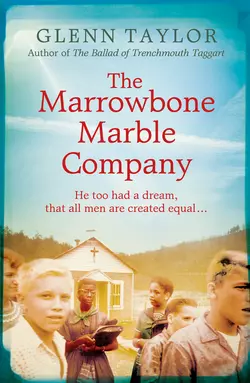

The Marrowbone Marble Company

Glenn Taylor

A powerful novel of love and war, righteousness and redemption, and the triumph of the human spirit.1941. Orphan Loyal Ledford lives a very ordinary life in Huntington, West Virginia. By day a History major, by night a glass-blower at the Mann Glass factory where he courts the boss's daughter Rachel. Preferring to read rather than talk about the war raging in Europe, he focuses his mind upon work and study. However when Pearl Harbour is attacked, Ledford, like so many young men of his time, sets his life on a new course.Upon his return from service in the war, Ledford starts a family with Rachel, but he chafes under the authority at Mann Glass. He is a lost man, unconnected from the present and haunted by the memories of war, until he meets his cousins the Bonecutter brothers. Their land, mysterious, elemental Marrowbone Cut, calls to Ledford, and it is there, with help from an unlikely bunch, that The Marrowbone Marble Company is slowly forged. Over the next two decades, the factory town becomes a vanguard of the civil rights movement and the war on poverty, a home for those intent on change. Such a home inevitably invites trouble, and Ledford must not only fight for his family but also the community he has worked so tirelessly to forge.Returning to the West Virginia territory of the critically acclaimed The Ballad of Trenchmouth Taggart, M. Glenn Taylor recounts the transformative journey of a man and his community. A beautifully-written and evocative novel in the tradition of Cormac McCarthy and John Irving, The Marrowbone Marble Company takes a harrowing look at the issues of race and class throughout the tumultuous 1950s and 60s.

THE MARROWBONE

MARBLE COMPANY

A Novel

GLENN TAYLOR

Copyright (#ulink_2214629d-b6c1-542d-b28c-3d7a92e975e8)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

Copyright © Glenn Taylor 2010

Glenn Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-00-742328-6 (Hardback)

ISBN: 978-0-00-735907-3 (Trade Paperback)

Ebook Edition © 2010 ISBN: 9780007369393

Version: 2015-10-28

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Black ground was fenced for men to till. The dead of Gauley own this hill.

—Louise McNeill

Contents

Cover (#u16f36af3-7118-5ffb-832e-7bdcc70f1f83)

Title Page (#u4bc33803-e16e-5d62-ae8e-7eb399af635d)

Copyright

Epigraph (#u2e8d2aeb-de3d-5131-b1fe-df0f431fb607)

Prologue - January 1969

I - A Line in the Dirt

October 1941

November 1941

December 1941

August 1942

September 1942

October 1942

November 1942

August 1945

May 1946

June 1946

September 1947

October 1947

November 1947

February 1948

May 1948

July 1948

September 1948

November 1948

April 1949

October 1951

June 1953

II - A House on the Sand

June 1963

August 1963

September 1963

December 1964

February 1965

March 1965

April 1965

May 1966

June 1966

February 1967

June 1967

July 1967

September 1967

October 1967

February 1968

March 1968

April 1968

July 1968

December 1968

January 1969

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Glenn Taylor

Author’s Note

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue January 1969 (#ulink_0761b8ec-c449-51fe-a0ca-4c58d8963e41)

THE GROUND WAS THE color of rust. Holes the size of half-dollars were every where, some encircled by tiny mounds of dirt. This was hard earth, nearly frozen. Dried-up leaves and spruce needles turned brown. A hush had befallen the land, as still as the inside of a coffin. Such quiet recalled a time before timber had framed houses and a church, before plumbing hooked in hot and cold, before electricity snaked conduit. The trees slept. The creek was iced over.

At the back of the hollow, there was piled ash and shingle. Sheet metal lengths. Two-by-fours at peculiar angles, their surfaces bubbled and cracked and black. There was a furnace stack, fifty feet high and made from fieldstone. It towered above all that fire had taken, but its mortar was crumbling. A strong wind would soon enough knock it down and stir the ash and frayed black picture-frame wire and lampshade bones below.

Snow came. It landed silent on a thick sheath of glass, the size and shape of a backyard pond. This glass had run molten, but now it was cooled, its edges rounded, frozen in rolls. A woman walked a circle around it. She held in her hands a Bolex 16mm movie camera. She filmed the glass. Thought for a moment she had seen a fish eye looking up at her from beneath.

This tract of land had known many names. Bonecutter Ridge, Marrowbone Cut, the Land of Canaan.

A German hog butcher named Knochenbauer had settled it in 1798. He’d entered into common-law marriage with an Indian woman and they’d raised children and grandchildren and made their surname Bonecutter. The Bonecutters lived on these five hundred West Virginia acres for 150 years. They were hard, proud people who prospered some times and went hungry others. They witnessed love and murder, fire and flood, until only two remained. It was left to them to hold on to the land. They did so with the sure grip that hill people possess.

Loyal Ledford came to this place in 1948, and for a time people again walked the ground. They followed paths beaten by the feet of those who’d walked the same routes before them. House to church to meeting hall to woods’ edge, and back to house. The people here made something real and good. They built with their hands. They put down roots. Ledford put his in deep. But his blood carried memories and his temper ran hot. In his dreams, hollows were flooded and people hid in holes they’d dug in the ground.

Ledford was apart from this world, and yet the people followed him. “Tell you what,” he once said to them. “We can stir the creek and wake up the trees. We can be a people freed.”

I A Line in the Dirt (#ulink_d29e52e7-5986-5b3d-97bc-00ad036113f4)

October 1941 (#ulink_31938800-c558-59a7-a8dd-1db33da8eb60)

SIX BRICK CHIMNEY STACKS stood at a hundred feet each. This was the Mann Glass Company, a ten-acre factory tract straddling the C&O Line at Huntington’s western edge. Machine-made wide- and narrow-mouth bottles had been blown inside since 1915, and later, prescription and proprietary bottles. Eli Mann had opened the doors of a handblown specialty shop here in 1908. Now, at ninety, he owned a factory with one thousand employees and two 300-ton furnaces.

Inside, Loyal Ledford worked the swing shift, four to midnight. He’d done so since graduating high school in June, and before him, his father had done the same.

Ledford was a long, sturdy young man with big hands. At thirteen, he was a Mann Glass batch boy. At eighteen, he bid on and got his job as furnace tender. It suited him. He was careful to respect the fire, as heat will sometimes break even a young man down. Inside a glass factory, a furnace roared at 3,000 degrees.

Ledford squinted hard. Checked the gauge and eyeballed the furnace fire one last time through the barrier window. As was his custom at the end of a shift, Ledford stared at the fire until his peripherals went white. Then he closed his eyes and watched the little swirls dance across the black stage of his eyelids. He pushed his scoop shovel into the corner with his boot tip and walked blind down the dark east aisle. The wall bulbs had surged again. Popped open like fireworks, muted by the rest of the racket inside. Ledford clocked off at a minute past midnight.

Saturday turned into Sunday, and Ledford sat alone in the dark in front of his work locker. The sweat sheen on his body dried up. His wetcollared shirt turned cold and stuck to him. He coughed. Pulled off his split-leather work gloves. They rode high, all the way to the elbows.

Inside the factory cafeteria, Ledford looked for Rachel. She was the plant nurse on the four-to-midnight shift, and they’d been eating together for two months. Rachel’s mother was Mary Ball, formerly Mary Mann, Eli Mann’s daughter. Rachel’s father was Lucius Ball, plant manager.

She was three years Ledford’s senior. She’d grown up easy in a big house on Wiltshire Hill. He’d grown up hard in a little one next to the scrapyard on Thirteenth Street West.

She was easy to spot. Her posture was spike straight and her hair was coal black. Ledford followed her from the milk bin to the table, put his tray down across from hers. “What say, Jean Parker?” he said.

“What say, Pittsburgh,” Rachel answered. They’d had a date to see The Pittsburgh Kid a week prior. After, she told him he looked like Billy Conn, the Pittsburgh Kid himself. He told her she looked like Jean Parker, only younger. They’d kissed.

“Tired?” he asked.

“A little.” She wore a purple flower on the breast of her nurse’s uniform. Her silver watch was loose on her wrist, thin as twine.

“Hungry, I take it.” Ledford cut his steak, as she did hers. They always ate the same meal. Steak, eggs, chocolate cake. It was the second thing he’d noticed about her.

“Did you read about the Navy destroyer? The torpedo attack?” Rachel chewed while she talked, blocked his view with her napkin.

