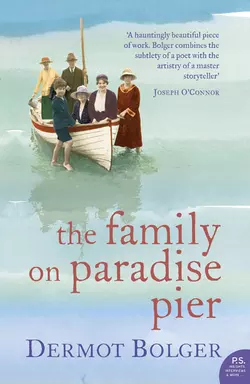

The Family on Paradise Pier

Dermot Bolger

A stunning historical saga set in the early decades of the twentieth century which follows the lives and loves of one extraordinary family.We first meet the Goold Verschoyle children in 1915. Though there is a war going on in the world outside, they seem hardly touched by it – midnight swims, flower fairies and regatta parties form the backdrop to their enchanted childhood. But as they grow older, changes within Ireland and the wider world encroach upon the family’s private paradise.Turbulent times – the Irish war of independence, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II – are woven into the tapestry upon which this magical story is spun. Events in Spain, Russia and London draw the children in different directions: one travels to Moscow to witness Communism at first had; another runs away to England to take part in the General Strike and then heads off to the Civil War in Spain; another follows the more conventional route of marriage and family.Based upon the extraordinary lives of a real-life Anglo-Irish family, Bolger’s novel superbly recreates a family in flux, driven by idealism, wracked by argument and united by love and the vivid memories of childhood. ‘The Family on Paradise Pier’ shows Bolger at the height of his powers as a master storyteller. A spellbinding and magnificent achievement.

The Family on Paradise Pier

Dermot Bolger

For Donnacha and Diarmuid

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u0f2bc14c-251c-584c-8cf5-26778b7bbaa7)

Title Page (#u73fd2f25-28df-5733-bbce-4155330b2f03)

Prologue 1941 (#u02e2d6f5-4c60-58e3-90a1-9dc32d9aa8c5)

PART ONE 1915–1935 (#u98c6f1df-c8d4-58df-99a3-bb666c5f8b61)

ONE The Picnic (#ucb4b1481-4c9d-5c46-8a53-98fb0ac3036f)

TWO The News (#ucfbbac0f-ee6e-5e48-a65c-0877c4bc4feb)

THREE Four Thousand Lamps (#ua6fcb1fe-b8d5-5f73-ae7c-be1505c1c057)

FOUR The Motor (#u7e4ca006-0d8d-5c8a-b357-9f6b190c41f4)

FIVE The Boat (#ued9abd27-fc3a-5684-8dcb-eb23e5c1eaa5)

SIX The Docks (#ub284c6db-0773-521b-8ff6-c1066c51458f)

SEVEN The Exiles (#u65d2a3fb-d5d8-58fb-b843-ff5c4ec52747)

EIGHT The Studio (#u36f450e1-2496-5614-86f1-613745d5ae19)

NINE Not a Penny off the Pay (#ueb7b45d8-9845-542d-87f3-aa73796a7286)

TEN The Turf Cutters (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN The Two Fredericks (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE Eccles Street (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN Deep in the Woods (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN Chelsea (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN The Visit (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN The Letter (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN A Jaunt Abroad (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN The Night Call (#litres_trial_promo)

PART TWO 1936 (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN Hunting and Shooting (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE 1937–1946 (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY The Volunteer (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-ONE Night (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-TWO The Bailiffs (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-THREE The Crumlin Kremlin (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FOUR The Journey (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FIVE The Camp (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SIX The Man from Spain (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SEVEN In the Hold (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-EIGHT An Encounter (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-NINE The Great Betrayal (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY The Plane (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-ONE The Knock (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-TWO The Grave (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-THREE A Tutor Comes (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-FOUR Make Room (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-FIVE Home (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-SIX The Former People (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-SEVEN The Flag (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-EIGHT A Darkened Room in Oxfordshire (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue 1941 (#ulink_a355d9bf-1e91-5e39-9d84-9db479cce7aa)

A parched twilight began to close in around the unlit prisoner train. For over a week the zeks in Brendan Goold Verschoyle’s wagon had jolted across a landscape they rarely glimpsed, crushed together in putrid darkness. Only those crammed against the wooden slats ever saw the small worms of daylight flicker in through the slight cracks. Little sound penetrated into the wagon either, just the ceaseless rumble of the tracks and very occasionally a more confined echo as they passed at speed through an empty station. Sometimes the long train stopped and prisoners shifted eagerly, yearning for the noise of hammers as guards untangled barbed wire coiled around each carriage and eventually opened the doors. In the stampede to relieve themselves on the dry earth outside, dignity would be forgotten as men and women squatted together under the gaze of the guards and their dogs. But more often these stops occurred for no obvious reason. There would be no sound outside after the wheels came to a rusty halt, no footsteps, no safety catches unleashed, no orders screamed for zeks to get down on their knees and be counted. Instead the train would remain motionless for an indeterminable period during which the zeks inwardly clung to dreams of water and dry bread and fresh air to replace the rancid stink within the sealed wagons.

Eventually when the wheels slowly jolted forward again nobody would speak, even the children no longer able to make the effort to cry. Yet each zek felt a stir of relief amidst their disappointment. Because despite the demand for railway carriages no decision had been made to liquidate them. Fresh instructions must have been issued to change direction and transport them to a different gulag or some patch of barren earth where their first task would be to erect barbed-wire fences around themselves.

Hours later when the train finally stopped for them to receive a small mug of water and several ounces of bread, there would often be another corpse to be lifted off, stiffened in an upright position from having sat cradled between the legs of the chained man behind him.

Half the zeks in this carriage had no idea why they had been arrested. The Polish surname of the man behind Brendan was sufficient to implicate him in a counter-revolutionary Trotskyite conspiracy. The man who died yesterday was among workers sent by Stalin to help build a railway in China, all arrested on their return as members of a Japanese spy ring. Some had endured appalling torture while others knew only cursory interrogation by overworked troikas who took just a few seconds to concoct random treason charges before sentencing them to fifteen years.

Brendan’s position as a foreign political had become perilous in the weeks since a voice on the Tannoy in his last camp had abruptly announced Germany’s treacherous attack on the Soviet Union, with guards and zeks equally stunned that anyone – even Hitler – could dare to defy Stalin. Since then all prisoners with German names had been killed. This train contained zeks who were foreigners or had been contaminated by contact with foreigners and were therefore now classified as enemy soldiers. Still, Brendan had known worse transports. The carriage might lack the luxury of those cattle wagons where zeks could squat over a small toilet hole in the floor, but this heat was better than the cold. Today was bearable. He had managed to fully evacuate his bowels at the last stop, had savoured his mug of water and eaten most of his bread while keeping a small chunk concealed on his person. He was hungry now but would wait until the apex of this starvation before starting to slowly chew the last hunk of black bread. To be able to control when he briefly relieved his hunger gave him a sense of power.

Only two men sat between him and the wall so that when he leaned backwards there was some support. Nobody had yet soiled themselves so that no stream of urine seeped into him and there was no stink of shit. Nobody had died as yet in this wagon today or if they did they had done so without attracting attention. Nobody had tried to steal another zek’s bread, with prisoners lashing out until the thief was dead. Any other theft was acceptable but even here there were taboos one could not break. No woman had been gang-raped, mainly because the carriage consisted of politicals, and true violence only occurred when the common criminals seized control of a wagon, dominating it with their brutality. This wagon was so quiet that for a few seconds Brendan blacked out into sleep and dreamed of Donegal.

The four Goold Verschoyle children were home from boarding school for Easter, reunited with their sister Eva who was considered too delicate to send away. They were bathing at Bruckless Pier in Donegal Bay. At sixteen, Brendan’s eldest brother Art raced hand in hand with seventeen-year-old Eva along the stones to step off the private stone jetty and tumble laughingly into the waves. Nineteen-year-old Maud swam near the shore, while Thomas, aged fourteen, stood balanced in a long-oared punt like a sentry. And Brendan saw himself, nine years of age and sleek as a silvery fish, flitting through the green water, while Mother sat sketching on the rocks and Father looked up from his Walt Whitman book to wave. Eva surfaced and shook out her wet hair before joining Mother to take up her sketchbook as well. Art plunged deeper into the water and surfaced beside Brendan. Reaching out to ruffle his hair, he asked if Brendan liked the kite he had made for him that morning. Brendan nodded his gratitude and plunged his head into the water to glide behind his beloved big brother. Opening his eyes he watched Art power through the waves and longed for the day when he would be that strong. His lungs hurt and he needed to surface for breath while Art’s feet pushed inexhaustibly on.

