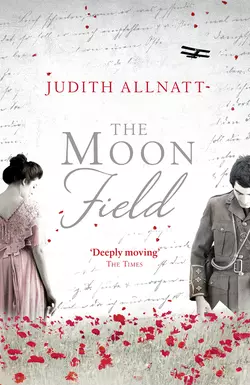

The Moon Field

Judith Allnatt

A poignant story of love and redemption, The Moon Field explores the loss of innocence through a war that destroys everything except the bonds of human hearts.No man’s land is a place in the heart: pitted, cratered and empty as the moon…Hidden in a soldier’s tin box are a painting, a pocket watch, and a dance card – keepsakes of three lives.It is 1914. George Farrell cycles through the tranquil Cumberland fells to deliver a letter, unaware that it will change his life. George has fallen for the rich and beautiful daughter at the Manor House, Miss Violet, but when she lets slip the contents of the letter George is heartbroken to find that she is already promised to another man. George escapes his heartbreak by joining the patriotic rush to war, but his past is not so easily avoided. His rite of passage into adulthood leaves him believing that no woman will be able to love the man he has become.

THE

MOON FIELD

JUDITH ALLNATT

In memory of my mother,

Isabel Gillard,

with love and admiration.

No man’s land is a place in the heart: pitted, cratered and empty as the moon.

Contents

Cover (#u52fb0914-fa1d-5543-bfc5-f41025280380)

Title Page (#u1770b81c-6323-547a-bacb-96e5ee38b838)

Dedication (#u34d23ff9-9265-56de-a550-09a625156fe2)

Epigraph (#ude953101-8de4-5cca-9785-936cec22668c)

Maps (#ud874775e-5913-59d9-9d73-7cc93cf6b8ae)

Prologue (#uba8ed27e-aeab-54e6-8e04-bfbb41060823)

Part One: First Post (#u1168d00a-8647-5b75-a27d-44100c0ca1e7)

1. Watercolour (#u859b01ad-2aa0-50c0-b432-cf1cf351f955)

2. At the Twa Dogs (#u2f671a1d-f2f2-539e-b24d-b0f6b7815caa)

3. Dance Card (#u704c9816-bc78-59de-9135-d66c0140bd92)

4. Measuring Up (#u00aa5805-e829-540a-8182-1fc4db7c5849)

5. Friar’s Crag (#u9f095b71-ce3c-5b1c-aea3-a726be61d117)

6. Feathers on the Stream (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Blue Envelope (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: Flanders, Autumn 1914 (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Polders (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Studio Portrait (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Home Comforts (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Playing Cards (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Earth (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Ruined House (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Blighty (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Christmas Post (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Tin (#litres_trial_promo)

16. 26 Leonard Street (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Breaking (#litres_trial_promo)

18. The Alhambra (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Cat Bells (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Paste Brooch (#litres_trial_promo)

21. The Walled Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Castlerigg (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Stones (#litres_trial_promo)

24. No Man’s Land (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Walking Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

A Q&A with Judith Allnatt (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Judith Allnatt (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_2a427c2b-339e-59cf-b287-dc788cd77d4f)

The lid of the tin box is tight; you have to move from one corner to another, prising and pushing with your thumbs. Green paint peels from its edges as though time has been gnawing at it. Brown patches of rust have pockmarked its surface, but you can still make out the picture: a man and a woman in a rowing boat, oars shipped, he with a fishing rod, she with a red parasol, the gentle slopes of tree-lined banks, the river calm, sun-dappled. ‘Jacob and Co’s “Water” Biscuits’ reads the legend, as if the biscuits were meant only to be enjoyed when boating, conjuring lazy, sun-filled days suspended in the lap of the water, with time to drift, to float …

The lid comes loose with a faint gasp of released air. Inside are papers and objects, loosely packed. There is a bundle of letters, the expensive blue writing paper tied, oddly, with a bootlace. A pack of Lloyd’s cigarettes has a faint smell of tobacco and an even fainter trace of roses. There are photographs: stiffly posed family portraits of men and women in high collars; a girl playing tennis, one hand bundling the encumbrance of her long skirts aside as she reaches for her shot; hand-tinted postcards of lakeside views.

The heavier objects have found their way to the bottom: an amber heart, a pocket watch, a set of keys, and an ivory dance-card holder with a tiny ebony pencil. Lifted, each one fits your hand, makes a hieroglyph: the shape of the past against your palm. This was real; I was there, they say as you feel their weight and smoothness.

Beneath them, lining the tin, is the stiff paper of a watercolour painting, slightly foxed and with its edges curling a little but still with its landscape greens and blues, the texture of the paper showing through the brushstrokes of some unknown hand.

PART ONE (#ulink_f43b15af-e26e-5b3d-abd5-92e88521e8ce)

1 (#ulink_52521034-d97f-578d-ac81-dedecb6a4f8b)

WATERCOLOUR (#ulink_52521034-d97f-578d-ac81-dedecb6a4f8b)

Today would be the day. George touched the bulky package in the breast pocket of his postman’s uniform as if to check, one more time, that it was there. His best watercolour was pressed between the pages of his sketchbook to keep it flat and pristine, as a gift should be. He felt his heart beating against the board back of the book. All morning it had been beating out the seconds, the minutes and the hours between his decision and the act. Today, when he went on the last leg of his rounds, he would present Violet with the painting over which he had laboured. ‘As a token of my esteem,’ he would say, for, even to himself, he dared not use the word love.

In the sorting room at the back of the post office, he greeted the others, hung his empty bag on its hooks at the sorting table so that it sagged open, ready to be filled, and leant against the wall to take a few moments’ rest. The late-morning sun slanted down through the high windows, alive with paper dust that rose from the table: a vast horse-trough affair with shuttered sides. Kitty and her mother, Mrs Ashwell, their sleeves rolled up, picked at the choppy waves of letters, their pale arms and poised fingers moving as precisely as swans dipping to feed. Every handful of mail, white, cream and bill-brown, was shuffled quickly into the pigeonholes that covered the rear wall, each neatly labelled street by street.

‘I see Mrs Verney’s Christopher has a birthday,’ Kitty said as she pressed a handful of envelopes into ‘20–50 Helvellyn Street’.

‘He’s reached his majority,’ Mrs Ashwell said. ‘Let’s hope he’s soon home to enjoy it.’

Mr Ashwell, the postmaster, came in carrying a sack of mail over his shoulder. He nudged George and thrust the sack into his arms. ‘Dreaming again, George?’ he said. ‘You left this one by the counter right where I could trip over it.’

‘Sorry, sir,’ George said quickly.

Mr Ashwell made some show of dusting off his front and pulling his waistcoat down straight. ‘Concentration, young man,’ he said, giving George one of his straight looks. ‘Concentration is needed to make sure that work proceeds in an orderly manner.’ He stroked his moustache with his finger and thumb while continuing to fix George with his gaze. George felt his cheeks begin to burn.

Mr Ashwell said, without looking at his wife, ‘Very busy on the counter today, Mabel. Tea would be most acceptable. Arthur’s assistance sorely missed.’

Mrs Ashwell’s hands stilled amongst the letters and her back stiffened as if to brace herself against the thought of her son, so far from home. Through the doorway between the sorting room and the shop, she could see Arthur’s old position at the counter. The absence of his broad back and shoulders, of the familiar fold of skin over his tight collar and the neatly cut rectangle of brown hair at his neck struck her anew each time she let her glance stray that way. It was as though someone had punched out an Arthur-shaped piece of her existence and pasted in its place a set of scales and a view of the open post office door and the cobbled street beyond.

Sometimes, when the post office was closed and Mr Ashwell busy elsewhere, she would stand in Arthur’s old place and rest her elbows where his had rested. She would bow her head and finger through the set of rubber stamps as if they were rosary beads. At these moments, she tried not to look at the noticeboard on the side wall. Amongst the public notices of opening hours and postal rates was the sign that her husband had insisted be displayed, just as all official documents that were sent from head office must be. An innocuous buff-coloured sheet of paper that one might easily overlook, thinking it yet another piece of dull information, it read:

POST OFFICE RIFLES –

The postmaster’s permission to join must be sought.

Pay is equal to civil pay for all Established Officers plus Free Kit, Rations and Quarters.

GOD SAVE THE KING.

The detailed terms and conditions followed in smaller print below.

