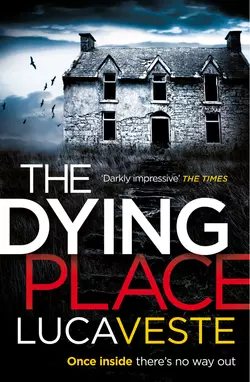

The Dying Place

The Dying Place

Luca Veste

A FATE WORSE THAN DEATHDI Murphy and DS Rossi discover the body of known troublemaker Dean Hughes, dumped on the steps of St Mary’s Church in West Derby, Liverpool. His body is covered with the unmistakable marks of torture.As they hunt for the killer, they discover a worrying pattern. Other teenagers, all young delinquents, have been disappearing without a trace.Who is clearing the streets of Liverpool?Where are the other missing boys being held?And can Murphy and Rossi find them before they meet the same fate as Dean?

LUCA VESTE

The Dying Place

Copyright (#ulink_88a8d28c-2bf4-5970-af7f-f5ef0827f4bf)

AVON

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Luca Veste 2014

Cover image © Alamy 2014

Cover design © ClarkevanMeurs Design

Luca Veste asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007525584

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007525560

Version: 2015-07-27

Dedication (#ulink_45f9257b-4e6c-5666-8a52-717a9abb9d0f)

For Angelina ‘Angie’ Veste

11/04/1936 – 07/05/2014

My nana. My nonna.

She loved her family and her family loved her.

Contents

Cover (#u81f8eec7-fff5-54ac-af17-530801d9779b)

Title Page (#u8eee9b65-55cb-5721-9567-43fc95964906)

Copyright (#u34aac26a-bbb2-5481-93fa-cd678e245b77)

Dedication (#u902e6d7c-1c8d-519d-9f0c-5cf99d049f69)

Now (#u16b4a411-d119-56a3-85e0-5573581056a4)

Before (#ua93aff7c-696d-59b0-a94d-edb151cbb204)

Part One (#ud5a8794f-ca7d-5e77-b205-af3550668c52)

Chapter 1 (#ua774fc99-d0d4-5ee3-b461-f8ac26c86bca)

Chapter 2 (#u760a724c-baa9-5406-8f48-9b6214265c69)

The Farm: Six Months Ago (#ude8028a9-65be-5837-ad73-6b9ab6b67939)

Chapter 3 (#u2908180c-038d-55bb-881f-17b2e347c1b7)

Chapter 4 (#u5eb6e40e-2ba5-572f-849a-0ea4d1c6d5fa)

Chapter 5 (#u4314c8b3-7a2c-533c-a038-7ab7bb0f6be8)

Chapter 6 (#ufb4ea7b1-eea5-5ea3-925c-7a73886ececa)

The Farm: Five Months Ago (#ua1b81287-71b4-5f0a-8c91-66cf0ef8efed)

Chapter 7 (#u43e07254-2f13-5b3a-b401-6f94ec834f19)

Chapter 8 (#u030dcbde-e7ba-5ae2-ad5a-8442fccfd71f)

Chapter 9 (#u5e972e2b-6d95-5301-9dda-a1aa14b66e79)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Farm: Three Months Ago (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Youth Club (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Farm: Three Days Ago (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Farm: Two Days Ago (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Farm: Two Days Ago (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Farm: Yesterday (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Youth Club (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Home: Six Months Ago (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Toxteth: Liverpool 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Bootle (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Peter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

In Conversation with Luca Veste (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Now (#ulink_26c50eeb-ce74-584a-a552-0c7b80493571)

No one believes you. Nothing you say is the truth. They know it every time you open your mouth and start speaking, hoping to be believed. Everything is just a lie in disguise, dressed up nice, trying to be something it’s not.

Mutton dressed as lamb.

That’s just how it is. You go down the social – or the jobcentre as they call it now, although that’ll probably change to something else soon enough – and try to explain why you’re still worth sixty quid a week of taxpayers’ hard-earned money. Trying to justify yourself even though you haven’t worked in years. Get that look which seeps into you after a little while.

I’ve heard it all before, love.

There’s no let-up. Being judged at every turn. Lucky enough to have more than one kid? Unlucky enough to lose your part-time job working the till at some shitty shop? For your fella to piss off with some slag from around the corner? Doesn’t matter, shouldn’t have had more kids than you can afford. Doesn’t matter that you’re a single parent – I’m paying your benefits.

You live on a council estate, on benefits, and that’s it. You’re scum. Do not pass go, here’s a few hundred quid to pay some dickhead landlord who thinks five ton isn’t too much for a terraced house that’s overrun with damp. Mould growing on the walls if you dare put any furniture too close to it.

Your kids then become scum as well. Shit schools, shit kids. Bored with life, constantly pissed off because you can’t afford the latest frigging gadget that Sonyor Apple put out. Every six months without fail, something new that every other kid in the school has, that they can’t be without.

You try. You really do. But it’s never enough. Sixteen hours working in a supermarket, a few hours doing cleaning. Bits of crap here and there. Never enough.

No one believes you.

Your kids get older. Get in trouble. Bizzies knocking on your door at two in the morning, hand on the back of your fifteen-year-old son.

He’s had too much to drink. Could have got himself into a lot more trouble. Should keep an eye on him more, love.

That judgement again. Always there, surrounding you.

You try and explain. Tell them he’d said he was staying at his mate’s, or staying at his uncle’s house. With his cousins.

Get that look back.

I’ve heard it all before, love.

You want to scream. You want to pull the little bastard into the house by his stupid frigging head and beat the shit out of him. Like your dad would do to your brothers if they ever got caught doing stupid shit.

You try your best. Every day. It’s never enough. The crap wages you get for working two, three, different jobs barely matches what you were getting on benefits. So you think, what’s the point? You’re tired. You want to be lazy. Exhausted by the sheer weight of being alive. Everyone else around you seems to be doing sod all. You want to do that for a while.

The kids get worse. All boys, so the house is either deathly quiet whilst they’re all out, getting up to God knows what. Or, it’s a cacophony of noise. The moaning, the groaning. The smells of teenagers on the cusp of manhood, burning into your nostrils, hanging in the air.

No one believes you.

When one of them doesn’t come home for days, you shout and scream as much as you possibly can, but no one cares.

They think he’s just done a bunk. Gone to see a girl. Gone to get pissed, stoned, off his face somewhere. He’ll turn up eventually. They always do.

Your kind always does.

You try and tell them it’s different. That your lads have always been good at letting you know where they are, or if they’re going to be away for any time at all. That they wouldn’t just leave without saying anything.

They give you that look.

I’ve heard it all before, love.

You try and get people interested, but no one cares. The papers aren’t interested. Thousands of people go missing every year. No one cares about your eighteen-year-old son, missing for weeks … months.

You believe he’s okay. You make yourself believe it.

You know though. As a parent, you know.

Something has happened to him.

It’s not until you’re watching his coffin go behind the curtain – fire destroying everything that made him your son and turning it into ash – that they start to believe you.

It’s too late now, of course.

Sorry, love.

Before (#ulink_92398b20-33ed-5b96-a1d4-10fbe21011ac)

It wasn’t supposed to happen this way.

The plan hadn’t been for him to be in this position. Not yet, anyway. He was supposed to be there to see it through. It was his idea, his design. None of them would have thought of doing it without him. He was the catalyst, the spark that brought them all together.

That’s the problem with making plans … the master in the sky laughs.

Flat on his back in the street outside his own home, a ghost of a smile playing across his face. Clutching his chest as his heart threatened to beat its way out, his vision going blurry. Not being able to see if there really was an elephant sitting on him, which was how it felt – crushing weight bearing down, strangling him, cutting off his breath.

He should have known he was too old for it. Not that it would have made a difference. As soon as they’d come around to his plan, he wasn’t going to hide away whilst all the fun went down without him. He should have just stayed inside with a small whisky and some shite on the TV. Relaxed. Then maybe he would have had a few more years.

They’d come back again. Laughter and voices penetrating the walls from outside. No respect for people’s private property. Just sitting on the wall outside his house, throwing their empty cans into his little front garden.

He’d checked the time on the clock that took pride of place on his mantelpiece, a beautiful old-fashioned gold carriage clock which had been a retirement gift from a client.

