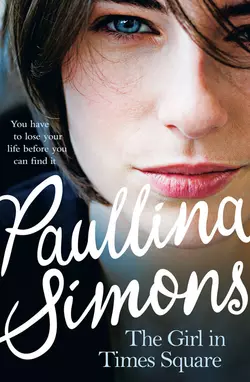

The Girl in Times Square

Paullina Simons

A stunning and powerful contemporary love story from one of the best storytellers this century. What if everything you believed about your life was a lie?Meet Lily Quinn. She is broke, struggling to finish college, pay her rent, find love. Adrift in bustling New York City, the most interesting things in Lily’s life happen to the people around her. But Lily loves her aimless life … until her best friend and roommate Amy disappears. That’s when Spencer Patrick O’Malley, a cynical, past his prime NYPD detective with demons of his own, enters Lily’s world. And a sudden financial windfall which should bring Lily joy instead becomes an ominous portent of the dark forces gathering around her.But fate isn’t finished with Lily.She finds herself fighting for her life as Spencer’s search for the missing Amy intensifies, leading Lily to question everything she knew about her friend and family. Startling revelations about the people she loves force her to confront truths that will leave her changed forever.From a master storyteller comes a heart-wrenching, magnificent and unputdownable novel.This is the odyssey of two young women, Lily and Amy, roommates and friends on the verge of the rest of their lives.

PAULLINA SIMONS

THE GIRL IN TIMES SQUARE

Copyright (#ulink_2f588342-4380-5e63-b05d-d035ac86c1ab)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Copyright © Paullina Simons 2004

“Lost in the Flood” by Bruce Springsteen. Copyright © 1972

Bruce Springsteen. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

“Fire” by Bruce Springsteen. Copyright © 1978

Bruce Springsteen. All rights reserved.

“Across the Border” by Bruce Springsteen. Copyright © 1995

Bruce Springsteen. All rights reserved.

Paullina Simons asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007118939

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007383979

Version: 2018-05-24

Dedication (#ulink_80c021b9-57d8-59b3-92a4-44cdbd453e62)

For my sister, Elizabeth, as ever searching And for Melanie Cain, who has been to the crying room

Epigraph (#ulink_d2edec10-645d-510f-9ed1-521cca2aaf13)

In the Vatican after they have chosen a new pope, they lead him to a room off the Sistine Chapel where he is given the clothing of a pope. It is called the Crying Room. It is called that because it is there that the burdens and responsibilities of the papacy tend to come crashing down on the new pontiff. Many of them have wept. The best have wept.

PEGGY NOONAN

Contents

Cover (#u2fbb36c5-caff-5747-aa9e-068c91dd28eb)

Title Page (#u72a465a6-143c-58d2-994e-24727400ba11)

Copyright (#ulink_86d703fa-31d5-5693-b4a2-b982c87bff87)

Dedication (#ulink_75dd8694-2278-5195-8dec-d2507d84d1e4)

Epigraph (#ulink_fab94f46-f0fe-5d74-97fb-e721e2cf0863)

The Past as Prologue (#ulink_08485193-da2f-53dc-b58a-6786b5491450)

Just Before the Beginning

Lily Quinn (#ulink_bab109e6-7193-53c2-8f98-1951527c1303)

Allison Quinn (#ulink_96f4dc6e-0309-56c9-b1f4-b924bdc1339f)

A Man and a Woman (#ulink_d3ad7ac7-04bc-5604-a0bd-49a723eea1df)

Part I. In the Beginning (#ulink_c542fb0e-ebf1-5c67-8bee-fea06f785878)

1. Appearing To Be One Thing When it is in Fact Another (#ulink_9e0cd9bf-3c21-51b9-ae10-733b6aebdbd7)

2. Hawaii (#ulink_8f2089ef-092d-5cd6-88ff-a7698cb7c593)

3. An Hour at the 9th Precinct (#ulink_47717268-dc64-58c5-bf8d-be2fb8d6d594)

4. Wallets on Dressers (#ulink_5e20b23c-b00c-5d75-b7e9-50d430658cd1)

5. Spencer Patrick O’Malley (#ulink_e2f30285-a5fc-5052-b9ca-0a7b507497af)

6. Conversations with Mothers (#ulink_4c328652-6208-52f7-9933-9162be1d8ad4)

7. Birds of Paradise (#ulink_8362f3c4-ce64-5e81-944f-f88afbf31d2c)

8. The Disadvantages of Walking to Work (#ulink_a79d0171-8936-52cd-991d-67f98b09f661)

9. Ignorance in Amy’s Bed (#ulink_1a3502a6-76f1-5b6e-bb2c-57a5f9534e98)

10. Things in the Closet (#ulink_5b3894d7-d1f6-58d5-b4f8-1536fa223631)

11. Spencer Patrick O’Malley and Lilianne Quinn (#ulink_2bab3590-c68f-55c9-8386-2e38f44c4477)

12. A Little Rented Honda (#ulink_9cc69625-300b-5043-848e-be0749ebd270)

13. Lily and the City of Dreams (#ulink_d45d5338-dd07-57cd-a4ad-f2977b9a1f15)

14. Riding Shotgun (#ulink_f44a09a2-73a6-55f3-9976-c051ffbefd27)

15. Spencer’s Twelve Tickets (#ulink_dc33833e-d71e-5bd9-9c79-882474395b50)

16. Reality: The Actual Thing that it Appears to Be (#ulink_361bfa28-c335-524c-bce9-1f5c941974b2)

Part II. The Middle of the Road (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The Biggest River in Egypt (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Fertility Options (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Fibers of Suspicion (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Just Another Saturday Night for Lily (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Just Another Saturday Night for Spencer (#litres_trial_promo)

22. In the Garden of the Barber Cop (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Chemotherapy 101 (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Meet the Parents (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Chemo 202 (#litres_trial_promo)

26. The Church on 51st Street (#litres_trial_promo)

27. Liz Monroe and 57/57 (#litres_trial_promo)

28. The Soup Kitchen (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Spencer Stuck Twice (#litres_trial_promo)

30. Advanced Chemotherapy (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Advanced Interrogation (#litres_trial_promo)

32. Andrew’s Alibi (#litres_trial_promo)

33. The Laugh Track (#litres_trial_promo)

34. Lily’s Stations (#litres_trial_promo)

35. Lily’s Mother is Here (#litres_trial_promo)

36. Lily’s Stations, Continued (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Beautiful People (#litres_trial_promo)

38. Cancer Shmancer (#litres_trial_promo)

39. Larry DiAngelo as Imhotep (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III. The End Game (#litres_trial_promo)

40. Lily as an Ancient Egyptian (#litres_trial_promo)

41. Shopping as Healing (#litres_trial_promo)

42. The Financial and Eating Woes of a Lottery Winner and a Cancer Survivor (#litres_trial_promo)

43. A Little Thing about Spencer (#litres_trial_promo)

44. The Muse (#litres_trial_promo)

45. A Masters Course in Chemo (#litres_trial_promo)

46. The Mighty Quinn (#litres_trial_promo)

47. Harkman (#litres_trial_promo)

48. The Yellow Ribbons (#litres_trial_promo)

49. Baseball as a Metaphor for Everything (#litres_trial_promo)

50. April Fools (#litres_trial_promo)

51. At Internal Affairs Once More (#litres_trial_promo)

52. Failing Test Number One (#litres_trial_promo)

53. A Cop First (#litres_trial_promo)

54. Infernal Affairs (#litres_trial_promo)

55. Failing Test Number Two (#litres_trial_promo)

56. Unraveling at Home and Overseas (#litres_trial_promo)

57. An Encounter at Tompkins Square (#litres_trial_promo)

58. Eight Days in Maui (#litres_trial_promo)

59. And Now—About Spencer (#litres_trial_promo)

60. John Doe (#litres_trial_promo)

61. Olenka Pevny (#litres_trial_promo)

62. Lindsey (#litres_trial_promo)

63. A Terminal Degree in Cancer Treatment (#litres_trial_promo)

64. Amy and Andrew (#litres_trial_promo)

65. Nathan Sinclair (#litres_trial_promo)

66. A Boat in Key Biscayne (#litres_trial_promo)

67. Cabo San Lucas (#litres_trial_promo)

68. A Day at the Abbey (#litres_trial_promo)

69. An Anarchist in Action (#litres_trial_promo)

70. Massacre Grounds (#litres_trial_promo)

71. The Cancer Chick and the Revolutionary (#litres_trial_promo)

72. The Peyote Dance (#litres_trial_promo)

73. The Lessons of the Russian Tsar (#litres_trial_promo)

74. Acting Without Measure (#litres_trial_promo)

75. The Postman (#litres_trial_promo)

76. The Only One (#litres_trial_promo)

77. Wollman’s Rink (#litres_trial_promo)

78. DNR (#litres_trial_promo)

79. And Now—About Amy (#litres_trial_promo)

80. The Other Side (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

THE PAST AS PROLOGUE (#ulink_84759fcc-df09-577c-ab7f-46752b982740)

“Spencer, do you see this?”

