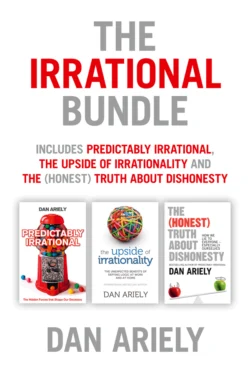

The Irrational Bundle

The Irrational Bundle

Dan Ariely

Dan Ariely's three New York Times bestselling books on his groundbreaking behavioral economics research, Predictably Irrational, The Upside of Irrationality, and The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, are now available for the first time in a single volume.This ebook has been optimised for reading on colour screens. The majority of the text will appear the same across all devices, but there is one exercise that will not work unless viewed on a colour screen.

Contents

Predictably Irrational (#ucd7933d9-6ddd-5ed6-af9a-951796d68a41)

The Upside of Irrationality (#u95761935-4285-5e02-b00c-c431b16ff2cf)

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty (#u1dd4ffa2-875b-5172-b7fb-43aded837297)

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

To my mentors, colleagues, and students—

who make research exciting

Contents

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

How an Injury Led Me to Irrationality and to the Research Described Here

CHAPTER 1 - The Truth about Relativity

Why Everything Is Relative—Even When It Shouldn’t Be

CHAPTER 2 - The Fallacy of Supply and Demand

Why the Price of Pearls—and Everything Else—Is Up in the Air

CHAPTER 3 - The Cost of Zero Cost

Why We Often Pay Too Much When We Pay Nothing

CHAPTER 4 - The Cost of Social Norms

Why We Are Happy to Do Things, but Not When We Are Paid to Do Them

CHAPTER 5 - The Power of a Free Cookie

CHAPTER 6 - The Influence of Arousal

Why Hot Is Much Hotter Than We Realize

CHAPTER 7 - The Problem of Procrastination and Self-Control

Why We Can’t Make Ourselves Do What We Want to Do

CHAPTER 8 - The High Price of Ownership

Why We Overvalue What We Have

CHAPTER 9 - Keeping Doors Open

Why Options Distract Us from Our Main Objective

CHAPTER 10 - The Effect of Expectations

Why the Mind Gets What It Expects

CHAPTER 11 - The Power of Price

Why a 50-Cent Aspirin Can Do What a Penny Aspirin Can’t

CHAPTER 12 - The Cycle of Distrust

CHAPTER 13 - The Context of Our Character, Part I

Why We Are Dishonest, and What We Can Do about It

CHAPTER 14 - The Context of Our Character, Part II

Why Dealing with Cash Makes Us More Honest

CHAPTER 15 - Beer and Free Lunches

What Is Behavioral Economics, and Where Are the Free Lunches?

THANKS

LIST OF COLLABORATORS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND ADDITIONAL READINGS

PRAISE FOR PREDICTABLY IRRATIONAL

Introduction

How an Injury Led Me to Irrationality and

to the Research Described Here

I have been told by many people that I have an unusual way of looking at the world. Over the last 20 years or so of my research career, it’s enabled me to have a lot of fun figuring out what really influences our decisions in daily life (as opposed to what we think, often with great confidence, influences them).

Do you know why we so often promise ourselves to diet, only to have the thought vanish when the dessert cart rolls by?

Do you know why we sometimes find ourselves excitedly buying things we don’t really need?

Do you know why we still have a headache after taking a one-cent aspirin, but why that same headache vanishes when the aspirin costs 50 cents?

Do you know why people who have been asked to recall the Ten Commandments tend to be more honest (at least immediately afterward) than those who haven’t? Or why honor codes actually do reduce dishonesty in the workplace?

By the end of this book, you’ll know the answers to these and many other questions that have implications for your personal life, for your business life, and for the way you look at the world. Understanding the answer to the question about aspirin, for example, has implications not only for your choice of drugs, but for one of the biggest issues facing our society: the cost and effectiveness of health insurance. Understanding the impact of the Ten Commandments in curbing dishonesty might help prevent the next Enron-like fraud. And understanding the dynamics of impulsive eating has implications for every other impulsive decision in our lives—including why it’s so hard to save money for a rainy day.

My goal, by the end of this book, is to help you fundamentally rethink what makes you and the people around you tick. I hope to lead you there by presenting a wide range of scientific experiments, findings, and anecdotes that are in many cases quite amusing. Once you see how systematic certain mistakes are—how we repeat them again and again—I think you will begin to learn how to avoid some of them.

But before I tell you about my curious, practical, entertaining (and in some cases even delicious) research on eating, shopping, love, money, procrastination, beer, honesty, and other areas of life, I feel it is important that I tell you about the origins of my somewhat unorthodox worldview—and therefore of this book. Tragically, my introduction to this arena started with an accident many years ago that was anything but amusing.

ON WHAT WOULD otherwise have been a normal Friday afternoon in the life of an eighteen-year-old Israeli, everything changed irreversibly in a matter of a few seconds. An explosion of a large magnesium flare, the kind used to illuminate battlefields at night, left 70 percent of my body covered with third-degree burns.

The next three years found me wrapped in bandages in a hospital and then emerging into public only occasionally, dressed in a tight synthetic suit and mask that made me look like a crooked version of Spider-Man. Without the ability to participate in the same daily activities as my friends and family, I felt partially separated from society and as a consequence started to observe the very activities that were once my daily routine as if I were an outsider. As if I had come from a different culture (or planet), I started reflecting on the goals of different behaviors, mine and those of others. For example, I started wondering why I loved one girl but not another, why my daily routine was designed to be comfortable for the physicians but not for me, why I loved going rock climbing but not studying history, why I cared so much about what other people thought of me, and mostly what it is about life that motivates people and causes us to behave as we do.

During the years in the hospital following my accident, I had extensive experience with different types of pain and a great deal of time between treatments and operations to reflect on it. Initially, my daily agony was largely played out in the “bath,” a procedure in which I was soaked in disinfectant solution, the bandages were removed, and the dead particles of skin were scraped off. When the skin is intact, disinfectants create a low-level sting, and in general the bandages come off easily. But when there is little or no skin—as in my case because of my extensive burns—the disinfectant stings unbearably, the bandages stick to the flesh, and removing them (often tearing them) hurts like nothing else I can describe.

Early on in the burn department I started talking to the nurses who administered my daily bath, in order to understand their approach to my treatment. The nurses would routinely grab hold of a bandage and rip it off as fast as possible, creating a relatively short burst of pain; they would repeat this process for an hour or so until they had removed every one of the bandages. Once this process was over I was covered with ointment and with new bandages, in order to repeat the process again the next day.

The nurses, I quickly learned, had theorized that a vigorous tug at the bandages, which caused a sharp spike of pain, was preferable (to the patient) to a slow pulling of the wrappings, which might not lead to such a severe spike of pain but would extend the treatment, and therefore be more painful overall. The nurses had also concluded that there was no difference between two possible methods: starting at the most painful part of the body and working their way to the least painful part; or starting at the least painful part and advancing to the most excruciating areas.

As someone who had actually experienced the pain of the bandage removal process, I did not share their beliefs (which had never been scientifically tested). Moreover, their theories gave no consideration to the amount of fear that the patient felt anticipating the treatment; to the difficulties of dealing with fluctuations of pain over time; to the unpredictability of not knowing when the pain will start and ease off; or to the benefits of being comforted with the possibility that the pain would be reduced over time. But, given my helpless position, I had little influence over the way I was treated.

