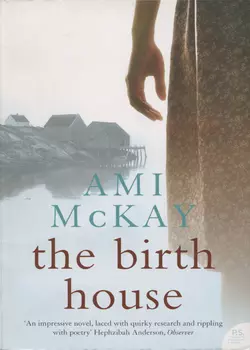

The Birth House

Ami McKay

Spanning the 20th century Ami McKay takes a primitive and superstitious rural community in Nova Scotia and creates a rich tableau of characters to tell the story of childbirth from its most secretive early practices to modern maternity as we know it.Epic and enchanting, ‘The Birth House’ is a gripping saga about a midwife's struggles in the wilds of Nova Scotia.As a child in the small village of Scot's Bay, Dora Rare – the first female in five generations of Rares – is befriended by Miss Babineau, an elderly midwife with a kitchen filled with folk remedies and a talent for telling tales. Dora becomes her apprentice at the outset of World War I, and together they help women through difficult births, unwanted pregnancies and even unfulfilling marriages.But their traditions and methods are threatened when a doctor comes to town with promises of painless childbirth, and sets about undermining Dora's credibility. Death and deception, accusations and exile follow, as Dora and her friends fight to protect each other and the women's wisdom of their community. Hauntingly written and alive with historical detail, ‘The Birth House’ is an unforgettable, page-turning debut.

AMI McKAY

The Birth House

Copyright (#ulink_b22f12aa-c30a-5d52-b3b7-398abd3c710e)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercolins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2006

Copyright © Ami McKay 2006

PS Section copyright © Rose Gaete 2007, except ‘The Occasional Knitter’s Society’, ‘A Brief History of the Vibrator’ and ‘The Halifax Explosion’ copyright © Ami McKay 2006 and ‘What Inspired The Birth House?’ copyright © Ami McKay 2007

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Ami McKay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007233304

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2012 ISBN: 9780007391486

Version: 2017-01-12

Praise For The Birth House (#ulink_02b0274e-f887-5e82-ac27-8a9eeed9eaac)

From the reviews of The Birth House:

‘Modern medicine clashes with folk remedies in … McKay’s stirring saga of midwifery in Nova Scotia … An impressive novel, laced with quirky research and rippling with muscular poetry. As you’d expect, there are plenty of messy scenes starring wild-haired, blood-slicked mums-to-be, yet beyond the gore and folksy detail, a quieter drama plays out: that of women asserting their right to control their bodies’

HEPHZIBAH ANDERSON, Observer

‘McKay’s achievement lies in shaping a candidly told story rich in sub-plots about what is an effective, non-sentimental feminist polemic confronting domestic violence, marital rape and incest … A dramatic, convincing novel … unusual, vigorous and disciplined’

Irish Times

‘This is a truly captivating read … [McKay] weaves lyrical detail of the natural beauty in which these pioneer families live with the pricklier reality of the First World War era, when centuries-old folk wisdom collides with modern science. The underlying theme of the shared strength that women give each other in hard circumstances lends this tale a solid bedrock’

She

‘Ami McKay cleverly points up the good and the bad in both old and new attitudes, while contemporary newspaper reports and advertisements illustrate the pace of change’

Guardian

‘Mckay makes ingenious use of diary entries, letters, newspaper clippings real and imagined, invitations, and old wives’ remedies. Despite (or because of) all this stylistic variety, The Birth House builds up a strong narrative momentum. Intelligent, quirky, passionate, and funny, it deserves a wide readership and a long shelf life’

Quill & Quire

‘The Birth House has a spirited momentum, and it is difficult not to be swept along by it … [McKay’s] writing is often beautiful, with colourful turns of phrase that mirror the earthiness of her setting … She does know her way around a good story’

Sunday Business Post

‘A gripping tale of times and traditions long past’

Belfast Telegraph

‘[McKay] … stylishly re-creates the pioneer days of Nova Scotia with a fine eye for descriptive detail and history … Wise, wry, witty and yet deeply serious’

Historical Novels Review

‘The Birth House is an astonishing debut, a book that will break your heart and take your breath away … To read The Birth Houseis to enter a world, a richly imagined and keenly observed fictional totality without seams of doubt, without any fissure of disbelief. It is a world from which one will be reluctant to depart. The novel will linger in the reader’s memory as the finest fiction always does. To say this is a powerful debut is to damn Ami McKay’s novel with too faint praise; it is an altogether remarkable work from an impressive new talent’

The Ottawa Citizen

For my husband, Ian

My heart, my love, my home

Contents

Cover (#uefd4bc6b-66f7-5169-94c5-8c14f061bdcf)

Title Page (#ud12cf106-aa88-5e36-9998-10b8d0ad554c)

Copyright (#ulink_b2ca4ed5-ae53-5709-b261-71da63e09b8a)

Praise for The Birth House (#ulink_69094016-ce70-55a8-b853-e0f43871024e)

Dedication (#uafa05624-8701-541e-a65e-6b3921932a54)

Prologue (#ulink_1dc44d6f-0458-52a4-ab93-e047f78d8dd4)

Part One (#ulink_53c32b34-d164-50e2-87c0-e0e8da884123)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_0b4531bb-4722-5b22-9d28-5e523b31926e)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_e1429435-82c1-5248-b8cb-c013fac36fcb)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_f6fa4477-bb47-5ba2-8a06-208cc3809451)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_ed3912ca-9846-56d4-a18c-d35a7f1bcaf1)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_4048aa1d-8949-5512-8d40-adbb29832107)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_8e14ad7e-ac0d-5ead-901c-c77b600d792a)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_6107f70a-252c-5057-a4cc-b5b0d2e08c8a)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_b0a230fa-453d-5b0d-a2d6-99c59f0faca5)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_65c3a8c8-4112-581b-9cfc-35b45ba6dd45)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_5b13404d-1fee-50f6-9c33-62a26142d0ca)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes from the Willow Book

The Midwife’s Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. Ideas interviews & features … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the book (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_ade1f09d-3435-5e2a-92e3-cb541f29bdc3)

MY HOUSE STANDS at the edge of the earth. Together, the house and I have held strong against the churning tides of Fundy. Two sisters, stubborn in our bones.

My father, Judah Rare, built this farmhouse in 1917. It was my wedding gift. A strong house for a Rare woman, he said. I was eighteen. He and his five brothers, shipbuilders by trade, raised her worthy from timbers born on my grandfather’s land. Oak for stability and certainty, yellow birch for new life and change, spruce for protection from the world outside. Father was an intuitive carpenter, carrying out his work like holy ritual. His callused hands, veined with pride, had a memory for measure and a knowing of what it takes to withstand the sea.

