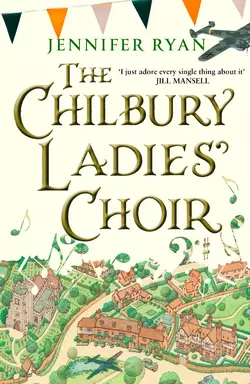

The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir

Jennifer Ryan

‘The writing glows with emotional intelligence. This atmospheric debut…had me sniffing copiously’ Daily MailIN WARTIME, SURVIVAL IS AS MUCH ABOUT FRIENDSHIP AS IT IS ABOUT COURAGE…Kent, 1940. In the idyllic village of Chilbury change is afoot. Hearts are breaking as sons and husbands leave to fight, and when the Vicar decides to close the choir until the men return, all seems lost.But coming together in song is just what the women of Chilbury need in these dark hours, and they are ready to sing. With a little fighting spirit and the arrival of a new musical resident, the charismatic Miss Primrose Trent, the choir is reborn.Some see the choir as a chance to forget their troubles, others the chance to shine. Though for one villager, the choir is the perfect cover to destroy Chilbury’s new-found harmony…An uplifting and heart-warming novel perfect for fans of Helen Simonson’s The Summer before the War and The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.

Copyright (#ulink_fe21bbf9-26e3-5800-9428-1b0ce3405d81)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Jennifer Ryan 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover illustration © Neil Gower 2016

Jennifer Ryan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008163709

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN: 9780008163723

Version: 2017-10-30

Dedication (#ulink_163aa2f8-418f-5d63-bf38-71cac0286183)

To my grandmother, Mrs Eileen Beckley,

and the women of the Home Front

Contents

Cover (#u77f0a0f7-a904-5f2a-9264-93993104ec54)

Title Page (#u41d481cd-9c93-5fdb-8032-ea42229c0c70)

Copyright (#ufd09eec6-467b-5d8d-9001-128f1d4987b7)

Dedication (#u1ba8643f-c1a6-54b1-84d3-19c1ee1fc9d8)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#u9bf49c11-bc90-58cc-ad96-f02dd0a6d2d0)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#ua4c0d4f8-dfcb-5df9-b303-825dd04b6e54)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#uf6b28d6a-1684-5f74-a824-a15d26a1d362)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#u818ff75c-bb81-5707-bc6e-0ab61b8ae405)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#u75bb4681-3479-5034-a8f0-090504f544a9)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#u8ac4c597-97c0-52b1-a2d2-9560445d4792)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#ufc4f3706-383b-5dac-adf6-46509d483892)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#u5a7b1fb3-c4e7-5cb8-b8d1-b565538c3501)

Silvie’s Diary (#ud23a2822-b246-5e25-85e0-575ce2575275)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#ua72498eb-157d-57eb-a4b0-03a72aaf15e5)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#u7b635664-71bf-5e13-b63b-10b486742cc3)

Letter from Flt Lt Henry Brampton-Boyd to Venetia Winthrop (#u0d2e33ca-3c0f-5782-b78c-6a9c3f7b9103)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#u90fa6372-2159-5475-b924-21ab0c44c47f)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#u7042fe88-1d87-585f-9a58-43e65dde9236)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#u9697e9a0-3575-51a1-9da8-2eb0f5512009)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Colonel Mallard to his sister, Mrs Maud Green, in Oxford (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Flt Lt Henry Brampton-Boyd to Venetia Winthrop (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Note from Miss Edwina Paltry to Brigadier Winthrop (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Silvie’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Lt Carrington to Mrs Tilling (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Silvie’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Elsie Cocker to Flt Lt Henry Brampton-Boyd (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Flt Lt Henry Brampton-Boyd to Elsie Cocker (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Colonel Mallard to his sister, Mrs Maud Green, in Oxford (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#litres_trial_promo)

Silvie’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#litres_trial_promo)

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#litres_trial_promo)

Interview with Jennifer Ryan (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Notice pinned to the Chilbury village hall noticeboard,

Sunday, 24th March, 1940

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#ulink_1fbf74fa-597c-5956-a1a9-6d2a57db04bd)

Tuesday, 26th March, 1940

First funeral of the war, and our little village choir simply couldn’t sing in tune. ‘Holy, holy, holy’ limped out as if we were a crump of warbling sparrows. But it wasn’t because of the war, or the young scoundrel Edmund Winthrop torpedoed in his submarine, or even the Vicar’s abysmal conducting. No, it was because this was the final performance of the Chilbury Choir. Our swan song.

‘I don’t see why we have to be closed down,’ Mrs B snapped afterwards as we congregated in the foggy graveyard. ‘It’s not as if we’re a threat to national security.’

‘All the men have gone,’ I whispered back, aware of our voices carrying uncomfortably through the funeral crowd. ‘The Vicar says we can’t have a choir without men.’

‘Just because the men have gone to war, why do we have to close the choir? And precisely when we need it most! I mean, what’ll he disband next? His beloved bell ringers? Church on Sundays? Christmas? I expect not!’ She folded her arms in annoyance. ‘First they whisk our men away to fight, then they force us women into work, then they ration food, and now they’re closing our choir. By the time the Nazis get here there’ll be nothing left except a bunch of drab women ready to surrender.’

‘But there’s a war on,’ I said, trying to placate her loud complaining. ‘We women have to take on extra work, help the cause. I don’t mind doing hospital nurse duties, although it’s busy keeping up the village clinic too.’

‘The choir has been part of the Chilbury way since time began. There’s something bolstering about singing together.’ She puffed her chest out, her large, square frame like an abundant field marshall.

The funeral party began to head to Chilbury Manor for the obligatory glass of sherry and cucumber sandwich. ‘Edmund Winthrop,’ I sighed. ‘Only twenty and blown up in the North Sea.’

‘He was a vicious bully, and well you know it,’ Mrs B barked. ‘Remember how he tried to drown your David in the village pond?’

‘Yes, but that was years ago,’ I whispered. ‘In any case, Edmund was bound to be unstable with his father forever thrashing him. I’m sure Brigadier Winthrop must be feeling more than a trace of regret now that Edmund’s dead.’

Or clearly not, I thought as we looked over to him, thwacking his cane against his military boot, the veins on his neck and forehead livid with rage.

‘He’s furious because he’s lost his heir,’ Mrs B snipped. ‘The Winthrops need a male to inherit, so the family estate is lost. He doesn’t care a jot about the daughters.’ We glanced over at young Kitty and the beautiful Venetia. ‘Status is everything. At least Mrs Winthrop’s pregnant again. Let’s hope it’s a boy this time round.’

Mrs Winthrop was cowering like a crushed sparrow under the weight of Edmund’s loss. It could be me next, I thought, as my David came over, all grown up in his new army uniform. His shoulders are broader since training, but his smile and softness are just the same. I knew he’d sign up when he turned eighteen, but why did it happen so fast? He’s being sent to France next month, and I can’t help worrying how I’ll survive if anything happens to him. He’s all I have since Harold passed away. Edmund and David often played as boys, soldiers or pirates, some kind of battle that Edmund was sure to win. I can only pray that David’s fight doesn’t end the same way.

The war has been ominously quiet so far, Hitler busy taking the rest of Europe. But I know they’re coming, and soon we’ll be surrounded by death. It’ll be like the last war, when a whole generation of men was wiped out, my own father included. I remember the day the telegram came. We were sitting down for luncheon, the sun spilling into the dining room as the gramophone played Vivaldi. I heard the front door open, then the slump of my mother’s body as she hit the floor, the sunshine streaming in, unaware.

Now our lives are going into turmoil all over again: more deaths, more work, more making do. And our lovely choir gone too. I’ve half a mind to write to the Vicar in protest. But then again, I probably won’t. I’ve never been one to make a fuss. My mother told me that women do better when they smile and agree. Yet sometimes I feel so frustrated with everything. I just want to shout it out.

I suppose that’s why I started a journal, so that I can express the things I don’t want to say out loud. A programme on the wireless said that keeping a journal can help you feel better if you have loved ones away, so I popped out yesterday and bought one. I’m sure it’ll be filled up soon, especially once David leaves and I’m on my own, thoughts surging through my head with nowhere to be let out. I’ve always dreamt of being a writer, and I suppose this is the closest I’ll get.

