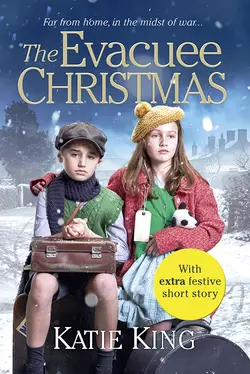

The Evacuee Christmas

Katie King

A heart-warming story of friendship and family during the first Christmas of World War Two.Autumn 1939 and London prepares to evacuate its young. In No 5 Jubilee Street, Bermondsey, ten-year-old Connie is determined to show her parents that she’s a brave girl and can look after her twin brother, Jessie. She won’t cry, not while anyone’s watching.In the crisp Yorkshire Dales, Connie and Jessie are billeted to a rambling vicarage. Kindly but chaotic, Reverend Braithwaite is determined to keep his London charges on the straight and narrow, but the twins soon find adventures of their own. As autumn turns to winter, Connie’s dearest wish is that war will end and they will be home for Christmas. But this Christmas Eve there will be an unexpected arrival…

KATIE KING is a new voice to the saga market. She lives in Kent, and has worked in publishing. She has a keen interest in twentieth-century history and this novel was inspired by a period spent living in south-east London.

Copyright (#ulink_81789314-0eb5-501e-8ca8-d7721b971c3e)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2017

Copyright © Katie King 2017

Katie King asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008257552

Version: 2018-04-17

Contents

Cover (#u99ff3c97-9cc2-561b-be15-5ea9a286560b)

About the Author (#u1908544f-a7f5-5b04-a3a8-0d3625a5fe01)

Title Page (#u1f60c6ce-b29c-5ca6-ab93-07196df46952)

Copyright (#ulink_49a28fbe-cb11-5017-9a81-fcb78090a514)

Chapter One (#ulink_19024ccb-3f34-5867-9bfa-67d4c1ace7f9)

Chapter Two (#ulink_7033f0a8-e7e2-5e3d-8d60-8f43bd077117)

Chapter Three (#ulink_c4120330-1582-5743-a3ea-7b18276cca60)

Chapter Four (#ulink_98987900-072b-59f9-b9f1-16e45de8ef79)

Chapter Five (#ulink_966a2b6a-cf68-5eb5-a17a-c33c9f99e70d)

Chapter Six (#ulink_2b09b8be-4a5f-5b02-9de9-b3dfcba07d6a)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_32aaf1f6-b483-5992-b385-ae759506dbce)

Chapter Eight (#ulink_dfc80d81-57d8-54db-9ce3-2aa083c38deb)

Chapter Nine (#ulink_3eccc585-b6bf-5e28-9716-94a0d8560c25)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive Short Story - Oranges (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_84eee687-ce77-5e5c-abba-40069bd170f0)

The shadows were starting to lengthen as twins Connie and Jessie made their way back home.

They felt quite grown up these days as a week earlier it had been their tenth birthday, and their mother Barbara had iced a cake and there’d been a raucous tea party at home for family and their close friends, with party games and paper hats. The party had ended in the parlour with Barbara bashing out songs on the old piano and everyone having a good old sing-song.

What a lot of fun it had been, even though by bedtime Connie felt queasy from eating too much cake, and Jessie had a sore throat the following morning from yelling out the words to ‘The Lambeth Walk’ with far too much vigour.

On the twins’ iced Victoria sponge Barbara had carefully piped Connie’s name in cerise icing with loopy lettering and delicately traced small yellow and baby-pink flowers above it.

Then Barbara had thoroughly washed out her metal icing gun and got to work writing Jessie’s name below his sister’s on the lower half of the cake.

This time Barbara chose to work in boxy dark blue capitals, with a sailboat on some choppy turquoise and deep-blue waves carefully worked in contrasting-coloured icing as the decoration below his name, Jessie being very sensitive about his name and the all-too-common assumption, for people who hadn’t met him but only knew him by the name ‘Jessie’, that he was a girl.

If she cared to think about it, which she tried not to, Barbara heartily regretted that Ted had talked her into giving their only son as his Christian name the Ross family name of Jessie which, as tradition would have it, was passed down to the firstborn male in each new generation of Rosses.

It wasn’t even spelt Jesse, as it usually was if naming a boy, because – Ross family tradition again – Jessie was on the earlier birth certificates of those other Jessies and in the family Bible that lay on the sideboard in the parlour at Ted’s elder brother’s house, and so Jessie was how it had to be for all the future Ross generations to come.

Ted had told Barbara what an honour it was to be called Jessie, and Barbara, still weak from the exertions of the birth, had allowed herself to be talked into believing her husband.

She must have still looked a little dubious, though, as then Ted pointed out that his own elder brother Jessie was a gruff-looking giant with huge arms and legs, and nobody had ever dared tease him about his name. It was going to be just the same for their newborn son, Ted promised.

Big Jessie (as Ted’s brother had become known since the birth of his nephew) was in charge of the maintenance of several riverboats on the River Thames, Ted working alongside him, and Big Jessie, with his massive bulk, could single-handedly fill virtually all of the kitchen hearth in his and his wife Val’s modest terraced house that backed on to the Bermondsey street where Ted and Barbara raised their children in their own, almost identical red-brick house.

Barbara could see why nobody in their right mind would mess with Big Jessie, even though those who knew him soon discovered that his bruiser looks belied his gentle nature as he was always mild of manner and slow to anger, with a surprisingly soft voice.

Sadly, it had proved to be a whole different story for young Jessie, who had turned out exactly as Barbara had suspected he would all those years ago when she lovingly gazed down at her newborn twins, with the hale and hearty Connie (named after Barbara’s mother Constance) dwarfing her more delicate-framed brother as they lay length to length with their toes almost touching and their heads away from each other in the beautifully crafted wooden crib Ted had made for the babies to sleep in.

These days, Barbara could hardly bear to see how cruelly it all played out on the grubby streets on which the Ross family lived. To say it fair broke Barbara’s heart was no exaggeration.

While Connie was tall, tomboyish and could easily pass for twelve, and very possibly older, Jessie was smaller and more introverted, often looking a lot younger than he was.

Barbara hated the way Jessie would shrink away from the bigger south-east London lads when they tussled him to the ground in their rough-house games. All the boys had their faces rubbed in the dirt by the other lads at one time or another – Barbara knew and readily accepted that that was part and parcel of a child’s life in the tangle of narrow and dingy streets they knew so well – but very few people had to endure quite the punishing that Jessie did with such depressing regularity.

Connie would confront the vindictive lads on her brother’s behalf, her chin stuck out defiantly as she dared them to take her on instead. If the boys didn’t immediately back away from Jessie, she blasted in their direction an impressive slew of swear words that she’d learnt by dint of hanging around on the docks when she took Ted his lunch in the school holidays. (It was universally agreed amongst all the local boys that when Connie was in a strop, it was wisest to do what she wanted, or else it was simply asking for trouble.)

Meanwhile, as Connie berated all and sundry, Jessie would freeze with a cowed expression on his face, and look as if he wished he were anywhere else but there. Needless to say, it was with a ferocious regularity that he found himself at the mercy of these bigger, stronger rowdies.

Usually this duffing-up happened out of sight of any grown-ups and, ideally, Connie. But the times Barbara spied what was going on all she wanted to do was to run over and take Jessie in her arms to comfort him and promise him it would be all right, and then keep him close to her as she led him back inside their home at number five Jubilee Street. However, she knew that if she even once gave into this impulse, then kind and placid Jessie would never live it down, and he would remain the butt of everyone’s poor behaviour for the rest of his childhood.

Barbara loved Connie, of course, as what mother wouldn’t be proud of such a lively, proud, strong-minded daughter, with her distinctive and lustrous tawny hair, clear blue eyes and strawberry-coloured lips, and her constant stream of chatter? (Connie was well known in the Ross family for being rarely, if ever, caught short of something to say.)