“Off of Iceland? Didn’t sink it though, did they?”

“No.”

She liked to talk about the war raging in Europe and in China. He didn’t. Always, with wars, Ledford had liked to read, not talk. And so he did, in the paper, each day as he ate breakfast before class. But mostly, his reading came by way of books. History books, like the big old red one that had been his father’s. The Growth of the American Republic it was called, and Ledford had read it thrice before enrolling at Marshall College as a history major.

The sound of stacked glass shifting echoed loud from the kitchen. Mack Wells walked past. He was the swing-shift janitor and the only black man at the plant. He nodded to them and they nodded back. Rachel had bandaged his hand the night before. He’d been scorched by a valve exhaust.

“Mack Wells’ wife is pregnant,” Rachel said.

“How do you know?”

“He told me while I wrapped his hand. She’s due at springtime.”

“Is that right?” He shook hot sauce onto his eggs. “Yes.” She’d stopped chewing and clasped her hands together on the table. “I think springtime is the finest of the seasons for a baby, don’t you?”

“I don’t know.” He didn’t look up at her. His pinbone sirloin was cut to gristle.

“What season were you born? I know you’ve told me, but I’ve forgotten.”

“July the eighth,” he said. He looked over at Mack Wells, who sat alone, his back to them. A line of sweat traced the spine of his coveralls.

“A summer baby,” Rachel said. “Your mother must have hated carrying that weight in the heat.”

Rachel wanted to get married and she wanted to have a baby. Sometimes, she talked in ways that betrayed those facts. But when it went quiet, as now, she quit her talking and let it lie. They didn’t yet speak on serious things. She hadn’t told him of her mother’s cancer, and she knew not to ask much on his family, his boyhood. He’d asked her on their first date if she knew what had happened to his mother and father, his older brother. Yes, she’d answered. “Well,” Ledford had told her, “good. We don’t have to talk about it then.”

By all accounts, Bill Ledford had been a good husband and father, a baseball star and a glassblower from Mingo County who gave what he could to his wife and children and gave the rest to the bartender and the bootlegger.

In August of 1935, Bill Ledford killed his wife and oldest son when he fell asleep drunk at the wheel of his Model A Pickup. Young Loyal had liked a hard wind, and so he rode in the bed. His brother preferred the warm space between his parents in the closed cab. One boy was thrown free and one wasn’t. Loyal was thirteen when it happened. Eli Mann, his father’s old boss, promptly bought the Ledford home from the bank. He told them keep their mouths shut about it, and he told the same to people poking around about the boy who lived there alone. Eli Mann gave Ledford a job, something to get up for every morning.

Ledford picked up the bone he’d been staring at and gnawed it. Rachel had walked away. She bussed her tray and approached Mack Wells, who stood and said, “Miz Ball.”

“No need to get up, I just wanted to check on that hand.”

“It’s just fine. That salve done the trick.”

She told him to change the dressing when he got home, and then she came back over to Ledford.

“You eat like a caveman,” she said.

“You chew with your mouth open.”

She smiled and her eyelids got heavy. Ledford wiped his mouth and loosed a cigarette from its pack. The matchbook was damp with sweat, and it took four swipes to flame.

“I can make us a pot of coffee,” Rachel said. She had a new apartment on Eleventh Avenue. Lucius Ball had wanted her to stay under his roof, but after nursing school and a couple of Mann paychecks, she’d packed her things.

“Watered down or thick?” he asked.

She watched him through the smoke. Everything about Ledford seemed older than he was. “I bought a percolator just yesterday, and I’ll make it any way you like.”

He winked.

Outside, the rain was picking up. It beat a chorus on the roof above them, and the people eating raised their voices to hear one another, and the dishwashers slept standing up.

LEDFORD STOOD IN the entryway of the small apartment. He hung his wet coat and watched as she walked away barefoot on the hardwood. The place smelled of women’s powders and hand cream. Such a scent reminded him of his mother’s room and the small cracked mirror she sat in front of all those years before. Putting her face on, she called it. As a boy, he’d sneak up behind her when she sat in front of her mirror. But she always heard him and scooped him into her lap and tickled him. She claimed that the ticklish among us were guilty of crimes. Over his laughter, she’d ask, “You been stealin sugar, sweetie?” and then she’d hug him to her neck, and all was still and safe.

Rachel brought him a hand towel to pat dry. It was fancy, monogram-stitched, and Ledford hated to use it. She turned from him again and walked past the sofa to the kitchen. “Should I take off my shoes?” he hollered.

“If you want to,” she said.

He did not. He walked to the fireplace mantel and studied the photographs there. They were lined up for the length of it. They told a story. Babies dressed in christening gowns and men with sly grins and bunnyeared fingers behind the heads of their gentle wives.

“Do you like music?” Rachel asked him. She’d started the percolator and was crouching at the cabinet beside him.

“I reckon.”

Her Philco had a phonograph right on top. She pulled a record from the cabinet and set the needle down. “Do you like Claude Thornhill?”

“Never heard of the man,” he said. Piano keys tinkled soft over the quiet hum of clarinets. Ledford’s neck and ears were getting hot.

When the horns came in, he nearly jumped out of his socks. She laughed at him, brought her hand to her mouth to stifle it. He rested his elbow on the mantle, knocking over two framed photographs. When he went to fix them, Rachel grabbed his hands in hers. “Do you want to dance with me?” she asked.

“Yes.”

When she laid her head against his chest, it seemed to Rachel that she’d danced with Ledford a hundred times before.

Ledford was trying not to upchuck his steak and eggs and chocolate cake. He’d not held a woman the likes of this one before.

“Do you know what this song is called?”

He opened his mouth to answer, but only swallowed instead.

“It’s called ‘Snowfall,’ ” Rachel told him. They swayed. He looked at her hand in his, then down the length of her.

Barefoot in her nurse’s uniform, she was the most beautiful thing he’d ever beheld.

November 1941 (#ulink_e031a77d-6ad7-527a-8761-29d8e368e856)

THE CLASS WAS CALLED “History of the Revolutionary War,” and its professor was dull as drizzle on a windowpane. Inside the lecture hall, Ledford sat back row left. Try as he might, he could not stay awake. Swing shift will do that to a man.

Those who surrounded him were not of his kind. They were the variety of young people who, when they got smart-lipped in high school, Ledford had punched in the mouth. Young men wore neckties and argyle sweaters. Young women wore their boyfriends’ jackets and spoke in tongues of Alpha and Omicron and Pi. When these students left the lecture hall, it was in groups of eight or more, hip to hip and laughing astride the downed top of a deluxe V-8 convertible. They drank beer.

Ledford walked alone from campus to Mann Glass, and if he drank, it was going to be whiskey.

But he’d long since decided not to go bad to the bottle, and truth be told, he liked his routine. Ledford had learned early to exist without friends, and his work and school schedules, though they’d run an average man down, gave him much-needed purpose. Besides, he liked glass. Especially in its molten form. To watch the stuff glow and channel outward from a 300-ton pot was a sight. He’d once watched his father, a real free-blower, puff up and shape that very material, and he remembered what he’d been told. “Glass ain’t nothing but the earth under your brogans, boy.” As his father had said this, he gripped his blowpipe in one hand and his punty rod in the other. He set them aside and scored a hot green ashtray with his dogleg jackknife. “That there is sand, limestone, and ash,” he’d said.

Back in front of the furnace, Ledford watched the gauge needle blur and wobble. He smacked himself to stay alert. Late nights with Rachel were catching up to him.

There was a sting at the base of his neck. He turned to find Lucius Ball before him in black safety goggles. “You want little babies to starve?” Lucius asked. Spittle flew. Landed on Ledford’s cheek where the heat evaporated it.

“How’s that?”

“Baby food jars. Isn’t that what we make here son?” Sweat ran from the crease of Lucius’s double chin, and his hair tonic smelled sour.

“I reckon it’s one of the things we make, Mr. Ball.”

“You can bet your last bits on that. And if that fire isn’t tended right, then we don’t stay on top of that quota board, do we son?” Lucius Ball liked to ask questions and not wait for answers. “This plant outproduces Los Angeles and Oakland, did you know that? Did you know we outproduce Waco, Texas? I bet you didn’t. I bet you take your eyes off the fire just as regular as you please.”

It wasn’t about the fire. It was about Rachel. The man neither cared for nor understood his daughter’s suitor, and he made no effort to hide it. Lucius Ball was an angry, greedy man. His father-in-law, the head honcho, was dying, and now it seemed that his wife Mary was dying too, unless they’d cut out all the cancer this time.

Lucius didn’t like to look the young man in the eyes. Something was there that made him uneasy. He stuck his hands in his pockets and looked at the floor.

