The Draughtsman

Robert Lautner

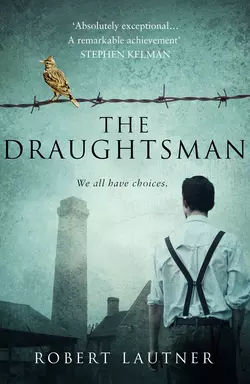

Speak out for the fate of millions or turn a blind eye? We all have choices.‘Absolutely exceptional. So beautifully written, with precision and wisdom and real emotional acuity … A remarkable achievement’ STEPHEN KELMAN, author of Pigeon English1944, Germany. Ernst Beck’s new job marks an end to months of unemployment. Working for Erfurt’s most prestigious engineering firm, Topf & Sons, means he can finally make a contribution to the war effort, provide for his beautiful wife, Etta, and make his parents proud. But there is a price.Ernst is assigned to the firm’s smallest team – the Special Ovens Department. Reporting directly to Berlin his role is to annotate plans for new crematoria that are deliberately designed to burn day and night. Their destination: the concentration camps. Topf’s new client: the SS.As the true nature of his work dawns on him, Ernst has a terrible choice to make: turning a blind eye will keep him and Etta safe, but that’s little comfort if staying silent amounts to collusion in the death of thousands.This bold and uncompromising work of literary fiction shines a light on the complex contradictions of human nature and examines how deeply complicit we can become in the face of fear.

THE DRAUGHTSMAN

Robert Lautner

Copyright (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on

historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Robert Lautner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover images © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (figure); www.Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (all other images)

Every effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologise to those concerned and will undertake to include suitable acknowledgements in all future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008126711

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008126735

Version: 2018-01-09

‘It is not so much the kind of person a man is as the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act.’

Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View (1974)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u13e3acb2-9d03-535e-935a-1480e673648e)

Title Page (#ub887af95-e287-5f8b-93db-6d7ca73dd209)

Copyright (#u178f0265-3fc1-540a-bc94-ba46fc7564ad)

Epigraph (#u061cf259-be2b-5186-ac25-aa7228f0ab9c)

Prologue (#uac91385a-45e8-51a7-a27a-3eef25daa4e8)

Part One (#uc5948684-9702-53d7-8ae2-96b8d403eff4)

Chapter 1 (#u84032a0b-4031-5d0b-914a-829d8744970e)

Chapter 2 (#u7daa1eef-d150-5001-91a8-fad784289a29)

Chapter 3 (#u30d72c94-3137-5542-b565-24c43ff6dc59)

Chapter 4 (#u4bc8f70e-ba8f-5b43-a02c-4218a066125d)

Chapter 5 (#u07c5b666-dc88-504c-b506-76c6b488ba28)

Chapter 6 (#u7a4fda1d-00c6-5c61-a688-70b29a0f6347)

Chapter 7 (#u34c157d2-22bb-5856-964e-49d96eb11806)

Chapter 8 (#u6dae0246-b671-5417-b7f5-f522d8a0717b)

Chapter 9 (#u5345cedc-d7f5-5786-992e-257611d5083e)

Chapter 10 (#u8caf5e7a-d711-5e3e-848b-8660a98debad)

Chapter 11 (#uf937f9f6-87ab-51f4-8aed-d0508a77af15)

Chapter 12 (#ubc388527-ad04-58df-92b4-7046032b5741)

Chapter 13 (#u1ddb422a-08ec-5876-95bf-b13435535b21)

Chapter 14 (#ude6b126e-993f-5de4-a8ed-e866518dbea7)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Robert Lautner (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

Erfurt, Germany,

February 2011

The site had become a squat for the disenfranchised, for anarchic youth. They even formed a cultural group. Artists and rebels. Appropriate. Perhaps.

Over the bridge, across the railway that once moved the iron goods from the factory to the camp at Buchenwald, Erfurt still maintained its tourist heart, its picture-book heart. A place where romance comes. Where carriages drawn by white horses still mingle with trams and buses and young and old marrieds hold hands crossing the market square. Rightly fitting, just so, that the industrial quarter on Sorbenweg ignored, left to rot, to be forgotten. A despised relative a hurt family no longer calls upon. Its only colour in the graffiti, signs and spray-paint portraits that only the youth understood.

The squatters removed, the land and remaining dying buildings reimagined. Erfurt ready to remember that history, no matter its shade, had something to pass on.

Myra Konns ran the morning tours of the museum risen from the ruins of the Topf administration buildings. She guided school-children through the original ISIS drafting tables they had found scattered and vandalised over the years by the transients, guided them through the director’s rooms still furnished with the wide cabinets that once held drafts for cremation ovens. Labels still sitting in their brass handles. The impression of ink soft and leaving. The drawers empty. Yawning only dust and memory. All restored now.

Myra would show them the small canisters with the clay plaques that the factory made to store ashes to be collected by relatives; a legal requirement until someone decided that it was no longer required. Hundreds of them found abandoned and empty in an attic in Buchenwald. These and other smaller items all on the third floor, where the drafting tables were repaired and displayed, where the chief designer’s office had been recreated, where the tours could still see from the window to Ettersberg mountain as the draughtsmen at their tables would have done and Myra would point out that the smoke from the Buchenwald ovens could be seen crawling over the mountain all day. All day.

The oven doors, removed from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the most sombre items of the tour. No need to highlight the prominence of the company plaque set above them. Topf and Sons exhibited now as the ‘Engineers of the Final Solution’. A brochure saying so.

In one display cabinet Myra would put her hand to a drawing of an experimental oven, never employed; for the allies had closed in before its realisation. Beside it a letter from a director to Berlin explaining the function of the new design. And Myra would always choose her words with care.

‘It works on four levels over two floors, one of which is the basement, where the morgue would traditionally be, replaced by the furnace. The deceased would be put in at the top and a series of rollers over grates would convey them to the furnace. The letter confirms the effectiveness of the design at being able to work continuously. Day and night. Reducing the need for coal as the oven was intended to be fuelled by the deceased themselves. Hundreds, possibly thousands of corpses a day. No intention to distinguish one from the other. A machine. An eradication device criminal in nature and design. Thankfully never introduced. The Allies having liberated Auschwitz some months before.’

A hand went up in the midst of the group. Myra took a breath. An old man. Always a sparse group of old men and women dawdling amongst the children. In her induction, just the month before when the museum opened, Myra had been informed to be especially aware of the aged visitors. The air about the place theirs. The tomb of it theirs.

‘Yes, sir?’

‘Excuse me, Fräulein,’ he bowed slightly. White, pomade-brushed hair and grey-blue eyes that smarted from the cold February wind outside, made worse by the radiator warmth of the halls. He wiped his eyes behind his glasses.

‘That correspondence does not refer to the design of the continuous oven. Of that oven.’

Myra’s breath released. Always one.

‘Sir. This letter has been donated from the Russian archives. It has been verified by many experts.’

He moved forward, his age more apparent in his careful step, in his politeness in moving through the young elbows that might bruise him as he passed.

‘Forgive, Fräulein. That oven – the continuous oven – was patented in 1942. That letter was for a circular design. From Herr Prüfer. From one of the engineers.’ He tapped a finger on the glass. ‘This drawing was for a new annotation of the previous patent. Ordered to be redrafted in May 1944.’

Myra looked between him and the glass display. Always one.

‘I’m sure it is not a mistake, sir.’

He wiped his forehead.

‘We have all made mistakes, Fräulein.’

He bent to the cabinet, lifted his glasses to peer at the fading paper within.

‘This is only an error. This article comes from the Americans, does it not?’

‘It is paired with the letter from the Russian archive.’

‘No.’ His lips thinned. ‘I can assure you.’

‘How is that, sir?’ As respectful as she could.

He moved towards her, as if he did not want the children to hear, as if he wished no-one but Myra to collect his whisper. She could smell the pomade in his hair, looked down at the expensive shoes as she moved to not tread on them.

‘Because I gave it to the Americans.’ His hand back to the glass shielding the exhibit. ‘Because I drew it.’

