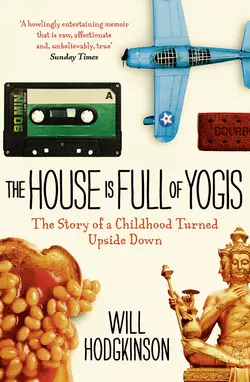

The House is Full of Yogis

Will Hodgkinson

A witty memoir about the trials of adolescence, the tribulations of family life and the embarrassment that ensues from having larger-than-life parentsNeville and Liz Hodgkinson bought into the Thatcherite dream of home ownership, aspiration and advancement. The first children of their working class parents to go to university and have professional careers, they lived in a semi-detached house in Richmond, sent their sons Tom and Will to private school, and went on holiday to Greece once a year. Neville was an award-winning science writer and Liz was a high-earning tabloid hack.Then a disastrous boat holiday, followed by a life-threatening bout of food poisoning from a contaminated turkey, led to the search for a new way of life.Nev joined the Brahma Kumaris, who believe evolution is a myth, time is circular, and a forthcoming Armageddon will make way for a new Golden Age. Out went drunkendinner parties and Victorian décor schemes; in came large women in saris meditating in the living room and lurid paintings of smiling deities on the walls. Liz took the arrival of the Brahma Kumaris as a chance to wage all-out war on convention, from announcing her newfound celibacy on prime time television to writing books that questioned the value of getting married and raising children.By an unfortunate coincidence, this dramatic and highly public transformation of the self coincided with the onset of Will’s adolescence. This is his story.

The House Is Full of Yogis

WILL HODGKINSON

Copyright (#ulink_66ca3e5e-60a0-5a95-838d-62fe2f940cf2)

Borough

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Will Hodgkinson 2014

Will Hodgkinson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014 Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007514632

Ebook Edition © June 2014 ISBN: 9780007514618

Version: 2015-02-06

About the Book (#ulink_3661c405-d608-5756-9fde-8f5ddcfd0c1f)

Once upon a time in the 1980s, The Hodgkinsons were just like any other family.

Liz and Neville lived with their sons, Tom and Will, in a semi-detached house in the suburbs of Southwest London. Neville was an award-winning medical correspondent. Liz was a high-earning tabloid journalist. Friends and neighbours turned up to their parties clutching bottles of Mateus Rosé. Then, while recovering from a life-threatening bout of food poisoning, Neville had a Damascene revelation.

Life was never the same again.

Out went drunken dinner parties and Victorian décor schemes. In came hordes of white-clad Yogis meditating in the living room and lectures on the forthcoming apocalypse. Liz took the opportunity to wage all-out war on convention, from denouncing motherhood as a form of slavery to promoting her book Sex Is Not Compulsory on television chat shows, just when Will was discovering girls for the first time.

About the Author (#ulink_5e70c1ea-d40b-5b26-8021-35a18a863d78)

Will Hodgkinson grew up in a larger-than-life family. His father, Neville, was an award-winning science writer until he received a calling from the Brahma Kumaris in 1983. He currently lives with them on a retreat in Oxfordshire. His mother, Liz, continues to write for the Daily Mail. His brother, Tom, created the Idler. As well as working as the rock and pop critic for The Times, Will decided it was high-time to record his family’s colourful story. Will lives in southeast London with his wife and two children.

Praise for The House is Full of Yogis: (#ulink_9c02e6b0-1bb6-5ba6-8ccd-929b54ad3560)

‘A touching account of a family thrust by mid-life crisis into meditation and spiritual awakening … [A] sweet, quirkish gem of a memoir … an affecting, and very funny, evocation of adolescence’

Mick Brown, Telegraph

‘A My Family and Other Middle-Class Animals let loose in the jungle of Thatcher’s suburban Britain. The result is a howlingly entertaining memoir that is raw, affectionate and, unbelievably, true’

Helen Davies, Sunday Times

‘[A] charming, entertaining book’

Melanie Reid, The Times

‘I have been banned from reading in bed as it makes me laugh out loud too much … Punishingly funny, and wonderfully written’

Rachel Johnson, Mail on Sunday

‘Endearing’

Ben East, Observer

‘[Hodgkinson] has a lovely, light style … his set pieces are very funny … He is attentive to the minute social divisions that define the British middle classes … it’s a relief to read a memoir that is so affectionate, so moan-free, so reluctant to apportion blame’

Rachel Cooke, New Statesman

‘An utterly charming, funny and touching memoir’

Sathnam Sanghera, author of Marriage Material

‘A rip-roaringly funny read’

Viv Groskop, Red Magazine

‘Thoughtful, heartfelt and so well drawn … [It] deserves to become as well loved as My Family and Other Animals’

Travis Elborough, author of London Bridge in America

‘I laughed until I levitated’

Jarvis Cocker

Dedication (#ulink_1add9289-48e5-5ff0-a4ba-a03d8b17ae5a)

For Nev, Mum and Tom

Some names have been changed.

(But most have stayed the same.)

Contents

Cover (#u98e7c28a-cf7a-56d3-8660-8048d36c932f)

Title Page (#u72a2f12f-9c8d-583e-9dfb-b6aad29359a1)

Copyright (#u6d0c253d-53a4-5e9b-a7d8-2a100ccb12a8)

About the Book (#ubf66f9ee-7725-5a06-a78f-40e3a0f64520)

About the Author (#u8e6e2577-0182-563b-8794-97cfedc341f0)

Praise for The House is Full of Yogis (#u0b7019d4-db1f-58ba-b873-be3ca4063708)

Dedication (#u3aced86e-9e4c-5c28-99ed-26cee1c2804d)

1. The First Party (#u570e849a-8471-5a6a-91d0-53e546275b03)

2. The Boat Holiday (#u4fb12e82-8d54-51b2-aceb-e3538942cc6e)

3. The Wrong Chicken (#u64a3b713-a461-5343-8da0-4a5912a9fa9a)

4. Nev Returns (#ub0ef63f1-e408-5261-991f-75b4e2dfd6f7)

5. Enter The Brahma Kumaris (#litres_trial_promo)

6. The End Of The World (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The Second Party (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Forest School Camps (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Delinquency (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Frensham Heights (#litres_trial_promo)

11. The Third Party (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Florida (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Sex Is Not Compulsory (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Surrender (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_58136ddf-d4e7-5dee-b0c2-37022e197fea)

The First Party (#ulink_58136ddf-d4e7-5dee-b0c2-37022e197fea)

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Mum.

She was scratching at two cables of ancient wire sticking out of a dusty hole in the brickwork next to the peeling green paint of the front door, after the Volvo had wobbled over the rubble-strewn drive and come to a shaky halt. ‘They’ve even taken the bloody doorbell.’

A year before our father had his Damascene moment, we moved into our first big home.

99, Queens Road was a semi-detached, four-bedroom house on the edge of Richmond, Surrey, which our parents bought for £30,000 from an older couple called the Philpotts. There was no central heating in 99, Queens Road, nor was there a kitchen to speak of; just a Baby Belling cooker, a rattling old fridge and a twin-tub washing machine stranded in the centre of the room like a maiden aunt who had turned up two decades earlier and never left. There was a milk hatch cut into the outside wall that had come free of its hinges.

The Philpotts, who called their 42-year-old son’s room The Nursery and who claimed to speak Ancient Greek on Sundays, had ripped out pretty much everything but the bricks. The carpets had gone. There were no light bulbs. If you opened cupboards you found only empty spaces, suggesting the Philpotts had even filched the shelves.

‘Come on Sturch,’ said my father Nev, using a nickname with a derivation long forgotten. It might have had something to do with Lurch, the monstrously ugly butler from The Addams Family. ‘Let’s go and explore upstairs.’

In our old house, my brother Tom and I shared a bedroom, which was less than ideal because of our very different approaches to being children. One Christmas Eve, I came upstairs after kissing our parents goodnight, fully intending to obey Nev’s gentle command to go to sleep and wait until the morning to see what Santa Claus had brought, knowing I would wake up at three and feel around in the dark for the happy weight of a stocking at the end of my bed. Tom was in there already, constructing an elaborate arrangement of strings and levers. When I asked him what he was doing he told me not to question things I wouldn’t understand.

