go bounding through the forest in search of food. Do you understand what I’m saying? The late autumn sun cast its weak rays over the crown of the dog’s head. It had gazed up at him with those cloudy brown eyes as Reseng stroked its neck. Then he had raised his rifle and shot the dog in the head.

“Pretty heavy for an old man,” Bear said as he grabbed one end of the body bag.

“I told you, this one’s the dog,” Reseng grumbled. “That one’s the old man.”

Bear looked back and forth at the bags in confusion.

“This damn dog is heavy.”

After loading the bodies onto the cart, Bear looked around. The pet crematorium was a quiet place at two in the morning. Of course it was. No one would be coming to cremate a pet at this hour.

Bear opened up the gas valve and lit the furnace. The flames rose, peeling the black vinyl bag away from the two bodies like snakeskin being shed. The old man was stretched out flat, with the dog’s head resting on his stomach. As the furnace filled with heat, their sinews tightened and shrank, and the old man’s body began to squirm. It was a sad sight, as if he were still clinging to the world of the living. Was there even anything left for him to cling to? It didn’t matter. It was over. In two hours, he’d be nothing but dust. You can’t cling to anything when you’re dust.

Reseng stared at the contorted body. The old man had been a general. Throughout the three long decades of military rule in South Korea, he had been working behind the scenes, in the shadow of the dictator, drawing up lists of targets and orchestrating their assassinations. How had he pulled it off? It wasn’t easy back then for former members of the North Korean army to succeed in the South Korean army and harder still to earn a spot in the Korean Central Intelligence Agency. But he’d survived. He’d made it through the first dictator’s twenty years of ironfisted rule, the toppling of the regime, the coup d’etat that followed, and the next ten years under a new military regime. He’d survived the political monkey business and the unrelenting suspicion directed at former North Korean soldiers, and became a general. Whenever someone fell into disfavor with the dictator, this general with two shiny stars on his cap would seek out Old Raccoon’s library. He’d hand over the list with the target’s name on it and, most brazenly of all, use the people’s tax money to settle the bill.

But in the end, his own name had made it onto the list. That’s how it went. The good times came to an end sooner or later and, in order to survive, those who found themselves dethroned had to sort out what they’d done and sweep up the scraps. As always, time had a way of circling around and biting you on the ass.

Once, when Reseng was twelve, the old man had come to the library dressed in uniform. It was a fine uniform. The old man came right up to Reseng.

“What’re you reading, boy?”

“Sophocles.”

“Is it fun?”

“I don’t have a dad, so I can’t really understand it.”

“Where’s your dad?”

“In the garbage can in front of the nunnery.”

The general grinned, stars sparkling, and ruffled Reseng’s hair. That was twenty years ago. The little boy remembered that moment, but the old man had probably forgotten.

Reseng took out a cigarette. Bear lit it for him, took out one of his own, and started whistling birdcalls through a cloud of smoke. On his way out, Bear checked their surroundings again, as if expecting someone to appear suddenly. Reseng watched the bodies of the old man and the dog meld together in the heat.

A surprising number of idiots mistakenly thought they could pull off a perfect crime only if they personally disposed of the evidence. They would lug a can of gasoline to a deserted field and try to burn the body themselves. But cremation was never as easy as people thought. After messing around with trying to set the body on fire, they ended up with a huge, steaming lump of foul-smelling meat. Joke was on them. Any decent forensic scientist could take one look at that barbecue gone wrong and figure out the corpse’s age, sex, height, face, shape, and dentition. A body had to burn for at least two hours at temperatures well above thirteen hundred degrees inside a closed oven in order to be completely incinerated. Other than crematoriums, pottery or charcoal kilns, or a blast furnace in a smelting factory, it was very difficult to produce that kind of heat. That was why Bear’s Pet Crematorium stayed in business. The next important step was to grind the bones. Forensic scientists can determine age, sex, height, and cause of death from just three fragments of a pelvis. So any remaining bone or teeth had to be completely destroyed. Even the most finely ground bones still hold clues, and teeth maintain their original shape even under extreme conditions, including fire. So the teeth had to be pulverized with a hammer and the bone ash safely scattered. It was the only way to disappear your victim.

