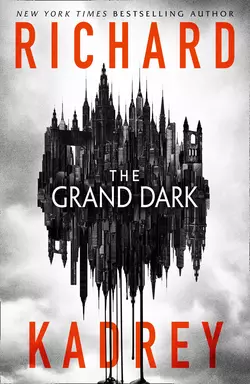

The Grand Dark

The Grand Dark

Richard Kadrey

‘The Great War was over, but everyone knew another war was coming and it drove the city a little mad.’A new fantasy world from the bestselling author of SANDMAN SLIM.

Copyright (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2019

Copyright © Richard Kadrey 2019

Cover design by Jeanne Reina © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover illustration © Will Staehle and Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Richard Kadrey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008288853

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008288860

Version: 2019-05-17

Dedication (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

To Drexel and Conan,

both of whom should have been

around a lot longer

Epigraph (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

There were a few short, wonderful years of euphoria when the slaughter was over. Of course, nothing had been settled and we knew it but, in its own way, watching the cataclysm hurtle toward us made the madness of the wild time even sweeter.

—Günther Harden, Cocaine and Bullets: My Lost Years

CONTENTS

COVER (#ue5e5e7ab-3d5f-5529-a2f8-a880c08fa6e0)

TITLE PAGE (#u0b88d854-8b37-5942-aa69-e2ff7acbd5a7)

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH (#u8f387c41-c88a-5917-88c2-3778115d5a1d)

MAP

CHAPTER ONE

THE CITY. THE AIR.

CHAPTER TWO

THE SECRET FETE

CHAPTER THREE

A CURSED PLACE

CHAPTER FOUR

ABOVE THE CITY

CHAPTER FIVE

HINTERLAND

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE REFUGEE ROAD

CHAPTER EIGHT

EUGENICS

CHAPTER NINE

SERVANTS AND WARRIORS

CHAPTER TEN

AT THE STREET MARKET BY THE CROSSROADS

CHAPTER ELEVEN

XUXU: ARTISTIC MOVEMENT OR ACADEMIC PRANK?

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

THE WALKING WOUNDED

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

THE WONDERS OF THE SOUTH

CHAPTER TWENTY

THE SHAPE OF THE WORLD

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

THE CORRUPTER OF INNOCENCE, ACT 1

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

FOOTNOTES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY RICHARD KADREY

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Map (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

CHAPTER ONE (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

The great war was over, but everyone knew another war was coming and it drove the city a little mad.

Near dawn, Largo Moorden pedaled his bicycle through the nearly deserted streets of Lower Proszawa. It was exactly one week since his twenty-first birthday. Fog from the nearby bay and smoke from the armaments factory left the center of the city looking like a flat, ashen mirage. As Largo sped over the Ore Bridge, the edges of Gothic office buildings, dwellings, and cafés coalesced into view. Streetcars gliding atop silent magnetic tracks in the street and above, old church spires—shadowy outlines a second before—solidified and were gone.

At the bottom of the bridge, where Krähe Vale crossed Tombstrasse, a line of Blind Mara delivery automata sat waiting for the crossing signal to change. Some of the larger contraptions—the Black Widows carrying machine parts for the factory—resembled wrought iron spiders the size of pushcarts, while the little tea and breakfast Maras were wooden bread boxes decorated with wings and carvings of flying women. Largo was tempted to veer into the line of machines and kick over one or two of the smaller ones. He knew that someday soon the Maras were going to put human couriers like him out of business. Each time he thought about it, a little wave of panic bubbled up from his stomach because, aside from a strong set of legs, the only things Largo possessed that were worth money were his bicycle and an encyclopedic knowledge of every street and alley in the city.

To Largo’s surprise, while the crossing signal still read HALT, one of the little winged bread boxes crept past the other Maras and whirred quietly across Krähe Vale. With a mechanical rumble, a squat, armored juggernaut carrying soldiers sped around a corner and crushed the bread box under its metal treads without slowing. All that was left of the little carrier were a small motor sputtering blue sparks, splinters, and a flattened sandwich. Largo hadn’t eaten for a day and the sight of food made him hungry. Still, he smiled. Indeed, the Blind Maras would put him out of business one day, but not today, and not for many days to come. When the signal clicked to PROCEED he guided his bicycle through the remains left in the intersection as the rest of the automata split up, carrying their goods all over Lower Proszawa.

The clock over the Great Triumphal Square—renamed, perhaps a touch optimistically, after the war—showed that it was just a few minutes before six. Largo had spent far too long in bed that morning with Remy, his lover, but it was so hard to leave her. He bent over his handlebars, pedaling faster, knowing all too well that being late at the beginning of the work week was a good way to have Herr Branca snapping at you until Friday. Worse, it could result in a humiliating dismissal.

The edges of the plaza were coming to life. Bakers laid out loaves and pies in the windows of their shops. The newspaper kiosk attendant by the underground tram station cut open piles of tabloid yellowsheets full of political intrigue and reports of the previous night’s murders. All-night revelers wandered through the square, still jubilantly drunk from the evening before. Along the gutters, purring piglike chimeras cleared the street trash by devouring it.

Beyond the edges of the plaza, prostitutes flirted with men in strange masks made of steel and leather—Iron Dandies, they were called, but never where they could hear it. They were war veterans considered too disfigured to be glimpsed by the city’s ordinary citizens—Largo among them. He’d heard that if you stared too long at a Dandy he’d rip his mask off, giving you a good look at his mutilated face. Seeing a Dandy that way was considered bad luck.

Bad luck or no, the truth was that Largo didn’t want to see what was under the masks or think about how the wounds, or the war itself, had happened. He just put his head down, pedaled harder, and arrived panting at the courier service as the plaza clock rang six.

Dropping his bicycle next to those of the other couriers, Largo ran up the stairs to the office and made it inside before the head dispatcher, Herr Branca, noticed his tardiness. He lingered at the back behind the other messengers so that his supervisor wouldn’t see him sweating.

Herr Branca was a burly man, one of the strange sort who seemed to have been born old. None of the couriers knew his age, but depending on the season and whether he’d shaved or not, they guessed it to be anywhere from thirty to sixty. He wore the same thing every day: pinstriped pants, matching vest, and a white shirt with an old-fashioned starched collar that he left open except when visiting their superiors. The bottom button on his vest was always missing. This could mean only one of two things: that Herr Branca was an eccentric who cut the bottom button off all of his vests, or that a second vest was beyond his means. No one at the service took Branca for an eccentric, so that had to mean their supervisor was so poorly paid that his choice in clothes was no better than the couriers’. This possibility always depressed Largo. He liked being a courier, but if Herr Branca was his future, perhaps it was time to make other plans.

But what?

Different futures weren’t easy to come by in Lower Proszawa.

As he did every morning, Branca leaned heavily on a standing desk, shouting names and the addresses where couriers were to go while old, battered Maras handed them whatever documents or parcels they were to deliver.

When Branca had called most of the morning’s deliveries and the room was nearly empty, Parvulesco, Largo’s closest friend at the service, gave him a worried look as he carried a parcel out the door. Largo shrugged. Maybe Branca had seen him come in late and was keeping him back for a good talking-to. There was nothing to do but wait and endure whatever was coming. Parvulesco mouthed, Good luck, before heading out.

Soon, everyone else had been given an assignment and it was just Largo and Herr Branca. The supervisor didn’t look up for two or three minutes as he took his time filling out a small pile of paperwork. As the seconds ticked by, Largo imagined all sorts of scenarios. A simple dressing-down. Having his pay docked. Maybe he’d even be fired. He stood still, hoping to not draw attention to himself, but after a couple more minutes passed he couldn’t stand it anymore. He cleared his throat.

“Do you have a cold, Largo?” said Herr Branca. “If so, kindly keep your distance, as it would be inconvenient for me to be ill at this time.” He spoke quietly. Branca always spoke quietly, no matter the topic or circumstances. The couriers joked that if he were an executioner, you’d never know he was there until your head was on the ground.

“No, sir. It’s nothing like that. I was just wondering if …”

“If I noticed you come in late, then hide in the back like a cockroach from the light?”

