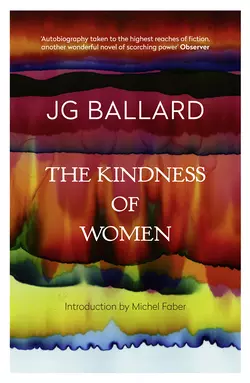

The Kindness of Women

J. G. Ballard

‘This is autobiography taken to the highest reaches of fiction, another wonderful novel of scorching power, shot through with honesty and lyricism’ ObserverThe Kindness of Women continues the story of Jim, the young boy whose experiences in Japanese-occupied Shanghai were described in Empire of the Sun. It follows his return to post-war England, setting his childhood in the context of a lifetime.Jim tries, and fails, to find stability as a medical student at Cambridge, then as a trainee RAF pilot in Canada. Having finally settled into happy family life, his world is ripped apart by domestic tragedy. He plunges into the maelstrom of the 1960s, an instigator and subject of every aspect of cultural, social and sexual revolution.We follow, in all this, the progress of a bruised mind as it tries to make sense of the upheaval around it. Turning conspicuously, as in Empire of the Sun, to the events of his own life, Ballard makes of experience fiction that is frankly startling and, at its most tender, powerfully moving.This edition is part of a new commemorative series of Ballard’s works, featuring introductions from a number of his admirers (including James Lever, Ali Smith, Hari Kunzru and Martin Amis) and brand-new cover designs.

J. G. BALLARD

The Kindness of Women

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road London W6 8JB 4thestate.co.uk (http://4thestate.co.uk)

This edition published by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in Great Britain by Harper Collins in 1991

Copyright © J. G. Ballard 1991

The right of J. G. Ballard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Introduction copyright © Michel Faber 2014

‘The Ballard Tradition’ by Will Self copyright © Will Self 2003

‘The Worst of Times’ by J. G. Ballard and Danny Danziger copyright © The Independent 1991

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins eBooks.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this e-book has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Cover by Stanley Donwood.

Ebook Edition © MAY 2012 ISBN: 9780007381166

Version: 2014-09-25

Praise (#u3f8d6067-abcd-5a58-9945-ae5733f9cd55)

From the reviews of The Kindness of Women:

‘Is Ballard our best novelist? Perhaps. He’s certainly the most interesting, the one whose account of the last half of this century has the most to tell us. A moving book – stimulating and substantial.’

New Statesman & Society

‘Ballard’s prose is cool, glassy, almost eerily unengaged; but then Jim’s life is in a sense a dreamy one, in which personal trauma and historical event become part of the same dream-scape. The Kindness of Women has a brutal spine – plenty of hardware and violence and graphic and clinical sex scenes. But it is also, in its own chilly way, enormously tender and likeable, with huge vision and ambition.’

NICK HORNBY, Sunday Times

‘Ballard offers us a fugal rather than a chronological version of his life, and readers familiar with his work will encounter the originals of the burdened, magical images that resonate through his novels and stories. A force is operating in this astonishing book that is hard to resist: a rogue intelligence in tandem with a febrile, yet lucid, imagination, that is at once mercilessly honest, trenchant and exhilaratingly extreme.’

Daily Telegraph

‘Ballard’s eye for physical detail has always been superb and it is as good as ever here. He sees the weirdness of things, and can capture that weirdness in odd verbal ways.’

CLAIRE TOMALIN, Guardian

‘Compulsively readable … unbearably moving sequences about domestic contentment, the death of “Jim’s” wife, the pleasures of suburbia, the quiet life; horrifying insights into the madness of sixties drugs and violence; dark glimpses into the strange distortions of Ballard’s mind.’

Financial Times

‘Unexpectedly moving … a worthy sequel.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Brilliant … Ballard’s wit has never been livelier. Ballard is an eerily visual writer, conjuring up dreams sharp enough to bleed. Ballard fans will relish the book’s masterful synthesis of all the strands of his imagination. Raw and tender in its beauty, and dark in its hilarity, The Kindness of Women is the capstone to a magnificent career.’

San Francisco Chronicle

‘A writer of extraordinarily distinctive vision and power. A raw physicality roils beneath the glacial surfaces of Ballard’s prose, and the novel is taut with tension between “Jim’s” cultivated detachment and Ballard’s wounded humanity. Ballard is a psychic alien, viewing the world from his suburban eyrie with a perspective formed by a unique set of experiences, peering not into the stylised futures and pasts of the sf hacks, but into the real future we already inhabit.’

Literary Review

‘A highly readable novel which looks honestly at the traumatic effects of war and gives a graphic description of the social and cultural upheavals of the past half-century.’

Sunday Times

‘A brilliant writer. The Kindness of Women is a poignantly vivid account of Ballard’s radically dislocated life. Ballard writing at the top of his powers offers an immediacy that is often visceral. His eye has never been more cinematic. The Kindness of Women is full of scenes and moments that linger hauntingly in the mind. A piercingly honest, vibrant record of a very contemporary life.

Publishers Weekly

‘He writes so confoundedly well.’

Mail on Sunday

Contents

Title Page (#u55bf4476-5e23-5ebf-a48d-6f7d6f58a428)

Copyright (#uc9fefc51-706d-56a3-ae75-001bddde0d45)

Praise

Introduction by Michel Faber

PART ONE A Season for Assassins

CHAPTER ONE Bloody Saturday

CHAPTER TWO Escape Attempts

CHAPTER THREE The Japanese Soldiers

PART TWO The Craze Years

CHAPTER FOUR The Queen of the Night

CHAPTER FIVE The Nato Boys

CHAPTER SIX Magic World

CHAPTER SEVEN The Island

CHAPTER EIGHT The Kindness of Women

CHAPTER NINE Craze People

CHAPTER TEN The Kingdom of Light

CHAPTER ELEVEN The Exhibition

CHAPTER TWELVE In the Camera Lens

CHAPTER THIRTEEN The Casualty Station

PART THREE After the War

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Into the Daylight

CHAPTER FIFTEEN The Final Programme

CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Impossible Palace

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Dream’s Ransom

‘The Ballard Tradition’ by Will Self

‘The Worst of Times’ by J. G. Ballard and Danny Danziger

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Introduction by Michel Faber (#u3f8d6067-abcd-5a58-9945-ae5733f9cd55)

Like many men scarred by war, J. G. Ballard spent much of his life determined not to talk about it. Had he died in his early fifties (not such an improbable fate, given his intake of alcohol and tobacco) only one short story, ‘The Dead Time’, would have existed to pay direct witness to his wartime experience. He preferred to divert the memories into more fantastical conceptions: drowned worlds, concrete islands, terminal beaches, atrocity exhibitions.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that he commanded his fiction to shine a documentary torch into his own life, to illuminate and perhaps exorcise his Shanghai ghosts. He confronted them first in Empire of the Sun, tackled them again from another angle in The Kindness of Women, and finally – just before he died – offered a conventionally ‘truthful’ account in his autobiography, Miracles of Life. The author who’d built his reputation on a ‘never explain, never apologise’ attitude seemed increasingly concerned that people should understand what he’d gone through and how it had affected him.

Empire of the Sun was not the book to achieve that, partly because it didn’t show what happened ‘afterwards’ to the boy who saw corpses littering the streets of his city and spent several years in a Japanese internment camp, partly because the public’s view of the novel was filtered through the lens of Steven Spielberg’s sentimental, soaringly upbeat movie adaptation. The Kindness of Women, marketed as a ‘sequel’, steered back towards the provocative style of Ballard’s earlier work, exploring the psychic fallout of horror and violence. The scene where young Jim watches four somnolent Japanese soldiers slowly murder a Chinese prisoner with telephone wire is a masterpiece of understatement and baleful resonance: even as Jim negotiates his own escape, we know that, on a deeper level, there is no escaping from such a sight.

As in Empire of the Sun, Ballard erases his real-life parents from the Lunghua camp, turning Jim into an orphan for dramatic purposes. Other than this, the events of the earlier book are handled quite differently, with a different cast of characters. Seventeen novella-like chapters fictionalise the key phases of Ballard’s life from 1937 to 1987, starting with his childhood in Shanghai where the rich, perpetually tipsy Westerners play tennis, go shopping and sidestep the growing mound of refugee bodies felled by hunger, typhus and bombs. ‘To my child’s eyes, which had seen nothing else, Shanghai was a waking dream where everything I could imagine had already been taken to its extreme.’ Those last fifteen words serve as a manifesto for all of Ballard’s novels.