Half past midnight. Way past his usual turning-in time. Early to bed, early to rise. An old motto, but one he stuck to usually.

Something that lot out there wouldn’t have a clue about.

He had noticed the area changing around him for a while. What used to be a nice area of West Derby was being overrun with those yobs. Complete with their strange bastardisation of the Scouse accent. Couldn’t understand them most of the time, which was probably just as well. Couldn’t imagine they’d have anything of value to say.

Back in his day, if you left school with no qualifications – as was the norm, to be fair – you took whatever job you could get, and got on with it. He’d left school at fourteen and went straight to work, doing odd jobs here and there. Joined the army a few years later, ended up in Korea. Got back home and worked for over forty years painting and decorating. Set himself up with a nice little business with enough customers to always have a bit of work on the go. Put a bit of money aside for the retirement years with the missus. They could have lived quite well for a good while.

And then he was alone.

Those lads wouldn’t know the meaning of work. Not employed, in education or training, as they say. A million of them apparently now, according to the papers. No jobs, you see. Whole world has gone the same way. It seemed like he’d blinked and the next minute everyone was saying it was better to live in China than anywhere else. Who’d have thought that would ever happen?

She was ten days off sixty-five when they got to her. Walking back from the post office. Doctors told him it was probably a coincidence. Didn’t matter that she was left in the street for dead, she could have gone at any moment. He never believed them.

He would go for a walk every day, tried to keep fit. Walked up to the village, into the county park. Past the red church sign he always stopped to read.

Church of England

St Mary The Virgin

West Derby

St Mary the Virgin. Odd name to give to a church. But then, he found most things about churches odd.

He’d walk up the lane which ran alongside it, trees crowding in on each side. He’d find his bench, have a nice sit down and watch the world go by. Chat to people every now and again. Most people just walking on by, or smiling politely whilst thinking about their quickest escape route.

The first time they’d showed up outside his house, he thought a quick word would do the trick. Not a chance. He’d given them an hour, until the shouting had become too much. So loud he couldn’t even hear the TV properly. Just a quiet word, he thought, let them know someone lived here, that he wasn’t going to let them take over his front. As soon as he’d walked out he could tell it wasn’t going to have any effect. The attitude of them … Christ. They hadn’t listened to a word he’d said. Just laughed at each other, whispering and turning their backs to him. He’d given up with a shrug of his shoulders and a hope that they wouldn’t be back anytime soon. That they’d find someone else to bother.

He’d been wrong.

The plan was supposed to change that.

Forty years he’d worked. Up and down ladders nine hours a day. Hard work, but going home to Nancy and the kids made it worthwhile. He’d met Nancy when he was getting into his mid-thirties, her fifteen years younger. The mother-in-law had hated him from the start. Taking her little girl away. They’d had the last laugh on that one. Happily married for almost fifty years. Three children, two of them boys. When they grew up and had their own, they would have some of the grandkids over for tea once a week. Then they grew up as well.

His only regret with the children was that they weren’t closer. Brothers and sisters should be there for each other, but there was always a distance between them.

It would have been okay though. Whiling away their later years together. They would’ve had little trips here and there. Bingo once a week at the social club. Visits to see the offspring.

The end of Nancy’s story began and finished with two boys, barely in their teens, wearing hooded tops and balaclavas. They’d grabbed her bag, but she’d held on. They’d found bruises up her wrists and arms where they’d tried to prise her hands off it. A broken nose, which the CCTV showed happened when the taller of the two delivered a straight fist to her face. She’d died weeks later, but even if they’d found the yobs who did it, they wouldn’t have been charged with murder. She’d died due to other complications, they’d told him.

He knew they were to blame though.

He checked outside again, looking through the curtains. Four of the little buggers. No older than sixteen or seventeen, he reckoned. He could feel the anger coursing through him, wishing he was a few years younger. Back in his army days he would have taken the four of them on and had them running home for their mothers. He wasn’t one of those old guys who believed everything was better back in the day, like the moaning gits at the pub, but he also couldn’t remember sitting outside someone’s house drinking cans of lager, shouting and swearing. Life moves on. Things change. Not always for the better.

The fireworks were the last straw.

It had been late. Gone midnight. Explosions ripped through the silence which had accompanied his sleep. Downstairs, the direction of the noise made no sense in his confused half-asleep state. Korea. It was sixty years ago, but the slightest thing could send him back. He wasn’t to know some little bastards had thought it would be funny to stick a few fireworks through his letter box. Sweat dripped from his forehead, down onto the wisps of grey hair on his chest. His chest. Constricting. Tight. Everything pulling inwards. Choking him. The phone was in reach, which probably saved him that night. Couple of days in the Royal. Told to take it easy for a few days, but he should be fine. Simon, his youngest son, had gone mad, wanting to protect his supposedly frail father. Called the police, but they couldn’t do anything without evidence. Said they’d look into it, but everyone knew what that meant.

A week later, the plan had begun to be formed.

The faces of war. The noise … explosions, gunshots, cries of anguish. The forgotten war is what they call Korea. He’d never forget it. Waking up silently screaming has that effect. It’d been a long time since he’d had the nightmares, but they had come back since the firework incident.

He wanted to get back at them. Not just that though. To show them the error of their ways.

Brazen as you like, sat on his wall, chucking their empties into the front garden Nancy used to spend hours tending to.

He lifted the phone. Dialled and said a few words.

He opened the front door and they didn’t even turn around. Reached his front gate and stepped onto the pavement next to where they were gathered. They started laughing amongst themselves as he tried to get their attention.

It happened faster than he’d expected. He gave them another chance, tried being cordial with them, asked them to move on, but they weren’t having any of it. He tried explaining about the garden. They responded by laughing. Like a pack of hyenas, spotting the easy prey. He could feel his heart racing – bang, bang, bang. Beating harder than it had done in years.

He wasn’t going to back down. Not this time. Things were different.

Two of them walked off behind him, sniggering under their black hoods as he held his hands out wide, palms to the darkened sky. He heard the distant sound of a car towards the end of his road and turned towards it. A shuffling sound to his left made him turn back.

Thunk.

The sound reverberated around his head. The clatter of tin on concrete brought him back to his senses, just as another beer can pinged off his head.

‘What the …’

The laughing had grown louder. Surrounding him, constricting his breathing.

‘You little shits …’

They were grouped together, pointing at him, nudging each other hard as their laughter grew and grew.

‘Come ’ead lads’, the tallest one said between fits of laughter, ‘let’s get down to Crocky Park. See if the girls are about.’

He stared after them as they left, mouth hanging open as they sauntered off, hands down the front of their tracksuit bottoms. Looked around at the mess they’d made of his garden and the pavement in front of his house, before reaching up to his head – damp where dregs of beer had splattered onto his hair.

The van parked up his street shifted into gear and coasted towards him. He felt as if his chest was stuck in a vice, his breathing becoming shallower. He staggered backwards and sat on the small brick wall.

He lifted his head up as the van came to a stop a little before his house, squinting into the bright lights on the front of it. The passenger side door opened and he looked at the figure which got out.

‘You okay auld fella?’

‘Fine,’ he replied between pants of breath, ‘the tall one. That’s who we want.’

‘You sure?’

The old man swallowed and made a go ahead motion with his hands. ‘It’s time, son. One isn’t enough. We’re going to teach them a lesson. We’re going to teach them all a lesson.’

Goldie felt buzzed – a bit light-headed even – but not properly pissed, which annoyed him. Even worse, that little slag Shelley hadn’t let him do anything more than have a feel of her tits before pushing him away. Not that there was much there to feel. Now all he wanted to do was get home, smoke a bit – just to zone him out, like – and then have a good kip.

He smiled to himself as he remembered the auld fella from earlier on in the night. Probably a fuckin’ paedo or something, so he didn’t feel bad. Not like there were any laws against sitting on someone’s wall anyway. Next few weeks, he planned on making sure that auld bastard realised who Goldie was.

Lost in his half-pissed thoughts, he didn’t hear the van slowing behind him. Didn’t hear it come to a stop, the side doors opening. The first he realised something was wrong was when he was pushed hard in the back, his balance not what it would have been earlier in the day. It happened so quickly, he couldn’t free his hands to stop the fall.