Nevertheless, it was Jessie who seemed connected to the essence of Barbara’s inner being, right to the very centre of her. If Barbara felt tired or anxious, it wouldn’t be long before Jessie was at her side, shyly smiling up to comfort his mother with his warm, endearingly lopsided grin.

Barbara never really worried about Connie, who seemed pretty much to have been born with a slightly defiant jib to her chin, as if she already knew how to look after herself or how to get the best from just about any situation. But right from the start Jessie had been much slower to thrive and to walk, although he’d always been good with his sums and with reading, and he was very quick to pick up card games and puzzles.

If Barbara had to describe the twins, she would say that Connie was smart as a whip, but that Jessie was the real thinker of the family, with a curious mind underneath which still waters almost certainly ran very deep.

Unfortunately in Bermondsey during that dog-end of summer in 1939, the characteristics the other local children rated in one another were all to do with strength and cunning and stamina.

For the boys, being able to run faster than the girls when playing kiss chase was A Very Good Thing.

Jessie had never beaten any of the boys at running, and most of the girls could hare about faster than him too.

It was no surprise therefore, thought Barbara, that Jessie had these days to be more or less pushed out of the front door to go and play with the other children, while Connie would race to be the first of the gang outside and then she’d be amongst the last to return home in the evening.

Although only born five minutes apart, they were chalk and cheese, with Connie by far and away the best of any of the children at kiss chase, whether it be the hunting down of a likely target or the hurtling away from anyone brave enough to risk her wrath. Connie was also brilliant at two-ball, skipping, knock down ginger and hopscotch, and in fact just about any playground game anyone could suggest they play.

Jessie was better than Connie in one area – he excelled at conkers, him and Connie getting theirs from a special tree in Burgess Park that they had sworn each other to secrecy over and sealed with a blood pact, with the glossy brown conkers then being seasoned over a whole winter and spring above the kitchen range. Sadly, quite often Jessie would have to yield to bigger children who would demand with menace that his conkers be simply handed over to them, with or without the benefit of any sham game.

Ted never tried to stop Barbara being especially kind to Jessie within the privacy of their own home, provided the rest of the world had been firmly shut outside. But if – and this didn’t happen very often, as Barbara already knew what would be said – she wanted to talk to her husband about Jessie and his woes, and how difficult it was for him to make proper friends, Ted would reply that he felt differently about their son than she.

‘Barbara, love, it’s doing ’im no favours if yer try to fight ’is battles for ’im. I was little at ’is age, an’ yer jus’ look a’ me now’ – Ted was well over six foot with tightly corded muscles on his arms and torso, and Barbara never tired of running her hands over his well-sculpted body when they were tucked up in their bed at night with the curtains drawn tight and the twins asleep – ‘an’ our Jessie’ll be fine if we jus’ ’elp ’im deal with the bullies. Connie’s got the right idea, and in time ’e’ll learn from ’er too. An’ there’ll be a time when our Jessie’ll come into his own, jus’ yer see if I’m not proved correct, love.’

Barbara really hoped that her husband was right. But she doubted it was going to happen any time soon. And until then she knew that inevitably sweet and open-hearted Jessie would be enduring a pretty torrid time of it.

Still, on this pleasant evening in the first week of September, as a played-out and shamefully grubby Connie and Jessie headed back towards their slightly battered blue front door in Jubilee Street, the only thing a stranger might note about them to suggest they were twins was the way their long socks had bunched in similar concertinas above their ankles, and that they had very similar grey smudges on their knees from where they had been kneeling in the dust of the yard in front of where the local dairy stabled the horses that would pull the milk carts with their daily deliveries to streets around Bermondsey and Peckham.

As the twins walked side by side, their shoulders occasionally bumping and two sets of jacks making clinking sounds as they jumbled against each other in the pockets of Jessie’s grey twill shorts, the children agreed that their tea felt as if it had been a very long time ago. Although the bread and beef dripping yummily sprinkled with salt and pepper that they’d snaffled down before going out to play had been lovely, and despite Barbara having seemed quiet and snappy which was very unlike her, by now they were starving again and so they were hoping that they’d be allowed to have seconds when they got in.

They’d only been playing jacks this evening, but Connie had organised a knock-out tournament, and there’d been seven teams of four so it had turned into quite an epic battle. Connie had been the adjudicator and Jessie the scorekeeper, keeping his tally with a pencil-end scrounged from the dairy foreman who’d also then given Jessie a piece of paper to log the teams as Jessie had thanked him so nicely for the inch-long stub of pencil.

The reason the jacks tournament had turned into a hotly contested knock-out affair was that Connie had managed to cadge a bag of end-of-day broken biscuits from a kindly warehouseman at the Peek Freans biscuit factory over on Clements Road – the warehouseman being a regular at The Jolly Shoreman and therefore on nodding acquaintance with Ted and Big Jessie – as a prize for the winning team. These Connie had saved in their brown paper bag so that Jessie could present them to the winning four, who turned out to be the self-named Thames Tinkers German Bashers.

As the game of jacks had gone on, every time Jessie had peeked over at the paper bag containing the biscuits that his sister had squirrelled close to her side (once, he fancied that he even caught a whiff of the enticing sugary aroma), his mouth had watered even though he knew the warehouseman had only given them to Connie as they were going a bit stale and had missed the day’s run of broken biscuits being delivered to local shops so that thrifty, headscarved housewives would later be able to buy them at a knock-down rate.

Jessie knew that Connie had wanted him to present the biscuits to the winning team as a way of subtly ingratiating himself with the jacks players, without her having to say anything in support of her brother. She was a wonderful sister to have on one’s side, Jessie knew, and he would have felt even more lost and put upon if he didn’t have her in his corner.

Still, it had only been a couple of days since he had begged Connie to keep quiet on his behalf from now on, following an exceptionally unpleasant few minutes in the boys’ lavatories at school when he had been taunted mercilessly by Larry, one of the biggest pupils in his class, who’d called Jessie a scaredy-cat and then some much worse names for letting his sister speak out for him.

Larry had then started to push Jessie about a bit, although Jessie had quite literally been saved by the bell. It had rung to signal the end of morning playtime and so with a final, well-aimed shove, Larry had screwed his face into a silent snarl to show his reluctance to stop his torment just at that moment, and at last he let Jessie go.

Jessie was left panting softly as he watched an indignant Larry leave, his dull-blond cowlick sticking up just as crossly as Larry was stomping away.

To comfort himself Jessie had remembered for a moment the time his father had spoken to him quietly but with a tremendous sense of purpose, looking deep into Jessie’s eyes and speaking to him with the earnest tone that suggested he could almost be a grown-up. ‘Son, you’re a great lad, and I really mean it. Yer mam an’ Connie know that too, and all three o’ us can’t be wrong, now, can we? And so all you’s got to do now is believe it yerself, and those lads’ll then quit their blatherin’. An’ I promise you – I absolutely promise you – that’ll be all it takes.’

Jessie had peered back at his father with a serious expression. He wanted to believe him, really he did. But it was very difficult and he couldn’t ever seem able to work out quite what he should do or say to make things better.

Back at number five Jubilee Street following the jacks tournament, the twins wolfed down their second tea, egg-in-a-cup with buttered bread this time, and then Barbara told them to have a strip wash to deal with their filthy knees and grime-embedded knuckles.

Although she made sure their ablutions were up to scratch, Barbara was nowhere near as bright and breezy as she usually was.

Even Connie, not as a matter of course massively observant of what her parents were up to, noticed that their mother seemed preoccupied and not as chatty as usual, and so more than once the twins caught the other’s eye and shrugged or nodded almost imperceptibly at one another.

An hour later Connie’s deep breathing from her bed on the other side of the small bedroom the twins shared let Jessie know that his sister had fallen asleep, and Jessie tried to allow his tense muscles to relax enough so that he could rest too, but the scary and dark feeling that was currently softly snarling deep down beneath his ribcage wouldn’t quite be quelled.

