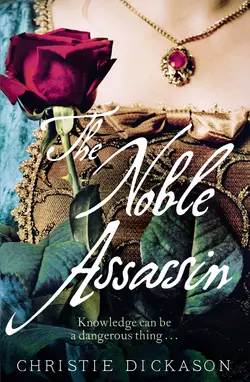

The Noble Assassin

Christie Dickason

A thrilling account of one of English history’s most daring women, who risked everything in the dark days leading up to the Civil War. The perfect novel for fans of Suzannah Dunn and Phillipa Gregory.Court beauty, Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford, feels frustrated by life with her weak husband. Poverty stricken, they are confined to their country estate and excluded from court life in London after he disastrously allies himself against Elizabeth I.Now, some years later, James I is seated on the English throne. His daughter, Elizabeth Stuart, former confidant of Lucy, has married the King of Bohemia. The precarious political situation in Europe is fraught, setting father against daughter. When Elizabeth and her husband are deposed, exiled and forced on the run, James is in no mood to come to his daughter’s aid.Hearing of Elizabeth’s predicament, Lucy sees an opportunity to re-establish the Bedford name and offers herself as a peace envoy between the two parties. Setting out on a daring mission across the channel, Lucy discovers she is being manipulated by unscrupulous men, not least the calculating and darkly handsome Duke of Buckingham.Can Lucy tread this most dangerous path, or by risking everything, will she pay the ultimate price?

The Noble Assassin

CHRISTIE DICKASON

Dedication (#ulink_e68cc782-0ff5-5177-8e11-39efc35d80bd)

For John

Contents

Cover (#ud08e1437-6848-54c7-86e3-f9d0225cdd64)

Title Page (#u86ec626f-7aee-51b0-9ec3-a09d28ef204e)

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part Two

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Epilogue

The People In THE NOBLE ASSASSIN

Author’s Notes

By the same author

Some Helpful Books

The Noble Assassin – TIME LINE

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Thank you to:

John Faulkner, my personal Google

Stephen Wyatt, my creative SOS, as always

Olena Kostovska

Lindsay Smith

Stephen Siddall

Tom French for IT support and rescue

Emma Faulkner, for the title

Orly, for listening, among much else

Leonardo, Giuseppe and Rosa Giannini for

my office away from home

Sarah Ritherdon and Victoria Hughes-Williams at

HarperCollins

My agents, Robert Kirby and Charlotte Knee

Jon M. Moore, Chief Executive, Moor Park Golf Club

The Museum of Richmond, Richmond Surrey

The Richmond Reference Library

Jeremy Preston and the staff of East Sheen Library

for invaluable support in research, readings, and

readership involvement

(And, welcome to Matilda, who arrived in this world

just before I hit ‘SEND’.)

Part One (#ulink_e5c13bd6-8ce8-5d76-af2d-489dec14b617)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_25f4fb37-780e-581d-927c-81eb76778043)

LUCY – MOOR PARK, HERTFORDSHIRE, NOVEMBER 1620

The air is so cold that I fear my eyelashes will snap off like the frozen grass. Only my two youngest, most eager hounds have left the fireside to bound at my side.

I do not want to die. But I cannot go on as I am, neither. I ride my horse closer to the edge of the snow cliff. I imagine turning his head out to the void and kicking him on. I imagine the screams behind me.

We would fly, my horse and I, falling in a great arc towards the icy River Chess far below. My hair would loosen and tumble free. His tail and my darned red gown would flutter like flags.

Then we would begin to tumble, slowly, end over end, like a boy’s toy soldier on horseback, my bent knee clamped around the saddle horn, his legs frozen in mid-gallop. The winter sun reflecting off his black polished hoofs. My last unsold jewels scattering through the air like bright rain. For those frozen dreamlike moments, my life would again be glorious.

I feel the alarmed looks being exchanged behind me on the high, snowy ridge, among the moth-eaten furs and puffs of frozen breath. I quiver like a leashed dog, braced for the first voice to cry, ‘Take care!’

I walk my horse still closer to the edge.

It would be so easy.

I look down again at the river. Why not? What is left to lose now?

The in-drawn breath of that vast space pulls at me. The serrated edges of the snow cliff glisten, sharp enough to slice off Time.

Welcome, the space whispers. Below me, I see the smiling faces of my two dead babes. Welcome. I see the face of my poet, my only love, now dead to me.

One kick, then no more fighting. No more debts. No more loss. No more of the scorn and silence already denying that I am alive.

Even my Princess is gone from England.

I listen to the uneasy stirring behind me. Who would break first and call me back?

You can die from lack of a purpose to live.

‘Your Grace . . .’ The waiting gentleman speaks quietly lest he startle me, or my horse, and send us over the edge. Speaking carefully, as if I were poor, maimed, self-indulgent Edward, who suffers so nobly before witnesses then beats his fist against his chair when he thinks himself alone.

The cold air is a knife in my chest. The sun on the snow blinds me. I am made of ice.

I let my small band of attendants hold their breaths by the edge of the snow cliff. They should be grateful to me for this small gift of fear, I think. Salting the bland soup of their day.

I look down at the river again. Edward is wrong to say that I lie to myself. I face the reality in front of me. Listen to its melody. Then I rewrite it, sometimes on paper, sometimes only in my head. I give it more beauty, or terror or meaning. I tell the story better. But I never deceive myself as to which is which.

For instance, I can see that the scene I am now writing in my head is impossible. The fall would be messy, not glorious. Almost certainly, the horse would have to be shot. I would land at the bottom broken but still breathing. And then I would become a captive with my husband in his fretful rage.

I see the pair of us, invalids side-by-side in our fur rugs, dropping malice as the stars drop the dew until we die.

I still brim with unwritten words, unsung music, unplanted gardens. I still keep most of the looks and all of the wit that had made me the darling of the Whitehall poets. I feel like a piece of verse begun but not finished. There is one poet who could have written me but never will.

In the void below me, I see him striding up and down the gravel path of my lost garden in Twickenham, stirring the air, reciting a poem born from the passionate union of our thoughts. I hear words I had offered him, whole lines, even. An easy rhythm where my ear had pointed out a stumbling line for him to revise. All now made his own. He recites the completed poem for the first time, to me alone, too intent to notice that spray from the fountain spangles his dark hair and coat with sparkling diamond chips.

He glares up at the sky and down at the gravel path. I watch his clenched hands spring open to mark each stress of his metre. Watch his long fingers and feel them on my skin. His words sail out of his body on the fierce current of his breath into the wide air of the universe. I imagine them sailing on past the moon, past the sun, until they reach the farthest heavens to lodge as new stars. He comes to the end of the poem, listens for a moment to its last echo in his head, then turns to look at me, almost with fear. Was it good?

I have lost him along with all the rest.

When I had been the Queen’s favourite, she bathed me in her generosity. Passing it on with an open hand, I became that bountiful goddess known as a patron, a source of prizes, favours and preferment.

But my fortunes had declined with the Queen’s health and the vigour of her court. My husband and I never recovered from his fine for treason. I often spent what I did not have. Our growing debts had forced me to sell the lease of my Twickenham garden to that reptile Lord Bacon. When the Queen died, almost two years past, I was finished. Her court was dissolved. I lost my place and the wealth that went with it. I could no longer afford to be patron, to my poet or anyone else. Now I am branded a ‘court cormorant’, a beggar, wife of a debtor, a woman of no use to anyone, burying her shame in the country. Like the pox, my fall from grace threatens to infect others.

What remains for me? Why not open my wings and fly? If not here, somewhere higher and more certain.

My gelding suddenly shies away from the shining ice edge.

I lean forward and pat his neck. ‘Don’t fear,’ I murmur. ‘When I jump, I won’t take you with me. I swear it. Nor anyone else.’

Not today.

But I have never yet given up on anything I set my mind to.

I will do it, I promise myself. Soon.

My poor hounds have begun to shiver, up to their shoulders in the drifts.

I turn my horse’s head to let him begin to pick his way back down along the icy track towards Moor Park, with the dogs racing ahead and my attendants behind, no doubt relieved. I press my old beaver muff to my cold face then bite savagely into the fur like a hound on a hare’s nape.

I have little patience with wilful misery, least of all my own, but I see no way out for me now. I clench my teeth on the side of my hand, deep inside the muff. I want to throw back my head and howl. To crack open the steady deadly progress of time and set loose demons and angels with flaming swords. I would welcome the novelty of a second Great Flood, cheer on the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Anything to change what my life has become.