He remembered thinking the pavement was fuckin’ hard, smashing into his face with nothing to brace against it – harder than even his dad had hit him that one time, before he fucked off for good. He turned around on the floor, using his tongue to feel around his mouth. One of his front teeth jutted forwards into his top lip. His left eye was going blurry as something wet dripped down his face. Blood, he guessed.

He tried to regain his senses, determined not to go down without a fight. Probably some Strand fuckers, hoping to put him out of action. He turned onto his back, raising his hands to cover himself, waiting for the kicking to start.

He looked up, confused in an instant as he saw the men standing over him.

They were old. Forties, fifties. He could tell from the greying hair, rather than facial features. All of them wearing masks.

Shite …

‘You’re coming with us, kid. Gonna teach you some respect.’

Goldie began kicking out, but rough, hard hands grabbed at his legs. Strength he wasn’t used to from the other lads his own age. Fingers dug into his flesh as they pulled him along the concrete.

‘Get the fuck off me you fuckin’ twats. I’ll fuck you all up. Do you know who I am? I’m gonna fuckin’ kill all o’ yers.’

Then the world went black as something was forced over his head, pulled tight across his face, no amount of thrashing around making it come off. Hard metal slammed into his stomach, taking the wind out of him completely. He felt a weight on his legs as he realised he was now in the back of the van, hands holding his head to the floor as they began to move. The hood over his face was loosened a little so he could breathe.

‘Duct tape.’

The voice was hardened, Scouse. Proper old school, like his dad’s.

‘No. Don’t you fuckin’ dare …’ Goldie tried to shout, the hood muffling the sound.

The hood was lifted to his nose, before tape went across his mouth. Shouting behind it had no effect. He tried kicking out again, but the hands holding his legs and arms down barely shifted.

‘Stop messing about, or we’ll just dump you in the Mersey now. Relax. Nothing is going to happen to you. We’re going to help you.’

Goldie tried answering back, but it was useless.

One leg got free.

Goldie didn’t think twice. Just swung it back and aimed for anything he could. The satisfying clunk as his foot found flesh made him redouble his efforts.

Shouts, cries, as he struggled free, the hood over his face keeping him in darkness.

‘Stop the van.’

The same voice as before, still calm, still low.

Goldie tried to stand, but the van pulling to a stop made him rock forward, off balance.

‘I told you to relax.’

Goldie spun, but wasn’t quick enough. His hands caught in mid-air as he tried to remove his hood. Strong grip on his wrist. Starting to twist.

Explosion in the side of his head as something smacked against it.

Then, as he fell to the floor, he wished for the complete darkness of unconsciousness – not just the vision of it. As the punches landed, the kicks and boots flew into his stomach, his ribs cracking one by one.

That tight grip on his wrist. Still there. Twisting, turning.

He cried out behind the duct tape sealing his mouth. No use.

The crack as his wrist snapped.

‘That’s enough. All of you.’

The blows stopped as he lay on the floor of the van, trying to hold his body together. Coughing up God knows what behind his gag. Trying not to choke. Trying to breathe, every intake of air through his nostrils not enough.

It somehow got darker behind the hood as his head lolled backwards.

The last thing he remembered was the voice again.

‘Start it up. Let’s get to the farm. Now.’

PART ONE (#ulink_d116ea68-73cd-5c9e-bcaf-625ebb90d4a2)

Take the coward vermin to the nearest safari park. Shatter one of its knees. Hamstring the maimed leg, then kick the disease out of a van in the middle of the lion enclosure. No cat can resist a limping, bleeding thing. Film it and show it daily at prime time for a month. I’d pay good money to watch this show happen live. It wants to live like an animal? Let the subhuman abortion die like one.

I suppose when a judge says something is ‘wicked’ he presumes the accused will wilt under the ‘tirade’. They may see the ugly side of life, but they simply do not understand it. Well, something that cowardly piece of rubbish would understand is a rope – or better still, piano wire. So what is wrong with visiting upon him the horror that family have gone through, doubtless are going through? Come on PC crowd, how are you going to side with this one?

**** **** and his type are not human. They are far, far beneath human. They are parasites who cause nothing but misery for real humans. People like this should be sterilised so their poisonous DNA is knocked out of the gene pool. What is it about these nasty folk who just roam around being vile? What can they possibly contribute to society other than destruction and misery?

Top-rated online comments from news story of teenage murderer

1 (#ulink_66f5e5b1-ad77-5899-a2ce-1f3caf5bd61f)

More sleep. Just a little bit more …

Detective Inspector David Murphy hit the snooze button on the alarm for the third time, silencing the noise which had cut through his drift into deeper sleep once again. He refused to open his eyes, knowing the early morning light would pierce the curtains and give him an instant headache.

A voice came from beside him.

‘What time is it?’

He grunted in reply, already knowing he wasn’t going to float away into slumber now. A few late nights and early starts and he was struggling. Age catching up with him. Closing in on forty faster than he’d expected.

‘You need to get up. You’ll be late for work.’

Murphy yawned and turned over to face Sarah, away from the window. Risked opening one eye, the room still brighter than he’d guessed. ‘Do I have to?’

Sarah sat up, taking his half of the duvet cover with her and exposing his chest to the cold of the early morning.

‘Yes,’ she replied, shucking off the cover and pulling on her dressing gown. ‘Now get up and get dressed. There’s a fresh shirt and trousers in the wardrobe.’

‘Five more minutes.’

‘No, now. Stop acting like a teenager and get your arse in gear. I’ve got work as well, you know.’

‘Fine,’ Murphy replied, opening his other eye and squinting against the light. ‘But can you at least stick some coffee on before you start getting ready? I tried using that frigging maker thing yesterday and almost lobbed it through the window.’

‘Okay. But you have to read the instructions at some point.’

Murphy snorted and sloped through to the bathroom. Turned the shower on and lifted the toilet seat, the shower tuning out the noise from downstairs as Sarah fussed in the kitchen.

He needed a lie-in. Twelve or so hours of unbroken sleep – now that would be nice.

It wasn’t even work causing his tiredness. Nothing major had come through CID in the previous few months. Everyone at the station was trying to look busy so they weren’t moved to a busier division in Liverpool. All too scared to use the ‘Q---T’ word. It was just slow or calm. Never the ‘Q’ word. That was just an invitation for someone to shit on your doorstep. A few fraud cases, assaults in the city centre and the usual small-fry crap that was the day-to-day of their lives in North Liverpool. Nothing juicy.

Murphy buttoned up his shirt and opened the curtains to the early May morning. Rain. Not chucking it down, just the drizzle that served as a constant reminder you were in the north of England.

The peace in work was a good thing, he thought. Just over a year on from the case which had almost cost him his life, he should have been grateful for the tranquillity of boring cases and endless paperwork. At least he wasn’t lying at the bottom of a concrete staircase in a pitch-black cellar, a psychopath looming over him.

He had to look at the positives.

Murphy left the bedroom, stepping over paint-splattered sheets, paint tins and the stepladders which festooned the landing.

The cause of his late nights.

He’d gone into decorating overdrive, determined to have something to do in his spare time. Started with the dining room, which hadn’t seen a paintbrush since they’d bought the house a few years earlier. Now he was back living there, reunited with his wife after a year apart following his parents’ death, it was time to make the house look decent. Sarah was often busy in the evenings with lesson planning and marking due to her teaching commitments, so he would have otherwise just been staring at the TV, and he’d done enough of that when he lived on his own.

Sarah had started teaching just as they got married. Her past put behind her, a successful degree course, and a clean CRB check was all she needed. That, and a large amount of luck, given her ability to never actually be arrested for any of the stupid stuff she’d done in the past. Murphy had never expected that last bit to hold.

Murphy entered the kitchen just as Sarah was pouring out a cup of freshly brewed coffee. ‘Cheers, wife. Need this.’ He brushed her cheek with his lips as she slipped past him.

‘I’ve only got half an hour to get ready now, husband. Work out how to use the thing yourself, okay? Or we’re going back to Nescafé.’ She stopped at the doorway. ‘Oh, and remember you promised we’d go out tonight.’

Friday already. The week slipping past without him noticing. ‘Of course. I’ve booked a table.’

She stared at him for a few seconds, those blue eyes studying his expression. ‘No you haven’t. But you will do, right? Tear yourself away from your paintbrush, Michelangelo, and treat your wife.’

Murphy sighed and nodded. ‘No problem.’

‘Good. See you later. Love you.’

