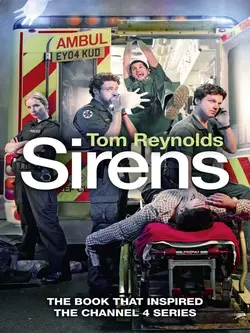

The Complete Blood, Sweat and Tea

Tom Reynolds

Collected in one volume, here are the true life stories of London ambulance driver, Tom Reynolds.*Previously published as Sirens, after the Channel 4 TV show inspired by the book*On any given day Tom Reynolds might be attacked by strangers, sworn at by motorists, puked on, covered in blood and other much more unpleasant substances. He could help to deliver a baby in the morning and witness the last moments of a dying man in the afternoon. He deals with road accidents, knife attacks, domestic violence, drug overdoses, neglect and suffering.And you think you’re having a bad day at work?His experiences spawned two volumes of memoir, both of which are collected here.

Sirens

Tom Reynolds

This book is dedicated to my mum and my brother, who have tolerated me with astonishing patience and love for almost forty years. It is also dedicated to all my work colleagues in the London Ambulance Service who do their best for the people who call them under some very difficult situations.

Finally to anyone and everyone who works for any of the emergency services – those people who bring calm to chaos, peace to despair and aid to the injured and frightened while working under incredible pressure and yet who rarely get the thanks that they deserve.

Contents

Prologue: Too Young

Part 1

Part 2

End Credits

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Sirens is not authorized or endorsed by the London Ambulance Service. The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the London Ambulance Service.

There are a number of terms found in this book that may be unfamiliar; for the assistance of the non-medical reader there is a short glossary at the back.

In the interests of confidentiality patients have been made anonymous and identifying characteristics may have been altered or removed.

Read more at http://randomreality.blogware.com

Prologue: Too Young

Yesterday started well, we had the only new ‘yellow’ vehicle on the complex, and it really is an improvement on the old motors. But then we got a job that should have been routine, but unfortunately was not.

We were given a ‘34-year-old male, seizure’ at a nearby football pitch in the middle of a park. Also leaving from our station was the FRU (a fast car designed to get to a scene before the ambulance). As we had a new motor, we were able to keep up with the FRU.

Arriving at the top of the street, we were met and directed by some of the patient’s football team-mates. Unfortunately, the patient was 200 yards into the park, and there was no way we were going to get the ambulance onto the field – the council had built a little moat around the park to stop joyriders tearing up the grass in their stolen cars.

The FRU paramedic had reached the patient first and I ran across the field to get to the patient as the paramedic looked worried, and this isn’t someone who normally worries.

As I reached the patient, carrying the scoop which we would use to move him, the paramedic asked me if I thought the patient was breathing.

The patient was Nigerian, and it is not racist to say that sometimes detecting signs of life on a black person is harder than if the patient is Caucasian. White people tend to look dead; black people often just look unconscious. Also, a windy playing field at dusk is not the ideal circumstance to assess a patient.

‘He’s not breathing,’ I told the paramedic, just as my crewmate reached us. ‘Shit’ replied the paramedic, ‘I left the FR2

(#litres_trial_promo) in my car’.

I had to run 200 yards back to our ambulance to get this, now vital, piece of kit.

On my return my colleagues had started to ‘bag’ the patient (this means using equipment to ‘breathe for’ the patient and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR), which is the procedure to keep blood flowing around the body in the absence of a pulse. Attaching the defib pads I saw that the patient was in ‘fine VF’ (ventricular fibrillation) – this is a heart rhythm which means the heart is ‘quivering’ rather than pumping blood around the body to the brain and other vital organs. Technically, the patient is dead and without immediate treatment, they will remain dead.

We ‘shocked’ the patient once and his heart rhythm changed. It changed to asystole (this means that the heart is not moving at all, and it is much more difficult to restore life to the patient with this form of rhythm). We decided to ‘scoop and run’ to the nearest hospital. The paramedic secured the patient’s airway by passing a tube down the windpipe, and we got the patient onto the scoop, all the time continuing the CPR and giving potentially lifesaving drugs. We then carried him, with the help of his team-mates, to the ambulance and rushed him to hospital.

Unfortunately, the patient never regained consciousness, and died in the resuscitation room.

Thirty-four years old, normally fit and healthy – and he drops dead on a football pitch. Despite our best efforts there was nothing more we could have done for him; the treatment went according to plan and the resuscitation attempt went smoothly. This was a ‘proper’ job, but one job we would have happily done without.

PART 1

Why Won’t They Let Me Do This?

Here is a moan about something that I am not allowed to do. I’m not allowed to run people over in my job. I could really clear the streets of a lot of stupid people if I was able to do that.

Picture the scene: there I am, driving through the streets of London in a big white van, with blue flashing lights, loud sirens running and the word Ambulance written in rather large letters. As a pedestrian, what would you do? Would you think ‘Hmm, being run over by that would really hurt, I think I’ll wait the 12 nanoseconds that it takes him to drive past before I cross the road’. Or would you, as most of the people in my area apparently do, think ‘Hmm, an ambulance on his way to an important job, I bet I can run across the road in front of him before he can hit me’.

During the last job, three people tried to dive under my ambulance. If I was allowed (by government grant or some such) to keep driving and splat them across my windscreen, that would mean three less idiots being allowed to breed tonight.

Oh well, I might get lucky later tonight.

Dear Mr Alcoholic

… Can all alcoholics please just get drunk in their houses and fall asleep there? Why do you insist that you drink your Tennent’s Super in a public place where some do-gooder will think you are ill and call for an ambulance?

… Can you also have a bath once in a while? I know it’s nice to roll around in the road while drunk, but it would be nice if you were at least a bit clean to start with.

… Would you mind awfully not swearing at me, taking a swing at me or exposing yourself to me? I have quite enough abuse from the non-drunks out there … Still at least your fists are easy to dodge, and if I stop holding you up, you fall over.

… If you have a medical condition, please don’t use it as an excuse to get taken into hospital. If you tell me ‘I’m drunk and need to sleep it off’, I have less work to do than if you tell me that you have ‘Chest pain, Angina, Cancer and Difficulty in Breathing’. The more tests I have to do the longer it will be before you get to hospital, and the more I have to come into physical contact with you. If you are just drunk, then I can just be a taxi.

… When you have been sick, at some point in the next week or so could you please change your clothing? Give them to someone who hasn’t knackered their brain on booze to wash. Dry vomit on the clothing, while advertising your love for beer, doesn’t endear you to me thankyouverymuch.

… Please keep your weight down either through diet or through terminal liver failure. I’m the poor bastard that has to lug the dead weight of your unconscious body into the ambulance.

… You don’t have to tell me ‘I’m an alcoholic’, and sound so proud about it. I do have a nose, and can smell for myself.

… Finally, although Tennent’s Super Strong lager, White Lightning, and for the rare rich alcoholic Stella Artois are perfectly acceptable drinks, could you please come up with something less damaging? I think lighter fuel is better for you and contains fewer chemicals.

A Child is Born …

The story of the first baby I delivered – I can still remember it now. I can also remember my feeling of relief when it all went smoothly. Yet still managed to turn it into a rant about midwifery.

Just in from my late-shift and feeling more upbeat than normal. Tonight I delivered my first baby … and yet I can still turn this happy event into a rant.

Picture the scene: you are a midwife (this means you have a chip on your shoulder the size of the African debt), and a lady comes in to your maternity department in the second stage of labour. Do you …

(a) Say hello, take a room and we’ll have that baby out as soon as we can,

or …

(b) Tell them to go home and come back when the pain gets worse.

Guess which answer results in your baby being delivered by an ambulance bloke who has 1 day’s training in maternity (and who, to be honest, slept through most of it)?

Then when I take mother and baby into the same maternity department are you …

(a) Vaguely apologetic, or …

(b) Snotty towards the ambulance crew who did your work for you?

Can you guess that tonight I got (b) for both questions?

