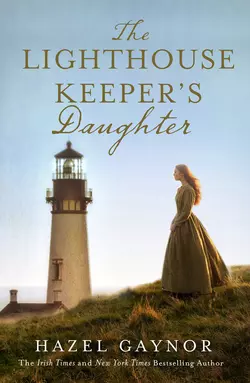

The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter

Hazel Gaynor

From the bestselling author of The Girl Who Came Home and The Girl From The Savoy comes a novel inspired by the extraordinary story of a remarkable young woman.‘This exquisite, thoroughly researched book places (Gaynor) a clear head and shoulders above the rest. Sunday Independent1838: when a terrible storm blows up off the Northumberland coast, Grace Darling, the lighthouse-keeper’s daughter, knows there is little chance of survival for the passengers on the small ship battling the waves. But her actions set in motion an incredible feat of bravery that echoes down the century.1938: when nineteen-year-old Matilda Emmerson sails from across the Atlantic to New England, she faces an uncertain future. Sent away in disgrace, she must stay with her reclusive relative, Harriet Flaherty, a lighthouse keeper on Rhode Island. Once there, Matilda discovers a discarded portrait that opens a window on to a secret that will change her life forever.

Copyright (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Hazel Gaynor 2018

Cover design: Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Jill Battaglia / Trevillion Images

(Lighthouse/background), Lee Avison / Arcangel images (Woman on hill)

Hazel Gaynor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008255213

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008255237

Version: 2018-08-07

Dedication (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

For courageous women everywhere. You know who you are.

Epigraph (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

I am not afraid of storms, for I am learning how to sail my ship.

—Louisa May Alcott

There are two ways of spreading light; to be the candle, or the mirror that reflects it.

—Edith Wharton

Contents

Cover (#u75e4ed0a-6844-597d-bb82-133ee70111c8)

Title Page (#u894bea24-2af2-586e-8141-a360d98a3cbb)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: Matilda

Volume One

Chapter One: Sarah

Chapter Two: Grace

Chapter Three: Sarah

Chapter Four: Grace

Chapter Five: Sarah

Chapter Six: Grace

Chapter Seven: Sarah

Chapter Eight: Grace

Chapter Nine: Sarah

Chapter Ten: Grace

Chapter Eleven: Matilda

Chapter Twelve: Matilda

Chapter Thirteen: Harriet

Chapter Fourteen: Matilda

Chapter Fifteen: Grace

Chapter Sixteen: Grace

Chapter Seventeen: Grace

Volume Two

Chapter Eighteen: Matilda

Chapter Nineteen: Harriet

Chapter Twenty: Matilda

Chapter Twenty-One: Grace

Chapter Twenty-Two: Grace

Chapter Twenty-Three: Grace

Chapter Twenty-Four: Grace

Chapter Twenty-Five: Matilda

Chapter Twenty-Six: Matilda

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Harriet

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Matilda

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Grace

Chapter Thirty: Grace

Chapter Thirty-One: Grace

Chapter Thirty-Two: Grace

Chapter Thirty-Three: Grace

Chapter Thirty-Four: Matilda

Chapter Thirty-Five: Harriet

Chapter Thirty-Six: Matilda

Volume Three

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Grace

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Grace

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Matilda

Chapter Forty: Matilda

Chapter Forty-One: Grace

Chapter Forty-Two: George

Chapter Forty-Three: Grace

Chapter Forty-Four: Grace

Chapter Forty-Five: Matilda

Chapter Forty-Six: Matilda

Chapter Forty-Seven: Grace

Chapter Forty-Eight: Matilda

Chapter Forty-Nine: Harriet

Chapter Fifty: Grace

Chapter Fifty-One: Matilda

Chapter Fifty-Two: Harriet

Chapter Fifty-Three: Matilda

Chapter Fifty-Four: Grace

Chapter Fifty-Five: George

Chapter Fifty-Six: Matilda

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

The Creation of a Heroine

Reading Group Questions

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Also by Hazel Gaynor

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

MATILDA (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

Cobh, Ireland. May 1938

THEY CALL IT Heartbreak Pier, the place from where I will leave Ireland. It is a place that has seen too many goodbyes.

From the upper balcony of the ticket office I watch the third-class passengers below, sobbing as they cling to their loved ones, exchanging tokens of remembrance and promises to write. The outpouring of emotion is a sharp contrast to the silence as I stand between my mother and Mrs. O’Driscoll, my chaperone for the journey. I’ve done all my crying, all my pleading and protesting. All I feel now is a sullen resignation to whatever fate has in store for me on the other side of the Atlantic. I hardly care anymore.

Tired of waiting to board the tenders, I take my ticket from my purse and read the neatly typed details for the umpteenth time. Matilda Sarah Emmerson. Age 19. Cabin Class. Cobh to New York. T.S.S. California. Funny, how it says so much about me, and yet says nothing at all. I fidget with the paper ticket, tug at the buttons on my gloves, check my watch, spin the cameo locket at my neck.

“Do stop fiddling, Matilda,” Mother snips, her pinched lips a pale violet in the cool spring air. “You’re making me anxious.”

I spin the locket again. “And you’re making me go to America.” She glares at me, color rushing to her neck in a deep flush of anger, her jaw clenching and straining as she bites back a withering response. “I can fiddle as much as I like when I get there,” I add, pushing and provoking. “You won’t know what I’m doing. Or who with.”

“Whom with,” she corrects, turning her face away with an exaggerated sniff, swallowing her exasperation and fixing her gaze on the unfortunates below. The cloying scent of violet water seeps from the exposed paper-thin skin at her wrists. It gives me a headache.

My fingers return defiantly to the locket, a family heirloom that once belonged to my great-great-granny Sarah. As a child I’d spent many hours opening and closing the delicate filigree clasp, making up stories about the miniature people captured in the portraits inside: an alluring young woman standing beside a lighthouse, and a handsome young man, believed to be a Victorian artist, George Emmerson, a very distant relative. To a bored little girl left to play alone in the drafty rooms of our grand country home, these tiny people offered a tantalizing glimpse of a time when I imagined everyone had a happy ever after. With the more cynical gaze of adulthood, I now presume the locket people’s lives were as dull and restricted as mine. Or as dull and restricted as mine was until half a bottle of whiskey and a misjudged evening of reckless flirtation with a British soldier from the local garrison changed everything. If I’d intended to get my mother’s attention, I had certainly succeeded.

The doctor tells me I am four months gone. The remaining five, I am to spend with a reclusive relative, Harriet Flaherty, who keeps a lighthouse in Newport, Rhode Island. The perfect hiding place for a girl in my condition; a convenient solution to the problem of the local politician’s daughter who finds herself unmarried and pregnant.

At one o’clock precisely, the stewards direct us to board the tenders that will take us out to the California, moored on the other side of Spike Island to avoid the mud banks in Cork Harbor. As I step forward, Mother grasps my hand dramatically, pressing a lace handkerchief to her paper-dry cheeks.

“Write as soon as you arrive, darling. Promise you’ll write.” It is a carefully stage-managed display of emotion, performed for the benefit of those nearby who must remain convinced of the charade of my American holiday. “And do take care.”

I pull my hand away sharply and say goodbye, never having meant the words more. She has made her feelings perfectly clear. Whatever is waiting for me on the other side of the Atlantic, I will face it alone. I wrap my fingers around the locket and focus on the words engraved on the back: Even the brave were once afraid.

However well I might hide it, the truth is, I am terrified.

VOLUME ONE (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

founder:(verb)

to become submerged; to come to grief

I had little thought of anything but to exert myself to the utmost, my spirit was worked up by the sight of such a dreadful affair that I can imagine I still see the sea flying over the vessel.

—Grace Darling

CHAPTER ONE (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

SARAH (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

S.S. Forfarshire. 6th September, 1838

SARAH DAWSON DRAWS her children close into the folds of her skirt as the paddle steamer passes a distant lighthouse. Her thoughts linger in the dark gaps between flashes. James remarks on how pretty it is. Matilda wants to know how it works.

“I’m not sure, Matilda love,” Sarah offers, studying her daughter’s eager little face and wondering how she ever produced something so perfect. “Lots of candles and oil, I expect.” Sarah has never had to think about the mechanics of lighthouses. John was always the one to answer Matilda’s questions about such things. “And glass, I suppose. To reflect the light.”