Strength and a sense of knowing, that’s what you have to have to live in the Bay. Each morning you set your sights on the tasks ahead and hope that when the day is done you’re farther along than when you started. Our little village, perched on the crook of God’s finger, has always been ruled by storm and season. The men did whatever they had to do to get by. They joked with one another in fire-warmed kitchens after sunset, smoking their pipes, someone bringing out a fiddle … laughing as they chorused, no matter how rough, we can take it. The seasons were reflected in their faces, and in the movement of their bodies. When it was time for the shad, herring and cod to come in, they were fishermen, dark with tiresome wet from the sea. When the deer began to huddle on the back of the mountain, they became hunters and woodsmen. When spring came, they worked the green-scented earth, planting crops that would keep, potatoes, cabbage, carrots, turnips. Summer saw their weathered hands building ships and haying fields, and sunsets that ribboned over the water, daring the skies to turn night. The long days were filled with pride and ceremony as mighty sailing ships were launched from the shore. The Lauretta, The Reward, The Nordica, The Bluebird, The Huntley. My father said he’d scour two hundred acres of forest just to find the perfect trees to build a three-masted schooner. Tall yellow birch, gently arched by northwesterly winds, was highly prized. He could spot the keel in a tree’s curve and shadow, the return of the tide set in the grain.

Men wagered their lives with the sea for the honour of these vessels. Each morning they watched for the signs. Red skies in morning, sailors take warning. Each night they looked to the heavens, spotting starry creatures, or the point of a dragon’s tail. They told themselves that these were promises from God, that He would keep the wiry cold fingers of the sea from grabbing at them, from taking their lives. Sometimes men were taken. On those dark days the men who were left behind sat down together and made conversation of every detail, hitching truth to wives’ tales while mending their nets.

As the men bargained with the elements, the women tended to matters at home. They bartered with each other to fill their pantries and clothe their children. Grandmothers, aunts and sisters taught one another to stitch and cook and spin. On Sunday mornings mothers bent their knees between the stalwart pews at the Union Church, praying they would have enough. With hymnals clutched against their breasts, they told the Lord they would be ever faithful if their husbands were spared.

When husbands, fathers and sons were kept out in the fog longer than was safe, the women stood at their windows, holding their lamps, a chorus of lady moons beckoning their lovers back to shore. Waiting, they hushed their children to sleep and listened for the voice of the moon in the crashing waves. In the secret of the night, mothers whispered to their daughters that only the moon could force the waters to submit. It was the moon’s voice that called the men home, her voice that turned the tides of womanhood, her voice that pulled their babies into the light of birth.

My house became the birth house. That’s what the women came to call it, knocking on the door, ripe with child, water breaking on the porch. First-time mothers full of questions, young girls in trouble and seasoned women with a brood already at home. (I called those babies “toesies,” because they were more than their mamas could count on their fingers.) They all came to the house, wailing and keening their babies into the world. I wiped their feverish necks with cool, moist cloths, spooned porridge and hot tea into their tired bodies, talked them back from outside of themselves.

Ginny, she had two …

Sadie Loomer, she had a girl here.

Precious, she had twins … twice.

Celia had six boys, but she was married to my brother Albert … Rare men always have boys.

Iris Rose, she had Wrennie …

All I ever wanted was to keep them safe.

(#ulink_c2caa289-88fc-569e-8aee-9f8203cc1a79)

Around the year 1760, a ship of Scotch immigrants came to be wrecked on the shores of this place. Although the vessel was lost, her passengers and crew managed to find shelter here. They struggled through the winter – many taking ill, the women losing their children, the men making the difficult journey down North Mountain to the valley below, carrying sacks of potatoes and other goods back to their temporary home, now called Scots Bay.

In the spring, when all who had been stranded chose to make their way to more established communities, the daughter of the ship’s captain, Annie MacIssac, stayed behind. She had fallen in love with a Mi’kmaq man she called Silent Rare.

On the evening of a full mune in June, Silent went out in his canoe to catch the shad that were spawning around the tip of Cape Split. As the night wore on, Annie began to worry that some ill had befallen her love. She looked across the water for signs of him but found nothing. She walked to the cove where they had first met and began to call out to him, promising her heart, her fidelity and a thousand sons to his name. The moon, seeing Annie’s sadness, began to sing, forcing the waves inland, strong and fast, bringing Silent safely back to his lover.

Since that time, every child born from the Rare name has been male, and even now, when the moon is full, you can hear her voice, the voice of the moon, singing the sailors home.

A RARE FAMILY HISTORY, 1850

1 (#ulink_3706fc3e-4dd2-5009-b959-f23c8c2224a1)

EVER SINCE I CAN REMEMBER, people have had more than enough to say about me. As the only daughter in five generations of Rares, most figure I was changed by faeries or not my father’s child. Mother works and prays too hard to have anyone but those with the cruellest of tongues doubt her devotion to my father. When there’s no good explanation for something, people of the Bay find it easier to believe in mermaids and moss babies, to call it witchery and be done with it. Long after the New England Planters’ seed wore the Mi’kmaq out of my family’s blood, I was born with coal black hair, cinnamon skin and a caul over my face. A foretelling. A sign. A gift that supposedly allows me to talk to animals, see people’s deaths and hear the whisperings of spirits. A charm for protection against drowning.

When one of Laird Jessup’s Highland heifers gave birth to a three-legged albino calf, talk followed and people tried to guess what could have made such a creature. In the end, most people blamed me for it. I had witnessed the cow bawling her calf onto the ground. I had been the one who ran to the Jessups’ to tell the young farmer about the strange thing that had happened. Dora talked to ghosts, Dora ate bat soup, Dora slit the Devil’s throat and flew over the chicken coop. My classmates chanted that verse between the slats of the garden gate, along with all the other words their parents taught them not to say. Of course, there are plenty of schoolyard stories about Miss B. too, most of them ending with, if your cat or your baby goes missing you’ll know where to find the bones. It’s talk like that that’s made us such good friends. Miss B. says she’s glad for gossip. “It keep folks from comin’ to places they don’t belong.”

Most days I wake up and say a prayer. I want, I wish, I wait for something to happen to me. While I thank God for all good things, I don’t say this verse to Him, or to Jesus or even to Mary. They are far too busy to be worrying about the affairs and wishes of my heart. No, I say my prayer more to the air than anything else, hoping it might catch on the wind and find its way to anything, to something that’s mine. Mother says, a young lady should take care with what she wishes for. I’m beginning to think she’s right.

Yesterday was fair for a Saturday in October—warm, with no wind and clear skies—what most people call fool’s blue. It’s the kind of sky that begs you to sit and look at it all day. Once it’s got you, you’ll soon forget whatever chores need to be done, and before you know it, the day’s gone and you’ve forgotten the luck that’s to be lost when you don’t get your laundry and yourself in out of the cold. Mother must not have noticed it … before breakfast was over, she’d already washed and hung two baskets of laundry and gotten a bushel of turnips ready for Charlie and me to take to Aunt Fran’s. On the way home, I spotted a buggy tearing up the road. Before the thing could run us over, the driver pulled the horses to a stop, kicking up rocks and dust all over the place. Tom Ketch was driving, and Miss Babineau sat in the seat next to him. She called out to me, “Goin’ out to Deer Glen to catch a baby and I needs an extra pair of hands. Come on, Dora.”

Even though I’d been visiting her since I was a little girl (stopping by to talk to her while she gardened, or bringing her packages up from the post), I was surprised she’d asked me to come along. When my younger brothers were born and Miss B. came to the house, I begged to stay, but my parents sent me to Aunt Fran’s instead. Outside of watching farmyard animals and a few litters of pups, I didn’t have much experience with birthing. I shook my head and refused. “You should ask someone else. I’ve never attended a birth …”

She scowled at me. “How old are you now, fifteen, sixteen?”

