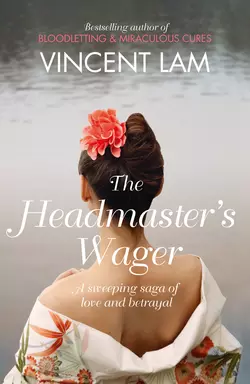

The Headmaster’s Wager

Vincent Lam

From internationally acclaimed and bestselling author Vincent Lam comes a superbly crafted, highly suspenseful, and deeply affecting novel set against the turmoil of the Vietnam War.Percival Chen is the headmaster of the most respected English school in Saigon. He is also a bon vivant, a compulsive gambler and an incorrigible womanizer. He is well accustomed to bribing a forever-changing list of government officials in order to maintain the elite status of the Chen Academy. He is fiercely proud of his Chinese heritage, and quick to spot the business opportunities rife in a divided country. He devotedly ignores all news of the fighting that swirls around him, choosing instead to read the faces of his opponents at high-stakes mahjong tables.But when his only son gets in trouble with the Vietnamese authorities, Percival faces the limits of his connections and wealth and is forced to send him away. In the loneliness that follows, Percival finds solace in Jacqueline, a beautiful woman of mixed French and Vietnamese heritage, and Laing Jai, a son born to them on the eve of the Tet offensive. Percival's new-found happiness is precarious, and as the complexities of war encroach further and further into his world, he must confront the tragedy of all he has refused to see.Blessed with intriguingly flawed characters moving through a richly drawn historical and physical landscape, The Headmaster's Wager is a riveting story of love, betrayal and sacrifice.

For William Lin

Contents

Cover (#u563fd600-e5ee-5ca8-a24b-32e5763847ac)

Title Page (#u4e9143fa-0278-53e5-9e84-cd99d905988c)

Dedication (#u11bb0398-04dc-535d-84d1-f5f8b4e2788e)

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part Two

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Three

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part Four

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Rocks stand stock-still, unawed by time and change.

Waters lie rippling, grieved at ebb and flow.

LADY THANH QUAN

(#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

CHAPTER 1 (#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

1930, Shantou, China

On a winter night shortly after the New Year festivities, Chen Kai sat on the edge of the family kang, the brick bed. He settled the blanket around his son.

“Gwai jai,” he said. Well-behaved boy. “Close your eyes.”

“Sit with me?” said Chen Pie Sou with a yawn. “You promised …”

“I will.” He would stay until the boy slept. A little more delay. Muy Fa had insisted that Chen Kai remain for the New Year celebration, never mind that the coins from their poor autumn’s harvest were almost gone. What few coins there were, after the landlord had taken his portion of the crop. Chen Kai had conceded that it would be bad luck to leave just before the holiday and agreed to stay a little longer. Now, a few feet away in their one-room home, Muy Fa scraped the tough skin of rice from the bottom of the pot for the next day’s porridge. Chen Kai smoothed his son’s hair. “If you are to grow big and strong, you must sleep.” Chen Pie Sou was as tall as his father’s waist. He was as big as any boy of his age, for his parents often accepted the knot of hunger in order to feed him.

“Why …” A hesitation, the choosing of words. “Why must I grow big and strong?” A fear in the tone, of his father’s absence.

“For your ma, and your ba.” Chen Kai tousled his son’s hair. “For China.”

Later that night, Chen Kai was to board a train. In the morning, he would arrive at the coast, locate a particular boat. A village connection, a cheap passage without a berth. Then, a week on the water to reach Cholon. This place in Indochina was just like China, he had heard, except with money to be made, from both the Annamese and their French rulers.

With his thick, tough fingers, Chen Kai fumbled to undo the charm that hung from his neck. He reached around his son’s neck as if to embrace him, carefully knotted the strong braid of pig gut. Chen Pie Sou searched his chest, and his hand recognized the family good luck charm, a small, rough lump of gold.

“Why does it have no design, ba?” said Chen Pie Sou. He was surprised to be given this valuable item. He knew the charm. He also knew the answers to his questions. “Why is it just a lump?”

“Your ancestor found it this way. He left it untouched rather than having it struck or moulded, to remind his descendants that one never knows the form wealth takes, or how luck arrives.”

“How did he find it?” Chen Pie Sou rubbed its blunted angles and soft contours with the tips of his fingers. It was the size of a small lotus seed. He pressed it into the soft place in his own throat. Nearby, his mother, Muy Fa, sighed with impatience. Chen Pie Sou liked to ask certain things, despite knowing the response.

“He pried it from the Gold Mountain in a faraway country. This was the first nugget. Much more was unearthed, in a spot everyone had abandoned. The luck of this wealth brought him home.”

It was cool against Chen Pie Sou’s skin. Now, his right hand gripped his father’s. “Where you are going, are there mountains of gold?”

“That is why I’m going.”

“Ba,” said Chen Pie Sou intently. He pulled at the charm. “Take this with you, so that its luck will keep you safe and bring you home.”

“I don’t need it. I’ve worn it for so long that the luck has worked its way into my skin. Close your eyes.”

“I’m not sleepy.”

“But in your dreams, you will come with me. To the Gold Mountain.”

Chen Kai added a heaping shovel of coal to the embers beneath the kang. Muy Fa, who always complained that her husband indulged their son, made a soft noise with her tongue.

“Don’t worry, dear wife. I will find so much money in Indochina that we will pile coal into the kang all night long,” boasted Chen Kai. “And we will throw out the burned rice in the bottom of that pot.”

“You will come back soon?” asked Chen Pie Sou, his eyes closed now.

Chen Kai squeezed his son’s shoulder. “Sometimes, you may think I am far away. Not so. Whenever you sleep, I am with you in your dreams.”

“But when will you return?”

“As soon as I have collected enough gold.”

“How much?”

“Enough … at the first moment I have enough to provide for you, and your mother, I will be on my way home.”

The boy seized his father’s hand in both of his. “Ba, I’m scared.”

“Of what?”

“That you won’t come back.”

“Shh … there is nothing to worry about. Your ancestor went to the Gold Mountain, and this lump around your neck proves that he came back. As soon as I have enough to provide for you, I will be back.”

As if startled, the boy opened his eyes wide and struggled with the nugget, anxious to get it off. “Father, take this with you. If you already have this gold, it will not take you as long to collect what you need.”

“Gwai jai,” said Chen Kai, and he calmed the boy’s hands with his own. “I will find so much that such a little bit would not delay me.”

“You will sit with me?”

“Until you are asleep. As I promised.” Chen Kai stroked his son’s head. “Then you will see me in your dreams.”

Chen Pie Sou tried to keep his eyelids from falling shut. They became heavy, and the kang was especially warm that night. When he woke into the cold, bright morning, his breath was like the clouds of a speeding train, wispy white—vanishing. His mother was making the breakfast porridge, her face tear-stained. His father was gone.

The boy yelled, “Ma! It’s my fault!”

She jumped. “What is it?”

“I’m sorry,” sobbed Chen Pie Sou. “I meant to stay awake. If I had, ba would still be here.”

1966, CHOLON, VIETNAM

It was a new morning towards the end of the dry season, early enough that the fleeting shade still graced the third-floor balcony of the Percival Chen English Academy. Chen Pie Sou, who was known to most as Headmaster Percival Chen, and his son, Dai Jai, sat at the small wicker breakfast table, looking out at La Place de la Libération. The market girls’ bright silk ao dais glistened. First light had begun to sweep across their bundles of cut vegetables for sale, the noodle sellers’ carts, the flame trees that shaded the sidewalks, and the flower sellers’ arrangements of blooms. Percival had just told Dai Jai that he wished to discuss a concerning matter, and now, as the morning drew itself out a little further, was allowing his son some time to anticipate what this might be.

Looking at his son was like examining himself at that age. At sixteen, Dai Jai had a man’s height, and, Percival assumed, certain desires. A boy’s impatience for their satisfaction was to be expected. Like Percival, Dai Jai had probing eyes, and full lips. Percival often thought it might be his lips which gave him such strong appetites, and wondered if it was the same for his son. Between Dai Jai’s eyebrows, and traced from his nose around the corners of his mouth, the beginnings of creases sometimes appeared. These so faint that no one but his father might notice, or recognize as the earliest outline of what would one day become a useful mask. Controlled, these lines would be a mask to show other men, hinting at insight regarding a delicate situation, implying an unspoken decision, or signifying nothing except to leave them guessing. Such creases were long since worn into the fabric of Percival’s face, but on Dai Jai they could still vanish—to show the smooth skin of a boy’s surprise. Now, they were slightly inflected, revealed Dai Jai’s worry over what his father might want to discuss, and concealed nothing from Percival. That was as it should be. Already, Percival regretted that he needed to reprimand his son, but in such a situation, it was the duty of a good father.