“Katie, I do.”

“Her investments are shooting out of the sky. I’ve never seen anything like it. Her fund is growing at rate of thirty-four percent a year.”

“Joy, should we have some lunch?”

“Stop smiling at me like that, Larry, I know what your lunch entails. I can’t. I’m knitting.”

Giggling.

“Did you read the paper this morning? In Ethiopia, a grenade exploded at a wedding, killing the bride and three other people.”

“Mother, please!”

“What? Apparently it’s custom for guests to fire their guns at weddings in wild jubilation, though grenades are apparently more rare.”

“You’ll have to excuse my mother, Detective O’Malley.”

“Thank you, but I’m quite entertained by her, Mrs. Quinn.”

“Mrs. Quinn, how are you feeling?”

“I could be better, Dr. DiAngelo. I’m tired all the time. And I wanted to show you this.” There is a pause, the sound of shoes walking across the floor. “What do you think this is? Some kind of a weird rash, right?”

“Allie, do you think you can stop showing the doctor your ailments with the police in the room?”

“Oh, Detective O’Malley has seen worse than this, Mother. Haven’t you, detective?”

“Much worse, and please—call me Spencer.”

“No, Allie, I just don’t understand you at all. Why do this now? It’s just a rash!”

“Oh, you can talk about your Ethiopian exploding brides, but I can’t show the doctor a real problem? The doctor is here, I might as well take advantage, right, Dr. DiAngelo?”

“Absolutely Mrs. Quinn. Let’s see what you’ve got here.”

There is sighing, clothes rustling, a silence, an ahem, a “Well, what is it?”

“Well, Mrs. Quinn, it’s very serious, I’m afraid.”

“Oh, no, what is it, doctor?”

“I’m afraid—I think—I can’t be sure, but I think it’s the Baghdad boil.”

There is silence, a slight familiar snicker from a man’s throat.

“A what?”

“Yes. A tiny sand fly from the Middle East with a fierce parasite stewing in its gut that causes stubborn and ugly sores that linger for months, sometimes years.”

There is a shrieking of incredulous disgust. “Doctor, what are you talking about? What sandflies from the Middle East? We’re in the middle of New York City! It’s just a little chafing, that’s all, very normal, just a little chafing.”

“Larry!”

“Yes, Joy?”

“Stop torturing the poor woman, this is completely unacceptable. Tell her you’re an oncologist, not a dermatologist. Allison, don’t listen to a word he says, he knows nothing but cancer. He is just trying to rile you.”

“Oh.” And then, “I find that completely unacceptable.”

There is laughter everywhere.

No one even noticed when Lily opened her eyes. She was propped up in bed, in her clean hospital room with beige walls, and her paintings everywhere, and white lilies everywhere because they just don’t listen. It seemed like mid-morning. In front of her was the TV, to the right of her was the open window with white lilies in front of it, with a bit of sky beyond them, her mother and grandmother were on that side, and on the other, to her left, sat Spencer. Behind him stood Katie, looking over his shoulder at the financial statements. To his right sat Joy, still knitting, the yellow sweater sizable now. Next to her was DiAngelo, standing close. Lily didn’t move, just her eyes blinked. It was Spencer who looked up from the statements, lifted his eyes, and noticed an awake Lily.

Spencer said, “Lily, I think your broker deserves a raise. Because while you were lying about in the hospital, grafting marrow, she made you seven-hundred-and-fifty-thousand dollars.”

“Sleeping Beauty is awake!” said her mother.

“Lily, finally! I mean, we always said, oh, but did that child love to sleep, but I think you’ve outdone yourself,” said her grandmother.

Lily couldn’t speak. The breathing tube was in her mouth. She moved her hand to remove the tube, and immediately started choking. “Good God,” she croaked. “How long have I been here?”

DiAngelo put the tube back in her throat, adjusted the mask over her face, the clip over her nose, placed her hands back down on the blanket. “Since your transplant? Eighteen days. Don’t speak. Write it down on the Magna Doodle.”

She pulled the mask, the nose clip, the breathing hose out again. Breathing, gasping. “Where’s Papi?”

“Oh, you know your father,” said Allison. “He can’t sit still for a second. He’s out smoking. He told me this morning, let’s just go for an hour, Allie, and then we’ll take a walk in Central Park. He’s impossible.”

Lily and her mother looked at each other for a few moments, Maui in their eyes.

“It’s a good thing you woke up. You are about to miss your twenty-sixth birthday,” said Allison. “You can sleep through anything.”

Lily said between breaths, “Do you see the picture I made for you?” She pointed to the oil on canvas of a little blonde girl in the close lap of a brown-haired woman on a bench in a village yard.

“I see it,” said Allison. She said nothing for a second. “I don’t know who that’s supposed to be. Doesn’t look like me at all.”

“Lily,” said Joy. “Come on, get up. You can’t be lying around all day. We booked a very large room at the Plaza to celebrate your birthday.”

Lily turned her head to look at Joy inquisitively.

Marcie came in. “Oh, look at this, I’m gone for five minutes and Spunky wakes!”

“Yes, Spunky,” said Spencer, “get up. Because Keanu is playing in The Replacements and The Watcher. You’ve got double Keanu waiting for you.”

Lily took the tube out. “Hey,” she mouthed. “Can you give him and me a minute?”

They gladly filed out of the room, and Spencer came close to her, putting his head in the space between her opened arm and her neck. She held his head, caressed his grown-out hair. There were tears in his eyes he didn’t want her to see. This time it was she who said, “Shh, shh.”

“Tell me,” she said, taking quick breaths of oxygen between her words, “did I miss anything?”

“Nothing,” Spencer replied, his caressing hand on her face. “It is all as you left it.”

In October Lily was off the respirator. By Thanksgiving, she was released from the hospital. She never went back to 9th Street and Avenue C. She stayed with Spencer until they found a floor-through apartment in one of the buildings in brand-spanking-new Battery Park City, all the way downtown overlooking the Hudson River, with fourteen-foot ceilings, two bedrooms, two bathrooms, plenty of closets, and a huge living room that became an art space appropriate for a girl preparing for her first gallery show. The living room had a 39th floor view of the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. The whole shebang was quite something and didn’t set her back eleven million. “That’s because it has no crown molding,” pointed out Spencer.

Once Lily asked him what he would have done if she had died, and he mumbled and joked and equivocated his way through an answer, but in the dark of night in their bed, he said, “I would have taken your money, given a quarter to your family, a quarter to the American Leukemia Foundation, and retired from the force. I would have moved to Florida, and opened a gumshoe agency on the waters of Key Biscayne. I would have been warm all the time, maybe built a Spanish contemporary home. That way I would have lived where you had wanted to live, in a house you would have liked. I would have planted palm trees for you, and gone out on the sea for you and thought of you as my last rose of the summer.”

Spencer drank less. The intervals between his bouts got longer, and once he went for four months without. He told Lily that he couldn’t expect more out of life than being with a girl who made him go four whole months without whisky in the hands. “Well, because now Lily’s in the hands,” she said. “Your hands are full.”

Lily continued to go to Paul at Christopher Stanley for her color, despite Spencer’s maintaining that anyone who changed his own hair as often as Paul—from bleached blond to brown and back again constantly—should not be trusted.

Spencer still cuts Lily’s hair.

To continue to be partnered with Gabe, Spencer asked Whittaker to transfer him out of missing persons and into homicide. At the celebratory lunch at McLuskey’s, Gabe maintained to Lily it was all so that Spencer could finally proclaim, “This is Detective O’Malley from homicide.”

Grandma left her house and came every Thursday to meet Lily for lunch. Afterward she and Lily went to the movies, and then Lily took Grandma back to Brooklyn where Spencer came to pick her up after work.

And sometimes, while Manhattan Island twinkled across the river, Lily and Spencer still parked at their Greenpoint docks in his Buick while Bruce Springsteen rocked on the radio.