The unexpected jolt of the train woke him as he crested the waves. Some zeks came out of their torpor and began to talk, wondering if they would be allowed into the air. Others shouted for quiet so they could listen for the click of rifles and the panting of dogs. Brendan discreetly checked that his bread was still there. He longed to still be asleep, yearned for the salty tang of seawater at Bruckless Pier and wanted his family to know that he was still alive. No zek spoke now but he sensed their terror. Because there was no sound of guards’ voices, just the leisurely drone of an aeroplane approaching.

Nettles were in flower on the fringe of the small Mayo wood, with a peculiar beauty that people rarely looked beyond their poisonous leaves to see. Eva watched a Red Admiral alight on the tip of a leaf and the butterfly’s colouring reminded her of the dying glow of the turf last night when she had paused, after blowing out the wick, to gaze back at the fire which moments before had seemed dead in the candlelight. Yet in the dark it had been possible to glimpse the turf embers still faintly beating like two red wings.

Eva was noticing such details now that she had the freedom to see things. Freedom seemed a peculiar word in times of war, but this was how Mayo felt to her soul after escaping from England. The freezing winter was now just a memory. In January her husband had written from barracks to describe the Thames frozen over for the first time in fifty years. Every tiny Mayo lake had been the same, with local children tramping across the ice to pull home whatever firewood they could scavenge. When the Irish Times carried a picture of Finns attempting to hack away the corpses of invading Russian soldiers frozen to the ground, the icy backdrop could have been any white-capped Mayo hillside.

For much of January Eva had been snowed into Glanmire Wood with her two children. Playing and squabbling, drawing pictures on the walls of abandoned rooms and singing hymns at dusk, Francis and Hazel had longed to hear another voice. One night all three heard an unearthly cry from the woods and gathered at the front door to gaze out at the snow, the unnerving wail reminding them of the banshee. Convinced that Freddie’s Territorial regiment had been dispatched to join the desperate battle abroad, at that moment Eva felt sure that her husband was dead. As ever, eleven-year-old Hazel proved the level-headed one.

‘It’s a dog,’ the girl had cried. ‘Trapped out there.’

Hazel had not waited to get properly dressed, but ran into the snow with Francis following and Eva trying to keep up – more concerned for their safety in the snowdrifts than for the dog. It had taken ten minutes to locate the collie’s cries and dig her out. The children carried her back to the house, refusing to change their drenched clothes until they found a blanket to wrap the starved creature in. The dog’s ribs were so exposed that it seemed she would never recover. She survived though and so did they, despite the February storms that shook all of Europe as if God was moved to fury by mankind’s rush to slaughter.

They had safely come through two winters to be happily becalmed in the warmth of this summer’s afternoon with no wind to disturb the trees encircling their crumbling home. The Red Admiral fluttered out onto the uncut lawn where Francis lay bare-chested, intoxicated by the high-pitched warble of two goldcrests in the wood. Returning to Ireland had restored his confidence. He was king of his castle here, venturing in his canoe down the Castlebar river or tramping the bogs where his father loved to shoot, but armed only with binoculars to watch for snipe among the reeds. Eva tried to keep his education going, but he only became excited about Latin when a neighbour loaned him a study of Irish trees. Now on walks through Glanmire Wood he eagerly displayed his knowledge. The hazel, with its coppery-brown bark and dangling yellow catkins, was called Corylus avellana. The birch with its sticky long winter buds and winged nutlets was Betula alba. He even told her Latin names for absent species that he intended to plant one day. Arbutus unedo, called the strawberry tree because its clustered fruit was covered with tiny warts and resembled strawberries. If Francis had his way Eva doubted if he would ever leave this wood again, because here he was Adam in all his innocence, reminding her of her youngest brother, Brendan, on those long childhood afternoons when they used to bathe at Bruckless Pier.

Eva watched the collie rouse herself from the front steps and pad across the lawn to collapse beside Francis. The boy lazily stretched out his hand and the dog rolled over to expose the freckled stomach she wanted rubbed.

Eva had a list of urgent tasks to jot down, but despite having taken pencil and paper outside she was too caught up in this miraculous heat to focus on responsibilities. Hazel emerged from the stables where she had been brushing down her pony and went to fill a bucket with water as the pump handle creaked in rusty protest.

‘I’m going to the kitchen,’ she announced. ‘I’m going to make bubbles.’ But the girl paused to stare past the branches of the sweet chestnut framing the avenue. Hazel had sharp hearing but soon Eva also heard the jingle of a bicycle circumventing the deep ruts on the overgrown path. She could not prevent herself being seized by a familiar fear, a residue from her childhood in the Great War when silence would envelop Dunkineely village whenever the postmaster left his office with a telegram. Was it news of Brendan or her parents? Surely Freddie, with his club foot, would not be sent into battle, no matter how desperate the war effort. But perhaps age and disability meant nothing, with Mussolini conscripting boys at fourteen, barely older than Francis. Eva lowered her pencil and tried to pray for all those she loved whom she knew to be in danger.

Full-length drapes across the window gave the Oxford bedroom an appearance of twilight, though it was only mid-afternoon when Mrs Goold Verschoyle woke. For most of the night she had fretted about her husband’s safety as he patrolled the blacked-out streets as an air raid warden. So far, Oxford had escaped the fate of Coventry and Southampton, but some nights the fires in London were so great that their glow was said to be glimpsed even at this remove. Only after hearing Tim return safely at dawn had she allowed herself to fall asleep. But there was no sign of him having come up to bed. She lay on for a moment, recalling her dream about Donegal. She could still see Mr and Mrs Ffrench crossing their lawn from Bruckless House down to the stone pier with trays of homemade lemonade for the visiting swimmers. Brendan had loved their lemonade, often prolonging his thirst so as to savour the taste. Brendan, her youngest, had been like a fish in her dream.

A constant struggle with arthritis had left Mrs Goold Verschoyle’s face severely lined. Her disability was so acute that holding a pen was torture: still she refused to stop writing to British and Soviet officials. Each line represented physical agony, but she was motivated by a need to quench the greater anguish in her heart. Today she determined not to upset herself by sifting through the replies piled in the bedside drawer – curt responses expressing regret at being unable to supply any information about her missing son. Today she would make herself look well for Tim. Painfully she brushed her hair, still soft and fine like a child’s. Through the open wardrobe door she glimpsed the mothballed dresses she had once worn at parties in Donegal. She put down the hairbrush on the dressing table beside a copy of The Great Outlaw – her favourite book about Christ – and opened a drawer to examine the small bottles of perfume she was carefully nursing there.

Selecting her husband’s favourite, she rose. Tim would be pleased to see that she was not too frail to leave her bed today. He was probably sleeping downstairs so as not to wake her. But when she reached the drawing room he was not lying on the sofa. His body was slumped forward in an armchair, with a book of poems still balanced on his knee. Mrs Goold Verschoyle watched, too scared to move. It would be typical of Tim for his death – like his entire life – to be so understated that the book had not even fallen from his lap.

Show some mercy, Lord, she prayed. Don’t take him away from me also.

The book toppled over, striking the carpet with a dull thud. Mr Goold Verschoyle stirred slightly, looking down at the book and stooped to pick it up. He became aware of her.

‘How is my darling?’ he asked quietly.

Mrs Goold Verschoyle made no reply, but walked over to place her hand on his shoulder.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘I can feel how precious this time is too.’

Tragedy declined to penetrate the Mayo wood today because it wasn’t a telegram boy who emerged beneath the chestnut branches onto the lawn where Eva and her children watched. Instead it was Maureen, their former maid but now their friend and lodger. She freewheeled up to the steps, delighted with her weekly half day off from the shop in Castlebar where she worked. Her wicker basket was full of provisions ordered by Eva, with every item paid for. It was bliss to owe no money and have no fear of creditors.

Glanmire House had undoubtedly gone to seed. Cracked windowpanes had not been replaced, loose tiles let rainwater into disused rooms with walls covered in a seaweed-like vegetation. But the kitchen was dry and warm and the few habitable rooms were adequate for their needs. Just now those needs were simple.

The horror of war was ever present by its absence. This woodland silence seemed artificial, as if punctured by distant cries so high-pitched that only the dog could cock her head to stare off puzzled into the distance.