Otherwise it was a nice simple delivery, with dad shooting pictures on his mobile phone sending them to all and sundry while his wife was lying, bloodstained and naked on a leather sofa. Blood went all over that sofa, which come summer will start to smell just a little rank. Blood also went all over me (note to self – must remember to pack Wellington boots next time) and my acting skills (‘Don’t worry mum, all normal, I’ve done hundreds of deliveries’) were tested to the limit.

… and I didn’t have to pick up any alcoholics.

Why Would People Even Think It?

I have sometimes been astounded by the bloodymindedness of people, and sometimes by their stupidity. Now I am astonished at their petty nastiness.

I’m driving my ‘big-white-van-with-blue-flashing-lights-and-a-siren’ to a 1-year-old child with difficulty in breathing. While passing a group of youths on the pavement, one of them thinks that it would be a good idea to throw his bottle of coke at the ambulance, thus spraying my screen, obscuring my vision and nearly causing me to swerve into oncoming traffic.

All I can say is that it is lucky for them that I was going to a call, because if I hadn’t I’d have shoved my boot up their arse.

Where in the tiny recesses of their minds does it seem like a good idea to throw something at an ambulance running on lights and sirens?

All I hope is that one day they need me – something likely, given the amount of people like that who get stabbed in my neck of the woods – and I’m just that little too slow to save their worthless skins.

Payment Point

I get called to a lot of RTAs (that is, for the uninformed, ‘Road Traffic Accident’). I’d say that 90% of these are diagnosed as ‘whiplash’ (which is a muscular sprain of the neck – this is a minor injury that is treated with painkillers); I’d suggest that over half of these are an attempt to gain insurance money. In the ambulance trade we call this the ‘Payment Point’, referring to the point in the neck that is painful, and pays out the money.

Tonight I saw the most blatant attempt to get money from an ‘accident’.

I was called to a flyover where two cars had been in a near collision, yes, a near collision. There was no damage to either vehicle, neither were there any skidmarks on the road. The ‘patient’ was the passenger of the car, and complained of pain on the right side of his neck. He was desperate to go to hospital, for what reason I did not know, as there was obviously no injury.

This was made even more evident when he forgot what side of his neck the pain was on. When I called him on this he pretended not to know what I was talking about.

Even the police were not above making fun of this idiot.

It probably didn’t help that he was 10 years younger than me and cruising around in a red sports car.

Of course RTA is now RTC (Road Traffic Collision), because if it’s an ‘accident’ then the police can’t prosecute anyone.

Single

Although I do love my job dearly, there are a number of disadvantages. At the moment I am a ‘relief’ worker, which means although I have a main station, I can be sent anywhere in London to cover absences and holidays in the ‘Core’ staff. I also don’t have a regular crewmate … I am essentially the whore of the London Ambulance Service.

So, at the moment I am sitting on my backside at my main station with no-one to work with, watching daytime TV.

Bored, Bored, Bored, Bored …

Of course, at some point in the next 12 hours I could be rushing off anywhere in London. Being on strange stations is actually quite good fun, as you get to meet new people and, let’s face it, in this job moving around London just means ‘same shit, different scenery’.

… But at the moment I’m bored …

Daytime TV, the ambulance relief’s worst enemy. Thankfully I’m no longer a relief – I’m ‘Core’ staff now, which means I have a regular partner and I work mainly out of one station.

Some People Just Can’t Wait

So, there I am in my ambulance helping a bloke who was actually quite ill, when all of a sudden the back doors fly open and some idiot decides to start berating me because I’m blocking the road. Needless to say I am not pleased at this, not only because it is embarrassing for the patient, but also because of the sheer bloody cheek of this person. When I tell her (very politely mind you) to bugger off, she replies with the old favourite ‘I’m a taxpayer and I pay your wages’. At this I remind her that my patient, my crewmate and I also pay taxes. At this she is a bit nonplussed, yet still she continues to moan that there is no need for me to block the road.

In any event, I did need to block the road, I don’t do it on purpose, but it is more important to get to the patient quickly.

This woman’s moaning then gets other drivers upset and they start honking their horns, and the only way I get rid of the woman who was in such a hurry was to pull the door shut after me and tell her to imagine her relative in the ambulance …

I didn’t hurry treating the patient either.

The same thing has happened on more than one occasion. Now I simply ask the complainer that if it was them rolling around in agony, would they like to have to wait while I find a better place to park?

Maybe it’s Because I’m a Londoner

Research carried out by the London Ambulance Service for our ‘No Send’ policy has shown that 59% of Londoners think that they will get seen quicker in A&E (Accident and Emergency department) if they arrive in an ambulance.

This … Is … Not … True …

In fact, if you come to A&E after calling an ambulance for something minor, the nursing staff will be more inclined to send you out to the waiting room and forget about you.

I was an A&E nurse for a long time – just trust me on this …

Also, Londoners call for three times the number of ambulances for ’flu than in any other English city. Half the time the patient has got a cold and not ’flu at all, and just needs to work it out of their system. Even if they did have ’flu, there is little the hospital could do for them anyway.

Coupled with high population densities, lack of staff and vehicles, speed-bumps everywhere and heavy traffic, is it any wonder we are having trouble hitting the 8-minute deadline we have to make 75% of calls in?

Nice New Motors

The London Ambulance Service is giving us poor ambulance staff shiny new ambos to drive … well, puke yellow rather than shiny … but they are new. These are Mercedes Sprinters outfitted in ‘EURO RAL 1016 Yellow’ which is apparently the most striking colour available and is used throughout the European Union. They have lots of nice new bits for us to play with. Most importantly, they have a tail lift so now we don’t need to break our backs lifting some 20-stone lump into the back of the motor (20 stone is 127 kilograms for those using ‘new money’).

I was asked by a friend what I thought of them, and having just finished my ‘Familiarisation Course’ (4 hours of playing with the new toy) I must say I do like it. Not only is the engine more responsive when moving off, but the brakes also work that bit better than our old LDVs (Leyland Daf vans) and the interior is much more professional looking.

The only real problem I foresee is that the tail lift needs around 4 yards to unload the trolley and around London this means that we will have to park in the middle of the road, blocking off other traffic. So, if you do see one of us blocking your way, please realise that there is no way we can park the things and be sure of being able to load a patient on board as well.

These things also cost £105 000 each and if we get the slightest scratch on them they have to be taken off the road and repaired (unlike the ones we have at the moment where they are beaten up until they stop working). Since our insurance has a £5 000 excess it’ll mean a lot more money going to vehicle maintenance.

Should be fun, but I can’t see management ever letting me drive one … I estimate if I can squeeze through gaps by driving until I hear the crunch …

While I thought that parking to allow the tail lifts space would be a big problem, our biggest problem would turn out to be the regular breaking down of the lifts.

My (So-Called) Exciting Life

I had my hair cut today, which has become a weighty decision in my mind. It goes something like this …

(a) Do I get a crop or not? If I get a crop I’ll look like I’ve just been released from a concentration camp; if I don’t then I’ll look like a paedophile.

(b) Will my mum like it? If not then I’ll have to put up with 3 weeks’ worth of moaning about how terrible I look.

(c) Will this cut enhance my ability to attract members of the opposite sex? To be honest, no haircut has ever done this but I live in hope.

(d) If I go to my local hairdressers will I get the trainee … and if I do will it be possible to get a refund?

Anyway, I went in and got a ‘short-back-and-sides’ and rather unfortunately I’m deaf as a post when I’m not wearing my glasses (for those who have 20/20 vision, you don’t wear your glasses when getting a haircut). So when the whole place erupted in fits of laughter I didn’t know if it was because of a rapidly growing bald-spot.

(Still while I can’t see it, it doesn’t exist.)

The best I can say is that I’m not having to brush my hair out of my eyes with a pair of gloves covered in someone else’s vomit.

Which is nice …

Bloody Cat …

I’m sitting here single on station (you need two people to man an ambulance, and if you haven’t got anyone to work with you are ‘single’ and therefore unable to work. However, you need to stay on station in case they find someone else in London who is single. In that case you find yourself trekking across London to work in a place you’ve only seen on telly). I’m hungry and bored, partly because it’s night-time, and partly because there is no-one else on station.

