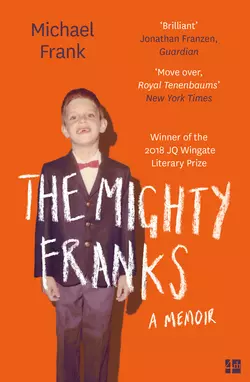

The Mighty Franks: A Memoir

Michael Frank

A TELEGRAPH BOOK OF THE YEARA NEW STATESMAN BOOK OF THE YEARA story at once extremely strange and entirely familiar – about families, innocence, art and love. This hugely enjoyable, totally unforgettable memoir is a classic in the making.‘My aunt called our two families the Mighty Franks. But, she said, you and I, Lovey, are a thing apart. The two of us have pulled our wagons up to a secret campsite. We know how lucky we are. We’re the most fortunate people in the world to have found each other, isn’t it so?’Michael Frank’s upbringing was unusual to say the least. His aunt was his father’s sister and his uncle his mother’s brother. The two couples lived blocks apart in the hills of LA, with both grandmothers in an apartment together nearby.Most unusual of all was his aunt, ‘Hankie’: a beauty with violet eyelids and leaves fastened in her hair, a woman who thought that conformity was death, a Hollywood screenwriter spinning seductive fantasies. With no children of her own, Hankie took a particular shine to Michael, taking him on Antiquing excursions, telling him about ‘the very last drop of her innermost self’, holding him in her orbit in unpredictable ways. This love complicated the delicate balance of the wider family and changed Michael’s life forever.

Copyright (#ulink_4109d306-f63f-533a-aab4-8a765541f73a)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

First published in the United States in 2017 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Copyright © 2017 by Michael Frank

Cover image shows author aged 6

Designed by Jonathon D. Lippincott

Michael Frank asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following material: Excerpt from “Make Your Own Kind of Music.” Words and music by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. Copyright © 1968 Screen Gems–EMI Music Inc. Copyright renewed. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, Tennessee 37219. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

Excerpt from “Our House.” Words and music by Graham Nash. Copyright © 1970 (renewed) Nash Notes. All rights for Nash Notes controlled and administered by Spirit One Music (BMI). All rights reserved. Used by permission of Alfred Music.

Epigraph to Maxine Kumin’s poem “Looking Back in My Eighty-First year” by Hilma Wolitzer. Courtesy of Hilma Wolitzer.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008215224

Ebook Edition © 2018 ISBN: 9780008215217

Version: 2018-04-27

Dedication (#ulink_7015f93b-5b70-5d7e-9a7d-15da033469f6)

To my parents and (how not?) my aunt

and in memory of my uncle

Epigraph (#ulink_2947a2de-56cf-556b-9023-c5b72a57fd9d)

Omnia mutantur, nihil interit.

(Everything changes, nothing is lost.)

—Ovid, Metamorphoses

Contents

Cover (#u5b27a761-420f-5ce0-8b68-093c9753b9e8)

Title Page (#u922fc115-099a-5175-b88f-15e4d7bce8c1)

Copyright (#uf2adc7aa-72e3-59dd-83d4-629534a24e90)

Dedication (#u2a144f0c-c557-5583-bc09-2c3ed9a8d9a6)

Epigraph (#u91f771ba-5b00-577a-ad08-995de6fff130)

Overheard (#u21dd46a1-fe73-5556-a593-079b571155ad)

PART I (#ub2379fa7-b6ca-5561-8a7f-971353b78a0f)

1. The Apartment (#u2881befd-6e7d-53c8-b2c6-1ce3cb18dd4c)

2. Ogden, Continued (#u10caebfe-ba25-57b9-aecb-64399ce6287c)

3. On Greenvalley Road (#ue9b00093-07f9-5367-971d-743341bfde2a)

4. Safe House (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

5. My Uncle’s Closet (in My Aunt’s House) (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Off the Hill (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Five Places, Six Scenes (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Last Room (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Goodbye to the Closet (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Fall and Decline (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

OVERHEARD (#ulink_45ab3e28-e028-53d8-adf3-599eae11d5e8)

“My feeling for Mike is something out of the ordinary,” I overhear my aunt say to my mother one day when I am eight years old. “It’s stronger than I am. I cannot explain it. He’s simply the most marvelous child I have ever known, and I love him beyond life itself.”

Beyond life itself. At first I feel lucky to be so cherished, singled out to receive a love that is so vast … but then I stop to think about it. I am not sure what it means, really, to be loved beyond life itself.

Do I love my own mother that way? Does she me? Is such a thing even possible?

And why me and not my two younger brothers? What do I have that they do not?

“I wish he were mine,” my aunt blurts after a moment.

From where I am crouching on the stairs in the entry hall, I can feel the weather in the room change. A long, tense pause opens up between the two women. I hear them breathing, back and forth, into that pause.

They are sitting at right angles to each other, I know, my aunt on the sofa, my mother in the chair next to it. This is how they always sit in our living room, not face-to-face but perpendicular, so that they don’t have to make eye contact if they don’t want to.

“I wish you had a child of your own,” my mother says carefully. Ever the second fiddle, the third born. The diplomat.

“So do I,” says my aunt in a pitched, emotional voice.

Maybe you would be a different person if you did.

My mother does not say this. She thinks it, though. Everybody in our family does. But that’s not what happened.

This is.

PART I (#ulink_f6493152-fa4d-5339-9aa1-debdc5df70f2)

ONE (#ulink_83311bf7-3be3-5613-8a71-af19d9c2dbb3)

THE APARTMENT (#ulink_83311bf7-3be3-5613-8a71-af19d9c2dbb3)

For a long time I used to wait in the dining room window. I waited in the afternoon, when I returned from school, and I waited on Saturday mornings. Now and then I waited at the edge of the driveway, because from there I could see farther up the hill, almost to the top. When the Buick Riviera appeared, its fender flashing a big toothy metallic grin, I felt happiness wash over me; happiness braided together with anticipation and excitement too, since it meant that within minutes my aunt would be pulling up to take me on one of our adventures.

My aunt was the one person in the world I was always most eager to see. Sometimes she came bearing gifts, special books or treasures related to the special interests she and my uncle and I shared: art and architecture, literature, and, since my aunt and uncle were screenwriters, movies (never “film,” that was the celluloid of which movies were made). But what I loved even more than receiving tangible things was going off with her, alone, without my younger brothers or my parents; being alone with her, with the force of her attention, the contents of her mind. And her talk, which was like an unending river emptying itself into me. Our time together was larky. You really are the best company a person could ever hope for, Mike, she said, bar none. She made me feel clever merely by being with her and listening to her, learning what she had to teach, absorbing some of her spark—her sparkle.

My aunt and I went off alone together often because she and my uncle didn’t have any children of their own, and they lived within minutes of our house, and because we were doubly related. There was a refrain we children learned to recite when people asked us to explain our intertwined family—

Brother and sister married sister and brother.

The older couple have no children, so the younger couple share theirs.

The two families live within three blocks of each other up in Laurel Canyon—

and the grandmothers live in an apartment together at the foot of the hill.

It wasn’t very poetic, but it got the facts across and made the situation seem almost normal, as summaries sometimes do.

The situation was not remotely normal, but naturally I did not understand that at the time.

Our relationship, my aunt said, was special. She called our two families the larky sevensome or, quoting my grandmother, the Mighty Franks. But even within the larger group, she said, you and I, Lovey, are a thing apart. What we have is nearly as unusual as what I have with Mamma. The two of us have pulled our wagons up to a secret campsite. We know how lucky we are. We’re the most fortunate people in the world to have found each other, isn’t it so?

Only we hadn’t found each other. We had been born to each other; to—into—the same family. Did that make a difference? Was a bond this strong meant to grow in this soil, and in this way? I was far too besotted with my aunt to ask any of these questions. My aunt was the sun and I was her planet, held in devotional orbit by forces that felt larger than I was, larger than we were. You could call it gravity. Or alchemy. Or intoxication. Or simply love. But what an unsimple love this was.

I heard the car before I saw it: the familiar motor slowing as it approached Greenvalley Road … the high-pitched squeak the wheels made as they widened into that precise turn that landed the Buick smack-dab in the center of our driveway … and then the horn, whose coloration changed depending on the driver’s frame of mind. The jubilant tap-tap that soon ricocheted across the canyon meant Come along quick-quick, which was my aunt’s preferred pace in all matters always.