Ireland was not yet directly consumed by the conflagration, but few doubted an imminent invasion from one side or the other. While the countryside held its breath people learnt to live in limbo. For Protestant neighbours the fact that Freddie had joined the British army was sufficient to reinstate respectability after the debacle of their bankruptcy. With Freddie too engrossed in army life to press her about maintaining appearances, Eva could discreetly go native with the children, talking and thinking as they liked in the privacy of this wood. Without Freddie, Glanmire House reminded her of the freedom of her childhood in Donegal.

Hazel waved to Maureen, then picked up the bucket of water and went to the kitchen. Francis waved and rolled onto his stomach to let the sun warm his back. Maureen laid her bicycle against the steps and strolled over to Eva.

‘That heat’s a terror.’ She flopped down. ‘The chain came off my bike near Turlough and I thought my hands would be destroyed with oil.’

‘Any news from the village?’ Eva asked.

‘Divil the bit, Mrs Fitzgerald. The Stagg boys are off to England for work, though you’d swear half of Mayo had the same idea if you saw the crowds in Castlebar Station and the train already packed from Westport. They’ll be sitting on the roof in Claremorris if it gets that far with the wet turf they’re burning. They say English factory owners are crying out for workers.’

Maureen kicked off her shoes and lay back to let the sun brown her legs. Eva wondered if the girl was hinting at being tempted to go. The young woman reached into her bag to produce a letter.

‘I met Jim the Post and said I’d save him the cycle,’ she said. ‘He looked killed with curiosity wondering what might be in it.’

Both laughed before Maureen picked up her shoes and went to join Hazel in the kitchen. Eva opened Freddie’s letter with trepidation because it was true that his weekly registered one, containing her allowance, had only arrived on Monday. As always his tone was candid, yet circumspect. The mantra that careless talk cost lives was instilled in him, though Eva doubted if his letters were being steamed open by German sympathisers in an Irish sorting office. The Irish preferred to receive news of the tightening Nazi noose by listening to Lord Haw-Haw’s bragging tones on German radio. Even then she suspected that most locals only listened because Haw-Haw was a fellow Connaught man and they took pride to see a local do well for himself in any walk of life.

Typically the first page enquired after the children before Freddie imparted his news. Eva’s fears of him being dispatched to join the fighting were groundless – for now at least. With two million young men called up, the army needed experienced men to provide military training, and Freddie wrote that his time spent shooting on the Mayo bogs might not have been wasted after all. He kept his tone self-deprecating, as if baffled at having to relay the news of being commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Educational Corps. But Eva knew he would have impressed his superiors by being the best shot in his reserve artillery company. Such promotion was a dream realised, especially with his disability. Eva knew that he would show each conscript the care he would have taken with Francis had his son betrayed the slightest interest in guns.

Freddie had knuckled down to army life. The routine suited him. He would be popular once he controlled his drinking – his Irishness being a bonus for showing that he had deliberately chosen to be involved in the war. His tales about shooting on the bogs would be embellished for comic effect. He wrote about missing them but at heart Eva knew that he relished the freedom to succumb to a last drink with new acquaintances and ease himself into each day by waking up alone. Eva knew that he would feel guilty for enjoying this sense of freedom because she experienced the same guilt here in Mayo. Neither said it, but war was providing the camouflage for them to commence separate lives. Her brother Art had been right to proclaim that they should never have married.

In the wooden dormitory hut of the Curragh Internment Camp for subversives, Art Goold rose after polishing his boots. The discipline of camp life suited him. It was the sole advantage gleaned from having attended Marlborough College. Last week yet another IRA boy had been rounded up and interned for the duration of the conflict in Europe – which de Valera and his puppet imperialist government euphemistically termed ‘The Emergency’. Listening to the boy cry when he thought the other internees were asleep, Art had remembered dormitories of boys abducted at an early age to be brainwashed and brutalised into managing an empire.

The difference of course was that in this camp, guarded by the Irish army, every internee was equal. There were no prefects or fags, no casual bullying or ritualised beatings. At Marlborough you were force-fed lies, but here a chance existed for genuine discourse. Not that all IRA men had open minds: some made a hurried sign of the cross when spying him. Art was used to such superstition, but most internees had grown relaxed with him, especially as he knelt alongside them at night while they recited their rosary. They knew that Art did not pray, but he considered it essential to camp morale to show respect for their beliefs. It made them curious about his beliefs too. His description of Moscow streets socialising and how agricultural production was transformed by the visionary genius of Stalin fascinated men who had never previously travelled more than thirty miles from their birthplace. At heart they were kulaks who would need to be prised from their few boggy acres when the time came. But what could one expect when they were terrorised by priests with the spectre of eternal punishment. Besides, having emanated from the Byvshie Liudi, Art could look down on no one. Stalin had coined that term well: the former people – remnants of the despised tsarist class who refused to play their part in the revolution. Soviet re-education camps were full of them, with soft hands learning to handle a shovel and be given a chance to redeem themselves. The triumph of the White Sea Canal, carved from rock with primitive tools and honest sweat, proved how re-education worked. Art had been sent back to Ireland to spread the gospel and, if de Valera insisted in interning him as a communist, then this camp was an ideal environment to do that.

The IRA and the communists were not natural allies but the persuasiveness of his argument was starting to gain converts. Art had previously agreed with the IRA leadership that Ireland stay neutral. However – since Hitler’s attack on Russia – Art had no option but to call on Ireland to join the fight against German fascism now that Comrade Stalin had strategically aligned himself with the imperialists. Blinded by misguided nationalist shibboleths and petty hatred of Britain, the camp leadership had grown scared of his speeches in recent weeks. But it was not about collaboration with Britain, it was about using the Allies as a vehicle to crush fascism before uniting behind Stalin to create a new world order. That was a greater prize than the steeples of Fermanagh.

This was the moment for all revolutionaries to unite and, while the IRA might find it hard to adjust, Art had shown how radical change was possible. It had not been easy. Christ only endured forty nights in the desert, but Art had spent two decades working on the docks, kipping in tenements and police cells. He had been his own judge, serving every day of his sentence with hard labour and was strong and cleansed of his former class now. But the confusing thing was that last night he dreamt about his family bathing off Ffrench’s private pier and had felt no guilt in re-experiencing that life of idle privilege. Instead he had known a sense of belonging, a dangerous wave of love all the more disturbing for emanating from those he was forced to repudiate.

Art left the hut, anxious to be on time for the few internees not intimidated away from his Russian language class. But soon he realised that two men were walking alongside him. He glanced at them as they pinned his arms. They belonged to the primitive Catholic element of Republican. He was strong enough to take them on but as they turned into a space between the huts he saw a deputation awaiting him. Taking a long knife from his pocket the camp IRA commander held it to Art’s throat.

‘You’ve been court-martialled, Goold, and sentenced in absentia.’

‘You can’t court-martial me. I’m not a member of any Republican organisation.’

‘You’re a Protestant crackpot.’

‘I’m an atheist.’

‘Either way you go to hell. You’re just going there sooner than expected. I’ve had enough. We told the governor that unless you were gone by today you’d be found with a hundred knife wounds tomorrow morning. You’re his responsibility now.’

The men pinning back Art’s arms shoved him forward and he started walking. Then for some unknown reason, he remembered his brother Brendan in that dream last night, swimming alongside him, trying to keep up. Art stopped, not through fear but after being overcome by déjà vu and an inescapable guilt. He lifted his head, almost as if willing for retribution to finally come through a bullet or a knife.

Mrs Ffrench crossed the lawn from Bruckless House, and reached the gravel path that led to the small pier. Years ago on a picnic there when the Goold Verschoyle family argued about whether they should call it Bruckless Pier or Mr Ffrench’s Pier, Eva had insisted that it should really be christened Paradise Pier because that was what it was. But with the Goold Verschoyles gone, nobody called it Paradise Pier any more. Indeed no one ever came here, though locals knew that she never objected to people swimming there. But superstition was strong, despite everyone in Bruckless and Dunkineely being kind to her in her grief. Perhaps nothing summed up her husband’s failure more than their affection for him. He had seen himself as a radical orator, a progressive torch of truth amidst their fog of ignorance. But she realised that locals had just considered him a colourful eccentric – not even regarding him as Irish. Local priests had frequently railed against the Red Menace without bothering to mention her husband, despite his years of standing up on the running board of his Rolls-Royce at public meetings to heckle the speakers and beseech people to read the communist pamphlets that she had patiently held out.