Anne left KnightRidder and found a new job as a financial writer for Cantor Fitzgerald. She had an office on the south side of the north tower of the World Trade Center, on the 105th floor, and on a clear day she thought she could see all the way to Atlantic City. The New York Harbor, Ellis Island, Statue of Liberty, Verazano Bridge, and the Atlantic Ocean stretched out before her. She had her desk turned around so she could sit every morning when she got in at eight, and sip her coffee and get ready for her day. She told everyone that she had started a new, happier life. Her sisters came to visit her every Monday for lunch. That’s how they repaired their sisterly bonds. Lily left her painting, Amanda left her children with a babysitter, and they met at noon, taking turns choosing a restaurant. Anne wouldn’t let anyone else pick up the tab. “It’s the least I can do,” she said to Lily. And every other Tuesday morning, Anne took Lily to Mount Sinai for her blood work. When Cantor complained about her coming in at eleven on alternate Tuesdays—despite the fact that she stayed in the office until nine those evenings—Anne said they could fire her if they wished, but it was a deal-breaker: she was going to take her sister who was in remission to the hospital.

Cantor Fitzgerald didn’t fire her.

George and Allison sold their Maui condo and came back to the continent, buying a small house in North Carolina, near the Blue Ridge Mountains. Their house was on a little lake where George had a dock from which he fished, and a row boat that he took out every once in a while. He had a vegetable garden and planted a hundred times more than he could eat, praising America for its bounty. He gave all of his vegetables to his summer neighbors. He bought a TV and a satellite dish, and watched sports live and movies galore and went on the Internet, and cooked for Allison, and for his brother and his wife, who lived nearby. He had a busy life. He didn’t travel much, and Allison didn’t either, having learned how to buy gin right off the Internet and have the UPS man deliver it straight to her front door.

George misses his wife. But the tomatoes are very good in the summer. And there’s fishing.

Larry DiAngelo married Joy. They adopted a baby girl from South Korea, and they called her Lily. Joy retired from nursing and stayed home with her baby, in unrepentant daily bliss, cooking and watching Disney videos.

Jim left Jan McFadden. She had no choice but to get into shape and raise her twin children. Every Saturday she goes to the Port Jefferson cemetery on Route 112, and sits by the purple stone with the lilac flowers, easily the most decorated grave in the cemetery, the most colorful, the most vibrant, you can see it from the winding road half a mile away, the purples and violets shout like animated billboards against the gray of the rest. Our beloved daughter and friend, Amy Jean McFadden, 1975–1999.

When Lily talks of Amy, she still says “She has left.” Or, “She has gone missing.”

When Lily can bear to speak of Andrew, she still says, “He has left.” Or, “He has gone missing.”

A small plaque, a favorite quote, written in calligraphy by Amy: When senseless hatred rules the earth, where will redemption reside? hung on the door of Amy’s studio as a last remainder from Amy’s life on 9th Street and Avenue C, and then was stored, deep in Lily’s large closet in Battery Park City, at the back of her summer T-shirts, until Lily found it one day and gave it to Anne, who liked it so much she hung it up in her office on the 105th floor of the North Tower.

One of these New York mornings—it was too beautiful to stay inside, even for Lily who usually liked to go back to bed after Spencer left for work. But she saw the bright and clear skies and seventy-five degrees and no wind—it was a magnificent Maui morning in her New York, when everything seemed not only possible but attainable—and she decided to walk with him two miles to the precinct and then maybe head on to Madison Square Park and sketch the Flatiron while the light was this good, and would soon be gone. She waited for him, basking on the warm side of the street while he went inside the deli to get them coffees. They really must get a coffee maker that worked.

Lily’s blood tests had been so good lately that DiAngelo finally approved a vacation, and Spencer—who’d never been anywhere—finally and with a little convincing, approved one, too. Not to Maui, not to Cabo San Lucas, not to Arizona, but to Key Biscayne. Two weeks, alone with Spencer! They were leaving in a few days and would stay through her 27th birthday.

A convertible buzzed by on quiet Albany Street heading to West Side Highway. The entire downtown Manhattan was in Lily’s view from north to south. A man was putting up flyers for the mayoral primary elections, on this second Tuesday in September, 2001, tacking the posters up on the pole right next to her. Her heart caught on the memory of the poles, the posters, the convertible, the long gone, the long missing.

Lily lowered her head for a moment, then raised it up to the sky and breathed in the air. It was too glorious a day.

Spencer came out of the deli and smiled at her, motioning for her to cross the street, as in, come on, I don’t have all day. She smiled back and waved, lingering just a little longer with the sun upon her face, her sketchbooks in her hands.

Lily knew that Spencer, always glad for small mercies, was glad for this: that she had been comatose and near death when Amy’s bones were discovered off the Bridle Path, because this let Lily remember Amy only as she once had been—wholly imagined and loved—and not as she really was, a person Lily never knew.

And in her new life Lily Quinn, now living each last day with first joy, could continue to hope with a great enchanting hope that maybe her brother Andrew and her friend Amy looked for each other in a place where there were no other lovers, that maybe she had waited for him until he became lost himself and abandoned his convertible after church on Sunday in the waters of the Hudson and she was waving to him from the other side, across the river. The girl slowed down, the man hopped in, and they sped away in a little rented Honda. Amy and Andrew, Allison and George, Claudia and Tomas, and Lily and her Spencer could maybe speed away, forever looking for a place where they would never be found. Without demands, without dead ends, without alcohol, without protocol, a safe place with no sorrow, no monocytes, no blastocytes, no whisky, no war, just a little bit of mercy, a wet and sunny life, and the remains of their fathomless frail free human hearts.

JUST BEFORE THE BEGINNING (#ulink_a93d3564-bdfe-5e16-a06b-3fa0c3d17c8e)

Lily Quinn (#ulink_9d4386cc-c1c3-5a9a-9fb0-e9c2f44f808e)

What happened to love? Lily whispered to herself. Has someone else taken all that was given out for the universe, or have I just not been trying hard enough? What happened to overwhelming, crushing love, the kind of love that moves earth and heaven, the kind of love my Grandma felt for her Tomas half a century ago in another world in another life, the kind of love my father says he felt for my mother when they first met swimming in that warm Caribbean Sea? Doesn’t anyone have that kind of love anymore? Isn’t anyone without armor, without walls, without pain? Isn’t anyone willing to die for love?

Obviously not tonight.

They called her Lil. Sometimes, when they loved her, they called her Liliput. She liked that. And sometimes when they didn’t love her they called her Lilianne. Tonight nobody called her nothin’. Lily, hungry and broke, stood silently with her back against the wall watching Joshua pack his things while she remained just a stoic stain on the wall, eyes the color of bark, hair like ash, dressed in black—somewhat appropriately, she thought, despite what he had said: “It’s only temporary, just to give us a short break. We need it.”

He was leaving, he was not coming back, and she was wearing black. Lily would have liked to clear her throat, say a few things, maybe convince him not to go, but again, she felt that the time for that had passed. When, she didn’t know, but it had passed all the same, and now nothing was left for her to do but watch him leave, and maybe chew on some stale pretzels.

Joshua was skinny and red-haired. Turning his muddy eyes to her, he asked, running his hand through his hair—oh how he loved his hair!—if she had anything better to do than to stand there and watch him. Lily replied that she didn’t, not really, no. She went and chewed on some stale pretzels.

She wanted to ask him why he was leaving, but unspoken between them remained his reasons. Unspoken between them much remained. His leaving would have been inconceivable a year ago: how could she handle it, how could she handle that well?

She stepped away from the wall, moved toward him, opened her mouth and he waved her off, his eyes glued to the television set. “It’s the Stanley Cup final,” was all Joshua said, one hand on his CDs, the other on the remote control with which he turned up the sound on the set, turning down the sound on Lily.

And to think that last week for her final paper, her creative-writing professor, as if the previous week’s obituary flagellation were not enough, gave them a topic of, “What would you do today if you knew that today were the last day of your life?”

Lily hated that class. She had taken it merely to satisfy an English requirement, but if she knew then what she knew now, she would have taken “Advanced Readings on John Donne” at eight in the morning on Mondays before creative writing on Wednesday at noon. Oh, the merciless parade of self-examination! First memory, first heartbreak, most memorable experience, favorite summer vacation, your own obituary (!), and now this.

All Lily fervently hoped at this moment was that today—breaking up with her college boyfriend—would not be the last day of her life.

Her apartment was too small for Sturm und Drang. The hallway served as the living room. In the kitchen the microwave was on top of the only flat counter surface and the drainer was on top of the microwave, dripping the rinsed-out Coke cans into the sink, half of which also served as storage for moldy bread—they did not eat on regular plates; they barely ate at home. There were two bedrooms—hers and Amy’s. Tonight Lily went into Amy’s room and lay down on Amy’s bed, consciously trying not to roll up into a ball.