Mrs Ashwell thought about the boredom of the counter job on a quiet afternoon, of how Arthur’s eyes must have run over and over all the notices: ‘Foreign packages must be passed to the counter clerk.’ ‘Release is for one year’s service.’ ‘This office is closed on Sundays and official holidays.’ ‘Remuneration will be at an enhanced rate.’ She imagined the phrases repeating in his mind as he tinkered with the scales, idly building pyramids of brass weights on the pan.

‘Tea,’ she said, under her breath. Then more determinedly: ‘Tea,’ and went upstairs to their living quarters to make it.

George hefted the sack up on to the table and upended it, spilling a new landslide of mail that re-covered the chinks of oak board that had begun to show through.

‘Is that the last bag?’ Kitty asked of her father’s retreating back.

‘Better ask George if he’s left any more lying about,’ he said and closed the door behind him.

Kitty rolled her eyes at George. ‘He’s been like a bear with a sore head ever since breakfast. We got Arthur’s first letter,’ she added.

George came round to her side of the table and they sorted side by side, their heads bent companionably together, George’s fair hair ruffled where he had run his hands through it in the heat, Kitty’s springy, pale brown hair tied back neatly out of the way. George waited for her to elaborate about Arthur but Kitty bent her head to her work and pressed her lips together. After a while, when the job was almost done, George said in his slow, gentle way, ‘It must be a terrible worry for your father.’

Kitty snorted. ‘Quite to the contrary; Arthur is travelling further afield than Penrith and preparing to tackle the enemy, whereas Father is still chained to the counter like a piece of pencil on a string.’

‘Aah,’ said George, pausing to look at her more closely. ‘And how about you, Kitty? How are you bearing up?’

‘I miss him, but it makes me sad to see Mother miss him even more and it makes me cross that Father won’t let the subject rest.’ She tapped the letters in her hand smartly on their side to line them up, shoved them roughly into a pigeonhole and then, seeing her mistake, pulled them back out again.

George laid his hand on her shoulder. ‘Oh, Kit,’ he said. ‘I’m so sorry.’

She gave him a half-hearted smile. ‘Never mind. What was it we used to say at school on bad days?’

‘All manner of things shall be well,’ George said slowly.

‘Exactly.’ She looked again at the address on top of her pile of mail and placed it carefully into the correct wooden cubby-hole. ‘Here, give us your bag,’ she said. ‘I’ll fill it up.’

He held the bag open while she put in the packages of post to be delivered to the villages; then she parcelled up each street with string and dropped them in on top. She helped him on with the bag, reaching up to lift the strap over his shoulder and then settling the weight at his back.

‘Sorry it’s a heavy one,’ she said.

‘It’s cutting down the number of deliveries that’s done it. Bound to be heavy.’

She buckled the bag and gave it a pat. ‘See you later,’ she said. ‘We’ve got plum bread for tea. I’ll save you some.’

George nodded and went out through the post office, past the dour looks of Mr Ashwell and a queue of chattering customers and into the brightness of the day. The market place seemed just as busy as usual; almost impossible to believe that the country was at war: shoppers were choosing vegetables, lengths of cloth and ironmongery from the carts lined up in rows in the centre of the square, each cart tipped forward to rest on its shafts, the better to show the goods. The calls of the vendors mixed with the barking of dogs and the rumble of a motor charabanc passing along St John’s Street. The sky was a hazy white and the green flanks of the hills rose in the distance behind the tower of the Moot Hall, their lines as familiar to him as the lineaments of his own face. Taking a deep breath to clear his lungs of the indoor smell of the post office, he caught the musky odour of horse dung and the sharper tang of motor oil. He paused to adjust the strap of the postbag and loosen his tie a little; then he turned down the alley at the side of the post office to collect his bike. He wheeled it out, leaning its saddle against his thigh, and went on in this fashion, bumping over the cobbles, past the Moot Hall and into the narrow streets beyond.

The bike was a heavy, black, iron thing with a basket the size of a lobster pot and when George first got it, he’d not been able to manage it on the steep inclines. He’d needed to get off halfway up a hill and walk it up the rest, sweat darkening his fair hair and sticking it to his forehead. He had persevered though, pedalling a little further each time, thinking of his body as an engine that would benefit from work, and taking pleasure in the healthy ache of his muscles at the end of a day. His uniform jacket had needed to be let out along the back seam to allow for the growing breadth of his shoulders, and his mother, fitting the jacket on him, had called him an ‘ox of a man’ and made him smile. Now, by standing up on the pedals he could force the bike uphill, clanking and complaining, his solid frame bent over the handlebars, shoulders hunched and front wheel wobbling as he slowed for the steepest slopes. Having the bike meant that he could deliver to the farms and hamlets. His spirits lifted as soon as he got out among the fells and he happily left the younger boys to divide the rest of the town between them and deliver on foot carrying lightly loaded bags and returning more frequently to the office to refill them.

George forced himself to walk at his usual pace along the street and up and down the steps of the guesthouses. There was no point hurrying, he told himself sternly, because if he arrived at the Manor House early she would still be lunching and he would have to deliver the family’s letters to the gatehouse, and would miss his chance again. No, he had to do everything as usual and must not leave the town until the Moot Hall clock struck one. That would bring him to the grounds around two o’clock, just as she set out down the lane from the house to take her walk but before she turned off right for the fell or left for the fields and the river.

It had been at the bridge that he had first seen her. He had almost not noticed her in the dappled shadows of the alders that grew beside the river, right close against the stonework of the bridge; only the brightness of her white blouse had given her away, she was so still. She was holding a brown box in both hands and leaning against the parapet. George was struck by the way her straight brown hair was caught in a twist that sat neatly at the nape of her neck and how her posture, leaning forward to focus intently on something below, accentuated the slenderness of her waist. He slowed the bike, thinking to pass on the far side of the narrow bridge without disturbing her but the crackle of the wheels over the grit caught her ear and she turned, her hands still holding the object in front of her and looked at him as if puzzled for a moment. Her face … pale, with dark eyes, forehead slightly drawn, as if coming round from sleep, high cheekbones and full lips, which ran into upward indentations at the corners suggesting the tantalising possibility of a smile that was at odds with the serious expression of her eyes. Without even thinking, he put one foot down on the ground and stopped dead.

‘What are you doing?’ he said, blurting it out into the moment before she could turn away.

‘Preparing to take a photograph,’ she said.

He got off the bike and wheeled it over to her. His family had only one photograph, a studio portrait of his parents: his mother seated, wearing her bridal gown, veil and circlet of flowers; his father standing stiffly behind her, one hand resting on her shoulder.

She said, ‘I want to catch the way the light is reflecting off the water on to the rock,’ and pointed at the boulders that were tumbled midstream, the current divided by them into shining cords that glittered and threw up shifting patterns on their undersides.

He nodded and they stood together watching the movement and listening to the rush and trickle of the water over the bed of smaller stones.

‘Can you see a pattern in it?’ she asked.

‘Nearly …’ he said, for it seemed that there was a pattern though it was complex and hidden just beyond his ability to grasp it.

She turned to him. ‘You’re right,’ she said. ‘A nearly pattern. It’s just a little too quick for us to follow.’

She held the camera up again and looked down through the viewfinder. She sighed and passed it to him, saying, ‘What do you think? It’ll be impossible to catch the sense of motion, of course.’

The viewfinder had a greyish tint and George looked through it at a scene transformed in an instant to cooler tones. Gnats showed like grey dots above the surface of the water, their dancing as complex as the lights on the rocks beside them. Without the glare, the shifting lights were softer. He could see, on the shady side of the stones, dark bars beneath the water.

‘There are trout,’ he said, ‘lying up out of the heat.’

‘Are there? Where?’ She peered over the parapet at where he pointed. ‘Are you an angler?’ she asked.

George shrugged. ‘I fish a bit. Mostly I just look a lot and so I see things.’

She gave a little smile and he blushed as if he had said something stupid. He gave the camera back to her. ‘Will it be in colour? The picture?’ he asked, making an effort to conquer his shyness.

She nodded. ‘The new film still isn’t as close to a natural palette as one would like; it’s better than monochrome though.’

‘Except for in the snow,’ George said.