Locally their crusade had been considered so laughable that it counted for nothing. The only converts they ever made came from their own class – those marvellous Goold Verschoyle boys. Not that class would count for anything after the revolution, but it still counted for something now. This was evident from the respectful way that people had carried her husband’s body home last month after he collapsed while bicycling to Killybegs to heckle de Valera at a political rally. She had warned him it was too far to cycle but petrol was impossible to obtain. Mrs Ffrench had laid him out in the study, with his maps and books and his tame birds that flew about, soiling everywhere, disturbed by all the visitors. For three days the most unlikely people came to pay their respects, farm labourers who had never previously set foot in the house. Any trouble he had caused with Art Goold Verschoyle was forgotten. But all the neighbourhood could whisper about was his funeral arrangements.

No one attended the interment but she had sensed eyes watching from across the inlet as four workmen laid her husband’s body in this sheltered corner of the garden beside the pier. In Donegal only unbaptised babies and suicides were buried on unconsecrated ground. But this had been Mrs Ffrench’s wish and where she would lie when her time came. There had been no prayers or speeches; just L’ Internationale played on the wind-up gramophone. Mrs Ffrench reached the headstone and knelt to lay wild flowers. The local stonemason had gone to his priest for advice before chiselling the stark inscription her husband chose as his epitaph: Thomas Roderick Ffrench: The Immortality of the Dead Exists Only in the Minds of the Living.

The silence outside the prison train was broken by indistinct sounds: the barking of released dogs, guards shouting in panic, a scramble of boots across the ground.

‘The bastards,’ an old zek muttered behind Brendan. ‘They’re more concerned with saving the dogs than saving us. Come back, you cowards, unlock these doors.’

The entire wagon was on its feet now, banging at the roof and wooden walls. Bursts of machine-gun fire came from above, interspersed with cries.

‘Aim well, Germans,’ a woman said. ‘Kill every guard.’

‘That’s who they want,’ a young man added. ‘I mean, why would the Germans want to destroy us?’

‘They don’t,’ replied the old zek. ‘We count for nothing. They want to destroy the carriages, this rolling stock.’

Noise of frantic hammering came from inside every wagon. Brendan heard the crush of timber and knew that one set of prisoners had broken free. Their shouts turned to screams amid a burst of gunfire, but he could not tell if the bullets came from the plane or if the guards might have set up their machine guns in the undergrowth. Two men beside him hammered at the roof, being lifted up by other prisoners. They broke away a wooden slat, yielding a dazzling glimpse of blue sky. Everyone was screaming now. But Brendan was utterly still, mesmerised by the blueness above him. It was the blue of an Irish summer and crossing that patch of light was a small aircraft, departing or wheeling around for another assault. It resembled a child’s plaything, a sparkling gleam in the bright air that made him catch his breath as it turned in a slow loop. Others saw it too and began to scream louder. But Brendan said nothing because he had become a boy again, standing on Bruckless Pier to draw in the bright kite that his eldest brother had made for him.

Eva looked up from her husband’s letter as Hazel waltzed out from the kitchen onto the lawn in her bare feet. The girl stirred a mixture in the jug she carried, then tossed back her hair to blow the first bubble skyward, laughing as it rose and burst. Francis briefly watched, then lay back with the dog beside him.

Eva laid down Freddie’s letter and, feeling a sliver of guilt at her idleness, purposefully picked up her pencil to start making the list of tasks planned for this afternoon. But Hazel’s laugh made her glance up at the extraordinary way the child twisted her supple body to keep the bubbles aloft. The girl was totally immersed in this game, enjoying her triumph whenever a bubble stayed intact, laughing at the silent plop of its extinction, then starting anew with a fresh bubble stream. Nothing else existed for Hazel at this moment: no war, no bombers circling Europe’s skies, no threat of invasion or nerve gas, no future complicated by adult decisions. Just these weightless globes to be savoured for the brief totality of their existence.

Eva stared down at the jotting pad, the list of tasks banished from her thoughts. It was years since she last held a pencil for any reason except to scribble down lists. Her childhood instinct to draw – dormant for so long – had unconsciously taken over. She discovered a swirling sketch of her daughter already half finished. Eva examined it with a quickening of the heart. She could draw again if she didn’t think about it. Let the pen do the thinking. A second image shaped itself on the page. Of Hazel stationary this time, back arched and head held back to blow a bubble upward. Eva could see her own reflection within the girl, as if she was the same age, experiencing the same joy. The second sketch was barely finished before her fingers commenced a third. If the girl looked over, the magic would be ruined. Hazel would demand to see what Eva was doing, minutely examining each sketch. But these drawings felt as light as bubbles. At the slightest pressure her ability would burst asunder. It was like a sixth sense returning to her fingers, with the tension of adulthood banished.

Francis spied Maureen’s bicycle beside the front steps. He mounted it and freewheeled deftly across the lawn. Two quarrelling birds chased each other among the trees. There was so much that Eva could add to her sketch: their crumbling house, cattle in the fields below, the crooked stable door. But there was no need to include these because Eva merely wanted to draw happiness. As Hazel spun in giddy circles she seemed like an axis, a fulcrum, a whirlpool of happiness, drawing the whole world into her on invisible threads.

The dog barked, chasing the weaving bicycle. Maureen came from the kitchen to say that tea was ready. But nobody moved as if nobody could hear. Hazel scooped into the jar to unleash a final stream of bubbles. They soared above her, rainbow-coloured in the light. This was how her family had been in Donegal, Eva realised, diving into the waters at Bruckless Pier, beautiful, impractical, living in the moment with no awareness of how short-lived that paradise would be. Hazel danced beneath the last bubble, throwing her head so far back that it seemed impossible she would not fall. Borne by her breath, the bubble rose so high that Eva had trouble following it. Maureen stopped calling and even Francis halted the bicycle to watch. The bubble balanced in midair and Hazel balanced on the grass, equally poised and beautiful until, without warning, it burst and there was nothing left. Hazel toppled backwards, rolled over to gaze at her mother and laughed.

PART ONE 1915–1935 (#ulink_86377c92-8aac-5ceb-83ff-31f04a647863)

ONE The Picnic (#ulink_6d1ceda9-9887-588b-9d62-5bd7503e4676)

August 1915

Eva thought it was glorious to wake up with this sense of expectation. The entire day would be spent outoors, with her family chattering away on the back of Mr Ffrench’s aeroplane cart as Eva dangled her legs over the swaying side and held down her wide-brimmed hat with one hand in the breeze. Surely no other bliss to equal this.

Her older sister Maud was asleep in the other bed in the room. Dust particles glistened in the early sunlight, creeping through a slat in the wooden shutters, the thin beam making the white washbowl beside the water jug even whiter.

It was barely six o’clock but thirteen-year-old Eva could not stay in bed a moment longer. Nobody else was yet awake in Dunkineely. Soon the endless clank of the village pump would commence, but until then Eva had paradise to herself. If she rose quietly she could go walking and be home again before the Goold Verschoyle household rose to prepare for today’s picnic.

Dressing on tiptoes so as not to wake Maud, Eva slipped downstairs. An old white cat beside the kitchen range lifted his head to regard Eva with a secretive look as she lifted the latch and escaped into the garden. The clarity of light enraptured her, with spider webs sketched by dew. Eva followed a trail of fox pawmarks along the curving path leading to the deserted main street, then took the lane that meandered down to the rocky Bunlacky shore. The sea breeze coming off St John’s Point swept away her breath, filling Eva with a desire to shout in praise. She closed her eyes and formal hymns took flight in her mind like a flock of startled crows, with new words like white birds swooping down to replace them. The prayers that meant most were the ones which came unbidden at such moments:

‘O Lord whom I cannot hope to understand or see, maker of song thrush and skylark and linnet. Do with my life what you will. Bring me whatever love or torment will unleash my heart. Just let me be the person I could become if my soul was stretched to its limits.’

Eva opened her eyes, half-expecting white birds to populate the empty sky. Instead a few bushes bowed to the wind’s majesty.