“Seventeen.”

She laughed and reached out her wrinkled hand to me. “Mary-be. I was half your age when I first started helpin’ to catch babies. You’ve been pesterin’ me about everything under the sun since you were old enough to talk. You’ll do just fine.”

Marie Babineau’s voice carries the sound of two places: the dancing, Cajun truth of her Louisiana past and the quiet-steady way of talk that comes from always working at something, from living in the Bay. Some say she’s a witch, others say she’s more of an angel. Either way, most of the girls in the Bay (including me) have the middle initial of M, for Marie. She’s not a blood relative to anyone here, but we’ve always done our part to help take care of her. My brothers chop her firewood and put it up for the winter while Father makes sure her windows and the roof on her cabin are sound. Whenever we have extra preserves, or a loaf of bread, or a basket of apples, Mother sends me to deliver them to Miss B. “She helped bring all you children into this world, and she saved your life, Dora. Brought your fever down when there was nothing else I could do. Anything we have is hers. Anything she asks, we do.”

As I pulled myself up to sit next to her, she turned and shouted to Charlie, “Tell your mama not to worry, I’ll have Dora home for supper tomorrow.” We sat tight, three across the driver’s seat, with a falling-down wagon dragging behind.

Miss B. began to question Tom, her voice calm and steady. “How’s your mama sound?”

“Moanin’ a lot. Then every once in a while she’ll hold her belly and squeal like a stuck pig.”

“How long she been that way?”

“It started first thing this morning. She was moonin’ around, sayin’ she couldn’t squat to milk the goat, that it hurt too much. Father made her do it anyways, said she was being lazy … then he made her muck the stalls too.”

“Is she bleedin’?”

Tom kept his eyes on the road ahead. “Not sure. All I know is, one minute she was standin’ in the kitchen, peelin’ potatoes, and then all of a sudden she was doubled right over. Father got angry with her, said he was hungry and she’d better get on with what she was doin’. When she didn’t, he shoves her down to the floor. After that, hard as she tried, she couldn’t stand on her own, so she just curled up and cried.” He gave a sharp whistle to the horses to keep them in the middle of the rutted road, his jaw set hard, like someone waiting to get punched in the gut. “She didn’t want me to bother you with it, said she’d be alright, but I never seen her hurtin’ so bad before. I came as soon as I could, as soon as he left to go down to my uncle’s place.”

“Will he stay out long?”

“More’n likely all night. Especially if they gets t’drinkin’, which they always do.”

Tom’s the oldest of the twelve Ketch children. He’s fifteen, maybe sixteen, I’d guess. I think about Tom from time to time, when I run out of dreams about the fine gentlemen in Jane Austen’s novels. He’s got a kind face, even when it’s filthy, and Mother always says she hopes he’ll find a way to make something of himself instead of turning out to be like his father, Brady. I can tell she prefers I not mention the Ketches at all. I think it makes her scared that I’ll not make something of myself and turn out to be like Tom’s mother, Experience.

The Ketch family has always lived in Deer Glen. It’s a crooked, narrow hollow, just outside of the Bay, twisting right through the mountain until you can see the red cliffs of Blomidon. No one here would claim it to be anything more than the dip in the road that lets you know you’re almost home. The land is too rocky and steep for farming and too far from the shore for making a life as a fisherman or a shipbuilder. Too far for a pleasant walk. The Ketches suffer along, selling homebrew from a still in the woods and making whatever they can from the hunters who come from away, men who hope to kill the white doe that’s said to live in the Glen. In deer season they block off the road, Brady at one end, his brother Garrett at the other. They stand, shotguns strapped to their backs, waiting to escort the trophy hunters who come from Halifax, the Annapolis Valley, and faraway places like New York and Boston. The Ketch brothers charge a pretty penny for their services, especially since they’re selling lies. It’s true, there’s been a white doe spotted on North Mountain, but it doesn’t live in Deer Glen. It lives in the woods behind Miss B.’s cabin, where she feeds it out of her hand, like a pet. I’ve never seen it, but I’ve heard her call to it on occasion, walking through the trees singing, Lait-Lait, Lune-Lune. Father said he saw it once, that she’s the colour of sweet Guernsey cream, with one corner of her rump faintly speckled. He came home with nothing that day and told Mother, “It would have been wrong to take it.” Shortly after, at a Sons of Temperance meeting, the men of the Bay all pledged never to kill it. They all agreed that there’s sin in taking the life of something so pure.

It was nearly dark when we got to the Ketch house, its clapboards loose and wanting for paint, the screen door left hanging. The inside wasn’t much better. A picked-over loaf of bread, along with pots, pans and empty canning jars were crowded together on the table, all needing to be cleared. Attempts had been made at keeping a proper house, but somehow the efforts had gone wrong, every time. The curtains were bright at the top, still showing white, with a cheerful flowered print. Halfway to the floor, little hands had worn stains into the fabric, and the ends were frayed from the tug and pull of cats’ claws. No matter how fresh and clean a start they may have had, the towels in the kitchen, the wallpaper and rugs, even the dress on the little girl who greeted us at the door, all showed the same pattern, their middles stained, their edges worn and dirty. The entire house smelled sour and neglected.

Experience Ketch was hunched over in her bed, clutching her belly. Her oldest daughter, Iris Rose, was standing next to her, dipping a rag in a bucket of water then offering it to her mother. Mrs. Ketch took the worn cloth and clenched it between her teeth, sucking and spitting while she rocked back and forth.

Miss B. sat on the edge of the bed and held Mrs. Ketch’s hand. She talked the woman through her pains enough to get her to sit up and drink some tea. The midwife wrapped her wrinkled fingers around Mrs. Ketch’s wrist, closed her eyes and counted in French. She pinched the ends of Mrs. Ketch’s fingertips and then pulled her eyelids away from her pink, teary eyes. “Your blood’s weak.” Miss B. pushed the blankets back and pulled up Mrs. Ketch’s bloodstained skirts. Her hands kneaded their way around the tired woman’s swollen belly, feeling over her stretched skin, making the sign of the cross. After washing her hands several times, she slipped her fingers between Mrs. Ketch’s legs and shook her head. “This baby has to come today.”

Mrs. Ketch moaned. “It’s too soon.”

“Your pains is too far gone and I can’t turn you back. If you don’t birth this child today, all your other babies don’t gonna have a mama.”

“I don’t want it.”

Iris Rose knelt by the bed and pleaded with her mother. “Please, Mama, do what she says.”

The girl’s much younger than me, twelve at the most, but she’s as much mother as she is child. From time to time she’ll show up at the schoolhouse, dragging as many of her brothers and sisters behind her as she can. She barks at the boys to take off their hats, scolds the girls as she tugs on their braids, making her voice as big and rough as an old granny’s. For all her trying, it always turns out the same. By the time the snow flies, the desks of the Ketch children are empty again.