Taking David’s arm and following the crowd to Chilbury Manor, I looked back at the crumbling old church. ‘I’ll miss the choir.’

To which Mrs B roundly retorted, ‘I haven’t seen you instructing the Vicar to reverse his decision.’

‘But, Mrs B,’ David said with a smirk. ‘We always leave it up to you to make a stink about everything. You usually do.’

I had to hide a smile behind my hand, waiting for Mrs B’s wrath. But at that moment, the Vicar himself flew past us, trotting at speed after the Brigadier, who was striding up to the Manor.

Mrs B took one look, seized her umbrella with grim determination, and began stomping after him, calling, ‘I’ll have a word with you, Vicar,’ her usual forthright battle cry.

The Vicar turned and, seeing her gaining pace, sprinted for all he was worth.

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#ulink_2e8108c6-1c07-5f3b-a609-fab5abeff55d)

3 Church Row

Chilbury

Kent

Tuesday, 26th March, 1940

Brace yourself, Clara, for we are about to be rich! I’ve been offered the most unscrupulous deal you’ll ever believe! I knew this ruddy war would turn up some gems – whoever would have thought that midwifery could be so lucrative! But I couldn’t have imagined such a grubby nugget of a deal coming from snooty Brigadier Winthrop, the upper-class tyrant who thinks he owns this prissy little village. I know you’ll say it’s immoral, even by my standards, but I need to get away from being a cooped-up, put-down midwife. I need to get back to the old house where I can live my own life and be free.

Don’t you see, Clara? Soon I can pay back the money I owe, like I promised, and you’ll finally realise how clever I am, how I can make up for mistakes of the past. We can put everything behind us, and never mention what happened with Bill (although I always say I saved you from him). Then I’ll buy back our childhood house in Birnham Wood, all fields and cliffs beside the sea, and we can live safe and happy just like before Mum died. I’ll be finished with births and babies and nasty rashes in people’s nether regions, people bossing me about and laughing behind my back. I’ll be back to being my own person, no one watching over me.

But let me tell you about the deal from the beginning, as I know how you are about details. It was the funeral of Edmund Winthrop, the Brigadier’s despicable son who was blown up in a submarine last week. Only twenty he was – one minute a repulsive reptile, the next a feast for the fishes.

The morning of the funeral was cold and wet as a slap round the face with a fresh-caught cod. We might have been in the North Sea ourselves for the ferocious winds and grisly clouds, a monstrous hawk circling above us looking for a victim. ‘Rather fitting,’ I heard someone murmur as we plunged headlong with our umbrellas through the bedraggled graveyard and into the dim, musty church.

Packed to the rafters, the place was buzzing with gossipy onlookers. At the front, the Winthrops and their aristocrat friends were sitting all plumed and groomed like a row of black swans. A splatter of khaki and grey-blue uniforms appeared as per usual, uniformed men thinking they’re special when they’re just plain stupid. More like uninformed, I always say.

The rest of us locals (mostly wool-coated women these days) had to crowd around behind them, listening to the thin excuse of a choir, a few off-key voices hazarding ‘Holy, holy, holy.’ The posh women of the village are upset at the choir’s closing, but after a performance like that I’d rather hear a cats’ chorus.

Throughout the dreary service, the dead soldier’s mother snivelled into her hands, quaking under her black suit. She’s pregnant again, late in life – although she’s still in her late thirties. They say her nasty father forced her to marry the Brigadier when she was barely sixteen, and she’s been terrorised by him ever since.

She was the only tearful one though. The rest of us weren’t so blind to Edmund’s brutish, arrogant ways – just like his father. I’m sure there were even a few present who felt a justified retribution at his early demise.

Hardly attempting to look sad, the two sisters, now eighteen and thirteen, sat dutifully beside their grieving mother. The older one, Venetia, with her golden hair and coquettish ways, was more interested in batting her eyelashes at that handsome new artist than in the funeral. Young Kitty, gangly as a growing fawn, glanced around like she’d seen a ghost, her pointed face like a pixie’s in the purple-blue glow of the stained-glass window towering over the altar. Beside her, that foreign evacuee girl looked petrified, like she’d seen death before and a lot more besides.

The Brigadier glared on like a domineering vulture, the burnished medals and his upper-class prestige ranking him above everyone else in the church. He was rhythmically thwacking his silver-tipped horsewhip against his boot. His violent temper is legendary, and no one was going to cross him today. You see, not only had he lost his only son, he’d also lost the family fortune. The Chilbury Manor estate must go to a male heir, and Edmund’s death has plunged the family into turmoil. The Brigadier would be branded a fool if the family fortune was lost under his watch. But I know his type. He won’t take this lying down.

After the gruelling service, we grabbed our gas mask boxes and traipsed gloomily through horizontal daggers of icy rain up to Chilbury Manor, a Georgian monstrosity that some past Winthrop brutally erected.

I puffed up the steps to the big door, hoping for a glass of something and a big comfy sofa, but the place was already crammed with damp-smelling mourners and wet umbrellas. It was noisy as King’s Cross, what with the marbled galleried hallway echoing with ladies’ heels and noisy chatter. The Winthrops are an old, wealthy family, and the locals are scavenging toads, all hanging around in case they can get their grubby hands on some of the spoils.

And me? I already have my hand in their pocket, and that makes it my business to keep track of events around here. You see, the Brigadier has already been paying me to keep my mouth shut about his affairs, including that unwanted pregnancy last year, and his nasty son spreading disease around this village faster than you can say ‘the clap’. This war means opportunity for me. Any midwife worth her salt must realise the potential such a situation can bring, especially with the likes of these smutty gentry who think they’re beyond reproach. They’re easy prey for extortion – twenty here, forty there. It all adds up.

As I entered, my eyes caught a pretty twist of a maid, standing on the stairs to avoid the rush, a tray of sherry glasses balanced on one hand, her long neck elegant but her mouth sour as curd. She came to me with gonorrhoea she’d got from Cmdr Edmund last year, just like half the bleeding village. She told me he’d promised to marry her, promised her money, freedom, love, and then he’d vanished into the Navy as soon as war broke out. I felt sorry for her, so I told her about his other women – the previous maid, the gardener’s wife, the Vicar’s daughter – all with the same condition. I treated them all, and Edmund too, the disgusting beast. Elsie was the maid’s name. I think she was a bit unsettled that I told her everyone’s secrets, worried about her own, no doubt. But I told her it was because we were friends, her and I.

I smiled at her in a conspiratorial way, and took a glass of sherry from her tray. You never know when these people could come in handy.

I joined the condolence line behind gloomy Mrs Tilling, nurse, choir member, and deplorable do-gooder. ‘He will always be remembered a hero,’ she was saying with immense feeling. She is so excruciatingly well-meaning it makes me want to plunge her long face into a barrel of ale to perk her up.

‘Never should have happened,’ snapped Mrs B, another member of the choir, all upright with traditional upper-class fervour, the insufferable next to the insupportable. Her full name is Mrs Brampton-Boyd, and it exasperates her that everyone calls her Mrs B.

As I came to the front, Mrs Tilling sucked her cheeks in with annoyance. She’s never approved of me. I’ve stepped into her nursing territory, become too close to her village community. She may also have heard about some of my less orthodox practices. Or the payoffs.

‘It’s so terribly tragic,’ I said in my best voice. ‘He was taken so young.’ Planting a closed-lipped smile on my face, I swiftly moved away to the side, standing alone, people glancing over from time to time to wonder what business I had there.

Just as I was thinking of opening a few doors and having a little nosy around, a hunched goblin of a butler directed me into the drawing room, where I was rather hoping to partake of some upper-class funeral fare but found myself alone in the big, still room.

The distant clang of someone banging out the Moonlight Sonata on a piano clunked uneasily around the ornate ceiling as I ran my fingers over the crusted gold brocade couch. Then I picked up a bronze sculpture of a naked Greek, heavy in my fist like a lethal weapon. The opulence of the room was dazzling, with the floor-length blue silk drapes, the majestic portraits of repulsive forebears, the porcelain statues, the antiquity, the inequity.