Ledford turned and tended the furnace.

When he turned back around, Lucius Ball had walked to the flow line, where Mack Wells had apparently missed a spot sweeping. Mack got an earful on dust and its potential to wreck all that is good and mechanized inside a factory’s beating heart. Lucius walked away, shaking his head.

Ledford hollered for Mack Wells to come over. When he got there, Ledford said, “I bet I can guess what he told you.”

“Man says the same things every week,” Mack said.

“Gave me a new one today. I reckon he used the same on you.”

Wells pulled out his handkerchief and blew. “Dust take the durable out of duraglass?”

“No, but I like that one,” Ledford said. Behind him, a batch boy pushed a hand truck loaded with broken glass. Its peak rose from the stacked gallon buckets, cranberry-colored. Ledford said, “Son of a bitch told me if I take my eyes off the furnace, the little babies’ll starve.”

Mack Wells smiled and nodded. “Suppose he thinks there wasn’t no food fit for babies before the jar.” He wiped the back of his neck with the handkerchief. Ledford did the same with his glove, sulfur streaks left behind. Down the line, an operator screamed at a machine boy.

Ledford wanted to tell Mack congratulations on his wife’s pregnancy, but didn’t. They stood awkwardly for a moment, then nodded and went back to work.

Operators sulphured the blanks. Corrugators steamed the paper. Shippers stacked the boxes. Everywhere were hisses and clangs, roars and thuds. And Ledford wiped at his sweat and thought of his history professor and the way he stood silent in front of them all, waiting for an answer to questions like, “What percentage of colonists backed the Crown?” And Ledford thought of Rachel, and how no one but him knew that she’d kiss a man on the mouth after only four dates, that she’d invite a man over after five.

He eyeballed the temperature gauge. He eyeballed the clock on the wall. He knew he was meant for something other than this.

December 1941 (#ulink_c4cf1d34-cec6-53ab-a9c1-d638d0ae1b66)

RACHEL WATCHED HIM PACE back and forth in front of the fireplace. Once in a while, he’d stop and stoke the embers, but mostly he checked his wristwatch.

She couldn’t remember the last time she’d had a fire going in the middle of the day.

On the Philco, a man told any ladies listening that Lava soap would get their extra-dirty hands shades whiter in only twenty seconds.

Outside, a car engine roared, then cut out. Ledford could tell it was Lucius Ball’s Lincoln Zephyr, but he walked to the window anyway. “Your daddy,” he said.

“Well, what’s he doing here?”

“I don’t know.” He walked to the kitchen and opened the refrigerator. He closed it without having gotten anything, came back to the living room, and said, “But he’d better not talk over this broadcast. So help me, if he interrupts the president—”

The doorknob turned and in came Lucius. He took off his fedora and brushed at the snow before he acknowledged either of them. Then the same with his overcoat. When he’d hung everything up and slapped his driving gloves against the end table to announce his presence, he shot his cuffs and said, “Let’s see what old Roosevelt’s got to say on this one.”

Ledford walked back to the kitchen and stared inside the refrigerator some more.

“Shouldn’t you be in bed Ledford?” Lucius Ball hollered. “Aren’t you on the clock in three hours?”

When the broadcast started, Rachel turned the volume knob as high as she ever had. She sat back down on the sofa with her knees pulled to her chest. Ledford poked at the fire, and Lucius stood with his arms crossed. His nose ran, and he sniffed hard every ten seconds.

The president’s words were carefully chosen, and his voice carried vengeance and sorrow. The three in the small room were as still as the congressmen who watched their man before them. There was a cough through the radio’s grate. There was a pop from the wet hickory in the fire.

Then Roosevelt said, “Always will our whole nation remember the character of the onslaught against us.” Something had moved inside Ledford’s gut, and now it surged upward as the congressmen beat their hands together like they never had as one. “No matter how long it may take to overcome this premeditated invasion,” Roosevelt went on, “the American people in their righ teous might will win through to absolute victory.” The roar from the Philco caused Rachel’s eyes to tear, and her heart seemed, for a moment, to stop.

She knew before looking at him that Ledford was gone from her.

He hung the poker on the cast iron holder and slowly turned. His teeth were grit behind his lips and his nostrils flared wide. He looked to Lucius, who was dumbstruck, unable for once to speak his mind. “Mr. Ball,” Ledford said, “I quit.”

He put on his coat and told Rachel he’d ring her later. With his hand on the knob to leave, he stopped. She was crying on the sofa. Her father did not console her. He’d walked to the window and was watching the snow fall. It had picked up since earlier.

Ledford stood in the doorway and thought of their dance. Their song. He spoke her name and she looked up at him. He winked and was gone.

August 1942 (#ulink_8030eba6-fa64-5025-b246-4f498b471bf9)

HE HAD JOINED THE Marine Corps.

On December 10th, Ledford had walked into the recruiting station with a birth certificate altered by a Mann Glass secretary for a fee of five dollars. In the station’s filthy bathroom he’d pissed in a test tube. Passed his physical. He was sent to Parris Island, South Carolina, where he found the weather utterly suitable to his demeanor. He watched the ocean any chance he got. He followed every syllable his drill instructor spat at him, as if the man was God himself. Ledford thrived on discipline. He got a reputation as a hard charger who didn’t shoot the breeze.

When the men were issued their 782 gear, Ledford felt that old, joyous feeling from childhood Christmases. He loved his M1, and in no time he could fieldstrip and reassemble it like most never would. He grew to love the strain of calisthenics, whether at 0500 or midnight under floodlights. Drills became second nature. Hand-to-hand combat with short blades, plunging fixed bayonets into dummies—these acts were honed to reflex.

Ledford earned the designation of Sharpshooter on the rifle range. Even at five hundred yards, his targets came back Swiss cheese.

He smoked and played hearts with the other men, finding a peace in card playing he’d never lose. He traded insults, dimes, and nickels most often with a hard Mac from Chicago named Erminio Bacigalupo.

Erm, they called him. Nobody could tell whether Ledford and Erm liked or hated each other. In truth, neither could the young men themselves.

Ledford wrote to Rachel twice a week.

Nights, he slept like the dead.

Once, drunk on his ass against the barracks wall, Ledford’s drill instructor, an old Devil Dog from Alabama, had let his guard down. He’d seen action in the Great War. “Enemy’ll break, but only if you cut him,” he said. Ledford and Erm were the only men in listening distance. “My CO taught me that. What you do is git inside their tent while they sleep in, cut one’s thoat and leave the other one to find him at sunup.” His words ran together. His eyes might have welled up. “Must’ve done four or five Kraut boys thataway at Belleau Wood.” He fell asleep, then woke up. He looked at Ledford and Erm like he’d never seen them before. “Take a picture, why don’t you, you sons of a fuckin whore,” he said. “It’ll last longer.”

In May, Ledford had boarded a troop train to San Francisco and seen the sights and then walked up the zigzag incline of the ten-thousand-ton transport ship. Aboard the Navy’s vessel, sleep came interrupted, just as it would in New Zealand and in Fiji. A knot formed in the intestines. On August 7th, that knot came up the windpipe and nearly choked Ledford as he jumped over the side of the landing craft into the surf. He waded to the mud-colored sand of what they were calling Beach Red. He crossed it at a jog with the rest of his battalion. They could scarcely believe the quiet. It unsettled Ledford, and as he came to the jungle’s edge, the knot broke loose, and he threw up the smallest bit of bile before swallowing it down again.

Back on the beach, palm trees grew as high as Mann Glass chimney stacks. They curled like fingers, waving the men inland with the wind.

This was Guadalcanal. The enemy was not to be found. Only silence. And in that silence, Ledford finally felt the weight of the last six months. He knew now what that time meant, what it had amounted to. Ledford was not Ledford any longer. He was just another Mac with an M1, First Marine Division, First Raider Battalion, B Company.

Nothing would ever be the same again.

MEN SAT SHIRTLESS, their backs against the vertical wood slats of the pagoda. Henderson Field was a flat, hot wasteland of a place. A wide cut airstrip in the middle of a jungled Pacific island. Nervous Marines walked around the pagoda, looking sideways at those without a helmet or a shirt, those able to enjoy their smokes and never look at the sky above them or the choked forest on all sides.

Like every other Marine, Ledford had become convinced that the Navy had left them on the island to die, that food and ammunition would never again be ample. By day, he repaired bomb craters left in the airstrip’s grass and dirt runways. He leaned on his shovel and smoked and shot the breeze. He looked at that camelback ridge of mountains in the distance. From far off, it reminded him of home. But at night, in the jungle camp, the mosquitoes reminded him of where he truly was, and so did the Japanese fliers in the blackness overhead, dropping 250-pound bombs within spitting distance.