Chen Pie Sou addressed his son in their native Teochow dialect, “Son, you must not forget that you are Chinese,” and stared at him.

“Ba?”

He saw Dai Jai’s hands twitch, then settle. “You have been seen with a girl. Here. In my school.”

“There are … many girls here at your school, Father.” Dai Jai’s right hand went to his neck, fiddled with the gold chain, on which hung the family good luck charm.

“Annam nuy jai, hai um hai?” An Annamese girl, isn’t it? It was not entirely the boy’s fault. The local beauties were so easy with their smiles and favours. “At your age, emotions can be reckless.”

The balcony door swung open and Foong Jie, the head servant, appeared with her silver serving tray. She set one bowl of thin rice noodles before Percival. She placed another in front of Dai Jai. Percival nodded at the servant.

Each bowl of noodles was crowned by a rose of raw flesh, the thin petals of beef pink and ruffled. Foong Jie put down dishes of bean sprouts, of mint, purple basil leaves on the stem, hot peppers, and halved limes with which to dress the bowls. She arranged an urn of fragrant broth, chilled glasses, the coffee pot that rattled with ice cubes, and a dish of cut papayas and mangos. Percival did not move to touch the food, and so neither did his son, whose eyes were now cast down. The master looked to Foong Jie, tilted his head towards the door, and she slipped away.

Percival addressed his son in a concerned low voice. “Is this true? That you have become … fond of an Annamese?”

Dai Jai said, “You have always told me to tutor weaker students.” In that, thought Percival, was a hint of evasion, a boy deciding whether to lie.

Percival waved off a fly, poured broth from the urn onto his noodles, added tender basil leaves, bright red peppers, and squeezed a lime into his bowl. With the tips of his chopsticks, he drowned the meat beneath the surface of the steaming liquid, and loosened it with a small motion of his wrist. Already the flesh was cooked, the stain of blood a haze, which vanished into the fragrant broth. Dai Jai prepared his bowl in the same way. He peered deep into the soup and gathered noodles onto his spoon, lifted it to his mouth, swallowed mechanically. On the boy’s face, anguish. So it was a real first love, the boy afraid to lose her. But this could not go on. Less painful to cut it early. Percival told himself to be firm for the boy’s own good.

From the square below came the shouts of a customer’s complaint, and a breakfast porridge seller’s indignant reply. Percival waited for the argument outside to finish, then said, “What subject did Teacher Mak see you tutoring, yesterday after classes?” Mak, Percival’s most trusted employee and closest friend, told him that Dai Jai and a student had been holding hands in an empty classroom. When Percival had asked, Mak had said that she was not Chinese. “Mak indicated that it was not a school subject being taught.” Percival saw perspiration bead on Dai Jai’s temples. The sun was climbing quickly, promising a hot day, but Percival knew that this heat came from within the boy.

The sweat on Dai Jai’s face ran a jagged path down his cheeks. He looked as if he was about to speak, but then he took another mouthful of food, stuffed himself to prevent words.

“Yes, let’s eat,” said Percival. Though in the past few years, Dai Jai had sprung up to slightly surpass his father’s height, he was still gangly, his frame waiting for his body to catch up. Though everyone complimented Dai Jai on his resemblance to his father, Percival recognized in his silence his mother’s stubbornness. The father’s duty was to correct the son, Percival assured himself. When the boy was older, he would see that his father was right.

They ate. Their chopsticks and spoons clicked on the bowls. Each regarded the square as if they had never before seen it, as if just noticing the handsome post office that the French had built, which now was also an army office. Three Buddhist monks with iron begging bowls stood in the shadow of St. Francis Xavier, the Catholic church that was famous for providing sanctuary to Ngo Dinh Diem, the former president of Vietnam, and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, during the 1963 coup. After finishing his noodles, Percival sipped his coffee, and selected a piece of cut papaya using his chopsticks. He aimed for an understanding tone, saying, “Teacher Mak tells me she is very pretty.” He lifted the fruit with great care, for too much pressure with the chopsticks would slice it in half. “But your love is improper.” He should have called it something smaller, rather than love, but the word had already escaped.

Percival slipped the papaya into his mouth and turned his eyes to the monks, waiting for his son’s reply. There was the one-eyed monk who begged at the school almost every day. The kitchen staff knew that he and his brothers were to be fed, even if they had to go out and buy more food. It was the headmaster’s standing order. On those steps, Percival remembered, he had seen the Ngo brothers surrender themselves to the custody of army officers. They had agreed to safe passage, an exile in America. They had set off for Tan Son Nhut Airport within the protection of a green armoured troop carrier. On the way there, the newspapers reported, the soldiers stopped the vehicle at a railroad crossing and shot them both in the head.

“Teacher Mak has nothing better to do than to be your spy?” said Dai Jai, his voice starting bold but tapering off.

“That is a double disrespect—to your teacher and to your father.”

“Forgive me, ba,” said Dai Jai, his eyes down again.

“Also, you know my rule, that school staff must not have affairs with students.” Percival himself kept to the rule despite occasional temptation. As Mak often reminded him, there was no need to give anyone in Saigon even a flimsy pretext to shut them down.

“But I am not—”

“You are the headmaster’s son. And you are Chinese. Don’t you know the shame of my father’s second marriage? Let me tell you of Chen Kai’s humiliation—”

“I know about Ba Hai, and yes, her cruelty. You have told—”

“And I will tell you again, until you learn its lesson!

“Ba Hai was very beautiful. Did that save my father? An Annamese woman will offer you her sweetness, and then turn to sell it to someone else.”

Percival knew the pull that Dai Jai must feel. The girls of this country had a supple, easy sensuality. It would be a different thing, anyways, if Dai Jai had been visiting an Annamese prostitute. Even a lovestruck boy would one day realize that she had other customers. But this was dangerous, an infatuation with a student. A boy could confuse his body’s desires for love. Percival saw that Dai Jai had stopped eating, his spoon clenched in his fist, his anger bundled in his shoulders. “You can’t trust the pleasure of an Annamese.”

“You know that pleasure well,” mumbled Dai Jai. “At least I don’t pay for it.”

Percival slammed his coffee into the table. The glass shattered. Brown liquid sprayed across the white linen tablecloth, the fruit, the porcelain, and his own bare arm. He stood, and turned his back on his son to face the square, as if it would provide a solution to this conflict. Peasants pushed carts with fish and produce to market. Sinewy cyclo men were perched high like three-wheeled grasshoppers, either waiting for fares or pedalling along, their thin shirts transparent with sweat. Coffee trickled down Percival’s arm, over his wrist, and down his fingers, which he pressed flat on the hot marble of the balustrade. When the coffee reached the smooth stone, it dried immediately, a stain already old.

Percival said, “You are my son.” The pads of his fingers stung with the heat of the stone, his mouth with its words. In the sandbagged observation post between the church and post office, the Republic of Vietnam soldiers rolled up their sleeves and opened their shirts. They lit the day’s first cigarettes. “You must show respect.” Percival turned halfway back towards Dai Jai, and squinted against the shard of light that had just sliced across the balcony. Soon, the balcony’s tiles would scorch bare feet.

Percival noticed a black Ford Galaxie pull off Chong Heng Boulevard, from the direction of Saigon. He considered it. Who was visiting so early? And who was being visited? Dark-coloured cars were something the Americans had brought to Vietnam, thinking them inconspicuous. They had not noticed that almost all of the Citroëns and Peugeots that the French had left behind were white. Now, many Saigon officials had dark cars, tokens of American friendship. Dai Jai stood to see what had caught his father’s attention.

“Where are they going, ba?”

“That is no concern of yours.” It was prudent to take note. But he must not let the boy divert the conversation. The Galaxie turned the corner at the post office, floated past the church, and then pulled up at the door of the school. Two slim Vietnamese in shirtsleeves emerged, wearing identical dark sunglasses. Percival felt his own sweat trickle inside his shirt. That was just the heat, for why should he worry? Everyone who needed to be paid was well taken care of. Mak was fastidious about that. Percival watched them check the address on a manila envelope. Then, one man knocked on the door. They looked around. Before he could step back, they looked up, saw Percival, and gestured, blank-faced. The best thing was to wave in a benignly friendly way. This was exactly what Percival did, and then he sat down, gestured to Dai Jai to do the same.