Reseng took out another cigarette and checked the time. Ten past two. Once the sun came up, he’d be able to finish work and head home. Sudden fatigue settled over his neck and shoulders. One night on the road, one night at the old man’s place, and now one night at Bear’s Pet Crematorium. He’d been away from home for three nights. His cats had probably run out of food … Reseng pictured his darkened apartment, the two Siamese yowling in hunger. Desk and Lampshade. Crazily enough, they were starting to take after their names. Desk liked to hunch over into a square, like a slice of bread, and stare quietly at a scrap of paper on the floor, while Lampshade liked to crane her neck and stare out the window.

Bear brought out a basket of boiled potatoes and offered one to Reseng. Just his luck—more potatoes. The six the old man had given him that morning were still in the car. Reseng was hungry, but he shook his head. “Why aren’t you eating? Don’t you know how tasty Gangwon Province potatoes are?” Bear looked puzzled. Why would anyone refuse something so delicious? He shoved an entire potato into his mouth and swigged a good half of the bottle of soju he’d brought out, as well.

“I cremated Mr. Kim here a while back,” Bear said, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Mr. Kim from the meat market?”

“Yup.”

“Who took him out?”

“I think Duho hired some young Vietnamese guys. That’s who’s taking all the jobs these days. They work for peanuts. Everywhere you look, it’s nothing but Vietnamese. Well, of course, there are also some Chinese, some defectors from the North Korean special forces, and even a few Filipinos. I swear, there are guys who’ll take someone out for a measly five hundred thousand won. Nowadays, assassinations cost practically nothing. That’s why they’re all at each other’s throats. Once Mr. Kim’s name made the list, he didn’t stand a chance.”

Reseng exhaled a long plume of smoke. Bear had no reason to lament the plummeting cost of assassinations. The more bodies there were, the better Bear fared, regardless of who carried out the killings. He was just humoring Reseng. Bear took another bite of potato and another swig of soju. Then he seemed to remember something.

“By the way, the strangest thing happened. After I had finished cremating Mr. Kim, I found these shiny pearl-like objects in his ashes. I picked them up to take a closer look, and what do you know? Śarīra. Thirteen of them, each no bigger than a bean. Crazy!”

“What are you talking about?” Reseng said in shock. “Those are only supposed to come out of the ashes of Buddhist masters. How could they come out of Mr. Kim?”

“It’s true, I swear. Want me to show you?”

“Forget it.” Reseng waved his hand in annoyance.

“I’m telling you, they’re real. I didn’t believe it at first, either. Mr. Kim—what’d everyone call him again? ‘The Lech’? Because he’d guzzle all those health tonics and stuff to increase his virility, then bang anything that moved? That’s what killed him, you know. Anyway, how could something as precious as śarīra come out of someone as rotten as he was? And thirteen, no less! They’re supposed to mean you’ve achieved enlightenment, but from what I see, it’s got nothing to do with meditating all the time, or avoiding sex, or practicing moderation. It’s more like dumb luck.”

“You’re sure they’re real?” Reseng still wasn’t convinced.

“They’re real!” Bear punctuated his words with an exaggerated shrug. “I showed them to Hyecho, up at Weoljeongam Temple. He stared at them for the longest time, with his hands clasped behind his back like this, and then he slowly licked his lips and told me to sell them to him.”

“What would Hyecho want with Mr. Kim’s śarīra?”

“You know he’s always chasing skirt, gambling and boozing it up. But that dirty monk’s got an itchy palm. He’s secretly worried what people will say about him if they don’t find śarīra among his ashes when he’s cremated. That’s why he’s got his eye on Mr. Kim’s. If he swallows them right before he dies, then it’s guaranteed they’ll find at least thirteen, right?”