I couldn’t help thinking that if I had that sort of cash I’d do a much better job, cheery the place up a bit. It smelt like death, as old as the dead men on the walls, as fusty as the eyes of the disembodied deer watching from the oak-panelled wall, the settle of dust and ashes. I was reminded of the last war, the Great War, when all the money in the world couldn’t buy an escape from mortality. It was the one great leveller. Funny how things went back to normal again so quick – the rich in charge, us struggling below.

I pulled out my packet of fags and lit one, the sinewy smoke meandering into the drapes, making itself at home.

A gruff voice came from behind. ‘May I have a word?’ A hand grasped my elbow, and before I knew it I was being pulled to a door at the back of the room. I turned to see the Brigadier, purple veins livid on his temples – he must have been at the Scotch late last night. He shoved me into a study, thick with male undercurrent, lots of leather chairs and piles of papers and files. The tang of cigars mingled unpleasantly with the dead-dog smell of rank breath.

As he twisted the key in the lock behind him, I knew this was going to mean money.

‘I’m sorry for your loss,’ I said, surveying the surroundings, trying to cover up any trepidation. The Brigadier’s a bigwig, an overpowering presence, officious and rude and unlikeable, yet powerful and ruthless. He’s one of the old types, the ones who think the upper class can still bluster their way through everything. The ones who think they can boss the rest of us around and act like they own the country.

‘I knew you’d come,’ he muttered in an irritated way, his voice slurring from drink. ‘Which is why I had Proggett put you in the back drawing room. I have a service for you to perform. Time is of the essence.’ He sat down behind his vast desk, all businesslike, leaving me standing on the other side, the servant awaiting instruction. I considered pulling over a chair, but fancied this act of rebellion might lose me a few bob, so I just plonked my black bag on the floor and waited.

‘Before I begin, I must know I have your full confidence,’ he said, narrowing his eyes as if this were an official war deal, when I knew outright it was going to be nothing of the sort.

‘Of course you have it, like you always do,’ I lied, glowering at him for even doubting my integrity. He didn’t scare me with his upper-class military ways. ‘I’m a professional, Brigadier. If that’s what you mean? I’m never surprised by what is asked of me. And I always keep my mouth shut.’

‘I need a job done,’ he said brusquely. ‘I’ve heard you’re willing to go beyond the usual services?’

‘That depends on what the service in question is,’ I said. ‘And how much I’ll be paid.’

A gleam came to his eye, and he sat up. I was speaking the language he wanted to hear – more interested in the money than the nature of the deed. ‘A lot of money could be yours.’

‘What exactly do you have in mind?’

By now I’d guessed he was about to come out with something big, something that would line my pockets well and good. My bet would have been another affair gone wrong (perhaps a high-profile woman involved, maybe someone from the village), so shocked doesn’t describe how I felt when he came out with it.

‘Our baby must be a boy.’

There was a pause as I wondered what he meant. He took in my reaction, his eyes scrutinising me, debating whether I had the requisite bravery, deceit, greed.

‘Ours is not the only birth to happen in the village this spring,’ he continued, acting like he was giving complex orders on the front line. ‘And ours must be a boy. If there were a way to ensure that this might be the case—’

The penny dropped. It was outrageous. He wanted me to swap his baby with a baby boy from the village, if his was a girl. I sucked in my lips, working hard to keep the ruddy great smile off my face. I’d take him to the bank for this! But I had to keep calm. Play it for all it was worth.

‘I think it would be a tremendous risk, as well as an immense personal compromise,’ I clipped.

He leant forward, dropping his façade for a moment, his eyeballs shooting out, bloody and globular. ‘But could it be done?’

‘Possibly,’ I said elusively. But I knew I could do it. I have a vicious herbal potion that induces babies to come forth very promptly, and the village is small, you can get from one house to another in minutes.

‘Anyone who could help that to occur would certainly be well compensated,’ he said evenly, his fingers toying with his moustache as if it were a battlefield conundrum.

‘How well?’

There was a scuffle from outside the door that made him pull back. ‘We can discuss that at another time and place.’ He stood up and went to the window. There was a French door that overlooked a muddle of fields and valleys down to the English Channel, grey and churning like dirty dishwater.

‘We’ll meet the Thursday after next at ten in the outhouse in Peasepotter Wood,’ he said in a low voice.

‘I’ll be there,’ I whispered.

‘You may leave now,’ he added. Then his head shot round and his eyes dug into me with threatening revulsion. ‘And mention this to no one.’

Only too happy to get away, I spun round and bolted for the door, fiddling with the key in the lock and then closing the door gently behind me, before sallying out into the thronging hall. My stride widened as I swooped in and out of the black-clad mourners, the uniforms, the nosy neighbours. I marched straight out of the front door without so much as bye your leave. People were still arriving in the expansive driveway, so I had to refrain from skipping for joy as I trotted briskly back to the village.

Once I was at my drab little home, I gave a well-earned cheer, throwing my arms up into the air and laughing with utter delight. This is going to work.

I’ll show you that you can forgive me for what happened with Bill, and for taking the money when we ran off. How was I to know he’d grab the cash and vanish as soon as he could?

We can be happy again, you and me, like when we were young. Funny, you never think how lucky you are until it’s all whisked away, first Mum dying, then staying with disgusting Uncle Cyril when Dad was in jail, shut in his attic like slaves. But enough of that. We’ll put the past behind us, Clara.

It’s time to gird our loins. There are two other women in the village who are expecting around the same time as Mrs Winthrop. Droopy Mrs Dawkins from the farm is on her fourth, so that should be simple. Less easy would be the goody-two-shoes school teacher Hattie Lovell, whose husband is away at sea. Hattie is chummy with that niggling nurse, Mrs Tilling, who’s done the midwifery course and sees fit to poke her nose into my birthing business. Every time I go round to Hattie’s, she’s there, hanging around like a superior matron, saying she’s going to be midwife at the birth. She doesn’t understand. This village is only big enough for one midwife.

I’ll write again after the meeting with the Brigadier. Who would have known such an upper-class gentleman could stoop so low? I’m going to tap him for the biggest money he’s ever known. I won’t let you down this time, Clara. You’ll get the money I owe you, I swear.

Edwina

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#ulink_2d107048-424c-5e6c-8a8b-7b3c4774c5a4)

Saturday, 30th March, 1940

They announced on the wireless that keeping a diary in these difficult times is excellent for the stamina, so I’ve decided to write down all my thoughts and dreams in my old school notebook. Nobody is allowed to read it, except perhaps when I’m old or dead, and then it should be published in a book, I think.

Important things about me

I am thirteen years old and want to be a singer when I grow up, wearing glorious gowns and singing before adoring audiences in London and Paris, and maybe even New York too. I think I will handle the fame well and become renowned for being terribly levelheaded.

I live in an antiquated village full of old buildings that always smell of damp and mothballs. There is a green with a duck pond, a shop, a village hall, and a medieval church with an overgrown graveyard. The church is where we used to have choir until the Vicar decided we couldn’t go on without any men. I’ve been pestering him to change his mind, but he’s simply not listening. In the meantime I’ve been trying to set up a choir at the school. I used to go to a boarding school, but they evacuated it to Wales and Mama didn’t want me to go. So now our butler, Proggett, has to drive me five miles to school in Litchfield every day. It’s not a bad place, except no one wants to join my choir.

I have one vile sister, Venetia, who is eighteen, and I used to have a brother until he was bombed in the North Sea. We live in the big house of the village, Chilbury Manor, which is terribly grand but freezing in the winter. It’s not as pristine as Brampton Hall, where Henry Brampton-Boyd lived before he joined the RAF to fight Nazis in his Spitfire. When I am old enough we are to be married, and we’ll have four children, three cats, and a big dog called Mozart. We’ll live a life of luxury, although we’ll have to wait until old Mr Brampton-Boyd passes away to inherit Brampton Hall, and since he prefers to spend his time in India, who knows when that may be. Venetia jokes that he only stays there to avoid his wife, bossy Mrs B, and if I were him I’d be tempted to do the same.

About the war

This war has been going on far too long – it’s been well over six months now. Life has been insufferable. Everyone’s busy, there’s no food, no new clothes, no servants, no lights after dark, and no men around. We have to lug gas masks everywhere, and plod into air raid shelters every time the sirens go off (although they haven’t very often so far). Every evening we have to draw thick black curtains across every window to stop the light from alerting Nazi planes to our whereabouts. The crackling of the news broadcasts on the radio is interminable, with people forever shushing and banning me from playing the piano.