It was a Tuesday. Lunchtime with rations running short. Ledford slept alone on the dirt with his helmet over his face. He was dog tired and bug-bitten, from inside his ears to between his toes. He sat up, took out his Ka-Bar, and cleaned his fingernails. A skinny boy with a pitiful beard walked over from the shade of the pagoda’s overhang. “Ledford? You tryin to fry yourself?” His name was McDonough and he was from Chalmette, Louisiana.

Ledford didn’t answer or look up from his fingernails.

“You want to get somethin to eat?” McDonough blinked his eyes at two-second intervals. He was seventeen years old.

“I’ll eat with you, McDonough,” Ledford said, “if you promise not to talk with your mouth full.”

But McDonough was one of the nervous ones, and when they sat down inside, he talked with his mouth full of canned fish and rice for ten minutes straight. “Ain’t had that sinus infection a day since maneuvers in Fiji,” he said, after chronicling his lifelong battle with a clogged nose and headaches. “It’s like I been waiting my whole life to come breathe this air in the Pacific.”

Ledford didn’t even nod to show he was listening. At that moment, it seemed he’d do most anything to have steak and cake instead of fish and rice.

“My mother said I got the bad sinuses from her, and she got them from her daddy, and so on and so forth, back to my great grandfather, who stuck an old rotary drill up his nosehole one day and had at it until he killed hisself trying to unclog all of it.”

Ledford laughed a little with his mouth full of rice, but then he stopped, thinking such laughter might disrespect the dead.

“It’s all right,” McDonough told him, smiling. “It’s a story meant to be funny. But it is true.” He held up his hand to signify Scout’s honor or stack of Bibles both.

Ledford liked McDonough.

Back at camp that night, he looked over at the boy before lights-out. McDonough was flat on his bedding, looking up at the tent’s sagging roof. The rain that pelted there came harder and harder until the sound of it drowned all others. A roaring quiet. A rain not seen or heard by any American boy before, even one like McDonough, a boy from the land of the hurricane. He just lay there, his finger stuck up his nose so far it almost disappeared.

Ledford thought of Mann Glass and Rachel. Of steak and eggs and the sound of West Virginia rain on the cafeteria tin roof. His chest ached. His gut burned. A drip from the tent’s center point landed on his Adam’s apple. He stared up at its source, a tiny slit at the pinnacle. The rain roared louder, its amplitude unsettling. Ledford opened his mouth and called out, “Gully warsher boys,” but no one could hear him. He turned his head and watched McDonough dig for gold a while longer, then fell off to sleep.

In his dreams, there came a memory. He was a boy, and he fished on a lake with his daddy. The two of them sat in a rowboat, oars asleep in their locks, their handles angled at the sky. Father and son bent over their casting rods and spoke not a word. There was only stillness and silhouette, quiet as a field stump.

Twice Ledford was awakened by the sound of Japanese Zeros zipping overhead. The rain let up. The bombs came down. He jolted when they hit, and in between, he wondered about the dream. He could not remember any lake near Huntington, nor could he remember ever fishing with his daddy. And the quiet. Why had it been so quiet?

In the morning, the men waded through calf-high water outside the tents. It had gathered in the middle of camp, channeling the makeshift road they’d fashioned. Oil barrels floated by on their sides. A dead spider the size of a hamburger spun slowly, emitting little rings of ripples as it went. McDonough ran from it, got himself to higher ground at the muddy base of a giant palm tree. He had a deathly fear of spiders. The men laughed and pointed at McDonough, who, like many of them, had gotten the dysentery bad. The sprint from the spider had stirred things inside him, and he dropped his trousers right there at the base of the tree and let rip.

It was a sight. Ledford laughed heartily and shared a smoke with Erm from Chicago, who told him, “You think that’s funny, just wait till the malaria eats him up.”

September 1942 (#ulink_b738d6a5-2a5b-54bb-b8f6-f83da0364ddb)

THE RATIONS HAD GROWN a pelt of mold. Nightfall had come to resemble a wake, the men’s mood shifting with sundown to gloom and the inevitability of death. Fever shivers gripped more than half, and on that Monday, orders came down that they all swallow Atabrine at chow time. Some said it would turn men yellow.

Saturday found them on the ridge Ledford had admired from a distance. Camel Ridge, some were calling it. They had no way of knowing that its name would soon change, and that the new name would be one they could never forget.

Bloody Ridge was high and steep.

They’d scampered through the jungle and then the ravines, on up through the head-high kunai grass that clung to the slopes, thick and tooth-edged. It sliced men’s fingers and stung like fire. But they’d been told that the ridge would provide ease, a place away from the airstrip bombings.

Ledford’s platoon dug in at the crest of a knoll. He and McDonough and a fellow named Skutt from Kentucky shoveled a three-man foxhole quick and quiet. Skutt got low, on his knees, and cut a shelf inside. He took a photograph of his daughter from his coverall breast pocket, set it gingerly on the ledge. He smoothed the dirt away from it with his bloody fingers. The girl was no more than two, fat like a little one should be. There was water damage at the corner, so that her stiff white walkers bubbled up at the ankle. Skutt licked his thumb and smoothed it.

“That your little one?” Ledford asked.

“That’s my Gayle.”

“She a springtime baby?” Saying those words nearly caused Ledford to smile.

“Summer.” Skutt coughed. Once he started, he couldn’t stop, and it became irritating in a hurry. The foxhole’s quarters were tight. McDonough seemed to wince at every sound.

Night came, and with it the air-raid alarm. Bettys and Zeros filled the sky above the ridge, and they littered the hillside with daisy cutters. At first, it didn’t seem real. The airstrip bombings had been one thing, but in this new spot, the feeling of exposure was almost too much. The earth quivered. The nostrils burned.

Ledford pressed his back against the foxhole’s bottom and dropped his helmet over his face. Beside him, McDonough did the same. They waited.

But such waiting can seem endless inside all that noise, and some men can’t keep still. After a time, Skutt leaped from them and ran, screaming, maybe firing his weapon, maybe not. He was cut to pieces.

When the raid was over, they surveyed the dead and wounded. All but two were beyond repair. Skutt was splintered lengthwise, groin to neck. Ledford’s insides lurched. He turned back to the foxhole. He saw the picture of the baby girl on the dirt shelf. Somehow, she hadn’t blown over.

The Marines were pulling back to the southern crest now, digging in there for more. Holding position.

Ledford looked at the picture again and left it where it sat. He followed.

JAPANESE FLARES WITH strange tints lit the sky overhead. Underneath, the enemy scampered ridgelines, closing quick on freshly dug Marine fox-holes, where grenades were handed out, one to a man. Bayonets were at the ready. Brownings ripped through belts of ammo, humming hot and illuminating machine-gunner faces locked in panic or madness or calm. Mortars made confused landings, and everywhere, men screamed and cursed, and many of them, for the first time, truly wanted nothing more than to kill those they faced down.

Ledford wanted it. He bit through the tip of his tongue. He hollered and swallowed his own blood and stood and lobbed his grenade at the onslaught. Then he sat back down inside the hole. McDonough panted hard and followed suit.

After a while, Ledford climbed out again and got low. He set the butt of his rifle to his shoulder and looped the sling around opposite arm. Bellied down and zeroed in, he watched under the glow of a flare as a thin Japanese soldier ran across the ridgeline ahead. Ledford led him a little, shut an eye, and squeezed. The man buckled sharp, like a rat trap closing, and a black silhouette of blood pumped upward. Immediately, a hot sensation flooded Ledford from head to belly. A wave of sickness. A swarm of stinging blood in the vessels. He rolled back into his hole. His head lolled loose on his shoulders and he lurched twice. Killing a man had not been what he’d anticipated. “God oh God,” he said. “God oh God.”

SUNDAY-MORNING DAY BREAK BROUGHT the battle to its end. The Marines had held. Their horseshoe line bent but never broke.

Ledford walked the ridge with McDonough at his side. Neither spoke. They looked at the bodies covering the ground like a crust. Hundreds of them. Nearly all had bloated in the sun. Their eyes were open, glazed, burning yellow-white in their staredown with the sky. Some of their faces had gone red. Others were purple or a strange green-black. The smell was too much for McDonough. He cried to himself and covered his face with a handkerchief and muttered about his sinuses, blaming everything on his bad pipes. Ledford tried not to breathe. He felt for the boy from Louisiana. This was too much for him to bear. He’d known it since McDonough had pissed himself in the foxhole. The smell had gotten bad, and McDonough had apologized. Ledford had told him, “You’ve got nothing to be sorry for.” He’d vowed in his mind to watch over the boy.