Reseng chuckled. Bear shoved another potato in his mouth. He took a swig of soju and then offered Reseng a potato, as if embarrassed to be eating them all himself. Reseng looked at the potato in Bear’s paw and suddenly pictured the way the old man had talked to the dog, to the pork roasting over the fire, even to the potatoes buried under the ashes. You’d better make yourselves delicious for our important guest. That low, hypnotic voice. It struck him then that the old man must have been lonely. As lonely as a tree in winter, every last leaf shed, nothing but bare branches snaking against the sky like veins. Bear was still holding out the potato. Reseng was suddenly famished. He accepted the potato and took a bite. As he chewed, he stared quietly at the flames inside the furnace. Between the fire and the smoke, he could no longer tell what was old man and what was dog.

“Tasty, huh?” Bear asked.

“Tasty,” Reseng said.

“Not to change the subject, but why the hell is tuition so expensive now? My older daughter just started university. I’ll need to burn at least five more bodies to afford her tuition and rent. But where am I going to find five bodies in this climate? I don’t know if it’s just that the economy’s bad or if the world’s become a more wholesome place, but it’s definitely not like the old days. How am I supposed to get by now?”

Bear frowned, as if he couldn’t stand the thought of a wholesome world.

“Maybe you should think about those pretty daughters of yours and go straight,” Reseng said. “Stick to cremating cats and dogs instead, you know, more wholesome like.”

“Are you kidding? Cats and dogs would have to get a lot more profitable first. I charge by the kilo for cremating pets, and nowadays everyone’s into those tiny ratlike dogs. Don’t get me started. After I pay my gas, electricity, taxes, and this, that, and everything else, what’s left? If only people would start keeping giraffes or elephants as pets. Then maybe Bear would be rich.”

Bear shook the soju bottle and emptied what was left into his mouth. He stretched. He looked worn-out. “So should I sell them?” he asked abruptly.

“Sell what?”

“C’mon, I already told you! Mr. Kim’s śarīra.”

“May as well,” Reseng said irritably. “What’s the point of holding on to them?”

“That so-called monk offered me three hundred thousand won for them, but I feel like I’m getting ripped off. Even if they did come out of Mr. Kim’s garbage can of a body, they’re still bona fide śarīras.”

“Listen to you,” Reseng said. “Going on as if they’re actually sacred.”

“Should I ask him to bump it up to five hundred thousand?”

Reseng didn’t respond. He was tired, and he wasn’t in the mood to joke anymore. He stared wordlessly into the fire until Bear got the hint. Bear gave his empty soju bottle another shake, then went to get a fresh one.

White smoke spewed out of the chimney. Every time he dropped off a body for cremation, Reseng got the ridiculous notion that the souls of those once-hectic lives were exiting through the chimney. A great many assassins had been cremated there. It was the final resting place for discarded hit men. Hit men who’d messed up, hit men tracked down by cops, hit men who ended up on the death list for reasons no one knew, and assassins who’d grown too old—they were all cremated in that furnace.

To the plotters, mercenaries and assassins were like disposable batteries. After all, what use would they have for old assassins? An old assassin was like an annoying blister bursting with incriminating information and evidence. The more you thought about it, the more sense it made. Why would anyone hold on to a used-up battery?

Reseng’s old friend, Chu, had been cremated in this same furnace. Chu was eight years older, but the two of them had been like family. With Chu’s death, Reseng had sensed that his life had begun to change. Familiar things suddenly became unfamiliar. A certain strangeness came between him and his table, his flower vase, his car, his fake driver’s license. The timing of it all was uncanny. He had once looked up the man whose name was on his stolen driver’s licence. A devoted father of three and a hardworking and talented welder, according to everyone who knew him, the man had been missing for eight years. Maybe he had ended up on a hit list. His body might have been buried in the forest or sealed inside a barrel at the bottom of the ocean. Or maybe he had even been cremated right here in Bear’s furnace. Eight years on, the family was still waiting for him to come home. Every time he drove, Reseng joked to himself: This car is being driven by a dead man. He felt that he lived like a dead man, a zombie. It only made sense that he was a stranger in his own life.

