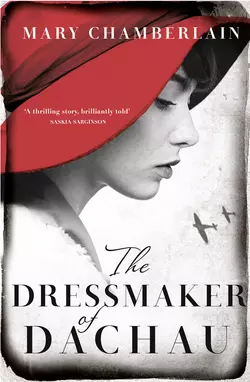

The Dressmaker of Dachau

Mary Chamberlain

THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLERSpanning the intense years of war, The Dressmaker of Dachau is a dramatic tale of love, conflict, betrayal and survival. It is the compelling story of one young woman’s resolve to endure and of the choices she must make at every turn – choices which will contain truths she must confront.London, spring 1939. Eighteen-year-old Ada Vaughan, a beautiful and ambitious seamstress, has just started work for a modiste in Dover Street. A career in couture is hers for the taking – she has the skill and the drive – if only she can break free from the dreariness of family life in Lambeth.A chance meeting with the enigmatic Stanislaus von Lieben catapults Ada into a world of glamour and romance. When he suggests a trip to Paris, Ada is blind to all the warnings of war on the continent: this is her chance for a new start.Anticipation turns to despair when war is declared and the two are trapped in France. After the Nazis invade, Stanislaus abandons her. Ada is taken prisoner and forced to survive the only way she knows how: by being a dressmaker. It is a decision which will haunt her during the war and its devastating aftermath.

Copyright (#uba36fb5b-22f8-59b0-ad0a-3e27a31e94ea)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Ms Ark Ltd 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photography by Henry Steadman. All other images © Shutterstock.com (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Lines from Alfred Noyes’ The Highwayman reproduced with permission from The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Alfred Noyes.

Mary Chamberlain asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007591558

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2016 ISBN: 9780007591541

Version: 2015-12-19

Dedication (#uba36fb5b-22f8-59b0-ad0a-3e27a31e94ea)

For the little ones – Aaron, Lola, Cosmo,

Trilby – and their Ba.

Contents

Cover (#u977b96b6-3262-53ef-a8bf-95911fae4528)

Title Page (#u5fb37c8a-aabf-5492-bc3e-e73288ccd6f3)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

One: London, January 1939

Two: London, July 1945

Three: London, November 1947

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

A Q&A: with Mary Chamberlain

About the Author

Also by Mary Chamberlain

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#uba36fb5b-22f8-59b0-ad0a-3e27a31e94ea)

The April sun cast shafts of light onto the thick slubs of black silk, turning it into a sea of ebony and jet, silver and slate. Ada watched as Anni ran her hand along the fine, crisp edges of the jacket, tracing the rich, warm threads and fingering the corsage as if the petals were tender, living blooms.

She was wearing it over a thick wool jumper and her cook’s apron, so it pulled tight around the shoulders. No, Ada wanted to say, not like that. It won’t fit. But she kept her mouth shut. She could see from Anni’s face that the jacket was the most beautiful thing she had ever possessed.

Anni was holding the key to Ada’s room in one hand and a suitcase in the other.

‘Goodbye,’ she said, throwing the key on the floor and kicking it towards Ada.

She walked away, leaving the door open.

ONE (#uba36fb5b-22f8-59b0-ad0a-3e27a31e94ea)

Ada peered into the broken mirror propped up on the kitchen dresser. Mouth open, tongue to attention, she plucked at her eyebrows with a pair of rusty tweezers. Winced and ouched until only a thin arc was left. She dabbed on the witch hazel, hoped the stinging would fade. Dunked her hair in clean, warm water in the old, cracked butler sink, patted it dry with a towel and parted it along the left. Eighteen years old, more grown up this way. Middle finger, comb and straighten, index finger, crimp. Three waves down the left, five down the right, five each herringbone down the back, pin curls and a Kirby grip tight to her skull, leave it to dry.

Ada was taking her time. She opened her handbag and fished around until she found her powder, rouge and lipstick. Not too much, in case she looked common, but enough to make her fresh and wholesome like those young girls from the Women’s League of Health and Beauty. She’d seen them in Hyde Park in their black drawers and white blouses and knew they practised on a Saturday afternoon in the playground of Henry Fawcett’s. She might think about joining them. It was good to be supple, and slender. She could make the uniform herself. After all, she was a dressmaker now, earned good money.

She rubbed her lips together to spread her lipstick, checked that the waves were holding their grip as her hair dried, picked up the mirror and carried it into the bedroom. The brown houndstooth skirt with the inverted pleats and the cream blouse with the enamel pin at the neck – that was smart. Good tweed, too, an offcut from Isidore, the tailor in Hanover Square. Just fifteen she was when she started there. Gawd, she was green, picking up pins from the floor and sweeping away fabric dustings, plimsolls grey from the chalk and her hand-me-down jacket too long in the arm. Dad said it was a sweatshop, that the fat capitalist who ran it did nothing but exploit her and she should stand up for her rights and organize. But Isidore had opened her eyes. He taught her how fabric lived and breathed, how it had a personality and moods. Silk, he said, was stubborn, lawn sullen. Worsted was tough, flannel lazy. He taught her how to cut the cloth so it didn’t pucker and bruise, about biases and selvedges. He showed her how to make patterns and where to chalk and tack. He taught her the sewing machine, about yarns and threads, how to fit a new-fangled zipper so it lay hidden in the seam and how to buttonhole and hem. Herringbone, Ada, herringbone. Women looking like mannequins. It was a world of enchantment. Beautiful hair and glistening gowns. Tailored knickers even. Isidore had shown Ada that world, and she wanted it for herself.

She wasn’t there yet. What with Mum demanding a share for her keep and the bus to work and a tea cake in Lyons with the girls on pay day, there wasn’t much over at the end of the week.

‘And don’t think you can come into this house and lord it around,’ Mum raised a stained finger at Ada, knuckles creased like an old worm, ‘just because you pay your way.’ Still had to do her share of the dusting and sweeping and, now she was trained up, the family’s dressmaking too.

Ada knew this life of scrimping and nit-combs and hand-me-downs was not what she was meant for. She damped her finger and thumb with her tongue, folded down her Bemberg stockings with the fitted toe and heel and rolled them up, crease by crease, careful you don’t snag, so the seam sat straight at the back. Quality shows. Appearances matter. So long as her top clothes looked good, nobody could touch her. Lips pinched, nose in the air, excuse me. Airs and graces, like the best of them. Ada would go far, she knew, be a somebody too.

She propped the mirror on top of the mantelpiece and combed her hair so it settled in chestnut waves. She placed her hat on her head, a brown, felt pillbox that one of the milliners at work had made for her, nudging it forward and to the side. She slipped her feet into her new tan court shoes and, lifting the mirror and tilting it downwards, stood back to see the effect. Perfect. Modish. Groomed.

Ada Vaughan jumped over the threshold, still damp from the scrubbing and reddening this morning. The morning sky above was thick, chimney pots coughing sooty grouts into the air. The terrace stretched the length of the street, smuts clinging to the yellow stock and to the brown net curtains struggling free from the open windows in the city-hobbled wind. She covered her nose with her hand so the murk from the Thames and the ash from the tallow melts wouldn’t fill her nostrils and leave blackened snot on the handkerchiefs she’d made for herself and embroidered in the corner, AV.

Clip-clop along Theed Street, front doors open so you could see inside, respectable houses these, clean as a whistle, good address, you had to be a somebody to rent here, Mum always said. Somebody, my foot. Mum and Dad wouldn’t know a somebody if he clipped them round the ear. Somebodies didn’t sell the Daily Worker outside Dalton’s on a Saturday morning, or thumb their rosaries until their fingers grew calouses. Somebodies didn’t scream at each other, or sulk in silence for days on end. If Ada had to choose between her mother and father, it would be her father every time, for all his temper and frustrations. He wasn’t waiting for Heaven but salvation in the here and now, one last push and the edifice of prejudice and privilege would crumble and everyone would have the world that Ada yearned for. Her mother’s salvation came after death and a lifetime of suffering and bleeding hearts. Sitting in the church on Sunday, she wondered how anyone could make a religion out of misery.

Clip-clop past the fire station and the emergency sandbags stacked outside. Past the Old Vic where she’d seen Twelfth Night on a free seat when she was eleven years old, entranced by the glossy velvet costumes and the smell of Tungstens and orange peel. She knew, just knew, there was a world enclosed on this stage with its painted-on scenery and artificial lights that was as true and deep as the universe itself. Make-up and make-belief, her heart sang for Malvolio, for he, like her, yearned to be a somebody. She kept going, down the London Road, round St George’s Cross and onto the Borough Road. Dad said there was going to be a war before the year was out and Mum kept picking up leaflets and reading them out loud, When you hear the siren, proceed in an orderly fashion …

Ada clip-clopped up to the building and raised her eyes to the letters that ran in black relief along the top. ‘Borough Polytechnic Institute’. She fidgeted with her hat, opened and shut her bag, checked her seams were straight, and walked up the stairs. Sticky under her arms and between her thighs, the clamminess that came from nerves, not the clean damp you got from running.