Mrs. Ketch needs them home, I guess. I’ve heard that each of the older ones is assigned a little one to bathe, dress, feed and look after, so they don’t get lost in the clutter of a house filled with dirty dishes and barn cats. With six brothers of my own, I think I can say there’s such a thing as too many.

When Mrs. Ketch’s wailing went on, Tom and the older boys disappeared out to the barn. With Iris Rose’s help, I tucked the rest of the children into an upstairs room. She stood in the doorway with her arms folded across her chest. “Now don’t you make another sound, or Daddy’ll come running through the hollow and up these stairs with an alder switch!” The room went quiet. Six small greasy heads went to the floor, six bellies breathed shallow and scared.

“Can I watch?” Iris Rose asked.

“If you promise not to say anything.”

“I’ll be silent. I swear.”

I left her on the stairs, peeking through the broken, crooked pickets of the banister.

Miss B. and I turned back the straw mattress and tied sheets to the bedposts. She tugged hard at them. “See now, Mrs. Ketch, you know what’s to do … when the time comes, you gots to hold on for dear life and push that baby out.” Miss B. motioned for me to steady Mrs. Ketch’s shaking knees. “And it’s comin’ fast and hard as high tide on a full moon. Pousser!”

Mrs. Ketch bent her chin to her chest, the veins on her neck throbbing. “Let me die, dear Lord. Please let me die.”

Miss B. laughed. “How many times you been through this, thirteen, fourteen? You should know by now, the Lord ain’t like most men, He ain’t gonna just take you home when you ask for it …”

Just last Sunday Reverend Norton went on and on about the trespasses of Eve, pounding his fist on the pulpit, his face all red and puffed up as he spit to the side between the words original and sin. While he talked at good length about the evils of temptation and the curse Eve had brought upon all women, he never mentioned the stink of it. I never imagined that “the woman’s tithe for the civilized world” would smell so rusted, so bitter.

I kept the fire in the stove going, unpacked clean sheets from Miss B.’s bag, did whatever she told me to do, but no matter how busy I made myself, my stomach ached and my hands felt heavy and useless. I don’t think my nervousness came from it being my first birth, or even from seeing such pain and struggle in a woman, but more from hearing the sadness, the wanting, in Mrs. Ketch’s cries. Nothing we did seemed to help. She sobbed and cursed, her wailing and Miss B.’s coaxing going on for an hour or more, I’d guess, or at least long enough for Mrs. Ketch to give up on a miracle and have a baby boy.

He was a sad, tiny thing. His flesh was like onion skin; the blue of his veins showed right through. If I had looked any harder at his weak little body, I think I might have seen his heart. Miss B. bundled him up in flannel sheets and handed him to Mrs. Ketch. “Hold him, now, put your chest to his so he knows what it’s like to be alive.” But Experience Ketch didn’t want her baby. She didn’t want to hold him or look at him or have him anywhere near. “Get that thing away from me. I got twelve more than I can handle anyways.”

I couldn’t stand it. I took him from Miss B. and pulled him close. I whispered in his ear, “I’ll take you home with me. I’ll take you for my own.”

Out of the corner of my eye I saw Iris Rose run up the stairs. I turned to Miss B. “He’s looking so blue, his arms, his legs, his chest. His breath is barely there.”

“He’s born too soon.” She made the sign of the cross on his wrinkled brow. “If he’d been born three, four weeks later, I could spoon alder tea with brandy in his mouth, make a bed for him in the warmin’ box of the cookstove and hope he pinked up, but as it is …”

I stopped her from going on. “Tell me what to do. I have to try.”

Miss B. shook her head. “If you can’t see him through to the other side, then you should just go on home. Mary and the angels will soon take care of him. I have to see to his mama.”

I sat in the corner and held tight to the dying child.

Miss B. wrapped a blanket around us. “Some babies ain’t meant for this world. All you can do is keep him safe until his angel comes.”

“There’s nothing else I can do?”

She leaned over and whispered in my ear. “Pray for him, and pray for this house too.”

2 (#ulink_313f359b-7f33-53cc-a212-99420aabe7e9)

BETWEEN MY PRAYERS and Miss B.’s spooning porridge into Mrs. Ketch’s mouth, the baby died. It was almost dawn when Brady Ketch came home. He stomped through the house, drunk and demanding to be fed. “Experience Ketch, get outta that bed and get me some food.” The poor woman tried to get up, as if nothing had troubled her at all, but Miss B. held her down. “You need rest. Lobelia tea and rest, then more tea and more rest. At least three days to get your strength, but a week would be best. If you don’t, you gonna bleed ‘til you’re dead.”

Mr. Ketch staggered, reaching for the bundle of blankets I was holding in my arms. “Let me have a look-see there, girl. What’d we get this time, wife? Another boy, I hope. Girls don’t eat as much, but they take their toll every-ways else. I don’t trust nothin’ that can’t piss standin’ up.” He pinned me against the wall, his dark mouth leaving the skunky smell of his breath in my face. “Ain’t you pretty … you Judah Rare’s girl, right?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Your daddy’s got the right idea. How’d he manage to get all boys and just one pretty little thing like you? Bet you come in handy when your mama gets tired. He’s one lucky son of a bitch, I’d say.”

Mrs. Ketch hissed at her husband. “Leave her be, Brady.”

He pulled back the blankets to look at the child. “I’m just lookin’ at what’s mine.”

I stood still while he pinched at the baby’s thin, blue cheeks. “Hey there, little critter, ain’t you gonna say ‘hello’ to your—” He stopped and pulled his hand away, his curiosity giving way to confusion and then to anger. He turned and stared at Miss B. “What’d you do to it?” Before she could answer, he grabbed her by her shoulders. “Looks to me like you killed my child and put my wife half-dead on her back.” Brady Ketch slid his hands around Miss B.’s throat, slipping his fingers through her rosary beads. “What’s to keep me from taking you back in the glen and snappin’ your wattled old witch’s neck?”

An iron skillet lay on the floor by the cookstove. A doorstop shaped like a dog sat in the corner, one ear and the snout of its nose chipped away. I could’ve killed Brady Ketch and not felt a minute’s worth of guilt. “God sees what you do, Mr. Ketch.”

He let go of Miss B. and made his way back to me, smiling, leaning into my body and stroking my hair. “Now, don’t you worry, little girl. Miss Babineau knows I’d never mean her any real harm. It’s just sometimes a woman needs a man to set her right. Says so in the Bible.”

Miss B. started packing up her bag. “See that she gets her rest. Three days off her feet, no less.” She moved towards the door. “Come on, Dora.”

“That won’t do.” Mr. Ketch stood in front of the door. “She can’t just take to bed for days whenever she feels like it. There’s things that need to get done around here. You gotta fix her. Now.”

Miss B. stared at him. “I told you, she needs bedrest. Three days and she’ll be good as new.”

He crossed his arms in front of his chest. “That Dr. Thomas, down Canning way, he’d know how to make her right. When Tommy snapped his wrist, the doc fixed it up so he could use it right away. Tied it up nice and clean, give him a few pills, and Tom was chopping wood that afternoon.”