As son of a Church of Ireland bishop, Father took his task seriously of instructing the boys in religion but Mother claimed that secretly he only went to church to sing. It was Mother’s responsibility to instruct the girls. Yet even without Mother’s Rosicrucian beliefs and indifference to organised religion, Eva knew that she would have outgrown their local church in Killaghtee, where sermons were more concerned with elocution than any love of Christ. She needed a ceremony which encompassed her joy at being alive. But if Eva did not belong with her family in the reserved top pew in Killaghtee church, where did she belong? Neither in the Roman Catholic chapel which Cook and Nurse attended nor with the Methodists in their meeting hall next door to her home. Right now this lane felt like a true church, filled with the hymn of the wind. Freedom existed in this blasphemous thought, a closeness to God that might have heralded the sin of vanity had it also not made her feel tiny and lost. Eva closed her eyes and slowly started to spin around, feeling as if she were at the axis of a torrent of colour. Behind her eyelids the earth split into every shade of green and brown that God ever created. The sky was streaked in indigo and azure, sapphire and turquoise. Prisms of colour mesmerised her like phrases in the psalms: jade and olive and beryl, rust and vermilion. At any moment she might take off and whirl through the air like a chestnut sepal. Her breath came faster, her head dizzy.

‘Can you see your child, Lord, dancing her way back to you?’

A sound broke through her reverie, a suppressed laugh. Eva opened her eyes but the earth declined to stop spinning. A young barefoot girl grasped her hand with a firm grip, steadying her. The girl looked alarmed.

‘I’m sent for the cows, miss,’ she said. ‘Are you okay?’

‘Yes.’ The world still swayed dangerously but Eva let go her hand, able to stand unaided.

‘Was it a fit? My sister has fits. She’s epil…’ The girl struggled with the word. ‘Epileptic. They took her to the madhouse in Donegal Town. Are you mad too?’

‘No. I’m just happy.’

The girl mused on the word suspiciously.

‘Your father defended my Uncle Shamie in court for fighting a peeler, miss. They say you’re a fierce dreamer, and your father is for the birds. Why don’t you go to boarding school like your sister?’

‘Mother says I am not strong enough.’

‘They say your mother is a right dreamer too, miss.’

‘What’s your name?’

Deciding that she had already revealed too much to one of the gentry, the girl veered past Eva and moved on, viciously whipping the heads off nettles with a hazel switch. Eva felt embarrassed at being seen.

Where the lane bent to the left the sea came into view. A small sailing ship was firmly anchored in the bay, never changing position despite the buffeting it received from the waves. It was time to go home but Eva could not stop watching the boat. More than anything she wished to be like it, firmly anchored despite the wild seas of emotion she constantly found herself in.

A queue was forming at the village pump by the time Eva returned up the main street. People greeted her respectfully and she talked to everyone. Possibly because she had never gone away to school for long, the whole village had adopted her.

Eva’s miserable few months in boarding school last year had convinced Mother that she was not strong enough for sports or other girls. But sometimes Eva wondered if she was kept at home to afford Mother company during the winter when Mother was affected by illnesses that Dr O’Donnell seemed unable to pinpoint. The front door of the Manor House was open and her five-year-old brother, Brendan, ran out half-dressed to chase the ducks splashing in pools along the deeply rutted street. Eva swept him up in her arms and handed him back to Nurse. The clang of the pump followed her as she walked around by the side of the house. Visitors sometimes asked how the family tolerated this constant clank, but Eva only really noticed the pump when it stopped. For her it represented the creaking heart of Dunkineely.

Her family would be up, chattering away over breakfast, but Eva’s first responsibility was to feed her rabbit in the hutch near the tennis court. Crickets communicated with each other along the grassy bank in an indecipherable bush code as Eva cradled the rabbit to her breast, savouring the special shade of pink within the white of his ears. Sitting on the grass beside the rabbit as he ate, she spied Father through the drawing-room window. His few briefs as a barrister were mainly the unpaid defence of locals in trouble. His real passion was music and Father had left the breakfast table early to work. A black cat – whom he christened ‘Guaranteed to Purr in Any Position’ – sat motionless on his piano as he composed. The cat loved Father, not with a dog’s adoring servitude but as an equal with whom she condescended to share her space. She would sit for hours when he played – her head cocked like a discerning, slightly quizzical, music critic.

All the house cats belonged to Father. Mother’s pleasure arose from holding any baby in her arms. Eva was the only baby she ever rejected, just for a brief moment after Eva was born. Take her away, she had ordered Nurse because – having already borne one daughter – she was convinced that she had been carrying that all-important son and heir. Mother herself had told Eva this story and though Eva never sensed any trace of rejection within Mother’s unequivocal love since then, it still caused unease. Returning the rabbit to the hutch, Eva plucked some daisies from the grass bank and held them to her nostrils. The scent always conjured her earliest memory of sitting on this slope at toddling age, picking a bunch of daisies to breathe in their smell that swamped her with happiness. In her memory, Nurse sat knitting nearby, her white apron hiding a plump, inviting lap. Eva could remember longing to be on Nurse’s lap and suddenly it had felt like she was already there, as if Nurse’s essence – her warm skin and laughing breath – was reaching Eva through the ecstasy of inhaling the fragrance of daisies. Even now she could still recall racing towards Nurse’s arms, holding out the bunch of daisies to be savoured.

‘Eva, quit dreaming and come and have some breakfast! The Ffrenches are calling for us at eight o’clock.’

Maud’s voice had an exasperated big sister tone as she summoned Eva from the doorway. Eva waved and went to join her family in the breakfast room. In Father’s absence, Art sat in the top chair. Sixteen months younger than Eva, he was the heir whom Mother had longed for, being groomed already to take over the Goold Verschoyle lineage. Thomas sat beside him, a year younger and two inches smaller, focusing on eating his egg with the exact concentration that he brought to every task. Being the middle brother made him weigh the value of everything. Brendan was too small to care about such matters. As the youngest he took it as his right to be spoiled by everyone. Maud was organising the hamper with the cook, having baked the cakes herself last night. The servants looked to fifteen-year-old Maud for instructions, finding Mother frequently too unwell to oversee the running of the house. But this was one of Mother’s good weeks and, spurred by the presence of her Cousin George, she would accompany them on today’s picnic.

Everyone at the table talked about their plans for the day. All were good swimmers, though Art was by far the strongest – being nearly as fast as Oliver Hawkins who was seventeen. The Hawkins family from Herefordshire had spent all this summer at Bruckless House, two miles away. Last year a young couple, the Ffrenches, bought this isolated mansion, built by two local brothers on the proceeds of selling guns to Napoleon and pickled herring to Wellington’s army. Mrs Hawkins was related to Mr Ffrench who after being commissioned into the Royal Navy had been away since January. But Mr Ffrench had returned home two weeks ago, claiming that he had insisted on his naval shore leave coinciding with Eva’s end-of-summer birthday party.

Eva had laughed along with everyone else when he said this, but secretly she believed him. This final week of summer was always the most exciting, culminating in Chinese lanterns being hung in the garden for her birthday party, with charades and fancy dress costumes and singers gathering around Father at the piano. After Eva’s birthday the farewells would start at the train station, with the Hawkins family returning to England, Art, Thomas and Maud going away to school and Mr Ffrench rejoining his frigate currently moored in Killybegs Harbour. But Eva refused to let this thought sour her mood as the maid ran in to announce that Mr Ffrench’s cart had arrived and, within seconds, the breakfast room was full of laughing voices.

Mother entered the room with Cousin George to greet the new arrivals. Cousin George was a wise chameleon, secretly in tune with Mother when discussing the occult and yet indistinguishable from any other Church of Ireland curate when a guest preacher in the pulpit at Killaghtee church before their neighbours. His sermons were the only ones that Eva still enjoyed, although the Ffrenches never attended church to hear them – being of a religious persuasion, the Baha’is – that not even Mother had heard of. No locals minded the Ffrenches’ eccentricity because nobody understood it. Grandpappy, now on his annual summer visit, declared that no such religion existed except among a handful of demented Arabs driven from Iran, and the Ffrenches would forget such nonsense once they began to procreate like decent Christians. But since Father invited them along to a picnic last autumn, the Ffrenches had become part of the family, opening up their house and shoreline garden to the Goold Verschoyle children.

The ceaseless chatter made Eva fear that today’s picnic might never start. But Maud coaxed everyone out onto the street where people started to lift picnic baskets up onto Mr Ffrench’s open-backed float, christened the Aeroplane Cart. Maud sat at the back with the Hawkins twins, who were the same age as her, dangling their legs and bending their heads together to gossip beneath wide-brimmed hats. Somehow twelve-year-old Beatrice Hawkins managed to perch between Art and Eva, unable to address either of them. Until ten days ago Eva and Beatrice had been the closest chums, left to fend for themselves when Maud and the twins disappeared to whisper about grown-up secrets. They had searched for nests without disturbing the eggs, taken turns to push Brendan on his scooter along the street with anxious ducks scattering or had gone walking along the shore with Art minding them. But recently Eva could not explain the friction between them, as if Beatrice was jealous of Eva having a brother so wonderful as Art and wanted to push in and play at being his sister also.