He had this feeling a lot of the time, and sometimes it was so bad that he wouldn’t be able to eat his breakfast or his dinner.

However, this particular bedtime Jessie wasn’t quite sure why he felt so strongly like this, as actually he’d had a good day, with none of the lads cornering him or seeming to notice him much (which was fine with Jessie), and the game of jacks ended up being quite fun as he’d been able to make the odd pun that had made everyone laugh when he had come to read out the team names.

As he tried willing himself to sleep – counting sheep never having worked for him – Jessie could hear Ted and Barbara talking downstairs in low voices, and they sounded unusually serious even though Jessie could only hear the hum of their conversation rather than what they were actually saying.

Try as he might, Jessie couldn’t pick out any mention of his own name, and so he guessed that for once his parents weren’t talking about him and how useless he had turned out to be at standing up for himself. He supposed that this was all to the good, and after what seemed like an age he was able to let go of his usual worries so that at long last he could drift off.

Chapter Two (#ulink_3b9d0f52-8990-56f6-a8f2-9484d4c65992)

When the children had been smaller, Ted and Big Jessie had met a charismatic firebrand of a left-wing rabble-rouser called David, and eventually he had talked the brothers into going to several political meetings in the East End aimed at convincing the audience of the need for working-class men to band together to form a socialist uprising. A lot of the talk had been of fascists, and the political situation in Spain and Germany.

It wasn’t long before Ted and Big Jessie had been persuaded to go with members of the group to protest against Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts’ march through Cable Street in Whitechapel, although the brothers had retreated when the mood turned nasty and rocks were pelted about and there were running battles between the left- and right-wing supporters and the police.

Ted, naturally an easy-going sort, hadn’t gone to another meeting of the socialists, and within a few months David had left to go to Spain to fight on the side of the Republicans.

Still, his tolerant nature didn’t mean that Ted would always nod along down at The Jolly Shoreman whenever (and this had been happening quite often in recent months) a patron seven sheets to wind would suggest that any fascist supporters should be strung up high. He didn’t like what fascists believed in but, deep down, Ted believed they were people too, and who really had the right to insist how other people thought?

But in recent weeks Ted had had to think more seriously about what he believed in, and how far he might be prepared to go to protect his beliefs, and his family.

As he was a docker, working alongside Big Jessie on the riverboats that spent a lot of their time moving cargo locally between the various docks and warehouses on either side of the Thames, Ted had witnessed first-hand that the government had been preparing for war for a while.

He’d seen an obvious stockpiling of munitions and other things a country going to war might need, such as medical supplies and various sorts of tinned or non-perishable foodstuffs that were now stacked waiting in warehouses. There’d also been a steady increase in new or reconditioned ships that were arriving at the docks and leaving soon afterwards with a variety of cargo.

And recently Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had taken to the BBC radio to announce hostilities against Germany had been declared following their attack on Poland. His words had been followed within minutes by air-raid sirens sounding across London, causing an involuntary bolt of panic to shoot through ordinary Londoners. It was a false alarm but a timely suggestion of what was to come.

Understandably, the dark mood of desperation and foreboding as to what might be going to happen was hard to shake off, and during the evening of the day of Chamberlain’s broadcast Ted and Barbara had knelt on the floor and clasped hands as they prayed together.

Scandalously, in these days when most people counted themselves as Church of England believers (or, as London was increasingly cosmopolitan, possibly of Jewish or Roman Catholic faiths), neither Ted nor Barbara, despite marrying in church and having had the twins christened when they were only a few months old, were regular churchgoers, and they had never done anything like this in their lives before.

But these were desperate times, and desperate measures were called for.

As they clambered up from their knees feeling as if the sound of the air-raid siren was still ringing in their ears, they took the decision not, just yet, to be wholly honest if either Connie or Jessie asked them a direct question about why all the grown-ups around them were looking so worried. They wouldn’t yet disturb the children with talk of war and what that might mean.

The next day, when Connie mentioned the air-raid siren, Barbara explained away the sound of it by saying she wasn’t absolutely certain but she thought it was almost definitely a dummy run for practising how to warn other boats to be careful if a large cargo ship ran aground on the tidal banks of the Thames, to which Connie nodded as if that was indeed very likely the case. Jessie didn’t look so easily convinced but Barbara distracted him quickly by saying she wanted his help with a difficult crossword clue she’d not been able to fathom.

Although naturally both Ted and Barbara were very honest people, they could remember the Great War all too clearly, even though they had only been children when that war had been declared in 1914, and they could still recall vividly the terrible toll that had exacted on everyone, both those who had gone to fight and those who had remained at home.

This meant they felt that even though it would only be a matter of days, or maybe mere hours, before the twins had to be made aware of what was going on, the longer the innocence of childhood could be preserved for Connie and Jessie, as far as their parents were concerned, the kinder this would be.

Once Ted and Barbara started to speak with the children about Britain being at war, they knew there would be no going back.

Now that time was here.

Just before the children had arrived home from school, things had come to a head.

For schoolteacher Miss Pinkly had called at number five to deliver a typewritten note to Barbara and Ted from the headmaster at St Mark’s Primary School.

When Barbara saw Susanne Pinkly at her door, immediately she felt an overpowering sense of despair.

Without the young woman having to say a word, Barbara knew precisely what was about to happen.

By the time that Ted came in after the twins had gone to bed – Barbara not bringing up the topic of evacuation with Connie and Jessie beforehand as she wanted the children to be told only when Ted was present – Barbara was almost beside herself, having worked herself up into a real state.

Ted had just left a group of dockers carousing at The Jolly Shoreman. Ted wasn’t much of a drinker, but he had gone over with Big Jessie for their usual two pints of best, which was a Thursday night ritual at ‘the Jolly’ for the brothers and their fellow dockers as the end of their hard-working week drew near.

Now that Ted saw Barbara standing lost and forlorn, looking whey-faced and somehow strangely pinched around the mouth, he felt sorry he hadn’t headed home straight after he’d moored the last boat. No beer was worth more than being with his wife in a time of crisis, and to look at Barbara’s tight shoulders, a crisis there was.

Barbara was standing in front of the kitchen sink slowly wrapping and unwrapping a damp tea towel around her left fist as she stared unseeing out of the window.

The debris of a half-prepared meal for her husband was strewn around the kitchen table, and it was the very first time in their married lives that Ted could ever remember Barbara not having cleared the table from the children’s tea and then cooking him the proverbial meat and two veg that would be waiting ready for her to dish up the moment he got home. Normally Barbara would shuffle whatever she’d prepared onto a plate for him as he soaped and dried his hands, so that exactly as he came to sit down at the kitchen table she’d be placing his plate before him in a routine that had become well choreographed over the years since they had married.

‘Barbara, love, whatever is the matter?’ Ted said as he swiftly crossed the kitchen to stand by his wife. He tried to sound strong and calm, and very much as if he were the reliable backbone of the family, the sort of man that Barbara and the twins could depend on, no matter what.

Barbara’s voice dissolved in pieces as she turned to look at her husband with quickly brimming eyes, and she croaked, ‘Ted, read this,’ as she waved in his direction the piece of paper that Miss Pinkly had left.

At least, that was what Ted thought she had said to him but Barbara’s voice had been so faint and croaky that he wasn’t completely sure.

Ted stared at it for a while before he was able to take in all that it said.

Dear Parent(s),

Please have your child(s) luggage ready Monday morning, fully labelled. If you live more than 15 minutes from the school, (s)he must bring his case with him/her on Monday morning.

