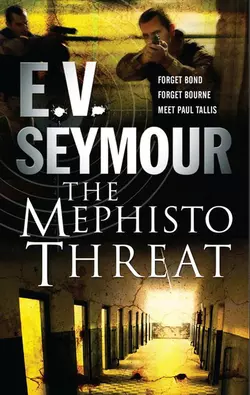

The Mephisto Threat

The Mephisto Threat

E.V. Seymour

Ex-army. Ex-police. Unofficial MI5 spook.

Meet Paul Tallis ; a spy for the 21st centuryIn Istanbul, journalist Garry Morello is executed in cold blood. Moments before his death, he meets with old friend Paul Tallis, hinting that he has uncovered a link between international terrorism and organised crime back home.

On the run from the Turkish authorities, Tallis makes his way back to London and passes the intel to his MI5 handler. Sent undercover in Birmingham to investigate the threat, Tallis's mission is to infiltrate the inner circle of crime boss Johnny Kennedy.

Once inside, Tallis must determine if the charismatic gangster is involved in planning the biggest terrorist attack on Britain ; or if his MI5 paymasters are the ones he should be watching.

For fans of ROBERT LUDLUM, GERALD SEYMOUR and JOHN LE CARR, this is a must read.

Also available by E.V. Seymour

THE LAST EXILE

THE

MEPHISTO

THREAT

by

E. V. Seymour

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk/)

For Bex, Milly, Katy, Olly and Tim

My Famous Five

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I couldn’t have written this book without the generous help of others. It’s been a long time since I last visited Turkey so I’d like to thank Brian and Margaret Fox for bringing me up to date and for giving me such a personal insight into a country they clearly love. Special thanks also to Keeley Gartland, Media and Communications West Midlands Police, and to Detective Sergeant Maria Cook who shared her knowledge of the workings of the Organised Crime Division. It must be stated that the opinions and attitudes expressed in the story are my take and not a reflection of the views expressed by the officers with whom I spoke.

Selwyn Raab’s excellent book, Five Families, provided the starting point for the novel. For inside knowledge of gangs and organised crime, I highly recommend all books written by Tony Thompson on the subject. Likewise, Peter Jenkins’s book on Advanced Surveillance helped to give Tallis the edge in a number of tricky situations.

I’m not sure I’d have been able to write about Billy’s injuries had it not been for my visits to the Acquired Brain Injury Education Service, Evesham College. The staff and clients there are truly inspiring, and big thanks to all for making me feel so welcome.

Lastly and by no means least, thanks to my agent, Broo Doherty, and to Catherine Burke and the team at MIRA. I couldn’t have done this without you.

1

HEAT was killing him. Blades of light skewered his skin. Without air, the soaring temperature suffocated, halting time and muffling his senses so that he couldn’t focus on the narrow streets, sprawling stalls and brightly coloured bougainvillaea, couldn’t smell the spice and fenugreek, honey and dried beef, couldn’t taste his apple tea or hear the blare of car horns signalling another mad couple’s leap into matrimony. In all of his thirty-three years Tallis had never known weather like it, not even when he’d fought in the first Gulf War. It was as if the whole of Istanbul was being microwaved.

He changed position, slowly, lethargically. He would have preferred a café nearer to the university. Students were always attracted to the best hangouts, but Garry had insisted they meet close to the Spice Bazaar, or Misir Carsisi, to give it its Turkish name, a cavernous, L-shaped market within sight of the New Mosque. He didn’t know the reason for Garry’s choice of venue, or whether it held significance.

Tallis reran the conversation he’d had with Morello at the airport. They’d literally bumped into each other, a surprise for both of them.

‘Fuck me, Paul, what are you doing here?’

‘Could ask you the same question.’

Garry tapped the side of his nose. ‘Work.’

Tallis copied his friend, taking the piss. ‘Holiday.’

‘Lucky sod.’ Oh, if only you knew, Tallis thought. ‘How long for?’

‘Three weeks, maybe more.’

‘Good. I’ll be back from the UK by then. Actually,’ Garry said, ‘there’s something I’d like to bounce off you, something I’m following up.’

‘I’m a bit out of the game, man.’

‘Once a cop always a cop.’ Tallis flashed a smile. Garry had no idea that, since he’d left West Midlands police, he’d become involved in working for the Security Services. Oblivious, Garry returned the smile then his look turned shifty. ‘I’ll explain more next time we meet. Give me your number and I’ll give you a call soon as I’m back in Istanbul.’

Tallis had hesitated, felt tempted to give him the brushoff. He was working undercover and off the books for MI5. Asim, his contact, had been privy to a limited amount of chatter, which he wanted Tallis to verify. There was no huge expectation because the word on the ground was embryonic, no specific threats, no timing, no hard targets, but there remained a major fear that terrorist organisations were dreaming up a new kind of campaign, involving different methods of destruction, different tiers of people, hinting at an involvement with British organised crime. In among the white noise, the city of Birmingham was hinted at. A meeting with Garry could horribly complicate things but, apart from the insistence in Garry’s manner, he owed the man.

As a freelance crime correspondent, Morello had covered the botched firearms incident in Birmingham for which Tallis, then a member of an elite, undercover firearms team, felt responsibility, even though he had officially been cleared. Unlike many, Morello wrote a balanced account, sympathetic almost, along the lines of a firearms officer’s job was not a happy one. Tallis had phoned him afterwards to thank him and they’d hit it off. He’d stayed in touch ever since, even having several dinners with him and Morello’s wife, Gayle, at their home in Notting Hill. When Garry was in Birmingham, he made a point of calling Tallis so they could hook up. Friends like that were hard to come by so, in spite of the risk, Tallis had given Garry his new mobile number with a smile. And Garry had got in touch.

Tallis adjusted his sunglasses. He was looking and listening, his senses attuned for anything out of kilter. He’d already closely considered his surroundings: five tables arranged outside on what passed for a pavement, all of them occupied, one by a group of middle-aged Turks smoking and playing backgammon, another by a young British couple. Some dodgy-looking Russians were eating mezes to his left. The furthest table away was taken by a single male, early thirties, nationality unidentifiable. For some time he’d been mucking about with a mobile phone. As Tallis glanced at him the man smiled with hooded eyes, black, same colour as prunes, then put away the phone and turned to his Newsweek.

Tallis continued to sip his tea, a beverage more suited to regulating body temperature than beer. Not that he was drinking alcohol—unprofessional to consume booze on the job.

He looked out onto a street crackling with latent heat, sky a screaming shade of blue. There was a small commotion as a street trader ambling past, his cart filled with plump bulbs of garlic, narrowly missed a taxi, the moustachioed cab driver displaying his displeasure by placing his hand flat on the horn and gesticulating wildly. Tallis smiled. When it came to driving in Turkey, you took your life in your own hands, the high road accident rate evidence that it was never wise to assume right of way. Just one of those many little things he’d discovered in the short time spent travelling in this strange, beguiling nation, a magical blend of ancient and modern, fast-paced and fast-changing and full of contradictions.

Take its government, Tallis thought. It desperately wanted to be accepted into the European Union but did the very things that made it unacceptable; it was an open secret that Turkey’s human rights record continued to raise concern. By the same token, its people were friendly, generous and full of good humour. Especially the blokes. When a Turk declared himself your friend, an arkadas, he genuinely meant it, and it amused Tallis that while every Turk honoured the female of the species, every Turk also reckoned himself irresistible to women. While fathers could allow their daughters to enjoy certain freedoms, many saw no contradiction in offering them for sale, particularly to well-heeled Englishmen.

But this was all extraneous stuff, Tallis reminded himself. His brief concerned the criminal and political. Turkey might be a secular society, but there was enough pull from a variety of religious quarters to make it extremely vulnerable to conflict—that and its geographical position. Lying midway between Europe, Asia and the Middle East, the country was a gateway, a melting pot for culture and ideas on the one hand, terrorists and organised crime on the other. No accident that many unsuspecting girls were trafficked through its borders. More worrying still the significant trend for criminal organisations specialising in arms smuggling and extortion, with all their consequent violent sidelines, to get themselves involved in religious fundamentalism. An explosive mix.

Tallis checked his watch: after noon. Garry was late. He refocused his gaze on the Russian contingent. A popular holiday destination for many Russians, Istanbul was a particular favourite, though Tallis decided from a snatch of overheard conversation that tourism was not uppermost in the Muscovites’ minds. He idly wondered whether these hefty-looking guys with flat, sawn-off features were Mafiya, a breed who favoured no room for error killing—cut throats, crushed lungs and bashed-in skulls. Job done.

