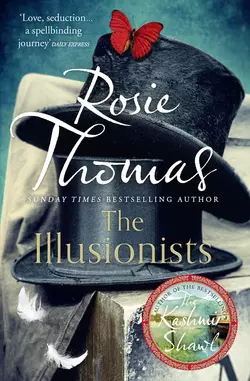

The Illusionists

Rosie Thomas

From the bestselling author of the phenomenally successful The Kashmir ShawlLondon 1885As a turbulent and change-filled century draws to a close, there has never been a better time to alter your fortune. But for a beautiful young woman of limited means, Eliza’s choices appear to lie between the stifling domesticity of marriage or a downwards spiral to the streets – no matter how determined she is to forge her own path.One night at a run-down theatre, she meets the charismatic Devil Wix – showman, master of illusion, fickle friend. Drawn into his circle, Eliza becomes the catalyst of change for his colleagues – a dwarf, an eccentric engineer, and an artist – as well as Devil himself. And as Eliza embarks on a dangerous adventure, she must decide which path to choose, and how far she should go when she holds all their lives in her hands.

THE ILLUSIONISTS

Rosie Thomas

Copyright (#ud91d1780-b217-5f08-bc03-eeac058fdd2d)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Rosie Thomas 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Rosie Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007512041

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780007512034

Version: 2015-02-23

Dedication (#ud91d1780-b217-5f08-bc03-eeac058fdd2d)

For my family

Contents

Cover (#uc76b7ea5-f8fa-5704-a573-935ada421020)

Title Page (#u508d1620-d464-57d2-922d-1716b8b93083)

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Two

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Part Three

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Author Q&A

Reading group guide

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Also by Rosie Thomas

About the Publisher

PART ONE (#ud91d1780-b217-5f08-bc03-eeac058fdd2d)

ONE (#ud91d1780-b217-5f08-bc03-eeac058fdd2d)

London 1885

Hector Crumhall, known to his legions of enemies and even his few friends as Devil Wix, sauntered up the alley as if he owned every cobblestone and sooty brick. He stepped over the runnel of filth that ran down the middle, touching the brim of his bowler in a mocking salute to Annie Fowler who was seated in the doorway of her house. Two of her girls, torn robes barely covering their shoulders, lounged at an upstairs window with a tin cup on the sill between them.

‘Good afternoon to you, ladies,’ Devil called.

Annie took her pipe out of her mouth, cleared her throat and spat.

A pair of urchins emerged from the shelter of some crates that had once held fish from the market. They came at Devil with their hands out, driven by desperation rather than any hope that he might drop them a coin.

‘Mister?’ the bigger one wheedled. They were poised to run in case he lashed out.

Devil stopped. Except for the two brats the only onlookers were Annie and the listless drabs, but he was unable to resist any audience for a trick. He slid two fingers into a waistcoat pocket, displacing the watch chain with his thumb. There was no timepiece on the end of the chain, but who was to know such a detail? He slipped out a bright penny and flicked it into the air. The boys’ heads jerked as they followed its ascent and descent, and they sighed when Devil’s fist closed on it. He repeated the flick and catch a second time, and then a third, and the fourth time the boys’ heads hardly moved. But Devil’s fist didn’t close again. Instead he spread his palm and gazed into the air as if searching for the penny. The boys gaped and spun on their heels, straining to hear the coin’s clink, hunched in their anxiety to pounce on it. No clatter or roll sounded. Thin air had seemingly eaten the penny.

Devil frowned, raising his arm to cuff the nearest boy for losing his coin. The child scuttled off and Devil caught the ear of his slower companion. The boy immediately twisted and yelled at the top of his voice, ‘Lemme go, I done nothing.’

Devil groped behind the other ear and produced a red apple. Mouth open, the boy squirmed free and snatched at the fruit but Devil held it just out of his reach. Shaking his head in reproach he bit luxuriously into it. The boy groaned and the girls jeered from their window. Devil continued his interrupted stroll up the alley, chewing with relish and smiling at the thin shaft of sunlight that slid between the overhanging eaves.

The street into which he emerged was hardly wider than its tributary alley but there were more people here. Men leaned against the house walls, dirty-faced children played with pebbles and sticks in the gutters, a couple of shawled women murmured at the steps. The cats’ meat man, a familiar figure, trundled his wheeled cart round the corner. Announcing itself with a pungent reek, his merchandise was condemned meat and chunks of ripe offal. It was intended for animals, but there were plenty of housewives in this neighbourhood who were glad to buy a little piece to boil up with half an onion and a handful of potato peelings to make a dinner for a hungry family.

Tossing away the apple core Devil stuck his hands into his pockets and passed on by. The intermediate street led in turn to a much wider thoroughfare. Here there were tall black buildings and glass shop frontages with names picked out in gilt lettering on their fascias. Painted enamel signs advertised tobacco and patent medicines, slate boards chalked with the prices of the day’s dinners hung outside working men’s eating-houses. It was noisy here, with street vendors shouting their wares over the hammering from building sites and the clip of horses’ hooves as loaded drays and hansom cabs and a crowded omnibus bound for Oxford Street rolled by. Pedestrians brushed past Devil, some of them glancing at his handsome face.

Let them stare, he always thought. What’s worth looking at must be worth seeing.

On the opposite corner of the street stood the Old Cinque Ports, a large public house. He hadn’t decided where he was heading today, but wherever it turned out to be would be fine because he felt lucky, and his instincts rarely let him down. In any case there was no hurry. A quick visit to the Ports would be a good way to get business started.

The heavy doors had twin panels of etched glass. Devil leaned on a brass handle and pushed open the door. It was the middle of an autumn afternoon but the lamps in the ornate saloon were blazing, and the bevels of the glass split the bright beams into little rainbows. As it always did, the interior of the pub reminded him of a place of worship. The cavernous ceiling arched overhead, polished brass and carved mahogany fittings glowed, and the altar – or in this case the long, sinuous curve of the bar – was the focus of all attention. The main differences were that it was warm in here and the place attracted a more interesting class of sinner, including numbers of women. One of them swayed towards Devil now. She had broad hips swathed in red sateen and a deep-cut bodice that revealed most of a pair of white breasts so heavily powdered that a pale fog rose off them as she moved. He didn’t think he had encountered her before, but she linked her bare arm in his as if they were old friends and guided him with a nudge of the hips towards a pair of stools. Devil had no objection. He liked sitting up here against the bar where he could admire the rows of bright bottles and their reflections in the painted glass, or flick a glance sideways at the drinkers’ profiles ranged on either side to assess them as potential threat or target. The stools were carved to fit a man’s rear, and when you parked yourself you felt that there was no finer place on earth to be than beneath the roof of this brewer’s temple, and no more promising day in your life than this very one.

‘I’ll have a gin, duck,’ the woman sighed in his ear. She had hopped up on to the stool next to his. Devil rapped on the marble bar top with a florin, and the barman came with a brief nod of greeting. The Old Cinque Ports was a busy place and Devil didn’t come here quite often enough for the man to try to use his name, which was how he preferred it. He ordered a glass for the woman and a pint of Bass for himself, and when the drinks came he put hers into her hand.

She had bad teeth which she tried to hide by keeping her lips drawn taut over her smile. Her hair lay thin and brittle over her grey scalp. She was several cuts above Annie Fowler’s wretched girls but most likely she lived in one corner of a room somewhere in the rookery from which he had just emerged, and probably struggled to find the shillings even for that. No doubt she had children to feed.

The woman lifted the glass and swallowed an eager gulp of gin. Her eyes met his, acknowledging that it was a hard life.

Devil leaned forward so their faces almost touched, like a kiss about to happen.

‘Now, get off with you and leave me alone.’

Her smile died, but she made no attempt to change his mind. She slid wearily from the stool and moved into the throng in search of another mark.

Devil sat back and made a survey of his companions. Several were familiar, none was of interest to him today. Sighing with satisfaction, he drank his beer and lit a cigarette. All was well. All would be well, at least. Coupled with the gift of an optimistic disposition he had the knack of finding contentment in small things. Current circumstances were unpromising, but this was a pleasant interval and he wouldn’t spoil it with dismal thoughts. He might be broke today – indeed, he was broke – but that didn’t mean that tomorrow would tell the same story. He wasn’t like the beggars and thieves who populated the Holborn alleys, immured in poverty and unable to help themselves, nor did he resemble the slightly better-off clerks and drovers and shop workers who gathered under the decorated ceilings of this public house as a break from their menial routines.