‘Love you too.’

They were almost normal.

The commute was shorter now than it had been in the months he’d lived over the water, on the Wirral – the tunnel which separated Liverpool from the small peninsula now a fading memory. Still, it took him over twenty minutes to reach the station from his house in the north of Liverpool, the traffic becoming thicker as he neared the roads which led into the city centre.

After parking the car in his now-designated space behind the station, Murphy entered the CID offices of Liverpool North station just after nine a.m., the office already bustling with people as he let the door close behind him.

Murphy sauntered over to his new office, mumbling a ‘morning’ and a ‘hey’ to a few constables along the way. Took down the note which had been attached to his door as he pushed it open.

Four desks in a space which probably could have afforded two. Their reward for months of complaining and reminding the bosses of the jobs they’d cleared in the past year. A space cleared for Murphy, his now semi-permanent partner DS Laura Rossi, and two Detective Constables who seemed to change weekly.

‘Morning, sir.’

Rossi looked and sounded, as always, as if she’d just stepped off a plane from some exotic country, fresh-faced and immaculate at first glance. It wasn’t until you looked more closely – and in a space as tight as their office, Murphy had been afforded the time to study her – and noticed the dark under her eyes, the bitten-down fingernails, and the annoying habit she had of never clipping her hair out of her face.

He said his good mornings and plonked himself down behind his small desk, checking his in-tray for messages. A few chase-ups on old cases, a DS from F Division in Liverpool South who wanted a call back ASAP. Routine stuff.

‘Anything new overnight?’

Rossi looked over from her computer screen, eyebrows raised at him. ‘Nothing for us.’

‘Come on. There must be something? I’m bored shitless here.’

As Rossi was about to answer, the door opened, DC Graham Harris sweating as he rushed in and sat down, shoving his bag under his desk. ‘Sorry I’m late. Traffic was murder near the tunnel.’

Murphy debated whether to give him a telling-off just to kill a bit of time, before deciding against it. He yawned instead, waving away his apology with one hand. ‘Where’s the other one?’

‘Not sure,’ Harris replied, removing his black Superdry jacket. Murphy had priced one of those up in town a few weekends previously. Decided a hundred quid plus could be put to better use.

‘Doesn’t matter. Not like I’ve got anything for him to do.’

‘Still quiet then?’

Rossi winced and turned in her chair, almost knocking over the single plant they had in the office. ‘What did you say?’

Murphy leant back in his chair, smirking as he watched the young DC as he realised his mistake.

‘Er … nothing. I mean … nothing new?’

Rossi moved towards Harris, ‘You said the fucking Q word, che cazzo?Say it again, I dare you. Cagacazzo.’

‘What? I don’t … I didn’t mean …’

Murphy sat forward, palms out. ‘Calm down, it’s just a stupid superstition. No reason to start anything, okay?’

Rossi turned towards him, her features relaxing as she saw his face. ‘Va bene. It’s okay.’ She sat back in her chair and went back to her computer screen.

Murphy worried that Rossi calling a DC a dickhead in Italian was going to be the height of excitement for the day.

He needn’t have.

A few minutes later the other DC who was sharing the office with them came bursting through the door. New guy, just transferred. Murphy had enough problems remembering the names of those who’d been there years, without new ones being thrown into the mix.

‘We’re on. Body found in suspicious circumstances outside the church in West Derby.’

Murphy jumped up out of his seat at about the exact moment Rossi turned on Harris.

‘What did I tell you? You had to say the word, didn’t you. Brutto figlio di puttana bastardo.’

Murphy knew Harris had understood only one of the words Rossi had spat at him as she grabbed her black jacket from behind her chair. ‘Knock it off, Laura.’

Rossi muttered under her breath in reply to him. He had to hold back a laugh. ‘Come on. Let’s just get down there. You know how these things can turn out. It’s probably nothing.’

Which was perhaps a worse thing to say than the Q word.

2 (#ulink_08bf5cf2-5d60-5d88-8c94-425cc81ec3d9)

Dead bodies. Decayed or fresh. Crawling with maggots, flies buzzing around your face as you examine them in light or darkness. Or, a serenity surrounding them, framed in a pale light as if time has come to a stop for them. There’s no tangible difference, really. They’re all the same, each with their own tale to tell, how the end has come.

It doesn’t matter how many times you see one, it never gets easier. Not in reality. You can kid yourself; pretend that you’re immune to it, that it doesn’t affect you any more. That’s all it is though – a pretence, a deception. A way of getting through it.

There was a simple answer in Murphy’s opinion. Seeing death makes you contemplate your own … and most people spend their lives actively trying to avoid their own death. Even those risk-takers jumping off cliffs with a tea towel as a parachute are only giving themselves the thrill of cheating death. They’d leave the tea towel behind if they really wanted to die.

Once the initial shock kicks in, an unconscious mental process clicks into place and professionalism takes over. Makes you forget about what it is you’re dealing with. That’s the way Murphy thought of it. He imagined a shutter going down in one part of his mind, thoughts and feelings closed away and a detachment appearing.

The only time it took a bit longer for that process to occur was when they were below a certain age.

This one was on the cusp.

West Derby is a small town just past Anfield, around fifteen minutes from the city centre. Only a few minutes away from the more infamous estates of Norris Green and Croxteth, it was also the home of Alder Hey Hospital and Liverpool F.C.’s training ground, Melwood.

Now it would gain its own little piece of notoriety.

Murphy stood in the gravel entrance to St Mary’s Church in West Derby – Croxteth Park off in the distance – having arrived a few minutes before the forensic team and pathologist, by some miracle. On the steps leading into the church lay what they’d been called for. A young white boy, or maybe a man. He could never tell age these days. Laid on his side, one arm tucked beneath him, the other draped across himself. Eyes closed over a destroyed face. A mask of smeared blood – an attempt to wash it off, perhaps? – which did little to deflate the impact. Open wounds on the cheeks, skin splitting on numerous areas. Red flesh on show above his mouth, his nose misshapen and swollen. Eyes puffed up under the swelling. A faded scar just below his eyebrow was noticeable only as it seemed to be the lone part of his face that was untouched. The grey-silver of healed skin stark against the surrounding reds, browns and blacks.

Rossi finished talking to a uniformed constable and walked back towards Murphy. ‘Well?’ he said as she reached him.

‘Two twelve-year-old lads found him. They were walking through the park to school and spotted him. Thought it was a tramp at first, but looking closer they saw his face and realised he wasn’t breathing. They pegged it, right into the vicar, or whatever they call them, who was arriving for the day. He was the one who called it in.’

‘They notice anything?’

‘They’re a bit shaken up, but adamant they didn’t see anything else. They walk past here every day apparently.’

Murphy finished snapping on a pair of latex gloves, his faded black shoes similarly covered, and bent down to look at the body closer up, wincing as he looked at the victim’s face.

‘How old do you reckon?’ Rossi said from above him.

‘Not sure. Can’t really tell with these kinds of injuries to his face. All these kids look much older than we ever did at that age.’

‘That’s probably just us getting old.’

Murphy grunted in reply and went back to studying the face of the male lying prostrate on the ground. A thick band of purplish red around his neck drew his attention.

‘Fiver says it’s strangulation.’

‘I’m not betting on cause of death, sir.’

Shuffling shoes and shouted orders interrupted Murphy before he could respond. He looked up, trying to effect a look of innocence as Dr Stuart Houghton, the lead pathologist in the city of Liverpool, bounded over. The doctor had grown even larger in the past year, meaning he moved slowly enough for Murphy to pull away from the body before Houghton arrived on the scene.

‘You touched anything?’

‘Morning to you an’ all, Doctor,’ Murphy said, avoiding meeting the doctor’s eyes.

‘Yeah, yeah. What have we got here?’

‘I thought you could tell me that.’

A large intake of breath as Houghton got to his haunches. ‘We’ll see.’ He snapped his own pair of gloves on and began examining the body.

‘How long?’ Murphy said after watching Houghton work for a minute or three.

‘Rigour is only just beginning to fade. At least twelve hours, I’d say. Body has been moved here.’ Houghton lifted the man-boy’s eyelids, revealing milky coffee eyes staring past him, the whites surrounding them speckled with burst blood vessels. A thin, cloudy film pasted across them.