Beatrice’s brother, Oliver, held the reins as the cart left Dunkineely behind. Eva saw Maud watching him furtively and knew that she had fallen in love. When they reached Bruckless village, Oliver gave Thomas the reins and went to sit among the grown-ups. Cousin George had Brendan on his knee, teaching him to shout the responses to a music hall rhyme:

‘Who goes there?’

‘A grenadier.’

‘What do you want?’

‘A pint of beer.’

‘Where’s your money?’

‘In my pocket.’

‘Where’s your pocket?’

‘I forgot it.’

The adults laughed, demanding an encore as the horse jangled along the Killybegs road. The Donegal hills rose to the right, arrayed in purple, with the sea to their left and beyond it Ben Bulbin screening the distant Mayo mountains. Sunlight lit the gorse, with foxgloves peeping from hedgerows. Father was maintaining that idle moments like this brought us closer to the truths of the universe, while Mr Hawkins countered that the Irish were sufficiently lazy without being given a philosophy to excuse their idleness.

Eva was relieved to hear the adults not discussing the war because today was too perfect for outside intrusions. The morning passed in a babble of voices that died away as they neared the sea, leaving just the jangle of the harness and the noise of hooves on the dusty road.

The view from the rocks beside the beach was so striking that Mother had to sketch it at once. Eva climbed up with a sketchpad to keep her company. Both looked out to sea, drawing quietly. Behind them, rugs were spread out on the sand and Maud arranged plates from the hamper as the Hawkins twins poured homemade lemonade. Father sat talking to Art while Beatrice Hawkins lay beside Art in the very spot where Eva wanted to lie when the sketching was finished. Brendan kept pestering Art by presenting seashells to the big brother he worshipped and, although Beatrice Hawkins was normally too quiet to merit notice, Eva saw that she also kept bothering Art by shyly brushing sand with her bare foot over his.

They had forgotten to bring drinking water, but Mr Ffrench climbed up towards the caves with a copper kettle to collect water from the streamlet trickling down over the glistening rocks. Father went to assist him and suddenly Beatrice Hawkins found the courage to lob a handful of sand over Art’s hair. She shrieked as Art rolled over to trap her in a wrestling hold, gathering up sand that he playfully threatened to make her swallow. Then just as quickly Art rolled off the girl and picked up Father’s book, pretending to ignore her.

‘Oh,’ Mother said quietly, distracting Eva. Her pencil went still as she stared across the waves. Thirty seconds passed before she looked at Eva with an air of casual curiosity. ‘How strange. I’ve just seen something interesting.’

‘What?’ Eva asked.

‘I don’t know,’ Mother replied matter-of-factly. ‘A stone statue rose slowly from the sea to block the horizon.’

‘What did it do?’

‘Why nothing, dear, obviously. It was just a statue. It rose as far as its navel, then sank slowly without a sound.’ Mother resumed sketching, her seascape bereft of any figure. ‘It looked rather like Neptune,’ she added as an afterthought. ‘Or Manannán Mac Lir, the Celtic God of the Sea, the way that AE draws him in visions. Not that AE is a good draughtsman, of course. How is your sketch coming on?’

‘Fine,’ Eva replied, accustomed to Mother’s psychic visions. They sketched away with nothing further to say. The stone figure would be their secret. It had no place in the boisterous picnic taking shape on the sands where Mr Ffrench clambered down to applause, jumping the last few feet without spilling a drop from the kettle. Eva was anxious to help Art deal with the pest which Beatrice Hawkins had become for him and, once the kettle was boiled over a fire of twigs, Mother was also happy to join the main picnic.

The meal was gloriously protracted, with interruptions as shapes in the changing clouds diverted people’s attention or when they paused to hear each other’s favourite quotations. Father, for once, chose not Whitman but Longfellow to share with the gathering:

‘And evermore beside him on his way

The unseen Christ shall move,

That he may lean upon his arm and say

“Dost thou, dear Lord, approve?”’

Cousin George was a master diplomat, encompassing the Ffrench’s strange beliefs by reciting:

‘So many gods, so many creeds;

So many paths that wind and wind,

While just the art of being kind

Is all the sad world needs.’

Eva saw how this gesture impressed Mr Hawkins, who knew that Grandpappy – who avoided today’s picnic by rising early to go into Killybegs – had little time for divergent beliefs, including those of his own daughter-in-law. Mr Hawkins’s good mood was tempered however by Maud’s hot-headed contribution to the quotations:

‘Ireland was Ireland when England was a pup

And Ireland will still be Ireland when England is done up.’

Home Rule was anathema to Mr Hawkins and Eva sensed how the picnic could be soured by politics. Nobody disputed the absolute rightness of the war in Europe, but people held differing opinions as to what should happen in its aftermath. Father believed strongly that what was good enough for Belgium should be good enough for Ireland and so, in fighting to free that small nation, the Irish boys were fighting for their own right to self-determination. Mr Ffrench appeared less sure. Since his rapid promotion within the Royal Navy he seemed to lean more towards Mr Hawkins who called Father’s attitude treasonous for a Briton. Father laughed off this comment, saying that the Verschoyles lacked one drop of English blood. They were Dutch nobles who came over with William of Orange and later married into ancient Irish clans whose ancestry he had personally traced back to Niall of the Nine Hostages.

Leaving politics to the grown-ups, Eva joined the other children bathing in the sea, with Maud delighted when Oliver Hawkins joined them. Oliver said little about the war and Eva suspected he felt differently from his father. As Art and Oliver raced each other out to the rocks, Eva lay in the waves and watched Maud secretly cheer on Oliver against her brother and Beatrice Hawkins secretly do the same for Art. At last the time came to pack away the hampers and load the cart, with Beatrice again interloping between Eva and Art. People said less on the return journey, content to relax in the evening sun.

When they reached Killybegs Harbour a coach was parked along the quay where a travelling showman was demonstrating a wireless set. Mr Hawkins gave them all money to sit among a row of people with earphones over their heads, listening to a crackle of faint voices breaking in from outside. Maud seemed indifferent amid the general gasps of wonder, but these bodiless voices disturbed Eva, breaking into her closeted world with other lives and languages. She couldn’t wait to dismount from the coach but the showman had to shake Art and Thomas before her brothers removed their headphones. Art seemed distracted as they returned to the cart, questioning Mr Hawkins about every aspect of radio.

Waiting for them there was Grandpappy, a tall white-bearded old man dressed in knickerbockers appropriate to his ecclesiastical station. Two soldiers arranging their posters more prominently outside a recruiting booth respectfully nodded to Mr Ffrench, instinctively recognising his military bearing. Young women leaving the carpet weaving factory studied a poster outside the Royal Bank of Ireland advertising sailings to New York for three pounds and sixteen shillings. Grandpappy wanted to know who would ride in his pony and trap. Eva scrambled up into the trap, with Art behind her. People joked about them being inseparable during the holidays and she hated to think of him returning to Marlborough College. Eva fretted when Mrs Hawkins asked Grandpappy to wait, complaining that her old bones couldn’t take the bumpy aeroplane cart, but although Beatrice longed to join them she was too shy to follow. The old man took Art on his knee, allowing him the reins.

Eva might be Grandpappy’s favourite but in time Art would be his heir after Father, with the Manor House perpetually indentured by law to be passed in trust to the eldest son of the eldest son.

On a bend with fields falling away towards the sea, a flock of sheep halted them, crowding through a crude gateway from the lands of Mr Henderson, a local farmer. Frightened of the pony, they shied into the ditch. A sandy-haired boy of Art’s age darted after the sheep, fiercely waving a stick. Welts formed a mottled pattern down his thighs. His bare feet were brown with dust and his face had a pinched hungry look.

‘Gee-up!’ Grandpappy encouraged Art to take control and urge the pony forward. The boy lowered his stick to stare at Art. For a moment Eva saw them observe one another, each boy intensely sizing up the other. Then Grandpappy flicked the whip and the pony jogged past, scattering the sheep.

‘Why does he have no shoes?’ Art asked, as if their staring contest had only now brought home this everyday disparity.