During the commercial, Joshua got up off the couch for a drink, glanced in on her and said, “You think you could sleep with Amy? I’m going to have to take my bed back. I’d leave it, but then I’ll have nowhere to sleep.”

Lily wanted to reply. She thought she might have something witty to say. But the wittiest thing she could think of was, “What, doesn’t Shona have a bed?”

“Don’t start that again.” He walked into the kitchen.

Lily rolled up into a ball.

Joshua paid a third of the rent. And still she was broke, her diet alternating between old pretzels and Oodles of Noodles. A bagel with cream cheese was a luxury she could afford only on Sundays. Some Sundays she had to decide, newspaper or bagel.

Lily used to read her news online, but now she couldn’t afford the twenty bucks for the Internet connection. So there was no Internet, no bagel, and soon no Joshua, who was leaving and taking his bed and a third of the rent with him.

If only she had had the grades to get into New York University downtown instead of City College up on 138

Street. Lily could walk to school like she walked to work and save herself four dollars a day. That was twenty dollars a week, $80 a month. $1040 a year!

How many bagels, how much newspaper, how much coffee that thousand bucks could buy.

Lily was paying nearly $500 a month for her share of the rent. Well, actually, Lily’s mother was sending her $500 for her share of the rent, railing at Lily every single month. And coming this May, on the day of her purported, supposed, alleged graduation, Lily was going to get her last check from the bank of mom. Without Joshua, Lily’s share would rise to $750. How in the world was she going to come up with an extra $750 come June? She was already waitressing twenty-five hours a week to pay for her food, her books, her art supplies, her movies. She would have to ask for another shift, possibly two. Perhaps she could work doubles, get up early. She didn’t want to think about it. She wanted to be like Scarlett O’Hara and think about it tomorrow—in another book, some fifty years down the line.

The phone rang.

“Has he left, mama?” It was Rachel Ortiz—Amy’s other good friend, maybe even best friend, she of the sudden ironed blonde hair and the perpetual blunt manner. Someone needed to explain to Rachel that just because she was Amy’s friend, that did not automatically make her into Lily’s friend.

“No.” Lily wanted to add that watching the Stanley Cup was slowing Joshua down.

“That bastard,” Rachel said anyway.

“But soon,” said Lily. “Soon, Rach.”

“Is Amy there?”

“No.”

“Where is she? On one of her little outings?”

“Just working, I think.”

“Well, tomorrow night I don’t want you to stay in by yourself. We’re going out. My new boyfriend wants to take us to Brooklyn, to a nightclub in Coney Island.”

“To Coney Island—on Monday?” And then Lily said, “I’m not up to it. It’s a school night.”

“School, schmool. You’re not staying in by yourself. You’re going out with me and Tony.” Rachel lowered her voice to say TOnee, in a thick Italian accent. “Amy might come, too, and she’s got a friend for you from Bed-Stuy, who she says is a paTOOtie.”

“Oh, for God’s sake!” Lily lowered her voice to a whisper. “Joshua’s still here.”

“That bastard,” said Rachel and hung up.

“What, is Rachel trying to fix you up already?” Joshua said. “She hates me.”

Lily said nothing.

That night, after the Stanley Cup was over, up and down the five flights of stairs Joshua traipsed, taking his boxes, his crates, his bags to Avenue C and 4th Street, where he was now staying with their mutual friend Dennis, the hairstylist. (Amy had said to her, “Lil, did you ever ask yourself why Joshua would so hastily move in with Dennis? Did you ever think maybe he’s also gay?” and Lily replied, “Yes, well, don’t tell me, tell that to Shona, the naked girl from upstate New York he was calling on my phone bill.”)

Who was going to cut Lily’s hair now? Dennis had always cut it in the past. Why did Joshua get to inherit the haircutter? Well, maybe Paul, who was Amy’s other best friend, and a colorist, knew how to cut hair. She’d have to ask him.

Joshua had the decency not to ask her to help him, and Lily had the dignity not to offer.

Around 3:00 a.m., he, with his last box in hand, nodded to her, and then left, rushing past her The Girl in Times Square, her only ever oil on canvas that she had done when she was twenty and before she met Joshua.

“There are things about you I could never love,” Joshua had said to Lily two days ago when all this started to go down on the street.

“If I knew that today were the last day of my life, I’d want to be like the girl in the famous postcard, being thrown back in the middle of Times Square, kissed with passion by a stranger when the war was over.

Except—that isn’t me. That is somebody else’s fantasy of a girl in Times Square. Perhaps it’s Amy. But it’s a fraudulent Lily.

The real Lily would sleep late, until noon at least, with no classes and no work. And then, since the weather would be warm and sunny on her last day, she would go to the lake in Central Park. She would buy a tuna sandwich and a Snapple iced tea, and a bag of potato chips, and bring a book she was re-reading at the moment—Sula by Toni Morrison—slowly because she had time, and her notebook and pencils. She would spend the afternoon sitting, eating her food, drawing the boats, and Sula’s Ajax—with whom she was perversely in love—reading, thinking about what to render next. She’d have a long sit-and-sketch on the rocks and on the way home at night she would go to Times Square pushing past all the people and stand against the wall, looking at the color billboards animating and the towers sparkling, red green traffic lights changing and blue white sirens flashing, the yellow cabs whizzing by. The naked cowboy standing in the street, playing his guitar in his hat and underwear, and the families, the children, the couples, the young and the old, lovers all, taking pictures, laughing, crossing against the lights.

This girl in Times Square stands by the wall while others cross against the light.”

Lily turned away from the door and stared out the open window into the night, on Amy’s bed, alone.

Allison Quinn (#ulink_01f0e857-c912-5c46-acea-5b3c7b3f595e)

There once was a woman who lived for love. Now she stood and stared out her window. Outside she saw green palms and red rhododendrons and a blue sky and an aqua ocean and gray cliffs and black volcanoes and white sands. She did not look inside her room. She was waiting for her husband to come back from buying mangoes. It was taking him forever. She moved the curtain slightly out of the way to catch a movement outside, and sighed, remembering once upon a time when she was young, and had dreamed for the sky and the sea and plenty.

And now she had it.

And once a man put on a record on an old Victrola and took her dancing through their small bedroom. The man was handsome, and she was beautiful, and they spoke a different language then. “The look of love is in your eyes … ” Now the man went for walks by himself under the palms and over the sands. He wet his feet in the ocean and his soul in the ocean too, and then he walked to the fruit stand and bought the juicy mangoes, and the perky salesgirl said they were the best yet, and he glanced at her and smiled as he took them from her hand.

The woman stepped away from the window. He was always walking, always leaving the house. But she knew—he wasn’t leaving the house, he was leaving her. He just couldn’t stand the thought of being with her for an hour alone, couldn’t stand the thought of doing something she wanted instead of everything he wanted. When she didn’t do what he wanted, how he sulked—like a baby. That’s all he was, a baby. Do it my way or I won’t talk to you, that was him. Well, could she help it if mornings were not the best time for her? Could she help it that in the mornings she could not get up and go for a walk and a swim in all that sunshine. It depressed her beyond all sane measure that at eight in the morning the ocean was so warm, the sun was so strong. If only it would rain, just once! She was done with that damn ocean. And that sun. Those mangoes, that tuna sashimi, that volcanic ash. Done with it.

She bought heavy room-darkening curtains and drew them tight to keep out the day, to make believe it was still night.

She made believe about a lot these days.

She couldn’t understand, where was he? When was he going to grace her with his presence? Didn’t he know she was sick, she was hungry? Didn’t he know she had to eat small meals? That’s just it, he didn’t care what she needed, all he cared about was what he needed. Well, she wasn’t going to put a single bite in her mouth. If she fainted from low blood sugar and broke a bone, so much the better. She’d see how he felt then, that he was out all morning and didn’t make his sick wife breakfast. She’d see how he’d explain that one to her mother, to their kids. She’d be damned if she put a spoon of sugar into her mouth.

The bedroom door opened slightly. “I’m back. Have you eaten?”

“Of course I haven’t eaten!” she spat. “Like you even care. I could croak here like a rat, while you’re glibly walking in your fucking Maui without a single thought for me!”

… a look that time can’t erase …

Silently the door closed, and she remained in her darkened room with the drawn shades in the ginger Maui morning, alone.

A Man and a Woman (#ulink_97ff50e4-d5d4-5456-9a04-ff3d5fd1c4b5)

It’s late Friday night and they’re in her apartment. They had been to dinner, she invited him for a drink and dancing in a wine bar near where she lives. He said no. He always says no—drinking and dancing in wine bars is not his strong suit—but you have to give it to her—she’s plucky. She keeps on asking. Now they’re in her bed, and whether this is his strong suit, or whether she has no more attractive options, he doesn’t know but she’s been showing up every Friday night, so he must be doing something right, though he’d be damned if he knows what it is. The things he gives her, she can get anywhere.