EQUIPMENT (apart from clothes worn)

• Washing things – soap, towel

• Older clothes – trousers/skirt or dress

• Gym vest, shorts/skirt and plimsolls

• 6 stamped postcards

• Socks or stockings

• Card games

• Gas mask

• School hymn book

• Shirts/blouse

• Pyjamas, nightdress or nightshirt

• Pullover/cardigan

• Strong walking shoes

• Story or reading book

• Blanket

ALL TO BE PROPERLY MARKED

FOOD (for 1 or 2 days)

• ¼lb cooked meat

• 2 hard-boiled eggs

• ¼lb biscuits (wholemeal)

• Butter (in container)

• Knife, fork, spoon

• ¼lb chocolate

• ¼lb raisins

• 12 prunes

• Apples, oranges

• Mug (unbreakable)

Yours sincerely,

DAVID W. JONES

Headmaster, St Mark’s Primary School, Bermondsey

The whole of Connie and Jessie’s school was to be evacuated, and this looked set to happen in only four days’ time.

Her voice stronger, Barbara added glumly, ‘I see they’ve forgotten to put toothbrush on the list.’

After a pause, she said, ‘Susanne Pinkly told me that not even the headmaster knows where they will all be going yet, although it looks as if the school will be kept together as much as possible. Some of the teachers are going – those with no relatives anyway – but Mr Jones isn’t, apparently, as St Mark’s will have to share a school and it’s unlikely they’ll want two headmasters, and Miss Pinkly’s not going to go with them either as her mother is in hospital with some sort of hernia and so Susanne needs to look after the family bakery in her mother’s absence now that her brother Reece has already been given his papers.

‘But the dratted woman kept saying again and again that all the parents are strongly advised to evacuate their children, and I couldn’t think of anything to say back to her. I know she’s probably right, but I don’t want to be parted from our Connie and Jessie. Susanne Pinkly had with her a bundle of posters she’s to put up in the windows of the local shops saying MOTHERS – SEND THEM OUT OF LONDON, and she waved them at me, and so I had to take a couple to give to Mrs Truelove for her to put up in the window and on the shop door. While the talk in the shop a couple of days ago made me realise that a mass evacuation was likely, now that it’s here it feels bad, and I don’t like it at all.’

Ted drew Barbara close to him, and with his mouth close to her ear said gently, ‘I think we ’ave to let ’em go. The talk in the Jolly was that it’s not goin’ to be a picnic ’ere, and we ’ave to remember that we’re right where those Germans are likely to want to bomb because the docks will be – as our Big Jessie says – “strategic”.’

They were quiet for a few moments while they thought about the implications of ‘strategic’.

‘I know,’ said Barbara eventually in a very small voice. ‘You’re right.’

Ted grasped her to him more tightly.

They listened to the tick-tocking of the old wooden kitchen clock on the mantelpiece for an age, each lost in their own thoughts.

And then Ted said resolutely, ‘We’ll tell our Connie and Jessie at breakfast in the mornin’. They need to hear it from us an’ not from their classmates, an’ so we’ll need to get ’em up a bit earlier. We must look on the bright side – to let them go will keep them safe, and with a bit of luck it’ll all be over by Christmas and we can ’ave them ’ome with us again. ’Ome in Jubilee Street, right beside us, where they belong.’

Barbara hugged Ted back and then pulled the top half of her body away a little so that she could look at her husband’s dear and familiar face. ‘There is one good thing, which is that as you work on the river, you’re not going to have to go away and leave me, although I daresay they’ll move you to working on the tugs seeing how much you know about the tides.’

There was another pause, and then Barbara leant against his chest once more, adding in a voice so faint that it was little more than the merest of murmurs, ‘I’m scared, Ted, I’m really scared.’

‘We all are, Barbara love, an’ anyone who says they ain’t is a damned liar,’ Ted said with conviction, as he drew her more tightly against him.

Chapter Three (#ulink_fc93a5f4-b12e-5d8c-b848-98e969f8fd93)

Three streets away Barbara’s elder sister Peggy was having an equally dispiriting evening. Her husband Bill, a bus driver, had received his call-up papers earlier in the week, and he had to leave first thing in the morning.

All Bill knew so far was that Susanne Pinkly’s brother Reece was going the same morning as he, and that after Bill and his fellow recruits gathered at the local church hall, all the conscripts would be taken to Victoria station and from there they would be allocated to various training camps in other parts of Britain, after which at some point he and the rest of them would leave Blighty for who knew where.

Bill was packed and ready to go, but he was worried about Peggy, who was four months pregnant and was having a pretty bad time of it, and so Bill wanted her to hotfoot it out of London as soon as she was able as part of the evacuation programme, as pregnant women as well as mothers with babies and/or toddlers were amongst the adults that the government advised to leave London.

‘It’s daft, you riskin’ it ’ere in the interestin’ condition you’re in,’ he told her.

‘Interesting condition’ was how they had taken to describing Peggy’s pregnancy as they thought it quaintly old-fashioned and therefore a phrase full of charm.

‘I want to go and fight for King and Country knowin’ my little lad or lassie is out of ’arm’s way, an’ ’ow can I do that if I know you’re still stuck ’ere in Bermondsey? Those docks will be a prime target for the Germans, you mark my words, Peg,’ Bill added.

Deep down Peggy knew there was sound sense to Bill’s argument. They had been childhood sweethearts and had married at twenty, and then had had to wait ten agonisingly long years before Barbara pointed out to her big sister that Peggy wasn’t getting plump as she had just been complaining about, and that the fact that her waistband on her favourite skirt – a slender twenty-four inches – would no longer do up as easily as it once had was very likely because Peggy had in fact fallen pregnant.

Peggy was dumbfounded, and then thrilled.

A fortnight later Bill actually passed out, bumping his head quite badly, when Peggy showed him a chitty from the doctor that confirmed what they had spent so many years longing for, and which they – or Peggy at least – had completely given up hope of ever happening.

Until the doctor had confirmed all was well to Peggy, she hadn’t dared say anything to Bill, knowing how many times he’d been cut to the quick when a missing or late period, or Peggy having a slight bulge in her normally flat tummy, hadn’t gone on to lead to a baby. Perhaps now they could get their marriage back to the happy place it had once been.

Understandably, their relationship had struggled as the childless years had mounted, and as everyone around them had seemed to be able to have a baby every year with depressing ease. Peggy had often had to bite back bitter tears in public when she’d heard a woman complaining about being pregnant again.

She would have given anything to be pregnant just once, while Bill had sought solace in the bookies or the pub, and occasionally over the last year or two, Barbara had begun to wonder if he hadn’t taken comfort in the arms of another, not that she ever dared raise the issue.

Being barren was bad enough, Peggy felt, but to be barren and alone, which could well be an inevitable consequence if Bill had found himself seeking a refuge from their worries elsewhere, was more than she felt she could cope with.

The doctor’s confirmation that, as he put it, ‘a happy event is in the pipeline’, had felt to Peggy very much like the strong glue the couple needed to stick things back together again between them, and Bill had seemed to agree, not that he had ever said as much.

But this sense of optimism hadn’t prevented Peggy’s pregnancy being full of problems and worries, as she had continued to menstruate as if she weren’t pregnant, she’d had terrible sickness from around virtually the very moment that Barbara had made the quip about the skirt waistband and more or less constantly since, until perhaps only a week or so previously.

This endless nausea had led to her losing a lot of weight, and so one day when Peggy was looking particularly blue, Barbara had echoed the doctor with, ‘That baby is going to take everything he or she needs from you – they are clever like that. And so although the very last thing you might feel like doing is eating or drinking, that is precisely what you must do, as you really do need to keep your strength up.’

Peggy was inclined to agree with her sister about the baby being quite selfish in getting what it needed. Right from the start her stomach had become very rounded – much more so, she was convinced, than other mothers-to-be she met who were roughly at the same stage as she – while her breasts were tender, with darkened and extended nipples that couldn’t bear being touched.

While the baby seemed quite happy tucked away inside Peggy, the rapid weight loss from his or her mother’s arms and legs and face had made her look very weary and drawn, while her extended belly and puffy ankles and fingers suggested that Peggy might be a lot less happy health-wise than her baby.

In fact, she had recently had to take off her wedding ring as her fingers had become too bloated for wearing it to be comfortable any longer. Now she wore the ring on a filigree gold chain around her neck that Bill had got from a jeweller’s in Aldgate, Peggy saying that this was an even more special way for her to wear the ring as it held the precious wedding ring as close to her heart as it could possibly be.