That smile again. George’s heart turned over. ‘I prefer painting,’ he blurted out; then, fearing he’d been rude: ‘I mean you can get the real colours then, all of them. I like going up on the fells in the evenings when there are greys and purples and the rust of the bracken, not just green, the slopes aren’t ever just green …’

She looked at him then. Not as if he was being dull, as his little brother, Ted did, or as if he was unhinged as Arthur had once when he spoke to him about painting, but as if she was really, truly listening. She said, ‘… and clouds aren’t ever only white any more than the water’s ever only blue. Do you go down to Derwentwater to paint?’

‘Sometimes,’ George said, ‘and out on the tops: Cat Bells, Helvellyn. But I haven’t always got paints; sometimes I sketch. It’s expensive, you know.’

‘I don’t always take the camera,’ she said, ‘sometimes I just sketch too.’ She held out her hand. ‘Violet Walter. I live back there.’ She pointed towards the trees, beyond which, George knew, lay only one house, the Manor House with its grey roofs and many chimneys, impressive even against the rising ranks of evergreens that finished like a tideline halfway up the huge bulk of Ullock Pike, which over-towered all.

‘George Farrell,’ he said, taking her pale, perfectly smooth hand in his, then letting it go quickly in fear that she would think him too familiar. ‘P-P …’ he stuttered over the word ‘postman’.

‘Painter,’ she said and smiled.

That had been in May. The first month he had looked for her often but his searching had been in vain because he had later learnt that she had been away. She told him that she had been staying with Elizabeth Lyne, an old school friend in Carlisle: describing another world of tea taken on the lawn, with white cloths under spreading elms, and dancing after twilight, music spilling like magic from the open throat of the gramophone.

He had kept looking and had eventually been rewarded. Sometimes he just glimpsed a distant figure on the hillside as he passed with his bike and bag along the road below; then she would raise her hand to him and he to her, in salutation. Sometimes she would be coming towards him from home with her camera in its leather box slung across her shoulder and he would give her the letters for the house. Almost every day, in among a sheaf of bills in brown envelopes, there would be one creamy envelope for her with a Carlisle postmark. She would shuffle through the letters until she saw it and then stow it in one pocket and put the rest in the other. He imagined that she must miss her friend badly and feel the isolation of the spot after her companionable stay in the town.

When he had passed over the letters, he would turn around so that he could walk with her a while. He would wheel the bike alongside; her camera stowed with the post in the basket so that she might have a hand free to hold her long skirt clear of the dusty road. If she had letters of her own to send, in the pale blue envelopes she favoured, they would walk first to the postbox before strolling on, out into the countryside. Sometimes, the best times, when he climbed a track to one of the lonely hill farms, he would come across her leaning on a gate looking out over the valley and he would join her to share the view. They talked of the way the clouds chased the light over the hills, and of the hawks nesting in the copse near the house, which hovered, dark specks in the heavens, giving perspective and making the piled clouds mountainous.

George learnt that she was older than he was by three years. ‘An old lady of twenty-one,’ she said. An only child, she had been educated at a boarding school in Carlisle, then a finishing school in France. She spoke of its beauty: the French countryside softer than Cumberland with hedges rather than walls, low slopes and wide plains of rich pasture and standing crops. She described the rocky coast of Brittany, its crashing waves and spume-filled air, and a Normandy beach with a wide arc of sand, which she had walked from end to end, slipping away from her school party to watch the gannets dive like black arrows into the sea. Her eyes lit up as she told him of such things and she motioned with her hands to trace the sweep of the bay or the birds’ headlong plunge. Once he told her that looking out over the lake from the top of the fells was what made him certain that he had a soul, and she had touched his arm and said, ‘Yes, yes.’

He had told her how it had been at his school. How he was different, always in trouble when the master asked him a question and he was unable to answer because he had been staring out of the window at the clouds, making dragons and faces and genies from their ever-changing shapes. He had said less and less the more he grew afraid that he would get it wrong, until the other children called him ‘moony’ and ‘idiot’ and ‘simple’.

‘You’re far from simple, George,’ she said. ‘They mistook the distraction that comes from hard thought for no thought at all, and that’s their error.’ She touched his sleeve again and he thought his heart would burst with pride because although Kitty and his mother had always said such things this was different.

When she spoke of her parents, she always had a note of worry in her voice. Her father was often abroad attending to his business interests, leaving the land and Home Farm to the estate manager, and her mother to her own resources. Mrs Walter, too much alone, suffered ‘sick-headaches’ and fatigue and often withdrew to her room. Violet once let slip that her father, even when back in London, frequently stayed at his club and George wondered what had caused the breach between her parents, but asked no further, guessing at the hurt that a daughter would feel to know that she was not enough to tempt a father home.

From her room, Mrs Walter instructed the housekeeper, Mrs Burbidge, and took her lunch on a tray. Afterwards she wrote letters, but later in the afternoon, she required Violet’s company, wanting her to sit with her and talk or read aloud. As the sun grew hotter in the afternoon, George would notice Violet glancing back at the copse within which the house was hidden or at her silver wristwatch. He would rack his brain for a question. ‘What was the town like, where your school was? What did you sketch on your picnics?’ Anything to stop her saying the words he dreaded: ‘I must go.’

George rattled the latch of a garden gate and then stood stock-still to listen, in case he had missed the Moot Hall bell. He heard nothing but nonetheless quickened his pace, the bike wheels juddering as he turned into Leonard Street where he lived. As he bumped the bike to a stop outside the house, his mother came to the door to meet him carrying a package wrapped in paper and with Lillie hanging on to her apron and sucking her thumb.

‘I thought I heard you; you made such a clatter,’ his mother said. ‘Have you got a bit behind?’ She passed him the package of sandwiches and a billycan of cold tea.

‘Carry!’ Lillie said and let go of the apron to lift her arms up to him.

‘You mustn’t get behind, George. Mr Ashwell’s a tartar for punctuality.’

‘Carry!’ Lillie said again, imperiously, and George put the food down on the step and lifted her under the armpits: a bundle of warm body and petticoats. He put her on his shoulders where she grabbed on to handfuls of his hair.

‘Ow! Lillie!’ he said and loosened her fingers, laying them flat against his head.

‘Horsy! Horsy!’ Lillie said and George held on tight to her skinny knees and jogged obligingly up and down the street.

The sound of the Moot Hall bell reached him, a single sonorous note, and he lifted Lillie down, detaching her fingers from his ear as he did so, and handed her into his mother’s arms.

‘You’d better cut along,’ she said. ‘You’d think it was a holy calling the way Mr A. goes on about duty and professionalism and “the mail must get through in all weathers …”.’ But George was already on his way, billycan rattling from the handlebars and the corner of the sandwich packet clamped between his teeth as he ran with the bike to the end of the road, threw his leg over the saddle and freewheeled down Wordsworth Street.

He pedalled along the road towards the park and left the buildings behind him, out into the elation of open space and over the bridge where the river flowed shallow and glittering and ducks and moorhens pecked at the trailing green weed. He passed the bowling greens where men in whites and straw hats were playing a tournament, while the ladies and elderly gentlemen watched from the benches, and then he took the back paths through the exotic trees, keeping out of sight of the park keeper, who would curse at him and make him get off his bike and walk. Then he was out on Brundholme Road with open fields either side, the sun hot on his back, soaking through his dark uniform jacket like warm water, the material prickling through his shirt.

By the time he had delivered the mail to the village post offices and to the scatter of farms beyond, he was starting to worry that he would arrive too late and took the last farm track down from the hill at a rate that rattled his teeth. A mile or so further on along the main road to Carlisle he reached the familiar gatehouse and turned in to the drive through the wood, his way lined by the dark glossy leaves of rhododendrons and the straight boles of Scots pines. Here and there, copper beeches made a splash of colour against the massive bulk of Dodd Fell that rose up behind, cluttered with rocks and strewn with sheep: small, pale dots on its upper slopes.

