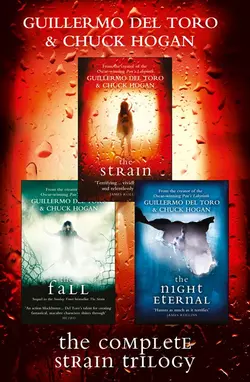

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Guillermo Del Toro

High-concept thrillers with a supernatural edge from world-famous director, whose films include Pan’s Labyrinth and Hellboy. Now a popular Amazon TV Show.

THE STRAIN: A plane lands at JFK and mysteriously ‘goes dark’, stopping in the middle of the runway for no apparent reason, all lights off, all doors sealed. The pilots cannot be raised.

When the hatch above the wing finally clicks open, it soon becomes clear that everyone on board is dead – although there is no sign of any trauma or struggle. Ephraim Goodweather and his team from the Center for Disease Control must work quickly to establish the cause of this strange occurrence before panic spreads.

THE FALL: Humans have been displaced at the top of the food chain, and now understand – to their outright horror – what it is to be not the consumer, but the consumed.

Ephraim Goodweather, director of the New York office of the Centers for Disease control, is one of the few humans who understands what is really happening. Vampires have arrived in New York City, and their condition is contagious. If they cannot be contained, the entire world is at risk of infection…

THE NIGHT ETERNAL: After the blasts, it was all over. Nuclear Winter has settled upon the earth. Except for one hour of sunlight a day, the whole world is plunged into darkness. It is a near-perfect environment for vampires. They have won. It is their time.

Almost every single man, woman and child has been enslaved in vast camps across the globe. Like animals, they are farmed, harvested for the sick pleasure of the Master Race.

Almost, but not all. Somewhere out there, hiding for their lives, is a desperate network of free humans, continue the seemingly hopeless resistance. Everyday people, with no other options – among them Dr Ephraim Goodweather, his son Zack, the veteran exterminator Vassily, and former gangbanger Gus.

To be free, they need a miracle, they need divine intervention. But Salvation can be a twisted game – one in which they may be played like pawns in a battle of Good and Evil. And at what cost…?

The Strain Trilogy

GUILLERMO DEL TORO and CHUCK HOGAN

Contents

Title Page (#u02c8317d-2FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The Strain

The Fall

The Night Eternal

About the Authors (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Authors (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#u02c8317d-3FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The Strain (#u02c8317d-3FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

BOOK I

OF The Strain Trilogy

GUILLERMO DEL TORO and CHUCK HOGAN

Dedication (#)

To Lorenza, Mariana, and Marisa …

and

to all the monsters in my nursery:

May you never leave me alone

—GDT

For Lila

—CH

Contents

Cover (#u02c8317d-4FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

Title Page (#u02c8317d-5FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

Dedication (#u02c8317d-8FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The Legend of Jusef Sardu

The Beginning (#)

N323RG Cockpit Voice Recorder (#)

The Landing (#)

JFK International Control Tower

Now Boarding (#)

Worth Street, Chinatown

Interlude I: Abraham Setrakian

Arrival (#)

Regis Air Maintenance Hangar

Occultation (#)

Approaching Totality (#)

Awakening (#)

Regis Air Maintenance Hangar (#)

Interlude II: The Burning Hole (#)

Movement (#)

Coach (#)

The First Night (#)

Interlude III: Revolt, 1943 (#)

Dawn (#)

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan (#)

The Old Professor (#)

Knickerbocker Loans and Curios, East 118th Street, Spanish Harlem (#)

The Second Night (#)

Exposure (#)

Canary Headquarters, Eleventh Avenue and Twenty-seventh Street (#)

Final Interlude: The Ruins (#)

Replication (#)

Jamaica Hospital Medical Center (#)

Daylight (#)

Bushwick, Brooklyn (#)

Lair (#)

Worth Street, Chinatown (#)

The Clan (#)

Nazareth, Pennsylvania (#)

Epilogue: Kelton Street, Woodside, Queens (#)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

The Legend of Jusef Sardu (#u02c8317d-9FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

“Once upon a time,” said Abraham Setrakian’s grandmother, “there was a giant.”

Young Abraham’s eyes brightened, and immediately the cabbage borscht in the wooden bowl got tastier, or at least less garlicky. He was a pale boy, underweight and sickly. His grandmother, intent on fattening him, sat across from him while he ate his soup, entertaining him by spinning a yarn.

A bubbeh meiseh, a “grandmother’s story.” A fairy tale. A legend.

“He was the son of a Polish nobleman. And his name was Jusef Sardu. Master Sardu stood taller than any other man. Taller than any roof in the village. He had to bow deeply to enter any door. But his great height, it was a burden. A disease of birth, not a blessing. The young man suffered. His muscles lacked the strength to support his long, heavy bones. At times it was a struggle for him just to walk. He used a cane, a tall stick—taller than you—with a silver handle carved into the shape of a wolf’s head, which was the family crest.”

“Yes, Bubbeh?” said Abraham, between spoonfuls.

“This was his lot in life, and it taught him humility, which is a rare thing indeed for a nobleman to possess. He had so much compassion—for the poor, for the hardworking, for the sick. He was especially dear to the children of the village, and his great, deep pockets—the size of turnip sacks—bulged with trinkets and sweets. He had not much of a childhood himself, matching his father’s height at the age of eight, and surpassing him by a head at age nine. His frailty and his great size were a secret source of shame to his father. But Master Sardu truly was a gentle giant, and much beloved by his people. It was said of him that Master Sardu looked down on everyone, yet looked down on no one.”

She nodded at him, reminding him to take another spoonful. He chewed a boiled red beet, known as a “baby heart” because of its color, its shape, its capillary-like strings. “Yes, Bubbeh?”

“He was also a lover of nature, and had no interest in the brutality of the hunt—but, as a nobleman and a man of rank, at the age of fifteen his father and his uncles prevailed upon him to accompany them on a six-week expedition to Romania.”

“To here, Bubbeh?” said Abraham. “The giant, he came here?”

“To the north country, kaddishel. The dark forests. The Sardu men, they did not come to hunt wild pig or bear or elk. They came to hunt wolf, the family symbol, the arms of the house of Sardu. They were hunting a hunting animal. Sardu family lore said that eating wolf meat gave Sardu men courage and strength, and the young master’s father believed that this might cure his son’s weak muscles.”

“Yes, Bubbeh?”

“Their trek was long and arduous, as well as violently opposed by the weather, and Jusef struggled mightily. He had never before traveled anywhere outside his family’s village, and the looks he received from strangers along the journey shamed him. When they arrived in the dark forest, the woodlands felt alive around him. Packs of animals roamed the woods at night, almost like refugees displaced from their shelters, their dens, nests, and lairs. So many animals that the hunters were unable to sleep at night in their camp. Some wanted to leave, but the elder Sardu’s obsession came before all else. They could hear the wolves, crying in the night, and he wanted one badly for his son, his only son, whose gigantism was a pox upon the Sardu line. He wanted to cleanse the house of Sardu of this curse, to marry off his son, and produce many healthy heirs.

“And so it was that his father, off tracking a wolf, was the first to become separated from the others, just before nightfall on the second evening. The rest waited for him all night, and spread out to search for him after sunrise. And so it was that one of Jusef’s cousins failed to return that evening. And so on, you see.”

“Yes, Bubbeh?”

“Until the only one left was Jusef, the boy giant. That next day he set out, and in an area previously searched, discovered the body of his father, and of all his cousins and uncles, laid out at the entrance to an underground cave. Their skulls had been crushed with great force, but their bodies remained uneaten—killed by a beast of tremendous strength, yet not out of hunger or fear. For what reason, he could not guess—though he did feel himself being watched, perhaps even studied, by some being lurking within that dark cave.

“Master Sardu carried each body away from the cave and buried them deep. Of course, this exertion severely weakened him, taking most of his strength. He was spent, he was farmutshet. And yet, alone and scared and exhausted, he returned to the cave that night, to face what evil revealed itself after dark, to avenge his forebears or die trying. This is known from a diary he kept, discovered in the woods many years later. This was his last entry.”

Abraham’s mouth hung empty and open. “But what happened, Bubbeh?”