Murphy stepped to the side as Houghton’s assistant finished erecting the white tent around him. ‘Anything on him?’

Houghton finished fishing around the pockets of the black joggers which the victim was wearing. ‘Nothing at all. Was expecting a psalm or bible quote or something, given where we are.’

Murphy shrugged. ‘Could be nothing religious about it. Something we’ll be looking into, obviously.’ A religious nut or someone with a grudge to bear against the church. Murphy didn’t like the thought of either.

‘He’s been laid here on purpose, in this manner. Almost looks peaceful, just curled up. Like he just came here, lay down and went peacefully. As always, first glance is deceiving. Looks like he was strangled with some kind of ligature. Not before he was quite severely beaten.’ Houghton paused, rolling the torn T-shirt up over the victim’s flat teenaged stomach. Wisps of fine hair tracing a line towards a recessed belly button, barely visible behind angry red markings turning purple and black. ‘Bruises to his abdomen. Some old, some new. This boy was beaten severely before death. I’m guessing four … no, five broken ribs. Pretty sure there’ll be more broken bones to find as well. Also, there’s his face of course.’

‘This has been going on a while then. The older bruises, I mean.’

‘Could be. I’ll have more answers after the PM of course.’

Murphy nodded before beckoning over a forensics tech from the Evidence Recovery Unit – ERU – towards him. ‘Prioritise this one, Doc. The media will be all over us before we know it. Dead teen in suspicious circumstances and outside a church, with these injuries? Easy headlines.’

Houghton sighed at him in response, but before he could give a fuller answer Murphy moved away to meet the ERU tech – a white-suited woman with only her deep green eyes on display before she removed the mask covering the bottom half of her face.

‘Yes?’

‘I want a fingertip search of the whole area of the church. Inside and out. Pathways which run alongside it as well. I’ll see how far we can cordon the place off.’

‘We know the drill. Just make sure none of your uniforms get in the way.’

Murphy attempted a smile, which obviously looked more sardonic than he’d meant, judging by her reaction – a roll of the eyes and a turn away. He was always making friends.

‘Laura?’ Murphy called, Rossi lifting a finger which told him he was to wait whilst she finished talking to Houghton. She’d always got on well with the doctor, annoying Murphy no end. He still wasn’t exactly sure what he’d done in the past to piss off the old bastard, but was now so used to it he wasn’t sure he was all that arsed.

Rossi eventually finished her conversation a few seconds later, straightening up and strolling over to him.

‘What do you want to do first?’

Murphy finished removing the latex gloves, walking away as he did so. Rossi followed him. ‘Interview the priest, vicar, whatever he’s called, first. Then the kids who found the victim. Tell the uniforms to take them back to the station. Inform the parents, get social services to meet us. They might need counselling or whatever.’

‘Okay. Anything else?’

‘Door to doors,’ Murphy replied, looking up towards the main road at the bottom of the gravel drive which led to the church. ‘Although there aren’t that many in the immediate vicinity.’

‘There’s more houses on the other side of the church; Meadow Lane leading into Castlesite Road. Close enough. There’s some flats above the shops on the main road as well.’

‘Okay, good. Make sure the uniforms know this is a murder investigation. I don’t want them thinking it’s just some scally who got in a fight.’

‘Sir?’

‘Call it a gut reaction, Laura. Some of those bruises are old, fading. Signs of abuse. Something’s not right.’

Rossi nodded slowly, writing down the last bit of info in her notebook before looking back at him. ‘That it?’

‘Yeah. I’ll see if the vicar can accommodate us.’

The Farm (#ulink_a544666c-f6d0-5f97-b49a-4b89feac8065)

Six Months Ago (#ulink_a544666c-f6d0-5f97-b49a-4b89feac8065)

Goldie was alive, there was that at least. When he’d first been grabbed off the street, beaten until he could barely breathe without feeling the pain all over his body, he’d felt for sure that was it. That he’d pissed off the wrong person once too often and was now going to pay the price. He’d heard stories about the gangsters out there in the city and what they could do to you if they wanted.

He was expecting the end. Tried to work out which dealer he hadn’t paid properly or what he’d promised that he hadn’t delivered, but couldn’t think of a thing.

When he was dragged along the muddy track outside, a sawn-off shotgun pointed at his chest the whole way, Goldie was thinking about all the things he was about to lose.

It amounted to very little.

There was his family, he guessed. What was left of it, anyway. One brother locked up, doing at least fifteen years for manslaughter. Hadn’t seen his dad in years – didn’t much care.

Now there was just him and his mum. And whoever she was seeing at the time, of course.

That was all gone. All he had now was the large room they’d shoved him in, the darkness within masking its real form. He ached from the ride in the back of the van and the beating inside. His breathing was shallow, as the adrenaline he’d been feeling earlier began to wane and he became used to sucking in full lungfuls of oxygen again.

That’s the thing they never showed you on TV. When your mouth is gagged, you have to breathe through your nose. Goldie’s had been broken a few years before that night, which had left it resembling one of those shit paintings he’d seen in art, by the bloke with one ear or something. Or that other one. Art wasn’t exactly his strongest subject. That earlier injury had left his nose skew-whiff, at an angle. Bone blocking one nostril, so breathing with his mouth closed became difficult after a while.

He waited a few minutes, just kneeling down in the dark, breathing in and out. Wondering why they’d left him there.

‘Hello?’

The voice came from across the room as a whisper, shitting Goldie up big time. He scrabbled back, only being stopped by the solid wall behind him and the pain that resulted from hitting it.

‘Who’s there?’

The voice was a little louder now, more hiss than whisper. Goldie sensed something behind it.

Fear.

He felt the same way.

Goldie stood up, his eyes still adjusting to the pitch black, and began slowly feeling his way forwards. Arms out in front of him, sweeping his legs back and forth.

‘I’m Goldie, mate. Where are you?’

‘Over by my bed.’

Goldie stopped as he heard the reply come from a couple of feet away from him to his left. His eyes were adjusting now, the shape and form of things becoming clearer. He could make out a bed, two in fact, on his left. Mirrored to his right. That was it though. No other furniture.

He could smell piss coming from further away.

‘What’s your name?’ Goldie said, coming to a stop at the bed opposite.

‘Dean. Just got here?’

Goldie nodded, before thinking better of it. ‘Yeah. What’s going on? Why do you keep fuckin’ whispering?’

There was a creak from the bed as Dean moved, Goldie imagined rather than saw.

‘Because they’re out there, listening all the time. You don’t want them to get mad. Believe me.’

Goldie barked a laugh. ‘You’re paranoid, lad.’

He wouldn’t find it funny after a while.

Things were calm for the first few days. They’d drop meals off for the two of them. Dean told him he’d been there for a few weeks at least. Two men had taken him, he thought. He wasn’t sure, as it’d happened fast and he’d been a bit stoned.

Goldie didn’t believe the things he said had been done to him since then.

Light got into the room during the day. Not enough to be comfortable, but at least they could move about without worrying they’d bang into something in the darkness.

Boredom was the problem in the beginning. Goldie decided to fill his time trying to find a way out of there, examining every part of the room.

By the third day he’d given up. There was nothing to find. Every inch was solid, reinforced.

The only way out was through the door which he’d come in.

He began watching them as they dropped off meals. Food in sealed packaging. None of the stuff he was used to eating, proper horrible stuff like tasteless rice and salad. He would have thrown it back, but he was starving after the first day.

Every time they came inside was the same. The door would be unlocked, more than one lock on the outside, Goldie noted, the door swinging open, light rushing in. The eight times it had happened, there’d never been less than three of them. Two of them had either a sawn-off or a bigger gun, like you’d use on Call of Duty. Assault rifle, Goldie reckoned. He’d told Dean that, but not really got anything in response.

‘Dean,’ Goldie had said on day four, whilst they were eating a meal of some kind of mashed potato and meat, ‘we should rush them when they drop the food off.’

‘No …’

‘Hear me out, lad. We could get either side of the door and surprise them. Have them over and then get the fuck out of here.’

‘It won’t work. And then you’d have to go on the rack. Trust me, you don’t want to go on that.’

‘What’s the rack?’ Goldie said, his brow furrowing.

‘You don’t wanna know …’

‘Pretend I do,’ Goldie replied, an edge to his voice. The look on Dean’s face made him pause though. The lad had started sweating, his hands shaking a little … then more.