‘Paul, good to see you,’ Garry Morello said, slumping down in the chair next to him. A heavyset man with dark features that spoke of Italian blood, he took out a handkerchief and mopped his profusely sweating brow. ‘Christ, this heat is insane.’

Tallis agreed. For the past hour, perspiration had been consistently leaking from his hairline and plastering his short dark hair to his brow.

‘Good holiday?’ Garry said.

‘Most enjoyable.’ After bumping into Garry at Dalaman Airport, he’d travelled by taxi on a blood-pressure-raising journey through the mountains to Fethiye, a working town with a Crusader castle. There he’d treated himself to a Turkish bath, full hot and cold and slapped flesh, and, as a means to build up his cover, joined a gulet, a traditional Turkish wooden sailing vessel. Apart from the four-man crew, there were six others on board—four Brits, two Australians. The destination was Kalkan, originally a fishing village with winding, paved streets, recently transformed into a cosmopolitan marina of sophisticated but unspoilt charm. Apart from swimming and fishing off the boat, he’d spent the first week zombied out in what felt like a narcotic-induced sleep. He guessed it was his body and mind’s way of recovering. He’d experienced something similar after engaging in battle. There was a particular type of lethargy that set in with exhaustion, especially when the fight was so unequal, when your enemy were half-starved boys and old men. But his most recent battle had involved neither guns nor grenades. His battle had been with grief and sorrow. He still felt raw from losing Belle. When it had finally sunk in that he would never see her again, he hadn’t really believed that he’d ever recover.

‘Drink?’ Tallis smiled.

‘Beer, thanks.’

Tallis ordered the locally brewed Efes Pilsen, leant back in his chair, waited for Garry to set the pace. There was a restlessness about him, Tallis thought. The Russians paid their bill and left the table, noisily scraping back the chairs as they went. Tallis briefly wondered if they were the reason Garry had chosen the venue. He inclined his head towards the departing diners. Garry followed his gaze. ‘Mafiya,’ he said neutrally. ‘Wrote a book on the subject last year.’

Yesterday’s news, then, Tallis thought.

The beer arrived. Garry took a long draught then glanced over his shoulder. His expression was uncertain. To help him out, Tallis kept his mouth shut. Most people couldn’t bear silences. Garry was no exception. He craned forward. Tallis wasn’t certain whether it was to block out the din from the neighbouring streets or because he wished to speak in confidence. ‘Know a guy called Kevin Napier?’

‘Not “nearly took out one of his own side” Napier?’ Tallis said dryly.

‘Care to enlighten me?’

‘If we’re talking about the same guy…’

‘Suspect we are. Napier was a tank commander during the first Gulf War and left to join the police same time as you.’

Tallis pushed his sunglasses onto the bridge of his nose. After leaving school at sixteen, he’d joined the army and served with the First Battalion, the Staffordshire Regiment. Eight years later he’d joined West Midlands police.

‘Am I right?’ Garry said.

‘Napier served with the 7th Armoured Brigade.’

Garry flashed him another expectant look.

‘He shot at one of our vehicles by mistake,’ Tallis said, ‘and doused the occupants with machine-gun fire, injuring a couple of British officers.’

‘Not a very smart move.’

‘Proved no obstacle to his career path.’ Tallis shrugged. It had rightly caused an almighty stink at the time, he remembered. The Brits were used to the Americans accidentally firing on them but not one of their own.

‘Did you know he’s with the Serious and Organised Crime Agency?’

Tallis resisted the temptation to react. ‘I’d heard along the grapevine he’d applied.’ So the bastard got in, he thought. Possibly not the smartest move. It was reputed that SOCA, with its high ideal of taking on the Mr Bigs, had fallen rather short of its remit. Experienced officers were leaving in droves either to retire or return to policing. Word on the ground implied SOCA was hamstrung by an unwieldy and top-heavy management system, crammed with analysts, but with no clear brief or expertise in processing data and intelligence. He wondered how Garry knew about Napier. ‘What about him?’

‘I’ll come to that in a moment. Thing is, Birmingham’s your patch, right?’

‘Used to be.’ It was almost two years since he’d worked as a firearms officer. After handing in his notice, he’d temporarily worked as a security guard in a warehouse before being recruited to work off the books for MI5. It hadn’t been one of those ‘apply, endure a host of interviews under the gaze of humourless experts, we’ll get back to you’ type appointments. His was more ‘we want you, we need you, you’ve got the job’ arrangement.

‘But you still know the movers and shakers in the criminal world?’

‘Not exactly up to date.’ This time Tallis had to lean forward. The noise from the street had suddenly grown in intensity and penetrated the thickened atmospherics. Sounded like the Dolphin Police, a rapid response motorcycle unit, but when he glanced round, trying to source the din, he saw a Ducati hacking down the narrow street, zipping in and out, driver and pillion passenger clobbered up in leathers and helmets. They must be cooking, Tallis thought.

‘Reason I ask…’

But Tallis wasn’t listening. He’d turned back. Something was off. Couldn’t quite work it out, but his sixth sense was suddenly on full alert. The air throbbed. Street hawkers continued to ply their wares but the chatter of conversation receded like someone had turned down the volume control. He felt that nip in the pit of his stomach, part fear, almost sexual, like when he’d been going into a firearms incident. Everything that happened next followed in slow motion. The driver ground to a halt, one foot resting on the pavement, bike tilting at an angle, the engine still running and revving. Garry glanced to his right but, unperturbed, continued to talk. Too late, Tallis saw the pillion passenger reach into his jacket. Fuck, too late, he saw the gun, the outer reaches of his mind processing that the weapon was a Walther PPK. Tallis shouted out, and dived for cover as three shots rang out and hit Garry in the chest.

Chaos broke out. Someone shouted. Everyone hit the deck. Tables overturned. Glass and crockery smashed. The British girl was screaming her lungs out, as were several passers-by. Blood was pumping out of Garry’s chest like an open faucet and although Tallis ripped off his shirt and tried to staunch the flow, it was no use, no fucking use at all. Blood. Blood everywhere.

‘Bir ambulans cagrin! Polis cagrin!’ the café owner screamed. Get an ambulance. Call the police.

‘Report,’ Garry rasped, his face fast draining of colour, becoming pale as old snow.

‘Take it easy, mate,’ Tallis said, applying as much pressure as he could to the wound, appalled at the speed with which Garry’s body was going into shock.

‘Report,’ Garry said again, his breath laboured, expression contorted, life-blood filling his mouth and spurting out between his teeth.

‘Don’t speak. It’s all right,’ Tallis murmured, watching with dismay as Garry’s body twitched and juddered. ‘Everything will be all right.’

But it wasn’t. Two minutes later, Garry was dead.

Tallis leapt to his feet and ran. The imagined sound of the speeding motorbike drum-rolled like a heavy-metal soundtrack in his head. He guessed the killers had headed off in the direction of Galata Bridge, a bridge spanning the mouth of the greatest natural harbour in the world, the Golden Horn, and providing the vital connection to the dense interior of the city. Although they had more than a head start, would have probably ditched their bike by now, stripped off their leathers and jumped into a car or cab, even though pursuit was entirely fruitless, Tallis gave chase. It didn’t matter that he was a stranger and this was their terrain. Didn’t matter that the traffic, which the police systematically failed to control, was clogging every turning. Some bastard had just callously killed his friend. Bloodied, tense with anger, oblivious to the baffled stares of Turks and tourists, he continued for almost a full kilometre, through streets dense with a tapestry of colour and life until, lungs exploding, he stopped, pitched his six-foot-two-inch frame forward and gasped for breath. Several lungfuls of fetid air later, he walked back to the café defeated.

At the sight of the police, Tallis took another big, deep breath. He’d only ever had one encounter with them and that had been the customs guys. He and his fellow sailing companions were drifting dreamily through navy-streaked and turquoise-coloured seas alongside Patara beach when a high-powered launch suddenly disturbed the calm and roared towards them. Two officers lashed their boat to the gulet, climbed on board and aggressively demanded to see everyone’s passports and papers, their disappointment at finding everything in order palpable. Tallis was used to aggro, but his fellow travellers found it a deeply unsettling experience.

The police had clearly moved with impressive speed, he thought, looking around him. The café, no longer a place of entertainment, was cordoned off as a crime scene. Someone had draped a tablecloth over Garry’s body, though nothing could conceal the vast amount of blood that slicked the ground. Several security police officers in uniform were talking to witnesses. Traffic police, distinguished from the others by their white caps, were trying, and failing, to disperse the gathering crowd of onlookers. Out of them all, one man stood out. He was short and trim. Educated guess, Tallis thought, a man in his forties. Cleanshaven, with a shock of dark hair, the officer’s nose was wide, mouth full and mobile and his teeth were spectacularly white. He wore navy trousers and a pale blue, shortsleeved shirt, open-necked. He was speaking in rapid Turkish, ordering his men to ensure that witnesses remained where they were, that nobody was to leave without his say-so. Might prove tough, Tallis observed. The single man who’d been sitting alone, playing with his mobile phone, was noticeably absent.