The door to Room 35 had four glass panels in the top half. Ada peered through. The desks had been pushed to one side and six women were standing in a semicircle in the middle. Their backs were to the door and they were looking at someone in the front. Ada couldn’t see who. She wiped her palm down the side of her skirt, opened the door and stepped into the room.

A woman with large bosoms, a pearl necklace and grey hair rolled in a bun stepped forward from the semicircle and threw open her arms. ‘And you are?’

Ada swallowed. ‘Ada Vaughan.’

‘From the diaphragm,’ the woman bellowed. ‘Your name?’

Ada didn’t know what she meant. ‘Ada Vaughan,’ her voice crashed against her tongue.

‘Are we a mouse?’ the woman boomed.

Ada blushed. She felt small, stupid. She turned and walked to the door.

‘No, no,’ the woman cried. ‘Do come in.’ Ada was reaching for the door-knob. She put her hand on Ada’s. ‘You’ve come this far.’

The woman’s hand was warm and dry and Ada saw her nails were manicured and painted pink. She led her back to the other women, positioned her in the centre of the semicircle.

‘My name is Miss Skinner.’ Her words sang clear, like a melody, Ada thought, or a crystal dove. ‘And yours?’

Miss Skinner stood straight, all bosom, though her waist was slender. She poised her head to the side, chin forward.

‘Say it clearly,’ she smiled, nodded. Her face was kindly, after all, even if her voice was strict. ‘E-nun-ci-ate.’

‘Ada Vaughan,’ Ada said, with conviction.

‘You may look like a swan,’ Miss Skinner said, stepping back, ‘but if you talk like a sparrow, who will take you seriously? Welcome, Miss Vaughan.’

She placed her hands round her waist. Ada knew she must be wearing a girdle. No woman her age had a figure like that without support. She breathed in Mmmmm, drummed her fingers on the cavity she made beneath her ribs, opened her mouth, Do re mi fa so. She held tight to the last note, blasting like a ship’s funnel until it left only an echo lingering in the air. Her shoulders relaxed and she let out the rest of the air with a whoosh. It’s her bosoms, Ada thought, that’s where she must keep the air, blow them up like balloons. No one could breathe in that deep. It wasn’t natural.

‘Stand straight.’ Miss Skinner stepped forward, ‘Chin up, bottom in.’ She threaded her way through the group, came to Ada and pushed one hand against the small of her back and with the other lifted Ada’s chin up and out.

‘Unless we stand upright,’ Miss Skinner rolled her shoulders back and adjusted her bosom, ‘we cannot project.’ She trilled her rrrs like a Sally Army cymbal. ‘And if we cannot project,’ Miss Skinner added, ‘we cannot pronounce.’

She turned to Ada. ‘Miss Vaughan, why do you wish to learn elocution?’

Ada could feel the heat crawl up her neck and prickle her ears, knew her face was turning red. She opened her mouth, but couldn’t say it. Her tongue folded in a pleat. I want to be a somebody. Miss Skinner nodded anyway. She’d seen the likes of Ada before. Ambitious.

*

‘I thought you were one of the customers,’ the Hon. Mrs Buckley had said, ‘when I saw you standing there, looking so smart.’ Taken for one of the customers. Imagine. She was only eighteen years old when she’d started there last September. Ada had learned fast.

The Hon. Mrs Buckley traded under the name ‘Madame Duchamps’. Square-hipped and tall, with painted nails and quiet earrings, she dazzled with her talk of couture and atelier and Paris, pah! She would flip through the pages of Vogue and conjure ballgowns and cocktail dresses from bolts of silks and chenilles which she draped and pinned round slender debutantes and their portly chaperones.

Ada had learned her trade from Isidore and her nerve from Mrs B., as the other girls all called her. Where Isidore had been wise and kind and funny, genuine, Mrs B. was crafted through artifice. Ada was sure the Hon. Mrs Buckley was neither an Hon. nor a Mrs, and her complexion was as false as her name, but that didn’t stop Mrs B. What she didn’t know about the female form and the lie of a fabric was not worth writing on a postage stamp.

Mrs B. was a step up from Isidore. Paris. That was the city Ada aimed to conquer. She’d call her house ‘Vaughan’. It was a modish name, like Worth, or Chanel, but with British cachet. That was another word she’d learned from Mrs B. Cachet. Style and class, rolled into one.

‘Where did you learn all this French, madame?’ The girls always had to call her ‘madame’ to her face.

Mrs B. had given a knowing smile, her head pivoting on the tilt of her long neck. ‘Here and there,’ she said. ‘Here and there.’

Fair dues to Mrs B., she recognized in Ada a hard worker, and a young woman with ambition and talent. Aitches present and correct without aspiration, haspiration, Ada was made front-of-house, Madame Duchamps’s instore fresh-faced mannequin, and the young society ladies began to turn to her to model their clothes, rather than Mrs B., whose complexion and waistline grew thicker by the day.

‘Mademoiselle,’ Mrs B. would say. ‘Slip on the evening gown.’

‘The douppioni, madame?’

Midnight blue with a halter neck. Ada would lean into her hips and sway across the floor, swirl so her naked back drew the eye, and that eye would marvel at the drape of the fabric as it swallowed the curve of her figure, out and in, and fanned in a fishtail. She’d turn again and smile.

‘And now the chiffon.’

Veils of mystery and a taffeta lining, oyster and pearl and precious lustres. Ada loved the way the clothes transformed her. She could be fire, or water, air or earth. Elemental. Truthful. This was who she was. She would lift her arms as if to embrace the heavens and the fabric would drift in the gossamer breeze; she would bend low in a curtsy then unfold her body like a flower in bloom, each limb a sensuous, supple petal.

She was the centre of adoration, a living sculpture, a work of art. A creator, too. She would smile and say, ‘But if you tuck it here, or pleat it there, then voilà.’ With a flourish of her long, slim fingers and that new, knowing voilà, Ada would add her own touch to one of Mrs B.’s designs and make it altogether more modern, more desirable. Ada knew Mrs B. saw her as an asset, recognized her skills and taste, her ability to lure the customers and charm them with an effortless eloquence, thanks to Miss Skinner’s skilful tutoring.

‘If you cut on the bias,’ Ada would say, holding up the dress length on the diagonal to a customer, ‘you can see how it falls, like a Grecian goddess.’

Draped across the breast, a single, naked shoulder rising like a mermaid from a chiffon sea.

‘Non, non, non.’ Mrs B. tut-tutted, spoke in French when Ada pushed the limits of decency. ‘That will not do, Mademoiselle. This is not for the boudoir, but the ball. Decorum, decorum.’

She’d turned to her client. ‘Miss Vaughan is still a little inexperienced, naïve, in the subtler points of social correctness.’

Naive she might be, but Ada was good publicity for Madame Duchamps, modiste, of Dover Street, and Ada had hopes that one day she could be more than an asset but a partner in the business. She had developed a respectable following. Her talent marked her out, the flow and poise of her design distinguished her. She conjured Hollywood and the glamorous world of the stars and brought them into the drawing rooms of the everyday. Ada became her designs, a walking advertisement for them. The floral day dress, the tailored suit, the manicured nails and the simple court shoes, she knew she was watched as she left the shop and sauntered west down Piccadilly, past the Ritz and Green Park. She would clip-clop along, chin in the air, pretending she might live in Knightsbridge or Kensington, until she knew she was free of curious eyes. Then finally she turned south, clip-clopped over Westminster Bridge and into Lambeth and past the sniggering urchins who stuck their noses in the air and teetered behind her on imaginary heels.

Late April, black rain fell in turrets and drummed on the slate roofs of Dover Street. Torrents, scooped from the oceans and let loose from the heavens, thundered down to earth and soaked deep into the cracks between the paving, fell in dark rivers along the gutters, eddied in dips in the pavements and in the areas of the tall, stuccoed houses. It splattered off the umbrellas and sombre hats of the pedestrians and soaked the trouser legs below the raincoats. It seeped into the leather of the shoes.

Ada reached for her coat, a soft camel with a tie belt, and her umbrella. She’d have to bite the bullet today, turn left right away, pick up the number 12 in Haymarket.

‘Good night, madame,’ she said to Mrs B. She stood under the door frame, then out into the sodden street. She walked towards Piccadilly, looking down, side-stepping the puddles. A gust of wind caught her umbrella and turned it inside out, whipped the sides of her coat so they billowed free and snatched her hair in sopping tentacles. She pulled at the twisted metal spokes.

‘Allow me, please,’ a man’s voice said as a large umbrella positioned itself above her head. She turned round, almost brushed the man’s face, an instant too close but long enough for Ada to know. His face was slim, punctuated by a narrow, clipped moustache. He wore small, round glasses and behind them his eyes were soft and pale. Duck egg blue, Ada thought, airy enough to see through. They chilled and stirred her. He stepped back.