“Yes,” Largo said. “Something like that.”

Herr Branca looked up wearily. “Rest easy, Largo. While you were tardy and more than a bit insectile in your earlier behavior, you’re not going to be fired.

“In fact, you’re being promoted.”

Largo frowned, afraid he’d misheard his supervisor. “Promoted?”

Branca set down his pen and sighed. “You’re aware of the word, aren’t you? It’s a verb meaning ‘to advance in rank.’ ‘To ascend to a higher position.’ Must I explain it further?”

“No, sir. It’s just that … it’s a bit unexpected.”

“Quite, especially considering your less-than-cordial relationship with the clock,” said Branca. “That’s going to have to stop. Do you understand me? This promotion brings new responsibilities, and promptness is one of them. Can you handle that?”

“Yes, sir. I can.”

“Very good. Now stop cowering at the back of the room and come up here so I can explain the lofty position to which you have ascended without having to shout.”

Largo was still wary as he approached Herr Branca’s desk, waiting to find out that the promotion was a mistake or a cruel joke and his supervisor was going to fire him after all. Branca was looking over more papers when he reached the desk and once more Largo couldn’t help himself.

“Why?”

“Why the promotion or why you?” said Branca without looking up. “Both, I guess.”

“Did you happen to notice König was not with us this morning?”

König was the company’s chief courier, a tall, handsome man just a few years older than Largo. “No, sir. I didn’t,” he said.

Branca tugged at his collar. “I didn’t expect so. But it’s true nevertheless—he wasn’t with us. And it’s likely you won’t see him again here … or anywhere else,” Branca said. “He’s been arrested by the Nachtvogel.”

Largo didn’t say anything for a moment, still not sure whether Branca was playing him for a fool. König was a nobody, as were all the other couriers at the company. Why would the secret police take away a nobody?

“You saw it happen? I mean, they arrested him here?”

Branca nodded. “Right where you’re standing now.”

Largo looked at the floor, not sure what he was expecting to see. Then, feeling foolish, he looked back at Branca. “I don’t understand. What would the Nachtvogel want with König?”

“I have no idea because I didn’t ask, an attitude I advise you to emulate should you ever find yourself face-to-face with them.”

Largo took a step closer to his supervisor and said very quietly, “What were they like?”

Branca cocked his head for a moment as if looking for the precise words. “Men. They looked like men. Very serious men.”

“That’s it?”

“Except for the horns and hooves. And their long, forked tongues, of course,” said Branca. He made a face at Largo. “Don’t ask silly questions, boy. They were citizens like you or me. And before you ask one more idiotic thing and I’m forced to reconsider your promotion, I’ll tell you this. I heard one significant word as they were putting König in irons: anarchist. Personally, I never took the man for a political extremist, but there you are.”

Largo shook his head. “I wouldn’t have guessed. I mean, he never talked about politics. It was always about money, his girlfriend, and work. The same things we all talk about.”

“Would you expect an anarchist to shout slogans from the loading dock at lunchtime?” Branca said. “And as for his talk about money, well there you are. More than one good man has been turned to crime by dreams of easy cash. Don’t let that happen to you. You’ve been given a rare opportunity. Use it wisely.”

Largo nodded, his earlier fear giving way to feelings of guilt at his good fortune. Good fortune that came on the back of—no, not a friend, but someone like him, at least, someone he knew and moreover had nothing against. He felt a little queasy, but then he straightened. Branca was right. This was an opportunity, and a promotion would mean more money in his pocket. With luck, there would be enough that he wouldn’t ever feel hungry again at the sight of a crushed sandwich in the middle of the street. He thought of Remy and his mood lightened slightly. He couldn’t wait to tell her about it after work.

Branca leaned on his desk to get closer to Largo. When he spoke, his voice was quiet. “The reason I’ve told you all this was to impress upon you the importance of your new position. It’s a great embarrassment for the company to have one of its trusted employees hauled away in chains. If the news got out it would be very bad for business. Therefore, we must redouble our efforts and do everything we can to keep up the company’s good name. Do you know why?”

“Because we’re grateful to them for the opportunities they’ve given us?” he said.

“Don’t be naïve.” Branca tapped his pen on his desk. “Because you and I are utterly disposable. Never forget that.”

“I won’t.”

“Good. Now, welcome to your new position, chief courier.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Branca held out a hand to him. When Largo shook it, he was surprised by the force of his supervisor’s grip. He’d never seen Branca move more than a step or two in any direction, so it was a shock that there was any strength left in his large body. And what an even greater shock to hear the man’s concern for his own position. It didn’t exactly make Largo like the old fossil any more, but he couldn’t help feeling a bit of sympathy to hear someone Branca’s age refer to himself as “utterly disposable.”

“Does the promotion mean that I’ll be spending more time in the office?” Largo said.

Branca let out one grunting laugh. “God help us all if it did. No, you’ll continue your normal duties, making deliveries and picking up goods, but you’ll be doing it in parts of the city that you’re not used to—including some of its most prosperous districts. That’s why I chose you. None of the other rabble here know Lower Proszawa as well.” He paused for a moment, then said, “Also, you seem generally honest, which is important. Some of the parcels and documents you’ll be carrying will be worth considerable sums of money. Can I count on you to do your job honorably and intelligently?”

Largo was a little shocked by the question. No one had ever asked him anything like it before. “Yes, sir. Of course,” he said.

“Good. I thought so. Here are some forms for you to sign to make your promotion official,” said Branca. He handed Largo a stack of papers, then dropped a leather box about ten inches long on top. “And here is a new tool of your job. With luck, you’ll never need it.”

Largo took the papers to a nearby table, set them down, and picked up the box. Turning it over in his hands, he found a small brass lock. With just a little pressure it popped open. At first, Largo wasn’t sure what he was looking at. It was made of a dull gray metal. There were holes in it that were clearly meant for his fingers. He put them in and felt a sort of metal grip against his palm while the rounded loops over his knuckles were studded with spikes. He pulled the strange object the rest of the way out of the box. It was a knife. A trench knife from the war, with blood channels down the blade and brass knuckles over his hand. Largo looked at Herr Branca.

“Sir?”

His supervisor glanced at him. “You wear it in a harness under your coat,” he said. “Understand, with every job comes certain liabilities. Your promotion will bring you new respect and a larger salary. Unfortunately, it will also make you a target.”

“Oh,” Largo said. He hesitated for a moment, not liking the word target. However, he shook off the feeling and reached back into the box, pulling out a tangle of worn leather straps and clasps. The harness, he guessed. “I don’t know how to put it on.”

The old man nodded. “I’ll show you. Welcome to your future, Largo.”

Having Herr Branca strap him into the harness was an embarrassing experience. The couriers were all required to wear black suits and ties while making their deliveries. Years before, the company had given them a clothing allowance to make sure they remained clean and tidy on their rounds. However, the allowance had stopped during the war and never been reinstituted. Largo’s one suit was of cheap wool and barely thicker than paper. Worse, the seam had split along one side of the white shirt he’d worn that day, so it was held together with safety pins. To his credit and Largo’s relief, Branca said nothing about any of that as he wrapped the harness around the young man’s back and shoulders so that, with his jacket on, it and the knife were entirely invisible. Largo moved his shoulders and twisted this way and that, feeling tight and uncomfortable.

Branca said, “How does it feel?”

“Strange. But not bad. I’m sure I’ll get used to it quickly.”

“See that you do. Keep it on whenever you’re on your rounds. If I were you, I would also wear it coming to work and going home at night.”

Largo looked at Branca gravely. “Do you really think it’s that dire? I’ve traveled these streets all my life and except for places like Steel Downs and the docks, I’ve never felt myself to be in much danger.”

“Well, you are now. And not just from street bandits. There are young men in this very company that you need to keep an eye on.”

“You can’t mean that, sir. Who?”

Branca went back to his desk and pressed a button on the side, summoning a small Mara. “Andrzej. Weimer. They’re both convicted criminals. Did you know that?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Their convictions weren’t for violent offenses—otherwise the company wouldn’t have taken them on. But management likes to hire a few unfortunates every year as a show of good faith in the government’s rehabilitation efforts.”