At Tallis’s approach, the man in charge turned, introduced himself as Captain Ertas.

‘You must be the Englishman.’ Dark eyes that appeared to miss nothing fastened onto Tallis. He suddenly realised the state he was in. In any other circumstances he’d have felt a prime suspect. ‘Why did you run away?’ Ertas said.

‘I didn’t. I gave chase,’ Tallis said evenly.

‘Lying dog,’ one of the uniformed officers said. Tallis understood every word, but resisted the temptation to either look at him or answer back. More valuable for them to believe he couldn’t speak the language.

‘I understand you were with the dead man,’ Ertas said, inclining his head towards Garry’s fallen form. Tallis noticed that Ertas spoke excellent English with an American accent. Probably one of the new, modern, ambitious brands of Turkish police officer that choose to study at the University of North Texas and get a criminology degree.

‘Yes,’ Tallis confirmed.

Ertas stroked his jaw, said nothing for a moment. ‘Friend?’ Ertas enquired.

‘Acquaintance.’

‘He has a name?’

‘Garry Morello.’

Ertas nodded again. He already knew, Tallis thought, just checking to see whether we’re singing from the same hymn sheet. He’d probably checked Morello’s pockets straight away and found his passport. Since a spate of terrorist attacks, aimed mostly at the police, it was obligatory to carry some form of identification, particularly in the city. ‘And you are?’

‘David Miller,’ Tallis said.

‘Passport?’

Tallis unzipped the pocket of his trousers and handed it, freshly forged care of the British Security Service, to Ertas. Not that they needed to have gone to so much trouble. From what he’d heard it was pretty easy to fool the Identity and Passport Service. All you needed was a change of name by deed poll.

‘Your business here?’

‘Tourist,’ Tallis replied.

‘And what do you do when not a tourist?’

‘I’m an IT consultant.’

Ertas said nothing.

‘I sell technology systems to the hotel and leisure industry,’ Tallis said smoothly.

Ertas raised his eyebrow as if technology was a dirty word. This wasn’t quite going according to plan, Tallis thought. Everything he said seemed to rattle Ertas’s cage. Was it personal or had Ertas rowed with his wife that morning? Historically, the cops were poorly paid, lacked proper facilities and received contempt from the rest of the population. Tallis had thought this a thing of the past. Perhaps he was wrong.

Ertas glanced at Tallis’s passport and read through the bogus list of destinations to which Tallis had ostensibly travelled. Tallis mentally ticked them off—Spain, Germany, Czech Republic, United States of America.

‘Look, I could really do with cleaning up.’

‘Of course,’ Ertas said, handing back the passport. ‘I will instruct one of my officers to fetch you clean clothes. You may use the facilities at the station. You have no objection to accompanying us, Mr Miller?’

‘None at all.’

‘Your relationship with Mr Morello…’

‘A passing one.’ Christ, Tallis thought, this could get tricky. ‘We’d briefly met in London. Mr Morello is, was,’ he corrected himself, ‘a journalist.’

‘A crime correspondent,’ Ertas said with a penetrating look.

Ertas didn’t get that off the passport, Tallis thought. ‘I believe so.’

‘So your friendship with him had no professional basis.’

‘None.’

‘Affedersiniz.’ Excuse me. It was the uniformed officer who’d made the jibe about Tallis being a lying dog. He was stick thin with the same sweating, sallow features Tallis had observed on smackheads. He was instantly reminded of a conversation he’d had with Asim, his current contact in MI5 and the guy he directly reported to. It was suspected that many Turkish drug gangs were protected by officialdom. Same old: heroin and money. Tons of it.

‘Evet?’ Yes? Ertas said impatiently.

‘The café owner.’

‘What about him?’

‘He says he saw everything.’

‘Ve?’ And?

‘He says the bullet was meant for the Englishman,’ the police officer said. Eyes narrowed to slits, he looked straight at Tallis.

2

WHY the hell would he say that? Tallis wanted to demand. Fortunately, Ertas asked the same question.

‘The dead man often frequented the café,’ the uniformed officer replied. ‘He was well known, respected.’

‘Even respected men are killed,’ Ertas said, with irritation. ‘Besides, if Morello routinely visited the café, he was an easy target.’

‘He says,’ the officer said, jerking his head in the direction of the café owner, ‘that Miller’s reaction was so swift, he must have known the bullet was meant for him.’

Balls, Tallis thought contemptuously as he was hustled into a waiting police car. He simply possessed excellent reflexes and training. But he could hardly mention that to the police.

The Grand Bazaar nearby had its own mosque, bank and police station, but Tallis was taken to Istanbul Police Headquarters. Tallis hoped it wasn’t the next target for a suicide bomber. Not that long ago, police stations had become a terrorist’s dream location.

If there was air-conditioning, it wasn’t switched on. The overwhelming noise came from a flurry of flies buzzing around, either copulating or beating the shit out of each other. It was so hot inside, Tallis thought the concrete walls might crack and explode. At first he was forced to wade his way through several impenetrable layers of administration, lots of hanging around, lots of giving the same information, lots of meeting the tired gaze of disinterested clerks who smoked like troopers. He noticed that his fellow witnesses were detained elsewhere. Lucky them, he thought.

In bureaucratic limbo, he had ample time to consider his position. As traumatic as the sudden turn of events was, it didn’t need to jeopardise his cover. To come clean would only confuse and complicate the issue. Besides, he really didn’t want Asim alerted to the mess he was in. Wouldn’t look very suave on a first outing with his new handler, especially as it might be construed as treading on the Secret Intelligence Service.

As for the café owner’s remark, he reckoned the man had it all wrong. Tallis had witnessed the hit for himself, seen it coming. At no time had he been afraid for his own personal safety. It had been more a diffuse fear of being caught in someone else’s crossfire. Which brought him back to Morello. Who would want him killed? Sure, as a crime correspondent Garry mixed in muddy circles, but he was British, for God’s sake, and British journalists didn’t usually get themselves slotted—unlike their Russian and Turkish counterparts. So, whomever he’d pissed off, or whatever it was he’d stumbled across that meant his life was worth extinguishing, it had to be big.

Ertas turned up an hour and a half after Tallis’s arrival. ‘So sorry to keep you. Much to do,’ he said, rolling his eyes.

‘Have you contacted Mr Morello’s wife?’ Tallis said, his stomach lurching. It was a second marriage for Gayle. She’d lost her first husband in a car accident. What a lousy hand of cards she’d been dealt, Tallis thought grimly.

‘Next of kin have been informed,’ Ertas said in businesslike fashion. ‘Everything to your satisfaction?’ he added, eyeing the clean shirt Tallis was wearing. It wasn’t. The shirt was a half collar size too small.

‘Fine.’

Ertas suggested coffee, an invitation which Tallis gratefully accepted. After giving the order to a junior officer, Ertas took Tallis down the corridor and into an area the size of a doctor’s consulting room. It was cooler in here. The fan actually seemed to work, rather than simply rearranging warm air. There were two chairs either side of a large desk upon which rested a telephone and a number of buff manila folders. In the corner were several filing cabinets.

Closing the door behind them, Ertas indicated for Tallis to sit down. Tallis noticed that Ertas was wearing a ring, a thick gold band inlaid with tiny precious stones. Although jewellery, particularly gold, was sold in abundance at the Grand Bazaar, with only a tiny charge for craftsmanship, it seemed like a strange affectation for such a seemingly precise and ordered man.

‘Before we begin,’ Tallis said, ‘I’d like some legal representation.’ He might know the form in Britain but here he was boxing in the dark.

‘Not necessary, I assure you.’

‘Then I’d like to contact my embassy.’

‘We can arrange this for you.’ Ertas smiled politely. He picked up a phone and, with a flourish, asked to be put through to the British Consulate. Tallis listened in as Ertas explained the situation. As far as he could deduce from Ertas’s side of the conversation, someone was on their way.

The coffee arrived in traditional Turkish coffee cups. Both men took their time stirring in sugar. Tasted good, Tallis thought, taking a sip. Black and strong, it was a hell of an improvement on West Midlands cop coffee. Ertas spent several seconds surveying Tallis and Tallis spent several seconds looking at him. ‘For a man who has suffered a terrible experience, you seem very relaxed, Mr Miller.’