‘I apologize,’ he said. ‘I was only trying to protect you. Here, you hold this.’ He passed over his umbrella and took hold of hers with his free hand. He sounded continental, Ada thought, a sophisticated clip to his accent. Ada watched as he bent it back into shape.

‘Not quite as good as new,’ he said. ‘But it will take care of you today. Where do you live? Do you have far to go?’

She started to answer, but the words tangled in her mouth. Lambeth. Lambeth.

‘No,’ she said. ‘Thank you. I’ll get the bus.’

‘Let me walk you to the stop.’

She wanted to say yes, but she was frightened he’d press her on where she lived. The number 12 went to Dulwich. That was all right. She could say Dulwich, it was respectable enough.

‘You’re hesitating,’ he said. His eyes creased in a smile. ‘Your mother told you never to go with strange men.’

She was grateful for the excuse. His accent was formal. She couldn’t place it.

‘I have a better idea,’ he went on. ‘I’m sure your mother would approve of this.’ He pointed over the road. ‘Would you care to join me, Miss? Tea at the Ritz. Couldn’t be more English.’

What would be the harm in that? If he was up to no good, he wouldn’t waste money at the Ritz. Probably a week’s wages. And it was in public, after all.

‘I am inviting you,’ he said. ‘Please accept.’

He was polite, well-mannered.

‘And the rain will stop in the mean time.’

Ada gathered her senses. ‘Will? Will it? How do you know?’

‘Because,’ he said, ‘I command it to.’ He shut his eyes, stretched his free arm up above his head, raising his umbrella, and clenched and opened his fist three times.

‘Ein, zwei, drei.’

Ada didn’t understand a word but knew they were foreign. ‘Dry?’ she said.

‘Oh, very good,’ he said. ‘I like that. So do you accept?’

He was charming. Whimsical. She liked that word. It made her feel light and carefree. It was a diaphanous word, like a chiffon veil.

Why not? None of the boys she knew would ever dream of asking her to the Ritz.

‘Thank you. I would enjoy that.’

He took her elbow and guided her across the road, through the starlit arches of the Ritz, into the lobby with its crystal chandeliers and porcelain jardinières. She wanted to pause and look, take it all in, but he was walking her fast along the gallery. She could feel her feet floating along the red carpet, past vast windows festooned and ruched in velvet, through marble columns and into a room of mirrors and fountains and gilded curves.

She had never seen anything so vast, so rich, so shiny. She smiled, as if this was something she was used to every day.

‘May I take your coat?’ A waiter in a black suit with a white apron.

‘It’s all right,’ Ada said, ‘I’ll keep it. It’s a bit wet.’

‘Are you sure?’ he said. A sticky ring of heat began to creep up her neck and Ada knew she had blundered. In this world, you handed your clothes to valets and flunkeys and maids.

‘No,’ the words tripped out, ‘you’re right. Please take it. Thank you.’ Wanted to say, don’t lose it, the man in Berwick Street market said it was real camel hair, though Ada’d had her doubts. She shrugged the coat off her shoulders, aware that the waiter in the apron was peeling it from her arms and draping it over his. Aware, too, that the nudge of her shoulders had been slow and graceful.

‘What is your name?’ the man asked.

‘Ada. Ada Vaughan. And yours?’

‘Stanislaus,’ he said. ‘Stanislaus von Lieben.’

A foreigner. She’d never met one. It was – she struggled for the word – exotic.

‘And where does that name come from, when it’s at home?’

‘Hungary,’ he said. ‘Austria-Hungary. When it was an empire.’

Ada had only ever heard of two empires, the British one that oppressed the natives and the Roman one that killed Christ. It was news to her that there were more.

‘I don’t tell many people this,’ he said, leaning towards her. ‘In my own country, I am a count.’

‘Oh my goodness.’ Ada couldn’t help it. A count. ‘Are you really? With a castle, and all?’ She heard how common she sounded. Maybe he wouldn’t notice, being a foreigner.

‘No.’ He smiled. ‘Not every count lives in a castle. Some of us live in more modest circumstances.’

His suit, Ada could tell, was expensive. Wool. Super 200, she wouldn’t be surprised. Grey. Well tailored. Discreet.

‘What language were you talking, earlier, in the street?’

‘My mother tongue,’ he said. ‘German.’

‘German?’ Ada swallowed. Not all Germans are bad, she could hear her father say. Rosa Luxemburg. A martyr. And those who’re standing up to Hitler. Still, Dad wouldn’t like a German speaker in the house. Stop it, Ada. She was getting ahead of herself.

‘And you?’ he said. ‘What were you doing in Dover Street?’

Ada wondered for a moment whether she could say she was visiting her dressmaker, but then thought better of it.

‘I work there,’ she said.

‘How very independent,’ he said. ‘And what do you work at?’

She didn’t like to say she was a tailoress, even if it was bespoke, ladies. Couldn’t claim to be a modiste, like Madame Duchamps, not yet. She said the next best thing.

‘I’m a mannequin, actually.’ Wanted to add, an artiste.

He leant back in the chair. She was aware of how his eyes roamed over her body as if she was a landscape to be admired, or lost in.

‘Of course,’ he said. ‘Of course.’ He pulled out a gold cigarette case from his inside pocket, opened it, and leant forward to Ada. ‘Would you like a cigarette?’

She didn’t smoke. She wasn’t sophisticated like that. She didn’t know what to do. She didn’t want to take one and end up choking. That would be too humiliating. Tea at the Ritz was full of pitfalls, full of reminders of how far she had to go.

‘Not just now, thank you,’ she said.

He tapped the cigarette on the case before he lit it. She heard him inhale and watched as the smoke furled from his nostrils. She would like to be able to do that.

‘And where are you a mannequin?’

Ada was back on safer ground. ‘At Madame Duchamps.’

‘Madame Duchamps. Of course.’

‘You know her?’

‘My great-aunt used to be a customer of hers. She died last year. Perhaps you knew her?’

‘I haven’t been there very long,’ she said. ‘What was her name?’

Stanislaus laughed and Ada noticed he had a glint of gold in his mouth. ‘I couldn’t tell you,’ he said. ‘She was married so many times, I couldn’t keep up.’

‘Perhaps that’s what killed her,’ she said. ‘All that marrying.’

It would, if her parents were anything to go by. She knew what they would think of Stanislaus and his great-aunt. Morals of a hyena. That was Germany for you. But Ada was intrigued by the idea. A woman, a loose woman. She could smell her perfumed body, see her languid gestures as her body shimmied close and purred for affection.

‘You’re funny,’ Stanislaus said. ‘I like that.’

It had stopped raining by the time they left, but it was dark.

‘I should escort you home,’ he said.

‘There’s no need, really.’

‘It’s the least a gentleman can do.’

‘Another time,’ she said, realizing how forward that sounded. ‘I didn’t mean that. I mean, I have to go somewhere else. I’m not going straight home.’

She hoped he wouldn’t follow her.

‘Another time it is,’ he said. ‘Do you like cocktails, Ada Vaughan? Because the Café Royal is just round the corner and is my favourite place.’

Cocktails. Ada swallowed. She was out of her depth. But she’d learn to swim, she’d pick it up fast.

‘Thank you,’ she said, ‘and thank you for tea.’

‘I know where you work,’ he said. ‘I will drop you a line.’

He clicked his heels, lifted his hat and turned. She watched as he walked back down Piccadilly. She’d tell her parents she was working late.

*

Martinis, Pink Ladies, Mint Juleps. Ada grew to be at ease in the Café Royal, and the Savoy, Smith’s and the Ritz. She bought rayon in the market at trade price and made herself some dresses after work at Mrs B.’s. Cut on the bias, the cheap synthetic fabrics emerged like butterflies from a chrysalis and hugged Ada into evening elegance. Long gloves and a cocktail hat. Ada graced the chicest establishments with confidence.

‘Swept you off your feet, he has,’ Mrs B. would say each Friday as Ada left work to meet Stanislaus. Mrs B. didn’t like gentlemen calling at her shop in case it gave her a bad name, but she saw that Stanislaus dressed well and had class, even if it was foreign class. ‘So be careful.’

Ada twisted rings from silver paper and paraded her left hand in front of the mirror when no one was looking. She saw herself as Stanislaus’s wife, Ada von Lieben. Count and Countess von Lieben. ‘I hope his intentions are honourable,’ Mrs B.’d said. ‘Because I’ve never known a gentleman smitten so fast.’

Ada just laughed.

*

‘Who is he then?’ her mother said. ‘If he was a decent fellow, he’d want to meet your father and me.’

‘I’m late, Mum,’ Ada said. Her mother blocked the hallway, stood in the middle of the passage. She wore Dad’s old socks rolled down to her ankles, and her shabby apron was stained in front.

‘Bad enough you come home in no fit state on a Friday night, but now you’ve taken up going out in the middle of the week, whatever next?’

‘Why shouldn’t I go out of an evening?’