As soon as I was able to leave the hospital for a prolonged period (I would still return for occasional operations and treatments for another five years), I began studying at Tel Aviv University. During my first semester, I took a class that profoundly changed my outlook on research and largely determined my future. This was a class on the physiology of the brain, taught by professor Hanan Frenk. In addition to the fascinating material Professor Frenk presented about the workings of the brain, what struck me most about this class was his attitude to questions and alternative theories. Many times, when I raised my hand in class or stopped by his office to suggest a different interpretation of some results he had presented, he replied that my theory was indeed a possibility (somewhat unlikely, but a possibility nevertheless)—and would then challenge me to propose an empirical test to distinguish it from the conventional theory.

Coming up with such tests was not easy, but the idea that science is an empirical endeavor in which all the participants, including a new student like myself, could come up with alternative theories, as long as they found empirical ways to test these theories, opened up a new world to me. On one of my visits to Professor Frenk’s office, I proposed a theory explaining how a certain stage of epilepsy developed, and included an idea for how one might test it in rats.

Professor Frenk liked the idea, and for the next three months I operated on about 50 rats, implanting catheters in their spinal cords and giving them different substances to create and reduce their epileptic seizures. One of the practical problems with this approach was that the movements of my hands were very limited, because of my injury, and as a consequence it was very difficult for me to operate on the rats. Luckily for me, my best friend, Ron Weisberg (an avid vegetarian and animal lover), agreed to come with me to the lab for several weekends and help me with the procedures—a true test of friendship if ever there was one.

In the end, it turned out that my theory was wrong, but this did not diminish my enthusiasm. I was able to learn something about my theory, after all, and even though the theory was wrong, it was good to know this with high certainty. I always had many questions about how things work and how people behave, and my new understanding—that science provides the tools and opportunities to examine anything I found interesting—lured me into the study of how people behave.

With these new tools, I focused much of my initial efforts on understanding how we experience pain. For obvious reasons I was most concerned with such situations as the bath treatment, in which pain must be delivered to a patient over a long period of time. Was it possible to reduce the overall agony of such pain? Over the next few years I was able to carry out a set of laboratory experiments on myself, my friends, and volunteers—using physical pain induced by heat, cold water, pressure, loud sounds, and even the psychological pain of losing money in the stock market—to probe for the answers.

By the time I had finished, I realized that the nurses in the burn unit were kind and generous individuals (well, there was one exception) with a lot of experience in soaking and removing bandages, but they still didn’t have the right theory about what would minimize their patients’ pain. How could they be so wrong, I wondered, considering their vast experience? Since I knew these nurses personally, I knew that their behavior was not due to maliciousness, stupidity, or neglect. Rather, they were most likely the victims of inherent biases in their perceptions of their patients’ pain—biases that apparently were not altered even by their vast experience.

For these reasons, I was particularly excited when I returned to the burn department one morning and presented my results, in the hope of influencing the bandage removal procedures for other patients. It turns out, I told the nurses and physicians, that people feel less pain if treatments (such as removing bandages in a bath) are carried out with lower intensity and longer duration than if the same goal is achieved through high intensity and a shorter duration. In other words, I would have suffered less if they had pulled the bandages off slowly rather than with their quick-pull method.

The nurses were genuinely surprised by my conclusions, but I was equally surprised by what Etty, my favorite nurse, had to say. She admitted that their understanding had been lacking and that they should change their methods. But she also pointed out that a discussion of the pain inflicted in the bath treatment should also take into account the psychological pain that the nurses experienced when their patients screamed in agony. Pulling the bandages quickly might be more understandable, she explained, if it were indeed the nurses’ way of shortening their own torment (and their faces often did reveal that they were suffering). In the end, though, we all agreed that the procedures should be changed, and indeed, some of the nurses followed my recommendations.

My recommendations never changed the bandage removal process on a greater scale (as far as I know), but the episode left a special impression on me. If the nurses, with all their experience, misunderstood what constituted reality for the patients they cared so much about, perhaps other people similarly misunderstand the consequences of their behaviors and, for that reason, repeatedly make the wrong decisions. I decided to expand my scope of research, from pain to the examination of cases in which individuals make repeated mistakes—without being able to learn much from their experiences.

THIS JOURNEY INTO the many ways in which we are all irrational, then, is what this book is about. The discipline that allows me to play with this subject matter is called behavioral economics, or judgment and decision making (JDM).

Behavioral economics is a relatively new field, one that draws on aspects of both psychology and economics. It has led me to study everything from our reluctance to save for retirement to our inability to think clearly during sexual arousal. It’s not just the behavior that I have tried to understand, though, but also the decision-making processes behind such behavior—yours, mine, and everybody else’s. Before I go on, let me try to explain, briefly, what behavioral economics is all about and how it is different from standard economics. Let me start out with a bit of Shakespeare:

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals. —from Act II, scene 2, of Hamlet

The predominant view of human nature, largely shared by economists, policy makers, nonprofessionals, and everyday Joes, is the one reflected in this quotation. Of course, this view is largely correct. Our minds and bodies are capable of amazing acts. We can see a ball thrown from a distance, instantly calculate its trajectory and impact, and then move our body and hands in order to catch it. We can learn new languages with ease, particularly as young children. We can master chess. We can recognize thousands of faces without confusing them. We can produce music, literature, technology, and art—and the list goes on and on.

Shakespeare is not alone in his appreciation for the human mind. In fact, we all think of ourselves along the lines of Shakespeare’s depiction (although we do realize that our neighbors, spouses, and bosses do not always live up to this standard). Within the domain of science, these assumptions about our ability for perfect reasoning have found their way into economics. In economics, this very basic idea, called rationality, provides the foundation for economic theories, predictions, and recommendations.

From this perspective, and to the extent that we all believe in human rationality, we are all economists. I don’t mean that each of us can intuitively develop complex game-theoretical models or understand the generalized axiom of revealed preference (GARP); rather, I mean that we hold the basic beliefs about human nature on which economics is built. In this book, when I mention the rational economic model, I refer to the basic assumption that most economists and many of us hold about human nature—the simple and compelling idea that we are capable of making the right decisions for ourselves.

Although a feeling of awe at the capability of humans is clearly justified, there is a large difference between a deep sense of admiration and the assumption that our reasoning abilities are perfect. In fact, this book is about human irrationality—about our distance from perfection. I believe that recognizing where we depart from the ideal is an important part of the quest to truly understand ourselves, and one that promises many practical benefits. Understanding irrationality is important for our everyday actions and decisions, and for understanding how we design our environment and the choices it presents to us.

My further observation is that we are not only irrational, but predictably irrational—that our irrationality happens the same way, again and again. Whether we are acting as consumers, businesspeople, or policy makers, understanding how we are predictably irrational provides a starting point for improving our decision making and changing the way we live for the better.

This leads me to the real “rub” (as Shakespeare might have called it) between conventional economics and behavioral economics. In conventional economics, the assumption that we are all rational implies that, in everyday life, we compute the value of all the options we face and then follow the best possible path of action. What if we make a mistake and do something irrational? Here, too, traditional economics has an answer: “market forces” will sweep down on us and swiftly set us back on the path of righteousness and rationality. On the basis of these assumptions, in fact, generations of economists since Adam Smith have been able to develop far-reaching conclusions about everything from taxation and health-care policies to the pricing of goods and services.

But, as you will see in this book, we are really far less rational than standard economic theory assumes. Moreover, these irrational behaviors of ours are neither random nor senseless. They are systematic, and since we repeat them again and again, predictable. So, wouldn’t it make sense to modify standard economics, to move it away from naive psychology (which often fails the tests of reason, introspection, and—most important—empirical scrutiny)? This is exactly what the emerging field of behavioral economics, and this book as a small part of that enterprise, is trying to accomplish.