All was revealed around midnight. When Nev walked in, stockings laden with toys, a hammer hit the light switch, pulling a network of strings running up the wall and activating a camera next to Tom’s bed. Nev’s hair turned into a wild frizz at the shock of it. Satisfied with having disproven the existence of Santa Claus once and for all, Tom dozed off until eight o’clock. He was nine years old.

That was four years ago. ‘Out of the way, Scum,’ said Tom, pushing me aside as he hunched up the stairs of the new house. He looked at the bedroom facing the street, lay down on the single bed the removal men had put in there half an hour earlier, pulled out of his pocket a copy of George Orwell’s 1984, and said without looking up, ‘Oh, do get out of my room.’

There is a photograph in our family album of Tom, an insouciant four-year-old, kicking back in a rusty toy car while I, only two and already so outraged at life’s unfairness that my nappy is exploding out of my shorts, try in vain to push him along. It says it all, really.

Nev and I went to explore the room at the back of the house, which Nev suggested could be my bedroom.

‘Look at this place!’ I said, clomping across squeaking, uneven floorboards. ‘It’s got a window and everything.’ I tried to open it but it just made a juddering sound. ‘And wow, a cupboard with double doors.’ At first they appeared to be jammed, but after giving them a good yank they came open – and flew off their hinges. ‘Oh well. Now the room is even bigger.’

I looked out of the window. The garden was long and thin, with a scrappy strip of lawn, a collapsing shed on the left and a vegetable patch along the right. There was a hole in the ground near the end of the garden, which was surrounded by rotting apples. (The Philpotts had taken the apple tree with them.) There was also a late-middle-aged woman with a helmet of frosted hair, bent over and hurriedly collecting something into a plastic bag.

‘Isn’t that Mrs Philpott?’ I said.

Nev came over and peered through the dirty glass. ‘I believe it is. What on earth is she doing here?’

Mum rushed out of the back door. Mrs Philpott stood up and, arching her eyebrows, said: ‘I’m collecting jasmine.’

Mum took root before her, hands on hips. ‘You do realize that we own this house now.’

Mrs Philpott stared at the younger woman and tilted her head forward, smiled slightly as if dealing with a simpleton, and explained: ‘It costs two pounds at the garden centre.’

Mum smiled back. ‘That may be so. But now you have sold this house to us, so you’re going to have to find somewhere else to snip it.’

Mrs Philpott looked at our mother imperiously. She marched down the garden with her cuttings of jasmine, sensible shoes clipping along the cracked paving stones of the garden path and out of our lives forever. So began life at 99, Queens Road.

Tom and I had baked beans on toast that night, eating sitting on the tea chests that filled the kitchen while our parents had an Indian takeaway from silver foil containers. After he finished, Tom poked a finger deep into a nostril, stared at what he found up there, rolled it into a ball, and flicked it at me.

‘Tom just threw a bogey at my face.’

‘Is this true?’ said Nev.

‘Guess so.’

‘Right, Tom. I’m going to fine you 50p. Until you learn to treat people with a bit more respect I’m going to have to hit you where it hurts – the wallet.’

Tom dug around in his pocket, pulled out a 50p coin, and flicked it at Nev. He grabbed wildly for it, missed, and the coin clattered off before coming to a halt somewhere underneath one of the boxes.

‘Butterfingers,’ said Tom, with a yawn.

In a few days’ time, Tom would start at Westminster School. He had won a scholarship, leaving me to fester at a private boys’ school our parents had moved me to a year earlier. That was around the time the serious money for Mum’s tabloid articles with titles like How to Turn Your Tubby Hubby into a Slim Jim began to kick in. I protested that I had been perfectly happy at the local primary school, but this change, along with getting rid of a beautiful car called a Morgan that had the minor disadvantage of breaking down on most journeys, was an inevitability of our new, prosperous, aspirant life. Once the house was cleared of any remaining Philpottian traces and transformed into a temple of soft furnishings and comfort befitting a young modern family on the up, our new life was to unfold here.

‘I want the front room for my study,’ announced Mum. ‘You’re going to have to put shelves up in there, Nev. And I can’t live with this kitchen a minute longer. What we need is a high-end, top-quality fitted kitchen from John Lewis, with a nice cooker.’

‘But you never do any cooking,’ said Tom.

‘That’s not the point,’ said Mum. As she turned her Cleopatra-like nose towards the mouldy ceiling she added, ‘I shall also need a microwave.’

For the next few months, the house underwent its metamorphosis. Beige carpets ran up and down the stairs and hallways. Florid Edwardian Coca-Cola posters and reproductions of Pre-Raphaelite scenes of medieval romance filled freshly painted walls. Nev replaced the doors of my cupboard. We had a drawing room – I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a drawing room before then – complete with chaise longue, real fake fire and a three-piece suite upholstered in green linen by GP & J Baker. At least the Philpotts had left the built-in bookcase that ran along two walls of the drawing room, which meant Your Erroneous Zones, Fear of Flying, Our Bodies, Ourselves and the complete works of Jackie Collins now took up spaces once filled with dusty books on Greek history and Latin grammar. We also had a TV room with beanbags, an Atari games console and a pinball machine, which was a present to Nev from Mum from around the time I was born. An oak dresser found space between the microwave and the new fridge-freezer and gave the kitchen a hint of rusticity. A sweet tin with scenes from ancient Chinese life on its four sides took up occupancy too, on a shelf alongside boxes of Shreddies, Corn Flakes and, in a nod towards healthy eating, Alpen.

Nev worked long hours at the Daily Mail, which, from the way he described it, sounded like a cross between a newspaper office, a prison and a lunatic asylum. There was a woman who was paid to not write anything, a man called Barry with a severe and very public flatulence problem, rats in the basement, a section editor who pinned journalists up against the wall and printers who threatened strike action if anyone so much as suggested they stop at two pints at lunchtime. Despite all this, Nev seemed to be doing well. As the medical correspondent he was breaking big stories: he had the scoop on the first test-tube baby a few years earlier, and now he was one of the first British journalists to cover DNA sequencing and stem cell research. One evening he came back home and announced that an exposé he had written about American petrochemical companies illegally dumping waste into city water supplies had earned him an award from the San Francisco Sewage Department.

‘That’s what you get for writing a load of shit,’ said Mum.

Whatever he achieved, however, never seemed to be enough. The more his star rose, the worse his mood grew. We became used to Nev getting the splash – the front page – and the good cheer that briefly followed, which could result in anything from being allowed to stay up and watch an episode of Hammer House of Horror (and creep up the stairs in sickening terror afterwards), to going on what he called a Magical Mystery Tour, which was a trip to the fun fair on Putney Heath. But it didn’t last. A day or so after Nev broke a major story on a campaign against fluoride in drinking water, or even after winning an award from the San Francisco Sewage Department, he would come back home late, sink into a chair, and scan the day’s papers with a mounting air of defeat.

‘Well,’ he said one evening, ‘there go my plans for a feature on Prince Charles’s new interest in alternative medicine.’

‘How do you think I feel?’ said Mum, clearing our plates a few minutes after putting them on the table. ‘Eve Pollard beat me on the interview with the world’s first man-to-woman-and-back-to-man-again sex change. And she can’t write to save her life!’

Nev and Mum sat at our round pine table, eating takeaway and talking about work. Sweat beads gathered on Nev’s furrowed brow as he bent over a tin foil carton of pilau rice and went through the stack of newspapers that were delivered to our house each morning. One evening, two weeks after we moved into 99, Queens Road, he had just taken off his crumpled beige mackintosh as we sat down for dinner. The phone went. Mum told him it was the office. He rubbed his head as he said, ‘Yes … OK … Is there really nobody else available?’, and when he put the phone down, his shoulders dropped, his head shook, his eyes clenched, and he screamed, ‘Fuck!’ He stood up and shrugged on his mackintosh.

‘I’ve got to go back to the office.’

‘Oh, Nev, you can’t,’ said Mum, with the wounded look of a loving wife and mother seeing all her efforts go to waste. ‘I’ve just put the frozen pizzas in the microwave.’

Another night, I got Nev to help me with my mathematics homework. It involved fractions. Maths seemed at best a pointless abstraction and at worst a cold-blooded form of mental torture, particularly as my maths teacher was an eagle-like man with a beaky nose and talons for fingers who smelt of stale alcohol. ‘On the morrow we shall attempt t’other question, which shall be fiendishly difficult,’ he told us, before dozing off in the corner.