‘What would he need shoes for?’ Grandpappy laughed. ‘His feet are as hard as the hob.’

‘He wasn’t born with hard feet.’

‘He was born poor. He looks a strong lad who’ll do well for himself if he works hard. He won’t be left standing at the Strabane hiring fair when his time comes. Tyrone farmers know the measure of everything from horseflesh to boys. He’ll find a good master.’

‘Better a farm than the Glasgow mills,’ Mrs Hawkins said.

She and Pappy fell silent, but something troubled Art. The reins went loose, the pony slackening as if sensing a lessening of authority. Eva looked behind to spy the aeroplane cart encountering the sheep.

‘What if he doesn’t want to stand at a fair like an animal?’ Art asked.

‘That’s how life is ordained.’ Mrs Hawkins broke into a verse of All Things Bright and Beautiful:

‘The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

He made them high or lowly

And ordered their estate.’

‘Stop the cart,’ Art said with sudden fierceness. ‘He’s my size. I want to give him these shoes. It’s stupid that I own five pairs and he has none.’

Pappy laughed, wrapping Art in a bear-hug till the boy ceased to struggle.

‘You’re a good boy, but you must harden yourself or be fooled by every beggar and three-card-trick-man on the street. He’ll have shoes when he earns them. It’s how the world works. You’ll have men under you one day. Firm but fair is how to win respect, not by throwing away your possessions.’

Distant laughter rose behind them as Father joked with the boy who managed to harry the sheep into an enclosure. Brendan was asleep, being rocked on Mother’s lap. Eva envied Art his place on Grandpappy’s knee, like she envied him the status she would have enjoyed if born a boy. Art was her special friend, but since Beatrice Hawkins started talking too much or going silent in his company, Eva had been disturbed by a recurring dream. In it Art was bound in a dungeon with Eva advancing on him, holding the terrible steel contraption she once saw a farm boy carry. When Eva had asked what it was the boy snapped it shut and smirked, ‘To castrate young bulls, miss, and put a halt to their jollies.’ Eva did not know what castration meant until Maud, who knew everything, said it was ‘to cut off the slip of a thing men make such a fuss about’. This dream mortified her because she could never hurt Art. Shivering, Eva reached guiltily across to ruffle Art’s hair. He loosened Grandpappy’s bear-grip enough to smile back, although she saw how he was still upset.

Dunkineely village was deserted when the pony cantered past MacShane’s public house. Mr MacShane emerged and said that a shoal of mackerel had swum into the inlet at the Bunlacky jetty. Grandpappy whipped the pony so as not to miss the excitement. The lane was crammed, with people lining the rocks beside the tiny jetty as the trap came to a halt. Youths had only to cast fishing rods in the waves to instantly haul out more silvery bodies. Women waded into the water using turf creels to capture the fish battering senselessly against each other. Barefoot children outdid one another in savage bravado as they killed the gasping fish with stones. Grandpappy laughed with approval, urging Art to dismount. Eva watched her brother join in the orgy of slaughter, blood and fragments of gut staining his shirt. The air was festive, pierced by warlike shouts of Take that, you Hun. Finally the aeroplane cart arrived and Beatrice Hawkins watched Art spatter a mackerel’s brains with as much admiration as if he were harpooning a whale. Father noticed Eva sitting very still beside Mrs Hawkins. ‘Run along home,’ he said quietly, ‘and tell Cook we’re having mackerel for supper. I’m sure the Hawkinses can be prevailed upon to stay. Aye, and tell her we’ll be having mackerel for breakfast, lunch and dinner all next week too.’

Eva had seen Art fish with Father and even helped them to kill sea trout out on their small boat. Sea fishing had felt noble but now she couldn’t bear to look back in case she saw Art hold up the dead mackerel amid the slaughter for Beatrice to admire. Eva ran home to give Cook the message, then went to her room. Her perfect day in paradise felt ruined. Pressing her face against the cool sheet on her bed, Eva closed her eyes but kept visualising a floundering shoal of mackerel. They refused to die, wriggling furiously with their battered heads. Fish eyes stared up, having got separated from scaly bodies. They became the eyes of dead soldiers in the war that Eva hated people discussing. She had always loved the taste of mackerel but knew that she could never bear to bite into their oily flesh again.

Maud entered the room, kicked off her shoes and threw her hat on her bed. She flopped down. ‘Come on, Eva,’ she said. ‘The Hawkins girls are staying and Mother says we can play musical bumps. Surely there’s some way to persuade Oliver to join in. My word, it has been such a day.’ She stopped and looked across. ‘What’s wrong, Eva?’

‘Nothing.’

‘You look like you’ve been crying.’

‘Haven’t.’

‘Cook says we’ll have a feast.’

‘What is she making?’

‘Fish, you goose. Get changed. It will be such fun. Father says we can use the gramophone.’ She sat up to observe Eva closely. ‘Shall I call Mother?’

‘I’m all right.’

‘I think I will.’

Maud went out, leaving the door open. Rising, Eva poured water into the white basin to wipe the smudge of tears from her eyes, then walked towards the window overlooking the street. The carpet ended a few feet from the window, the floorboards cool on her soles. The windowpane soothed her forehead. She felt so small suddenly in that long room, imagining the lonely winter months of solitary lessons ahead. Sketching for hours by the Bunlacky shore, reading to Brendan or sitting with Mother while she read books of sermons sent from London. Each Tuesday Mother would engage in planchette with her psychic friend, Mrs O’Hare – both women calmly attempting to decipher spirit messages, with the table moving beneath their outspread hands. But despite such loneliness it was better than the horrors of the bustling school dormitories to which the others would return.

A sound betrayed Mother’s presence.

‘What’s wrong, Eva?’

‘Nothing.’

‘That’s not true. Normally you would be the first downstairs on such an evening. We don’t have secrets, you and I.’

‘It’s too terrible.’

‘Nothing is terrible if you share it.’

Eva meant to describe the mackerel, but the streaks of blood on Art’s shirt on the jetty became confused with his tortured body in her dream. ‘I keep having nightmares where I hurt Art terribly. I must be the worst sister in the world.’

Mother stood behind Eva who was unable to turn and face her. The woman did not place a hand on her shoulder but Eva sensed the comfort of her presence.

‘You’re a Virgo,’ Mother said calmly. ‘All Virgos have a touch of that. I’m to blame for telling you I wanted a boy before you were born. But your dream might not be about Art. It could be the memory of unfinished business from another life or a vision of something to come. And even if it is about Art we’re not to blame for our dreams or for being complex. You want life to be black and white, but we all have two sides. Just because we each hide one side from strangers doesn’t mean we should hide it from ourselves. Everyone is jealous. Look at me, crippled with arthritis. Some days I’m jealous of you dancing around, unaware of the wonder of being able to move without pain. You’re allowed to feel jealous, Eva. You’re allowed to be anything that’s part of you once it doesn’t take over. Now is your secret so terrible?’

‘Don’t tell Father.’

Mother laughed. ‘Us women need a few secrets, because God knows men keep enough. I’m jealous of your hair too. Let me comb it, then away downstairs. You need to be out more with other children. Maybe I’ve been wrong to keep you away from school. But you’ve always been so delicate that I was worried you might not cope.’

‘I don’t want to go to school,’ Eva said. ‘I love life here.’

‘You’re lonely in winter,’ Mother replied. ‘Still, it’s too lovely an evening for worries.’

She brushed Eva’s hair in comforting strokes, tilting her head slightly and smiling at Eva until her daughter smiled back. Eva looked around to spy Art in the doorway, concerned at her absence.

‘The fun is starting,’ he said, ‘but it’s not the same until you come down.’

Taking Eva’s hand, he drew her from the room. On the stairs they passed Nurse carrying Brendan who had woken up. The small boy put out his hand to Art, delighted when his big brother squeezed it. Eva looked back at Mother who smiled as she watched them descend towards the excited voices in the drawing room. Grandpappy had gone to rest but the other men were emerging from a pre-dinner drink in Father’s study. Eva noticed that Oliver had been allowed to join them.

‘Your AE is a menace with his anti-recruitment talk,’ Mr Hawkins was complaining. ‘It was bad enough him siding with Larkin’s union during the Dublin lockout two years ago. He would do better sticking to painting fairies than meddling in politics.’

‘AE is entitled to his opinion,’ Father replied. ‘Not that the King or Kaiser will pay him any more heed than the Dublin employers did. They were determined to break the workers and had the Roman church behind them.’