Daddy is a brigadier, though I have no idea why as he never does any fighting, only occasionally going to London on what he calls ‘war business’. I think he’s trying to get into the War Office meetings, but they keep making excuses to keep him out. He has been especially cross, his horsewhip always at the ready to give one of us a reminder of our place. Venetia and I try to stay away from the house as much as we can. Mama’s petrified of him and also extremely pregnant, so no one’s around to watch us apart from old Nanny Godwin, and she’s far too old and has never been able to stop us from doing anything anyway.

Some of the papers say the war’s going to end soon, since there’s no fighting and the Nazis seem happy occupying Eastern Europe. But Daddy says it’s all nonsense, and the war is just beginning.

‘The papers are written by fools.’ He’s fond of picking up the offending newspaper and slamming it down on a table or desk. ‘Hitler’s taking his time in Poland, then he’ll turn his attention on us. Mark my words, the way this war’s going, France will fall before the end of the year. And then we’ll be next.’

‘But it’s so quiet and normal,’ I say. ‘My teacher is calling it the Phoney War because nothing’s really happening. Half of the children evacuated from London have gone back already. He says our troops will be home by Christmas.’

‘Your teacher is an imbecile who can’t see beyond his own four walls,’ Daddy cut in angrily. ‘Look at Poland, Czechoslovakia, Finland. Look at all the ships sunk, the submarines, and our own Edmund.’

We had to end the conversation there as Mama started crying again.

My brother Edmund’s death

The next thing I need to tell you about is Edmund, my brother who was blown up in his submarine. We’re supposed to be in mourning, and I feel dreadful for saying this, but I don’t miss him at all. He was a disgusting bully, and I loathed him. I’ve never forgiven him for shutting me in the well, the freezing water edging up to my mouth until Nanny Godwin found me. Or for the time he used me as a target in archery practice. Although he did promise to teach me to drive when I was older, which I suppose was quite nice.

Mama is beside herself and desperate for the new baby to be a boy, as is Daddy. He thinks girls are pointless, Venetia slightly less so because of her yellow hair. I am so utterly pointless I think he’s forgotten I exist, except perhaps when he needs someone to blame. Sometimes I go to Mama to see if she can stop him from being so horrid, but she can’t do anything. She only tells me to make sure I choose a decent, kind sort of man to marry. I wonder if she’s terribly unhappy.

Every evening, Mama has the maid set Edmund’s place for dinner, as if he’s about to come in any minute, sitting and stretching his legs in his usual arrogant manner, making some cruel joke at someone else’s expense, usually Venetia’s or mine. Then he’d let out a few breaths of laughter, smoothing back his hair, as if it were simply super to be him. Sometimes it’s hard to believe he’s just gone. It was his funeral last week, without a body to bury. It seems so strange. Where did he go?

Death is at the forefront of my mind again this week, as David Tilling is leaving for France and he may never come back, especially since he’s so hopeless at getting anything done. I heard Mrs B say yesterday that he was the type that a bullet would find faster than the rest, and I worry that she might be right.

I can’t believe the group of children we grew up with here in Chilbury are all suddenly scattering – Edmund killed, David on his way to war, Henry flying Spitfires over Germany, Victor Lovell on a ship somewhere, Angela Quail in London, and only Hattie and vile Venetia left. I’ll miss David especially. He was always the one waiting for me to catch up with the rest, a bit like a brother, only nicer. In a few weeks’ time he’ll be home after training, and everyone’s invited to the Tillings’ for a surprise leaving party before he heads off to the front. I know we’re supposed to be cheerful these days, even if we know someone might die, but it’s hard to forget that this could be the last time I see him.

List of things to make note of before someone leaves for war

The shape of their body – the blank cutout that will be left when they’re gone

The way they move, the gait of their walk, the speed at which they turn to look

The crush of smells and scents that linger only so long

Their colour, the radiance that veils everything they do, including their death

People’s colours

I like to see people as colours, a kind of aura or halo surrounding them, shading their outsides with the various flavours of their insides.

Me – purple, as brilliant and dark as the sky on a thundery night

Mama – a very pale pink, like a baby mouse

Daddy – soot black (Edmund was also black, but black like a starless sky)

Mrs Tilling – light green, like a shoot trying to come up through the snow

Mrs B – navy blue (correct and traditional)

Henry is a deep azure blue, to match his eyes. I’m always reminded of the flawless July day during our school holidays when he spoke of marriage, a year ago now. The sky was an endless blue, the stream beside our picnic spot trickling with late-afternoon laziness. Henry had joined Edmund, Venetia, and me, and we were tearing all over the countryside, Mama never having a clue where any of us had got to. Of course, because it was all out of the blue, Henry didn’t have a ring, and we’ve never made it official. But he remembers, deep down in his heart.

I know he remembers.

My beastly sister, Venetia

In complete contrast to the rest of us, Venetia is clearly enjoying this war immensely, and not only because no one’s around to keep an eye on her. It’s shuffled everything around, made everyone more adoring, and Edmund’s death has promoted her to top spot in the family. Venetia’s colour is a vile greenish yellow, like the sea on a tempestuous day, sucking the living daylights out of anything good around her, dragging down young men into her murky depths, spewing them out unconscious on distant shores.

I find it tremendously funny that she’s having trouble engaging the attention of the handsome newcomer, Mr Alastair Slater. He’s an artist escaping potential bombs in London, like all the writers and artists desperate to save themselves. Daddy says they’re running away, avoiding their duty. Mr Slater looks like Cary Grant – all groomed and sophisticated, unlike the boys around here. His colour is a dark grey to match his debonair suits and formal standoffishness. He seems completely uninterested in Venetia, even though she’s parading herself around him day and night. I overheard her telling Hattie that she’s made a bet with her friend Angela Quail that she’ll have him eating out of her hand before midsummer, but the way things are looking, she’ll have to work a little harder.

Angela Quail is the most flirtatious and despicable girl I know – it’s impossible to believe she’s the daughter of the Vicar. Her colour is tart red, all lips and slinky dresses and no morals whatsoever. She used to work with Venetia at the new War Command Centre in Litchfield Park, which is a gorgeous old manor house on the outskirts of Litchfield, complete with Georgian pillars and rolling gardens. It was requisitioned by the Government for the war a few months ago, and Lady Worthing is having to stay with her sister in Cheswick Castle, poor her. It’s now a terrifically important place, and since it’s only five miles from Chilbury, we’re on special alert in case the Nazis try to bomb it. Venetia has a clerical job there and thinks she plays a vital role when all she does is type notes and relay telephone messages to London.

Last month Angela was moved from there to the real War Office in London, where she is almost certainly toying with every man available. Angela is without doubt the most accomplished flirt this side of the English Channel. Venetia’s distraught that Angela’s gone to London as she’s her best friend, and who else can she share her conquests with? I was hoping that Venetia might become a bit nicer without Angela’s evil presence, but she seems worse than ever.

Our Czech evacuee, Silvie

Now I must tell you about Silvie, our ten-year-old Jewish evacuee. The Nazis have invaded her home in Czechoslovakia, but her parents managed to get her here before war broke out. Her family is supposed to follow her, when they can get away. Uncle Nicky, Mama’s youngest brother and my very favourite member of our family, was organising the children’s evacuation and got us to take Silvie last summer before the war started.

‘We had to stop the evacuation because the borders closed, which is terribly sad for the children left behind,’ he told us. ‘The Nazis run half of Eastern Europe now. It’s desperate over there. They’re thugs and arrest people if they don’t obey the rules. They can do what they want. Everyone’s petrified.’

Daddy wasn’t happy about having Silvie at all. But then a few months later war was declared and hundreds of grotty London evacuees turned up wanting homes. Suddenly he was overjoyed we had lovely, clean, quiet Silvie and no space for anyone else. The Vicar and Mrs Quail took in a dreadful woman with four squalling children who had lice and fleas and no table manners at all. The woman was forever arguing with Mrs Quail, and then upped and left back to London because the war didn’t seem to be happening. She didn’t even say thank you.

I’ve yet to decide what Silvie’s colour is. She doesn’t say much, or smile much either. We’ve been trying to make life a little jollier for her and helping her practise her English. And she told me she has a secret that she can’t tell a soul.