Nev understood mathematics. His parents had wanted him to be an accountant. Tom was a mathematics genius, but asking him anything only got snorts of derision. Mum’s inability to understand even the simplest sums rendered her close to disabled. Nev was the one with the magic combination of patience and skill. That night, though, my ineptitude got the better of him. The entire concept of algebra appeared nonsensical, particularly as the numbers and letters kept jumping about on the page. Eventually, after I had frozen entirely at the prospect of a minus number times a minus number somehow equaling twenty, Nev screamed ‘The answer’s right there in front of you!’ and hammered his finger down on a page of my homework until it left an angry grey blur. His face looked like a balloon about to pop. He wiped his brow, muttered something about being too tired to think straight, and walked out, clutching his head.

The following morning before assembly, I managed to filch all the answers for the maths homework from a boy in the class in exchange for a fun-size Mars Bar. I assumed that would be the last of it but unfortunately the boy, a normally reliable Iranian called Bobby Sultanpur, had just found out that his father had been named by the Ayatollah Khomeini as an enemy of the people, hence his including the words ‘Please let us see a return to glorious Persia in our lifetime’ as part of the answer to an algebraic formula. And I had copied everything out so diligently, too.

‘Hodgkinson!’ growled our teacher, his fetid, whiskery breath a few inches from my face, ‘Your sudden concern for the plight of the Persian aristocracy strikes me as devilishly suspicious. You shall be detained at the conclusion of the school day when fresh horrors, in the form of a combination of long division and trigonometry, shall await you.’

The next Sunday, Tom had some of his new Westminster friends over. They silently trooped up the stairs and into his room like angle-poise lamps on a production line. I followed them. Tom slammed the door before I could get in. Some sort of strange new music, definitely different to Teaser and the Firecat by Cat Stevens, our favourite family album, which Nev described as ‘deep’, seeped underneath the door. I knocked. A boy I had never seen before answered.

‘It’s, uh, your little brother,’ said the boy, arching his head over to Tom, who was sitting with two other boys by a small table, dealing cards. He was wearing a baseball cap and chewing gum in an open-mouthed way, like a ruminating cow.

‘Tell him to get lost,’ he said. ‘No, wait. Gambling is thirsty work. Scum, be a good kid and get us some Coca-Cola, will you?’

‘Fold. Man, I’m out. I’m on a one-way ticket to the poorhouse,’ said a boy, who I discovered later had a father who owned around half of Fitzrovia.

‘I’m folding too,’ said another one. ‘These high stakes give you the sweats.’

I looked down at the table. The boys were gambling away their setsquares, compasses, protractors and rubbers.

‘What are you playing?’ I asked Tom. ‘Can I have a go?’

‘Sort out the brewskis and I’ll think about it.’

Mum was in the TV room, singing along to Songs of Praise in a high-pitched falsetto. Nev was at the kitchen table, hunched over a stack of papers, muttering. I crept past both of them with a bottle of Coca-Cola from the fridge. Neither noticed.

‘I’ve got the drinks,’ I said to Tom. ‘Now can I play?’

Shuffling the cards, Tom said, ‘Shall we deal him in?’

‘Does that mean we have to explain the rules?’ said someone.

Tom sighed and nodded. Then he looked at me and said: ‘The thing is, we haven’t really got the time to “hang out”.’ He made the inverted commas sign. ‘We’re kind of in the middle of a serious situation here. Haven’t you got any of your own friends to annoy?’

As it happened, I did have a friend. A small, sandy-haired child. Will Lee was terrified of water, had a teddy bear called Tipper-Topper, and lived a few streets away in a house as old and as tasteful as ours was new and brash. We had met as four-year-olds at the house of two sisters called the Webbers, during The Lone Ranger of Knickertown. To put the labyrinthine complexity of this role-playing game in simple terms it involved The Lone Ranger (me) and Tonto (Will Lee) riding into a forsaken place called Knickertown (Becky and Elaine Webber’s bedroom) where the piratical inhabitants (the girls) robbed us of all our clothes before casting us naked into the desert (the landing) at the mercy of unspeakable dangers (Mrs Webber). It proved a bonding experience. Becky and Elaine are lost to memory but Will and I have remained inseparable ever since.

I rang the doorbell to Will Lee’s tall, terraced house. A hundred-year-old wisteria clung to the Victorian brickwork and the car, a crumbling estate, rarely washed, gave evidence of the highborn provenance of its owners. Will’s father answered. Hugh Lee was a tall, bald man in his sixties with narrowed eyes and pointed ears. He wore tweeds. He peered down.

‘Hm.’

He turned his head upwards and bellowed ‘Willerrrgh’, before shuffling off to his studio underneath the stairs.

I bounded upstairs, past the three-dimensional paintings of muted, abstract shapes the house was filled with, and which Hugh Lee had been working on every day but never putting on sale since he retired from the Civil Service two years earlier. Will was in his room. I rattled on the glass-framed door and heard a startled yelp come from within.

‘Oh. It’s you. I was reclassifying my fossils.’

Will’s room was not like mine. There were no cheap plastic toys or stacks of comics. There were microscopes, atlases, posters of star formations and glass trays containing the stones Will had collected on the shores of Dorset. ‘Look at this,’ he said, holding up a grey pebble with a few indistinct lines along its smooth surface. ‘What do you think of that?’

‘It’s a pebble. What am I meant to think about it?’

Will closed his eyes. ‘It’s a trilobite. It’s 300 million years old.’

‘Let’s go up to the attic.’

The attic was the best room in the house. Hugh Lee had only semi-converted it, putting in windows and laying down a hessian carpet but leaving the spindly retractable staircase and sloping roof, turning it into a den-like space which Will’s much older half brothers and half sister, now all living elsewhere, had used throughout their teenage years. Next to a record player and a stack of records was a book with a plain brown cover and the words Les Demoiselles D’Hamilton etched in gold down the spine.

‘You have to see this,’ said Will, sitting cross-legged and opening the book on his lap with slow reverence. ‘This guy has an amazing ability to convince women to take their clothes off.’

I looked through the sepia-tinted, dreamy photographs of young women in French country houses, stepping out of tin bathtubs, riding bicycles through the woods in flowing white dresses, and admiring each other’s semi-nude bodies, breasts falling out of thin white blouses. Years later I discovered that the photographer, David Hamilton, had used nymph-like teens as his models, but to me, an eleven-year-old, they seemed sophisticated, fully grown, untouchable. The pictures reminded me of a holiday in the South of France where the women on the beach had gone topless and there was a photographer’s studio in the local town with nudes, posed and artful, in the windows. ‘He’s a lover of the human form,’ said our father, awkwardly, as we passed the studio, before pushing us away from the window and towards the nearest ice-cream stand. Even then, Nev appeared to view the body like other men might view an affair: guilt inducing.

I looked at a David Hamilton image of two girls, their hair in loose, messy buns, sitting on a bed and admiring themselves and each other in an oval mirror. The girls wore dresses, but one of them had pulled the dress up to her waist. She was kneeling. You could see the tan line around her pale white bottom. The photographs were as confusing as they were fascinating. I was used to the sight of breasts because we got the Sun and Mum had told me not to expect all girls to look like Page Three girls, but this was something else entirely: exotic and romantic, otherworldly.

‘I wonder where you meet women like this,’ I said.

‘France,’ Will replied, authoritatively.

I wasn’t sure whether looking at David Hamilton’s girls, and what we called the FF (Faint Feeling) it inspired, should make me feel guilty or not. A few years earlier, Nev had suggested there was nothing wrong with sex. When I asked him about the basics of reproduction he explained that a man put his willy inside something a woman had called a vagina. ‘It sounds horrible,’ I said, but he told me people liked it. On his rather more official talk on the subject two weeks after we moved into 99, Queens Road he sat me down at the kitchen table, took out a textbook, sweated even more than usual, and, as he pointed shakily to an anatomical drawing of the male reproductive system said, in a faltering voice, ‘And here we have the vas deferens.’ The talk was high on technical detail but it left me none the wiser about what you were actually meant to do when the time came.