‘Probably shock. I haven’t had time to process it.’ Which was true. He’d witnessed men die in battle, seen the grotesque dance of bodies hit by machine-gun fire. He’d coldly observed the messy aftermath of suicide by shotgun, and the remains of turf wars played out on busy Birmingham streets, yet Garry’s death fell into none of those categories. Unexpected, cruel and apparently without motive, it felt strangely and horribly similar to Belle’s. The only difference: Garry had been a friend, Belle a lover. Tallis gave an involuntary shudder. He should be falling apart, he guessed, but he was too empty to feel anything right now.

‘And do you normally play Rambo?’ Ertas enquired.

Cheeky bastard, Tallis thought. About time Ertas got up to speed on current American heroes. At least he could have chosen someone nearer his age. Sly must be almost double it. He gave a lazy shrug. ‘Can’t say I’ve ever been put in that position before.’

Ertas leaned back in his seat. ‘We are trying to establish Mr Morello’s movements before he went to the Byzantine.’ ‘I wouldn’t know.’

‘He said nothing?’

‘We’d hardly had time to exchange much more than a greeting,’ Tallis said.

‘You don’t think he was followed?’

‘And the hit team tipped off?’

Ertas smiled. ‘You use dramatic language.’

‘Killers, then.’ Tallis briefly returned the smile. ‘If he was, I know nothing about it. He certainly didn’t suggest to me that he was being followed.’ Garry probably wouldn’t have known. He had been too preoccupied, Tallis remembered.

‘And how did he seem?’

Restless. ‘Hot.’

‘Troubled?’

‘By the heat, yes.’ He was playing hardball with the guy. He knew it. Ertas knew it. But, then, Ertas knew a lot more than he was letting on, Tallis sensed. We’re both playing masters in the art of deception.

‘We have witnesses who appear to think that you were the intended victim.’

‘Bullshit.’

Ertas smiled again. ‘You are very direct, Mr Miller.’

‘My apologies.’

‘Not at all. I like a man who is straight with me.’

Ditto, Tallis thought, meeting Ertas’s smile with one of his own.

‘So you really think the other witnesses were mistaken?’ Ertas pressed.

‘Others?’ He’d thought only the café owner had expressed a view. Careful, he reminded himself, you’re not supposed to understand the language.

‘Does it make a difference how many?’

‘Not particularly. Like I said, they’re wrong. In the heat of the moment, it’s quite easy to draw flawed conclusions.’ Tallis could have given Ertas a lecture on perceptual distortion, the firearms officer’s nightmare. What the brain couldn’t process, it made up. Wasn’t lying, simply the mind’s natural inclination to join the dots and fill in the blanks. It often explained discrepancies in witness accounts.

‘I’d like you to run through everything that happened,’ Ertas stated, ‘from the time you were seated in the café to the final tragic event.’

Tallis did. Ertas listened. He interrupted only once. ‘You say the gun was a Walther. How do you know?’

Damn, Tallis thought. No way could he bluff this one. Only way to go: tell Ertas the truth. ‘It has a very distinctive finger-extension on the bottom of the magazine, giving a better grip for the hand.’

‘I didn’t know IT consultants were so well versed in firearms.’ Ertas’s dark eyes lasered into Tallis’s.

‘I served in the British army as a youngster.’ It wasn’t a very compelling explanation. The most he’d learned in the army about weapons had been directly connected to theatres of war—SA80s, 30 mm Rarden cannon and 7.62 mm Hughes chain guns—but Ertas gave the impression of accepting his account.

‘And the motorcyclists—did you see their faces?’

‘No.’

‘Think they were men?’

Tallis hesitated. The individual riding the bike had certainly seemed too big and broad to be a woman, but judging by half the female population of the United Kingdom you simply never knew. The pillion passenger had been much smaller and could have been of either sex. He told Ertas this. Then something else flashed through his brain. Maybe he was mistaken. Maybe he imagined it. Surely not, he thought.

‘And which way did they go?’ Ertas said, breaking into Tallis’s thoughts.

‘Heading for the bridge.’

Ertas asked Tallis to repeat the conversation he’d shared with Morello. Tallis gave an edited account. He wasn’t going to mention Kevin Napier or the Serious and Organised Crime Agency. As far as Ertas was concerned, he and Morello had been two Brits who’d happened to run into each other, chums passing the time of day. Happened all the time.

‘Did Mr Morello have any enemies?’

‘I wouldn’t know but, I guess, in his line of work you can’t rule anything out.’ Tallis remembered the mezeeating Russians. Garry had written a book. Had he pissed someone off? He floated the idea. Ertas seemed to file the information away. Again, Tallis had the sensation that Ertas knew something he didn’t.

‘Whose idea was it to meet at the Byzantine?’

‘Mr Morello’s.’

‘Did you know it’s a hangout for the criminal fraternity?’

‘I didn’t, no.’ So that was it, Tallis thought. Made perfect sense. The cops had already got a line going there. Probably explained why Ertas was so suspicious of him and how the police had got there so quickly. ‘Perhaps there lies your answer.’

Ertas gave him a slow-eyed response. ‘A line of enquiry to follow, certainly. I noticed from your passport that you have spent almost three weeks here.’

‘That’s correct.’

‘In Istanbul?’

‘No.’ Tallis told Ertas about his sailing trip on the gulet and then his week of resort-hopping via taxi to Marmaris and Bodrum and finally the coach ride to Ephesus, one of the greatest ruined cities in the Western world. Images of colonnaded marble streets, intense heat and dust, the threefloored library with its secret passage to the brothel, and the Gate of Hercules, which formed the entrance to Curetes Street, flashed through Tallis’s mind. Everywhere there’d been reminders of Ephesus’s past. It was reputed that if the city’s torches were not lit, Ephesus was in peril.

‘And when are you planning to return?’

When I’ve got what I came for, Tallis thought. ‘Not made my mind up yet.’

There was a knock at the door.

‘Bir saniye lutfen.’ Just a moment, please, Ertas said, getting up. ‘So you say you’ve been in the city here for the past week?’

He was really labouring the time factor, Tallis thought. He guessed Ertas appreciated accuracy so he gave it to him.

‘Five days.’

‘Five days,’ Ertas repeated. ‘Where are you staying?’ Ertas asked, opening the door.

‘The Celal Sultan Hotel.’

The skinny police officer with the sallow, sweating features was standing on the threshold. He handed Ertas a note. Ertas took it, thanked the man, closed the door and, thoughtfulness in his expression, sat back down. ‘We will not be releasing the details of this afternoon’s incident,’ he told Tallis. What he meant, Tallis thought, was that they would not be releasing the identity of the victim. If it was suspected that Garry had been the wrong target, the police didn’t want the killers coming back for a second crack at it. Probably a sensible precaution, or…

Something inside him buckled. What if he was wrong? What if someone had got it in for him? He immediately discounted his current connection with Asim, his MI5 handler, as a factor—all he’d done was keep his ear to the ground, visit certain places, clock faces, all low-key. He was playing the original grey man—most intelligence gathering was mundane, quiet and unassuming. He’d done nothing to stir up that kind of violent response, but it was perfectly conceivable that others from his past might bear him a grudge.

‘Are you all right, Mr Miller?’

‘What? Oh sure,’ Tallis replied.

The phone rang. Ertas picked up. ‘Right,’ Ertas said, standing up.

‘That it?’ Tallis said, making a move.

‘For now, but, please, no need to get up. I understand there is someone from the embassy to see you.’

Jeremy Cardew was not Tallis’s idea of an official from the consulate. From the name alone, he’d expected a louchelooking middle-aged individual, dressed in creased linen, with an expanded belly and public-school accent. This bloke was probably not much older than Tallis, whippetthin and, as it turned out, originally from Newcastle, which explained the Geordie accent. He had pale, penetrating eyes that assured Tallis he was a man given to action. After the swift exchange of names, and handshakes, Tallis explained his situation. Cardew’s expression became one of growing concern. He’d barely finished before Cardew started quizzing him as effectively as Ertas then, like a rabid trade-union official of the old school, launched into a low-down on procedure, outlining what he as an embassy official was empowered to do—help with issuing replacement passports, providing local information, assisting individuals with mental illness, helping British victims of crime and, more relevantly Tallis thought, ‘doing all we can should you be detained’.

The list of what they couldn’t do was shorter but of more consequence. ‘Can’t give you legal advice, I’m afraid,’ Cardew pointed out. ‘Neither can we help with getting you out of prison, prevent the local authorities from deporting you after sentence or interfere with criminal proceedings.’

Tallis folded his arms. ‘Looks like I fall outside all the categories.’

‘They’re not keeping you, then?’ Cardew’s expression was not one of disappointment exactly, more surprise.