‘You’ll get a name,’ her mother said. ‘That’s why. He’d better not try anything on. No man wants second-hand goods.’

Her mouth set in a scornful line. She nodded as if she knew the world and all its sinful ways.

You know nothing, Ada thought.

‘For goodness sake,’ Ada said. ‘He’s not like that.’

‘Then why don’t you bring him home? Let your father and I be the judge of that.’

He’d never have set foot inside a two-up two-down terrace that rattled when the trains went by, with a scullery tagged on the back and an outside privy. He wouldn’t understand that she had to sleep in the same bed with her sisters, while her brothers lay on mattresses on the floor, the other side of the dividing curtain Dad had rigged up. He wouldn’t know what to do with all those kids running about. Her mother kept the house clean enough but sooty grouts clung to the nets and coated the furniture and sometimes in the summer the bugs were so bad they had to sit outside in the street.

Ada couldn’t picture him here, not ever.

‘I have to go,’ Ada said. ‘Mrs B. will dock my wages.’

Her mother snorted. ‘If you’d come in at a respectable time,’ she said, ‘you wouldn’t be in this state now.’

Ada pushed past her, out into the street.

‘I hope you know what you’re doing,’ her mother yelled for all the neighbours to hear.

*

She had to run to the bus stop, caught the number 12 by the skin of her teeth. She’d had no time for breakfast and her head ached. Mrs B. would wonder what had happened. Ada had never been late for work before, never taken time off. She rushed along Piccadilly. The June day was already hot. It would be another scorcher. Mrs B. should get a fan, cool the shop down so they weren’t all picking pins with sticky fingers.

‘Tell her, Ada,’ one of the other girls said. Poisonous little cow called Avril, common as a brown penny. ‘We’re all sweating like pigs.’

‘Pigs sweat,’ Ada had said. ‘Gentlemen perspire. Ladies glow.’

‘Get you,’ Avril said, sticking her finger under her nose.

Avril could be as catty as she liked. Ada didn’t care. Jealous, most likely. Never trust a woman, her mother used to say. Well, her mother was right on that one. Ada had never found a woman she could call her best friend.

The clock at Fortnum’s began to strike the quarter hour and Ada started to run, but a figure walked out, blocking her way.

‘Thought you were never coming.’ Stanislaus straddled the pavement in front of her, arms stretched wide like an angel. ‘I was about to leave.’

She let out a cry, a puppy whine of surprise. He’d come to meet her, before work. She knew she was blushing, heat prickling her cheeks. She fanned her hand across her face, thankful for the cool air. ‘I’m late for work,’ she said. ‘I can’t chat.’

‘I thought you could take the day off,’ he said. ‘Pretend you’re sick or something.’

‘I’d lose my job if she ever found out.’

‘Get another,’ he said, shrugging his shoulders. Stanislaus had never had to work, couldn’t understand how hard she’d struggled to get where she was. Ada Vaughan, from Lambeth, working with a modiste, in Mayfair. ‘How will she find out?’

He stepped forward and, cupping her chin in his hand, brushed his lips against hers. His touch was delicate as a feather, his fingers warm and dry round her face. She leant towards him, couldn’t help it, as if he was a magnet and she his dainty filings.

‘It’s a lovely day, Ada. Too nice to be cooped up inside. You need to live a little. That’s what I always say.’ She smelled cologne on his cheeks, tart, like lingering lemon. ‘You’re late already. Why bother going in now?’

Mrs B. was a stickler. Ten minutes and she’d dock half a day’s wages. Ada couldn’t afford to lose that much money. There was a picnic basket on the pavement beside Stanislaus. He’d got it all planned.

‘Where had you in mind?’

‘Richmond Park,’ he said. ‘Make a day of it.’

The whole day. Just the two of them.

‘What would I say to her?’ Ada said.

‘Wisdom teeth,’ Stanislaus said. ‘That’s always a good one. That’s why there are so many dentists in Vienna.’

‘What’s that got to do with it?’

‘It’s a toff’s complaint.’

She’d have to remember that. Toffs had wisdom teeth. Somebodies had wisdom teeth.

‘Well,’ she hesitated. She’d lost half a day’s wages already. ‘All right then.’ Might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb.

‘That’s my Ada.’ He picked up the picnic basket with one hand, put his other round her waist.

She’d never been to Richmond Park, but she couldn’t tell him that. He was sophisticated, travelled. He could have had his pick of women – well-bred, upper-class women, women like the debutantes she clothed and flattered and who kept Mrs B. in business. Ahead of her the park gates rose in ornate spears. Below, the river curled through lush green woods to where the distant, dusty downs of Berkshire merged into slabs of pearl and silver against the sky. The sun was already high, its warm rays embracing her as if she was the only person in the world, the only one who mattered.

They entered the park. London was spread before them, St Paul’s and the City cast in hazy silhouette. The ground was dry, the paths cracked and uneven. Ancient oaks with blasted trunks and chestnuts with drooping catkins rose like forts from the tufted grassland and fresh, spiky bracken. The air was filled with a sweet, cloying scent. Ada crinkled her nose.

‘That’s the smell of trees making love,’ Stanislaus said.

Ada put her hand to her mouth. Making love. No one she knew talked about that sort of thing. Maybe her mother was right. He’d brought her here for a purpose. He was fast. He laughed.

‘You didn’t know that, did you? Chestnuts have male and female flowers. I guess it’s the female that gives off the smell. What do you think?’

Ada shrugged. Best ignore it.

‘I like chestnuts,’ he went on. ‘Hot chestnuts on a cold winter’s day. Nothing like it.’

‘Yes.’ She was on safe ground. ‘I like them too. Conkers, and all.’

And all. Common.

‘Different sort of chestnut,’ he said.

How was Ada to know? There was so much to learn. Had he noticed how ignorant she was? He didn’t show it. A gentleman.

‘We’ll stop here, by the pond.’ He put down the hamper and pulled out a cloth, flicking it so it filled with air like a flying swan, before falling to the earth. If she’d known she was going to have to sit on the ground, she’d have worn her sundress with the full skirt, enough to tuck round so she didn’t show anything. She lowered herself, pulled her knees together, bent them to the side and tugged her dress down as best she could.

‘Very ladylike,’ Stanislaus said. ‘But that’s what you are, Ada, a real lady.’ He poured two beakers of ginger beer, passed one to her and sat down. ‘A lovely lady.’

No one had ever called her lovely before. But then, she’d never had a boy before. Boy. Stanislaus was a man. Mature, experienced. At least thirty, she guessed. Maybe older. He reached forward and handed Ada a plate and a serviette. There was a proper word for serviette, but Ada had forgotten it. They never had much use for things like that in Theed Street. He pulled out some chicken, what a luxury, and some fresh tomatoes, and a tiny salt and pepper set.

‘Bon appétit,’ he said, smiling.

Ada wasn’t sure how she could eat the chicken without smearing grease over her face. This was all new to her. Picnics. She picked at it, pulling off shards of flesh, placing them in her mouth.

‘You look a picture,’ Stanislaus said. ‘Demure. Like one of those models in Vogue.’

Ada began to blush again. She rubbed her hand over her neck, hoping to steady the colour, hoping Stanislaus had not noticed. ‘Thank you,’ she said.

‘No,’ Stanislaus went on, ‘I mean it. The first time I saw you I knew you had class. Everything about you. Your looks, the way you held yourself, the way you dressed. Chic. Original. Then when you told me you made the clothes. Well! You’ll go far, Ada, believe me.’

He leant on one elbow, stretched out his legs, plucked a blade of grass and began to flutter it on her bare leg. ‘You know where you belong?’ he said.

She shook her head. The grass tickled. She longed for him to touch her again, run his finger against her skin, feel the breeze of a kiss.

‘You belong in Paris. I can see you there, sashaying down the boulevards, turning heads.’

Paris. How had Stanislaus guessed? House of Vaughan. Mrs B. said maison was French for house. Maison Vaughan.

‘I’d like to go to Paris,’ Ada said. ‘Be a real modiste. A couturier.’

‘Well, Ada,’ he said, ‘I like a dreamer. We’ll have to see what we can do.’

Ada bit her lip, held back a yelp of excitement.

He pushed himself upright and sat with his elbows on his knees. He lifted one arm and pointed to the deep bracken on the right. ‘Look.’ His voice was hushed. ‘A stag. A big one.’

Ada followed his gaze. It took her a while, but she spotted it, head proud above the bracken, the fresh buds of antlers on its crown.

‘They grow them in the spring,’ he said. ‘A spur for every year. That one will have a dozen by the end of the summer.’

‘I never knew that,’ Ada said.

‘Bit of a loner, this time of year,’ Stanislaus continued. ‘But come the autumn, he’ll build a harem. Fight off the competition. Have all the women to himself.’

‘That doesn’t sound very proper,’ Ada said. ‘I wouldn’t want to share my husband.’

