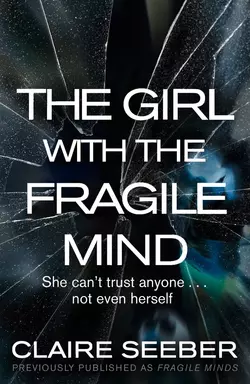

The Girl with the Fragile Mind

Claire Seeber

SHE CAN’T TRUST ANYONE . . . NOT EVEN HERSELF'I think I might have done something bad.’When a bomb explodes in the heart of London, the police suspect a terrorist group. But the pieces don't fit together and they struggle to find any suspects.Still recovering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after a terrible tragedy, Claudie fears that her recent black-outs are a sign that her symptoms are returning. So when her friend Tessa dies in the explosion, Claudie is gripped by the inexplicable certainty that she is involved in some way – if only she could remember.Can Claudie get to the heart of what is real and what isn't . . . before something truly terrifying happens again?

Claire Seeber

The Girl with The Fragile Mind

Copyright

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain as Fragile Minds by HarperCollins Publishers, London, 2011

This edition published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2015

Copyright © Claire Seeber 2011

Claire Seeber asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

ISBN-13: 9781847562074

Ebook edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780008142421

Version: 2016-03-12

Praise for Claire Seeber

‘An intense psychological thriller’

OK!

‘An absorbing page-turner’

Closer

‘A powerful and sensitive treatment of every parent’s worst nightmare’

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Dedication

For Fenn and Raffi, again.

All my love, always.

And in memory of my beloved grandpa,

Roy Livingstone Holmes.

Lemonade lollies forever.

Epigraph

‘Whoever takes one life, takes the world entire,

Whoever saves a single life, saves the world entire.’

The Talmud

‘No rescue? What, a prisoner? I am even

The natural fool of fortune. Use me well.’

King Lear, Act IV, Scene VI

Contents

Cover (#u09222f91-dff7-573e-a593-c7771ec5c742)

Title Page (#u94f77b6c-64cb-59da-a99d-4e71e0c88803)

Copyright (#ue59bfea4-968e-53f3-997a-7ea83638cc64)

Praise (#u927b3e52-1a57-5041-a9eb-2a28da6083e2)

Dedication (#u930e15d5-c8f3-5dfc-9c19-354783695ce0)

Epigraph (#udb9bda25-af33-5397-b896-2516b6152b62)

Prologue (#ud5f9ae85-7e90-5089-a277-38c2b2969eac)

Thursday 13th July Claudie (#u59dcc823-58ef-5b3d-be7d-ce3487e18568)

Thursday 13th July Silver (#u28759475-ad0a-55bf-8ea5-0d87086599a5)

Thursday 13th July Claudie (#u86ea066f-0352-56c7-a3c4-214f80119b22)

Friday 14th July Claudie (#u95868311-dc4a-586b-8f74-b4b72f06db03)

Friday 14th July Kenton (#u1179c2cc-73b3-539b-98a6-5275b8e27257)

Friday 14th July Claudie (#u4bfed80a-d966-58f5-b4d3-1218271a7c5e)

Friday 14th July Kenton (#ueb2add37-bcad-58b1-a47b-8addbe8b1d03)

Friday 14th July Claudie (#u58ef67b8-fdca-50c1-ad58-e8a695b467a0)

Friday 14th July Silver (#ub794daa2-25f3-53dd-81af-2b78dd939cc8)

Friday 14th July Claudie (#u71811491-5bde-52b1-bbf2-5cf4878305f5)

Friday 14th July Kenton (#ud2e20582-d634-5412-ad19-f00a2360106c)

Monday 17th July Claudie (#udd054dfc-c2b0-53ad-8729-0eb28b720fba)

Tuesday 18th July Silver (#ue01af19c-e5b9-5651-b042-5b08cb752cc0)

Tuesday 18th July Claudie (#u81b6e575-965b-51f5-a262-48da0e64f1cb)

Tuesday 18th July Kenton (#u539d80fb-573a-52be-bfce-c56797085fb2)

Tuesday 18th July Claudie (#ucd27f393-b443-502f-8bff-dd0b896a24a4)

Tuesday 18th July Silver (#u89084143-6d34-5a3e-821e-76acefb7501b)

Tuesday 18th July Claudie (#uea6d90b4-0555-51b5-90f6-f3418f099bd2)

Wednesday 19th July Silver (#uddc67cc2-3ee0-52c5-9118-ec3949d26426)

Wednesday 19th July Claudie (#u0f255e9f-a4d8-5ecb-be56-75f42c333bec)

Wednesday 19th July Silver (#u5a116a21-ccbd-5a99-a099-6116096d4287)

Wednesday 19th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 19th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 19th July Lana (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 20th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 20th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 20th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 20th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 20th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 21st July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 23rd July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 23rd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 22nd July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 23rd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 23rd July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 23rd July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 24th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 24th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday Night, 13th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 14th July: The Berkeley Square Bomb Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Kenton (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th July Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

Claudie (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for an exclusive short story by Claire Seeber (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books by Claire Seeber (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

There are plenty of beginnings, but only one end to my story.

At the police station in the small country town, they brought me tea and toast, but I didn’t touch it; I pushed it away. I didn’t trust them. Any of them, any more.

My feet were cut and bleeding; I didn’t care. They matched my sore hands. In my head I was still running, and the road was cold and rough beneath my naked feet and I didn’t care. The pain pushed me on. I was a streak of white light in a black surround, and then you were beside me, only you couldn’t keep up, so I leant down and carried you, light as thistledown, in my arms. No one could stop us; I would run and run and run—

Someone was behind me. I could feel my heart beating, I could hear the blood thumping in my ears, I could feel the breath squeezing through my ribs and out of me; I couldn’t outrun them.

My feet were hurting badly now and I no longer felt invincible, I could hear the sobs pushing out of me as the car slowed and a blue light flickered across the road between the sand dunes, and the sea hissed to the left of me: ‘Don’t stop, Claudie, or they will get you.’ But I was weak now, too weak—

The man held my arm gently. He was wearing a uniform and he said, ‘Are you all right, love, you’re freezing.’ And he led me to the car with the blue light on top, and made me sit in the back.

And then they brought me to the building in the town, and said another man, a man they called Silver, wanted to talk to me.

I didn’t give him time to sit when he came in. I had waited too long already.

‘Something’s not right,’ I said, too fast, almost before he came through the door.

He leant on the wall in his shirtsleeves, hands in his pockets, and looked down at me. His expression was quizzical but I was relieved that he didn’t look amused. He looked tired, perhaps, but not amused.

‘I see. Are you all right though, Claudie?’

I kept my hands in my lap beneath the table, where he couldn’t see me tearing at my own skin.

‘I – I’m not sure.’ I eyed the toast warily. ‘I think I will be OK.’ If only they’d stop poisoning me.

He sat now, directly opposite me. There was a black tape recorder on the table between us, but he didn’t switch it on. His eyes were a little hooded; they narrowed slightly as he studied my face.

‘Have we met before?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘You look a little familiar.’

I shook my head. There was a pen on the table; he turned it round neatly, and then gave me a slight smile. ‘So, Claudie. In your own time, I need you to tell me why you’re here. How you came to be all the way out here. Did someone bring you?’

‘Yes,’ I nodded. ‘And something’s not right,’ I repeated, slowly this time. I could feel the shiny crescent moon of skin missing from my thumb where I’d stripped it raw.

‘What?’ he said now. His accent was Northern. ‘What’s not right?’

‘I can’t – it’s hard to explain.’

We locked eyes. Still he did not condescend to me; he didn’t look at me as if I was mad. He just waited, dug in his trouser pocket for something.

‘That sounds stupid, I know.’ I was trying to order my mind. My thumb throbbed. ‘I mean, I can’t quite put my finger on it.’

‘On what?’ He was handsome. No, not handsome even, kind of … debonair. Like he’d stepped from a Fred and Ginger film; his cuffs so white they almost shone.

‘I think I might have done something bad. The Friday before last.’

‘What kind of bad?’ he asked. Long fingers on gum; waiting to unwrap it. He sat back in his chair and looked at me patiently. I could smell his aftershave. Lemony.

‘Very bad,’ I muttered.

‘Do you know my name?’ he asked.

He felt me falter. I shook my head.

‘It’s DCI Silver.’ It was an inducement. ‘Joe Silver.’

A short, stocky woman walked into the room now and stood behind him. She smiled at me, a kind, reassuring smile. I recognised her, I realised. I’d met her before. A woman with funny coloured hair.