He was a man of talents.

Devil had finished his pint and was contemplating the possibility of another when a woman screamed, high and long. This was followed by a burst of shouting and cursing. There were the sounds of a scuffle and breaking glass and Devil idly turned to see two bloodied men in shirtsleeves swinging punches at each other. A woman staggered between them as she tried to haul one out of the fray. There was some jostling for a better view and a few shouts of encouragement from the onlookers, but fights weren’t at all uncommon in the Old Cinque Ports. The publican, a muscled fellow with a pugilist’s face, was already shouldering his way across the room to break it up. Devil was about to turn his back on the spectacle when he noticed the child. He was sliding between the drinkers, short as a midday shadow, dipping pockets.

The slut in the red dress began hauling at the other woman, shrieking, ‘Nellie, Nellie! Stop it now, afore ’e kills the both of you.’ Her purse was a leather pouch pinned at her waist and the child had obviously noted that the mouth of it gaped open. With the swirl of the crowd in the path of the approaching publican to his advantage, he pressed close up against the woman and his hand flashed faster than the eye could follow.

He was good, Devil noted.

Amusement, a dart of interest, or perhaps just a sense that he had treated the whore rudely despite having paid for her gin, made him jump from his stool. He leapt through the crowd and caught the boy as he reached the doors. Devil held him by the throat with one hand and grasped his surprisingly sturdy wrist with the other. The doors swung open and the publican booted the brawlers out into the street, followed by the handful of onlookers who wanted to jeer the fight to its end. Devil and his writhing captive stumbled out amongst them and Devil whipped off the child’s cloth cap so he could get a good look at his face. He stared in astonishment at the glare that met his.

The child wasn’t a boy at all but a man, his own age. There were furrows at the sides of his mouth and a jaw dark blue with stubble.

A pocket-picking dwarf. That was a fine thing.

The little man cocked an eyebrow.

‘I’ve seen you in the halls. You’re Devil Wix.’

He frowned. ‘Mr Wix to you. How much did you get?’ The dwarf tried to look offended but Devil snatched him off his feet and shook him until his pockets rattled. ‘How much?’

The feet in miniature boots swung viciously. Devil’s interest quickened. This was a lively little pickpocket.

‘Put me down.’

‘Give me the money you nabbed.’

‘Why should I? It’s not yours, is it? Unless she’s working for you.’

‘Do I look like a pimp?’

The dwarf put his head back, pretended to consider the question, and then shrugged. Devil almost laughed.

The combatants had exhausted their antagonism. One slumped on a doorstep and mopped his face with a rag. The other spat out blood and broken teeth while his whore clung to his arm and wailed. The woman in red stuck her fingers into her open purse and her mouth fell open in dismay. Devil and his captive were beginning to attract attention so he lowered the dwarf to the ground and roughly explored the small pockets with his free hand. He found a few coins – two shilling pieces, a threepenny bit and four pennies. He held out this haul to the drab and her mouth snapped shut again.

‘Don’t throw your money away,’ he advised pleasantly. She took the coins from him with a blink. Dragging his miniature companion by the arm, Devil marched out of the circle and made for the nearest corner. Another hundred yards brought them to a cabmen’s halt where a sign in the smeary window read: ‘Try our champion 4d. dinners’.

‘I feel like I’ve got a hole in me. Let’s eat,’ he said.

‘Got no money. You just stole it,’ the dwarf snarled.

‘I’ll play you for a dinner,’ Devil offered and the little man suddenly grinned, showing pointed teeth that made him look like a wolf backing into the undergrowth.

‘Right then,’ he agreed.

Inside the eating-house damp steam scented with boiled meat and potatoes rose around them and Devil sniffed appreciatively. A score of hungry cabmen clattered and guffawed as they shovelled up their dinners.

They took their seats at a table towards the back. The dwarf was perhaps three feet tall. He hauled himself into place with muscular arms and then settled on his haunches to bring his chin to the right height at the tabletop. He pushed his cap to the back of his head and Devil took a good look at him. His long-chinned but well-shaped face looked too large to be perched on his stunted body but his expression was alert and his hands were quite clean and cared for. He was no vagrant.

‘Cards or cups?’ he asked Devil, who only waved a hand to indicate indifference.

The dwarf took three tin cups out of an inner pocket and with a flourish placed a pea under the middle one. Devil was already bored. The dwarf shuffled the cups, elaborately feinting, and as soon as he sat back Devil pointed. The movements had been practised enough, but not so quick that he couldn’t follow them. He knew exactly where the pea was, and when the dwarf flipped the cup he wasn’t surprised to be proved right.

‘You pay,’ he yawned.

Slyly his companion lifted the second cup and then the third, and there were peas under those too. Devil grinned back at him. The little man had a sense of humour, and his touch wasn’t bad.

‘All right, my friend. You get a fourpenny dinner for your efforts.’

The cups and peas were tucked away and the dwarf rubbed his hands.

‘Are you going to tell me your name, since it seems you know mine already?’

‘You can call me Carlo.’ The dwarf didn’t sound as if he came from London, but neither did he sound as if this exotic label properly belonged to him. He was from the north of England, Devil guessed, although he was hazy about the geography of anywhere that lay beyond Bedford.

‘What kind of name is that?’

‘The one I have chosen,’ his new acquaintance snapped.

A pimply boy leaned over and slapped down cutlery, and at a sign from Devil followed it up with two swimming plates of mutton stew and mash.

‘Or is it a half serving for you?’ this person sneered at Carlo, making to scoop one plate away again. ‘It’s only tuppence for littl’uns.’

‘You put that down,’ Devil ordered. ‘And keep a civil tongue for customers.’

Devil and Carlo ate eagerly. The dwarf dispatched his plateful so quickly that he must have been ravenous.

‘Now,’ Devil said when Carlo belched and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘What’s your story, Carlo from Manchester, or wherever it is and whoever you are? What brings you to London with your quick fingers? Richer pickings down here, is it?’

‘None of your business.’

‘I believe it’s at least four penn’orth of my business now.’

Carlo pursed his lips. He took a handkerchief from his pocket and unwrapped a toothpick from the folds. Applying this instrument to his teeth, he seemed to weigh Devil’s desire for information against his own requirements.

‘Morris’s Amazing Performing Midgets,’ he said at length.

‘Eh?’

‘I said …’

‘I heard. I’m asking you to elaborate.’

Carlo sighed with impatience, as if he could hardly believe that Devil wasn’t already familiar with the Midgets’ reputation.

‘You should know. I know you, and you’re not even first-rate.’ He pronounced it foost. Devil said nothing, amused by the dwarf’s high opinion of himself. ‘High-class act, it was. We didn’t just play the penny gaffs, although I’m not saying there wasn’t times when we were glad to. But we were booked in the better halls, and some private entertainments. We did song and dance, of course, and Sallie had a little piano and a miniature harp, very popular that was, especially with the ladies. Sam and me did a juggling turn, a set of acrobatics, well-rehearsed, top-notch costumes. But the meat and taters of the act was magic. Cards, coins, handkerchers. Miniature. And we ended it all up with a nice box trick. Very nice. All my own work, that was.’

The little man delivered the last snippet of information in a theatrical whisper, tufty eyebrows drawn together, his sharp eyes peering up at Devil. And as he must have known they would, his words made Devil sit up and pay attention.

‘All your own work?’ he repeated. ‘Inventor, are you?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Well, well.’

Devil snapped his fingers at the serving boy who carried away the empty plates and brought them pint mugs of tea. Devil blew on his and took a swallow.

‘Was, you said. Was a high-class act?’

‘Nowt wrong with your ears.’

Devil reflected. He had heard on the circuit or perhaps read in the trades of a northern touring troupe of midgets. The name that suddenly came to him in this connection was Little Charlie Morris.

‘Charlie Morris, that’s who you are. What’s the business with Carlo?’

The dwarf sucked at his teeth to extract the last remnants of food and folded away the toothpick.

‘New start.’

‘I see.’ Devil understood that well enough. ‘What about your sister and her husband?’

He was almost sure, as fragmentary recollections came together, that Charlie or Carlo’s fellow performers had been these two members of his family.

The dwarf’s face flooded with such real sadness that Devil was sure it wasn’t part of an act, nor any attempt at gathering sympathy for mercenary reasons, but the base note of his being.