AS YOU WILL see in the pages ahead, each of the chapters in this book is based on a few experiments I carried out over the years with some terrific colleagues (at the end of the book, I have included short biographies of my amazing collaborators). Why experiments? Life is complex, with multiple forces simultaneously exerting their influences on us, and this complexity makes it difficult to figure out exactly how each of these forces shapes our behavior. For social scientists, experiments are like microscopes or strobe lights. They help us slow human behavior to a frame-by-frame narration of events, isolate individual forces, and examine those forces carefully and in more detail. They let us test directly and unambiguously what makes us tick.

There is one other point I want to emphasize about experiments. If the lessons learned in any experiment were limited to the exact environment of the experiment, their value would be limited. Instead, I would like you to think about experiments as an illustration of a general principle, providing insight into how we think and how we make decisions—not only in the context of a particular experiment but, by extrapolation, in many contexts of life.

In each chapter, then, I have taken a step in extrapolating the findings from the experiments to other contexts, attempting to describe some of their possible implications for life, business, and public policy. The implications I have drawn are, of course, just a partial list.

To get real value from this, and from social science in general, it is important that you, the reader, spend some time thinking about how the principles of human behavior identified in the experiments apply to your life. My suggestion to you is to pause at the end of each chapter and consider whether the principles revealed in the experiments might make your life better or worse, and more importantly what you could do differently, given your new understanding of human nature. This is where the real adventure lies.

And now for the journey.

CHAPTER 1

The Truth about Relativity

Why Everything Is Relative—Even

When It Shouldn’t Be

One day while browsing the World Wide Web (obviously for work—not just wasting time), I stumbled on the following ad, on the Web site of a magazine, the Economist.

I read these offers one at a time. The first offer—the Internet subscription for $59—seemed reasonable. The second option—the $125 print subscription—seemed a bit expensive, but still reasonable.

But then I read the third option: a print and Internet subscription for $125. I read it twice before my eye ran back to the previous options. Who would want to buy the print option alone, I wondered, when both the Internet and the print subscriptions were offered for the same price? Now, the print-only option may have been a typographical error, but I suspect that the clever people at the Economist’s London offices (and they are clever—and quite mischievous in a British sort of way) were actually manipulating me. I am pretty certain that they wanted me to skip the Internet-only option (which they assumed would be my choice, since I was reading the advertisement on the Web) and jump to the more expensive option: Internet and print.

But how could they manipulate me? I suspect it’s because the Economist’s marketing wizards (and I could just picture them in their school ties and blazers) knew something important about human behavior: humans rarely choose things in absolute terms. We don’t have an internal value meter that tells us how much things are worth. Rather, we focus on the relative advantage of one thing over another, and estimate value accordingly. (For instance, we don’t know how much a six-cylinder car is worth, but we can assume it’s more expensive than the four-cylinder model.)

In the case of the Economist, I may not have known whether the Internet-only subscription at $59 was a better deal than the print-only option at $125. But I certainly knew that the print-and-Internet option for $125 was better than the print-only option at $125. In fact, you could reasonably deduce that in the combination package, the Internet subscription is FREE! “It’s a bloody steal—go for it, governor!” I could almost hear them shout from the riverbanks of the Thames. And I have to admit, if I had been inclined to subscribe I probably would have taken the package deal myself. (Later, when I tested the offer on a large number of participants, the vast majority preferred the Internet-and-print deal.)

So what was going on here? Let me start with a fundamental observation: most people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context. We don’t know what kind of racing bike we want—until we see a champ in the Tour de France ratcheting the gears on a particular model. We don’t know what kind of speaker system we like—until we hear a set of speakers that sounds better than the previous one. We don’t even know what we want to do with our lives—until we find a relative or a friend who is doing just what we think we should be doing. Everything is relative, and that’s the point. Like an airplane pilot landing in the dark, we want runway lights on either side of us, guiding us to the place where we can touch down our wheels.

In the case of the Economist, the decision between the Internet-only and print-only options would take a bit of thinking. Thinking is difficult and sometimes unpleasant. So the Economist’s marketers offered us a no-brainer: relative to the print-only option, the print-and-Internet option looks clearly superior.

The geniuses at the Economist aren’t the only ones who understand the importance of relativity. Take Sam, the television salesman. He plays the same general type of trick on us when he decides which televisions to put together on display:

36-inch Panasonic for $690

42-inch Toshiba for $850

50-inch Philips for $1,480

Which one would you choose? In this case, Sam knows that customers find it difficult to compute the value of different options. (Who really knows if the Panasonic at $690 is a better deal than the Philips at $1,480?) But Sam also knows that given three choices, most people will take the middle choice (as in landing your plane between the runway lights). So guess which television Sam prices as the middle option? That’s right—the one he wants to sell!

Of course, Sam is not alone in his cleverness. The New York Times ran a story recently about Gregg Rapp, a restaurant consultant, who gets paid to work out the pricing for menus. He knows, for instance, how lamb sold this year as opposed to last year; whether lamb did better paired with squash or with risotto; and whether orders decreased when the price of the main course was hiked from $39 to $41.

One thing Rapp has learned is that high-priced entrées on the menu boost revenue for the restaurant—even if no one buys them. Why? Because even though people generally won’t buy the most expensive dish on the menu, they will order the second most expensive dish. Thus, by creating an expensive dish, a restaurateur can lure customers into ordering the second most expensive choice (which can be cleverly engineered to deliver a higher profit margin).

SO LET’S RUN through the Economist’s sleight of hand in slow motion.

As you recall, the choices were:

1. Internet-only subscription for $59.

2. Print-only subscription for $125.

3. Print-and-Internet subscription for $125.

When I gave these options to 100 students at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, they opted as follows:

1. Internet-only subscription for $59—16 students

2. Print-only subscription for $125—zero students

3. Print-and-Internet subscription for $125—84 students

So far these Sloan MBAs are smart cookies. They all saw the advantage in the print-and-Internet offer over the print-only offer. But were they influenced by the mere presence of the print-only option (which I will henceforth, and for good reason, call the “decoy”). In other words, suppose that I removed the decoy so that the choices would be the ones seen in the figure below:

Would the students respond as before (16 for the Internet only and 84 for the combination)?

Certainly they would react the same way, wouldn’t they? After all, the option I took out was one that no one selected, so it should make no difference. Right?

Au contraire! This time, 68 of the students chose the Internet-only option for $59, up from 16 before. And only 32 chose the combination subscription for $125, down from 84 before.*

What could have possibly changed their minds? Nothing rational, I assure you. It was the mere presence of the decoy that sent 84 of them to the print-and-Internet option (and 16 to the Internet-only option). And the absence of the decoy had them choosing differently, with 32 for print-and-Internet and 68 for Internet-only.

This is not only irrational but predictably irrational as well. Why? I’m glad you asked.

LET ME OFFER you this visual demonstration of relativity.

As you can see, the middle circle can’t seem to stay the same size. When placed among the larger circles, it gets smaller. When placed among the smaller circles, it grows bigger. The middle circle is the same size in both positions, of course, but it appears to change depending on what we place next to it.

This might be a mere curiosity, but for the fact that it mirrors the way the mind is wired: we are always looking at the things around us in relation to others. We can’t help it. This holds true not only for physical things—toasters, bicycles, puppies, restaurant entrées, and spouses—but for experiences such as vacations and educational options, and for ephemeral things as well: emotions, attitudes, and points of view.