*

Myra found him sat outside. Cap playing in his hands, eyes at the ground. Sat beside him without invite. He began as if the conversation had started minutes before and he finishing it off, rounding it off politely so he could put on his cap and leave.

‘We were married in Switzerland. In ’41. Her parents had moved there. Run there. Etta’s father – Etta was my wife – was wealthy. Wealthy for those days. A property man. I thought I had done well to marry a woman of means. Poor all my life. Where are you from, Fräulein?’

‘Munich.’

‘Ah. Just so. I was born in Erfurt. You know the Merchants’ Bridge? That was my childhood home. An ancient place. The people ancient. Me – a boy – an intruder on the bridge. When my father needed to tan me I would hide all about the stairs and gutters. The little paths. Right under the bridge. He would never find me. Old cities full of hiding places. They are built around the hiding places. Modern cities are not like this. They are built straight and plain. Wide. Open. It is because the people do not need to hide as much. Old cities. They cringe around the churches like children to their mother’s skirts.’

Myra watched him look about the walls. Breathing them.

‘I was grateful to work here. No-one will understand. My Etta did not even understand. And she knew everything.’ The wink of German humour.

Myra leaned closer, had to speak over the noise of a new arrival of children.

‘What happened here?’

He put back his cap. Not to leave. Against the cold.

‘Nothing. Nothing happened here.’ Sat back against the bench. ‘Always the problem.’

He rubbed the salt and pepper grey of his stubble. Grunted at the disapproval of it.

‘Left early,’ he said. ‘To get here. I need a shave.’

PART ONE (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

Chapter 1 (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

Erfurt, Germany,

April 1944

I shave every other day. The new blade already dull when purchased, yet twice as expensive as the year before. Steel for higher order than grooming. But I will shave tomorrow morning as I am not the man I was yesterday. I have work now. My first since I graduated and married.

There is the man you were the last year, without work, and then there is this day. And nothing is the same. The clock ticks down the hours to your first day, not just to the next day. A man has signed your name alongside his own. A contract. Real work.

And you begin.

I always stand by the curtained window looking over the street three floors below when Etta and I have these serious talks. I have a cigarette and she lays on the chaise-longue that her mother gave her for our wedding. The window half-open to exhale my evening smoke and to watch the street pass by and listen to the trains bringing workers home. Our voices never raise. We have become dulled. Like the blades of my razor that were never sharp. I am too weary from not working and she is tired from me not doing the same. Only couples understand such malaise.

‘It is a job, Etta. Forty marks a week. We owe two months’ rent.’

‘A skilled draughtsman. Forty marks a week.’ Tutted her disdain.

I draw on my cigarette, blow it against the curtain, just to annoy.

‘It is a start. A beginning.’

‘A low one. You start from the bottom. Four years of study and you gain the lowest rung.’

‘I have no experience. Herr Prüfer has selected me because he came from the same study. That is a good wage for a new man. You want to stay in these rooms forever?’

A one-bed apartment with a kitchenette off the living-room. Etta put up new curtains which made all the difference. The curtains I was blowing smoke on.

She is draped over the chaise-longue like Garbo, her breasts accentuated through her dark dress, the one with the small red roses the same colour as her hair, the evening sun painting them further. I go back to smoking through the curtains and the window. A man below removes his homburg to wipe his sweating pate. Even at six o’clock it is still warm, warm for April, but all the businessmen are still in full dress, except that waistcoats seem to have vanished. Either a lack of textiles or some American trend. The harder grimier worker in cap, cardigan and jacket. That will not be me. I will be with the businessmen. I can feel Etta seething behind me.

‘I did not expect to be the wife of a man who makes pictures of grain silos for a living.’

Pictures. Pictures she says. Belittled with a word. Austrian women do this well, even the ones born in Erfurt like Etta. Austrian by proxy.

‘It is a start.’ I draw a long, calming drag. ‘They do other things. Crematoria. They do dignified crematoria.’

‘How is that “dignified”?’

She said this in that cursing inflection that Austrian women perfect along with their curtsies. Swearing and not swearing. Her mother’s voice.

‘I spoke to Paul about it last week. Before my interview.’

Paul Reul, an old school friend of mine. He had made a name for himself as a crematorist in Weimar, a successful businessman. A thing to be admired in wartime. We did not see him so much since the jazz club where we used to meet had been closed, since we had married. Always the way. Your single friends become strangers.

‘He told me Topf invented the electric and petrol crematoria. Changed the design so you could have a dignified service, like a church, with the oven in the same building. Topf did that. Made a funeral out of it.’

‘It is all disgusting.’

‘Before that the dead were all burnt out the back, a different place. Like hospitals. Just incinerators. Like for refuse.’ I punctuate smoke into the room. Etta revolted. Not at my smoke.

‘Stop talking about it. It is horrible. Why would you talk on such things?’

The cigarette goes out the window. Her disappointment a mystery. Real work. My first contract to draft plans since leaving the university. Silos or not. A start in wartime. Not an end. Not like so many others. But Topf and Sons were hiring. Everywhere else in Erfurt closing. I guess the army had need for a lot of silos.

She swings her legs from the lounger.

‘I have to get ready for work. There is some ham and pickles you can eat.’

She goes to the bedroom removing the pins from her hair as she sways, her voice over her shoulder.

‘I am pleased you have work, Ernst. I am just in a mood. And I shall probably miss you during the day.’

Etta’s café job started at seven. Three nights a week if we were fortunate. Kept us fed when my subsistence ran out and she could always bring home leftovers, sometimes unfinished wine if the diners could afford it. It was long work when it came. Often she would not return until past one, the café closing at ten for the blackout, but the work goes on beyond the leave of guests. Only staff know this. The hard work is after the bill has been paid.

She closed the door to change. Her mystery always maintained by how many doors she could close. Fewer now than in our old place that we could no longer afford. Here I would put my fingers in my ears when she made her toilet, her insistence, the rooms that small. In our bedroom we can hear our neighbours flushing their broken cistern. You don’t find that out when they show you the place.

She puts her make-up on before I wake. We sleep in separate beds, pushed together when desire desires. Three years married and I had never been permitted to know that she washed her undergarments, or seen them drying. As far as I knew she hung those silks out for faeries to attend to.

This her upbringing of course. Better than mine. My confidence in my good looks gave me no doubts why Etta Eischner should fall for a boy from the bridge. My grey-blue eyes and blond hair enough. But not to her parents. No reason for Herr Eischner to see why his daughter loved a penniless student, despite the blue eyes, despite the groomed blond hair. A boy from the bridge. Herr Eischner had plenty of suitable young men she could meet, rich stock like his, good stock. A boy from the bridge. Nothing in his pockets but dreams. Dancing in the clubs. Too much drinking, too much walking late at night. Too many dark alleyways for him to pull her into. The red look on her face when she came home far too late. She refused to join the bridge club or the Rotary, before they were outlawed of course, where good young men with connections and families could be found. The flame hair of her not the least of her fire.

Eventually he settled. Remembered even when little his daughter had always been looking for something she could never find, that even he could not satisfy, not when she was little and not when she had grown and argued with him on his politics and business. And that was why the blue-eyed boy came. She cooled after she had him. Poor boys from the bridge more capable than he where daughters are concerned. ‘Curiosity killed the cat,’ they say. To dismiss and persuade the young to seek. To tut, and warn them to not question. But they forget the final line: ‘But satisfaction brought it back.’ The poor boy from the bridge brought it back. The best the father would get.

I sniff my black tie that needs washing. All ties thin now. Again, either fashion or a textile shortage. I preferred them this way. Less like a noose. Tomorrow it will be a working tie. Odd to be starting new work on a Thursday. You assume Monday. They must be busy. Good. Though I will miss that serial play they put on the radio at lunch time. I suppose only housewives should listen anyway.

Working men do not need the radio.

Chapter 2 (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

Our apartment is on Station Street, a grey shrivelled building next to the largest hotel in Erfurt and we share a double-front door with the radio shop below us. I wink to Frau Klein, our landlady, sweeping the porch. She has not seen me outside the door before nine until now and she eyes me like the Devil.