School wasn’t helping matters. Mine was boys only, which meant girls were less a different sex and more a whole different race. I might have got to meet a few local examples of their kind on weekends had not our parents enrolled me in Saturday Club, a school-run activities service featuring judo, chess, photography and other off-curriculum subjects. There was a way of avoiding the lot of them, however. All you had to do was accompany a certain teacher to the store cupboard and allow him to whack you on the bottom with an exercise book every now and then. Three or four of us sat in there each week, wedged into the narrow space between the metal shelves and the wall. If you hit him back he would say, ‘Ooh, you devil you!’ and pinch your cheek excitedly, but he asked for nothing more. That’s why I felt it was unfair when this teacher was hounded out of the school by an angry mob of outraged parents. Some idiot had told his mother about the store cupboard scene, thereby ruining a perfectly good way of bunking off Saturday Club. From then on I only ever saw the teacher in the changing rooms at the local swimming pool.

The official sex education talk came from Mr Mott, our Rhodesian science teacher with tiny red eyes and a sandy white beard who threatened to whack us with his ‘paddle stick’ should we do so much as snigger at the mention of a spermatozoa. The science room, a poky basement that stank of ammonia and chlorine, was always hot, and he decided to give us the lesson on an unseasonably close autumn morning.

‘Your bodies will be goin’ through many changes,’ he shouted, marching up and down the room and intermittently bashing a pre-adolescent head with the paddle stick. ‘You will be gittin’ pubic hair. You will find your pinnis goin’ hard at inappropriate moments. You will develop fillings for a gil, or, in some cases, a led.’

‘Yeah, Sultanpur,’ said Christopher Tobias.

Mr Mott allowed himself a little smile. ‘Settle down, you bunch of jissies. Right then. We will now be looking it the female initomy.’

It was so hot, and it had been such a long time since I had had anything to drink, that I began to feel faint. I dared not ask Mr Mott to be excused; that would be asking for trouble. Instead, I tried to concentrate on the matter at hand. ‘Look at this vigina,’ Mr Mott barked, tapping the diagram projected above his head with his paddle stick. Hodgkinson, you little creep, git up here and blerry well locate the clitoris.’

My head was swimming with the heat, but to ignore an order from Mr Mott was to sign your schoolboy death warrant. I stood up quickly. And that’s when the blackout must have happened. The next thing I knew I was lying on the floor while the school nurse, a young blonde woman with large lips and a concerned but accommodating manner, fanned me with a copy of It’s OK to Say No.

It was left to the adult world, the world of parents, to provide clues about what went on between men and women, and the real evidence came at our first party at 99, Queens Road. It was on Bonfire Night, a tradition that brought out the best in Nev because of his deep and profound love for blowing things up, fireworks, fire, destruction and chaos in general. And he really outdid himself that year. Alongside getting a huge box of Chinese fireworks with deceptively delicate names like ‘Lotus Blossom in Spring’ and ‘Floating Stars in the Night Sky’, he took us to Hamley’s to find something special. He found it. The Flying Pigeon was an enormous construction that looked like five sticks of strung-together dynamite. It came with a long rope on which it zipped backwards and forwards.

Nev scratched his chin as he studied the Flying Pigeon. ‘This does look pretty good. But it’s very expensive, and it does say that it’s designed for major displays only and definitely not garden parties …’

‘But Nev. Imagine seeing that thing in action.’

A mischievous grin coursed over Nev’s face. The battle for the Flying Pigeon was over. He was powerless in the face of pyrotechnic mayhem.

The party would be a chance to see our parents’ friends again. Among our favourites were Anne and Pete, an actress and a globetrotting businessman who had been our next-door neighbours in the old house until moving to a run-down vicarage in Faversham in Kent. Despite Anne and Pete not having kids, their home had its own games room complete with table football, a fruit machine from the 1940s and all manner of mechanical automata. Every time Pete came back from a work trip to the States he returned with unusual and unavailable toys, for us and for himself.

‘He was always larger than life,’ Mum said of Pete, as she put trays of baked potatoes into the oven. ‘He had an MG when he was at university, while the rest of us were trying to scrape enough to get a bicycle. He’s one of those working class Yorkshiremen that just know how to make money. He was chasing after me for a while. Not that I was interested. Nev may have his faults, but at least he’s got long legs.’

Guests filtered in. Tom and I were on drinks duties. Tom, wearing a black velvet jacket and a clip-on bowtie, took to the job with a lot more enthusiasm than I did, possibly because it gave him a chance to harangue every new person who came along with his latest thoughts on literary theory, advancements in physics and all-round egghead boffin theorizing.

‘Yes, yes … our mother struggles with the great writers,’ he said to one woman in a silver tiara and a plunge-neck ball gown, as he offered her a prawn cocktail. ‘She can manage Jane Austen and the like, but forget about Proust. Beyond her.’

The house filled up. There always seemed to be a woman with a hand on Nev’s shoulder, leaning forward and laughing with him about something. I carried trays of champagne into the drawing room, and all the glasses got whisked away in a flash. Some adults, usually men, took a glass without bothering to look at me; others, usually women, seemed charmed by the idea of an 11-year-old waiter and thanked me effusively and called me a darling child. With typical flamboyance, Pete brought a crate of champagne and a trade-sized jar of pink and white marshmallow sweets called Flumps. I poured half of the Flumps into a bowl and offered them around, along with the champagne. The Flumps did not prove appealing to adults so I decided to eat a lot of them myself, just so they didn’t feel unpopular.

Sandy and John Chubb arrived. John Chubb was some sort of a lord and Sandy, although a working-class girl who had left school at fifteen, had the plummiest voice of anyone I knew: rich, low and gracious. They lived in a huge house in Oxford with two toddlers, where John Chubb spent his weekends windsurfing and Sandy taught yoga in high security prisons, which always struck me as a dangerous career choice for this most glamorous of women. Sandy, looking regal with her thick black hair tied into a bun and a diamond necklace dazzling at her long swanlike neck, came up to Tom and me with presents, even though it wasn’t our birthdays: an album each. She got Tom Transformer by Lou Reed and me Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) by David Bowie. We stared at the cover photographs of these bizarre men, transfixed.

Sandy sat down with us by the record player and put on the Lou Reed album. On the back was a photograph of a butch man and a sexy woman. ‘Which one is Lou Reed?’ I asked her, through a mouthful of Flumps.

Sandy looked at me meaningfully. ‘They both are, Will dear. It’s all about transvestites, and hustlers, and other exotic people from the New York Underworld.’

‘But what are they doing there in the first place?’ I asked her, wondering where on earth the short, muscular, strutting man and the pouting, slender woman would fit in employment-wise to the New York Underworld, which I assumed was America’s equivalent of the London Underground. I certainly couldn’t imagine them in the ticket office.

‘It’s a very different scene over there. Anyway, have a listen to this.’

A song called ‘Vicious’ came on, to roars of approval from the guests. Annie started shimmying with a bearded man, Sandy got up and tried to make a reluctant-but-amused John Chubb dance, Mum was saying something about everyone being so bloody conventional and Pete was cornered by a curvaceous woman who was pressing her considerable cleavage up against him, causing his eyebrows to raise in tandem with the glass of beer in his hand.

I continued to fulfill my role as champagne and Flumps waiter until the Flumps ran out, which was strange because nobody had actually wanted one. Apart from a single Flump that Tom had picked up, stared at, and attempted to jam up my nose, I had, I realized, eaten the lot of them.

Nev appeared, charcoal marks on his sports jacket. ‘OK everybody, let’s go outside. I’ve lit the bonfire.’

It was a huge, bright red pyramid, stacked high with dried branches, planks, an old wooden chair and a punk-themed Guy Fawkes effigy at the top (punks being déclassé in 1981). Nev, Tom and I had been building it for days, adding anything that would burn, and now it was a mighty inferno. Mum brought out the tray of baked potatoes while Nev tied the rope for the Flying Pigeon between the apple tree and a pole holding up the washing line, and I, regretting having stuffed myself with Flumps for the last hour, sat down on the grass and leaned against the large wooden box containing all the fireworks and clutched my stomach.

This was the kind of party I liked, even if I was beginning to wish Flumps had never been invented. There was nothing better than Nev having fun because he spread it in our direction. He liked the same things as us: building dens in the woods, making fires, playing board games and going on Magical Mystery Tours to the local fun fair. He was clearly good adult company too, because all these interesting, lively people wanted to be with him. Mum didn’t like any child-related activities and she probably never had, but she enjoyed a party, while Tom relished having a bunch of adults around on whom to test out his maturity. I was overhearing him declaiming to a silent listener about the life of Dr Johnson, and Mum telling someone about her latest article on why she would rather be interviewing a top celebrity in a fancy cocktail bar than being bored at home looking after her children, when Nev appeared.