‘They passed away last year, within a week of each other.’

‘I’m sorry.’

Carlo jerked his head. He added, ‘In-flu-en-za,’ tapping the syllables between his teeth with such finality that Devil didn’t want to upset him by fishing for any further information. But naming the illness seemed to unlock the dwarf’s tongue.

‘My father was like me, my ma’s one of you although she’s no giant. Of us four children there’s two big ’uns and then my sister Sallie and me, and we two always knew we’d have to take care of ourselves because of being small. My dad was a singer in the taphouses. Used to stand him on the counter, they did, and he’d do a ballad and play the piccolo and pass his hat round.

‘Our two brothers went in for mill work but for us littl’uns the best we could have got was being sent to crawl under the looms to collect the waste, and our ma wouldn’t have that. So we were going to join our dad with the act. Make all our fortunes, he said. He trained us up and made us practise the routines, and when we didn’t work hard enough he’d thrash our hides raw with his belt. Poor old Sal used to howl. She was glad to marry her Sam to get away from home. Sam came from Oldham. Just him in the family was small, so it was lonely for him. He was sweet on Sal the minute he saw her. They’d been wed a year when our dad fell off the stage one night when he was corned and hit his head. He didn’t last long after that. I had Sam into the act gladly enough, even though he didn’t have the talent for it. Sal was the one out of the three of us who had the real stage quality. You should have seen her. Like a shining star her face was, under the lamps.

‘We did all right. Then one night Sam was ill with a fever and she was nursing him, and two days after that she was ill herself. Less than a week went by and they were both gone.’

Carlo drank his tea. His mouth tightened as if he regretted having confided so much.

Devil waited. This story would surely lead to a request for money, a bed for the night, a helping hand of some sort, and he was already wondering precisely how much he would be prepared to do for Carlo Morris if the circumstances happened to be right.

The dwarf added, ‘I can’t be a troupe of one, can I? Can’t work the box trick single-handed for a start.’

‘And so you’ve come down to the big city to look for some work in the halls. Juggling, acrobatics, and the magic, I think you said? Just doing some dipping for the practice, were you?’

Carlo smacked his hand on the table so violently that the mugs rattled.

‘Don’t talk to me like I’m a casual fallen on hard times. I don’t need to look for work. I’ve already got a job. And if I’m hungry today and an open pocket is held out to me in an alehouse, am I going to turn my back on it?’

‘I suppose not,’ Devil agreed. This attitude rather neatly matched his own. ‘You performed well enough. First time you’d tapped a purse, was it?’

This time it was Carlo who shrugged and flexed his strong fingers. He climbed down from the chair and straightened his cap on his head. ‘I’d not see Sallie go hungry. Or our ma for that matter, even though she’d slap me round the head quicker than cook me a dinner. Same with you, I daresay.’

‘I don’t have a sister or a mother. I wouldn’t take trouble for them even if I did.’

Carlo tipped his head to scowl up at Devil.

‘It’s not right to speak of family like that.’

‘I’m obliged to you for the sermon.’

Devil reached in his pocket for eightpence, and gave the money to the pimply youth. They made their way back out into the street. Now he had eaten, Carlo seemed relaxed, almost genial. He tucked his thumbs into his pockets and looked about him. Devil supposed that from his perspective the scenery was mostly composed of hansom wheels and women’s backsides.

‘I’m going that way,’ Carlo pointed. For a miniature man in a strange city he seemed remarkably at ease. ‘Why don’t you walk along? You can take a look at my new place of work. You’ll be interested in that.’

Devil wasn’t going anywhere in particular. ‘All right.’

They strolled through the crowds in silence imposed by the three-foot difference in height. They crossed a busy road, with Carlo picking his way ahead. He had to gather himself to spring across puddles that Devil stepped over without checking his stride. They skirted the web of alleys where Devil currently lodged and headed south into the yellow-grey murk of a fading afternoon.

‘Know where you’re going, do you?’ He addressed the button on top of the dwarf’s cap.

‘Do you take me for a fool?’

Devil was still amused. This dwarf was a lively little person.

After a longer interval of walking in silence Carlo led the way out into the Strand. By this time the lamps were lit, each yellow flare wreathing itself in a wan halo of mist. Devil regularly worked in the taverns and supper clubs lining the nearby streets and he had assumed Carlo was heading towards one of these. But the dwarf stopped only when they reached the Strand itself, at a gaunt building on the southern side that Devil had often passed and never troubled to look at. There was not much to be seen anyway because the front was largely obscured by boards, nailed into place with heavy beams to shield passers-by from bricks or chunks of stonework that might fall from the crumbling facade. Tufts of dried brown buddleia sprouted from the cracks in the lintels.

Carlo dipped into the alleyway that sloped along the building’s side. Somewhere further down lay the busy river; the reek of mud drifted up to them. There was a door in the side of the building, the cracked panels just visible in the fading light. The dwarf knocked, waited for a response, and when none came he put his small shoulder to it and pushed it open. The two men stepped into the damp, dark space within.

‘What’s this place?’ Devil asked.

‘You ask a lot of questions, don’t you?’

Devil grabbed his collar. ‘Someone of your size might take more trouble to answer them.’

‘Listen,’ Carlo said.

There was music playing. It was tinny, so faint that the trilling was almost swallowed by the clammy air. They shuffled towards the sound and the glow of light spilling from another doorway.

In the centre of a hall that lay beyond, its shadowy depths hardly penetrated by a pair of gas lamps, a couple was dancing. The music was louder and sweeter here. It came from a musical box held in the lap of a solitary spectator, a very fat man in a heavy old coat. A silk scarf was knotted under his sequence of chins. When the mechanism wound down the fat man lifted the box and turned a handle until it started up again, and the couple went on waltzing. All three of them ignored the new arrivals.

Devil studied the dancers. Carlo swung on to a stool to give himself a better view.

The woman was very young, with long glossy hair that fell almost to her narrow waist. Her profile was serene, her lips slightly parted in a faint smile. Her partner was an attentive man of middle age, his face partly shielded by steel-rimmed spectacles. He danced with great concentration, his head bent so close to hers that his lips almost brushed the lustrous hair. The precision of his steps and his protective bearing suggested that she needed guidance in some manoeuvre more complicated or demanding than a waltz before an audience of one. Devil saw that the man’s shoes were rimmed with the mud of London streets, but the woman’s were pale satin and unmarked. She hadn’t walked here, or anywhere else, in those slippers.

The music stopped and the fat man turned the handle once again. Devil nodded to himself. The oddness of the scene, the dim light, the abundant hair had all momentarily confused him but now he knew what was happening here. He let his attention slide away.

They were in a derelict little theatre. As his eyes acclimatised he saw that it had been partly burned out. The space where the stage would once have been was a mess of charred wood and fallen beams, and the delicately painted walls of the auditorium had been spoiled with smoke. The ruins of seating had been thrown into the corners, and every surface, except for a circle in the centre that had been roughly swept for the dancers, was layered with soot. Yet even in its decayed state Devil could see that this was a harmonious space. A gallery extended its arms almost to the stage, from which it was separated only by two levels of little boxes with apron fronts that had once been lavishly gilded. The gallery was supported by slim pillars, blackened too but still intact. When he looked upwards he glimpsed the ruins of a once-magnificent plaster ceiling.

The last tinkling notes of the mechanical waltz died away, yet seemed to be still echoing in the intimate sounding-box of the hall.

Devil listened, all his senses heightened as a pulse ticked in his neck. What was this place?

‘Thank you, Herr Bayer.’ The fat man was barely smothering a yawn.

The dancers stopped but the man’s right hand still clasped his partner’s, and the fingers of his left rested lightly at her waist. Then he bowed to her and took one step back. As soon as she was released her white arms gracefully descended to her sides. She stood motionless, her eyes glittering. Her faint smile now seemed too fixed.

Devil had seen already that this was not a woman but an automaton.

A well-made thing, but still a thing.

‘She is beautiful, yes?’ Herr Bayer said.

The other shrugged.

Herr Bayer’s voice rose. ‘We have toured in France and Austria as well as in Switzerland. In Berlin we danced for a niece of the Empress.’

The fat man’s chins looked like warm wax melting into his scarf. ‘Tell me, what else does the doll do?’

Herr Bayer recoiled. ‘If you please. Her name is Lucie.’