When I drag my frozen skirts back to the fire in the hall at Moor Park, I learn that those demons and angels have already escaped. As my skirts steam and drip and my shivering grey hounds curl close to the flames beside their fellows, I listen with horror to Edward’s urgent report.

The dark, gaunt Horseman of War had heard my desperate plea.

‘There is war in Bohemia.’ My husband can scarcely conceal the pleasure he takes in telling me.

I didn’t mean it! I think. Not like this! Not Elizabeth!

‘They lasted scarcely a year on the Bohemian throne, your English princess and her little Palatine husband.’ He shakes his head and waits for me to ask if she is dead.

Queen Anne’s daughter Elizabeth. My father’s former charge, raised in our home at Combe Abbey. Elizabeth Stuart, the only woman I love who is still left alive. In spite of her younger years, she could always match me thought for thought. At times, she had left me, the older girl, laughing in her wake.

When I remain silent, he can’t contain himself any longer. ‘All reports say the Hapsburg armies have invaded Prague, routed the new young King’s Protestant forces and arrested the rebel leaders.’

‘How certain is this news?’

‘A courier arrived from my cousin today.’

‘What of the King and Queen?’ I ask when my voice is again under control. My Elizabeth and her Frederick, who had been pressed into accepting the crown of Bohemia.

‘Fled, I’m told . . . and still in flight. Declared outlaws by the Hapsburgs, under Ban of the Empire.’

I want to hit him for the pleasure in his voice. ‘Will England go to war to save her?’

‘That’s for her father to decide.’ I have asked a foolish question. Then he smiles and shrugs. ‘King James is England’s self-styled “rex pacificus”. Draw your own conclusions.’

‘There’d be no honour in his “peace” now.’ I wish I could say that my feelings at that moment are pure, generous and patriotic, but honesty insists otherwise. A sudden jolt of excitement runs through my horror.

‘The Bohemians might prefer to call their leaders “heroes” not “rebels”,’ I say mildly while my racing thoughts drown both Edward’s voice and his quiet malice.

I survived my first seven years of marriage chiefly by pretending to ignore my husband. He had soon proved to be a master of the puzzled tone, the helpless shrug, the meaningful glances over my head. He let my words fall to the floor as if they had no meaning. Or he would seize on one and examine it with puzzled incomprehension before tossing it away. Or he shook his head sadly and told me what I had meant to say. In the company of other men, he ignored me altogether. When he managed to provoke me past endurance, he would smile with satisfaction. Look at her! See what a harridan I have married!

Having once again failed to goad me into an unseemly outburst, my husband now purses his lips. I scarcely notice.

If what Edward tells me is true, I know that the future of England has just changed. My future could change with it. I see escape from Edward and from Moor Park. I see the return of warmth and true companionship. I see purpose for my life again. I confess that I begin to listen to his news of unfolding disaster in Bohemia with a heart turned suddenly light with renewed possibility.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_76e2862d-fd07-5429-a14e-bc9019b02876)

ELIZABETH STUART – PRAGUE, BOHEMIA, NOVEMBER 1620

In the royal palace in Prague, the King, Queen and guests pretended to eat. The young, Scottish-born Queen of Bohemia, Elizabeth Stuart, jumped at a sudden boom and spilled the sauce from her silver spoon. She set the spoon down on her plate and picked up her French fork. She looked at the fork, unable to remember what she should do with it. With its two long sharp tines, it resembled a weapon. She found herself gripping the gold mermaid of its handle in her fist.

They no longer pretended to converse, in any of the several languages spoken around the table. All words had now deserted them. Up and down the long polished table, people stared at their food as if puzzled by it or chewed on morsels that they forgot to swallow. All their senses seemed to have deserted them except that of hearing. Sir Edward Conway, one of the two ambassadors sent by James from England to parlay for peace with the Hapsburg enemy, sat with one hand at his hip, resting on an absent sword hilt. Even the servers standing behind each chair forgot to offer the food they held, frozen in listening.

Cannons had begun to boom far too close, from the west.

The child in her womb jumped.

Elizabeth could almost have persuaded herself that the guns were summer thunder bouncing off the mountains.

‘It’s noisy for a Sunday that was meant to be a day of truce,’ said the other English ambassador, Sir Richard Weston.

‘We’re high here,’ said Elizabeth. Her unspoken meaning – the Hradcany Palace, home to the King and Queen of Bohemia, sat on a rocky summit high above the Vltava river. Sounds from far away reached them with unnatural clarity. Therefore, the fighting was not as close as it sounded. She was reassuring her white-faced husband as much as the rest of them.

Her husband shook his head. Frederick, elected King of Bohemia for a little more than a year, had been weighed down beyond his strength from the age of sixteen by his leadership of the German Union of Protestant Princes. ‘They’re fighting on the White Mountain. I should be there, not at table.’ He stood abruptly. Fabric rustled and stool feet squeaked on the stone floor as everyone else rose with him. Then he paused uncertainly, head lifted, listening to the sounds of the battle.

The forces of the mighty Catholic Hapsburg Empire had engaged Frederick’s twenty-five thousand German mercenaries and Protestant Bohemians less than half an hour’s ride from the city.

‘But we have them outnumbered,’ said Frederick. ‘They’re only seventeen and a half thousand men.’

‘Go tell the stables to prepare His Majesty’s horse,’ Elizabeth ordered a serving groom.

The fear and relief on the boy’s face as he ran from the hall made her question whether he would take her order to the stables or flee from the castle entirely.

‘You must go arm yourself, my love,’ she told her husband quietly.

‘Oh, Lizzie!’ He looked at her with terror in his large dark eyes. ‘I fear that we can’t . . .’

‘I shall come serve as your armourer, myself.’ Elizabeth, First Daughter of England and child of its King, married to Frederick at fifteen, now the twenty-four-year-old Serene and Puissant Queen of Bohemia, took her King firmly by the arm and led him towards the door of the great hall.

‘You must leave Prague at once,’ said Frederick. ‘Go early to Bresslau.’ She was to spend her confinement in Bresslau. He had already ordered some of her furniture sent there.

She shook her head. ‘I stay here in Prague as long as you do.’

The doors had no sooner closed behind him than they opened again on bad news. The arriving messenger smelled of gunpowder, blood and horse. Elizabeth could scarcely hear his words through the thunder of cannons inside her head.

The messenger finished speaking.

Behind her, Elizabeth heard screams and the crash of falling stools. Courtiers ran past her out of the hall, pushing and jostling in the door.

‘Where are the other German princes?’ she demanded. ‘Our allies? Where’s Thyssen? Bethlem Gabor and his Hungarians? Are they on their way to relieve us?’

‘I don’t know, Your Majesty. But our army is on the run with the Imperial army on their heels.’ The messenger looked back at the door.

‘Go run with the rest of them, then!’ she said with contempt.

She stood in a small still centre of the maelstrom unleashed by his message. She saw a man run by her carrying two jewelled goblets from the royal table.

‘Your Highness, do you wish me to take your knives and forks?’ A voice at her elbow, her chief lady-in-waiting, balanced on her toes, wanting to run, but still at her English mistress’s side.

She looked back and saw a waiting woman rolling up one of the Russian carpets on the royal dais.

Reality hit her. A hostile army was about to invade this very space in which she was standing.

Feeling unnaturally calm, she nodded at her lady-in-waiting. ‘And all my jewels.’ She turned to the two English ambassadors, still present, heads together. ‘You must return to England and tell my father to send soldiers and money at once!’

Weston nodded, but looked away.

Into the maelstrom, a white-faced, trembling Frederick returned. ‘It’s too late, Lizzie. My army has deserted. Even Anhalt and Hohenlohe were clamouring at the city gate in the midst of their own soldiers, begging to be let back inside the walls. We must all leave Prague now!’

‘Then you can ride with me and the children,’ Elizabeth said. ‘We will need you and the castle militia to protect us.’

Scarcely a year after she had arrived in Prague as the new queen of Bohemia, Elizabeth packed to leave again.

First, the children. The boys must not become Imperial captives! Thank God the Crown Prince had already been sent to safety in Berlin! Get the others away from here! Look to their needs. Clouts for the coming babe, petticoats, toy soldiers, cups and spoons, coverlets, shoes and boots, bread and wine. Gloves.