‘Sturchos,’ he said, grinning down at me excitedly, ‘I’m going to get it all going with the Flying Pigeon. Want to come over here with me to get a good view?’

‘You go ahead,’ I moaned, waving him away. ‘I think I’ve eaten something that disagrees with me. I’ll just stay here for a bit.’

Nev bounded off, telling everyone to clear the line of fire. If only I didn’t feel like I was going to send a hundred half-digested Flumps hurtling towards the ground I would have been up there with him, as Nev’s passion for anything involving fire and the destruction it wrought was matched only by my own. It was terrible to think that I wouldn’t be close to the mayhem – Nev was much more fun than most fathers because health and safety had never been at the top of his priorities – but my conviction was that if I just sat still for a couple of minutes I could recover from this unfortunate situation in time to enjoy the rest of the party, not to mention the rest of the fireworks in the box behind me.

‘OK everyone,’ said Nev, sparking the wick of the Flying Pigeon with a disposable lighter. ‘Here we go …’

The wick fizzed and sparked. People cheered. There was a high-pitched squeal, like it really was a pigeon whose tail had just been set on fire. A shower of sparks burst out. The pigeon took flight, zipping along the rope, spinning around and sending multicoloured rays of exploding gunpowder out into the night sky … and then it stopped. It fizzled out. Only one of the sticks of gunpowder had been used up.

Nev went to examine his prize item, poking around it to discover that the connection between the first stick and the rest had been broken. ‘Well, I’m not going to see that go to waste,’ he said, and before anyone could tell him not to he ripped the Flying Pigeon off the rope and chucked it onto the bonfire.

It sat there for a few seconds, before blasting into the air in a flash of colour. Then it turned and headed down, straight towards me. There were screams. Nev was running towards it, pipe-cleaner legs leaping forward. It looked like it was going to come down right on top of me – and then it was gone. But I could still hear it fizzing away. Where did it go? It all happened so quickly that I didn’t have time to get up and run before I realized.

From the open-mouthed faces of the people all staring at me, it looked like they had realized too. It was in the box of fireworks.

‘Will, get out of the way!’ shouted Nev. He almost made it over, but it was too late: the chaos began. A rocket screamed its way out of the box and headed straight towards Pete’s admirer, who displayed a nimbleness her curves belied and leapt into a rhododendron bush. A Catherine Wheel span wildly and helicoptered along the ground towards John Chubb’s titled ankles. A psychedelic Mount Vesuvius of dynamite exploded everywhere. I put my hands over my head and crouched as World War III broke out on a suburban lawn. Every time I peeked through my fingers, another firework had escaped. People were running, shouting useless warnings to each other and generally dissolving into panic. There was a red roar behind me for what seemed like ages (actually about a minute). Then it stopped.

I poked my head out. John Chubb and Pete were standing alert and looking up as if defending the party from an airborne invasion. People emerged from behind trees. There were groans but no injuries. I didn’t appear to be hurt.

There was one more explosion, followed by a whizzing sound and the sight of a single white light, floating silently in the night sky, mingling with the stars. It was a parachute firework. I looked up, and then looked at Nev, who was staring at this peaceful, brilliant light in contemplative wonder. He wore an expression I hadn’t seen before: transported and spiritual. He was motionless.

Then he shook himself into action and ran and picked me up from the ground.

‘Sturch! Are you all right?’

‘All right? That was the best fireworks display ever!’

What a dad. Who else could cause a grown-up party to descend into such anarchy? Unfortunately other guests, particularly the women, did not share my enthusiasm. They rounded on Nev as one, screaming at him for almost committing them to a lifetime of blindness and singed hair. And why was his poor son lying there next to an arsenal of lethal fireworks? To see Nev, perspiration clouding up his metal-framed glasses, twitching at his tank top as an army of harridans led by his wife accused him of something approaching child murder was far more disturbing than anything that had happened before.

‘For Christ’s sake,’ shrieked Mum, the ferocity of her coal-black eyes made a little less scary by the fragment of Roman Candle jutting from her bouffant, ‘Will could have been killed.’

‘But I’m fine,’ I shouted.

‘You keep out of this,’ she shouted back. ‘Honestly, Nev, sometimes I think you must have gone round the bend.’

Mum and Pete’s wife Annie went back into the house, arms linked, shooting Nev freezing glances over their shoulders. Pete and John Chubb told Nev not to worry, that nobody was hurt, and that women were mad anyway. Tom stood up, brushed down his velvet jacket, and walked towards the house with his hands clasped behind his back, kicking up dust with his shoes as he resumed his soliloquy on Dr Johnson.

‘Don’t listen to them, Nev,’ I said, as we stood next to each other by the bonfire and watched the flames dance. ‘You did them all a favour. That’s going to be the fireworks night everyone remembers for the rest of their life.’

He smiled. ‘The Flying Pigeon certainly livened things up, didn’t it?’

‘It’s the best thing that has ever happened to me.’

And it was. It was even better than the time Nev got us stuck on a cliff on the Cornish coast. We had to be rescued by helicopter, which dropped us down onto a golf course while Mum watched the whole thing from a sun lounger by the pool of the hotel. In my school essay on the subject I added that there was a terrible storm and several people died.

The guests seemed to forgive Nev for his reckless behaviour quite quickly, as it was only an hour or so later that everyone piled into our drawing room with glasses of red wine or champagne and chatted, laughed and made flirtatious gestures towards one another. I used the opportunity to discard the evidence of my Flumps-related gluttony and chuck the empty jar in the dustbin. Nev looked a little flustered as not one but two women purred around him, while Mum held court as she regaled tales of constant harassment by the men of Fleet Street to a group of men who appeared to have somehow found it within their power to not harass her. I had learned that on these occasions it was easy to stay up late if you amused the adults, so I decided the time was right to try out a few of my favourite jokes on them. Before long I was sitting on the lap of the woman with the large cleavage, who kept calling me a gorgeous lad while intermittently pressing me to her bosom and glugging from a glass of champagne.

‘Here’s another one,’ I said, once I had the attention of most of the people in the room. ‘There was an old lady who bought a very large house. It was such a nice house that she felt she should give it a name, so, after thinking about it for at least a minute, she decided to call it Hairy Bum.’

I had them laughing and I hadn’t even got to the punch line.

‘After living in Hairy Bum for a year she started to feel rather lonely in that big house all by herself, so she got a little dog. She called the dog Willy. Willy and the old lady were very happy until one day Willy went missing. The old lady was terribly worried. She searched everywhere but she couldn’t find him. Eventually she went to the police station and she told them …’

I had to stifle a few giggles here.

‘“I’ve looked all over my Hairy Bum, but I can’t find my Willy!”’

They roared. The woman with the cleavage bounced me up and down. Somebody decided I deserved to taste champagne for the first time. Tom might impress them with his erudition and his little velvet jackets and bow ties, but I was knocking them dead with my ribald gags. Sandy sashayed towards the record player and put the David Bowie album on. I think the quarter of a glass of champagne I was allowed to drink may have gone to my head in a not unpleasant manner because I definitely felt a little unsteady as I went to the toilet. The other children who had been there for the fireworks had long gone, but they were a glum lot anyway and talking to strange kids was never easy. Adults could be very entertaining with a few drinks inside them.

Eventually, Mum told me I really should be getting to bed. It must have been around midnight. The Flumps-induced stomach ache returning might have been why, at an hour when I imagine the party was winding down, I was still lying awake, listening to the sound of a man and a woman entering the room next door. I couldn’t hear their voices but after a series of bumps and bangs I heard the woman groaning, and the bed squeaking, and with my limited understanding of what Mr Mott had taught us I came to a simple but most likely accurate conclusion: they were having sex.

Then something else occurred to me. That was our parents’ room.

It couldn’t be them, could it? After all, they had two children already. Perhaps the madness of the night was causing the natural order of things to be upturned. And as gruesome as the sound was, it was reassuring too. It indicated a sense of stability.

I never heard it again. But I did get a Scalextric for Christmas.

2 (#ulink_c315f84c-5f16-5ee4-a32b-583283451582)

The Boat Holiday (#ulink_c315f84c-5f16-5ee4-a32b-583283451582)

Why our father thought it was a good idea to take the family on a boating holiday on the River Thames is one of those mysteries destined to remain unsolved. I invited Will Lee, who couldn’t swim. Tom brought along a French exchange student, a blond boy with a brightly coloured rucksack called Dominic, who thought he was coming to London to see Madame Tussauds. Our mother was entering into her feminist phase, which had previously been confined to buying ready meals and denigrating Nev but which was to reach a whole new level before the holiday was over.