Ballard was enthralled by the Surrealists, and felt that his discovery of their paintings gave his fiction its distinctive aura. The Shanghai we encounter in The Kindness of Women evokes a gallery full of unknown masterpieces by Dalí, Magritte, Delvaux and so on. The dead Chinese lying outside the bombed amusement park are ‘covered with white chalk, through which darker patches had formed, as if they were trying to camouflage themselves’ – an image worthy of De Chirico. Severed hands are eerily described as ‘mislaid’. Chauffeurs ferry the expats to abandoned battlefields where open coffins protrude ‘like drawers in a ransacked wardrobe’, spent rifle shells create ‘a roadway covered with pieces of gold’ and dead infantrymen lie in ‘drowned trenches, covered to their waists by the earth, as if asleep in a derelict dormitory’. Forced to spectate upon such scenes in the company of well-dressed ladies ‘fanning away the flies’, Jim gets a nightmarish education in the emotional and moral disconnects that would define the 20th century.

If the strangeness of Shanghai is meant to foreshadow Auschwitz, Vietnam and the contextless chaos of modern media, Jim’s medical studies in post-war England tell us a lot about Ballard’s values as a prose-writer. When he begins to dissect a cadaver, a friend warns him: ‘You’ll have to cut away all the fat before you reach the fascia.’ It’s an appropriate metaphor for Ballard’s clinical approach to narrative, an odd mixture of focus and nonchalance. While he liked to set himself apart from oh-so-literary avant-gardists by insisting that he was ‘an old-fashioned storyteller at heart’, he was impatient with the conventions that had underpinned respectable mainstream fiction since the Victorians. Surrealism’s emphasis on the inexplicable and Sci-Fi’s tolerance for haphazard characterisation and unnaturalistic dialogue suited his own inclinations, even if some readers might find these things alienating.

It is in the area of physicality – especially sex – that Ballard’s style jars most with the conventions of British fiction. It’s hard to imagine another English author who could come up with a sentence like ‘Her small, detergent-chafed hands, with their smell of lipstick, semen and rectal mucus, ran across my forehead.’ Frequent references to penises, labia, pelvises and prostates underscore Jim’s contention that ‘Gray’s Anatomy is a far greater novel than Ulysses.’ Even in a chapter that celebrates the miracle of birth and the love between a husband and wife, we see Jim pushing Miriam’s prolapsed rectum back into her anus during her uterine contractions. Readers who discover Ballard via the Booker-shortlisted, essentially sexless Empire of the Sun might find such explicitness repellent; indeed, once Ballard was famous, he began to receive letters from disgruntled people who regretted reading his other books. Yet, though Ballard shares William Burroughs’ disregard for ‘good taste’, his focus on the visceral is not a mere shock tactic. Unable to believe in an immortal soul or any of the transcendent mysticism that offers comfort to more ‘spiritual’ writers, he is unashamedly fascinated by the flesh – every pore, blemish and scar of it. The scenes in The Kindness of Women where Jim dissects the woman’s carcass inspire some of Ballard’s most tender, most respectful, most reverent writing.

For all his modernity, however, Ballard was formed by the fashions of a previous age; he could never quite shake the values instilled in him by Biggles and Boy’s Own. His ambivalent fascination with soldiers, his disdain for the defeatism of the British in Singapore, and his lifelong love affair with fighter planes set him apart from the long-haired peaceniks of later generations. It was not Ballard’s date of birth per se that caused this disjunct: Burroughs and Timothy Leary were both much older, but it’s impossible to imagine them standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Jim and the RAF ‘honour guard’ at the funeral of a Spitfire pilot. As this scene from The Kindness of Women shows, Ballard could be cynical about many things, but not the tragic dignity of fallen soldiers.

Much of The Kindness of Women is set in the 1960s and early 1970s, when Ballard hatched the stories that made his reputation as a social anatomist. His relationship with the times was atypical. Indifferent to music, immune to the charms of psychedelia, and bemused by the idealism of hippies, he felt less enamoured of the 1960s than many of his fellow experimenters. He approved of the shake-up of the class system, and celebrated the rise of the literary counterculture that promoted his work, but in The Kindness of Women he chooses to present the sixties as an era driven to psychosis by a steady diet of drugs, assassinations, war trauma and TV. ‘The demise of feeling and emotion, the death of affect, presided like a morbid sun over the playground of that ominous decade.’

If society is insane and the world has turned toxic, what hope is there? The kindness of women? Is it through female nurture that Jim (and his author) survives and thrives? So the book’s title invites us to think. Closer examination renders that notion dubious: Jim’s mother is absent; his sulky nanny is employed merely to mind him; Jim’s occasional lover Sally Mumford seems bent on addictive self-destruction; and even his wife Miriam, for all her support, is restless for change, regarding marriage as a ‘cul de sac … a detour from the main road’. In any case, just like Ballard’s own wife Mary, she dies suddenly, leaving him to bring up three children on his own. The novel might have been more appropriately titled The Allure of Closure. Certainly in the final chapters, the contrived sex scenes in which any remaining significant women from Jim’s past pop up to make love to him suggest a last-ditch authorial attempt to bind everything together with artificial dialogue and genital fluids. If any females can truly be said to have rescued Jim (and J. G.), it is, I think, his daughters, who provided their boozy, bereaved dad with all the stability, solace, love and happiness he needed.

Ballard was not an emotionless man and he did not write emotionless fiction. The coolness which many critics have characterised as archetypically ‘Ballardian’ is not as chilly as it seems. In The Kindness of Women, warm feelings – of pity, of passion, of parental love, of fond friendship – course richly beneath the surface of the skin but, like veins that retreat or collapse when a hypodermic needle seeks to penetrate them, they elude the forensic approach of Ballard’s pen. The Kindness of Women is a curious hybrid, combining – not always successfully – the merciless thematic rigour of his earlier, more fantastical work and a new humanity that dispelled the deviant cyborg of myth. Many years before, when Crash was rejected by a publisher whose editorial assistant had branded him ‘beyond psychiatric help’, Ballard took the comment as encouraging proof that he’d hit a nerve. By 1991, he no longer revelled in such opprobrium.

In truth, Ballard’s basic decency was always there, even in his most outrageous tales. He wanted people to grow up well-loved and safe in families like the one he maintained in suburban Shepperton, rather than descending into madness and cannibalism like the trapped hordes in High-Rise. It is a measure of how obtuse the guardians of public morality continue to be that Ballard was ever accused of being a nihilistic pervert or a champion of orgasmic car crashes. Like all satirists, he assumed that humans should behave compassionately and morally. Grieved by their failure to do so, he expressed his alarm – not with earnest hand-wringing, but by ushering us straight to a dystopian fait accompli. In short, he shanghaied us.

Us? I have to admit that for me, Ballard’s work was an oddly recent discovery. I say ‘oddly’ because he was so integral to the other cultural phenomena I investigated during my formative years that it’s hard to believe I could have passed him by. As a fan of underground comics, I was intimate with Gaetano Liberatore’s surreally cruel, visceral dys- topias – Crash on steroids. I evangelised on behalf of Phoebe Gloeckner, who, in one of the few works of hers I didn’t possess, crafted anatomical phantasmagoria for a revised edition of The Atrocity Exhibition. I swayed to Throbbing Gristle’s ‘Hamburger Lady’ (pure Ballard in sonic form), chilled out to Paul Schütze’s ‘Vermillion Sands’, and sang along to Hawkwind’s ‘High Rise’. David Cronenberg was one of my favourite directors. I was hugely impressed by the Industrial Culture handbooks issued by Re/Search in the 1980s, rereading them many times but somehow never getting around to the ones devoted to Ballard.

Looking back on it now, my avoidance is inexplicable. Was I subconsciously worried that his fiction would unduly influence mine? In my own output, the occasional short story like ‘Explaining Coconuts’ strikes me as intoxicatingly Ballardian and I feel a peculiar pleasure to have explored such territory independently of his lead. But still I feel the poignancy of his absence from my life while he was alive. I would have liked to send him a letter praising him for his uncompromising vision and his often beautiful prose. Maybe this is it.