We always compare jobs with jobs, vacations with vacations, lovers with lovers, and wines with wines. All this relativity reminds me of a line from the film Crocodile Dundee, when a street hoodlum pulls a switchblade against our hero, Paul Hogan. “You call that a knife?” says Hogan incredulously, withdrawing a bowie blade from the back of his boot. “Now this,” he says with a sly grin, “is a knife.”

RELATIVITY IS (RELATIVELY) easy to understand. But there’s one aspect of relativity that consistently trips us up. It’s this: we not only tend to compare things with one another but also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable—and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily.

That may be a confusing thought, so let me give you an example. Suppose you’re shopping for a house in a new town. Your real estate agent guides you to three houses, all of which interest you. One of them is a contemporary, and two are colonials. All three cost about the same; they are all equally desirable; and the only difference is that one of the colonials (the “decoy”) needs a new roof and the owner has knocked a few thousand dollars off the price to cover the additional expense.

So which one will you choose?

The chances are good that you will not choose the contemporary and you will not choose the colonial that needs the new roof, but you will choose the other colonial. Why? Here’s the rationale (which is actually quite irrational). We like to make decisions based on comparisons. In the case of the three houses, we don’t know much about the contemporary (we don’t have another house to compare it with), so that house goes on the sidelines. But we do know that one of the colonials is better than the other one. That is, the colonial with the good roof is better than the one with the bad roof. Therefore, we will reason that it is better overall and go for the colonial with the good roof, spurning the contemporary and the colonial that needs a new roof.

To better understand how relativity works, consider the following illustration:

In the left side of this illustration we see two options, each of which is better on a different attribute. Option (A) is better on attribute 1—let’s say quality. Option (B) is better on attribute 2—let’s say beauty. Obviously these are two very different options and the choice between them is not simple. Now consider what happens if we add another option, called (–A) (see the right side of the illustration). This option is clearly worse than option (A), but it is also very similar to it, making the comparison between them easy, and suggesting that (A) is not only better than (–A) but also better than (B).

In essence, introducing (–A), the decoy, creates a simple relative comparison with (A), and hence makes (A) look better, not just relative to (–A), but overall as well. As a consequence, the inclusion of (–A) in the set, even if no one ever selects it, makes people more likely to make (A) their final choice.

Does this selection process sound familiar? Remember the pitch put together by the Economist? The marketers there knew that we didn’t know whether we wanted an Internet subscription or a print subscription. But they figured that, of the three options, the print-and-Internet combination would be the offer we would take.

Here’s another example of the decoy effect. Suppose you are planning a honeymoon in Europe. You’ve already decided to go to one of the major romantic cities and have narrowed your choices to Rome and Paris, your two favorites. The travel agent presents you with the vacation packages for each city, which includes airfare, hotel accommodations, sightseeing tours, and a free breakfast every morning. Which would you select?

For most people, the decision between a week in Rome and a week in Paris is not effortless. Rome has the Coliseum; Paris, the Louvre. Both have a romantic ambience, fabulous food, and fashionable shopping. It’s not an easy call. But suppose you were offered a third option: Rome without the free breakfast, called -Rome or the decoy.

If you were to consider these three options (Paris, Rome, -Rome), you would immediately recognize that whereas Rome with the free breakfast is about as appealing as Paris with the free breakfast, the inferior option, which is Rome without the free breakfast, is a step down. The comparison between the clearly inferior option (-Rome) makes Rome with the free breakfast seem even better. In fact, -Rome makes Rome with the free breakfast look so good that you judge it to be even better than the difficult-to-compare option, Paris with the free breakfast.

ONCE YOU SEE the decoy effect in action, you realize that it is the secret agent in more decisions than we could imagine. It even helps us decide whom to date—and, ultimately, whom to marry. Let me describe an experiment that explored just this subject.

As students hurried around MIT one cold weekday, I asked some of them whether they would allow me to take their pictures for a study. In some cases, I got disapproving looks. A few students walked away. But most of them were happy to participate, and before long, the card in my digital camera was filled with images of smiling students. I returned to my office and printed 60 of them—30 of women and 30 of men.

The following week I made an unusual request of 25 of my undergraduates. I asked them to pair the 30 photographs of men and the 30 of women by physical attractiveness (matching the men with other men, and the women with other women). That is, I had them pair the Brad Pitts and the George Clooneys of MIT, as well as the Woody Allens and the Danny DeVitos (sorry, Woody and Danny). Out of these 30 pairs, I selected the six pairs—three female pairs and three male pairs—that my students seemed to agree were most alike.

Now, like Dr. Frankenstein himself, I set about giving these faces my special treatment. Using Photoshop, I mutated the pictures just a bit, creating a slightly but noticeably less attractive version of each of them. I found that just the slightest movement of the nose threw off the symmetry. Using another tool, I enlarged one eye, eliminated some of the hair, and added traces of acne.

No flashes of lightning illuminated my laboratory; nor was there a baying of the hounds on the moor. But this was still a good day for science. By the time I was through, I had the MIT equivalent of George Clooney in his prime (A) and the MIT equivalent of Brad Pitt in his prime (B), and also a George Clooney with a slightly drooping eye and thicker nose (–A, the decoy) and a less symmetrical version of Brad Pitt (-B, another decoy). I followed the same procedure for the less attractive pairs. I had the MIT equivalent of Woody Allen with his usual lopsided grin (A) and Woody Allen with an unnervingly misplaced eye (–A), as well as Danny DeVito (B) and a slightly disfigured version of Danny DeVito (–B).

For each of the 12 photographs, in fact, I now had a regular version as well as an inferior (–) decoy version. (See the illustration for an example of the two conditions used in the study.)

It was now time for the main part of the experiment. I took all the sets of pictures and made my way over to the student union. Approaching one student after another, I asked each to participate. When the students agreed, I handed them a sheet with three pictures (as in the illustration here). Some of them had the regular picture (A), the decoy of that picture (–A), and the other regular picture (B). Others had the regular picture (B), the decoy of that picture (–B), and the other regular picture (A).

For example, a set might include a regular Clooney (A), a decoy Clooney (–A), and a regular Pitt (B); or a regular Pitt (B), a decoy Pitt (–B), and a regular Clooney (A). After selecting a sheet with either male or female pictures, according to their preferences, I asked the students to circle the people they would pick to go on a date with, if they had a choice. All this took quite a while, and when I was done, I had distributed 600 sheets.

What was my motive in all this? Simply to determine if the existence of the distorted picture (–A or –B) would push my participants to choose the similar but undistorted picture. In other words, would a slightly less attractive George Clooney (–A) push the participants to choose the perfect George Clooney over the perfect Brad Pitt?

There were no pictures of Brad Pitt or George Clooney in my experiment, of course. Pictures (A) and (B) showed ordinary students. But do you remember how the existence of a colonial-style house needing a new roof might push you to choose a perfect colonial over a contemporary house—simply because the decoy colonial would give you something against which to compare the regular colonial? And in the Economist’s ad, didn’t the print-only option for $125 push people to take the print-and-Internet option for $125? Similarly, would the existence of a less perfect person (–A or –B) push people to choose the perfect one (A or B), simply because the decoy option served as a point of comparison?

Note: For this illustration, I used computerized faces, not those of the MIT students. And of course, the letters did not appear on the original sheets.

It did. Whenever I handed out a sheet that had a regular picture, its inferior version, and another regular picture, the participants said they would prefer to date the “regular” person—the one who was similar, but clearly superior, to the distorted version—over the other, undistorted person on the sheet. This was not just a close call—it happened 75 percent of the time.