‘What else does your Lucie do?’

Bayer guided her to a seat across the circle from the fat man. She moved in a stately glide, her head turning slightly on her slender neck as if to acknowledge her admirers. He dusted the chair seat with his handkerchief and she folded at the hip and the knee to adopt a sitting position. Bayer lifted one of her hands to his lips and kissed it.

‘As you see, Lucie stands and sits, walks and dances.’

‘I hear Mr Hoffman has a mechanical creature who plays chess. It will take on any opponent, and it usually wins.’

‘Hoffman’s Geraldo is hardly bigger than a child’s toy.’ Bayer swung on his heel and pointed at Carlo. This was the first acknowledgement from either man of their arrival. ‘And there is a person like him concealed in a box just behind its shoulder, directing the movement of the pieces.’

‘Davenport’s latest invention tells fortunes and reads minds.’

‘He uses a clumsy puppet, a scarecrow, hardly more than that. And the act is a common memory game. Pure trickery.’ Bayer almost spat. His Swiss-German accent grew heavier.

The fat man sighed. ‘It is all trickery. This is what we do.’

‘No.’

Bayer leapt to Lucie’s side. He put one arm round her smooth shoulder as if to defend her from insult. ‘This is no trick. She is what she is, a work of art. A miracle of precision, perfect in every movement. Look at her face, her hair, even her clothing.’

Devil strolled across the circle. ‘May I?’ He reached out to stroke Lucie’s head. The hair was human, but it felt lifeless under his hand. The automaton’s dress was lace and silks and velvet, but there was no breathing warmth within its rich folds. The face was exquisitely moulded and painted and utterly unmoving. He stepped back, faintly disgusted by the doll’s parody of womanhood.

Bayer said, ‘She is lovely, you see? Mr Grady, you will not find a better or more ambitious model to delight your audiences.’

The man smiled but an imploring note had entered his voice. Lucie might be dressed in the latest finery, Devil saw, but her partner’s clothes were worn and mended. The man was another itinerant performer, hungrily searching for a paying audience, just like Carlo and – indeed – himself. For a moment Devil was depressed to think how many such hopefuls there were in London, let alone elsewhere, but he didn’t allow the anxiety to take hold. He would succeed, because he would do anything and everything necessary to ensure that success. And the rest of them could go to hell. He returned to his contemplation of the theatre’s lovely ruin.

Grady put aside the musical box and wrote in a notebook.

‘Very well. Come back here in two weeks. We’ll be ready to open by then. I’ll try you out for a few performances, see whether the crowd takes to you.’

Bayer’s face brightened. He bowed to Grady and nodded to Carlo and Devil, but his proper attention was for Lucie. He wrapped a shawl round her shoulders and kissed the top of her head before bringing forward a brass-cornered trunk and undoing the clasps. The interior was padded with red plush and shaped to accommodate a female form. Bayer lifted the automaton in his arms and gently folded the doll into captivity. Then he hoisted the locked trunk on to a wheeled frame like a market porter’s, bowed again to Grady and took up the handles of the frame.

‘Auf Wiedersehen,’ he said from the doorway as he trundled Lucie away.

No one spoke for a moment. Then the fat man looked at his pocket watch.

‘Let’s get on with it,’ he said to Carlo. ‘What’s your name again?’

‘I told you. Carlo Boldoni,’ the dwarf replied, unblinking. ‘And as I said, direct from performing before the finest drawing-room audiences in Rome. And Paris.’

‘The finest taphouses in Macclesfield and Oldham, more like. Real name?’

‘In our world of magic and illusion what is real, Mr Grady?’

‘Pounds, shillings and pence,’ the fat man snapped, not greatly to Devil’s surprise. Grady looked like a man who would count all three most carefully. What were his plans, and what was the story of this ruined theatre?

Devil considered the possibilities, and the potential for himself, but said nothing.

‘Call yourself whatever you like,’ Grady went on. ‘I haven’t got all day to listen to you. Show me what you’ve got. And who is this?’ He pointed at Devil.

‘He is my assistant.’

Devil opened his mouth and closed it again. There was a time and place.

Carlo hurried into the shadows, then staggered into view once more bearing a pile of boxes and cloths.

‘Here,’ he muttered to Devil. Obligingly he unfolded the legs of a small table as Carlo shook out a green cloth covering. On the cloth he placed an opera hat and a wicker birdcage. He stood in front of his table and made a deep bow to Grady, then whipped a silk handkerchief out of his pocket and mopped his brow as if the effort of setting up his stall had brought on a sweat.

‘I haven’t got all day,’ the fat man scowled.

Carlo fanned himself with the handkerchief. His expression was so comical that Devil smiled. Then Carlo clapped his hands and the handkerchief vanished.

‘Dear me. Where has that gone? Can you tell me, sir?’

‘No,’ yawned Grady.

‘Then I will show you.’

Carlo produced the handkerchief from his pocket and clapped his hands. Once more it vanished, to be extracted from the pocket again a moment later.

‘You see, sir, how useful this is? Especially for a gentleman like you whose time is so valuable. You have only to take out your handkerchief, and never trouble yourself to put it away again.’

Devil knew how this old trick was done, because it was the first he had learned. But he had to acknowledge that it would have taken plenty of practice as well as natural skill to perform it so adroitly.

‘Continue, please,’ said Grady.

Carlo tipped the hat to show that it was empty but for the smooth lining, then pulled from it a knotted string of coloured silks. He whirled these round his head, drew a pair of scissors from the hat and snipped the silks into bright confetti that drifted to his feet. He scooped these fragments into his tiny fists, balled them up and threw them into the air, where they became whole handkerchiefs again. Devil was impressed. Improvising his role he snatched up the hat, bowed over it to Grady and gestured elaborately to acknowledge Carlo’s mastery. This gave him the opportunity to examine the hat, ingeniously constructed with a double interior.

Carlo lifted the birdcage and his sad, long-chinned face peered through the struts at Grady.

‘I have a sweet trick with the doves but I couldn’t leave my birds here with the rest of my old props, sir, could I? All I have to show you is their pretty cage.’

He wafted his fingers inside to demonstrate its emptiness and latched its door, dropped a cloth over the cage, marched twice around the table and snatched the cloth away again. Inside the cage was a crystal ball. Carlo extracted the ball and peered into the clear interior, rubbing his chin and muttering.

‘What have we here? Ah, this is a vision worth seeing, Mr Grady. We have a packed theatre, ladies and gentlemen applauding until their hands are ready to drop off, a heap of guineas, and handbills announcing the Great Carlo Boldoni in letters as high as himself.’

Grady stuck out his slab of a hand. Turning a little to one side Carlo blew on the ball and gave it a polish with his sleeve before handing it over. Inside the glass an orange now glowed.

‘Doesn’t look to me like even one guinea,’ Grady scowled.

‘You need magician’s eyesight, perhaps.’ Carlo retrieved his crystal ball, replaced it in the birdcage and covered it once again with the cloth. He settled the hat on his head and began to gather up his boxes. Almost as an afterthought he whipped off the cloth to reveal that the cage was empty once more.

Carlo tipped the comical hat to one side and thoughtfully scratched his cranium. Then he darted over to Grady, dipped a hand into the man’s coat pocket and brought out the orange. From the opposite pocket came a knife.

‘You look hungry,’ he said, slicing the orange into neat quarters and offering it to Grady.

‘Can’t you do a beefsteak?’ was the reply.

‘Not for a farthing less than five shillings a show.’

Grady gave a sour laugh. ‘For you and Her Majesty singing a duet, will that be?’

Carlo sucked one of the orange slices.

‘I have plenty more tricks. And some new ones, all my own, never performed on stage. You need Carlo Boldoni for your theatre opening, Mr Grady. What do you say?’

Devil returned to studying the graceful pillars and the sinuous curve of the gallery. He longed for a brighter light so he could see more.

Grady puffed. ‘I’ll think about it. You heard what I said to the fellow with the doll. The Palmyra will be ready to open in two weeks.’ He gestured to the gallery. ‘Go right through it, we will, get rid of all this old rubbish. Make it look like something.’

‘The Palmyra?’ Devil interrupted.

No, he was thinking. You won’t destroy this place and turn it into some penny gaff for vulgar music hall, not if I have anything to do with it.