‘And what happened to your face, Claudie?’

Automatically I raised my hand to my cheek. ‘Berkeley Square.’

‘Berkeley Square?’ He sat up straighter. ‘The explosion?’

I nodded.

‘OK, Claudie.’ He flicked the gum away into the wastepaper basket and smiled again. He must have kids, I thought. He is used to waiting with infinite patience. His teeth were very straight, almost as white as his cuffs. ‘Why don’t you start from the beginning? Who brought you all the way out here?’

‘I think I might have done something terrible,’ I repeated. I took a gulp of air: I met his eyes this time. ‘I think – I think I might have killed a lot of people.’

THURSDAY 13TH JULY CLAUDIE

It was such an ordinary morning. Afterwards that seemed the most marked thing about everything that followed, that it started as any day that encapsulates absolute normality. Not particularly sunny, not particularly cold – a day on which people get up and eat toast, choose underwear and shoes; argue about walking the dog or taking the bin out, kiss their children and their partners goodbye; catch the 8.13, jostle for space with the same anonymous faces they jostle with every day. A day on which people go about things in exactly the same way as always; not realising life might be about to change forever.

And for me, it was one of the all right days. A day when I had managed to roll out of bed, step out of the house; walk, talk and function. Not one of the pole-axed days. Not one of the splitting days.

One of the all right days.

I got to work early because the yoga teacher hadn’t turned up at the Centre. I walked through the back streets of Marylebone, enjoying the relative quiet of Oxford Street, free of the tourists and maddened shoppers, at one with the street cleaners and the other Londoners not yet soiled for the day by the city.

I wandered up the front stairs of the Royal Ballet Academy in Berkeley Square, between the great white pillars and the huge arched windows, soaking in the ambience of the old building. I loved my job and the Academy was grand enough to warrant its distinguished title, training some of the greatest ballet talent in Europe.

‘The Bolshoi are in.’ My colleague Leila shot past me on the stairs, following a gaggle of chattering students. I caught up with them at the glass wall to watch a little of the guest stars’ technical demonstration, watching a sturdy Russian male fling the Academy’s young Irish ballerina Sorcha into the air during the Sleeping Beauty pas de deux. By the rapt look on the couple’s faces, I guessed it might not be all they’d be demonstrating later.

A small, dark first-year student called Anita sat against the back wall, limbering up, watching Sorcha like a hawk. One of Tessa’s protégées, I had yet to see her dance, or treat her for any sort of injury myself, but she had a rather glowering intensity that I found unattractive. Her face in repose was simply a downturned mouth. And recently, I’d noticed that she’d begun to trail Tessa in a way that verged on pathological.

‘He’s gorgeous,’ a girl in a blue leotard breathed, fugging up the glass, ‘and look at his arms. His lifts are effortless.’

‘He can lift me,’ her plain friend said, sticking her bony chest out. ‘Any way he wants.’ They both giggled.

Down in the office, Mason was as always safely ensconced behind her desk, keeper of the back-room. God only knew where she had found this morning’s ensemble: a kaftan in vivid black and orange swirls that entirely swamped her skinny frame. I wondered, not for the first time, if anyone else ever thought she looked like a female version of the transvestite potter Grayson Perry.

‘You’re early,’ Mason said. The sleeve of her kaftan trailed patiently after the raddled hand flying across the keyboard. ‘As the esteemed Mr Franklin once said: “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”’

‘Indeed,’ I grinned. Mason’s ability to quote at long and tedious length was legendary, though I was sure she made half of them up. ‘Let’s hope he was right.’

‘Tessa’s looking for you.’ She glanced up, one pencilled eyebrow disappearing into her glossy fringe. ‘Seems a little – anxious.’

As I was changing into my tunic in the staff changing room, Tessa arrived, slightly breathless, her limp a little more pronounced than usual. She looked oddly harried and her spotted hairband was tied too loosely so wisps of fair hair were escaping.

‘Morning. Everything OK?’ I noted the roses of high colour on her cheeks. ‘Mason said you were after me.’

‘I – Claudie. I must just catch my breath. Sorry,’ she mumbled. She sat on the bench beside me, clutching her tortoiseshell walking stick.

‘I’ve got that book you wanted to borrow, by the way,’ I said, ‘the Elizabeth David. Don’t let me forget to give it to you now I’ve—’

Tessa startled me by grasping my hand so hard it made me wince. Her breathing seemed very fast as she peered over my shoulder, dropping her voice.

‘I need to talk to you, Claudie.’ The Australian accent she normally fought to hide was broad today, and something in her tone made me frown. I’d never seen Tessa so tense, although her behaviour in the past few weeks had seemed different, somehow; erratic, even. Recently her star as the Academy’s top teacher had slid into the descendant after an ugly incident involving an irate mother and her hysterical daughter; the board were looking into it and Tessa refused to talk about it, but I’d put her unease down to that. ‘In private, I mean.’ She looked over my shoulder as if she was expecting someone to materialise.

‘I’ve got a full schedule this morning,’ I was apologetic. ‘They’re all overdoing it at the moment apparently, poor loves. End of term in sight, I suppose. Can we talk later?’

‘Lunchtime?’

‘I’m – I’ve got an appointment at lunch.’ I grimaced. I was aware we hadn’t spent much time together recently. ‘Sorry. I can’t really – how about tea this afternoon?’

‘I’m not sure I can wait.’ Tessa was blinking strangely, moving to the door. ‘I’m – I really need to—’ she trailed off as she pushed the door ajar and scanned the corridor.

‘What’s wrong, Tessa?’ I followed her gaze; through the crack, I glimpsed Anita Stuart trailing Sorcha and the Bolshoi dancers up the stairs to the girls’ changing rooms.

‘It’s just – I’ve been – oh God.’ Tessa let the door swing to, biting her own fist. ‘I really wanted to tell you before—’

In a blast of surrealist kaftan, Mason arrived, music swelling and dying down again as she opened and shut the door. Behind her in the corridor I saw my first student waiting outside my room.

‘Ladies. Don’t mind me.’ Mason began sticking up audition notices onto the central notice-board. I knew she was all ears.

I looked back at Tessa; her hands fluttered at her sides like long white butterflies.

‘Look, can we grab a coffee at eleven?’ I suggested. ‘I’ll have about fifteen minutes between sessions.’

‘Yes please.’ Tessa tried to smile, but I thought I saw her bottom lip tremble slightly. ‘Oh, and can you shove my kitbag in your locker? I’ve mislaid my keys. Stupid, really.’

‘Of course.’

Her light eyes were over-bright as I took the bag from her, her mascara oddly clumpy for someone usually fastidious. I felt torn, but Billy McCorkdale was leaning against the wall, only eighteen and already all testosterone and attitude. Starting treatments late meant the whole day became a logistical nightmare.

‘Problem?’ Mason perked up. ‘Can I assist?’

Tessa tried that smile again. ‘No, no.’

Later, that smile haunted me.

Later, my abiding memory was that it was one of fear.

THURSDAY 13TH JULY SILVER

DCI Joseph Silver was just about to step into the shower at the sports club when his work mobile rang. He felt particularly disgusting at this moment, sweat dripping down his back, his t-shirt saturated, having just thrashed it out with his colleague DI Lonsdale in a match that was ostensibly part of the station tournament, but was really about Serious Crime vs Homicide. And in fact, even more so in this instance, about proving the North/South divide was well and truly alive and breathing. Lonsdale stood for everything Silver despised in the force; a supercilious Southern bastard with a daft goatee who drove a Volvo, wore ever-clean Timberlands, and bleated about his paternity rights every other day.

Silver ignored the phone. It rang off, and then immediately started again.

He swore quietly and fumbled in the pocket of his neatly folded trousers, tentatively holding the phone to his sweaty ear, trying not to soak it. ‘Silver.’

‘Guv.’ It was DS Lorraine Kenton, the newest member of his team. ‘Sorry to bother you, but Malloy’s on the rampage.’

‘Go on.’ Sweat trickled down his cheek and dripped onto the filthy floor. Silver suppressed a fastidious shudder. He might have just proven that the North bore tough and tenacious sportsmen who were unafraid to slam their own bodies into brick walls in the name of gamesmanship, but he was also the same copper who couldn’t abide mess and dirt. OCD, his ex-wife Lana called it, invariably to wind him up, though she wasn’t too far behind him in the cleanliness next to Godliness stakes. Not that either of them had ever followed the God bit – but their house had been truly sparkling.