With the benefit of hindsight, Nev should have done what had worked for holidays past: go to the travel agent on the high street, find a Mediterranean package deal, and lie on a beach for a week in ill-fitting swimming trunks while Tom was chained to the hotel room with a bout of diarrhoea and an Aldous Huxley novel, I went snorkelling and got stung by jellyfish, and Mum sat by the pool with a Danielle Steel, a glass of wine and a packet of Player’s No. 6. That way everyone got to do what he or she enjoyed. Instead, Nev set in motion a chain of events that culminated in near death, nervous breakdown, divorce and a devotion to meditation, spiritual study, communal living and the attainment of world peace through soul consciousness that continues to this day.

Before the holiday actually began it did sound quite pleasant. Judging by the photographs of joyous families in the pages of the riverboat hire brochure, it would be a summery adventure in the English countryside that involved drifting down the Thames, waving cheerily to the anglers on the banks and jumping off the side for a swim as the sun sank into the rippling water while Will Lee watched from the deck. Dominic came over a day earlier from the suburbs of Paris armed with a guide to London, a pair of Ray-Bans and a shaky grip of the English language. Will Lee’s mother Penny had, with the kind of everlasting hope only a mother can have, packed her son’s swimming trunks and inflatable water wings.

Our boat, the Kingston Cavalier III, looked impressive when we reached the boatyard: strong and proud against the weeping willows along the bank of the Thames. A large white motorboat with three levels, it had two tiny bedrooms, one with two berths and one with four, a flat roof and an outdoor deck at the back. Dominic went into the boat, came out again, and burst into tears. Tom pointed at the top bunk, said, ‘That’s mine,’ and hurled himself up onto it with a paperback of Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not A Christian and a yawn.

While Will Lee and I loaded on the suitcases and a large hamper filled with fun-size Mars Bars, cocktail sausages and bottles of wine, Mum changed into her nautical outfit of white three-quarter-length trousers, espadrilles with heels, black-and-white T-shirt and a white captain’s hat. Nev spent an hour with the manager of the boat hire company, going through the boat’s workings, the laws of the river, and what to do when you needed to moor, anchor and guide the boat through a lock, nodding intently throughout. We were each in our own way prepared.

It started off well. Nev steered the Kingston Cavalier III out of the boatyard with calm, Nev-like diligence. When Tom told Dominic that we were heading in the direction of London he perked up, said, ‘Madame Tussauds, c’est la?’ and pointed down the river. Tom gave him a thumbs-up and went back to Russell. At first, Mum seemed content to sit in a folding chair on the deck with a glass of wine and a copy of Patriarchal Attitudes by Eva Figes, and make less than generous comments about the size of the bottoms of the women who hailed us from boats going in the other direction. Will and I climbed onto the roof and stayed there. The lapping lulls of the water and the singing of the birds, even the unchanging hum of the engine, were as restful and as reassuring as the sight of an old friend or a cup of hot chocolate before bedtime. Sunlight streaked through the willows and bathed the river in a golden glow. Cows in the fields beyond the banks bowed their gentle heads to the ground. Crickets chirped. The warmth of the sun soaked the land and brewed a woozy kind of contentment.

Then it began.

‘I hope you don’t think for a minute that you’re the captain of this ship just because you’re a man,’ Mum squawked, like a peacock whose tail had been yanked. ‘I can do a much better job than you. I can play tennis better than you, I can earn more money than you, and I can damn well steer a boat down the river better than you. I’m no longer going to be the woman you wish me to be, or fear me to be.’ Her captain’s hat wiggled with indignant satisfaction at that particular line.

Nev pushed up the bridge of his glasses. ‘What on earth are you talking about?’

‘You’ve had your turn. Now it’s mine.’ Whether she was talking about driving the boat or life in general she didn’t specify, but as we were going along a wide, quiet stretch of the river with no lock, island or pleasure cruiser in the way, Nev gave a light smile and said, ‘Of course you can drive the boat, although I can hardly see how you’ll be able to do a better job than me. Do you want me to explain the basics to you?’

‘Stop patronizing me, you male chauvinist pig,’ she said, jerking him out of the way by the scruff of his v-necked tank top and grabbing the wheel.

Mum cranked the boat up a gear and sped off down the river. This caused the wind to catch her hat and for it to fly off her head. It only fell down onto the deck below, where Dominic was listening to ‘Ça Plane Pour Moi’ on a Sony Walkman, but Mum twisted round to see where it went – and forgot to take her hands off the wheel. The boat swerved violently towards port, or, as she kept insisting on calling it, starboard.

‘What are you doing?’ yelped Nev, who had made the elemental mistake of trusting Mum enough to steer the ship while he went to the toilet. He leapt up the narrow steps, but it was too late. She launched the boat straight towards the bank.

‘Stop panicking,’ she shouted, in a panicked voice. ‘I know what I’m doing.’

What nobody had explained to Mum was that going near the bank on a river doesn’t just run the danger of hitting it with the side of the boat; you can also run aground. Her deep hatred of mud, water and nature in general meant she had never explored rivers, and didn’t realize that they start off shallow and get deeper in the middle. The boat slowed down, made an angry grunt, and came to a halt.

‘What’s going on?’ she said, hair billowing about in the wind. ‘There seems to be something wrong with this vessel. Did you get ripped off again?’

‘We’ve run aground.’

‘Don’t be stupid. The boat is still in the water. We’re surrounded by the bloody stuff.’

‘The bottom of the boat is stuck in the mud.’

‘Mud! I’ll soon get us out of it,’ she said, slapping her hands together as if preparing to defeat an old foe. Dominic handed her back the captain’s hat. She adjusted it to a jaunty angle, and then she turned the engine on. Before Nev could stop her she did the one thing you mustn’t do if you run aground: rev up and attempt to move forward. This only serves to push the boat deeper into the riverbed.

‘Stop it!’ Nev shouted over the roar, trying to wrestle her away from the wheel. ‘Turn the bloody engine off.’

‘All right, keep your hair on,’ she said, bumping him out of the way. Then she did the second thing you mustn’t do: put the boat into reverse. The mud sucked up into the propellers. Nev switched the engine off.

There was a brief moment of silence, save for the moo of a cow.

‘If you had been listening when I was getting instruction on how to drive this thing,’ said Nev, gasping, his chin remaining unmoving with stoic solemnity as beads of sweat collected in the lines of his forehead, ‘you would have known better than to do that.’

‘If you’re so smart why don’t you get us out of this mess you’ve caused, Mr Smarty Pants?’

The river brings out the best in people, or at least in some people, because a boat of a similar size stopped to help. A middle-aged couple – small, round and in matching blue shorts and tight blue vests, like Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, only married – told us to check in the hull for any leaks caused by damage to the bottom of the boat. It seemed to be all right. They said we mustn’t turn on the engine. They moored their boat against ours and told us boys and Mum to step onto it. Mum kept her nose upwards and her gaze in the opposite direction as the man stuck out a short, wide arm to help her across. The couple tied a rope to the front of our boat and pulled us out like a knife through melting butter. They looked at one another and nodded in satisfaction.

Once we were all back on the boat, and Mum was persuaded that it was a good idea to let Nev drive for a while, it settled down.

‘What kind people,’ said Nev, as the boat moved steadily along the centre of the river and resumed its calm mechanical hum, ‘they really saved us back then.’

‘They were so fat though, weren’t they?’ Mum replied, back on her folding chair with a glass of wine. ‘Why do fat people insist on wearing clothes that are too small for them? Do they simply not look at themselves, or can’t they see what the rest of us have the misfortune to see? There’s a term for it, you know. Body dysmorphia.’

Nev shook his head and looked to the river before us, rather than his wife, who was applying lipstick, as she added, ‘Surely these boats come equipped with mirrors.’

Will and I stayed on the roof of the boat, forcing woodlice and spiders into gladiatorial battles, making them form a tag-team against a caterpillar or simply throwing them overboard to face their watery deaths.