“Who is it, ba?”

“Unexpected visitors.” Had his friend, police chief Mei, once mentioned the CIA’s preference for Galaxies? Perhaps it had been some other car.

“Are you going down, Father?” asked Dai Jai.

“No.” He would wait for Foong Jie to fetch him. He preferred to take his time with such people. “I am drinking my coffee.”

Percival reached towards the tray and saw the broken pieces of glass. Dai Jai hurried to pour coffee into his own glass, and gave it to his father. A few sips later, feet ascended the stairs, louder than Foong Jie’s soft slippers. Why were the men from Saigon coming up to the family quarters? Why hadn’t Foong Jie directed them to wait? When she appeared, she gave the headmaster a look of apology even as she bowed nervously to the two men who followed her onto the balcony. They shielded their eyes despite their sunglasses. The balcony now glowed with full, searing morning light.

The younger one said, “Percival? Percival Chen?”

“Da.” Yes. Dai Jai stood up quickly, but Percival did not. The two men in sunglasses glanced at the single vacant chair, and remained standing. Now that they were here on his balcony, Percival would do what was needed, but he would not stand while they sat.

“This is the Percival Chen English Academy?” said the older man.

“My school.” Percival waved at Dai Jai to sit.

“We were confused at first—your sign is in Chinese.”

The carved wooden sign above the front door was painted in lucky red, “Chen Hap Sing,” the Chen Trade Company. Chen Kai had made his fortune in the Cholon rice trade and had built this house. He could not have imagined that the high-ceilinged warehouse spaces would one day be well suited for the classrooms of his son’s English school.

“It was my father’s sign. I keep it for luck.”

“Your signature here, Headmaster Chen,” said the younger man from Saigon, offering a receipt for signature and the envelope.

“I will read it later,” said Percival, ignoring the receipt as he took the manila envelope. “Thank you, brothers. I will send it back by courier.” He put it down on the table. They did not budge. “Why should you wait for this? You are important, busy men. Police officers, of course.”

They did not say otherwise. The older man said, “Sign now.” Of course, they were the quiet police. Below the balcony, Percival glimpsed some of the school’s students having their breakfast in the square. Some squatted next to the noodle sellers. Others ate baguette sandwiches as they walked. Percival was relieved to see Teacher Mak coming towards the school. Foong Jie would send Mak up as soon as he arrived.

Percival tore open the envelope, slipped out a document from the Ministry of Education in Saigon, and struggled through the text. He was less fluent in this language than in English, but he could work out the meaning. The special memorandum was addressed to all headmasters, and outlined a new regulation. Vietnamese language instruction must be included in the curriculum of all schools, effective immediately.

“You rich Chinese always have a nice view,” said the older man, looking out over the square. He helped himself to a piece of papaya. Dai Jai offered a napkin, but the officer ignored him and wiped his fingers on the tablecloth.

The younger one thrust the receipt at Percival again. “Sign here. Isn’t that church the one …”

“It is.” Percival peered at the paper and selected an expression of slight confusion, as if he were a little slow. “Thank you, brothers, thank you.” He did not say big brothers, in the manner that one usually spoke to officials and police, or little brothers, as age and position might allow a headmaster. He made a show of re-reading the paper. “But I wonder if there is a mistake in this document coming to me. This is not a school. This is an English academy, and it falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Language Institutes.”

The older one bristled. “There is no mistake. You are on the list.”

“Ah, perhaps the Department of Language Institutes did not review this directive. I would be surprised if Director Phuong has approved this.” Mak must be downstairs by now. Percival could easily delay until he made his way up.

“Director Phuong?” laughed the younger officer.

“My good friend Director Phuong,” smiled Percival. He was Hakka, his name was Fung, though he had come to Vietnam as a child and used the name Phuong. Each New Year, Percival was mindful to provide him with a sufficient gift.

The older one said, “You mean the former director. He recently had an unfortunate accident.”

“He is on sick leave, then? Well, I will take up this matter when he—”

“He will not return.” The older man from Saigon grinned. “Between you and me, some say he gave too many favours to his Chinese friends here in Cholon, but we didn’t come to gossip. We just need your signature.”

Percival stared at the memorandum. He was not reading. Just a little longer, he thought. Now he heard sure steps on the stairs, familiar feet in no hurry. Mak appeared on the balcony, nodded to Percival, who handed the papers to him. Mak glanced at the visitors and began to read the document. The teacher was thin, but compact rather than reedy, a little shorter than Percival. While some small men were twitchy and nervous, Mak moved with the calm of one who had folded all his emotions neatly within himself, his impulses contained and hidden. For years he had worn the same round, wire-rimmed glasses. The metal of the left arm was dull where he now gripped it to adjust the glasses precisely on his nose.

“Brothers,” said Percival, “this is my friend who advises me on all school business.” He continued to face the officers as he said, “Teacher Mak, I suspect this came to me in error, as it applies to schools, but we are a language institute.”

Mak quickly finished reading the papers.

“Headmaster,” said Mak in Vietnamese, “why not let these brothers be on their way?” He looked at Percival. He murmured in Teochow, “Sign. It is the only thing to do.”

Surprised, Percival took the receipt and the pen. Did Mak have nothing else to say? Mak nodded. Percival did as his friend advised, then put the paper on the table and flourished a smug grin at the quiet police, as if he had won. The younger one grabbed the receipt, the older one took a handful of fruit, and they left.

Percival was quiet for a few moments, and then snapped, “Dai Jai, where are your manners?” He tipped his head towards Mak.

“Good morning, honourable Teacher Mak,” Dai Jai said. He did not have his father’s natural way of hiding his displeasure.

Mak nodded in reply.

Dai Jai stood. “Please, teacher, sit.”

Mak took the seat, giving no indication he had noticed Dai Jai’s truculence.

“I had to take Vietnamese citizenship a few years ago, for the sake of my school licence. Now, I am told to teach Vietnamese,” said Percival. “What will these Annamese want next? Will they force me to eat nuoc nam?”

“Hou jeung, things are touchy in Saigon,” said Mak. “There have been more arrests and assassinations than usual. Prime Minister Ky and the American one, Johnson, have announced that they want South Vietnam to be pacified.” He snorted, “They went on a holiday together in Hawaii, like sweethearts, and issued a memo in Honolulu.”

“So everyone is clamping down.”

“On whatever they can find. Showing patriotism, vigour.”

“Hoping to avoid being squeezed themselves.”

“Don’t worry. We will hire a Vietnamese teacher, and satisfy the authorities,” said Mak. “I can teach a few classes.” Though he was of Teochow Chinese descent, Mak was born in central Vietnam and spoke the language fluently. Percival only spoke well enough to direct household servants and restaurant waiters, to dissemble with Saigon officials, and to bed local prostitutes.

“Vietnamese is easy,” said Dai Jai.

“Did anyone ask you?” Percival turned to his son. “You are Chinese, remember? For fifteen hundred years, this was a Chinese province. The Imperial Palace in Hue is a shoddy imitation of the Summer Palace in Beijing. Until the French came, they wrote in Chinese characters.”

“I know, ba, I know.” Dai Jai recited, “Before being conquered by the Han, this was a land of illiterates in mud huts. Without the culture of China, the Vietnamese are nothing but barbarians.”

“That is very old history,” said Mak, glancing around at the other buildings within earshot. “Anyhow, let’s talk about this inside, where it’s cooler.” The sun was already high, and the balcony radiated white heat.

“I will say what I want in my own home. Look, this school is called the Percival Chen English Academy. Students expect to learn English. Why teach Vietnamese here? Why should we Chinese be forced to learn that language?”

From below came the clang of the school bell.

“What are you waiting for?” Percival said. “Don’t you have class? Or are you too busy chasing Annamese skirts?” Dai Jai hurried away, and it was hard for Percival to tell whether the boy’s anger or his relief at being excused caused him to rush down the stairs so quickly.

Mak sighed, “I have to go down to teach.”

“Thank you for telling me about the girl. He must marry a Chinese.”

“I was mostly concerned about the school; your son with a student, the issue of appearances.”

“That too. Get someone else to take your second-period class this morning. We will go to Saigon to address this problem, this new directive.”