“No one truly knows. Back at home, when six weeks stretched to eight, and ten, with no word, the entire hunting party was feared lost. A search party was formed and found nothing. Then, in the eleventh week, one night a carriage with curtained windows arrived at the Sardu estate. It was the young master. He secluded himself inside the castle, inside a wing of empty bedrooms, and was rarely, if ever, seen again. At that time, only rumors followed him back, about what had happened in the Romanian forest. A few who did claim to see Sardu—if indeed any of these accounts could be believed—insisted that he had been cured of his infirmities. Some even whispered that he had returned possessed of great strength, matching his superhuman size. Yet so deep was Sardu’s mourning for his father and his uncles and cousins, that he was never again seen about during work hours, and discharged most of his servants. There was movement about the castle at night—hearth fires could be seen glowing in windows—but over time, the Sardu estate fell into disrepair.

“But at night … some claimed to hear the giant walking about the village. Children, especially, passed the tale of hearing the pick-pick-pick of his walking stick, which Sardu no longer relied upon but used to call them out of their night beds for trinkets and treats. Disbelievers were directed to holes in the soil, some outside bedroom windows, little poke marks as from his wolf-handled stick.”

His bubbeh’s eyes darkened. She glanced at his bowl, seeing that most of the soup was gone.

“Then, Abraham, some peasant children began to disappear. Stories went around of children vanishing from surrounding villages as well. Even from my own village. Yes, Abraham, as a girl your bubbeh grew up just a half-day’s walk from Sardu’s castle. I remember two sisters. Their bodies were found in a clearing of the woods, as white as the snow surrounding them, their open eyes glazed with frost. I myself, one night, heard not too distantly the pick-pick-pick—such a powerful, rhythmic noise—and pulled my blanket fast over my head to block it out, and didn’t sleep again for many days.”

Abraham gulped down the end of the story with the remains of his soup.

“Much of Sardu’s village was eventually abandoned and became an accursed place. The Gypsies, when their carriage train passed through our town, told of strange happenings, of hauntings and apparitions near the castle. Of a giant who prowled the moonlit land like a god of the night. It was they who warned us, ‘Eat and grow strong—or else Sardu will get you.’ Why it is important, Abraham. Ess gezunterhait! Eat and be strong. Scrape that bowl now. Or else—he will come.” She had come back from those few moments of darkness, of remembering. Her eyes came back to their lively selves. “Sardu will come. Pick-pick-pick.”

And finish he did, every last remaining beet string. The bowl was empty and the story was over, but his belly and his mind were full. His eating pleased his bubbeh, and her face was, for him, as clear an expression of love that existed. In these private moments at the rickety family table, they communed, the two of them, sharing food of the heart and the soul.

A decade later, the Setrakian family would be driven from their woodwork shop and their village, though not by Sardu. A German officer was billeted in their home, and the man, softened by his hosts’ utter humanity, having broken bread with them over that same wobbly table, one evening warned them not to follow the next day’s order to assemble at the train station, but to leave their home and their village that very night.

Which they did, the entire extended family together—all eight of them—journeying into the countryside with as much as they could carry. Bubbeh slowed them down. Worse—she knew that she was slowing them down, knew that her presence placed the entire family at risk, and cursed herself and her old, tired legs. The rest of the family eventually went on ahead, all except for Abraham—now a strong young man and full of promise, a master carver at such a young age, a scholar of the Talmud, with a special interest in the Zohar, the secrets of Jewish mysticism—who stayed behind, at her side. When word reached them that the others had been arrested at the next town, and had to board a train for Poland, his bubbeh, wracked with guilt, insisted that, for Abraham’s sake, she be allowed to turn herself in.

“Run, Abraham. Run from the Nazi. As from Sardu. Escape.”

But he would not have it. He would not be separated from her.

In the morning he found her on the floor of the room they had shared—in the house of a sympathetic farmer—having fallen off in the night, her lips charcoal black and peeling and her throat black through her neck, dead from the animal poison she had ingested. With his host family’s gracious permission, Abraham Setrakian buried her beneath a flowering silver birch. Patiently, he carved her a beautiful wooden marker, full of flowers and birds and all the things that had made her happiest. And he cried and cried for her—and then run he did.

He ran hard from the Nazis, hearing a pick-pick-pick all the time at his back …

And evil followed closely behind.

THE BEGINNING (#)

N323RG Cockpit Voice Recorder (#)

Excerpts, NTSB transcription, Flight 753, Berlin (TXL) to New York (JFK), 9/24/10:

2049:31 [Public-address microphone is switched ON.]

CAPT. PETER J. MOLDES: “Ah, folks, this is Captain Moldes up in the flight deck. We should be touching down on the ground in a few minutes for an on-time arrival. Just wanted to take a moment and let you know we certainly ’preciate you choosing Regis Airlines, and that, on behalf of First Officer Nash and myself and your cabin crew, hope you come back and travel with us again real soon …”

2049:44 [Public-address microphone is switched OFF.]

CAPT. PETER J. MOLDES: “… so we can all keep our jobs.” [cockpit laughter]

2050:01 Air-traffic control New York (JFK): “Regis 7-5-3 heavy, approaching left, heading 1-0-0. Clear to land on 13R.”

CAPT. PETER J. MOLDES: “Regis 7-5-3 heavy, approaching left, 1-0-0, landing on runway 13R, we have it.”

2050:15 [Public-address microphone is switched ON.]

CAPT. PETER J. MOLDES: “Flight attendants, prepare for landing.”

2050:18 [Public-address microphone is switched OFF.]

FIRST OFFICER RONALD W. NASH IV: “Landing gear clear.”

CAPT. PETER J. MOLDES: “Always nice coming home …”

2050:41 [Banging noise. Static. High-pitched noise.]

END OF TRANSMISSION

THE LANDING (#)

JFK International Control Tower (#)

The dish, they called it. Glowing green monochrome (JFK had been waiting for new color screens for more than two years now), like a bowl of pea soup supplemented with clusters of alphabet letters tagged to coded blips. Each blip represented hundreds of human lives, or, in the old nautical parlance that endured in air travel to this day, souls.

Hundreds of souls.

Perhaps that was why all the other air-traffic controllers called Jimmy Mendes “Jimmy the Bishop.” The Bishop was the only ATC who spent his entire eight-hour shift standing rather than sitting, wielding a number 2 pencil in his hand and pacing back and forth, talking commercial jets into New York from the busy tower cab 321 feet above John F. Kennedy International Airport like a shepherd tending his flock. He used the pink pencil eraser to visualize the aircraft under his command, their positions relative to one another, rather than relying exclusively upon his two-dimensional radar screen.

Where hundreds of souls beeped every second.

“United 6-4-2, turn right heading 1-0-0, climb to five thousand.”

But you couldn’t think like that when you were on the dish. You couldn’t dwell on all those souls whose fates rested under your command: human beings packed inside winged missiles rocketing miles above the earth. You couldn’t big-picture it: all the planes on your dish, and then all the other controllers muttering coded headset conversations around you, and then all of the planes on their dishes, and then the ATC tower over at neighboring LaGuardia … and then all the ATC towers of every airport in every city in the United States … and then all across the world …

Calvin Buss, the air-traffic-control area manager and Jimmy the Bishop’s immediate supervisor, appeared at his shoulder. He was back early from a break, in fact, still chewing his food. “Where are you with Regis 7-5-3?”

“Regis 7-5-3 is home.” Jimmy the Bishop took a quick, hot look at his dish to confirm. “Proceeding to gate.” He scrolled back his gate-assignment roster, looking for 7-5-3. “Why?”

“Ground radar says we have an aircraft stalled on Foxtrot.”

“The taxiway?” Jimmy checked his dish again, making sure all his bugs were good, then reopened his channel to DL753. “Regis 7-5-3, this is JFK tower, over.”

Nothing. He tried again.

“Regis 7-5-3, this is JFK tower, come in, over.”

He waited. Nothing, not even a radio click.

“Regis 7-5-3, this is JFK tower, are you reading me, over.”

A traffic assistant materialized behind Calvin Buss’s shoulder. “Comm problem?” he suggested.

Calvin Buss said, “Gross mechanical failure, more likely. Somebody said the plane’s gone dark.”

“Dark?” said Jimmy the Bishop, marveling at what a near miss that would be, the aircraft’s gross mechanicals shitting the bed just minutes after landing. He made a mental note to stop off on the way home and play 753 for tomorrow’s numbers.

Calvin plugged his own earphone into Jimmy’s b-comm audio jack. “Regis 7-5-3, this is JFK tower, please respond. Regis 7-5-3, this is the tower, over.”

Waiting, listening.

Nothing.

Jimmy the Bishop eyed his pending blips on the dish—no conflict alerts, all his aircraft okay. “Better advise on a reroute around Foxtrot,” he said.