However I have a plan …

To counter the boredom I have a DVD I can watch on the station’s new DVD player (bought out of staff funds, so no we haven’t been defrauding the NHS). The hunger problem will soon be solved by the microwave curry I have sitting in my car.

Let us now introduce a new member into the cast: when I said I was alone that was a bit of a lie, there is the station cat. Well at least I think it’s a cat as it is so threadbare it could be anything. This cat is so stupid it lies in front of your ambulance just when you need it the most, and refuses to move until you physically have to kick lift it gently out of the way. However, it is intelligent enough to realise that when someone is using the microwave there will be an opportunity to beg for food 5 minutes later (13 minutes if the food is frozen).

I nearly fell over the damn thing stepping away from the microwave, only to spend the next 10 minutes discussing with a mouth full of chicken korma why it wouldn’t like to jump up on my lap and make off with my dinner. It went a little something like this …

Miaow.

‘No you can’t have any.’

Miaow.

‘You wouldn’t like it.’

Miaow.

‘Go eat your own dinner.’

Miaow.

Gets up, plate in hand, to check that the cat does indeed have food/water/toy mouse.

Miaow.

‘Will you bugger off!’

Miaow.

At this point I put the plate (still with some of my food on it) on the floor, which the mangy beast sniffs and turns his nose up at. Said ‘cat’ then goes and hides under a table.

Horrible bloody creature.

It’s now dead; there is only one person on station who misses the bloody thing.

Why This Is a Good Job

My crewmate and I went to a man having a fit on Christmas day; he was a security guard and built like a brick out-house. This fit wasn’t your ‘normal’ epileptic fit, but instead the man was punchy and aggressive. To say it was a struggle to get him on the back of the ambulance is to say that Paris Hilton may have appeared in an Internet video download. Cutting a long story short, the patient is diabetic and his blood sugar has dropped to a dangerously low level. Luckily, we carry an injection to reverse this, and after wrestling with him in order to give him this drug he made a full recovery before we even reached the hospital. This is a nice job because we actually helped someone rather than just drove them to hospital.

Other benefits of the job include (but are not limited to …)

Working outside in the fresh air. I don’t know how office workers put up with air conditioning.

For much of the time you are your own boss – do not underestimate this.

Driving on the wrong side of the road with blue lights and sirens going; it’s not about the speed it’s about the power.

Being able to poke around people’s houses and feel superior even though you haven’t done the washing up in your own house for 2 days.

No matter how annoying the patient is, knowing that within 20 minutes it’ll be the hospital’s problem.

Meeting lots of lovely nurses, and knowing that I get paid more than them.

On the rare occasion, being able to help people who are scared or in pain.

Every time I have a bad day, or feel fed up at work I think back to this list and soon start to feel better – although I no longer get paid more than the nurses I meet.

Death and What Follows

There are some people, who despite being lovely people, you dread working with; one such person is Nobby (not his real name). He is what is known in the trade as a ‘trauma magnet’. He’s one of those people who will get the cardiac arrests, car crashes, shootings and stabbings; by contrast I am a ‘shit magnet’, meaning I only seem to pick up people who don’t need an ambulance. Other than having to do some real work for a change I really enjoy working with him.

I was working with him a little time ago and we got called to a suspended (basically this is someone whose heart isn’t beating and they have stopped breathing). It’s one of those jobs that require us to work hard trying to save the punter’s life. We got to the address and found relatives performing CPR on their granny. You might have seen it on TV as a ‘Cardiac Arrest’.

(Let me correct a few ideas you might have about resuscitation. First, it rarely works; ‘Casualty’ and ‘ER’ have led people to believe that you often save people: I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of people who have survived an arrest and most of them arrested while I was watching them in hospital. Second, it isn’t pretty: when someone arrests there is often vomit, faeces, urine and blood covering them and the area around them. Finally, people never suspend where you can reach them: if there is an awkward hole, or they can find some way to collapse under a wardrobe they will do so.)

This poor woman was covered in body fluids and was properly dead; there was no way we were going to save her. One of our protocols says that we can recognise someone as beyond hope and not even commence a resuscitation attempt. Unfortunately, we couldn’t do it this time as the relatives had been doing CPR (which is the right thing to do) and so we had to make an attempt.

Nobby and I got to work and tried to resuscitate the patient for 30 minutes. Our protocol goes on to say that if we are unsuccessful after attempting a resuscitation for ‘a specified time’ we can end it and recognise death, which is what we did.

However, during our resuscitation attempt it seemed that the entire extended family had arrived and there were well over 20 people in this little terraced house with much wailing and gnashing of teeth. It’s always hard to tell someone that their mother has died, but it has to be done, and if you can manage it well you can answer some of their questions and hopefully provide some healing for them.

The GP (general practitioner) was informed, as were the police (a formality in sudden deaths). The family had called a priest and he was there before the police arrived, while the GP was going to ‘phone the family’; what he expected to be able to do over the phone puzzled me.

We tidied up and went onto another job.

Two weeks later, Nobby was called to a chest pain. He turns up and finds himself in the middle of a wake, surrounded by 20 familiar-looking people.

Can you guess who the wake was for? Its a funny old world …

I worked with Nobby again for the first time in 2 years. He still remembered the job, and what happened after it. I told Nobby that he’d be included in this book but he wasn’t happy with his pseudonym and told me that he would prefer to be referred to as ‘George Clooney’. I refused.

I Do Like Some Drivers …

Although I often moan about the idiocy of other people’s driving when faced with a big white van with blue flashing lights on top, I am sometimes pleasantly surprised at the lengths some people will go to in order to get out of the way. For example, yesterday we had people nearly grounding their cars on roundabouts and roadside verges, squeezing into parking spots I wouldn’t be able to fit a Mini Cooper in and swearing at other drivers who wouldn’t move out of the way. I’ve had workmen stand in the middle of the road and stop traffic, lollipop ladies fence off crossings with their ‘lollipops’, and van drivers who I have clipped while squeezing past them wave me on and tell me, ‘don’t worry about a little damage’.

Yesterday we had all the above on one call (except hitting a van driver), it was like the Red Sea parting before us. It was a beautiful thing to behold; it left us in awe and wonder.

Shame we were going to 2-year-old with a cough.

This is a rare occurrence.

The Dangers of Prostitution

Occasionally you get a job that makes you laugh, normally because the person you are picking up is an idiot. We got called to a chip shop in one of the main roads in Newham – unfortunately there are about 20 chip shops on this road, but we managed to narrow it down by looking for the shiny white police car parked outside. The call had been given as an ‘assault’ which can mean anything from a slap on the face to a fatal stabbing.

In this instance it was a young lad, the spitting image of ‘Ali G’, who was complaining that he had been hit on the nose; needless to say there wasn’t a mark on him, and it turned out that he had been hit by his girlfriend. The police wanted to take statements, but he wasn’t interested and when I tried to assess him he told me that the ambulance wasn’t needed as ‘I’m St Johns innit, and a security guard’. This fella couldn’t scare a toddler, so I suspected he was telling a little bit of a lie. As he wasn’t hurt and ‘refused aid’ my crewmate and I retreated to a safe distance to do our paperwork …

In the course of the night we found ourselves at the local hospital (dropping off yet another ill person) when who should walk in with another crew from my station, but our earlier ‘Ali G’ lookalike. I asked him why he decided to call an ambulance when he’d already sent us packing and it turned out that another woman had hit him … the prostitute he’d hired after his girlfriend had slapped him. Turns out she had hit him and then robbed him of his jewellery. He couldn’t have put up much of a fight because he only had one scratch on him.

It’s pillocks like these we have to put up with … and call ‘sir’ …

However, it is also jobs like this that we can use to have a good laugh with our workmates. So people like him do serve some purpose.

My Night Shift

Much fun and games last night, working in the Poplar/Bow area. Not only did some German bloke graffiti on the back of one of the ambulances, but he also called the crew from a payphone and ran off, repeating it twice.

There are a lot of strange people out there …

MacMedic (an American ambulance blog) gave a rundown of what his shifts are like, so I thought I’d do the same, in honour of our brothers in foreign climes.