‘I’m free to go,’ Tallis assured him.

‘And you had no problems with the police?’

‘None at all.’

‘You’ve given a statement?’

It felt like several. ‘Yes.’

‘You’ve clearly been through a most traumatic experience,’ Cardew said, with what felt like genuine concern, ‘but, from what you’re saying, it looks as though you have the situation under control.’

Hardly, Tallis thought. He was having a hard time coming to terms with Garry’s violent death. Inside, he was churning with emotions.

‘Just thought you should be made aware of my circumstances. For my own protection,’ Tallis added.

Cardew’s features fell into a quizzical frown. ‘Turkey’s moved on a lot since Midnight Express.’

A film about an American student arrested in Turkey for carrying hashish, Tallis remembered. The scenes of prison brutality were chilling. ‘I’m sure it has, but—’

‘When the police have finished with you, my advice would be to get the next flight back.’

Tallis met the other man’s eye. ‘I don’t want to.’

‘Then I suggest, Mr Miller,’ Cardew said slowly, his voice tight and strained, ‘stay out of trouble.’

‘Right,’ Tallis said, meeting Cardew’s steely gaze. ‘I’ll try to remember that.’

3

TALLIS returned to the Celal Sultan, a pretty, traditional town house in the old city centre, not far from the Blue Mosque and Topkapi Palace. He took a circuitous route, as he’d done since his arrival, variously taking a cab one way, tram back the other, and finally walking to check for and shake off any possible tail. His fully air-conditioned room, Moroccan in style, was a familiar and welcome relief. Now that he was in the privacy of his own space, he seriously felt in need of a drink. Garry’s death had left him stunned. But, in his heart, he knew that alcohol, far from further deadening his senses, would only bring his emotions roaring to the fore. He couldn’t take that risk. Stripping off, he shaved then took a long, cool shower and considered the day’s events.

He still clung to the thought that, horrible though it was, Garry had been the target rather than himself. Tallis couldn’t think of anyone offhand who bore him a grudge and, even if they did, he believed that if someone were going to kill him, they’d attempt it back in the homeland, not here in Turkey. Why go to the trouble? Only one major spike in that theory: the killers were British.

He turned the shower to cold, feeling a pleasurable cascade of water across his skin, and tested out his theory on the ethnicity of the killers. That shout he’d heard amidst the chaos was as captured in his mind as the memory of Belle’s smile. As sure as he could be, he’d heard the words ‘…fuckin’ out of here’. Not Turkish, not any other nationality, Anglo-Saxon, pure and simple. At least one of those guys was definitely British.

As far as his current activities were concerned, he was simply maintaining a watching brief. Since the new man, a former grammar-school boy, had taken over MI5, there had been a significant change in direction, which meant that people like him could play a role. Some called it privatisation of the security services, and something to be feared and resisted. All he knew was it gave him gainful employment. He wasn’t officially on the books, never would be. He was more mercenary than spook, a necessary evil and, he had no illusions, expendable. He tilted his face up towards the showerhead, opening his eyes wide, thinking about the brief and exploring the suspected link between terrorism and British organised crime. The hardcore terrorist relied more on the spoken word to transmit information than the written, and it was generally carried out person to person rather than via an easily traceable phone line or computer. So far he thought he’d stumbled across nothing significant, but the killing at the café changed everything. Ertas, by his manner, had given the game away.

Tallis turned off the shower, ran a hand through his hair and reached for a towel. He rubbed himself dry, caught sight of his lean, deeply tanned and muscular reflection in the mirror. He was probably in better physical shape than he’d been for a couple of years thanks to some fairly serious working out. Mentally, he still pushed all the buttons. Only the slightly haunted look in his dark eyes spoke of a man who’d lost the very person he needed to live for. Belle, he thought, what I wouldn’t give to see you again, to hear your voice, to hold you. Christ, it’s so damn lonely here on my own.

Dressed again, he took out a hunting knife from underneath the clothes in the bottom of the wardrobe. He’d bought it from a trader, no questions asked, after a memorable visit to Gemiler Island where, long ago, legend spoke of an albino queen who’d lived there. To protect her from the blistering sun, the islanders had built a walkway, hewing out the solid rock so that she could walk freely from the temple at the top of the island down to the sea. Tallis had followed the trail, chipped and crumbling now from the tread of many pairs of feet, and marvelled at such devotion. Tombs embedded on either side gave it a spooky feel.

Back on the gulet once more and only a few metres out to sea, he’d heard the familiar put-put sound of one of the many little boats trading everything from sweet and savoury pancakes and ice cream to rugs and painstakingly embroidered scarves or oyali, and neckerchiefs. Except this boat and its wares were different. The woman, sure enough, was selling legitimate goods. Her gypsy-looking colleague, however, after some minor probing, was in the market for what he called ancient ornamental weapons. Four inches long, with a wide stainless-steel blade ground to a deadly point, the knife was neither ancient nor ornamental but it was more than enough to frighten, maim or kill. Not that Tallis harboured malign intent. Just wanted back-up. He flicked the blade open and closed it again with lightning speed, one-handed. The knife felt solid in his grip yet light to carry. Perfect. With the same minimum of fuss as when he’d made the purchase, he slipped it into the pocket of his chinos, and went down to the dining room where he ate a delicious dinner of karniyarik, stuffed aubergines, followed by grilled trout, and headed back out onto the street.

It was steamy as hell outside, the Turkish night asphalt black and starless. Street lamps lighting his way, he headed away from the main tourist area of Sultanahmet towards Constantine’s Column. From there he took a tram out to the massive covered Grand Bazaar with its painted vaults, and streets studded with booths and shopkeepers as pushy and relentless as any City trader. Here, all manner of commercial human activity was at work. He felt as if he was at the centre of a large ant nest, lots of rushing about, even though most of the actual manufacturing and trading was carried out in the hans or storage depots, tucked away behind gated entrances, shaded and concealed. Finding it hard to get his bearings in spite of the profusion of signposts, he allowed himself to be carried along with the flow, through Feraceciler Sok, passing cafés and restaurants with local diners, and ancient copper and marble fountains dispensing fresh water. He skirted the oldest part of the bazaar, veering left and coming to an Oriental kiosk, which had been built as a coffee house in the seventeenth century but now served as a jewellery shop. Left again, he cruised down a street of carpet and textile shops. Overhead, Turkish flags hung with the familiar crescent moon and stars, a reminder and symbol of national pride. After pushing through a scrum of bargain-hunters, he eventually found himself at the entrance to the largest han in Istanbul, the Valide Hani. Beyond lay the Spice Bazaar, inside this the café and last place he’d seen Garry Morello alive.

By returning to the scene of crime, he didn’t really expect to discover anything, the trip more a means to jog his memory and get things straight in his head. Voyeurs and the naturally curious had gathered outside the spot. Someone, he noticed, had laid flowers at the perimeter. Sealed off by white crime-scene tape, a single boredlooking policeman on duty outside, the café was over-run by Turkish Scenes of Crime Officers, their distinctive forensic suits declaring that they were part of an international club. Christ, he thought, guts turning to water, why did he feel so lashed by memories? Before joining the Forensic Science Unit, Belle had once been a SOCO. It was partly the reason he’d elicited her help in a previous case, that and the fact he hadn’t been able to live without her. He felt a spasm of regret and grief shoot through his body. Perhaps, if he hadn’t involved her, he thought blindly, she’d still be alive.

Tallis turned away, partly to shield his face from an embarrassing tear in his right eye, partly to maintain a low profile. At once, he spotted a familiar countenance. Dark eyes met. You, Tallis thought, watching as the stranger unlocked his gaze and walked purposefully away. Tallis observed the smaller man’s retreating form, waited, counted to ten and dropped into casual step behind him. Only two reasons he could think of to explain why the man who’d left the café so abruptly had suddenly turned up on the scene: curiosity or involvement. Or—Tallis felt something flicker inside—it boiled down to the curved ball theory. He, like Tallis, was simply caught up in someone else’s game. Happened all the time.

They were heading west along Cami Meydani Sok, running parallel to Galata Bridge before breaking off into the sort of quiet and narrow streets where you might get your throat cut. Tallis could tell from the way the man was walking that he knew full well he was being tailed. He seemed to be moving in no specific direction, crossing, recrossing and doubling back, all classic anti-surveillance tactics. The law of averages dictated that he had the advantage. Single tails always carried a high risk of exposure.