‘Work to go to, Frau Klein,’ I tell her. ‘I start a new job this morning. Work at last! Won’t you be happy for me?’

She grunts, as those of her profession do when they have been widowed and forced to let out their rooms to young married smiles.

‘I will be happy to be paid.’ And the broom beneath the bosom drags on. But still I whistle as I step by. To add to her disdain of me, of all youth.

My name called from above. Etta with a kiss, a wave.

How fine it still is to have someone you love call out your name, past the time when it was necessary to do so across a fair or a crowded square in courtship, for now you do not need to meet, are always a hand’s reach from each other, and the echoed call of your name is rare. But going to work on your first day a time to hear the call again. And envious men look up with me to the pale shoulder slipped from the gown and the red tussled hair. And then their heads go back to their feet as I stride. Taller than them. If only in pride. I look at their passing fedoras. Eyeing those I may one day pick and choose to purchase. My own poor replica winter-beaten.

I had sold my bicycle, for who needs a bicycle in winter when there is only flakes of tea in the cupboards, so now I would walk to my employment in April sun following all the other black coats and hats to the station. But I am still grinning because I am not like them. I am one better than them. I will not be cramped and stifled in a smoky carriage. I am not an hour or two from my office. I will go through the station and over the footbridge to my work with Etta’s warm body still glowing on me. A mile walk. Just enough time to clear your head and good enough exercise for all the working week to keep off the fat which I will soon be putting on our Sunday table.

I thread through the crowds shuffling to buy their tickets, shuffling to their transits and trucks, and take the iron-capped stairs two at a time. Puffed when I reach the top. In two weeks that will change. In two weeks I might have worn-out shoes but by then be able to buy a pair without care. Or perhaps not. It has been a long time since I looked at the price of shoes.

Over the bridge the landscape changed, you could not even see the dominating cathedral. As you walk to the station the city becomes a gradual grey, as work beckons, but you are only minutes away from the pretty doll’s houses of our medieval streets and the statues always looking down, pitying those walking beneath them. The city I have lived all my life, the city of study, of Martin Luther, of grand culture uniquely German, and mercifully not bombed. We still had two synagogues, one the oldest in Europe, one a burned-out shell since ‘crystal night’. But no-one now to use them of course. That had happened. The same as everywhere.

All my life in Erfurt and I had never seen this part of town. Tall old buildings, last century and more. Crumbling now.

I would have been thirteen when these homes became the ghettoes. Empty now, or the homes of the adamantly unemployed and destitute drunk. Fine homes upon a time, judged only by my looking to their pediments and stonework. Still it is only a short walk, and I have nothing worth stealing, no bicycle, not even a watch – also sold – for who needs a watch with no work to go to. But sure I will be at the doors of Topf and Sons in good time, and time enough for one rolled breakfast cigarette, not knowing if Topf subscribed to the government’s ban. Trains you could still smoke on but not the trams and buses, not in public buildings.

When I was first at Erfurt University you could smoke in class, and then the rules came and soon after that my first professor, Josef Litt, was removed from class, by the Sturmabteilung, the SA no less, the chalk still in his hand as he was carried out by his elbows, half a word written on the board, never finished. Jews now not permitted to teach, to do anything in public work. We got the week off. Then we got an American professor, his German as bad as his breath, and my second year a struggle.

A right into Sorbenweg, chimneys along the skyline, already smoking, and then the long wall of Topf, a clutch of city-style houses opposite, not slums.

The administration building hides the construction factories and workshops that cover almost half a square mile. A neat front, three storey, concealing the heavy and dirty work boiling behind it, the manual workers coming in through another entrance. The smart wooden gate for suits not overalls.

A black chimney in the centre of the roof, the white letters of Topf encircling. In my eye, my draughtsman’s eye, I see the one-dimensional plan of stoves heating the floors all connecting to this chimney, the furnace in the basement, but no need for it now, not in April.

I am not nervous. My first opportunity in the workplace yet I am confident. Perhaps bolstered by Prüfer’s admiration of my qualifications, perhaps by Etta’s admiration, enthusiastically bestowed that morning, in that blue light before April dawn. Always the best time. Or perhaps confidence always wears a suit.

The woman at the desk wishes me good morning. She looks like she has been up for hours, fresh and beaming, and I am sure not the same woman I saw last week. My eyes weeping from my walk, worse because they are such a pale blue. Almost an old man’s eyes. An annoyance all my life. Too sensitive to sunlight and wind.

From the clock behind her I am five minutes early. Good, but I realise this is probably where my employers and directors also enter for their work. An anxiety about this. I would rather meet them at my desk in white-coat than in my shiny suit and worn hat.

‘Can I help you, sir?’

She asks so delightfully that I almost do not understand the words. I give her my employment letter.

‘Ernst Beck,’ I said. ‘Hired by Herr Prüfer.’

She asks me to take a seat and presses a telephone. The chairs are modern. Sweeping chrome and fine leather, more comfortable than my armchair at home. I leaf through technical magazines laid on a low glass and chrome table, one eye to the door to get ready to stand if an expensive suit approaches. But I suppose, with relief, that maybe directors and owners do not get into work so early.

I hear the clack of smart shoes coming from the marble staircase, hurried but rhythmical, like the wearer is dancing down not to meet me but Ginger Rogers.

The gleaming black wing-tips appear, then a suit I do not think I could ever afford. The cloth so black he seems fluid, floats to me like a wraith.

He held out his hand as I stood and bowed, lower than I intended.

‘Herr Beck. I am Hans Klein. So pleased to meet you,’ he ushered me to the stairs. ‘I should get you a pass for your car so it does not get mistaken.’

I do not mention that Klein is also my landlady’s name.

‘No need, Herr Klein. I only live across from the station. I walked.’

‘Oh. Really? Good. I live in Weimar myself. Not in the city. In the country. I apologise. It is my fault to assume that everyone drives to work. I suppose we have many local people here. This way, please.’ He led me up the stairs, talking effortlessly as he went with his dancer’s feet and I struggled to keep up.

‘Come to my office, Herr Beck. I will acquaint you with the nature of things. No need to worry on your first day. No-one is to expect much of you. Just relax and enjoy. This is why we start you on Thursday. Today and tomorrow you are to familiarise yourself with the department, meet everyone, and we can start you in earnest on Monday.’ We reached the third floor and he smiled as he waited for me to gain. ‘In earnest … Ernst.’ He laughed. ‘Earnest Ernst. Quite a quip, no?’

His talk as smooth as his suit.

‘Yes, sir.’ It was then I saw the lift, and he noticed, seemed pleased with my crestfallen look He was not much older but assured in exactly the same way that I am not. If I enter a bar or café I wait patiently until I am attended to. He is one who snaps his fingers and calls.

‘Ah. I forget the lift. I always take the stairs. I drive so much. I take the opportunity to exercise whenever I can. No need for you, of course, walking everywhere as you do. I am envious of you for that. Come.’

He walked beside me, his arm against my back. I tried to place where I had seen his face before, and then it came. It was in his smile. All teeth. It was Conrad Veidt, an actor, in a film I had seen as a boy. Veidt had left for America with his Jewish wife. He had terrified me as a child in a film. A man who could only grin, ear to ear after a horrible torture to his face. A Victor Hugo book. I thought it would be an adventure, like his other books. It was not. The film ran through my mind in an instant. A silent film. The first card of speech in front of me again:

‘Jester to the king. But all his jests were cruel, and all his smiles were false.’

I was to ask him about his position when we came to his frosted glass door with the gold lettering.

‘Hans Klein. Director of Operations. D IV.’

*

He reached across me to open the door and waved me in before him. ‘Please, Ernst. After you.’ Herr Beck now left downstairs.

He was behind his desk before I reached a chair and I stood beside it while he popped open a metal orb on his desk and dozens of cigarettes fanned out from underneath its top. He took one and an onyx table-lighter and I stood and waited for him to light it and he let me stand while he did so. Three strikes of the lighter and three puffs before he noticed me again. Camels. I could smell they were Camels. Not our cheap German Kamels but actual American. I was not sure if American Camels were black-market. Surely not. Just rare now. Expensive now.