To explain the decoy effect further, let me tell you something about bread-making machines. When Williams-Sonoma first introduced a home “bread bakery” machine (for $275), most consumers were not interested. What was a home bread-making machine, anyway? Was it good or bad? Did one really need home-baked bread? Why not just buy a fancy coffeemaker sitting nearby instead? Flustered by poor sales, the manufacturer of the bread machine brought in a marketing research firm, which suggested a fix: introduce an additional model of the bread maker, one that was not only larger but priced about 50 percent higher than the initial machine.

Now sales began to rise (along with many loaves of bread), though it was not the large bread maker that was being sold. Why? Simply because consumers now had two models of bread makers to choose from. Since one was clearly larger and much more expensive than the other, people didn’t have to make their decision in a vacuum. They could say: “Well, I don’t know much about bread makers, but I do know that if I were to buy one, I’d rather have the smaller one for less money.” And that’s when bread makers began to fly off the shelves.

OK for bread makers. But let’s take a look at the decoy effect in a completely different situation. What if you are single, and hope to appeal to as many attractive potential dating partners as possible at an upcoming singles event? My advice would be to bring a friend who has your basic physical characteristics (similar coloring, body type, facial features), but is slightly less attractive (–you).

Why? Because the folks you want to attract will have a hard time evaluating you with no comparables around. However, if you are compared with a “–you,” the decoy friend will do a lot to make you look better, not just in comparison with the decoy but also in general, and in comparison with all the other people around. It may sound irrational (and I can’t guarantee this), but the chances are good that you will get some extra attention. Of course, don’t just stop at looks. If great conversation will win the day, be sure to pick a friend for the singles event who can’t match your smooth delivery and rapier wit. By comparison, you’ll sound great.

Now that you know this secret, be careful: when a similar but better-looking friend of the same sex asks you to accompany him or her for a night out, you might wonder whether you have been invited along for your company or merely as a decoy.

RELATIVITY HELPS US make decisions in life. But it can also make us downright miserable. Why? Because jealousy and envy spring from comparing our lot in life with that of others.

It was for good reason, after all, that the Ten Commandments admonished, “Neither shall you desire your neighbor’s house nor field, or male or female slave, or donkey or anything that belongs to your neighbor.” This might just be the toughest commandment to follow, considering that by our very nature we are wired to compare.

Modern life makes this weakness even more pronounced. A few years ago, for instance, I met with one of the top executives of one of the big investment companies. Over the course of our conversation he mentioned that one of his employees had recently come to him to complain about his salary.

“How long have you been with the firm?” the executive asked the young man.

“Three years. I came straight from college,” was the answer.

“And when you joined us, how much did you expect to be making in three years?”

“I was hoping to be making about a hundred thousand.”

The executive eyed him curiously.

“And now you are making almost three hundred thousand, so how can you possibly complain?” he asked.

“Well,” the young man stammered, “it’s just that a couple of the guys at the desks next to me, they’re not any better than I am, and they are making three hundred ten.”

The executive shook his head.

An ironic aspect of this story is that in 1993, federal securities regulators forced companies, for the first time, to reveal details about the pay and perks of their top executives. The idea was that once pay was in the open, boards would be reluctant to give executives outrageous salaries and benefits. This, it was hoped, would stop the rise in executive compensation, which neither regulation, legislation, nor shareholder pressure had been able to stop. And indeed, it needed to stop: in 1976 the average CEO was paid 36 times as much as the average worker. By 1993, the average CEO was paid 131 times as much.

But guess what happened. Once salaries became public information, the media regularly ran special stories ranking CEOs by pay. Rather than suppressing the executive perks, the publicity had CEOs in America comparing their pay with that of everyone else. In response, executives’ salaries skyrocketed. The trend was further “helped” by compensation consulting firms (scathingly dubbed “Ratchet, Ratchet, and Bingo” by the investor Warren Buffett) that advised their CEO clients to demand outrageous raises. The result? Now the average CEO makes about 369 times as much as the average worker—about three times the salary before executive compensation went public.

Keeping that in mind, I had a few questions for the executive I met with.

“What would happen,” I ventured, “if the information in your salary database became known throughout the company?”

The executive looked at me with alarm. “We could get over a lot of things here—insider trading, financial scandals, and the like—but if everyone knew everyone else’s salary, it would be a true catastrophe. All but the highest-paid individual would feel underpaid—and I wouldn’t be surprised if they went out and looked for another job.”

Isn’t this odd? It has been shown repeatedly that the link between amount of salary and happiness is not as strong as one would expect it to be (in fact, it is rather weak). Studies even find that countries with the “happiest” people are not among those with the highest personal income. Yet we keep pushing toward a higher salary. Much of that can be blamed on sheer envy. As H. L. Mencken, the twentieth-century journalist, satirist, social critic, cynic, and freethinker noted, a man’s satisfaction with his salary depends on (are you ready for this?) whether he makes more than his wife’s sister’s husband. Why the wife’s sister’s husband? Because (and I have a feeling that Mencken’s wife kept him fully informed of her sister’s husband’s salary) this is a comparison that is salient and readily available.*

All this extravagance in CEOs’ pay has had a damaging effect on society. Instead of causing shame, every new outrage in compensation encourages other CEOs to demand even more. “In the Web World,” according to a headline in the New York Times, the “Rich Now Envy the Superrich.”

In another news story, a physician explained that he had graduated from Harvard with the dream of someday receiving a Nobel Prize for cancer research. This was his goal. This was his dream. But a few years later, he realized that several of his colleagues were making more as medical investment advisers at Wall Street firms than he was making in medicine. He had previously been happy with his income, but hearing of his friends’ yachts and vacation homes, he suddenly felt very poor. So he took another route with his career—the route of Wall Street.

By the time he arrived at his twentieth class reunion, he was making 10 times what most of his peers were making in medicine. You can almost see him, standing in the middle of the room at the reunion, drink in hand—a large circle of influence with smaller circles gathering around him. He had not won the Nobel Prize, but he had relinquished his dreams for a Wall Street salary, for a chance to stop feeling “poor.” Is it any wonder that family practice physicians, who make an average of $160,000 a year, are in short supply?*

CAN WE DO anything about this problem of relativity?

The good news is that we can sometimes control the “circles” around us, moving toward smaller circles that boost our relative happiness. If we are at our class reunion, and there’s a “big circle” in the middle of the room with a drink in his hand, boasting of his big salary, we can consciously take several steps away and talk with someone else. If we are thinking of buying a new house, we can be selective about the open houses we go to, skipping the houses that are above our means. If we are thinking about buying a new car, we can focus on the models that we can afford, and so on.

We can also change our focus from narrow to broad. Let me explain with an example from a study conducted by two brilliant researchers, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. Suppose you have two errands to run today. The first is to buy a new pen, and the second is to buy a suit for work. At an office supply store, you find a nice pen for $25. You are set to buy it, when you remember that the same pen is on sale for $18 at another store 15 minutes away. What would you do? Do you decide to take the 15-minute trip to save the $7? Most people faced with this dilemma say that they would take the trip to save the $7.

Now you are on your second task: you’re shopping for your suit. You find a luxurious gray pinstripe suit for $455 and decide to buy it, but then another customer whispers in your ear that the exact same suit is on sale for only $448 at another store, just 15 minutes away. Do you make this second 15-minute trip? In this case, most people say that they would not.

But what is going on here? Is 15 minutes of your time worth $7, or isn’t it? In reality, of course, $7 is $7—no matter how you count it. The only question you should ask yourself in these cases is whether the trip across town, and the 15 extra minutes it would take, is worth the extra $7 you would save. Whether the amount from which this $7 will be saved is $10 or $10,000 should be irrelevant.