The man suddenly leapt onto a tram. Thinking he might be heading for Sirkeci station, Tallis clambered into the next car after him. Like all trams, it was clean and fully air-conditioned, a triumph of Turkish engineering and the speediest method to get around in a city like Istanbul. Tallis paid the driver and sat down, keeping his eyes pinned, and rearranged his thinking—thinking that was based on many years’ experience of bad guys. He didn’t doubt that the stranger in the tramcar was probably one of them, up to no good, sure, but not necessarily connected to the hit in the café. So he was taking one hell of a risk by reinserting himself at the scene. He’d have been better off lying low. Tallis smiled to himself. So you are involved somehow, somewhere. More obliquely, he wondered whether this man was also the very type of person he’d come to spy on, one of the many faceless Islamic terrorists, the masterminds, the ghosts, those who had no profile on any security service database.

The tram passed the stop for the station and was continuing in the direction of the Celal Sultan Hotel. Either by accident or design, Tallis felt as if he was coming full circle. Had it been light he would have seen more clearly the painted wooden houses lining the street. As it was, he saw nothing but the glint and glow from sitting rooms and lighted cigarettes. Then the motion of the tram began to change. It was slowing. Sixth sense told him that his man would make a move. Tallis held back, watching and waiting for signs of his quarry. Sure enough, he slipped out and darted through a hole in a hedge and into the outer grounds of Topkapi Palace. Tallis followed him, catching his shirt on a wooded thicket. Cursing as he ripped himself free, he discovered he was standing alone in what looked to be an old rose garden. Shaded by overgrown bushes and plants, the place had a neglected air, making it a perfect rendezvous for lovers or thieves. That he was walking into a trap became a distinct possibility. He looked around him, listened. Pale moonlight sifted down through a sky of banked cloud and suppressed heat, lighting his way.

Then he saw him. No more than twenty metres in front, his man was moving at a slow trot along a designated walkway, towards the palace. Time to change the dynamics, Tallis thought. ‘Merhaba!’ Hello, he called out. The man quickened his step, broke into a run. Tallis kicked off the back foot and sprinted after him, ducking and weaving to avoid being lashed in the face by several overhanging branches. Shorter, the man darted with a quick zip of speed, off the main path and across another piece of woodland, feet pounding the uneven ground, but he didn’t have the staying power, something at which Tallis excelled. He called out again, shouted a reassurance, he only wanted to talk. Still the bloke kept running, jinking through the wooded grounds, giving the strong impression that he knew the place well, that he was heading for a rat run. Then, without warning, he ran back onto the main path, across a square, screeching to a halt, and turned, his face and form illuminated by a shaft of light from a tremulous moon. Hand reaching, face cold as antique marble, lips drawn back in a pale snarl.

Tallis made a rapid calculation. The bloke was carrying. And he was prepared to open fire. Automatically, twisting to one side, Tallis drew out the knife, simultaneously flicking it open, just as the tell-tale glint of gunmetal swung and homed in on him.

His attacker stood no chance. Before he’d even got off a shot, he was falling. The blade had flown through the air, sliced into and stuck fast in his throat.

4

THE man’s death rattle was mercifully short but noisy and terrifying. Tallis glanced around, checking first that he was alone—yes—then searched the body for identification, picking out both a wallet and passport that identified his victim as a Turk by the name of Mehmet Kurt, born in 1977. Next, Tallis looked for a place to conceal the body. He didn’t have great options. All he could do was buy time. Ironically, several metres away lay the Executioner’s Fountain, the place where, long ago, the executioner washed his hands and sword after a public beheading.

Tallis briefly wondered whether he could just ditch the body and run, make the kill look like the bloke was a victim of some assassin with a macabre sense of history. Beyond, there was open ground and the entrance to the Palace. Not a great welcome for the tourists in the morning, Tallis thought, brain spinning like three rows in a fruit machine. That left the Rose Garden, his firm favourite for a shallow grave but too far to cart a body. He gave an urgent glance to his left. There wasn’t much more than a triangle of trees, but it was the best place. The only place.

Dead men were heavy, but Tallis picked the stiff up with relative ease. There was little blood due to the trajectory of the blade—Tallis took care not to disturb or remove it—and though acutely conscious of Lockard’s principle—every contact left a trace—he knew that his DNA was unlikely to be stored on a Turkish database. The British system stood head and shoulders above anything in Europe, which was why fast-track plans to automatically share information were already in place, but that did not include countries bordering the Middle East.

Dumping the body where the trees grew more thickly, Tallis wiped the shaft of the blade. That only left the weapon, which was of professional interest to him. Russian, slim for easy concealment, it was a simple blowback pistol, the PSM, reputed to have remarkable penetrative powers, particularly against body armour. Intended for Russian security forces, it had resurfaced and become available on the black market in Central Europe. Tallis picked it up with a handkerchief and put it next to its owner.

Hugging the side of the path, he retraced his steps back the way he’d come. Once, just once, he felt a shiver of fear that there was someone else in the shadows. He neither stopped, nor looked, but kept on walking. Out onto the street again, he thought about taking a detour to the Cemberlitas Baths near Constantine’s Column. There he could have the equivalent of a steam clean, the best way to rid himself of the odour of death, but it was already fast approaching midnight, the time the baths closed. Adrenalin flooding his nervous system, he strode back the short distance to the hotel.

Back in his room, he ripped off his clothes, threw them into a carrier bag and chucked them into his suitcase. He’d get rid of them in the morning. He showered until his skin stung and put on a clean pair of trousers. After a quick exploration of the mini-bar and coming up empty, he picked up a phone and ordered a bottle of raki, a jug of water, and a pide, a flatbread with salami and cheese. Room service wasn’t part of the package. It was only a three-star hotel. But, in reality, money bought anything.

The food arrived. Tallis offered enough notes to ensure both the porter’s discretion and gratitude. After he’d closed and locked the door, he ate and drank slowly, without pleasure, food and alcohol the best cure for the terrible nausea that followed the taking of a life. While he chewed and drank, his mind brimmed with questions, ranging from burning curiosity about the man he’d killed to how long it would take before the body was discovered. He came to no firm conclusions.

After a fitful night’s sleep, partly as the result of the incredibly high temperature, partly because he was still coming down from his adrenalin fix, Tallis got up, packed up some things and left the hotel shortly before eight in the morning, the carrier bag containing the contaminated clothes swinging idly from his hand.

A saffron-coloured sun beat down hard upon him. Within minutes, his shirt was stuck to his back and perspiration was oozing in a constant trickle from his brow. Heat was doing funny things to his vision. Colours seemed more vivid, shapes less defined. Pavement, buildings, cars looked as though they might burst into flames.

His destination was Eminonu, a port bustling with traders keen to sell goods or offer trips up the Bosphorus. A cooling breeze usually blew in off the water but not today. A small podgy individual with down-turned eyes caught Tallis’s attention. For some reason he had no takers even though the small boat he was chartering looked sturdy enough. Expecting to haggle, Tallis spoke in English and asked how much for a two-hour trip. Predictably, Podgy named his price, which was eye-wateringly high. Tallis immediately offered half. Podgy looked insulted. Tallis shrugged. Podgy broke into a grin, a sign that he considered Tallis a worthy adversary, and offered him a cold drink. Tallis accepted with a gracious smile. All part of the game. He discovered that the little man was called Kerim. ‘Look, Kerim,’ Tallis said, feeling the delicious chill of ice-cold water at the back of his throat, ‘no need to do the full trip. How about you take me as far as the Fortress of Europe and I’ll get the bus back?’

Kerim clutched a hand to his chest as though he was having a heart attack, shook his head, his expression dolorous. ‘Not good. I have expensive wife.’ His Turkish accent was as thick as the coffee.

Tallis let out a laugh. ‘More fool you.’

‘And many, many children,’ Kerim said, face forlorn.

Christ, the bloke could win a BAFTA, Tallis thought. ‘All right,’ he said, feigning sympathy. ‘Full trip, there and back with a twenty-minute stop at the Fortress.’

‘Is better,’ Kerim said, significantly brightening up.

‘And something else,’ Tallis said, lowering his voice.

‘I very quiet,’ Kerim said, pointing to his mouth. ‘I say nothing.’

You’d better not, pal, Tallis thought, jaw grinding at the terrible yet calculated risk he was about to take. Kerim leant in close, allowing Tallis to explain what he wanted the little man to do, that there would be a great deal of money paid if he looked after something he was about to give him, but dire consequences, not only for him but for his family, should he default, then he offered a little more than his original sum for the trip, which, like the good businessman Kerim was, he accepted with a small bow.