‘Oh. Excuse my manners, Ernst. Please take a seat. I am so often on my own here – excepting meeting with Topf – that I sometimes forget myself with my staff.’

He said, ‘Topf’. Not ‘Herr Topf’.

‘Cigarette?’ He waited until I was seated to offer. I would have to stand to take one.

‘No thank you, sir.’ He closed the orb, the cigarettes drawing in magically.

‘Please. Call me Herr Klein. No formalities on my floor. Do you not smoke? I can smell it on you? Or maybe it is just from walking through the station and the streets?’

‘Yes, but I did not know whether … I did not know the rules for the building. I am so used to the ban.’

He took his black leather chair, his suit disappearing within.

‘Fortunately we are not a public building yet. I do not travel publicly so I suppose the smoking ban does not bother. Although we have many contracts with the SS so I would not smoke around them should you see them, or around Prüfer or Topf who are Party members. And you are not permitted to smoke on the draft floors or public areas.’ He leaned back, put his feet up on something I could not see and exhaled hugely. ‘Coffee?’

‘No, thank you. Unless you are having one, Herr Klein?’

‘I never drink coffee.’ He waved his cigarette. ‘I find it disagrees with my Martinis!’

That grin again. I did want coffee. I was lucky if I could afford three cups a week. To be offered it free and to turn it down. Still, my first day. Be a polite fool. These were successful men. Confident men. Not in war. Ernst Beck the young one amongst them. The apprentice. These were not people I knew, not my world.

As a boy I played football – my father’s encouragement – before the first war that was all the entertainment he had. Football a German invention to him. A game that marked towns above each other more than harvest.

I played on the wing, but would always want to be a striker, every boy did. Sometimes we would play against the boys from Weimar, the richer boys. Weimar paid for us to play. Bought our footballs, bought our kit.

‘Let them win,’ my father would say. ‘Ernst. Play the game.’ His finger stern above me, bent to me, breath like stale meat. ‘Do not be the hero. We are not here to always score goals. To win. If we always beat them too much less money they will give. Do you want to play next year or win today? What is for the better?’

The polite fool. Know what you will gain. And what you will lose. The democracy of the football match. Sometimes you cannot afford to be the best team. But you will play next year. I could have scored five times against those Weimar boys. Sometimes a goal is just a goal. Two posts without a net.

‘It is polite,’ my father would say. ‘You win by making it better for next year. By losing today. By abiding.’

I became a good German because of that. Got new kit the next year. Played the game.

‘Do you have your identification card?’ He put out his hand. I fumbled inside my jacket, gave across the rough cardboard we all hated to carry. Not obliged to carry. Preferred. It would go back in a drawer that evening. I had been asked to bring it. Normal to be copied for employment purposes.

‘Thank you, Ernst. I’ll have it back to you today.’ He did not put it away, placed it on his desk, and then it sat between us like a brick. ‘You’ll be given a worker’s pass as an alternative to use.’ He blew his smoke towards me. ‘I have looked over your qualifications. Prüfer and Sander are sure you will be competent. Understand that we have lost a great deal of men to the service over the years. We have to make do with less experienced men, but it is a great opportunity for yourself. I hope you understand?’

‘It is the opportunity I seek and am grateful for, Herr Klein. I will do my best.’ Polite fool.

‘You will have to. These recent months we are often using prisoners from the camps, from Buchenwald, so the plans are ever simpler and of cheaper construction for them to comprehend. Still, the labour is cheap.’ He put out his stub that I would consider not done. ‘I believe that Sander – you will meet him tomorrow – is most looking forward for you to work on his new designs. They are patented but need … clarifying. To be presented to the SS. His originals are too complicated for the layman. We need someone to present them efficiently and more simplified. With our shortened workforce all our best draughtsmen are working on the malt works and silos and they have been with the designs for years so that is where our best men need to be. Which is why we have hired yourself, Ernst.’

I straightened in my seat.

‘Am I not to be working for the silo department?’

‘No. Sander is our chief designer for the crematoria. My department. “Special Ovens.” Our smallest department. The smallest part of our business. But we are one of the foremost in the world. And getting ever busier, thanks to the SS. The more camps they build the more ovens they need. And because they want them so cheap they are always wanting repairs. Repeat business. The best business. Prüfer and the engineers are always fixing something at Auschwitz or Buchenwald and beyond. I limit myself to Buchenwald if I can.’ He stood and I followed. ‘Come. I will show you the floor. Not the floor with the skylights I’m afraid. That is for our top draughtsmen. But the second floor is pleasant enough. There is a fine view of the hills. All day you can see the smoke from Buchenwald rising to them. It is a pleasant room.’ His hand on my back again, his other already on the door.

Chapter 3 (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

I did not know how to mention the ovens to Etta at dinner.

Bern sausage, sauerkraut and swede. Etta put the meal on the table with pride. Pride for me.

‘Ernst, we should see your parents this weekend. Celebrate your good news now it is official.’

I found an orchestra on our ‘people’s radio’. No long-wave any more and you paid two marks a month to listen to Wagner or Kraus. As a boy we used to have these great jazz stations. My mother and father danced then. Waltzed around the floor amid my electric train set that never truly worked but that I pretended did should my father punish me for breaking it. All other music gone now, all too degenerate for our sensibilities. The kids still listen somehow. A black-market in music they record on their Tonfolien machines and share. Swing-kids. That is what we call them. You cannot keep kids from music, no matter how black you think it is. Our leaders forget that’s how they came to be. Older people told them ‘no’ once too. They should be proud of the youth emulating them. And I have to listen to Wagner.

‘My parents? You want to put that upon us on a Sunday?’ I sat at the table. Wished I had wine.

‘It’s been months since we saw them. At least now we have something to see them for instead of just borrowing money.’ A snipe at me? No, she was smiling. I do not think she meant to offend. Just married talk. ‘Don’t you want them to be proud?’

‘Hardly proud.’

‘And why not? You are in a company in wartime. Would they rather you were at the front?’

‘Which one?’

I was at university, had missed conscription. And Erfurt had no military attachment or demand for young men to serve. Too deep in the country for administration then. The first war different. Men had come from the forests to fight, my father amongst. Someone considered that if the enemy were faced with these giant axe-wielders they would drop their guns and run. Not now. These were the places that needed to be protected. We were the Germans of Germany. The heart that the rest fought for. The war distant from us, protected by mountains of pine bastions like a great wall. During the summer those who were students in Berlin or Munich would be deployed as medics to the front. Imagine being shot and having a geography student patch you up? I guess stabs of morphine would be their limit. Pat his chest in sympathy and then move on to the next. It was what those students saw at the front that began the protests when they returned to their universities. Their last protests.

Our city almost distinct from the war. The war heading east. A Russian war. The West done now. Africa and the Mediterranean ours. Victory assured. Normality coming back. My job a sign of that. Normality. New cars on the streets and the trains running on time. Klein had shown me his new Opel before I left. I do not know why. To me a car is just a car but I suppose these things are important to certain men. He lifted the engine’s cover.

‘Look at the plate.’ He had placed his hand on the engine to introduce it. ‘A General Motors engine! Ford and General Motors supplying German cars. We cannot all afford Mercedes! And we have their American engines in our army trucks. I wonder how the Yankee soldiers feel when they discover this. They bomb a supply convoy and find American engines in the trucks. That must be a kick! And we even sell them our ovens for their own prison camps. Topf are the largest exporter of crematoria. Not that we ever had any Jewish business. The Jew does not approve of crematoria.’ That grin again. ‘The body is only borrowed to them. It must be returned as given. Enjoy your walk home. Tomorrow you will meet Sander so shine your shoes better.’ He slapped my back. ‘Soon you will have your own car, no?’

*

‘Etta, I must tell you something.’ My cutlery still on the table. Her face became too concerned or maybe it was the look on mine.

‘What is it, Ernst?’

‘It seems that for the time … for the moment … as I am the new man … I must begin work on the second floor. Under Herr Klein.’

‘The second floor? What is that? You are not working on the silos?’