Matilda isn’t satisfied with the answer, tugging impatiently at her mother’s skirt. “But how does it keep going around, Mummy? Does the keeper turn a handle? How do they get the oil all the way to the top? What if it goes out in the middle of the night?”

Suppressing a weary sigh, Sarah bobs down so that her face is level with her daughter’s. “How about we ask Uncle George when we get to Scotland. He’s sure to know all about lighthouses. You can ask him about Mr. Stephenson’s Rocket, too.”

Matilda’s face brightens at the prospect of talking about the famous steam locomotive.

“And the paintbrushes,” James adds, his reedy little voice filling Sarah’s heart with so much love she could burst. “You promised I could use Uncle George’s easel and brushes.”

Sarah wipes a fine mist of sea spray from James’s freckled cheeks, letting her hands settle there a moment to warm him. “That’s right, pet. There’ll be plenty of time for painting when we get to Scotland.”

She turns her gaze to the horizon, imagining the many miles and ports still ahead, willing the hours to pass quickly as they continue on their journey from Hull to Dundee. As a merchant seaman’s wife, Sarah has never trusted the sea, wary of its moody unpredictability even when John said it was where he felt most alive. The thought of him stirs a deep longing for the reassuring touch of his hand in hers. She pictures him standing at the back door, shrugging on his coat, ready for another trip. “Courage, Sarah,” he says as he bends to kiss her cheek. “I’ll be back at sunrise.” He never said whichsunrise. She never asked.

As the lighthouse slips from view, a gust of wind snatches Matilda’s rag doll from her hand, sending it skittering across the deck and Sarah dashing after it over the rain-slicked boards. A month in Scotland, away from home, will be unsettling enough for the children. A month in Scotland without a favorite toy will be unbearable. The rag doll safely retrieved and returned to Matilda’s grateful arms, and all interrogations about lighthouses and painting temporarily stalled, Sarah guides the children back inside, heeding her mother’s concerns about the damp sea air getting into their lungs.

Below deck, Sarah sings nursery rhymes until the children nap, lulled by the drone of the engines and the motion of the ship and the exhausting excitement of a month in Bonny Scotland with their favorite uncle. She tries to relax, habitually spinning the cameo locket at her neck as her thoughts tiptoe hesitantly toward the locks of downy baby hair inside—one as pale as summer barley, the other as dark as coal dust. She thinks about the third lock of hair that should keep the others company; feels the nagging absence of the child she should also hold in her arms with James and Matilda. The image of the silent blue infant she’d delivered that summer consumes her so that sometimes she is sure she will drown in her despair.

Matilda stirs briefly. James, too. But sleep takes them quickly away again. Sarah is glad of their innocence, glad they cannot see the fog-like melancholy that has lingered over her since losing the baby and losing her husband only weeks later. The doctor tells her she suffers from a nervous disposition, but she is certain she suffers only from grief. Since potions and pills haven’t helped, a month in Scotland is her brother’s prescription, and something of a last resort.

As the children doze, Sarah takes a letter from her coat pocket, reading over George’s words, smiling as she pictures his chestnut curls, eyes as dark as ripe ale, a smile as broad as the Firth of Forth. Dear George. Even the prospect of seeing him is a tonic.

Dundee. July 1838

Dear Sarah,

A few lines to let you know how eager I am to see you, and dear little James and Matilda—although I expect they are not as little as I remember and will regret promising to carry them piggy back around the pleasure gardens! I know you are anxious about the journey and being away from home, but a Scottish holiday will do you all the world of good. I am sure of it. Try not to worry. Relax and enjoy a taste of life on the ocean waves (if your stomach will allow). I hear the Forfarshire is a fine vessel. I shall be keen to see her for myself when she docks.

No news, other than to tell you that I bumped into Henry Herbert and his sisters recently at Dunstanburgh. They are all well and asked after you and the children. Henry was as tedious as ever, poor fellow. Thankfully, I found diversion in a Miss Darling who was walking with them—the light keeper’s daughter from Longstone Island on the Farnes. As you can see in the margins, I have developed something of a fondness for drawing lighthouses. Anyway, I will tell you more when you arrive. I must rush to catch the post.

Wishing you a smooth sailing and not too much of the heave ho, me hearties!

Your devoted brother,

George

x

p.s. Eliza is looking forward to seeing you. She and her mother will visit while you are here. They are keen to discuss the wedding.

Sarah admires the miniature lighthouses George has drawn in the margins before she folds the letter back into neat quarters and returns it to her pocket. She hopes Eliza Cavendish doesn’t plan to spend the entire month with them. She isn’t fond of their eager little cousin, nor her overbearing mother, but has resigned herself to tolerating them now that the engagement is confirmed. Eliza will make a perfectly reasonable wife for George and yet Sarah cannot help feeling that he deserves so much more than reasonable. If only he would look up from his canvas once in a while, she is sure he would find his gaze settling on someone far more suitable. But George will be George and even with a month at her disposal, Sarah doubts it will be long enough to change his mind. Still, she can try.

Night falls beyond the porthole as the ship presses on toward Dundee. One more night’s sailing, Sarah tells herself, refusing to converse with the concerns swimming about in her mind. One more night, and they’ll be safely back on dry land. She holds the locket against her chest, reminding herself of the words John had engraved on the back. Even the brave were once afraid.

Courage, Sarah, she tells herself. Courage.

CHAPTER TWO (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

GRACE (#uc071b284-494b-51c0-9195-467488f42b74)

Longstone Lighthouse. 6th September, 1838

DAWN BLOOMS OVER the Farne Islands with soft layers of rose-tinted clouds. From my narrow bedroom window I admire the spectacle, while not trusting it entirely. We islanders know, better than most, how quickly the weather can turn, and there is a particular shape to the clouds that I don’t especially care for.

After spending the small hours on watch, I’m glad to stretch my arms above my head, savoring the release of tension in my neck and shoulders before climbing the steps to the lantern room. Another night navigated without incident is always a cause for quiet gratitude and I say my usual prayer of thanks as I extinguish the Argand lamps, their job done until sunset. The routine is so familiar that I almost do it without thought: trim the wicks, polish the lenses of the parabolic reflectors to remove any soot, cover the lenses with linen cloths to protect them from the glare of the sun. Necessary routine tasks which I take pride in doing well, eager to prove myself as capable as my brothers and eager to please my father.

A sea shanty settles on my lips as I work, but despite my efforts to focus on my chores, my thoughts—as they have for the past week—stubbornly return to Mr. George Emmerson. Why I persist in thinking of him, I cannot understand. We’d only spoken briefly—twenty minutes at most—but something about the cadence of his Scots burr, the particular way he rolled his r’s, the way he tilted his head when surveying the landscape, and most especially his interest in Mary Anning’s fossils, has stuck to me like barnacles on a rock. “Tell me, Miss Darling, what do you make of Miss. Anning’s so-called sea drrragons?” My mimicry brings a playful smile to my lips as I cover the last of the reflectors, idle thoughts of handsome Scotsmen temporarily concealed with them.

The lamps tended to, I walk once around the lantern to catch the beauty of the sunrise from all angles. From the first time I’d climbed the spiraling lighthouse steps at the age of seven, it was here, at the very top of the tower, where I loved to be most of all, the clouds almost within touching distance, the strong eighty-foot tower below keeping us safe. The uninterrupted view of the Farne Islands and the Northumbrian coast hangs like a vast painting in a private gallery, displayed just for me, and despite the growl in my stomach I’m in no hurry to head downstairs for breakfast. I lift Father’s telescope from the shelf and follow a flock of sandwich terns passing to the south before lowering the lens to watch the gulls bobbing about on the sea, waiting for the herring fleet to return. The patterns of light on the surface of the water remind me of Mary Herbert’s silk dress shimmering as she danced a reel at last year’s harvest home ball.

Dear Mary. Despite our friendship, she and her sister, Ellen, have always thought me a curious creature, unable to understand how anyone could possibly prefer the wind-lashed isolation of an island lighthouse to the merry hubbub of a dance. “Will we see you at the ball this year, Grace? Henry is anxious to know.” Their dedication to the cause of finding me a suitable husband—preferably their brother—is nothing short of impressive, but the business of marriage doesn’t occupy my thoughts as it does other women of my age, who seem to think about little else. Even my sisters, who now live over on the Main, perpetually tease me about being married to the lighthouse. “You’ll never find a husband if you hide away in your tower, Grace. You can’t very well expect the tide to deliver one to you.” Time and again, I have patiently explained that even if I did marry I would merely be swapping the life of a dutiful daughter for that of a dutiful wife, and from what I’ve observed I’m not at all convinced the institution of marriage is worth the exchange. It is a point well-made, and one they find difficult to argue with.