Rumeli Hisari was a maze of steep, narrow cobblestone streets leading to tranquil Muslim cemeteries in a fortress setting. Everywhere were reminders of its fifteenth-century past, and the grand plans of Mehmet the Conqueror in his quest to take Constantinople. Much as Tallis adored history, he couldn’t have been less interested. He was looking for a suitable place to get rid of his carrier bag full of clothes. In a little less than ten minutes, he found it. Although most hotel and restaurant lavatories were of the modern flush design, public conveniences remained stubbornly old-fashioned, of the squat-over-the-slot variety. Setting aside any squeamishness, he took out his belongings and thrust them deep into the bowels of the latrine. Nobody in their right mind would try to retrieve them. Ten minutes later, he was back on the boat, allowing his offending arm to trail in the deep and narrow waters of the Bosphorus.

After checking and booking a KLM flight out of Ataturk to Spain, part of a set of precautionary measures following the killing and the previous night’s excitement, he spent the rest of the day lying low, eating a simple meal in the hotel restaurant before retiring to bed early. Deeply asleep, he was suddenly alerted to someone hammering on his door. ‘All right, all right,’ he said, dragging on a pair of boxers, instantly awake. ‘Who is it?’

‘Polis!’

Tallis glanced at his watch. It said two-twenty in the morning. ‘You got ID?’ he called out.

More banging.

He took a deep breath, opened the door a crack, clocking two men in plain clothes flanked by two police officers with firearms. Shit. He opened his mouth to say something. The door burst open. An outstretched fist shot out. Connecting.

Next stop darkness.

5

TALLIS came round feeling muzzy. Half-naked, feet bare, handcuffed, he was lying flat on his back on a piece of thin cardboard. His mouth was dry, as if it were laminated, and his temple throbbed with a viciousness he’d only experienced once before in his life after getting legless, at the age of seventeen, on a bottle of rum. He gingerly ran his cuffed fingers over his body. No broken bones, only bruises.

He looked around. Low-wattage light swinging from the ceiling throwing a nicotine glow on walls the colour of British cement. A hole in the ground signalling a convenience, the malodorous smell and dark cloud of flies buzzing round the entrance further confirmation. A dodgy-looking stain, the colour of dried pig’s blood, on the floor to his right. A steel door, with a slot in it for those outside to see in, remained resolutely shut. So much for Turkish hospitality, he thought dryly. There was no sound of faraway traffic, no human voice, no birdsong, so he guessed he was deep in the bowels of a building. The size of the cell, for that’s what it was, was the human equivalent of a battery hen’s coop. And, Christ, it was hot. His lungs felt as if they were sticking to his ribs. Might as well shove him in an oven, turn it to 200 degrees and roast him.

He staggered to his feet, tried to get his bearings, tried to focus. His watch was missing from his wrist so he had no idea of time. Without natural light he couldn’t even make an estimate. Wherever he’d been taken, he doubted that it was a police station. That worried him.

He retreated to the corner of his cell. Best he could do was conserve his energy, stay upbeat. There was absolutely nothing to connect him to the dead man so it was pointless to speculate about the reason he’d been brought and banged up there—wherever there was. Fear of the unknown was his greatest enemy. He refused to entertain the notion of detention centres and secret police, of places where men were detained without charge or trial, or of ghost prisoners held in legal limbo. He had a high pain threshold, but even seasoned soldiers knew that the mental anticipation and anguish was often worse than the horror itself. As soon as his captors came for him, he decided to play the role of outraged tourist. No heroics. No trying to beat the system. But plain old browned-off from Britain. Oh, and act frightened, he thought. Remember, he repeated to himself, you’re David Miller, boring, lowly IT consultant.

At last, he heard some movement and the scraping sound of metal against metal. The slot in the door drew back. A face with midnight eyes peered in, expressionless, followed by another face, which Tallis immediately recognised. On seeing Ertas, he got up. ‘Captain,’ he began, hope briefly rising. ‘So glad—’ Before he could complete his sentence, the slot slammed shut. Irritated, Tallis hunkered back down on the cardboard. At least he wouldn’t freeze to death.

Hours seemed to pass. He was getting seriously dehydrated, his thinking lacking clarity, becoming muddled. Who was Ertas? Was he part of the administrative police keeping track of foreigners, the judicial police investigating crimes or the dreaded political police who combatted subversives of any denomination? Bound to be crossovers, Tallis thought foggily, or maybe Ertas belonged to none of these groups.

He must have fallen asleep. He woke up with a yell. A guard standing over him had thrown a bucket of ice-cold water over his head. Tallis stuck his tongue out, eager to catch a few precious drops. Two other guards were pulling him up, banging his knees along the concrete, dragging him towards the open door. God, he thought, what next? He’d heard about enhanced interrogation techniques. He’d heard they weren’t very nice.

He managed to get up onto his feet. They were taking him at a fast trot down a dingy corridor. He could hear voices now. Men shouting. A gut-wrenching cry of pain tore through the fetid air. Barked orders.

Stairs ahead. One of the guards led the way, the other behind threatening him with a Taser stun gun should he try anything clever. Not that Tallis had any intention of risking 50,000 volts and total muscle paralysis. The noise was growing louder now. More desperate. The unmistakable clamour of violence. In spite of the heat, Tallis felt a chill as cold as a desert night creep deep into his soul.

The corridor opened out. Overhead strip lighting flickered with enough of a strobe effect to induce a fit in an epileptic. Doors off on either side, some of the metal grilles open, sounds of excessive use of force crashing around his ears. He hoped it was staged. If it wasn’t, poor sods, he thought.

They were walking three abreast, Tallis stumbling slightly, not used to walking in bare feet, and feeling off balance with his hands tied together. Finally they came to the end and to what looked like the type of lift you saw in a car park. One of the guards pressed a security keypad and the metal doors drew apart. Tallis was butted through into another corridor, more stairs, more fancy codes and security panels, more shouts of protest. For a brief moment, he thought he heard the strains of classical music and the sound of dripping water. Must be the product of a vivid imagination. Either that, or he was hallucinating. And then all his birthdays came at once. He was standing in an open space, like an atrium, natural light flooding through the barred windows in the ceiling. So delighted by the sight of the sun crashing down on blue, he hardly noticed Ertas, but he did clock the man standing next to him. Deeply tanned, strong-jawed, and sturdy with eyes that were too close together so that it was impossible to detect who or what he was looking at. The man dismissed the two guards with a short command. At once, Tallis could tell that, fluent though the man’s Turkish was, it wasn’t his first language.

‘This way, please,’ Ertas said, coldly remote, indicating that Tallis follow.

Despite feeling a twat, standing there in his underwear, Tallis stood his ground. ‘This how you normally treat visitors to your country?’ he fumed. ‘I demand to know where you are holding me and why. I also insist that I have full legal representation. I want to see Mr Cardew at once.’

‘You make many demands, Mr Miller,’ Ertas said quietly, with disdain.

Thank God for that, Tallis thought. At least his true identity hadn’t been revealed. Could only make things complicated. A quick visual of the building told him that escape was probably out of the question. The atrium appeared to be the highest point of the structure. There were no other windows, only doors off with a staircase leading down at the opposite end. A man in boxer shorts, even in these soaring temperatures, wasn’t exactly likely to go far. ‘Who’s your friend?’ he said, bolshie.

Ertas answered. ‘You may call him Koroglu.’

Strange, why can’t he speak for himself? Tallis thought, eyeing the man suspiciously.

‘Come,’ Ertas said, pivoting on his heel.

Tallis let out a belligerent sigh. He felt less fear now, his outrage building and genuine. Shown into a room not too dissimilar to the one at the police station, he asked first for water then to be untied. Both requests were ignored.

Ertas pulled up a chair for himself. Koroglu took a position behind Tallis. Ertas asked Tallis to sit down.

‘I pro—’ Two firm hands grabbed his shoulders, fingers digging deep into his nerves. Tallis gasped with shock and slumped down, arms half paralysed. He wondered what rank Koroglu held, from which department he hailed. Bastard division, he concluded.

Ertas, who was sitting opposite, showed no emotion. ‘After you left the station, what did you do?’ His voice was soft, coaxing.

Fucking predictable, Tallis thought, straight out of the hard-guy, soft-guy school of police interrogation. Ertas had probably picked that up in the States, too.

‘Not sure exactly when that was,’ Tallis said, leaning forward slightly, wishing he could rub his arms and get the circulation going. A stolen glance at Ertas’s watch told him it was four in the afternoon.

‘Two days ago.’

Right, Tallis thought so now he knew exactly how long he’d been held, which wasn’t very long at all. Just felt that way. ‘I went back to the hotel. I can tell you what I had to eat if you insis—’

The blow came from the left, flat-handed, mediumstrength, precision-aimed. Tallis’s ear rang. He felt temporarily deafened.

‘I will ask the questions,’ Ertas said softly. ‘You will answer.’