Calvin unplugged and stepped back. He got a middle-distance look in his eyes, staring past Jimmy’s console to the windows of the tower cab, out in the general direction of the taxiway. His look showed as much confusion as concern. “We need to get Foxtrot cleared.” He turned to the traffic assistant. “Dispatch somebody for a visual.”

Jimmy the Bishop clutched his belly, wishing he could reach inside and somehow massage the sickness roiling at its pit. His profession, essentially, was midwifery. He assisted pilots in delivering planes full of souls safely out of the womb of the void and unto the earth. What he felt now were pangs of fear, like those of a young doctor having delivered his very first stillborn.

Terminal 3 Tarmac

LORENZA RUIZ was on her way out to the gate, driving a baggage conveyor, basically a hydraulic ramp on wheels. When 753 didn’t show around the corner as expected, Lo rolled out farther for a little peek, as she was due her break soon. She wore protective headphones, a Mets hoodie underneath her reflective vest, goggles—that runway grit was a bitch—with her orange marshaling batons lying next to her hip, on the seat.

What in the hell?

She pulled off her goggles as though needing to see it with her bare eyes. There it was, a Regis 777, a big boy, one of the new ones on the fleet, sitting out on Foxtrot in darkness. Total darkness, even the nav lights on the wings. All she saw was the smooth, tubular surface of the fuselage and wings glowing faintly under the landing lights of approaching planes. One of them, Lufthansa 1567, missing a collision with its landing gear by a mere foot.

“Jesus Santisimo!”

She called it in.

“We’re already on our way,” said her supervisor. “Crow’s nest wants you to roll out and take a look.”

“Me?” Lo said.

She frowned. That’s what you get for curiosity. So she went, following the service lane out from the passenger terminal, crossing the taxiway lines painted onto the apron. She was a little nervous, and very watchful, having never driven out this far before. The FAA had strict rules about how far out the conveyors and baggage trailers were supposed to go.

She turned past the blue guide lamps edging the taxiway. The plane appeared to have been shut down completely, stem to stern. No beacon light, no anticollision light, no lights in the cabin windows. Usually, even from the ground, thirty feet below, through the tiny windshield like eyes slanting over the characteristic Boeing nose, you could see up and inside the cockpit, the overhead switch panel and the instrument lights glowing darkroom red. But there were no lights at all.

Lo idled ten yards back from the tip of the long left wing. You work the tarmac long enough—Lo had eight years in now, longer than both of her marriages put together—you pick up a few things. The trailing edge flaps and the ailerons—the spoiler panels on the back sides of the wings—were all straight up like Paula Abdul, which is how pilots set them after runway touchdown. The turbojets were quiet and still, and they usually took a while to stop chewing air even after switch off, sucking in grit and bugs like great ravenous vacuums. So this big baby had come in clean and set down all nice and easy and gotten this far before—lights out.

Even more alarmingly, if it had been cleared for landing, whatever had gone wrong happened in the space of two, maybe three minutes. What can go wrong that fast?

Lo pulled a little bit closer, rolling in behind the wing. If those turbofans were to start up all of a sudden, she didn’t want to get sucked in and shredded like some Canadian goose. She drove near the freight hold, the area of the plane she was best acquainted with, down toward the tail, stopping beneath the rear exit door. She set the locking brake and worked the stick that raised her ramp, which at its height topped out at about a thirty-degree incline. Not enough, but still. She got out, reached back in for her batons, and walked up the ramp toward the dead airplane.

Dead? Why did she think that? The thing had never been alive—

But for a moment, Lorenza thought of the image of a large, rotting corpse, a beached whale. That was what the plane looked like to her: a festering carcass; a dying leviathan.

The wind stopped as she neared the top, and you have to understand one thing about the climate out on the apron at JFK: the wind never stops. As in never ever. It is always windy out on the tarmac, with the planes coming in and the salt marsh and the friggin’ Atlantic Ocean just on the other side of Rockaway. But all of a sudden it got real silent—so silent that Lo pulled down her big-muff headphones, just to be certain. She thought she heard pounding coming from inside the plane, but realized it was just the beating of her own heart. She turned on her flashlight and trained it on the right flank of the plane.

Following the circular splash of her beam, she could see that the fuselage was still slick and pearly from its descent, smelling like spring rain. She shined her light on the long row of windows. Every interior shade was pulled down.

That was strange. She was spooked now. Majorly spooked. Dwarfed by a massive, $250-million, 383-ton flying machine, she had a fleeting yet palpable and cold sensation of standing in the presence of a dragonlike beast. A sleeping demon only pretending to be asleep, yet capable, at any moment, of opening its eyes and its terrible mouth. An electrically psychic moment, a chill running through her with the force of a reverse orgasm, everything tightening, knotting up.

Then she noticed that one of the shades was up now. The fine hairs went so prickly on the back of her neck, she put her hand there to console them, like soothing a jumpy pet. She had missed seeing that shade before. It had always been up—always.

Maybe …

Inside the plane, the darkness stirred. And Lo felt as if something were observing her from within it.

She whimpered, just like a child, but couldn’t help it. She was paralyzed. A throbbing rush of blood, rising as though commanded, tightened her throat …

And she understood it then, unequivocally: something in there was going to eat her …

The gusting wind started up again, as though it had never paused, and Lo didn’t need any more prompting. She backed down the ramp and jumped inside her conveyor, putting it in reverse with the alert beeping and her ramp still up. The crunching noise was one of the blue taxiway lights beneath her treads as she sped away, half on and half off the grass, toward the approaching lights of half a dozen emergency vehicles.

JFK International Control Tower

CALVIN BUSS had switched to a different headset, and was giving orders as set forth in the FAA national playbook for taxiway incursions. All arrivals and departures were halted in a five-mile airspace around JFK. This meant that volume was stacking up fast. Calvin canceled breaks and ordered every on-shift controller to try to raise Flight 753 on every available frequency. It was as close to chaos in the JFK tower as Jimmy the Bishop had ever seen.

Port Authority officials—guys in suits muttering into Nextels—gathered at his back. Never a good sign. Funny how people naturally assemble when faced with the unexplained.

Jimmy the Bishop tried his call again, to no avail.

One suit asked him, “Hijack signal?”

“No,” said Jimmy the Bishop. “Nothing.”

“No fire alarm?”

“Of course not.”

“No cockpit door alarm?” said another.

Jimmy the Bishop saw that they had entered the “stupid questions” phase of the investigation. He summoned the patience and good judgment that made him a successful air-traffic controller. “She came in smooth and set down soft. Regis 7-5-3 confirmed the gate assignment and turned off the runway. I terminated radar and transitioned it over to ASDE.”

Calvin said, one hand over his earphone mic, “Maybe the pilot had to shut down?”

“Maybe,” said Jimmy the Bishop. “Or maybe it shut down on him.”

A suit said, “Then why haven’t they opened a door?”

Jimmy the Bishop’s mind was already spinning on that. Passengers, as a rule, won’t sit still for a minute longer than they had to. The previous week, a jetBlue arriving from Florida had very nearly undergone a mutiny, and that was over stale bagels. Here, these people had been sitting tight for, what—maybe fifteen minutes. Completely in the dark.

Jimmy the Bishop said, “It’s got to be starting to get hot in there. If the electrical is shut down, there’s no air circulating inside. No ventilation.”

“So what the hell are they waiting for?” said another suit.

Jimmy the Bishop felt everyone’s anxiety going up. That hole in your gut when you realize that something is about to happen, something really, really wrong.

“What if they can’t move?” he muttered before he could stop himself from speaking.

“A hostage situation? Is that what you mean?” asked the suit.

The Bishop nodded quietly … but he wasn’t thinking that. For whatever reason, all he could think was … souls.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE PORT AUTHORITY’S aircraft rescue firefighters went out on a standard airliner distress deployment, six vehicles including the fuel spill foamer, pumper, and aerial ladder truck. They pulled up at the stuck baggage conveyor before the blue lamps edging Foxtrot. Captain Sean Navarro hopped off the back step of the ladder truck, standing there in his helmet and fire suit before the dead plane. The rescue vehicles’ lights flashing against the fuselage imbued the aircraft with a fake red pulse. It looked like an empty plane set out for a nighttime training drill.

Captain Navarro went up to the front of the truck and climbed in with the driver, Benny Chufer. “Call in to maintenance and get those staging lights out here. Then pull up behind the wing.”

Benny said, “Our orders are to hang back.”