‘Just a quick one.’ Kenton cleared her throat. ‘Missing girl, Misty Jones. Malloy wants to use the GMTV and Crime Live! appeal tomorrow morning for her.’

‘Why?’ Silver tasted the salt on his own lips. ‘It’s meant to be for that Down’s Syndrome lad.’

‘Bobby Elwood. I know. I did say that. But the thing is,’ Kenton cleared her throat again, a habit Silver was beginning to recognise as a nervous one, ‘Malloy thinks Misty Jones is more—’

‘Don’t tell me – photogenic. Pretty, is she?’ Which meant his boss thought they’d get more response to the appeal, which meant a quicker result, which meant better statistics. ‘Brilliant.’

‘Is that – are you being serious, sir?’ Kenton asked nervously.

‘I’m being entirely sarcastic, Kenton. Which is the lowest form of wit, someone once told me. Poor retarded lad traded in for pretty lass. Have we even looked into the case properly?’

‘Not really. Flatmate reported it. Can’t trace the family.’

‘But it’s a fait accompli, as those learned French say. Doubt I have much choice, do I?’

Kenton looked at her email inbox, where the GMTV producer had just mailed her to thank her for the Jpeg of the missing girl, and asking for a few more details. Favourite pet, younger siblings, anything that would help the nation’s heart bleed. None of which Kenton could immediately answer.

‘Er—’

‘That was rhetorical, Kenton. Who the hell is Misty Jones anyway?’ Down in the shower room, Silver could see Lonsdale approaching. He wanted to get into the shower before his competitor. He didn’t fancy chit-chat from a cheating Southern bastard with a wispy chin who’d quibbled over every point.

‘Look, if Malloy’s given you the word, then do it, kiddo. We’ll have a chat in the morning. Or at the weekend, any road. I’m off tomorrow.’

Reason not to be cheerful no. 87. Silver shoved his phone back into his sports bag and made for the shower. He might just have won, but he had no desire to engage in back-slapping camaraderie with a secretly seething colleague, or be invited to go for a drink, which he’d only have to turn down. He was knackered, and his mood was dark. Bed and solitude called.

THURSDAY 13TH JULY CLAUDIE

Tessa didn’t show up at eleven and by lunchtime, I’d been distracted by a first-year student falling in class and a possible elbow fracture. I forgot about my friend and her earlier anxiety as I hastened to sort the subsequent hospital referral, and then to reach my own appointment in Harley Street.

Rushing back to the Academy at the end of the lunch hour, almost late for my next student, I found Anita Stuart lurking outside my room, her feet sketching movement on the spot as someone down the hall played the opening suite from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet score over and over.

‘Have you seen Tessa?’ she demanded, fiddling with a small silver dove on a chain round her neck. She was a little surly, as ever, and her rather lazy left eye gave her an unfortunate lopsided look.

‘No, ’fraid not.’ I unlocked my door. ‘She’s probably in class, no?’

Anita was clutching something, a pamphlet of some description. I caught the words ‘Redemption’ and ‘Light’ before she shoved it in her pocket.

‘She’s not,’ Anita scowled. She smelt odd; it seemed familiar but I couldn’t place the scent. ‘I thought she might be having lunch with you.’

‘Sorry. Can’t help.’ I let myself into my room, relieved to get away from the scowl and the odd smell. But Anita was too fast.

‘What’s she said to you?’ She stuck her foot in the door so I couldn’t shut it behind me.

‘About what?’ I frowned.

‘About—’ She stopped and stared at me. Thought better of it, perhaps. ‘Never mind. But if you see Tessa, tell her I’m looking for her.’

‘Yes, Madam,’ I muttered at her departing back. What an unpleasant girl, I thought, and closed my door behind her.

At five, as I was signing out, I had a quick look for Tessa, but she wasn’t in class or in the staffroom. I needed some fresh air now, my back was aching from standing for so long, and I was dying for a cigarette. I searched my bag for a nicotine patch, applying it with a sense of slightly defeated relief.

‘Seen Tessa?’ I asked Leila, who hadn’t, and Mason, who immediately raised her non-existent eyebrows in an entirely suggestive way.

‘What?’

‘She was ever so stressed. I heard her on the phone. I was trying not to listen but—’ Mason’s letterbox mouth snapped shut dramatically. ‘Well.’

‘Your speciality, not listening.’ Leila winked at me. ‘Walls have ears, eh, Mason?’

‘Let’s just say Tessa was more than a little fraught. She was meant to be covering Eduardo’s 4 p.m. but she made some sort of excuse and just left. Jenny had to do it.’

Leila and I exchanged glances. Mason was unperturbed.

‘She’s not best pleased, shall we say. Jenny. Still, “The busy man is troubled with but one devil, the idle man by a thousand.”’

‘Oh dear.’ I gathered my things, feeling guilty I hadn’t found Tessa earlier. ‘I hope she’s OK.’

‘Oh, Claudie,’ Mason barked as I opened the door to leave. ‘I completely forgot. She left you a note.’ As she bent to retrieve it from the pile on her desk, Mason knocked over her coffee, soaking everything with dark brown liquid. ‘Oh, damn and blast.’

After a bit of wrangling, Mason passed me the soggy bit of paper, but it was almost pulp already. I could just make out the words ‘Take’ and ‘the necklace’. The last word in the paragraph looked like it was possibly ‘Sorry’ with a big curly y.

I held it to the light but it was no good, it was illegible. I balled the note, tossing it in the bin. From the set of Mason’s expectant head, I could tell she had read it, she was dying to be asked; but I wouldn’t give her the satisfaction. If it was important, Tessa would call me, I guessed. ‘See you guys tomorrow.’

‘Ta ta for now,’ Mason sniffed. ‘Don’t do anything I wouldn’t with that gorgeous Rafe. I know what MPs are like.’

‘Leaves me wide open then,’ I grinned at her, shouldering my bag, and left.

The summer afternoon was warm and the air outside seemed to almost shimmer. I suddenly felt more cheerful about life, almost euphoric even. Things were going to get better. They simply had to.

I had no idea of the level of my delusion.

But on the bus to meet Rafe, stuck at red lights, I felt less than euphoric and increasingly racked by a headache. I stared out at an Evening Standard billboard on the street which read ‘Dancer, 20, Missing or Dead?’; but the words moved up and down with alarming speed as I tried to focus.

Disoriented, I was jolted into a memory that terrified me. I felt like I had last year; my self fracturing into pieces – but it couldn’t be happening again – could it? I was over the worst, surely? I leant against the window, my head pounding so badly now I thought I might actually throw up, and I thought vaguely that maybe I should get off the bus before it was too late – only the idea of walking right now seemed a little like scaling Mount Everest. I looked down onto the pavement, onto the worker ants of London, and my phone was ringing in my bag. I tried to pull it out, the flickering lights in front of my burning eyes bewildering me until I felt like I was losing consciousness.

I woke in the dark, almost dribbling, absolutely freezing, my hands curled round my bag strap so tightly I had to fight to unfurl them. I could hear voices, and then Rafe was there, peering down at me, saying, ‘Oh my God, Claudie, what’s happened?’ And I found I could hardly speak, I was so disoriented, but I managed to croak something about my head, and he was saying, ‘Oh Christ, you’re frozen, how long have you been here?’ and practically carrying me up the few stairs to his flat. He gave me a warm drink of something tasteless, and laid me down on his sofa with a cashmere blanket – it was so warm and homely that I drifted off again.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

I came to in the early hours caught in the desperate state between sleep and consciousness; hearing frantic voices whispering in the dark, a woman’s voice too now, and I thought perhaps it was Tessa, and then I realised I was dreaming.

When I woke properly about six, Rafe had already gone. He was a gym addict, and there was a note, telling me to help myself to anything I wanted, and that he’d see me later, and he hoped I was feeling better.

The headache had gone, but I didn’t feel better. I just felt frightened. I’d lost a few hours from last night; I remembered leaving work, being on the bus and then – what? Waking in Rafe’s porch; being carried into the flat. An overwhelming sense of anxiety pulsed through me. Images from yesterday flickered through my mind, like a camera shutter opening and closing too fast. I sat on the sofa, my head in my hands, and tried to breathe.

Was it happening again?

I washed my face and hands beneath the expensive lighting in Rafe’s stark bathroom and, trying to calm my tousled hair, I opened the medicine cabinet above the basin, looking for what Rafe called ‘product’. A packet of Well Woman tablets fell out. I picked them up, frowning. Next to them, a pink electric toothbrush, and a jar of Clinique night cream.