“Leave it.”

“No.”

“Why don’t you think about it first, Headmaster?”

“I have decided.” Mak was right, of course. It was easy to hire a Vietnamese teacher—but now Percival felt the imperative of his stubbornness, and the elation of exercising his position.

“I’ll call Mr. Tu. He is discreet. But Chen Pie Sou, remember it is our friends in Saigon who allow us to exist.” Mak used Percival’s Chinese name when he was being most serious.

“And we make it possible for them to drink their cognac, and take foreign holidays. Come on, our gwan hai is worth something, isn’t it?” If the connections were worth their considerable expense, why not use them? Mak shrugged, and slipped out.

Had Percival been too harsh on Dai Jai? Boys had their adventures. But a boy could not understand the heart’s dangers, and Dai Jai was at the age when he might lose himself in love. A good Chinese father must protect his son, spare him the pain of a bad marriage to some Annamese. The same had destroyed Chen Kai, even though she was a second wife. Now, the Vietnamese language threatened to creep into Chen Hap Sing. Looking out over the square, watching the soldiers clean their rifles with slow boredom, he saw it. The events had come together like a pair of omens, this new language directive and Mak’s mention of Dai Jai’s infatuation. Under no circumstance could he allow Vietnamese to be taught in his school. He must be a good example to his son, of being Chinese. Percival went downstairs and found Han Bai, his driver, eating in the kitchen. He told him to buy the usual gifts needed for a visit to Saigon, and to prepare the Peugeot to go to a meeting.

CHAPTER 2 (#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

AS THE SECOND PERIOD BEGAN, PERCIVAL and Mak climbed into the back of the white sedan and sat on the cool, freshly starched seat covers. Han Bai opened the rolling doors of the front room where the car was kept, eased it out of Chen Hap Sing, and set off for Saigon. By the time they crossed the square, the car was sweltering. When Percival had first come to this place, when it was still called Indochina, he had enjoyed this drive from Cholon to Saigon. It wound over a muddy, red earth path alongside market garden plots of greens and herbs, and sometimes flanked the waters of the Arroyo Chinois. It had reminded Percival of Shantou, except for the colour of the soil. Now, they drove on a busy asphalt road, which each year grew more dense and ugly with cinder-block buildings on weedy dirt lots.

Percival said, “I’ve heard that Mr. Tu wants to send his son to France before he is old enough for the draft. He must need money. I’m sure we can avoid this new regulation.” He fingered the wrapped paper package which Han Bai had put on the back seat.

Mak shrugged. “Even if this is possible, it will be a very expensive red packet. It would be cheaper and simpler to hire a Vietnamese teacher. You won’t have to pay nearly what you pay your English teachers.”

“Let’s see what price he names.” Percival looked out the window as they sped past a lonely patch of aubergines. Since the Americans had come, the main things sprouting on this road were laundries and go-go bars. It was a short drive now, the six kilometres covered in half the time it had once taken.

Mr. Tu’s office was in a back hallway of the Ministry of Education. In black letters on a frosted glass insert, the door was stencilled, SECOND ADJUNCT CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER OF THE DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE INSTITUTES.

Percival knocked on the door. “Two humble teachers from Cholon have come to pay their respects,” he said, in a tone that could have been self-mocking.

Mr. Tu answered the door and shook their hands vigorously in the American manner. He made a show of calling Percival “headmaster,” hou jeung, and held the door. Mr. Tu was the type of Saigon bureaucrat who had a very long title for a position whose function could not be discerned from the title alone. He regularly helped people to sort out “paper issues.” He guided his guests to the chairs in front of his desk, and beamed. Yes, Percival concluded, Mr. Tu was clearly in need of funds. Behind him was a framed photo of an official, looking out at Mak and Percival, his mouth set with determination against the glass of the frame.

“Isn’t that the new minister of …?” said Percival, as if he might remember the name. “He is the brother of …”

Mr. Tu laughed, saying, “Hou jeung, I could say it was our new president, and you would believe me.”

“You’re right. But I take an interest when I have an interest.” Percival grinned, and settled into the worn green vinyl upholstery, which had endured in this office through countless changes of the portrait on the wall. Percival told Mr. Tu of the breakfast visit at his school. He said nothing of his personal wish to avoid teaching Vietnamese. Despite being a practical man, Mr. Tu might be patriotic. Instead, in plodding Vietnamese, Percival explained his reluctance to add another teacher to the payroll. “It’s just one salary, but once you employ a man, he must be paid forever. He expects a bonus at Tet, and a gift when he has a child. If his parents become ill, he’ll need money for the hospital. So I wonder … if this new regulation might exempt an English academy, say, with a generously minded headmaster. You know I don’t mind spending a little if it helps me in the long run.”

Mr. Tu cleared his throat. He slowly spread his fingers as if they had been stuck together for a long time. Had there been the twitch of a frown, though quickly erased by the expected smile? He said, “I sympathize. Deeply. Absolutely. It is so unfortunate that an unimportant person like myself can do nothing about this issue.”

Invariably, Mr. Tu’s first response to any request was to profess his simultaneous desire and inability to help. Percival placed the wrapped paper package on Mr. Tu’s desk. He said, “It may be that language institutes such as the Percival Chen English Academy fall outside the parameters of this new regulation. There may have been a simple administrative mistake. If so, I wonder about an administrative solution. After all, I run an English academy. It’s not a regular school.”

Mr. Tu opened the package, and thanked Percival for the carton of Marlboros and the bottle of Hine cognac. “The issue of Vietnamese instruction in the Chinese quarter—in Cholon—is … how can I say … important to some,” he said. “It may be difficult to make exceptions.” This type of response was also typical, in order to justify a price. But Mr. Tu looked genuinely uncomfortable, which was unusual.

“Please understand,” interjected Mak. “The headmaster thinks only of the pressing need to educate English-speakers who will help us help the Americans.”

“Surely, the Ministry of Education would not wish to diminish English instruction time when all of our students already speak Vietnamese,” said Percival. Of course, many of the students at the Percival Chen English Academy were in fact of Chinese descent and spoke only basic Vietnamese, like their headmaster.

“We have the utmost of patriotic motivations,” said Mak. “The American officers whom I know often tell me that they need—”

“No doubt,” said Mr. Tu. “What is your tuition now?”

“I would have to check,” Percival countered, anticipating price negotiations.

Mr. Tu rubbed the amber bottle with his palm, and placed it, along with the cigarettes, in his desk drawer. From his bookshelf, he plucked a bottle of Otard, and poured three glasses. Lifting his glass to his lips, Percival smelled and then tasted a cheap local liquor rather than the promised cognac. Mr. Tu said with a casual shrug, “I will make inquiries. Further conversations might be required, with my chief, and possibly above him.” Mr. Tu looked down. “So you should ask yourself, are such conversations worthwhile? This is not an easy matter.”

“But what would make it easy?” said Percival, undeterred, preparing already to balk at a price and counter with half.

“Hard to say.”

“Roughly.”

“I don’t know the price,” said Mr. Tu.

“Your best guess.” It was better to get a number to start the discussion rather than leave empty-handed.

“Or even if it is possible,” said Mr. Tu, and stood. “I am a humble fonctionnaire. It may be beyond me. As men of learning, you know that some answers are more complex than others.”

“I see,” said Percival. This did not seem like mere negotiation of price.

“That is our new ministerial advisor,” said Mr. Tu, indicating the new photo. “Thuc is below the minister in theory, and above him in reality. He is very patriotic. Prime Minister Ky chose him personally to oversee education.” He tapped the arms of the chair and looked from Percival to Mak.

Mak stood, smiled graciously, and said, “Thank you, Mr. Tu, for your time.” He leaned towards the desk and said, “If there is no solution to be found, there is no need to remember that we asked.”

Mr. Tu nodded. “Don’t worry. It would serve no one.”

Percival stood, and they left, closing the door themselves as they went into the hallway.

As Han Bai drove them back along the road to Cholon, which was now quiet near midday, Percival said to Mak, “You had nothing else to push him with? Some favour he owes us?”

Mak turned to face Percival. “To what end? Mr. Tu spoke clearly—this policy is a patriotic and political issue. You know that some in Saigon dislike the Chinese-run English schools in Cholon.”

“Because our graduates get the American jobs.”

“That ministerial advisor is Colonel Thuc. He was just transferred from the Ministry of Security and Intelligence.”

“I suppose that was why those quiet police were delivering educational directives.”