Fearn by Tain, 2014

PART I A Season for Assassins (#u3f8d6067-abcd-5a58-9945-ae5733f9cd55)

1 (#u3f8d6067-abcd-5a58-9945-ae5733f9cd55)

Bloody Saturday (#u3f8d6067-abcd-5a58-9945-ae5733f9cd55)

Every afternoon in Shanghai during the summer of 1937 I rode down to the Bund to see if the war had begun. As soon as lunch was over I would wait for my mother and father to leave for the Country Club. While they changed into tennis clothes, ambling in a relaxed way around their bedroom, it always amazed me that they were so unconcerned by the coming war, and unaware that it might break out just as my father served his first ball. I remember pacing up and down with all the Napoleonic impatience of a 7-year-old, my toy soldiers drawn up on the carpet like the Japanese and Chinese armies around Shanghai. At times it seemed to me that I was keeping the war alive singlehandedly.

Ignoring my mother’s laughter as she flirted with my father, I would watch the sky over Amherst Avenue. At any moment a squadron of Japanese bombers might appear above the department stores of downtown Shanghai and begin to bomb the Cathedral School. My child’s mind had no idea how long a war would last, whether a few minutes or even, conceivably, an entire afternoon. My one fear was that, like so many exciting events I always managed to miss, the war would be over before I noticed that it had begun.

Throughout the summer everyone in Shanghai spoke about the coming war between China and Japan. At my mother’s bridge parties, as I helped myself to the plates of small chow, I listened to her friends talking about the shots exchanged on July 7 at the Marco Polo bridge in Peking, which had signalled Japan’s invasion of northern China. A month had passed without Chiang Kai-shek ordering a counter-attack, and there were rumours that the German advisers to the Generalissimo were urging him to abandon the northern provinces and fight the Japanese nearer his stronghold at Nanking, the capital of China. Slyly, though, Chiang had decided to challenge the Japanese at Shanghai, two hundred miles away at the mouth of the Yangtse, where the American and European powers might intervene to save him.

As I saw for myself whenever I cycled down to the Bund, huge Chinese armies were massing around the International Settlement. On Friday, August 13, as soon as my mother and father settled themselves into the rear seats of the Packard, I wheeled my bicycle out of the garage, pumped up its tyres and set off on the long ride to the Bund. Olga, my White Russian governess, assumed that I was visiting David Hunter, a friend who lived at the western end of Amherst Avenue. A young woman of moods and strange stares, Olga was only interested in trying on my mother’s wardrobe and was glad to see me gone.

I reached the Bund an hour later, but the concourse was so crowded with frantic office workers that I could scarcely get near the waterfront landing stages. Ringing my warning bell, I pedalled past the clanking trams, the wheel-locked rickshaws and their exhausted coolies, the gangs of aggressive beggars and pickpockets. Refugees from Chapei and Nantao streamed into the International Settlement, shouting up at the impassive facades of the great banks and trading houses along the Bund. Thousands of Chinese troops were dug into the northern suburbs of Shanghai, facing the Japanese garrison in their concession at Yangtsepoo. Standing on the steps of the Cathay Hotel as the doorman held my cycle, I could see the Whangpoo river filled with warships. There were British destroyers, sloops and gunboats, the USS Augusta and a French cruiser, and the veteran Japanese cruiser Idzumo, which my father told me had helped to sink the Russian Imperial Fleet in 1905.

Despite this build-up of forces, the war obstinately refused to declare itself that afternoon. Disappointed, I wearily pedalled back to Amherst Avenue, my school blazer scuffed and stained, in time for tea and my favourite radio serial. Hugging my grazed knees, I stared at my armies of lead soldiers, and adjusted their lines to take account of the latest troop movements that I had seen as I rode home. Ignoring Olga’s calls, I tried to work out a plan that would break the stalemate, hoping that my father, who knew one of the Chinese bankers behind Chiang Kai-shek, would pass on my muddled brain-wave to the Generalissimo.

Baffled by all these problems, which were even more difficult than my French homework, I wandered into my parents’ bedroom. Olga was standing in front of my mother’s full-length mirror, a fur cape over her shoulders. I sat at the dressing-table and rearranged the hair-brushes and perfume bottles, while Olga frowned at me through the glass as if I were an uninvited visitor who had strayed from another of the houses in Amherst Avenue. I had told my mother that Olga played with her wardrobe, but she merely smiled at me and said nothing to Olga.

Later I realised that this 17-year-old daughter of a once well-to-do Minsk family was scarcely more than a child herself. On my cycle rides I had been shocked by the poverty of the White Russian and Jewish refugees who lived in the tenement districts of Hongkew. It was one thing for the Chinese to be poor, but it disturbed me to see Europeans reduced to such a threadbare state. In their faces there was a staring despair that the Chinese never showed. Once, when I cycled past a dark tenement doorway, an old Russian woman told me to go away and shouted that my mother and father were thieves. For a few days I had believed her.

The refugees stood in their patched fur coats on the steps of the Park Hotel, hoping to sell their old-fashioned jewellery. The younger women had painted their mouths and eyes, trying bravely to cheer themselves up, I guessed. They called to the American and British officers going into the hotel, but what they were selling my mother had never been able to say – they were giving French and Russian lessons, she told me at last.

Always worried by my homework, and aware that many of the White Russians spoke excellent French, I had asked Olga if she would give me a French lesson like the young women at the Park Hotel. She sat on the bed while I hunted through my pocket dictionary, shaking her head as if I were some strange creature at a zoo. Worried that I had hurt her feelings by referring to her family’s poverty, I gave Olga one of my silk shirts, and asked her to pass it on to her invalid father. She had held it in her hands for fully five minutes, like one of the vestments used in the communion services at Shanghai Cathedral, before returning it silently to my wardrobe. Already I had noticed that the White Russian governesses possessed a depth of female mystery that the mothers of my friends never remotely approached.

‘Yes, James?’ Olga hung the fur cape on its rack, and slipped my mother’s breakfast gown over her shoulders. ‘Have you finished your holiday book? You’re very restless today.’

‘I’m thinking about the war, Olga.’

‘You’re thinking about it every day, James. You and General Chiang think about it all the time. I’m sure he would like to meet you.’

‘Well, I could meet him …’ As it happened, I did sometimes feel that the Generalissimo was not giving his fullest attention to the war. ‘Olga, do you know when the war will begin?’

‘Hasn’t it already begun? That’s what everyone says.’

‘Not the real war, Olga. The war in Shanghai.’

‘Is that the real war? Nothing is real in Shanghai, James. Why don’t you ask your father?’

‘He doesn’t know. I asked him after breakfast.’

‘That’s a pity. Are there many things he doesn’t know?’

Still wearing the breakfast robe, Olga sat on my father’s bed, her hand stroking the satin cover and smoothing away the creases. She was caressing the imprint of my father’s shoulders, and for a moment I wondered if she was going to slip between the sheets.

‘He does know many things, but …’

‘I can remind you, James, it’s Friday the 13th. Is that a good day for starting a war?’

‘Hey, Olga …!’ This news brightened everything. I rushed to the window – superstitions, I often noticed, had a habit of coming true. ‘I’ll tell you if I see anything.’

Olga stood behind me, calming me with a hand on my ear. Much as she loved the intimacy of my mother’s clothes and the ripe odour of my father’s riding jacket, she rarely touched me. She stared at the distant skyline along the Bund. Smoke rose from the coal-burning boilers of the older naval vessels. The black columns jostled for space as the warships changed their moorings, facing up to each other with sirens blasting. The darker light gave Olga’s face the strong-nosed severity of the mortuary statues I had seen in Shanghai cemetery. She lifted the breakfast robe, staring through the veil of its fine fabric as if seeing a dream of vanished imperial Russia.

‘Yes, James, I think they’ll start the war for you today …’

‘Say, thanks, Olga.’

But before the war could start, my mother and father returned unexpectedly from the Country Club. With them were two British officers in the Shanghai Volunteer Force, wearing their tight Great War uniforms. I tried to join them in my father’s study, but my mother took me into the garden and in a strained way pointed to the golden orioles drinking from the edge of the swimming pool.

I was sorry to see her worried, as I knew that my mother, unlike Olga, was one of those people who should never be worried by anything. Trying not to annoy her, I spent the rest of the afternoon in my playroom. I listened to the sirens of the battle-fleets and marshalled my toy soldiers. On the next day, Bloody Saturday as it would be known, my miniature army at last came to life.

I remember the wet monsoon that blew through Shanghai during that last night of the peace, drowning the sounds of Chinese sniper fire, and the distant boom of Japanese naval guns striking at the Chinese shore batteries at Woosung. When I woke into the warm, sticky air the storm had passed, and the washed neon signs of the city shone ever more vividly.