Oh God! She could not think with that thunder in her head.

Cradle . . . a welcoming gift from her new people less than a year ago, for Rupert her first Bohemian child . . . Too heavy to carry?

She looked out of a high window as if expecting to see Hapsburg soldiers climbing towards the castle.

Snow, falling. Great pillows of snow fell onto the thick coverlet that already hid steps and cart tracks. The staircase down to the river looked like a smooth white slope. They would have to take the wagons and carriages the long way round, to the north where the land rose more gradually, towards the advancing enemy, before curving south again.

Money chest, she thought. Petticoats, riding boots. Fill brass warming pans with charcoal. Likewise the iron heaters for the carriages. Feather mattresses . . . Leave all farthingales behind to save room in the carriages.

All the time, her ears listened to the gunfire, growing closer.

‘Madam . . .! Madam!’ cried frightened voices. ‘Do you want me to take . . .?’

No time. They must leave now!

The First Daughter of England, child of the would-be Peacemaker English King, could not become a prisoner-of-war.

Apart from all else, she thought, my father would never forgive me for forcing him to take a stand. Not after he had advised Frederick to stay at home in Heidelberg and refuse the Bohemian crown.

‘Into the second and third carriages,’ she ordered the children’s nurses with their bundles. Where was the castle steward who should be overseeing this rout?

Food! she thought. And ale. Who was supervising the packing of food and drink for them all?

How many were they?

She sat on a packed chest, pulled up her skirts and hauled on her riding boot unassisted. Her ladies were all running with loaded arms. Or had vanished.

And who can blame them? she thought. She hauled on her other boot.

How far away was her intended refuge in Bresslau? Too far. The mountains would be impassable in this weather.

Our departure from Prague is merely a series of problems to be solved, she told herself. But they all needed solving at once. There was no time . . .

Think!

Food, she thought again. Don’t let yourself become distracted from the most important things.

She found the steward in the kitchen courtyard, making a tally of flitches of bacon and smoked hams as they were thrown into carts.

‘Where are your clerks?’ she asked.

He gestured at the mêlée around them and shrugged. ‘I want to be certain, myself . . . Bread already in that cart, madam.’ He pointed, then ran across the courtyard to chivvy along two men who were loading barrels of ale onto another cart. She saw a guardsman carrying a pike.

The armoury! She ran back to the steward. ‘Weapons,’ she said. ‘We must not leave weapons for the enemy to take.’ He nodded and pointed at bundled pikes and stacked shields waiting to be loaded.

We must go to Berlin, she decided. A long ride in this weather. But once there, they would find warmth and food and safety, for a time at least. Time to think about their suddenly unthinkable situation. She didn’t entirely believe it, even now.

Snow was already blanketing the contents of the carts. Churned-up slush washed past the ankles of her boots as she ran back into the castle to oversee her own chests, which were being loaded onto carts in the main courtyard. And her money chest and jewel case, stowed in her carriage at the front of the forming line. And the chest holding state papers.

Letters!

She turned to go back to her apartments, but a militiaman blocked her way.

‘No time, madam,’ he said. ‘You must leave now!’ The militiaman disappeared again.

She lifted her head. The cannons had stopped. For a moment, she felt an intense silence, as if the world had stopped turning. Then shouts and gunfire, and the screaming of wounded horses arrived on the wind, far too close.

Children already in their carriage. Shadowy heads and the heads of their nurses . . .

Cloak. Gloves. Money pouch tied under her soft riding skirts, over her seven-month bulge of belly. Dagger.

She clambered up into her carriage. Two women in it already. Her chief lady-in-waiting sat huddled under a bearskin rug with Elizabeth’s jewel case in her arms.

She helped to wrap Elizabeth in another rug. ‘Put your feet here, my lady.’ Elizabeth lifted her soaked boots onto the iron warming pan of burning charcoal. Melted snow was already making a puddle on the floor of the coach. She lifted back the curtain over the window to watch their departure. In both directions along the line, indistinct figures took shape in the snow then disappeared again, both mounted and on foot. Though the light felt unnaturally bright, she could scarcely see the walls of her adopted home.

Frederick appeared on his horse, armed for war. ‘I’m giving the order to go forward.’

She nodded at him through the open square of the window. ‘To Berlin.’

He leaned close and said quietly, ‘I’m sorry, Lizzie.’ ‘Don’t be a fool,’ she said. ‘We’re having another adventure.’

‘Do you think we’ll survive?’

‘I shall. And I don’t like the prospect of widowhood, however you imagine you might arrange it.’

He nodded, then swallowed. ‘If I could face your father to win you, why should I fear the army of the Hapsburg emperor?’

She smiled more brightly than his sally warranted, to reward him for attempting it at all. They clasped gloved hands through the carriage window. The ends of his dark curly hair were tipped with snow. Flakes were already settling on her skirts.

‘I’ll see you safely to Berlin,’ he said. ‘Then I must ride north to try to raise more men. I’ve learned that it was only the mercenaries who deserted, not our local troops. The people of Bohemia will defend us yet.’

‘And I will give you all my jewels to pawn to pay them.’ She held up the curtain and watched him dematerialise again as he rode away to the head of the long line.

Her carriage jolted forward, throwing her back against the seat. Behind her the shouts of the drivers travelled like a wave back along the line of carts and carriages. The carriage dropped suddenly as its wheels slid into buried ruts in the frozen mud. The seat banged the ends of their spines.

‘Dear Lord!’ exclaimed her lady-in-waiting. Elizabeth heard the horses groaning and blowing. Behind them, oxen protested. The carriage swayed and creaked like a ship in a storm. She dropped the curtain across the window. She needed both hands to clutch the front of the seat. The interior of the coach was now dark and no warmer, but the curtain at least kept out the snow.

‘Stop!’ A scream rose behind her. She leaned from the window again, into the icy needles of snow. A voice fought its way to her against the wind, through the shouts of the carters and coachmen and the protests of the horses. ‘Wait, Your Majesty . . .!’

Then the wind blew the voice into ragged tatters.

‘Stop!’ she cried. Cold air filled her open mouth. Her teeth ached from the cold. ‘Who is that?’

It’s too late, she thought. We’ve been overtaken.

‘Your Majesty!’ The voice shouted again.

Then she saw the man staggering and sliding through the snow alongside the track. Not a Hapsburg soldier: one of Frederick’s gentlemen. Clutching a bundle of cloth in his arms, he fought his way forward towards her carriage.

‘Your Majesty,’ he shouted again. He overtook the carriage behind hers. ‘Dohna, the King’s Chamberlain went back . . .’ He slipped and almost fell into a drift. ‘. . . into the castle to check that everyone was gone . . . That nothing valuable had been left . . . Look!’ He stumbled alongside, panting, beneath the carriage window, holding up the bundle of cloth. ‘I was in the last carriage. Dohna threw him in . . . left behind in the nursery!’

The bundle gave an angry wail.

The carriage slid sideways. Elizabeth nearly fell from the window as she reached out. The man shoved the bundle up into her hands just before he fell. Elizabeth fumbled, re-gripped and fell back into her seat. It was her youngest son.

‘Rupert!’

One of her ladies whimpered.

Alive. Very much alive. She could now hear his steady screams and feel the pumping of his breath. The scrap of his face that showed amongst the wrappings was brick red. His body arched with rage.

Frightened faces stared back at her across the carriage.

‘Where’s the prince’s nurse?’

But she already knew. She remembered now. She had not seen Rupert’s nurse waiting with the others. The woman had fled.

Behind her she heard the coachmen and carters cursing and shouting as their beasts piled into the ones in front of them, trying not to run into her carriage.

‘Onwards,’ she shouted through the window and heard the order reverse itself back down the line. As the carriage lurched forward again, she braced herself against the motion, with her son pressed against her guilty heart. For the first time, she truly felt the enormity of what had happened to them all, of what was happening, and would go on happening. However calm she had pretended to be, what had happened was so terrible that it had almost made her leave behind her youngest child.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_92c099b4-8dbe-5a67-a875-0ac09a31f367)

LUCY – MOOR PARK, 1620

I lie in my cold bed, breathing out warm clouds, my feet close to the iron brazier filled with coals at the end of the mattress. My maid Annie snores gently from her pallet on the floor. A nodding house groom tends the fire.