Tallis nodded, raised his tied hands, rubbed at his ear and did his best to look stricken. Inside he boiled with rage. In two fluid movements, he could throw his head back against the goon standing behind him, swing his hands round and punch Ertas in the throat, smashing the hyoid bone.

‘And after dinner, what did you do then?’ Ertas continued elegantly.

‘I went for a stroll.’

‘Where?’

‘Not sure I re—’

Another clout on the other side ensured that he did. He told Ertas what he wanted to hear. No point in denying it. These guys already knew where he’d been.

Ertas leant forward with a tight smile. ‘You were observed, Mr Miller, following a man who is of interest to us.’

‘I don’t know wha—’ Tallis flinched, expecting another blow. But it was Ertas who raised his hand in a restraining gesture. Tallis heard Koroglu grunt with frustration at being denied another chance to use him like a punchbag.

‘You deny it?’ Ertas’s expression was hard.

Tallis smiled. ‘Since when was following someone a criminal offence?’

‘So you were following him.’

Checkmate, Tallis thought. Those blows to his head must have addled his thinking.

‘The man in question,’ Ertas continued smoothly, ‘is a Moroccan known to have links with al-Qaeda.’ A Moroccan? Tallis thought, surprised. According to his victim’s passport, he had been a Turk—unless it was false, like his own. ‘He was deported by your own government two years ago,’ Ertas continued, ‘and is of interest to the United States.’

Shit. Tallis baulked. Who the hell did they think he was? More to the point, who were they? In his mind, the USA was synonymous with extraordinary rendition and secret detention centres. Could this be one of them? From what he’d heard, they were more likely to be found in Poland and Romania, but the closed prisons there were reputed to be full and so the States had outsourced and turned their attention to the Horn of Africa. What all this definitely pointed to: Garry Morello had been onto something, and he was deep in the shit. He remained stubborn. ‘I don’t see what this has to do with me.’

‘Because you were the last person to see him alive,’ Ertas said, down-turned eyes meeting Tallis’s.

‘You mean he’s dead,’ Tallis said, sounding aghast.

Ertas picked up the phone, ordered a jug of water and two glasses. Nobody said a word. Tallis was trying to work out what they wanted from him, confession or revelation? The water arrived. Ertas poured out, unlocked Tallis’s cuffs and handed the glass to Tallis who drank it down in one. ‘Thank you.’

‘So, Mr Miller,’ Ertas said. ‘Would you like to explain exactly what you were doing?’

‘All right,’ Tallis said with a heavy sigh. ‘I admit I followed him. I recognised him from when I was in the café with Mr Morello.’

‘Our Moroccan friend was at the Byzantium?’ Something in Ertas’s expression led Tallis to believe that he already knew the answer to the question.

‘Yes.’

‘Then why didn’t you mention this when we spoke at the station? Why was this not in your statement?’

‘Because I didn’t think it relevant.’

‘But you thought it relevant later.’ There was a cynical note in Ertas’s tone.

‘No, you don’t understand.’ Tallis allowed his voice to notch up a register to simulate frustration. ‘It was only because I saw the guy there in the evening.’

‘When you went back to the café,’ Ertas said, scratching his head.

‘Foolish, I know, but I was hoping to find something important that might help with your inquiry.’

Ertas flashed another tight, disbelieving smile. ‘And then what?’

‘I followed him.’

‘Where?’

‘To the gardens at Topkapi. Then I lost him.’

Ertas glanced up at Koroglu. ‘Ask him what he was planning to do,’ Koroglu ordered in Turkish. Ertas nodded. Obedient, he put the question.

‘I don’t know.’ Tallis shrugged. ‘Talk.’

‘To a stranger, in the middle of the night, in a foreign land? Wasn’t that reckless of you?’

‘I suppose it was. I wasn’t thinking.’ But he was now; he was thinking that the guy standing behind him wasn’t what he seemed at all. He’d assumed Ertas was calling the shots. He was wrong.

‘Did you know he was armed?’ Ertas said, watching Tallis like a crow observed carrion.

‘Certainly not.’

Koroglu spoke again. ‘Tell him that we know he intended to meet the Moroccan. Tell him that he had already contacted him in Britain. Stress that he has already lied and to lie further will only make things worse.’

Tallis did his best not to jump in, to shout and protest his innocence. Ertas, meanwhile, cleared his throat and repeated word for word what Koroglu had said.

‘This is ridiculous. I never met the guy before coming to Turkey. I don’t even know his name.’

‘And your name is?’

Neat move. Tallis didn’t flinch. ‘David Miller. Look, is this a case of mistaken identity or something?’ he said, twisting round. Mistake. Koroglu whipped a ringed hand across his mouth. Tallis registered the distinctive taste of metal and sand as blood dribbled down his chin.

‘Point out that we can keep him here indefinitely if we have to,’ Koroglu said savagely.

Ertas did.

‘I’m a British citizen, for God’s sake. You have no jurisdiction to keep me here.’

‘Tell him to shut up. Ask him about his business interests,’ Koroglu commanded.

Ertas again complied.

‘What? I told you, I’m an IT consultant.’

‘You work from home?’

‘No, I—’

‘Where is home?’

‘Birmingham, West Midlands, UK.’

Ertas glanced up at Koroglu with a significance that made Tallis realise he was sunk.

‘What is your religion, Mr Miller?’ Ertas said, inclining towards him.

‘My religion?’

Koroglu bent over him and with one swift movement grabbed him by the balls.

‘You understand the term?’ Ertas said, scathing.

‘I was brought up a Catholic,’ Tallis gasped, eyes watering. That was true. His Croatian grandmother had insisted on it.

‘And now?’

Once a Catholic, always a Catholic. ‘I’m lapsed,’ Tallis grunted. The pain was searing.

Ertas frowned incomprehensibly. Koroglu explained in Turkish then let Tallis go with a final squeeze of his genitals.

Ertas turned his eyes to Tallis. ‘You have not converted to Islam?’

Jesus, now Tallis knew exactly what they were driving at. After the London bombing of 7/7, many nations, the USA in particular, were critical of Britain for spawning its very own breed of homegrown suicide bombers. Originally termed ‘clean skins’ by the British security services, it had since been revealed that the culprits had already come to the attention of MI5 and were associates of those later convicted of a fertiliser plot that amongst other targets would have had the Bluewater Shopping Centre in Kent blown to smithereens. As much as the British Government was viewed as an important ally, its citizens were regarded with a great deal of suspicion. Tallis had just fallen under that particular cloak of distrust.

‘Look, guys, I already explained. You have this all…’ Tallis shot out of the chair, threw his head back, heard the sickening crunch as it connected with Koroglu then made a grab for Ertas. Knocking the captain to the ground, he made a dive for the door, tore it open and ran.

The level was approximately three hundred metres long with a metal staircase leading down. Tallis ran the full length, took and charged down the steps. Christ knew where he was heading. All he knew was that if he wanted to breathe air again, see the sun, he had to get out. He’d heard too much about places where only the people holding you knew you were there.

The building opened onto another level: gangway to the left; railings on the right. Below was a long row of openbarred cells with men tightly caged together. An alarm sounded, the noise triggering them into action. Immediately, they started shouting abuse, rattling against the bars of their prison, jeering as a group of armed officers speeded past. Tallis kept running, muscles in his legs knotted, bare feet pounding, oblivious to the sound of shouts and clattering feet behind him as he leapt down the next staircase. On hitting the bottom, a guard, younger than the rest, raised his weapon, but Tallis twisted away, the ensuing shot missing him by a whisker.

More men now. More shouts. Tallis zigzagged as much as he could in the confined space, eyes to the front, focused on the end set of doors, wondering how he was going to get through, how to operate the security lock, how…

The doors snapped open. Koroglu stepped out, blackeyed, mean and moody. Didn’t look like a man to bargain with. Tallis put both his hands up in a defensive gesture. ‘All right, let’s be cool about this,’ he said.

‘Shut the fuck up,’ Koroglu snarled before delivering a knockout blow.

6

THE cell in which Tallis surfaced was no improvement on the original. Concussed by the second serious blow to his head in less than twenty-four hours, he still, mercifully, retained a sense of direction. If the previous guest suite was located on the third floor down, he guessed his current quarters were four floors. It stank of human excrement and despair. The single light hanging from the ceiling only further illuminated the hopelessness of his situation. Same old squat hole. Same lack of water. Thin layer of cardboard replaced by a stone plinth for reasons that soon became obvious—his cellmates were a small family of rats. The way his stomach was growling from lack of food, the best thing he could do was kill and eat them. Welcome to the Turkish Hilton, Tallis thought, taking immediate advantage of his new bed.