As he rounded the bend to face directly into the sun, he was dazzled momentarily; he put his hand up to his brow and squinted. A familiar figure, carrying a brown leather box, was making leisurely progress along the drive towards him. His pulse quickened. He felt a sensation run through him like a current through a wire making his grip on the handlebars tighten and his sense of the board back of his sketchbook in his pocket keener, as if it had imprinted itself on his skin. He forced himself to slow, to sit down on the saddle, to rehearse his speech in his head. He would greet her as usual, turn the bike around as usual, give her the post for the house and then, just casually, as if it were something extra he’d just remembered, take out his sketchbook, slip out the painting and say to her, ‘This is for you, as a small token of my esteem.’ She would thank him in her solemn voice to show that she took his gift seriously, and would look at it and exclaim to see that it was her favourite view – from Dodd Wood, out over the lake – and perhaps admire the workmanship. Here his stomach made a strange kind of tumble, as if he had swung so high in a swing that he thought he might fly right over the top of the bar. Perhaps she would put it carefully into her camera case and say she would treasure it … The bike jounced into a rut that nearly unseated him. He swerved and squeezed on the brakes; then he took a deep breath and got off the bike, just as she raised her free arm and waved: a wide, expansive gesture that made his heart lift. He forced himself to walk slowly towards her, concentrating on the soft shushing that the tyres made on the drive.

‘Hello there, I don’t suppose you have anything for me?’ she said with a smile as he reached her and swept the bike round in a circle to walk back with her the way he had come.

He handed her the sheaf of letters that he had saved until last. Straightaway she picked out the cream envelope and tucked the rest into her pocket. She felt the letter between her thumb and forefinger and frowned as if surprised by its thinness. She turned it over as if she were about to open it, but then turned it back and started to walk alongside him.

He glanced sideways at her but she didn’t turn to look at him and the words he had planned to say deserted him. ‘Do you have anything to send?’ he asked instead. She shook her head. ‘Nothing from the house today, and I … I’m not sure. Perhaps I should read this one first.’

‘Where are you planning to walk today?’ he asked. ‘It’s very hot once you’re out in the sun, you might find it tiring.’

‘I thought I’d go up through Dodd Wood. I can take advantage of the sun and get a view of it brightening the lake without getting overheated.’

George nodded, pleased that he could go with her for most of the way as Dodd Wood was on his route back. ‘I know a good spot where you can see the different colour of the shallows and the deeper water,’ he began, thinking to turn the conversation to lake views in general and from there to painting them and then to one painting in particular, but the thought was enough to cause him to break into a deep blush and he found himself suddenly rushing to jump ahead, ‘In fact I’ve brought something, as a token—’

‘I’m sorry, George,’ she said, fingering the letter. ‘Forgive me, but I feel that I can’t wait; I must open this. Would you mind?’

George shook his head dumbly; a sense of misgiving filled him and he knew that he would not now take out the sketchbook from his pocket; that, indeed, he felt afraid that its angular lines must show through the material, its bulky shape exposed, as if he carried his feelings like a foolish badge for all to see.

Violet took a few quick steps and then stopped; he drew to a halt a little behind her. She slit the envelope with her thumb, pulled out a single sheet of paper and bent over it, quickly scanning the page. Her hand dropped to her side.

She turned to him. ‘It’s Edmund,’ she said. ‘He’s being sent away for more training, then he’ll be posted abroad.’

‘Edmund?’ he said.

‘Edmund Lyne, Elizabeth’s brother.’ She looked at him as though he were being obtuse. ‘We were going to be engaged,’ she said flatly. ‘I was hoping to see him again when he got leave, to have one more visit to Carlisle before … before …’ She looked away, into the trees, unable to trust herself to speak.

‘I see,’ George said as he began to understand. What a fool, he thought, to have imagined all those letters were exchanges between school friends: gossip and girlish confidences. Of course – they were love letters; of course they were. The phrase ‘a token of my esteem’ floated through his mind as though his brain was working minutes behind and had finally located the words he had so carefully chosen. An engagement! He swallowed hard; he mustn’t let her even glimpse his feelings. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said; then, taking a deep breath: ‘Is there anything I can do?’

She didn’t answer but refolded the letter and then folded it again into a thin slip. Slowly, she returned it to its envelope and carried on folding, turning the letter into a small rectangle that fitted into her closed hand. ‘He writes in haste; they’re to travel to a training camp, and then be sent abroad. That’s all they’re allowed to say. He says he’ll write again.’ She nodded twice and wiped her cheeks with the back of her hand. At last she looked at him and her face was blotchy, her eyes reddened. ‘So silly of me,’ she said. ‘Perhaps I had better go back to the house.’

‘I’ll walk back with you,’ George forced himself to say although he longed to get away so he could be on his own, where no one could see him, where he could think.

‘No need, I’ll be fine,’ she said and took in a huge breath. ‘I’m sorry about all this.’ She half turned but then seemed to remember something. ‘Did you say you had something else for me?’

‘It was nothing, really,’ George said, trying to keep the misery from his voice. She was looking at him more closely now, her brows furrowed in puzzlement.

‘George?’ she said and he could see her expression change to concern as she scanned his face.

‘I told you; it was nothing!’ George said more loudly than he intended, his voice coming out hoarse and strained as he yanked the bike straight and moved past her. ‘George, I didn’t think, I’m so sorry …’ she started.

He could hold on no longer and threw himself at the bike, nearly overbalancing as the postbag swung sideways. He pushed off and stood up on the pedals to gain speed, forcing it along the rutty drive and away from her in a spatter of grit. Gasping for breath, he looked back only once as he reached the bend. She was standing looking after him, silhouetted against the light at the end of the tunnel of trees, her camera slung across her shoulder so that it bulged at her side, her shoulders drooping and her fist still closed over the letter. Then he swung away into the trees that would hide him from view.

2 (#ulink_4736a511-cdd3-5cbe-b65e-17a670dbba63)

AT THE TWA DOGS (#ulink_4736a511-cdd3-5cbe-b65e-17a670dbba63)

When George regained the road after leaving Violet, he wanted to be alone and so he turned the opposite way from home and rode out towards Carlisle. He cursed himself as a fool to have harboured affection in the first place for someone he knew to be so far above his own station, and called himself an idiot not to have guessed that she would have an admirer. He imagined how he must seem in her eyes: a callow boy, not yet a man, a lackey, someone you had to be kind to … Yet, when he thought about her tears, the feelings he had were not boyish: he felt fierce, angry with anyone or anything that could dare to hurt her. He wished, more than anything in the world, that he could wipe the tears away, and that he could comfort her and hold her in his arms. It had been weak to run away! Yet, now that he had run away, now that she must think him a cad, how was he to face her again? The thought of the way they had walked and talked together, the camaraderie they had shared and the feeling that this would never be recaptured weighed upon him; he rode on and on, seeking to blank out emotion with physical sensation, pushing his aching muscles further, seeking relief through sheer fatigue.

He rode and rode until he eventually came to the suburbs of the town, where dirty redbrick terraces crowded straight on to the roads and children dodged unnervingly in and out between the carts and cycles and motors. He turned out of the mêlée and into the haven of a leafy park where he sat on a bench for a considerable time, thinking about Violet and her sweetheart.

After a while he realised that Kitty would be wondering why he hadn’t come back for tea. Three young men were kicking a football around on the lawns and larking about. The light began to wane and he remembered that his mother would be worried, yet he sat on, idly watching them and feeling dispirited.

One of the young men, showing off, kicked the ball high into the beech tree above him, showering him with leaves and breaking his reverie. He listened to them daring each other to get the ball down and watched as they threw sticks, unsuccessfully, until eventually two of them shinned up the tree. There they jumped up and down to shake the branches and urged each other to go higher and further while the third shook his head in disbelief and sat down on the bench next to George. He introduced himself as Ernest Turland, and said to George, ‘One of the bloody fools is going to break his head. Probably Rooke,’ he added. ‘Haycock’s taller and stronger.’ The bigger chap triumphed at last by hanging from the branch where the ball had lodged, his boots appearing alarmingly in mid-air as he swung. The branch creaked ominously but the ball fell with a sound of snapping twigs and rustling leaves just as a park keeper appeared and started to lock up the tennis courts. Catching sight of them, he let out a shout. Turland scooped up the ball and had taken George’s bike by the handlebars before George had even worked out that he would cop it too if he stayed.

‘Come on!’ Turland said and George got on the bike and pushed off, standing on the pedals with Turland perched on the seat with his legs dangling and the ball held tight against his stomach. Behind them, the others clambered down, dropped to the ground and then took off running after them.

‘Go to the Twa Dogs!’ Haycock called out as he swerved between two metal bollards and along a footpath, leaving the bike to take the road.