And after he gives them to her, and takes some for himself, she falls contentedly asleep in the crook of his arm, while he lies opened-eyed and in the yellow-blue light coming from the street counts the tin tiles of her tall ceiling. He may look content also—in tonight’s ostensible enjoyment of his food and his woman—to someone who has observed him scientifically and empirically, wholly from without. But now in a perversion of nature, the woman is asleep and the man is staring at the ceiling. So what is in him wholly from within?

He is counting the tin tiles. He has counted them before, and what fascinates him is how every time he counts them this late at night, he comes up with a different number.

After he is sure she is asleep, he disentangles himself, gets up off the bed, and takes his clothes into the living room.

She comes out when his shoes are on. He must have jangled his keys. Usually she does not hear him leave. It’s dark in the room. They stare at each other. He stands. She stands. “I don’t understand why you do this,” she says.

“I just have to go.”

“Are you going home to your wife?”

“Stop.”

“What then?”

He doesn’t reply. “You know I go. I always go. Why give me a hard time?”

“Didn’t we have a nice evening?”

“We always do.”

“So why don’t you stay? It’s Friday. I’ll make you waffles for breakfast.”

“I don’t do waffles for Saturday breakfast.”

Quietly he shuts the door behind him. Loudly she double bolts and chains it, padlocking it if she could.

He is outside on Amsterdam. On the street, the only cars are cabs. The sidewalks are empty, the few barflies straggle in and out. Lights change green, yellow, red. Before he hails a taxi back home, he walks twenty blocks past the open taverns at three in the morning, alone.

PART I (#ulink_693aa2bf-5379-5ae8-ad05-d15428d0b7d1)

IN THE BEGINNING (#ulink_693aa2bf-5379-5ae8-ad05-d15428d0b7d1)

You call yourself free? Free from what? What is that to Zarathustra! But your eyes should announce to me brightly: free for what?

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

1 (#ulink_47f34575-194a-5a70-aee7-5969e7143d0a)

Appearing To Be One Thing When it is in Fact Another (#ulink_47f34575-194a-5a70-aee7-5969e7143d0a)

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

And again:

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Reality: something that has real existence and must be dealt with in real life.

Illusion: something that deceives the senses of mind by appearing to exist when it does not, or appearing to be one thing when it is in fact another.

Miracle: an event that appears to be contrary to the laws of nature.

49, 45, 39, 24, 18, 1.

Lily stared at the six numbers in the metro section of The Sunday Daily News. She blinked. She rubbed her eyes. She scratched her head. Something was not right. Amy wasn’t home, there was no one to ask, and Lily’s eyes frequently played tricks on her. Remember last year in the delivery room when she thought her sister gave birth to a boy, and shouted ‘BOY!’ because they all so wanted a boy, and it turned out to be another girl, the fourth? How could her mind have added on a penis? What was wrong with her?

Leaving her apartment she went down the narrow corridor to knock on old Colleen’s door in 5F. Fortunately Colleen was always home. Unfortunately Colleen, here since she was a young lass during the potato famine, was legally blind, as Lily to her dismay found out, because Colleen read 29 instead of 49, and 89 instead of 39. By the time Colleen finished with the numbers, Lily was even less sure of them. “Don’t worry about it, me dearie,” said Colleen sympathetically. “Everyone thinks they be seeing the winnin’ numbers.”

Lily wanted to say, not her, not she, not I, as ever just a smudge in the reflected sky. I don’t see the winning numbers. I might see penises, but I don’t imagine portholes of the universe that never open up to me.

Lily was born a second-generation American and the youngest of four children to a homemaker mother who always wanted to be an economist, and a Washington Post journalist father who always wanted to be a novelist. He loved sports and was not particularly helpful with the children. Some might have called him insensitive and preoccupied. Not Lily.

Her grandmother was worthy of more than a paragraph in a summary of Lily’s life at this peculiar juncture, but there it was. In Lily’s story, Danzig-born Klavdia Venkewicz ran from Nazi-occupied Poland with her baby, Lily’s mother, across destroyed Germany. After years in three displaced persons camps, she managed to get herself and her child on a boat to New York. She had called the baby Olenka, but changed it to a more American-sounding Allison, just as she changed her own name from Klavdia to Claudia and Venkewicz to Vail.

Lily lived all her life in and around the city of New York. She lived in Astoria, and Woodside, and Kew Gardens, and when they really moved up in the world, Forest Hills, all in the borough of Queens. Her dream was to live in Manhattan, and now she was living it, but she had been living it broke.

When George Quinn, who had been the New York City correspondent for the Post, was suddenly transferred down to D.C. because of cost-cutting internal restructuring, Lily refused to go and stayed with her grandmother in Brooklyn, commuting to Forest Hills High School to finish out her senior year. That was some wild year she had without parental supervision. Having calmed down slightly, she went to City College of New York up on 138th Street in Harlem partly because she couldn’t afford to go anywhere else, her parents having spent all their college savings on her brother—who went to Cornell. Her mother, fortunately guilt-ridden over going broke on Andrew, paid Lily’s rent.

As far as the meager rations of youthful love, Lily, too quiet for New York City, went almost without until she found Joshua—a waiter who wanted to be an actor. His red hair was not what drew her to him. It was his past sufferings and his future dreams—both things Lily was a tiny bit short on.

Lily liked to sleep late and paint. But she liked to sleep late most of all. She drew unfinished faces and tugboats on paper and doodles on contracts, and lilies all over her walls, and murals of boats and patches of water. She hoped she was never leaving the apartment because she could never duplicate the work. She had been very serious about Joshua until she found out he wasn’t serious about her. She read intensely but sporadically, she liked her Natalie Merchant and Sarah McLachlan loud and in the heart, and she loved sweets: Mounds bars, chocolate-covered jell rings, double-chocolate Oreos, chewy Chips-Ahoy, Entenmann’s chocolate cake with chocolate icing, and pound cake.

One of her sisters, Amanda, was a model mother of four model girls, and a model suburban wife of a model suburban husband. The other sister, Anne, was a model career woman, a financial journalist for KnightRidder, frequently and imperfectly attached, yet always impeccably dressed. Her brother, Andrew, Cornell having paid off, was a U.S. Congressman.

The most interesting things in Lily’s life happened to other people, and that’s just how Lily liked it. She loved sitting around into the early morning hours with Amy, Paul, Rachel, Dennis, hearing their stories of violent, experimental love lives, hitchhiking, South Miami Beach Bacchanalian feasts. She liked other people to be young and reckless. For herself, she liked her lows not to be too low and her highs not to be too high. She soaked up Amy’s dreams, and Joshua’s dreams, and Andrew’s dreams, she went to the movies three days a week—oh the vicarious thrill of them! She meandered joyously through the streets of New York, read the paper in St. Mark’s Square, and lived on in today, sleeping, painting, dancing, dreaming on a future she could not fathom. Lily loved her desultory life, until yesterday and today.

Today, this. Six numbers.

And yesterday Joshua.

Ten good things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. TV is permanently off.

9. Don’t have to share my bagel and coffee with him.

8. Don’t have to pretend to like hockey, sushi, golf, quiche, or actors.

7. Don’t have to listen to him complaining about the short shrift he got in life.

6. Don’t have to listen about his neglectful father, his nonexistent mother.

5. Don’t have to get my belly button pierced because he liked it.

4. Don’t have to stay up till four pretending we have similar interests.

3. No more wet towels on my bed.

2. Don’t have to blame him for the empty toilet roll.

And the number one good thing about breaking up with Joshua:

1. Don’t have to feel bad about my small breasts.

Ten bad things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. There

9. Are

8. Things

7. About

6. You

5. I

4. Could

3. Never

2. Love.

Oh, and the number one bad thing about breaking up with Joshua …

1. Without him, I can’t pay my rent.

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Her hair had been down her back, but last week after he left Lily had sheared it to her neck, as girls frequently did when they broke up with their boyfriends. Snip, snip. It pleased Lily to be so self-actualized. To her it meant she wasn’t wallowing in despair.

Barely even needing to brush the choppy hair now, Lily threw on her jacket and left the apartment. She headed down to the grocery store where she had bought the ticket. After going down four of the five flights, she trudged back upstairs—to put her shoes on. When she finally got to the store on 10th and Avenue B, she opened her mouth, fumbled in her pocket, and realized she’d left the ticket by the shoe closet.