“It may prove unwise to attract attention over this issue, hou jeung.”

For the rest of the trip home, they sat in thick silence. What else could Percival say, when Mak’s judgment was always sound? He always knew what had become important of late in Saigon.

By the time they returned to Chen Hap Sing, the morning students were gone, and the afternoon students had begun their lessons. Dai Jai had left for his Chinese classes at the Teochow Clan School. Percival went to his ground-floor office, cooler than the family quarters at this time of day. On his chair, Foong Jie had hung a fresh shirt for the afternoon. On the desk, she had put out a lunch of cold rice paper rolls and mango salad. He shut the door, ate, removed his crumpled shirt, tossed it on the seat of the chair, and laid himself down for his siesta on the canvas cot next to his desk.

As Percival’s breathing slowed, the blades of the electric ceiling fan hushed softly through stale air. On each turn, the dry joint of the fan squeaked. The fan had been this way for a long time, and Percival had never attempted to lubricate it, for he liked to be tethered to the afternoon. Only half-submerged beneath midday heat, he was not bothered by dreams. After some time, he heard a thumping. At first, he ignored it and rolled to face the wall. The noise continued, and then a voice called, “Headmaster!” It was Mak.

Percival propped himself up on an elbow, his singlet a second skin of sweat, his eyes suddenly full of the room—the grey metal desk, the black telephone. A gecko at the far upper corner of the room looked straight into Percival’s eyes, limbs flexed.

“Hou jeung!” A fist on the door.

“Come in, Mak.”

Mak entered, shut the door, and stood by the cot for a moment, as if he found himself a little wary of actually speaking.

“Please, friend. What is it?”

“I have heard something worrisome,” Mak said. “Chen Pie Sou, it is something that your son, Dai Jai, has done.”

“Involving the girl?” said Percival, angry already. Had Dai Jai defied him further?

“No.”

Mak explained that at the start of the afternoon class at the Teochow Clan School, when Teacher Lai had announced that she would begin the newly mandated Vietnamese lesson, Dai Jai stood up and declared that as a proud Chinese, he refused to participate. Mak said, “Dai Jai’s classmates joined him in this protest. Each student rose, until the entire class stood together. Then, Dai Jai began to hum ‘On Songhua River,’ and others joined in. Mrs. Lai was frantic, but they wouldn’t stop.”

“How does Dai Jai even know that old tune?”

“Finally, he walked out, and the class followed him.”

“Where is the boy now?” Percival rubbed his eyes.

“I haven’t seen him,” said Mak. Then, speaking deliberately he added, “I got all this from Mr. Tu. In Saigon. He has heard of it already, and wished to warn you. They have eyes in all the schools.”

Percival stared at his friend. He had heard and understood Mak immediately, all too well. The delay was in knowing what to say, to do. If Mr. Tu knew, then someone at the Ministry of Education was already writing a report.

“Mak, you know what happens in Saigon these days. Tell me, are they making arrests at night or in the day?” During the Japanese occupation, the Kempeitai preferred to seize people at night and behead them during the day in public view. Before and after the Japanese interlude, the French Sûreté usually made arrests during the early part of the day. The bleeding, bruised person would be left on the street late in the afternoon if a single interrogation was sufficient, so that the officers could make it for cocktails at the Continental patio. If more was required of the prisoner, he or she would disappear for months, years, or would never be seen again. Now, the Viet Cong liked to work at night. They crept into Cholon across the iron bridge from Sum Guy and would kidnap someone for ransom, or lob a grenade into a GI bar before disappearing into shadows. Percival found that he could not think of the habits of the Saigon intelligence.

“They make arrests whenever they feel like it,” said Mak quietly.

“Where is Dai Jai?” said Percival, his voice pitched high. “They can’t have found him so quickly.”

“You don’t think so?” Mak caught himself. “No. Of course not.”

Rays of light pierced the small gaps in the metal shutters. Dots and slashes. Percival struggled to pull on his fresh afternoon shirt, the starch sticking to his skin.

“We will have to hire a Vietnamese teacher immediately,” said Percival.

“Clearly,” said Mak.

Percival was about to go look for Dai Jai himself, but Mak suggested that he stay at the school. If the quiet police visited, the headmaster should be there to deal with it. Percival sent the kitchen boys out to help Mak look for Dai Jai, not telling them why. He stood at the front door, scanning the square for either his son or a dark Ford. He stalked his office, glared at the phone. Finally, late in the afternoon, Percival heard one of the kitchen boys chatting amiably with his son in the street, both of them joking in Vietnamese. Percival heard the metal gate clang, then whistling in the hallway. His relief gave way to anger as he shouted to summon the boy. Dai Jai came to the door. “What is it, ba?”

Percival rose from his chair. “What were you thinking today at the Teochow school?”

“Are people already talking about our protest?” He stood in the doorway, excited, his white school shirt soaked through with sweat.

“Protest. Is that what you call this stupidity?”

“Ba,” he said, his eyes wide. “You said yourself this morning that the Chinese should not be forced to study Vietnamese.”

“Did I raise a fool?”

Dai Jai’s voice fell. “I thought you would be proud.”

“For bringing trouble? I heard of your … theatre from people in Saigon. Do you understand?”

“Good,” he puffed up. “They know that the Chinese will not be pushed around, yes, ba?”

Percival’s mouth felt numb as he said in a softer voice, “Son, if you wish to do something, it is often best to give the appearance that you have done nothing at all.”

The last of Dai Jai’s proud stance withered. “But I did it to please you,” he said.

“I see.” Percival slumped into his chair, the anger flushed out by guilt and fear. His hand went to his temple. “No matter, your father is well connected. I will fix it.”

That night, Percival and Dai Jai ate together as usual in the second-floor sitting room. The cook made a simple dinner of Cantonese fried rice. As they were eating, there was a knock at the front door. From downstairs came the shuffle of Foong Jie’s feet. Percival could hear the nasal tones of Vietnamese words, a man’s voice, but he could not make out what was being said. Downstairs, the metal gates clanged shut. Foong Jie appeared with a manila envelope. She was alone.

Percival exhaled.

She handed Percival the envelope and slipped out. With sweaty, shaking hands, he ripped it open.

“What is it, ba?”

Percival waved the letter at Dai Jai. “A note from your mother,” he said. “She has heard about your … incident. She wants me to meet her tomorrow in Saigon.”

The boy picked up his bowl and resumed eating. After a while, Dai Jai broke the silence with laughter, still holding his bowl, almost choking on his food. He swallowed and wiped tears from his eyes. “You thought—” and he was again seized with uneasy laughter. “Well, it was not the police, just a note from Mother.”

“This is nothing to laugh about!” said Percival. He pushed away his half-eaten dinner. He stood and turned on the radio. After a hiss and pop, the Saigon broadcast of Voice of America was recounting the day’s news, informing listeners that the Americans had bombed oil depots in Hanoi and Haiphong, that the French president, De Gaulle, had announced he would visit Cambodia in September, and that Buddhists in Hue and Da Nang were protesting against Prime Minister Ky’s military government.

Percival’s spirits lifted. Were the monks setting themselves alight once again? He had often remarked that he couldn’t understand these bonzes—they killed themselves to criticize the government, but surely the government must be glad that some of their critics were dead. After news of an immolation, Percival was always relieved to see the one-eyed monk in the square, for he was fond of that one, who seemed to have the intensity that a martyr would require. The suicides by fire attracted a great deal of attention, though, so now Percival listened with hope. Surely, those in Saigon who watched for dissent would take more interest in a new spate of Buddhist trouble than in some trivial incident at a Chinese school in Cholon. Percival turned to Dai Jai. “I will meet with your mother tomorrow. Do you see how serious this is?”

“I’m sorry, Father. I thought it would make you proud.”

What to say, that he might have been, if the incident had remained Cholon gossip rather than Saigon trouble? But even if that had been the case, he would have had to instruct the boy nonetheless, that he must learn to pair his best impulses with canny quiet. Percival said, “I will fix this. Until then, you cannot leave Chen Hap Sing.”

“I need to go out tonight. I need—”

“No!”

“Ba, I have to buy larvae for my fish. They need to eat every day.”

Percival was tempted to ask whether Dai Jai was planning to buy fish food from a pretty Annamese fellow student, but that didn’t seem so important now. “Someone might be outside, waiting to arrest you. I will send one of the servants for your larvae.”