I flew out the front door, for a moment forgetting my ever-present Académie sketch pad and pouch of pencils. Halfway down the garden path, I remembered and doubled back to retrieve them from the entry hall. Outside again, something, some sense, made me glance back at the dining room window. My two younger brothers were standing and looking for me in the same place where I had been looking for my aunt. I lingered just long enough to see the confusion in their faces. Then I headed for the car.

Once I had settled into the front seat, but before my aunt had backed us out and on our way, I glanced again at the window, where my mother had now joined my brothers. She had placed a comforting palm on each boy’s shoulder. There was no confusion in her face. It was very clear. To me it said: Why just Mike, why yet again?

It was the cusp of the 1970s, and my mother had cut off all her hair, which until recently her hairdresser used to pile up on top of her head like an elaborate pastry. She’d stopped wearing heavy makeup too. She’d exchanged her dresses and skirts and blouses for blue jeans and T-shirts accessorized with colorful beads, and she’d begun putting strange new music on our record player, albums by Carole King and Joni Mitchell and the Mamas and the Papas, all of whom lived near where we lived in Laurel Canyon. As she cooked and cleaned and took care of my younger brothers she sang—

But you’ve got to make your own kind of music

Sing your own special song

Make your own kind of music

Even if nobody else sings along

Where is the wit? my aunt said when she heard these lyrics. Where is the panache? She and my uncle believed that Brahms was the last composer to belong in what they called the top drawer, though they did open a tiny side compartment for Irving Berlin and the Gershwins, especially when sung by Ella, whom they referred to solely by her first name.

This recent haircutting of my mother’s was the first of many evolutions in her appearance over the decades—her look changed with the times, while my aunt’s remained fixed in 1945, the year she met my uncle at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where they were both young screenwriters.

My mother was short—petite and mignonne, that’s our Merona, my aunt said. Adorable, she said, pronouncing the word àla Française, as if she were speaking about a little girl, or a doll. My mother’s doll-like tendencies—such as they were—had been in slow retreat ever since she had had her children, but to my aunt, Merona was in many ways still the timid thirteen-year-old she first met a few months after she and my uncle had begun going out together.

There was nothing remotely doll-like about my aunt. She was a tall, big-boned, round-faced, incandescent-eyed woman—formidable, people often said of her, though never with the hint of mockery that was conveyed when the word was pronounced with a French accent and certainly never to her face. I considered her quite simply to be the most magical human being I knew. Everything she touched, everything she did, was golden, infused with a special knowledge and a teeming vitality that transformed an ordinary conversation, or meal, or room, or moment, into an enchanted one. Not just to me but to lots of other people, she was a great beauty, part Rosalind Russell, part (brunette) Lucille Ball, though she mockingly—apparently mockingly—described herself as the forever too-tall, too-ugly adolescent with the imperfect nose that her mother had had “revised” as a seventeenth-birthday present. Her hair went up—high—higher even than my mother’s ever did—well before the bunning years. She fastened flowers or, memorably, leaves in these rounded towers, or wrapped them in scarves (bandannas, leopard or zebra prints, plaids), or concealed them behind berets, tams, cloches, or baseball caps she chose for their color, not because of her affinity for any particular team. She colored her eyelids blue or violet and well into the 1990s penciled a flapperish beauty mark at the top of her right cheek. She wore quantities of jewelry, and as she aged, more and more of it, often collated into thematic collections as profuse as the collections of objects in her house, ivory one day, amber the next; coral, gold, silver, crystal, malachite, lapis, pearl, or jet, depending on her mood or outfit. She treated herself, essentially, as a surface to decorate and, like the other surfaces she decorated, the finished effect asked to be noticed, always. Was noticed, always.

Her linguistic powers were inimitable. Intimidating, at times. She commanded torrents of words that merged into impeccable sentences the way raindrops collected into puddles. In story meetings she was a master of the pitch. She sat forward in her chair, elbows on her knees, a Merit smoking itself in one hand, and let fly. In fifteen, twenty minutes, to a hushed room, she would render an entire movie, from FADE IN to FADE OUT, without glancing at a single written note.

Her scent was a Caswell-Massey men’s cologne she bought at I. Magnin. When I climbed into the car its spiciness came gusting up out of her collar as she lowered a rouged cheek down to my height.

I kissed her, and she eased the Buick out of the driveway. “Reach around in back, Lovey,” she said.

I brought forward a wrapped package tied with a bow so crisp it might have been dipped in starch.

“What are you waiting for? Go ahead. Open it.”

The present was a book titled Famous Paintings. I glanced inside. Each chapter was devoted to a different subject: landscape, portraits, people working, children at play.

“Thank you, Auntie Hankie,” I said. “It’s beautiful.”

Again the cheek lowered. Again I kissed it.

“A little something to celebrate our Saturday together.” She nudged me with her elbow. “I’m sure that you will be an artist one day, Mike. I’m convinced of it. Everything you do has such style. Really and truly. It’s as if you’ve been immersed in aesthetics your whole entire life.”

I was nine.

“Make beauty at all times. It’s one of our family tenets, you know.”

“What’s a tenet?”

“A rule you live by. You build your life by.”

“Make beauty. At all times.”

“Yes. In what you draw or paint, in the houses you inhabit. In the way you speak too. And write. And of course be fast about it. Quick-quick. You’ve heard me say that before.”

I nodded.

“There’s plenty of time to sleep in the grave.”

I must have seemed puzzled, because she added, “It means no stopping, no roadblocks allowed. No naps.”

My mother took one every day.

“You must make every moment count,” she went on. “And you must never be afraid to dare. Imagine if Huffy had not dared—imagine if after ten long, horrible years of the Depression in Portland she had not seized the opportunity when Mayer granted her an interview. She piled your father and me and Pups Frank into the Nash and drove straight to Los Angeles, and she knocked the socks off old L.B.M. Everything changed after that. Everything, all of it, everything that makes us the Mighty Franks, comes from that moment, from Huffy, because of her boldness and her courage. Do you understand?”

I shook my head.

“Well, you will. One day. I’ll make sure of that.”

We had glided down out of the canyon. As she turned right onto Laurel Canyon Boulevard, she continued, “Follow your heart wherever it takes you. And always give away whatever possession is most precious to you.”

I looked down at the pages of my new book.

“You mean I have to give this to Danny or Steve one day?”

She cocked her head. “I would say not in this particular case, Lovey. Your brothers’ interests are so markedly different from yours, wouldn’t you agree? Danny—now he is a budding scientist. A logistician. It’s written all over him. He’s going to be a man of facts. I’m as sure of it as I am of my own breath. As for the little one … I see athletics in his future. He’s very skilled physically, just like my brother. Maybe like him he’ll develop a gift for business. Yes, I’m sure he will. We need that in the family, do we not? As a kind of ballast. It’s only practical. Literature, though? Art, architecture? The creative in any and all forms of expression? That’s your purview.”

Purview was like tenet, but I didn’t have to ask. “It means area of expertise. Strength.” She gestured at the book. “No, this one is earmarked for you. As is so much more.”

So much more what? I wondered. As if she could read my mind, my aunt added, “A collector does not spend a lifetime assembling beautiful things merely to have them scattered after she’s gone.”

She turned her face toward me. In her eyes there was that familiar sparkle. It blazed for a moment as she smiled at me, then drove on.

At Hollywood Boulevard we veered left onto a stretch of road that was wholly residential and lined, on the uphill side, with a series of houses that my aunt had previously taught me to identify. Moorish. Tudor. Spanish. Craftsman. Every time I watched these houses flash by the car window I wondered how they could be so different, one from the other, and yet stand next to one another all in an obedient row. Entire streets, entire neighborhoods, were like that in L.A.: mismatched and fantastical, dreamed-up houses for a dreamscape of a city.

At Ogden Drive we turned right, as we always did, and my aunt pulled up in front of number 1648. The Apartment. That is simply how it was known to us: The Apartment. We’re stopping by The Apartment. They need us at The Apartment. Your birthday this year will be at The Apartment. There has been some very bad news at The Apartment.