This is the problem of relativity—we look at our decisions in a relative way and compare them locally to the available alternative. We compare the relative advantage of the cheap pen with the expensive one, and this contrast makes it obvious to us that we should spend the extra time to save the $7. At the same time, the relative advantage of the cheaper suit is very small, so we spend the extra $7.

This is also why it is so easy for a person to add $200 to a $5,000 catering bill for a soup entrée, when the same person will clip coupons to save 25 cents on a one-dollar can of condensed soup. Similarly, we find it easy to spend $3,000 to upgrade to leather seats when we buy a new $25,000 car, but difficult to spend the same amount on a new leather sofa (even though we know we will spend more time at home on the sofa than in the car). Yet if we just thought about this in a broader perspective, we could better assess what we could do with the $3,000 that we are considering spending on upgrading the car seats. Would we perhaps be better off spending it on books, clothes, or a vacation? Thinking broadly like this is not easy, because making relative judgments is the natural way we think. Can you get a handle on it? I know someone who can.

He is James Hong, cofounder of the Hotornot.com rating and dating site. (James, his business partner Jim Young, Leonard Lee, George Loewenstein, and I recently worked on a research project examining how one’s own “attractiveness” affects one’s view of the “attractiveness” of others.)

For sure, James has made a lot of money, and he sees even more money all around him. One of his good friends, in fact, is a founder of PayPal and is worth tens of millions. But Hong knows how to make the circles of comparison in his life smaller, not larger. In his case, he started by selling his Porsche Boxster and buying a Toyota Prius in its place.

“I don’t want to live the life of a Boxster,” he told the New York Times, “because when you get a Boxster you wish you had a 911, and you know what people who have 911s wish they had? They wish they had a Ferrari.”

That’s a lesson we can all learn: the more we have, the more we want. And the only cure is to break the cycle of relativity.

Reflections on Dating and Relativity

In Chapter 1, on relativity, I offered some dating advice. I proposed that if you want to go bar-hopping, you should consider taking along someone who looks similar to you but who is slightly less attractive than you are. Because of the relative nature of evaluations, others would perceive you not only as cuter than your decoy, but also as better-looking than other people in the bar. By the same logic, I also pointed out that the flip side of this coin is that if someone invites you to be his or her wingman (or wingwoman), you can easily figure out what your friend really thinks of you. As it turns out, I forgot to include one important warning that came courtesy of the daughter of a colleague of mine from MIT.

“Susan” was an undergraduate at Cornell who wrote to me, saying she was delighted with my trick and that it had worked wonderfully for her. Once she found the ideal decoy, her social life improved. But a few weeks later she wrote again, telling me that she’d been at a party where she’d had a few drinks. For some odd reason, she decided to tell her friend why she invited her to accompany her everywhere. The friend was understandably upset, and the story did not end well.

The moral of this story? Never, ever tell your friend why you’re asking him or her to come with you. Your friend might have suspicions, but for the love of God, don’t eliminate all doubt.

Reflections on Traveling and Relativity

When Predictably Irrational came out, I went on a book tour that lasted six straight weeks. I traveled from airport to airport, city to city, radio station to radio station, talking to reporters and readers for what seemed like days on end, without engaging in any type of personal discussion. Every conversation was short, “all business,” and focused on my research. There was no time to enjoy a cup of coffee or a beer with any of the wonderful people I encountered.

Toward the end of the tour I found myself in Barcelona. There I met Jon, an American tourist who, like me, did not speak any Spanish. We felt an immediate camaraderie. I imagine this kind of bonding happens often with travelers from the same country who are far from home and find themselves sharing observations about how they differ from the locals around them. Jon and I ended up having a wonderful dinner and a deeply personal discussion. He told me things that he seemed not to have shared before, and I did the same. There was an unusual closeness between us, as if we were long-lost brothers. After staying up very late talking, we both needed to sleep. We would not have a chance to meet again before parting ways the following morning, so we exchanged e-mail addresses. This was a mistake.

About six months later, Jon and I met again for lunch in New York. This time, it was hard for me to figure out why I’d felt such a connection with him, and no doubt he felt the same. We had a perfectly amicable and interesting lunch, but it lacked the intensity of our first meeting, and I was left wondering why.

In retrospect, I think it was because I’d fallen victim to the effects of relativity. When Jon and I first met, everyone around us was Spanish, and as cultural outsiders we were each other’s best alternative for companionship. But once we returned home to our beloved American families and friends, the basis for comparison switched back to “normal” mode. Given this situation, it was hard to understand why Jon or I would want to spend another evening in each other’s company rather than with those we love.

My advice? Understand that relativity is everywhere, and that we view everything through its lens—rose-colored or otherwise. When you meet someone in a different country or city and it seems that you have a magical connection, realize that the enchantment might be limited to the surrounding circumstances. This realization might prevent you from subsequent disenchantment.

CHAPTER 2

The Fallacy of Supply and Demand

Why the Price of Pearls—and Everything Else—

Is Up in the Air

At the onset of World War II, an Italian diamond dealer, James Assael, fled Europe for Cuba. There, he found a new livelihood: the American army needed waterproof watches, and Assael, through his contacts in Switzerland, was able to fill the demand.

When the war ended, Assael’s deal with the U.S. government dried up, and he was left with thousands of Swiss watches. The Japanese needed watches, of course. But they didn’t have any money. They did have pearls, though—many thousands of them. Before long, Assael had taught his son how to barter Swiss watches for Japanese pearls. The business blossomed, and shortly thereafter, the son, Salvador Assael, became known as the “pearl king.”

The pearl king had moored his yacht at Saint-Tropez one day in 1973, when a dashing young Frenchman, Jean-Claude Brouillet, came aboard from an adjacent yacht. Brouillet had just sold his air-freight business and with the proceeds had purchased an atoll in French Polynesia—a blue-lagooned paradise for himself and his young Tahitian wife. Brouillet explained that its turquoise waters abounded with black-lipped oysters, Pinctada margaritifera. And from the black lips of those oysters came something of note: black pearls.

At the time there was no market for Tahitian black pearls, and little demand. But Brouillet persuaded Assael to go into business with him. Together they would harvest black pearls and sell them to the world. At first, Assael’s marketing efforts failed. The pearls were gunmetal gray, about the size of musket balls, and he returned to Polynesia without having made a single sale. Assael could have dropped the black pearls altogether or sold them at a low price to a discount store. He could have tried to push them to consumers by bundling them together with a few white pearls. But instead Assael waited a year, until the operation had produced some better specimens, and then brought them to an old friend, Harry Winston, the legendary gemstone dealer. Winston agreed to put them in the window of his store on Fifth Avenue, with an outrageously high price tag attached. Assael, meanwhile, commissioned a full-page advertisement that ran in the glossiest of magazines. There, a string of Tahitian black pearls glowed, set among a spray of diamonds, rubies, and emeralds.

The pearls, which had shortly before been the private business of a cluster of black-lipped oysters, hanging on a rope in the Polynesian sea, were soon parading through Manhattan on the arched necks of the city’s most prosperous divas. Assael had taken something of dubious worth and made it fabulously fine. Or, as Mark Twain once noted about Tom Sawyer, “Tom had discovered a great law of human action, namely, that in order to make a man covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.”

HOW DID THE pearl king do it? How did he persuade the cream of society to become passionate about Tahitian black pearls—and pay him royally for them? In order to answer this question, I need to explain something about baby geese.