‘I am completely trustworthy,’ I reassured her. But she refused to budge, her little lips tightly shut to warn me away.

She arrived without even a suitcase, which had been lost on the way. There had been a difficult border crossing into Holland, and they had to hurry everyone through. It was a group of about a hundred, some of them as young as five or six – she said they cried for their mothers all the way, for three whole days. The loss of the cases was especially traumatic as they had their favourite toys, photographs from home, everything that was familiar. We gave Silvie a doll when she arrived, but she put it on a chair at the side of the room, her face to the wardrobe, as if it were a magical doorway to a better world.

The new music tutor, Prim

But I almost forgot. There’s some excellent news! A music tutor has moved into Chilbury. She came down from London to teach in Litchfield University. Her name is Miss Primrose Trent, but she told us to call her Prim, which is funny as she’s not prim at all but frightfully unkempt. With her frizz of greying hair and her sweeping black cloak, she looks more like a wizened witch with a stack of music under one arm. Her colour is dark green, like a shadowy woodland walk on a midsummer’s night.

Mrs Tilling introduced me to her yesterday in the shop, and I felt bold enough to tell her my dreams of becoming a famous singer.

‘Practise, my dear!’ she boomed, her dramatic voice causing the tins to rattle on the shelves. ‘You must have the courage of your convictions.’ She swept her arm out gracefully as if on a grand stage. ‘I can give you extra lessons if you have time.’

What an opportunity! ‘I’ll ask Mama to arrange one straight away. You see, we’ve had some disastrous news. The Vicar has disbanded the village choir, so we’re stuck without any singing.’

‘Well, that’s no good, is it! To close down a choir. Especially at a time like this!’

I’m hoping with every inch of me that she’ll persuade the Vicar to reopen the choir, although I can’t see what either of them can do. With no men around, what hope do we have? In the meantime though, I have singing lessons to look forward to as Mama agreed. That’ll propel me into the spotlight, I can tell by the way Prim’s eyes twinkled.

Letter from Venetia Winthrop to Angela Quail (#ulink_34fd6ca9-e3a6-5f1b-8c43-5c0d500532d1)

Chilbury Manor

Chilbury

Kent

Wednesday, 3rd April, 1940

Dear Angela,

The bet still stands! Mr Slater is tiresomely resisting my advances. I’ve tried my best tricks, even knocking on his door and asking if he had any spare paint as I was attempting ‘a frightfully difficult landscape’, but he simply handed some paint over and politely waved me off. I’d spent all day getting ready, wearing my green silk dress, my hair curled to perfection. Perplexing, my dear. Perplexing isn’t the word!

But you must stop proclaiming victory, as I’ll have him soon enough. He is truly captivating, Angie, and a romantic artist too. I’ve always thought of them as bohemian willowy types, but he is more athletic, with the look of a gentleman fencer – en garde and all that. Beneath those crisp suits I can make out his muscular arms, thighs even. How I long to run my fingers over him. But Angie, it’s more than that. There’s something about him that makes me feel we’re meant to be together. The way he looks at me, as if he’s looking through me to a different person inside.

I miss having you here, even though things are improving. Everyone is finally calming down after Edmund’s death, although Mama remains weepy and Daddy furious. I miss him too, in my way, the antics we’d get up to. Funny how one forgets how beastly someone can be when they’re dead. I suppose the threat of him is gone.

I’ve been rekindling my friendship with Hattie, even though she’s been as boring as boiled cabbage since she’s become pregnant. I went around for afternoon tea yesterday. She’d redecorated the baby’s room a ghastly green as that’s the only paint she could find. Her terraced house on Church Row is excruciatingly tiny. I don’t know how she can bear it.

‘But it’s next door to Miss Paltry, the midwife!’ she exclaimed, inexplicable joy on her pretty face, her long dark hair especially unruly since she’s been pregnant. ‘Don’t you see how useful that is? Although Mrs Tilling is to be my main attendant at the birth. She’s like family to me with my parents gone.’

‘And Mr Slater lives on the other side of you. That’s infinitely more exciting,’ I laughed, wondering if all this tedium was ruining my lipstick. I didn’t want to bump right into him without looking perfect.

‘How is your bet going?’ she asked.

‘Not well. I confess I don’t know what to make of him.’

‘I know what you mean. I do wonder what he’s up to. I always see him going out, in his motorcar or on foot, with not so much as a paintbrush, and he doesn’t come home for hours.’ Hattie’s always acting the sensible older one. She thinks being two years older makes her wiser. And now that she’s going to have a baby, she’s insufferable.

‘Maybe he’s really a movie star!’ I laughed. ‘He certainly has the looks.’

She didn’t laugh. ‘Maybe you’re better off chasing someone else.’

I looked at her, in her dreadful maternity dress, the lonely quietness of the pokey little house, but I knew she was tediously happy. I have to confess that a flash of envy crossed my mind. But don’t worry, I soon snapped out of it. Who wants Victor Lovell, after all? Who wants to be pregnant when there’s so much excitement with this war? All the new things a girl can do. We’d never have got our clerical jobs with the War Office, and you would never have been sent to live in London by yourself. All the parties and freedom. I heard that Constance Worthing is even ferrying planes for the war effort.

I suppose Hattie’s always been the sensible one, but she seems so annoyingly settled. I remember when we were young, the three of us in the Pixie Ring shouting, We are as strong as the snakes, as fierce as the wolves, and as free as the stars.

‘I’m still the same person as before,’ she said suddenly, as if reading my mind – funny how she does that – and I knew she hadn’t changed at all.

I thought about Hattie having a baby as I walked home. I’m not sure I’d like being a mother, but perhaps it isn’t as bad as all that.

Silvie came into my room when I was home, her quiet little feet treading carefully to the dressing table. She scoured it for treasures, asking me what various items were. Sometimes I make up stories about them: a necklace from the deep, a lipstick lost by a princess.

‘Do you like Mr Slater?’

‘How do you know about that?’

‘Kitty told me,’ she said simply. ‘I hope he is kind. Like you.’

I smiled and gave her a cuddle. I’ll have to make sure Kitty regrets telling my secrets, and doesn’t hear any more.

Do write soon, Angie, as I heartily miss your mischief making. I do wish they’d send me to London with you, although now that I have Mr Slater to tantalise me, perhaps not quite yet.

Much love,

Venetia

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#ulink_681bb743-21ae-5f77-8405-a4735a46be2c)

3 Church Row

Chilbury

Kent

Thursday, 4th April, 1940

Dear Clara,

The deal is done. We’ll be wealthy beyond our wildest dreams, dear sister. I went to meet the Brigadier, as arranged, in the deserted stone outhouse in the wood.

He was already there, crossly getting out his silver pocket watch. ‘You’re late.’

‘Am I?’ I smiled politely. ‘What a shame!’

He snorted at the unmistakable irony in my voice. ‘Well? Do you think you can do it?’

‘Swap the babies, you mean?’ I kept the smile off my face, although I still found it hilarious that he was suggesting just that. ‘Nip between the births and make both women believe they gave birth to a different baby?’

‘Yes, damn it, woman,’ he shouted. ‘Or should I find someone else?’

‘I doubt you’ll find anyone as trustworthy.’ Then I added with a little laugh, ‘Although Mrs Tilling has midwife training, if you’d like to ask her?’

‘Don’t be absurd,’ he bellowed. ‘Just answer me. Will you do it?’

‘Depends how much we’re talking.’

He snorted like a disgruntled bull. ‘I’ll give you five thousand.’

I stopped breathing for a split second. Five thousand pounds is a vast sum – ten times what I earn in a year. But I wasn’t willing to leave it there. The old rascal is worth far more than that. I’ve seen the finery, the crystal chandeliers, the crown sodding jewels.

‘I wouldn’t be able to work again, and I’d need to leave the village afterwards,’ I said, looking as sorrowful as I could. ‘I’d need twenty to give it a thought.’

He was furious. ‘Eight thousand then. That should be plenty for a woman like you.’

‘A woman like me?’ My face shot up to meet his gaze, and I raised an eyebrow. ‘A woman like me can kick up a good storm, you know?’

‘Are you threatening me?’ he hissed. ‘If you are, I’ll deny it. They’ll never believe your word over mine.’