Captain Navarro said, “That’s a plane full of people there. We’re not paid to be glorified road flares. We’re paid to save lives.”

Benny shrugged and did as the cap told him. Captain Navarro climbed back out of the rig and up onto the roof, and Benny raised the boom just enough to get him up on the wing. Captain Navarro switched on his flashlight and stepped over the trailing edge between the two raised flaps, his boot landing right where it said, in bold black lettering, DON’T STEP HERE.

He walked along the broadening wing, twenty feet above the tarmac. He went to the over-wing exit, the only door on the aircraft installed with an exterior emergency release. There was a small, unshaded window set in the door, and he tried to peer through, past the beads of condensation inside the double-thick glass, seeing nothing inside except more darkness. It had to be as stifling as an iron lung in there.

Why weren’t they calling out for help? Why wasn’t he hearing any movement inside? If still pressurized, then the plane was airtight. Those passengers were running out of oxygen.

With his fire gloves on, he pushed in the twin red flaps and pulled the door handle out from its recess. He rotated it in the direction of the arrows, nearly 180 degrees, and tugged. The door should have popped outward then, but it would not open. He pulled again, but knew immediately that his effort was useless—no give whatsoever. There was no way it could have been stuck from the inside. The handle must have jammed. Or else something was holding it from the inside.

He went back down wing to the ladder top. He saw an orange utility light spinning, an airport cart on its way out from the international terminal. Closer, he saw it was driven by blue-jacketed agents of the Transportation Security Administration.

“Here we go,” muttered Captain Navarro, starting down the ladder.

There were five of them, each one introducing himself in turn, but Captain Navarro didn’t waste any effort trying to remember names. He had come to the plane with fire engines and foaming equipment; they came with laptops and mobile handhelds. For a while he just stood and listened while they talked into their devices and over each other:

“We need to think long and hard before we push the Homeland Security button here. Nobody wants a shit storm for nothing.”

“We don’t even know what we have. You ring that bell and scramble fighters up here from Otis Air Force Base, you’re talking about panicking the entire eastern seaboard.”

“If it is a bomb, they waited until the last possible moment.”

“Explode it on U.S. soil, maybe.”

“Maybe they’re playing dead for a while. Staying radio dark. Luring us closer. Waiting for the media.”

One guy was reading from his phone. “I have the flight originating from Tegel, in Berlin.”

Another spoke into his. “I want someone on the ground in Germany who sprechen ze English. We need to know if they’ve seen any suspicious activity there, any breaches. Also, we need a primer on their baggage-handling procedures.”

Another ordered: “Check the flight plan and reclear the passenger manifest. Yes—every name, run them again. This time accounting for spelling variations.”

“Okay,” said another, reading from his handheld. “Full specs. Plane reg is N323RG. Boeing 777–200LR. Most recent transit check was four days ago, at Atlanta Hartsfield. Replaced a worn duct slider on the left engine’s thrust reverser, and a worn mount bushing on the right. Deferred repair of a dent in the left-aft inboard flap assembly due to flight schedule. Bottom line—she got a clean bill of health.”

“Triple sevens are new orders, aren’t they? A year or two out?”

“Three hundred and one max capacity. This flight boarded two ten. A hundred and ninety-nine passengers, two pilots, nine cabin crew.”

“Any unticketed?” That meant infants.

“I’m showing no.”

“Classic tactic,” said the one focused on terror. “Create a disturbance, draw first responders, gain an audience—then detonate for max impact.”

“If so, then we’re already dead.”

They looked at each other uncomfortably.

“We need to pull these rescue vehicles back. Who was that fool up there stomping on the wing?”

Captain Navarro edged forward, surprising them with a response. “That was me.”

“Ah. Well.” The guy coughed once into his fist. “That’s maintenance personnel only up there, Captain. FAA regs.”

“I know it.”

“Well? What’d you see? Anything?”

Navarro said, “Nothing. Saw nothing, heard nothing. All the window shades are drawn down.”

“Drawn down, you say? All of them?”

“All of them.”

“Did you try the over-wing exit?”

“I did indeed.”

“And?”

“It was stuck.”

“Stuck? That’s impossible.”

“It’s stuck,” said Captain Navarro, showing more patience with these five than he did with his own kids.

The senior man stepped away to make a call. Captain Navarro looked at the others. “So what are we going to do here, then?”

“That’s what we’re waiting to find out.”

“Waiting to find out? You have how many passengers on this plane? How many 911 calls have they made?”

One man shook his head. “No mobile 911 calls from the plane yet.”

“Yet?” said Captain Navarro.

The guy next to him said, “Zero for one-ninety-nine. Not good.”

“Not good at all.”

Captain Navarro looked at them in amazement. “We have to do something, and now. I don’t need permission to grab a fire ax and start smashing in windows when people are dead or dying in there. There is no air inside that plane.”

The senior man came back from his phone call. “They’re bringing out the torch now. We’re cutting her open.”

Dark Harbor, Virginia

CHESAPEAKE BAY, black and churning at that late hour.

Inside the glassed-in patio of the main house, on a scenic bluff overlooking the bay, a man reclined in a specially made medical chair. The lights were dimmed for his comfort as well as for modesty. The industrial thermostats, of which there were three for this room alone, maintained a temperature of sixty-two degrees Fahrenheit. Stravinsky played quietly, The Rite of Spring, piped in through discreet speakers to obscure the relentless shushing pump of the dialysis machine.

A faint plume of breath emerged from his mouth. An onlooker might have believed the man near death. Might have thought they were witnessing the last days or weeks of what was, judging by the sprawling seventeen-acre estate, a dramatically successful life. Might even have remarked on the irony of a man of such obvious wealth and position meeting the same end as a pauper.

Only, Eldritch Palmer was not at the end. He was in his seventy-sixth year, and he had no intention of giving up on anything. Nothing at all.

The esteemed investor, businessman, theologian, and high-powered confidant had been undergoing the same procedure for three to four hours every evening for the past seven years of his life. His health was frail and yet manageable, overseen by round-the-clock physicians and aided by hospital-grade medical equipment purchased for his private, in-home use.

Wealthy people can afford excellent health care, and they can also afford to be eccentric. Eldritch Palmer kept his peculiarities hidden from public view, even from his inner circle. The man had never married. He had never sired an heir. And so a major topic of speculation about Palmer was what plans he might have for his vast fortune after his death. He had no second-in-command at his primary investment entity, the Stoneheart Group. He had no public affiliation with any foundations or charities, unlike the two men jockeying for number one with him on the annual Forbes list of the world’s richest Americans, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and Berkshire Hathaway investor Warren Buffett. (If certain gold reserves in South America and other holdings by shadow corporations in Africa were factored into Forbes’s accounting, Palmer alone would hold the top spot on the list.) Palmer had never even drafted a will, an estate-planning lapse unthinkable for a man with even one one-thousandth of his wealth and treasure.

But Eldritch Palmer was, quite simply, not planning to die.

Hemodialysis is a procedure in which blood is removed from the body through a system of tubing, ultrafiltered through a dialyzer, or artificial kidney, and then returned to the body cleansed of waste products and impurities. Ingoing and outgoing needles are inserted into a synthetic arteriovenous graft semipermanently installed in the forearm. The machine for this procedure was a state-of-the-art Fresenius model, continuously monitoring Palmer’s critical parameters and alerting Mr. Fitzwilliam, never more than two rooms away, of any readings outside the normal range.

Loyal investors were accustomed to Palmer’s perpetually gaunt appearance. It had essentially become his trademark, an ironic symbol of his monetary strength, that such a delicate, ashen-looking man should wield such power and influence in both international finance and politics. His legion of faithful investors numbered thirty thousand strong, a financially elite bloc of people: the buy-in was two million dollars, and many who had invested with Palmer for decades were worth mid-nine figures. The buying power of his Stoneheart Group gave him enormous economic leverage, which he put to effective and occasionally ruthless use.

The west doors opened from the wide hallway, and Mr. Fitzwilliam, who doubled as the head of Palmer’s personal security detail, entered with a portable, secure telephone on a sterling-silver serving tray. Mr. Fitzwilliam was a former U.S. Marine with forty-two confirmed combat kills and a quick mind, whose postmilitary medical schooling Palmer had financed. “The undersecretary for Homeland Security, sir,” he said, with a plume of breath steaming in the cold room.

Normally Palmer allowed no intrusions during his nightly replenishment, preferring instead to use the time contemplatively. But this was a call he had been expecting. He accepted the telephone from Mr. Fitzwilliam, and waited for him to dutifully withdraw.