Grady ignored him. To Carlo he said, ‘Your assistant doesn’t do a lot to earn his keep, does he? It was named the Palmyra, yes. That’s a town in Arabia, you know. Something like Babylon. What a name, eh? What’s wrong with the Gaiety, or the Palace of Varieties, a label with a bit of a promise in it? Built sixty years ago as a concert hall, it was. Never did any business, though, and the debts piled up until the poor devil who owned it went under. He died or he topped himself, one or the other, and there were decades of family disputes after that. In the end all the money went to chancery and they had to sell up.’

Grady tapped the side of his nose and Devil almost laughed out loud. The man was absurd. ‘The price was keen, I can tell you. Shall we just say that Jacko Grady is now the proud possessor? And under his management the old Palmyra will be the finest music hall in London.’

‘Don’t change the name,’ Devil said.

‘What?’

‘If I’d been clever enough to buy an opportunity like this, I’d keep the name. It’s different. It’s got class. More than you could say for the Gaiety.’

‘If I want your opinion I’ll ask for it. Which is about as likely as our friend here hitting his head on the Euston Arch.’ The fat man wheezed with pleasure at himself. ‘Who are you, anyway?’

‘I am Devil Wix.’

The dwarf hovered in Devil’s line of sight, gesturing to him to shut up.

‘Is that supposed to mean something to me?’

‘Why not? You are an impresario and I am a stage magician.’

Carlo gestured more urgently. Jacko Grady displayed no sign of interest and Devil thought, Six months. That’s about as long as you’ll last as the manager of your Palmyra. Money is the only thing that interests you.

Devil strolled to Carlo’s table and picked up the opera hat. He showed the empty interior to Grady, made a pass and extracted the dwarf’s scissors from their concealed place. Then he reached into his coat pocket and took out his own forcing pack of cards. He flexed his fingers, expertly shuffling so the cards danced and poured through his hands. He fanned them and offered the pack to Grady.

‘Any card. Memorise it and put it back.’

Grady yawned again, but did so. Devil shuffled again and then spun in a tight circle. He flung the cards in the air, brandished Carlo’s scissors and snipped clean through a card as it fell. Then he dropped to his knees and retrieved the cut halves. He held them up.

‘Ten of diamonds?’

Grady nodded. Devil gathered up the fallen cards and placed the cut card in the middle. He shuffled once more and held out the fanned pack. Grady’s thick forefinger hesitated, withdrew, hovered and then pointed. The card he chose was the ten of diamonds, made whole again.

The only sound that greeted this was Grady’s chair creaking under his weight.

Devil coaxed him, ‘We have some time between other engagements, Mr Boldoni and I. Try us out, Mr Grady, and we’ll put our new box trick on for your customers before anyone else in England sees it.’

Carlo’s signals grew more imperative but he held still as soon as Grady turned his glare on them.

‘What’s this new box trick?’

Devil improvised rapidly. ‘Ah, the Sphinx and the Pyramid? Mystery, comedy and Arabian glamour all in one playlet. Don’t tell me that’s not made for the Palmyra. There’s a lot of interest from other theatres. You’ll regret it if you let another management snitch us from under your very nose …’

Grady still spoke to Carlo. ‘All right. If I don’t see anyone better in the meantime I’ll put your act on when we open. Half a crown a performance, and you’ll play when I tell you to whether it suits you or not. That’s for you and your assistant, Satan or whatever he calls himself.’

Carlo ran forward and stood in front of Grady’s chair, legs apart and fists on his hips.

‘Five bob.’

Grady spat out a laugh that turned into a phlegmy cough. Carlo’s face turned livid with anger.

‘I said five bob. I won’t do it for less.’

Grady finished his coughing into a handkerchief and wiped his face. ‘Then don’t do it at all. It’s no trouble to me, I assure you.’

Devil smoothly interposed himself, dropping a reassuring hand on Carlo’s shoulder.

‘I am Mr Baldano’s manager as well as his assistant.’

‘I thought he said Boldoni.’

‘… And we are prepared to work for half a crown a show, with just one small stipulation.’

‘What might that be?’

‘For every show we appear in that plays to more than eighty per cent capacity, Boldoni and Wix take a percentage of the box office.’

‘What percentage?’

Devil hastily ran figures through his head. Bargaining against calculations of this sort had previously only taken place in his wilder fantasies, but his fertile imagination meant that was fully prepared.

‘Ten.’

Jacko Grady looked cunning. Clearly he thought that the likelihood of playing regularly to houses more than eighty per cent full, against all the competition from taverns and music halls in the nearby streets, was sufficiently remote as not to be worrisome.

‘All right.’

Carlo and Wix presented their hands and the fat man ungraciously shook.

‘I’ll bring a paper for you to sign. Just to be businesslike,’ Devil said. Grady only swore and told them to get out of his sight.

Darkness had fallen. Carlo and Devil stood with Carlo’s stage props and boxes in their arms as the tides of vehicles and pedestrians swept past along the Strand.

Carlo was boiling with fury. Devil thought the dwarf might be about to kick him and he tried not to laugh out loud.

The dwarf spluttered, ‘The Sphinx and the Pyramid? What blooming rubbish. What’s Grady going to say? We haven’t got any Arabian box trick.’

‘Then we’d better get one. You talk about your new trick, all your own work. We can dress that up, whatever it is, with a few frills. We’ll start tomorrow. Where’s your workshop?’

‘I haven’t got a damned workshop. You had to buy me my dinner. I haven’t even got anywhere to sleep tonight.’

Devil looked down at him. The dwarf was defiant.

‘You told me you had a job already, starting tomorrow?’

‘I knew I’d have one, once I’d shown him what I can do. I’m good. I’m the best. Compared with Carlo Boldoni you are just a tradesman.’

It was true. The Crystal Ball and the Orange had been something special, even though Jacko Grady was too stupid and too venal to have appreciated it.

‘So I’ll be your apprentice, as well as your manager.’

‘Boldoni and bloody Wix? What d’you mean by that? And all the gammon about ten per cent of nothing, which is nothing? I want five bob to go onstage. I don’t need you to manage me, thank you kindly.’

A lady and gentleman were lingering to watch the comedy of a dwarf squaring up to a full-grown man.

Devil stooped to bring his face closer to Carlo’s. He said gently, ‘You do need me. And you will have to trust me because I am putting my trust in you. That is how we shall have to do business from now on, my friend.’

‘I am not your friend, nor are you mine,’ the dwarf retorted.

Devil good-humouredly persisted. ‘I’ve also got a roof over my head, even though it’s not Buckingham Palace. You can come back there with me now. I’ve got bread and cheese, we’ll have a glass or two of stout, and we can start work on the box trick in the morning.’

Carlo’s fury faded. Devil could see that under his bravado the little man was exhausted, and had battled alone for long enough.

‘Come on,’ he coaxed.

Carlo said nothing. But after a moment he hoisted his boxes and began to trudge northwards, at Devil’s side.

Later that night Devil sat at the three-legged table in the corner of his attic room, an empty ale mug at his elbow. Apart from chests and boxes of props the only other furniture was a cupboard, two chairs, his bed and a row of wooden pegs for his clothes. It was cold and not too clean, but by the standards of this corner of London it wasn’t a bad lodging. The landlady was inclined to favour Devil, and he took full advantage of her partiality.

Devil was watching the dwarf as he slept, rolled up on the floor in a blanket with one of his prop bags for a pillow. He twitched like a dog in his dreams.

Devil wasn’t ready for sleep. He thought long and hard, tapping his thumbnail against his teeth as his mind worked.

TWO (#ud91d1780-b217-5f08-bc03-eeac058fdd2d)

The workshop belonged to a coffin maker. Coils of wood shavings had been roughly swept aside and the air was fugged with glue and varnish. Carlo stuck his hands on his hips and scowled about him.

‘Gives me the creeps, this place does.’

Devil raised his eyebrows. ‘We can’t be choosy, my friend. And contrary to your dainty feelings it strikes me as perfect for working up a box trick. Shall we begin?’

‘Don’t try to tell me we haven’t got all night,’ Carlo grumbled. The workshop’s owner had gone off at seven o’clock, warning them that he would be back again first thing in the morning by which time they were to be cleared out, and not to disturb any of his handiwork in the meantime. ‘I’m going to eat a bite first.’