TWO WEEKS LATER , Ledford watched McDonough climb the sandbar west of the Matanikau River. The boy turned back to stare at the water’s surface, suddenly wave-white, alive with the plunk and stir of hand grenades, mortars kicking mud. He looked Ledford in the eyes, confused, and then his face exploded. His body sat itself down on the embankment, almost like he still had control of it and had decided to rest his legs. McDonough rolled the length of the embankment into the water and bobbed there, knocking against a tree root that had caught the collar of his coverall.

After that, when Ledford went flat on his bedding at night, he saw it: McDonough’s confused face and the way it was instantly changed into something no longer a face, into something Ledford’s brain could barely comprehend. His memory held no pictures such as this one. The only thing that came close was a sight he’d beheld as a boy. He’d come upon his father on the front porch, the dog whimpering and held off the ground by the scruff of its neck. His father swung a switch at the dog’s backside, just as if it was a boy who’d done wrong. At the corner of the porch, where the chipped floorboards came together, sat a heap of ruined leather. His father’s white buckskin mitt lay there, mauled almost unrecognizable. He’d kept it oiled regular since his time in the Blue Ridge League in 1915. Now the dog had gotten a hold of it and it was ragged-edged and wet and ripped from the inside out. Same as McDonough’s face.

Ledford played a little game with his brain for six straight nights in late September of 1942. The game played out on the backs of his eyelids, where the furnace fires had set his mind on visions. Now he’d lay down, shut his eyes, and here would come McDonough’s ragged-edged noface and his daddy’s exploded buckskin mitt and the squeal of the dog and the crack of the switch on short-haired hide. All of it would amplify against those eyelids until it became so loud that Ledford could not be still. He’d open his eyes and the sounds would quiet. But no man can hold open his eyes forever, and when they closed again, Ledford’s heart beat against his breastplate double-time, and he sat up bone straight for fear his own mind and body were killing him. On it would go like this until he got up from his bunk and swallowed sufficiently from his own pint or somebody else’s. Whiskey was the only thing to save him.

Erm Bacigalupo had won enough poker hands to own what little liquor the men had left. Some of it was Navy-smuggled, some of it was swiped from bombed-out Japanese camps. Either way, Ledford owed Erm for liquor. It was all written down on paper scraps Erm kept in his cigarette tin.

On the seventh night, the whiskey finally killed the pictures and howls in Ledford’s head. Rendered them temporarily gone.

He woke up the next day a new man. His voice had changed, gotten deeper. There was a whistle in his left ear. But from that morning on, Ledford was no longer visited by McDonough’s exploding face.

In the days to come, he saw other men suffer similar fates to McDonough’s. The enemy took to staking American heads on sharpened bamboo poles. It wasn’t long before a Marine returned the favor.

After a time, Ledford found a quiet space inside the whiskey bottle. It was the same place his daddy had once found.

Ledford listened to the woods. He watched the treetops sway. He slept easy and ate well.

Rachel’s letters saved him. He could get a hard-on just picturing the pen in her hand, moving across the paper he now held. I love you, she wrote, and he wrote it back.

October 1942 (#ulink_fa3e62eb-0b6a-56e8-acca-525a6e6b1e97)

HE AWOKE IN HIS foxhole at 0300 hours. It was black and quiet. The dreams had visited him again, but already they were gone. At the mouth of his hole, Erm crouched, smoking a cigarette. “Let’s go,” he said.

Ledford stood. He slugged hard from Erm’s flask.

In front of him, Erm covered ground in silence. They put five miles behind them at a quick clip. Stopped, breathed, slugged the flask. Tucked themselves into the ridge folds west of the Bonegi and crept, then belly-crawled toward a small camp of sleeping Japanese. The rain beat in torrents. Its sound allowed them to move unheard. Its curtain allowed them to advance unseen. Single-file, they belly-crawled, stopping now and then to survey. Each gripped his .45. The mud sucked at their bellies and hips and knees.

Behind the enemy’s line, Erm looked for sleeping pairs.

He found two such men tucked inside a makeshift tent of bamboo shoots and canvas. He peeked inside the open flap, then signaled for Ledford to stand watch. Erm slipped inside. Ledford kept his head on a swivel, once or twice glancing at the sleeping men inside. Each had dropped off while eating a tin of rice, now emptied and atop their chests. Ledford watched the slow rise and fall. He listened to the snore, recognized the exhaustion. The rain kept up. There was no sign of movement on the perimeter. Erm reached from the tent and tapped his shoulder. Your knife, he mouthed. Ledford holstered his .45 and fished the dogleg jackknife from his breast pocket. It had been his father’s before him. Pearl-handled and well made. Thackery 1 of 10 etched by hand on the flat. He’d spent hours honing the bevel on a pocket stone.

Ledford watched Erm crawl between the two men. One of them wore a thin mustache, the other was clean-shaven. They were rail thin. Young as McDonough. Ledford looked at the lids of their closed eyes, barely discernible in the low glow of their lantern, its oil nearly spent. He watched the eyeballs rolling wildly underneath. It was deep sleep. Dream sleep. He wondered for a moment what haunted these men, and then he watched Erm looking from one to the other and back. He chose the one on the left, put his hand over his mouth and drove the jackknife into his jugular vein, pulling it across the throat with all the muscle his forearm could muster. Blood came fast and heavy, surging in time with the young man’s heart. Erm waited out the few soft gurgles, his eye on the other soldier, who continued to snore. He wiped the blade across the dead man’s still chest, one side and then the next, so that it made a red X next to the empty rice ration. He folded the blade shut and handed it to Ledford.

They left the tent and maneuvered back to blackness. On their way, Ledford considered the young soldier they’d left alive. He envisioned him stretching awake come morning, wiping the sleep from his eyes and turning to face his comrade. What horror the young man would experience—what confused detriment to arise to such a sight. This type of warfare could not be measured. It was more than payback for McDonough, more than putting a chopped head on a stick. More than taking a father forever from a baby girl whose picture he carried. This was what their drill instructor back in boot had told them would win wars. The man had sat in earshot until daybreak just to hear the screams of German boys echoing across the French forest. The awful screams. “Nothing like it for defeatin the enemy,” he’d told them. That was so long ago now. Now here he was.

Before him, Erm walked in silence and thought of his cigarettes, dry inside a tin in his foxhole.

Ledford trailed behind. The jackknife jostled in his breast pocket as he walked. He thought of his father scoring glass.

He wondered how he’d come to follow such a man as Erm.

Rain beat his shoulders numb. Its sound was everything.

ON ASATURDAY, in front of the pagoda at Henderson Field, Erm Bacigalupo said something he shouldn’t have. What followed would confuse every eyewitness, for it showed them that in wartime, friends and enemies are difficult to discern.

Erm enjoyed messing with those he deemed “country.” It was a hundred-degree afternoon, the last day of October, and Erm had picked a heavyset seventeen-year-old from Mississippi who’d just sailed over from Samoa with the Eighth Regiment. Three men sat on the skinny bench against the front wall, watching Erm size up the new boy. He up-and-downed his utility uniform, fresh-issued. “Look at the sharp dresser,” Erm said, fingering the coat’s buttons. Like everybody else, he knew the boy only wore the coat to hide his baby fat, and Erm wanted him to take it off so he could make his life more miserable than it already was. “Look at the buttons on this thing. Anybody told you about the copper pawn, Country?”

“Huh-uh.” The pits of the coat were sweated straight through in circles the size of a phonograph record.

Ledford was under the pagoda’s corner, his reading spot. He closed his Bible and slid out. The Bible’s bookmark was a letter he’d gotten from Rachel that morning. Eli Mann, her grandfather, was dead at ninety-one.

Ledford propped his elbow on the dirt and watched the men on the porch.

Erm kept at it. “Copper pawn’ll give you ninety-five cents a button. You know how to get there?”

“Huh-uh.” He tried to remember what he’d been told about this kind of northern talk from this kind of northern man.

“It’s at the top of Mount Austen, but they’re only open from midnight to two a.m.”

Somebody laughed and somebody else told Erm to shut up. Ledford stood up and started to walk inside.

The boy from Mississippi said, “Mount Austin, Texas?” and everybody laughed at him. Ledford looked at the boy’s face, the way it wore a confused, familiar look. He stopped and stood behind Erm.

“This one isn’t even worth it,” Erm said. “This one’s dumber than Sinus.” Sinus was what some of the men had called McDonough, as he never shut up about his sinus problems. “You watch out, Country,” Erm said, tearing the copper buttons off the boy’s coat one by one. “Sinus ended up on a Jap spit with an apple stuck where his mouth used to be.” All but one of the men quit laughing. Erm stuck the buttons in his pocket and turned to the two still seated. “Old Sinus doesn’t have to worry about his clogged head anymore, does he?” he asked them. “Japs opened it up wide.”