I shut the cabinet door, and walked into his bedroom. It all looked the same as ever, until I opened the drawers by the side of the bed. There was a pale blue hairband and some expensive hand cream.

It underlined something I had been avoiding … that Rafe and I were really only a stopgap. Meeting by chance at the Sadler’s Wells charity do in January, it had always felt a little like I was one of his pet projects; that we were keeping each other warm on cold winter nights.

But now it was summer.

Grabbing my stuff, I ran down the stairs and buzzed myself out, the fortress door slamming behind me. I stood at the top of the shiny steps to the street. A milk float trundled slowly down the deserted road, and a ginger cat cleaned its ears discreetly as it sat beneath the frothy mimosa tree; it looked at me with disdain and then carried on licking. And I remembered Tessa’s soaked and illegible note in my hand yesterday afternoon and I had this sudden overriding feeling that I should be somewhere, and I felt a rising panic, because I just didn’t know where.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY KENTON

How the hell she had ended up having to do this alone, she would never know. Cursing quietly, DS Lorraine Kenton backed the car into the small space, knocked the adjacent Audi’s mirror and then looked around guiltily to see if anyone had noticed. It had taken over half an hour to find a parking space because the bloody NCP was shut for some reason, and she was seriously over-tired and crochety. She’d slept badly because all night she’d kept dreaming that she’d forgotten what she was meant to say in the TV studio and no one would tell her the lines so she just sat frozen in fear on the famous cream sofa of Crime Live!, opposite the immaculate ice-maiden presenter who stared at her blankly.

At six, Kenton had woken with relief, before realising with horror she really did have to go on TV today. In an effort to rouse herself, she’d drunk too much black coffee in a foolish attempt to get those little grey cells working and thrown half a mug of it down her new white shirt, which meant she had to plump for the crumpled stripy one. She didn’t have time to iron it because she’d nicked the fuse out of the plug last week for her hairdryer, which had been unused for at least two years prior to her first date, on the Southbank, with Alison from the dating website Guardian Soulmates. Now the only consequence of all that coffee was a mismatched outfit and a horribly pounding heart, her brain exactly as slow and sludge-like as when she’d first woken.

The television studio was on a small side street off Berkeley Square. Kenton checked the A-Z and, grabbing her jacket from the back seat hoping it would cover the crumpled stripes, wondered for at least the forty-eighth time this morning why the hell she’d volunteered to replace Gill McCarthy from the Press Office when she had become ‘unavailable’ at the last minute yesterday evening (for unavailable read: had just found out her boyfriend in Organised Crime was screwing McCarthy’s number two, Jo Reid, who wore a wanton look, too much red lipstick and her dresses practically slashed to the waist. Obvious, maybe, but Kenton could definitely see her appeal).

Her phone rang. Her pounding heart slowed and sank. It was DI Craven.

‘I’ll meet you there, pet,’ he said. ‘At Audley Street. Running slightly late.’

‘Really? I thought I was—’ Kenton collected herself, ‘I didn’t realise you were coming too.’

‘Boss thought you might fuck it up,’ he said smugly, and hung up.

Kenton counted to ten slowly and then dug her iPod out to begin the walk west, shuffling the wheel for the Meditation CD Alison had rather shyly suggested she try for stress.

‘Breathe deeply. Now imagine yourself in a safe, secure place. Somewhere you are entirely comfortable,’ the man’s voice droned unconvincingly. ‘Perhaps you are in a childhood—’

Someone pushed Kenton so violently from behind that she stumbled, just righting herself in time before she fell; her iPod hitting the pavement hard.

Before she could pick it up, she was pushed again. Heart racing, she turned to see who her attacker was, but they had run on. There was some sort of commotion on the far side of the square behind her, beside the big Swiss bank – but she was too far away to see exactly what it was; the railings round the green blocked her view, so she could only see the edge of the building site beside the bank. About fifty metres away, a woman in a burqa stood on the edge of the pavement, about to push a buggy across the road. Now the woman began to run towards the group of people at the bus stop.

As Kenton neared, adrenaline flooding her veins now, she could hear shouting and then another, more eerie noise: a high-pitched wail not unlike the keening of the bereaved at an Arabic funeral.

A bus pulled in, blocking her view again; and then a woman was screaming and shouting something unintelligible and Kenton saw people on the bus look out, and then stand up, a man pointing, pointing out of the far window and then—

All was chaos and noise and white, exploding light.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

I stood on the quiet street outside Rafe’s flat. The church clock on the green struck seven, and a double decker slid into place at the bus stop in front of me. Unthinking, I climbed on. I didn’t check the destination, I just slapped my Oyster card on the reader like it was a dead fish, and I sat in the first seat I came to.

I kept thinking I need to be somewhere only I couldn’t seem to collect my thoughts; and when I did manage to assemble them a little, I found I was thinking of Ned, and then of Will. I fiddled anxiously with my locket, realising I had a sudden urge to see my husband. Oh the sweet irony: an irony Will would not thank me for.

The old lady beside me smelt high, as if she’d been ripened especially for months. She kept grumbling about the driver, on and on she droned. ‘He’s trying to scare us, that lad, you mark my words, it’s because they don’t learn to drive here, they learn in Africa, too many holes in the roads, those jigaboos.’ After a few minutes, I said, ‘I’m afraid I don’t share your horrible opinions,’ and I moved to the back, stumbling against the other commuters who stared at me with empty eyes.

We reached Russell Square. Tessa; that was it; that was what I had to do. I changed buses and boarded a new one. It seemed to take forever to reach Oxford Street where we became one in a line of nose to tail buses, crawling at tortoise pace – something was holding us up, but we couldn’t see what; until eventually I knew, I knew I had to get off the bus NOW. I began to smash on the doors until the other passengers stepped back in fear, until the driver thought I was truly mad, and gave in, and let me off.

And I ran, ran, ran towards Berkeley Square.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY KENTON

Somehow the bus protected her. Forever after she would be grateful; she would look on London’s famous red double decker as some kind of lucky charm; some kind of talisman to her.

Instinctively, Kenton had hit the floor when the explosion ripped through the north side of the square. She had lain motionless on the pavement with her hands over her head for a minute or two, until the noise settled, the rumble stopped, and there was quiet across the square. A strange pocket of silence in the city, broken only by the incongruous sound of birdsong.

And then a new noise began. Now it was the alarms that filled the air: the cars, the shops and flats; the electrics triggered by the huge explosion. There was thick dust swirling in the air, making Kenton cough as she thought absently of 9/11 and the survivors staggering about covered in white like ash-covered ghosts.

She tasted it in her mouth and spat a few times, trying to find some moisture. She stood slowly, trembling, and began to walk towards the mutilated bus that had inclined fatally to the right, towards the crying and the wailing – towards the devastation, glass crunching underfoot. Her inclination might be to run back, but she knew it was her duty to go forward. She stopped for a moment, and breathed deeply and then pulled her phone from her pocket to ring for help. Afterwards, she couldn’t remember the conversation, or whom she spoke to, but soon after, the air was filled with police sirens.

Nothing could prepare her for what she was about to witness. In her mind’s eye, she imagined her late mother, smiling with encouragement from her usual place at the kitchen sink. ‘You can do it, Lorraine,’ she heard her mother say, snapping off her yellow Marigolds. ‘That’s my girl.’

The smell of burning filled the air as Kenton stepped over something, walking towards the bank in the far right corner. She looked again: it was a hand. She retched into the gutter; the pavement nearest the bank was red with blood. She held her phone tighter. She looked for the first ambulance. She saw another mutilated body. She kept breathing. She didn’t retch this time.

A blonde woman was lying on her back, face bloodied and blackened, one foot extended gracefully; glassy eyes open. Dead. Most definitely dead. Another woman lay at a right angle to her; this one was alive, whimpering in terror and pain. Kenton knelt beside her gratefully.

‘What’s your name?’ she asked.

‘Maeve,’ the woman whispered. Her face was entirely drained of colour. ‘Maeve O’Connor.’

‘You’re going to be all right, Maeve.’ Kenton had no idea if the woman would be all right but it seemed the thing to say. ‘Where does it hurt?’