With this he settled himself on the coffin maker’s bench, unwrapped a square of cloth, and tore into a hunk of bread laid with cold mutton. With difficulty, Devil held his tongue. After just two days of Carlo’s company he knew not only that the dwarf’s small body could absorb surprising quantities of food, but that he was always to be the one who paid for it. The end would be worth the outlay, he reassured himself. If the intimations he had already picked up about Carlo’s box trick turned out to be correct.

Jacko Grady was not so stupid as not to have an inkling of the potential too, because without overmuch protest he had signed two copies of the contract prepared by Devil. Ten per cent of box office returns, on every house of more than eighty per cent capacity.

The arithmetic ran in Devil’s head like a ribbon of gold.

Once the dwarf had finished his meal, they turned to the collection of materials assembled to Carlo’s precise instructions and eventual approval. As well as the borrowing of a handcart and the negotiating with sawyers and metal smiths, the procuring of everything had obliged Devil to use almost the last of the sovereigns he kept hidden under the floorboards and in various other niches in his lodgings. The bribe to the coffin maker for night-time use of his premises had taken most of what was left.

‘This had better be a dazzler,’ he muttered.

To answer him Carlo rummaged in one of his bags and produced an armful of metal. This he assembled to make a knife with a blade as long as himself. He whipped the air with it, then drove the point into the rough floorboards before leaning on the handle to demonstrate the weapon’s strength and flexibility.

‘In my costume as whoever you please, Pharaoh perhaps, or the Medusa, or Milor’ the Frenchie Duke – it don’t matter – I will stand, so,’ said the dwarf, taking up his position in what might be the centre of the stage. ‘For whatever reason it is, you will cut off my head. It will drop into a basket, most like, and my body will fall to the ground.’

‘Good,’ Devil replied. ‘Is that all?’

Carlo glared. ‘Wait, can’t you? My headless torso remains. Onstage with us we’ll have the cabinet, ornate as you like, on four legs.’

‘Or on what appears to be four sturdy legs?’

‘Yes, yes. You know what the mirrors are for.’

‘And what I paid for them,’ Devil added.

‘Don’t you ever shut up? You will cross the stage to open the cabinet and within it will appear …’

‘Your severed head. Floating in mid-air, I assume?’

‘Aye. So we talk. There’ll likely be some pact, and your end of the bargain will be to put my head back.’

‘So I close the cabinet doors.’

‘You do. There’s the mumbo jumbo and the lights flash. In an eye-blink there is my living, speaking head secure on my neck again.’

‘I hold the basket up, empty except for the horrible bloodstains.’

The dwarf yawned. Devil tapped his teeth with his thumbnail.

‘No, wait … I’ve got it. A river of gold pours out of the basket. It’s alchemy, that’s what the trick is. It’s all about the philosopher’s secret.’

‘Theatricals are your department,’ Carlo shrugged.

The two men eyed each other. Devil had been optimistic in his first definition of their relationship. In fact their mutual mistrust was not much diminished by the two days and a night they had been obliged to spend together, nor even by the strange liking that crept up between them. Neither would have cared to admit to this last. Carlo stuck his jaw out while Devil pondered the mechanics.

‘It’s not a new illusion. Monsieur Robin has something similar.’

‘It’s still a sweet trick, and it can be as new as tomorrow if we choose to make it that way.’

This was true. Devil well knew that apart from endless practice it was audacity, force of personality and the glamour of the stage itself that created magic out of mere mechanics. His thoughts ran ahead.

‘As it happens, I know a wax modeller who is employed by the Baker Street Bazaar.’ He strode across to their cache of materials and held up two short ends of deal planking. ‘Show me,’ he ordered.

Carlo returned to a squatting position on the coffin maker’s bench and indicated that Devil was to hold the boards up to his neck. The little man’s head protruded between them as he settled on his muscular haunches. Then he folded his limbs. His knees splayed to the sides and his ankles crossed as he brought his feet towards his chin. His short spine telescoped further, his shoulders rose towards his ears as his arms wrapped round his torso. Devil had to lower the boards, and lower them again as Carlo shrank into a ball of muscle.

‘That’s good. That’s really very good,’ he said. He was impressed. The dwarf had compressed his body into a space that seemed hardly more than a foot square.

‘Watch me,’ Carlo snapped. He breathed in deeply, exhaled, and reduced himself by another inch in all directions.

‘Stop,’ Devil laughed. ‘I am afraid that you will vanish altogether. Can you still speak and move your head?’

‘Of course.’

The dwarf’s head, which was not undersized, rotated freely above the boards. There was no sign of physical strain in his face and his voice was as smooth as cream.

The ribbon of gold in Devil’s head looped and tied itself off into a giant bow.

He put the boards aside and silently admired the way that Carlo unfolded his limbs before stretching his little body upright again.

‘There is just one detail.’

Carlo tipped his head. ‘What’s that?’

‘Your size.’

‘What? My size is our money.’

‘It will provide a significant contribution to our funds, I agree. I acknowledge that. My skills as an actor, as the master magician who will conjure your smallness, will be another invaluable element. I am also our financial negotiator, as you know.’

‘Hah,’ sniffed Carlo.

‘And all my experience dictates that your stature should be our stage secret.’

‘What do you mean by that? I am not ashamed. I want the world to know who I am, Carlo Boldoni, straight from performing before the crowned heads of …’

‘Quite,’ Devil said. ‘I am only suggesting that to reveal your stature to the public would be to take away some of the intrigue of the illusion.’

There was a silence. Carlo’s personal vanity and ambition strained visibly.

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘For this trick, to appear onstage as a full-sized man. Is there perhaps a way you can do that?’

‘Hah,’ Carlo sniffed again. He made a return to his baggage and this time brought out a pair of wooden struts with shaped foot-pieces at either end. Devil watched with interest as he sank to fit these stilts to his boots, then used Devil’s long leg as a prop to haul himself upright again. Their eyes met almost on a level.

‘Walk,’ Devil ordered.

The stilt-walk was well practised, tinged with swagger, like everything Carlo did.

‘That’s good. Very good,’ Devil said again. ‘You could use those to step out in the world like a normal man, couldn’t you?’

Carlo’s face went dark. ‘I am a normal man. My body is the same as yours, bar its length. My feelings are the same as yours and all, except I’m too mannerly to tell you that you’re an ignorant numpty. Until you force me to do so, that is.’

Devil kept a straight face. ‘I am very sorry, and you are quite right. I was rude and tactless. Will you forgive me?’

He held out his hand and after only a moment’s hesitation the dwarf extended his own and they shook. This was a significant moment and they both chose to ignore it.

‘So I get a costume?’ Carlo persisted.

‘Allow me time to work out the details of our drama, and we will have the finest costume in London sewn for you.’

Then Devil unbuttoned his waistcoat and put it aside before rolling up his shirtsleeves. From the heap of timbers he selected and held up one pair of cheap chair legs, roughly turned and bristling with splinters. He was no master carpenter, but he had built plenty of stage devices in the past. This one would have to be the best of them.

‘Let’s get to work,’ he said.

The lantern light threw up their shadows, large and small, against the dirty wall. For the rest of the night the coffin maker’s workshop was as loud with the sounds of sawing and hammering as during the daylight hours.

Dawn was breaking when the two men finally emerged into the street. Carlo was grey with fatigue, rubbing his face and stretching to ease his aching body. Devil looked as alert and handsome as he had done before their night’s work started.

‘I will need a coffin myself if I don’t get some rest,’ Carlo grumbled. ‘I’m going back to your place for a sleep.’

‘I shall see you later,’ Devil replied.

He walked through the tiny alleys and the crowded courts of the area that housed timber merchants, furniture makers, metalworkers, printers and block makers, and emerged into Clerkenwell Road. The sky lightened from grey to pearl and the cobbles underfoot glistened with damp. Birdsong rose from the eaves of the houses and the trees in St John’s Square, competing with the rumble of carters’ wheels. Devil walked slowly, savouring the bite of the chill air and the smell of frying kidneys that drifted from an open window. In Farringdon Road the omnibuses were already crowded and a steady stream of black-coated clerks flowed out of the railway station. Devil was washed along in the tide of men, passing under the florid ironwork of the new viaduct and on down to Ludgate Circus. When he glanced up Ludgate Hill he saw that the dome of St Paul’s was rinsed in the glowing light of the rising sun. He stopped to admire the view. It didn’t often occur to him that the city was beautiful. In general he thought it was the opposite but today, with the satisfaction of a good night’s work completed and the gold ribbon decorating his dreams, he saw its richness and promise reflected in all the domes and roofs and sun-gilded windows.