A few decades ago, the naturalist Konrad Lorenz discovered that goslings, upon breaking out of their eggs, become attached to the first moving object they encounter (which is generally their mother). Lorenz knew this because in one experiment he became the first thing they saw, and they followed him loyally from then on through adolescence. With that, Lorenz demonstrated not only that goslings make initial decisions based on what’s available in their environment, but that they stick with a decision once it has been made. Lorenz called this natural phenomenon imprinting.

Is the human brain, then, wired like that of a gosling? Do our first impressions and decisions become imprinted? And if so, how does this imprinting play out in our lives? When we encounter a new product, for instance, do we accept the first price that comes before our eyes? And more importantly, does that price (which in academic lingo we call an anchor) have a long-term effect on our willingness to pay for the product from then on?

It seems that what’s good for the goose is good for humans as well. And this includes anchoring. From the beginning, for instance, Assael “anchored” his pearls to the finest gems in the world—and the prices followed forever after. Similarly, once we buy a new product at a particular price, we become anchored to that price. But how exactly does this work? Why do we accept anchors?

Consider this: if I asked you for the last two digits of your social security number (mine are 79), then asked you whether you would pay this number in dollars (for me this would be $79) for a particular bottle of Côtes du Rhône 1998, would the mere suggestion of that number influence how much you would be willing to spend on wine? Sounds preposterous, doesn’t it? Well, wait until you see what happened to a group of MBA students at MIT a few years ago.

“NOW HERE WE have a nice Côtes du Rhône Jaboulet Parallel,” said Drazen Prelec, a professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, as he lifted a bottle admiringly. “It’s a 1998.”

At the time, sitting before him were the 55 students from his marketing research class. On this day, Drazen, George Loewenstein (a professor at Carnegie Mellon University), and I would have an unusual request for this group of future marketing pros. We would ask them to jot down the last two digits of their social security numbers and tell us whether they would pay this amount for a number of products, including the bottle of wine. Then, we would ask them to actually bid on these items in an auction.

What were we trying to prove? The existence of what we called arbitrary coherence. The basic idea of arbitrary coherence is this: although initial prices (such as the price of Assael’s pearls) are “arbitrary,” once those prices are established in our minds they will shape not only present prices but also future prices (this makes them “coherent”). So, would thinking about one’s social security number be enough to create an anchor? And would that initial anchor have a long-term influence? That’s what we wanted to see.

“For those of you who don’t know much about wines,” Drazen continued, “this bottle received eighty-six points from Wine Spectator. It has the flavor of red berry, mocha, and black chocolate; it’s a medium-bodied, medium-intensity, nicely balanced red, and it makes for delightful drinking.”

Drazen held up another bottle. This was a Hermitage Jaboulet La Chapelle, 1996, with a 92-point rating from the Wine Advocate magazine. “The finest La Chapelle since 1990,” Drazen intoned, while the students looked up curiously. “Only 8,100 cases made . . .”

In turn, Drazen held up four other items: a cordless trackball (TrackMan Marble FX by Logitech); a cordless keyboard and mouse (iTouch by Logitech); a design book (The Perfect Package: How to Add Value through Graphic Design); and a one-pound box of Belgian chocolates by Neuhaus.

Drazen passed out forms that listed all the items. “Now I want you to write the last two digits of your social security number at the top of the page,” he instructed. “And then write them again next to each of the items in the form of a price. In other words, if the last two digits are twenty-three, write twenty-three dollars.”

“Now when you’re finished with that,” he added, “I want you to indicate on your sheets—with a simple yes or no—whether you would pay that amount for each of the products.”

When the students had finished answering yes or no to each item, Drazen asked them to write down the maximum amount they were willing to pay for each of the products (their bids). Once they had written down their bids, the students passed the sheets up to me and I entered their responses into my laptop and announced the winners. One by one the student who had made the highest bid for each of the products would step up to the front of the class, pay for the product,* and take it with them.

The students enjoyed this class exercise, but when I asked them if they felt that writing down the last two digits of their social security numbers had influenced their final bids, they quickly dismissed my suggestion. No way!

When I got back to my office, I analyzed the data. Did the digits from the social security numbers serve as anchors? Remarkably, they did: the students with the highest-ending social security digits (from 80 to 99) bid highest, while those with the lowest-ending numbers (1 to 20) bid lowest. The top 20 percent, for instance, bid an average of $56 for the cordless keyboard; the bottom 20 percent bid an average of $16. In the end, we could see that students with social security numbers ending in the upper 20 percent placed bids that were 216 to 346 percent higher than those of the students with social security numbers ending in the lowest 20 percent (see table on the facing page).

Now if the last two digits of your social security number are a high number I know what you must be thinking: “I’ve been paying too much for everything my entire life!” This is not the case, however. Social security numbers were the anchor in this experiment only because we requested them. We could have just as well asked for the current temperature or the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP). Any question, in fact, would have created the anchor. Does that seem rational? Of course not. But that’s the way we are—goslings, after all.*

The data had one more interesting aspect. Although the willingness to pay for these items was arbitrary, there was also a logical, coherent aspect to it. When we looked at the bids for the two pairs of related items (the two wines and the two computer components), their relative prices seemed incredibly logical. Everyone was willing to pay more for the keyboard than for the trackball—and also pay more for the 1996 Hermitage than for the 1998 Côtes du Rhône. The significance of this is that once the participants were willing to pay a certain price for one product, their willingness to pay for other items in the same product category was judged relative to that first price (the anchor).

This, then, is what we call arbitrary coherence. Initial prices are largely “arbitrary” and can be influenced by responses to random questions; but once those prices are established in our minds, they shape not only what we are willing to pay for an item, but also how much we are willing to pay for related products (this makes them coherent).

Now I need to add one important clarification to the story I’ve just told. In life we are bombarded by prices. We see the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) for cars, lawn mowers, and coffeemakers. We get the real estate agent’s spiel on local housing prices. But price tags by themselves are not necessarily anchors. They become anchors when we contemplate buying a product or service at that particular price. That’s when the imprint is set. From then on, we are willing to accept a range of prices—but as with the pull of a bungee cord, we always refer back to the original anchor. Thus the first anchor influences not only the immediate buying decision but many others that follow.

We might see a 57-inch LCD high-definition television on sale for $3,000, for instance. The price tag is not the anchor. But if we decide to buy it (or seriously contemplate buying it) at that price, then the decision becomes our anchor henceforth in terms of LCD television sets. That’s our peg in the ground, and from then on—whether we shop for another set or merely have a conversation at a backyard cookout—all other high-definition televisions are judged relative to that price.

Anchoring influences all kinds of purchases. Uri Simonsohn (a professor at the University of Pennsylvania) and George Loewenstein, for example, found that people who move to a new city generally remain anchored to the prices they paid for housing in their former city. In their study they found that people who move from inexpensive markets (say, Lubbock, Texas) to moderately priced cities (say, Pittsburgh) don’t increase their spending to fit the new market.* Rather, these people spend an amount similar to what they were used to in the previous market, even if this means having to squeeze themselves and their families into smaller or less comfortable homes. Likewise, transplants from more expensive cities sink the same dollars into their new housing situation as they did in the past. People who move from Los Angeles to Pittsburgh, in other words, don’t generally downsize their spending much once they hit Pennsylvania: they spend an amount similar to what they used to spend in Los Angeles.

It seems that we get used to the particularities of our housing markets and don’t readily change. The only way out of this box, in fact, is to rent a home in the new location for a year or so. That way, we adjust to the new environment—and, after a while, we are able to make a purchase that aligns with the local market.