‘I … I … No. They told me not to say anything.’

‘Like I give a shi—’

‘No,’ Dean’s voice echoed around the room. ‘I’m not saying nothing.’

Goldie considered pushing harder, but Dean was now sitting on the bed, knees drawn up to his chest with his arms wrapped around them, silently rocking. Whispering to himself words which Goldie couldn’t hear.

Goldie recognised what just thinking about the rack had caused in Dean.

Terror.

Day five was when it started. Three of them arrived, with Goldie expecting the same process as before. Food dropped off, no questions answered. Any movement met with a point of a weapon.

It was different this time though. No food. Two of them came towards him as the other aimed a rifle at his chest. Strong hands gripped each of his arms and pulled him along.

Helplessness. That’s the effect a bullet can have on you. It wasn’t the gun so much. Not after he’d got used to it being pointed at him. All he could think about was what it contained. Tiny little things that would rip him apart. Kill him in a second.

They led him out of the building he’d begun to get used to, out into the cold winter air of December. He could see his breath as he exhaled, hoping that would continue as the memory of his mouth being gagged came back to him.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked, chancing it. Not wanting to talk too much.

There was no response. Goldie measured himself up against the two people in balaclavas holding onto his arms, deciding he could probably take them if needs be.

If he could work out a way of doing it before being hit by a bullet, he’d do it. He didn’t want to turn into Dean back in the room. Scared for his life. Not yet.

He was led back inside another building, a large desk in a room, someone in a black balaclava and a suit sitting behind one side. It wasn’t so much a desk, Goldie thought as he was dumped onto the chair opposite the man, as a long table. A red cloth covered the surface, barely hanging over the edges.

Goldie stared across at the balaclava-suit man, not willing to break eye contact. Two of those who had brought him here left the room, leaving only rifle man and the weird get-up sitting across from him. There was something so odd about the combination of a bally and a pristine suit, which Goldie could tell was no Burton’s Menswear special. Nah, this was money. Made to measure, he thought.

‘Nice suit. Wanna tell me what the fuck you think you’re doing?’

His voice sounded exactly as he wanted it to. Hard as fuck. Don’t-fuck-me-about hard.

‘Be quiet. Learn to speak when spoken to, understand?’

Goldie forgot about the gun being pointed at him for a second. ‘Fuck off. Don’t talk at me like that.’

He heard, rather than saw, the whipcrack as Bally-Suit man raised and struck his face with something. A few seconds of nothing, before the pain cut in.

Stinging, burning. His face on fire, from ear to nose in an almost straight line. Goldie pulled his hand away from his cheek where it’d flown in reaction, looking at it as if it wasn’t his. Blood, thin lines of red. Broken skin, broken face.

Burning.

‘This is something my dad gave me. He no longer had any need to use it, so passed it down. I only ever got it once, that was enough. I deserved it then as well.’ Bally-Suit man was standing now, his accent softening as he spoke. ‘It’s like a riding whip, what you’d see a jockey using. Only this is worse. Thinner, more pliable.’

Bally-Suit man moved around the table-desk and came close to Goldie as he held his face with one hand, trying to decide if punching this dick now or later would be preferable.

‘You’re going to learn some manners, young man. And learn them quick.’

Goldie took his hand away from where he’d been stroking the burning, turning to face Bally-Suit man. ‘Fuck you,’ he spat.

Bally-Suit man sighed through the covering and shook his head at him.

The crack came again, quicker than Goldie could react. Across the other side of his face. As he went backwards, away from the pain, Bally-Suit man kicked at his chair, sending him flying. Goldie’s head cracked against the floor, making him dizzy for a second or three before his senses returned, his fists balling and swinging.

Laughter rang back at him as he punched thin air, then pain flared across his thighs as the crack hit there. Then all the wind rushed out of him as a boot flew into his stomach. He tried to get up, one arm across his middle, but a boot on his neck stopped him.

‘Stay down. I don’t want to have to put you on the rack first day.’

Goldie glanced towards the table-desk as the cloth fell from it, revealing something he couldn’t work out. Restraints and wood. In any other setting it would have barely caused a second glance. Seeing it there, Goldie began to breathe quicker, trying to swallow.

Goldie shook his head clear, tried moving again. ‘Am I fuck lying down for you,’ he said, pushing away the boot from his neck.

His voice wasn’t as good as before. The hardness was already going, leaving him, getting the fuck out of there while it still could. If he wasn’t alone, maybe it would have been different; with his boys backing him up, things wouldn’t be the same at all. As it was, Goldie was on his own, and the prick in the bally-suit was standing over him with some whip type of thing that was causing him a lot of pain and he couldn’t even see it coming.

‘You don’t understand, do you?’

‘Understand what?’ Goldie said, pulling himself onto all fours as the man backed away from him.

‘You’re under our control now. You’ll do as we say, or there will be consequences.’

Goldie spat out a long drool of saliva onto the floor, eyes widening as he saw the redness of fresh blood mixed in with it. ‘You going to kill me, is that it? What for? I ain’t done nothing to you.’

Bally-Suit man laughed at him. ‘Course you have. You and all your mates. Everyone like you. Young boys with big mouths.’

A boot flew into Goldie’s stomach, flipping him over onto his back and making him cry out in pain before his breath caught.

‘You’re disrespectful, arrogant and nothing but a stain on this city,’ Bally-Suit man said, standing over him. ‘Well, that’s going to start changing. You’re going to start changing. Starting now.’

Goldie closed his eyes to the pain which was beginning to kick in from the beating, as Bally-Suit man crouched down and leant closer.

‘And if we’re not happy with your progress, well … let’s just say you’ll be begging for a little roughing-up like I’ve just given you. I have many ways of making you accept change.’

Goldie opened his eyes, but the man was no longer there. Just the two in balaclavas holding guns as before.

He got up with some help, and allowed himself to be led back to what he would soon call the Dorm.

And hoped it wouldn’t be the last place he could call home.

3 (#ulink_550ca293-f827-576e-8a61-aa954330f88e)

Reverend. Not vicar or priest. The Church of England always confused Murphy. Catholic guilt was much more his forte, forever cursed to carry that around with him. Sister Margaret Mary rapping your knuckles for getting a line wrong in the Stations of the Cross, or a proper beating for anything closely resembling impure thoughts. Every bloke Murphy’s age who had grown up Catholic had the same stories. Thankfully, his parents had grown out of religion before too long. C of E always struck Murphy as more tea and biscuits than the hell and eternal damnation his own church had taught him.

Reverend Andrew Pearson. Wild haired, with a grey, bushy beard and bright blue eyes which seemed to dart in every direction at once. Murphy imagined he was usually much more expressive, but today he was sombre, one hand clasped over the other in his lap as if to restrain himself from making any sudden gestures. With the interior of the church currently out of bounds whilst it was searched for evidence, they had convened in one of the marked police vans which were now at the scene – Murphy and Rossi sitting on one side, facing the reverend.

‘Sorry about the less-than-comfortable surroundings, Reverend,’ Murphy said, already feeling the strain of sitting in a confined space. Being six foot four had its drawbacks. ‘Hopefully this won’t take too long.’

‘Not a problem,’ the reverend replied. Murphy noticed the accent wasn’t local. From outside the city, he guessed.

‘I’m Detective Inspector David Murphy and this is Detective Sergeant Laura Rossi. We just want to ask a few questions about what happened this morning. Okay?’

‘Of course. But I did tell the other officers I don’t know all that much. Just the boys running towards me, looking like they’d had the shock of their young lives. I guess they probably had.’

‘I see. What time was this?’

‘Around half eight. Bit later than I usually arrive to the church, but I was delayed this morning. A few phone calls I had to make regarding an upcoming event. If I’d been on time, those poor boys wouldn’t have had to go through the shock.’

Murphy stretched his legs out slowly. ‘Do you live close by?’

‘Yes, the vicarage is only around the corner.’

‘And you weren’t disturbed overnight? Anything you can remember at all?’

The reverend shook his head. ‘I’m afraid not. I went to bed around eleven and slept through until seven. Didn’t hear a sound.’

‘Did you recognise the victim?’ Rossi said after a few seconds of silence.