‘No. The second floor is for the Special Ovens Department. Special designs.’

‘Special? How are they special?’

I took my fork, ate into the mash, the meat too steaming to eat for a while. We often eat one after the other, Etta first. I have to let my food cool, like a child, otherwise my night will be just heartburn and milk.

‘Furnaces and incinerators for the prison camps. I’ll know more tomorrow when I meet Herr Sander.’

‘Aren’t the prisons run by the SS? You don’t have to work with them, do you?’

‘Herr Klein says I might meet them in the building. They are only officers, Etta.’

She ate slow.

‘I know. But it is just when you say SS you think of Gestapo. It is so quiet here. To think that just across the tracks there are SS. Here.’

In the single bulb light over our table her face had lowered as she ate, as if reading the tablecloth like a book in a library. I had never heard her mention the SS or Gestapo at our table before. This not dinner talk. A husband’s duty to ease his wife’s concerns.

‘I am to make the designs simpler for them to understand. Label everything. They won’t understand the Alphabet of Lines so I must make it clear.’

‘You do not think of the prisons needing ovens.’ Her voice almost too quiet for me to catch.

‘It is just like hospitals and schools. You need ovens for refuse, for heat, for the dead. No-one likes to think that hospitals have crematoria. Anywhere you have large numbers of sick people you need crematoria.’

Her fork rang against her plate.

‘Ernst! I am eating! Why are you always using that word?’

‘Etta, I am working for a company that makes crematoria. For all the world. I am going to be using that word often if you want me to talk on my day. If you consider it correctly it is probably one of the most important subjects. Paul almost holds it as a religion. It has laws.’

The mention of Paul, our crematorist friend in Weimar seemed to lighten the air. I had an ally. Not a conspirator. Paul’s business could not exist without furnaces. This she would have to concede. Just a business. That’s all.

‘Well … use a different word. Say “oven”. That sounds better. And stop talking about the dead. There is no place for that in this house. And certainly not at my table.’

I apologised. Moved the talk to visiting my parents. Agreed to it. They lived on the Krämerbrücke, the Merchants’ Bridge, in the medieval part of the city. The house I was born in. The houses on the bridge itself. On stormy nights I was always terrified in my bed that we would collapse into the river. Etta’s parents had moved to Switzerland with her sister when the Americans joined the war. They feared invasion. We travelled there to get married. Etta insisted that her mother should see her wed and her father should take her arm. My own parents not attending. They do not travel. My father does not leave the bridge. All the stores he needs are there, he says. All his friends are there, he says.

‘Why do I have to meet strangers?’ he would shrug. ‘I have met and outlived everyone I ever need to.’ And he laughed at the passing of his friends.

We finish our supper, turn down the radio and the light. Tomorrow I meet Herr Sander. Too anxious to make love and we go to sleep just holding each other, the beds pushed together. My brain will not sleep and I try to imagine what Sander will look like.

‘Ernst?’ Etta whispers above my head under hers. ‘I am glad I did not have to work tonight. It was good to eat together.’

I sighed into her chest and pulled her tighter. Her hair on my cheek. Red hair smells different. It blooms of youth somehow, like newborns in their close perfume.

‘Ernst? The SS wouldn’t look into us would they? If you are working with them?’ A tension in her hold of me, as if I was about to be pulled out of bed and away. I touched her hand, felt it calm.

‘I’m not working with them. I work for Topf.’ I lifted my head. ‘Why? Do I have a criminal I should worry about?’

She pulled me back to her breast. ‘No! Do I have a criminal to worry about?’

‘I have a receipt from your father for you. I could ask for an exchange.’ She held me closer.

‘You wish you could afford me.’

And the night came, the blackout, the sleep of couples.

Chapter 4 (#u0741705f-59e9-5e96-9f01-a7f8e03604e2)

Raining the second day. Not the best walk. Raincoat and umbrella at least and Topf had a cloakroom where they might dry by the end of the day, as long as the day were longer than yesterday; not much more than a tour of the floors, the factory and barrack buildings where the workers from the camps ate a meal before the transport back to Buchenwald.

I had thought of Herr Sander all night. He the chief signatory of the design departments. Outside of the ownership of the company – the Topf brothers – the man in charge. I wondered what he might be like. A good boss or a hard one. I was sure all men only rise if they were the latter. My father would come home from Moor’s pharmacy every night and be quiet for the first half-hour. Some wine and a sandwich before dinner and he would begin to talk and smile again. Sundays he would spend sighing and devouring the newspaper. I do not think he enjoyed his work. The pharmacy had to sell up in ’35 to German buyers, the Jewish owners no longer permitted to be part of the community. I remember before then going as a boy with my mother to take my father his lunch one Saturday. We came out and a young man handed us both a leaflet. My mother paled as she read and the young man tipped his hat at us, went along with a whistle. The leaflet Gothic in script and tone.

‘You have just been photographed while you have been buying Jewish. You are going to be shamed in public.’

We had not bought anything. We were bringing my father his meal but the man did not know. My mother whisked me away in the opposite direction. Spat her words.

‘These bastards.’ She was pulling me along now. ‘Never trust a man in a suit, Ernst. He only wishes to lend you money or take it from you.’

I recall that my father was just as unhappy with his new employers as the old ones.

Prüfer I perceived to be a good man. He smiled, made jokes, he asked after my university. He was an engineer, had started at the bottom with Topf and determined his way to become a head man. He was pleased I had no children.

‘They interfere with a man’s career,’ he said. ‘Wait until you are a director! Children are a vice to a man’s promise when he is young.’

Fritz Sander did not offer a handshake. He nodded when Herr Klein introduced me in his office and I returned the nod as proficiently as his own. I had my white-coat now, my blond hair smoothed back with Etta’s pomade. It felt like I was at work. That I almost belonged.

‘Has Herr Klein detailed your work here?’ His answer already known.

‘Yes, sir. The Special Ovens Department.’ They were both standing, hands behind their back and I put mine the same.

‘It is important work, Topf has secured the contracts for all ovens for the prisons.’ I saw his skin was raw around his moustache and neck. A shaving rash like all of us except for Klein’s talcum smoothness. Even the wealthy had trouble getting good blades I supposed. But Sander’s grey hair was closely cut, precision sharp around his ears. He did not get his cut by his wife in a kitchenette with sewing scissors. A waft of Bay Rum as he moved.

‘The regular muffle ovens have become inadequate. They break. Operated by inexperienced men. And they are overworked. We are able to supply mobile counterparts and engineers to repair but new ones must be built. I have hired you to help me prepare the drafts.’

I opened my mouth to speak but he anticipated.

‘You need not know anything about crematoria. I just need you to replicate the drafts from the designs. For SS approval. Any aspect you do not understand can be put to Herr Klein or Herr Keller on the third floor for annotation. The designs are to be as clear as possible for a layman.’

I had prepared questions as I slept, in my dreams. Questions that an ambitious man might ask.

‘These new designs will improve the process, sir?’

His eyes now smaller through his glasses.

‘How do you mean?’

‘That Topf is superior throughout the world for crematoria. I’m sure we are improving all the while. I am honoured to be a part of such endeavour.’

Sander half-turned, hands opening and closing at his back.

‘These contracts were won on price not quality.’ He turned back to me sharply. ‘You know our closest competitor?’

‘Kori of Berlin, sir.’

‘Quite so. We beat a Berlin company because of our price and location.’

Klein lifted his hand for my attention. Spoke proudly.

‘And that when the call came we installed mobile systems into Mauthausen within a day. That is service,’ he said.

‘Mobile systems, sir?’ I had heard this word previously, jumped on it now.

‘Stock items,’ Klein said. ‘For farmers, small abattoirs and such, who do not need their own scale furnace. Petrol fired. The incinerators had broken and they needed an emergency replacement. We fulfilled where Berlin could not.’

Sander raised a finger to me and then to Klein. ‘That reminds. Herr Klein is going to Buchenwald. A site visit. Monday. It would be useful for you to attend.’

I inhaled, stalled.

‘To the prison?’