At breakfast my mother and father were already dressed in their golfing clothes, though when they left in the Packard a few minutes later my father was at the wheel, the chauffeur beside him, and they had not taken their golf clubs.

‘Jamie, you’re to stay home today,’ my father announced, staring through my eyes as he did when he had unfathomable reasons of his own. ‘You can finish your Robinson Crusoe.’

‘You’ll meet Man Friday and the cannibals.’ My mother smiled at this treat in store, but her eyes were as flat as they had been when our spaniel was run over by the German doctor in Columbia Road. I wondered if Olga had died during the night, but she was watching from the door, pressing the lapels of her dressing gown to her neck.

‘I’ve already met the cannibals.’ However exciting, Crusoe’s shipwreck palled by comparison with the real naval disaster about to take place on the Whangpoo river. ‘Can we go to the Tattoo? David Hunter’s going next week …’

The Military Tattoo staged by soldiers of the British garrison was filled with booming cannon, thunderflashes and bayonet charges, and recreated the bravest clashes of the Great War, the battles of Mons, Ypres and the Gallipoli landings. In a sense, the make-believe of the Tattoo might be as close as I would ever get to a real war.

‘Jamie, we’ll see – they may have to cancel the Tattoo. The soldiers are very busy.’

‘I know. Then can we go to the Hell-drivers?’ This was a troupe of American dare-devil drivers, who crashed their battered Fords and Chevrolets through wooden barricades covered with flaming gasoline. The sight of these thrillingly rehearsed accidents for ever eclipsed the humdrum street crashes of Shanghai. ‘You promised …’

‘The Hell-drivers aren’t here any more. They’ve gone back to Manila.’

‘They’re getting ready for the war.’ In my mind I could see these laconic Americans, in their dashing goggles and aviator’s suits, crashing through the flaming walls as they answered a salvo from the Idzumo. ‘Can I come to the golf club?’

‘No! Stay here with Olga! I won’t tell you again …’ My father’s voice had an edge of temper that I had noticed since the labour troubles at his cotton mill in Pootung, on the east bank of the river. I wondered why Olga watched him so closely when he was angry. Her toneless eyes showed a rare and almost hungry alertness, the expression I felt on my face when I was about to tuck into an ice-cream sundae. One of the communist union organisers who threatened to kill my father had stared at him in the same way as we sat in the Packard outside his office in the Szechuan Road. I worried that Olga wanted to kill my father and eat him.

‘Do I have to? Olga listens all the time to French dance music.’

‘Well, you listen with her,’ my mother rejoined. ‘Olga can teach you how to dance.’

This was a prospect I dreaded, an even greater torture than the promise of unending peace. When Olga touched me, it was in a distant but oddly intimate way. As I lay in bed at night she would sometimes undress in my bathroom with the door ajar. Later I guessed that this was her way of proving to herself that I no longer existed. As soon as my parents left for the golf club my one intention was to give her the slip.

‘David said that Olga—’

‘All right!’ Irritated by the ringing telephone, which the servants were too nervous to answer, my father relented. ‘You can see David Hunter. But don’t go anywhere else.’

Why was he frightened of Shanghai? Despite his quick temper, my father easily gave in, as if events in the world were so uncertain that even my childish nagging carried weight. He was too distracted to play with my toy soldiers, and he often looked at me in the same firm but dejected way in which the headmaster of the Cathedral School gazed at the assembled boys during morning prayers. When he walked to the car he stamped his spiked golf shoes, leaving deep marks in the gravel, like footprints staking a claim to Crusoe’s beach.

Even before the Packard had left the drive, Olga was reclining on the verandah with my mother’s copies of Vogue and the Saturday Evening Post. At intervals she called out to me, her voice as remote as the sirens on the river buoys at Woosung. I guessed that she knew about my afternoon cycle rides around Shanghai. She was well aware that I might be kidnapped or robbed of my clothes in one of the back alleys of the Bubbling Well Road. Perhaps the terrors of the Russian civil war, the long journey with her parents through Turkey and Iraq to this rootless city at the mouth of the Yangtse, had so disoriented her that she no longer cared if the child in her charge was killed.

‘Who did your father let you see, James?’

‘David Hunter. He’s my closest friend. I’m going now, Olga.’

‘You have so many closest friends. Tell me if the war begins, James.’

She waved, and I was gone. In fact, the last person in Shanghai I wanted to see was David. During the summer holidays my schoolfriends and I played homeric games of hide-and-seek that lasted for weeks and covered the whole of Shanghai. As I drove with my mother to the Country Club or drank iced tea in the Chocolate Shop I was constantly watching for David, who might break away from his amah and lunge through the crowd to tap me on the shoulder. These games added another layer of strangeness and surprise to a city already too strange.

I wheeled my cycle from the garage, buttoned my blazer and set off down the drive. Legs whirling like the blades of an eggbeater, I swerved into Amherst Avenue and overtook a column of peasants trudging through the western suburbs of the city. Refugees from the countryside now occupied by the Chinese and Japanese armies, they plodded past the great houses of the avenue, their few possessions on their backs. They laboured towards the distant towers of downtown Shanghai, unaware of everything but the hard asphalt in front of them, ignoring the chromium bumpers and blaring horns of the Buicks and Chryslers whose Chinese chauffeurs were trying to force them off the road.

Standing on my pedals, I edged past a rickshaw loaded with bales of matting, on which perched two old women clutching the walls and roof of a dismantled hovel. I could smell their bodies, crippled by a lifetime of heavy manual work, and the same rancid sweat and hungry breath of all impoverished peasants. But the night’s rain still soaked their black cotton tunics, which gleamed in the sunlight like the rarest silks on the fabric counters in the Sun Sun department store, as if the magic of Shanghai had already begun to transform these destitute people.

What would happen to them? My mother was studiously vague about the refugees, but Olga told me in her matter-of-fact way that most of them soon died of hunger or typhus in the alleys of Chapei. Every morning on my way to school I passed the trucks of the Shanghai Municipal Authority that toured the city, collecting the hundreds of bodies of Chinese who had died during the night. I liked to think that only the old people died, though I had seen a dead boy of my own age sitting against the steel entrance grille of my father’s office block. He held an empty cigarette tin in his white hands, probably the last gift to him from his family before they abandoned him. I hoped that the others became bar-tenders and waiters and Number 3 girls at the Great World Amusement Park, and my mother said that she hoped so too.

Putting aside these thoughts, and cheered by the day ahead, I reached the Avenue Joffre and the long tree-lined boulevards of the French Concession that would carry me to the Bund. Quick-tempered French soldiers guarded the sand-bagged checkpoint by the tramline terminus. They stared warily at the empty sky and spat at the feet of the passing Chinese, hating this ugly city to which they had been exiled across the world. But I felt a surge of excitement on entering Shanghai. To my child’s eyes, which had seen nothing else, Shanghai was a waking dream where everything I could imagine had already been taken to its extreme. The garish billboards and nightclub neon signs, the young Chinese gangsters and violent beggars watching me keenly as I pedalled past them, were part of an overlit realm more exhilarating than the American comics and radio serials I so adored.

Shanghai would absorb everything, even the coming war, however fiercely the smoke might pump from the warships in the Whangpoo river. My father called Shanghai the most advanced city in the world, and I knew that one day all the cities on the planet would be filled with radio-stations, hell-drivers and casinos. Outside the Canidrome the crowds of Chinese and Europeans were pushing their way into the greyhound arena, unconcerned by the Kuomintang armies around the city waiting to attack the Japanese garrison. Gamblers jostled each other by the betting booths of the jai alai stadium, and the morning audience packed the entrance of the Grand Theatre on the Nanking Road, eager to see the latest Hollywood musical, Gold-Diggers of 1937.

But of all the places of wonder, the Great World Amusement Park on the Avenue Edward VII most amazed me, and contained the magnetic heart of Shanghai within its six floors. Unknown to my parents, the chauffeur often took me into its dirty and feverish caverns. After collecting me from school, Yang would usually stop the car outside the Amusement Park and carry out one or other of the mysterious errands that occupied a large part of his day.