By the evening, it looked like Mum had given up trying to be captain of the ship. Nev dropped anchor next to a small island in the middle of the Thames at sunset. Dominic was the first to explore it: he pushed through tangleweed and bracken before disappearing out of view. He ran back, screaming, chased by an angry goose. The water was shallow enough for even Will to venture into the river, up to his waist in the murky green as rays of light flashed across the tiny ripples. A swan glided past, followed by a line of fluffy grey cygnets, horizontal question marks aligned by nature’s symmetry. Tom, never the most physical of boys, stuck his foot in the water from the side of the boat, decreed, ‘cold,’ and scrabbled about in the hamper for a biscuit. Dominic and I pushed off and swam into deeper water as Nev and Mum watched from the boat, sitting next to each other, smiling. I have no idea what they were talking about, but in that brief moment it seemed like they were pleased that they had children, pleased at how life had panned out, pleased to be with each other and to laugh at the world together.

Sitting on a blanket under the canopy of a willow tree, wrapped in towels, we ate cold sausages in bread rolls with tomato ketchup. Mum brought her folding chair onto the island and sank into it while Nev poured Coca-Cola from a two-litre bottle into plastic cups.

‘It’s wonderful to see the boys so happy,’ said Mum. ‘It’s like a scene from Swallows and Amazons. I used to love that book. I remember getting it as a present for passing the eleven-plus and going to grammar school. My brother failed, of course. He went to the secondary modern and look at him now.’

We had heard the story about her glittering education and her brother’s miserable one a hundred times before. I was waiting to hear her compare Uncle Richard to their alcoholic father, who had a minor accident during a brief stint as a lorry driver and used it as an excuse to never work again, but it didn’t come. Instead she said that she was lucky to have such lovely children, and she liked seeing us with our friends, and it was getting late and we needed to get into our pyjamas and clean our teeth.

Mum’s brand of second-wave feminism was in keeping with the 1980s: individualistic and money-based. She argued, inarguably, that there was no reason why her earnings shouldn’t match that of a man doing a similar job, and that girls had not only a right but also a duty to get the best education they could. Given that she entered Fleet Street at a time in the 1970s when it was entirely male-dominated save for the fashion and food pages, you can see why she became so strident. Until recently a woman could not buy anything on hire purchase without a male signatory; an unmarried woman could not get a mortgage; it was not possible to rent a flat with a man unless she was married. On our boat trip Mum was bridling at the choices she had made when she was too young to know better: changing her name, getting married, having children, becoming secondary, in the eyes of the law at least, to a man.

Now she had got to the point in her career where, because Nev was working at the Daily Mail and she was doing big celebrity interviews and lifestyle features for the then more populist Sunday People, she was earning a lot more money than him. Fleet Street was at the height of its powers, with over ten million people reading the Sunday People and the DailyMirror. Mirror Group’s all-powerful printers’ union demanded high pay to keep the presses rolling and journalists’ wages fell in line accordingly. Cushioned and given confidence by a very good salary, Mum felt that certain inequalities needed to be addressed.

Margaret Thatcher was a role model as far as she was concerned: a working-class woman who had got ahead through her own will and intelligence and put the emphasis on material improvement and self-reliance. Mum also took anything associated with the traditional role of the mother as a sign of weakness. Cooking was subjugation, which is why we lived on a diet of frozen pizzas. Getting involved in our schools – beyond screeching at me when I got a D in maths – was for less intelligent, more mundane women, which meant that she acted with outrage when the PTA asked her to bake a cake for the school fête (after calming down, she offered to buy them one from Marks & Spencer’s). And when she stayed out in the evening and matched the men in her office drink for drink and cutting barb for cutting barb, she was doing it for the cause.

One of the most confusing aspects of Mum’s declarations of feminism was that it was other women who were the most frequent source of her wrath. They were the agents of their own misfortune, apparently. Nev, Uncle Richard, her own father and most other men may not have been up to much, but as Mum told it even they were less pitiable than the old school-friend of hers who had been the cleverest girl in the class, only to get married at eighteen to a man in wire-framed glasses who made the family say grace before every meal and clothed his terrified daughters in matching dresses buttoned up to the neck. As for higher profile feminists, Germaine Greer was only bearable if you agreed with everything she said and Andrea Dworkin was a brilliant and brave pioneer, but wrong in one fatal regard: she equated feminism with hairy armpits. Any sensible modern woman knew that taking care of your appearance with fashionable clothes, matching colour schemes and high-end beauty products does not suggest sexual availability but self-worth. A decent wage and a trip to the salon whenever you felt like it: those were the rightful spoils of the women’s liberation movement.

Will and I tortured no more insects that evening. Dominic didn’t mention Madame Tussauds. Tom stopped reading, even. It was dark by the time we were back on the boat, and we took it in turns to clean our teeth in the tiny washbasin before Mum and Nev said goodnight and closed the door of their cabin. We heard the sound of things crashing and breaking, followed by shrieks of laughter, followed by snoring.

Will and I climbed up onto the roof of the boat and lay on our backs, and listened to the grasshoppers harmonize under the stars. For a while there, it did seem like we were a reasonably functioning family.

It turned out to be a brief glimpse of Eden in what proved otherwise to be a descent into Hell. The following morning, Mum stomped off into whatever town we were near to buy the papers while Nev moored the boat and cooked sausages on a camping stove. She came back holding up a copy of the Sunday People, crumpling in the wind and turned to a page with her article on it. Its headline was: How to Fight the Flab and Look Totally Fab. It had a picture of our mother in a purple velour tracksuit, attempting to jump in the air and smile at the same time. Nev also had a much smaller piece in the Daily Mail. It was about a pioneering, morally complex and potentially revolutionary research programme of isolating embryonic stem cells. It didn’t come with a photo byline.

We continued our pointless journey down the river. When she eventually tired of reading her own article, Mum, back in her folding chair, shouted at Nev, ‘I hope you don’t expect me to play the Little Lady, doing all the ironing and cleaning and cooking. You’re bloody lucky I’m here at all. I should be out writing a feature. Do you know how in demand I am?’

Nev, who was steering the boat, replied: ‘Why don’t you go off and write your feature then? You could even fight the flab if you walked the thirty miles or so back to London.’

‘Don’t be silly. Do you think that just because you’re a man you’ve got a right to tell me what to do?’ She grabbed her captain’s hat and stomped towards the steering wheel. ‘Get off. It’s my turn.’

After a brief tussle, Nev shrugged and handed it over. ‘Just try not to run aground this time.’

We came up to a lock. There was a shriek. ‘Nev! What do I do?’

‘Take your foot off the power,’ he shouted, and she did – but not in time. We hit the brick wall of the lock with a loud crunch.

‘Tell your wife to put the boat into neutral,’ shouted the lock keeper as the boat whined and juddered helplessly against the side of the lock, and Will and I helped Nev tie the ropes. Mum raised her nose in a westerly direction. Nev took over once more and told Mum to get away from the wheel and stay out of harm’s way.

‘That was your fault,’ she yelped. ‘You didn’t tell me how to stop it.’

‘Oh, shut up, you hideous bat. There can only be one captain of this ship and that’s me. Once we get through this lock I’m going to have to assess the damage.’

While we waited for the lock to fill up, Mum decided to tell Dominic and Will why they shouldn’t mistake her for the kind of mum who helps her children with their homework or cheers them on at the school sports day. ‘You’re more likely to find me in a glamorous bar, interviewing a famous celebrity,’ she said, pushing up her hat and leaning against the side of the lock. ‘My career is far more important for me to do all those things silly women do. Anyone can bake a cake. I’m part of an exclusive club which holds the media power in London.’

‘Tower of London?’ said Dominic, hopefully.

‘It’s a miracle we’re not mentally deranged,’ said Tom, lackadaisically. He was sitting on the bank, reading. ‘I’m going to have to spend a significant portion of the money left to me in your will on psychiatric fees.’

‘I just don’t see the point in pretending to be something I’m not.’

Despite this, she did then pretend to be something she wasn’t: a bridge. Once through the lock, we all climbed back on the boat. Mum was the last one on. She pushed the boat off from the side, but being in the middle of a tirade about why on earth working-class people had to walk around with so few clothes on the moment the sun came out, she failed to notice that her feet were going in one direction and her hands, which were raised against a pillar, were going in the other.

‘Oh no!’ she screamed. ‘Help!’

Nev turned round to see his wife forming an arch over the water, her behind raised high above her hands and feet, but he was steering the boat and too far away from her to help. Dominic had escaped downstairs to look at photographs of London landmarks, Will and I were on the roof with our dead, dying and wounded insects and Tom was back on the deck, making the most of Mum’s folding chair while he could.