I think about the news Edward has given me. The daughter of the King of England – my Elizabeth – is in flight, pursued by the armies of a Catholic empire that rules most of northern Europe from Russia to Flanders, only a short sail away across the North Sea. The long rumbling of war on the Continent between Catholic and Protestant powers has suddenly turned to the thunder of guns that can be heard in England.

She will be frightened and confused, though, as always, she will seem to command. She will fear for the children. They are all in danger.

I know I should not feel happy. How dare I rejoice?

I duck down under the covers to warm my hands on the brazier, curling like a cat in the small warm cave.

I am being given another chance. If I can think how to take it.

The next morning I rise as if the world were not changing. I dress, eat my frugal breakfast of bread and small beer. Wearing old fur-lined gloves with the fingers cut off, I sign orders to buy sugar and salt that we can’t afford. I approve the slaughter of eight precious hens. I count linens as they come back from the washhouse, and the remaining silver returned from being washed and polished in the scullery. While Lady Agnes frowns at a peony she is working in tiny knots to hide a patch on a sleeve, I try to do my own needlework. But I prick myself so often that I throw the torn pillow cover across the room.

Agnes tightens her mouth and ignores me. After a time, I pick up the pillow cover myself.

After the midday meal, I write to my old friend from court, Sir Henry Goodyear, begging for news. I would have written to Elizabeth, but do not know where to send a letter. I take out her many letters to me and re-read her joy at her babies, her excitement at moving to Prague, her confession how she had offended her new subjects by misunderstanding their early gifts.

. . . So I made certain to display the gift of a cradle for the coming babe on the dais in the great hall, as if it were a holy icon. I believe that the people were puzzled by this strange English custom, but pleased . . .

She had always trusted me with her indiscretions as well as her joys. I press the letter to my forehead.

If she were dead or captive, Edward would have told me. Therefore, she must still be alive and free.

As the early winter darkness closes in, to get through the time, I try to write verse as I had once done so easily at court.

Remembering the good-natured, bibulous, literary competitions, I attempt to write an ode in the style of Horace – a challenge we had often set ourselves after dinner, made arrogant by wine and youth. But my metres now trudge heavy-footed where the Roman poet’s had danced and skimmed like swallows.

No thoughts or words seem important enough to distract me. All my being waits trembling on the surface of life. It should be anguish, but I confess that, even while tearing up my attempt at Latin verse, I feel alive once again.

Above all, I need more news. Even without the distortion of malice, accounts of past or distant events are always slippery. The truth often proves to be, insofar as one can determine it, a little less vibrant than the tale as told. The tale is almost always simpler. The true narrative most often proceeds by bumps and hiccoughs, not in great sweeps.

I need a letter from Elizabeth. She has clung to England by writing letters, first from her husband’s German Palatine, more recently from Bohemia. I know she will write to me as soon as she can.

Goodyear writes back by return of messenger. He has heard that Elizabeth and her children struggled down the mountain to spend the first night in Prague, in the house of a Czech merchant near the Old Town Square across the Vltava river from the palace. There, she waited while Frederick and his generals argued whether to try to defend Prague. With Hapsburg soldiers already looting the Hradcany Palace, the cavalcade of carriages and carts left the city by the West Gate just after nine o’clock the following morning.

There seems to have been wide-spread panic, he writes. The royal family were deserting Prague! Frederick was forced to make a speech to reassure the terrified mob that the Bohemian officials, who were in truth escaping with them, would escort the royal family only a short distance then return to defend the city. The heaviest snow caught them on the Silesian border.

The world has changed. And I see a part for myself in this new world. Not at Moor Park.

Her first letter reaches me at last, from Nimberge.

My Dear Bedford (Elizabeth writes), I have no doubt that you have heard of the misfortune that has come upon us and that you will have been very sorry. But I console myself with one thing. The war is not yet over. Frederick has gone into Moravia in search of reinforcements. I will await him in Nimberge. I have also written to my father, the King, begging that he send immediate assistance to the embattled King, my husband . . .

By the time I receive this letter, she has almost certainly moved on. I must track her flight. Find her. Go to her. Elizabeth’s need and mine will meet. Her need will rescue me, just as her mother’s need had rescued me once before.

I can do it again.

But the first ti me I changed my life had been half my lifetime ago. I had been just twenty-two years old and known that I could do anything as well as any man, if I set my mind to it.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_657b6b67-f679-53ca-b0c8-bb4def1ce8a3)

LUCY – EAST ENGLISH COAST, JUNE 1603

My right knee had cramped around the saddle horn. My thoughts jolted with the thud of the horse’s hoofs. The pain in my arse and right thigh was unbearable.

For tuppence, I’d have broken the law, worn a man’s breeches and ridden astride. Then I could at least have stood in the stirrups from time to time to ease the endless pounding on my raw skin.

But I could not break the law. I was the Countess of Bedford. Even if I had not been riding at this mad, mudflinging pace, strewing gold hairpins and silver coins behind me, my progress would have been noted and reported. Therefore, I had to ride side-saddle like a lady and wear a woman’s stiffened, laced bodies and heavy, bulky skirts.

. . . worth the pain . . . worth the pain . . . worth the pain . . . Two days in the saddle so far, one more to go. A man rode ahead of me to confirm food, lodging and the next hired horse. I had never before ridden so far, so fast, nor for so long. Our speed and the effort of keeping my seat at this constant killing pace prevented coherent thought. A woman’s side-saddle is designed for stately progresses and the occasional hunting dash, not for this hard riding.

But a gentlewoman riding full tilt, scantly accompanied, leaping from one post horse to the next, was not invisible. I dared not risk man’s dress lest word of my crime reach the wrong ears and ruin my chance for advancement forever. Meanwhile, my body screamed that I was murdering it.

. . . worth the pain . . . worth the pain . . .

I pointed my thoughts ahead along the green tunnel of the forest track, to Berwick, on the eastern coast just south of the Scottish border, where the new queen of England would arrive the next day on her progress from Edinburgh to London.

Elizabeth, the sour Virgin Queen, was dead. Good riddance to Gloriana! England now had a new king, James Stuart, who was already King of Scotland. This new king brought with him a new queen, Anne of Denmark.

Berwick on Tweed . . . upon Tweed . . . upon Tweed . . . The hired post horse wheezed and panted, throwing his head up and down in effort as his hoofs drummed out the rhythm of my destination.

Sun flashed through the trees. We splashed through pools of white light on the wide dirt track, where I rode at the side to avoid the ruts ploughed by wagon wheels.

. . . a new queen . . . a new queen . . .

Days and miles behind me, other would-be ladies-in-waiting advanced on the royal prey at a more sedate and comfortable pace. Even my mother, as ambitious as I but with an ageing woman’s need for bodily comfort, had fallen behind me. I would be the first to greet our new queen. My best pair of steel-boned bodies, finest green tuft taffeta gown and ropes of pearls jolted behind me in my saddlebags, with my collapsed-drum farthingale lashed across the top like a child’s hoop.

When the new Danish-born Queen Anne had been married to the King of Scotland, Scotland became her country. Now she was moving again willy-nilly with her husband-King to yet another of his strange kingdoms and another strange tongue. Queen or not, she was a mortal woman with mortal fears and must surely be wondering what, and whom, this new foreign country would bring her.

If I had my way, it would bring me. Before any other English woman, I would be the first to make her feel welcome in her new country. I would be the first in her thoughts and in her royal gratitude. The first to receive her favour.

My thoughts drummed in my head with the beat of the horse’s hoofs.

Edward pretended not to know what I did. If he had seen me at this moment, he would have paled like a slab of dead fish and railed yet again against the day he let his aunt Warwick persuade him to marry me, my modest bloodline redeemed only by the size of my dowry. But now that he had spent my money, the Third Earl needed me to succeed in this venture as much as I did myself.

When I had been married at thirteen and become Countess of Bedford, I was not fool enough to hope to love a man so much older, with a noble title, no self-control and an empty purse. But secure in my innocence, youthful confidence and the protecting glow of my dowry, I had never imagined that our chief bond would grow to be rage, at circumstances and each other.

Though I had fought him at the beginning of our marriage, when we still lived at Bedford House in London and were still received at court, my husband’s scorn had burrowed into my head and replaced my childhood nimbleness of mind with a sluggish anger. In the pit of my stomach, I soon began to carry a heavy worm of resentment and guilt.