Stanislaus eyed her from the side. She knew then it was a silly thing to say. Stanislaus, man of the world, with his much-married aunt.

‘It’s not about the women,’ he said. ‘It’s about the men. Survival of the fittest, that’s what it’s about.’

Ada wasn’t sure what he meant.

‘Wisdom teeth,’ Ada said.

Mrs B. raised a painted eyebrow. ‘Wisdom teeth?’ she said. ‘Don’t try to pull the wool over my eyes.’

‘I’m not.’

‘I wasn’t born yesterday,’ Mrs B. said. ‘You weren’t the only one skiving off. Nice summer’s day. I’ve given Avril her marching orders.’

Ada swallowed. She should never have let Stanislaus persuade her. Mrs B. was going to sack her. She’d have no work. How would she tell her mother? She’d have to get another position, before the day was out. Guess what, Mum? I’ve changed my job. She’d lie, of course. Mrs B. didn’t have enough work for me.

‘You knew there were big orders coming in. How did you think I was supposed to cope?’

‘I’m sorry,’ Ada said. She cupped her hand around her cheek, as Stanislaus had done, remembered the cool tenderness of his touch. Stick with the excuse. ‘It was swollen. It hurt too much.’

Mrs B. harrumphed. ‘If it had been any one of the other girls, you’d be out on your ear by now. It’s only because you’re good and I need you that I’ll let you stay.’

Ada dropped her hand. ‘Thank you,’ she said. Her body relaxed into relief. ‘I’m very sorry. I didn’t mean to let you down. It won’t happen again.’

‘If it does,’ Mrs B. said, ‘there’ll be no second chance. Now, get back to work.’

Ada walked towards the door of Mrs B.’s office, hand poised on the handle.

‘You’re really good, Ada,’ Mrs B. called. Ada turned to face her. ‘You’re the most talented young woman I’ve known. Don’t throw away your chances on a man.’

Ada swallowed, nodded.

‘I won’t be so tolerant next time,’ Mrs B. added.

‘Thank you,’ Ada said and smiled.

*

Ada stretched her slender fingers, took a cigarette and drew it to her lips. Legs crossed and wound round each other like the coils of a rope. She breathed in, inclined her head with the smile of a saint, and watched as the plumes of smoke furled from her nostrils. She leant forward and picked up her Martini glass. The Grill Room. Plush, red seats, golden ceilings. She glanced in the mirrors and saw herself and Stanislaus reflected a thousand times. They became other people in the infinity of glass, a man in an elegant suit and a woman in Hollywood cerise.

‘You’re very beautiful,’ Stanislaus said.

‘Am I?’ Ada hoped she sounded nonchalant, another word she’d picked up at Mrs B.’s.

‘You could drive a chap to distraction.’

She uncurled her legs, leant forward and tapped his knee. ‘Behave.’

A whirlwind romance, that’s what Woman’s Own would call it. A swirling gale of love that snagged her in its force. She adored Stanislaus. ‘It’s our anniversary,’ she said.

‘Oh?’

‘Fourteenth of July. Three months.’ Ada nodded. ‘Three months since I met you that day in April, in the pouring rain.’

‘Anniversary?’ Stanislaus said. He smiled, a crooked curl of his lip. Ada knew that look. He was thinking. ‘Then we should go away. Celebrate. Somewhere romantic. Paris. Paree.’

Paris. Paree. She longed to see Paris, hadn’t stopped thinking about it, since that day in Richmond Park.

‘How about it?’

She never thought he’d suggest going away so soon. Not now, with all this talk of Hitler and bomb shelters. ‘Isn’t there going to be a war?’ she said. ‘Perhaps we should wait a bit.’

‘War?’ He shook his head. ‘There’s not going to be a war. That’s just all talk. Hitler’s got what he wants. Claimed back his bits of Germany. He’s not greedy. Believe me.’

That wasn’t what her father said, but Stanislaus was educated. He was bound to know more.

‘You said you wanted to go,’ Stanislaus continued. ‘You could see some real French couture. Get ideas. Try them out here. You’d soon make a name for yourself.’

Ada opened her mouth to speak but her tongue rucked up like a bolster. She bit her lip and nodded, calculating quickly. Her parents would never let her go to Paris, not with all this talk of war, much less let her go with a man. They knew she was courting, but even so. She knew they wouldn’t like a foreigner. She told them he brought her home each night, made sure she was safely back. She told him her parents were invalids and couldn’t have visitors. She’d have to miss work, invent some excuse for going away otherwise she’d get the sack. What would she say to Mrs B.?

‘Do you have a passport?’ Stanislaus said.

A passport. ‘No,’ she said. ‘How do I get one of those?’

‘This isn’t my country.’ Stanislaus was smiling. ‘But my English friends tell me there is an office which issues them, in Petty France.’

‘I’ll go tomorrow,’ Ada said, ‘in my lunch hour. I’ll get one straight away. Will you wait for me?’ She’d tell her parents Mrs B. was sending her to Paris, to look at the collections, to buy new fabrics. She’d ask Mrs B. if she would really let her do that.

Only the man in Petty France said she needed a photograph, and her birth certificate, and seeing as how she was under twenty-one, her father needed to complete the form. They could issue it in twenty-four hours but only in an emergency, otherwise she’d have to wait six weeks.

‘But,’ he added, ‘we don’t advise travel abroad right now, Miss, not on the Continent. There’s going to be war.’

War. That was all anyone talked about. Stanislaus never mentioned war, and she liked him for that. He gave her a good time.

‘Can’t worry about what’s not here.’

The man frowned, shook his head, raised an eyebrow. Perhaps she was being a bit silly. But even if war was coming, it was months away yet.

She sniffed and put the papers in her handbag. She couldn’t ask her father to fill out the form. That would be the end of the matter. She’d never told Stanislaus how old she was, and he’d never asked. But if he understood she was a minor, he might get cold feet and lose interest in her. She was a free spirit, he’d said, he’d spotted it the first time they met. How could she tell him otherwise?

The solution came to her that afternoon, watching Mrs B. make out the bill for Lady MacNeice. Ada’s father wrote with a slow, careful hand, linking the arms and legs of his letters in a looping waltz. Ada had always been entranced by the way he choreographed his words, had tried to copy him when she was young. It was an easy hand to forge, and the man at Petty France would be none the wiser. She knew it was wrong, but what else could she do? She’d get her likeness taken tomorrow, in her lunch hour. There was a photographer’s shop in Haymarket. It would be ready at the weekend. She’d go to the public library on Saturday, fill in the form, take it in person on Monday. It would be ready in a few weeks.

‘Then it has to be the Lutetia,’ Stanislaus said. ‘There is simply no other hotel. Saint-Germain-des-Prés.’ He squeezed her hand. ‘Have you ever been on a boat?’

‘Only on the river.’ She’d been on the Woolwich ferry.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘August is a good month to sail. No storms.’

*

Ada had it worked out. She’d have to tell her parents, but she’d do it after she’d gone. Send them a postcard from Paris so they wouldn’t call the police and declare her a Missing Person. She’d have hell to pay when she got back, but by then Stanislaus and she would be engaged in all likelihood. She’d tell Mrs B. she was going to Paris on a holiday and would she like her to bring back some fabric samples, some tissus? She’d say it in French. Mrs B. would be grateful, would tell her where to go. That’s kind of you, Mademoiselle, giving up your holiday. It would give her something to do in Paris, and she could pick up ideas. In the meantime, she’d bring the clothes she planned to take to Paris with her to work, one at a time. She sometimes brought sandwiches for lunch in a small tote bag. It was summer, and the dresses and skirts were light fabrics, rayon or lawn. She knew how to fold them so they wouldn’t crease or take up space. She would hide everything in her cupboard at work, the one where she hung her coat in winter and kept a change of shoes. Nobody looked in there. She would need a suitcase. There were plenty in Mrs B.’s boxroom which was never locked. She’d borrow one. She had the keys to the shop. Come in early on the day, pack quickly. Catch the bus to Charing Cross, in good time to meet Stanislaus by the clock.

‘Paris?’ Mrs B. had said, her voice rising like a klaxon. ‘Do your parents know?’

‘Of course,’ Ada had said. She had shrugged her shoulders and opened her hands. Of course.

‘But there’s going to be a war.’

‘Nothing’s going to happen,’ Ada said, though she’d heard the eerie moans of practice sirens along with everyone else, and watched the air-raid shelter being built in Kennington Park. ‘We don’t want war. Hitler doesn’t want war. The Russians don’t want war.’ That’s what Stanislaus said. He should know, shouldn’t he? Besides, what other chance would she have to get to Paris? Her father had a different view about the war but Ada didn’t care what he thought. He was even considering signing up for the ARP for defence. Defence, he repeated, just so Ada wouldn’t think he supported the imperialists’ war. He even listened now as her mother read aloud the latest leaflet. It is important to know how to put on your mask quickly and properly …

‘But they’re going to evacuate London,’ Mrs B. said. ‘The little kiddies. In a few days. It was on the wireless.’