“And you can afford a fancy doctor always runnin’ up the mountain to fix your family?”

Brady pretended to hold a rifle in his arms, pointing his finger past Miss B. and out the window. He clucked his tongue in his mouth and moved his hands as if to cock the gun. “Let’s just say the doc and I … we have a gentleman’s agreement when it comes to that sweet white doe everyone’s always lookin’ to bag.” He grinned as he slowly changed position, now pointing at Miss B.’s heart, squinting one eye to take aim. “And don’t think I don’t know where to find her.”

Miss B. pushed his arm away and started again for the door. “Well, ain’t that fine.”

Brady opened the door and shoved Miss B. onto the stoop. As I started to hand the child’s body to him, Miss B. called out to Mrs. Ketch.

“You send Tom to get me if the bleeding gets any worse.”

Mrs. Ketch rolled over, her voice sounding tired and sad. “I can take care of myself … Just get out now, and take the baby with you. I don’t want that ugly thing in my house.”

Miss B. sang little French prayers to the dead baby boy and wrapped him in one of the lace kerchiefs she’s always tatting on her lap. We laid him in a butter box, tucked October’s last blossoms from the pot marigolds and asters all around him and nailed the tiny coffin shut. She vanished between the alders in back of her cabin. I walked behind, following the sound of her voice, cradling the box in my arms, trying to make up for his mother not loving him. If only my love had been able to raise him from the dead.

Miss B. whispered. “Shhhh. Le jardin des morts, the garden of the dead, the garden of lost souls.” In the centre of a mossy grove of spruce was a tall tree stump. The likeness of a woman had been carved into it … the Virgin Mary, standing on a crescent moon, her face, her breasts, her hands, all delicate and sweet. All around her, strings of hollowed-out whelks and moon shells hung with tattered bits of lace from the branches, like the wings of angels.

Grandmothers and old fishermen have long said that the woods of Scots Bay have cold, secret spots, places of foxfire and spirits. “Never chase a shadow in the trees. You can’t be sure it’s not your own.” Charlie must have chased me a thousand times down the old logging road in back of our land, both of us running into the woods behind Miss B.’s place, shouting, witched away, witched away, today’s the day we’ll be witched away. We’d spent hours weaving crowns from alder twigs, feathers, porcupine quills and curled bits of birch bark. We’d imagined faerie houses and gnome caves in the tangled roots of a spruce that had been brought down by the wind. We’d come home, tired and hungry, declaring we’d found the hidden treasure of Amethyst Cove but had lost it (yet again) to a wicked band of thieves. In all our time spent in the forest we never found or imagined anything like this.

Miss B. took off her shoes. “Can’t let no outside world touch Mary’s ground.”

She began to make her way around the grove, tracing crosses in the air, circling closer and closer to the Mary tree. I slipped off my boots and followed. When Miss B. was finished, she knelt at the base of the tree and began to dig at the moss. Beneath the dirt and stones was a thick handle of braided rope. Together we pulled up a heavy wooden door that was covering a deep hole in the ground. “Our Lady will watch over him now.” She took the tiny coffin, tied a length of rope around it and lowered it into the dark grave. “Holy Mother, Star of the Sea, take this little soul with thee.” She let go of the rope and took my hands. “You gots to give him a name. Just say it once, so he knows he’s been born.”

I closed my eyes and whispered “Darcy,” after Elizabeth Bennett’s sweetheart in Pride and Prejudice. Because he should have lived; he should have been loved.

I’ve seen the runt of a litter die. When there are too many kittens or too many piglets, the mother can’t keep up with them all. The runt gets shoved out by the others and the mother acts as if she doesn’t even know it’s there. Maybe Mrs. Ketch knew Darcy wouldn’t live from the start, maybe she pushed him away so she wouldn’t love him, so she wouldn’t hurt.

It’s a disgusting mess we come through to be born, the sticky-wet of blood and afterbirth, mother wailing, child crying … the helpless soft spot at the top of its head pulsing, waiting to be kissed. Our parents and teachers say it’s a miracle, but it’s not. It’s going to happen no matter what, there’s no choice in the matter. To my mind, a miracle is something that could go one way or another. The fact that something happens, when by all rights it shouldn’t, is what makes us take notice, it’s what saints are made of, it takes the breath away. How a mother comes to love her child, her caring at all for this thing that’s made her heavy, lopsided and slow, this thing that made her wish she were dead … that’s the miracle.

3 (#ulink_863894db-8997-552b-80d9-d923afb0fcf0)

LATE IN NOVEMBER we bank the house, always on a Saturday. Even with all nine of us stuffing baskets of eelgrass around the house’s foundation, it still takes a good part of the day to get it done.

Just after high tide, I went down to the marsh with Father and my two older brothers, Albert and Borden, to pitch the tangled heaps of grass onto the wagon. Mother stayed behind with the rest of the boys to pound stakes and build a short stay fence that would hold the grass in tight to the stones. By December, when most families have finished the job, it looks like all the houses in the Bay have settled in giant bird’s nests, ready to roost for the winter. Uncle Irwin and Aunt Fran pay to have neat, tight bales stacked around their house. Others swear by spruce bows all heaped up on the west side, facing the water. Father says he’s too smart to waste good hay and that the porcupines’ll clean the needles off the spruce in one meal, so we’re stuck doing things the hard way.

At least the twins, Forest and Gord, are big enough to help this year. Even though they’ve turned eight, they still act like whimpering puppies, forever tugging at my sleeves, following me, calling my name. Every day we walk the Three Brooks Road, the same round loop. Past Laird Jessup’s place, then down along the pastures and the deep little spot where the brooks all meet, then on around to school. Sometimes we go down to the beach to play, or out to the wharf to fetch Father, who always takes us back on the other side, the Sunday side of the loop. Up to the church, then on past Aunt Fran’s place, up to Spider Hill and home again. Boys ahead and boys behind. I’m the only girl stuck in the middle of six boys who spend most of their days poking, laughing and wrestling together as they trip and drag their muddy boots through my life.

Mother says I shouldn’t complain. She’s got her own rounds to make. Up before dawn, down to the kitchen, out to the barn, back to the kitchen, down to Aunt Fran’s, over to the church, back to her kitchen. She holds the boys close to her every chance she gets. They wiggle and roll their eyes as she kisses the tops of their messy heads. She sighs as she lets them go, watching them run off to play “Things aren’t as certain as they used to be.” She’s not talking about their age or the fact that they’re always outgrowing their shoes. It’s the war, she means to say, but won’t. It’s the war that she’s afraid of, that’s got her wondering how long she can keep her boys at home, that has us listening to gossip and reading headlines and moving in circles, as if we might cast a spell of sameness to keep the rest of the world away.