‘No. We don’t see many teenagers in the congregation, I’m afraid. Especially males. We have a choir, with a healthy number of boys, but once they reach eleven, twelve, thirteen, they seem to find much more interesting things to be doing. We try our best of course, but there’s too much pressure from outside.’

‘I guess,’ Rossi replied, writing in her notebook. ‘Did you enter the church after finding the victim?’

‘Only to use the phone in the office.’

‘Anything out of place?’

The reverend made a show of thinking for a few seconds before answering. ‘Nothing I can think of. It was still locked up and there wasn’t anything obvious to indicate anyone had been in there. I imagine your people will be able to tell if that’s the case or not.’

Murphy nodded, thinking the fingertip search he’d ordered of inside the church might prove to be a waste of time. ‘Better to be safe than sorry.’

‘How long do you think this will take, Inspector? Only we’re supposed to have midweek services this evening.’

Murphy raised an eyebrow at Rossi before turning back to the reverend. ‘Forgive the bluntness, Reverend, but as long as it takes. At the moment, the church is a crime scene, and the most important thing is ensuring that we gather all the evidence we need.’

Reverend Pearson brought his index fingers together and bounced them off his chin, nodding slightly at the answer. ‘Of course. I’m sure the congregation will understand.’

‘Thank you. We’ll keep you up to date with what is happening.’

‘I appreciate that,’ Reverend Pearson replied, bringing his palms down and smacking them onto his knees. ‘I will be praying for the young man and your investigation.’

Murphy shot Rossi a look as she choked back what he hoped sounded like a cough to the reverend, rather than the laugh he knew it was. ‘Yeah, thanks for that. We appreciate any help we receive.’ He took a card from his wallet and handed it over. ‘Just in case you have any further questions.’

‘Not religious then, Laura?’

Murphy was leading them back to where the victim’s body was in the process of being bagged up to be taken to the morgue for the post-mortem. The mood amongst the various technical officers and uniforms was more solemn than usual. Murphy guessed it was the setting, rather than the dead body.

‘Not in the slightest. All a load of rubbish, isn’t it? Cazzata,’Rossi replied, tying her hair back as she spoke.

‘Thought all Italians were religious?’

‘Probably more so back in the old country, but once they were outside – over here – my parents never bothered. Much to my nonna’s delight of course.’

Murphy snorted. ‘Well, let’s hope this isn’t a religious thing then. Can’t imagine you’d be much use.’

Rossi stopped, placing a hand on Murphy’s arm. The height difference meant she was almost at his wrist, when she was probably aiming for a bicep. ‘No, don’t get me wrong. I might not be religious, but I know my stuff. Religion is fascinating. Especially sociologically speaking. I just don’t believe in the magic man in the sky bit.’

Murphy looked down at her and smiled thinly at the echo of his own thoughts. ‘Probably best to keep your voice down a bit. You’re standing on hallowed ground here,’ he said, motioning towards the church before walking on.

‘Yeah … I’m about to get struck down by God’s wrath any second now,’ Rossi muttered under her breath, just about loud enough for him to hear. He bit on his lip in order to stifle the laughter.

‘You’re not, are you?’ Rossi said, as she caught up with him. ‘Don’t mean to offend, if you are …’

Murphy shook his head. ‘No. Not really. It’d be nice, I suppose, but I think I’ve been doing this too long to believe.’

Rossi looked away, nodding. ‘Anyway,’ she said finally, ‘what next … the kids?’

‘Yes. Have they been taken to the station?’

Rossi looked around and beckoned someone in uniform over. ‘I’ll just check.’

Murphy left her to it, turning to watch as the tent cover surrounding the body was pulled back and the trolley which would transport it to either a van or ambulance was taken closer to the scene. The victim was now completely covered in black for its first step in the journey of a murder investigation.

Well, almost its first step. What happened to the boy before it had arrived here was the beginning, really.

‘The lads are at the station. Parents are meeting us there,’ Rossi said, appearing at his side. ‘But, more importantly, we’ve got a name for the victim.’

‘That was quick,’ Murphy replied. ‘Thought they didn’t find anything on the body?’

Rossi shook her head, grinning slightly. ‘Didn’t need to. A uniform recognised him. Reckons he’s had a few dealings with him in the past.’ She pointed to an officer who was sitting on the small outer wall on the perimeter of the church. ‘PC Michael Hale.’

‘I’ve seen him before somewhere,’ Murphy said, walking towards PC Hale, Rossi in step next to him.

‘Same here. Can’t place him though. Probably some other scene.’

‘Hmmm. Possibly.’

They reached the PC, who broke off from speaking to another officer to greet them

‘Sorry about that,’ PC Hale said, once the officer had left.

‘It’s no problem,’ Murphy said, looking Hale up and down. ‘I’ve been told you know the victim?’

‘Yeah,’ PC Hale said, stroking a leather-gloved hand over his face. Three-day stubble, intentionally shaped and clipped. ‘Had the pleasure of his company over the years. If you know what I mean …’

Murphy waited, the silence growing between the three of them until Rossi filled it.

‘Well? What are you waiting for?’

‘Oh, sorry. His name is Dean Hughes. Lives over in Norris Green. Part of the crew there. Always in trouble for something or other. Those gangs are the bane of our lives – in uniform, you know. One of the reasons I’m trying to move over to work with you guys.’

‘Right,’ Murphy said, trying to decide on his first impression and finding it wasn’t good. ‘And you can tell, even with what’s happened to his face?’

PC Hale nodded. ‘I’ve seen him at his worst, after fights and that. It’s definitely him.’

‘So, how old is he?’

‘Think he’s eighteen now. Not sure. Haven’t seen him around for a while, so thought he’d either been banged up without me knowing, or got some girl pregnant and was trying to go straight. Never happens though.’

‘What doesn’t?’

‘Going straight. Those types … they’re always up to something. Can’t help themselves. Doing normal stuff just doesn’t come natural. Waking up early, going to work, doing an honest job … they can’t handle it. Rather sit at home on their arses and go on the rob at night. Looks like someone might have done us a favour here, if you ask me.’

Murphy knew the sort PC Hale was referring to – even had some sympathy for the bitterness which had crept into Hale from years of dealing with this type – but he still decided his first impression was right. Hale was a prick. ‘Is that what your dealings with Dean were mainly about … robbing, that sort of thing?’ Murphy said, aware of Rossi bridling beside him.

‘All sorts, really. Street robbery, violence, drink, drugs …’

‘Drugs?’ Rossi interjected, just as Murphy was taking a breath.

‘Yeah, only a bit of weed and that. Nothing major. I’m sure you’ll see his record soon enough, but I imagine it wasn’t just me who was picking him up most weekends. Proper little scrote. Used to take him home to his mum and she’d be just as bad. More pissed off with us than the little shit we’d took home for her. The state of that house as well … Jesus. Five kids, probably five different dads, I reckon. None sticking around for more than the two minutes it took to get her up the duff. You know the type. What do these people expect if that’s how they’re brought up?’

Murphy couldn’t help but glower at Hale a little. ‘Well thanks for the speech, PC Hale. Good to know a bit of background about the victim … you know, the dead teenager?’

Hale focussed past Murphy and Rossi at the church behind them. Murphy followed his gaze. ‘Yeah,’ Hale said eventually, ‘no problem.’

‘Let’s go,’ Rossi said, pulling once on Murphy’s arm before walking away. ‘I can’t hear any more merda right now.’

Murphy said goodbye for both of them and turned towards the church entrance where they’d parked up earlier, and walked quickly to catch up to Rossi. Heard PC Hale ask a fellow uniformed officer what merda might mean, and smiled in spite of himself.

‘You sorted here?’ Murphy said, as he reached his car – Rossi leaning against the passenger door, waiting.

‘Of course.’

‘Let’s get back then. See what these kids have to say and then make plans.’

4 (#ulink_63bff748-c9fb-5489-899e-9c701d3d0005)

The car journey back to the station was silent, broken only with long sighs from Rossi who sat beside Murphy. The four miles back to the city centre should have taken fifteen minutes but was taking much longer due to traffic going back into town.

‘Okay. I give in,’ Murphy said, as they stopped at yet another set of traffic lights. ‘What’s up with you today?’

Another sigh. ‘Nothing.’

‘I know that means something. Come on, open up. You’ve been in a frigging foul mood all morning. I haven’t heard this much swearing in a foreign language since I last went to an away match in Europe.’