‘Left! Go left!’ Turland said as they made it to the wrought-iron gates at the edge of the park. George glanced back and saw the park keeper standing with one hand above his eyes peering after them, dazzled by the low sun. He cut left and then followed Haycock, who had re-emerged further along the road, down a series of side roads and back alleys between the terraced houses. When they reached the pub, Turland showed him where to stow the bike behind the privy at the rear and pressed him to come in for a drink. George, carried along on a wave of bonhomie that was new to him, readily agreed. Triumphant after their escape, jostling each other, faces flushed, they all crowded inside.

Turland ordered beers and they squeezed around a table, Rooke pouncing on spare stools and drawing them over. The place was full of men in their working clothes, some sitting at tables, some standing or leaning on the bar and a group playing shove-ha’penny at a board in the corner. The only female was a young woman with a figure that was beyond buxom, who was squeezing between tables to collect up the glasses. She paused beside a swarthy, heavily built man in shirtsleeves and braces who sat alone at a corner table reading a newspaper. George heard him ask for whisky and push some coins over to her without bothering to look up from his paper. She went straight to the bar and returned with a whisky glass, before carrying on stacking spent glasses. A fug of cigarette and pipe smoke hung in the air; the smell of Capstans mixing with the fruity smell of the briar. The whitewashed walls of the room had been turned a glossy brownish-yellow by the smoke. The only decoration in the place was a handful of paper Union Jack flags in a stoneware jar on the bar and a couple of pen-and-ink caricatures in frames, their faded mounts scattered with thrips, trapped behind the glass.

Behind the bar, a balding man with a sour face was pulling pints. He nodded to a younger man who came in briefly to change a barrel and then rolled the empty one out, cursing as it stuck in the doorway and kicking it through.

‘As I said, Ernest Turland, junior reporter.’ Turland offered him a hand wet with slopped beer. ‘And this is Tom Haycock, from the gas works, and Percy Rooke …’

‘… of no fixed employment,’ Rooke cut in.

‘Currently delivery boy and general factotum at the Cumberland News but with an eye to advancement,’ Turland said, punching Rooke lightly on the arm.

George introduced himself as George Farrell and, when pressed about why he had been sitting alone and mournful in a strange town, gave a vague answer about having had a disappointment and quickly asked how they came to be friends.

‘Turland and I were in the scouts together,’ Haycock said, ‘and Rooke lives at Turland’s lodgings.’

‘Under the dragon’s eye,’ Rooke said. ‘She even counts the toast at breakfast.’

‘That’s because she knows you pocket some for your lunch,’ Turland said.

Rooke grinned and shrugged. He took a pack of dog-eared cards from his pocket and shuffled them adeptly, flipping through two piles with his thumbs, cutting and splicing them together and then spreading them out on the table like a fan flicked open and clicked shut again. They decided on pontoon and as they played George took the opportunity to observe his new companions.

Haycock and Turland looked around his own age, eighteen or nineteen, Haycock maybe a little older as he was stocky, wider in the chest and well muscled; he moved with the confidence of a man who works with his hands and knows the strength of his arm. He had fair, crinkly hair that reminded George of the wire wool he used to clean the spokes on his bicycle wheels. Turland, who studied his cards with great seriousness, was a good-looking young man with more delicate features, dark-haired and with brown eyes and an olive complexion that seemed darker than merely the tan of summer. George wondered if there was continental blood in his family.

Rooke, despite his predatory name, reminded George somehow of a mouse: he was so quick in his movements and he was small, surely no more than sixteen, if that, really still just a boy. His hair was slicked to the side, flat to his head, which didn’t flatter him as his ears stuck out rather. His eyebrows seemed always to be raised, giving him a look not so much of surprise as constant alert anxiety, as though he was ready to take off at any minute should something untoward occur.

Rooke had suggested that they play for matches and he soon had a pile of them in front of him, whereas George, who hadn’t been giving the game his full attention, had only three and Haycock, who broke off every now and then to watch the girl collecting the glasses, had not fared much better.

‘It’s Farrell’s round then,’ Rooke said, poking George’s pathetic cache of matches.

‘That’s not hospitable,’ Turland said. ‘He’s a visitor.’

‘It’s all right,’ George said quickly. ‘I got paid today.’ He took out his pay packet from his jacket pocket, slit it open with his thumb and began to pull out a note from inside. There was a lull in the conversation at the table beside them and Haycock leant over and quickly put his calloused hand over George’s, crumpling both notes and envelope back into his fist.

‘Are you daft, man? This isn’t the place to show your money about.’

George, feeling confused, stuffed the money back into his lower pocket and automatically, without thinking, patted his breast pocket where the painting still lay between the covers of his sketchbook. With a sickening jolt, he remembered the humiliation and disappointment of the afternoon and placed his hand flat upon the table as if to keep it in view and prevent it from betraying his feelings.

Haycock stood up, saying, ‘My shout. Same again all round.’ He made his way between the tight-packed tables to the press of men at the bar.

Turland scooped all of the matches back into the centre of the table. ‘You took some off Haycock again,’ he said to Rooke sadly.

Rooke grinned. ‘He’s so easy; he can’t keep his eyes off a bit of skirt.’

‘You’re incorrigible,’ Turland said with good humour.

‘What’s that mean? That another of your newspaper words?’

‘A hopeless case.’

Rooke just laughed.

When Haycock returned with the drinks, George put out of his head the Methodist teachings on the evils of drink that his parents and a lifetime of chapel meetings had dinned into him. He was surprised how easily he did it. He had never taken a drink before, and his only experience of public houses was waiting outside while tracts for the Temperance League were distributed by his mother and a group of chapel ladies. He was anxious not to let his naivety show: even Rooke seemed at home in the bar. How could he have thought that Violet might see him as a man when he lived the life of a boy? He drank fast, as if the golden liquid that he poured down his throat could fill up the empty space inside him where his hopes had once been. They played on and drank more: Rooke was sent up to the bar, grumbling, then Turland went again, refusing to let George take his turn as he was ‘a visitor’ and ‘had got him out of a jam, courtesy of the bike’.

As they played, the conversation among the men around them ebbed and flowed but returned always to the war: the horses being commandeered – what would the brewery do for the dray-carts? The barracks at the castle were filling up with new recruits; since Mons, men were flocking to the country’s aid … they said the Germans were doing unspeakable things; they said someone had heard engines over Cockermouth, Zeppelins spying out the land …

As he listened, George felt an uneasy mixture of excitement and fear. What if the Germans were to come here? It was all very well being an island but what if the navy didn’t hold? He imagined the heavy tread of marching feet through the town. An image from one of the recruitment posters came into his mind: a woman and child at a window, and suddenly the woman’s anxious face was his mother’s and the child clinging to her skirts was Lillie.

His father said it was best to stick to simple principles: ‘Thou shalt not kill’, that all should ‘beat swords into ploughshares’. George knew his own view: that he would protect Mother and the rest of his family with his life. He had heard his father preach at the Convention last year on the text of ‘turn the other cheek’. He imagined how badly such a sermon would be received in this changed world, against a backdrop of flags and posters, and men in uniform on the move, singing en route to the war. A piercing doubt about his father caught him for a moment before he turned its shaft away. Surely, if the enemy were at the door his father too would defend them all – turning the other cheek would be the same as turning your eyes away! Feeling disloyal, he comforted himself with the words he’d heard his father speak to his mother: that it would soon be over, that Europe didn’t have the gold reserves to fund a modern war, that it could only last months and that they should trust in the Almighty.

Turland, who had also obviously been listening in to the conversation of the older men, suddenly turned to Haycock and said, ‘I’ve been thinking of going.’

‘Signing up?’ Haycock stopped playing.

‘Someone’s got to do something, don’t you think?’

‘But you’ve got a good place at the paper. Not like me, poking about in machinery innards all day at the risk of losing my fingers. Now I have been thinking about having a bit of a jaunt. What on earth would you want to go for?’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ Turland said. ‘I want to do something worthwhile, I suppose, and we’re needed: we can’t let the Germans go striding around Europe picking up countries to put in their pockets, can we?’ He rested his elbows on the table and leaned in. ‘Doesn’t seem honourable somehow to know the army’s in retreat for want of men whilst I’m swanning around covering sports days and grand-opening sales.’