As I make my way down to the service room which sits just below the lantern room, I pause at the sound of my father’s voice floating up the steps.

“You coming down, Gracie?” Mam has a fresh loaf. She insists it needs eating before the mice get to it.”

His Trinity House cap appears above the top step, followed by thick eyebrows, white as the lime-washed tower walls. I take his arm to help him up the last few steps.

“You’re supposed to be resting,” I scold.

His breathing is labored. His cheeks—already rusted from decades of wind and sun—scarlet with the effort of climbing the ninety-three steps from the ground floor. “I know, pet. But Mam mithers when I rest. Thought I’d be better off resting where she can’t see me.” He winks as he sinks gladly into his favorite chair, taking the telescope from me and lifting it to his eye. “Anything doing?”

“Mercifully quiet,” I remark, adding a few lines to the Keeper’s Log about the weather and the sea conditions before recording the tides. “A few paddle steamers and fishing vessels passed. The seals are back on Harker’s Rock.”

Father scans the horizon, looking for anything unusual among the waves, interpreting the particular shape of the swells, crests, and troughs. It bothers him that his eyesight isn’t what it used to be, glad to have me as a second pair of eyes. We make a good team; him the patient teacher, me the eager pupil.

“Seals on Harker’s Rock, eh. Local fishermen will tell you that’s a sign of a storm coming. Mam’s already fretting about your brother getting back.” He focuses the telescope on the clouds then, looking for any indication of approaching squalls or incoming fogs or anything to suggest an imminent change in the conditions. My father reads the clouds and the behavior of the seabirds as anyone else might read directions on a compass, understanding the information they offer about bad weather approaching, snow on the way, a north wind blowing. Partly by his instruction and partly by an inherent islander’s instinct nurtured over my twenty-two years, I have absorbed some of this knowledge, too. But even the most experienced mariner can occasionally be fooled.

Father rubs his chin as he always does when he’s thinking. “I don’t trust that sky, Gracie. You know what they say about red skies in the morning.”

“Sailors’ warning,” I say. “But the sky is pink, Father, not red. And anyway, it’s far too pretty to be sinister.”

Chuckling at my optimism, he places the telescope in his lap and shuts his eyes, enjoying the warmth of the sunlight against his face.

It troubles me to see how he’s aged in recent months; that he isn’t quite as vigorous as he once was. But despite doctor’s orders that he take it easy, he insists on continuing as Principal Keeper. As stubborn as he is humble, there’s little point in arguing with him. Being the light keeper here isn’t just my father’s job—it is his life, his passion. I might as well tell him to stop breathing as to stop doing the familiar routines he has faithfully carried out here for decades.

“You look tired, Father. Didn’t you sleep well?”

He waves my concern away, amused by the notion of his little girl taking the role of parent as I often do these days. “Mam was at her snoring again. Thought it was the cannons firing from Bamburgh to signal a shipwreck.” He opens one eye. “Don’t tell her I said that.”

I laugh and promise not to.

Taking the telescope from him, I lift the cool rim to my eye, tracking a fisherman’s boat as it follows a course from North Sunderland toward the Outer Farnes. Hopefully it is a postal delivery with word from Trinity House regarding our annual inspection. Waiting for the report always makes Father restless, even though previous reports have consistently noted the exceptional standards maintained at the Longstone light, declaring it to be among the best-kept stations in England. “Pride goes before destruction,” Father says whenever I remind him of this. “And a haughty spirit before stumbling. Proverbs 16:18.” He is not a man to dwell on success, only striving to work harder because of it. Among the many traits that I admire in him, his humility is the one I admire the most.

Hauling himself up from the chair, he joins me at the window. “The hairs are prickling at the back of my neck, Grace. There’s bad weather coming, I can feel it in the air. And then there’s birds flying in through the window downstairs.”

“Not again?”

“Nearly gave your mam a heart attack. You know what she says about birds coming inside and people dropping down dead.”

“I’d rather the birds flew inside than knocked themselves out against the glass.” Too many birds crash against the lantern room windows, dazzled by the reflected sun. I’ve often found a stiffened guillemot or puffin when I step out onto the perimeter to clean the glass.

“Which one of us do you think it is then, Gracie, because I’m not in the mood for perishing today, and I certainly hope it isn’t you? So that only leaves your poor old mam, God rest her.”

“Father! You’re wicked.” I bat his arm affectionately, pleased to see the sparkle return to his eyes, even if it is at Mam’s expense.

My parents’ quarrelling is as familiar to me as the turn of the tides, but despite all the nagging and pointed sighs, I know they care for each other very much. Mam could never manage without my father’s practicality and good sense, and he would be lost without her steadfast resourcefulness. Like salt and the sea they go well together and I admire them for making it work, despite Mam being twelve years my father’s senior, and despite the often testing conditions of island life.

Father flicks through the Log book, adding a few remarks in his careful script. September 6th: Sea conditions: calm. Wind: Light south-westerly. Paddle steamer passing on horizon at two o’clock. Clouds massing in the south. He takes my hand in his then, squeezing it tight, just like he used to when I was a little girl walking beside him on the beaches at Brownsman, our first island home. The rough calluses on his palms rub against my skin, his fingers warm and paper dry as they wrap themselves around mine, like rope coiling neatly back into place.

“Thank you, Grace.”

“For what?”

“For being here with me and Mam. It can’t be easy for you, seeing your sisters and brothers marry and set themselves up on the Main.”

I squeeze his hand in reply. “And why would I want to marry and live on the Main? Where else would I want to be other than here, with you and Mam and the lamps and the seals?” It’s an honest question. Only very rarely do my thoughts stray across the sea toward an imaginary life as a dressmaker or a draper’s wife in Alnwick, but such thoughts never last long. I’ve seen how often women marry and become less of themselves, like scraps of pastry cut away and reused in some other, less important way. Besides, I don’t belong to bustling towns with their crowded streets and noisy industry. I belong here, with the birds and the sea, with the wild winter winds and unpredictable summers. While a harvest home dance might enchant Mary and Ellen Herbert for an evening, dear Longstone will enchant me far longer than that. “The island gives me the greatest freedom, Father. I would feel trapped if I lived anywhere else.”

He nods his understanding. “Still, you know you have my blessing, should you ever find a reason to feel differently.”

I take my hand from his and smooth my skirts. “Of course, and you will be the first to know!”

I leave him then, descending the spiraling staircase, the footsteps of my absent sisters and brothers carried in the echo that follows behind. There’s an emptiness to the lighthouse without the hustle and bustle of my seven siblings to trip over and squabble with, and although I enjoy the extra space afforded by their absence, I occasionally long for their rowdy return.

As always, there is a chill in the drafty stairwell and I pull my plaid shawl around my shoulders, hurrying to my small bedroom beneath the service room, where a cheery puddle of sunlight illuminates the floor and instantly warms me. The room is no more than half a dozen paces from one side to the other. I often think it is as well none of us Darling children grew to be very tall or large in frame or we should have had a very sorry time always bending and stooping. Against one wall is my wooden bedchamber, once shared with my sister, Betsy. A writing desk stands in the center of the room, an ewer, basin and candlestick placed upon it.

Crouching down beside a small tea chest beneath the window, I push up the lid and rummage inside, my fingers searching for my old work box, now a little cabinet of curiosities: fragile birds’ eggs protected by soft goose down; all shape and size of seashells; smooth pebbles of green and blue sea glass. I hope the collection might, one day, be impressive enough to show to Father’s friends at the Natural History Society, but for now I’m content to collect and admire my treasures from the sea, just as a lady might admire the precious gems in her jewelry box. Much as I don’t want for a husband or a position as a dressmaker, nor do I want for fancy jewels.