Later that evening, Percival went out on the second-floor balcony where Dai Jai kept his tanks. The boy made no acknowledgement of his father’s appearance, but continued to skim the water clear with a flat net. Yes, for the boy to be so moody about staying in, it must have been a rendezvous with the girl. Ever since he was very small, Dai Jai had nurtured gouramis and goldfish, kissing fish and fighting fish. In recent years Dai Jai had renounced most of his childhood toys and games in favour of soccer with his friends, stolen cigarettes, and a French lingerie catalogue that one of the sweepers had found hidden in his room, and which Percival had directed be placed back exactly where it was found with nothing more to be said about it. The one fascination that persisted from boyhood was the fish.

Percival held out two lotus-leaf cones of live mosquito larvae in water. “For you, Son.” He had gone out himself to buy them, but did not say so. This was the hour that the casinos were becoming busy and filled with people he knew, but Percival had no urge to gamble tonight. He must stay close by, in case something happened.

Dai Jai took the cones with quiet thanks, and gently tore off a corner to let the fluid out. He began to pour the food into each tank. The fish darted amongst the water plants to take their meal. Dai Jai went from one tank to another, feeding the fish until the whole row of tanks was a shimmering display.

“How do you know the song ‘On Songhua River’?” asked Percival. Why would the boy know that old tune of the Chinese resistance against Japan’s occupation? It was not a modern melody.

“You often hum it.”

That was what Percival had thought. “What you did was foolish, but I appreciate the spirit in it.”

Dai Jai put down the net. “Father, you always say that wherever we Chinese go in the world, we must remain Chinese.” The words Percival had spoken many times now rang back in echo. Beneath the sky’s thick gloom, points of light appeared in the square below. The first lamps on the night vendors’ carts were being lit, their flames dancing and spitting briefly until they were trimmed into a steady light. People emerged from their houses, chatted happily and walked with new energy in the cool hour.

“Son, a man can think without acting, or act without being seen. A son should be dutiful. Not reckless.”

“Yes, Father.”

“We are wa kiu.” They were overseas Chinese, those who had wandered far from home. “We are safer when we remain quiet.” The lamps in the square glowed into brightness—one after another. It happened quickly, as if each lamp lit the next. Cholon was most alive, sparkling with energy, in the early evening. Dai Jai’s fish pierced the water’s surface and took the tiny larvae into their mouths, leaving behind rippled circles. “Until I have dealt with the problems you have caused, don’t leave the house anymore. Don’t go to the cinema or the market. Don’t go to the Teochow school. Don’t even attend school here. Be invisible.”

“Yes, Father.”

“If there are visitors from Saigon, hide yourself well, but stay in the house. You are safer here.” The old house had many dark hallways and secret nooks. It was the house that Chen Kai had built. It would be safe.

CHAPTER 3 (#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

AT THE CERCLE SPORTIF, HAN BAI pulled up in the circular drive fronting the club’s entrance, stopped the car beneath the frangipani, and went around to Percival’s door. The headmaster was not in the habit of waiting for his driver to attend to him, and in most places he would simply open the door himself and step out of the car. However, at the club, Han Bai knew that the headmaster waited for his driver.

Percival ascended the canopied stone steps, nodded to the bows of the doormen, went through the clubhouse, and out to the pavilion that looked over the tennis courts. Since their divorce eight years earlier, this was where he and Cecilia met to talk. The roof of the pavilion was draped with bougainvillea, which reminded Percival of Cecilia’s old family house in Hong Kong.

A waiter pulled out a chair, his jacket already dark in the armpits. At nine in the morning, one game of tennis was under way. The Saigonese and the few French who remained from the old days played before breakfast, but some Americans were foolish enough to play at this hour. Cecilia was on the court in a pleated white skirt, playing one of the surgeons from the U.S. Army Station Hospital in Saigon. She had always cursed the city’s climate, but now did most of her money-changing business with Americans so played tennis when they did. She displayed no feminine restraint as she lunged across the court to return a serve. The surgeon had his eye more on his opponent than the white ball, and Percival could not help feeling the familiar desire.

“For you, Headmaster Chen?” said the waiter.

“Lemonade.”

“Three glasses?”

“Two.”

How typical of Cecilia, to arrange a game of tennis with an attractive foreign man when she had asked Percival to meet her at the club. In reply, he stared in the other direction. There was no way to turn his ears from the players’ breathy grunts, quick steps, and the twang of the ball ringing across the lawn.

Cecilia had played tennis since she was a child in Hong Kong, years before Percival ever saw a racquet. Her name had been Sai Ming until she was registered by the nuns at St. Paul Academy as Cecilia, and thereafter eschewed her Chinese name. When they had been students, he at La Salle Academy, and she at its sister school, St. Paul, she once offered to teach Percival how to play. He was even more clumsy with a racquet than he was on the dance floor. Cecilia had laughed at his ineptness, and Percival declared tennis a game of the white devils.

Percival had come to Hong Kong in the autumn of 1940, just a few months after a fever had ravaged Shantou. During that contagion, Muy Fa became hot, then delirious. Despite the congee that he spooned between his mother’s cracked lips, and Dr. Yee’s cupping, coin-rubbing, and moxibustion, one morning Muy Fa lay cold and still on the kang. The years of his father’s absence had put coins in the family money box, but now the silver seemed cold and dead to Chen Pie Sou. It had paid for a doctor, but not saved his mother. There was no question of a Western-trained doctor or medicines, for the Japanese occupation of Guangdong province was two long years old. Chen Pie Sou sent both a telegram and a formal letter of mourning to his father in Indochina, and paid ten silver pieces for it to go by airplane. An exorbitant sum, but his mother deserved every honour. He was shocked to receive a brief telegram from Chen Kai indicating that business matters and the dangers of the war prevented him from returning to mourn in Shantou, that he would pray for his deceased wife in Cholon, and asking his son to go ahead with the burial rites, though sparing extravagance. Soon after the funeral, a letter from Chen Kai informed his son that he would be sent to Hong Kong for a British education. Chen Pie Sou wrote back dutifully, saying nothing of his anger at his father’s failure to return, nor his disappointment at not being asked to join him. As most of the family’s cash savings was used for the funeral, Chen Kai made arrangements through a Shantou money trader for a sum of Qing silver coins to be provided for his son’s needs in Hong Kong. A forged French laissez-passer was smuggled to him, along with a letter of registration from La Salle Academy. These documents would allow Chen Pie Sou to leave the Japanese-controlled territory and enter Hong Kong for his studies.

Intending to dislike Hong Kong on account of the way he was sent there, Chen Pie Sou soon began to think that it was not so bad. The priests and nuns gave him a new name, Percival. People in the colony lived in an energetic jumble one on top of another, the streets filled with constant shouting and scrambling to buy and sell. The tall apartment buildings, he was told, were a Western invention. Afraid to live in such a towering structure of dubious origins, Percival took a tiny neat room in an old rooming house owned by a Cantonese woman, Mrs. Au. At first, it was frightening for him to be in the streets, to see the ghostly white British masters who rolled past in carriages that sputtered along without horses, or to be confronted at a street corner by the terrifying beard of a Sikh policeman. What weapons might they carry in their gigantic turbans if they wore curved knives on their belts? However, the tumult was soon energizing. From the street vendors, Percival bought dishes that he had never known existed. At La Salle, English came easily to him. Why did some boys complain that it was difficult, when there were only twenty-six letters? Percival was soon tutoring slower classmates and had a few extra coins for the cinema. And the girls! They were a different species than those in Shantou.

By the time Percival became captivated by the perfect arc of Cecilia’s neck, and by the slight pout which rested naturally upon her lips, she was already going out of her way to defy the introductions that her mother, Sai Tai, coordinated. Wealthy Hong Kong society offered its suitors by the handful to the heiress of the colony’s biggest Chinese-owned shipping fleet. One after another, Cecilia declared them unsuitable. One boy had bad skin, another was too pretty. One did not have enough money, and another bragged tiresomely about his family’s wealth. Also, she complained, that last one drove his car too slowly.

Percival heard all this by eavesdropping on Cecilia’s gossip with her girlfriends. He didn’t stand a chance, he concluded, but that didn’t keep his thoughts from being frequently invaded by Cecilia. She was unlike any girl he had ever encountered. She used none of the suppressed giggles or blushing avoidance of other girls her age. Cecilia entered movie theatres alone, people whispered. She was spotted at the betting window of the Happy Valley racetrack. She made wagers on new, unknown horses and won. Some of the less affluent students at St. Paul tut-tutted that Cecilia’s behaviour was disgraceful, and whispered with smug reproach that great wealth did not buy proper behaviour. Boys either found her strangely threatening or desired her with intensity, as Percival did.