Banking the house took so long that I was late getting to Miss B.’s. I have been visiting her every Saturday since we buried dear little Darcy. It’s a relief to get to her door, to sit at her kitchen table, to be able to breathe and sigh and even weep over my small, blue memory of him. I’ve told the tale only once, to Mother. When I came to the part where Mrs. Ketch refused the child, it was all she could do not to shake and cry all over me. Instead, she held her breath, closed her eyes and whispered, “God forgive, God bless.” Although I can still feel the weight of his body in the crook of my arm, I won’t put her through hearing of it again. She wasn’t there; she doesn’t need to know how much it still comes to my mind. And now there’s no one else to tell. Father wouldn’t know what to say. He’d be angry with me for bringing it up at all. My dear cousin, Precious, though she hangs on every word of a good story, is still Aunt Fran’s child … any news that’s ugly or sad is not allowed in their house: words of sensation and death leave a sinful mark on the walls of a good christian home. (Aunt Fran prefers to carry her gossip under her hat and deliver it to everyone else’s door.)

I’m Miss B.’s only guest on Saturdays, or any other day of the week. I’m the only person in all of Scots Bay who dares make a friendly call to the old midwife. As a child, I was always happy when Mother had reason to send me to Miss B.’s cabin, happy to walk down the old logging road, away from Three Brooks Road and our house full of boys, happy just to sit with her in her garden, or in her kitchen filled with, as she says, “things to make you wonder.” A tarnished, round looking-glass hangs by the door. Jars and bottles of herbs, salves and tinctures line her cupboards. Feathered wings are tacked up over the door and every window. Crow, sparrow, dove, hawk, owl. One large, dark wooden crucifix hangs over her bed, while the rest of the two-room log cabin—every wall, shelf or tabletop—is covered with tallow candles and a thousand Marys. I did my best not to ask questions, but if she spotted me staring at something, she’d be quick to recite a verse or sing a song about whatever it was. (Although sometimes she’d just smile and say, “Never mind that just now, Dora. If I told you, you’d never believe.”)

It’s long been understood that, unless you’re a woman who’s expecting, or you’ve got an ailment that can’t be cured, you’re better off not to bother with her. Never break bread with midwives or witches; your skin’ll soon crawl with boils, hives and itches. I don’t know who’s worse about spreading such rumours, schoolyard tattletales or the ladies who run the White Rose Temperance Society. Those women never give Marie Babineau more than three words about the weather, some cold today, fog comin’ in, strong south wind … They’re careful not to form their words into a question or to invite her into their conversations. They ignore her gap-toothed smile and never look twice at her brown, wrinkled face. They spread loudmouthed gossip about the green stink they say comes from her breath and “out every wine-soaked pore of her body.” Aunt Fran says it’s like soured, mouldy cabbage. Mrs. Trude Hutner argues, “I’d say it’s more like a wet dog that’s been nosing around a skunk.” Most of the Ladies of the White Rose don’t have babies underfoot anymore, so they feel they haven’t any need for Miss B. Along with their age, comfortable size and the scattered prickly hairs sticking from their chins, they’ve forgotten Miss B.’s sweetness and everything she’s done for them. They forget that when you’re close to her, eye to eye, she smells as honest and kind as the better parts of hand-picked herbs and fresh-ground spices. Her sighs are full of lavender, ginger and fresh-brewed coffee … her laughter leaves hints of chicory, pepper and clove.

Always keep at least three pots on the stove. One for tea, one for the simples and one for coffee with blue sailors. “You know I never touch the coffee but my one cup that gets me goin’ of a morning. Any more’n that and I gets the jumps,” she says as she bounces in her rocking chair. “I only lets it go on sim-merin’ ‘cause I like the black, grumbling smell of it. Brings a man to mind, it does.”

She makes a great show when I visit—fussing over her iron pots and teacups, serving lavender tea and beignets, each one a plump, warm square of sugar-coated heaven melting on my tongue. I’m grateful (in the most selfish way) that no other fingers are pinching at the chipped, yellowing edge of Miss B.’s best serving plate every Saturday afternoon. No, the Ladies of the White Rose, who once called on her to birth their babies and cure their ills, politely ignore the river of stories that sit ready on her every breath. They are deaf to her wise, loose chatter, peppered with lazy French and the diddle diddle dees of Acadian folk songs.

Miss Babineau’s great-grandfather Louis Faire LeBlanc was the last baby to be born before the British drove his family and the rest of the Acadians from their settlement along the dyke lands of Grand Pre. Miss B. sighs and clutches the mass of rosary beads twisted around her neck whenever she speaks of it. “The precious seeds of Acadie were scattered across the earth, the names LeBlanc, Babineau, Landry, Comeau, all planted along the bayous with bayonets, ashes and blood.” Many died on the difficult journey to Louisiana, but little Louis Faire lived. “He grew to be a strong, fine man. Blessed by the Spirit. Called of angels, he was. The sick, the weary, them that was gone out of their heads … they all come to Louis Faire. A traiteur, he was. He put his hands on their heads and their bodies—lettin’ the prayers come down, right through his mouth, healin’ them. Thank you, Mary. Thank you, Baby Jesus. Thank the Father in Heaven. Amen.”

At seventeen (the same age I am now), Miss B. was visited by Louis Faire in a dream. He spoke to her, telling her that God had chosen her to take the sacred gifts of the traiteurs back to his homeland. The dream lasted all through the night and into the next morning, her great-grandfather’s spirit whispering secret remedies and prayers of healing in her ears. When it was over, she began walking, leaving her family behind as she made her way from Louisiana to Acadie. No one is quite certain of how she ended up in Scots Bay instead of the fertile valley of her ancestors. All she will say is, “It was for Louis Faire that I came back to his homeland, but only God could make me live in Scots Bay.”

Mother says Granny Mae once told her that Miss B. had had a vision, a visit from an angel, right here in the Bay. “When Marie Babineau got to Grand Pre and saw the beautiful orchards, fields and dyke lands that had once belonged to her family, she was so overwhelmed with sadness that she ran, crying, up North Mountain and all the way to the end of Cape Split. While she sat at the edge of the cliffs, weeping, an angel appeared, comforting her, reminding her of her dream and of the gifts Louis Faire had given her before her journey. The angel explained that, in fact, she was the spirit of St. Brigit, the woman who had served as midwife to the Virgin Mary at the birth of Christ, and that she had been sent to bless Marie and ask her if she would dedicate her hands to bringing forth the children of this place. Grateful for the angel’s tender care, Marie vowed to do what God had asked of her.” You can’t say no to something like that.

Aunt Fran says it’s more likely that she took up with a sailor, and when he got tired of her talking, he dropped her here on his way home to his wife. It doesn’t matter. I’d guess she’s so old now that nobody cares about the whens, whys or hows of it, as long as she’s got “the gift” whenever they need it.

Miss B. never asks for payment from those who come to her. She says a true traiteur never does. Grandmothers who still believe in her ways and thankful new mothers leave coffee tins, heavy with coins that have been collected after Sunday service. In season, families bring baskets of potatoes, carrots, cabbage and anything else she might need to get by. They hide them in the milk box by the side door, with folded notes of blessings and thanks, but never stay for tea.

It was starting to get dark by the time we settled in for beignets and conversation. Not long after, I heard an odd stuttering sound from the road. I looked out the window and could just make out that there was an automobile coming towards the cabin, the evening sun glowing gold on its windshield. No one in the Bay owns even a work truck, let alone a shiny new car like that. Most men call them “red devils,” believing that just the sound of one is a sure sign that their horses will bolt and their cows will dry up for the day. No one comes out here from away unless they’re lost or looking for someone. No one comes down the old logging road unless they need to see Miss B. There’s one road in and one road out … and it’s the same one.