A vast warehouse of light and noise, the Amusement Park was filled with magicians and fireworks, slot machines and sing-song girls. A haze of frying fat gleamed in the air, and formed a greasy film on my face, mingling with the smell of joss-sticks and incense. Stunned by the din, I would follow Yang as he slipped through the acrobats and Chinese actors striking their gongs. Medicine hawkers lanced the necks of huge white geese, selling the cups of steaming blood to passers-by as the ferocious birds stamped their feet and gobbled at me when I came too close. While Yang murmured into the ears of the mahjong dealers and marriage brokers, I peered between his legs at the exposed toilets in the lavatory stalls and at the fearsome idols scowling over the temple doorways, at the mysterious peep-shows and massage booths with their elegant Chinese girls, infinitely more terrifying than Olga, in embroidered high-collared robes slit to expose their thighs.

This Saturday, however, the Great World was closed. The dance platforms, dried-fish stalls and love-letter booths had been dismantled, and the municipal authorities had turned the ancient building into a refugee camp. Hundreds of frantic Chinese were forcing their way into the ramshackle structure, held back by a cordon of Sikh police in sweat-stained khaki turbans. Like a team of carpet-beaters, the Sikhs lashed at the broken-toothed peasant farmers with their heavy bamboo staves. A burly British police sergeant waved his service revolver at the monkey-like old women with bound feet who tried to push past him, their callused fists punching his chest.

I stood on the opposite sidewalk, listening to the sirens sounding from the river, a great moaning of blind beasts challenging each other. For the first time I guessed that war of a kind had already come to Shanghai. Buffeted by the Chinese office clerks, I steered my cycle along the gutter, and squeezed past an armoured riot van of the Shanghai Police, with its twin-handled Thompson machine-gun mounted above the driver’s cabin.

Breathless, I rested in the doorway of a funeral parlour. The elderly undertaker sat among the coffins at the rear of the shop, white fingers flicking at the beads of his abacus. The clicks echoed among the empty coffins, and reminded me of the superstition that Yang had graphically described, snapping his fingers in front of my nose. ‘When a coffin cracks, the Chinese undertaker knows he will sell it …’

I listened to the abacus, trying to see if the coffins gave a twitch when they cracked. Soon a lot of coffins in Shanghai would be cracking. The old man’s fingers flicked faster as he watched me with his vain, dreamy eyes. Was he adding up all those who were going to die in Shanghai, trying to reach my own number, somewhere among the cracking coffins and clicking beads?

Behind me a car horn blared into the crowd. A white Lincoln Zephyr was forcing its way through the traffic, hemmed in by the rickshaw coolies and refugees clambering into the entrance of the Amusement Park. David Hunter knelt on the rear seat beside his Australian nanny, blond hair in his eyes as he squinted at the pavement. Forgetting the coffins and the clicking abacus, I pushed my cycle along the gutter, aware that David would see me once the traffic had cleared.

An air-raid klaxon sounded from one of the office buildings, overlaid by a heavy, sustained rumble like a collapsing sky. A shouting coolie strode towards me, bales of firewood on a bamboo pole across his shoulders, from which the veins stood out like bloated worms. Without pausing, he kicked the cycle out of my hands. I bent down to rub my bruised knees, and tried to reach the handlebars, but the rush of feet knocked me to the ground. Winded, I lay among the old lottery tickets, torn newspapers and straw sandals as the white Lincoln cruised past. Playing with his blond fringe behind the passenger window, David frowned at me in his pointy way, unable to recognise me but puzzled why an English boy in a Cathedral School blazer had chosen this of all moments to roll about in a filthy gutter.

The klaxon wailed, keening at the sky. Chinese office workers, women clerks and hotel waiters were running down the Nanking Road from the Bund. An immense cloud of white steam rose from the Whangpoo river behind them, flashes of gunfire reflected in its lower surface. Around it circled three twin-engined bombing planes, banking as they flew through its ashen billows.

A squadron of Chinese aircraft were bombing the Idzumo and the Japanese cotton-mills at Yangtsepoo, little more than a mile from the Bund across the Garden Bridge. The boom of heavy guns jarred the windows of the office buildings in the Thibet Road. A tram clanked past me towards the Bund, its passengers leaping into the road. High above them, on the roof of the Socony-Vacuum building, stood a party of unconcerned Europeans in white tennis clothes, binoculars in hand, pointing out details of the spectacle to each other.

Had the war really started? I was expecting something as organised and disciplined as the Military Tattoo. The planes lumbered through the air, as if the pilots were bored by their targets and were circling the Idzumo simply to fill in time before returning to their airfield. The French and British warships sat at their moorings near the Pootung shore, signal lights blinking softly from their bridges, a vaguely curious commentary on the bombing display down-river.

Mounting my cycle, I straightened the handlebars and brushed the dust from my blazer – the officious junior masters at the school liked to roam the city in their spare time, reporting anyone untidily dressed. I set off after the empty tram, steering between the polished rails. When it neared the Bund the conductor dismounted, swearing at the driver and waving his leather cash bag. The tram’s warning bell clanged at the empty street, watched by groups of Chinese clerks pressing themselves into the doorways of the office buildings.

A water-spout rose from the choppy waves beside the bows of the Idzumo, hovered for a second and then surged upwards in a violent cascade. Arms of hurtling foam punched through the air and soared high above the radio aerials and mast-tops of the ancient cruiser. A second squadron of Chinese bombers swept in formation down the Whangpoo, midway between the Bund and the Pootung shore, where my father’s cotton mill lay behind a veil of greasy smoke. One of the planes lagged behind the others, the pilot unable to keep his place in the formation. He rolled his wings from side to side, like the stunt pilots at the aerobatic displays at Hungjao Airfield.

‘Jamie, leave your bike! Come with us!’

The white fenders of the Lincoln Zephyr had crept behind me. David’s Australian nanny was shouting to me, her arms stretched across the shoulders of the nervous Chinese chauffeur. Steadying her straw hat with one hand, she waved me towards the car. Nurse Arnold had always been easy-going and friendly, so much more pleasant to me than Olga, and I was surprised by her bad temper. David had recognised me, a gleam of triumph in his eyes. He brushed the blond hair from his forehead, aware that he was about to make the first capture of our marathon game of hide-and-seek.

The Idzumo was laying smoke around itself. Scrolls of oily vapour uncoiled along its bows. Through the sooty clouds I could see the tremble of anti-aircraft fire, the sounds lost in the monotonous drone of the Chinese bombers.

‘Jamie, you stupid …!’

I pedalled away from them into a wall of noise and smoke. Glass was falling from the windows of my father’s building in Szechuan Road. Office girls darted from the doorways, their white blouses speckled with fine needles. My front wheel jolted over a piece of masonry shaken loose from a cornice. While I straightened the pedals a low-flying bomber veered away from the Japanese anti-aircraft fire. It flew above the Bund, exposed its open bombing racks and released two bombs towards the empty sampans moored to the quay.

Eager to watch the water-spouts, I mounted my cycle, but a pair of powerful hands gripped my armpits. A uniformed British police sergeant whirled me off my feet. He kicked away my cycle and crouched by the steps of the Socony building. As he held me against his hip the metal hammer of his revolver tore the skin from my knee.

Exploding debris burst between the hotels and department stores of the Nanking Road and filled the street with white ash. A wave of burning air struck my chest and threw me to the ground beside the sergeant. Chinese office workers with raised hands ran towards us through the billows of dust, blood streaming from their foreheads. One of the stray bombs had fallen into the Palace Hotel, and the other into the Avenue Edward VII beside the Great World Amusement Park. The buildings in the Szechuan Road rocked around us, shaking a cascade of broken glass and roofing tiles into the street.

Beside the kerb a matronly Eurasian woman stepped from her car, blood running from her ear. She touched it discreetly with a silk handkerchief as the police sergeant propelled me towards her.

‘Keep him here!’ He jerked my shoulders, as if I were a sleeping doll, and he were trying to wake me. ‘Lad, you stay with her!’

When he ran towards the Nanking Road the Eurasian woman released my hand, waving me away and too distracted to be bothered with me. Blood seeped down my leg, staining my white socks. Looking at the thin trickle, I noticed that I had lost one of my shoes. My head felt empty, and I touched my face to make sure that it was still there. The explosion had sucked all the air from the street and it was difficult to breathe. Gesturing to me in an absent way, the Eurasian woman wandered through the debris, wiping the dust from her leather handbag. The blood ran from her ear as she stared at the broken glass, trying to recognise the windows of her own apartment.