Taking a piece of emerald sea glass from my pocket, I add it to the box, my thoughts straying to the piece of indigo sea glass I’d given to Mr. Emmerson, and the generous smile he’d given me in return. “There is an individuality in everything, Mr. Emmerson. If you look closely at the patterns on seashells, you’ll see that they’re not the same after all, but that each is, in fact, unique.” He wasn’t like Henry Herbert or other men in my acquaintance, eager to brag about their own interests and quick to dismiss a woman’s point of view, should she dare to possess one. Mr. Emmerson was interested in my knowledge of the seabirds and the native wild flowers that grow along Dunstanburgh’s shoreline. When we parted, he said he’d found our conversation absorbing, a far greater compliment than to be considered pretty, or witty.

“Grace Horsley Darling. What nonsense.”

I scold myself for my silliness. I am no better than a giggling debutante with an empty dance card to dwell on a conversation of so little significance. I close the lid of the work box with a snap before returning it to the tea chest.

Continuing down the steps, I pass the second-floor room where my sisters Mary-Ann and Thomasin had once slept in their bunk beds, whispering and giggling late into the night, sharing that particular intimacy only twins can know, and on, past my brother Brooks’ bedroom on the first floor, his boots left where he kicked them off beneath his writing table, his nightshirt hanging over the back of a chair, waiting expectantly for his return.

At the bottom of the stairwell, I step into our large circular living quarters where Mam is busy kneading a bad mood into great mounds of bread dough at the table in front of the wood-burning stove, muttering about people sitting around the place like a great sack of coal and, Lor!, how her blessed old bones ache.

“At last! I thought you were never coming down,” she puffs, wiping the back of her hand against her forehead, her face scarlet from her efforts. “I’m done in. There’ll be enough stotties to build another lighthouse when I’m finished with all this dough. I canna leave it now though or it’ll be as flat as a plaice. Have you seen Father?”

“He’s in the service room. I said I would take him up a hot drink.”

“Check on the hens first, would you? I’m all dough.”

Taking my cloak and bonnet from the hook beside the door, I step outside and make my way to the henhouse where I collect four brown eggs and one white before taking a quick stroll along the exposed rocks, determined to catch some air before the weather turns and the tide comes in. I peer into the miniature aquariums in the rock pools, temporary homes for anemone, seaweed, pea crabs, mussels, and limpets. As the wind picks up and the first spots of rain speckle my skirt, I tighten the ribbons on my bonnet, pull my cloak about my shoulders, and hurry back to the lighthouse where Mam is standing at the door, frowning up at the darkening skies.

“Get inside, Grace. You’ll catch your death in that wind.”

“Don’t fuss, Mam. I was only out five minutes.”

Ignoring me, she wraps a second plaid around my shoulders as I remove my cloak. “Best to be safe than sorry. I hope your brother doesn’t try to make it back,” she sighs. “There’s trouble coming on that wind, but you know how stubborn he is when he sets his mind to something. Just like his father.”

And not unlike his mam, I think. I urge her not to worry. “Brooks will be in the Olde Ship, telling tall tales with the rest of them. He won’t set out if it isn’t safe to do so. He’s stubborn, but he isn’t foolish.” I hope he is, indeed, back with the herring fleet at North Sunderland. It will be a restless night without him safe in his bed.

“Well, let’s hope you’re right, Grace, because there was that bird making a nuisance of itself inside earlier. It sets a mind to thinking the worst.”

“Only if you let it,” I say, my stomach growling to remind me that I haven’t yet eaten.

Leaving Mam to beat the hearth rug, and her worries, against the thick tower walls with heavy slaps, I place the basket of eggs on the table, spread butter on a slice of still-warm bread, and sit beside the fire to eat, ignoring the wind that rattles the windows like an impatient child. The lighthouse, bracing itself for bad weather, wraps its arms around us. Within its proud walls, I feel as safe as the fragile birds’ eggs nestling in their feather beds in my work box, but my thoughts linger on those at sea, and who may yet be in danger if the storm worsens.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_6de24a8b-673e-50f8-a28a-141d3dad66e6)

SARAH (#ulink_6de24a8b-673e-50f8-a28a-141d3dad66e6)

S.S. Forfarshire. 6th September, 1838

SARAH DAWSON AND her children sleep in each other’s arms, unaware of the storm gathering strength beyond the porthole windows, or the drama unfolding below deck as Captain John Humble orders his chief engineer to start pumping the leaking starboard boiler. Discussions and heated arguments take place among the crew, but as they pass the port of Tynemouth, Humble decides not to turn in for repairs but to press on, tracking the Northumberland coast, his mind set on arriving into Dundee on schedule, just after sunrise the following morning.

Steadying himself against the wheelhouse door as the ship pitches and rolls in the growing swell, Humble sips a hot whiskey toddy and studies his nautical charts, focusing on the course he must follow to avoid the dangerous rocks around the Inner and Outer Farne Islands, and the distinctive characteristics of the lighthouses that will guide him safely through. He has sailed this route a dozen times or more, and despite the failing boiler, he reassures his chief engineer that there is no need for alarm. The S.S. Forfarshire limps on as the storm closes in.

Dundee, Scotland.

At a narrow table beside the fire of his lodgings in Balfour Street, George Emmerson sips a glass of porter, glances at his pocket watch, and picks up a small pebble-sized piece of indigo sea glass from the table. He thinks, too often, about the young woman who’d given it to him as a memento of his trip to Northumberland. Treasure from the sea, she’d called it, remarking on how fascinating she found it that something as ordinary as a discarded medicine bottle could become something so beautiful over time.

He leans back in his chair, holding the page of charcoal sketches in front of him. He is dissatisfied with his work, frustrated by his inability to capture the image he sees so clearly in his mind: her slender face, the slight compression of her lip, the coil of sunlit coffee-colored curls on her head, the puzzled frown across her brow as if she couldn’t quite grasp the measure of him and needed to concentrate harder to do so.

Grace Darling.

Her name brings a smile to his lips.

He imagines Eliza at his shoulder, feigning interest in his “pictures” while urging him to concentrate and tell her which fabric he prefers for the new curtains. The thought of his intended trips him up, sending a rosy stain of guilt rushing to his cheeks. He scrunches the sketches into a ball, tossing them into the fire before checking his pocket watch again. Sarah will be well on her way. Her visit is timely. Perhaps now, more than ever, he needs the wise counsel and pragmatic opinions of his sister. Where his thoughts often stray to those of romantic ideals, Sarah has no time for such notions and will put him firmly back on track. Still, she isn’t here yet.

For now, he chooses to ignore the rather problematic matter of the ember that glows within him for a certain Miss Darling. As the strengthening wind rattles the leaded windows and sets the candle flame dancing, George runs his hands through his hair, loosens the pin at his collar, and pulls a clean sheet of paper toward him. He picks up the piece of indigo sea glass and curls his fingers around it. With the other hand, he takes up his charcoal and starts again, determined to have it right before the flame dies.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_568999c8-832d-59cd-b03d-fdefc3a56515)

GRACE (#ulink_568999c8-832d-59cd-b03d-fdefc3a56515)

Longstone Lighthouse. 6th September, 1838

LATE AFTERNOON AND the sky turns granite. Secure inside the soot-blackened walls of the lighthouse, we each find a way to distract ourselves from the strengthening storm. Mam sits at her spinning wheel, muttering about birds flying indoors. Father leans over the table, tinkering with a damaged fishing net. I brush my unease away with the dust I sweep outside.

The living quarters is where we spend our time when we aren’t tending to the lamps, or on watch, or occupied at the boathouse. Our lives cover every surface of the room in a way that might appear haphazard to visitors, but is perfectly organized to us. While we might not appear to have much in the way of possessions, we want for nothing.

Bonnets and cloaks roost on hooks by the door, ready to be thrown on at short notice. Pots and pans dangle from the wall above the fire like highwaymen on the gallows. The old black kettle, permanently suspended from the crane over the fire, is always ready to offer a warm drink to cold hands. Damp stockings, petticoats, and aprons dry on a line suspended above our heads. All shape and size of seashells nestle on the windowsills and in the gaps between the flagstones. Stuffed guillemots and black-headed gulls—gifted to Father from the taxidermist in Craster—keep a close watch over us with beady glass eyes. Even the sharp tang of brine has its particular space in the room, as does the wind, sighing at the windows, eager to come inside.