Miss B. took her teacup from the table, dumped what was left into a pot on the stove and stared into it, shaking her head. “Get up to the loft and hide behind the apple baskets. I think there’s some quilts you can pull over your head. Don’t you let out a peep.” The sound of the car was outside the cabin now, slowing and then sputtering to a stop in the dooryard. I started to question Miss B., wondering why she was acting so alarmed. She frowned. “Trouble’s come, I’m sure of it. I seen it in my leaves just yesterday and didn’t believe it, but now it’s here in this cup too. A bat in the tea, two days in a row … says someone’s out for me. I’d better take care in what I say and do. Shame on me for not trusting my tea. Go on now, get up there, before it comes for you too.” To please her, I climbed the old apple ladder that was fixed to the wall, pushed at the square lid that covered the small opening to the loft and crawled up into the space above the kitchen. Hiding under a worn wool blanket, I lay flat on my belly, peering through the loose boards into the kitchen below. Miss B. was squinting, looking in my direction. I whispered down to her, “I’m safe.” She smiled and nodded, then put her finger to her lips and turned to answer the knock at the door.

A tall, serious-looking man stood in the doorway. He introduced himself as, “Dr. Gilbert Thomas.” Miss B. invited him in, took his long overcoat and hat, and wouldn’t let him speak again until he was settled at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee. She patted his shoulder and then smoothed the slight wrinkle she’d made in his dark suit coat. “Well, ain’t you tied up proper, like every day was Sunday?” Taken by her kindness, his voice halted and stuttered each time he tried to say shouldn’t and don’t, as if the words were too painful to get out. He sat cockeyed to the table, his knees too high to tuck under it, his fine, long fingers shyly wringing the pair of driving gloves that were sitting in his lap. Except for the hints of grey in his hair that shone silver when he turned his head, Dr. Gilbert Thomas looked as if someone had kept him clean and quiet and neatly placed in the corner of a parlour since the day he was born.

In a slow, steady tone, the doctor began what sounded like a well-rehearsed speech. “As a practitioner of obstetrics, I am bound by an oath to my profession to come to the aid of child-bearing women whenever possible.” He winced back a sip of Miss B.’s strong coffee and continued. “You, as well as other generous women in communities throughout Kings County and across the Dominion have had to serve in place of science for too long.”

Miss B. smiled and pushed the sugar bowl and creamer in front of him. “A little sugar there, dear?”

“Thank you.” He spooned in the sugar and doused the coffee with a large splash of cream. “Imagine the benefits that modern medicine can offer women who are in a compromised condition … a sterile environment, surgical procedures, timely intervention and pain-free births. The suffering that women have endured in childbirth can be a thing of the past—”

Miss B. interrupted him, catching his eyes with her gaze. “What you sellin’?”

Dr. Thomas’s stutter returned. “I, I … I’m just trying to tell you, inform you of—”

“No. You ain’t tellin’, you sellin’ … if you gonna come here, drummin’ up my door like you got pots in your pants, then you best get to it and we’ll be done with it.”

She waved her hand in the air as if to shoo him away. “Oh, and by the way, whatever it is, I ain’t buyin’. I figure if I tell you that right now, you’ll either pack up and leave or tell me the truth.”

Dr. Thomas continued. “The truth is, Miss Babineau, I need your help.”

She settled back in her chair. “Now we’re gettin’ somewheres. Go on.”

“We’re building a maternity home down the mountain, in Canning.”

Miss B. interrupted him. “One of those butcher shops they calls a hospital?”

Dr. Thomas answered. “A place where women can come and have their babies in a clean, sterile environment, with the finest obstetrical care.”

She scowled at him. “Who’s this ‘we’?”

“Myself and the Farmer’s Assurance Company of Kings County.”

“How much the mamas got to pay you?”

He shook his head and smiled. “Nothing.”

Miss B. snorted. “You’re a liar.”

“I won’t charge them a thing. I won’t have to, we—”

“You got a wife?”

“Yes.”

“And she’s a good girl, a lady who deserves the finer things?”

“Well, of course. But I don’t see—”

“How you expect to keep her if you don’t make no money?”

He laughed. “I get paid by the assurance company.” He lowered his voice and smiled. “And you could get paid too … if you participate in the program. They’ll give you five dollars for every woman you send to the maternity home.”

Miss B. got up from the table. “What I gots, I give, and the Lord, He takes care of the rest. There’s no talk of money in my house, Dr. Thomas.” She held his coat and hat out to him. “I gots all I need.”

Dr. Thomas took his belongings from her, but motioned towards the table. “Please, I didn’t mean to offend you. Let me at least have my say and then I’ll go.”

She poured the doctor another cup of coffee and sat back down at the table. “You got ‘til your coffee’s gone or it turns cold.”

Dr. Thomas quickly made his case. “Many families in Kings County, Scots Bay included, already own policies with Farmer’s Assurance. A small fee, paid each month, gives these families the security of knowing that if something happened to the man of the house, he could get the medical attention he needed and they could still go on.” He spooned more sugar into his cup. “As you well know, the mother is just as important as the father; she’s the heart of the home, she’s what keeps everything moving.”

Miss B. nodded. “I always say, if the mama ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy.”

Dr. Thomas grinned. “Exactly! For the price of what most households spend on coffee or tea each month, a husband can buy a Mother’s Share from Farmer’s Assurance. This guarantees his wife the happiness of a clean, safe birth and the comfort of having her babies at a Farmer’s Assurance Maternity Home. The family can rest well knowing that ‘Mother’ will be well cared for during her confinement.”

Miss B. stared at him. “What if a mama wants to have her baby at home?”

Dr. Thomas looked confused. “Why would she want to do that when there’s a beautiful new facility waiting for her?” He tried again to convince Miss B. “You are a brave woman, Miss Babineau, taking on this responsibility all these years. Everyone I talk to has said how skilled you are, how blessed, but with new obstetrical techniques available, women can rely on more than faith to see them through the grave dangers of childbirth.”

Miss B. sat there, humming and knitting, looking up at him every so often as if to see how much longer he was going to stay.

Frustrated, Dr. Thomas tried to further the conversation. “Do you know Mrs. Experience Ketch?”

Miss B. took a sip of tea. “Some.”

“Her husband, Mr. Brady Ketch, came to my offices about a month ago with some disturbing news. Since you’ve had your hands on so many babies in this area, I wonder if you might be able to make some sense of what he told me.”

Miss Babineau smiled. “I’ll certainly do whatever I can.”

The doctor’s tone grew serious. “Mr. Ketch was quite distressed. He said that his wife was bedridden and too weak to stand. He was afraid she might die. I followed him to their home and found her to be in poor health. She was pale and wouldn’t speak.”

Miss B. shook her head. “Well, that’s just some awful. I hope you could help her.”