Far away, police sirens had begun to wail, and an ambulance of the Shanghai Volunteer Force drove past, the glass spitting under its tyres. I realised that I was deaf, but everything around me was deaf too, as if the world could no longer hear itself. Two hundred yards from the Great World Amusement Park I could see that most of the building had vanished. Smoke rose from its exposed floors, and an arcing electric cable sparked and jumped like a swaying firecracker.

Hundreds of dead Chinese were lying in the street among the crushed rickshaws and burnt-out cars. Their bodies were covered with white chalk, through which darker patches had formed, as if they were trying to camouflage themselves. I walked among them, tripping over an old amah who lay on her back, pouting face covered with powder, scolding me with her last grimace. An office clerk without his arms sat against the rear wheel of a gutted bus. Everywhere hands and feet lay among the debris of the Amusement Park – fragments of joss sticks and playing cards, gramophone records and dragon masks, part of the head of a stuffed whale, all blanched by the dust. A bolt of silk had unravelled across the street, a white bandage that wound around the lumps of masonry and the mislaid hands.

I waited for someone to call to me, but the air was silent and ringing, like the pause after an unanswered alarm. I could no longer hear my feet as they cracked the blades of broken glass. I walked back to the Hunters’ Lincoln Zephyr. The chauffeur stood in his pallid uniform by the open driver’s door, brushing away the dust that covered the windshield. David sat alone in the back, hands pressed to his mouth. He ignored me and stared at the torn seat-cover with fixed eyes, as if he never wanted to see me again.

I looked through the broken windows at Nurse Arnold, who was lying across the front seat. Her hair fell across her face, forced by the explosion into her mouth. Her hands were open, white palms exposed, displaying to any passer-by that she had washed them carefully before she died.

Later, when he visited me in Shanghai General Hospital, David asked me about the blood on my leg. Curiously, this was the only blood that he had seen on Bloody Saturday.

‘I was wounded by the bomb,’ I told him.

I had begun to boast in a small way, but more truthfully than I realised. One thousand and twelve people, almost all Chinese refugees, were killed by the high-explosive bomb that fell beside the Great World Amusement Park. As everyone constantly repeated, proud that Shanghai had again excelled itself, this was the largest number killed by a single bomb in the history of aerial warfare. My own trivial injury, caused by the police sergeant’s revolver, numbered me among the thousand and seven who were wounded. Although not the youngest of those injured, I liked to think that I was No. 1007, which I firmly inked on my arm.

Months of fierce fighting took place around the International Settlement before the Japanese were able to drive the Chinese from Shanghai, during which tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians were to perish. But the Avenue Edward VII bomb, dropped in error by a Chinese pilot, had a special place in the mythology of war, a potent example of how mass death could now fall from the air.

At the time, as I rested in my bed at Shanghai General, I was thinking not of the bomb beside the Amusement Park, but of my army of toy soldiers on the floor of my playroom. Even as the rescue workers of the Shanghai Volunteer Force carried me to their ambulance through the dusty streets I knew that I needed to rearrange their battle lines. I had seen the real war for which I had waited so impatiently, and I felt vaguely guilty that there were no models of dead Chinese in my boxes of brightly painted soldiers. Now and then my ears would clear for a brief moment, and the eerie sounds of Japanese artillery drumming at the hospital window seemed to call to me from another world.

Within a few days, however, my memories of the bombing had begun to fade. I tried to remember the dust and debris in the Szechuan Road, but the confused images in my head had merged with the newsreels I had seen of the Spanish civil war and the filmed manoeuvres of the French and British armies. The fighting in the western suburbs of Shanghai veiled the window with curtains of smoke which the autumn winds drew aside to reveal the burning tenements of Nantao. The nurses and doctors who tested my ears with their tuning forks, Olga and my school-friends, my mother and father on their evening visits, were like actors in the old silent films that David Hunter’s father screened for us against his dining-room wall. The bomb that destroyed the Amusement Park and killed more than a thousand people had become part of those films.

It was three months before I could go back to Amherst Avenue. Artillery shells from the rival Chinese and Japanese howitzers at Siccawei station and Hungjao were passing over the roof of our house, and my mother and father had moved to an apartment in the French Concession. The battle for Shanghai continued around the perimeter of the International Settlement, shaking the doors of our apartment and often jamming the elevator. Once Olga and I were trapped for an hour in the metal cage. She, who was usually so silent, spent the time delivering a torrent of words at me, well aware that I could hear not a single one. I often wondered if she was accusing me of starting the war, though in Olga’s eyes that would have been the least of my crimes.

In November the Chinese armies began to withdraw from Shanghai, retreating up the Yangtse to Nanking. They left behind them the devastated suburbs, which the Japanese occupied, ringing the International Settlement with their tanks and machine-gun posts. We were then safe to return to Amherst Avenue. While my parents talked to the servants I ran up to my playroom, eager to see my army of toy soldiers again.

The miniature battle of Shanghai had been swept aside. Broken soldiers lay scattered among my train set and model cars. Someone, perhaps Coolie or Number 2 Boy, had used my Robinson Crusoe as an ash tray, stubbing his half-smoked cigarettes into the cover as he watched nervously from the windows. I thought of reporting him to my father, but I knew that the servants had been as frightened as I was.

I gathered the soldiers together and later tried to play with them, but the games seemed more serious than those that had filled the playroom floor before Bloody Saturday. When David and I set out our rival armies it worried me that we were secretly trying to kill each other. Thinking of the severed hands and feet I had seen outside the Amusement Park, I put the soldiers away in their box.

But at Christmas there were new sets of soldiers to take their place, Seaforth Highlanders in khaki battle-kilts and Coldstream Guards in bearskins. To my surprise, life in the International Settlement was unaffected by the months of fighting around the city, as if the bitter warfare had been little more than a peripheral entertainment of a particularly brutal kind, like the public strangulations in the Old City. The neon signs shone ever more brightly over Shanghai’s four hundred nightclubs. My father played cricket at the Country Club, while my mother organised her bridge and dinner parties. I served as a page at a lavish wedding at the French Club. The Bund was crowded with trading vessels and sampans loaded with miles of brightly patterned calico which my father’s printing and finishing works produced for the elegant Chinese women who thronged the Settlement. The great import-export houses of the Szechuan Road were busier than before. The radio stations broadcast their American adventure serials, the bars and dance halls were filled with Number 2 and Number 3 girls, and the British garrison staged its Military Tattoo. Even the Hell-drivers returned from Manila to crash their cars. While the distant war between Japan and Chiang Kai-shek continued in the hinterland of China the roulette wheels turned in the casinos, spinning their dreams of old Shanghai.

As if to remind themselves of the war, one Sunday afternoon my parents and their friends drove out to tour the battlegrounds in the countryside to the west of Shanghai. We had attended a reception given by the British Consul General, and the wives wore their best silk gowns, the husbands their smartest grey suits and panamas. When our convoy of cars stopped at the Keswick Road check-point I was waiting for the shabby Japanese soldiers to turn us back, but they beckoned us through without comment, as if we were worth scarcely a glance.

Three miles into the countryside we stopped on a deserted road. I remember the battlefield under the silent sky, and the burnt-out village near a derelict canal. The chauffeurs opened the doors, and we stepped on to a roadway covered with pieces of gold. Hundreds of spent rifle cartridges lay at our feet. Abandoned trenchworks ran between the burial mounds, from which open coffins protruded like drawers in a ransacked wardrobe. Scattered around us were remnants of torn webbing, empty ammunition boxes, boots and helmets, rusting bayonets and signal flares. Beyond rifle pits filled with water was an earth redoubt, pulverised by the Japanese artillery. The carcase of a horse lay by its gun emplacement, legs raised stiffly in the sunlight.

Together we gazed at this scene, the ladies fanning away the flies, their husbands murmuring to each other, like a group of investors visiting the stage-set of an uncompleted war film. Led by my father and Mr Hunter, we strolled towards the canal, and stared at the Chinese soldiers floating in the shallow water. Dead infantrymen lay everywhere in the drowned trenches, covered to their waists by the earth, as if asleep in a derelict dormitory.

Beside me, David was tittering to himself. He was impatient to go home, and I could see his jarred eyes hidden behind his fringe. He turned his back on his mother, but the dead battlefield surrounded him on every side. Deliberately scuffing his polished shoes, he kicked the cartridge cases at the sleeping soldiers.

I cupped my hands over my ears, trying to catch the sound that would wake them.