Rooke, who had been quietly gathering more of Haycock’s matches, his voice a little slurred, said, ‘Well, if you’re going, I’m going. We’ll be like the heroes in Valour and Victory. Champions to the rescue!’ He put his hands up in front of his shoulder as if cocking an imaginary rifle, jerked them upwards and threw his body backwards as if taking the recoil. An older man with baggy eyes and a well-trimmed beard twisted round on his stool from the adjacent table saying, ‘Well said, young man; that’s the spirit! Give those Deutschers what for.’

Haycock looked at Rooke sceptically. ‘Harry says they measure you, how tall you are … your chest and what-all before they let you in.’

‘Who’s Harry?’ George asked.

‘His brother,’ Turland filled him in. ‘He was in the Territorials so he’s already been mobilised.’

Haycock asked Rooke, ‘How old are you anyway?’

Rooke flushed: a blush that reddened his cheeks and rose to the tips of his ears. He shot a swift glance at Turland as if to refer the question to him, which George thought very curious.

‘Leave it, Haycock,’ Turland said.

‘It’s just that you have to be eighteen to join, nineteen if you want to serve overseas …’

Rooke stared fiercely at Haycock. ‘I don’t know how old I am.’

‘Don’t be daft.’

Turland said quietly, ‘Shut up, Haycock. Now’s not the time.’ He tapped his cards on the table whilst he thought. ‘We should go up to the castle together,’ he said. ‘Rooke might have more of a chance if they see us as a job lot.’

George imagined the three of them in khaki, swinging their arms as they marched together and suddenly felt awkward sitting there in his postman’s uniform. The role he’d been so proud of was safe, civilian. He felt reduced to a mere message-taker, little better than an errand-boy, while the others would be part of something huge, a glorious endeavour, taking their places as men. He was tipsily aware that somewhere beneath the muddle of his feelings about England and honour and protecting one’s family lay the unease he felt about seeing Violet again: a troubling mixture of deadly embarrassment that he had revealed something of his feelings, and shame that he hadn’t behaved with more gallantry. He felt an unbearable awkwardness that he had no idea how to overcome. Then his mind flipped unaccountably to Lillie and the fragile feel of her small bones as he lifted her that morning, and he felt a lump form in his throat.

At the next table, the bearded man was nudging his neighbour and drawing the attention of his drinking partners so that all turned round to look. One of them, who had a kitbag slung on the back of his chair, said, ‘You shouldn’t have too much of a problem. You’ll soon shape up, even the young ’un.’

Haycock spat on his hand and held it out over the jumble of glasses and cards.

‘Are you in, Farrell?’ Turland asked.

George hesitated. The scrutiny from the table behind had spread and even the men standing at the bar had turned to see what had caused the dramatic gesture.

‘Soldiers in the making!’ the bearded man called out, and with that, Turland and Rooke spat on their palms too and the three of them joined hands, fist over fist, to a chorus of approving voices. George leant back on his stool as if to move out of the bearded man’s eyeline.

‘Three soldiers and a postman!’ the man shouted and the swell of congratulation died away into laughter as George hunched his shoulders and stared into his pint. Rooke bent beneath his downcast face and grinned up at him, saying, ‘Cheer up, mate, plenty of time to change your mind.’

George shrugged and downed the pint in huge gulps until there was nothing left. He saw that he’d fallen behind the others; there was a full glass set ready in front of him. He tried to focus on the task of stretching out to pick up the glass but his hand seemed to move independently of his will, jerking forward and nudging the full glass so that it slopped a pool of beer on to the table. He stared at the beer still frothing on the dark wood.

‘Steady,’ said Haycock, setting the glass in his hand.

‘You shouldn’t have bought him that last one,’ said Turland.

‘Needs cheering up, doesn’t he?’ Haycock said. ‘Spot of woman trouble.’ He winked at Turland and dealt the cards again. Turland and Rooke picked up their cards and another game began.

George took a sup and put his glass down very carefully but waved Haycock away when he tried to give him his hand of cards. ‘I’ll pass this one up,’ he muttered.

We must have been here a while, George thought, as the girl who had been collecting glasses reached across a table to open a window and he saw her reflection in the pane and realised that it was now fully dark outside. He hoped that there was a moon and wondered how he would make the ride home without mishap otherwise. A cool draught of air reached him. He breathed it in deeply and tried to ignore the queasy feeling in his stomach and the sensation that if he didn’t concentrate very hard on the three of spades which lay abandoned in front of him, the room started to waver slowly on the borders of his vision.

The girl reached their table and began to gather up the empties. She had coarse features, hair the colour of brass and the high colour that often goes with it. Strands of her hair had escaped her pins and stuck to her brow and neck.

Haycock said, ‘Where’s Mary tonight then?’

‘She’s ill; I’m just filling in this once,’ the girl said. She paused to roll her sleeves up, revealing plump, freckly arms. She leaned across the table to pick up the empty glasses in front of George, and Haycock tipped his stool backwards so that he could give her posterior a long, appraising look. ‘Bottoms up,’ he said and drained the dregs of his beer. George thought this uncouth. Haycock sat forward again and put his glass down but as the girl reached to take it he moved it further away. She shot him a glance as if to say ‘I know your game’ but still leant over further to take it, and when he wouldn’t let it go and looked at her with a challenge in his eyes she laughed and drew it slowly from his fingers.

George, noticing as she bent forward that her figure beneath her blouse didn’t have the corseted solidity that he usually associated with the female form, but instead a loose movement as if all below was only constrained by petticoats, dragged his eyes back to her face. Feeling the effects of the drink, he was aware of a delay between thought and action and realised that he was staring, yet was strangely fascinated by her blond eyelashes, which gave her eyes a red-rimmed, unfinished look.

‘Your friend all right?’ the girl said to Turland. ‘He’s looking a bit queer.’

‘He’s had a fair bit to drink.’

‘Maybe more than he can manage,’ Haycock said, knocking George’s arm so that his elbow slipped off the table, jolting him into action. George sat up as straight as he could.

‘I’m perfectly …’ George found that even his lips now seemed to be rebelling against him, with a numb sensation as he pressed them together and tried to form the words. ‘… fine. And it’s my round,’ he finished, fishing around in his pocket for some money. He tried to rise but had to put his hand on the table to steady himself.

‘I’ll bring them,’ the girl said. ‘You stay here.’

George subsided and she picked out some threepenny bits and pennies from the handful he held out, her wet fingers leaving the remaining coins sticky in his hand.

Haycock and Turland were talking about giving in their notice at work. Both felt that their employers wouldn’t ask them to work it out; they would be released straight away if they had their military marching orders. Rooke said that when he decided to move out he just did it, although always on a payday – no point going without what was due to you. George stared into his drink; the conversation seemed too hard to follow. He very much wanted to go to sleep. He tried to marshal his thoughts by concentrating on what was before him; the beer reminded him of the colour of a beech hedge, ‘a distillation of autumn’. He thought the phrase rather good but couldn’t trust himself to share it in case it came out all wrong. The sound of the words moved through his head in a slow, pleasing procession. Why couldn’t he just curl up somewhere warm and go to sleep?

The voices of his companions rose as they explored the heady excitement of being able to escape their normal humdrum lives so quickly. The anticipated freedom of having extra money in their pockets bred madcap plans for their return. Haycock would join forces with his brother to sell motors; Turland would move to London and try his hand at a job on a bigger paper, maybe even take up travel as a foreign correspondent somewhere glamorous, ‘Paris or New York,’ he said grandly. Rooke said he would get the best cycle money could buy and eat out like a king every night. His ambition didn’t seem to extend further than a more comfortable version of the life he knew.

The girl returned with four tankards on a tray and Haycock suggested that they ‘down them in one’ so she stayed for the empties, standing with arms folded and wearing an amused expression. Rooke put George’s tankard in his hand, folding his fingers around the handle and ribbing him a little. Haycock counted them in, ‘One, two, three …’ and they lifted their elbows as one and threw their heads back.

With the first few swallows, George knew that this was a step too far. A horrible gurgling started up in his stomach and he set his glass down and put his head in his hands, trying to still the sensation that the room had begun to spin and that his stool was at the centre of the turning and seemed to be trying to buck him off. He heard the boys thump down the tankards and burst into a cheer at the same time as he felt the girl’s hand on his back; he smelt a mixture of sweat and face powder as she bent over him.

‘Not feeling too good?’ she said in his ear. ‘You come along with me.’