Largo shrugged. “If they’re rehabilitated, then what’s the problem?”

Branca shook his head. “Largo, you can’t afford to be this naïve anymore. I said their convictions were for nonviolent crimes. God knows what else they did before they were arrested. Do you understand?”

“I think so,” Largo said, touching his elbow to the hilt of the knife under his coat. He didn’t like Andrzej or Weimer, but saying so might cause trouble. “Still, we’re all friends now. Of a sort.”

“I’m glad to hear it. Let’s hope that Dame Fortune smiles upon you and it remains that way.”

Largo didn’t say anything. It was a lot to take in all at once. A promotion. Herr Branca’s speaking so frankly to him. A lecture on the dangers all around him. Plus, he hadn’t had a dose of morphia since the previous night. A chill was building inside him and he was afraid that if he was stuck in the office for more than a few minutes, his hands might begin to shake.

Sure enough, Branca said, “You’re looking a bit pale. Are you all right?”

“Fine, sir. It’s just a lot to think about.”

“Think at lunch. Right now, you have your first delivery.” From the Mara, Branca took a wooden box about the size of the one that had held the knife and tossed it to Largo. “The address is on the parcel. You know the area, I believe?”

Largo checked a slip of paper affixed to the box with red wax. It was a street in Haxan Green. He drew in a breath, wondering if this was some kind of test. Unpleasant as he knew the delivery was going to be, he wasn’t going to let that stop him. “Yes. It’s at the far end of Pervitin Weg, where it crosses the canal.”

“Very good. Not the best part of town, but not bad for a first run in your new position.” Branca took a leather shoulder satchel and tossed that to Largo too. “Keep your new deliveries in that. It’s old and if you think the stains inside look like dried grease, they are. It’s the type of bag used by many of the workers at the armaments factory. A nondescript way to haul your cargo and perhaps save your hide. Do you have any questions before you go?”

“None,” said Largo. “Thank you again for the opportunity, sir.”

“Stop thanking me and stop saying ‘sir’ all the time. That’s for the others. Not the chief courier.”

Largo’s bones felt icy. He needed to get away. “All right,” he said, having to choke back a reflexive sir. “Before I go out, do I have time to use the toilet?”

Branca went back to doing paperwork. He didn’t look up when he spoke. “Use the toilet if you need to. Better now than being arrested for pissing into the canal.”

Largo put the box in the shoulder bag and started out. His hands were beginning to tremble.

“One more thing, Largo,” said Branca.

He stopped nervously midstride. “Yes, sir?”

“Your chum Parvulesco. Keep an eye on him too. He’s never been arrested, but he has a most colorful reputation.”

“Thank you. I’ll remember that,” said Largo before hurrying out of the office and down the hall to the employee toilets. Once inside, he locked himself in the farthest stall from the door. His cold hands shook as he pulled the bottle of morphia from an inside pocket of his jacket. Earlier, as Branca had taken it off him to fit the harness, he’d been nervous that his boss would discover the drug. Now Largo couldn’t care less. The only thing that mattered was the bottle.

He unscrewed it, drew a portion into the rubber stopper at the top, and squeezed three drops under his tongue. It was one more drop than usual, but these were dire circumstances and he needed the relief an extra drop would give him.

Within seconds, the blizzard inside him began to calm and he felt warm again. The muscles in his shoulders and back unknotted. The tension in his jaw eased so that he wasn’t tempted to grind his teeth, which, along with the shakes, was one of the sure giveaways of morphia addiction.

Not that any of that mattered now. His nervousness over the promotion and Branca’s paranoid warnings meant nothing. His stomach settled as his hunger pangs vanished. He felt wrapped in safety even as he thought again of the humiliation of staring hungrily at the sandwich in the street.

Never again.

Never.

Again.

Remy’s beautiful face swam into his head and he couldn’t help but close his eyes. Just for a second.

And drifted back to earlier that morning.

Remy was in bed, wrapped in a sheet. She turned the pages of a script with one hand and smoked a cigarette with the other. Largo was in the little kitchen of her flat making tea for them both. It was still dark outside. They hadn’t slept much the previous night.

While he waited for the water to boil, Largo took a step out of the kitchen and called to her. “Is there any cocaine left? I could use a bit to help me wake up.”

Remy glanced at the bedside table. “Not a speck.”

“Damn.” He leaned back against the wall. “It’s your fault for keeping me up so late.”

She didn’t look up from her script. “Yes, dear. I distinctly remember you saying how much you wanted to sleep as you took my clothes off.”

The teakettle whistled and Largo turned off the burner. “If only I could have found your pajamas, none of this would have happened.”

“Hush,” Remy called. “I need to learn this script.”

As the tea steeped, Largo went back into the bedroom and lay down next to her. “Please. You don’t need any time. You memorize those things in a flash.”

She stubbed out her cigarette. “You think so?”

He laid his head sleepily against her shoulder. “No question. It used to take you days. Now it seems like you have a new script in your head by the time you finish reading it.”

“I hadn’t really noticed.”

Largo yawned. “You learn the words and blocking faster and better than ever. Are you doing something different?”

Remy shook her head. “Nothing. But I’ve felt better since the doctor gave me a shot. Sharper. More clear-headed.”

“What kind of a shot was it? I could use one.”

“Vitamins, I think.”

As he went to check on the tea, Largo said, “You haven’t had one of your attacks in a while.”

“That’s a relief. Now leave me alone. I have to work.”

He poked his head out from the kitchen. “You’re quite sure there’s no more cocaine?”

Remy playfully tossed a pillow at him. “Finish making the tea and be happy I don’t push you out the window for interrupting my work.”

Largo froze in the doorway. “Work …”

He lurched to his feet in the bathroom stall, realizing he’d nodded off. He checked the address on the package one more time and left the building through the loading dock so that he didn’t have to pass Herr Branca’s office again. Promotion or not, he’d had enough of the old man’s scrutiny for one day.

Outside, the fog had begun to lift somewhat, but the sky was still gray under the smokestacks of the armaments factory. A light mist fell as Largo pedaled along Tombstrasse, making the air smell fresh and clean. With the welcome promotion, good air in his lungs, and morphia in his blood, Largo felt better than he had in days.

THE CITY. THE AIR. (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

From Noble Aspirations and Hard Realities: Life in Lower Proszawa by Ralf Moessinger, author of High Proszawa: A Dream in Stone

A haze, perpetual and gray, hangs over much of Lower Proszawa, like a murder of crows frozen in flight. Below, the coal plants that dot the city smolder and roar, roiling black ribbons of soot into the atmosphere. There, they’re caught by the wind and distributed throughout the city. The dust settles everywhere, on the rich and poor alike. Of course, the wealthy have the means to sweep their streets clean, as if soot wouldn’t dare venture into their districts, griming the windows and tower rooms that overlook the roofs of the less fortunate.

But even the rich can’t entirely keep ahead of it. The dust invades homes, offices, and churches, drifting down chimneys, snaking through cracks in window frames and under doors. The outdoor cafés and markets that display fruits and bread in the open air employ troops of ragged children armed with horsehair brushes and dustpans to wipe every surface clean. They throw the soot into the sewers, where it mixes with the city’s waste and drifts out to sea in a black tide that stains the hulls of fishing boats and smuggler ships alike a uniform gray. People call the color “city silver” and laugh it off because what else is there to do?

Thus, the citizens of Lower Proszawa have learned to live with the dust, even be amused by it. Of course, in the postwar elation that’s gripped much of the city, almost everything is amusing. Besides, it rains frequently and when the clouds part, the streets are washed clean, if just for a day or two.

Rain or shine, however, the power plants are nothing compared to what truly fills the skyline. Dominating much of the city are the cluster of immense foundries and assembly lines that make up the armaments factory. Unlike the streets, it is never completely clean. The coal dust clings to its sides and roofs. When the rains fall, they leave strangely beautiful ebony streaks and rivulets down the exteriors of the buildings, making the factory look ancient—like a mountain range that has been rooted to the spot forever.