Ledford grabbed Erm by the back of his neck, just as his father had done the dog that day on the porch so long ago. With a fistful of shirtcollar, he lifted the other man an inch or more from the ground and slammed him, face first, into the dirt. Then he took a knee next to the Chicagoan with a smart mouth and rolled him over, blood already thick with dust, front teeth already broken. Ledford raised his fist as high as he could and brought it down square on Erm’s face. He got in two more before they pulled him off, the other man half-asleep and gagging on sharp little pieces of tooth, bitter little rivers of blood.

November 1942 (#ulink_d2ebef7d-d61f-5680-8fec-0f915c1a4644)

IF THERE WERE ANY boys among them, Bloody Ridge and Matanikau had made them men. Bayonet-range fighting will do that, quick. Ledford didn’t worry on the enemy any longer. If he kept an eye open, it was for Erm. The sureness of death’s liberation had sunk in. Someone was coming for him, and it didn’t matter much whether that someone was his comrade or his enemy.

When a man accepts that he will no doubt die, he is free to live.

The pagoda’s shade was cooler. The rice rations tasted better. The whiskey was like drinking the sun.

Ledford grew accustomed to seeing things he’d not imagined stateside. One Marine safety-pinned six enemy ears to his belt. Heads stuck on a pole were not uncommon. Erm had joked of the sight, and now Ledford knew why. It was just another thing to look at while you smoked.

Still, Erm never spoke to or looked at Ledford after having his top teeth knocked out. He didn’t speak much to anyone. He’d developed a noticeable lisp since the fight. The man’s tongue knew not where to go.

Once, he’d gotten excited about a rumor that was spreading. “The division is about to be relieved,” he’d said, lisping all the way. “We’ll be parading in Washington by Christmas.” The next day, his eyes were back to staring blank at nothing, all pupil. Black as jungle mud.

Some said Erm was shooting morphine he’d won in a stud game.

Ledford felt guilty for what he’d done to the hard Mac from Chicago. In some ways, he hated the man, the secret they shared of a maneuver in darkness. In others, he admired him. It crossed Ledford’s mind to apologize, but he couldn’t. He couldn’t speak on much of consequence to anyone in those days of preparation. They were to push the Japanese out of the airstrip’s artillery range.

Ledford found himself uncharacteristically hungover on the morning he marched toward Kokumbona on the heels of an Air Fleet strike. Positions were to have been secured and the movement through the jungle was to have been a safe one, but something was not right. Ledford felt it in his headache and in his bones. He looked at the Marines around him. They felt it too.

It was quiet. Ten yards to his right was Erm Bacigalupo. He looked as though he might vomit. His cheekbones stuck out. His lips were in a pinch.

Then came the hard clap of a single Japanese rifle, and Ledford’s every muscle seized. He dropped and rolled toward a thicket of green, but the noise had got to him this time. A burst of machine-gun fire originated somewhere too close, and then the thump of a mortar shell blew out his eardrums. All was still. Then ringing. His vision went seesaw. He stood, and just before another mortar landed before him, he made eye contact with Erm, who was running in his direction. Then another thump, and then silence. Ledford was aware of hurtling through the air. Something had gone through him, and he lay on his back, touching at a torn spot on his chest. Air emanated to and from this spot. It had gone clear through, and he breathed from it. He was deaf, but he could hear it plain as day, in and out, pfffffffffff-hooooooo. The left shin was also torn, smoking gray wisps and spilling black blood on the ground cover.

The thought came. This is it.

But then a corpsman was there, and he stuck in a shot of morphine. And then there was a stretcher and some movement, and then nothing.

The night ahead was something Ledford would never forget. He lay in a wounded dugout, eight feet deep, at Henderson Field. The heat inside the earth there was too much to take, and the men were packed shoulder to shoulder. They screamed. The smell induced gagging. Ledford tried to keep deaf, but his eardrums were healing. He tried to shut his eyes, but the swirls on the black stage of his eyelids erupted like they never had. His stomach jumped and his throat crawled up his tongue. He breathed through his mouth, labored, like a dog.

Once, before passing out, he turned and saw Erm, three men away from him, his forehead wrapped in bloody gauze. He stared at Ledford, and a corpsman came by and stuck Erm with morphine, and he smiled, toothless.

The next morning they were flown out to a Navy hospital. Espiritu Santo it was called. It was there that Erm said to Ledford, “I told you we’d be home by Christmas for the parade.”

The USS Solace carried the men to New Zealand. On board, an infantryman younger than Ledford cried with joy in his bunk. Everyone ignored him. They all spoke upwards, to the ceiling. Loud. Some perched on an elbow to see their surroundings. It didn’t seem real that they could be out of the jungle.

“Think they’ll have any KJ billboards up back home?” somebody said.

“What’s a KJ billboard?” It was the teary kid. “Ain’t you had your eyes open doggie?” Ledford said. He was drunk and delirious. “Kill Japs, kill Japs, kill more Japs. There’s one plastered across every piece of plywood in the Solomons.”

The kid shivered. Jungle disease was in his blood. “I’m done with killin,” he said. “Japs or no Japs.” He looked down at his shaking fingertips. “I just want my fingernails and hair to start growing again,” he said. As dysentery came, such growing went. The jungle blood could rot you inside out.

“Yeah,” Ledford said. “You’re done with it all right doggie. You go on and turn soft. Let those nails and hair grow real long.”

A couple Marines laughed. Another one said, “Damned pansy Army dogs.”

Erm Bacigalupo said, “Put some panties on while you’re at it and bend over.” Everyone laughed hearty. There was no longer any room for soft. A code needed to be kept. Among men who’d done what they’d all done together, none could ever speak of going soft again. To do so would invite their nightmares to the waking world.

That night, Ledford made his way on crutches to Erm’s bunk. He apologized for knocking his teeth out. “I’m truly sorry for it,” he said. He held out his hand and they shook. Ledford pledged that once stateside, he would buy his friend some new teeth.

August 1945 (#ulink_4858e2e1-040f-5ac8-86d4-7eeffd45c574)

IT WASMONDAY, the sixth. The grandstand at Washington Park Race Track was filled. Elbow to elbow they sat and waited, Southside Chicagoans and out-of-towners together. They’d come for the match race between Busher and Durazna, for which the purse was twenty-five grand.

Under the grandstand overhang, Ledford and Erm swilled from their respective flasks. They studied their short forms in silence. A fat lady in a flowered hat sat down in front of them and Erm made a farting sound. She turned, frowned, and fanned herself with a program. “Excuse you,” Erm said to her. He flashed his smile and winked at her. His teeth were white as ivory, set solid and paid in full. When the woman left to find a more suitable seat, Erm hollered, “Keep fannin honey, you don’t know from hot.” He stood for no reason and wobbled a little on his feet. He sat back down. “Did you see that broad? She was wide as she was tall.”

They were drunk. Had been so for three straight days, nine hours of sleep in total.

“What’s the skinny on Durazna’s trainer?” Ledford said.

Erm didn’t answer. He was eyeballing the suits down front. “Look at these cocksuckers,” he said. “I paid good money for these seats. I gotta look at these silver-haired bastards all day?”

Ledford licked his pencil and drew a circle around the words Oklahoma bred.

“What’s the point in standin? There’s twelve minutes to post, for cryin out loud.” Erm’s ears were turning red. He got like this, and there was no point in trying to stop it. “Look,” he said. “See how they all hold their binoculars with their pinkies out? How much you think they paid for those binoculars?” He stood up again. “Hey, Carnegie. Hey.” The men down front knew not to turn around. They recognized that kind of voice.

“Carnegie came from dirt,” Ledford said. He didn’t look up from his Racing Form.

“What?” Erm thought about sitting back down, but didn’t. He ground peanut husks with the soles of his Florsheims.

“Carnegie came from poor folks. He was a philanthropist.”

“Philanthra-who-in-the-what-now?” Erm cleared his throat and spat on the ground. “Pipe down, college boy.” He kicked popcorn at the empty seatback in front of them and sat down. “Choke those fuckin suits with their binocular straps,” he mumbled.

Ledford said he wanted to go to the paddock and see the horses running in the fourth.

Erm looked at his wristwatch. “You go on,” he said. He’d set up a three-thirty meeting with his uncle and needed to be in his seat.