Groaning in frustration, tensing the muscles in her face, Lily grimaced at the store clerk, a humorless Middle Eastern man with a humorless black beard, and went home. She didn’t even look for the ticket. She saw the mishaps as a sign, knew the numbers couldn’t have matched, couldn’t have. Not her lottery ticket! She lay on Amy’s bed and waited for the phone to ring. She stared out the window, trying to make her mind a blank. The bedroom windows faced the inner courtyard of several apartment buildings. There were many greening trees and long narrow yards. Most people never pulled down the shades on the windows that faced inward. The trees, the grass were perceived to be shields from the world. Shields maybe from the world but not from Lily’s eyes. What kind of a pervert stared into other people’s windows anyway?

Lily stared into other people’s windows. She stared into other people’s lives.

One man sat and read the paper in the morning. For two hours he sat. Lily drew him for her art class. She drew another lady, a young woman, who, after her shower, always leaned out of her window and stared at the trees. For her improv class, she drew her favorite—the unmarried couple who in the morning walked around naked and at night had sex with the shades up and the lights on. She watched them from behind her own shades, embarrassed for them and herself. They obviously thought only the demons were watching them, judging from the naughty things they got up to. Lily knew they were unmarried because when he wasn’t home, she read “Today’s Bride” magazine and then fought with him each Saturday night after drinking.

Lily had drawn their cat many times. But today she got out her sketchbook and mindlessly penciled in the number, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49. It couldn’t be, right? It was just a cosmic mistake? Of course! Of course it was, the numbers may have been correct, but they were for a different date: how many times has she heard about that? She sprung up to check.

No, no. Numbers matched. Date matched, too.

She went into Amy’s room. She and Amy were going to go to the movies today, but Amy wasn’t home, and there was no sign of her; she hadn’t come home from wherever she was yesterday.

Lily waited. Amy always gave the appearance of coming right back.

Lily. Her mother forgot to put the third L into her name. Though she herself was an Allison with a double L. Oh, for God’s sake, what was she thinking about? Was Lilianne jealous of her mother’s double L? Where was her mind going with this? Away from six numbers. Away from 49, 45, 39, 24, 18, 1.

She had a shower. She dried her pleasingly boyish hair, she looked through The Daily News and settled on the 2:15 at the Angelica of The Butcher Boy.

While walking past the grocery store she thought of something, and taking a deep breath, stepped inside.

“Excuse me,” Lily said, coughing from acute discomfort. “What’s the lottery up to at the last drawing?” She felt ridiculous even asking. She was red in the pale face.

“For how many numbers?” the clerk said gruffly.

Not looking at him, Lily thought about not replying. She finally said to the Almond Joy bars, “All of them.”

“All six? Let’s see … ah, yes, eighteen million dollars. But it depends who else wins.”

“Of course.” She backed out of the store.

“Usually a few people win.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Did your numbers come in?”

“No, no.”

Lily got out as fast as she could.

18 was one of the numbers. So was 1.

That was in April. After Joshua, Lily swore off men for life, concluding that there wasn’t a single decent one in the entire tri-state area, except for Paul and he was incontrovertibly (as if there were any other way) gay. Rachel kept offering her somewhat unwelcome matchmaking services, Paul and Amy kept offering their welcome support services. They went to see other movies besides The Butcher Boy, and The Phantom Menace and sat until all hours drinking tequila and discussing Joshua’s various demerits to make Lily feel better. And eventually both the tequila and the discussions did.

Lily—making her lottery ticket into wall art for the time being—affixed it with red thumbtacks to her corkboard that had thumb-tacked to it all sorts of scraps from her life: photos of her together with her brother, some of her two sisters, photos of her grandma, photos of her six nieces, photos of her father, of her cat who died five years ago from feline leukemia, of Amy, report cards from college (not very good) and even from high school (not much better). The wall used to have photos of Joshua, but she took them down, drew over his face, erasing him, leaving a black hole, and then put them back. And now her lottery ticket was scrap art, too.

And Amy, who had prided herself on reading only The New York Times, never read a rag like The Daily News, and because she hadn’t, she didn’t know what Lily’s grandmother knew and brought to Lily’s attention one Thursday when Lily was visiting.

Before she left, she knocked on Amy’s door, and when there was no answer she slightly opened it, saying “Ames?” But the bed was made, the red-heart, white hand-stitched quilt symmetrically spread out in all the corners.

Holding onto the door handle Lily looked around, and when she didn’t see anything to stop her gaze she closed the door behind her. She left Amy a note on her door. “Ames, are we still on for either The Mummy or The Matrix tomorrow? Call me at Grandma’s, let me know. Luv, Lil.”

She went to Barnes & Noble on Astor Place and bought June issues of Ladies Home Journal, Redbook, Cosmopolitan (her grandmother liked to keep abreast of what the “young people were up to”), and she also picked up copies of National Review, American Spectator, The Week, The Nation, and The Advocate. Her grandmother liked to know what everybody was up to. In her grandmother’s house the TV was always on, picture in picture, CNN on the small screen, C-Span on the big. Grandma didn’t like to listen to CNN, just liked to see their mouths move. When Congress was in session, Grandma sat in her one comfortable chair, her magazines around her, her glasses on, and watched and listened to every vote. “I want to know what your brother is up to.” When Congress was not in session, she was utterly lost and for weeks would putter around in the kitchen or clean obsessively, or drink bottomless cups of strong coffee while she read her news-magazines and occasionally watched C-Span for parliamentary news from Britain. To the question of what she had done with herself before C-Span, Grandma would reply, “I was not alive before C-Span.”

She lived in Brooklyn on Warren Street, between Clinton and Court in an ill-kept brownstone marred further not by the disrepair of the front steps but by the bars on the windows. And not just on the street-level windows. Or just the parlor windows. Or the second floor windows, or the third. But all the windows. All windows in the house, four floors, front and back, were covered in iron bars. The stone façade on the building itself was crumbling but the iron bars were in pristine shape. Her grandmother, for reasons that were never made clear, had not ventured once out of her house—in six years. Not once.

Lily rang the bell.

“Who is it?” a voice barked after a minute.

“It’s me.”

“Me who?” Strident.

“Me, your granddaughter.”

Silence.

“Lily. Lily Quinn.” She paused. “I used to live with you. I come every Thursday.”

A few minutes later there was the noise of the vestibule door unlatching, of three locks unlocking, of the chain coming off, and then came the noise of the front door’s three dead-bolt locks unbolting, of a titanium sliding lock sliding, of another chain coming off, and finally of the front door being opened, just a notch, maybe eight inches, and a voice rushing through, “Come in, come in, don’t dawdle.”

Lily squeezed in through the opening, wondering if her grandmother would open the door wider if Lily herself were wider. Would she, for example, open the door wider for Amanda who’d had four kids?

Inside was cool and dark and smelled as if the place hadn’t been aired out in weeks. “Grandma, why don’t you open the windows? It’s stuffy.”

“It’s not Memorial Day, is it?” replied her grandmother, a white-haired, small woman, portly and of serious mien, who took the bags out of Lily’s hands and carried them briskly to the kitchen at the back of the house.

Grandma’s home was tidy except for the newspapers that were piled on top of the round kitchen table, The New York Times first, then The Observer, then The Wall Street Journal, and then the tabloids, Newsday, Post and News.

“Do you want a cup of tea?”

“No, I’m going to have to get going soon.”

“Get going! You just got here.”

“Last week of finals, Grandma. Perhaps you’ve heard.” Lily smiled just in case her grandmother decided to take offense.

“I’ve heard, I’ve heard plenty. How are the subways this morning?”

“They’re fine—”

“Oh, sure, you can’t even fake a polite answer anymore. Did you stand far from the yellow line?”

“I did better than that,” said Lily, putting milk in the refrigerator. “I sat down on the bench.”

Her grandmother squirmed. “Oh, Lily, how is that better? Sitting on that filth-covered bench, how many of those people who sat on it before washed their clothes that morning? And they’re sitting next to you, breathing on you, watching over your shoulder, seeing what you’re reading, hearing your Walkman songs, such loss of privacy. All the homeless sit on that bench.”

Lily wanted to remark that, no, all the homeless were lying on the steps of the 53rd Street church on Fifth Avenue, but said nothing.

“From now on, I give you money, you take a cab to see me.”

Lily wanted to button up her jacket, if only she had one. “So what’s going on with you?”