The posters going up around London suggested it was going to be downright dangerous to stay in the city. Peggy knew that Ted would be needed on the river and this meant that Barbara would stay by his side, no matter what.

‘Peggy, I can’t stay ’ere as I’ve got my papers,’ Bill said as he sat on the other side of the kitchen table to her, ‘an’ I think you know that’s true for you too, as it’s likely that round ’ere it’ll all be bombed to smithereens an’ back.’

Peggy’s breath juddered. Bill was right, but his blunt words rattled her, in part as she immediately thought of what Barbara and Ted might be going to have to face.

Bill’s words were simple, but these were such big things he was saying. Of course she knew that she had a treasured new life growing inside – made all the more precious by the long time that she and Bill had had to wait for such a wondrous thing to occur – and so when push came to shove she would do what was best for their much-longed-for baby. And now that Bill had voiced his concerns about how dangerous London was very likely to be, she didn’t want him to worry about her and the baby when he would have quite enough to fret about just looking out for himself while he was away fighting.

She would go, of course she would.

But she wasn’t happy about it. She had never spent time away from Bermondsey before; it was a modest area, but it was home.

In terms of what needed to be done in order for her to go, it wasn’t too bad. Peggy and Bill rented their house and it had been let to them along with the furniture they used. They didn’t have many possessions and very few clothes, and so Peggy knew that with Bill away she could easily make use of Barbara’s offer of storage space in the eaves of her and Ted’s roof, which was reached through a small trapdoor on their tiny landing, for Peggy to put their spare clothes and some of their wedding present crockery and so forth, if she did decide to be evacuated herself.

Peggy was sure that if she supervised the packing then Ted would actually do it for her, as she got so tired these days she couldn’t face the idea of putting things in tea crates (of which Ted could get a ready supply at the docks) herself, and then Ted would borrow a handcart to lug everything over to his so that it could be safely stowed away.

‘Go,’ Bill urged once more, cutting across her thoughts. ‘Go and stay somewhere that’s safer – you’ll be doing it for our baby, remember.’

Peggy understood what he was saying, but she could feel the ties of community entwined around her very tightly, and so she and Bill had to talk long into the night before she could find any sense of peace, and it was only after he had held her snugly for an hour once they had gone to bed that she was able properly to rest.

Chapter Four (#ulink_8b30ab80-df73-5f6b-bdbb-efd03940988c)

The next morning at just gone seven Peggy kissed Bill long and hard in the privacy of their home, and then, after he’d swung his heavy canvas kitbag up and onto his shoulder, she walked at his side to the church hall, where there was already a heaving group of raw recruits and their loved ones saying goodbye as uniformed officers and civilian officials walked around and about with clipboards and organised those leaving into groups designated for particular buses to Victoria station.

During her pregnancy Peggy had discovered that tears were never far away, and this Friday morning was no exception. She also felt a bit dizzy after just a couple of minutes, standing on the edge of the melee alongside Bill, as there were so many people bustling this way and that that it made for the sort of constantly changing vista that led to travel sickness.

Bill smiled at her and said, ‘Peg, don’t wait around. You ’ead on to your Barbara’s for a cup of tea. There’s no point you stayin’ ’ere just to wear yerself out. We said our goodbyes earlier and now your work is to look after our babbie. I see Reece Pinkly over there and so I’ll ’ave someone to look after me, don’t you fear, my love.’

It was too much for Peggy, and she found herself violently sobbing on Bill’s shoulder.

Just for a moment, she wished she wasn’t an expectant mother. It felt too much responsibility, and in any case, just what sort of world was it going to be that in a very few months she would be bringing a poor defenceless baby into? How would she be able to manage? What if the future were very dark for them all? There was no guarantee that the Germans wouldn’t end the war victorious, and then where would they all be?

Bill held her close for a minute and then he took a step back and looked at her seriously. ‘Peggy, it’s time for you to go,’ he said softly but firmly, and he stepped forward to give her back a final rub. ‘I’d say I’ll write, but you know that’s not my strong point… Still, I’ll do my best, Peg.’

With great reluctance Peggy edged away from him, not daring to look back as she knew that if she did, she wouldn’t be able to let him leave.

Peggy made her way slowly out of the church hall and crossed the street to stand with some other wives as they gathered on the pavement outside the meeting point.

She was unable to say for certain if she had managed to grab a final glimpse of Bill as she craned her head this way and that to look through the open door to the church hall, trying to pick him out from the constantly moving mass of people. Unfortunately the men all looked similar in their dark wool suits and Homburg hats (most of them having dressed in their best clothes to go), while more and more wives and children were now cramming the pavements around her, squeezing close, and suddenly Peggy felt nauseous and unbearably oppressed.

She staggered slightly for the first few steps as she headed in the direction of her sister’s house but then she felt calmer and a little more certain of herself as she moved along the pavement.

There was a thrumming engine noise behind her, and a horn blasted out as a gaily painted charabanc that looked so hideously at odds with Peggy’s dark mood began to inch by.

With a whump of her heart, Peggy saw Bill standing up in front of his seat, with his face pressed sideways to the narrow sliding bit at the top of the window, and he was waving frantically at his wife. Peggy could see the shadow of Reece Pinkly alongside.

‘Peggy Delbert, I love you!’ was a shout Peggy thought she heard above the din as now some wives and kiddies were pushing past her to run right beside the moving vehicle, some even banging the charabanc’s sides as it edged its way through the grimy street.

She hoped she had caught Bill’s words – he clearly had been saying something to her – but she couldn’t prevent a slither of concern that perhaps some little mite would take a fall as he or she ran beside the bus, slipping to a heinous end under the rear wheels, and so she felt thoroughly discombobulated, quite done in with her undulating feelings. Bill’s declaration of what she hoped was love now felt tainted somehow by the worry of the children running beside the large vehicle.

‘Bill, I’ll look after our baby, I will, I will,’ she shouted back, her hands either side of her mouth in an attempt to make her voice as loud as possible. She hoped against hope that her husband could feel the strength and resolution in her cry, even though she knew he was already out of earshot.

She hoped also that he knew she was feeling the pain of his absence almost as sharply as if she had lost one of her own limbs. She had married him for better or for worse, and they had had the ‘for worse’ for too long – she was now determined on the ‘for better’.

Evacuation simply had to be for the better. Didn’t it?

Chapter Five (#ulink_2ea49ec6-72c5-5e3d-abc1-a030d7e62e93)

‘Yer better give Barbara ten minutes on ’er own with our Jessie and Connie,’ advised Ted, when he ran into Peggy as she was trudging towards her sister’s house just a couple of minutes later. ‘We’ve jus’ told ’em they’re to be evacuated on Monday mornin’ along with the rest of their school an’ it didn’t go down well.’

Peggy couldn’t fail but notice how deep were etched the lines on the face of her brother-in-law all of a sudden. He was only in his early thirties, but just at that moment, as he stood half in a weak shaft of early-morning sunlight and half in heavy shadow, she could see exactly how Ted would look at age sixty. Then she hoped that he would make it to such advancing years, and not be cut down in his prime as many people would inevitably be during the war.

‘How did they take it, the poor little mites?’ she asked, swallowing her sad feelings down and trying to concentrate instead on Connie and Jessie. ‘I really feel for them as they’ll hate being apart from you and Barbara. And I’ve promised my Bill that I’m going to go out of London too. I don’t really want to, but if I stay and something happens to the baby, then I’ll never forgive myself, and he won’t either.’

Ted nodded to show his approval of Peggy’s decision, and then he confessed that it had been very hard for him and Barbara to find the right words to break the news of the forthcoming evacuation to the children.

They had found it a difficult line to tread, he explained, as they wanted to make it sound as positive an experience as possible for Jessie and Connie, without there being any option for them not to go, but with it all being couched in a manner that wouldn’t make the children worry too much once they had gone to their billets about Ted and Barbara remaining in London to face whatever might be going to happen.