George was afraid to move or even look up, convinced that he would disgrace himself by either falling over or being sick.

‘Come on now, gently does it.’ She slipped her arm under his so that his whole forearm was supported. Once on his feet, she gripped his hand and he stumbled beside her, aware of a shout of, ‘Steady, Farrell!’ and the sound of his fellow drinkers drumming their fists on the table ever louder and faster. The girl ignored them and led him to the passageway that took them to the back door.

Outside, the air felt cool: his shirt and waistcoat were chill and damp with sweat. His upper lip prickled and his legs wanted to buckle beneath him as they walked into the yard. ‘Here,’ she said, pushing him towards the privy. ‘In there.’

He went in and pulled the door shut behind him. The smell of piss rising from the hole in the wooden bench seat of the closet was the final straw. He barely had time to sink to his knees and brace himself against the plank before he threw up what felt like everything he had drunk or eaten that day. Eventually, he rested his forehead on his arm, exhausted. It was wholly dark in the privy. George couldn’t abide dark, close places. Ever since his father had taken him, as a child, on an adventure down into the mine where he worked George had feared small spaces: the suffocating sense of enclosure, the tomb-like dark and the stale air pressing in on him. The tunnels, narrowing as they had gone further into the mine, were a source of wonder and admiration to his father, but they had terrified him. Their lowering roofs made his father stoop, casting a crooked shadow that stretched and shrank on the wet rock as he shuffled along in the nodding light of his lamp. Ahead and behind, the darkness was solid, as if they were moving through black treacle that parted for a moment before them only to ooze back behind them as they passed. He had known, even at seven years old, that he could never work in such a place, exiled from the sun and rain and wind, had felt that the earth and rock around him and the weight of the mountain above were pressing on his chest and stealing away his breath.

George stayed very still, waiting to feel a little better before attempting to stand up. Outside, there was a rustling noise, a shuffling against the wall, as if someone was trying to squeeze between it and the bushes. He thought of the bike, hidden behind the laurels, and hoped it was safe, but he hadn’t the strength to do anything about it. After a while, he took out a handkerchief and wiped his mouth with a wobbling hand. He realised that he was kneeling on an earth floor. He levered himself up, steadied himself against the bench seat and tried to dust down the knees of his uniform trousers. Having got himself upright, shakily he felt for the door latch, lifted it and went outside.

The girl was leaning against the wall of the privy, her hands behind her back. George felt a sharp stab of embarrassment to think she had been there all the time. ‘You needn’t have waited,’ he said. ‘I was perfectly all right.’ Then he thought that he had sounded ungrateful and added, ‘Thanks for bringing me out.’ He stuffed the handkerchief in his pocket.

‘You still look pretty poorly,’ the girl said, peering at him. ‘You should stay in the fresh air a bit.’ She took hold of his sleeve and moved along the wall, drawing him beside her. ‘That’s right, breathe it in.’ George drew in a breath that smelt of damp leaves, the pitch on the privy roof and a faint tang of tobacco as though someone had ground out a cigarette butt nearby.

She took his hand and began to rub it between hers, at first as if to bring life back into his fingers but then she put her thumb in his palm and moved it in a circle, pressing it into the concavity of his hand. George felt a hot current run through him, a disturbing reflex reaction, as though his body recognised an urgent message that his mind was too slow to decipher. His fingers closed around her hand. In a sudden movement, she swung herself round to face him and her arms reached up to entwine his neck as she leant the whole length of her body against him. The soft, yielding feeling of her body beneath her light clothes undid him. He put his arms around her and bent to kiss her but she turned her head away, instead nuzzling her face into his neck, kissing and licking. She took his hand and guided it to her breast, slipping it between the sticky cotton of her blouse and the warm heaviness beneath which George cupped, trembling, his head spinning, his body taking over. She pressed against him, moaning softly and he felt suddenly afraid, unable to stop himself, and thought that this was what she wanted him to feel. She was taking his hand again, pulling up her skirt. Oh God, he could feel the clip of her suspender beneath her petticoat. She was moving his hand up and down over the silky material, over her thigh and up to her buttock …

Suddenly a blinding light was in his eyes, so bright that at first they both turned their heads away.

‘Well, what’s going on here then?’ a man’s voice said, dropping the torch beam a little and running it over the girl’s open buttons and the curve of her breast. George, blinking in the light, couldn’t understand why she didn’t move away, didn’t cover herself. In his shock, George had the bizarre notion that they were caught in some music-hall tableau of static nudity, where the slightest movement would bring down the force of the law. Then, as if a moment of posing for a photograph were over, she pulled away and began expertly restoring her clothes to order.

‘That’ll be five shillings,’ she said matter-of-factly.

‘I’m sorry?’ George said, not understanding.

‘Five shillings,’ she said slowly as though explaining to an idiot. ‘You’ve had your pleasure, now pay up, there’s a good boy.’

‘But I didn’t ask …’ George started. ‘You …’ The sudden change of circumstances left him floundering. He couldn’t grasp what was happening or quite believe what was being requested of him. He felt weak and pressed his head back against the wall as if its cool solidity could give his mind focus. He started to tuck his shirt in and then stopped, feeling ashamed.

‘Come on, pay up,’ said the man, and this time George raised his head as he recognised the voice of the chap who had sat in the corner with the newspaper earlier in the evening; he squinted against the light, trying to see him. In an instant the torch was thrown down – he heard it hit the gravelly ground with a crunch – and the man was on him, slamming his head back against the wall and punching his fist into his gut. George doubled over, retching, a dry acidic heaving from the depths of his empty stomach. He sank down against the wall and slid to his knees, winded, unable even to shield himself against the man’s boot as it met his ribs and tipped him on to his side. He lay groaning, his eyes scrunched up in pain. He felt, rather than saw, the girl bending over him and then, with her small fat fingers, quickly feeling into his jacket pockets, pulling all their contents out on to the ground and picking through them. He heard a heavy and a lighter tread as both of them walked away.

The side of his face was pressed against the sharp gravel and he could feel a long string of saliva dribble from his open mouth. His arms were folded across his stomach as if to hold him together and contain the burning pain in his gut and the pulsing throb of his ribs. He could think of nothing but the pain yet he knew that when it finally abated, what was beyond it would be even worse: the vague outline of thoughts that heaved at the edge of his consciousness would resolve into monstrous, shameful shapes.

He could no longer feel the weight of the sketchbook against his chest. Slowly he stretched out one hand, trying to trick the pain through moving by degrees; groping across the dirt, he felt the crumpled handkerchief, the coldness of a few scattered coins. He couldn’t find it. He slumped back with a groan.

Across the yard, he saw the back door open, throwing a quadrangle of light across the steps and releasing the sound of voices and laughter into the air. A small figure came out and hesitated, peering around as if waiting for his eyes to get accustomed to the dark. George tried to call out but all the air seemed to have left his body and only a moan came from him.

‘Farrell?’ The figure came down the steps and picked its way towards him. ‘Farrell? Are you all right?’ Then Rooke bent over him, taking his elbow, trying to lift him up. ‘What the hell happened?’ He looked about him quickly, checking that whoever had done this wasn’t still around. He managed to raise George into a sitting position. ‘I’ll get the others,’ he said.

George hung on to his arm. ‘My book. I can’t find my book.’

‘Never mind that, we need to get you out of here,’ Rooke said.

‘I need it.’ George struggled to control his voice.

Rooke squatted beside him and felt around until he found the book. He put it into George’s hands and then ran back to get the others.

The book’s smooth covers were grainy with sandy earth. George brushed his fingers over them and put the book safe in his pocket, wincing as he lifted his arm. Rooke returned with the others who lifted him and got his arms over their shoulders so that they could help him along.

‘We’d better take him back to our lodgings,’ Turland said to Rooke. ‘You get the bike.’

Rooke pulled it out from behind the bushes and wheeled it along beside them.

‘Took your money, I suppose,’ Haycock said.

George nodded.

‘Did you see who it was?’

‘No. He jumped me from behind,’ George said, already forming the lie that he would tell and retell, already feeling the hot shame creeping through him, sordid and unclean.