“I’ll tell you what’s going on,” said her grandmother, Claudia Vail, seventy-nine years old, widow, war survivor, death-camp survivor, all cataracts removed, a new pacemaker installed, arthritis in check, no mysterious bumps, growths, or distensions, but widow first and foremost, “On Sunday a child fell out of his sixth-floor apartment in the projects and died. This is on a Sunday. What are the parents doing if not looking after their child on a Sunday? On Monday a five-year-old girl was stabbed and killed by her brother and his friend who were supposed to be looking after her. The mother when she returned home from work said, ‘It’s so unlike him. He’s usually such a nice boy.’ Then we find out that this boy, age eleven, had already spent three years in juvenile detention for beating his grandmother blind. The mother apparently overlooked that when she left her child with him.”

“Grandma,” Lily said feebly, putting up her hands in a defensive gesture.

“Last Friday, a vegan couple in Canarsie were arrested for feeding their child soybeans and tofu from the day she was born. That mother’s milk must have been all dried up because at sixteen months the child weighed ten pounds, the weight of a two-to-three-month-old.”

“Grandma,” said Lily helplessly. Her grandmother was cornering her between herself and the fridge. Lily could tell by her grandmother’s eyes she was a long way from done. “Did anything happen on Saturday?”

“On Saturday your sister and that no-good man of hers came over—”

“Which sister?”

“And I told her,” Claudia continued, “that she was lucky not to have any children.”

“Oh. That one. Grandma, if life is no good here, why don’t you move? Move to Bedford with Amanda. Nothing ever happens in Bedford. Hence the name. City of beds.”

“Who said life is not good here? Life is perfect. And are you insane? With Amanda and her four kids? So she could take care of me, too? Why would I do that to her? Why would I do that to myself?”

“Did José bring your groceries this week?” The kitchen looked a bit bare.

“Not anymore. I fired him.”

“You did?” Lily was alarmed. Not for her grandmother—for herself. If José was no longer delivering groceries, then who was going to? “Why did you fire him?”

“Because in the paper last Saturday was a story of an old woman just like me who was robbed by the delivery boy—robbed and raped, I think.”

“Was it José?” Lily said, trying not to sound weary. Struggling not to rub the bridge of her nose.

“No, it wasn’t José. But one can never be too careful, can one, Liliput?”

“No, one certainly cannot.”

“Your door, is it locked? To your bedroom?” Grandmother shook her head. “Are you still living with those bums, those two who cannot keep their sink clean? Yes, your father told me about his visit to your abode. He told me what a sty it was. I want you to find a new place, Lil. Find a new place. I’ll pay the realtor fee.”

Lily was staring at her grandmother with such confusion that for a moment she actually wondered if perhaps she’d never spoken of her living arrangements with her grandmother, or whether there had been too many residential changes for her grandmother to keep track of.

“Grandma,” she said slowly. “I haven’t lived with those bums, as you like to call them, in years. I’ve been living with Amy, in a different apartment, remember? On 9th Street and Avenue C?” She looked at her grandmother with concern.

Her grandmother was lost in thought. “Ninth Street, Ninth Street,” she muttered. “Why does that ring a bell … ?”

“Um, because I live there?”

“No, no.” Claudia stared off into the distance. Suddenly her gaze cleared. “Oh yes! Last Saturday, same day as the old woman’s battery and rape, a small piece ran in the Daily News. Apparently three weeks ago there was a winning lottery ticket issued at a deli on the corner of 10th and Avenue B, and the winner hasn’t come to claim it yet.”

Lily was entirely mute except for the whooshing sound of her blinking lashes, sounding deafening even to herself. “Oh, yeah?” she said and could think of nothing else. The sink faucet tapped out a few water droplets. The sun was bright through the windows.

“Can you imagine? The News publishes the numbers every day in hopes that the person recognizes them and comes forward. Eighteen million dollars.” She tutted. “Imagine. By the way, they publish the numbers so often I know them by heart. Some of the numbers I could have chosen myself. Forty-nine, the year I came to America, thirty-nine, the year my Tomas went to war. Forty-five, my Death March.” She clucked with delight and disappointment. “Do you go to that deli?”

“Um—not anymore.”

“Maybe it’s lost,” said Claudia. “Maybe it’s lying unclaimed in the gutter somewhere because it fell out of the winner’s pocket. Watch the sidewalks, Liliput, around your building. An unsigned lottery ticket is a bearer bond.”

“A what what?”

“A bearer bond.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means,” said Claudia, “that it belongs to the bearer. You find it, it’s yours.”

Why did Lily immediately want to go home and sign her ticket? “What are the chances of finding a winning lottery ticket, Grandma?”

“Better than the chances of winning one,” replied Claudia in a no-nonsense voice. “So how is that Amy? She’s the one who spent last Thanksgiving with us instead of that no-good boyfriend of yours? How is he?”

Are there any men who are not no-good? Lily wondered but was too sheepish to ask, since it appeared that her grandmother was right at least about Joshua. It was time she told her. “She is fine, and … we’re no longer together. He moved out a month ago.”

For a moment her grandmother was silent, and then she threw up her arms to the ceiling. “So there is a God,” she said.

Lily’s face must not have registered the same level of boundless joy because Claudia said, “Oh, come on. You should be glad to be rid of him.”

“Well … not as glad as you.”

“He’s a bum. You would have supported him for the rest of your life, the way your sister supports her no-good boyfriend.”—and then without a break—“Is Amy graduating with you in a few weeks?”

“Not with me,” said Lily evasively. She didn’t want to lie, but she also didn’t want to tell her grandmother that Amy was actually graduating.

“When is it exactly?”

“May 28, I think.”

“You think?”

“Everything is all right, Grandma, don’t worry.”

“Come in the living room,” Claudia said. “I want to talk to you about something. Not about the war. I’ll save that for Saturday’s poker game.” She smiled. “Are you coming?”

“Can’t. Have to work.” They sat on the sofa covered in plastic. “Grandma, you live here, why don’t you take the Mylar off? That’s what people do when they live someplace. They take the plastic off.”

“I don’t want to dirty all my furniture. After all, you’ll be getting it when I die. Yes, yes, don’t protest. I’m leaving all my furniture to you. You don’t have any. Now stop shaking your head and look what I have for you.”

Lily looked. In her fingers, Grandmother held an airplane ticket.

“Where am I going?”

“Maui.”

Lily shook her head. “Oh, no. Absolutely not.”

“Yes, Lily. Don’t you want to see Hawaii?”

“No! I mean, yes, but I can’t.”

“I got you an open-ended ticket. Go whenever you want for as long as you want. Probably best to go soon though, before you get a real job. It’ll be good for you.”

“No, it won’t.”

“It will. You’re looking worn around the gills lately. Like you haven’t slept. Go get a tan.”

“Don’t want sleep, don’t want a tan, don’t want to go.”

“It’ll be good for your mother.”

“No, it won’t. And what about my job?”

“What, the Noho Star is the only diner in Manhattan?”

“I don’t want to get another waitressing job.”

Claudia squeezed Lily’s hands. “You need to be thinking beyond waitressing, Liliput. You’re graduating college. After six years, finally! But right now your mother could use you in Hawaii.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Let’s just say,” Grandma said evasively, “I think she’s feeling lonely. Amanda is busy with her family, Anne is busy, I don’t even know with what. Oh, I know she pretends she works, but then why is she always broke? Your brother, he’s busy, too, but since he’s actually running our country, I’ll give him a break for not calling his own mother more often. Your mother is feeling very isolated.”

“But Papi is with her. He retired to be with her!”

“Yeah, well, I don’t know how that whole retirement thing is working out. Besides you know your father. Even when he’s there, he’s not there.”

“We told them not to move to Hawaii. We told them about rock fever, we told them about isolation. We told them.”

“So? They’re sixty. You’re twenty-four and you don’t listen. Why should they listen?”

“Because we were right.”

“Oh, Liliput, if everyone listened to the people who were right there would be no grief in the world, and yet—do you want me to go through last week with you again?”

“No, no.”

“Was there grief?”

“Some, yes.”

“Go to your mother. Or mark my words—there will be grief there, too.”

Lily struggled up off the 1940s saran-wrap-covered yellow and yellowing couch that someday would be hers. “There’s grief there aplenty, Grandma.”

She was vacillating on Hawaii as she vacillated on everything—painstakingly. Amy was insistent that Lily should definitely go. Paul thought she should go. Rachel thought she probably should go. Rick at Noho Star said he would give her a month off if she went now before all the kids came back from college and it got busy for the summer.

She called her brother over the weekend to see what he thought, and his wife picked up the phone and said, “Oh, it’s you.” And then Lily heard into the phone, “ANDREW! It’s your sister!” and when her brother said something, Miera answered, “The one who always needs money.” And Andrew came on the phone laughing, and said, “Miera, you have to be more specific than that.”

Lily laughed herself. “Andrew, I need no money. I need advice.”

“I’m rich on that. I’ll even throw you a couple of bucks if you want.”