‘Connie seemed the most taken aback, which were a shock, but that could be because we’re more used to seeing Jessie lookin’ bothered an’ so we didn’t really notice it so much on ’im. Still, it were a few minutes I don’t care to repeat any time soon, and Barbara were lookin’ right tearful by the time I ’ad to go to work and so she’ll be glad to ’ave you there, I’m sure,’ Ted confided to his sister-in-law.

Peggy went to touch Ted on the arm in comfort, but then thought better of it. He looked too tightly wound for such an easy platitude.

She contented herself instead by saying she was sure that he and Barbara were doing the best thing and that they would have broken the news of evacuation to the children in exactly the right way.

Nearly everyone, she’d heard, was going to evacuate their children out of London and so it wouldn’t be much fun for those that didn’t go, she added, as they wouldn’t have any playmates, while schooling would be a problem, too as the government was going to try and make sure that all state schooling was taken out of the city.

Peggy thought she saw the glint of a tear in the corner of one of Ted’s eyes as she spoke, but then he cleared his throat sharply as he averted his head, and added quickly that he had to go or else his pay would be docked, and with that he walked away curtly before she could say anything else or bid him farewell.

Peggy remained where she was standing, wondering if Barbara had had long enough on her own with the children, or if she could go and call on her now. She felt she had been on her feet for quite some time already that morning and over the last few days she had grown a bit too large not to be having regular sit-downs.

Then she saw Susanne Pinkly hurrying in her direction, with a cheery sounding, ‘Peggy, I need to talk to you but I’m late for school – can you walk over to St Mark’s with me? I was going to come and see you at lunchtime, but this will save me an errand if you can spare me a couple of minutes now?’

Peggy and Susanne Pinkly were good friends, having been at school together from the age of five, and later in the same intake at teacher’s training college before they finally simultaneously landed jobs at the local primary school where they had once been willing pupils.

They’d also spent an inordinate amount of time during their teenage years discussing the merits of various local lads and how they imagined their first kiss would be. Susanne was fun to be with, and was never short of admirers who were drawn to her open face and joyful laugh. Peggy had often envied Susanne her bubbly nature that had the men flocking, as Peggy was naturally more serious and introverted, and so when Bill had made it clear he thought her a bit of all right, it was a huge relief as she had been fast coming to the conclusion that the opposite sex were hard to attract.

Although some schools wouldn’t let married teachers work, fortunately this hadn’t been the case at St Mark’s Primary School. While Susanne was still an old maid, being positively spinsterish now at thirty-one, Peggy had married Bill just a term into her first job without much thought as to what this might mean for her in the working world. Luckily St Mark’s didn’t have a hard and fast policy as regards making married female employees give up work, as some schools did, which Peggy found herself very pleased about, and increasingly so when she didn’t become pregnant for such a long time. She couldn’t have borne being stuck at home on her own and without anything to do – she would have felt such a failure, she knew.

However, when she fell at last with the baby, Peggy had had to stop working at the end of the summer term as her nausea had got so bad, and since then she very much missed her lively pupils and the joshing camaraderie of the staffroom. Bill spent long hours at the bus depot, and he was rather fond of a tipple with the lads on a Friday and a Saturday night if he wasn’t rostered on the weekend shifts. Barbara’s time was taken every weekday by her job at the haberdashery, and so quite often the days felt to Peggy as if they were dragging by. She discovered all too quickly that there was only so much layette knitting an expectant mother could enjoy doing.

It was still up in the air whether Peggy would ever be able to return to work following the birth of the baby, as most employers didn’t want a mother as an employee, and Peggy knew that if in time she did want to return to her classroom – after the war with Germany was over, of course – then she would have to make a special plea to the local education authority that she be allowed to go back to work.

Before that could happen, she and Bill would have to decide between themselves that she should resume her job, and then they would need to sort out somebody to look after the baby during the day, which might not be so easy to do.

Bill didn’t earn much as a bus driver (his route was the busy number 12 between Peckham and Oxford Circus), and aside from the fact that Peggy missed her pupils, and she knew she had been a good teacher, she suspected too that one day she and Bill might well feel very happy if she could start to add once again to the family pot by bringing in a second wage.

Peggy turned around and, linking arms with her friend, she walked along with Susanne, who wanted to see if Peggy was going to evacuate herself.

When Peggy nodded, Susanne cried perhaps a trifle too gaily, ‘Music to my ears! I’m having to stay behind to work at the bakery, as you know Ma’s been taken poorly and Reece is leaving today with your Bill. But if you’re choosing to be evacuated and are planning on going on Monday as most people round here seem to be, then St Mark’s needs another responsible adult to help escort the children to wherever they are being sent to, and I couldn’t help but think of you! So far there’s Miss Crabbe and old Mr Hegarty to look after them – well, Mr Jones is going too, but he won’t want to be bothered with the nitty-gritty, as it were, and in any case, he’s coming back just about the next day. One-Eye Braxton will be there and the kiddies run rings round him – and so I thought you would be the perfect person to go and keep an eye on both pupils and teachers.’

There was definitely a logic to this despite the chirpy tone of Susanne’s words, Peggy could see, as she was familiar with the children and they with her, and she knew the quite often crotchety Miss Crabbe (‘Crabbe by name, and Crabby by nature’ was Peggy and Susanne’s private joke about her) and the ancient Mr Hegarty (who was increasingly doddery these days after teaching for over forty years) would make for dour overseers for the evacuation journey for the children, and with headmaster Mr Jones planning on not sticking around…

And if Peggy went with the children of St Mark’s, then it would probably mean that she would end up being billeted near where Jessie and Connie would be, and this would be reassuring for Barbara and Ted; and for herself too, it had to be said.

They’d reached the school gates, and Susanne nodded and then smiled encouragement at Peggy, obviously willing her to say yes.

‘Let me think about it overnight, and I’ll let you know first thing in the morning as I’m not quite certain about the other options for the evacuation of expectant mothers,’ Peggy said, trying to look resigned and as if she shouldn’t be taken for granted, but failing to keep the corners of her mouth from turning up into the tiniest of smiles.

Then Peggy caught Susanne looking pointedly at her expanded girth so she added, ‘I think it’s probably fine for me to come with your lot, but I just want to consider it for a while as I don’t want to promise you anything I can’t actually do.’

Susanne was already nipping across the playground towards the steps up to the girls’ entrance as she called over her shoulder, ‘Honestly, Peggy, it’s just to make sure they don’t get up to too much mischief on the train – and that’s just the teachers! And Mrs Ayres will be there too, and Mr Braxton, and so you won’t be too heavily outnumbered by the kiddies.’

This latest comment wasn’t necessarily as hugely reassuring to Peggy as Susanne probably meant it to be, because although as sweet-natured a widow as Mrs Ayres undoubtedly was, she was a gentle soul, and even the youngest children could boss her around with absolutely no trouble, while Mr Braxton, who had had such a severe facial injury in the Great War that meant he’d lost an eye and part of a cheekbone, and who now wore a not very convincing prosthetic contraption that attached to his spectacles, also had problems in keeping the children in line, in large part as they didn’t really like looking directly at him.

Peggy sighed. She could already imagine how this was very probably going to work out for her.

Several minutes later, as Peggy made her way at long last over to Barbara’s, Jessie and Connie were walking along the street to school in the opposite direction, and they were so deep in conversation that they didn’t notice their auntie until they were almost level with her.

Peggy thought they both looked wan and anxious – the news of leaving their mother and father to head for pastures new with their classmates had obviously hit them hard.

‘Hello, you two. You’d better look sharp or else you’re going to be late,’ she said. ‘But first, I’ll tell you a secret. If it helps cheer you up, I think I might be coming on the train with you and your fellow school pupils on Monday. Won’t that be fun?’