Districts such as Kromium and Empyrean are kept pristine by cleaners who work in clouds of filth. Ironically, in some ways these workers are the lucky ones. While they go about their jobs, the crews wear surplus gas masks left over from the war. That means that for a few hours every day, they breathe air cleaner and sweeter than that of even the wealthiest industrialist or banker. Still, not everybody has the means to cope with the gray air so easily. It is a particular problem in the Rauschgift district.

Among the people I interviewed for this piece, Frau Mila Weill’s story is typical of the area. She lives in a cramped apartment with her children and grandmother. Herr Weill died suddenly from the Drops a few months earlier, leaving Frau Weill as the sole breadwinner. There are many explanations for the Drops among the ignorant class in these poorer districts: that foreigners from the southern colonies put it in the food shipped north or that chimeras that gobble trash in the gutters spread it with a bite. Frau Weill saw her husband die in agonizing convulsions and wonders if that is her fate too. She has a chronic cough, which is typical in the area, and it has advanced to the point where there is often blood in the sputum. Unable or, perhaps, afraid to go to one of the city’s hospitals for the indigent, she relies on the advice of her grandmother. The old woman tries to comfort Frau Weill using the only tools she has: folk remedies from the ancient past. She assures Frau Weill that she merely has a “touch of Rote Lungen,” and that “thistle-root tea will clear that right up.”

Frau Weill wants to believe her grandmother, but no amount of tea helps her condition. Each day, the red marks on her handkerchief grow. During one of our interviews she confessed that she had thought about finding someone—anyone—to marry so that he would be obliged to care for her family after she was gone. (There was an awkward moment in that day’s discussion when I suspect she considered asking me.) Though she still uses her grandmother’s tea remedy, she continues to believe that her condition is really an early stage of the Drops. However, she has formulated her own theory: that the disease isn’t spread by foreigners or chimeras. Frau Weill believes that it comes from the very air.

Spurred on by what can be seen only as a new urban folk belief, one morning Frau Weill took some of the household money and attempted to buy a gas mask from one of the cleaners in Kromium. She says that he laughed in her face. To make matters worse, the conductor on a tram asked her to get off, as her coughing fits were disturbing the other passengers. Since then, she remains at home, waiting for what she believes is the inevitable. Frau Weill keeps a constant watch on her arms and legs, certain that someday soon the convulsions will come. As our final interview came to a close I once again had that sense that she was on the verge of proposing marriage, and I was obliged to leave more abruptly than is my normal fashion.

Whatever the truth is about Frau Weill’s condition, we must agree on one point—that the “city silver” air in Lower Proszawa is as much a defining characteristic of the place as prewar High Proszawa’s clear blue skies. While the high city was known for its universities, museums, and sprawling stone mansions, the swirling gray gusts of the low city represent progress, industry, and strength. And while those things might inconvenience some, the power plants that fuel the place and the armaments factory that keeps all of Proszawa prosperous and safe are national treasures every bit as much as the high city’s more traditional elegance.

CHAPTER TWO (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

While the trip to Haxan Green had been fast and pleasant, his arrival in the old district was decidedly less so. Largo hadn’t been in the Green in years and the place was grimmer—and grimier—than he’d ever seen it.

The Green had once been a fashionable district where wealthy families from High and Lower Proszawa enjoyed their summers, spending many nights at the enormous fair at the end of a long pier. But the pier and fair had collapsed decades ago and were now nothing more than a pile of waterlogged timbers festooned with canal garbage and poisonous barnacles that killed wayward gulls.

The derelict homes that lined the broad streets had once sported gold-leaf roofs and sunny tower rooms that gave the inhabitants views of both the High and Lower cities. Now the buildings were rotting hulks, the gold leaf long gone and the roofs crudely patched with wood from even more run-down habitations. Most of the lower windows were blocked with yellowsheets and covered with metal bars from fallen fences. Few had any glass to speak of. The addresses of the old homes had all been chiseled away. This was by design rather than neglect, though. Only those acquainted with the district could find any specific dwelling. Fortunately, Largo knew the Green well.

He chained his bicycle to the charred skeleton of an old delivery Mara outside one of the tower blocks. Skinny, filthy children played war in the weed-strewn yard, throwing imaginary grenades of rocks and dirt clods at one another. The children stared at Largo for only a moment before going back to their game, but he knew their eyes were on him his whole way into the building. He checked his pocket to make sure he had a few coins so there wouldn’t be any trouble later.

He walked up three flights of stairs littered with stinking, overflowing trash cans and sleeping tenants too sick or drunk to make it all the way home. There were holes in the walls where old charging stations for Maras and wires that provided light for the halls had been torn out, the copper almost certainly sold to various scrap yards along the canal.

Without numbers identifying the individual flats anymore, this could have been a difficult delivery, but through long practice, Largo knew how the apartments were laid out—even numbers on the north, odd on the south—so he found his destination without trouble.

Out of habit, Largo straightened his tie before knocking on the door of the flat, then felt foolish for it. A straight tie was the last thing that would impress Green residents; it might, in fact, make them hostile. But it was too late now. He’d already knocked.

A moment later an unshaven man wearing small wire-rimmed glasses opened the door a crack, leaving the lock chain across the gap. “Who the fuck are you?” he said.

Largo took the box from his shoulder bag and said, “Delivery,” in a flat, indifferent voice. Saying anything more might invite suspicion. Speaking any other way definitely would.

The unshaven man tilted his head, taking in Largo and the box. His hair was gray and thin. There were scabs on his forehead near his hairline. It looked like he’d been picking at them. “Where’s the other one?” he said.

It took Largo a second to understand that the man meant König. He shook his head. “He doesn’t work there anymore. It’s just me now.”

“Huh,” said the man. “You’re a bit pretty for this neck of the woods.”

Largo straightened, feeling the knife under his jacket. His sense for the mores of the old neighborhood was coming back to him—as was his hatred for them. He knew what would come next from the scabby man and how he was supposed to respond, and the cheap game brought back frightening childhood memories. He said, “Fuck off, my fine brother. I grew up by the canal on Berber Lane.”

“Did you now? You’ve cleaned up since then.”

“My compliments to your spectacles.” Largo loathed the ritual posturing of the Green, and he’d hoped never to have to do it again. Yet his promotion had brought him straight back to this awful place. It wasn’t an auspicious beginning for the new position. He pressed on, holding up the little box and waggling it up and down. “Do you want it or not? I don’t have all day.”

The man was starting to say something else when a piercing scream came from somewhere in the flat. “Wait here,” he said, and closed the door. Standing in the hall, Largo heard more screams through the door. Questions and images flowed through his head. Had the scabby man kidnapped someone? Was someone—a woman, he was sure it was a woman—being beaten in another room? Or was she dying in childbirth? The next scream wasn’t just a wail, there were words: “Now! Now! Now! Now!” Largo dug his heel into a splintered part of the floor as it dawned on him that he recognized the screams.

It was someone deep in the throes of morphia withdrawal.

He looked at the box. There weren’t any markings to indicate its origin. He wondered if it was medication from a hospital. He was sure Herr Branca wouldn’t send him out on his first delivery with something illicit. It must be medicine, he told himself.

A second later, the flat’s door opened again. The man stuck out a grimy-black hand and grabbed for the box. “Give it to me.”

Largo took a step back out of his reach. He got the pad and pencil from his bag. “You have to sign for it,” he said.

The man’s hand dropped a few inches. “Please. I need it now.”

“Not until you sign.” Largo knew the rules of the Green. If he backed down now it would be a sign of weakness, and if anyone was watching the exchange it would put him in danger. He gave the man a hard look even as he felt a few beads of perspiration on his forehead.

“Wait,” said the scabby man. He closed the door for a moment and when he opened it again there was a pile of coins in his hand, including two small gold ones. “Take it.”

“Are you trying to bribe me?” he said, a little surprised by the offer.

There was another scream from the flat. Largo felt like a heel for continuing to play the game, but he knew he had to.

“It’s a tip,” said the man. “For your trouble and my earlier rudeness. Only you have to sign the form.”

Largo looked at the money. Whether it was a bribe or a tip, it was the largest amount of money anyone had ever offered him for a delivery.