She never taught me to identify the style of The Apartment, but that was probably because it didn’t have one, particularly. A stucco building from the 1930s, it wrapped around an interior courtyard that was lushly planted with camellias and gardenias and birds-of-paradise, but what mattered most about The Apartment was that, for many years, since well before I was born, my two grandmothers had lived there—together.

“Quick-quick,” my aunt said as she turned off the ignition. “We’re nearly ten minutes late for Morning Time. Huffy will be worried to death.”

Huffy—the older of my two grandmothers, the mother of my aunt and my father—was sitting up in bed, reading calmly, when we hurried into her room. She was in the bed closest to the door. The two beds were a matched pair whose head- and footboards were capped with gold-painted, flame-shaped finials. She looked like she was riding in a boat, a gilded boat that was bobbing in a sea of embossed pink and white urns and wreaths that were papered onto the walls.

“I’m sorry we’re late, Mamma,” my aunt said. “Mike and I were engaged in rapt conversation, and I lost track of the time.”

My grandmother’s hair had come loose in the night, and she wasn’t wearing any makeup, but with her erect posture and her dark focused eyes she still, somehow, seemed alert and all-seeing. “It’s Saturday,” she said as she removed her reading glasses. “Today is the one day you are meant to slow down, my darling. I’ve told you that before.”

“There’s plenty of time to slow down in—” my aunt started to say. “Anyway we’re here now.”

“Is the boy going to noodle around with us this morning?” my grandmother asked.

My aunt smiled at me. “We need his eye, don’t we?”

“He does have a good one,” said my grandmother.

“Of course he does. I trained him myself.”

Morning Time was the sacred hour or so during which my aunt brushed her mother’s hair, wound it into a perfect bun, and pinned it to the top of her head before helping her put on her makeup and her clothes. Afterward she made my grandmother breakfast and sat nearby while my grandmother ate, so that they could visit before my aunt drove back up the hill and (on weekdays) sat down with my uncle to write.

This ritual went back to before I was conscious. It began when my grandmother had The Operation—never further detailed or explained—after which, for a while, she needed help dressing and doing up her hair. It had long since evolved into the routine with which the two women began their days, seven days a week without exception.

During the first part of Morning Time, the grooming and dressing part, I was always sent to wait in the living room. Often, as on this morning, I waited until my aunt had closed the door behind me, then I slipped down the hall to Sylvia’s room. Sylvia was my “other” grandmother, Merona and Irving’s mother.

Her door was closed, as usual. I pressed my ear to it, then knocked.

“Michaelah?”

I opened the door just wide enough to fit myself through, then I closed it again. “I wasn’t even sure you were here,” I said.

“I don’t like to be in Hankie’s way when she’s making breakfast.”

“What about yours?” I asked.

“Later,” she said with a shrug.

She was sitting on the corner of her bed, fully dressed, a folded newspaper in her lap. Her room was half the size of Huffy’s, and had no grand headboard with leaping gold flames. The bed was the only place in the room to sit other than a low, hard cedar hope chest.

Besides the hope chest, there was a high dresser on top of which stood several photographs of Sylvia’s husband, my striking-looking rabbi grandfather who died before I was born; these pictures were the only thing in the entire room—the entire apartment—that was personal to Sylvia, other than the radio by the bed, which was tuned to a near whisper and always to the local classical station.

“Are you coming out with us this morning?” I asked.

Sylvia’s head fell to an angle. It was as though my grandmother—my second grandmother, as I thought of her—was always assessing, or taking careful measure, before she spoke or acted.

“I think not—today.”

Physically Sylvia was smaller and shorter than Huffy, as my mother was smaller and shorter than my aunt; even her nose and eyes were smaller, more delicate and tentative. Dimmer too, you might say, except that they missed very little.

These small noting eyes of hers peered down the hall, or where the hall would have been visible if the door had been open.

“Maybe next week,” she added.

I knew she was lying. She knew I knew she was lying. We’d had a version of this conversation many Saturdays before.

“Monday I’m on the hill,” she said, meaning at our house on Greenvalley Road, where she could cook in our kitchen and eat kumquats off the tree and read in the garden under the Japanese elm in the backyard and let the vigilance drain out of those small eyes. “I’ll make tapioca.”

“Oh, yes, please,” I said. “And a sponge cake?”

“If you like.”

I nodded.

“Michaelah,” she said.

“Yes, Grandma Sylvia?”

“They’ll be impatient if you’re gone too long.”

“It’s only been a few minutes.”

She glanced at the door again. “Best to close the door when you go back out.”

The door to Huffy’s room was still closed. I found my sketch pad and stretched out on the braided rug in the living room.

As I tried to decide what to draw, my eye landed first, as it often did, on the painting that hung just above and to the right of the wing chair where Huffy preferred to sit during family gatherings. If there had been a fireplace, the painting would have hung over the mantelpiece, but there wasn’t, and this picture didn’t need that extra emphasis. It was already italicized—underlined. The painting was a portrait of my aunt, the epicenter of the room as she was of our family.

Harriet—Harriet Frank, Jr.—was her public name, her professional name. At home she was known as Hank or Hankie, therefore Auntie Hankie, or sometimes Harriatsky or, later, Tantie.

There was quite a confusion around the nomenclature of these women. Huffy had been born Edith Frances Bergman in Helena, Montana. She discarded the Edith early on because she disliked it. She went by Frances as a girl in Spokane and a young married woman in Portland. She remained Frances Goldstein—her married name—until in the mid-1930s she hosted a local radio program, which she called Frances Frank, Frankly Speaking; soon afterward she became reborn as Frances Frank, changing her last name and persuading her husband to change his and the children’s too. Several years later, in 1939, when she remade her life again, moving from Portland to Los Angeles, she appropriated her daughter’s name, a new name for a new life. She became Harriet senior, and my aunt, therefore undergoing a name change of her own, became Harriet junior.

No one thought this was strange: a mother taking her daughter’s name so that they could become a matched set.

“Harriet is an interesting name,” my grandmother declared. “Harriet is a writer’s name.”

Harriet junior became a writer—a screenwriter. No one thought this was strange either.

Or this: “Huffy and I know each other’s most intimate secrets. There’s nothing really that we don’t know about each other. Not one stitch of a thing.”

Or: “We’ve never had a cross word in our lives. Not a single one.”

Or: “Hankie and I are not merely mother and daughter. We’re best friends. We’re beyond best friends.”

They loved their pronouncements, my grandmother and my aunt, almost as much as they loved their nicknames. My uncle was Dover (his middle name bumped forward), Puddy, Corky. Another aunt was Frankie or Baby. My father was Martoon, Magoofus, Magoof.

I was Lovey or Mike.

Harriet senior was Huffy (as in: HF + y), always. Sylvia, my other grandmother, never had a nickname. Sometimes she might be shortened to Syl, but that was all. My mother, Merona, sometimes became Meron. But never anything more affectionate than that.

It was California. Blazing, sun-bleached Southern California: most any other nine-year-old boy would have spent his time outdoors playing under all that sun and sky. I spent mine lying on the braided rug, looking up at the painting of my aunt—my sun, my sky.

The portrait had been painted by a Russian cousin of my grandmother’s called Mara, who during the war had been banished to Siberia, where she was sent to a gulag and forced to paint pictures of Stalin for the government. “Your aunt and I went to Yurp together in 1964,” Huffy told me—Yurp being, like Puddy or Hankie or Magoof, a nickname, though for an entire continent instead of a person. “It was a dream of ours forever. Mara’s sister, Senta, who survived by hiding in an attic, had spent nearly twenty years trying to get her out of the Soviet Union. We found them living together in an apartment in Brussels. Every morning after breakfast your aunt and I went to their house and sat for her until dinner. We made up for a lot of lost time on that visit. And while I sat there, can you guess what I thought about?”

I shook my head.

“How grateful I was to my parents for deciding to come to America when they did. Do you know what I mean by that?”

I shook my head again.

“I mean that otherwise I might well have perished, like so many people in our family.”

My grandmother focused her dark eyes on me. “That’s what would have happened to me for no reason other than I had been born a Jew,” she said. “And if I had been murdered, that means your father would not be here, which means you would not be here.”