Desperately Kenton looked again for an ambulance. Where the hell were they? She held the woman’s hand, and she tied her belt round the woman’s bleeding leg. Then she spoke to a young man; a builder from the neighbouring site. He seemed delirious, worried he’d lost his hard hat; his face was speckled with shrapnel cuts. Other people were coming now; moving amongst the dead and injured. Kenton looked up. The front and side of the Hoffman Bank were gone; it looked naked, like a half-dressed man. The building site beside it had lost its front hoarding; gentle flames licked the side of it. The dust flew in the air.

When the ambulances finally arrived, and the police cars and fire engines, and there were no injured left to talk or tend to, Kenton sat on the kerb in the debris until she was moved off, like any other member of the public, and after a while, she wept.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

I came to in St Thomas’s A&E, on a bed in a curtained cubicle, with no memory of what or who had brought me here. Concussion they said, but I’d be fine. I’d collided with a cyclist ten minutes – quite literally – after the ‘major incident’ that had apparently just shut central London. I couldn’t remember any of it, but the cyclist lay in the next cubicle with a twisted knee. My head was hurting even more than it had last night, and I kept trying to say I didn’t know what had happened, but they thought that was normal. I wasn’t sure they were listening; they kept saying it was just shock. And the pain, it was different to last night; a dull throb, and the nice nurse who had treated me delivered me to the waiting area, and patted me on the head like a well-behaved puppy. She propped me up with a print-out on concussion and a vial of painkillers, and told me to hang on, someone would be here soon.

‘You’ll be all right,’ she said, in an accent that was probably Nigerian. Her bobbed wig was slightly askew; I wanted to straighten it. ‘You got a hard head, child. Praise the Lord you were not nearer the incident.’ She glanced up to where God obviously resided. ‘Go well, Claudia. And don’t forget to ring through for your results in a few days.’

The consultant’s single concession to my confusion and mention of blinding migraines had been to give me a blood test.

‘The confusion is probably partial concussion.’ He looked about ten, slightly nervous, hardly old enough to have left school, and his ears protruded at alarming right angles. ‘Which is what you must watch for now. Tell your family, OK? Re: the migraines, well, I haven’t got time to do a full set of bloods now,’ he filled in a form, which is what he had to find time for, ‘we’re too stretched. But let me just do a test for your hormone levels. It could explain a lot. We’ll have to wait for the results of course.’

And I hadn’t been in a hospital since that terrible day two years ago, the day that Ned had finally given up on life; and it was even worse than I remembered. There was an air of flattened panic throughout the building and everyone who entered through the sliding doors seemed almost shifty; they would check the room quickly to see who else was here as if they were casing the joint: the walking wounded, the traumatised. A constant stream of ambulances arrived in the bay outside the doors; the seriously injured were whisked somewhere we were not allowed. After a while we all averted our eyes because it was simply too much.

And the sirens; the sirens were a constant chorus of the morning, screaming through the stultifying air. The doctors and nurses walked with a different tread, faster, and they seemed different to how they would be in a normal Emergency Room; quicker, more energised. Frightened.

About an hour after I had been led to that shiny orange chair, my younger sister trotted through the doors at a fair pace, like a circus pony, anxious to perform.

‘Oh, thank God!’ she said. She was almost breathless with fear and excitement, her fair hair tumbling around her broad, friendly face, only missing its circus plume. ‘Are you OK? Isn’t this awful?’

‘Thanks for coming, Nat.’ Gingerly I stood, clutching my medication and my bag. ‘I know you’re busy.’

‘Of course I’d come.’ Her face was flushed and she had put her pink lipstick on crooked. ‘Who else would? Though I didn’t want to bring Ella into the zone, you know, the danger zone,’ and I almost laughed. ‘I left her with Glynnis next door. Such a nice woman. She understood.’

What exactly Glynnis had understood, I wasn’t sure.

‘We’d better get out of here quickly.’

‘It’s not Afghanistan you know,’ I said, but perhaps it was; perhaps this crisis that I did not understand yet was the start of something truly terrible. Natalie rolled her eyes, guiding me towards the car park now.

‘Well, who knows what it is yet, Claudia? They haven’t said. They’re saying nothing on the radio, just that it was an explosion, and don’t go into town. The traffic’s appalling. Oh God I was so worried, it’s right beside your work isn’t it? Thank goodness it happened so early.’

‘I should have been there,’ I said. I should have been there, I should have been there. ‘I was on my way in.’

‘You should? Oh my goodness, Claudia!’ she exhaled noisily. ‘You must be in shock. I would be. Your poor face. I’ve got a thermos of tea in the car.’ My ever-efficient little sister, the prizewinning Girl Guide, the soloist chorister, the parent rep. ‘You know, I can’t stop watching the news. It’s so horrific. We need to ring Mum. Let’s get home.’

FRIDAY 14TH JULY SILVER

Despite it being his day off, Joseph Silver woke at 5.15 a.m. Despite or because of … Habit was a forceful thing, he thought sourly, burying his head beneath the pillow. Silver loathed his days off, hated having time to think; he would happily spend the whole time unconscious until it was time to go to work again.

Naturally this morning, try as he might, sleep eluded him until eventually he emerged from the Egyptian cotton he’d replaced his landlady’s cheap polyester with, and lay on his back in the bed that was too soft, that sent him precariously close to one edge each time he rolled over. His upper arm was bruised from smashing into the squash court wall last night, so it was hard to get comfortable. Hands beneath his head, he stared at the ceiling, at the damp patch near the small window. And then at the framed photo beside him. He knew the picture intimately, the Dales rolling gently behind the figures in the foreground, the wide open space of his own childhood calling him, his children’s carefree faces beaming out at him, gap-toothed grins, dimples, freckles like join-the-dots. A photo pored over too many times now until it almost meant nothing. He knew it almost as well as his own face, but that brought little relief from the homesickness he so often suffered.

Silver rolled away from the three grins. Missing the children was a constant weight, like knees on his chest; a pain he fought every bloody day alongside the guilt, a guilt that called him northwards again but that he had not yet succumbed to. He wondered idly what Julie was doing today and then acknowledged that he didn’t really care. She had a good body (‘nice rack’, Craven would say and everybody else would tut and roll their eyes) but nothing much to say. She’d giggled a lot when they went to that dreadful wine bar last week and talked about police dramas. In particular, Lewis’s sidekick Hathaway, who was played by a Fox, who apparently was a fox: until Silver had had to grit his teeth. And later the sex was fine but not good enough to warrant that incessant gurgle that she thought was alluring but really wasn’t; that reminded him more of water going down a plug hole than anything else. Not good enough for him to call her on his day off – and anyway he thought he remembered her saying she was away, on some middle management course this week, which no doubt meant trust exercises of the sort that involved falling backwards and catching one another before getting pissed in the identikit hotel bar and waking up hungover and horrified next morning beside a married colleague.

Silver allowed himself a wry smile and briefly debated going to the gym, but for some reason the soulless space in the station basement held little appeal today. He swung his legs out of the bed, his bare feet meeting the polished floorboards, rubbing his short hair impatiently with both hands until it stood on end. He felt confined and caged and suddenly incredibly depressed.

Philippa’s tribe were all still in bed, which was a rare piece of luck. In an effort to cheer himself, Silver spent the next hour drinking coffee in his landlady’s huge kitchen, the early morning sunlight spilling through the old sash windows, and booking a holiday in Corfu for the kids’ October half term. Lana had actually agreed to it last time they spoke, albeit reluctantly, and he wouldn’t take the risk of asking again; he knew it was now or never. Eventually a ping from his email said he’d succeeded: three grand poorer maybe but still, the proud owner of one package holiday with perks.

Philippa plodded into the kitchen now, yawning, rubbing sleep from her almond-shaped eyes, and switched the kettle on. He raised a hand in greeting as he dialled home: the kids would be about to leave for school. He missed the boys, they’d left already, but Molly was breathless with excitement, despite Lana’s low tones chiding her to put her shoes on whilst she talked.

‘Come on, Molly.’

He heard the dull exasperation in his ex-wife’s tone and his fist clenched unconsciously, wondering why the hell she couldn’t just let him have this time, why she couldn’t relax for one moment. But he still managed to absorb the pleasure in his youngest child’s voice, words tumbling over each other about the plane, about beaches and ice cream and staying up late. Halfway through the excited patter, as Philippa padded out to the hall to start screeching at her kids who were not getting up, his mobile rang.

Kenton’s name flashed up.

‘Hang on, kiddo,’ he said to Molly and answered the mobile. ‘Silver.’

‘Sir,’ she was stammering; he could hardly hear her words for the jarring dissonance of sound behind her. ‘There’s been an incident. An explosion.’