All these people called an ambulance last night by dialling ‘999’.

(a) Fractured wrist – young lad at the Boat Show.

(b) An alcoholic ‘frequent flyer’ who has just been released from prison … We thought we’d got rid of him for good.

(c) A 15-year-old with a runny nose.

(d) Very minor RTA.

(e) Domestic Assault, with no actual injury, but police already on scene.

(f) ‘Facial Injury’ which turned out to mean ‘Some bloke kicked my door.’

(g) Assault with a cut hand – actually a decent injury with tendon involvement (which means surgery and physiotherapy).

(h) Varicose Vein that had burst – plenty of blood everywhere.

(i) A 29-year-old with chest pain, hyperventilating, with very upset relatives.

(j) A suicidal overdose in a house filled with young men with short hair and tight T-shirts (ifyouknowwhatImean).

(k) RTA with a traffic light pole coming off the worse in a two-car collision.

(l) An 8-month pregnant female who had fallen earlier that day.

and …

(m) A fitting 9-year-old; only one parent spoke English, and they decided to stay at home and send the father who doesn’t speak English with us, because ‘The hospital has interpreters …’

Now, out of these thirteen jobs, only five actually went to hospital …

This counts as a ‘good shift’, reasonably interesting jobs, and no-one tried to hit me.

I Hate Psychiatric ‘Services’

Sorry folks, bit of a rant here … but I last slept 22 hours ago …

We got a call to a patient who was ‘Depressed – not moving’: normally with this type of call it’s some teenager having a strop, but this time it was a little different. Basically, the patient, who suffers from depression, was discharged from the local psychiatric unit 3 weeks ago and recently had her dose of antidepressants reduced. Yesterday, she was crying all night, and tonight she was just sitting staring into space, refusing to make eye contact and not talking at all.

One of the things that we as an ambulance crew cannot do is physically remove someone to hospital if they don’t want to go – that would be kidnapping and is frowned upon by the law. This young girl was not going anywhere despite my best attempts to persuade her – she just wasn’t communicating.

The solution would be simple: call the Community Psychiatric Nursing (CPN) team to come and assess her and, if needed, arrange her compulsory removal to the psychiatric unit (called a ‘Section’ under the Mental Health Act). The problem? It was 10 p.m. …

First off I phoned the psychiatric unit that she had received treatment under. After talking to two idiots who had trouble understanding plain English, I finally managed to get the number of the CPN team. Now, the London Ambulance Service (LAS) is quite smart: when we want to arrange an outside agency we go through our Control because all the telephone conversations are recorded … so if someone says they are going to attend they damn well better. I got onto Control, passed the details to them and waited for them to get back to us.

I’d just like to say that in all my years of medical experience I have never had a simple referral to a psychiatric service: they always seem to try shirking any form of work by ‘forgetting’ you or by being just plain obstructive. Maybe I’m just unlucky and get the idiots every time.

Needless to say we waited … and waited … and waited … from 22:20 until 23:00 we waited; then at 23:02 Control got back to us. Apparently the CPN team all goes home at 23:00 and hadn’t answered the phone until 23:00 on the dot. So they refused to visit the patient. The moral so far is if you are going to have a psychiatric breakdown in Newham don’t do it after 22:00.

So we switched to plan ‘B’, which is to arrange the out-of-hours social worker to come and visit, as they double as Psychiatric Liaison. Again we went through Control and waited … and waited … and waited … Finally we heard back that the social worker would ring the family and would like to talk to me. (Outside agencies try this trick, as they know the patient’s phone isn’t being recorded, and so can say whatever they want, with any disagreement being my word against theirs.) The social worker explained that she was very busy and so would prefer not to come to see the patient and have I tried the out-of-hours GP?

Back to Control I went and got them to try and contact the out-of-hours GP (a GP, for those not in the UK, is the patient’s family doctor). Can you guess what we then did? We waited … and waited … and waited … Finally, Control got back to us and informed us that the out-of-hours GP hadn’t arrived for work yet and that when they did, they would have to see two other patients first.

All through this time the family of the patient were very understanding and were happy when I explained that the GP would call at some point in the night. All I could do was advise them to remove anything that the patient could use to hurt herself, and keep an eye on her, calling us back if they felt the need.

Total amount of time an ambulance was tied up trying to get outside agencies to DO THEIR DAMN JOB – 2 hours and 19 minutes … and not the world’s most satisfactory outcome.

As I mentioned to our Control, sometimes you feel very lonely out there on the mean streets of Newham.

It is still the case that as soon as the sun goes down, various community services disappear and people in trouble need to rely on the ambulance service and the A&E department, even if it isn’t the best place for them.

Sticky Feet

There is something deeply disturbing about walking on a sticky carpet – especially when the flat is in a complete mess and the punter has called an ambulance 4 times in the last 2 days for a pain in the chest that has lasted 2 years. I’d like the jury to note that the pain hasn’t changed in any way, it’s not worse, or moved around the body, he has no other symptoms. But the patient just seems to like calling ambulances. I wanted to wipe my feet on the way out of the flat.

It also doesn’t help when the patient smells so bad that I want to leap out the side window. We didn’t have any air freshener (and apparently, neither does the hospital).

When we got to the hospital the triage nurse took one look at the patient, muttered ‘Not him again’ and sent him out to the waiting room. I suspect that it may just be a ploy to use biological warfare to empty the waiting room.

I still keep getting called back to him for the exact same ‘problem’.

Workload

Once again I know a lot of visitors here are from America, so I’m going to explain how the LAS works on a day-to-day basis. This will either be very boring or immensely interesting – your choice.

Ambulances run out of dedicated stations, we don’t share stations with the Fire Service. In fact, some years ago, when it was suggested the idea was shot down as we would be disturbing the firecrews’ sleep throughout the night. Each station has its own call-sign ‘K1’, ‘J2’, ‘G4’ for example, then each ambo has a suffix that is attached to this, so one ambulance running out of station J2 would be called J201, while another would be J207.

The stations are spaced approximately 5–6 miles apart, and you mainly service the area surrounding the station; however, with interhospital transfers and other irregularities you can quite easily find yourself across the other side of London.

It’s an old joke that when asking if we need to travel so far the dispatcher will ask us if it still says London on the side of the ambulance.

There is a main station, and two or three ‘satellite’ stations; the main station will normally have between three and six ambulances running from it, while the smaller stations have between one and four. There is less cover at night, and you can easily find yourself being the only ambulance running from a given station.

Across London we deal with more than 3 500 calls per day, and with a fleet of 400 ambulances of which perhaps only three-quarters are manned, we seldom get a rest. Where I work we average 1 job an hour, and are supposed to transport every one of those patients to hospital.

The longest shift we officially do is 12 hours, in which we can expect 10–13 jobs, which doesn’t sound like a lot but is enough to keep us busy … We spend 97% of our time away from station (compared with 3% for the fire service).

However, it is a fun job.

Night Shifts

There has been a discussion over on another medical blog’s forums over which shift we prefer to work. Like many of the others I have a preference for working through the night. The reasons for this are many but include:

(1) I’m single, I can lie in bed as long as I want. And breakfast is dinner … and kebabs are lunch … and an icecream is supper.

(2) You get empty streets, and so can drive like someone out of ‘The Fast and the Furious’.

(3) You also get the strange jobs: ‘sex-toy accidents’, criminal behaviour, stabbings … (4) It feels as if you ‘own’ the world: there is no-one else around, and anyone you do meet is normally shocked to be awake at night.

(5) You get to work a lot of jobs with the police, who are generally excellent people to work with.

(6) I get to sleep through early morning television – I’m sorry but I can’t see the attraction of ‘Trisha’ or ‘This Morning’.

(7) I don’t have to go into a school, and be surrounded by 400 screaming children just because a kid has sprained their ankle.

(8) There is less management around – actually there is no management around (always a good thing); I like to avoid management as much as I can: I worked this job for 6 months before they remembered my name.

(9) On a cold winter morning, I’m going home to my warm comfortable bed, while everyone else is trudging to work.