Palmer answered, and was informed about the dormant airplane. He learned that there was considerable uncertainty as to how to proceed by officials at JFK. The caller spoke anxiously, with self-conscious formality, like a proud child reporting a good deed. “This is a highly unusual event, and I thought you’d want to be apprised immediately, sir.”

“Yes,” Palmer told the man. “I do appreciate such courtesy.”

“Ha-have a good night, sir.”

Palmer hung up and set the phone down in his small lap. A good night indeed. He felt a pang of anticipation. He had been expecting this. And now that the plane had landed, he knew it had begun—and in what spectacular fashion.

Excitedly, he turned to the large-screen television on the side wall and used the remote control on the arm of his chair to activate the sound. Nothing about the airplane yet. But soon …

He pressed the button on an intercom. Mr. Fitzwilliam’s voice said, “Yes, sir?”

“Have them ready the helicopter, Mr. Fitzwilliam. I have some business to attend to in Manhattan.”

Eldritch Palmer rang off, then looked through the wall of windows out over the great Chesapeake Bay, roiling and black, just south of where the steely Potomac emptied into her dark depths.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE MAINTENANCE CREW wheeled oxygen tanks underneath the fuselage. Cutting in was an emergency procedure of last resort. All commercial aircraft were constructed with specified “chop-out” areas. The triple seven’s chop out was in the rear fuselage, beneath the tail, between the aft cargo doors on the right side. The LR in Boeing 777–200LR stood for long range, and as a C-market model with a top range exceeding 9,000 nautical miles (nearly 11,000 U.S.) and a fuel capacity of up to 200,000 liters (more than 50,000 gallons), the aircraft had, in addition to the traditional fuel tanks inside the wing bodies, three auxiliary tanks in the rear cargo hold—thus the need for a safe chop-out area.

The maintenance crew was using an Arcair slice pack, an exothermic torch favored for disaster work not only because it was highly portable, but because it was also oxygen powered, using no hazardous secondary gases such as acetylene. The work of cutting through the thick fuselage shell would take about one hour.

No one on the tarmac at this point was anticipating a happy outcome. There had been no 911 calls from passengers inside the aircraft. No light, noise, or signal of any kind emanating from inside Regis 753. The situation was mystifying.

A Port Authority emergency services unit mobile-command vehicle was cleared through to the terminal apron, set up behind powerful construction lights trained on the jet. Their SWAT team was trained for evacuations, hostage rescue, and antiterrorism assaults on the bridges, tunnels, bus terminals, airports, PATH rail lines, and seaports of New York and New Jersey. Tactical officers were outfitted with light body armor and Heckler-Koch submachine guns. A pair of German shepherds were out sniffing around the main landing gear—two sets of six enormous tires—trotting around with their noses in the air as if they could smell the trouble here too.

Captain Navarro wondered for a moment if anyone was actually still on board. Hadn’t there been a Twilight Zone where a plane landed empty?

The maintenance crew sparked up the torches and was just starting in on the underside of the hull when one of the canines started howling. The dog was baying, actually, and spinning around and around on his leash in tight circles.

Captain Navarro saw his ladder man, Benny Chufer, pointing up at the midsection of the aircraft. A thin, black shadow appeared before his eyes. A vertical slash of darkest black, disrupting the perfectly smooth breast of the fuselage.

The exit door over the wing. The one Captain Navarro hadn’t been able to budge.

It was open now.

It made no sense to him, but Navarro kept quiet, struck dumb by the sight. Maybe a latch failure, a malfunction in the handle … maybe he had not tried hard enough … or maybe—just maybe—someone had finally opened the door.

JFK International Control Tower

THE PORT AUTHORITY had pulled Jimmy the Bishop’s audio. He was standing, as always, waiting to review it with the suits, when their phones started ringing like crazy.

“It’s open,” one guy reported. “Somebody opened up 3L.”

Everybody was standing now, trying to see. Jimmy the Bishop looked out from the tower cab at the lit-up plane. The door did not look open from up here.

Calvin Buss said, “From the inside? Who’s coming out?”

The guy shook his head, still on his phone. “No one. Not yet.”

Jimmy the Bishop grabbed a small pair of birders off the ledge and checked out Regis 753 for himself.

There it was. A sliver of black over the wing. A seam of shadow, like a tear in the hull of the aircraft.

Jimmy’s mouth went dry at the sight. Those doors pull out slightly when first unlocked, then swivel back and fold against the interior wall. So, technically, all that had happened was that the airlock had been disengaged. The door wasn’t quite open yet.

He set the field glasses back on the ledge and backed away. For some reason, his mind was telling him that this would be a good time to run.

Taxiway Foxtrot

THE GAS AND RADIATION SENSORS lifted to the door crack both read clear. An emergency service unit officer lying on the wing managed to pull out the door a few extra inches with a long, hooked pole, two other armed tactical officers covering him from the tarmac below. A parabolic microphone was inserted, returning all manner of chirps, beeps, and ring tones: the passengers’ mobile phones going unanswered. Eerie and plaintive sounding, like tiny little personal distress alarms.

They then inserted a mirror attached at the end of a pole, a large-size version of the sort of dental instrument used to examine back teeth. All they could see were the two jump seats inside the between-classes area, both unoccupied.

Bullhorn commands got them nowhere. No response from inside the aircraft: no lights, no movement, no nothing.

Two ESU officers in light body armor stood back from the taxiway lights for a briefing. They viewed a cross-section schematic, showing passengers seated ten abreast inside the coach cabin they would be entering: three each on the row sides and four across the middle. Airplane interior was tight, and they traded their H-K submachine guns for more manageable Glock 17s, preparing for close combat.

They strapped on radio-enabled gas masks fitted with flip-down night-vision specs, and snapped mace, zip cuffs, and extra magazine pouches to their belts. Q-tip – size cameras, also with passive infrared lenses, were mounted onto the tops of their ESU helmets.

They went up the fire rescue ladder onto the wing, and advanced to the door. They pulled up flat against the fuselage on either side of it, one man folding the door back against the interior wall with his boot, then curling inside, low and straight ahead to a near partition, staying down on his haunches. His partner followed him aboard.

The bullhorn spoke for them:

“Occupants of Regis 753. This is the New York – New Jersey Port Authority. We are entering the aircraft. For your own safety, please remain seated and lace your fingers on top of your heads.”

The lead man waited with his back to the partition, listening. His mask dulled sound into a jarlike roar, but he could discern no movement inside. He flipped down his NVD and the interior of the plane went pea-soup green. He nodded to his partner, readied his Glock, and on a three count swept into the wide cabin.

NOW BOARDING (#)

Worth Street, Chinatown (#)

Ephraim Goodweather couldn’t tell if the siren he heard was blaring out in the street—which is to say, real—or part of the sound track of the video game he was playing with his son, Zack.

“Why do you keep killing me?” asked Eph.

The sandy-haired boy shrugged, as though offended by the question. “That’s the whole point, Dad.”

The television stood next to the broad west-facing window, far and away the best feature of this tiny, second-story walk-up on the southern edge of Chinatown. The coffee table before them was cluttered with open cartons of Chinese food, a bag of comics from Forbidden Planet, Eph’s mobile phone, Zack’s mobile phone, and Zack’s smelly feet. The game system was new, another toy purchased with Zack in mind. Just as his grandmother used to juice the inside of an orange half, so did Eph try to squeeze every last bit of fun and goodness out of their limited time together. His only son was his life, was his air and water and food, and he had to load up on him when he could, because sometimes a week could pass with only a phone call or two, and it was like going a week without seeing the sun.

“What the …” Eph thumbed his controller, this foreign feeling wireless gadget in his hand, still hitting all the wrong buttons. His soldier was punching the ground. “At least let me get up.”

“Too late. Dead again.”

For a lot of other guys Eph knew, men in a situation similar to his own, their divorce seemed to have been as much from their children as from their wives. Sure, they would talk the talk, how they missed their kids, and how their ex-wives kept subverting their relationship, blah, blah, but the effort never really seemed to be there. A weekend with their kids became a weekend out of their new life of freedom. For Eph, these weekends with Zack were his life. Eph had never wanted the divorce. Still didn’t. He acknowledged that his married life with Kelly was over—she had made her position perfectly clear to him—but he refused to relinquish his claim on Zack. The boy’s custody was the only unresolved issue, the sole reason they still remained wed in the eyes of the state.