As the evening skies darken, I climb the steps to the lantern room where I carefully fill the reservoir with oil before lighting the trimmed wicks with my hand lamp. I wait thirty minutes until the flames reach their full height before unlocking the weights that drive the gears of the clock mechanism, cranking them for the first time that evening. Slowly, the lamps begin to rotate, and the lighthouse comes alive. Every thirty seconds, passing ships will see the flash of the refracted beam. When I am satisfied that everything is in order, I add a comment to the Keeper’s Log: S.S. Jupiter passed this station at 5pm. Strong to gale force north to northeast. Hard rain.

As Father is on first watch, I leave the comforting light of the lamps, and enter the dark interior of the staircase. My sister Thomasin used to say she imagined the stairwell was a long vein running from the heart of the lighthouse. In one way or another, we have all attached human qualities to these old stone walls so that it has almost become another member of the family, not just a building to house us. I feel Thomasin’s absence especially keenly as I pass her bedroom. A storm always stirs a desire for everyone to be safe inside the lighthouse walls, but my sisters and brothers are dispersed along the coast now, like flotsam caught on the tide and carried to some other place.

The hours pass slowly as the storm builds, the clock above the fireplace ticking away laborious minutes as Mam works at her wheel. I read a favorite volume, Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Addressed to a Lady, but even that cannot hold my attention. I pick up a slim book of Robert Burns’ poetry, but it doesn’t captivate me as it usually would, his words only amplifying the weather outside: At the starless, midnight hour / When Winter rules with boundless power, / As the storms the forests tear, / And thunders rend the howling air, / Listening to the doubling roar, / Surging on the rocky shore. I put it down, sigh and fidget, fussing at the seam of my skirt and picking at a break in my fingernail until Mam tells me to stop huffing and puffing and settle at something.

“You’re like a cat with new kittens, Grace. I don’t know what’s got into you tonight.”

The storm has got into me. The wild wind sends prickles running along my skin. And something else nags at me because even the storm cannot chase thoughts of Mr. Emmerson from my mind.

If I were more like Ellen and Mary Herbert I would seek distraction in the pages of the romance novels they talk about so enthusiastically, but Father scoffs at the notion of people reading novels, or playing cards after their day’s work is done, considering it to be a throwing away of time (he doesn’t know how much time my sister, Mary-Ann, throws away on such things), so there are no such books on our shelves. I am mostly glad of his censorship, grateful for the education he’d provided in the service room turned to schoolroom. I certainly can’t complain about a lack of reading material, and yet my mind takes an interest in nothing tonight.

At my third yawn, Mam tells me to go to bed. “Get some rest before your turn on watch, Grace. You look as weary as I feel.”

As she speaks the wind sucks in a deep breath before releasing another furious howl. Raindrops skitter like stones thrown against the windows. I pull my plaid shawl about my shoulders and take my hand lamp from the table.

“It’s getting worse, isn’t it?” The inflection in my voice carries that of a child seeking reassurance.

Mam works the pedal of her spinning wheel in harmony with the brisk movement of her hands, the steady clack clack clack so familiar to me. She doesn’t look up from her task. Inclement weather is part of the fabric of life at Longstone. Mam believes storms should be respected, never feared. “If you show it you’re afraid, you’re already halfway to dead.” She may not be the most eloquent woman, but she is often right. “Sleep well, Grace.”

I bid her goodnight, place a hurricane glass over my candle, and begin the familiar ascent inside the tower walls. Sixty steps to my bedroom. Sixty times to remember eyes, the color of porter. Sixty times to see a slim mustache stretch into a smile as broad as the Tyne, a smile that had stained my cheeks pink and sent Ellen and Mary Herbert giggling into their gloves. Sixty times to scold myself for thinking so fondly of someone I’d spent only a few minutes with, and yet it is to those few minutes my mind stubbornly returns.

Reaching the service room I stand in silence for a moment, reluctant to break Father’s concentration. He sits beside the window, his telescope poised like a cat about to pounce, his senses on high alert.

“You will wake me, Father,” I whisper. “Won’t you?” I’ve asked the same thing every night for as long as I can remember: will he wake me if he needs assistance with the light, or with any rescue he might have to undertake.

Candlelight flickers in the circular spectacles perched on the end of his nose as he turns and acknowledges me with a firm nod. “Of course, pet. Get some sleep. She’ll blow herself out by morning.”

On the few occasions he has required me to tend the light in his absence, I have proven myself very capable. I have my father’s patience and a keen eye, essential for keeping watch over the sea. Sometimes I wonder if it saddens him, just a little, that the future of the lighthouse will lie with my brother, and not me. Brooks will succeed him as Principal Keeper because for all that I am eager and capable, I am—first and foremost—a woman.

A smile spreads across Father’s face as I turn at the top of the steps. “Look at you, Grace. Twenty-two years of unfathomable growth and blossoming beauty and a temperament worthy of your name. Such a contrast to the rumpus outside.”

I shoo his compliment away. “Have you been at the porter again?” I tease, my smile betraying my delight.

Taking up my lamp, I retire to my room, a shrill shriek of wind setting the flame dancing in a draft as a deafening boom reverberates around the lighthouse walls. I peer through the window, mesmerized by the angry waves that plunge against the rocks below and send salt-spray soaring up into the sky like shooting stars.

Picking up my Bible, I kneel beside my bed and pray for the safety of my brother before I blow out my candle and slip beneath the eiderdown. My feet flinch against the cold sheets, my toes searching for the hot stone I’d placed beneath the covers earlier. I lie perfectly still in the dark, picturing the lamps turning above me with the regularity of a steady pulse, their light stretching out through the darkness to warn those at sea and let them know they are not alone in the dark. On quieter nights, I can hear the click click of the clock mechanism turning above. Tonight, I hear only the storm, and the heightened beating of my heart.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_3ace2098-602d-5baf-b91e-5d0d108bf2d3)

SARAH (#ulink_3ace2098-602d-5baf-b91e-5d0d108bf2d3)

S.S. Forfarshire. 7th September, 1838

SARAH SLEEPS LIGHTLY in unfamiliar places and is easily awoken by a violent shudder. Her senses feel their way around in the dark, searching for an explanation as to why the engines are silent. Without their reassuring drone, Sarah hears the howling wind more clearly, feels the pitch and roll of the ocean more acutely. Her fingers reach for the locket at her neck, remembering how surprised she’d been when John had given it to her, wrapped in a small square of purple silk fabric, tied with a matching ribbon. It was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen, made even more beautiful by the locks of their children’s hair he had placed inside.

James and Matilda stir on her lap, rubbing sleepy eyes and asking why the ship has stopped and if they are in Scotland yet and when will it be morning. Sarah smooths their hair, whispering that it won’t be long until they see their uncle George and that they should go back to sleep. “I’ll wake you at first light. We’ll join the herring fleet as we sail into the harbor. The fisherwomen will be out with their pickling barrels. The fish scales will shine like diamonds on the cobbles …”

A chilling roar shatters the silence, followed by a terrifying cracking of timbers and the shriek of buckling metal. Sarah sits bolt upright, her heart racing as she wraps her arms tight around her children.

“What’s happening, Mummy?” Matilda screams. “What’s happening?”

James starts to cry. Matilda buries her face in her mother’s shoulder as the ship lists heavily to starboard. Dark, frigid water gushes inside at such shocking speed that Sarah doesn’t have time to react before she is waist deep in it. Lifting her children, one onto each hip, she starts to move forward. Terror and panic rise in her chest, snatching away short breaths that are already strangled by the effort of carrying her terrified children. She shushes and soothes them, telling them it will be all right, that they’re not to be afraid, that she will keep them safe. And somehow she is outside, the wind tearing at her coat, hard rain lashing at her cheeks as Matilda and James cling desperately to her. For a brief moment she feels a rush of relief. They are not trapped below decks. They are safe. But the water surges suddenly forward, covering her up to her chest and the deck is all but submerged. As she turns to look for assistance, a lifeboat, something—anything—an enormous wave knocks her off her feet and she is plunged underwater and all is darkness.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_de7b3113-757f-5b96-a5d8-4a2078eb7a08)

GRACE (#ulink_de7b3113-757f-5b96-a5d8-4a2078eb7a08)

Longstone Lighthouse. 7th September, 1838

I SLEEP IN UNSATISFYING fragments, the storm so furious I am uneasy, even within the lighthouse’s reliable embrace. As I lie awake, I remember when the lighthouse was built, how I was mesmerized by the tall tapering tower that was to become my home, three miles offshore from the coastal towns of Bamburgh and North Sunderland. “Five feet thick. Strong enough to withstand anything nature might throw at it.” My father was proud to know his new light station was constructed to a design similar to Robert Stevenson’s Bell Rock light. It has been my fortress for fifteen happy years.