‘We are measuring for new muffles,’ Sander said as reply. ‘It would be useful for you to see our work first hand. It is important for an architect to see the fulfilment of his task. You will learn much.’

I would like to say that I feigned enthusiasm. But I was curious in that pedestrian way people stare at accidents or listen to a neighbour’s fight or as a child you try to peek a look into the butcher’s back room as he emerges when his bell rings, wiping his hands and beaming at your mother.

And this my work after all.

‘That would be most interesting, sir.’

‘Good,’ Sander nodded again. ‘Be sure to bring your identification.’

Chapter 5 (#ulink_4c588dc1-49a1-5ee7-a3b4-dbb593db347c)

Before supper Etta and I went for a walk. The early evening dry and warm, my coat only a little still damp from the morning’s rain. We went arm in arm by the river, towards the bridges and the old quarter. Etta had asked what Sander was like, how my day had been. I volunteered the walk. Easier to tell her outside.

‘The camp!’ Etta stopped walking, pulled her arm away. Stragglers coming home scowled from beneath their caps.

‘The prison, Etta. Buchenwald is well established. Topf has hundreds of workers from the place in the factory.’

‘Slaves you mean.’

‘Labour for their crimes.’

‘But Ernst, it is a camp. People die there. There is disease. Dangerous men.’

I took her arm again and strolled slower.

‘Klein and the engineers go there often. I am sure it is safe.’

‘I don’t like it. Why did you say you would go?’

‘I could hardly refuse on my second day.’ We walked into the cobbled streets, a walk around the block to take us back to Station Street. Quiet here. The Jewish businesses closed and sold to develop into apartments, but that had stopped. The developers no doubt waiting for the war to end any month now and the prices to rise. But even with the boarded-up windows a nice peaceful stroll in April.

‘Do you like this Herr Klein?’

‘I do not know him. Does it matter? He’s the head of the floor. When the war ends a few of those who used to work there may come back. Part of their service is to retain their old jobs. I must do well before then. Everything I can.’

‘Will you have to join the Party?’

‘No-one has mentioned. Prüfer wears a pin. A standard one. Herr Sander did not. Nor Klein.’

‘Would you? Would you join?’

I do not know why I did not think before answering. It seemed natural to say it.

‘If it helped my career. For you. For us. All other business ties are gone. No Freemasons or Rotaries. How else do you get on?’

We said no more on this.

If you live near to your parents you walk slower to meet them for Sunday lunch than if you had to get on a train where at least you can pretend that something enjoyable is happening. The slow walk, lingering around shop windows, all to avoid the dreaded hour. The walk enlivened by the Sunday street all looking to the sky as a squadron of Heinkels flew west overhead. Our skies normally silent.

Etta shielded her eyes to watch.

‘Where do you think they are going?’

‘I don’t know. England? Early for a raid. Where from is more interesting. I did not know we had bases in the east.’

‘Perhaps the Russians have surrendered. And we have taken their bases.’

‘Do they even have bases to take? I thought them all farmers?’

She slapped my arm. ‘Ernst. They are an army. I’m sure they have planes.’

‘We conquered France didn’t we? And they have toilets inside their homes. The Russians?’ I cocked my thumb over my shoulder. ‘Toilet behind the house with chickens in it. That is all you need to know.’

The streets animated again and we came to the old bridge. You may know the Merchants’ Bridge from songs or pictures from a Christmas butter-biscuit box. A fairytale place. One of the last medieval bridges in Europe that still had the colourful houses and shops built right on its stone. Paris and London had lost theirs hundreds of years ago. Erfurt maintained. We know our history. It is still here. England does not know us to bomb. Their bridge fell down, as the song would have it. Because they did not care enough for history.

I was born on this bridge. The vaults and steps above the Breitstrom waters were my hiding places as a boy or where I crouched concealed from the wrath of my father’s open hand.

I thought we were poor to live here, our house so small and ancient, but no, despite the small leaning buildings looking into each other’s lives we were privileged. I would be happy to inherit it, as my father had from his father, if only to sell it and buy a proper home for Etta and our children. My son would not live in a box of a room with straw-packed walls and no window. Our front door would not open onto stairs to take him to a floor above a camera shop.

My father opened the door, his once blond hair now yellow and grey but still thick with vitality, like the whole of him.

‘Ernst! Etta!’ He hugged Etta and scolded me. ‘Why did you not let us know you were coming? What boy does this?’ Neither of us had a telephone. I suppose he wanted me to shout from our window. ‘We have nothing in.’ This my fault, and not true. When my parents died there would be two small plots for them and a mausoleum for their food. They were of the great war. When there were real shortages not just rationed ones. The habit of hoarding jars and cans, pickling everything, not given up. Just in case. I was born the year my father came back from the war. I stacked tins like other children stacked blocks.

The creaking stairs, my mother’s voice howling from the kitchen.

‘Etta! Ernst! Why you not let us know! My hair, Willi! My hair!’ She clutched at her head. It was in exactly the same clipped bun it had been since my youth.

I took off my hat and Etta’s coat as my mother fussed and my father reminded me that I had not joined the church football club for yet another year.

‘I am hoping I won’t have time for football soon enough.’

My mother clasped her face. ‘Oh Willi! She is pregnant! She is pregnant!’

Etta waved her down. ‘No, no, Frau Beck! The news is all for Ernst.’

‘Let them sit, Mila,’ my father pulling out glasses and Madeira. ‘What is it, Ernst? You have not signed for the army?’

The glasses to the white paper tablecloth with the cherries decoration. The same tablecloth as when I lived here. My crayon marks still on it.

‘No, Papa. Better. I have a job.’

He took our coats. ‘A draughtsman? A real job. You hear this, Mama?’

Her hands had not left her face. ‘Oh, Ernst! My boy!’ And then the hands were on my face. ‘My clever boy! When did this happen? How?’

My father poured wine. The Madeira meant it was Mama’s pickled pot roast for dinner. I cannot drink more than one glass of the sickly stuff but I would wait to see if a beer would come. Sunday after all.

‘So, you can start paying me back at last!’

‘Willi!’ My mother dropped my face. ‘Let the boy sit. Give them some wine. Let him talk.’

The wine in the thin glasses was already in our hands, Etta’s knees against mine on the small sofa, the same seat where I once put my little cars to bed before myself.

‘Topf and Sons were hiring. A junior position but—’

‘Of course. Why not?’ My father lifted his hands as if bargaining for a rug in a bazaar. ‘That is how men start. A year or two and you will have your own department.’ He slapped my knee.

My mother sat and tightened her shawl. ‘Topf, you say? My, my. Such a fine company.’

Father saluted his glass.

‘The oldest firm. The proudest. The world will open to you now. What are you working at, Ernst? Or is it secret?’ Eyed me in a way I had not seen before.

‘Why would it be secret?’

He shrugged.

‘Maybe they have some war works or such.’

I drank my syrupy wine.

‘They have contracts with the prisons. And for military parts.’

Etta touched my hand. Patted it.

‘Ernst is, unfortunately, only working on new oven designs for the camps.’ Not looking at me. At my mother. I took my hand away. ‘Unfortunately,’ she had said.

My mother’s shawl tighter.

‘The camps?’ Her voice as a whisper. ‘Buchenwald?’

‘All of them,’ I said, let Etta’s disparaging of me pass. She had suggested this visit. I thought because of pride in her husband. Maybe she had hoped a different reaction from my parents about the camp. ‘I am to work on new patents.’

‘New?’ My father nodded sagely over his glass. ‘You see, Mama? They give him new projects to work on.’ And then straight to it. ‘How much does it pay? Salary? Not week?’

‘Forty marks a week. No trial. I have already started. May I smoke, Mama?’

She stood. ‘I must get to my roast.’ I took that as yes and brought out my tobacco, and father’s pipe came from the drawer by his chair.

Etta stood.

‘Let me help you, Mila.’ And the men were alone.

An age for my father to suck his pipe into life. The sound of my childhood.

‘Ernst.’ He shook out his match into the glazed ashtray I made him at school. ‘Tell me about the ovens?’

I exhaled with him.