I still like nights, which makes me a rarity in the LAS. Most of my most interesting jobs occur at night.

Busy, Busy, Busy

No sooner do I post why I like night shifts than I get two ‘proper’ emergency calls, one after another. The first was a 76-year-old Male ‘Suspended’. Unfortunately, despite our best efforts there was little hope for him, and he died later in hospital without his heart ever restarting. His wife of 50 or more years was disbelieving of the whole situation, and I was too busy doing CPR to be able to comfort her much. It is one of the few things that I miss about nursing – sometimes you want to spend time with a relative. If you can’t do anything for the patient, the relatives then become your concern. For the first time in 50 years she was going to sleep alone and the nurse who would be looking after her is not someone that I would call the most sympathetic person in the world. I spent a little longer at hospital talking to the wife. The only consolation that I could give her was something that I’ve practised many times over the years – that her husband never suffered, and that he wouldn’t have felt anything that we did.

The next job was a man who, after drinking too much, fell over in the street. He had a greatly altered level of consciousness, possibly due to the alcohol but also possibly due to the large head injury which was leaking a frankly excessive amount of blood over the tarmac.

He could have been worse – he was lying in the middle of the road and could have easily been run over. It is important in such a job that you should ‘collar and board’ them. This is a way of immobilising someone in order to prevent any damage to the spinal cord. Unfortunately the patient was quite combative and so the only safe way to secure his head was for me to hold it during the transport – all the time blood was leaking through the dressing we had put on him, all over us, the trolley bed and the floor of the ambulance. Some managed to flick up onto my crewmate’s face, which is something you don’t really want happening to you.

I’ve just come back from the hospital (after dropping off yet another assault) and our patient is doing fine – seems that his altered consciousness was indeed as a result of the alcohol. He still isn’t sober enough to have a meaningful conversation, but he is looking a lot better than when we picked him up.

I still like wrestling with drunks, and writing about blood being flicked up into your face set the stage for a future set of posts.

New Uniforms (But Still Green)

The LAS has got some new uniforms. These include ‘combat trousers’ and a fleece, which is nice seeing as it can get a bit nippy around here. The only problem is that we use ‘Alexandra’, who doesn’t have the best reputation, for our uniforms. We’ll forget that they can’t measure you up correctly – I am not a 38-inch waist no matter how many kebabs I eat. Instead, let us consider that the buttons on their shirts tend to fall off at the worst possible moment. Having a button drop in a dead man’s mouth when you are trying to resuscitate him is not something that inspires confidence in the relatives watching. I was supposed to have eight shirts; two of them have been cannibalised, so that I have six shirts with the right number of buttons.

The new uniform actually seems quite nice. We have a little NHS logo in case the big motor with ‘Ambulance’ written on the side is not enough of a clue to our identity, and the shirts have a mesh in the armpits so we can let our sweat out. The combat trousers have ‘Permagard’ (their spelling, not mine) which is designed to kill bacteria, which is nice considering the state of some of the houses we visit. The high-visibility jackets are … well … visible and we now have a green ‘beanie hat’ (I think it’s green so that people won’t wear them anywhere except at work).

There is a rumour that we will be getting new boots soon … ‘Magnums’. We are a bit like the army in that we buy our own boots because the ones supplied are a bit shoddy.

Anyway the uniform ‘goes live’ on the 12th but those who have uniform that actually fits have been wearing them early. The bosses are moaning a bit but haven’t actually told anyone off about it.

I now have five shirts with the right number of buttons. People are still buying their own boots.

Daddy, Daughter, Kill

Picked up an assault yesterday. While sitting in the back of the ambulance he told his 2-year-old daughter that ‘daddy is gonna fucking kill the people who did this to me’, then complained when the nurse at the hospital told him to moderate his language.

I love this job.

We then went to someone who started hitting his own nose in order to prove that it had been bleeding earlier, and then went to a woman who had a bleeding varicose vein that had stopped bleeding, but wanted to pick at it to prove that it had been bleeding.

Then we went to a 14-year-old girl who was ‘fitting’ but when we got there was confused and combative – she was a diabetic so we checked her blood sugar, which was low. Being confused is one of the symptoms of a low blood sugar and we normally give them an injection that brings them out of it. We gave the injection and waited for it to work and receive the grateful thanks of the parents.

But it didn’t work.

We checked the blood sugar again, and it had come back up to normal levels, yet the condition of the girl was unchanged.

So we (rather quickly) took her into hospital – we haven’t been back there yet to find out what had caused her confusion. Was it drugs, alcohol, psychiatric problems, CVA (cerebrovascular accident) or even just a bad nightmare? Once we get back to the hospital which we took her to we will no doubt be able to find out. She didn’t have a high temperature, didn’t have any medical history besides the diabetes, her pupils were normal and responsive; all observations were normal.

We spend a lot of time dealing with things that are simple to cope with. You can fix them almost by rote thinking, but every so often you get a job that throws you off balance. Normally you ‘wake up’ and deal with it by going back to basics, but other jobs just completely confuse you, and this was one of those jobs.

This post got me a large number of people coming to my site looking for the search term ‘Daddy fucking daughter’. Sometimes the Internet is a scary place. It turned out that the girl had been drinking vodka, and that this was the reason behind her confused and combative state.

ORCON!

ORCON – the biggest problem with the ambulance service, and the biggest cause of staff/management friction. Every so often I will revisit this topic, as it’s of such importance.

I’m single at work at the moment (which means I don’t have anyone to work with – so am sitting on station twiddling my thumbs), so I thought I’d tell you all about the great God ORCON and how he rules the life of every EMT/paramedic in England.

This is really boring, so I’ll not be hurt if you don’t bother reading any further.

The government likes to give everything targets, from school grades, the waiting time for breast cancer referrals to the number of trains on time.

The ambulance service has only one main target to reach, that of ORCON. ORCON was started in 1974 and governs how fast we are expected to respond to ‘Cat A’ calls. (‘Cat A’ calls are our high-priority calls, although because of the way calls are assessed, they are rarely seriously ill patients).

Essentially, for every ‘Cat A’ call in London we have to be there within 8 minutes.

Simple really.

It doesn’t matter what actually happens to the patient, just so long as we get there within 8 minutes. For example, if we get to someone who has been dead for 2 days within 8 minutes, that counts as a Success. If we get to a heart attack in 9 minutes, provide life-saving treatment and ensure that their quality of life is a good as possible it counts as a Failure.

For those who don’t live in London, let’s just say that traffic is often heavy, and there are speed-bumps and tiny side-roads. We have more than 300 languages spoken in London, which may delay getting the location we are needed at. We are hideously overused and understaffed, we face delays at hospital owing to overcrowding and delays on-scene because of the ignorant people we have to attend to.

None of this matters – all that matters is the 8-minute deadline. If we make 75% of all calls in 8 minutes we get more money from the government, which means more staff, vehicles that work etc. … If we don’t make 75% then we don’t get any more money and we continue to struggle. This year it looks like we are going to make it, but only just.

There isn’t any reason behind 8 minutes being the time we need to get to people: brain death occurs after 4 minutes or so; trauma, while needing to be treated as quickly as possible, has the ‘Golden Hour’. The current rumour is that it is how long MPs have to vote when the Division Bell rings in parliament – who knows? No-one I have spoken to has any decent answers.

Well, that should be the last of my posts on the boring ‘day to day’ running of the London Ambulance Service.

You may all rejoice now.

Oh … Bollocks …

Rather obviously this topic dominated my weblog for some time – I’m including only some of it here, because I’m sure that you didn’t want to pay good money to read about me being horribly ill. I haven’t edited this post for this book – it’s much how it originally appeared on my website. I started writing it less than 2 hours after I was exposed.

There is a fear that every health-care worker has. Tonight that fear jumped up and slapped me in the face.

Second job of the shift, we were called to ‘50-year-old male – collapsed in street’. Normally this is someone who is drunk, but we rushed to the scene anyway, just in case it isn’t (we rush to everything – it’s the only way to be sure you are not caught out). We reach the scene and see the male laying on the floor talking gibberish. He is bleeding from a cut on his face and possibly from his jaw. Bystanders tell us that he ‘just dropped’. He then starts to vomit, and because it’s dark we get him on our trolley and into the back of the ambulance.