I could write verse well enough to be admitted, as an equal, to the company of poets, wits and literary men at court, known as the ‘wits, lords and sermoneers’. Among our other games, we competed to write ‘news’ in set rhythms and poetic forms. But my paper and ink were too costly, Edward said, even before his own stupidity had cost us everything. Why did I imagine that I could write like a man?

From the first days of our short time at court, he ridiculed my early gestures of patronage. ‘Why waste money that we don’t have on playing patron to cormorant poets and playwrights?’ he asked. Surely, I must know that they wrote their flattering lies only to earn a free meal at my expense!

And of what use were my languages? We couldn’t afford to entertain anyone, English or otherwise. My closest friend at that time, and fellow poet, Cecilia Bulstrode was no better than a whore. Our former acquaintances of good repute would sneer at our growing poverty. I should concern myself with beds and linens, not the houses that contained them. What other wife created uproar and muddy disorder by building pools and fountains, or wasted money on infant trees when she had not yet produced an infant heir?

Then his actions put a stop to our life at court, to my literary life and to all my hopes of becoming a patron. After his folly, we could no longer afford even to buy my books, nor strings for my lute and my virginal, nor trees for my gardens. No matter how distant and faint, my singing gave him megrims.

Because of his treason against the Old Queen, which might have cost him his stupid head, I was trapped with him in exile from court and all that I loved best. Exiled from the place where I was valued, where my skills and education had purpose and employ. The worm of resentment gnawed. The rich life in my head was going quiet. I was losing myself, spoiling from the core like a pear.

I was already twenty-two years old. The new queen just arrived in Berwick was my chance for escape.

‘Why would she favour you when she has all the nobility of England to choose from?’ my husband had asked when I told him what I meant to do.

I dared not tell him. The avid rumours circulating in London, which had reached me in letters, even in exile from court at our country seat at Chenies in Buckinghamshire, where we then lived. I had heard the same from my dear, faithful friend Henry Goodyear, from the incorrigible gossip Master Chamberlain, and from my friend Cecilia Bulstrode, who collected a terrifying amount of pillow-talk. All three wrote the same vital news. The new queen was said above all else to love drinking, music and dance.

I kissed their letters in a passion of intent. Tenderly, I refolded them, to trap in the folds their promise of escape from Chenies. All my skills that my husband disregarded would serve me at last.

My father had educated me like a boy in the Ancient philosophies and languages, including Greek, Latin and a little Hebrew. I spoke French and could write passable verse in both Latin and English. But I also had been taught the female skills. I sang, danced, played the lute and plucked out not-bad original tunes. I could stitch well enough. Like either sex, I could tipple with the best, having learned young (and to the outrage of my mother) how to drink from court poets, musicians, artists and playwrights.

Even my lowly birth, so disparaged by my husband, would soon be put right. My father, a mere knight, a sweet, gentle man, had just been appointed guardian to the King’s young daughter, the Princess Elizabeth Stuart. A baronetcy was sure to follow soon.

In short, I would make the perfect companion for a lively young foreign queen who loved to drink, dance and sing – if I could get to her before she chose another.

In truth, my husband could not lose in permitting me to ride for Berwick. If I succeeded in my aim, I might restore both our fortunes. If I broke my neck in the attempt, I would set him free to seek a wealthier wife. And if I failed, I would give him the pleasure of punishing me with his disappointment for the rest of my life.

. . . worth the pain . . . worth the pain . . .

A new time had begun for England with the death of the sour Old Queen and the naming of King James VI of Scotland as her heir. A new time had begun for me, Lucy Russell, the young Countess of Bedford. The new king would not hate my husband, like the Old Queen, for having been fool enough to entangle himself in the Essex rebellion against her. If I succeeded, I would entreat the Queen to ask the new king to end our exile from court. He might even forgive my husband the Old Queen’s punishing fine.

But I knew that good fortune is not a reliable gift for the deserving. You have to see where it lies and ride towards it. The future will find you, no matter what you do. Why not take a hand in shaping it?

. . . upon Tweed, upon Tweed . . .

We crested a hill, broke briefly out of the tunnel of trees, plunged down again, taking the downward slope at a reckless speed.

Two sets of hoofs drummed and flung up divots of mud. A single armed groom, Kit Hawkins, rode with me. Like me, he was still young enough to delight in the brutal challenge of our shared journey north.

My knee had set solidly around the saddle horn in a constant blaze of pain. I would scream if I could not straighten it.

Just a little longer . . .

You promised the same an hour ago! shrieked my muscles and bones.

Just another mile, I coaxed, as I had been coaxing myself for most of the day. Then you and the horse can rest . . . for a short time. Less than half a mile now to the next inn . . . a quarter of a mile . . . then a little water for the horse – but not too much. A short rest, no eating for either of us yet or the galloping pace would cramp our bellies as hard as rocks. Then just one more hour of riding, to our arranged stop for the night and the next day’s change of horse.

And then . . . My thoughts escaped from my grip . . . I would dismount, straighten my leg if it would obey . . . lie down . . . sleep for the night on a soft, soft bed. Sleep . . . lying still, flat on my back . . . on tender down pillows . . . quite, quite still. Not moving a single sinew. Heaven could never offer such pure bliss as that.

I felt a jolt, something amiss, too quick for me to grasp. The horse buckled under me. Still flying forward, I detached from the saddle and felt the horse’s neck under my cheek and breast. Sliding.

His poor ears! I thought wildly. I somersaulted over his head.

Don’t step on me!

The world rushed past me, upside down.

Stones!

A crashing thud.

As I emerged from darkness, I found that I could not breathe. I sucked at air that would not come. Searing pain burned under my ribs. Dark mist in my head blurred my sight. My several different parts felt disconnected from each other, like the limbs of a traitor butchered on the scaffold. An ankle somewhere in the dark mist began to throb. Then an arm.

‘Madam!’ said a tiny, distant voice.

The mist cleared a little more. I blinked and moved my eyeballs in their sockets, still trying to breathe in.

A wild accusing eye met mine, only a few inches away. It did not blink.

With a painful whoop, I breathed in at last.

My groom, Kit, stooped beside me. ‘Madam! Are you badly hurt?’

Whoop! I gulped at the air. Then took another wonderful breath. I swivelled my head. My neck, though jarred, was intact. I tested the throbbing leg. Also not broken, so far as I could judge. My left hand felt like a bag of cold water, but my fingers moved. ‘Not fatally . . .’ I sucked at the air again. ‘. . . it seems.’

‘Thanks be to God!’ He offered his hand to help me rise.

In truth, he had to haul me up. I stood unsteadily. My left ankle refused to take my weight. ‘Did you see what happened?’

‘No . . .’ He inhaled. ‘. . . madam.’ He was having as much trouble breathing as I. ‘No hole in the road . . . just stumbled and fell without reason . . . that I saw.’

‘How does he?’ Carefully, I turned my head.

We blew out long shaky breaths.

The hired gelding lay with forelegs crumpled awkwardly under him. Flecks of foam marked the sweaty, walnut-coloured neck. Wind stirred his near-black mane. White bone showed through the skin on his knees. The wild, staring eye still did not blink. The arch of ribs hung motionless. The stirring mane was only the illusion of life. He had not stepped on me, not fallen on me, had saved me but not himself.

We stared down at the long, yellow, chisel teeth in the gaping mouth.

The absolute stillness, where a few moments before had been heat and pounding motion, pricked the back of my neck with incomprehension. I had seen the sudden death of a vital creature before in hunting, more than once. But I could never grasp the sudden nothingness – one moment alive, the next moment a carcass that could never change back.

One of the horse’s ears had been turned inside out in the fall. I pulled off my right riding glove with my teeth, knelt painfully with Kit’s help and straightened the ear with my good hand, as if this act might somehow help undo what had happened. I brushed away a fly already crawling on the horse’s eyelash and looked again at the long, yellow teeth. An old horse. Too old for our pounding pace. I had killed him with my ambitious urgency.

I felt the skin between my shoulder blades quiver, touched by a Divine reproving finger. I laid my hand on the smooth, hard neck, still warm, still damp with sweat. This death was surely a sign. A warning of failure. The skin of my back quivered again.

‘He was too old to keep up such a pace,’ Kit said. ‘Forgive me, I should have seen . . .’