“Not Auntie Hankie either?” No Auntie Hankie was almost more difficult to conceive of than no me.

“No, not even our darling Hankie would be here …”

Her dark eyes shone. She was quiet for a moment. “That is very difficult to imagine, is it not?”

“It’s impossible,” I said.

My grandmother smiled enigmatically. “Yes, impossible. I quite agree.”

My aunt and my grandmother each had the other’s portrait hanging in her house. The portrait of my aunt was the larger of the two and darker, both in its palette and in the way it hinted at my aunt’s lurking black moods. How this distant cousin—a painter of Stalin—got at this in my aunt, and after knowing her for only a week, was a mystery.

Then there were her eyes. It was the kind of thing people made jokes about in portraits, but my aunt’s eyes truly did seem to follow me wherever I went. This may have had to do with the fact that her eyes weren’t merely in the painting but reflected in several other places in the room at the same time: in the reverse paintings on mirrored glass of Chinese ladies that hung over the bookshelves and, more prominently, on the wall opposite the portrait, where there was a mirror, very old, as in seventeenth-century old, Flemish, with a thick Old Master frame made out of alternating strips of ebonized and gilded wood. Its dim spotted glass showed my aunt back to herself, so that when I came between the painting and the mirror, I felt my aunt was looking at me from two directions, or else that I was interrupting a secret conversation, self unto self unto self, into infinity.

The mirror also made it possible for my grandmother, from her customary place in the wing chair, to look across the room at the mirror image of the painting of her daughter, who was therefore never out of her sight.

I decided that for my drawing I would try to capture the mirror capturing the picture of my aunt. Clever! I started with the frame, and then I moved toward the shape of Auntie Hankie’s head. It wasn’t easy to get right; not easy at all.

After half an hour the door swung open, and in an explosion of sound and shifting currents of air my aunt came barreling toward the kitchen like a fighter stepping into the ring. She busied herself there for several minutes, then just as the smell of toasting bread began to reach the living room, she poked her head in to check on me. With a rapid glance at my sketchbook she said, “But, Lovey, is doodling the absolute best use of your time when right over your shoulder a whole library is just waiting for you to explore?”

I looked down at my drawing. A doodle? I felt my cheeks burn with shame for being such a failure. How was I ever going to be an artist if I couldn’t draw one of the subjects I knew best in the world? I quietly folded the drawing in two and closed my sketch pad.

My aunt approached the bookshelves and bent down. She ran her fingers along the spines of novels by Dickens … then Thackeray … then Trollope. She stopped at How Green Was My Valley. “This was an absolute favorite of mine when I was a girl,” she said, before moving on to two other books, which she lifted down from the shelf and handed to me. “Take my word for it, Lovey, between Of Human Bondage and Sons and Lovers you’ll learn everything you need to know about what it feels like to be a certain kind of young person. Your kind, if I may say.”

I let the books fall open in my lap and peered dubiously at the river of dense print. My aunt said, “But you have a sharp mind, Mike, do you not? Of course you do. It’s time to get started, quick-quick, on reading grown-up novels …”

When I didn’t say anything, she added, “You don’t want to be average, do you? To fit in? Fitting in is death. Remember that. You want to stand apart from your peers. Always.”

Thanks to my aunt—my aunt and uncle—I was as far from fitting in with my peers as it was possible for a nine-year-old to be. I didn’t even know what fitting in felt like. And I was proud of that. Ridiculously proud, at times.

Nearly as sacrosanct as Morning Time were my aunt and grandmother’s Saturday antiquing excursions. These were mental health days, but they also had a clear purpose, since a static room is a dead room, and living in a dead room wreaks havoc on the spirit (—Harriet junior).

Senior and junior both approached shopping, this kind of shopping, with a connoisseurial rigor. Setting off with them on a Saturday was similar, I imagined, to what it must have felt like to travel with them to Yurp, which was in a way what these excursions of theirs were like, mini voyages across time, history, and culture, to distant worlds—worlds reconstituted by the past as contained in things.

Only they weren’t merely looking for a pair of candlesticks or a charger or another piece of Chinese lacquer; they were also training “the boy” in what was authentic or a repro, g. or n.g., period or—heaven forbid—mo-derne, a word whose second syllable was drawn out and pronounced with an exaggerated sneer.

I found these Saturdays to be alternately thrilling and unnerving. Heaven help me if I picked up something, even merely to investigate, and heard that piercing sotto voce n.g.—for “not good.” It was the equivalent of being told that I was n.g., or that I was an idiot. Of course I was an idiot. What could a kid know about Lewey Schmooey (as he, or it?, was described in a lighter spirit); how could he tell vermeil from ormolu, Palladio from Piranesi? It was as hard (almost as hard) as being read a paragraph of Dickens and another of Austen and being asked to say which was which. A boy who wanted to remain in this school (this family) made it a point to learn. The names and dates, the facts and figures, the periods, the styles (in prose, the voices; in movies, the look). The techniques: dovetailing over mitering, chamfering and pegging, feather-versus sponge-painting … before long it would be showing versus telling, the active versus the passive voice, plain transparent Tolstoyan prose versus Faulknerian flourishes versus Proustian discursions …

My aunt had several places she liked to noodle around—in Pasadena and out along Main Street in Venice and, when she was feeling particularly ambitious (or flush), in Montecito or down near San Juan Capistrano, where some of the more top drawer dealers did business. Today we were staying local, though—our destination was a cluster of shops way down on Sunset Boulevard near Western Avenue.

In the first shop we came to I picked up a lacquer tray that had two Chinese figures on it. This looked like it would fit into my grandmother’s apartment, and so it felt like a safe choice. No sooner had I reached for it than my aunt’s hand shot out. “No, not that, Mike. It’s repro. N.g.”

It was all in the tone, an icy dismissal that made an already small me feel like an even smaller me. And yet I kept trying, I kept yearning to be one of them, to know what they knew, to see what, and how, they saw; to win, and keep, their approval, their acceptance, their love.

Again and again my aunt’s head shook dismissively. Again and again I would try.

“That’s better. There you go.”

And again.

“Better still.”

But why? The why always came from my grandmother. Why is this good, why do we care? “Discernment is about judgment. It’s about knowledge. This is a good desk because it has good lines. Because no one has put garbage on it to make it look new, or fake. Because it makes you imagine.”

“Imagine what?”

We were standing in front of a tall piece of furniture. A secretary. I knew that much at least. It had a drop front, behind which there were many secret compartments. Some of them with tiny keyholes so that they could be locked.

“The man—no, the woman—who sat here, and wrote letters. Secret letters. Or in her diary. Imagine writing it two hundred years ago.” My grandmother opened one of the compartments. “And keeping it here.”

“And this ink stain,” said my aunt, joining in. “It’s from when she was disturbed at her work.”

“Disturbed?” I asked, confused.

“By her husband,” said my aunt. “Think of the painting by Vermeer. The woman writing a letter? It’s in your book. She looks up with a start, just like in the painting. She knocks over the bottle. The ink, just a few drops, sinks into the wood as a human fate is being decided, and quickly …”

My aunt and my grandmother exchanged one of those glances—I knew them well—that suggested they had sidestepped into their own private communication, the equivalent of a compartment in the desk I did not have access to.

“She doesn’t want him to know what she’s writing,” said my grandmother. “She has to choose between protecting her diary and protecting the table. She chooses the diary, of course. Because of her secret life. Do you understand?”

I nodded, because that was what was expected. But I had no idea what they were talking about. None at all.

Better had turned out to be a pencil box; even though it was Victorian (which like mo-derne usually received a crisp, definitive n.g.), it had two figures painted on its lid—in the Chinese manner, of course—and was useful what’s more. “You can keep the tools of your trade in it,” my aunt said jovially. “We can do away with that ordinary little pouch of yours. What do you think, Lovey? Would you allow me to make you a present of it?”

The suspensefully anticipated question. It came along at one point, sometimes at several points, on each antiquing excursion.

“Oh, yes, Auntie Hankie.”

“And what about these bookends?” she said, taking down from a shelf two bronze bookends in the shape of small Greek temples. “They would help organize your library at home.”

“They’re beautiful, Auntie Hankie.”

“We don’t mind if there’s a small scratch on one of them, do we?”

I shook my head. “It’s a sign of age,” I said.