Once, when he was trailing her longingly, she turned suddenly and stared straight at him. She fixed his eyes immediately. How could he have known, at that naive age, that these were the eyes of a cat who had found its mouse? He became hot, flushed. She was ivory-skinned perfection, her lips pursed. Then she tilted her nose up slightly and turned slowly away, so that Percival tortured himself for days afterwards, trying to decide whether she had been amused or offended by his interest.

At Christmas, the chaperoned school dance for the girls of St. Paul and the boys of La Salle was held in a respectable banquet hall on Queen’s Road. As the band began to play the easy three-beat rhythm of a waltz under the watchful eyes of the priests and nuns, Percival finally managed to summon the courage to approach Cecilia, resplendent in a peony-patterned gown. He crossed the now vast dance floor and managed to get out the words he had rehearsed. “I am Chen Pie Sou, will you dance with me?”

“Didn’t the priests give you an English name?” she replied. After a moment, she rescued him from his stunned inability to speak. She said, “Percival, isn’t it?” She lifted his chin with a fingertip, the shock of her touch coursing through to his toes. Before he could say anything else, she had his hands and was leading him gaily in the waltz. When the dance was finished, he felt both abandoned and relieved to watch her flit into the distance again. After that, Percival could think only of Cecilia. Her image threatened to crowd out his studies. In front of his desk, he tacked up the letters from his father, formulaic correspondence exhorting him to study. Percival’s dreams of Cecilia fulfilled him during sleep, and shamed him when he woke, his underwear stained.

The remittances from Chen Kai had been enough to make Muy Fa and Chen Pie Sou wealthy in Shantou, but once he went to Hong Kong and became Percival, he heard the snickers of his more cosmopolitan classmates. Percival had two school uniforms, which he washed by hand and hung to dry in the tiny room he had rented. His father had written shortly after his arrival in Hong Kong, warning that he must make the small sum of silver last through the school year. That was a surprise, but Percival had not complained. The suitors whom Cecilia had already rejected were heirs to property, and wore uniforms carefully pressed by their servants, but for some reason Cecilia began to seek out the boy from Shantou. She would sit with him at lunch. When he offered to walk her home, saying he was going in the same direction, though this was an obvious lie, she accepted.

They went to the movies, and held hands. Percival worried that someone might see them, but Cecilia conspicuously rested her head on his shoulder. She took her family’s Austin Seven and taught him to drive on the twisting lanes of Victoria Peak, urging him to go faster despite the absence of guardrails. Sitting high above Hong Kong’s craggy coast, they watched the Peak Tram shunt forever up and down.

Cecilia said one day, “Can you keep a secret?”

“Anything.”

“I will see the world. Soon, I will sail abroad. I will meet famous people in important places.”

Percival dared not betray his ignorance by asking exactly where these places or whom these people were. He said, “Yes, you can go anywhere. Your family’s ships can take you.” One of their coal barges was cutting slowly across the bay beneath their feet.

“You are silly,” she said, but added kindly, “and sweet. My family’s ships only sail the South China Sea. I think I will sail on one of the Messageries Maritimes steamers—those are the most handsome. The suites have silk drapes.”

“Maybe I will—” he stopped to unstick the words from his throat, “go with you.”

Without a word, she took his hands in hers, as one might console a child. From then on, whenever they sat up high on the Peak, Cecilia told Percival of the places she would visit—Westminster Abbey, the Louvre, the Grand Canyon. Her family owned books, she said, with photographic plates of all these wonders. While she talked, with her eyes on the water, Kowloon beyond, she allowed him to touch her. He stroked her palms, kissed the backs of her hands, massaged her fingers. He explored her perfect forearms. Percival heard his own breath, heavy, as she asked him if he knew of this monument or that museum. In a damp sea wind, he brushed the goosebumps that rose on her skin. Cecilia allowed him to be as passionate as he liked, but stopped him at the elbow.

As a young man of half-decent though backwater origins, Percival was occasionally invited to the same banquets as Cecilia, mostly to occupy an odd single seat at one of the banquet tables. Cecilia never bothered about where she was supposed to be seated, and seemed to enjoy making a minor fuss disrupting the arrangements and sitting next to Percival instead. As pleased as he was by Cecilia’s attention, Percival could always feel the wave of Sai Tai’s anger pulsing at him from across the room. Cecilia’s satisfaction was just as palpable. It was disrespectful to snub an elder, but Percival’s wish to please Cecilia was stronger than his desire to uphold decorum, and besides, Percival told himself, it was Cecilia who was angering her mother. While the quiet of their time alone was what he longed for, Cecilia seemed to relish being in public, flaunting her unsuitable paramour, so much so that it seemed to Percival that she almost forgot him in her efforts to display him. She never introduced Percival to her mother.

In the autumn of 1941, a schoolmate of Percival’s asked him if the rumours were true. Cecilia, the friend said excitedly, had revealed in strictest confidence to a number of friends that she might marry the poor country boy Percival. It was the talk of the school. She and Percival had never discussed marriage. Percival assumed an offended air and told his chum that no gentleman would answer such an indiscreet question. He did not mention the rumour of their impending marriage to Cecilia. He was both afraid to open himself to her mockery, and worried that trying to clarify this rumour might cause its tantalizing possibility to vanish.

AS HE SIPPED HIS LEMONADE, PERCIVAL watched now as Cecilia served the ball to the American surgeon. A flick of her wrist, and the ball spun. Sure enough, her gangly opponent was caught off guard on the bounce. She called out, “Fifteen … love,” to the American, but as she turned she shot her triumphant glance at Percival. Of course, he realized with annoyance at himself, as usual he’d been unable to resist looking at her.

The Japanese invaded Hong Kong in December 1941, and by overrunning it in eighteen days demonstrated that it was not the impregnable fortress that the British had promised. Some La Salle students volunteered as orderlies at St. Stephen’s Hospital, and only one returned. He told Percival that the Japanese had shot the doctors, tortured the patients, violated the nurses, and burned the hospital down. The school Christmas dance was cancelled, and the British surrendered on Christmas Day. Though some of Percival’s friends asked him to join them when they stole into the hills to fight with the Gangjiu resistance, Percival stayed in his room, grateful that his landlady had such heavy furniture with which to barricade the door. All the tenants were hungry and sleepless, for around the clock the shots of executions punctuated the wailing of the girls and women being raped.

When the noise of violence had exhausted itself after a few days, Percival ventured out to try to find some food. White, yellow, and brown soldiers of the British Army swung from the lampposts, their bodies already swollen, discoloured. Those who still lived were being marched away barefoot by the Japanese, many of whom now wore good English boots. For the first time ever, Percival knocked on the door of Sai Tai’s grand garden house on Des Voeux Road. He didn’t know what he would say, but he wanted to see Cecilia, to know that she was safe. In reply to his knock, there was only terrible silence. Finally, a neighbour appeared, implored him to stop banging lest it attract the attention of the Japanese, and informed him that Madame Sai and her daughter had gone. They had abandoned their house for a rented apartment on the sixth floor of a plain building. Sai Tai, the neighbour said, hoped that after climbing so many stairs, a Japanese soldier would not have the energy to violate her daughter. The neighbour did not know the address of the apartment where they had fled.

La Salle and St. Paul were both commandeered by the Japanese, so there were no more classes to attend. The Kempeitai, military police, arrested and punished suspected members of the Gangjiu with great efficiency, the flash of a sword by the side of the street. Bystanders were commanded to watch. The head was speared on a fencepost, if convenient. Hunger, both of people and beasts, made the days long. One day, as he searched for a shop that had food to sell, Percival saw a pack of dogs ripping with mad pleasure a hunk of meat, perhaps a piece of dead horse or donkey? Normally, he would not think of eating such meat. Now, he wondered how he could distract the dogs or scare them off long enough to grab it. Then he saw the man’s body several feet away, clothes ripped open, the stump of neck. The head was nowhere in sight, other dogs must have carried it off already. Sai Tai’s handsome garden house was soon taken over by General Takashi, so it was best that it was empty when he came to seize it.