‘Topf created crem—’ Etta’s ear turned. ‘Created ovens for use in chapel, in ceremony. They invented the petrol oven and the gas fuelled. They export all over the world. But the prisons use coke for cost. As such I understand they need repairs. Often.’

‘Why so?’

I watched the cloud of him reach to the yellow-stained ceiling.

‘Overuse. Brick ovens. Typhus is in the prisons. Coke ovens and brick are not able to cope with the demand.’

‘So why use coke?’

‘Cost. Petrol is too expensive. Too crucial to waste on ovens. The SS are all about cost I gather.’

He leant forward.

‘The SS?’

‘You know they run the camps?’

‘I did not think they bought the ovens?’

I drew long on my cigarette. ‘Nor did I. I have learnt that much already.’

‘That is what you must do. Learn every day. Ask everything. Show that it is more than just a job. And then when they are looking for the next top man they will look for the one who shows the most interest in the company. He drummed his words out on the arm of his chair. ‘That is the way.’

‘I am doing something on that tomorrow. I am going to Buchenwald with my department head to inspect for a new oven.’ I looked to Etta not smiling at me from the kitchen.

He put his pipe on his knee.

‘You are going inside the camp?’

My mother’s voice. ‘Who is? Who is going to the camp?’

‘Ernst is, Mama,’ my father called over his shoulder. ‘Ernst is going to Buchenwald. Tomorrow.’

She came into the room, drying her hands. Always drying her hands.

‘Why? Do you have to work in the camps? That is not so good, Ernst.’

Erfurt not far from Buchenwald. The prison almost ten years old but known for disease now, for more than criminals. To my mother even the air of the place would be corrupt.

‘No, Mama. It is just to view on-site the work that we do. It will be good experience.’

Etta gone from the kitchen doorway. I heard the tap running. Running louder as my father spoke. His pipe neck pointing at me.

‘And it will show how keen you are to learn. When I worked for Littman, at the pharmacy, that man would teach me nothing. Nothing I tell you. Everything was a secret to him. I was too old to apprentice so to him I was worthless. When Quermann took it over, when a German took it over, he showed me true respect. A gentile cannot work for a Jew. You just become their chattel. I have always said it. Now it is Germany for the Germans we all look after each other. Nothing to gain but a better country for us all. Working together for the good. Not for the purse.’

Mother slapped him with her cloth that was always attached about her.

‘It was Littman who gave you that job, you old fool! Me running around scrubbing floors with Ernst in my belly and you with holes in your pockets. Quermann did not hire you. You were stolen.’ She groaned back to the kitchen. ‘That man, that man.’

I finished my wine and the bottle came back, which was a first for him.

‘All the same,’ he went on. ‘You learn from these men, Ernst. They are doing well. Government contracts. Always there is work there. When we conquer Stalin think how much work will be needed.’

‘The ovens is a small department, Papa. But they design silos and malting equipment. And gas jets and aeroplane parts. That is what I want to do.’

‘And why not? Mercedes you could work for. Build me a car for my old age. This country is for the young now. My war gave us a broken country. The Bolsheviks and the Jews conspiring to destroy us. Nothing but unemployment unless you were in their families. And now it is Germany for the Germans, the best men for the jobs, not just for the good connections. And my son has a career with one of the largest companies in the land.’ He thumped his chair. ‘This is how good life begins. I am proud of you, Ernst.’

He had not said these words since I had graduated.

Women were laughing in the kitchen, and the waft of steaming food came from rattling pots, and I would not have to ask awkwardly to borrow ten marks. I realised it could be good to visit parents.

*

We walked home arm in arm through afternoon light burnishing the wet cobblestones. I waited until the river’s rushing was behind us to ask Etta why she had called my work ‘unfortunate’.

‘I only meant that you should be doing higher things. Not drafting ovens. For the SS.’ Her head down now, moved close into me. ‘Not what I want for you.’

‘I’m sure it will not be for long.’

She stopped, looked about and took my hand.

‘But what if it is? What if it is for long? Do you not think of the ovens, Ernst? Why they need so many?’

‘The typhus. The disease. The sick. Prisons need ovens, Etta. I’ve told you this. It is unpleasant but it is fact. Would you question Paul buying a new oven?’

‘Coal ovens. Yet you tell me they order gas jets from Topf. What are they for if not for the ovens, Ernst? Do they not heat with coal?’

‘I don’t know. It is not just Topf, Etta. What company does not work with the SS now? Would you be concerned if a hospital wanted gas jets?’

She dropped my hand, put hers to my back as Klein did when he wanted me to understand something, guided me along.

‘But hospitals aren’t run by the SS, Ernst. Why are the camps run by them? Shouldn’t that be a government thing?’

The beer and wine flushed on me. A temper at defending my work. Now. Before my first pay.

‘Do you not want me to work? You were the one who wanted to go to my parents to celebrate. Now you want to deride my employers? Nothing happens in this world, Etta, unless someone sells something to someone else. Nothing.’ I walked on, left her behind me until her voice came.

‘I’m sorry, Ernst,’ she said. ‘Ernst?’ Like a charm. Holding me to the street.

I turned back to look at her framed in the sun. She walked out of it to me. Took my arm again.

‘I’m very proud of you. For you. Maybe it’s that you are going to the camp tomorrow. I’m worried. For you. I am being foolish.’

We walked on.

‘I promise you,’ I said, calm now, ‘I won’t do anything for you to worry.’

Chapter 6 (#ulink_45c0e023-dd0c-5c37-8c82-34d2e3bb3cd2)

‘Here. Put this on.’

Monday morning. We were in Hans Klein’s black Opel on the main road outside Kleinmolsen, the groan of the wipers unable to cope with the sheets of rain but Klein did not slow his speed. I could feel the water on the road hitting the panelling like waves. The tyres almost skating along. He had taken his hand off the wheel to pass me a Party pin.

It was plain tin, not enamelled. I did not question and put it on my lapel. His was enamelled and, again, as we slid along the road, he put it on with one hand.

‘It does not hurt to wear it,’ he said. ‘Gives a good impression. I am personally not political. Yourself?’

‘No, sir. I have not given it much thought.’

‘Prüfer is of course. And the Topfs. But then they would have to be dealing with the SS. Are you a union man?’

My interview had contained this question. The usual standard. ‘Are you now or have you ever been a member of the communist party?’

Who would say, ‘yes’?

‘Are not unions banned?’

He nodded, managed to light a cigarette with one hand.

‘I’m sure that some of our workers are members of the KPD. Communists. And the SDP. There was a faction of them at the factory in the 30s. I think the Buchenwald workers are influencing ours. The camp is nothing but communists. I’m sure Sander is on top of it. But keep your own ear out and let me know if you hear anything. I will make you my top boy on the floor!’ He shifted a gear down at last. ‘I cannot trust the old ones.’

The countryside blurred past. Twenty minutes in the roaring car, a super-six, and Klein showed it off. Twenty minutes. A camp a short drive from Erfurt and Weimar. I had only been in taxis before and probably only half a dozen times in my life. I did not appreciate cars, or watches, shoes and suits, but I was beginning to think that Klein thought such things impressive.

‘It is a nice car, Herr Klein.’ I looked around as if it was the Sistine Chapel, trying to admire it as we rolled across the railway line, the rail that led to the camp.

‘Twenty-five hundred marks,’ he said for reply. I imagine that is how he judged the world. The price of things. He pivoted the car between a gap in the forest with just a gear change, no brakes, and I was braced against the door.

A good gravelled road, the beech forest cut back from it with maintained grass all along. Buchenwald. Beech Tree Forest. A name for holidays. As the camp came in sight, set in a clear plain, the rain slowed, I wiped the condensation from the window, sure that I had seen men outside, outside on the grass. They were cutting the grass, had stopped to watch the car. Mowing in the rain. Their garb unmistakeable.

‘There are prisoners out there?’ I looked at him. My professor now. ‘Outside the prison?’

Klein did not even check.

‘Of course. Why not?’

‘But might they not escape?’