Father wakes me at midnight with a gentle shake of the shoulder.

Dressing quickly, I take up my lamp and together we make our way downstairs where we pull on our cloaks and step out into the maelstrom to secure the coble at the boathouse, aware that the dangerous high tide is due at 4:13 A.M. The sea heaves and boils. I can’t remember when I have ever seen it so wild. Returning to the lighthouse, Father retires to bed, leaving me to take my turn on watch.

I take up my usual position at the narrow bedroom window, telescope in hand. The sky is a furious commotion of angry black clouds that send torrents of rain lashing against the glass. The wind tugs at the frame until I am sure it will be pulled right out. My senses are on full alert. Neither tired nor afraid, I focus only on the sea, watching for any sign of a ship in distress.

The night passes slowly, the pendulum clock on the wall ticking away the hours as the light turns steadily above.

Around 4:45 A.M., as the first hint of dawn lends a meager light to the sky, my eye is drawn to an unusual shape at the base of Harker’s Rock, home to the puffin and gannet colonies I love to observe on calm summer days. Visibility is terrible behind the thick veil of rain and sea spray, but I hold the telescope steady until I can just make out dark shapes dotted around the base of the rock. Seals, no doubt, sheltering their pups from the pounding waves. And yet an uncomfortable feeling stirs in the pit of my stomach.

By seven o’clock, the light has improved a little and the receding tide reveals more of Harker’s Rock. Taking up the telescope again, my heart leaps as I see a ship’s foremast jutting upward, clearly visible against the horizon. My instincts were right. They are not seals I’d seen at the base of the rock, but people. Survivors of a shipwreck.

Snatching up my hand lamp, I rush downstairs, the wind shrieking at the windows, urging me to hurry.

I rouse my father with a brusque shake of the shoulders. “A ship has foundered, Father! We must hurry.”

Tired, confused eyes meet mine. “What time is it, Grace? Whatever is the matter?”

“Survivors, Father. A wreck. There are people on Harker’s Rock. We must hurry.” I can hear the tremor in my voice, feel the tremble in my hands as my lamp shakes.

Mam stirs, asking if Brooks is back and what on earth all the commotion is about.

Father reaches for his spectacles, sleepy fingers fumbling like those of a blind man as he sits up. “What of the storm, Grace? The tide?”

“The tide is going out. The storm still rages.” I linger by the window, as if by standing there I might let those poor souls know that help is coming.

Father sighs, his hands dropping back onto the eiderdown. “Then it’s of no use, Grace. I will be shipwrecked myself if I attempt to set out in those seas. Even if I could get to Harker’s Rock I would never be able to row back against the turn of the tide. I wouldn’t make it across Craford’s Gut with the wind against me.”

Of course he is right. Even as I’d rushed to him, I’d heard him speak those very words.

I grasp his hands in mine and sink to my knees at the side of his bed. “But if we both rowed, Father? If I came with you, we could manage it, couldn’t we? We can take the longer route to avail of the shelter from the islands. Those we rescue can assist in rowing back, if they’re able.” I press all my determination into my voice, into my eyes, into his hands. “Come to the window to assure me I’m not imagining things.” I pull on his hands to help him up, passing him the telescope as another strong gust rattles the shutters, sending the rafters creaking above our heads.

My assumptions are quickly confirmed. A small group of human forms can now clearly be seen at the base of the rock, the battered remains of their vessel balanced precariously between them and the violent sea. “Do you see?” I ask.

“Yes, Grace. I see.”

I place my hand on Father’s arm as he folds the telescope and rests his palms against the windowsill. “The North Sunderland lifeboat won’t be able to put out in those seas,” I say, reading his thoughts. “We are their last hope of being rescued. And the Lord will protect us,” I add, as much to reassure myself as my father.

He understands that I am responding to the instinct to help, an instinct that has been instilled in me since I was a child on his knee, listening to accounts of lost fishing vessels and the brave men who rescued the survivors. I feel the drop of his shoulders and know my exertions have prevailed.

“Very well,” he says. “We will make an attempt. Just one, mind. If we can’t reach them …”

“I understand. But we must hurry.”

The decision made, all is action and purpose. We dress quickly and rush to the boathouse. The wind snatches my breath away, almost blowing me sideways as I step outside, my hair whipping wildly about my face. I falter for a moment, wishing my brother were here to help, but he isn’t. We must do this alone, Father and I, or not at all.

Mam helps to launch the boat, each of us taking our role in the procedure as we have done many times before. Words are useless, tossed aside by the wind, so that nobody quite knows what question was asked, or what reply given. I struggle to stand upright against the incessant gusts.

Finally, the boat is in the water. Stepping in, I pick up an oar and sit down.

“Grace! What are you doing?” Mam turns to my father. “William! She can’t go. This is madness.”

“He can’t go alone, Mam,” I shout. “I’m going with him.”

Father steps into the boat beside me. “She is like this storm, Thomasin. She won’t be silenced ’til she’s said her piece. I’ll take care of her.”

I urge Mam not to worry. “Prepare dry clothes and blankets. And have hot drinks ready.”

She nods her understanding and begins to untie the ropes that secure us to the landing wall, her fingers fumbling in the wet and the cold. She says something as we push away, but I can’t hear her above the wind. The storm and the sea are the only ones left to converse with now.

Once beyond the immediate shelter afforded by the base of Longstone Island, it becomes immediately apparent that the sea conditions are far worse than we’d imagined. The swell carries us high one moment before plunging us down into a deep trough the next, a wall of water surrounding us on either side. We are entirely at the mercy of the elements.

Father calls out to me, shouting above the wind, to explain that we will take a route through Craford’s Gut, the channel which separates Longstone Island from Blue Caps. I nod my understanding, locking eyes with him as we both pull hard against the oars. I draw courage from the light cast upon the water by Longstone’s lamps as Father instructs me to pull to the left or the right, keeping us on course around the lee side of the little knot of islands that offer a brief respite from the worst of the wind. As we round the spur of the last island and head out again into the open seas, Father looks at me with real fear in his eyes. Our little coble, just twenty-one foot by six inches, is all we have to protect us. In such wild seas, we know it isn’t nearly protection enough.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_f39bc6ff-8ce0-512d-8039-9177ffcb5326)

SARAH (#ulink_f39bc6ff-8ce0-512d-8039-9177ffcb5326)

Harker’s Rock, Outer Farnes. 7th September, 1838

LIGHT. DARK. LIGHT. Dark.

In the thick black that surrounds her, the beam of light in the distance is especially bright to Sarah Dawson. Every thirty seconds it turns its pale eye on the figures huddled on the rock. Sarah fixes her gaze on its source: a lighthouse. A warning light to stay away. Her only hope of rescue.

Her body convulses violently, as if she is no longer part of it. Only her arms, which grasp James and Matilda tight against her chest, seem to belong to her. She doesn’t know how long it is since the ship went down—moments? hours?—too exhausted and numb to notice anything apart from the shape of her children’s stiff little bodies against hers and the relentless screech of the wind. Behind her, the wrecked bow of the Forfarshire cracks and groans as it smashes against the rocks, breaking up like tinder beneath the force of the waves, the masthead looming from the swell like a sea monster from an old mariner’s tale. The other half of the steamer is gone, taking everyone and everything down with it. She thinks of George waiting for her in Dundee. She thinks of his letter in her pocket, his sketches of lighthouses. She stares at the flashing light in the distance. Why does nobody come?

A man beside Sarah moans. It is a sound like nothing she has ever heard. His leg is badly injured and she knows she should help him, but she can’t leave her children. The desperate groans of other survivors clinging to the slippery rock beside her mingle with the rip and roar of the wind and waves. She wishes they would all be quiet. If only they would be quiet.

The storm rages on.

The rain beats relentlessly against Sarah’s head, like small painful stones. Rocking James and Matilda in her arms, she shelters them from the worst of it, singing to them of lavenders blue and lavenders green. “They’ll be here soon, my loves. Look, the sky is brightening and the herring fleet will be coming in. You remember how the scales look like diamonds among the cobbles. We’ll look for jewels together, when the sun is up.”

Their silence is unbearable.