2 (#ulink_6c3c0545-7e6b-5200-8834-daba6505d8a5)

Escape Attempts (#ulink_6c3c0545-7e6b-5200-8834-daba6505d8a5)

All day rumours had swept Lunghua that there would soon be an escape from the camp. Shivering on the steps of the children’s hut, I waited for Sergeant Nagata to complete the third of the day’s emergency roll-calls. Usually, at the first hint of an escape attempt, the Japanese sentries would close the gates with a set of heavy padlocks – a symbolic gesture, as David Hunter’s father remarked, since anyone planning to escape from Lunghua hardly intended to walk through the front gates. It was far easier to step through the perimeter wire, as I and the older children did every day, hunting for a lost tennis ball or setting useless bird-traps for the American sailors.

Symbolic or not, the gesture served a practical purpose, like so much of Japanese ceremony. Closing the gates was a sign to any Chinese collaborators in the surrounding countryside that a security alert was under way, and told the few informers within the camp – always the last to know what was going on – to keep their eyes open.

However, the gates hung slackly from their rotting posts, and the sentries stamped their ragged boots on the cold earth, even more bored than ever. Almost all the Japanese soldiers, like Private Kimura, were the sons of peasant farmers, so poor that they regarded Lunghua, with its two thousand prisoners and its unlimited stocks of cricket bats and tennis rackets, as a haven of affluence. The unheated cement dormitories at least received an erratic supply of electric power, an unimagined luxury for the Japanese peasant.

I whistled through my fingers, trying to attract Kimura’s attention, but he ignored me and gazed at the Chinese beggars waiting patiently outside the gates for the scraps that never came. As if depressed by the untended paddy-fields, Kimura frowned at the steam that rose from his broad nostrils. I imagined him thinking of his mother and father tending their modest crops in a remote corner of Hokkaido. Neither of us had seen our parents during the years of the war, though in many ways Kimura was more alone than I was. In the panic after the Japanese seizure of the International Settlement I had been separated from my mother and father when we left our hotel on the Bund. Nonetheless, I was confident that I would see them again, even if their faces had begun to fade in my mind. But Kimura would almost certainly die here, among these empty rice fields, when the Japanese made their last stand against the Americans at the mouth of the Yangtse.

I lined my fingers on his shaven head, as if aiming Sergeant Nagata’s Mauser pistol, and snapped my thumb.

‘Jamie, I heard that.’ A tall, 14-year-old English girl, Peggy Gardner, joined me at the doorway, her thin shoulders hunched against the cold. She nudged me with a bony elbow, as if to make me miss my aim. ‘Who did you shoot?’

‘Private Kimura.’

‘You shot him yesterday.’ Peggy shook her head over this, her face grave but forgiving, a favourite pose. ‘Private Kimura is your friend.’

‘I shoot my friends too.’ Friends, surprisingly, made even more tempting targets than enemies. ‘Besides, Private Kimura isn’t really my friend.’

‘Not half. Mrs Dwight thinks you’re an informer. Why do you have to shoot everyone?’

Sergeant Nagata emerged from D Block, scowling over his roster board, the British block commander behind him. Peggy pushed me against the door and forced my hands into my back. Glaring suspiciously at every blade of grass, Sergeant Nagata would not appreciate serving as my practice target. I leaned against Peggy, glad to feel her strong wrists and smell the cold, reassuring scent of her body. She was always trying to wrestle with me, for reasons I was not yet ready to explore.

‘Why, Jamie? You’ve shot everyone in Lunghua by now. Is it because you want to be alone here?’

‘I haven’t shot Mrs Dwight.’ This busybodying missionary was one of the English widows who supervised the eight boys and girls in the children’s hut, all war-orphans separated from parents interned in the other camps near Shanghai and Nanking. Rather than make sure that we had our fair share of the falling food ration, Mrs Dwight was concerned for our spiritual welfare, as I heard her explain to the mystified camp commandant, Mr Hyashi. For Mrs Dwight this chiefly involved my sitting silently in the freezing hut over my Latin homework – anything rather than the restless errand-running and food-scavenging that occupied every moment of my day. To Mrs Dwight I was a ‘free soul’, a term that contained not a hint of approval. Spiritual well-being seemed to be inversely proportional to the amount of food one received, which perhaps explained why Mrs Dwight and the other missionaries considered their pre-war activities in the famine-ridden provinces of northern China such a marked success.

‘When the war’s over,’ I said darkly, ‘I’ll ask my father to shoot Mrs Dwight with a real gun. He dislikes missionaries, you know.’

‘Jamie …!’ Peggy tried to box my ears. A doctor’s daughter from Tsingtao, she was a year older than me and pretended to be easily shocked. As I knew, she was far more protective than Mrs Dwight. When I was ill it was Peggy who had looked after me, giving me some of the younger children’s food. One day I would repay her. She ruled the children’s hut in a firm but high-minded way, and I was her greatest challenge. I liked to keep up a steady flow of small outrages, but recently I had noticed Peggy’s depressing tendency to imitate Mrs Dwight, modelling herself on this starchy widow as if she needed the approval of an older woman. I preferred the strong-willed girl who stood up to the boys in her class, rescued the younger children from bullies, and had a certain thin-hipped stylishness with which I had still to come to terms.

‘If your father’s going to shoot anyone,’ Peggy remarked, ‘he should start with Dr Sinclair.’ This vile-tempered clergyman was the headmaster of the camp school. ‘He’s worse than Sergeant Nagata.’

‘Peggy …?’ I felt a rush of concern for her. ‘Did he hit you?’

‘He nearly tried. He always looks at me in that smiley way. As if I was his daughter and he needed to punish me.’

Only that afternoon one of the ten-year-olds had come back to the hut with a stinging red forehead. Our real education at the Lunghua school came from learning to read Dr Sinclair’s moods.

‘Did you tell Mrs Dwight?’

‘She wouldn’t listen. Just because they’re kind to us, they think they can do anything. She’s more frightened of him than I am.’

‘He doesn’t hit everybody.’

‘He’ll hit you one day.’

‘I won’t let him.’ This was idle talk, and my next Latin class could prove me wrong. But so far I had avoided the clergyman’s heavy hands. I had noticed that Dr Sinclair left alone the children of the more well-to-do British parents. He never hit David Hunter, however much David tried to provoke him, and only cuffed the sons of factory foremen, Eurasian mothers or officers in the Shanghai Police. What I could never understand was why the parents failed to protest when their children returned to their rooms in G Block with ears bleeding from the clergyman’s signet ring. It was almost as if the parents accepted this reminder of their lowly position in Shanghai’s British community.

Bored with it all, and deciding to show off in front of Peggy, I picked up a stone from the step and hurled it high into the air over the parade ground.

‘Jamie, you’re in trouble! Sergeant Nagata saw that …’

I froze against the door. The sergeant was standing on the gravel path twenty feet from the children’s hut. As he stared at me he filled his lungs, his face bearing the weight of some slow but vast emotion. However complicated the British at Lunghua seemed to me, there was no doubt that Sergeant Nagata found them infinitely more mysterious, a stiff-necked people whose armies in Singapore had surrendered without a fight but nonetheless acted as if they had won the war. For some reason he kept a close watch on me, as if I were a key to this conundrum.

Why he should have marked out one 13-year-old boy among the two hundred children I never discovered. Did he think I was trying to escape, or serving as a secret courier between the dormitory blocks? In fact, most of the adults in the camp shied away from me when I loomed up to them, eager to play blindfold chess or offer my views on the progress of the war and the latest Japanese aerial tactics. My nerveless energy soon tired them and, besides, I was forever looking to the future. No one knew when the war would end – perhaps in 1947 or even 1948 – and the internees coped with the endless time by erasing it from their lives. The busy programme of lectures and concert parties of the first year had been abandoned. The internees rested in their cubicles, reading their last letters from England, roused briefly by the iron wheels of the food carts. Mrs Dwight was not the only one to see the dangers of an overactive imagination.

‘Jamie, look out …’ Mischievously, Peggy pushed me through the doorway. I stumbled on to the gravel, but Sergeant Nagata had more pressing matters on his mind than a head-count of the war children. Slapping his roster-board, he led his entourage back to the guard-house. I was sorry to see him go – I enjoyed squaring up to Sergeant Nagata. There was something about the Japanese, their seriousness and stoicism, that I admired. One day I might join the Japanese Air Force, just as my other heroes, the American Flying Tigers, had flown for Chiang Kai-shek.