Three of her younger brothers and sisters were going, all the way to Cornwall. Mum had done nothing but cry for days, and Dad had stalked the house with his head in his hands. Pah! Ada thought. This will blow over. Everyone was so pessimistic. Miserable. They’d be back soon enough. Why should she let this spoil her chances? Paris. Mum would come round. She’d buy her something nice. Perfume. Proper perfume, in a bottle.

‘I’ll be back,’ Ada said. ‘Bright and early Tuesday morning.’ Engaged. She had been dreaming about the proposal. Stanislaus on one knee. Miss Vaughan, would you do me the honour of … ‘We’re only going for five days.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ Mrs B. said. ‘Though if you were my daughter, I wouldn’t let you out of my sight. War’s coming any day now.’ She waved her hands at the large plate-glass windows of her shop, crisscrossed with tape to protect them if the glass shattered, and at the black-out blinds above.

‘And your fancy man,’ she added. ‘Which side will he be on?’

Ada hadn’t given that a thought. She’d assumed he was on their side. He lived here, after all. But if he spoke German, perhaps he’d fight with Germany, would leave her here and go back home. She’d follow him, of course. If they were to be married, she’d be loyal to him, stay by his side, no matter what.

‘Only in the last war,’ Mrs B. went on, ‘they locked the Germans up, the ones who were here.’

‘He’s not actually German,’ Ada said. ‘Just speaks it.’

‘And why’s he over here?’

Ada shrugged. ‘He likes it.’ She had never asked him. No more than she had asked what he did for a living. There was no need. He was a count. But if they locked him up, that wouldn’t be so bad. She could visit and he wouldn’t have to fight. He wouldn’t die and the war wouldn’t last forever.

‘Perhaps he’s a spy,’ Mrs B. said, ‘and you’re his cover.’

‘If that’s the case,’ Ada said, hoping her voice didn’t wobble, ‘all the more reason to enjoy myself.’

‘Well,’ Mrs B. said, ‘if you know what you’re doing …’ She paused and gave a twisted smile. ‘As a matter of fact, there are one or two places you might care to visit in Paris.’ She pulled out a piece of paper from the drawer in her desk and began to write.

Ada took the piece of paper, Rue D’Orsel, Place St Pierre, Boulevard Barbès.

‘I haven’t been to Paris for so long,’ she said. There was a wistfulness in her voice which Ada hadn’t heard before. ‘These places are mostly in Montmartre, on the Right bank.’ Stanislaus had talked about the Seine. ‘So be careful.’

Their hotel was on the Left bank, where the artists lived.

*

Charing Cross station was a heaving tangle of nervy women and grizzling children, cross old people, worried men checking their watches, bewildered young boys in uniforms. Territorial Army, Ada guessed, or reservists. Sailors and soldiers. The occasional ARP volunteer elbowed his way through the crowd, Keep to the left. People took them seriously now, Air Raid Precaution, as if they really did have a job to do. A train to Kent was announced and the shambles surged forward, a giant slug of humanity. Ada stood her ground, shoved back against the crowd, banged her suitcase against other people’s shins. Watch out, Miss. The frenzy of the scene matched her mood. What if he wasn’t there? What if she missed him? She realized that she had no way of contacting him. He didn’t have a telephone. He lived in Bayswater, but she didn’t know his address. A woman pushed past her with two children, a boy in grey short trousers and a white shirt, a girl in a yellow, smocked dress. In fact, Ada thought, she knew very little about Stanislaus. She didn’t even know how old he was. He was an only child, he’d told her. Both his parents were dead, as was his much-married aunt. She had no idea why he had come to England. Maybe he was a spy.

This was daft. She shouldn’t go. She hardly knew him. Her mother had warned her. White slave trade. Stick a pin in you so you fainted and woke up in a harem. And all these people. Soldiers. ARP. There really was going to be a war. Stanislaus was wrong. Maybe he was a spy. The enemy. She shouldn’t go.

She spotted him. He was leaning against a pillar in a navy blue blazer and white slacks, a leather grip at his feet. She took a deep breath. He hadn’t seen her. She could turn round, go home. There was time.

But then he saw her, grinned, pushed himself forward, lifted his bag and swung it over his shoulder. A spy. A sharp prickle of heat crept up Ada’s neck. She watched as he wove his way towards her. It would be fine. Everything would be all right. He was a handsome man, despite his glasses. An honest man, anyone could see that. A man of means too. Nothing to worry about. Silly of her. His face was creased in a broad smile. He walked faster, pleased to see her. This, Paris, was happening to her, Ada Vaughan, of Theed Street, Lambeth, just by the Peabody buildings.

*

The Gare du Nord was full of the same sweating turmoil as Charing Cross, except the station was hotter and stuffier, and the crowds noisier and more unruly. Ada was transfixed. Why don’t they line up? Why do they shout? She was tired from the journey, too. She hadn’t slept the night before, and there wasn’t a seat to be had on the train to Dover. The crossing had made her queasy and the view of the white cliffs receding into a faint stripe of land had unsettled her in ways she hadn’t expected. Worry hammered in her head. What if war did come? What if they were stuck here? She couldn’t ignore the scrolls of barbed wire on the beaches ready to snare and rip the enemy. The hungry seagulls hovering over the deserted pebbles and bundles of scabby tar waiting for their morsels of flesh. The battleships in the Channel. Destroyers, Stanislaus called them, hovering hulks of metal, grey as the water.

Then Stanislaus had given her a ring.

‘I hope it fits.’ He pushed it onto her third finger. A single band of gold. Not real gold, Ada could tell that straight away.

‘You’d better wear it,’ he said. This was not how she imagined he would propose, and this, she knew, was not a proposal. Her stomach churned and she leant over the side of the ship.

‘I’ve booked the room under Mr and Mrs von Lieben.’

‘The room?’ Her voice was weak.

‘Of course. What else did you think?’

She wasn’t that kind of a girl. Didn’t he know that? She wanted to save herself for their wedding night. He wouldn’t respect her otherwise. But she couldn’t run away. She had no money. He was paying for all of this, of course he’d expect something in return. Mrs B. had hinted as much.

Stanislaus was laughing. ‘What’s the matter?’

She leant over the side of the ship, hoping the breezes would sweep out the panic lodged inside her head like a cannon ball. She was not ready for this. She thought he was a gentleman. Those society women, they were all loose. That’s what her father always said. Stanislaus thought she was one of them. Didn’t he see it was all a sham? The way she dressed, the way she spoke. A sham, all of it. She took a deep breath, smarted as the salty air entered her lungs. Stanislaus placed his arm round her shoulders. Free spirit. He pulled her close, cupped her face in his hand, tilted it towards him, and kissed her.

Perhaps this was what it took, to become a woman.

*

The hotelier apologized. They were so busy, what with all these artists and musicians, refugees, you know how it is, Monsieur, Madame … The room was small. There were two single beds, with ruched covers. Two beds. What a relief. There was a bathroom next to the bedroom, with black and white tiles and a lavatory that flushed. The room had a small balcony that looked over Paris. Ada could see the Eiffel Tower.

By night, Paris was as dark as London. By day, the sun was hot and the sky clear. They wandered through the boulevards and squares and Ada tried not to pay attention to the sandbags or the noisy, nervous laughs from the pavement cafés, or the young soldiers in their tan uniforms and webbing. She fell in love with the city. She was already in love with Stanislaus. Ada Vaughan, here, in Paris, walking out with the likes of a foreign count.

He held her hand, or linked her arm in his, said to the world, my girl, said to her, ‘I’m the happiest man.’

‘And I’m the happiest woman.’

Breeze of a kiss. They slept in separate beds.

Left bank. Right bank. Montmartre. Rue D’Orsel, Place St Pierre, Boulevard Barbès. Ada caressed the silks against her cheek, embraced the soft charmeuse against her skin and left traces on velvet pile where she’d run her fingers over. Stanislaus bought her some moiré in a fresh, pale green which the monsieur had called chartreuse. That evening Ada crossed the length across her breasts, draped the silk round her legs and secured it with a bow at her waist. Her naked shoulder blades marked the angles of her frame and in the bathroom mirror she could see how the eye would be drawn along the length of her back and rest on the gentle curve of her hips.

‘That,’ Stanislaus said, ‘is genius.’ And ordered two brandy and chartreuse cocktails to celebrate.

Ada stared with hungry eyes at the Chanel atelier in the rue Cambon.

‘Bit of a rough diamond, she was,’ Stanislaus said. Sometimes his English was so good Ada forgot he was foreign. ‘Started in the gutter.’

He didn’t mean it unkindly, and the story Stanislaus told gave Ada heart. Poor girl made good, against the odds.

‘Mind you,’ Stanislaus winked, ‘she had a wealthy male admirer or two who set her up in business.’