Our basic assessment finds that he has no muscular tone on his right side, although all his observations are within normal limits. Deciding against hanging around we start transport to hospital. Halfway to hospital he starts to vomit and cough – part of this vomitus/blood flies unerringly across the width of the ambulance …

… right into my open mouth.

Pretty disgusting, but what can you do? The patient then starts to come around, now able to move all limbs and to talk. This is good, it means I’m able to get some history from him. So I get his name, date of birth, address. Then I ask this 50-year-old if he is normally fit and well.

‘No’, he says, ‘I have AIDS (acquired immune-deficiency syndrome)’.

Bollocks.

I’ve never had anything from a patient in my mouth before (apart from the odd chocolate when I was a nurse), so of course the first time is with an HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)-positive patient.

My crewmate looks in the rear view mirror, and that look passes between us. Ambulance people will know what I mean – it’s the ‘Oh shit’ look that you give/get when something goes horribly wrong.

We get to the hospital and the patient is looking a lot better, fully orientated, full strength and starting to feel the pain from a probably busted jaw. So I get to hand over to the nurse, which turned into a bit of a comedy moment …

Me: ‘Patient witnessed collapse, had right-sided hemiparesis, now resolved. Previous history includes AIDS’.

Handover Nurse: ‘Fine’

Charge Nurse: ‘You can’t say that’

Me: ‘Pardon?’

Charge Nurse: ‘You can’t say AIDS – people will be prejudiced against him’

Me: ‘Well they shouldn’t be, and this is medical stuff. It’s a syndrome like any other’

Charge Nurse: ‘You have to call it something else’

Me: ‘I don’t really care for political correctness, besides I’m a patient as well – I swallowed some of his blood’

Charge Nurse: ‘Oh, well … lets get you sorted out then’

I then went through the rigmarole of having blood taken, then I asked to be put on PEP, which the charge nurse agreed I should be put on. PEP is ‘Post Exposure Prophylaxis’ – basically a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs that, taken over a 4-week period, will hopefully reduce any live virus to non-infective amounts. Common side-effects include nausea, vomiting, headache, diarrhoea, cough, abdominal pain/cramps, muscle pain, tiredness, flu-like symptoms, difficulty in sleeping, rash and (I love this one) flatulence.

Other more uncommon side-effects are … pancreatitis, anaemia, neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, and other ‘metabolic effects’.

I’m in for a barrel of laughs for these next 4 weeks …

The charge nurse looked really sympathetic when he offered me stuff to look after the side-effects – he used to work in an HIV clinic so I guess he knows better than me what I’m in for …

Then we talked about rates of infection, which is why I’m feeling kinda relaxed here. HIV is a tough virus to catch (compared with hepatitis, which is the one that worries me). If I were to stab myself with a needle after drawing HIV-positive blood I would have a 0.004% chance of catching the virus. Swallowing a bit of blood/vomitus is less risky than that, especially as I have no mouth/stomach ulcers. With the PEP my chances of ‘seroconverting’ are as close to zero as you can get. I knew all this before I set foot in the hospital, which probably explained why I wasn’t a quivering wreck.

So far ‘only’ two medical workers have seroconverted after needle-stick injuries. I greatly doubt that I’ll be the third.

So ‘The Plan’ is that I go to see Occupational Health on Monday, and they will advise me on what happens next. I’ve been told already that I’ll have to avoid sexual contact for the next 3 months (not a hardship – I’ve managed ‘no sexual contact’ for 2 years before now) and that I’ll probably need to take 4 weeks off work due to me feeling too ill from the side-effects of the antiretrovirals.

We’ll see about that … I don’t ‘do’ ill.

Anyway, if I do need to take time off it’ll give me a chance to read some books I’ve got sitting on my shelf – and complete ‘Zelda – Windwaker’.

Gotta go now, I feel flatulent already …

I never got around to completing ‘Zelda’.

‘Donor’ Takes on New Meaning

I got a lot of support over the previous post, and to be honest I would have been a lot less calm if I didn’t have my blog where I could offload some of my worries.

First, thanks to everyone who has contacted me over my ‘exposure’, I appreciate it all, even if I haven’t personally replied to you (you’ll find out why I might not have answered you a bit later in this post …).

I went to Occupational Health on Monday, basically to let them know about my exposure, and that I was on PEP. The LAS showed how nice they are by lending me a spare ambulance to drive to my appointment – GPS navigation comes in handy when you don’t know where you are going.

Occupational Health is south of the river at King’s College Hospital, which is a bit of a trek. ‘Occy Health’ took baseline blood samples, so they would know if there was any effect on my liver/kidneys/white cell count, and filled in a couple of forms about my exposure. Then they told me that they would get in contact with the ‘donor’ to see what his virus load and hepatitis status was.

Until now I always thought of ‘donor’ as a ‘nice’ word – heart donors and the like – I never really thought it would happen to include this circumstance.

During the consultation they told me that I’d need blood tests every fortnight for the next month and a half, and that my first HIV/hepatitis status check would be in 3 months, with an additional one in 6 months. Should they both be negative then I would be in the clear.

They also told me of the side-effects of the antiretrovirals that I am taking, and seemed surprised that all I was experiencing was similar to a mild hangover.

That was yesterday – today was spent vomiting/sleeping to avoid nausea/and experiencing the joys of explosive diarrhoea.

My station officer called up and asked me how I was. When I told him, he basically told me to take it easy and go back to work when I felt better.

However, there was some good news when the Occupational Health nurse contacted me, and told me that the donor’s viral load was low, that there were no resistances to the PEP drugs I’m taking and that in 2002 he was free of hepatitis. That has eased my mind somewhat.

Some people have commented that I’m taking it rather well. There are a number of reasons for this, not least that the chances of me becoming HIV-positive are less than 1 in 5 000. The other thing is that I can’t do anything now to change those odds, apart from continue to take the PEP.

The other side-effect of the meds I’m taking are that I’m having a certain ‘vagueness’: my mind isn’t operating on all four cylinders, so if this seems disjointed, I’ve got an excuse …

Even today I’m not sure that the PEP drugs didn’t permanently ‘disjoint my mind’.

Pavlov’s Dog

Well, the PEP is still going down, unfortunately I’ve developed a Pavlovian response to the hours of 8 o’clock. Every 12 hours I need to take the pills – I start to get nauseous just thinking about it, the familiar copper taste hits my mouth and I just want to lie down.

I also seem to have lost any control over my circadian rhythms, I’m sleeping for 14–16 hours straight and I’m drowsy for the rest – doesn’t matter whether it is day or night.

At the moment the rather wonderful ‘Scissor Sisters’ album is chilling me out nicely, particularly ‘Return to Oz’ (which has a bit that puts me in mind of The Kinks’ ‘Lola’).

I am, however, losing the motivation for cooking food, not least because of the large amount of washing up accruing in my sink. It makes me feel like a student again.

Also, my PC is screaming out for a complete overhaul – I just can’t be bothered.

Mothering Sunday

Well, Saturday was the last day I worked but Greenfairy (another blogger) mentioned something that I wanted to write about – but forgot, for some bizarre reason …

The first call of Saturday was to a ‘?Suspended’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

So we hack along the road, knowing full well that because it is the first job of the day the patient is definitely going to be dead.

We arrive at the house and the FRU is there before us – I grab my kit and bound up the stairs past the daughter who called us and into the bedroom. Where a very dead lady was lying on the bed while the Rapid Responder was completing his paperwork.

One look is all you need to tell if someone has been dead for some time – and this lady had that look. It turned out that the daughter last saw her mother alive an hour ago, but that she was feeling a little unwell and took to bed. The daughter had checked on her half an hour later and found her not breathing. She then waited 20 minutes to call us as she was in such a ‘tizzy’. A quick look told us that even if we had been there when it had happened it was unlikely we could do much: various clues led us to think that a stomach ulcer had ruptured and she had bled out into her stomach.