‘Why isn’t he coming?’ Disappointed, Peggy shivered in her patched cardigan. ‘You could have escaped – think what Mrs Dwight would say. She’d have you banished.’

‘I am banished.’ Not sure what this meant, I added: ‘There might be an escape tonight.’

‘Who said? Are you going with them?’

‘Basie and Demarest told me.’ The American merchant seamen were a fund of inaccurate information, much of it deliberately propagated. As it happened, escape could not have been further from my mind. My parents were interned at Soochow, far too dangerous a distance to walk, and the British in charge might not let me in. They were terrified of being infected with typhus or cholera by prisoners transferred from other camps.

‘I would have gone with them, but Basie’s wrong.’ I pointed to the guard-house, where Private Kimura was saluting the sergeant with unnecessary zeal. ‘They always close the gates when Sergeant Nagata thinks there’s going to be an escape.’

‘Well …’ Peggy hid her pale cheeks behind her arms and shrewdly studied the Japanese. ‘Perhaps they want us to escape.’

‘What?’ This struck me with the force of revelation. I knew from the secret camp radio that by now, November 1943, the war had begun to turn against the Japanese. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and their rapid advance across the Pacific, they had suffered huge defeats at the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. American reconnaissance planes had appeared over Shanghai, and the first bombing raids would soon follow. Along the Whangpoo river Japanese military activity had increased, and anti-aircraft batteries were dug in around the airfield to the north of the camp. Lunghua pagoda was now a heavily armed flak tower equipped with powerful searchlights and rapid-fire cannon. The Korean and Japanese guards at Lunghua were more aggressive towards the prisoners, and even Private Kimura was irritable when I showed him my drawings of the sinking of the Repulse and the Prince of Wales, the British battleships sent to the bottom of the South China Sea by Japanese dive-bombers.

Far more worrying, the food ration had been cut. The sweet potatoes and cracked wheat – a coarse cattle feed – were warehouse scrapings, filled with dead weevils and rusty nails. Peggy and I were hungry all the time.

‘Jamie, suppose …’ Intrigued by her own logic, Peggy smiled to herself. ‘Suppose the Japanese want us to escape, so they won’t have to feed us? Then they’d have more to eat.’

She waited for me to react, and reached out to reassure me, seeing that she had gone too far. She knew that any threat to the camp unsettled me more than all the petty snubs. What I feared most was not merely that the food ration would be cut again, but that Lunghua camp, which had become my entire world, might degenerate into anarchy. Peggy and I would be the first casualties. If the Japanese lost interest in their prisoners we would be at the mercy of the bandit groups who roamed the countryside, renegade Kuomintang and deserters from the puppet armies. Gangs of single men from E Block would seize the food store behind the kitchens, and Mrs Dwight would have nothing to offer the children except her prayers.

I felt Peggy’s arm around my shoulders, and listened to her heart beating through the thin wall of her chest. Often she looked unwell, but I was determined to keep her out of the camp hospital. Lunghua hospital was not a place that made its patients better. We needed extra rations to survive the coming winter, but the food store was more carefully locked than the cells in the guard-house.

As the all-clear sounded, the internees emerged from the doorways of their blocks, staring at the camp as if seeing it for the first time. The great tenement family of Lunghua began to rouse itself. Listless women hung their faded washing and sanitary rags on the lines behind G Block. A crowd of children raced to the parade ground, led by David Hunter, who was wearing a pair of his father’s leather shoes that I so coveted. As he moved around the camp my eyes rarely left his feet. Mrs Hunter had offered me her golfing brogues, but I had been too proud to accept, an act of foolishness I regretted, since my rubber sneakers were now as ragged as Private Kimura’s canvas boots. The war had led to a coolness between David and myself. I envied him his parents, and all my attempts to attach myself to a sympathetic adult had been rebuffed. Only Basie and the Americans were friendly, but their friendliness depended on my running errands for them.

Mrs Dwight approached the children’s hut, her fussy eyes taking in everything like a busy broom. She smiled approvingly at Peggy, who was holding a crude metal bucket soldered together from a galvanized-iron roofing sheet dislodged by the monsoon storms. With the tepid water she brought back from the heating station Peggy would wash the younger children and flush the lavatory.

‘Peggy, are you off to Waterloo?’

‘Yes, Mrs Dwight.’ Peggy assumed a pained stoop, and the missionary patted her affectionately.

‘Ask Jamie to help you. He’s doing nothing.’

‘He’s busy thinking.’ Artlessly, with a knowing eye in my direction, Peggy added: ‘Mrs Dwight, Jamie’s planning to escape.’

‘Really? I thought he’d escaped long ago. I’ve got something new for him to think about. Jamie, tomorrow you’re moving to G Block. It’s time for you to leave the children’s hut.’

I emerged from one of the hunger reveries into which I often slipped. The apartment houses of the French Concession were visible along the horizon, reminding me of the old Shanghai before the war, and the Christmas parties when my father hired a troupe of Chinese actors to perform a nativity play. I remembered the games of two-handed bridge on my mother’s bed, my carefree cycle rides around the International Settlement, and the Great World Amusement Park with its jugglers and acrobats and sing-song girls. All of them seemed as remote as the films I had seen in the Grand Theatre, sitting beside Olga while she stared in her bored way through Snow White and Pinocchio.

‘Why, Mrs Dwight? I need to stay with Peggy until the war’s over.’

‘No.’ Mrs Dwight frowned at the prospect, as if there was something improper about it. ‘You’ll be happier with boys of your own age.’

‘Mrs Dwight, I’m never happy with boys of my own age. They play games all the time.’

‘That may be. You’re going to live with Mr and Mrs Vincent.’

Mrs Dwight expanded on the attractions of the Vincents’ small room, which I would share with this chilly couple and their sick son. Peggy was looking sympathetically at me, the bucket clasped to her chest, well aware of the new challenge I faced.

But for once I was thinking in the most practical terms. I knew that I would be easily dominated by the Vincents, the morose amateur jockey and his glacial wife, who would resent my presence in their small domain. I might try to bribe Mrs Vincent with the promise of a reward for being kind to me, which my father would pay after the war. Unhappily, this choice carrot failed to energise the Lunghua adults, so sunk were they in their torpor.

If I was going to bribe the Vincents I needed something more down to earth, the most important commodity in Lunghua. Ignoring Mrs Dwight, I seized my cinder-tin from beneath my bunk, shouted a goodbye to Peggy and set off at a run for the kitchens.

Spitting in the cold wind, the glowing cinders seethed across the ash-tip behind the kitchens. Naked except for their cotton shorts and wooden clogs, the stokers stepped from the steaming doorway beside the furnace, ashes flaming on their shovels. Now that the evening meal of rice congee had been prepared, Mr Sangster and Mr Bowles were raking the furnace and banking the fires down for the night. I waited on the summit of the ash-tip, enjoying the sickly fumes in the fading light, while I watched the Japanese night-fighters warming up at Lunghua airfield.

‘Look out, young Jim.’ Mr Sangster, a sometime accountant with the Shanghai Power Company, sent a cascade of cinders towards my feet. The ashes covered my sneakers and stung my toes through the rotting canvas. I scampered back, wondering how many extra rations had helped to build Mr Sangster’s burly shoulders. But Mrs Sangster had been a friend of my mother’s, and the horseplay was a means of steering the most valuable cinders towards me. Small favours were the secret currency of Lunghua.

Two other cinder-pickers joined me on the ash-tip – the elderly Mrs Tootle, who shared a cubicle with her sister in the women’s hut and brewed unpleasant herbal teas from the weeds and wildflowers along the perimeter fence; and Mr Hopkins, the art master at the Cathedral School, who was forever trying to warm his room in G Block for his malarial wife. He poked at the cinders with a wooden ruler, while Mrs Tootle scraped about with an old pair of sugar tongs. Neither had the speed and flair of my bent-wire tweezers. A modest treasure of half-burnt anthracite lay in these cinder heaps, but few of the internees would stir themselves to scavenge for warmth. They preferred to huddle together in their dormitories, complaining about the cold.

Squatting on my haunches, I picked out the pieces of coke, some no larger than a peanut, that had survived the riddling. I flicked them into my biscuit tin, to be traded when it was full for an extra sweet potato or a pre-war copy of Reader’s Digest or Popular Mechanics, which the American sailors monopolised. These magazines had kept me going through the long years, feeding a desperate imagination. Mrs Dwight was forever criticising me for dreaming too much, but my imagination was all that I had.