Distinctive style. A signature, she thought, that’s the word. Like Chanel. A signature, something that would mark out the House of Vaughan. And help from an admirer, if that’s what it took too.

‘Paris,’ she said to Stanislaus, as they strolled back arm in arm through the Luxembourg Gardens, ‘is made for me.’

‘Then we should stay,’ Stanislaus said, and kissed her lightly again. She wanted to shriek Yes, forever.

*

On their last morning they were woken by sirens. For a moment Ada thought she was back in London. Stanislaus pushed himself off his bed, opened the metal shutters and stepped onto the balcony. A shard of daylight illuminated the carpet and the end of her bed, and Ada could see, through the open doors, that the blue sky was no longer fresh and washed. They must have overslept.

‘It’s very quiet out there,’ Stanislaus called from outside. ‘Unnatural.’ He came in through the open door. ‘Perhaps it was the real thing.’

‘Well, we’re leaving today.’

They were going home and Stanislaus hadn’t proposed, nor had he taken advantage of her. That would count for nothing if she had to tell her parents. She would lie. She had it worked out. Mrs B. had sent her to Paris with one of the other girls, for work. They’d shared a room. The hotel was ever so posh.

‘Get up,’ Stanislaus said. His voice was clipped, agitated. He was pulling on his clothes. Ada swung her legs over the side of the bed.

‘Wait here,’ he said. She heard him open the lock, shut the door behind him. She sauntered into the bathroom and turned on the taps and watched as the steaming water fell and tumbled in eddies in the bath, melting the salts she sprinkled in. How could she go home to a galvanized tub in the kitchen? A once-a-week dip with the bar of Fairy?

An hour passed. The water grew cool. Ada sat up, making waves that washed over the side and onto the cork mat on the floor. She stepped out, reached for the towel, wrapped herself in its fleece, embracing the soft tufts of cotton for the last time. Paris. I will return. Learn French. It wouldn’t take long. She had already picked up a few phrases, merci, s’il vous plait, au revoir.

She stepped into the bedroom and put on her slip and knickers. She’d organize a proper trousseau for when she and Stanislaus married. He’d have to pay, of course. On her wages, she could barely afford drawers. She’d buy a chemise or two, and a negligee. Just three days in Paris and she knew a lot of words. She glanced at the bedside clock. Stanislaus had been gone a long time. She flung open the wardrobe doors. She’d wear the diagonal striped dress today, with the puffed sleeves and the tie at the neck. It had driven her mad, matching up all the stripes, so wasteful on the fabric, but it was worth it. She looked at herself in the mirror. The diagonals, dark green and white, rippled in rhythm with her body, lithe like a cat. She sucked in her cheeks, more alluring. She was grateful that Stanislaus left the room when she dressed in the morning, or undressed at night. A true gentleman.

There was a soft knock on the door – their signal – but Stanislaus barged in without waiting for her to reply. ‘There’s going to be war.’ His face was ashen and drawn.

Her body went cold, clammy, even though the room was warm. War wasn’t supposed to happen. ‘It’s been declared?’

‘Not yet,’ Stanislaus said. ‘But the officers I spoke to in the hotel said they were mobilized, ready. Hitler’s invaded Poland.’

There was an edge to his voice which Ada had never heard before.

War. She’d batted off the talk as if it were a wasp. But it had hovered over her all her life and she had learned to live with its vicious sting. It was the only time her father wept, each November, homburg hat and funeral coat, words gagging in the gases of memory, his tall frame shrinking. He sang a hymn for his brother, lost in the Great War. Brave enough to die but all they gave him was the Military Medal, not good enough for the bloody Cross. He had only been seventeen. Oh God, our help in ages past …

War. Her mother prayed for Ada’s other uncles whom she’d never met, swallowed in the hungry maws of Ypres or the Somme, missing presumed dead, buried in the mud of the battlefields. A whole generation of young men, gone. That’s why Auntie Lily never married, and Auntie Vi became a nun. That was the only time her mother swore, then. Such a bleeding waste. And what for? Ada couldn’t think of a worse way to die than drowning in a quagmire.

‘We have to go home,’ she said. Her mind was racing and she could hear her voice breaking. War. It was real, all of a sudden. ‘Today. We must let my parents know.’ She hoped now they hadn’t got her postcard. They’d be worried stiff.

‘I sent them a telegram,’ Stanislaus said, ‘while I was downstairs.’

‘A telegram?’ Telegrams only came when someone died. They’d go frantic when they saw it.

‘They’re invalids,’ Stanislaus said, ‘they must know you’re safe.’

She had forgotten she’d told him that. Of course.

‘That was,’ she stumbled for the word, ‘that was very kind. Considerate.’

She was touched. Stanislaus’s first thought had been of her, in all of this. And her parents. She felt bad now. She’d told him they were house-bound. She might even have said bedridden. She’d really be in for it now, when she got home. All those lies.

‘I sent it to Mrs B. The telegram. I didn’t have your address. She can let your parents know. I trust that’s OK,’ Stanislaus said and added, before she could answer, ‘Who’s looking after them? I hope you left them in safe hands.’

She nodded, but he was looking at her as if he didn’t approve.

They packed in silence. Officers in blue uniforms milled round the hotel lobby. There were soldiers too. Ada had never seen so many. The other guests, many of whom Ada recognized from the restaurant, argued in groups or leant, waving and shouting, against the reception desk. Ada was aware of the musk of anxious men, the lust of their adrenalin.

‘Follow me.’ Stanislaus took her bag. They pushed their way through the crowded lobby and out through the revolving doors.

‘Gare du Nord,’ he said to a bell boy, who whistled for a taxi. The once deserted street with its eerie silence was now full of sound, of scurrying people and thunderous traffic. There were no cabs in sight. Ada had no idea how far it was to the station. She could feel her head begin to tighten. What if they were stuck here in France? Couldn’t get home? At last, a taxi hove into view, and the bell boy secured it.

‘You didn’t pay,’ she said to Stanislaus, as they pulled away from the hotel.

‘I settled earlier,’ he said. ‘When I sent the telegram.’ She shut her eyes.

A solid wall of people filled the street, men, women and children, old and young, soldiers, policemen. Most of them were carrying suitcases, or knapsacks, all heading in the same direction, to the Gare du Nord. The people were silent, save for the whimper of a baby in a large pram piled high with bags, and the shouts from the police. Attention! Prenez garde! No one could move. All of Paris was fleeing.

They had to walk the last kilometre or so. The taxi driver had stopped the cab, shrugged, opened the door, ‘C’est impossible’.

‘It’s hopeless,’ Ada said. ‘Is there another way?’ People were crowding in behind them now. Ada looked quickly at a side street but saw that that was as thick with people as the main avenue.

‘What shall we do?’

Stanislaus thought for a moment. ‘Wait for the crowds to pass,’ he said. ‘They’re just panicked. You know what these Latin-types are like.’ He tried to smile. ‘Excitable. Emotional.’

He used their bags as a ram, beat a path to the side. ‘We’ll have a coffee,’ he announced. ‘Some food. And try later. Don’t worry, old thing.’

Ada would have preferred a cup of tea, brown, two sugars. Coffee was all right, if it was milky enough, but Ada wasn’t sure she could ever get used to it. Far from the station, the crowds had finally thinned. They found a small café, in the Boulevard Barbès, with chairs and tables outside.

‘This is where we were,’ Ada said, ‘when I bought the fabric. Just up there.’ She pointed along the Boulevard.

Stanislaus sat on the edge of his seat, pulled out his cigarettes, lit one without offering any to Ada. He was distracted, she could see, flicking the ash onto the pavement and taking short, moody puffs. He stubbed out the cigarette, lit another straight away.

‘It’s all right.’ Ada wanted to soothe him. ‘We’ll get away. Don’t worry.’

She laid her hand on his arm but he shook it off.

The waiter brought them their coffee. Stanislaus poured in the sugar, stirred it hard so it slopped on the saucer. She could see the muscles in his jaws clenching, his lips opening and shutting as if he was talking to himself.

‘Penny for them.’ She had to get him out of this mood. ‘Look on the bright side, maybe we’ll get to stay in Paris for another day.’ She didn’t know what else to say. It was not what she wanted, her parents going out of their minds, Mrs B. livid. She could picture her now, gearing up to sack her. She’d done that with one of the other girls who didn’t come back from her holidays on time. Do you think I run a charity? Right pickle they were in but they were stuck, for the time being. She had no one to turn to, only Stanislaus. The waiter had left some bread on the table, and she dipped it into her coffee, sucking out the sweetness.

‘Is there anyone who can help us?’ she said.

‘How?’

‘I don’t know.’ She shrugged. ‘Get us home.’ The French wouldn’t do that, she was sure, they had enough of their own kind to look after. Stanislaus turned in his seat, put his elbows on the table, and leant towards her. His forehead was creased and he looked worried.