This was the last of Eph’s trial weekends, as stipulated by their court-appointed family counselor. Zack would be interviewed sometime next week, and soon afterward a final determination would be made. Eph didn’t care that it was a long shot, his getting custody; this was the fight of his life. Do the right thing for Zack formed the crux of Kelly’s guilt trip, pushing Eph to settle for generous visitation rights. But the right thing for Eph was to hang on to Zack. Eph had twisted the arm of the U.S. government, his employer, in order to set up his team here in New York instead of Atlanta, where the CDC was located, just so that Zack’s life would not be disrupted any more than it had been already.

He could have fought harder. Dirtier. As his lawyer had advised him to, many times. That man knew the tricks of the divorce trade. One reason Eph could not bring himself to do so was his lingering melancholy over the failure of the marriage. The other was that Eph had too much mercy in him—that what indeed made him a terrific doctor was the very same thing that made him a pitiful divorce-case client. He had conceded to Kelly almost every demand and financial claim her lawyer requested. All he wanted was time alone with his only son.

Who right now was lobbing grenades at him.

Eph said, “How can I shoot back when you’ve blown off my arms?”

“I don’t know. Maybe try kicking?”

“Now I know why your mother doesn’t let you own a game system.”

“Because it makes me hyper and antisocial and … OH, FRAGGED YOU!”

Eph’s life-capacity bar diminished to zero.

That was when his mobile phone started vibrating, skittering up against the take-out cartons like a hungry silver beetle. Probably Kelly, reminding him to make sure Zack used his asthma inhaler. Or just checking up on him, making sure he hadn’t whisked Zack away to Morocco or something.

Eph caught it, checked the screen. A 718 number, local. Caller ID read JFK QUARANTINE.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintained a quarantine station inside the international terminal at JFK. Not a detainment or even a treatment facility, just a few small offices and an examining room: a way station, a firebreak to identify and perhaps stall an outbreak from threatening the general population of the United States. Most of their work involved isolating and evaluating passengers taken ill in flight, occasionally turning up a diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis or severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

The office was closed evenings, and Eph was not to be on call tonight, or anywhere on the depth chart through Monday morning. He had cleared his work schedule weeks ago, in advance of his weekend with Zack.

He clicked off the vibrate button and set the mobile back down next to the carton of scallion pancakes. Somebody else’s problem. “It’s the kid who sold me this thing,” he told Zack. “Calling to heckle me.”

Zack was eating another steamed dumpling. “I cannot believe you got Yankees – Red Sox tickets for tomorrow.”

“I know. Good seats too. Third-base side. Tapped into your college fund to get them, but hey, don’t worry—with your skills, you’ll go far on just a high school degree.”

“Dad.”

“Anyway, you know how it pains me to put even one green dollar in Steinbrenner’s pocket. This is essentially treason.”

Zack said, “Boo, Red Sox. Go, Yanks.”

“First you kill me, then you taunt me?”

“I figured, as a Red Sox fan, you’d be used to it.”

“That’s it—!” Eph wrapped up his son, working his hands in along his ticklish rib cage, the boy bucking as he convulsed with laughter. Zack was getting stronger, his squirming possessed of real force: this boy who he used to fly around the room on one shoulder. Zachary had his mother’s hair, both in its sandy color (her original color, the way it was when he first met her in college) and fine texture. And yet, to Eph’s amazement and joy, he recognized his own eleven-year-old hands dangling uncannily from the boy’s wrists. The very same broad—knuckled hands that used to want to do nothing more than rub up baseball cowhide, hands that hated piano lessons, that could not wait to get a grip on this world of adults. Uncanny, seeing those young hands again. It was true: our children do come to replace us. Zachary was like a perfect human package, his DNA written with everything Eph and Kelly once were to each other—their hopes, dreams, potential. This was probably why each of them worked so hard, in his and her own contradictory ways, to bring out his very best. So much so that the thought of Zack being brought up under the influence of Kelly’s live-in boyfriend, Matt—a “nice” guy, a “good” guy, but so middle of the road as to be practically invisible—kept Eph up at night. He wanted challenge for his son, he wanted inspiration, greatness! The battle for the custody of Zack’s person was settled, but not the battle for the custody of Zack’s spirit—for his very soul.

Eph’s mobile started vibrating again, crabbing across the tabletop like the chattering gag teeth his uncles used to give him for Christmas. The awakened device interrupted their roughhousing, Eph releasing Zack, fighting the impulse to check the display. Something was happening. The calls wouldn’t have come through to him otherwise. An outbreak. An infected traveler.

Eph made himself not pick up the phone. Someone else had to handle it. This was his weekend with Zack. Who was looking at him now.

“Don’t worry,” said Eph, putting the mobile back down on the table, the call going to his voice mail. “Everything’s taken care of. No work this weekend.”

Zack nodded, perking up, finding his controller. “Want some more?”

“I don’t know. When do we get to the part where the little Mario guy starts rolling barrels down at the monkey?”

“Dad.”

“I’m just more comfortable with little Italian stereotypes running around gobbling up mushrooms for points.”

“Right. And how many miles of snow was it you had to trudge through to get to school each day?”

“That’s it—!”

Eph fell on him again, the boy ready for him this time, clamping his elbows tight, foiling his rib attack. So Eph changed strategy, going instead for the ultrasensitive Achilles tendon, wrestling with Zack’s heels while trying hard not to get kicked in the face. The boy was begging for mercy when Eph realized his mobile was vibrating yet again.

Eph jumped up this time, angry, knowing now that his job, his vocation, was going to pull him away from his son tonight. He glanced at the caller ID, and this time the number bore an Atlanta prefix. Very bad news. Eph closed his eyes and pressed the humming phone to his forehead, clearing his mind. “Sorry, Z,” he told Zack. “Just let me see what’s up.”

He took the phone into the adjoining kitchen, where he answered it.

“Ephraim? It’s Everett Barnes.”

Dr. Everett Barnes. The director of the CDC.

Eph’s back was to Zack. He knew Zack was watching and couldn’t bear to look at him. “Yes, Everett, what is it?”

“I just got the call from Washington. Your team is en route to the airport now?”

“Ah, sir, actually—”

“You saw it on TV?”

“TV?”

He went back to the sofa, showing Zack his open hand, a plea for patience. Eph found the remote and searched it for the correct button or combination of buttons, tried a few, and the screen went blank. Zack took the remote from his hand and sullenly switched to cable.

The news channel showed an airplane parked on the tarmac. Support vehicles formed a wide, perhaps fearful, perimeter. JFK International Airport. “I think I see it, Everett.”

“Jim Kent just reached me, he’s pulling the equipment your Canary team needs. You are the front line on this, Ephraim. They’re not to make another move until you get there.”

“They who, sir?”

“The Port Authority of New York, the Transportation Security Administration. The National Transportation Safety Board and Homeland Security are winging there now.”

The Canary project was a rapid-response team of field epidemiologists organized to detect and identify incipient biological threats. Its purview included both naturally occurring threats, such as viral and rickettsial diseases found in nature, and man-made outbreaks—although most of their funding came thanks to Canary’s obvious bioterrorism applications. New York City was the nerve center, with smaller, university-hospital-based satellite Canaries up and running in Miami, Los Angeles, Denver, and Chicago.

The program drew its name from the old coal miner’s trick of bringing a caged canary underground as a crude yet efficient biological early warning system. The bright yellow bird’s highly sensitive metabolism detected methane and carbon monoxide gas traces before they reached toxic or even explosive levels, causing the normally chirpy creature to fall silent and sway on its perch.

In this modern age, every human being had the potential to be that sentinel canary. Eph’s team’s job was to isolate them once they stopped singing, treat the infected, and contain the spread.

Eph said, “What is it, Everett? Did somebody die on the plane?”

The director said, “They’re all dead, Ephraim. Every last one.”

Kelton Street, Woodside, Queens

KELLY GOODWEATHER sat at the small table across from Matt Sayles, her live-in partner (“boyfriend” sounded too young; “significant other” sounded too old). They were sharing a homemade pizza made with pesto sauce, sun-dried tomatoes, and goat cheese, with a few curls of prosciutto thrown in for flair, as well as an eleven-dollar bottle of year-old merlot. The kitchen television was tuned to NY1 because Matt wanted the news. As far as Kelly was concerned, twenty-four-hour news channels were her enemy.

“I am sorry,” she told him again.

Matt smiled, making a lazy circle in the air with his wineglass.

“It’s not my fault, of course. But I know we had this weekend set up all to ourselves …”

Matt wiped his lips on the napkin tucked into his shirt collar. “He usually finds a way to get in between the two of us. And I am not referring to Zack.”