All around the house were flowers and cards – the next day being Mothering Sunday.

No sooner than we had informed the daughter that her mother had died than the doorbell went and my crewmate went down to see who it was. It was only a bleedin’ flower delivery man, delivering flowers to the (now) dearly departed. My crewmate told the delivery guy that now, perhaps, wasn’t the best time to bring flowers but took them in anyway, hiding them in the kitchen.

Perfect!

Then we had to wait an hour for the police to turn up, which is normal procedure for any death in the home and is nothing to worry about. I then helped the police turn her body (to look for anything strange) and put my hand in a puddle of urine

(#litres_trial_promo) – something that wouldn’t bother me, IF I was wearing any gloves.

Oh well.

The Other Guy

I’m feeling a little better, the side-effects of the PEP seem to have subsided somewhat, although the flatulence is reaching epic proportions, which, coupled with the diarrhoea, makes every bowel motion an adventure

I have my second date with Occupational Health on Friday, for a blood test to make sure that the PEP isn’t battering my liver/kidneys/pancreas and that my white cell count hasn’t lowered. Work have said they’ll do everything they can to supply a vehicle to get me down to south-east London.

I’ve been thinking a bit about the ‘donor’; I wonder how he feels – he’s lying in bed after having a rather frightening collapse in the street, with a broken jaw and the reason for the collapse unknown. Then a couple of days later the medical team ask him to consent to some more blood tests because he may have infected the EMT who helped him out.

If it were me I’d be absolutely mortified.

When I talk to Occupational Health I’ll ask them if they can get a message back to him, letting him know that I’m fine and that I don’t blame him for anything. I know his name and address, but I don’t think it’d be right to turn up on his doorstep to talk to him.

I hope he is alright and that the collapse was something simple – I suspect a ‘TIA’ (transient ischaemic attack), which can be a precursor to a stroke, but with the right medications hopefully the threat of that can be controlled.

I never got to see him again, so he never found out the results of my blood tests. I kind of hope that he gets to read this, so he knows that I’m fine.

Twelve Hours to Go

In 12 hours I will have stopped PEP. Those seven pills are the last ones that I am going to take.

I am extremely happy about this.

It has been a month since my stomach didn’t feel as if I were waiting to vomit, a month since my thought processes have seemed even remotely like mine. A month since I last worked – good grief, am I bored! A month of wondering if my life is about to change for the worst. A month of my mates looking sideways at me when I had to take the pills in front of them (but still friends enough to laugh and joke with me about it). A month of having to get out of bed to eat breakfast, because the pills need food in my stomach. A month without shaving (why bother, I’m not allowed to have sex!). A month of feeling just the tiniest bit isolated. A month of people who I have never met, from places around the globe I have never seen, wishing me well. A month of always feeling grateful to those people, for this is the kindness of strangers – in itself a random act of reality.

All over now.

In two months I get to go for my HIV test, which should be fun and giggles.

But for now – I’m happy.

I really think that if it wasn’t for my blogging and the support of my friends around the globe I’d have gone mad from boredom. My next book should be Blogging as a Mental Health Exercise.

Proper Day

My first ‘proper’ day back at work, working with my new crewmate on a proper ambulance.

The first job was a 66-year-old male who had been fixing tiles on his shed roof and had fallen off the ladder, probably around 10 feet. He was shut behind his front door and all I could hear through his letterbox was ‘I’ve broken my leg’.

The police are much better than me at getting into locked premises (the last time I tried I fell on my arse in front of a crowd of 20 people) so we waited for them to arrive and use their specialised equipment (screwdriver/size 12 boot) to force open the door.

Gaining access to our customer it was pretty obvious that he had fractured his femur (thighbone) as it had a new bendy section just above the knee. The pulse was good in his foot and he didn’t complain of pain anywhere else in his body. This brave man had crawled, with this fracture, from his garden through his kitchen to the living room where he kept his phone. All throughout our treatment he didn’t complain once. We splinted his leg and ‘collared and boarded’ him from the house (a fall of 10 feet can easily break your neck, and the pain from his leg could easily distract him from a neck injury). We could have set traction on his leg, but we were only 5 minutes from the hospital; so we ‘blued’ him into Newham General Hospital, where he was ‘attacked’ by the local trauma team.

The next job we got was a dinner lady at a local primary school who had dropped a knife on her foot. There was a tiny cut to the foot, and after cleaning, dressing and checking her tetanus status we left her at work. What depressed us was that there were no scraps of food left we could have.

Driving back from the last job we saw four workmen chasing another man who ducked into the local mosque. We ignored this until we got a call to the area the men had run from – apparently a man had been assaulted with a ‘Car-lock’. HEMS (our emergency helicopter service) had been activated and were going to make their way to the scene. When we did a quick U-turn and rolled up to the scene it soon became obvious that HEMS was not needed so we cancelled them. The man had been clamping an illegally parked car when the owner and his wife returned. The car owner then pulled a large aerosol can from his boot and hit our patient around the back of the neck, causing a short period of unconsciousness. His wife had also put up a fight, but the owner of the car had run (into the aforementioned mosque) leaving his wife behind. (What a gent!) At one point we thought it was going to turn into a riot as 30 youths from the mosque were adamant that the four workmen doing the chasing weren’t going to set foot in the mosque.

Again, we had to collar and board him, and lift him onto our stretcher, which wasn’t much fun as the man weighed at least 20 stone. Subsequent treatment at hospital showed no serious injuries.

Final job (after having to get our nice, new, shiny ambulance fixed – a problem with the side-door) was a 60-year-old female collapsed at a bus station with slurred speech and ‘not drunk’. Remember that, ‘not drunk’, it’s important.

What could it be? Could it be a stroke? Could it be hypoglycaemia? Could it be cardiac related? So we turned up to find ‘Mary’ having fallen over, smelling strongly of alcohol and with a 5/6ths empty bottle of whisky in her purse. (My crewmate had to tell me about the smell of alcohol, as I’ve mentioned before, I’m pretty much unable to smell it myself.)

‘Not drunk’ – why did the callmaker say that? It’s bloody obvious she was pissed as a fart. I’d guess it was the bus station staff who wanted her gone and were afraid we wouldn’t turn up if we knew she was drunk. Still, it was an easy last job of the shift, even if she did keep grabbing at my balls and kissing my (thankfully) gloved hand.

This counts as a good day.

Now I’m off for some endorphin-releasing Bailey’s ice-cream.

Can you tell I was deliriously happy to be back at work?

These Boots …

These Boots …

Have walked along train tracks

Have been washed in the blood of murder victims

Have kicked in doors to get to unconscious women

Have stepped in more urine, in more tower blocks, than I’d care to think about

Have kept my feet warm and comfortable on long nights

Have been allowed into a mosque

Have climbed fences to reach dead bodies

Have run across football fields to try to save a life, and failed

Have been spat on, vomited on and shat on

Have stood in ‘remains’

Have tried to find purchase while walking backward down narrow stairs

Have defended me from drunks and druggies

Have been run over by a 22-stone trolley

Have been stared at by a daughter when I was telling her her mother had died

For Pixeldiva who denies she has a shoe fetish.

Gamma GT

I went to Occupational Health today – it seems that the last time they checked my blood (because of being on PEP) my liver enzymes were a bit elevated. Most significantly my gamma-GT (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase) was at 164 (it should be between 0 and 55). PEP is well known as having effects on the liver, so this isn’t completely unexpected.

More blood was taken today to check that the enzymes have returned to normal. The nurse was very concerned that I was alright in having my blood drawn, and that I wouldn’t faint. She was asking me this while I’m sitting opposite her in full uniform …

The nurse was also a bit surprised that I’d had aural hallucinations and looked at me as if she thought I was turning schizophrenic – I assured her that the ‘voices’ were now leaving me alone and that it wasn’t a problem. She’d never heard of this symptom before, so at least I entertained someone today.

Deaf Old Women

Nobby is working tonight from our main station. He is always a good laugh and always seems to have a joke whenever he works. Tonight I met him outside the hospital and he told me about a deaf old woman he had just brought in.