He spoke to Molly quickly. ‘Mol. I’ll call you tonight.’

‘OK.’ For once he’d fed her enough for her to be happy to hang up. ‘Thanks, Daddy. Love you.’

‘Where are you, Lorraine?’ He stood now.

‘Berkeley Square. I was on my way to the TV place.’

He could hear pure terror in her voice; sensed her trying to suppress panic.

‘Are you OK?’

‘Yes. But – I don’t know what to—’ She was fighting tears. He could hear car alarms jostling for air space. ‘What to do.’

‘Call Control.’ Silver tucked the phone beneath his ear and reached for the remote, snapping the television on. Nothing yet. ‘I will too. And don’t do anything stupid.’

He rang Control; they knew already. He hung up. His phone rang again. It was Malloy.

‘You’d better get down here, Joe. It’s a fucking disaster.’

An appalled Philippa stood behind him as they watched the images begin to unfurl on the television. The tickertape scrolling on the bottom of the screen ‘Breaking News’; the nervous presenter, the ruined bank, the burnt bus, the smart London square now home only to distress and panic. Silver felt that familiar twist in the belly, the lurch of adrenaline that marked crisis.

‘Oh dear Lord,’ Philippa whispered. ‘Not again.’

Eyes glued to the screen, mobile clamped to his ear, Silver watched for a moment. The buzz, the rush; what he lived for. Julie and the stinking gym and the irritation Lana caused him faded entirely. He spoke to his boss.

‘I’m on my way.’

FRIDAY 14TH JULY CLAUDIE

At Natalie’s neat little house in the suburbs, Ella at least was happy to see me, demonstrating her hopping on one leg, her fair curls bouncing up and down, chunky and solid as her mother but far more cuddly.

‘Good hopping,’ I admired her. ‘Can you do the other side?’ But she couldn’t really, despite gallant efforts.

‘Please, Auntie C, can we play Banopoly?’

‘Banopoly?’ She meant Monopoly. ‘Of course. I’d love to.’

‘You can be the boot if you like,’ she said kindly, swinging on my hand. I agreed readily, because I felt like an old boot right now, and it suited me just fine to not think about real life for a moment.

‘Claudia’s hurt, Ella,’ Natalie said, but her heart wasn’t in it. She was so transfixed by the television, by the rolling news bulletins, that she wasn’t concentrating on either of us, so Ella and I sat in the kitchen, away from the television, and had orange squash and digestives as we set the Monopoly board up. In the end, I was the top hat and Ella was the dog, and I let her buy everything, especially the ‘water one with the tap on’ because I knew if she lost, her bottom lip would push out and she would cry. And I found if I didn’t move too suddenly or dramatically, the pain in my head was just about bearable.

At twelve o’clock Natalie washed Ella’s hands and face and took her round to her school nursery for the afternoon session.

‘Will you be here when I get back, Auntie C?’ Ella asked solemnly. ‘We can watch Peter Pancake if you are.’ And I smiled as best I could and said probably. She had once informed me that my complicated name was actually a man’s, and she had long since stopped struggling with it.

‘Of course you’ll be here,’ Natalie snapped, ‘where else are you going to go?’ and we looked at each other in a way that meant we were both acknowledging the reason why I wouldn’t be anywhere else.

‘And of course, we want you here,’ Natalie managed a valiant finish, retying her fussy silk scarf under her chin.

As the door shut behind them, I slid open the French windows and stood in the garden and tried very hard to breathe deeply like Helen had taught me. Natalie’s pink and green garden was so well regimented, just like everything else in her life, that it felt stifling. The air was heavy, rain was on its way, and a strange hush seemed to have descended. Everyone staying inside and a hush that had settled over the whole city – as if we were all waiting. I felt very small suddenly; tiny, a mere dot on the London landscape.

I made myself tea and I put a lot of sugar in it, and then I tried and tried to ring Tessa, but she wasn’t answering; her phone wasn’t even on. No one picked up at the Academy either, so eventually I gave up, and switched on the News again.

MASSIVE EXPLOSION IN CENTRAL LONDON scrolled across the bottom of the screen, and a reporter who looked a little like a rabbit in the headlights informed viewers nervously that Berkeley Square had been hit by some kind of explosion but at the moment no one knew if it was a bomb or a gas main that had blown up. There was no more information, but then numbers were listed for those worried about friends or family; and we were all asked to stay at home.

‘Do not attempt to travel in central London. As a precaution, police have shut down all public transport systems for the moment. We reiterate, it is only a precaution, but the advice is to please remain at home unless your journey is absolutely necessary,’ the dark-skinned reporter warned us gravely, before throwing questions to a sweaty terrorism expert who began to hazard guesses at the cause of the explosion.

My phone rang again. This time I did answer it, praying it was Tessa.

‘Claudie. I’ve been so worried. What the hell’s going on?’ Rafe sounded furious. ‘I thought you’d be here when I got back.’

‘London’s gone mad,’ I said quietly. ‘It’s all exploding.’

‘Never mind that – what the hell happened last night? I waited for you in the restaurant, and you never came, and then there you were, on my doorstep, frozen and practically unconscious. Were you drunk?’ He was accusatory.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘Definitely not drunk.’

‘What then?’

‘I can’t remember, Rafe. I just – I had this terrible migraine, and then—’

‘What do you mean you can’t remember?’

Now was not the time to tell him about the splitting. In fact, I was realising there was never going to be a time to tell him about it. And yet, I was terrified that I was sliding backwards, back to the place I’d gone when Ned died, when my world had caved in and the nightmare became reality.

‘Rafe, one thing—’

‘Yes?’

‘Who is she?’ I stared at my bare feet. The ground beneath them was shifting again and life was not going to be the same now, I realised. My silver nail varnish was very old and chipped. I must do something about it, I thought absently.

‘Who?’

‘The owner of the pink toothbrush. In the bathroom cupboard.’

‘No one.’ There was a long pause. ‘It’s not what it looks like. I mean, she’s just an old friend.’

‘Yeah right.’ I felt so tired I could hardly speak.

‘She stays sometimes when she’s in town. That’s all.’ He was both contrite and angry in turns, as if he hadn’t quite decided the best form of defence.

‘It’s fine. Look, I’ve got to go, Rafe. It’s up to you what you do.’

‘Claudie—’

I hung up. I tried Tessa again. Nothing.

I was frightened. I was fighting panic. Why couldn’t I remember this morning clearly? I debated ringing my psychiatrist Helen, but I wasn’t sure that was a good idea. I couldn’t go running to her every time something went wrong. And she might think I was deluded again, and I wasn’t sure I could bear that.

I switched the News on again, the explosion still headlines, the first pictures I had seen. A bus lay on its side in hideously mangled glory, like a huge inert beast brought down by hunters. The newsreader emitted polite dismay as I stared at the pictures in horror.

‘Speculation is absolutely rife in the absence of any confirmation of what exactly rocked the foundations of Berkeley Square this morning at 7.34 a.m. Immediate assumptions that it was another bomb in the vein of the 7/7 explosions five years ago are looking less likely. Local builders were working on a site to the left of the square, the adjacent corner to the Royal Ballet Academy, on a new Concorde Hotel. The site is situated above an old gas main that has previously been the subject of some concern. The Hoffman Bank has been partially destroyed; at least one security guard is thought to have been inside. So far, Scotland Yard have not yet released a statement.’

At least, thank God, the Academy seemed untouched by the explosion. I tried Tessa one more time, and then Eduardo; both their phones went to voicemail now. I turned the News off and went upstairs, craving respite. I heard Natalie and Ella come in, Ella chattering nineteen to the dozen. I felt limp with exhaustion. I’d tried so hard to stay in control recently, and yet something had gone very wrong.

In the bathroom I rifled through Natalie’s medicine cabinet: finding various bottles of things, I took what I hoped was a sleeping pill. I went to the magnolia-coloured spare bedroom with the matching duvet set, shut the polka-dot curtains against the rain that had just started, and invited oblivion in.

FRIDAY 14TH JULY KENTON

Silver had insisted DS Kenton was checked out by the paramedics, but she knew that she wasn’t injured, only shocked. He wanted her to go home, but Kenton wasn’t sure being alone was the right thing. She kept seeing that hand in the middle of the road, bloody and raw, and the body sliced completely in two, and every time she saw it, she had to close her eyes. She felt numb and rather disconnected from reality; she sat in the station canteen nursing sweet tea and it was a little like the scene around her was a film, all the colours bright and sort of technicolour.