There was another scream, this one more violent than the others. Largo grabbed the coins from the man’s hand and gave him the package. “Good luck,” he said, but the man had already slammed the door shut. Largo put the coins in his pocket and looked at the delivery form. There was no name on it, just the address.

Perfect. My first delivery as chief courier and I’ve already committed an offense that could get me fired.

With no other choice in the matter, Largo signed the form Franz Negovan, the name of a boy he’d known growing up in the Green. He was anxious and angry as he left the building, thinking that if all of his deliveries were like this, he wouldn’t last long as chief courier.

Downstairs, as he expected, the children who’d been playing war earlier were clustered around his bicycle. A dirty blond girl of about ten sat on the seat and looked at him with eyes that were forty years older and harder.

“We watched it for you,” she said. “Made sure nothing bad happened to it.”

Largo had been through similar shakedowns before and had known this other ritual of the Green was coming. When he’d been in similar situations as a child, when he’d had little to give or trade, the result was usually a beating or his running as fast as he could—and his bicycle being stolen or destroyed. These were only children, but in the Green, age didn’t mitigate danger. Fortunately, now things were different. He hoped.

He reached into his pants pocket and came up with some of the coins he’d brought from home and a few from the gray-haired man—all silver. He’d put the gold ones in his jacket. He said, “And you did an excellent job, I see. Here’s something for your trouble.”

The girl accepted the coins and counted them carefully. When she was done she nodded to the other kids and hopped off Largo’s bicycle. As soon as they were across the yard, the girl distributed the money to the other children and the war game resumed without missing a beat. Largo unchained his bicycle, dropped the lock into his shoulder bag, and pedaled slowly back down the route he’d taken earlier. As much as he wanted to speed away from the misery and memories of the Green, he kept to a moderate pace. To go faster was something else that he knew would show weakness. There were many unspoken but universally understood rules in the district, and he’d learned them all the hard way. The one odd thought that struck him as he pedaled away was that if, as a younger man, he hadn’t left Haxan Green, a hard-eyed little girl like the one at the tower block could have been his daughter. It made him think of his own family.

Largo had grown up with his parents in a decaying mansion by the canal. His father had a wagon and a sick horse that he’d probably bought under the table from an army stable. Father rode the wagon all over Lower Proszawa looking for scrap to sell and, like Largo, making the occasional delivery. Largo’s mother panhandled and picked pockets in the street markets around the Green. Largo had been a pale, scrawny child, and his parents had been very protective of him. Maybe too much, he thought now. He was always cautious and nervous around confrontations. Even his encounter with the scabby man, as well as he’d handled it, left him feeling slightly ill, which was humiliating.

Because no one had been home during the day to take care of him, Largo went with his father on his rounds. His mother worried about taking a small boy to some districts even more dangerous than Haxan Green—kidnappings were frequent and children were often sold off to fishing ships along the bay or pimps in the city. To protect the boy during his rounds, his father put him in a wooden crate up front in the wagon. It was through the air holes in the side of the crate that Largo first learned Lower Proszawa’s winding streets and alleys.

Later, he would become an expert while running from gangs wielding chains and knives or bullocks looking for his parents. Of course, he’d never admitted any of this to Remy. It was too embarassing. Besides, she talked as little about her family as Largo did about his, and it made him wonder if she had secrets too.

On his way back to the office, Largo was delayed by a caravan of double-decker party Autobuses. The city’s merrymakers always grew more boisterous in the days before the anniversary of the end of the Great War. Buses and street parties were some of the few places where the upper and lower classes mingled easily because each had the same goal—a gleeful obliteration.

When Largo returned to the courier office, Herr Branca was waiting for him.

“And how was your first foray into new territories?”

“Excellent. It went very well,” Largo said.

Branca glanced up from his paperwork. “I’m glad to hear that. König was seldom so cheerful when returning from Haxan Green.”

Largo smiled but wasn’t sure it was entirely convincing. “That’s too bad. As for me, I found the building, delivered the parcel, and made my way back without any problems.”

“Good. And there was no trouble with the client?”

Largo’s stomach fluttered for a moment as he thought of the forged receipt. “None, sir. Our meeting was both cordial and efficient.”

Branca chuckled. “Efficient. Again, something I’ve not heard about the Green before,” he said. Then he became more serious. “Tell me about the client. What was he like?”

The question took Largo by surprise. Herr Branca had never asked him about a client before, let alone one as peculiar as the gray-haired man. “He was just a man. An old man with gray hair and spectacles.”

“How did he appear to you?”

“Sir?”

“Was he in good health? Happy? Apprehensive? Was there anyone with him?”

Largo considered how best to answer the question. “He was surprised that I wasn’t König, but when I explained that he had moved on—I didn’t mention the bullocks, sorry, the police. After that he accepted the package without incident.”

Branca looked Largo up and down. “And was there anyone with him?”

“Yes.”

“A man or woman?”

“I’m not sure. I think a woman. But the person was in another room and I couldn’t see.”

“Of course,” Branca said, and Largo wondered what that meant. He started to say something but Branca cut him off.

“What was his condition? Dirty? Clean? Did you see his hands?”

“No. I didn’t see his hands.” But he recalled that that wasn’t true. The gray-haired man had tried to grab the parcel. “Well, I did. But only for a moment.”

Branca scribbled something on his papers. “Were his hands dirty, by any chance, especially the fingers?”

Largo thought about it. “I suppose they were, a bit. His fingers, I mean. A bit black.”

Branca held out his hand. “Let me have your receipt book.”

Largo handed it to him nervously.

His supervisor looked at the signed form for a long time. “And this is his signature?”

Quietly, Largo said, “Yes, sir.”

“I don’t see any smudges or dirt. Anything to indicate his dirty fingers. You’re sure they were blackened?”

Largo nodded. “Yes,” he said, then quickly added, “I held the book for him. He didn’t touch it. I’m sorry if that was against procedure.”

Branca tore the signed page out of the book and put it with the papers on his desk. Then he put the book in a drawer. “Not against procedure at all, Largo. However, in the future it would be best if the client was in possession of the book when they signed it. Please remember that.”

“Of course. I will,” said Largo, relaxing a little. It seemed that Branca’s preoccupation with procedure had kept him from examining the signature closely enough to recognize Largo’s handwriting. But he couldn’t help being curious. “If I may ask, sir, was this client special?”

“How do you mean?” said Branca, leaning casually on his desk.

“I mean, will I be questioned like this after each client? It’s no bother, you understand. I just want to know if I should pay special attention to them.”

“It’s always good to pay attention to clients,” Branca said, distant and officious, “especially for a chief courier. And no, I won’t interrogate you like this after each delivery. However, this was your first in your new position, so I thought it best to go over it carefully.”

“I hope I performed satisfactorily,” Largo said, hating himself because it sounded like groveling—and he had been sounding like that the whole day. Still, his position was tenuous enough that it seemed better to err on the side of caution, especially with Branca, who had dismissed other couriers as if swatting a fly.

“You did fine. But from time to time I’ll be asking you about other clients. A new procedure from management. Quality control and all that. They may wish to conduct interviews with some of them to see that we’re staying on our toes. I’m sure you understand.”

“I’ll make sure to pay more attention,” said Largo.

“Very good.” Branca gave Largo a new receipt book, then pressed the button on his desk that called a Mara. It brought out a large green folder that looked as if it might contain papers. “The address is on the front. You’ll find this delivery a bit less colorful and more posh than your last one. The Kromium district. Do you know it?”

“Very well.”

“Good. Herr Heller is an important client, so get there quickly. After this delivery you may go to lunch. And take your time. As chief courier you get a full forty-five minutes. Do you know why regular couriers only get thirty?”

“Because we, I mean they, are in such demand during working hours?”

Branca shook his head. “It’s to keep them from drinking too much and getting into trouble. It’s assumed that there will be no problems like that from the chief courier.”

“No, sir. I never drink on the job.” Largo wondered if Branca had caught sight of the morphia bottle in his jacket.

“Very good. I myself am accorded the luxury of sixty minutes for lunch. See? You and I are more and more alike.”

Oh god. What a miserable thought.