Percival was lucky that he still had a few of the silver coins his father had provided, and with these he barely managed to feed himself. In late spring, as deaths from starvation became common, the Japanese declared that those with foreign papers could apply for exit permits. Percival had the French laissez-passer he’d used to enter Hong Kong. He learned that the freighter Asama Maru would sail for Saigon in two weeks, and some said that things were better in Indochina. Percival used the last of the Qing coins to pay the bribe for an exit permit, and to purchase a ticket on the boat. All he had left was the family charm, the reassuring lump around his neck, which he was careful to keep out of sight lest he be killed for it by a Kempeitai. Down by the docks, Percival recognized a number of Cecilia’s family’s ships, which had been seized by the Imperial Navy. They were being repainted in military grey and branded with the Rising Sun insignia. Percival had not seen Cecilia since the invasion. He thought about her often, but Sai Tai was keeping her well hidden.

A week before Percival’s ship was due to sail, a woman in peasant dress approached Percival on the street. Sai Tai had sent her maid to summon him. The next day Percival found the apartment building, climbed the stairs, and at the precise time he had been commanded to appear knocked on a green wooden door. The door swung open. Percival was startled to see Cecilia’s mother rather than her servant standing before him. She wore a formal silk robe that was incongruous with the modest apartment.

“You are …?” she asked, as if she did not know. As if she had not summoned him. The matriarch fixed him with her narrow eyes, dared him to speak. He was frozen, as terrified as if she were a Japanese officer.

“Is something wrong with your legs?” she said. “Come in. Close the door.”

Percival did as instructed.

Sai Tai glided across the room, her feet hidden by generous silk folds. She came to a rosewood chair, its wood so dark that the chair emerged from shadow only when she lowered herself regally into its arms. Percival followed meekly, unsure how close to approach, erring on the side of being a little far away.

“Are you a mute?” she said. “Introduce yourself.”

“I am called Chen Pie Sou,” said Percival, guessing that she cared more about his Chinese name. “It is a great honour to meet you, madam.” He stepped forward and bowed his head.

“I wish I could say the same.” She sat intensely straight, as if sitting in such company required immense effort. “Understand that I wanted my daughter to marry someone suitable to her family’s stature.”

“Naturally, madam.”

“My maid tells me your family is in the rice trade.”

“Yes, madam.”

“However, I have never done business with them. They must not be very important.” As she leaned forward, her jade bracelets clicked against the arms of the chair.

“I’m sure you are correct, madam,” said Percival.

“But people always need rice. At least you are not completely worthless.”

“We have a house in Indochina, which my father built. It is—”

“Your family has a house?” she barked. “You think this is worth mentioning? Then you are very nearly worthless.”

“Yes, madam.” Percival went down on one knee, his heart pounding, and imagined his head being lopped off.

“Get up!” He reminded himself that it was Japanese soldiers who decapitated their prisoners. Wealthy old women with jade-heavy arms were not known to do this. “Is my daughter running around with a totally spineless wretch?” Percival scrambled to his feet. “You are not bad-looking,” she said.

“Thank you, madam.”

“Good-looking men are indiscreet. They cannot be trusted.”

“Yes, madam.”

“So you agree. You are not trustworthy?”

“Not at all. I mean, no. I don’t agree. No, no, in fact, I am not very good-looking. That’s what I mean.”

Sai Tai sat back a little. “At least you make an effort to show some respect. Unlike my daughter. I am told that you have a French laissez-passer and an exit permit from Hong Kong. I’ve heard you have a cabin on the Asama Maru, and will soon be leaving for your home in Indochina?”

“Yes, madam.” He could barely utter these words, never mind being able to clarify matters. It made no difference, he thought, that he had never been to Indochina. His papers said that he was a resident of that country.

“I am told that the French and the Japanese have some kind of deal, that it dampens the bestial behaviour of the Japanese in Indochina. They say this year’s rice crop was good in Annam, and no one goes hungry, despite the Japanese occupation. Is this true?”

“I have heard the same,” he said.

“Your household must have stores of rice?” Only then, he noticed that her cheeks were less haughty than he had seen them before, perhaps a little hollow? Did even Sai Tai, he wondered, feel the hunger of the occupation? “You have the means to care for my daughter?”

Years before, along with peppercorns, cinnamon, nutmeg, and brandy, Chen Kai had brought with him on a visit to Shantou a photo of the house he had built in Cholon. It was six storefronts wide, and three floors high. Within, Chen Kai explained, were high-ceilinged warehouse rooms for fresh paddy and threshed rice. There was no building so spacious and grand in Shantou, he declared. Chen Pie Sou had resented his father’s taking of a second wife. Muy Fa had stared at the photo of Ba Hai in front of the house, and criticized the building’s extravagant size, saying nothing of her husband’s Annamese wife. Ba Hai was a small-boned, dark-skinned foreigner wearing Chinese clothes in the photo. As a boy, Chen Pie Sou swallowed his question; why, if his father had found enough gold to build a house like that and take a second wife, had he not returned to Shantou? But now, confronted by Sai Tai’s questions, Percival was glad to think that even Cecilia would admit that his family house was a decent size. “Yes,” he said, with a small burst of confidence. “My family has ample means to care for your daughter. Our house is large. Our warehouses are full of rice.” This last must be true, he reasoned, as his father was a rice trader.

“Then take my daughter with you to Indochina. Better that she escape with you, though almost worthless, than stay here and be devoured by Japanese dogs. Remember, I am choosing you as an option preferable to dogs. Come tomorrow at the same time for your wedding.” She waved him off, not moving from her carved chair.

Trembling, he backed away in stumbling bows, and fled down the stairs. That was how the couple became engaged. Cecilia’s mother did not offer her daughter’s hand. She commanded Percival to take it. As he left the apartment, Percival rejoiced at his good fortune—that the very rubble and stink that he was picking his way through had led to his engagement with the girl he longed for. The next day, they were married in the sixth-floor apartment by one of the La Salle priests who had somehow survived the Japanese invasion. Cecilia wore the cheongsam in which Sai Tai had once been married, and glared at her mother through the whole ceremony.

A few days later, standing on the deck of the Asama Maru in formal dress, the newlywed couple waved goodbye to Sai Tai, who sat in a canopied rickshaw on the dock. As Hong Kong retreated across the choppy water, Cecilia said, “I dreamt of Paris, or London, but I have married a country bumpkin who is dragging me into the Indochina mud.”

“But you spread the rumour that we wished to marry—”

“Were you stupid enough to believe that I would actually want to marry you?” She whirled away from him. “I fooled with you precisely because it was inconceivable that I could ever marry so beneath me. I did it to keep my mother’s suitors away. If it wasn’t for the war, she would have agreed by now to send me to England or America—in order to get me away from you!” She stalked towards the companionway, and shouted across the deck, “Now see what I’m stuck with!” She disappeared below. Percival looked around, saw the other passengers turn away.

As they reached open water, Percival clenched the rail at the edge of the deck, fighting down a sick feeling. The shallow-bottomed freighter began to roll. Had Sai Tai plotted a double victory, calling Cecilia’s bluff and forcing the marriage to show her control of her daughter as well as send her to safety? He stood, unbalanced by the sea, as flecks of black soot drifted from the smoky stack and ruined his one decent white suit.

When Percival made his way unsteadily down below deck, lurching against the growing motion of the boat, he did not know what he would say or do. He appeared in the doorway of their cabin. He spoke from instinct. “Cecilia, we’re married now.”

“Look at your suit. What a mess.”

“Isn’t there something special between us? What about when we were up at the Peak, holding hands and talking.”

“A worthless muddy peasant covered in soot.”

He closed the door, walked up to her, took her shoulders, and pressed his mouth to hers. In the Western films they had seen together, this was what the man did when the woman was upset, and then the beautiful starlet would melt into the man’s embrace. He wasn’t sure what to do with his lips or tongue, but he tried to scoop her towards him with his arms. Cecilia bit his lip, hard. When he pulled back she laughed, “You coward, can’t even stand up to your wife?” He touched his lip, tasted the salt, looked at his red fingertips. She said, “Is that what you call a kiss? It’s like kissing a block of wood.” Percival rushed upon Cecilia, they fell to the floor of the cabin with a lurch of the boat, and Percival forced his hands up her blouse. She struck him with her fists, landed punches on his sides. His lip bled freely, he kissed her through her angry insults, smeared her face red with his blood. Until his jacket was off, trousers, and then her blouse, and now they both struggled from their clothing until they began to move together rather than apart.