He was whistling with satisfaction as he paced along the Strand and reached the Palmyra theatre at last.

The frontage looked the same, still boarded up and whiskered with buddleia stalks. Down the side alley, however, there was a change. A heavy new door had been fitted, secured with iron hinges and locks. For good measure a padlock and chain were attached to a massive bolt. That was all good. The threshold and step were spread with sawdust. Devil stooped down and rubbed the damp grains between his fingers. There was work being undertaken here, just as there was at the coffin maker’s. Then, not hoping for anything, he put his shoulder to the door and pushed. It didn’t yield even by a fraction. He resorted to thumping on the door panels but no response came except from a knot of urchins looking out for trouble at the street corner.

‘Ain’t nobody in, mister,’ they jeered. ‘Forgot yer key, did yer?’

They raced away as soon as Devil headed for them. He walked along the flank of the building, running his fingertips over the flaking paint and crumbling stonework. The old theatre seemed to breathe in response to his touch.

‘Here I am,’ he muttered to it. ‘And we’ll see what we shall see, eh?’

Recalling the dim interior, he wanted nothing more than to explore the place properly, in daylight, and without the vulgar insistence of Jacko Grady at his shoulder. For one thing, the box trick he and Carlo had in mind would require trapdoors, and other installations beneath whatever kind of stage would replace the ruined one. He needed to inspect the whole area and take measurements for the construction of his cabinet. Clearly, though, this wasn’t going to happen today. He bestowed a last touch on one of the fluted pilasters flanking the ruined front doors, and looked upwards to the little cupola surmounting the building. He touched the brim of his bowler.

‘See you later.’ He smiled almost tenderly.

He had it in his mind to pay a visit to the wax modeller, who happened to be one of the very few of his acquaintances with any knowledge of the days before Devil Wix, when he had been Hector Crumhall. But this craftsman’s place of work was in Camden Town, a long way north of the Strand. Devil thought he would go home to his lodging first and snatch an hour’s sleep, if that were to prove possible against the racket of Carlo’s snoring.

The series of alleys, growing ever narrower, twistier and more foetid as they led towards the rookery, obliterated all Devil’s benign thoughts regarding the city’s early-morning loveliness. He passed Annie Fowler, already seated in her doorway with a cup of gin, but he ignored her. The low door of the house where he lodged creaked open and Devil stepped inside. A heavy figure immediately placed itself in front of him.

‘Good morning, Mrs Hayes,’ Devil greeted his landlady. ‘It’s a fine day.’

Mrs Hayes folded her arms. ‘It may well be. For those who don’t have to see a blasted midget creeping up and down their stairs, in and out at all hours. What’s that creature doing in my house?’

‘He is my associate, Carlo Boldoni the famous theatre performer, until recently a member of Morris’s Amazing Performing Midgets, no less, and fresh from performing before the crowned heads of Europe …’

She came one step closer to him. ‘Do I care who he is? I can tell you straight off, I do not. He is a dwarf and I find he’s sleeping under my roof without so much as a handshake. I don’t care for him. This is a respectable house.’

‘It is a temporary arrangement, Mrs Hayes. You see, he doesn’t have anywhere else to go at present and I am a kind-hearted fellow. I suffer for my kindness, but I hope you will understand.’ Devil’s voice grew softer. ‘I believe you will, Maria, of all women. You have shown such particular kindness to me.’

Maria Hayes hesitated. She was a large woman in her forties with some of the prettiness of her youth still in her face, her black hair unpinned, and the white folds of her body unconfined by stays. Devil might have assumed she had only just stepped out of her bed, had he not known that she could be encountered in a similar state of undress at any hour of the day. She raised a hand and brushed a stray coil of hair from her flushed cheek.

‘I have, Mr Wix. I have been as kind as I could be.’

Devil lifted a matching coil of hair from the opposite cheek. They were already standing close together and the confined space of the vestibule offered no latitude. Devil used his elbow to nudge open the door of the landlady’s room. It was not a very much more spacious resort. One glance was enough to reveal that Mr Hayes was absent, as usual, nor was there any sign of the slow-witted son of the house.

Maria’s mouth was only six inches from his. He leaned down to close the distance. Her lips obligingly parted.

After the kiss Devil ran his hands over her breasts. He put his mouth to her ear.

‘Tell me, is My Lady Laycock at home today?’

Maria smirked. ‘I’ll have to see if Her Ladyship is receiving visitors this morning.’

‘Won’t you tell her Mr Devil Wix is calling?’

Maria grasped his wrist and yanked him over the threshold. Devil kicked the door shut and she slid the bolt behind them. He put his arms round her and they half waltzed to the stuffy alcove with the bed concealed behind a curtain. The sheets were far from clean and the bolster leaked feathers from its case of greasy ticking. Devil untied the strings of Maria’s chemise and the thought of the golden ribbon came happily into his mind again. His landlady pressed herself against him and her tongue sought his.

‘I find she is at home, and waiting for you,’ she murmured. Her fingers were tugging at his shirt buttons, then her hand moved downwards. ‘It’s a good name for you, wherever you got it. Devil by nature as well, aren’t you?’

Cheerfully Devil tipped her backwards on to the bed and pulled up her grubby petticoat. He got busy, at the same time tasting the sweat of her neck and the rankness of her black hair.

Afterwards they lay on the mattress with a coil of bedding twisted round them. Maria was an energetic performer and Devil hadn’t slept for twenty-four hours. His eyelids were so heavy that he was wondering how he was going to get up the stairs to his own bed. A sudden thumping on the door jolted him upright quickly enough, however. Groaning at the thought of Mr Hayes on the threshold he pulled his clothing together. Maria went undressed to the tiny window and stuck her head out.

‘Stop that racket. Get down to Ransome’s and bring me back a jug of porter,’ she yelled. From this exchange Devil understood that it was her son at the door, not the husband. When she pulled herself back into the room they grinned at each other.

‘You’ll wet your whistle?’ Maria asked.

Devil took her reddened hands and kissed the knuckles of each.

‘I have to go to work, my lovely girl.’

The delighted smile she gave him was almost shy, and her blush did make her look girlish. Devil slid out of the room and softly closed the door before she could mention the dwarf again. Aching for rest he climbed the bare flights of stairs, past doorways to rooms hardly larger than cupboards, which nevertheless housed families of lodgers, until he reached the attic. As he had expected he found Carlo lying on his makeshift bed, fast asleep and snoring like an engine. Devil kicked him as he stepped past, but this had no effect at all. Ten minutes later, his own snores provided a counterpoint.

In the two weeks that followed Devil worked harder than he had ever done, and he had laboured for long, bitter hours on plenty of occasions before this. Nights with Carlo at the coffin maker’s followed on from late evenings of performing his own act at whichever of the taphouses or small halls would offer him a booking. He took the money wherever he could get it. One evening he arrived at the workshop still in his stage costume, such was his eagerness to resume work on the cabinet trick. Carlo eyed him as he discarded his greatcoat.

‘What’s this?’ the dwarf sniggered.

Devil preened. He wore a suit of red cloth, cut to fit so snugly that it might have been a second skin.

‘Ah, my performance costume? It is for a trick called the Infernal Flames. Tonight at Prewett’s they were begging for more.’ This was not strictly true, but Devil was always good at reinterpreting reality in his own favour. ‘But for our grand opening at the Palmyra we will do far better than Jacko Grady has bargained for.’

They turned to their work. The cabinet interior was empty except for a double shelf. Tonight’s work was to line all the inside surfaces with a seamless layer of jet-black velvet. Devil undid a draper’s brown-paper package and smoothed a bolt of fabric on a swept circle of floor. He took a tailor’s tape and called out the measurements in feet and inches and Carlo pencilled them on a sheet of paper. Each measurement was taken twice, to ensure accuracy. The velvet had been expensive to buy and none of Devil’s techniques of persuasion had achieved even a pennyworth of discount. Carlo set to with a pair of shears. He was a dextrous worker and the first neat rectangle was soon cut to the precise size. Devil had applied brush and glue to the cabinet wall and with some cursing and arguing they succeeded in sticking the light-absorbing material in place.

Halfway through the task they stood back to gauge the effect. The finished walls of the box seemed to melt into black space. Even Carlo the perfectionist was pleased.