‘Don’t count on it, Brigadier,’ I said. ‘The days of you toffs being in charge are long gone.’

‘I’ll get you strung up for something, you mark my words.’

‘Ten and I’ll do it,’ I said resolutely. ‘Provided I get the money regardless if it works out or not.’

‘You’ll do exactly what I tell you, Miss Paltry, or you’ll never work here again. Do you hear me?’ He came up close. ‘You’ll get your money when I get my boy.’

‘You give me the money beforehand, and if no boys are born, there ain’t a jot I can do about it. But if there is a boy’ – I smiled with enticement – ‘I will make him yours.’

He clenched his fists. He hadn’t been bargaining for this. Since arriving here five years ago I have been careful to build a reputation of even dealings, especially following my miscalculations in that village in Somerset. (You’ll remember how they hounded me out after I gave wart patients the wrong ointment that resulted in purple-coloured nether regions. It caused three marriage breakups, a major punch-up, the disappearance of a young woman, and at least two angry men trying to hunt me down.) No, Clara. I’ve played my game carefully in Chilbury, hushed up my past, played by their rules.

Now it’s time to reap the rewards.

‘All right, you’ll get ten thousand. But it’ll be half before and half after,’ he roared. ‘And if Mrs Winthrop gives birth to a boy, you’ll settle with half.’ He looked me over scowling. ‘How am I to trust a woman capable of doing such a business?’

‘Women are capable of many things, Brigadier. You just haven’t noticed it until now.’ I gave a quick smile. ‘I will need the first half of the money, in cash, two weeks from today.’

He blustered around the scrub, and I suddenly realised how much this deal meant to him. I should have taken him for fifty. He would have done it. He would have done virtually anything.

‘You’ll get your money,’ he growled under his breath. ‘Come back here on that date at ten, and it’ll be ready.’ He came towards me, his eyes scrunched up like Ebenezer Scrooge. ‘And mind you keep your mouth closed, or the deal’s off. Not a word to my wife either. She is not to know. Do you hear me?’

‘I hear you, Brigadier.’ I spoke quietly. ‘Loud and clear.’

With that I turned and strode out into the wood, leaving him pacing around, cursing under his breath.

Taking a deep breath of newly fresh air, I danced out of the bracken and onto the path. This will work, Clara. As a precaution, I have decided to get chummy with the nuisance Tilling woman. Keep my ear to the ground. This is big money, and my attention to detail merciless. I’ll write closer with details, just as you said you wanted in your letter. I know you think I’ll mess it up like usual, but I won’t let you down this time. You’ll be rich before the spring is out, I swear.

Edwina

Notice pinned to the Chilbury village hall noticeboard,

Monday, 15th April, 1940

Mrs Tilling’s Journal (#ulink_de42a33b-7540-57db-a87a-ec5add08e7cc)

Wednesday, 17th April, 1940

Prim’s notice in the church hall announcing a new ‘Ladies choir’ has caused uproar in our tiny community. Last night before the Women’s Voluntary Service meeting (or the WVS as we say these days), Mrs B told me she’d gone straight to the Vicar to find out the truth.

‘“Have you allowed this woman – this newcomer – to take over the choir and debase it beyond recognition?” I demanded of him, and do you know what he said? The Vicar, who is supposed to be a Man of God, told me, “Well, she was awfully forceful and I really couldn’t object.” I didn’t know what to say!’

‘Gosh,’ I said. I was rather excited about the whole adventure. At least we’d be singing again. I’d missed it. ‘I know it’s unusual, but why don’t we go along and see what Prim has to say. There’s no harm in it, after all.’

‘No harm in it?’ she bellowed back at me. ‘No harm in ruining the reputation of our village? I can’t imagine what Lady Worthing will have to say to me about it. She’s such a stickler for doing things the way they’ve always been done.’

A few of the other WVS ladies joined in, the Sewing Ladies tutting about it over their troops’ pyjamas, the canteen ladies unsure how it would work. So you can imagine my curiosity as I peeked into the church this evening, nipping in out of the rain.

I was one of the first to arrive, and the place looked enchanted, the candles at the altar throwing dark shadows around the nave. One by one the ladies began to arrive: Mrs Gibbs from the shop, Mrs B, Mrs Quail at the organ, and even Hattie, who’s heavily pregnant now but said she wouldn’t miss it for the world. Miss Paltry made an appearance – it seems she is turning a new leaf, even speaking to me at the end about becoming involved in the WVS. Kitty and Mrs Winthrop bounded in enthusiastically, bringing their evacuee, Silvie, who for once was almost smiling. Venetia strolled in, perfectly dressed in case she bumps into Mr Slater. She’s become astoundingly unpleasant. But maybe there’s hope for her now that Angela Quail’s out of proximity.

By seven the place was packed, in spite of the downpour, and a buzz of chatter and anticipation filled the chilly air; even Our Lady of Grace seemed to look down in readiness. Meanwhile, a firm contingent of naysayers clucked like a bunch of unhappy hens in front of the altos’ pew, urged on by Mrs B.

Suddenly, the massive double doors flung open, and Prim, majestic in her black, sweeping cloak, swooshed down the aisle towards us, her footsteps cascading through the wooden awnings, scaring a few bats in the belfry. She swirled off her cloak and shook off the rain, her hair looking especially frazzled. With a look of pomp and ceremony in her eyes, she plumped a pile of music on a chair and pranced theatrically up the steps to the pulpit.

‘May I have everyone’s attention, please,’ she called, her pronunciation resounding richly through the cloisters. ‘I’m proud to announce the creation of the Chilbury Ladies’ Choir.’

From one half of the crowd, a round of applause burst forth. I felt a warm glow inside me. This might become a reality.

But on the other side, Mrs B, hands on hips, stood defiant, guarding her territory and supporters with a firm, unyielding presence.

Prim continued, her bright grey eyes bulging with purpose. ‘I know that everyone’s been feeling downcast at the choir’s demise, which is why,’ she announced jubilantly with a flourish of her baton, ‘I proposed to the Vicar that the village’s dear choir should become a women’s-only choir.’

‘And how exactly did you do that?’ Mrs B asked in her usual condescending way.

‘I explained that now that there’s a war going on, we’re far more in need of a choir than ever before. We need to be able to come together and sing, to make wonderful music and help ourselves through this dreadful time.’ She paused, turning towards a tall candle beside her so that its flickers reflected thoughtfully in her eyes. ‘Some of us remember the last war, the endless suffering and death it caused. It is time for us women to do what we can as a group to support each other and keep our spirits up. Just because there are no men, it doesn’t mean we can’t do it by ourselves.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ Mrs B stepped forward, her pompous form bristling up to the pulpit. She was dressed in her usual tweed shooting jacket and skirt, puffing out her chest in what her friends and neighbours know to be her fighting stance. ‘What will we do without the basses and tenors?’

‘We will sing arrangements for female voices, or I will rearrange them for us. We don’t need the men! We are a complete choir all by ourselves!’

‘In any case,’ Mrs Quail laughed from the organ, ‘the only bass we had was old Mr Dawkins. And he hasn’t been singing in tune for at least two years.’

A few titters came from younger members, but Mrs B was not disheartened, looking around for her supporters to speak up.

‘What will God think?’ one of the Sewing Ladies piped up. ‘He couldn’t have intended women to sing on their own. Just think of the Hallelujah Chorus – where would that be without men?’

‘There are plenty of male-only choirs, aren’t there?’ Prim chuckled. ‘Think of the great choirs of Cambridge, not to mention St Paul’s Cathedral. I can’t imagine any God would dislike a spot of singing.’

‘But it goes against the natural order of things,’ Mrs B said.

I felt like clearing my throat and telling her that she was wrong, and before I knew it, I was saying out loud, ‘Maybe we’ve been told that women can’t do things so many times that we’ve actually started to believe it. In any case, the natural order of things has been temporarily changed because there are no men around.’ I glanced around for inspiration. ‘Mrs Gibbs makes her own milk deliveries now, and Mrs Quail has taken on the role of bus driver, like a lot of us taking on new jobs. The war’s mixed everything else up. Why shouldn’t it change the choir too?’

A few claps went round, as well as one or two cheers of ‘Hear, hear!’ and ‘That’s the spirit!’ I still couldn’t believe I’d stood up and spoken, and to Mrs B as well, who was watching me in a highly disapproving way.