It was raining as he started to wheel her out her house so he made the comment ‘It’s raining, you picked a fine time to be ill’.

‘Eh?’ was the reply.

‘The rain … it mucks up my hair’.

‘Eh?’

‘MY HAIR!’

With this she took a long hard look at Nobby’s very short, and very receding hair and asked him, ‘Is it because of cancer?’

It is now 3 a.m. and already every other patient we have picked up has been drinking – from the 38-year-old male having a panic attack, who didn’t want to talk to us, to the 50-year-old female who slipped on some steps coming out from the pub and cut her head. This has so far ended with our last call being one of our smelly ‘frequent flyers’, who thankfully decided not to hang around and wait for us to turn up.

Then there was the police car that managed to accidentally force another car into someone’s garden – one of those jobs where every passing car slows down to stare. Thankfully, there were no injuries, apart from the house-owner’s disturbed sleep. (At least I assume it was the owner – he was dressed in no shoes and a dressing gown.)

With a bit of luck people are now wrapped up nice and snug in bed – away from the rain – and the only calls we will get will be the 5 a.m. ‘I’m in labour’ call that will result in a baby around 11 a.m. (long after I’m in bed).

Hand Over Mouth

No sooner do I hope for a quiet hour or two than the activation phone goes; it’s sending us 200 yards up the road to a ‘Collapsed Male’. We are met by two police officers who tell us that the patient was walking along the street, saw the policemen and then collapsed.

We get to the patient and my crewmate can’t smell any alcohol on him, but he is coughing and spluttering like an Oscar winner. He complains of a headache, coughing, leg pain, back pain and an inability to walk. Other than that he is refusing to talk to us. Examination is normal and the patient is obviously play-acting.

He then does one of the things that I really hate (given the prevalence of tuberculosis in Newham); he coughs all over us and the vehicle without putting his hand over his mouth. Then he starts to spit on the floor of the ambulance, again something I take a dim view of – but I’m driving so I leave it to my crewmate to sort out.

Forty seconds later and we pull up outside the hospital, and our patient decides to roll around the floor. By now our patience is wearing thin, so we haul him up and throw him in a wheelchair.

In the hospital he refuses to speak to the nurses, says he cannot stand and doesn’t acknowledge any requests. We leave him there and within 30 seconds are back on station.

While at the hospital I indulged in a little bit of teaching. The nurse who was assessing our patient was trying to check his pupil response (by shining a light in each eye and making sure that it reacts to light) but the eyes don’t appear to be reacting. I then suggest turning off the ceiling light that the patient is lying on his back staring at.

I still have patients who insist on coughing without putting their hand over their mouth. I’ve given up asking them to stop – instead I just give them oxygen, via a nice tightly fitting oxygen mask. I got a lot of people coming to this post searching for ‘Hand over mouth’. I swear I don’t know why.

Essential, Not Emergency

One of the bizarre things about the Ambulance Service is that, in the eyes of the government, we are an ‘essential’ service but not an ‘emergency’ service. We are ‘essential’ because the emergency services (Police, Fire Brigade and Coastguard) are run by the Home Office but Ambulance Services across the country are run by NHS Trusts, and as such do not have access to the same resources as the true ‘emergency’ services. The distinction is often slight, but can sometimes have quite important considerations for our safety.

Last night was a case in point. We were called to a patient with abdominal pain; however, further information was given that the patient could be violent. There was something in this information that triggered my ‘danger-sense’, so I was happy to wait for police assistance to arrive before approaching the house.

Four police officers turned up – normally only two are sent to assist us – and they told us that their computer system, and their personal experience with the householder, showed him as a nasty piece of work. We followed the police to the patient and they told him that they were going to search him, and that they wanted to put him in handcuffs first. The patient had obviously been involved with the police before, as once he was handcuffed they checked to see if he had any new warrants out for his arrest …

Searching him they found a large stick, and a rather worrying-looking (5-inch) knife on his person.

All through this the ‘lady’ of the house was shouting abuse, mainly at the patient, but occasionally at the police officers present. One quick examination showed nothing life-threatening, so we offered a trip to hospital, which the patient accepted. However, as we left the house the woman shouted a few final obscenities at the patient and he then told us he couldn’t be bothered to go to hospital and stalked off into the night. (This was not a problem for either my crewmate or myself.)

Police computers had information that he was dangerous (a number of rather vicious assaults) but our computers are not allowed to have such data. A police dispatcher has told us that they have all sorts of information on addresses, from animal liberation protesters to Members of Parliament. Again, our computers don’t have any information of that sort unless we enter it manually after an ambulance crew has been threatened assaulted.

Needless to say, one such report has been sent to central office.

I later found out that the patient was addicted to crack cocaine – which explains a lot.

Return of Pavlov’s EMT

Last night we picked up an alcoholic who is HIV positive. I (still) have no real fear of HIV patients, even when they are bleeding a bit and this patient was not (although they had wet themselves). The only problem is that I seem to have turned into one of Pavlov’s dogs. When we found out the patient was HIV positive my stomach churned as if I were back on the PEP. It was really rather strange because it wasn’t fear (I’ll only have that when I’m due for my HIV test) but instead something more … biological.

The son of the patient was extremely embarrassed at the antics of his parent, and my crewmate spent some time making sure that he was alright.

Naughty?

Is it naughty to take someone to hospital, who doesn’t really need to go, just in order to get a fry-up breakfast there?

It’s a lot simpler to take everyone to hospital whether they need it or not. It means that I have to do less paperwork, the patient feels validated and it means that if I’m missing something nasty (which is likely to happen at 6 a.m.) then the hospital has a chance to catch it.

Too Darn Busy

I am extremely busy at the moment; I’m often posting from my PDA (Personal Digital Assistant) and mobile phone. I should be catching up with stuff on Friday (including answering all those comments people have left).

Got some blood results (post PEP stuff), seems my white cell count is still going down. I think they have a life-span of 120 days, so it might get lower before it gets better. Still, it gives me an excuse to see the rather pretty occupational health nurse.

Today we did the usual of little old ladies who feel unwell calling their GP and the GP calling us to take them to hospital because they are too busy to drag their arses out of their office to visit sick people. On the radio it seems that lots of people are dropping dead – the weather is quite a bit warmer (24°C) so the old are placed under a bit more physiological stress.

I have a 101 things to do, and no time to do it – simple stuff like paying bills can be incredibly hard when you are single and a shift worker.

And I think I’m moaning too much …

I’m off to bed now. Goodnight all.

How Not to Stop a Stolen Car

So damn tired …

I’m currently at that point where I wonder whether I am hungry enough to cook dinner before I go to sleep. Which biological urge will win out?

Today, our Control wanted us to go to an emergency call when we were the other side of the Thames – I rather politely asked them if we were the nearest motor as we weren’t actually a boat, the reply was, ‘Yes, do you have your water wings?’ So we ended up going a couple of miles out of our way to cross the river.

The call was a faint, probably from the heat that is roasting London at the moment – at least the women are wearing revealing clothes, which makes our job of cruising through the streets a bit more enjoyable.

Picked up two psychiatric drug-using patients in a row who were drunk and lying in the road perhaps 500 yards away from each other. Some children were poking one with a stick …

Then there was the 51-year-old 4-foot-4 Asian grandmother who, upon seeing her husband’s car being stolen, jumped on the back and hung onto the rear windscreen wiper. She was flung off and, thankfully, not seriously hurt – mainly bruising and gravel rash. Unfortunately, the car that was stolen also contained her house keys and bank books. The A&E was so busy they had to put her out in the waiting room – something that annoyed me no end, especially as the nurse that put her out there had annoyed me earlier in the day by suggesting that I didn’t know what the symptoms of bulimia were.

Now to eat/sleep … then lather/rinse/repeat tomorrow.

Sunday

Sunday alone in my flat, no work, no stress, some decent stuff on telly = Good.

No chocolate in the fridge, uniform to be ironed, work tomorrow = Bad.

Phone call from Occupational Health telling me my blood values are back to normal = Excellent (only HIV/hep test to go now).

Eight … Nine Down