“I’ll do my best to live up to the company’s standards.”

Branca waved his pen at him. “Get going. I have papers to deal with,” he said. “Oh—and Largo? There’s no need to sneak out the back this time. The door you came in through is the shortest way out.”

Largo hurried away, surer than ever that Branca knew his secret. But if he did, why would he have given him the promotion, and why would he cover for him now? It didn’t make sense. In any case, there was nothing he could do about it right then. He’d just do his job, and sort this out when he had time. He thought then about Rainer Foxx. His friend was older and understood more about the real world than Largo felt he ever would. He sometimes imagined what life might have been like if Rainer had been his brother back in the Green. Maybe he wouldn’t have grown so afraid all the time.

He’ll know what to do. I have to talk to him soon.

Largo checked the address on the envelope, stuffed it into his shoulder bag, and pedaled away from the office as quickly as his legs would carry him.

Of course, Herr Branca had been right about the Kromium district. Its bright, wide streets, quaint cafés, art galleries, and cinema gave the place an open and pleasant atmosphere—the exact opposite of Haxan Green. Largo thought that if all his deliveries were to districts so violently in opposition to each other he might suffer whiplash.

The streets in Kromium were named for various metals, and the deeper you traveled into the district, the more valuable they became. They began at Boron Prachtstrasse, then Tin, Copper, and Iron. Alloys such as Bronze and Steel crossed the pure metal streets. The address Largo was looking for wasn’t among the loftiest metals such as Platinum, Osmium, and Iridium. However, it was still quite respectable and, he thought, it had a much more poetic ring to it than the more precious streets.

The Heller mansion stood near the corner of Electrum and Gold. Largo leaned his bicycle against a wrought iron gate twisted into elegant nouveau curls. He didn’t bother locking the bicycle this time. With luck, he wouldn’t have to worry about that again for quite a while.

The mansion’s front door was decorated with a sunburst made from a dozen precious metals. Even under the overcast sky, it shone brightly. Like many doors in the district, this one was solid steel—not for security reasons, but to keep within the aesthetics of the neighborhood. Rather than rap on the thick metal door with his bare knuckles, Largo used the gleaming rose-colored knocker. It was heavy and slightly dented on the underside. Gold, he thought.

I wonder how long that would last in the Green?

A moment later, a maid in black brocade and a small white bonnet answered the door. Before Largo could have her sign for the envelope he heard a woman’s voice from behind her. “Who is it, Nora?”

“A courier, madam. With a package for Herr Heller.”

A moment later, an elegant red-headed woman in an arsenicgreen gown appeared beside the maid. “I’ll deal with it, thank you,” she said. The maid curtsied and disappeared into the house.

A mechanical din boomed from the street as a driverless juggernaut rolled down the prachtstrasse. It was festooned with flags and large photochromes of the war dead. Patriotic music blared from speakers mounted on the front and sides of the juggernaut and the songs echoed off the buildings as it passed.

Frau Heller made a face at the behemoth. “Those things clatter by day and night. Of course, we all supported the war. I, myself, lost a cousin in the trenches of High Proszawa. But must we be reminded of the unpleasantness at all hours?” She looked at Largo.

He shook his head in agreement. “No, madam. It seems like a great inconvenience.”

“Do these dismal little parades go through your neighborhood too?”

“No. I’ve seen them in the Triumphal Square and some of the business districts, but not where I live.”

“You’re a lucky young man,” said Frau Heller. When she turned back to Largo her radiant smile faltered for a second, then recomposed itself. “What an interesting jacket,” she said. “Wool, is it?”

Largo was tired of clients commenting on how he looked, but he smiled back at the woman. “Yes, madam. Very comfortable on cool, gray days like this.”

“You have a lighter one for the summer, then?”

“Well, no, but with my new position—”

“Silk,” she said, cutting him off. “You’d look much better in silk than wool.”

“I’m not sure I can afford silk, madam. But thank you for the suggestion.”

“Try one of the secondhand shops along Tin and Pinchbeck. Some of the servants’ families sell their clothes when a family member dies. I’m told there are some wonderful bargains.”

Largo looked at Frau Heller, trying to grasp her meaning. At least in the Green he knew when he was being tested, but here he wasn’t sure if he was being mocked or given what this woman thought was truly useful advice. However, it wasn’t his place to ask or be offended by anything a client said, so he replied, “That’s most helpful of you. I’ll be sure to stop by very soon.”

“Here, this might get you started on your way to manly splendor,” said Frau Heller. She plucked the envelope from his hand and laid a gold Saint Valda coin on his palm, equal to almost a week’s wages.

“Madam, I couldn’t,” he said.

“Of course you can and you will. What’s your name?”

“Largo. Largo Moorden.”

She looked him up and down and smiled. “You’re a handsome young man, but I don’t want to see you here in wool again, Largo. You’ll frighten the neighbors.” She laughed as she signed his receipt book. Once she’d handed it back, her eyes shifted to a place over Largo’s shoulder and she frowned. “Oh dear.”

He turned to look and saw a small group of Iron Dandies in the street. They often followed the patriotic juggernauts, carrying small flags and begging.

Frau Heller called one of them forward and handed him a few coins, though they totaled less than she’d given Largo.

“Thank you, lovely lady,” said the man in a grating, tinny voice through a small speaker embedded in his scarred throat.

“You’re very welcome,” said Frau Heller. “God bless you for your service.”

She watched as the ragged procession of wounded soldiers continued on, limping and swaying on crutches behind the juggernaut. Without looking at him she said, “Were you in the war, Herr Moorden?”

Largo wasn’t used to being addressed so formally. However, he had a lie prepared for just such occasions. “I’m afraid not. You see, my elderly mother was quite sick at the time—”

“Ah. Your mother. Quite understandable,” said Frau Heller, cutting him off again. “I only ask because my husband is one of the heads of the armaments company, and I wondered if you might have used one of his creations.”

Largo became nervous. Most people stopped asking questions after he mentioned his mother, and he didn’t have many lies prepared to follow up. “No, I’m afraid I didn’t have the honor in this war.”

Frau Heller laughed lightly. “Perhaps you will in the next one, then.”

The next one?

Largo felt a little jolt of panic. There were always rumors of war in the north, but did Frau Heller know something? He ached to ask her, but knew to keep his mouth shut.

“Don’t be a stranger, Herr Moorden,” said Frau Heller, and she gave him a wink.

Not quite sure how to respond, Largo smiled and put the Valda in his jacket pocket with the other gold coins. He wasn’t sure exactly what had just happened, whether Frau Heller had flirted with him or insulted him. However, he now knew he had a price for any similar future encounters.

One gold Valda and you can say anything you like.

As he got on his bicycle he laughed, thinking how odd the wealthy were, understandable only to themselves and others of their particular species.

Riding out of Kromium, he turned and pedaled past the secondhand shops at Tin Fahrspur. The encounter with Madam Heller had been interesting, but not enough to convince him to spend his newfound wealth on a coat to please a woman he’d probably never see again.

The sky darkened and a light rain fell on his way back to the office. Along Great Granate, one of the city’s new automaton trams slid by silently, guided by magnetic rails laid beneath the paving stones. Largo grabbed a protruding light fixture on the rear of the tram and let it pull him all the way to the Great Triumphal Square. There, Largo used some of his remaining silver coins to buy a steak pie from the bakery he’d passed earlier that day. None of the other couriers ate lunch in this part of the plaza and that was fine by him. His new deliveries had put him in a peculiar mood.

He ate his steak pie, wondering if his parents had ever tasted steak in their whole lives.

When he’d been a boy riding in the crate in the scrap wagon, his father had sometimes told him about his adventures scavenging the city for goods to sell. One story that always amused Largo was that he would sometimes steal scrap from one foundry, drive it across town to sell to another, then steal it back in the night and resell it to the first. His father always laughed when he talked about it, and, in his little box, Largo laughed too.

What Largo’s father never talked about were his special deliveries. They could happen any time of the day or night and anywhere in Lower Proszawa. Over his mother’s objections, his father insisted that Largo come with him on the special trips because, he said, “The city at night and the city during the day are different beasts and you need to make friends with them both.” There was one particular delivery that Largo never forgot, no matter how much he drank or how much morphia he took.