Kelly looked over at the empty third chair. Matt had no doubt been looking forward to her son’s weekend away. Pending resolution of their drawn-out, court-mediated custody battle, Zack was spending a few weekends with Eph at his flat in Lower Manhattan. That meant, for her, an intimate dinner at home, with the usual sexual expectations on Matt’s part—which Kelly had no qualms about fulfilling, and was inevitably worth the extra glass of wine she would allow herself.

But now, not tonight. As sorry as she was for Matt, for herself she was actually quite pleased.

“I’ll make it up to you,” she told him, with a wink.

Matt smiled in defeat. “Deal.”

This was why Matt was such a comfort. After Eph’s moodiness, his outbursts, his hard-driving personality, the mercury that ran through his veins, she needed a slower boat like Matt. She had married Eph much too young, and deferred too much of herself—her own needs, ambitions, desires—helping him advance his medical career. If she could impart one bit of life advice to the fourth-grade girls in her class at PS 69 in Jackson Heights, it would be: never marry a genius. Especially a good-looking one. With Matt, Kelly felt at ease, and, in fact, enjoyed the upper hand in the relationship. It was her turn to be tended to.

On the small white kitchen television, they were hyping the next day’s eclipse. The reporter was trying on various glasses, rating them for eye safety, while reporting from a T-shirt stand in Central Park. KISS ME ON THE ECLIPSE! was the big seller. The anchors promoted their “Live Team Coverage” coming tomorrow afternoon.

“It’s gonna be a big show,” said Matt, his comment letting her know he wasn’t going to let disappointment ruin the evening.

“It’s a major celestial event,” said Kelly, “and they’re treating it like just another winter snowstorm.”

The “Breaking News” screen came on. This was usually Kelly’s cue to change the channel, but the strangeness of the story drew her in. The TV showed a distant shot of an airplane sitting on the tarmac at JFK, encircled by work lights. The plane was lit so dramatically, and surrounded by so many vehicles and small men, you would have thought a UFO had touched down in Queens.

“Terrorists,” said Matt.

JFK Airport was only ten miles away. The reporter said that the airplane in question had completely shut down after an otherwise unremarkable landing, and that there had as yet been no contact either from the flight crew or the passengers still aboard. All landings at JFK had been suspended as a precaution, and air traffic was being diverted to Newark and LaGuardia.

She knew then that this airplane was the reason Eph was bringing Zack back home. All she wanted now was to get Zack back under her roof. Kelly was one of the great worriers, and home meant safety. It was the one place in this world that she could control.

Kelly rose and went to the window over her kitchen sink, dimming the light, looking out at the sky beyond the roof of their backyard neighbor. She saw airplane lights circling LaGuardia, swirling like bits of glittering debris pulled into a storm funnel. She had never been out in the middle part of the country, where you can see tornadoes coming at you from miles away. But this felt like that. Like there was something coming her way that she could do nothing about.

Eph pulled up his CDC-issued Ford Explorer at the curb. Kelly owned a small house on a tidy square of land surrounded by neat, low hedges in a sloping block of two-story houses. She met him outside on the concrete walk, as though wary of admitting him into her domicile, generally treating him like a decade-long flu she had finally fought off.

Blonder and slender and still very pretty, though she was a different person to him now. So much had changed. Somewhere, in a dusty shoe box probably, buried in the back of a closet, there were wedding photos of an untroubled young woman with her veil thrown back, smiling winningly at her tuxedoed groom, two young people very happily in love.

“I had the entire weekend cleared,” he said, exiting the car ahead of Zack, pushing through the low iron gate in order to get in the first word. “It’s an emergency.”

Matt Sayles stepped out through the lighted doorway behind her, stopping on the front stoop. His napkin was tucked into his shirt, obscuring the Sears logo over the pocket from the store he managed at the mall in Rego Park.

Eph didn’t acknowledge his presence, keeping his focus on Kelly and Zack as the boy entered the yard. Kelly had a smile for him, and Eph couldn’t help but wonder if she preferred this—Eph striking out with Zack—to a weekend alone with Matt. Kelly took him protectively under her arm. “You okay, Z?”

Zack nodded.

“Disappointed, I bet.”

He nodded again.

She saw the box and wires in his hand. “What is this?”

Eph said, “Zack’s new game system. He’s borrowing it for the weekend.” Eph looked at Zack, the boy’s head against his mother’s chest, staring into the middle distance. “Bud, if there’s any way I can get free, maybe tomorrow—hopefully tomorrow … but if there’s any way at all, I’ll be back for you, and we’ll salvage what we can out of this weekend. Okay? I’ll make it up to you, you know that, right?”

Zack nodded, his eyes still distant.

Matt called down from the top step. “Come on in, Zack. Let’s see if we can get that thing hooked up.”

Dependable, reliable Matt. Kelly sure had him trained well. Eph watched his son go inside under Matt’s arm, Zack glancing back one last time at Eph.

Alone now, he and Kelly stood facing each other on the little patch of grass. Behind her, over the roof of her house, the lights of the waiting airplanes circled. An entire network of transportation, never mind various government and law enforcement agencies, was waiting for this man facing a woman who said she didn’t love him anymore.

“It’s that airplane, isn’t it.”

Eph nodded. “They’re all dead. Everybody on board.”

“All dead?” Kelly’s eyes flared with concern. “How? What could it be?”

“That’s what I have to go find out.”

Eph felt the urgency of his job settling over him now. He had blown it with Zack—but that was done, and now he had to go. He reached into his pocket and handed her an envelope with the pin-striped logo. “For tomorrow afternoon,” he said. “In case I don’t make it back before then.”

Kelly peeked at the tickets, her eyebrows lifting at the price, then tucked them back inside the envelope. She looked at him with an expression approaching sympathy. “Just be sure not to forget our meeting with Dr. Kempner.”

The family therapist—the one who would decide Zack’s final custody. “Kempner, right,” he said. “I’ll be there.”

“And—be careful,” she said.

Eph nodded and started away.

JFK International Airport

A CROWD HAD GATHERED outside the airport, people drawn to the unexplained, the weird, the potentially tragic, the event. The radio, on Eph’s drive over, treated the dormant airplane as a potential hijacking, speculating about a link to the conflicts overseas.

Inside the terminal, two airport carts passed Eph, one carrying a teary mother holding the hands of two frightened-looking children, another with an older black gentleman riding with a bouquet of red roses across his lap. He realized that somebody else’s Zack was out there on that plane. Somebody else’s Kelly. He focused on that.

Eph’s team was waiting for him outside a locked door just below gate 6. Jim Kent was working the phone, as usual, speaking into the wire microphone dangling from his ear. Jim handled the bureaucratic and political side of disease control for Eph. He closed his hand around the mic part of his phone wire and said, by way of greeting, “No other reports of planes down anywhere else in the country.”

Eph climbed in next to Nora Martinez in the back of the airline cart. Nora, a biochemist by training, was his number two in New York. Her hands were already gloved, the nylon barrier as pale and smooth and mournful as lilies. She shifted over a little for him as he sat down. He regretted the awkwardness between them.

They started to move, Eph smelling marsh salt in the wind. “How long was the plane on the ground before it went dark?”

Nora said, “Six minutes.”

“No radio contact? Pilot’s out too?”

Jim turned and said, “Presumed, but unconfirmed. Port Authority cops went into the passenger compartment, found it full of corpses, and got right out again.”

“They were masked and gloved, I hope.”

“Affirmative.”

The cart turned a corner, revealing the airplane waiting in the distance. A massive aircraft, work lights trained on it from multiple angles, shining as bright as day. Mist off the nearby bay created a glowing aura around the fuselage.

“Christ,” said Eph.

Jim said, “A ‘triple seven,’ they call it. The 777, the world’s largest twin jet. Recent design, new aircraft. Why they’re flipped out about the equipment going down. They think it’s something more like sabotage.”

The landing-gear tires alone were enormous. Eph looked up at the black hole that was the open door over the broad left wing.

Jim said, “They already tested for gas. They tested for everything man-made. They don’t know what else to do but start from scratch.”

Eph said, “Us being the scratch.”

This dormant aircraft mysteriously full of dead people was the HAZMAT equivalent of waking up one day and finding a lump on your back. Eph’s team was the biopsy lab charged with telling the Federal Aviation Administration whether or not it had cancer.

Blue-blazer-wearing TSA officials pounced on Eph as soon as the cart stopped, trying to give him the same briefing Jim had just had. Asking him questions and talking over each other like reporters.