They stared at each other with intent, serious expressions, and then they all laughed as Peggy had to add, ‘Well, maybe “fun” is the wrong word, but I daresay you know what I mean. If I can get a billet near to you, then you’ll know there’s always me to come to if either of you feel a bit miserable. And I shall be able to come to you if I’m feeling a bit sad about being away from home too. Is that a deal?’

Judging by their nods, it looked as if a pact had been made.

Chapter Six (#ulink_ed1f17b0-a3f4-53ab-b53e-d87bce90f7ba)

Barbara was standing on the doorstep looking out for Peggy while polishing the brass door knocker, door handle and house number.

‘I’ve already told Mrs Truelove that I can’t go in today as I’ve got to get things organised, and she wasn’t thrilled but…’ Barbara’s voice drifted away as she’d already turned on her heel to stomp off towards the kitchen, her footsteps ringing out on the brown linoleum that floored the narrow hallway at number five Jubilee Street.

Peggy followed wearily in her younger sister’s wake (there was only the one year between them), very much looking forward to sitting down and enjoying a restorative cup of tea. It wasn’t yet half past eight but already Peggy was quite done in.

Half an hour later she felt much better, as Barbara had also made her eat some hot buttered toast while Barbara jotted down a long to-do list, and an equally lengthy shopping list.

‘Ted and I decided before we got out of bed this morning that we’re going to use our rainy-day money to send them away in new clothes. Let’s see how much is in the biscuit tin,’ said Barbara.

Peggy was surprised at this. Most families scrimped and saved to put a little by for emergencies, but now Barbara seemed happy to dip into this fund when actually, as far as Peggy could see, the children already had perfectly acceptable clothes that were always neatly pressed and mended, and that were nowhere near as threadbare as some that many other local children had no other option than to wear.

While Barbara and Peggy had been born and bred within the sound of church bells that they still lived within hearing distance of, their father had been a shopkeeper, and so they had grown up in relative comfort when compared to that of many of their contemporaries, Bermondsey being known throughout London as being a very poor borough. They had been allowed to stay at school past the age of fourteen, when a lot of their friends had been made to leave in order that they could go out to work to bring another wage in to add to the family’s housekeeping.

Peggy and Barbara’s mother had been very insistent that they had elocution lessons, and the result of this was that although without question they talked with a London accent, it wasn’t the broad cockney spoken by Ted and Bill, who joked that their wives were ‘very BBC’.

While this wasn’t strictly true as the received pronunciation of the broadcaster’s announcers was always distinctly more plummy (in fact, laughably so at times), nevertheless the sisters knew that their voices did sound posh when compared to most people in Bermondsey. Jessie and Connie had also been encouraged to speak properly by Barbara, another thing that hadn’t endeared Jessie to Larry, who had the slightest of stammers.

Barbara was always very set on keeping up family standards, and this required her taking good care of Jessie and Connie’s clothes, making sure they were always mended, clean and pressed, while Ted buffed and polished their leather T-bar sandals every evening. It gave both parents pleasure to see their children bathed and clean, and neatly turned out.

This sartorial attention was a whole lot more than many other local parents managed where either their children or themselves were concerned, although Peggy had some sympathy for why this might be as she could see it was very difficult for some families, who might have, perhaps, more than ten children to look after but with only a very scant income coming into the home each week.

Nevertheless, she suspected that when her and Bill’s baby arrived, she would find herself equally as keen to keep up the standards already heralded by Barbara.

Now Peggy watched with slight concern as Barbara climbed precariously up onto a stool to lift off the high mantelpiece above the kitchen hearth a slightly battered and dented metal biscuit barrel that commemorated King George V coming to the throne in 1910.

Peggy remembered this biscuit barrel with fond thoughts, as it had sat in their parents’ kitchen throughout her and Barbara’s childhood. Although Peggy was the oldest daughter, and therefore in theory should have had the first dibs on their parents’ possessions, when it came to closing up their house after they both died within months of each other, Peggy did a magnanimous act. It was just before Barbara and Ted’s marriage, which meant it was a year after Peggy and Bill’s own nuptials, when their mother succumbed to influenza and their father died not long after of, they liked to say, a broken heart. With only the slightest of pangs as she had always loved the biscuit barrel, Peggy had allowed her sister to stake, claim to the majority of their mother’s possessions, including the biscuit barrel, as Barbara was poised to set up her own home and Peggy had just about got herself and Bill comfortably fitted out by then.

Now, Barbara clunked the barrel down and onto the table, the number of large pennies in it adding considerably to its apparently hefty weight. She loosened the lid with her nails until she was able to work it off, before tipping the contents onto the maroon chenille tablecloth that adorned the kitchen table.

Peggy had long teased Barbara about her beloved tablecloth that had to be removed whenever the family ate, or when anything mucky was being done on the table. Barbara could be very stubborn if she chose, and so she resolutely refused to accept the tablecloth, with its extravagant fringing, was anything less than practical. Now, at long last, it came into its own as it turned out to be a good place to sort the pile of money that had been in the tin as the chenille prevented the coins rolling around too much, and it cushioned too the several notes that had tumbled from the biscuit barrel.

Barbara counted out five pounds and replaced them in the barrel.

Then she totted up what was left. It was a small fortune: a whole £37 15s. 7½d. With a raise of her eyebrows Barbara put another £20 back in the kitty, and then a handful of silver half-crowns and florins, and then she clambered laboriously back onto the stool to return the biscuit barrel to its home on the mantelpiece.

‘Goodness,’ said Peggy enviously, as her and Bill’s rainy day money had never broken the £10 barrier. ‘I had no idea.’

‘Ted’s been doing overtime, and of course I always try and put away all of my wages. But I won’t deny that a lot of scrimping and saving has gone into that blessed tin,’ said Barbara. ‘We’ve been saving extra hard ever since the children started school and we had even been wondering about a proper holiday next year, and a mangle for the washing and a new bed for Jessie. But now I want Connie and Jessie to be evacuated looking as if they are loved and cared for, and as if we think nothing of sending them away in new clothes. I think that might help them get a better class of family at the other end, don’t you think?’

Peggy wasn’t certain that would be the case, but she decided to keep quiet.

Some Bermondsey families would be hard-pressed even to give their kiddies a bath or to send them off in clean clothes, she knew, and so it could be that some of the host families would take pity and choose those clearly less advantaged first. She knew too that some of the children were persistent bed-wetters, and so she hoped that wasn’t going to cause too many problems further down the line.

Peggy made a decision not to ponder any further on this just then, as it seemed too loaded with opportunity for fraught outcomes. Although, of course, she hoped that Barbara’s view was the correct one, rather than hers.

After one last cup of tea and a final peruse of Barbara’s list, the sisters decided they would head up to Elephant and Castle to see what they could buy.

Barbara carefully placed her to-do list in one pocket and her shopping list in the corresponding pocket on the other side of her coat front, and then she tucked her purse away out of sight at the bottom of her basket, hidden under a folded scarf.

Peggy took the opportunity to spend a final penny before slipping into her lightweight mackintosh, as these days with the baby pressing on her bladder she needed to go as often as possible.

And then the sisters left for the bus stop so that they could make the shortish ride to Elephant, as the area was known locally.

At school meanwhile, Susanne Pinkly was experiencing a rather trying first lesson of the day.

Understandably, none of the children had their minds on their timetabled lesson for first thing on a Friday, which was arithmetic; even at the best of times that was never an especially pleasant start to the final school day of the week.

This particular morning, all the whole school wanted to do was talk about the evacuation, and what their mothers and fathers had told them about it.

Susanne could completely understand this desire, but she wasn’t utterly sure what she should say to the children as she didn’t want to make a delicate situation worse, or to make any timid pupils feel even more fearful about the future than they would be already.

Susanne always kept an eye out at playtime for Jessie Ross, as she knew the bigger boys could be mean to him. She had a soft spot for Jessie as he was one of the few children who patently enjoyed their lessons (very obviously much more than his sister did, at any rate) and who would try very hard to please his teacher.