It had been late afternoon along Jubiläum, a long way up the stinking canal. There was a small crowd buying fish and meat from the moored boats. Soon after they arrived, Largo’s father had handed an envelope—not unlike the one Largo had just given to Frau Heller—to a man dressed in much finer clothes than Largo normally saw in the district. Once his father had turned over the envelope, though, he and the well-dressed man got into an argument. His father shouted something about being cheated out of his payment and when he grabbed the envelope back, a group of other men, who had been lounging on cargo crates nearby, rushed him. A scuffle broke out. Unlike scrawny Largo, his father had been tall and strong and he knocked two of the men down without any trouble. But three others were on him like a pack of dogs. Before Largo understood what was happening, he saw a flash of silver. The men ran away and his father lay on the ground bleeding from a knife wound in his side. Largo cried for help, but the people in the crowd just stood and stared before going about their business.

Later, Largo’s friend Heinrich said that the knife had probably pierced his father’s lung. It took what seemed like hours for him to die, and the whole time he wheezed and gasped like a fish suffocating on the banks of the canal at low tide.

No one called the police because that wasn’t done in the Green. People brought his mother back from the market and she took Largo home to their squat. Neighbors buried his father in the garden of a stately home that was once one of Lower Proszawa’s more elegant brothels, but that was the end of the community’s involvement.

His mother seldom let him out of her sight after that. She taught him to keep quiet and not upset people. At first, Largo, who’d felt so free by his father’s side, fought with his mother about being locked in the house. He felt more confined there than he’d ever felt in the small crate on the wagon. One afternoon, while his mother was at the market, he’d sneaked out of the house.

It was winter and his breath steamed in the damp air. Largo ran to find Heinrich, who, he knew, would be by the stables, where the children often played. When he arrived, Largo found Heinrich surrounded by a gang of older boys from the Green. Largo crouched behind one of the stable doors so they wouldn’t see him, and was frozen there as the scene reminded him of the same one his father had endured. One of the gang demanded that Heinrich give them his heavy winter coat, and after some shoving and punching, he did it. Once they had the coat, he tried to run, but one of the boys hit him with a chain. He continued to beat Heinrich as the other boys kicked and hit him with pipes they’d hidden under their clothes. Once the gang had run off—and only then—had Largo crept from the stable to his friend’s side.

Heinrich lay in a pool of sticky blood. There was a crack in his forehead where part of his skull had caved in. Largo shook him and, stupidly, yelled his name. Across the road from the stables was a stand of withered trees, and the gang that had beaten Heinrich had been there, well within earshot. They came racing out, heading straight for him. Though Largo was small, he’d always been a fast runner. He darted away from the stables into Haxan Green’s back alleys and side roads. The boys chased him for what seemed like hours, but Largo kept ahead of them, ducking through basements, out through coal chutes, and doubling back on himself through the complex web of streets.

The sun had been going down when he finally managed to get home. Luckily, his mother hadn’t returned from the market yet. One of Largo’s chores in the evening was to start a fire in the old cast-iron oven so that she could cook them whatever she’d stolen that day. Instead, Largo hid in his room scouring Heinrich’s blood off his hands in a washbasin. After that, he didn’t fight when his mother told him to stay inside. He instead spent his time with old maps of Lower Proszawa he found in the attic, tracing the routes he’d taken on rides with his father and learning by heart the layout of the brilliant city, formulizing his paths of escape but also dreaming of life on those other streets.

After lunch, Herr Branca didn’t question him about the delivery in Kromium. He simply gave Largo another assignment right away in one of the few parts of town Largo didn’t know well—Empyrean.

It was one thing for a young man in shabby clothes to ride through Kromium without attracting too much attention. After all, that district wasn’t just for stuck-up bluenoses. It housed famous artists among the higher metals, along with scandalous bohemians within the lower alloys. Empyrean was different. Many of the best families from High Proszawa had migrated there during the early days of the war. It was a neighborhood of marble palaces, gleaming steel towers, and luxury flats in high-rises with facades of emerald and vermilion bricks imported from halfway around the world. At night they glowed brighter than the moon, and the people inside shone down on the rest of the city even brighter.

It was to one of those glowing buildings that Largo brought his last delivery of the day. At first, the uniformed doorman didn’t want to let him into the building and even tried to take the package away from him. When Largo wouldn’t let him, he threatened to call the police.

“Please don’t do that,” said Largo reflexively.

The doorman continued to stare at him. “Let me see your identity papers,” he said.

Largo took them out and reluctantly handed them to the man. He hated himself for doing it, but this was Empyrean, not Haxan Green. I can’t just bluff my way through this. If the police came, he knew that it would be a scandal for the company. He might get demoted for it, or even fired.

The doorman made a great show of studying Largo’s face and comparing it to the photochrome on his papers. Eventually the doorman said, “I’ll need to speak to your superior to allow you into the building.”

Feeling deflated, Largo grudgingly gave him Herr Branca’s caller number at the courier company. The doorman went into the lobby and picked up a gold-and-sky-blue enameled Trefle. It looked a little like a candlestick with a mouthpiece at the top. Twin listening pieces were attached to the base with thick green wire. It took him a full minute to get an operator to put the call through, and then it took several minutes more for Herr Branca to convince him that the “cheeky scarecrow” with a box under his arm was a legitimate courier. Finally, the doorman relented and let Largo inside.

“Go up to floor fifteen and come right back down again,” said the doorman. “I’ll be timing you. Take too long and no voice on a Trefle will save you from the bullocks.”

Largo wanted to say a lot of things to the doorman, but he knew that the call already guaranteed him a dressing-down by Branca, so there was nothing he could do about the officious prick at the door, the bullocks—any of it.

The lift he rode up in was larger than his flat, and with its crystal chandelier, golden fixtures, and pearl floor buttons, more opulent than most of even the well-off homes he often delivered to.

On the fifteenth floor he knocked on the door, hoping desperately that whoever opened it wouldn’t be as chatty as the gray-haired man or Frau Heller.

Largo got what he wished for.

When the door opened, he took out his receipt book, hoping to get business over with quickly with a servant. What greeted him instead was an elegant Mara. It was almost as tall as he was and decorated with silver and bright gems, by far the most spectacular Mara he’d ever seen. “May I help you?” it said.

The voice startled Largo. When most Maras spoke, the sound was small and tinny, but this Mara’s speech was soft and melodious. He pressed the parcel and receipt book forward.

“Delivery,” he said.

The Mara bent slightly, its eye lenses adjusting to take in Largo and what he carried. After only a few seconds’ hesitation, the Mara took the box and set it down gracefully on a nearby table. Yellowsheet scandal tabloids were piled high there and a few had fallen to the floor. A week’s worth of papers, at least. From another room, Largo heard laughter and music swelling from an amplified gramophone. The residents of the flat were having a party. He looked back at the pile of yellowsheets.

Has it really been going on for a week? Is that even possible?

As his pondered this, the Mara came back and held out its hands for the receipt book. He handed it to the machine without looking at its face. That was the most disturbing thing about the situation. The owners had placed a steel-and-leather mask on the Mara’s head, the kind worn by Iron Dandies. Largo didn’t think he could loathe Maras more, yet here he was staring at this monstrosity. He wondered how the owners had obtained the mask and what had happened to the Dandy who’d lost it. He thought of Rainer and wanted to snatch the mask off the automaton but knew that it would guarantee a beating from the police when the doorman called them. In the end, he took back his book and the Mara slammed the door in his face.

While waiting for the lift, Largo saw something he’d missed on his way up. Set into the wall was a large fish tank holding a colorful variety of chimeras—custom-made mutant creatures favored as work animals by the municipal services and pets by the well-heeled of Lower Proszawa.

Speckled black-and-white eels covered with long spines wriggled among a school of transparent bat-like fish. A pink lizard thing pulled itself across the bottom of the tank with bright red tentacles. Largo tapped the glass lightly with a fingernail. Ever since childhood, when a pack of wild hound-like chimeras had terrorized Haxan Green, he’d been fascinated by the strange creatures.