“A sign of age!” said my grandmother, delighted. “The boy truly is a quick study.”

A very special treat after one of these Saturdays was being invited to spend the night on Ogden Drive. The invitation would emit from the wing chair, which was hard not to think of as my grandmother’s throne. (Sylvia’s chair, which stood across from it, was smaller, its seat closer to the ground.) If my mother had not been alerted ahead of time and had not prepared a suitable bag, there would be a flurry of discussion: What will the boy sleep in? (“His underpants?”—the very word, spoken by my grandmothers, caused my cheeks to leap into flame.) How will he wash his teeth? (With toothpaste spread on a cloth wrapped around an index finger.) What will he read? (The big Doré edition of the English Bible? Surely not yet the leather-bound Balzac that had belonged to Huffy’s mother, Rosa …) Who would return me to the canyon was never a concern, since everyone knew the answer to that: aunt would drive nephew back up the hill following Morning Time the next day.

The invitation came soon after we had returned from our antiquing excursion that afternoon, when Huffy realized that Sylvia was out for the evening, at one of her concerts downtown. “We’ll keep each other company tonight,” she said to me. Auntie Hankie made sure that there was enough food in the house for dinner and then headed home.

After she left, Huffy said, “How about if we just have two large bowls of ice cream and then get into bed and read?”

“Is there chocolate sauce?”

She laughed. “There can be.”

When we finished our “dinner,” Huffy said, “I have something for you. I bought it for you last week.”

She went into her room and then returned with a small package in a brown paper bag. Inside there was a blank book bound in orange leather. Its paper was ruled, and it closed with a tiny brass lock and key. On the cover, embossed in gold, was a single word: Diary.

“I keep one,” she said. “I have since I was a young woman in Portland. When you’re older you’ll read it. You and your brothers. You’ll be able to know me in a way that you cannot possibly now.” She looked at me. “That doesn’t make much sense to you, does it?”

I shook my head.

“You’re old enough to begin writing about your own life.”

“Write?” I asked, confused. “What kinds of things?”

“You can write about the world you’ve been born into. It’s always interesting, no matter when you are born into it. And you can put down a record of who you are to yourself.”

Who. You. Are. To. Yourself. These words meant nothing to me.

“And what the people around you are like.”

This I understood better. Or was beginning to understand better.

Grandma Huffy often gave me guidance like this. They weren’t rules exactly; they were more like principles to live by, sized down and age-appropriate—most of the time.

During the long, tedious, full-out Haggadah Seder at our cousins’ house in the deep Valley, for instance, after every few prayers she would whisper, “Spirituality has nothing to do with this excruciating tedium, remember that.”

If we were in a shop and she picked up an object and saw the words Made in Germany stamped on the bottom, she would set it down with a decisive thud and declare, “Never as long as I live—or you do either.”

“You must always be a Democrat,” she said to me one day. “In this family that is what we are.”

In this case there was no explanation—only the edict.

She told me stories too, some of which I could not stop replaying over and over in my head, like the one about the painting or Aunt Baby.

We were driving in her blue Oldsmobile one afternoon when I had asked her where Aunt Baby got her nickname. “It’s very simple. She’s the baby of the family.”

“But she’s not your baby”—even I grasped that much already.

“No, she’s not. But that doesn’t make any difference to me. To me she is another of my children. Would you like to hear how she came to live with us?”

I nodded.

“Her mother died when she was a small girl. Her father was a friend of your grandfather Sam’s from Portland,” she began, saying the name of her dead husband, my grandfather, for the first and, I believe, only time in the whole ten years I knew her. (There were no photographs of him standing on the top of her dresser, no sign of his existence anywhere at all in The Apartment.) “He was a decent man, but he was an alcoholic. An alcoholic is someone who cannot stop himself from drinking, and when he drinks is not, shall we say, at his most worthy. A father who drinks like that is not a good father. He cannot be. It is not possible. I saw this, and it disturbed me. Deeply. So one summer I invited Baby to come stay with us. She was thirteen, and she had a wonderful time. Your aunt was like a sister to her, your father a brother.”

She paused. “At the end of the summer I took her for a walk. Just the two of us alone. And I said to her, ‘Baby, I would like to make you an offer. But I want you to know first that my feelings will not be hurt if you say no to me. Do you understand?’ And she let me know she understood that, which was important. Then I said, ‘I would like to invite you to come live with us here in Los Angeles. To make your home with us for good. I want you to think it over, and let me know when you have.’”

“And what did she say?”

“She said she did not need to think it over for even one minute. She wanted to stay with us forever. Which, until she was married, she did.”

Looking through the windshield, she said, “It’s important to be able to decide matters for yourself sometimes. Even when you are still a child.”

She saw that as the point of the story. I saw something else: a child entrusted to parents who were not her own, as I was so often entrusted to my uncle and my aunt.

Precisely an hour after we climbed into our beds with our books, my grandmother announced that it was time for us to sleep. She turned off her light, and I obediently turned off mine. Then she arranged her pillows, centering herself between the bedposts with the leaping flames, and within minutes was definitively, snufflingly, out. I, instead, took what felt like hours to find a way to put myself to sleep. Everything in The Apartment was just so humming and unfamiliar and alive, from the bursts of traffic up on Hollywood Boulevard to the sound of Sylvia, who had returned from her concert, puttering busily (once Huffy’s light went off, she began walking from room to room), to the rumblings that originated from deep in my grandmother’s chest and didn’t seem able to decide whether they should come out through her mouth or nose. Every now and then there would be a raspy explosion, half snore and half shout, that would send me flying down under the blankets; I came up again afterward even more awake, with nothing to keep me company other than the wallpaper, whose embossed wreaths and urns I traced with my finger over and over and over. When that didn’t help I returned to Doré’s terrifying renditions of Adam, Moses, Jonah, et al., which were even more alarming when examined, squinting, in the dark of the night, or else I studied the bust of Madame de Sévigné that stood up on an onyx column and had been chosen, my aunt said, because she adored her daughter and wrote some of the most memorable letters in all of literature. In front of the bust a small, armless rocking chair moved back and forth on its own, very slightly, as if it were being rocked by a ghost.

And then suddenly, somehow, it was morning, a day awash with eyeball-stinging Southern California sunlight, and Sylvia was bringing me a glass of hand-squeezed orange juice strained of its pulp, which, wasting nothing, she herself ate with a teaspoon. “Drink, Michaelah,” she said. “Good health is built on vitamin C. Every day a dose.”

Huffy was already up and dressed, a rarity and something that happened only on the days I slept over, since normally she waited in bed, reading, until my aunt came for Morning Time.

After I finished the orange juice, Sylvia asked if I’d like to help make the bed. “I can show you how to miter the corners the way they do in a hospital,” she said.

A bed with hospital corners? It sounded exciting, a nifty trick, something to be good at. I loved tricks and I loved learning. I got up eagerly.

First we angled the mattress frame slightly away from the wall. Then we pulled up the crisp white sheet and the blanket. She lifted up the mattress, folded one sandwich of sheet and blanket underneath, held it there firmly, then reached around for the other flap.

“It’s like wrapping a package,” I said.

“Yes, exactly,” she said with a smile.

Suddenly from the doorway a sharp voice: “But whatever are you doing?”

Sylvia stiffened. “Teaching him how to make a bed with hospital corners,” she explained.

“Oh, please, the boy is never going to need to know how to do anything remotely like that.”

Sylvia, her shoulders deflating, abandoned the bed-making where it was and hurried off to the kitchen.

I was still holding the edge of the blanket. I watched her go, paralyzed. Even though Sylvia was walking away from me, I could feel the upset pouring out of her whole body. I turned to look at Huffy’s face to see if there was any clue there, any hint that she knew what she had done. There was nothing.

“Leave that nonsense and go get dressed now,” Huffy commanded. “It’s time for breakfast.”

In the bathroom the washcloth was already prepared with toothpaste, the face soap smelled of gardenias, and there was a thick, soft towel to dry myself with afterward. I put on the clothes I had worn the day before, and then I opened the door and stopped to listen. I often stopped to listen before I left one room and walked into another.