‘Your church too,’ Mr Hawkins pointed out. ‘Larkin is a communist. What support could AE gather for such a blackguard?’

Remembering Mother’s reference to AE, Eva imagined an army of stone figures rising from Dublin Bay, summoned by the bearded mystic whom Mother regarded as a friend.

‘What is a communist, Father?’ Art asked, alerting the men to their presence on the stairs.

‘A thief,’ Mr Hawkins retorted, ‘who would murder you in your bed and divide your possessions among every passing peasant.’

‘Somebody who thinks differently from us,’ Father interjected quietly.

‘True,’ Mr Ffrench agreed. ‘Perhaps Christ was a communist.’

‘Really, Ffrench!’ Mr Hawkins was aghast.

‘I don’t think he was,’ Father said. ‘Christ asked us to live selfless lives for love of our fellow man and the promise of our reward in the next life. The communist offers no such reward. His world will not work because we are the flawed children of Adam. The communist may proffer an earth without God, but he cannot create an earth without sin. Our chief sin is greed and that is the worm which would devour the communist’s clockwork world.’

‘Larkin would devour your world too,’ Mr Hawkins argued. ‘Hand in hand with the Germans, he would murder every Irishman of property, with your cousin acting as his scullery maid.’

‘Countess Markievicz knows her own mind,’ Father replied mildly.

‘She’s a traitor to her class,’ Mr Hawkins declared, ‘consorting with dockers and slum revolutionaries? Is this the mob you would put in power if we gave you Home Rule?’

‘Mr Larkin wishes to murder nobody,’ Father argued. ‘He simply wants children not to sleep nine in a bed.’

‘And I agree with him,’ Mr Ffrench interjected. ‘Is it so wrong to want children to have bread?’

‘And shoes?’ Art asked.

‘Yes, shoes too,’ Mr Ffrench agreed.

Mr Hawkins bristled. ‘You’re too free with the talk you allow in this house.’ He pointed into the study. ‘I never though to hear such comments allowed by someone with that portrait over his desk.’

Eva glanced in at the dark portrait of Martin Luther whose stern eyes followed her whenever she entered Father’s study.

‘Any man who pinned a thesis of ninety-five points on a church door invited discourse,’ Father replied, unflappably. ‘Come, Hawkins, let’s not quarrel.’ He smiled at Art and Eva. ‘You children run along before you forfeit your forfeits.’

Maud fretted in the drawing room, impatient at their dallying and upset because Oliver had been commissioned into the ranks of the men. Beatrice Hawkins was anxiously awaiting their presence too. The carpet was rolled back and six cushions placed on the waxed floor. Gas jets hissed as Nurse came down from Brendan’s room, having been coerced into playing records on the gramophone. Dance music began as the children waltzed around the cushions, never straying far lest they lose the game. Nurse lifted the needle and the music stopped. Maud and Thomas were first to sit down, each laughingly bagging a cushion. The three Hawkins girls fell in unison so that Art and Eva were left battling for the last cushion. But Eva spied Art’s almost indecipherable feign as he slipped, ensuring that she got to the cushion first.

‘Forfeit!’ the others shouted gleefully.

‘What is it?’ Art asked.

Maud glanced towards the door, ensuring that the adults were beyond earshot. She sneaked a look at Nurse. ‘You must kiss the person you like best,’ Maud commanded – her favourite forfeit, the one she longed to play on Oliver. Eva blushed as Art glanced at her, certain of being chosen, yet dreading the public spectacle. Then, to her astonishment, he strode towards Beatrice Hawkins to surprise the girl with a kiss. Beatrice stared at Art as if nobody else was present and Eva suddenly sensed that she was losing her brother. Then the others laughed as Beatrice blushed in embarrassed delight. Art turned to Nurse, smiling.

‘More music,’ he commanded. ‘Let’s dance. Let’s all dance.’

They danced on in the August twilight. Art was now being so attentive to Eva that she made herself forget the way he had kissed Beatrice. It grew so dark outside that their reflections became visible in the windowpanes. There was something comforting about seeing her world there, exactly as it should be, with bodies whirling about. Still she was glad when Cook knocked on the door to announce that supper was ready because it hastened the time when the Hawkins family would be leaving and she would have Art to herself.

Mother sensed that something was wrong as soon as the cooked mackerel was placed before Eva. Gently she suggested that Cook might find something else for her. People at the table were too busy trying to be heard to pay much attention. Father had yielded his normal seat to Grandpappy who seemed to agree with Mr Hawkins on most issues concerning politics. Oliver Hawkins spoke little but Eva saw how he often glanced at Maud. Art finished eating and asked to be excused. Eva waited a few moments then followed him out to the old coach house where he and Thomas had constructed a den. He was busy at a table with bits of tube and wires.

‘Are you feeling okay?’ she asked. ‘Would you like to do something?’

Art looked up. ‘I will later. I just want to see if I can make a wireless.’

Brendan appeared in the doorway, having sneaked out of bed in hopes of being with his oldest brother. He was fascinated by anything Art did and pleaded to be allowed to help with the complex arrangements of wire. Eva left them there, knowing that soon Thomas would join them to question each decision with his impeccable logic, becoming even more determined than Art to construct this contraption. She knew that she would not see Art for the rest of the night, with the boys locked away, fixated by crackling siren voices as they attempted to construct their wireless set.

Returning to the house she found that the adults and the girls had moved into the drawing room. The front door was open and several local people had wandered in, attracted by the sound of the piano. Eva liked how people always spilled into the Manor House. There was old Dr O’Donnell from Killaghtee House, waylaid on his way home from a sick call, and two soldiers home on leave who clapped loudly when Maud finished her party piece. Eva took a window seat in the crowded room as Father sang the tone poem for violin and orchestra in his still unperformed Tir na n-Og symphony:

‘Far, far away, across the sea

There lies an island divinely fair

Where spirits blest forever dwell

And breathe its radiant enchanted air.’

Everyone applauded, taking pride in this local composition. A hush came as Mr Ffrench took Father’s place at the piano. This striking young officer was still a novelty in Dunkineely and few people had previously heard him sing. Mr Ffrench announced that while travelling with the Royal Navy he had encountered strange men, but none as unusual as the hero of Mr Percy French’s song, Abdullah Bulbul Amir. He commenced the opening bars, then stopped to stare at Eva.

‘What are you sketching, Eva?’

‘You.’

Mr Ffrench beckoned Eva forward. She felt embarrassed, unused to anyone except Mother paying attention to her sketching. Heads craned forward to await the officer’s opinion. He considered her drawing in a silence that seemed to last for ever.

‘Well, Eva, do you know what this officer thinks?’

‘No, sir.’

‘That you will be a true artist when you grow up. Let no one steer you from that path. Can I keep this?’

Eva nodded, too overcome to speak, and returned to her seat, watching as Mr Ffrench began to play, with no sheet music in front of him, but an unfinished sketch balanced on the holder instead. She longed to get back the drawing, to sketch in Mother and Father and all the other faces in the crowded drawing room as Mr Ffrench smiled at her, then began to sing in a wondrous voice. People demanded an encore and it was midnight before all the party pieces were performed, with the visitors departing into the night, calling their farewells as the cart moved off along the dark street.

Eva and Maud had hot milk and bread in the kitchen before being sent to bed. Eva was glad to go, but Maud felt that she should be allowed to stay up with the adults who would talk late into the night. The wooden shutters blocked out any moonlight. Both sisters lay quietly, awaiting Mother’s final visit. Eva gazed up at the picture of a young girl kneeling beside a bed in prayer. She could not remember a time when this picture had not hung on her wall. She listened for Mother’s shoes on the creaky step near the bend of the stairs. The door was ajar, gaslight filtering in from the corridor. Mother ascended the stairs and Eva heard her soft voice in Art’s room before she pushed their door fully open. Framed in the light she looked beautiful in her dark grey hostess gown. She sat for a time on each bed. There was no hugging. She never took them on her knee for cuddles. Instead they sensed the aura of her love as she quietly asked each daughter if they had enjoyed their day. Mother’s fingers played with Eva’s hair while they talked, braiding imaginary plaits as a faint fragrance filled the air. It emanated from the hand lotion Mother always rubbed into her palms after gardening. She wore no makeup or perfume, just this scent as her fingers stroked Eva’s hair for a final few seconds before she said goodnight and the door closed.