The person Kenton really wanted to speak to was her mother, but that was impossible. So she rang her father, but he was at the Hospice shop in town, doing his weekly shift, and he couldn’t work his mobile phone properly anyway, so he kept cutting her off, until she gave up and said she’d call later. She didn’t even get as far as telling him about her trauma. She drank the tea and stared at the three tea leaves floating at the bottom, and then on a whim, she rang Alison.

Alison didn’t answer, so she left her a rather faltering, stumbling message.

‘Hello. It’s me.’ Long pause. Not wanting to sound presumptuous she qualified: ‘Me being Lorraine.’ Oh God, now she sounded like an idiot. ‘I’ve been in a – in the – I was there when Berkeley Square, when it exploded.’

She panicked and hung up.

On the other side of the canteen she saw Silver stroll in, as calm and unruffled as ever, his expensive navy suit immaculate, not a hair out of place. She could understand why women’s eyes followed him; not particularly tall, not particularly gorgeous, perhaps, but just – assured. Commanding, somehow.

‘Lorraine.’ He bought himself a diet Coke from the machine behind her. ‘How you feeling? Time to go home, kiddo?’

‘I don’t know.’ Her voice was trembly. She cleared her throat. ‘I keep thinking about the hand.’

‘The hand?’ Silver snapped the ring-pull on the can and sat opposite her.

‘There was a hand,’ she whispered. ‘In the road. Just lying there. There were – there were other – bits.’

‘Right.’ He looked at her, his hooded hazel eyes kind. ‘Nasty. Now, look. Go home, get one of the lads to drive you if you want – and call me later. We’ll have a chat. Take the weekend off. And you should think about seeing Merryweather.’

‘I’m not mad,’ Kenton was defensive.

‘No, you’re in shock. Naturally. And you did a great job, Lorraine.’ His phone bleeped. ‘A really great job.’ He checked the message. ‘Explosives officers are at the scene now. Got to go. Call me, OK?’

‘OK.’ She sat at the table for another few minutes. Sighing heavily she began to gather her things. Her phone rang. Her heart skipped a beat. It was Alison.

‘Lorraine.’ She sounded appalled. ‘Oh my God. Are you OK? What happened?’

Kenton felt some kind of warmth suffuse her body. Alison had rung back. She walked towards the door, shoulders back.

‘Well, you see, I was on my way to a TV briefing,’ she began.

MONDAY 17TH JULY CLAUDIE

I woke sweating, like a starfish in a pool of my own salt. A bluebottle smashed itself mercilessly between blind and window, its drone an incessant whirr into my brain. It had been a long night of terrors, the kind of night that stretches interminably as you hover between sleep and consciousness, unsure which is dream and which reality.

‘Where are you? Where are you? Why are you not answering? I’m scared, Claudie, I can’t do it, Claudie …’

My heart was pounding as I tried to think where the hell I was. I tried to hold on to the last dream but it was ebbing away already, and fear was setting in. Momentarily I couldn’t remember anything. Why I was here. I was meant to be somewhere else surely – I just couldn’t think where.

I had spent the weekend at Natalie’s, against my better judgement but practically under familial lock and key. Natalie was truly our mother’s daughter, and I’d found the whole forty-eight hours almost entirely painful. She had fussed over me relentlessly, but it was also as if she could not really see me; as if she was just doing her job because she must. In between cups of tea and faux-sympathy, I’d had to speak to my mother several times, to firstly set her mind at rest and then to listen to her pontificate at length on what had really happened in Berkeley Square, and whether it was those ‘damned Arabs’ again. And all the time she’d talked, without pausing, from the shiny-floored apartment in the Algarve where she spent most of her time now, and wondering whether she should come over, ‘Only the planes mightn’t be safe, dear, at the moment, do you think?’ I’d kept thinking of Tessa and wondering why she didn’t answer her phone now.

Worse, it had poured all weekend, trapping us in the house. The highlight was Ella and the infinite games of Connect 4 we played, which obviously I lost every time. ‘You’re not very good, are you, Auntie C?’ Ella said kindly, sucking her thumb whilst my sister scowled at her ‘babyish habit’. ‘Let her be, Nat,’ I murmured, and then Ella let me win a single round.

The low point was – well, there was a choice, actually. There had been the moment when pompous Brendan drank too much Merlot over Saturday supper and had then started to lecture me on ‘time to rebuild’ and ‘look at life afresh’ whilst Natalie had bustled around busily putting away table-mats with Georgian ladies on them into the dresser. I had glared at my sister in the hope that she might actually tell her husband to SHUT UP but she didn’t; she just rolled table napkins up, sliding mine into a shiny silver ring that actually read Guest. So I sat trying to smile at my brother-in-law’s sanctimonious face, thinking desperately of my little flat and the peace that at least reigned there. Lonely peace, perhaps, but peace nonetheless. After a while, I found that if I stared at Brendan’s wine-stained mouth talking, at the tangle of teeth behind the thin top lip, beneath the nose like a fox’s, I could just about block his words out. For half an hour he thought I was absorbing his sensitive advice, instead of secretly wishing that the large African figurehead they’d bought on honeymoon in the Gambia (having stepped outside the tourist compound precisely once, ‘Getting back to the land, Claudie, and oh those Gambians, such a noble people, really, Claudie; having so little and yet so much. They thrive on it’) would crash from the wall right now and render him unconscious.

The second low came on Sunday morning, just after I had turned down the exciting opportunity to accompany them to the local church for a spot of guitar-led happy clapping.

‘Leave Ella here with me,’ I offered. My head was clearer today, not as sore and much less hazy than it had felt recently. The paranoia was receding a little. ‘It must be pretty boring for her, all that God stuff.’

‘Oh I can’t,’ Natalie actually simpered. ‘Not today. We have to give thanks as a family.’

‘What for?’ I gazed at her. She looked coy, dying to tell me something, that familiar flush spreading over her chest and up her neck and face. I looked at her bosom that was more voluptuous than normal and her sparkling eyes and I realised.

‘You’re pregnant,’ I said slowly.

‘Oh. Yes,’ and she was almost disappointed that she hadn’t got to announce it, but she was obviously wrestling with guilt too. ‘Are you OK with that?’

‘Of course. Why wouldn’t I be?’ I moved forward to hug her dutifully. ‘I’m really pleased for you.’

Natalie grabbed my hands and pushed me away from her so she could search my face earnestly. ‘You know why. It must be so hard for you.’ A little tear had gathered in the corner of one of her bovine brown eyes. ‘I – I’d like you to be godmother though,’ she murmured, as if she was bestowing a great gift. ‘It might, you know. Help.’

‘Great,’ I smiled mechanically. And I was pleased for her, of course I was, but nothing helped, least of all this, though she was well-intentioned; and I knew it was impossible for anyone else to understand me. I was trapped in my own distant land, very far from shore; I’d been there since Ned closed his eyes for the last time and slipped quietly from me. ‘Thank you.’ And I hugged her again, just so I didn’t have to look at the pity scrawled across her face.

‘If it’s a boy,’ she started to say, ‘we might call him—’

I heard an imaginary phone ringing in my room upstairs. ‘Sorry, Nat. Better get it, just in case—’ I disappeared before she could finish.

Whilst they were at church, I gathered my few bits and pieces and wrote her a note. I was truly sorry to leave Ella, I loved spending time with her, but I needed to be home now. I needed to be far, far away from my well-meaning sister and the suffocating little nest she called home.

And so here I lay, alone again. In the next room, the phone rang and I heard a calm voice say ‘Leave us messages, please.’

My voice, apparently; swiftly followed by another – male, low. Concerned. I attempted to roll out of bed, but moving hurt so much I emitted a strange ‘ouf’ noise, like the air being pushed from a ball. I lay still, blinded by pain, my ribs still agony from where I’d apparently fallen on Friday. When it subsided, I tried again. Wincing, I stumbled into the other room, snatched the receiver up.

‘Hello?’

‘You’re all right.’ The accented voice was relieved. ‘Thank God.’

‘Who – who is this?’ I caught my reflection in the mirror. Round-eyed, black-shadowed; face scraped like a child’s. My bare feet sank into the sheepskin rug I hated.

‘Claudie. It’s Eduardo. I didn’t know if you’d be there. Your sister called. I thought you might be away.’

‘Away?’ My brow knitted in concentration. ‘Eduardo.’ I made a concerted effort. Eduardo was head of the Academy. In my mind I conjured up an office, papers stacked high, a man in a grey cashmere v-neck, big hands, dark-haired, moving the paperweight, restacking those papers. ‘Oh, Eduardo.’ I sat heavily on the sofa. ‘No, I’m here. Sorry. I think I – I find it hard to wake up sometimes.’