Down by the paddock, the horseplayers tried to blow their cigarette smoke above the heads of the tourists’ kids. It was hot and drizzly. Undershirt weather. A track made soft by summer rain. Ledford was in the bag and it wasn’t yet three o’clock. He drew another circle around the number nine in his short form, put it up over his head like a rain canopy, and walked inside, away from the paddock. He chewed cutplug tobacco. “Homesick Dynamite Boy,” he said as he walked. It was the name of the number nine horse, and at 7 to 1 it was an overlay if he’d ever seen one. He looked at his short form again. His left shoulder knocked against the side of a pillar, so he sidestepped, and his right shoulder knocked against a man in a black shirt and matching derby hat. There were no Excuse me’s. This was expected. Ledford felt the man’s eyeballs on him as he walked away.

He had a fifty, three twenties, and a ten left in his billfold.

Since the war, Ledford had been lucky at the races. He’d once paid a semester’s tuition with a single day’s payout. Erm had helped him along with tips from men with no names. Ledford didn’t ask questions. He stayed drunk much of the time. He’d finished college and proposed to Rachel and taken a desk job at Mann Glass. His life was a game of forgetting.

Housewives from Homewood were logjamming the betting lines. Ledford chewed the plug hard between his eyeteeth and studied his form while he parted all of them, instinct taking him where he needed to go. He stepped up to the counter and said, “Five dollars to win on the nine.” There was no response.

Ledford looked up. A kid in a green golf hat looked back at him. His voice cracked when he spoke. “This is the popcorn cart,” the kid said.

Ledford tried to recollect the previous half hour of his life. He remembered sitting inside a stall on a toilet that had seen too much action, drinking the last of the bourbon in his pint flask. But, like all memories, this one was a sucker’s bet, because once he was in the bag, time and place were wiped and gone. He ended up wagering on three-year-old geldings at popcorn stands.

“Did you want some popcorn?” the kid asked. A red-rimmed whitehead pimple on his nose threatened to blow wide open of its own accord.

Ledford thumbed at the bills in his hand. The dirt under his nails reminded him of Henderson Field, digging. “I’m a college graduate,” he told the kid, who was getting nervous because the man in front of him was relatively big and radiating alcohol and possessed eyes that had seen some things. “Getting married on Saturday,” Ledford told him. “Beautiful girl.”

He looked at the people going by. So happy. So unaddicted to booze and playing horses. So empty of parasitic memories. A short woman with legs like a shot-putter’s rolled by a handtruck carrying a beer keg. It was held tight with twine. “Hell of an invention, the handtruck,” Ledford said to no one in particular. “Dolly, some call it. Roll three buckets a cullet around with one, no problem.” He watched the stocky woman go, her beer destined for some bubblegum-ass in the VIP Room.

As he walked away from the popcorn stand and the acned teenager who could no longer hold eye contact with him, Ledford’s insides ached. He spat heavy.

He walked to the betting line and made it to the window with one minute to post. “Five dollars to win on the nine,” he said.

He held the ticket between his thumb and forefinger. Kissed it. “Come on, Homesick Dynamite,” he said, wedging himself through the crowd, jackpot sardines with dollar signs in their eyes. Ledford stood tall at the rail and waited.

Homesick Dynamite Boy came out of the clouds on the three- quarter turn only to falter at the wire. He placed by a head length.

Ledford littered his ticket for the stoopers to pick up.

Back at the seats, he was introduced to Erm’s uncle Fiore, a short man with bags under his eyes and a tailored black suit. He had a large associate called Loaf.

“Erm tells me you busted his teeth out,” Uncle Fiore said.

“Yessir,” Ledford said.

“And you’re from Virginia?”

“West Virginia.”

“You like to play the horses?”

“Yessir.”

“All right, son.” For the entirety of this exchange, Uncle Fiore had been grasping Ledford’s hand, looking him hard in the eyes. He finally let go and said, “I’m a patriot, by the way. I got the Governor’s Notice for helping secure the port docks.”

Ledford nodded.

“How’s the shin? Erminio tells me you took some shrapnel bad.”

“It’s healed up fine. Little limp left.”

“Good. Good. My nephew’s brain I’m not so sure about, but that didn’t have nothing to do with the shrapnel.” Erm tapped the scar on his forehead where it spread beneath his hairline. They all laughed, except Loaf the associate. He had his hands crossed in front of him and kept shifting his stance. His feet were too small for his frame. “Anyway, son, you stick with Erminio around the track. He knows a little something about ponies.” Uncle Fiore winked, and his eyebags seemed to disappear for a moment. He embraced his nephew, whispered something to him, and was gone.

Erm convinced Ledford to put everything he had on Busher in the mile race. Both men emptied their wallets, and both men cashed in fourfigure tickets. They walked out of the racetrack feeling as good as two medical discharges living on military pensions could feel.

They hit a nightclub, then Erm’s mother’s place for a meal. In the driveway was an Olds Touring and a red Packard sedan with suicide doors. After she had kissed him six times, called him “country handsome,” and complimented his appetite, Ledford asked Erm’s mother how much she wanted for the Packard. Without missing a beat, she answered, “Five hundred cash for a marrying man.” It was a done deal. Instead of taking the train back to Huntington to be married, Ledford would ride in style.

Before he left the next morning, he phoned Rachel. She sounded tired. “Well, we’re in the money,” he told her. Said he’d be home earlier than planned, and that he had a surprise.

“Me too,” Rachel said. “I’m pregnant.”

Ledford didn’t know whether to howl or have a heart attack. But he smiled, and told her he was doing so. Then he told her he loved her. He meant it.

“A springtime baby,” she said.

“Nice time of year.”

He fired up the Packard and waved goodbye to Mrs. Bacigalupo. In the passenger seat, Erm nodded off within three city blocks. He was coming to West Virginia to be Ledford’s best man.

Crossing the flat expanse of Indiana, there was peace inside the car. Neither of them knew that across the world, the city of Hiroshima had already been erased by the atom bomb. Gone, all of it. One hundred thousand men, women, and children had been evaporated.

The war was nearly over.

* * *

THE RECEPTION’S BUFFET table was as long as a limousine. Folks who’d grown accustomed to rationing during the war lined up to get their fingers greasy. Here was a spread not grown in any victory garden. There was an apple and salami porcupine, chicken livers and bacon, cocktail sausages, dried beef logs, bacon-stuffed olives swimming in dressing, salami sandwiches, shrimp with horseradish, pineapple rounds with bleu cheese pecan centers, roast salmon on the bone, and anchovies with garlic butter. Ledford bit into the last of these and winced. This was partly on account of his toothache, but it was more than that. The little anchovies called to mind those long-forgotten fish-and-rice rations, stolen from the dead hands of the enemy. Ledford swallowed and smiled to a skinny old woman he knew to be Rachel’s kin. He turned from the buffet table and bumped into Lucius Ball, his new father-in-law.

“How do you find the spread?” Lucius asked. His neck fat quivered as he hollered over the trumpet’s blare.

“Plentiful,” Ledford said.

The man had spared little expense to host his only child’s wedding in his own backyard, and he wanted it acknowledged.

Lucius tried to be friendly. He was nervous about the money Eli Mann had left to Mary in his will. Money she’d be doling out in short order. “How’s the leg?” he asked. The band finished a fast Harry James number. They’d only played three songs, but already they pulled their silk handkerchiefs as if choreographed, mopping sweat before the bride and groom’s dance.

“It’s just fine.” Ledford answered. “Excuse me.” He’d spotted Erm talking up a curvy brunette he knew to be fifteen, if that.

Ledford walked away. He didn’t care if it was rude. His father-inlaw was fishing for gratitude, and he wasn’t going to get it. Not so long as he was the way he was. Lucius Ball had never been able to keep his pecker in his pants, not even with a dying wife. Such things had kept right up. Everybody knew of his transgressions, and Lucius didn’t give a damn. And now, the house on the hill was done up in grand fashion for the reception. If the church was dark and humble, this was whitelinen and bulb-light flashy. Ledford had seen too much of nothing to be impressed by so much everything. He looked up at the tent’s ceiling as he walked. There was a rust-colored water stain at the center post. A blemish amidst all that white. It called to mind the hole in his tent at Guadalcanal. That drip against his Adam’s apple. McDonough.

He came up quiet behind Erm and kneed him in the leg. “I see you met Rachel’s cousin Bertie,” Ledford said. “Bertie’s a freshman in high school.”

Erm didn’t care how old she was. He started to say so when the bandleader came over the PA. “About one minute now, if we could gather up the bride and groom.”

Erm’s dress blues had been in a box for three years. It showed. Ledford wore a store-bought black tuxedo, and that morning, when he’d asked his best man why he didn’t do the same, Erm pointed to his brass belt buckle and grabbed his crotch. “Eagles and anchors,” he’d said. “She spreads eagle, I drop anchor.”