I could hear the sounds of utensils touching metal, then glass. I approached the kitchen door. My grandmothers were not speaking to each other, but they were cooking. They were standing at the same stove, working over separate burners. In silence each was preparing her own version of the same dish for me to eat, a thin crepe-like pancake. Sylvia was making hers, ostensibly, as the wrappers for the cheese blintzes that were one of her specialties: light, fluffy rolls of sweetened hoop cheese wrapped in these nearly translucent covers. Her pancake barely rubbed up against the pan; she siphoned one off for me and served it with strawberry jam and a dollop of sour cream. Huffy’s was browned and glistening from its immersion in a puddle of butter and offered with a tiny pitcher of golden maple syrup.

Two plates, two pancakes, two women waiting expectantly for my verdict: What was a child to do with all this—choose? Declare one tastier than the other, one woman more capable, more lovable, more loved? All I could think to do was eat both, completely, alternating bite by bite between the two versions.

“Are you still hungry?” Huffy asked slyly when I finished.

How did I know not to give myself to the trap? From looking at Sylvia’s face, with its well-proportioned nose, small and round and with a spiderweb of wrinkles in-filling around it; and its too-perfect front teeth, which were dropped into a glass of blue effervescence at night, leaving behind a silent, sunk-in mouth; and its faded watchful eyes, which so vividly showed a registry of pain.

“I’m done,” I said. “But thank you. They were both delicious.”

Before she dropped me at home after Morning Time, my aunt pulled over to the side of Lookout Mountain Avenue.

“There’s something I wish to say to you, Mike,” she declared ominously, or in a way that sounded ominous to me.

I thought I had done something wrong during my stay at The Apartment, something worse than drawing ineptly or being receptive to the idea of Sylvia teaching me how to make hospital corners.

She removed her dark glasses. “I just want to thank you for being such a good friend to Mamma.” She took my hand and squeezed it forcefully.

“Your visits lift her spirits in countless ways,” she continued. “You know what I wish? I wish it could just be the three of us forever, living far away, on an island somewhere, or in Yurp …”

The three of us? On an island? In Europe? I wasn’t quite sure what my aunt was saying, but just as confusing, even more so, was the way she was saying it, with an odd lilting voice and a far-off look in her eyes.

“You mean … without my parents and Danny and Steve? Without Uncle Irving or Grandma Sylvia?”

“The four of us, I should have said. Puddy and I are symbiotic. I’ve told you that before.” She paused. “Sylvia,” she said her name, only her name. It was followed by a dismissive shrug. A whole human being dispatched, just like that.

She did not say anything about my brothers or my parents. The air in the car suddenly felt humid, the Caswell-Massey suffocatingly sweet.

“I don’t know if you realize what a remarkable woman Grandma Huffy is. She’s the most independent woman I have ever known. A freethinker. It’s her religion, really, the only one she believes in. Free, bold thinking—it’s at the very core of what it means to be a Mighty Frank. Mamma is its perfect embodiment. She thought for herself, she lived on her brains, she followed her heart wherever it took her, even when it took her to unconventional places.”

Unconventional places? My face must have asked the question I would not have dared to put into words.

“It’s never too soon to learn about the ways of the heart. Your grandmother,” she said, turning to face me, “married young and, you might as well know, for the wrong reasons. She was one person at twenty, another at thirty. Portland, Oregon? For Harriet Frank senior? She had been to Reed, to Berkeley. She had brains, and pluck. And ambition, that most of all. But ambition did not get you very far in the Depression, did it? There was nowhere to go. She outgrew that dreary city, she outgrew the shabby little house we lived in, she outgrew your grandfather. He was a decent man, hardworking, moral, I might as well say, blah and blah. He was not in her league, not intellectually, not emotionally. And so she took it upon herself to find love elsewhere …”

Again she glanced at my face. “Don’t be so conventional, Mike.” Her eyes began to glitter. “I was not much older than you are when I guessed. He was the rabbi at our temple. It started there, the opening up of her life. With Henry. Why, I was half, more than half, in love with him myself, in the way you can be when you are twelve and a charismatic man comes along who is everything that your father is not …”

I tried to picture my grandmother with a man other than my grandfather. And a rabbi. The rabbi at their temple. There seemed to be rabbis everywhere in this family, yet we rarely went to synagogue. But a rabbi with whom my grandmother found love elsewhere? What did that mean, exactly?

I did not, at that point, know the specifics of what it was that a man and a woman did with each other, aside from raise children. Or yearn for the children they did not have.

My aunt emitted a long sigh, then started the car again. “These talks of ours make me feel so much better. You help me in countless ways, Lovey. I wonder if you realize that?”

She adjusted her head scarf, then leaned over. “Of course what we say to each other stays between thee and me, understood?”

When I didn’t immediately answer she said, “Mike?”

I nodded. She nodded back at me conspiratorially. Then she pulled the Riviera away from the curb.

At Greenvalley Road she lowered her cheek for me to kiss goodbye. I collected my treasures and waited until she backed out of our driveway. Then I made my way along the curved walkway that led to our front door.

That spring my mother had planted white daisies on the uphill side of this path, and they had grown into thick bushes that gave off a strong spicy scent when I brushed by them. The daisies were notable because they were lush and perfumed but also because they were one of the few independent domestic gestures my mother had made in her own house and garden, the decoration and landscaping having been otherwise commandeered by my grandmother and my aunt.

The style of our house—a white clapboard Cape Cod—my parents had chosen jointly. My father contracted and supervised the construction of the house himself while my mother was pregnant with my next-youngest brother, Danny, but that seemed to have been the last independent decision my parents made with regard to their own surroundings.

Very American, my aunt said in that assessing voice of hers. At least it’s not mo-derne. Traditional we can work with.

“We,” naturally, were the two Harriets, who had submitted our garden to a rigorous Gallic symmetry: two pairs of ball-shaped topiary trees flanked the two front windows and were separated by a low boxwood hedge that was kept crisply clipped on my aunt’s instructions to the gardener shared by both families. The front door was framed by stone urns, and the central flowerbed was anchored with a matching gray stone cherub because every garden needs a classic figure to set the atmosphere just so. Most of the flowers, those daisies included, were white.

Inside the house almost all the furniture and pictures had been chosen by my grandmother and my aunt, who had sent over containers from Yurp or otherwise outfitted the rooms with discoveries made during their Saturday excursions or castoffs from their own homes. The furniture was arranged in the rigid, formal groupings my aunt favored. She and my grandmother would often come over at the end of their Saturdays, and even, maybe especially, if my mother wasn’t home they would introduce a new table or print or vase, readjust or rearrange several other pieces, and sometimes rehang the pictures, with the result that our house looked like a somewhat sparser cross between my grandmother’s apartment and my aunt’s house.

My mother, while raising three young boys and at the same time helping to take care of her mother, did not have so much time for interior decoration. In these early years she appeared to tolerate these ferpitzings of her in-laws. Sometimes she would walk in and say, opaquely, “Ah, I see they’ve been here again”; sometimes she was so busy that it took her a day or two to notice that there had been a change. I was not like her. I noticed the most minute shift in any interior anywhere.

Upstairs alone in the quiet of my room I took special pleasure in unwrapping my new treasures. It was like receiving them all over again. Methodically I laid out on my desk my new art book, my pencil box and bookends, the copy of How Green Was My Valley that my aunt decided, after all, might be a better choice for me to borrow from my grandmother’s library, and the set of colored pencils that she stopped to buy me at an art supply store on our way up the hill that morning, since mine, she had noted critically, were used practically down to the nub.

I put the diary that Grandma Huffy gave me in the drawer of the table by my bed and soon became so absorbed in Famous Paintings, which was my favorite of all the gifts my aunt gave me that weekend, that I was unaware of the door to my room cracking open to allow eyes, two sets of them—my brothers’ two sets—to observe me.

The door cracked, then creaked. I looked up. It opened wider, and first Danny, then Steve, stepped in.