I had got used to a little help recently, the kind of pharmaceutical help I could accept without complication.

‘I’m ringing round everyone to check. You’ve obviously heard what has happened?’

‘About the explosion? Yes,’ my hands clenched unconsciously. ‘Awful.’

‘Awful,’ he agreed. ‘They have only just let us back into the school. But – well, it’s worse than awful, Claudie, I’m afraid.’ I heard his inhalation. ‘There is some very bad news.’

Bad news, bad news. Like a nasty refrain. I stood very quickly, holding my hands in front of me as if warding something off.

‘I’m sorry.’ I sensed his sudden hesitation. ‘I should have thought. Stupid.’ He’d be banging his own head with the heel of his hand, the dramatic Latino. ‘My dear girl—’

‘It’s OK.’ I leant against the wall. ‘Just tell me, please.’

‘It’s Tessa.’

‘Tessa?’ My cracked hands were itching.

Tessa, with her slight limp and her benign face, her hair pulled back so tight. My friend Tessa who had somehow seen me through the past year; with whom I had bonded so strongly through our shared sense of loss. My skin prickled as if someone was scraping me with sandpaper.

‘Tessa’s dead, Claudie. I’m so sorry to have to tell you.’

Absently, I saw that my hand was bleeding, dripping gently onto the cream rug.

Emboldened by my silence, he went on. ‘Tessa was killed outside the Academy. Outright.’ He paused. ‘She wouldn’t have known anything, chicita.’

‘She wouldn’t have known anything,’ I repeated stupidly. My world was closing to a pin-point, black shadows and ghosts fighting for space in my brain.

‘I’m so sorry to have had to tell you,’ he said, and sighed again. ‘I am just pleased for you that you are not here this week. It is a very bad atmosphere. I think it’s good your sister has arranged for you to have this time off.’ I hadn’t had much choice in the matter: Natalie had taken over. ‘Try to rest, my dear. See you soon.’

Tessa was dead. Outside the birds still sang; somewhere nearby a child laughed, shrieked, then laughed again. The rain had stopped. Someone else was playing The Beatles, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds; Lennon’s voice floated through the warm morning, like dust motes on dusk sunshine. Death was in the room again. I closed my eyes against the cruel world, a world that kept on turning nonetheless, a sob forming in my throat. I imagined myself now, stepping off the bus, fumbling with the clasp of my bag, raising my hand in greeting, happy to see her …

The birds still sang, but my friend Tessa was dead – and I couldn’t help feeling I should have saved her.

TUESDAY 18TH JULY SILVER

7 a.m., and Silver was exhausted already. It had been a horrendous weekend; the worst kind of police work. Counting the dead, identifying and naming the corpses: or rather, what was left of them. Recrimination and finger-pointing and statistics that meant nothing. Contacting the families, working alongside the belligerent and somewhat over-sensitive Counter Terrorist Branch; waiting for the Explosives Officers who were struggling due to the amount of debris caused by the Hoffman Bank partially collapsing, hampered by torrential rain all weekend.

Images stuck to the whiteboards at the end of the office made him wince; the carnage, the tangle of metal, strewn rubber, clothing, the covered dead and the walking wounded. The life-affirming sight of human helping human – only wasn’t it a little late? Too late to make a difference: one human had hated another enough to do this – possibly … A gas leak was still being mooted, but Silver knew the drill, knew this was to prevent panic spreading through the city, another 7/7, another 9/11, the stoic Londoner weary of it all already. The Asians fed up of ever-wary eyes, the Counter Terrorist Branch overworked and frankly baffled. How do you keep tabs on invisible evil that could snake amongst us unseen? Silver was hanged if he knew.

He yawned and stretched as fully as his desk allowed. That bastard Beer was calling him, whispering lovingly in his ear over and again. He needed a long cold pint, smooth as liquid gold down his thirsty aching throat. He swore softly and checked the change in his pocket. Out in the corridor, he bought himself his fifth diet Coke of the night and unwrapped another packet of Orbit. Distractions. He wished he felt fresher, more alert, but he felt tired and rather useless. However much he preferred work to home, he wished himself there now, asleep, oblivious to the world’s inequities. Leaning against the wall wearily, he drank half the can in one go.

Craven popped his balding head out of the office. ‘Your wife’s on the phone.’

‘Ex-wife,’ Silver said mechanically.

In an exercise of male camaraderie, Craven grimaced. ‘Sorry. Ex-wife.’

Silver checked his expensive Breitling watch. Following Craven, he leant over the desk for the receiver. It was early even for her.

‘Lana?’

There was a long silence. He rolled his eyes; he thought he heard a sniff. Lana never cried.

‘What is it, kiddo?’ he tried kindness. He had ignored so many things recently, he was stamping all over his ‘emotional intelligence’ apparently; the intelligence they’d been lectured on recently at conference.

‘Don’t call me that, Joe,’ Lana snapped. ‘It drives me bloody mad.’

Some things never changed. And he didn’t have time for emotional intelligence anyway. He relied on gut instinct.

‘Sorry.’ He almost grinned. ‘What is it, Allana?’

‘I saw her on the News.’

The hairs on his arms stood up. Not this again.

‘I couldn’t sleep so I got up. It was GMTV,’ she was breathless and angry. ‘She was just there, smiling. A photo. I saw her, Joe.’

He’d thought they were through this. ‘Don’t be daft, Lana.’ Through, and out the other side. He dropped his voice to little more than a whisper. ‘We’ve been over this a million times.’ Persuasive, comforting. ‘It’s not her. It can’t be.’

‘On the News. I was watching about the bomb.’

‘Explosion,’ again, he corrected automatically.

‘Explosion. Whatever.’ Her distress was palpable. ‘They had a separate item about missing kids. She’s a dancer. I saw her face.’

‘Whose face?’ He knew who; but he needed her to say it, needed to hear the name.

A gulp, as if she were swallowing air. ‘Jaime. Jaime Malvern.’

‘Lana. Are you drunk?’

‘Nooo,’ the vowel was a long hiss, drawn-out. ‘I am stone cold sober, Joseph. But it’s her. As sure as eggs is eggs.’

They used to laugh at that expression. They used to lie in bed, legs intertwined, and do all the egg expressions: ‘Eggs in one basket, don’t count your chicken eggs.’ They were young, they were in love. They thought they were hilarious. ‘Teach your grandmother to suck eggs.’

Neither of them was laughing now.

‘Lana. It can’t be Jaime, you know that. She’s dead, kid— sweetheart. She’s been dead a long time now.’

‘I know,’ she howled, and the pain in her voice pierced him in the old way. ‘I know she’s bloody dead, Joe.’

Of course she did. Of course Lana knew this better than anyone.

‘But I saw her, Joe. I’m not mad, and I’m not drunk. Not yet anyway. I saw her.’

He stood now. ‘Lana. Don’t. You’ve done so well.’

But she’d gone. He was talking to the air.

Silver didn’t believe his ex-wife’s claims that she’d seen Jaime; he’d heard it a million times before. Allana had been haunted by Jaime’s face every day for six years, obsessed since the accident – since the afternoon that changed their lives forever. The afternoon that ruined Lana irrevocably and finished Jaime’s forever.

Silver had tried his damnedest to bring his wife back to the present, tried and failed; he’d grown used to Allana’s distress and his own guilt. He’d attempted every tactic: therapy, rehab and finally anger, until eventually he knew she was beyond reach. He mourned his lost love – for too long; until finally the mourning turned to indifference as he accepted he could no longer connect. No one could really pierce that layer of pain; not even her own children.

Silver hung up the phone feeling weary of battle. Tired and flat, he was ready for his bed – but something nagged at him. Draining the final backwash of diet Coke and crunching the can in one hand, he sat at the computer and quickly scrolled through the gallery of faces that flashed up. First the missing from the explosion: a photo album of mostly smiling anonymity, gathered quickly by frenetic journalists, posing for graduation, wedding, family snaps. Mothers, sons, nieces, nephews. Many of the families still waiting for their worst fears to be confirmed. The mess that is identifying devastated bodies after fatal accidents. Fourteen dead; the death toll still rising.

He called up the general Missing folder. Nothing. Allana was mad as ever. Not mad, he corrected himself; obsessed. Yawning until his jaw ached, Silver reached the final screen – and then – on a separate page, that face.