‘Merely old,’ I said to the sky. ‘An old horse, dead from wicked carelessness perhaps, but by natural cause.’

God sent no sign of rage that I was ignoring His sign. Lightning did not split a nearby oak. A hail of toads did not fall.

‘Help me up.’ I stood and tested my ankle again. Still watery, as if the bones had dissolved.

‘I should have . . .’ Kit’s voice shook.

I felt his hand trembling. My thoughts had now cleared enough for me to remember that he would have been blamed had I been killed in the fall. I looked at his white face.

‘Not your fault,’ I said. ‘Mine. And the ostler who hired the horse to me . . . knew that we meant to ride hard. I should have paid more mind to . . .’ I meant to touch his arm in reassurance, but found myself clutching it in a wave of giddiness.

After a moment I patted the arm and let go. I was on my feet. Alive. A clergyman would no doubt call me innocent of wrongdoing, in the case of the horse, at least. But, insofar as I could define a sin, failing a creature in my care was one of them.

However, sin was not the same as a warning. To my knowledge, sin seldom seemed to prevent worldly success.

‘Please take my saddle and bags from the body,’ I said. ‘I’ll ride behind you until we can find me another horse.’

His eyes widened but he obeyed. He also had the grace to pretend not to notice my gasps of pain when he lifted me up behind his saddle.

We made a curious sight, when we rode just before sundown into a modest farmyard, scattering pigs and hens. Faces appeared in windows and doors to stare at a liveried groom with a dirty, dishevelled lady behind him, their horse’s hindquarters lumpy with too many saddlebags, a spare side-saddle and a flattened farthingale.

I paid the farmer far too much to sell me an ancient mare that fitted my saddle. He could not believe his luck. I was overjoyed to find any mount at all.

I did not try to gallop her. I was grateful that she managed to move me forward. In truth, I could not have survived a gallop, even though I had bound my ankle to steady it.

By the time we stopped at our scheduled inn to sup and sleep, much later than intended and long after dark, my left wrist had swollen so that I could not hold the reins in that hand. My head thumped. Preparing for sleep, I found blood smeared on the back of my linen shift, from my raw thighs. Because I could not remove it, I had to sleep in my boot.

The next morning, I could not move. Slowly, cursing, I forced each limb into action. Inch by inch, I pushed myself upright. I had to call for a kitchen maid from the inn to help me dress.

I blinked water from my eyes as Kit carried me into the stable yard and lifted me up into my saddle, now buckled onto the new hired mount. As we set off again at a gallop towards Scotland, when he was behind me and could no longer hear me nor see my face, I wept openly with pain and cursed my rebelling sinews.

The reward had best be worth what it was costing.

I arrived in Berwick at midday the following day.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_53beb112-d0dd-505d-8efa-9045827e73d1)

BERWICK CASTLE, NORTHUMBERLAND, 1603

Queen Anne, my intended prey, stood by a window in the little presence chamber in Berwick Castle, gazing out towards the foggy, darkening sea. I fastened my will onto her like a hound setting at a partridge.

She ignored me and continued to look out into the dusk.

I tottered towards her, past curious courtiers, inhaling sharply with each step and hobbling like a one-legged sailor. At a respectful distance I sank into the deepest curtsy that I could manage.

‘The Countess of Bedford, Your Highness,’ said the gentleman usher, in French.

Let me rise! I begged her silently. This was no time to faint from pain.

She gazed out of the window, still ignoring me.

If she ever let me speak, I could show her that I spoke French. But then, I must have seemed an unlikely companion, with my limp, misshapen hand and pain curdling my wits.

There’s nothing to see out there but fog! Please, let me rise!

Five grooms began to light candles against the sudden fall of darkness. A sconce on the wall threw a sudden wash of unsteady yellow light across the Queen’s face.

I did not like what I saw.

Her tall, lean figure stood half turned away from me, dressed in grey satin, one hand clenched on the pleated lip of her farthingale. The nearest corner of her tight lips was turned down under a long, large nose made larger by the shadow it cast across her mouth.

I could not imagine that shadowed, unsmiling mouth open in song, nor that clenched fist raising a wine glass in a tipsy toast. This new queen was not the lively, deep-drinking, dance-loving, frivolous creature of my friends’ letters. Not for the first time, rumour had been wrong. She might as well have been holding a prayer book and wearing black.

From under my lashes, I tried to read her. My mother had taught me that, to survive, you must learn to read the people who hold power over your life. What you learn will give you power. They think they hide themselves, but the set of shoulder, or twitch of a hand, an uneasy sideways look or overloud voice always gives them away, if you know how to look and listen. Learn what they truly want and give it to them, my mother had said. Then you will not only survive, you will succeed.

More sconces bloomed around the walls. I saw the new queen clearly now.

Another sour queen like the old one, I thought unhappily. To advance in her court, I did not have to like her, but she had to like me.

I had to make her like me. If not, it was back to Chenies with my tail between my legs. Back to Edward and silence. To my lute without strings. To living with my husband’s infinite reasons for saying ‘no’.

I glanced at the three Scots ladies attending her, all soberly dressed, their hair covered. They eyed me coldly. The story of my undignified arrival had quickly spread.

If they were what pleased her, I was finished.

I had nothing to offer this woman except the usual obsequious court flattery that drove me mad with impatience and fuelled a dangerous urge to blurt out the truth. While many of my friends at court before our exile had celebrated my reckless candour as wit, this dour queen would not. Experience had taught me that sour women tended not to like me, however modestly I tried to behave myself. For the first time, it occurred to me that I might fail.

I knew that I made a sorry picture. Both my thighs now trembled violently. I could see the fabric of my gown shake. Though I had paid a castle woman to dress my hair and lace my bodies, my gown was still wrinkled from the saddlebag in spite of all her shaking and brushing. I had managed to cram my injured foot into a shoe, but only after cutting away my riding boot.

My bad ankle trembled on the brink of giving way. My good leg wobbled from having to support my entire weight. Pain brought tears to my eyes.

The Queen turned suddenly, as if she had just noticed me. An unexpected brightness of diamonds and amethysts flashed when she waved a bony hand for me to rise.

‘I thank you, Your Majesty.’ I straightened with care. It was still possible that I might fall at her feet. Then I looked at her face. Our eyes met in shared assessment.

I tried not to stare.

Unlike Old Gloriana, Anne wore no rouge or other artifice. Her naked face looked drained by weariness and older than her twenty-nine years. In the candlelight, her skin was grey against the creamy pearls hanging from her ears. On the jewelled hand she had waved, the nails were bitten short and the skin around the nails nibbled raw.

Forgive me, I thought. I read you wrong.

We studied each other with equal intensity.

Do you not yet understand the need for masks? I ached to ask. Old Gloriana understood that need, most of all for queens.

The weary pain in her eyes tightened my throat. The last emotion I had expected to feel with the new queen was kinship.

I had prepared an amusing, pretty speech of welcome, but could not begin it. Those words were meant to charm a different woman.

I saw now that she had not been ignoring me from spite, nor to assert her position. I recognised the heaviness that had held her unmoving at the window. I knew that long stare into nothing. She had been searching for strength to begin conversation with yet another stranger, who, like all the others, undoubtedly wanted something from her and would require her to make a decision.

I dropped my eyes to her childlike bitten nails again.

Not sour, after all, I thought. Queen or not, she was melancholy and past hiding it. Her youth was being worn away by misery. Like me, she was spoiling from the core.

I felt a rush of gentle ferocity, like the tenderness when I cupped a new chick or saw a fragile green shoot pushed up through clods of dirt and stones.

The Whitehall wolves would tear this poor woman apart. I had felt their teeth and knew how sharp they could be. She must be protected. She must be told. Somehow, without giving offence. But to tell her would give offence, no matter how carefully worded. One does not pity royalty.

‘You made good speed here, Lady Bedford,’ she said. ‘Though perhaps at a dear cost.’ She gestured at my bad hand. So, she had heard the tale too. But between her native Danish accent and her acquired Scottish one, I could not tell what she thought of my journey.

Trying to decide whether to risk speaking my true thoughts or to hazard a jest in return, I stepped onto my bad ankle. A flash of searing pain together with exhaustion betrayed my training.

‘Oww! God’s Balls!’