“This has gone on too long,” said Eph. “Next time something unexplained like this happens, you call us second. HAZMAT first, us second. Got it?”

“Yes, sir, Dr. Goodweather.”

“Is HAZMAT ready?”

“Standing by.”

Eph slowed before the CDC van. “I will say that this doesn’t read like a spontaneous contagious event. Six minutes on the ground? The time element is too short.”

“It has to be a deliberate act,” said one of the TSA officials.

“Perhaps,” said Eph. “As it stands now, in terms of whatever might be awaiting us in there—we have containment.” He opened the rear door of the van for Nora. “We’ll suit up and see what we’ve got.”

A voice stopped him. “We have one of our own on this plane.”

Eph turned back. “One of whose?”

“A federal air marshal. Standard on international flights involving U.S. carriers.”

“Armed?” Eph said.

“That’s the general idea.”

“No phone call, no warning from him?”

“No nothing.”

“It must have overpowered them immediately.” Eph nodded, looking into these men’s worried faces. “Get me his seat assignment. We’ll start there.”

Eph and Nora ducked inside the CDC van, closing the rear double doors, shutting out the anxiety of the tarmac behind them.

They pulled Level A HAZMAT gear down off the rack. Eph stripped down to his T-shirt and shorts, Nora to a black sports bra and lavender panties, each accommodating the other’s elbows and knees inside the cramped Chevy van. Nora’s hair was thick and dark and defiantly long for a field epidemiologist, and she swept it up into a tight elastic, arms working purposefully and fast. Her body was gracefully curved, her flesh the warm tone of lightly browned toast.

After Eph’s separation from Kelly became permanent and she initiated divorce proceedings, Eph and Nora had a brief fling. It was just one night, followed by a very awkward and uncomfortable morning after, which dragged on for months and months … right up until their second fling, just a few weeks ago—which, while even more passionate than the first, and full of intention to avoid the pitfalls that had overwhelmed them the first time, had led again to another protracted and awkward détente.

In a way, he and Nora worked too closely: if they had anything resembling normal jobs, a traditional workplace, the result might have been different, might have been easier, more casual, but this was “love in the trenches,” and with each of them giving so much to Canary, they had little left for each other, or the rest of the world. A partnership so voracious that nobody asked, “How was your day?” in the downtime—mainly because there was no downtime at all.

Such as here. Getting practically naked in front of each other in the least sexual way possible. Because donning a bio-suit is the antithesis of sensuality. It is the converse of allure, it is a withdrawal into prophylaxis, into sterility.

The first layer was a white Nomex jumpsuit, emblazoned on the back with the initials CDC. It zipped from knee to chin, the collar and cuffs sealing it in snug Velcro, black jump boots lacing up to the shins.

The second layer was a disposable white suit made of papery Tyvek. Then booties pulled on over boots, and Silver Shield chemical protective gloves over nylon barriers, taped at the wrists and ankles. Then lifted on self-contained breathing apparatus gear: a SCBA harness, lightweight titanium pressure-demand tank, full-face respirator mask, and personal alert safety system (PASS) device with a firefighter’s distress alarm.

Each hesitated before pulling the mask over his or her face. Nora formed a half smile and cupped Eph’s cheek in her hand. She kissed him. “You okay?”

“Yup.”

“You sure don’t look it. How was Zack?”

“Sulky. Pissed. As he should be.”

“Not your fault.”

“So what? Bottom line is, this weekend with my son is gone, and I’ll never get it back.” He readied his mask. “You know, there came a point in my life where things came down to either my family or my job. I thought I chose family. Apparently, not enough.”

There are moments like these, which usually come at the most inconvenient of times, such as a crisis, when you look at someone and realize that it will hurt you to be without them. Eph saw how unfair he had been to Nora by clinging to Kelly—not even to Kelly, but to the past, to his dead marriage, to what once was, all for Zack’s sake. Nora liked Zack. And Zack liked her, that was obvious.

But now, right now, was not the time to get into this. Eph pulled on his respirator, checking his breathing tank. The outer layer consisted of a yellow—canary yellow—full encapsulation “space” suit, featuring a sealed hood, a 210-degree viewport, and attached gloves. This was the actual level A containment suit, the “contact suit,” twelve layers of fabric which, once sealed, absolutely insulated the wearer from the outside atmosphere.

Nora checked his seal, and he did hers. Biohazard investigators operate on a buddy system much the same as that of scuba divers. Their suits puffed a bit from the circulated air. Sealing out pathogens meant trapping sweat and body heat, and the temperature inside their suits could rise up to thirty degrees higher than room temperature.

“Looks tight,” said Eph, over the voice-actuated microphones inside his mask.

Nora nodded, catching his eye through their respective masks. The glance went on a moment too long, as if she was going to say something else, then changed her mind. “You ready?” she said.

Eph nodded. “Let’s do this.”

Outside on the tarmac, Jim switched on his wheeled command console and picked up both their mask-mounted cameras, on separate monitor feeds. He attached small, switched-on flashlights on lanyards from their pull-away shoulder straps: the thickness of the multilayered suit gloves limited the wearer’s fine-motor skills.

The TSA guys came up and tried to talk to them some more, but Eph feigned deafness, shaking his head and touching his hood.

As they approached the airplane, Jim showed Eph and Nora a laminated printout containing an overhead view of the interior seat assignments, numbers corresponding to passenger and crew manifests listed on the back. He pointed to a red dot at 18A.

“The federal air marshal,” Jim said into his microphone. “Last name Charpentier. Exit row, window seat.”

“Got it,” Eph said.

A second red dot. “TSA pointed out this other passenger of interest. A German diplomat on the flight, Rolph Hubermann, business class, second row, seat F. In town for UN Council talks on the Korean situation. Might have been carrying one of those diplomatic pouches that get a free pass at customs. Could be nothing, but there is a contingent of Germans on their way here right now, from the UN, just to retrieve it.”

“Okay.”

Jim left them at the edge of the lights, turning back to his monitors. Inside the perimeter, it was brighter than day. They moved nearly without shadow. Eph led the way up the fire engine ladder onto the wing, then along its broadening surface to the opened door.

Eph entered first. The stillness was palpable. Nora followed, standing with him shoulder to shoulder at the head of the middle cabin.

Seated corpses faced them, in row after row. Eph’s and Nora’s flashlight beams registered dully in the dead jewels of their open eyes.

No nosebleeds. No bulging eyes or bloated, mottled skin. No foaming or bloody discharge about the mouth. Everyone in his or her seat, no sign of panic or struggle. Arms hanging loose into the aisle or else sagged in laps. No evident trauma.

Mobile phones—in laps, pockets, and muffled inside carry-on bags—emitted waiting message beeps or else rang anew, the peppy tones overlapping. These were the only sounds.

They located the air marshal in the window seat just inside the open door. A man in his forties with black, receding hair, dressed in a baseball-style button-up shirt with blue and orange piping, New York Mets colors, the baseball-headed mascot Mr. Met depicted on the front, and blue jeans. His chin rested on his chest, as though he were napping with his eyes open.

Eph dropped to one knee, the wider exit row giving him room to maneuver. He touched the air marshal’s forehead, pushing back the man’s head, which moved freely on his neck. Nora, next to him, teased her flashlight beam in and out of his eyes, Charpentier’s pupils showing no response. Eph pulled down on his chin, opening his jaw and illuminating the inside of his mouth, his tongue and the top of his throat looking pink and unpoisoned.

Eph needed more light. He reached over and slid open the window shade, and construction light blasted inside like a bright white scream.

No vomit, as from gas inhalation. Victims of carbon monoxide poisoning evinced distinct skin blistering and discoloration, leaving them with a bloated, leathered appearance. No discomfort in his posture, no sign of agonal struggle. Next to him sat a middle-aged woman in resort-style travel wear, half-glasses perched on her nose before her unseeing eyes. They were seated as any normal passengers would be, chairs in the full and upright position, still waiting for the FASTEN SEAT BELTS sign to be turned off at the airport gate.

Front-exit-row passengers stow their personal belongings in mesh containers bolted to the facing cabin wall. Eph pulled a soft Virgin Atlantic bag out of the pocket before Charpentier, running the zipper back along the top. He pulled out a Notre Dame sweatshirt, a handful of well-thumbed puzzle books, an audio-book thriller, then a nylon pouch that was kidney shaped and heavy. He unzipped it just far enough to see the all-black, rubber-coated handgun inside.

“You seeing this?” said Eph.