His voice always made her smile. Her whole life it made her smile. “Can you see me for lunch this week?”

“Can’t, Congress is in session. What’s up? I was going to call you myself. You won’t believe who’s staying with me.”

“Where?”

“In D.C.”

“Who?”

“Our father, Lil.”

“What?”

“Yup.”

“He’s in D.C.? Why?”

“Aren’t you the journalist’s daughter with the questions. Why, I don’t know. He left Maui with two big suitcases. I think he is thinking of un-retiring. His exact words? ‘No big deal, son. I’m just here to smooth out the transition for Greenberger who’s taking over for me.’”

“Meaning …”

“Meaning, I can’t take another day with your mother.”

“Oh, Andrew, oh, dear.” Lily dug her nails into the palms of her hands. “No wonder Grandma bought me a ticket to go to Maui. She’s so cagey, that Grandma. She never comes out and tells me exactly what she wants. She is always busy manipulating.”

“Yes, she wants you to do what she wants you to do but out of your own accord.”

“Fat chance of that. When is Papi going back? I don’t want to go unless he’s there.”

“You’ll be waiting your whole life. I don’t think he’s going back.”

“Stop it.”

“Where are you?”

“I’m home, why?”

“Are you … alone?”

“Yes.” Lily lowered her voice. “What do you want to tell me?”

“Are you sitting … listening?”

“Yes.”

“Go to Maui now, Liliput. I can’t believe I’m saying this. But you should go. Really. Get out of the city for a while.”

“I can’t believe you’re saying this. I don’t see you going.”

“I’d go if I weren’t swamped. Quartered first, but I’d go.”

“Yes, exactly.”

“Did I mention … gladly quartered?”

After having a good chuckle, Andrew and Lily made a deal—he would work on their father in D.C. in between chairing the appropriations committee and filibustering bill 2740 on farm subsidies, and she would go and soothe their mother in between sunbathing and tearing her hair out.

“Andrew, is it true what I heard from Amanda, are you running for the U.S. Senate seat in the fall?”

“I’m thinking about it. I’m exploring my options, putting together a commission. Don’t want to do it if I can’t win.”

“Oh, Andrew. What can I do? I’ll campaign for you again. Me and Amy.”

“Oh, you girls will be too busy with your new lives to help me in the fall, leaving school, getting real jobs. But thanks anyway. I gotta go. I’ll call you in Maui. You want me to wire you some money?”

“Yes, please. A thousand? I’ll pay you back.”

“I’m sure. Is that why you keep buying lottery tickets every week? To pay me back?”

“You know,” said Lily, “I’ve stopped buying those lottery tickets. I love you.”

“Love you, too, kid.”

2 (#ulink_c8b5c43e-3960-5d6f-9d1f-ac73602037da)

Hawaii (#ulink_c8b5c43e-3960-5d6f-9d1f-ac73602037da)

Hawaii was not Poland. It was not the wetlands of northern Danzig, rainy, cold, swampy, mosquito-infested Danzig whence Allison had sprung during war. Hawaii was the anti-Poland. Two years ago Lily’s mother and father had gone on an investigative trip to Maui and came back at the end of a brief visit with a $200,000 condo. Apparently they learned everything they could about Maui in two weeks—how much they loved it, how beautiful it was, how clean, how quiet, how fresh the mangoes, how delicious the raw tuna, how warm the water, and how much they would enjoy their retirement there.

Lily knew how her father was taking to his retirement, enjoying it now in his only son’s congressional apartment in the nation’s capital.

How her mother was taking to Hawaii Lily also could not tell right away because her mother was not there to pick her up from Kahului airport. After she had waited a suitable amount of time—which was not a second over ninety minutes—she called her mother, who had come on the phone and sounded as if she had been sleeping. Lily took a taxi. The narrow road between the mountain pass leading to the Kihei and Wailea side of Maui where her parents lived was pretty but was somehow made less attractive by Lily’s crankiness at her mother’s non-appearance. She rang the doorbell for several minutes and then ended up having to pay the cab driver herself ($35!!!—the equivalent of all tips for a four-hour morning shift). After ringing the bell, Lily tried the door and found it open. Her mother was in the bedroom asleep on top of the bed and would not be awakened.

Some hours later, Allison stumbled out of her room. Lily was watching TV.

“You’re here,” she said, holding on to the railing that led down two steps from the hallway to the sunken living-room.

Lily stood up. “Mom, you were supposed to pick me up from the airport.”

“I didn’t know you were coming today,” said her mother. “I thought you were coming tomorrow.” She spoke slowly. She was wearing a house robe and her short hair was gray—she had stopped coloring it. Her face was puffy, her eyes nearly swollen closed.

Lily was going to raise her voice, say a few stern things, but her mother looked terrible. She wasn’t used to that. Her mother was usually perfectly coiffed, perfectly made up, perfectly dressed, perfect. Lily turned her frustrated gaze back to the TV. Allison stood for a moment, then squared her shoulders and left the living room. Soon Lily got up and went to bed in her father’s room. Of course Grandma was right—something needed fixing. But Lily was the child, and Allison was the mother. The child wasn’t supposed to fix the mother. The mother was supposed to fix the child. That was the natural order of things in the universe.

The next morning Allison came out, all showered and fresh, with mascara and lipstick on her face. Her hair was brushed, pulled back, her eyebrows were tweezed. There was even polish on the nails. She apologized for yesterday’s mishap, and made Lily eggs and coffee as they talked about Lily’s life a little bit, and it was then that Lily broke the bad news that she didn’t think she would be graduating this year because she didn’t think she had enough credits.

“How many credits are you short?” asked Allison.

“A few.”

“Wait till your father finds out.”

“Mom, you can’t still be threatening me with my father. I’m twenty-four.”

“Have you noticed by the way that your father isn’t here?”

Lily coughed. “I’ve noticed. Andrew told me he’s in D.C.”

Now Allison coughed. “Yes, whatever. He said he was going on freelance business. He said Andrew asked him for help in preparation for the fall campaign. It’s all lies. That’s all they both do, is lie.” Turning away, she got up and went away into her bedroom. When Lily knocked to ask if she was coming to the beach, Allison said she wasn’t feeling up to going.

The Mauian beach couldn’t help but erase some of the bad taste in Lily’s mouth. She imagined being here with Joshua, having money, a car, snorkeling, whale watching, biking at dawn to volcanoes, hiking in rainforests, swimming in water that in her great enthusiasm felt like liquid gold. It was enough to get her good and properly depressed about her own situation and to forget her mother and what more could one want from paradise, but to forget your mother’s troubles and remember your own?

Strangely, Hawaii was able to overcome even romantic disillusionments, for it looked and smelled and felt as if God were watching from up close. She had never seen water so green or the sky so blue, or the rhododendrons so red. She had never seen anyone happier than a guy who was swinging on a hammock in his backyard on the ocean and reading his book. Lily didn’t know how he could be reading. You couldn’t look away from that ocean. She was not hot, and when she walked into the water she was not cold. The water and the air were the same temperature. When she finished swimming and came out, she did not feel wet. She thought she could not get a suntan in weather that felt so mild, yet when she pulled away the strap of her bathing suit, she saw white underneath it, and next to it skin that was decidedly not white. That made her incredulous and happy and when she returned she was ready for rapprochement.

But in the darkened condo, Allison was still lying down, and Lily, not wanting to disturb her mother, went into her own room. It was only four o’clock in the afternoon.

She had a nap, and at six when she came out, her mother, her hair all done, and her make-up on, was ironing a skirt in the living room. “Come on, do you have anything nice to wear? Or do you want me to lend you something? I’ll take you to a wonderful oceanside café your father and I go to sometimes. It’s dressy, though, can’t go there in that little bikini you’re wearing.”

“I have a dress.”

“Well, let’s go. They have great lobster.”

All dressed and perfumed they went. Watching her mother walk in so elegant, so slim, so tall in her high-heeled shoes, smile at the host and be escorted on his arm to their beachside table, Lily thought that her father was right—when Allison was on, there was no woman in the room, regardless of age, more beautiful. Anne, Amanda, Lily, they inherited some of their mother’s remarkable physical traits, but parceled out, not in total, whereas their mother had all her remarkable physical traits to herself. The thick, wavy, auburn hair, the wide apart, slightly slanted gray eyes, the regal nose, the high cheekbones, the perfect mouth, elegant and slender like the rest of her. Amanda got the hair and the nose, Anne got the height and the cheekbones and the slimness. Anne got a lot. Lily got no height, no cheekbones, no hair, and no gray eyes. She got the slant of the eyes and a certain fluid grace of the mouth and the neck and the arms.