3 (#ulink_c20970b7-1624-5055-abe8-cab6adae0587)

DANCE CARD (#ulink_c20970b7-1624-5055-abe8-cab6adae0587)

When Violet had first arrived at the Cedars, Elizabeth’s family home, Edmund had been away and she had been so busy, in the first week, meeting the Lyne family’s cousins and friends for luncheon parties, picnics and concerts, that she had almost forgotten Elizabeth had a brother. After a morning spent boating with a group of relations who had failed to include sunshades in their preparations, Elizabeth had felt the worse for the sun and suggested that they withdraw to their rooms for the afternoon, the better to enjoy the evening’s entertainment.

Violet, however, was unable to rest. Despite closing the drapes against the intense heat of the June afternoon and taking off her shoes and lying full length on the bed, her thoughts were too full of the unwonted excitements of the last few days, her mind a whirl of gowns and opera glasses, new faces, drives in the motor, parlour games and laughter. The room was stuffy, the satin quilt beneath her sticky and clinging, and at length she gave up, slipped her shoes back on again and decided to go in search of something to read.

Downstairs, the tall double doors of the library were open and Violet went in softly, glad that she wouldn’t have to risk breaking the oppressive quiet of the afternoon by their creaking. The room was lined with books from the floor to the ornately plastered ceiling, and was furnished with library steps to reach them. Chairs, couches and occasional tables stood around for the convenience of the reader, some arranged in a group in the centre, some placed with their backs to the room giving a view from the long French windows of the sloping lawns, elms and cedars. A large desk, belonging to Elizabeth’s father, stood to one side, littered with stamps, magnifying glass and glue pot and Violet felt that she was intruding a little and thought that she would choose something quickly and go.

Her eyes travelled over the books in the lower shelves, which were large, dull, leather-bound volumes of county history, and passed up through travelogues and heavy-looking biographies until she found a set of the Waverley novels on one of the top shelves. She wheeled the library steps along and positioned them so that they were well braced against the shelves; then, picking up the skirts of her afternoon dress in one hand, she awkwardly climbed up to find one that she hadn’t yet read. The set, tightly packed together, wouldn’t yield a volume easily. Getting a finger hooked into the top of the spine of the book in the middle, she pulled hard, dislodged several, then, juggling books, steps and skirts, tried to catch them and failed so that three volumes fell with an almighty thump on the polished wood floor.

There was a muttered curse of ‘What the devil?’ from one of the couches and a man sat up and rested his elbow on its upholstered back. He blinked and passed his hand over his face and through his dark hair, staring with a bemused expression as though unsure whether he was still in a dream.

Violet, still clutching a copy of Ivanhoe,said, ‘Oh! You startled me!’ and then flushed crimson, feeling foolish, as she had undoubtedly startled him first. Momentarily lost for words, she stared back. His tie was loosened, his waistcoat was undone and his sleeves were rolled back giving him a rakish look that was at odds with his neat moustache and candid grey eyes. ‘I’m so sorry to have woken you,’ she said, reaching to put the books that had fallen flat on the shelf back into position.

‘Oh, don’t trouble yourself about that. Here, let me help,’ he said, jumping to his feet and coming to the foot of the ladder. He picked up the other volumes and passed them up to her. ‘I’m Edmund, by the way. Who are you?’

‘Violet. Violet Walter.’ In reaching down to shake his offered hand, she almost lost the books again and he steadied her elbow.

‘You’re Elizabeth’s friend, aren’t you?’ he said. He broke into a wide grin. ‘She never mentioned you were such a big reader.’

Violet smiled as she put all but one of the books back. ‘I do like to read,’ she said, ‘but for an afternoon’s idle hour even I would find the full set daunting.’

‘Well, you’re welcome to as many as you can manage,’ he said, helping her down from the steps. She turned at the foot and they came face to face. There was a moment when they both stopped and looked – a beat, barely a pause, but it seemed to Violet that something passed between them: a strange instant of recognition. Violet drew away first, suddenly aware of the impropriety of their situation: alone together – and at this proximity. She stepped to the side but before she could pass him he said, ‘Must you go? Don’t run away. Elizabeth’s only told me a little about you; do come and tell me more. Please?’ and before she knew what she was doing she found herself steered to an armchair. Edmund solicitously tucked a cushion behind her, saying cheerily, ‘None of these chairs are comfy. They’re lumpy old horsehair things but we’re all fond of them just because they’ve always been here.’

‘Thank you, I’m very comfortable,’ Violet said, and then felt confused all over again as she realised that she should really be protesting that she must go.

Edmund said, ‘I see you favour the classics. Do you read the newer works as well? Forster? H. G. Wells? I can recommend Wells; he has a knack of warning us of where our current follies may lead us.’

‘I prefer Forster,’ she said, considering. ‘Wells’s view of the future is a little too bleak for my taste.’

‘We have the latest Forster somewhere; I’ll look it out for you. Have you been enjoying your stay so far? I hope Elizabeth has been looking after you and showing you around?’ Edmund tried to make this beautiful girl with the serious face feel more at ease.

‘Oh, we’ve had the most marvellous time. We went to see La Traviata and we had a wonderful picnic by the sea at Cockermouth with your father and mother and some of Elizabeth’s friends, and the cousins of course …’

‘They’re a jolly lot, aren’t they? We usually see a fair bit of them in the summer. Are you able to stay for long?’

‘A month, I hope, as long as my mother keeps well and can spare me from home.’

‘Well, we must make the most of your stay,’ Edmund said sympathetically, remembering what Elizabeth had told him of Violet’s circumstances. ‘What do you like to do the most?’

Violet told him about her photography and he listened carefully, asking her questions about shutter speeds and coloured filters, and suggesting places of interest locally where they could picnic and she could take some photographs. The conversation moved easily along as he told her of his recent studies at Cambridge and how much he had enjoyed the Officers’ Training Corps with its outdoor life of riding, camping and shooting. He told her that he was applying for a commission and hoped that his uncle, who was in the local regiment, would be able to arrange something for him. Ideally, he said, he would have liked a cavalry commission but he would have to take what his uncle could get for him and the chances were that he would end up in the infantry. ‘Foot-slogger more likely than donkey-walloper,’ he said, making her laugh, which drew from him a broad smile in return.

As Violet began to ask him more, she heard someone approaching the room and stopped abruptly. A housemaid, holding a pile of tablecloths and napkins, stood uncertainly in the doorway looking from one of them to the other. ‘Sorry, sir,’ she said to Edmund, ‘Cook said I was to lay for afternoon tea in here, sir, so’s we could open the French windows and have the draught.’

Violet, suddenly aware of how odd this must look: a lady visitor, unchaperoned, sitting knee to knee with the young gentleman of the house, got quickly to her feet.

Edmund stood too, saying, ‘Ah, yes, of course, Dolly. Miss Walter has just stepped in to find a book and I can see that I’m going to be in your way.’ He gave the girl a winning smile and she bobbed a curtsey. He turned back to Violet with a mischievous look in his eye and said, ‘I hope you’ll enjoy Mr Scott’s Ivanhoe, Miss Walter.’

‘Thank you. I’m sure I shall,’ Violet returned with equal formality and left the room. Behind her, she heard Edmund offering to open the French doors for Dolly, saying that they were rather stiff for her to manage. He engaged her in friendly conversation, distracting her with questions about the health of all below stairs and whether there had been any changes while he had been away.

Violet retired to her room and sat at the window with the book open before her. She had to admit herself charmed. She found herself recounting every step of their unconventional meeting and a strange sensation came over her once more as she thought of him helping her down from the steps and of his touch as he tucked the cushion behind her as carefully as if she were porcelain. She was not used to such attention, such cherishing, and certainly not to the way Edmund had made it so easy and natural to talk about herself. When Elizabeth put her head around her door an hour later to tell her that tea was served, she found that she had read two chapters of Ivanhoe without taking in a single word.

Entering the library once more, now freshened by a breeze from the garden, which sweetened the room with the scent of honeysuckle and fluttered the corners of the tablecloths, she was met by the sight of Mr and Mrs Lyne, Elizabeth, Edmund and three other houseguests. The party was assembled next to tea tables laden with sandwiches, ginger cake and a pale blue and gold tea service, while Dolly attended to a large urn on a side table.

‘Ah, Violet,’ Mrs Lyne said as the gentlemen rose, ‘let me introduce my son, Edmund.’

Violet, taken by surprise, almost said, ‘Thank you but we’ve already met.’ She bit back the words as they formed in her mind and hesitated, casting around desperately for the phrase that she needed.