Unable to suppress her anguish any longer, Sarah tips her head back and screams for help, but all that emerges is a pathetic rasping whisper that melts away into gut-wrenching sobs as another angry wave slams hard against the rock, sweeping the injured man away with it.

Sarah turns her head and wraps her arms tighter around her children, gripping them with a strength she didn’t know she possessed, determined that the sea will not take them from her.

Light. Dark. Light. Dark.

Why does nobody come?

MINUTES COME AND go until time and the sea become inseparable. The light turns tauntingly in the distance. Still nobody comes.

James’s little hand is too stiff and cold in Sarah’s. Matilda’s sweet little face is too still and pale, her hands empty, her beloved rag doll snatched away by the water. Sarah strokes Matilda’s cheek and tells her how sorry she is that she couldn’t tell her how the lighthouse worked. She smooths James’s hair and tells him how desperately sorry she is that she couldn’t keep them safe.

As a hesitant dawn illuminates the true horror of what has unfolded, Sarah slips in and out of consciousness. Perhaps she sees a small boat making its way toward them, tossed around in the foaming sea like a child’s toy, but it doesn’t get any closer. Perhaps she is dreaming, or seeing the fata morgana John used to tell her of: a mirage of lost cities and ships suspended above the horizon. As the black waves wash relentlessly over the desperate huddle of survivors on the rock, Sarah closes her eyes, folding in on herself to shelter her sleeping children, the three of them nothing but a pile of sodden washday rags, waiting for collection.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_cebd4910-132d-5763-a19b-617bca053629)

GRACE (#ulink_cebd4910-132d-5763-a19b-617bca053629)

Longstone Lighthouse. 7th September, 1838

OUR PROGRESS IS frustratingly slow, the distance of three quarters of a mile stretched much farther by the wind and the dangerous rocks that will see us stranded or capsized if we don’t steer around them. We must hurry, and yet we must take care; plot our course.

After what feels like hours straining on the oars, we finally reach the base of Harker’s Rock where the sea thrashes wildly, threatening to capsize the coble with every wave. The danger is far from over.

Lifting his oars into the boat, Father turns to me. “You’ll have to keep her steady, Grace.”

I give a firm nod in reply, refusing to dwell on the look of fear in his eyes, or on the way he hesitates as he jumps onto the jagged rocks, reluctant to leave me.

“Go,” I call. “And hurry.”

Alone in the coble, I begin my battle with the sea, pulling first on the left oar and then on the right, sculling forward and then backward in a desperate effort to stop the boat being smashed against the rocks while Father assesses the situation with the survivors. The minutes expand like hours, every moment bringing a bigger wave to dowse me with frigid water and render me almost blind with the sting of salt in my eyes. Mam’s words tumble through my mind. A storm should be respected, but never feared. Show it you’re afraid, and you’re already halfway to dead. I rage back at the wind, telling it I am not afraid, ignoring the deep burn of the muscles in my forearms. I have never felt more alone or afraid but I am determined to persevere.

Eventually, three hunched figures emerge from the gloom. Men. Bloodied and bruised. Their clothes torn. Shoeless. Bedraggled. They barely resemble human beings. So shocked by their appearance, I take a moment to react, but gather my wits sufficiently to maneuver the coble alongside the rocks.

“Quickly. Climb in,” I shout, pulling all the time on the oars to hold the boat as steady as I can.

The men clamber and fall into the boat, one quietly, two wincing with the pain of each step, the flux in weight and balance tipping the boat wildly as they stumble forward. The two injured men are too stupefied to speak. The other thanks me through chattering teeth as he takes an oar from my frozen hands.

“I’ll help keep her steady, miss.”

Reluctantly, I let go. Only then do I notice the ache in my arms and wrists and realize how hard I’ve been gripping the oars.

“How many more?” I ask, wiping salt water from my eyes.

“Six alive,” he replies.

“And the rest?”

He shakes his head. “Some escaped on the quarter boat. The rest … lost.” Water streams from his shirtsleeves in heavy ribbons, puddling in the bottom of the boat where several inches of seawater have already settled.

My arms and legs tremble from my exertions as I clamber aft to tend to one of the injured men. He stares at me numbly, muttering in his delirium that I must be an angel from Heaven.

“I am no angel, sir. I’m from the Longstone light. You’re safe now. Don’t try to talk.”

The boat pitches and rolls violently as I tend to him, my thoughts straying back to the rock, wondering what is keeping my father.

To my great relief, he appears through the rain a moment later, staggering toward the boat with a woman in his arms, barely alive by the look of her. As he lifts her into the boat, she kicks and struggles to free herself from his grasp, falling onto the rocks. She crawls away from him on her hands and knees, screaming like an animal caught in a trap. Father scoops her up again, calling to me as he lifts her into the boat. “Take her, Grace,” but she slips from my arms and slumps against the boards like a just-landed fish before clambering to her feet and trying to climb out again.

The uninjured man helps me to hold her back. “You must stay in the boat, Mrs. Dawson,” he urges. “You must.”

“You’re safe now,” I assure her as she grabs at my skirts and my shawl. “We’re taking you back to the lighthouse.”

Whatever she says in response, I can’t fully make out. Only the words, “my children” swirl around me before she lets out the most mournful sound and I am glad of a great gust of wind that drowns it out with its greater volume.

Back in the boat, Father takes up his oars, pushing us away from the rocks.

“What of the others?” I call, horrified that we are leaving some of the survivors behind.

“Can’t risk taking any more in these seas,” he shouts. “I’ll have to come back for them.”

“But the woman’s children! We can’t leave them!”

A shake of his head is all the explanation I need and in a terrible instant I understand that it is too late for them. We are too late for them.

As we set out again into the writhing sea, the three remaining survivors huddle together on the rock, waiting for Father to return. But it is not to them my gaze is drawn. My eyes settle on two much smaller forms lying to the left of the others, still and lifeless, hungry waves lapping at little boots. I am reminded of my brother Job, laid out after being taken from us by a sudden fever. I remember how I fixed my gaze on his boots, still covered with sawdust from his apprenticeship as a joiner, unable to bring myself to look at the pale lifeless face that had once been so full of smiles. I turn my face away from the rock and pray for the sea to spare the children’s bodies as I turn my attention to Mrs. Dawson who has slipped into a faint. I am glad; relieved that she is spared the agony of watching the rock fade into the distance as we row away from her children.

After an almighty struggle, the coble finally moves out of the heaviest seas and around to the lee side of the islands, which offers us some shelter. The relentless wind and lashing rain diminish a little and a curious calm descends over the disheveled party in the boat, each of us searching for answers among the menacing clouds above, while Father and his fellow oarsman focus on navigating us safely back to Longstone. I glance around the coble, distressed by the scene of torn clothes, ripped skin, shattered bones and broken hearts. I pray that I will never see anything like it again.

I tend to the two injured men first, fashioning a makeshift tourniquet from my shawl before giving them each a nip of brandy and a blanket and assuring them we don’t have far to go. I return to Mrs. Dawson then, still slumped in the bottom of the boat, her head lolling against the side. I hold her upright and place a blanket over her. She wakes suddenly, her eyes wild as she wails for her children, her hands gripping mine so hard I want to cry out with the pain but absorb it quietly, knowing it is nothing compared to hers. “My babies,” she cries, over and over. “My beautiful babies.”

As she slips into another faint and the boat tosses our stricken party around like rag dolls, I hold her against my chest, my heart full of anguish because I can do nothing but wrap my arms around her shaking shoulders and try to soothe her, knowing it will never be enough. I wonder, just briefly, if it might have been kinder for her to have perished with her children, rather than live without them. Closing my eyes, I pray that she might somehow find the courage to endure this dreadful calamity.

That we all might.

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_39377ab3-b16a-5428-8921-d0fcf432d6d8)

SARAH (#ulink_39377ab3-b16a-5428-8921-d0fcf432d6d8)

Longstone Lighthouse. 7th September, 1838

WHEN SARAH DAWSON opens her eyes, the sky is chalky gray above her. She looks at the young woman called Grace whose eyes are as gentle as a summer breeze and whose hands grip her shoulders. She watches numbly as the boat sets out again, back toward the wreck.

Her arms are empty. Where are her children? In a panic she struggles and falls to her knees. “They are afraid of the dark, Miss,” she sobs, clinging to the young woman’s sodden skirts, tearing at the fabric with her fingernails as if she might somehow crawl her way out of this hell she finds herself in. “And they will be ever so cold. I have to go back. I have to.”