‘Indeed, Mrs Tilling?’ Mrs B snipped. ‘I don’t know which part of that address shocks me the most! The notion of having to lower our moral standards because of the war, or the fact that you, my dear, seem to have joined the fray.’ She turned to the group, clustered on the altar between the two choir stalls. ‘We will end this once and for all with a show of hands. Whoever agrees with this preposterous notion, please raise your hand.’

Now Mrs B is not a spirited loser. Even as she counted and recounted the hands that went up, an indignant frown took form. She glowered at us as if we were somehow beyond reproach. ‘Don’t think this won’t have its consequences. I’ll be watching. Carefully.’ And with that she huffed off, making a great show of it, and then, not being able to quite leave, plonked herself down in the last pew. She obviously felt she could guilt us into changing our minds, but as the voices around me grew, I knew she had no such chance.

‘What a jolly idea,’ Hattie said. ‘I can’t think why we didn’t come up with it before.’

‘Yes, and such a splendid name too,’ Venetia declared. ‘The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir. It has a ring about it.’

I hadn’t thought of it before, but now I found myself wondering why we’d been closed down in the first place, why the Vicar had so much say over us. And, more to the point, why we’d simply let him do it.

Prim passed around some copies of ‘Be Thou My Vision’. ‘Let’s get ourselves organised. Stand in your usual places in the choir stalls, or wherever you’d like to be, and try to sing along with your part.’

We muddled around, and Mrs B huffed into the altos beside me. ‘I need to be here to see what a mess she’s going to make of the whole thing.’

‘It’ll be fine,’ I said, but I was holding my breath, praying that we’d do well. I didn’t want it to fall through right from the start, for Prim to be disheartened by our terrible voices. We needed to show her that this could work.

With a look of confidence on her face, Prim lifted her baton, looked to Mrs Quail to begin the introduction, and then brought us in. The sound of our voices filling the space, echoing through the little stone church, brought a burst of joy inside of me: the thrill of singing as a group again, the soft music of intertwining voices, for once staying in tune. I wondered if everyone was putting in a little more effort. Trying to make this work.

‘That was wonderful,’ Prim gushed when the final tapering of the last notes ebbed away into the still air. ‘We’ve got some talented singers here!’

We all smiled and hoped she was talking about us. Even Mrs B’s little group seemed to come under the spell of the music, forgetting the objections.

Mrs B, however, wasn’t ready to give up the fight. ‘I’ll have to speak to the Vicar about this,’ she announced, and flounced down the altar and out of the double doors. I’ll hear soon enough how that goes.

Afterwards, I wandered home in a trance, trapped between the euphoria of song and the pinpricks of fear reminding me that David is leaving soon. The Nazis invaded Norway last week, and we’re sending a force to try to push them out. I hope they don’t send David there.

Slowly, softly, I began to sing to myself ‘Be Thou My Vision’. Everything was black in the moonless night, the blackout rules forcing all the light out of the world. But with a cautious smile, I realised that there are no laws against singing, and I found my voice becoming louder, in defiance of this war.

In defiance of my right to be heard.

Kitty Winthrop’s Diary (#ulink_f72f36d5-2a0a-54f7-8718-b2245b3d27d6)

Thursday, 18th April, 1940

What a breathtaking day! My first singing lesson with the superb and masterful Prim took place at her house on Church Row at five o’clock. I have never been more excited, and arrived a whole ten minutes early, waiting for her to get back from the university.

Prim arrived on her bicycle, her cloaked body balancing precariously on the narrow frame. ‘You’re here early,’ she chortled. ‘I always say that enthusiasm paves every path with a shining light.’ She climbed off and leant the bicycle against the front of the house. ‘Come in, and we’ll make some tea before we start.’

The small house was exactly the same size and shape as Hattie’s, except it was completely filled with extraordinary things and smelt as musty as an antique shop. In the corner, a gold elephant stood on his hind legs. On the wall above were paintings of distant mountain peaks, and the burnt oranges and reds of a desert sunset. A small table was crammed with decorated boxes of different shapes and sizes, covered with shells or brightly coloured silks – peacock blue, emerald green, cerise.

‘Open one,’ she said, as she watched my eyes flitting over everything.

I picked up an emerald one with gold-coloured cord. There was a small latch that opened it, and inside the black velvet interior was a tiny silver ring, a child’s, with a St Christopher motif on the front.

‘Was this yours?’ I asked hesitantly.

‘Yes,’ she laughed. ‘It was given to me when I was a child. It came from India, where I grew up. India has always been my favourite place – the colours, the noise, the vibrancy, the people.’ She pointed to a picture of a beautiful white temple on the wall beside her. ‘We lived close to this majestic edifice, the Taj Mahal. It’s a mausoleum built by an emperor for his wife, who died in childbirth. He visited here every day, it is said, to grieve.’

‘Can you imagine loving someone so much that you create such a wonderful building?’

‘Well,’ she said. ‘It depends how rich and powerful one happens to be, I expect. Most people wouldn’t be able to afford it. But that doesn’t make one’s love any less. We can show our grief in simpler ways. Is not the beauty and power of funeral song just as great as such a palace?’

I nodded, peering into the sitting room that was beaming with the brightness of antiquities. ‘Do all of these things come from India?’

‘Not at all. I travelled across Asia. There’s a mesmerising world out there, where people live in all kinds of different ways.’ She led the way into the room so that I could see. Gold gleamed from every corner: gold urns, gold statues, gold silk drapes around the windows, tiny gold miniatures as small as my thumb – an elephant, an old woman, a falcon.

‘Other cultures are rather odd, don’t you think?’ I said.

‘No, quite the contrary. Other cultures often make me think that we’re the strange ones.’ She chuckled to herself, then headed for the kitchen. ‘Let’s make some tea.’

As the kettle boiled, I looked around. A series of old decorated jugs sat on the windowsill, and bunches of dried herbs lined the far wall, giving off scents of rosemary, thyme, and lavender. A waist-high seagull watched us from the corner.

‘Oh that’s Earnest, made of papier-mâché,’ she chirped. ‘He was one of the props for a play we put on in London years ago. He’s always here in the morning, looking hungry.’

I laughed and gave him a pat on the head.

Around the sink were a number of bottles full of liquids and powders and potions, and I leapt back. Was Prim a witch?

She saw me stare, and smiled. ‘Those are my medicines,’ she said. ‘I once was very ill indeed, and I need the medicine to prevent me from getting ill again.’

I stood back, looking at her. She looked pretty normal – well, normal in a kind of witchy way. ‘It’s not catching, is it?’

‘No, I caught it from a nasty mosquito in India, but we don’t have mosquitoes here.’ She rearranged the bottles, then made the tea. ‘The disease is called malaria.’

‘Were you terribly ill?’

‘It was almost the end of me. I was about the same age as your sister, my whole life ahead of me, with plenty of music and laughter, and romance too. There was a boy whom I was to marry.’ She smiled at the distant memory of him. ‘He was the most beautiful creature, a butterfly collector, brilliantly clever.’

‘Why didn’t you marry him?’

‘He died,’ she said simply. ‘He contracted malaria at the same time as me, and didn’t make it. We’d grown up as neighbours and then fell in love. We became ill at the same time. But the malaria ran its course and passed out of me. I was alive.’

‘But brokenhearted!’

‘Exactly, and ever since then I’ve felt destined to live a double life for both me and my butterfly collector, alone yet not.’ She found a floral porcelain sugar bowl and milk jug. ‘It taught me that you have to live your own life. Don’t let anyone hold you back.’

I found myself blurting out, ‘I want to be a singer, but Daddy insists that I can’t. He wants me to make a good marriage, to be a good wife. But Mama tells me to take care when choosing a husband, or my life will be a misery.’

‘You need to make your own path,’ she said, leading the way into the back room. ‘Decide what you want to do, and then all you have to do is work out how to achieve it.’

The room was full of musical instruments. There was a huge harp, an upright piano, a harpsichord, a stand with a clarinet, and a silver piccolo lying across the table like a fairy had just flown off after doing a spot of practice.

Prim perched the tray on a tiny round table and pulled over the piano seat, gesturing for me to sit on the harpsichord chair.