The three of us were graduated in size. I was the tallest and, in these years before adolescence hit, had thick, silky hair that I had recently begun wearing longer over my ears. I had a version of my aunt’s botched nose, though I had been born with mine, which angled off slightly to the left; my eyes were green and often, even then, set within dark black circles that my mother said I had inherited from her father, my rabbi grandfather, but my aunt said were a sign of having an active, curious mind that was difficult to slow down even in sleep. Danny came next in line. His hair, also longer now, had a reddish tinge, and his face looked as if someone had taken an enormous pepper shaker and sprinkled freckles across it. His eyes were not circled in black; instead they went in and out of focus, as if he were intermittently listening to some piece of private music or following a conversation that he had no intention of sharing with anyone, ever. Steve was the “little one”; compact, wiry, athletic (as my aunt often said), he had a sly sense of humor and agate-like gray-green eyes that, even from the doorway, took rapid inventory of the new things on my desk.

“What’re you doing, Mike?” asked Danny.

“Reading,” I said.

“Is that book new?”

I nodded. “It’s a book about art.”

He approached my desk. Steve followed.

“You went to a bookstore without me?” Danny loved bookstores. The books he loved were simply different from the ones I loved. The ones my aunt and uncle and I loved.

I shook my head. “It’s something Auntie Hankie bought for me.”

He shrugged, too casually. “What’s that one?”

“I’m borrowing it from Grandma’s house. It’s a novel. Auntie Hankie read it when she was about my age. It’s for grown-up kids,” I added.

“You’re a grown-up kid?”

When I didn’t answer, Danny moved closer.

“I read novels too, you know.”

“You read science fiction. That’s different.”

“It’s still made-up. It’s still a story,” Danny said.

He picked up the pencil box and asked what it was for. I explained its purpose. I used the words artist, tool of an artist. Patina. Fragile. I said it wasn’t anything he would be interested in. He was the scientist in the family, I reminded him.

The phrase was so expertly parroted I didn’t realize I hadn’t thought it up by myself.

Steve reached over and picked up the box Danny had put down.

“Be careful,” I told him as he opened and closed the lid. “It’s old. It’s not a toy.”

The hinges on the pencil box were fragile. The lid snapped off.

“Sorry,” Steve said. “I didn’t mean to.”

“Sure you didn’t,” I said impatiently.

“I just wanted to see what was inside.”

“I’ll fix it,” I said, grabbing it away from him.

There was another set of eyes at the door now. My mother’s. She took in the scene as much through her pores as through her eyes.

She came in and made her own inventory. Then she looked out the window at the fold of canyon that enclosed our house in a green and brown ravine. The sky overhead was bright and nearly leached of all its color.

“Boys,” she said to my brothers more than to me, “I’ve told you before, I know I have, that things aren’t always equal, with siblings. They can’t be.”

She might not have always looked so carefully at the rest of our house, but in my room just then she was tracking sharply.

“Sometimes it might feel like it’s more unequal than others, but …”

The books, the bookends. The now-damaged pencil box. The pencils. The paper wrapping and bags left from the day’s loot in a hillock on the floor.

“But it all evens out in the end,” she said without much conviction. Without, from what I could tell, much accuracy either.

I found her later in the kitchen before dinner. She was pricking potatoes before putting them into the oven to bake—stabbing them was more accurate.

At dusk, when the lights were on in our kitchen, the window over the sink turned into a mirror. Our eyes met there.

“It’s not my fault if Auntie Hankie likes to buy me things,” I said.

My mother did not turn around to face me. She spoke to the window instead. “I know that,” she said.

She put the potatoes in the oven.

“Or tells me things …”

She closed the oven door. She turned to face me. “What kinds of things?”

I felt my skin redden. But I had started, so I had to finish. Or try to finish. So I repeated to her, as best I could, as best I understood, what my aunt had told me about my grandparents and their marriage.

I felt so … weighted down after that moment in the car. Telling my mother was like taking a huge rock out of my pocket.

My mother’s eyebrows drew close together. “Your aunt is a screenwriter. A dramatist. She is always making up things, making them more—”

“But is it true, what she said?”

With some difficulty my mother regained control of her face. “Not everyone—not every marriage—is like every other,” she said cautiously.

“So it is true, then.”

Her intake of breath made a wheezing sound. “Yes,” she said. “Your grandparents were not—happy together. But there’s no reason for a child to know anything about all that. I don’t know what your aunt was thinking. Really it’s best put out of your mind, Mike. It’s a story for later on.”

My father was a large man, and as different from my uncle as my mother was from my aunt. He had a version of his mother’s forceful, emphatic features, though he was darker and physically more powerful. A former high school football player, he skied and played tennis. He did everything hard. He worked hard at his own medical equipment business. He played sports hard. He chewed his food hard. He trod the stairs with a hard, loud step. When he became ill, which was rare, he became ill hard, spiking outrageous fevers or coming down with stomach bugs that would have landed other men in the hospital. He pruned trees and painted the house hard; he even washed cars hard.

My uncle was softer in every sense. He was brainy, bookish, and gentle. Curious, endlessly curious, about us children. He spoke quietly and with dry humor. He never raised his voice, at least to us, which distinguished him dramatically from my father, who had a terrific, terrifying temper. The Bergman Temper, my mother called it. In our family my father’s temper was assumed to be as elemental, and as unpredictable, as a winter storm. And as natural: he inherited it from his mother; he shared it with his sister and older brother. His rages came on suddenly and were loud and fierce; when he got going there was no reaching him, not ever. “It’s in his genes,” my mother said, trying to explain away what she was powerless to change.

Many different things could set my father off. A dropped egg in the kitchen while he was cooking. An unruly child and (later) an adolescent who gave lip. Traffic. A traffic ticket. Republicans. Criminals. A scratch on the car. A minor loss at gin.

His wife, naturally. My mother. Who now and then, even in these early days, when she was still the good girl, would introduce a dissenting point of view, a request. That morning, a concern.

“It’s breaking my heart, Marty, to see them treated so differently …”

These weren’t the words that started their argument. They came along somewhere in the middle, after my brothers and I were already listening in.

It started when my father returned from his Sunday tennis game. He was in the kitchen, preparing breakfast. Nothing unusual there. My mother joined him. Not so unusual either. She was always going back downstairs for more coffee. More and more coffee.

What was unusual were the voices, raised so suddenly and to such a decibel that they came up through the floorboards. I was poring over Famous Paintings in my room, my hard-won room of my own, which about a year earlier I had convinced my parents to let me have, arguing that with my reading and drawing and my interest in the visual, and being after all the eldest, it only made sense.

My brothers were in their shared room next door. We came to our respective doorways at the same moment. We looked at one another and then together, in silent agreement, we slipped down the stairs, which were open to the entry hall, which was open to the dining room, which led to the kitchen …

“She’s your sister. You need to speak to her.”

“He’s your brother. Why don’t you speak to him? Go ahead, damn it.”

“She’s the one driving. You know that. She’s the one taking him out nearly every week now, buying him things, never thinking of the other boys. It’s as though they don’t exist. You should have seen their faces. It doesn’t matter what she buys him—the mere fact of it, week after week. It’s breaking my heart, Marty.”

“There is no reaching Hank. You know that.”

There was a pause.

“She told him about your mother and her … exploits. He’s nine years old, for God’s sake. Nine!”

My father was silent.

“You have nothing to say to that?”

“There’s no reaching Hank,” he repeated.

“You don’t try hard enough!”

“I do try! I have tried!”

“Not forcefully enough.”

“I can’t make her do anything. You know her as well as I do. You can’t make that woman—”

“I think you’re afraid to stand up to her. I think you’re afraid, period, of your own sis—”

Loud at his end. High-pitched at hers. I did not need to see my father to know that his nostrils were flaring, his head shaking, as from a tremor.

Our parents had fought before, but not like this. Usually it was in their bedroom, with music on—and turned high. That was our mother’s trick. Crank up the Mamas and the Papas, the children won’t hear. Or they won’t understand if they do.

The children heard. They understood. Their voices, the content. Next: objects. A spatula—a spoon? Had he thrown something? At her? We heard it clattering to the ground.

“I cannot live with this kind of frustration—”

Then we heard a fist, our father’s fist, coming down. Hard. On what? We could not see. Not our mother. Something solid. It sounded like wood.

This sound was followed by another sound: something breaking, then falling to the ground.

There was a pause. A silence. As if even he was surprised at what he had done.

He had banged his fist on the kitchen table. Being an antique—with patina, a story, a treasure brought over from Yurp, all that—it had split in two (we saw the disjointed pieces later, lying there on the floor), scarring the wall as it went down.