‘Where would they go? What would they do? Escape to starve? To be shot? Not everyone is the Count of Monte Cristo, Ernst. Some men know they belong in prison. Some men know they do not like work. Career criminals. Why escape one prison for another? Why buy your own bed and food when we can buy it for them.’ He put his arm across me to point to an outcrop of rocks not far from the barbed fence. ‘They even have a zoo. Bears, monkeys, birds of prey. You could take kids here. Although the zoo is for the guards of course. The prisoners have a cinema and theatre. A brothel for the non-Jews.’

He closed the car down the gears as we approached the gated walls. All the roads leading off the main marked by decorative wooden signs, this one, the road to the main gate designated ‘Caracho Road’ – Caracho Spanish for ‘double-time’ – decorated with four swarthy-looking men hunched and hurrying close together in prison clothes. Some of the prisoners here would have been from the Spanish war. The building like a factory except for barbed wire instead of walls. A red-timbered building like a Swiss chalet sat atop the entrance, a balcony all around, a clock above, a flagpole rising out of it. The flag just a red swathe. Beaten by the rain. Taller than this I could see the square tower of the crematoria, to the right of the gate, almost opposite the odd zoo. Not far from the main building. Good. We would not have to go deep into the camp.

Klein reached to the back seat, passed me his briefcase as we waited for the guards to come.

‘You take the notes. I will measure and photograph. I have my own Leica. Better than Sander’s Zeiss he would have you use. One hundred it cost me.’

The latticed door in the gate opened. Words were written in the iron tops but I could not make them out. They were reversed. To be read from the other side only. A black-painted slogan on the stucco wall above the gate read to those who approached:

‘RIGHT OR WRONG THIS IS MY COUNTRY.’

A grey uniform and box-cap stepped through, his jacket instantly dappled with the rain.

Klein stubbed out his cigarette.

‘You have your identification, Ernst?’ His window opened. I passed the card and Klein gave the guard his grin with our papers.

‘Good to see you again, Simon. Pity about the rain, eh?’

Simon smiled back but became stern when he looked at our cards. This was his purpose. His moment. It would be his hand that waved the gate open.

‘We are here to meet the Senior-Colonel,’ Klein said without being asked. ‘About new ovens. Another breakdown, eh?’

‘All the time.’ Simon handed back our cards. ‘Build a better one for us.’

‘Pay us more money, eh?’ Klein winked.

A circus going on around me. A joviality incongruous to what was about to happen. I was outside a prison. About to go within. I had never handed a soldier my identification before. I could only see his holster from my view in the car, another guard watching from the gate with a rifle slung. To see them so close. The shape of a gun hidden by leather a few feet from my eyes. I was in a dream. Klein knew an SS soldier’s name and had asked him for more money. An anxious dream. A little nausea, from this scene or the chicory coffee of my breakfast. Not even an oat biscuit in the house to settle my stomach.

Klein’s window closed and the gates opened. The Opel into gear. As usual he noticed or sensed everything.

‘Don’t worry, Ernst. It is quite natural to be nervous around soldiers. And prisons. You will get used to it.’ He leaned over, grinned. ‘As long as you are not forced to get used to it, eh?’

We parked on the left. There were trucks beyond the gate, waiting for their work detail and then another strange sight to add to my dream.

There was a full band in the courtyard, an orchestra almost, dressed in red trousers and green vests. Tubas and horns, even a man with a great drum on his chest like a circus parade. We got out and Klein grinned at me over the roof of the car.

‘Ah. We are in time for the band. This is good, Ernst. Every morning and evening they sing the camp song.’

I could not stop myself blinking, waking from my dream.

‘Camp song?’

‘Of course. Pride in their camp. Good for morale.’

The rain gone fully now and the brass of the band glistened from it, some of the band conscientious enough to wipe their instruments with their sleeves, proud of them, did not wipe their own faces. Their box-caps flat on their heads where they had stood in the downpour.

I flinched to the sound of loudspeakers along the fence crackling into life, the distinct sound of needle scratching record.

Trumpets and oboes blared, a fast drum beat. I would almost call it a ‘swing’ tune as the crash of cymbals came in and Zarah Leander’s voice came tinnily out.

‘To Me You’re Beautiful’ the song. I did not know if the colonel in the red-framed building knew it but this had originally been a music-hall Yiddish song. No. Maybe he did know.

The jolly song used instead of a klaxon. Hundreds of men were coming from huts like bees from a hive. The mass of them terrifying and I stepped back to the security of the steel car and Klein laughed at my reaction.

‘This is just the main camp-men. The work details. With the sub-camps there are almost sixty thousand here. Filthy. Diseased. Typhus. Do not worry, it is clean here. This is the good side.’

I could only stare. The only word for it. Stared. For such a sight. There was something familiar in it. Something I could not place. In the bones of us perhaps. Such sights.

The song came to its end, the men accustomed to timing themselves to assemble in the square before the finish, packed in the square, not an inch between them, and then a prisoner stepped from the band, came to the front. The conductor.

I was watching a conductor at eight in the morning in a prison. A captive audience of hundreds, a choir of hundreds. I began to smile myself, with Klein, to smile as at elephants or bears performing for handfuls of nuts. In absurdity. To not think how the elephants or bears are trained. It was if this were for us, for Klein and myself. But no. This happened every day. Twice a day. Their roll call. They did not even know we were here.

The band began. A martial tune, not like the record, a rousing powerful song, the type used as food for starving soldiers to forget their holed boots and damp socks. But the voices were not rousing, they were dulled and low like a warped record winding down, exactly as Zarah Leander’s wasn’t. The counter of her voice.

‘Here,’ Klein said. ‘They like this bit. Watch them stand straighter.’

It was the chorus. One line in it that came stronger than a mumble. Something on once being free from prison walls.

‘They wrote the song themselves,’ Klein tapped the roof of his car. ‘Ten marks to the composer. A competition. That is quite impressive, no? Every camp has a song. And they beat those who do not sing well enough – which is bad, but it is their song. They should sing it proud. They voted for it. Come.’

We walked away from the car and I remembered to look at the gate with the backwards writing, for those facing it on the inside.

‘TO EACH HIS OWN’.

Klein watched me read it. Saw everything. Always.

‘It means, “You get what you deserve.” And don’t we all, Ernst? At the end. And at the beginning, if you are lucky enough. And work well.’ He waved me to the stairs, to the wooden building above the gatehouse. Guards and their machine-guns walking around the balcony.

‘This is the main guard tower. We passed the commandant’s quarters along the road but Pister likes to breakfast with his men. Likes to hear the song. Walk smarter, Ernst. You are to meet a colonel!’

The marching tune ended. The roll call begun. Zarah Leander again, quieter this time for the guards to hear the names.

This like my first day at school. Bewildering, fearful. I could only think of telling Etta of it, as telling my mother of my first day with my teacher and the strange new children. The strangeness, my clothes even out of place against the stripes of prison suits, stripes of barbed wire and the gates. No walls, electric wired fences. Green freedom just beyond, in sight all around. Bears tumbling each other in a zoo. My first day.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_86684806-47e8-5926-9b19-76642ba06291)

Senior-Colonel Pister opened the chalet door himself. I did not know what I expected but not the portly, white-haired man in red sweater and red braces above his SS trousers. If it were not April, if not for his lack of beard, I might have just met St Nick.

A wood stove, the smell of coffee and bacon warming the room. I was jarred for a moment, almost hiding behind Klein as Pister welcomed us against the sound of names being barked in the square below.

Pister’s arms opened wide as if to embrace.

‘How are you, Hans?’

‘Very well, Colonel.’

Klein negated, defeated, Pister’s open arms with a handshake, his left hand on Pister’s arm, drawing Pister’s hand into the shake. ‘I am so glad we managed to catch the song.’

The ‘we’ directed to me and that was how I was introduced and how I realised Klein controlled rooms. He did not wait for Pister to ask who he had brought, he did not reciprocate Pister’s embrace but initiated his own and I tried to recall if he had done the same to me, and then I saw that his hand was on Pister’s back, gently, and this I recalled, and the pace up the stairs on my first day. Keep up, keep up.