Theoretically, Tom could have saved her. He was only a few feet away. But he looked at her, raised his eyes, and said, ‘Try not to make too much of a splash.’ Will and I sat and watched, frozen. I looked over at Nev. He had his hand over his mouth. ‘Somebody help me!’ she pleaded, before plopping into the water.

We looked down. For a few seconds all you could see was the captain’s hat, floating between the boat and the wall of the lock. Then Mum appeared, her bouffant flattened, mascara running down her cheeks, spluttering.

‘Quick!’ she shrieked. ‘Throw me something! Throw me something to hold onto!’

Tom looked around, stood up, stretched, and chucked the folding chair at her. It landed with a splash a few inches away from her head before sinking out of view.

‘Oh,’ said Tom, peering over the boat and scratching his head. ‘That didn’t work.’

I threw her a rope and pulled her up to the side of the boat until she reached the ladder that ran along its side. With her waterlogged trousers, black-lined face and dripping black hair hanging in clumps from the side of her head, she looked like a deranged rock star trawled up from the riverbed.

When she dried off, after Nev made her a cup of tea and I got her a dry towel to wrap around herself, she dissolved into self-pity.

‘It was awful,’ she said, shivering. ‘I’ve never been so scared in all my life … I had a moment of blind panic. And I hate getting my hair wet. Why didn’t anyone help me?’

I shrugged. ‘Couldn’t really make it in time.’

‘And I couldn’t leave the wheel,’ said Nev. ‘If I had, the boat might have crushed you when you fell in the water.’

‘I was reading,’ said Tom, picking his nose.

‘This whole holiday was your stupid idea,’ Mum snapped at Nev. ‘You know I hate larking about on rivers. I don’t like the countryside, I don’t like mud, I don’t like water and I don’t like being stuck on a boat with four horrible boys and a useless man.’

Given her track record, you might think that now would have been a good time for Mum to sit out the rest of the holiday and stay in a place where she could cause as little damage as possible, like below deck. And at first, deprived of her folding chair, she did indeed disappear into her cabin and indulge in a much-needed (for us) bout of splendid isolation. But she went back to her old ways the very next day.

It was somewhere around Teddington that she decided to take over once more. Initially, Nev refused to let her. He pointed out that her attempts to drive the boat had not been entirely successful.

‘Would you have me chained to the kitchen, cooking and cleaning?’ she wailed, sweeping her arms in the air. ‘Who paid for our house by scribbling away? Whose brains got Tom a scholarship to Westminster? And yet here you are, trying to be the big man. I must say, I find your attitude highly offensive. I suppose you also think that unmarried women are useless nuisances, spare mouths? I wonder how the sisterhood would respond to this, should I write an article about it.’

‘Why don’t you do us all a favour and put a sock in it?’ Nev snapped, which was quite a strong reaction for him. ‘I’ve never patronized you, and given your horrible cooking, the kitchen is the last place I’d want to keep you.’

‘Give me that steering wheel, you. I’ll show you.’

Mum no longer had on the captain’s hat, but she did her best to look authoritative nonetheless as she stood at the prow of the boat. She kept both hands on the wheel and looked ahead. A pleasure cruiser passed and people on it waved; she ignored them. A bunch of kids on a boat similar to ours pointed at her and shouted, ‘Look, it’s Cher.’

We needed to refuel. We came up to a river marina, but getting into it required a degree of skill. A jetty ran around it and it was, of course, filled with boats. Nev, who had been at the back, taking a series of deep breaths with his eyes closed, attempted to take over for this key bit of manoeuvring.

‘I’m perfectly capable of controlling my craft,’ she announced, pushing him away, ‘even if it does hurt your phallic pride too much to let me.’

‘Liz, you’re going in too fast,’ he said, as calmly as he could manage. ‘Take it out of gear.’

Rather than do as she was told, she decided to try and pull the boat round. We thudded up against the jetty. The harbourmaster came running forward. ‘Turn off your engine!’

Boats surrounded us, but by a stroke of incredible good fortune Mum had managed not to ram into any of them. ‘Do you know what you’re doing, darling?’ said the harbourmaster, a youngish man who swaggered up with the proprietary air of someone used to getting people who didn’t know what they were doing out of trouble. ‘Don’t you think you should let your husband take over?’

Mum lowered her eyebrows, gritted her teeth, and snorted. If steam could have puffed out of her ears, it would have done. ‘I’m going to park the boat by that petrol tank up there,’ she said, pointing at the filling station fifty metres or so in front of us. Then she slammed the engine on – and put the boat into reverse.

Mum’s hands flew up in shock. We shot backwards, straight into three boats. Various people stared at us in horror. ‘What on earth are you doing?’ asked one silver-haired woman, peering at Mum with narrowed eyes. The woman was wearing a perfectly aligned, pristine white captain’s hat, which matched her fitted blazer. Mum, who with her unkempt bouffant and extended nails now resembled the terrifying children’s character Struwwelpeter, appeared to think the best thing to do was to escape from the scene of the crime as quickly as possible. She slammed the boat into forward. But it didn’t work. The boat strained, and groaned, and cried, and whined, and bleated like a big metal baby, and moved only a few inches. Nev turned the engine off.

He stared at her.

She looked at him with big, wide, apologetic eyes. Her chin wobbled. Then she began to cry.

After assessing the damage, the harbourmaster told Nev that Mum had most likely got the propeller caught up in the ropes of the other boats. The only way to deal with the problem was to dive down and untangle them. Meanwhile, the man on the boat that Mum hit first came out to apply wood glue to our splintered hull. His wife offered to make everyone a cup of tea. The silver-haired lady watched from a safe distance and smoked a cigarette in a holder and turned her head slowly from side to side in a disapproving but satisfied way.

Nev, in his oversized red swimming trunks, lowered himself into the water. He dived underneath the boat and blindly did his best to untangle the mass of knots that Mum had wrapped around our propeller and, it turned out, the rudder. He would come up for air, gasping and spluttering, spit out a jet of oily green water, and head back down again.

It took two hours.

By the time the last stretch of rope was removed from the propeller, Nev was shivering uncontrollably.

Mum dared to reappear, to hand him a towel. ‘Oh, well done Nev,’ she said, breathily. ‘Good work.’

‘Go away,’ he said. For the first time, it really did look like Mum had broken him. But then he disappeared below deck, came back a few minutes later fully clothed, and said: ‘Right’.

He filled up the boat with petrol and, after thanking the couple that had helped us, glided it out of the marina just before the marina closed. That evening we moored near Hampton Court, where Henry VIII had chopped off the head of Anne Boleyn in order to make way for the significantly more docile Jane Seymour, and ate fish and chips on the bank of the river, Mum sitting a little apart from the rest of us. She stayed by the boat while Nev, Tom, Dominic, Will and me went walking along the Thames. We found a rope, attached to a high bough of a tree, hanging down at the point where the raised bank met the river. Nev swung out on it, manoeuvring his middle-aged but slender body onto the seat of the rope and taking off over the water. Dominic made French-sounding whoops. Will Lee, being small, shot out across the river as if catapulted. Tom somehow managed to step on and off the rope with the same air of indifference he might have had catching the bus on his way to school.

‘Suppose we’d better get back,’ said Nev with a sigh, after an hour of rope swinging and peace.

As Tom, Dominic, Will and I played a game of Monopoly that night, we could hear Nev and Mum talking in the cabin next door. This time, however, it was Nev doing most of the talking. ‘Look at the woman who made me a cup of tea, after I almost caught hypothermia untangling the mess you made,’ he said. ‘That’s the kind of woman I respect. Rather than interfering and criticizing the whole time, she was supportive and helpful. What good have you done on this holiday? You’ve gone out of your way to be as silly as possible; to try and do things you can’t do just to prove a point. And it all went wrong.’

‘I have to stand up for feminism.’

‘Where were your feminist credentials when it was time to dive under the boat? Or are you going to tell me that’s a man’s job? Why didn’t you prove the equality of the sexes when I almost froze to death untangling the ropes and drinking gallons of river water? It’s got nothing to do with feminism. It’s all about your ego and your silly, childish pride and your need to show everyone that you’re the boss, even when you don’t have a … a ruddy clue about what you’re meant to be doing. You don’t stand for anything. You just can’t bear it when the attention is on someone else.’

We sat in the uneasy silence that followed.