A gray starfish lifted from the bottom of the tank and affixed itself to the glass directly in front of him. As he leaned in close to get a better look, the starfish twisted its limbs and torso into a startlingly accurate imitation of Largo’s face. As he watched, the pink lizard crept up from behind and attacked it, dragging the twitching starfish to the bottom with its red tentacles and devouring it. Largo pulled back in shock. He shook his head—that was the one thing he could never understand about so many chimeras. If people could make them in any shape and with any temperament, why were they so often ugly and savage?

I would make only beautiful ones.

Pieces of the dead starfish floated to the top of the tank.

On his way out of the building, the doorman wanted to check Largo’s pockets to see if he’d stolen anything. Despite being afraid for his job, this was too much. When the doorman reached for him, Largo shoved him back against the building and jumped onto his bicycle. As he pedaled away, he was sure he could hear the doorman cursing him all the way out of Empyrean. He couldn’t help but smile.

THE SECRET FETE (#uee51e213-a568-55fa-9da5-f2b2cdc5d29f)

From A Popular History of the Proszawan Underworld by Stefan Kreuz

Der Grandiose Kanzler had been an elegant establishment before the war, serving some of the finest food and wine in Lower Proszawa. However, it had fallen on hard times and closed for good after the owner embezzled the remaining funds and eloped with one of the serving girls. A series of lawsuits kept the place shuttered since then.

But not out of business.

Now dubbed Der Fliegende Schwanz, it was a thriving speakeasy on the edge of the Pappen district, where it served the best bootleg whiskey, cocaine, and morphia in the city. Der Fliegende Schwanz was mainly a working-class establishment, but members of the gentry would sometimes visit when they were in the mood to slum for an evening. They were always welcomed with open arms because they had better pockets to pick than the usual rabble.

The bar was a merry place most nights, fueled by drugs and the ubiquitous postwar delirium. It was a gathering spot for war veterans, workers from the armaments factory, laborers from the docks, and prostitutes to drink, tell stories, and make love in the bar’s immense but empty wine cellar. Musicians played for coins all day and night. There was dancing and laughter, but seldom any fights, which was unusual for an underground saloon, with its heady mix of alcohol, drugs, and sex. Perhaps the reason the bar sidestepped so much random violence was a special sort of entertainment it offered its patrons.

A makeshift ring stood at the center of Der Fliegende Schwanz. At the top of each hour two or more Maras—freshly stolen, their functionality modified—fought gladiatorial battles to the death. Most of the purloined Maras came from bluenose families in the city’s most expensive districts, so watching them beat each other with clubs was doubly entertaining. Bookies took bets on the battles and liquor sales always went up because the winners bought the losers a round and the losers bought even more rounds to soothe their aching egos. And the music never stopped. Neither did the laughter, the lovemaking, or the drip of morphia under happy tongues.

Around midnight each night, everything in the bar stopped and the patrons sang obscene, drunken versions of patriotic songs. Many of the men were veterans and had fought in High Proszawa, so after the singing they played a game in which they spat streams of alcohol at photochromes of the Chancellor and the Minister of War nailed to the wall. The players stood behind a line on the floor and the one who came closest or hit the chromes the longest drank free for the rest of the night.

Der Fliegende Schwanz never closed. The party never stopped. The delight never ebbed. Every night was a holiday and every morning a feast. And if, on some nights, the crowds got a bit out of control during the Mara fights and started breaking bottles and glasses, who cared? Like the Maras, they were stolen. Everything was fun and nothing mattered because everyone knew that sooner or later the cannons would boom again and nothing would be fun and everything would matter.

Until then, there was always time for one more drink or one more kiss or one more drop under the tongue.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_2c10aca6-f281-5dbf-93be-ef44bdf9d09d)

When Largo returned to work, Herr Branca showed some compassion by not bringing up the call from the doorman immediately. His only acknowledgment came when Largo turned in his receipt book. Branca said, “We’re going to have to do something about your appearance.”

Largo touched his rain-soaked suit and looked at Branca. “Sir?”

“Your clothes. We can’t have the chief courier roaming the streets looking as if he’s just escaped the penitentiary, can we?”

“No. I suppose not.”

“Good. I’m delighted that you approve.”

“But I didn’t think my clothes were that bad.”

Branca filled in some figures on a form. “What you think about these matters doesn’t concern the company.”

“Of course,” said Largo, feeling like a prize pig on the auction block. “I didn’t mean to overstep.”

“Never mind. I’ve arranged that you will soon receive a certain sum of money with which you will purchase clothes and shoes that look a bit less like you stole them from a … what was the word the caller used?”

“Scarecrow?”

“Yes, that’s it. As you saw today, some districts don’t appreciate the working classes begriming their streets. Arrogant bastards. When you’ve acquired your new wardrobe, I’ll want to see it. Under no circumstances will you wear the clothes except on company business. Is that understood?”

“Completely.” Though both knew full well that he was lying.

“Good. Now to the important part. Seeing as how you’re an adult apparently capable of feeding and bathing yourself, please tell me that there is no need for me to accompany you on this excursion.”

Quickly, Largo said, “No, sir. Not necessary at all.” The thought of Herr Branca hovering around him as he tried on pants was horrifying. He remembered what Frau Heller had said. “I even know where to go.”

“Thank heavens. It’s the little mercies that help us sleep at night, don’t you agree?”

“Entirely,” said Largo, not quite certain what he was agreeing with.

“That will be all today. I’ll see you tomorrow promptly at six, yes?”

“On the dot, sir.”

“Very good. And you’re still saying ‘sir’ too much. Work on that.”

“I will,” he said, once more having to choke back the word sir and happy that he managed it.

When he left the office, he saw some of the other couriers gathered around the loading dock, smoking and talking. Weimer passed around a flask, making a great show of it that he wasn’t letting Parvulesco have a drink. Andrzej was the first to notice Largo approaching. “If it isn’t the Lord High Chancellor himself,” he said. “Good evening, Your Lordship. How lovely of you to grace us with your presence.”

A few of the other couriers laughed. Others just glared at Largo. He’d been through enough for one day and wondered if he could leave through the back exit and avoid Andrzej’s nonsense. However, he’d already been called out in front of the couriers and knew there would be trouble if he didn’t answer in kind. There was nothing to do but speak as if he were still in the Green. “What’s up your ass, my fine brother?”

“You. You’re what’s up my ass,” Andrzej said coldly. He was five years older and a head taller than any of the other couriers. “König isn’t gone a day and you’re in there mincing around with high and mighty Branca, trying to steal his job.”

“I didn’t steal anything. When Branca gave me the job I was as surprised as anyone. I was even late this morning, for shit’s sake.”

Parvulesco grabbed Weimer’s flask, took a quick drink, and tossed it back to him. Weimer, whose right arm was a simple wood-and-steel prosthetic, fumbled with it in the air and finally dropped it. He claimed to have lost his real arm in the early days of the war, but no one believed him. When asked where he had served, he could never name the same company or regiment twice. Plus, he didn’t have a Red Eagle medal, something all wounded soldiers received. Worse, while drunk one night, Andrzej had told the others that someone else’s name was carved into the underside of the prosthetic, all but saying that Weimer had stolen it. It had been an amusing story at the time, but Largo had never trusted either of them since.

“König is going to kick the guts out of you when he gets back,” Andrzej said. “We’ve all seen you brown-nosing Branca. He’ll know you stabbed him in the back.”

“Like Weimer knows you told us about his arm?”

Weimer lowered the flask. “What did he tell you?”

“Nothing,” said Andrzej. Then to Largo, “Shut up.”

Largo wondered if this was why Branca had warned him that morning. The problem was that if he was attacked, he knew he couldn’t use the knife. It would be his word against Andrzej’s and he wasn’t sure how many of the other couriers would side with him against the bully. Besides, he had to admit that after today, more than ever, he was afraid for both his safety and his job. Still, Largo was pleased by the image of Andrzej on the business end of his brass knuckles, even if he knew that he couldn’t do anything but reflect the bastard’s arrogance back at him.

Luckily, he didn’t even have to do that.