I staggered, hopped sideways, caught myself and clapped my good hand over my mouth. I heard outraged gasps from the attending ladies, then unbreathing silence. Even the six men-at-arms standing behind the Queen had frozen.

Raw arse and dead horse were for nothing, after all. The touch between my shoulder blades had been a Divine warning. I had ignored it. I would have to slink back to Chenies, confess to Edward . . . for rumour would soon tell him if I did not . . . that I had managed to marry obscenity to blasphemy in two short words. And been thrown out of Berwick for offending the new queen.

The silence grew.

I began to rehearse my long, painful, slow hobbling retreat to the door . . . desperately slow, stretching out my torment . . . the averted eyes of the men-at-arms, the suppressed smiles of the ladies-in-waiting . . . their hungry gossip when out of the Queen’s hearing. I imagined their tutting and lip-smacking disapproval and raising of eyes to Heaven.

I waited to be dismissed.

The Queen was studying me with . . . I tried to resist hope . . . what looked like the first real interest. ‘Lady Bedford,’ she said at last. ‘I think that I must engage you to improve my English. I’m certain my other ladies don’t know so many useful words.’

I imagined a glint of mischief in the swift look she gave her three tight-lipped Scots.

I wagered my future.

I became an angel balanced on a pinhead, precarious yet suddenly sure of my footing at the same time. I must abandon protocol, I was certain. She had had too much protocol. Her carelessness with her person told me that she had put herself beyond the reach of a courtier’s empty flattery. I wagered my future on what I felt she needed most from me.

The words sprang raw and unexamined from my mouth. ‘It will be my greatest pleasure to give you pleasure, madam,’ I said. ‘Pleasure.’ I repeated the word. I let it hang in the air. ‘. . . in English lessons and all else.’

Play, I thought.

‘I will shake my sack of words,’ I said, ‘until every last “zounds” and “zwagger” has tumbled out for your instruction – and enjoyment, if you so choose.’

She gave a minute nod at my return of her serve.

I advanced carefully towards my leap. ‘If my honesty ever oversteps, or I play the fool too far, I beg your forgiveness in advance.’

Her intent stillness gave me courage to go on.

‘Because even my errors will have only one purpose – to give you joy.’ I heard another intake of breath behind me at this presumption.

Joy. The word flew out of my mouth and circled in the air above our heads. A dove. A butterfly. A scarlet autumn leaf.

Joy. My offering to her. Not service, not loyalty, not reverence, nor adoration, nor awe, nor blind obedience, which royalty can always command. Joy. A precious commodity that cannot be commanded of another person, nor bought, nor wrestled into being. It was delicate and fleeting, as I knew very well. You must stalk it, surprise it. It’s a seed that may or may not grow. You can’t force it, but you can dig out the stones, till the ground and stand by with expectant heart and watering cans. Among other things, I was also a gardener. I knew how to make the desert bloom.

The Queen had tilted her head, not looking at me now, listening.

‘Madam, at my birth I was christened Lucy . . . lux, lucis . . . light. In your service, I swear I will earn the right to my name.’ I held her now in my thoughts as gently but firmly as I would trap a moth. ‘If the light and laughter ever fail, you may banish me.’

I heard her draw a deep breath.

Quickly, to lighten my earnest words, I threw open my arms, imitating a player-warrior accepting the fatal sword thrust. ‘And I must beg your forgiveness already, madam. I dare not risk another curtsy or I will sprawl at your feet.’

To my horror, she did not smile at this extravagance. Instead, tears welled in her eyes. I had misjudged and cut too near the quick.

I had made the new queen cry in front of everyone. Now she would hate me. I had dared to pity her and let her know it. Shamed her in public, before those tight-lipped, but almost certainly loose-tongued, women. I had made a second fatal error. Back to Chenies after all.

Then she swallowed. ‘Thank you, Lady Bedford.’

The gowns of the waiting women rustled. There was a tiny pause.

I tried to think what to say, unable to hope that I might somehow, perhaps, survive my own mistakes for a second time.

Then she pointed at my swollen hand. ‘You must have that hand bandaged. I shall ask my doctor to see to it.’ She waved away my renewed attempt to curtsy. She was mistress of herself again.

And she had offered me her own royal doctor.

‘Thank you, madam.’ I dropped my arms. ‘I am honoured . . .’ I caught her eye and noted the slightly raised royal brows and the waiting chilly half-smile. I bit down on the formulaic gratitude.

Lightly, Lucy, lightly now.

She saw me catch myself. Her brows stayed up. But she knew that I had understood her.

I glanced at the row of cold eyes and tight mouths behind her.

She needed a playmate in the pursuit of joy.

‘I will limp gratefully from the field for treatment,’ I said. ‘But before this herald retires injured, she must first deliver urgent news. Two thousand richly jewelled royal gowns await Your Highness in the royal Wardrobe in London.’

‘That’s good news for any woman, royal or not!’

Her Scottish women laughed politely.

Now the Queen was reading me as closely as I had read her. ‘And tell me, Lady Bedford, who brings such good tidings, can you give me more good news? Does it truly rain less in London than in Edinburgh, as I have been told?’ Even through her double-layered accent, I heard a testing playfulness.

‘I could never speak ill of Scotland, Your Highness. Even when the truth demands it.’

She smiled at last. The air around us loosened. We exchanged another assessing look. Together, we had averted danger. We exchanged the most minute of nods. Miraculously, we seemed to stand at the first fragile beginning of friendship. The way ahead felt as tentative as a garden path marked out in sand, but it held the same implied promise that it might be laid, rod by rod, in brick and stone.

In the next days before setting off for London, I tested what gave our new queen pleasure. I soon learned that she did not share my taste for debate and philosophy but did like music and dancing, just as rumour had said. Above all, she needed to laugh.

Therefore, I brought these pleasures together. I taught her – and several of her women – to sing two English songs whilst I played the fool with a borrowed lute and one good hand and made her press her fingers in place of mine onto the strings so that together she and I made a single musician and all of us almost fell off our stools with laughing.

She liked to gossip and would be living among strangers.

Therefore, I improvised scurrilous rhyming couplets to help her, and her Scots ladies, to remember the different English courtiers waiting in London.

‘“Her flattering portrait is like Lady C . . . Only in this – that they both painted be”,’ I recited.

‘Does she still whiten her face with lead?’ Her Majesty clapped a hand to her mouth in mock horror. Her women clucked ‘tut-tut’ and shook their heads. One or two touched their own hair or mouths thoughtfully.

She fancied herself a poet. Therefore, we began together to devise her first masque to celebrate her arrival at the court of Whitehall.

When she grew weary, I made herbal tisanes to help her sleep. I quickly learned not to mention children or the King.

I watched her shoulders loosen. Her eyes began to sparkle. Once, at some trivial jest of mine, she laughed so immoderately that I feared she would veer into uncontrolled tears. Then she patted her breastbone, wiped her eyes and stood up to foot-fumble her way into a half-remembered Danish country-dance, which she promised to teach me when I had two good feet again.

I had ridden north driven by cold ambition and need, in search of advancement. I had won royal favour just as I had intended. I did not expect to have my ambition disarmed by my heart. The more I saw that I was able to please Queen Anne, the more she captured my love. She needed me when no one else did. She needed Lucy in all her brightness. I loved her for her need and shone ever more brightly in the effort to give her joy. It was more than I deserved.

I had ridden into my rightful life where I was needed and where my skills had value. Chenies did not need me as the new queen did. My husband’s other estates at Woburn and Moor Park did not need me. He too would profit from my renewed royal favour. I was saving us both.

I heard the mutters among the disappointed English women who arrived three days after I did. No lady would have done what I did, they said.

But the truth proved them wrong. Three evenings after I had ridden into Berwick, hatless, hair flying, limping and with a wrist like a ham, I was made first lady of the bedchamber to Queen Anne, wife of the new Scottish King, James VI of Scotland who was now also James the First of England. I was elevated to be chief among all the court ladies-in-waiting. If that was not lady enough for anyone, I cannot say what would be.

My new position even silenced my mother when she arrived in Berwick with the other women. This was a woman who, when she later died, was widely said to have gone to see that God remembered to wash behind His ears.

I was twenty-two years old when I rode to Berwick. Power and privilege were in my grasp again. I was happy. I thought I had tamed the future.

This time I don’t know where to point myself. Time is now the enemy. Elizabeth is on the run and may be taken prisoner at any time. She is expecting another babe.