Jessie was lucky to have a sister like Connie to stand up for him, Susanne thought, although just before the Easter holidays Ted had requested to headmaster Mr Jones that Connie be moved to the other class for their forthcoming senior year at St Mark’s as he and Barbara felt that Jessie was coming to depend too much on his twin sister fighting his battles for him.

Sure enough, at the start of this autumn term the twins had been separated and now were no longer taught in the same class. Susanne had suggested she keep Connie, and that Jessie would be moved in order that he could be taken out of Larry’s daily orbit, but Mr Jones said that he thought that might make Jessie’s weakness too obvious for all to see, and that the likely result would be that Larry’s bullying would simply be replaced by another pupil becoming equally foul to Jessie.

Generally, the teachers didn’t think Larry was an out-and-out bad lad as such, because when he forgot to act the Big I Am, he seemed perfectly able to get on well with the other children, Connie having been seen playing quite amiably with him on several occasions. The teachers believed that he had a troubled home life, as his park keeper father was well known for being a bit handy with his fists when he was in his cups, while Larry’s mother bent over backward to pretend all was well, despite the occasional painful bruise suggesting otherwise. The days Larry came in to school looking a bit battered and with dried tear tracks under his eyes was when he was prone to go picking on someone smaller than him. It was rumoured that Larry’s father had been dismissed from his job the previous spring, and Susanne was sorry to note that there had been a corresponding worsening of Larry’s behaviour since then.

Having just spoken with Peggy made Susanne think afresh of Jessie, as she knew Peggy adored her niece and nephew, but that Peggy always wished that Jessie had an easier time in the playtimes and lunch breaks at school than in fact he did.

So Susanne had been intending to pay special attention today to see how he was faring now that he would be getting used to not having his sister nearby at all times. But now Susanne had to put that thought to the back of her mind as she had just had a brainwave.

She would acknowledge the forthcoming evacuation but in a more oblique way than discussing it openly. She would do this by talking about some London words and sayings that might not make much sense to people who came from outside the confines of Bermondsey.

After making sure Larry was sitting at his desk directly in her eyeline so that she could keep tabs on him, Susanne got up from her seat behind her desk at the front of the class, smoothing her second-best wool skirt over her generous hips and checking the buttons to her pretty floral blouse were correctly fastened (to her embarrassment, she’d had a mishap with a button slipping undone the day before, and had the chagrin of catching a smirking Larry and several others trying to sneak a sly glimpse of her petty).

Going to stand in front of the blackboard, Susanne began, ‘Who knows what the word “slang” means?’

A bespectacled small girl called Angela Kennedy who sometimes played with Connie after school put her hand up in the air, and when Susanne nodded in her direction, she answered, ‘Miss, is it a special word fer sumfin’ that’s all familiar, like?’

‘Sort of, Angela. Well done,’ said Susanne. ‘Slang can vary from city to town to village, and might be different whether you live in the town or the country, or whether you are a lord or a lady, or you are just like us. Slang words are those that quite often people like us might use in everyday life, rather than when we could choose the more formal word we would find in the dictionary. And I know that following our lesson last week on dictionaries, you all know very well exactly how a dictionary is organised and all the special information you can find there!’

There were a few small titters from the pupils who didn’t have the same confidence in their ability to find their way around a dictionary that their teacher apparently had in them.

Ignoring the sniggerers, Susanne went on, ‘Now, can anybody here tell me an example of a word that is said around where we live in Bermondsey, but which might not be understood over in Buckingham Palace, say, which I’m sure we’d all agree is a whole world away from what you and I know in our everyday lives, even though the palace itself is close enough that we could all bicycle there if we wanted to?’

‘Geezer,’ yelled a boyish voice from the back of the class.

‘Okay, geezer it is,’ said Susanne. ‘So, has anyone got another perhaps more polite or proper-sounding word that might be the same as geezer but that wherever you lived in the British Isles you would know that everybody who heard you say it would understand what you were talking about?’

She was hoping one of her pupils would have the nous to say ‘man’.

‘Bloke,’ said Larry.

‘Chap.’

‘Guy.’

‘Guv’ner.’

‘Guv.’

‘Anything else?’ asked Susanne.

‘Cove,’ said Jessie thoughtfully, ‘although I prefer dandy.’

Somebody gave a bark of laughter.

Jessie really didn’t help himself sometimes, Susanne thought.

‘Nancy boy,’ Larry yelled as he wriggled in his chair, trying to turn around to look at Jessie. ‘That’s you, Jessie, er, Je… Jessica Ro—’

‘Behave yourself, Larry, and keep your eyes turned to the front of the classroom at all times. Ahem. What I was hoping was that someone might say “man”,’ Susanne interrupted very sharply without pausing between her admonishment of Larry and voicing what the word was that she had been wishing a pupil would say. ‘Now, what about one of you coming up with another slang word that you can think of where several others can be used?’

‘Bog.’

‘Thank you, Larry,’ said Susanne in the sort of voice designed to shut Larry up, but that at the same time indicated to both Larry and the rest of the class that Larry wasn’t really being thanked at all and that really it was high time that he buttoned his lip.

‘Lavvy,’ somebody shouted out before Susanne could say anything else to get the lesson back to where she wanted it to be.

The class was waking up now to what Susanne was wanting from them. Almost.

‘Crapper.’

‘WC.’

‘Jakes.’

‘Karzi!’

Susanne tried not to think of what any of the posher billets might think to language such as this as she attempted and failed to conceal a smile, although she supposed they would most likely all have to ask their way to the outhouse or the toilet in their new homes at some time or other.

‘A polite term, children, remember,’ she said encouragingly.

The following silence told Susanne that ‘polite’ was quite a hurdle for some to overcome.

‘Pissoir,’ Jessie called eventually, looking down quickly, although not quickly enough that Susanne couldn’t see a cheeky cast to his eyes.

Their teacher had to turn to write on the blackboard so that her class couldn’t see the lift of her eyebrows that indicated she was suppressing a feeling lying smack bang in the centre of exasperation and humour.

East Street market was only a ten-minute stroll from Elephant along the Walworth Road, and when Elephant failed to come up to Barbara’s expectations as to the shopping opportunities, and as Peggy felt that she had a second wind as walking around was making her feel better, they decided to head towards Camberwell so that they could go to the market.

One purchase had been searched for in Elephant without success. Ted already had from his and Barbara’s honeymoon a long time ago a smallish cardboard suitcase that had long been holding Jessie’s large collection of painted lead soldiers in their colourful garb of Crimean War uniform (the softness of the metal having meant that Ted was forever straightening bent rifles or skew-whiff feather hackles on the headwear of the tiny fighters). Barbara had decided that Jessie could be sent off with his possessions carefully stowed in that suitcase, with the soldiers left behind in a drawer in his bedroom ready and waiting for him to play with after he returned from evacuation.

A second suitcase was needed, this time for Connie, as on the bus to Elephant Barbara had realised as she and Peggy talked about the evacuation that there wasn’t a guarantee that both children would be kept together and so each child needed to be catered for and packed for quite separately.

There had already been a run on all the small cases, though, as presumably other parents had been quick to snap them up for the evacuation, and this meant that only the big cases were left and they were all too large for even Peggy to lug about.

Barbara cursed roundly when she realised this, and then Peggy sat down on a step to wait as Barbara darted in and out of several shops just to be certain, before she returned empty-handed and announced that they would have to head along the Walworth Road in the direction of Camberwell in order that they could go to East Street market.

‘Barbara, I’ve been thinking,’ said Peggy as they walked along. ‘I’ve a spare cardi that Connie can take – it’ll be a bit big, I know, but it’s practically brand new, and she can roll up the cuffs, and actually she’s grown so much over the summer holidays that I don’t think it will totally swamp her. It’s that one with the little buttons on that you liked when we took the children egg-hunting in the park at Easter.’

Her sister smiled her thanks, and promised that, her treat, they would stop for a bun and a hot drink after they had finished their shopping.