‘I have some more good news,’ Devil announced. ‘Tomorrow your head will be ready. I am to collect it after we leave here.’

‘At last. So we must begin to work up the beheading. I’ll be needing a suit of tall clothing.’

Devil sighed. There was a deal of investing to be done before any return could be hoped for, but still his confidence held.

Devil and Carlo together had visited the wax-modelling studio of Mr Jasper Button in Camden Town, and Carlo had made his way there alone on three subsequent occasions. He had sat patient and motionless on a stool, with the smells of warm wax and linseed oil and turpentine all round him, while the modeller built up sub-layers and then sculpted pellets of wax over a wire frame. On the last visit the modeller had sorted through a basket filled with plaited hanks of cut human hair, holding up one specimen after another next to Carlo’s head and muttering to himself as he searched for the best match. He ran his fingers through the dwarf’s abundant locks and pulled at the sprouting tufts of his eyebrows.

‘Where does it all come from?’ Carlo had asked.

‘Plenty of people hereabouts are glad to sell the hair off their heads for a shilling or two.’ Jasper held up a long plait of rich copper-gold. ‘This one belonged to a woman who knew that all her youth and loveliness shone out of it, but the day came when she had nothing else to sell. Her hair was just the start of it.’ He dropped the plait into the basket again.

‘If this was quality work, I’d be using human hair on you. See? This is the closest for colour and texture.’ He brandished a salt-and-pepper bunch next to the dwarf’s face and Carlo twisted away from it in disgust. ‘Devil Wix won’t pay for that, of course. You and your model will be making do with an identical pair of horsehair wigs. What are you supposed to be? The good philosopher, isn’t it? Maybe I’ll be generous to you both and give you your eyebrows in real hair.’

Carlo stared at the egg-bald wax head on its stand. The coffin maker’s was creepy enough, but this shadowy place deep in the wrecked streets surrounding the railway yards more than matched it. There was a box containing dozens of glass eyes on the floor at his feet, all unwinking and all fixed on him.

‘You and Wix know each other from back when?’

The other held up a loop of wire, measuring by eye the breadth of skin between Carlo’s brows.

‘A long time.’

No more was forthcoming.

Without meeting the gaze of the glass eyes Carlo tried another topic on the modeller. ‘Odd sort of a job you do, wouldn’t you say?’

Jasper gave him a contemptuous glance. ‘My waxwork of Miss Nellie Bromley in Trial by Jury is the favourite figure in the Baker Street exhibition. I’d not call my artistic work odd. Not by comparison with your own, for example.’

Carlo scowled but said nothing. After that they had posed and modelled in silence.

After a long night at the coffin maker’s Devil walked up from Holborn to Euston and thence along the sooty roads that led to Camden Town. All along the way rough tent encampments lay beside the railway lines and under the arches and bridges. The men, women and children who existed here were black-faced and their ragged clothes were black, as were the heaps of brick rubble and even the dead leaves hanging on the few weak trees. Black smoke billowed from cooking fires and smouldering brick kilns, and the occasional threatening figure lurched out of this murk and mumbled at him. By shrinking inwardly Devil made himself seem smaller and darker too, and he passed through these places without difficulty.

By the time he rattled the latch of the studio door Jasper Button was already at work.

‘Jas? You there?’

‘Where else would I be?’

‘I’d say anywhere you could be, if only you had the choice.’

Jasper ignored him. The streets outside might be warrens of decrepit houses and belching chimneys and gaunt sheds but his studio was snug enough. A blanket hung over the doorway to keep in the warmth, there was a coal fire in a narrow little grate and a black kettle on the hob.

‘You want some tea?’

‘You don’t have anything stronger?’

It was a question that didn’t expect an answer. Jasper Button never touched a drop, and given what had happened to his mother and father Devil understood why not. The modeller warmed an earthenware teapot and lifted the kettle using a knitted potholder.

Devil was stalking the bald wax head, examining it from every angle.

‘What do you think?’ Jasper was eager for Devil’s approval. More than a decade ago, the two of them had played together up in the green fields and lanes surrounding the village of Stanmore. Devil had been the ringleader in those days, the admired and feared chief of a band of boys who had in common their rebelliousness and their longing for first-hand experience of the world they could see from the top of Stanmore Hill.

Devil pretended to consider. ‘I think you have achieved a reasonable likeness.’

‘Go to hell. The head’s not for sale, then.’

‘Poor Jas. What will you do with it, in that case?’

‘I’ll exhibit it. There’s always an audience in the Chamber of Horrors.’

‘True enough. Let’s have a look.’

Jasper lifted the head off the stand and turned it upside down to reveal a meticulously gory cross-section of severed bone, muscle and artery. Devil whistled.

‘I say. That’s very pretty. Is that what it really looks like?’

‘Like enough,’ Jasper said brusquely. ‘Enough to satisfy your tavern audiences, at any rate. If I decide to let you have it, that is. I rather liked your midget friend, so I might just keep his likeness beside me for sentimental reasons.’

‘I expect you will feel even more sentimental about two sovereigns, won’t you?’ He put two fingers into the pocket of his waistcoat where the naked end of his watch chain rested.

‘Let’s see the colour of them,’ Jasper insisted, knowing his friend too well.

The money and the model were exchanged and Devil stowed the waxen version of Carlo in a bag with his scarlet stage costume. Once the transaction was complete he was able to give due praise.

‘You’re a magician, Jas, you know, in your own way. Not in my league of course, but it’s a decent skill. Are you going to pour that tea or leave it to stew?’

Jasper passed him a cup and they settled beside the fire.

Once, long ago, the two of them had been amongst a crowd of gaping children who had watched the performance of a few magic tricks in a painted canvas booth set up by a travelling conjuror on the village square. The man had been more of a tramp than a real performer, and the sleights as Devil now recalled them had been shabby and fumbling. But still, here was a man who could make a white rat appear from a folded pocket handkerchief and who could grasp a shilling out of blue air. They hadn’t been there an instant before, but the rat and the shilling were definitely real. He could still remember how the sleek warmth of the animal had filled his hands when the conjuror asked him to mind it for him, and he could taste the coin’s metal between his teeth when he had tested it with a bite. How had such solid things appeared from nowhere? What strange dimensions existed beyond the range of his limited understanding?

Everything he had known up to that point had been narrow, painful, humdrum, and devoid of mystery. There was his own confined world and then there was beyond, somewhere out of reach, where great events took place. Yet here he was in the centre of the ordinary with the extraordinary somehow taking place right in front of him. To witness the magic had been his first experience of wonder, and it had filled his childish heart with yearning.

All around him his friends and their brothers and sisters were shouting and jeering and trying to grab the rat or the shilling but Devil was silent. All he wanted was to see more magic, to be further amazed and transported, and at the same time he was envious. Why was it not given to him to create wonder in the same way? What a gift that must be, he thought, as he gazed at the grog-faced man in the canvas booth with his tattered string of silks and his hands that shook so much he dropped his shilling, to the great amusement of the crowd.

Ten-year-old Hector Crumhall hardly knew how, but he understood that the bestowal of wonder was the ticket that was going to carry him out of Stanmore.

At the end of the scrappy show a few halfpennies and pennies landed in the man’s hat. He gathered them up and peered at the skinny black-haired boy waiting at the edge of the booth.

‘Mister? Can I do that with the rat?’

The man coughed and spat a thick bolus into the grass at his feet. The wooden struts came down and the canvas with its daubed stars and moons and strange symbols was strapped into a package ready to be hoisted on the traveller’s back.

‘Only if you learn the craft, boy.’

‘How? How can I learn?’

‘Ah, that’d be difficult enough. I’d say you’d have to find a ’prentice master in the magic trade.’

The man was ready to leave and Devil looked past him down the lane that led southwards to London. The path through a hollow way beneath oak trees and out across the fields had never seemed so enticing.

He begged, ‘Take me with you. If you teach me how to do those things like you did I’ll carry your bag for you, mister.’

The man didn’t even smile. Devil was surprised that his offer wasn’t instantly taken up. He thought he would make a fine apprentice.

‘You stay here with your ma and pa. You don’t want to be getting yourself a life like mine.’

With that he picked up the last of his belongings and trudged away. Devil stood and watched until the man turned the corner. His body twitched with longing to follow. For weeks afterwards he daydreamed about magic and regretted his failure of courage when the moment of opportunity had presented itself.