Two years had passed since Chu’s death. He’d been an assassin, like Reseng. But unlike Reseng, Chu hadn’t belonged to any particular outfit; instead, he’d drifted from place to place, taking on short gigs. The Mafia had a saying: The most dangerous adversary was a pazzo, a madman. A person who thought they had nothing to lose, who wanted nothing from others and asked nothing of him- or herself, who behaved in ways that defied common sense, who quietly followed her or his own strange principles and stubborn convictions, which were both inconceivable and unbelievable. A person like that would not be cowed by any formidable power. Chu had been that kind of person.

On the other hand, it was easy to deal with adversaries who were backed into a corner and desperate not to lose what they had. They were the plotters’ favorite prey. It was obvious where they were headed. They ended up dead because they refused to acknowledge, right up to the very end, that they could not hold on to whatever it was they were trying to hold on to. But not Chu. Chu had been out to prove that this ferocious world with its boundless power could not stop him as long as he desired nothing.

Chu had been prickly, but his work was so clean and immaculate that Old Raccoon had usually given him the difficult assignments. He’d wanted to make Chu an official member of the library and had warned him, “Even a lion becomes a target for wild dogs when it’s away from its pride.” Each time, Chu had sneered and said, “I don’t plan on living long enough to turn into a cripple like you.”

Despite not belonging to any one outfit, Chu had lasted for twenty years as an assassin. He’d done all sorts of dirty work, taken government jobs, corporate jobs, jobs from third-tier meat-market contractors, no questions asked. Twenty years—it was an impressive run for an assassin.

But then one day four years ago, Chu’s clock had stopped. No one knew why. Even Chu had confessed to Reseng that he didn’t understand why it had happened, why his clock had suddenly stopped after running so faithfully for twenty years. What led up to it was that Chu decided to let one of his targets go. She was no one special, just another twenty-one-year-old high-priced escort. Shortly after, a news story came out about a certain national assemblyman who had leaped to his death. He’d been hounded by accusations of bribery, corruption, and a sex scandal involving a middle schooler. There was no way that a lowlife like him who enjoyed sex with middle school girls had committed suicide to preserve his honor, which he’d long since done a great job of destroying on his own. Every plotter who saw the news must have instantly thought of Chu. And Chu didn’t stop there. He also went after the plotter who’d put out the contract on the escort. But he failed to track the plotter down. Not even the great Chu could pull that off. By then, Chu was a wanted man. It has to be said that plotters spend more time on finding safe hideouts for themselves and ensuring their own quick exits than on planning hits.

The plotters’ world was one big cartel. They had to take out Chu, but not for anything as flimsy as pride. There was no such thing as pride in this business. They had to take him out so as not to lose customers. Like any other society, their world had its own strict rules and order. Those rules and order formed the foundation on which the market took shape, and then in streamed the customers. If order fell, the market fell, and if the market fell, bye-bye customers. Chu had to have known that. The moment he made up his mind to save the woman, he signed his own death warrant. Chu risked everything to save one unlucky prostitute.

It took the meat market’s trackers less than two months to find her. She was hiding in a small port city. The high-class call girl who’d once entertained only VIP clients in four-star hotels was now selling herself to sailors in musty flophouses. If she’d holed up quietly in a factory instead of going to the red-light district, she might have dodged the trackers a little longer. But she’d ended up on the stinking, filthy streets instead. Maybe she’d run out of money. Since she’d had to leave Seoul in a hurry, she would’ve had no change of clothes and nowhere to sleep. Plus, it was winter. Cold and hunger have a way of numbing people to abstract fears. She might have thought she was going to die anyway, and so what difference did it make? It’s hard to say whether it was stupid of her to think like that. She couldn’t possibly have enjoyed whoring herself out in a port city on the outskirts of civilization, sucking drunk sailor dick for a pittance. But she would’ve felt she had no other choice. All you had to do was look at her hands to understand why. She had slender, lovely hands. Hands that had never once imagined a life spent standing in front of a conveyer belt tightening screws for ten hours a day, or picking seaweed or oysters from the sea in the dead of winter. Had she been born to a good family, those hands would have belonged to a pianist. But her family wasn’t all that good, and so she’d been whoring herself out since the age of fifteen.