‘Just family stuff.’

Ah, Murphy thought, should have guessed. ‘Which is it this time … job, love life?’

‘The second one, nicely tied with the first this time around. Wanting to know why I haven’t settled down yet. They’ve started blaming the job.’

‘Surely you’re used to it by now?’

Rossi examined a nail and started biting it. ‘You’d think, but no. Anyway, it doesn’t matter.’

Murphy sneaked a glance, seeing Rossi with another finger in her mouth. ‘I’m sure they’ll ease off a bit eventually. But I bet it doesn’t help that all your brothers are settling down now.’

‘Not all of them. Vincenzo still refuses to move in with that girl he got pregnant. And I’m pretty certain Sonny is seeing someone behind his wife’s back. Apart from that though, they’re all diamonds in my ma’s eyes. Just me who’s the disappointment.’

Murphy opened his mouth to answer, but Rossi cut him off.

‘Never mind. I can’t be arsed talking about it. Let’s forget it. I’ll try and be a bit nicer.’

A car beeped behind them as the traffic picked up pace ahead. Murphy released the handbrake again, beating the traffic lights this time and finally picking up some speed down the West Derby Road. Housing estates on one side of the A road, an endless array of shops on the opposite. Betting shops, Greggs, takeaways and those new clothes places he’d suddenly seen popping up everywhere a couple of years back. Sell your old clothes for sixty pence a kilo. Minutes up the road from the middle-class suburbs in the outskirts of the city and the differences could be seen everywhere.

Murphy didn’t like to ponder too much on the endless paradoxes of his home city. Enough to send anyone mad. How could the well-off and the poor be so close together? It didn’t make any kind of sense to him. He just assumed it was the same all over the country – probably more so in these post-recession times – and tried to get on with his life.

‘What’s the plan then?’ Rossi said, interrupting his thoughts.

‘Confirm the ID of the victim, interview the kids who found him, then go from there,’ Murphy replied, spying the Radio City tower in the distance – the signal that he was almost in town and would be at the station before long. ‘You know, the usual.’

‘I almost hope we’re done by the end of the day. I know we’ve not been busy, but I could do without a murder investigation.’

‘Couldn’t we all,’ Murphy replied.

‘Just let me know if it starts getting to you. We haven’t had one since … well, you know.’

Murphy didn’t answer straight away, but his thoughts instantly went back to the scene at his parents’ house two years ago. The violence inflicted on them, the death. It was always there, just on the surface of his memory, the slightest trigger bringing it forth again. Breath going shallow as he fought to keep the emotions down, determined not to slip into the same situation he had found himself in the year before. Lead detective on the biggest murder case his division had seen in years – a serial killer at that – but he’d been toyed with and manipulated. Mentally and physically.

‘Sir … you still with me?’

Murphy blinked back the images and looked out the windscreen towards the slowing traffic in front of him.

‘Yeah … I’m fine. Just … doesn’t take much, Laura.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Don’t be. I’m sound. This is nothing like the last one.’

And it wasn’t. Not yet.

Murphy held his phone in one hand, comparing it to the photo which was staring back at him from the computer screen. ‘I can’t really tell,’ he said, squinting and moving the phone around to try and see better, ‘this phone keeps going dark.’

Rossi leant across the desk. ‘Give it here, will you.’

Murphy allowed her to snatch the phone out of his hands. One day he’d learn how these things worked, but for now he was happy to let others do it for him. ‘All right, you do it then.’

‘See,’ Rossi said, flashing the phone in his face before going back to studying it again, ‘here’s your problem. You’ve turned off autorotate. And you have to keep your finger on the screen to keep it backlit.’

A lot of words which meant pretty much fuck all to Murphy. ‘Of course,’ he replied.

‘What do you reckon?’

Murphy nodded. Rossi had managed to enlarge the photo of the victim, which had been sent to his mobile a few minutes earlier, so that it fit the screen. ‘Obviously can’t be sure, but certainly looks like him.’

A photo of Dean Hughes filled his computer monitor. A mugshot taken during his last arrest. ‘This is eight months old, but I’m almost sure it’s him. Look at the scar above the eyebrow.’

‘Yeah,’ Rossi replied, leaning over him to look closer, ‘looks like it to me.’

Murphy began reading the information which was attached. ‘Arrested and then cautioned for Section Five. Hughes was “drunk and aggressive – believed all cofppers to be complete ‘twats.’” Sounds delightful.’

‘How many arrests are there?’

Murphy scrolled down the list. ‘Jesus … at least twenty. That’s just page one. That guy Hale was right. He was used to dealing with us.’

‘When was the last time we had any contact with him there?’

Murphy frowned as he went back over the record. ‘Odd. Seems like he was in trouble quite regularly up until seven months ago. Then … nothing.’

‘Weird. Was he banged up?’

Murphy checked further. ‘No. Nothing about that. No court appearances scheduled or anything.’

Rossi tapped a pen against her teeth, far too close to Murphy’s ears for comfort. ‘What’s his address?’

‘Clanfield Road. Norris Green.’

‘Check to see if there’s anything else.’

Murphy clicked through to the HOLMES database. HOLMES 2 as it was officially called, after an upgrade during the nineties, stored information on a variety of features, most of which Murphy never had time for. Case management, material disclosure … it was really just a dumping ground for every piece of information anyone working in the police received.

‘Here we go,’ Murphy said, sitting up in his chair, ‘he was reported missing.’

Rossi came back around the desk. ‘When?’

‘Get onto this … seven months ago.’

‘Well, that explains things. He’s been off getting into all kinds of shit, and now it’s caught up with him?’

‘Maybe,’ Murphy replied, leaning back in his chair. ‘But it didn’t look like he’d been living on the streets or anything. He looked, well, normal. Like he’d been looking after himself. For someone dead, anyway.’

‘I guess. I didn’t really look at him all that closely, to be honest.’

Murphy drummed his fingers on his desk, thinking back to the image of the victim he’d taken in his mind earlier that morning. A snapshot, something to keep in his head whilst he was working. ‘Clean fingernails,’ he said, after a few moments of silence.

‘What?’ Rossi replied, holding her hand out in front of her and studying it.

‘He had clean fingernails. I’m sure of it.’

‘Okay …’

‘We’ll have to check at the PM of course, but I’m pretty positive they were clean. If he was living rough, or in some dosshouse somewhere, they wouldn’t be, would they?’

Rossi looked at him with a blank face, which set Murphy on edge. He didn’t like being thought of as spouting rubbish. He’d seen that look reflected at him too often in the past, and he thought he was finally getting away from it.

‘I’m serious, Laura,’ he went on, after waiting a few seconds for her to respond and not getting anything. ‘This could be important. If he’s been missing seven months, we’ll need to know where he was. We can narrow the search straight off if he’s been somewhere where he’d have been able to keep clean.’

Rossi finally nodded, sparks hitting her eyes as she realised what he’d been implying. ‘I get you now. Good thinking, sir.’

‘It’s what I’m paid to do. Now, let’s get a picture of him from Doctor Houghton – get it over to the family. I want an ID sorted quickly.’ Murphy stood, leaving the smaller office and crossing into the wider office which housed the rest of the CID team. He strode over to the whiteboards which detailed the ongoing cases and began making a few notes underneath where someone had added that morning’s new victim.

‘Right,’ Murphy said, turning to face the few DCs who had been watching him. ‘Who’s going through initial neighbour reports?’

DC Sagan raised her hand. ‘Me, but there’s nothing there at the moment. No one heard anything in the adjoining street to the church. Only four houses were occupied when uniforms knocked though, so there’ll be more later when they’re back from work or whatever.’

‘Okay,’ Murphy replied, eyeing a particularly unpleasant sight trundling over towards the group. DS Tony Brannon, polluting the air as he walked, eating a packet of crisps, spilling crumbs across the carpet. A pain in the arse, but one Murphy had in check, he hoped. ‘Keep collecting reports,’ Murphy continued. ‘I want you in constant contact with the uniforms at the scene. Plus, DC Harris and DS Brannon, I want you to go down to the scene and help with enquiries.’

DS Brannon managed to pause in between mouthfuls to blurt out, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake …’

‘Don’t want to hear it, Tony. Just get your arse down there. I want something before the media start getting involved.’

‘Fine,’ Brannon replied. ‘Come on, Harris.’