‘The truth is, Ada,’ he said. ‘I can’t go back. I’ll be locked up.’ She drew a breath. Mrs B. had said something like that and all. Ada corrected herself, Mrs B. had said something like that too. Mustn’t drop her guard, not now, in case Stanislaus left her. You’re not who I thought you were.

‘Why?’ Ada said. ‘You’re not a German. You only speak it.’

‘Austria, Hungary,’ he said, ‘we’re all the enemy.’

Ada put her hands in her lap and pulled at her cheap ring, up, down, up down. She was stranded. She’d have to go back alone. She wasn’t sure she could do that, find the right train. What if they made an announcement and she didn’t understand? They did that all the time on the Southern Railway. We regret to have to inform passengers that the 09.05 Southern Railways train to Broadstairs will terminate at … She’d be stuck. In the middle of a foreign country, all by herself, not speaking French. And even if she got to Calais, how would she find the ferry? What if it wasn’t running anymore? What would she do then?

‘What will you do?’ Her voice came through high and warbling.

‘Don’t worry about me,’ he said. ‘I’ll be all right.’

It was already late in the afternoon. The waiter came out and pointed at their cups.

‘Fini?’

Ada didn’t understand so she shook her head, wished he’d leave them alone.

‘Encore?’

She didn’t know what it meant, but nodded.

‘I can’t abandon you,’ she said. ‘I’ll stay here. We’ll be all right.’ For a moment, she saw them, hand in hand, sauntering through the Tuileries.

Stanislaus hesitated. ‘The thing is, old girl.’ His voice was slow and quavering and for a fleeting moment he didn’t sound foreign, she’d got so used to his accent. ‘I have no money. Not now. With the war. I won’t be able to wire.’

Ada couldn’t imagine Stanislaus without money. He’d never been short of a bob or two, always flashed it round. Surely they wouldn’t be poor for long? And anyway being poor in Paris with Stanislaus would be different from being poor in Lambeth. She felt a surge of love for this man who had swept her off her feet, a warm, comfortable glow of optimism.

‘We don’t need money,’ she said. ‘I’ll work. I’ll look after us.’

The waiter reappeared with two more cups of coffee and placed them on the table, tucking the bill under the ashtray.

‘L’addition,’ he said and added, ‘la guerre a commencé.’

Stanislaus looked up.

‘What’s he say?’ Ada said.

‘Something about the war. Guerre is French for war.’

The waiter stood to attention. ‘La France et le Royaume-Uni déclarent la guerre à l’Allemagne.’

‘It’s started,’ Stanislaus said.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Of course I’m bloody sure. I may not know much French, but I understood that.’

He stood up abruptly, knocking the table so their coffee spilled in the saucers. He stepped to the side, as if he was leaving, then turned and sat back down again.

‘Would you stay with me?’ he said. ‘Here, in Paris? We’d get work, the pair of us. Won’t be short of money for long.’

Ada had been so sure a few moments ago, but now a wave of panic tightened round her head and fear clawed at her stomach. War. War. She wanted to be home. She wanted to sit in the kitchen at the back of the house with her parents and brothers and sisters. She wanted to smell the dank musk of the washing as it dried round the cooking range, to listen to the pots boiling potatoes for tea, to hear her mother thumb the rosary beads and laugh at her father as he mimicked her, Hail Marx, full of struggle, the revolution is with thee, blessed art thou among working men …

But there was no way she could get home, not by herself. She nodded.

‘Would you mind,’ Stanislaus said, ‘if we used your name?’

‘Why?’

‘My name’s too foreign. The French might lock me away.’

‘I don’t mind.’

‘I’ll get rid of my passport,’ he was talking fast. ‘Pretend I lost it. Or it was stolen. I could be anyone then.’ He laughed and the gold in his tooth glinted in the evening sun. He fished in his pockets for some coins to pay the waiter and picked up their bags.

‘Come,’ he said.

‘Where?’

‘We have to find somewhere to stay.’

‘The hotel,’ Ada said. ‘We’ll go back there.’

Stanislaus put his arm round Ada, and rested his chin on top of her head. ‘They’re full. They told me. We’ll find somewhere else. A little pension house.’

*

The room had a bed with a rusty iron frame and sagging mattress covered in stained ticking, a small table, a chair with a broken seat, and some hooks on the wall. The wallpaper had been torn off at some point, but stubborn shreds stuck in corners and above the wainscoting, bumping and rippling with the slumbering bugs beneath.

‘I can’t stay.’ Ada picked up her case and stepped towards the door. Stanislaus had never been poor, didn’t understand how low they had fallen.

‘I don’t know where you’ll go then,’ Stanislaus said. ‘With no money. The hotels will be full. The army have commandeered them.’ He sat on the bed, releasing a small cloud of dust. ‘Come here.’ His voice was soft, tempting. ‘It’s just till we get back on our feet. I promise you.’

They’d find jobs, move up in the world. She’d done it before, she could do it again.

‘What will you do?’ she said. ‘What job will you look for?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I’m not used to working.’

‘Not used to working?’

‘I’ve never had to,’ he said. She had forgotten. He was a Count. Of course Counts didn’t work. They were like Lords and Ladies. Bloody parasites, her father called them. Getting rich on the backs of the poor. For a moment Ada saw him from a different angle, as someone alien. She saw something else too: he was lost, didn’t know what to do. He was an innocent and she the streetwise urchin. She felt sorry for him. Pity. She could hear her father snorting. Pity? Would they ever take pity on you? Did the Tsar pity the peasants? Got what he bloody deserved.

Ada stood up. She was still wearing the striped dress. A bit crumpled, but she pulled it taut over her body and fished in her handbag for her lipstick. She dapped some on, rubbed her lips together.

‘I’ll be back,’ she said. She had to take charge. She knew where she was going.

*

Walked into the very first establishment, and landed herself a job. Ada couldn’t believe her luck. But she supposed that’s what she was: lucky. The wages weren’t much, but the work was plentiful. Monsieur Lafitte ran a thriving business. Wholesale, retail, and tailor. He was a congenial man who reminded her of Isidore. He spoke French very fast, but slowed down for Ada, took pains to help her learn the language. Ada filled the vacancy left by Monsieur Lafitte’s apprentice, who had enlisted in the army, leaving him with more work than he could handle himself. Although Ada longed to invent new drapes and cuts, and from time to time would suggest a new detail – the twist of a collar, the turn of a pocket – he’d frown and wag his finger. Non.

Within a week she and Stanislaus had moved from the filthy room to a small attic, closer to the shop and the better end of the Boulevard Barbès. Between Monsieur Lafitte and the concierge, Madame Breton, her French became passable and she was talking to customers even.

Ada couldn’t quite believe there was a war. It was too quiet, didn’t seem real, even though there were more soldiers on the streets and in the bars and cafés. There were stockpiles of sandbags on the corners, and shelters built in the parks and squares. Men and women walked about with gas masks slung over their shoulders.

‘Even the prostitutes,’ Stanislaus said. ‘I wonder how they do it, with those on?’

They hadn’t been issued with masks, but Stanislaus conjured two for them, tapping his nose, ask no questions. ‘I’m in business.’ She loved him, with his mystery and his charm and his strange, foreign accent that waxed and waned depending on how excited he was.

From time to time a siren wailed, but nothing came of it and at night the neighbourhood was black and impenetrable. Cloth was scarce, good cloth at least, and Ada began to cut the garments with a narrower fit and a shorter length, and a seam allowance that skimped and scraped.

*

‘What do you do all day when I’m not here?’ She and Stanislaus were sitting in the Bar du Sport. They’d been in Paris two months now and were regulars, had taken to having a glass of red wine at night before they ate dinner there. It was a far cry from cocktails at Smith’s, but Ada made an effort to dress up. Monsieur Lafitte let her have the remnants and offcuts and, with the new vogue for plain styles and shorter hems, Ada had run up a presentable winter frock for going out and some simple skirts and blouses. Monsieur Lafitte had given her some old clothes that, he said, had belonged to an uncle of his, now deceased, which Ada had remodelled for Stanislaus. Madame Lafitte had given her a winter coat which she had adjusted. Stanislaus would need a coat soon and Monsieur Lafitte had hinted that he might be able to lay his hands on some surplus army fabric. They made ends meet, and Stanislaus had money again.

They had recaptured something of the old days, but with a difference. Now they were man and wife. Not legally, but as good as.

‘I’ll be gentle,’ he’d said the first time, ‘and wear a rubber.’

‘A what?’

‘A johnny. What do you call them?’

Ada didn’t know. She’d heard bits and pieces from the girls at Mrs B.’s, but nobody had ever sat her down and said this is what happens on your wedding night. Her mother had talked about the sacrament of marriage and Ada thought it something so holy that babies could be made in ways they couldn’t if you weren’t married. Stanislaus had laughed. This bit is for this, and that for that. She knew it was wrong, not being married, but it seemed natural, sidling close so her body soaked up his male smell and her flesh rippled and melted in his warmth. She knew he’d propose, once the war was over in a few months, make an honest woman of her.