SO WE ANCHOR ourselves to initial prices. But do we hop from one anchor price to another (flip-flopping, if you will), continually changing our willingness to pay? Or does the first anchor we encounter become our anchor for a long time and for many decisions? To answer this question, we decided to conduct another experiment—one in which we attempted to lure our participants from old anchors to new ones.

For this experiment we enlisted some undergraduate students, some graduate students, and some investment bankers who had come to the campus to recruit new employees for their firms. Once the experiment started we presented our participants with three different sounds, and following each, asked them if they would be willing to get paid a particular amount of money (which served as the price anchor) for hearing those sounds again. One sound was a 30-second high-pitched 3,000-hertz sound, somewhat like someone screaming in a high-pitched voice. Another was a 30-second full-spectrum noise (also called white noise), which is similar to the noise a television set makes when there is no reception. The third was a 30-second oscillation between high-pitched and low-pitched sounds. (I am not sure if the bankers understood exactly what they were about to experience, but maybe even our annoying sounds were less annoying than talking about investment banking.)

We used sounds because there is no existing market for annoying sounds (so the participants couldn’t use a market price as a way to think about the value of these sounds). We also used annoying sounds, specifically, because no one likes such sounds (if we had used classical music, some would have liked it better than others). As for the sounds themselves, I selected them after creating hundreds of sounds, choosing these three because they were, in my opinion, equally annoying.

We placed our participants in front of computer screens at the lab, and had them clamp headphones over their ears.

As the room quieted down, the first group saw this message appear in front of them: “In a few moments we are going to play a new unpleasant tone over your headset. We are interested in how annoying you find it. Immediately after you hear the tone, we will ask you whether, hypothetically, you would be willing to repeat the same experience in exchange for a payment of 10 cents.” The second group got the same message, only with an offer of 90 cents rather than 10 cents.

Would the anchor prices make a difference? To find out, we turned on the sound—in this case the irritating 30-second, 3,000-hertz squeal. Some of our participants grimaced. Others rolled their eyes.

When the screeching ended, each participant was presented with the anchoring question, phrased as a hypothetical choice: Would the participant be willing, hypothetically, to repeat the experience for a cash payment (which was 10 cents for the first group and 90 cents for the second group)? After answering this anchoring question, the participants were asked to indicate on the computer screen the lowest price they would demand to listen to the sound again. This decision was real, by the way, as it would determine whether they would hear the sound again—and get paid for doing so.*

Soon after the participants entered their prices, they learned the outcome. Participants whose price was sufficiently low “won” the sound, had the (unpleasant) opportunity to hear it again, and got paid for doing so. The participants whose price was too high did not listen to the sound and were not paid for this part of the experiment.

What was the point of all this? We wanted to find out whether the first prices that we suggested (10 cents and 90 cents) had served as an anchor. And indeed they had. Those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 10 cents needed much less money to be willing to listen to this sound again (33 cents on average) relative to those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 90 cents—this second group demanded more than twice the compensation (73 cents on average) for the same annoying experience. Do you see the difference that the suggested price had?

BUT THIS WAS only the start of our exploration. We also wanted to know how influential the anchor would be in future decisions. Suppose we gave the participants an opportunity to drop this anchor and run for another? Would they do it? To put it in terms of goslings, would they swim across the pond after their original imprint and then, midway, swing their allegiance to a new mother goose? In terms of goslings, I think you know that they would stick with the original mom. But what about humans? The next two phases of the experiment would enable us to answer these questions.

In the second phase of the experiment, we took participants from the previous 10-cents and 90-cents groups and treated them to 30 seconds of a white, wooshing noise. “Hypothetically, would you listen to this sound again for 50 cents?” we asked them at the end. The respondents pressed a button on their computers to indicate yes or no.

“OK, how much would you need to be paid for this?” we asked. Our participants typed in their lowest price; the computer did its thing; and, depending on their bids, some participants listened to the sound again and got paid and some did not. When we compared the prices, the 10-cents group offered much lower bids than the 90-cents group. This means that although both groups had been equally exposed to the suggested 50 cents, as their focal anchoring response (to “Hypothetically, would you listen to this sound again for 50 cents?”), the first anchor in this annoying sound category (which was 10 cents for some and 90 cents for others) predominated.

Why? Perhaps the participants in the 10-cents group said something like the following to themselves: “Well, I listened previously to that annoying sound for a low amount. This sound is not much different. So if I said a low amount for the previous one, I guess I could bear this sound for about the same price.” Those who were in the 90-cents group used the same type of logic, but because their starting point was different, so was their ending point. These individuals told themselves, “Well, I listened previously to that annoying sound for a high amount. This sound is not much different. So since I said a high amount for the previous one, I guess I could bear this sound for about the same price.” Indeed, the effect of the first anchor held—indicating that anchors have an enduring effect for present prices as well as for future prices.

There was one more step to this experiment. This time we had our participants listen to the oscillating sound that rose and fell in pitch for 30 seconds. We asked our 10-cents group, “Hypothetically, would you listen to this sound again for 90 cents?” Then we asked our 90-cents group, “Would you listen to this sound again for 10 cents?” Having flipped our anchors, we would now see which one, the local anchor or the first anchor, exerted the greatest influence.

Once again, the participants typed in yes or no. Then we asked them for real bids: “How much would it take for you to listen to this again?” At this point, they had a history with three anchors: the first one they encountered in the experiment (either 10 cents or 90 cents), the second one (50 cents), and the most recent one (either 90 cents or 10 cents). Which one of these would have the largest influence on the price they demanded to listen to the sound?

Again, it was as if our participants’ minds told them, “If I listened to the first sound for x cents, and listened to the second sound for x cents as well, then I can surely do this one for x cents, too!” And that’s what they did. Those who had first encountered the 10-cent anchor accepted low prices, even after 90 cents was suggested as the anchor. On the other hand, those who had first encountered the 90-cent anchor kept on demanding much higher prices, regardless of the anchors that followed.

What did we show? That our first decisions resonate over a long sequence of decisions. First impressions are important, whether they involve remembering that our first DVD player cost much more than such players cost today (and realizing that, in comparison, the current prices are a steal) or remembering that gas was once a dollar a gallon, which makes every trip to the gas station a painful experience. In all these cases the random, and not so random, anchors that we encountered along the way and were swayed by remain with us long after the initial decision itself.

NOW THAT WE know we behave like goslings, it is important to understand the process by which our first decisions translate into long-term habits. To illustrate this process, consider this example. You’re walking past a restaurant, and you see two people standing in line, waiting to get in. “This must be a good restaurant,” you think to yourself. “People are standing in line.” So you stand behind these people. Another person walks by. He sees three people standing in line and thinks, “This must be a fantastic restaurant,” and joins the line. Others join. We call this type of behavior herding. It happens when we assume that something is good (or bad) on the basis of other people’s previous behavior, and our own actions follow suit.

But there’s also another kind of herding, one that we call self-herding. This happens when we believe something is good (or bad) on the basis of our own previous behavior. Essentially, once we become the first person in line at the restaurant, we begin to line up behind ourself in subsequent experiences. Does that make sense? Let me explain.

Recall your first introduction to Starbucks, perhaps several years ago. (I assume that nearly everyone has had this experience, since Starbucks sits on every corner in America.) You are sleepy and in desperate need of a liquid energy boost as you embark on an errand one afternoon. You glance through the windows at Starbucks and walk in. The prices of the coffee are a shock—you’ve been blissfully drinking the brew at Dunkin’ Donuts for years. But since you have walked in and are now curious about what coffee at this price might taste like, you surprise yourself: you buy a small coffee, enjoy its taste and its effect on you, and walk out.