She has not written to me since that first letter.

I must go where powerful men gather intelligence, where news and rumour are born. Someone will know where Elizabeth is. I will ask until I learn. Then I will go to her, on the run or not, however it can be done, and persuade her to come home so that I can help her find joy again as I once helped her mother. She will keep me by her, and I will have a purpose again.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_3965fc76-c0bf-56f0-a952-fc2bde8855d4)

ELIZABETH STUART – BERLIN, DECEMBER 1620

Elizabeth understands the message she holds in her gloved hand. The letter’s language is formal. It twists and turns, slithering around the brutal meaning without ever quite arriving. But the message is clear.

No.

She is being turned away yet again with flattering words that fail to hide the writer’s fear.

No friends here, neither. No room at the inn for the queen and children of a defeated king. They are enemies of the imperial House of Austria who are not known to forgive an affront. The rebellion of the Bohemian Protestants has been an affront. Daring to elect their own Protestant king in place of the Hapsburg Ferdinand has been an affront. Helping the fugitive king and queen will be an affront. The Hapsburgs would not forgive.

With the back of her fur-lined glove, she wipes a clump of falling snow from her left eyelash. Snow is already blotting out the words on the paper she holds.

. . . Madame, in spite of the great . . . in which I hold your esteemed husband . . . and your . . . circumstances alas . . . regret . . . unfit to entertain you in a way suitable to your elevated . . .

Not possible, she thinks. I am the wife of a king, and daughter of the King of England. If these cowards don’t fear my poor Frederick, they must feel some respect for my father and for England! Surely, England would not tolerate such treatment of its First Daughter, even if she were not also Queen of Bohemia.

The letter is from Frederick’s brother-in-law, who regrets his unavoidable absence. Even family lacks the courage to help them.

She should have been prepared for refusal. The Imperial armies are close and marching closer. England is very far away. And, so far, resolutely refusing to take sides.

The messenger stands respectfully, head bowed, awaiting her response. Behind him, at the far end of the snow-covered causeway, stand the closed gates of the city. Behind the gates lie the castle and lighted fires, heated wine, warmed beds. Roasted meats that have not frozen solid. Dry shoes.

Her fingers, even gloved, are almost too cold to hold the Elector of Brandenburg’s message.

With disdain, Elizabeth drops the letter into the snow. She tightens her grip on the belt of the man riding in front of her and re-balances her shivering, pregnant bulk on the back of the saddle. ‘Ride on.’

Captain Ralph Hopton understands the spirit of her order as well as the words. He kicks their horse, turning it so that he forces the messenger to leap back out of their way. One large rear hoof drives the letter deep into the snow.

They have lost carts and carriages to the drifts and to desertion. Looters had not waited until she was out of sight of Prague before beginning to strip the contents of the caravan.

A wave of disbelief rolls back along the line behind her when the remaining drivers and horsemen see that they are turning away from the city. She hears shouts as men heave carts onwards out of ruts in the frozen mud. One by one, the straggling remains of the procession lurches into movement again.

She looks back to see that the light carriages now holding the children and their nurses still follow Hopton’s horse. The first carriage slips on a frozen rut and lurches violently like a ship hit broadside by a wave. Then it rights itself and tilts to the other side. Behind it, straining horses and oxen are lashed by violent English, German and Bohemian curses aimed at the circumstances.

She straightens her aching back and cradles her belly with her free hand. If their eight-month-pregnant queen can carry on, so could the rest of them. Those who remain.

The child in her belly gives a violent kick. Her womb is riding very low, a sign that the birth is not far off.

Not yet, she begs. Please, not until I find refuge! Or else, I may give birth to an icicle. You know you don’t want to be an ice baby.

From here at the front of the line, she cannot see the end of the caravan, but she knows that farther back men and women are still slipping away into a familiar countryside. Back to their mountains, back to their villages. Like Rupert’s nurse.

She imagines the nurse’s husband or lover, perhaps a soldier, pulling her by the arm away from her charge. Saying, ‘This fight is nothing to do with us. Leave the royal brat. Come home!’

The army would not fight for us, she thought. If soldiers desert, why expect more of maids and grooms and ladies of the bedchamber?

She ducks her head under her hood against sudden needles of sleet. If all her new subjects left her, she would manage perfectly well without them.

Without a palace, what need did she have for so many people?

Once past the approach to the city gates, the road divides. Before word of the onward advance has had time to reach the rearmost carts, Hopton asks, ‘Where do we ride, madam?’

‘Custrin,’ she says at once, with authority. Another of Brandenburg’s castles, just as unsuitable, he said. But she is running out of choices. ‘A few days more. Perhaps only two. At Custrin, we’ll have fires and real beds. Tonight we will find a sheltered place to stop and sleep in the carriages.’ Her ears catch the sound of a child crying behind her. ‘We shall curl up together as warmly as a litter of pups.’ She lays a calming hand on the agitation in her belly.

There is still enough charcoal left to keep their braziers alight for another night. The two remaining cooks might even manage hot soup. They will lose a few more animals to exhaustion and the cold, but that can’t be helped. A few more men will slip away to warmer beds.

‘We won’t be able to wash,’ she says cheerfully. ‘But there are worse things than beginning to smell like a dog as well as sleeping like one.’

Chapter 7 (#ulink_879707c7-ca46-518f-8be0-410540e8846a)

LUCY – MOOR PARK, DECEMBER 1620

‘I must go to London,’ I say. We are at dinner in the damp, draughty hall at Moor Park, eating vegetable soup from pewter bowls, the silver plate having long been sold. The long table is half-empty. Though we still keep our personal retinues, they have shrunk. Only three servers stand behind our chairs, where once there would have been one for every diner. Once, musicians would have played while we ate. Once, when we had finished eating, we would have pushed back the table to dance.

The Third Earl sets down his spoon, hugs his injured arm to his chest and looks at me over his barricade. ‘Why?’

At the bottom of the table, our steward holds up a finger to signal the coming point of his story to the four heads leaning towards him, including that of my chief lady, Lady Agnes Hooper, the widow of a local knight. I have no patience with the strict Protestant protocol in which I had been raised, and keep an informal house.

‘To mend our fortunes,’ I say quietly.

The steward’s listeners laugh, settle back on their stools and resume eating.

I am tempted to add, ‘as I did before’. But my husband’s agreement would make my project easier and a great deal more pleasant.

I chase a cube of turnip around my bowl, braced for the frown and pursed lips that always precede refusal.

Even before his accident, Edward had preferred to say ‘no’. ‘Yes’ pained him. It suggested action, feeling, thought.

‘I believe that the muscles of your cheeks and lips will creak if you say “yes”,’ I had once observed.

‘No’ lets him purse his lips. ‘Yes’ hints at a smile. Whenever he is forced into agreement, his mouth stiffens with reluctance, as if it hurts him to stretch it wide enough to let ‘yes’ escape.

The dislike I see in his eyes still startles me. Eyes that are too close together, huddled near his nose.

‘London?’ he echoes, puzzled and querulous like the old man he is rushing to become.

I would have preferred him to shout.

My tongue speaks of its own will. ‘You remember London, do you not? A city to the south of us, on the Thames? Less than a day’s ride . . .’

He flinches. I have used a wrong word again. ‘Ride.’ He had been thrown from his horse, against a tree, while hunting. He could no longer tolerate the word ‘ride’. Even ‘horse’ makes him uneasy.

Why could I play the courtier with everyone but my husband? Close your ears. Keep your eye on your destination, I tell myself.

‘I forbid you to go,’ he says. ‘This is another of your fancies. And certain to cost us dear, like all the rest.’ He bends to his bowl again.

Eyes around the table suddenly grow intent on soup and the roasted duck from our ponds.

That was not a request, I think. I was telling you what I mean to do.

I have had many such silent conversations with him. The smell of the soup sickens me. I set down my spoon. I fold my napkin exactly on its creases and lay it on the table – once we could have afforded a waiting groom to take it from me. I stand up. ‘I pray you all, excuse me.’

Stool and bench legs scrape on the stone floor as the others rise with me. Everyone but my husband.

‘Sit down!’ He speaks as if to one of his dogs. Even whores are granted the courtesy of ‘mistress’, and I am a countess.

‘Sir, I need air.’

‘Sit!’ he snaps again.