Ledford stepped from the crowded tent and looked up at the bedroom window. A light was on.

He nodded hellos and fake-smiled his way through the strangers on the porch, climbed the stairs inside and knocked before opening the door.

Rachel sat on the bed beside her mother, whose complexion was not unlike the white of her old hobnail bedspread. There was a coughedblood stain on the hem of her bedsheet. Underneath, her shoulder and hip bones stuck out like stones.

Both women smiled at him.

In the glow of the table lamp, Rachel looked so tan and young next to her mother. Rachel pulled pins from the bun in her hair. Her veil sat next to a red glass bottle of codeine.

“Crowded down there?” Mary Ball’s voice wasn’t much more than a whisper, but Ledford listened to her every syllable. He’d come to love and respect his new mother-in-law. Once, when he’d come up short on tuition money, she’d stuck a hundred-dollar bill in his shirt pocket and told him, “Any man who takes a degree in history needs a little help.” Then she’d laughed.

There was none of that now. Laughing always brought up the blood.

“Yes ma’am. It’s packed to the tent poles,” he answered. He sat down next to Rachel and took her hand. “They’re calling us for our first dance.”

“Open the window wider,” Mary Ball told them, lifting a bony finger. “I want to hear your song.” Ledford did as she said. She called him back over to the bedside. Looked him in the eye and squeezed his hand. “You do right by Rachel,” she said.

“I will.”

“You don’t ever forget what you’ve promised in marriage.”

“I won’t.”

It worried the old woman that Ledford had no people there, no kin to speak of at all.

At the bottom of the stairs, Rachel wiped her tears before they went back out. She blew her nose and breathed in deep and kissed her man. “I almost told her I was pregnant,” she said.

He nodded. “I think she might know it anyhow.”

“I was thinking the same thing.” She laughed a little. Dusk had gone to dark outside the French doors behind her. Her gown looked almost silver against it. “Still as hot out there?”

He nodded again. Stared at her.

“What?” she said. “Are you drunk?”

“No.” Seeing her in the dress made him nearly as clumsy as the first time he’d gone to her apartment and knocked over picture frames. “Can you dance in those?” He pointed to her high-heeled shoes.

“If I can’t, I’ll take em off.”

Though it wasn’t as good as Claude Thornhill’s orchestra, the band did a nice rendition of “Snowfall,” and Rachel laid her head against Ledford’s chest, and she knew they’d do what they’d pledged to do earlier that day. Richer or poorer. Sickness and health. This was forever. And Ledford looked down at the length of her and smiled at how the wedding gown could just as soon be the nurse’s uniform he’d beheld four years before. For the length of that song, neither of them could see the people stuffing their faces at the buffet table, nor could they see Erm swallowing a highball glass of scotch in one swig, eyes shut, saying to woman after woman what he always said—“How do you do?” Even the white linens and lights and cover of tent that had seemed in excess for a people at war, even these, for the length of that song became nothing more than snow falling all around as they closed their eyes and swayed. It was ninety-two degrees inside the tent, but the newlywed couple had ceased to sweat.

Above them, Rachel’s mother nearly got up and came to the window. She knew better. Instead, she swigged her codeine and moved her fingers to the music and pictured them in her mind, just as they were outside. Her only daughter. The man she’d chosen. So much pain in him, but equal parts strength and virtue. She thought of her own husband, whose small storage of such righ teous qualities had long since disappeared. He’d not been faithful to her, and that was unforgivable. She thought of her last will and testament, the changes she’d made unbeknownst to anyone, and she smiled.

Mary Ball would hang on for another day, long enough to see them off on the honeymoon. Long enough to read in the Sunday paper of a second bomb dropped, this one more powerful than the first. The smile she’d had from the music through her window was no longer. Her mouth wrenched downward at the corners. She mourned for man and wished only that she’d died the night prior. Her focus blurred, eyes shutting down like the rest of her. The last thing she ever saw were the words Nagasaki wiped clean from the earth.

May 1946 (#ulink_249ecc94-f467-5cba-840c-f45660178f73)

LITTLEMARYESTELLELEDFORD squirmed in the crook of her father’s arm. She had gas, and she couldn’t yet pass it with efficiency. Ledford laughed at her grunts, the faces she made. Her eyebrow hairs were fine but dark and nearly connected to the hairline at her temples. He kissed her face all over. He sang to her a song that his mother had sung to him. Was an old mouse that lived on the hill, mm-hmmm. He was rough and tough like Buffalo Bill, mm-hmmm.

Rachel walked in from the kitchen. She eyeballed the beer bottle on the end table. Wondered how many he’d had. The throw rug under his feet stretched and tore with each step of the made-up dance he did with his infant girl. Their home was new, but their furnishings weren’t.

Lucius Ball had gotten to keep his home after Mary died, but that was all he’d gotten.

As it turned out, the Federal Housing Authority liked to help out war vets. They’d only had to spend four pregnant months in Ledford’s beat-up old house next to the scrapyard. In that time, Ledford had fixed things like cracked door thresholds and rotten windowpanes, but in the end he was glad to move into a new place. There were memories left behind in his boyhood home, but he hadn’t yet sold it. He’d kept it as a place to go to on his own once in a while. These visits were less and less, as Ledford was skilled in the art of pushing on from the past.

His mother-in-law had been right about a man with a history degree. He hadn’t done much with it. But, his mother-in-law had also left her family stake in Mann Glass to Rachel, and that meant a good deal. For one, Ledford had gone back to work. Not as a furnace tender, but as hot end manager. Desk job. He didn’t care for the work, of course, but he could close his door even on the likes of Lucius Ball, who was now a broken man with the same pension to look forward to as everybody else. Rachel had sold the factory to a Toledo glass man who’d been a friend of her grandfather’s. She and Ledford had put the Mann money in the bank for something they didn’t yet understand. Rachel spoke to her father some, but only on the phone. He hadn’t yet met his granddaughter, and she was three weeks old.

Mary grunted again. “She’s hungry,” Rachel said. “Hand her over.”

Ledford did so, kissing the little one once more as he passed her to Rachel. Then he walked into the kitchen and opened another beer. Church of the Air was coming through the radio, but Edward R. Murrow would be on at one-forty-five.

Through the Philco, the preacher asked, “How long has it been since you labored in the field of God? How long since you bathed in his majestic waters?”

“Too long,” Ledford answered. He cleared his throat and spat in the kitchen sink.

The preacher’s words stirred in Ledford a memory he’d not had in years.

There was a field, and he’d run through its weeds as a boy. Shoulderhigh, the weeds seemed to know he was coming, bending before him and waking like water behind. There was a barn and an old preacher woman with a clay pipe in her teeth.

There was the lake from his dream, and his daddy, fishing from the rowboat.

Ledford went to the basement and looked at the half-full bookcase he’d built. It wasn’t plumb to the ground. He stared at two books, side by side. The Growth of the American Republic and the Holy Bible. Both had belonged to his father. He picked up the old King James and looked for penciled underlinings. The marks of Bill Ledford’s study. The marks of a man who could never outrun the engine in his head, but who would damn sure try. Ledford located one such passage. He took a belt off his beer and read the words, I neither learned wisdom, nor have the knowledge of the holy. Who hath ascended up into heaven, or descended? Who hath gathered the wind in his fists? Ledford liked that last line. He said it aloud. “Gathered the wind in his fists.”

The phone rang. He slid the Bible back to its designation and picked up the receiver. It was Erm. He had a tip on a horse in the eighth at Pimlico. “This is the overlay of overlays, Leadfoot,” he kept saying. “Don’t back off the gas now.”

He told Erm to put him down for another five hundred and hung up. Stood in the center of the basement and looked around. His shinbone was acting up. Like someone had taken a hot poker to it. But Ledford would not sit down and prop it up. He’d ignore it.

Everything salvageable from his old house had ended up in the basement. There was a full tail fan of turkey feathers, gathered at the base in a knot of quills. It had come from his father’s father. It sat on top of the bookcase, next to handblown blue bottles and three big glass scraps shaped liked diamonds. Against the wall there was an old brown trunk with quilts inside, one of them covered in swastikas. It was made by his great-grandmother, who, according to his father, had been half Indian. You’d always had to hide such a quilt, even before the second war, on account of Hitler. But Ledford’s daddy told him that the quilt’s true meaning was luck. Or love. One or the other, he’d never been sure.

The burn in his shinbone flared. He sat down on top of the trunk and picked at a shoot of splintering wood. Checked his watch again. Murrow would be coming on. He’d not listen today. He didn’t want the news.