‘Is that why you never married? Do you still love the butterfly collector?’

‘I don’t know.’ She smiled, pouring out the tea. ‘Sometimes we do things without fully understanding. You shouldn’t try to know everything, Kitty. Often it’s beyond our comprehension.’ She put the teapot back on the tray. ‘Now before we start, I want you to sing me a note, as clearly as you can.’

I sang a long, high ‘laaaa’.

‘Beautiful,’ she said, picking up the cup and saucer again and handing it over to me. ‘Did you think about that too much before singing?’

‘No,’ I said, sipping the hot tea.

‘Sometimes the magic of life is beyond thought. It’s the sparkle of intuition, of bringing your own personal energy into your music.’

‘But don’t I need to worry about singing the right words to the right notes?’

‘The most important part of singing is the feeling.’ She leant forward. ‘Remember, Kitty. I have faith in you.’

That afternoon we sang ‘Ave verum corpus’ by Mozart, my favourite composer. I sang better and stronger than I ever have before.

‘There is a tragic tale about Mozart,’ she told me. ‘He wrote his Requiem, one of the saddest funereal pieces ever written, as he himself was dying, telling his wife, “I fear I am writing a requiem for myself.” On the eve of his death, he and some friends sang it together, and it was at the most poignant song of his Requiem, the ‘Lacrimosa’, that he let the papers drop and began to weep for his very own death. He died in the early morning. Can you imagine writing your own death music?’

I gasped. ‘That’s dreadful. Do you think the music made him die?’

‘Perhaps it was that he knew deep down inside that he was dying, and put that fear into the music.’ She looked back at the ‘Ave verum corpus’. ‘Why don’t you try this again, just like before, only this time, think about Mozart writing for his own death. Put your heart into it.’

She began the introduction, and I felt the sound of my voice come from deep inside, and I found myself thinking of the fear you must feel before you die.

A strange elation came over me when I’d finished, like I was a pure white dove’s feather being whooshed up into the air by the lightness of the breeze. And later, as I wandered home, I drew a deep breath of the crisp spring air, and I felt suddenly jubilant to be alive.

Letter from Miss Edwina Paltry to her sister, Clara (#ulink_0be0d400-8464-5c9c-96ff-e995881b5853)

3 Church Row

Chilbury

Kent

Friday, 19th April, 1940

Dear Clara,

A large pile of crisp hundred-pound notes is now hidden in a secret hole under my floorboards, wrapped in an old envelope and done up neatly with a piece of string knotted twice. In less than a month, the deed will be done, the money will be double, and we can away, you and I, to our new life in Birnham Wood.

Yesterday I met the Brigadier for the exchange, the bundle of money gripped firmly in his sinewy fingers, the tight old git. To say he was reluctant to hand it over would be putting it mild. But I finally wrenched it away and fled, the money safe in my hands.

That was the easy part.

Now I have to deliver the boy.

You see, much to my infuriation, Mrs Dawkins from the farm gave birth last Friday. I wanted to push its scrawny head back in, but then I saw that it was a girl, so it wouldn’t have been any good anyway.

Now my hopes are pinned on goody-two-shoes Hattie. She’s due a week after Mrs Winthrop, so at least I won’t have any issues with early births. Problem is the Tilling woman’s hovering around like a bleeding fairy godmother. Now she’s gone and promised to be midwife at the birth, even though I tried to talk Hattie out of it. I mean, who would take a misery like Mrs Tilling instead of an experienced, well equipped professional like myself? But she was adamant, whining that Mrs Tilling was the closest to family that she has in a pathetically sentimental way. God damn the girl!

Unspeakable as it was, I decided to befriend the nauseating Tilling woman. I had to persuade her out of it, or find out when she’d be out of town. If all else fails, I could give her a major injury, push her down some stairs or collide into her with my bicycle. I hadn’t wanted to go that route frankly. There’s a fine line between a broken arm and manslaughter, after all.

As a first effort, I joined the new choir to cosy up next to her, and I couldn’t believe my luck when I walked in and spotted a place right beside her.

‘I’m surprised to see you here, Miss Paltry,’ she said snootily, shuffling over. ‘It’s not often we see you in church.’

‘I always come on Sundays,’ I smiled warmly, although I bet she’s the type to count and see who’s absent.

There was a lot of kerfuffle about starting a women’s choir, which was patently ridiculous. Of course women can sing without men. I do it every week in the bath.

Then we sang some rather dreary hymns, and after practice was over, I saw my chance.

‘I feel it my duty, Mrs Tilling, to lighten your load and take over Hattie’s birth,’ I began. ‘I live next door to her, after all, and you’re so incredibly busy these days. I have all the equipment and medicines at my house should anything happen. I even have a mechanical ventilator,’ I lied.

‘What? In your own home?’ Mrs Tilling frowned with disbelief. ‘Did the hospital lend it to you?’

‘Yes, that’s it,’ I said quick as a fox, hoping she wouldn’t check. ‘You’d be surprised how often I need it to get the baby breathing proper. First-time pregnancies can be hazardous, you know.’

‘But you’re busy too, and Hattie’s made her mind up to have me there.’

‘I may be busy, but duty first!’ I bounced back. ‘I feel a responsibility, deep down inside.’ I thrust a fist up against my heart at this point, looking all patriotic. ‘And if anything should happen, I’d feel tormented for the rest of my days.’ I tried to push out a few tears at this point, but there’s only so much you can do.

‘Quite,’ Mrs Tilling said, stepping back, a look of distaste on her lips. I sensed that she smelt something fishy. I must have overdone the theatrics. So I quickly changed tack.

‘But you do so much for our little community, what with the WVS always helping people out – all this on top of your own nursing duties.’

‘Yes, the WVS is a great force. You should join. There’s a meeting in Litchfield a fortnight from today, distributing the Bundles for Britain from America. Why don’t you come along and see how it works.’

I smiled a gleeful smile, as that was precisely what I was looking for! A date when the Tilling woman would be out of town. And perfect timing too – a day before Mrs Winthrop’s due date, and a week before Hattie’s. ‘Is it an all-day event?’

‘Yes, all day Friday the third of May.’

She looked slightly bemused at my enthusiasm. So I stopped smiling and added with my usual despondency, ‘I’ll have to check my dates, but I’ll try to come.’

Fortunately, Kitty descended on her with ludicrous cheers for the new choir, so I scooped up my bag and fled, dashing home before my elation exploded.

What a stroke of luck! Now all I have to do is check that she keeps her WVS meeting and hone my plan for the births.

I have become quite the professional, you see, Clara. My herbal potion brings babies out with impressive speed. Now, to give the potion to Mrs Winthrop, who is a timid, compliant sort of woman, will be no problem. This is her fourth baby, so I expect the baby to pop out within the hour. After calling out that it’s a boy, I’ll pretend the baby’s not breathing proper, that I need to whisk it to my house for resuscitation with the mechanical ventilator. (Who’s to know I haven’t got one?)

Hattie, however, will be a more difficult matter. Not only will it be gruelling to get her to take the potion as she is so nauseatingly proper, but then it’ll take four or five hours to get the baby out, it being her first child. Meanwhile, I’ll need someone to watch the Winthrop child.

That’s why I decided to enlist the Winthrops’ maid, Elsie. Not only could she lend a sense of propriety by coming with me when I whisk off the Winthrops’ baby, but she could also help look after the mite while I’m busy with Hattie. So when I spotted her in the shop yesterday, I invited her for tea and mentioned that I may be in need of her assistance at the birth.

‘What you’re saying is you want me to help with Mrs Winthrop’s birth, and then come to your house if you have to take the baby away for emergency help?’ She screwed her eyes up with distaste, suspecting it was down-and-dirty business. But she didn’t ask questions, came from a background like that, see – ask no questions, take the money, leg it.

‘That’s right, love,’ I said, offering her another biscuit. ‘I’d just need someone to help me look after the baby for a short while.’

She took two biscuits, and I could see her thinking it through, her beautiful face pondering like a deer listening for danger. ‘I could do it,’ she said at last. ‘But how much will you give me?’

‘I’d give you ten bob for your trouble, provided you kept quiet.’

‘Ten bob?’ she uttered. ‘More like ten quid, I’d say.’

‘Five quid then,’ I said. What a pain this girl was being!