The young woman tells her she is safe now. “My father will being your children back, Mrs. Dawson. We have to get you warm and dry now.”

The words torment her. Why had she been spared when her children had not? How can she bear it to know they are out there in the storm, all alone?

Her body goes limp again as the noise and panic of the sinking ship races through her mind. She can still feel the ache in her arms from carrying her terrified children, one on each hip, as she’d stumbled up the stairs that led to the upper deck, pushing past passengers she’d chatted with earlier that evening, and whose lives she had no care for in her desperate bid to escape the shattering vessel. Her mind wanders back to the warm summer day when the midwife told her the baby was gone. She sees the tiny bundle at the foot of the bed, blue and still. Now James and Matilda, too. All her children, gone. She tries to speak, but all that emerges is a low, guttural moan.

Giving up her struggle, she allows the young woman and her mother to half carry, half drag her along. With every step closer to the lighthouse she wants to scream at them: Why didn’t you come sooner? But her words won’t come and her body can’t find the strength to stand upright. She crawls the final yards to the lighthouse door where she raises her eyes to pray and sees the light turning above.

Light. Dark. Light. Dark.

Matilda wants to know how it works.

James wants to paint it.

Too exhausted and distressed to fight it anymore, she closes her eyes and lets the darkness take her to some brighter place where she sings to her children of lavenders blue and lavenders green, and where her heart isn’t shattered into a thousand pieces, so impossibly broken it can surely never be put back together.

Dundee, Scotland.

Late evening and George Emmerson waits, still, for his sister in a dockside alehouse, idly sketching in the margins of yesterday’s newspaper to distract himself from dark thoughts about ships and storms. The howling gale beyond the leaded windows sends a cold draft creeping down his neck as the candles gutter in their sconces. He folds the newspaper and checks his pocket watch again. Where in God’s name is she?

The hours drag on until the alehouse door creaks open, straining against its hinges as Billy Stroud, George’s roommate, steps inside. Shaking out his overcoat, he approaches the fireplace, rainwater dripping from the brim of his hat. His face betrays his distress.

George stiffens. “What is it?”

“Bad news I’m afraid, George.” Stroud places a firm hand on his friend’s shoulder. “There are reports that the Forfarshire went down in the early hours. Off the Farne Islands.”

George cannot understand, scrambling to make sense of Stroud’s words. “Went down? How? Are there any survivors?”

“Seven crew. They got away in one of the quarter boats. Picked up by a fishing sloop from Montrose. Lucky buggers. They were taken to North Sunderland. The news has come from there.”

Without a moment’s hesitation, George pulls on his gloves and hat, sending his chair clattering to the floor as he rushes out into the storm, Stroud following behind.

“Where are you going, man? It’s madness out there.”

“North Sunderland,” George replies, gripping the top of his hat with both hands. “The lifeboat will have launched from there.” The impact of his words hits him like a blow to the chest as he begins to comprehend what this might mean. He places a hand on his friend’s shoulder, leaning against him for support as the wind howls furiously and the rain lashes George’s face, momentarily blinding him. “Pray for them, Stroud. Dear God, pray for my sister and her children.”

LEARNING OF HIS sister’s stricken vessel, George throws a haphazard collection of clothes into a bag and leaves his lodgings, much to the consternation of his landlady, who insists he’ll catch a chill and will never get a carriage in this weather anyway.

Not one to be easily deterred by frantic landladies or bad weather, within half an hour of learning of the Forfarshire disaster, George has secured a coachman to take him to North Sunderland on the coast of Northumberland. The fare is extortionate, but he is in no humor to haggle and allows the driver to take advantage of his urgency. It is a small price to pay to be on the way to his sister and her children. He images them sheltering in a tavern or some kind fisherwoman’s cottage, little James telling tall tales about the size of the waves and how he helped to row his mother and sister back to shore, brave as can be.

Partly to distract himself and partly from habit, George sketches as the coach rumbles along. His fingers work quickly, capturing the images that clutter his restless mind: storm-tossed ships, a lifeboat being launched, a lighthouse, barrels of herrings on the quayside, Miss Darling. Even now, the memory of her torments him. Does he remember her correctly? Is he imagining the shape of her lips, the suggestion of humor in her eyes? Why can he not forget her? She was not especially pretty, not half as pretty as Eliza in fact, but there was something about her, something more than her appearance. Miss Darling had struck George as entirely unique, as individual as the patterns on the seashells she had shown him. The truth is, he has never met anyone quite like her and it is that—her particular difference—which makes him realize how very ordinary Eliza is. It had long been expected that he would marry his cousin, so he has never paused to question it. Until now. Miss Darling has given him a reason to doubt. To question. To think. Cousin Eliza and her interfering mother have only ever given him a reason to comply.

The rain hammers relentlessly on the carriage roof as the last of the daylight fades and the wheels rattle over ruts, rocking George from side to side like a drunken sailor and sending the lanterns swinging wildly beyond the window. Exhausted, he falls into an uncomfortable bed at a dreary tavern where the driver and horses will rest for the night.

Disturbed by the storm and his fears for Sarah, George thinks about the cruel ways of the world, and how it is that some are saved and others are lost, and what he might do if he found himself on a sinking ship. He closes his eyes and prays for forgiveness for having uncharitable thoughts about Eliza. She is not a bad person, and he does not wish to think unkindly of her. But his most earnest prayer he saves for his sister and her children.

“Courage, Sarah,” he whispers into the dark. “Be brave.”

As if to answer him, the wind screams at the window, rattling the shutters violently. A stark reminder that anyone at sea will need more than prayers to help them. They will need nothing short of a miracle.

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_16953de5-1792-5af3-8c72-2d3f3970457b)

GRACE (#ulink_16953de5-1792-5af3-8c72-2d3f3970457b)

Longstone Lighthouse. 7th September, 1838

IT IS A different home we return to.

I have never been more grateful to see the familiar tower of Longstone emerge from the mist, but I also know that everything has changed, that I am changed by what has taken place. Part of my soul has shifted, too aware now of the awful fact that the world can rob a mother of her children as easily as a pickpocket might snatch a lady’s purse. But it is the sight of Mam—steadfast, resourceful Mam—waiting loyally at the boathouse steps that stirs the strongest response as I become a child, desperate for her mother’s embrace.

Her hands fly to her chest when she sees the coble. “Oh, thank the Lord! Thank the Lord!” she calls out as we pull up alongside the landing steps. “I thought you were both lost to me.”

“Help Mrs. Dawson, Mam,” I shout, trying to make myself heard above the still-shrieking wind. “Father must go back.”

“Go back?”

“There are other survivors. We couldn’t manage them all.” Mam stands rigid, immobilized by the relief of our return and the agony of learning that Father must go back. I have never raised my voice to her, but I need her help. “Mam!” I shout. “Take the woman!”

Gathering her wits, Mam offers Mrs. Dawson her arm. Too distraught to walk, Mrs. Dawson collapses onto her knees on the first step, before turning as if to jump back into the water.

I rush to her aid, speaking to her gently. “Mrs. Dawson. You must climb the steps. Mam has dry clothes and hot broth for you. You are in shock. We must get you warm and dry.”

Again, she grasps desperately at the folds in my sodden skirt, her words a rasping whisper, her voice snatched away by grief. “Help them, Miss. Please. I beg you to help them.”

I promise we will as I half carry, half drag her up the steps. “My father is a good man. He will bring them back. But he must hurry. We must go inside so that he can go back.”

The two injured men limp behind, while the other, refusing any rest and insisting he is quite unharmed, sets out again with Father to fetch the remaining survivors. I catch Father’s eyes as he takes up the oars. Without exchanging a word, I know he understands that I am begging him to be safe, but that I also understand he has to go back. I pray for him as I help Mrs. Dawson into the lighthouse.

Inside, all becomes urgent assistance and action. While Mam tends to the injured men, patching them up as best she can, I fetch more wood for the fire and fill several lamps with oil, it still being gloomy outside. I set a pot of broth on the crane over the fire and slice thick chunks of bread, glad now of the extra loaves Mam had made yesterday. I pass blankets and dry clothes around the wretched little group huddled beside the fire, grateful for the light and warmth it lends to their frozen limbs.