She must have known that returning to the red-light district meant she wouldn’t last long. But she went back anyway. In the end, none of us can leave the place we know best, no matter how dirty and disgusting it is. Having no money and no other means of survival is part of the reason, but it’s never the whole reason. We go back to our own filthy origins because it’s a filth we know. Putting up with that filth is easier than facing the fear of being tossed into the wider world, and the loneliness that is as deep and wide as that fear.

Old Raccoon had summoned Reseng as soon as the plotter’s file arrived. Reseng found him sitting at his desk in his study, leafing through the document. He assumed it contained the woman’s photo, her address, her hobbies, her weight, her movements, and the names of all the people related to or involved with her in any way—in other words, all the information needed to kill her. It would also state the designated manner of her death and the method of disposal of the body.

“I don’t know why they’re wasting money on this. Says she’s only thirty-eight kilos. Break her neck. It’ll be as easy as stepping on a frog.”

Old Raccoon thrust the file at Reseng without looking at him. Reseng raised an eyebrow. Was stepping on a frog that easy? Old Raccoon had a habit of making cynical jokes to hide his discomfort. But Reseng wasn’t sure whether what bothered Old Raccoon was having to kill a twenty-one-year-old girl—and one who weighed only thirty-eight kilos, at that—or if his pride was hurt at having to accept a low-paying contract, though he knew full well the library needed the business.

Reseng flipped through the file. The woman in the picture looked like a Japanese pop star. It said she was twenty-one, but she didn’t look a day over fifteen. Reseng had never killed a woman before. It wasn’t that he had some special rule against killing women and children; it was simply that his turn hadn’t come around yet. Reseng had no rules. Not having rules was his only rule.

“What do I do with the body?” Reseng asked.

“Take it to Bear’s, of course,” Old Raccoon said irritably. “What else would you do? String her up at the Gwanghwamun intersection?”

“It’s a long way from where she is to Bear’s place. What if I get pulled over while she’s in the trunk?”

“So lay off the booze and drive like a kitten. It’s not like the cops are going to force you to pull over and claim you shot at them. They’ve got better things to do.”

His voice dripped with sarcasm. That was also his way of disguising anger. Reseng just stood there, not saying a word. Old Raccoon flicked his wrist to tell him to get lost, then got up, pulled a volume of his first-edition Brockhaus Enzyklopädie from the shelf, set it on a book stand, and began reading out loud, mumbling the words under his breath, completely indifferent to Reseng, who was still standing in front of him. He had been rereading it recently. When he finished, he would reread the English edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Old Raccoon’s awkward, self-taught German filled the room. As Reseng opened the door and stepped out, he muttered, “No real German would understand a word of that.”

Old Raccoon had long ago stopped stocking his personal shelves with anything that wasn’t a dictionary or an encyclopedia. As far as Reseng could remember, he’d refused to read anything else for the last ten years. “Dictionaries are great,” he’d explained. “No mushiness, no bitching, no preachiness, and, best of all, none of that high-and-mighty crap that writers try to pull.”

The port city where the woman was hiding looked as run-down as a diseased chicken. The once-bustling city that had kept the Japanese imperial forces supplied with war munitions had been in decline ever since liberation. Now it seemed nothing could turn it around. Reseng got off the express bus and headed for the parking lot, where he looked for a license plate ending in 2847. At the very end of the lot was an old Musso SUV. He took the keys out of his pocket, opened the door, and got in. As soon as he started the ignition, the low fuel warning light blinked on.

“Son of a bitch left the tank empty,” Reseng muttered in irritation at the stupid plotter, wherever and whoever he was.