“Marty, my God—”

“Don’t you dare—”

“Don’t you say ‘Don’t you dare’—”

My brothers looked at me, the oldest, to do something.

“I’m scared,” whispered Steve.

“So am I,” whispered Danny.

“Get your shoes,” I whispered back. “Come on.”

I could leave a house as stealthily as I could enter it, even with my little brothers following—tiptoeing—down the stairs and out through the glass door in the guest room, then around through the backyard, down the ivy slope, and onto the street.

On the street I noticed that Steve’s shoe was not properly tied. I bent down and knotted it. Double knotted it.

“Is Dad going to hurt Mom?” he asked.

He never had before. He tended to hurt objects, feelings, souls—not people.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I can’t be sure.”

“Where are we going?” Steve asked.

Geographically, Wonderland Park Avenue was a continuation of Greenvalley Road, the reverse side of a loop that wound around the hill the way a string did on its spool; only where Greenvalley was open and sunbaked, Wonderland Park was shady, hidden, mysterious, and at one particular address simply magical. Halfway down the block on the right and bordered by a long row of cypress trees, number 8930 was a formal, symmetrically planned, pale gray stucco house that stood high above its garden (also formal of course, with clipped topiaries and white flowers exclusively) and was so markedly different from all its neighbors that it looked like it had been picked up in Paris and dropped down in Laurel Canyon.

Everything about the house evoked another place, another time, a special sensibility; my aunt’s special sensibility. The curtains in the windows, edged in a brown-and-white Greek meander trim and tied back just so … the crystal chandeliers that even by day winked through the glass and were reflected in tall gilded mirrors … the iron urns out of which English ivy spilled elegantly downward … the eight semicircular steps that drew you up, up, up to the front doors. The doors themselves: tall and made to look like French boiserie, they were punctuated with two brass knobs the size of grapefruit that were so bright and gleaming they seemed to be lit from within.

I led my brothers up the steps and to these doors. Even the doors had their own distinct fragrance, as if they had absorbed and mingled years’ worth of potpourri, bayberry candles, and butcher’s wax and emitted this brew as a kind of prologue to the rooms inside.

I rang the bell. We waited and waited. When I heard the gradually thickening sound of footsteps crossing the long hall (black-and-white checkerboard marble set, always, on the diagonal), I began to feel uneasy for having brought my brothers here, at this time of all times. But where else were we to go?

There was a pause as whoever it was stopped to look, I imagined, through the peephole. Then the left-hand door opened. My aunt, seeing us there, at first lit up. “My darlings, what a surprise.”

It took her a moment to realize that Steve was still in his pajamas. Then she looked, really looked, at our faces. “But what’s wrong?”

“Mom and Dad are having a fight, a terrible, terrible fight,” Danny said, his lower lip turning to Jell-O.

She called back over her shoulder, “Irving—come, come quick.”

Then she knelt down and drew my younger brothers into her arms. “Not to worry, darlings. Everything will be all right.”

Those eyes of hers. Two lanterns, set on high cheekbones. Wicks untrimmed and flaming.

Auntie Hankie sat us down in the kitchen and insisted on making us hot chocolate, even though it was already pushing eighty degrees. She found cookies in a tin too, and brought in from the living room our beloved jar of foil-covered chocolate Easter eggs, which she kept there to entice us all year long.

She brought us a deck of cards, a jar of coins from her recent European travels. My uncle rustled up some pencils and some shirt cardboards to draw on.

Then she sat down with us. “Now tell me. Tell us both.”

My brothers looked at each other, then at me.

“Mom and Dad were fighting,” I said.

“Yes, you said. But what about?”

My brothers looked at each other, then into their laps.

I felt my face burning. “I don’t know. We were upstairs. It was loud.”

“Very loud,” Danny said.

“So loud,” she asked, “that you couldn’t hear what they were talking about?”

My brothers shook their heads. My aunt looked at me, but I didn’t say anything.

“I know this may be hard for you to understand,” she said, “but everyone fights sometimes—even mothers and fathers.”

“Your aunt and I fight, sometimes,” said my uncle.

“Puddy, we do not. We’ve never had a cross word in our lives.”

“Well, not this week,” my uncle said drily.

“Not any week that I know of,” she said tartly.

My uncle emitted one of his trademark six-step sighs, a cascade of diminishing breaths that generally alerted us to his not-quite-silent dissent.

“It’ll blow over, children,” he said. “These things always do.”

Steve said, “Dad has the Bergman Temper.”

My aunt stiffened as she said, “The Bergman Temper? Now what would that be, exactly?”

The sharpness in her voice caused Steve’s eyes to return to his lap.

“Do you even know who the Bergmans are—were?”

“Grandma is a Bergman,” he said. “And Dad. You are and I am too.” He looked up. “It’s my middle name,” he added.

“Yes, that’s right, partially right,” she said. “The Bergmans were Huffy’s people,” she added. And then she waited.

When none of us said anything further, she continued, “Well, your father is passionate about things, the way I am. And Mamma too. If it’s passion you mean, I’ll concede that, yes, it runs in our side of the family. It always has.” She paused. “I’m just curious. That term, the ‘Bergman Temper.’ Who came up with it?”

Both my brothers looked at me. My stomach tightened.

“Was it your mother, by chance?”

“No,” I lied. My skin, giving away my lie, began to burn red.

My aunt nodded, not to us, or to herself, so much as to some invisible off-screen observer or camera. She often did that: she pretended, or maybe assumed, that there was an audience following her—tracking her—at all times. She did not say, I know perfectly well that it was your mother. I do honestly believe that woman sometimes hates us, me and Mamma both. She did not need to say this, at least to me. I knew what she was thinking, and because I knew, or believed I knew, I began to feel uneasy all over again for having brought my brothers here. But I was scared. My father had never smashed a piece of furniture in anger before.

“We should probably call over there,” said my uncle. “They’ll be concerned.”

“Oh, I’ll take care of that,” my aunt said to my uncle. The lift in her voice told me that the prospect of making that call did not displease her.

My uncle emitted another one of his sighs. He said, “Maybe it would be a better idea if I—”

But she was already on her feet. “I’ll just be a minute,” she said, heading into the study so that we couldn’t hear.

Ten minutes later, the doorbell rang. Its sound was amplified by all that marble.

My aunt hurried off to answer the door. We could hear murmuring from the hall—hers and his, sister’s and brother’s, back and forth. Then quiet. Then footsteps. Loud footsteps, familiar footsteps. My father’s loud, familiar footsteps.

He was still in his tennis clothes. His shirt was damp with sweat. With anger. One of his shoelaces had come untied, like Steve’s had earlier.

“Let’s go, boys,” he said.

Our father was no longer angry. He was steely and quiet. This was new. New to me, anyway. And almost worse.

He asked Danny and Steve to go into the house ahead of me. We sat in the car in the garage: his space with his vehicles, his tools and tool bench, his disorder. His scent: no bayberry or potpourri here; instead grease, car oil, rubbing compound, sweat. It stank.

He sat for a minute, several minutes, in silence, with the motor turned off and the keys dangling in the ignition. The car engine produced sigh-like, crackling sounds as it cooled down.

I thought my heart would punch a hole in my chest.

“Never do that again, Mike,” he said finally. “Not ever.”

His voice was firm, deep, forceful. Steady.

“I—I was scared,” I said, scared all over again. “So were they. Danny and Steve.”

“I have the Bergman Temper. You know that. I inherited it from my mother. But it blows over, and when it blows over, it’s over.”

“You broke something.”

“The kitchen table,” he said. “I’ll glue it back.”

There was no apology. Only facts.

We thought you might hurt Mom, I did not say. I did not say, We’re all scared of you. We hate your temper. It makes us hate you, sometimes. It makes us feel unsafe and it makes us—me—want to be with Auntie Hankie and Uncle Irving.

“You’re old enough to know better, Mike. You’re old enough to know what stays in this family, our family. Our part of the rest of the family.”

He looked at me. His voice may have been level, but his eyes expressed something unnerving: his temper under control.

“You understand, don’t you, that it was wrong—very wrong—to take this to your aunt and uncle’s?”

I nodded.

“Very, very wrong,” he said. “You must promise me that you will never do anything like that ever again.”