“I made her as comfortable as I could under such circumstances, but there’s one thing I still don’t understand. When I asked Mr. Ketch what had brought about his wife’s illness, he said that she had just given birth the day before, and that you and a young girl were there to attend it.” Dr. Thomas stared at Miss B. “Was there nothing you could do to keep her from falling into such poor condition?”

Miss B. completed her row of knitting and shook her head. “Did you happen to catch wind of the man’s breath?”

Sugar spilled from the doctor’s spoon before he could get it to his cup. “Pardon?”

“I’m sorry to say so, Doctor, but the only truth Mr. Brady Ketch is good for, is in tellin’ the innkeeper when he’s reached the bottom of a whiskey barrel. If his wife’s in trouble it’s ‘cause he can’t keep his hands from her one way or another. If he’s not puttin’ a bun in her oven, he’s slapping her black and blue. If I’ve ever given Experience Ketch a thing, it’s been to tell her she’s workin’ herself to death.”

“Are you telling me that you don’t know anything about her having a baby?”

Miss B. pulled on the ball of yarn in her lap. “Did you see one there?”

“No, Mr. Ketch said it was a stillbirth.”

Miss B. rolled her eyes. “Why, I’d guess we’d both know it if she’d just had a birth, as I’m sure you gave her a thorough examination.”

He drummed his fingers on the table, staring at his cup. My handkerchief was sitting near it, the one that Precious had given me for my last birthday, my initials embroidered in a ring of daisies. “Mr. Ketch said Mr. Judah Rare’s daughter might be able to shed some light on the matter.”

“Miss Rare is a proper young lady who’s kind enough to keep company with a wretched, feeble granny like myself. She’s also wise enough to know better than to find herself in Brady Ketch’s part of the wood. Nothin’ there but lies and brew. Either one you choose, you’re askin’ for trouble.”

Dr. Thomas picked up the folded square of cloth and looked it over. “Dora’s her name, isn’t it? I stopped by her house and spoke with her mother before I came to call on you. What a kind woman she is. She guessed that I might even find her daughter here, with you.”

Miss B. calmly put out her hand, reaching for the handkerchief “Left this behind last time she was here. You know how forgetful them young girls can be. Can’t tell you what they done that same mornin’, never mind yesterday, or last week. Some flighty too, never know when she’ll show her face at my door.”

Dr. Thomas frowned as he chewed on the inside of his cheek. It’s the same thing Father does when he knows something he’s planned on paper isn’t going to work with hammer and nails. “Maybe I’d better visit Mrs. Ketch again and see if she can remember anything now that she’s back on her feet.”

Miss B. gave a cheerful response. “No need for that, my dear. Brady Ketch may well forget he ever knew you and shoot you on sight. It’s best you leave the women of the Bay to me.”

The doctor mumbled under his breath. “Leave them to have their babies in fishing shacks and barns.”

Miss B. scowled. “What’s that?”

“I think you should be made aware that the Criminal Code of 1892 states: ‘Failing to obtain reasonable assistance during childbirth is a crime.’”

Miss B. ignored him and said, “I’m wonderin’. Doctor, how many babies you brought into this world?”

“During my residency in medical school, I observed at least a hundred or more births—”

“How many children you caught, right as they slipped out of their mama’s body?”

“Well, I—”

Miss B. stopped him from answering. “It don’t matter …” She pulled at the tangled mass of beads around her neck. “See these? That’s a bead for every sweet little baby.” She pulled the longest strand out from the neck of her blouse. “See this?” A tarnished silver crucifix dangled from her fingers. “As you’ve probably heard tell … this child’s mama ‘give it up’ in a manger.” She let it fall to her chest. “So’s next time you come out here, tryin’ to save the barn-babies of Scots Bay, you remember who watches over them.” She stood up from her seat. “I believe your coffee done got cold, Dr. Thomas. I’d ask you to stay for supper, but I know you’ll want to get back down the mountain to your dear wife. The road has more twists when it’s dark.”

Mother didn’t wait long to ask me what it was Dr. Thomas wanted. “Did he find you at Miss B.’s? He seemed nice enough. Quite the thing to come way out here. Your brothers couldn’t get over that automobile of his. What’d he want, anyway?”

“He just wanted to find out how many babies were born in the Bay last year. Part of some records they keep for the county, or something like that.”

“That’s interesting. How many babies were there?”

“When?”

“Last year. How many babies were born in the Bay last year? I can think of three, at least. There was Mrs. Fannie Bartlett, and—”

“Oh, you know, I can’t recall. I think she just laughed and said, ‘the usual.’ You know Miss B.”

Mother went back to stirring a big pot of beans on the stove, wiping her brow as she inhaled the word yes.

~ November 16, 1916

Never have I had so many things I couldn’t say out loud. At least my journal listens to the scribbling of my pen.

When Dr. Thomas left Miss B.’s, his face was all flushed, looking like he wouldn’t be happy until he’d found a way to make Miss B. say she was wrong and he was right. I told her that I couldn’t bear to see her locked up behind bars, that maybe she should consider asking the women of the Bay to seek Dr. Thomas’s care from now on, but she just smiled and strung a single bead of jet on a string and hung it around my neck. “He ain’t gonna come back. There’s nothin’ out here for him. All the money’s down in town. Them people down there come to doctors with every little ache and pain. They empty their pockets right on the examinin’ table. Why’d he want cabbages and potatoes for pay, instead? Besides, a man who can’t drink my coffee straight ain’t got nerve enough to do me harm.”

She’s probably right, but it hasn’t kept the nightmares away. It’s been the same one for the past three nights. First I’m dreaming I’m with Tom Ketch, and he’s looking down on me, gentle and sweet, like he might even kiss me. I close my eyes, but when I open them, Brady Ketch is holding me tight, his unkempt beard scratching against my cheek, his foul tongue pushing into my mouth. I try to scream and my voice won’t sound. I try to get away and my body goes limp, like I’ve got no bones, and then I’m falling, falling into the ground, into the dark, wet hole under the Mary tree. There’s moss and bones, leaves and skulls, potato bugs and worms. I can hear a baby crying. I dig through the muck until I find it. It’s Darcy, only this time he looks like the most perfect baby in the world. He’s pink and beautiful, plump and whole, his clear blue eyes staring up at me, waiting for me to take him home. When I go to reach for him, the Mary tree comes to life, her roots turning to arms as she pulls the baby up from under the moss. I call out to her, “I’ll take care of him this time, I promise.” She doesn’t speak; she just takes Darcy and starts to walk away. I cry out again, “Please, bring him back. I’ll take care of him.” I follow her, hoping that at least she’ll take him up to heaven, but she just keeps on going, walking out of the woods and down the mountain, until she’s standing at Dr. Thomas’s door.

~ November 20, 1916

Tonight we strung apples to dry and made coltsfoot cough drops. Miss B. pulled what looked to be an old recipe book from the shelf and placed it on the table in front of me. “This here’s the Willow Book.” She closed her eyes and stroked its cracked leather cover. “For every home in Acadie that was burnt to the ground, there’s a willow what stands and remembers. By the Rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. We put things here we don’t want to forget. The moon owns the Willow.” She untied the thick piece of twine that was holding its loose, yellowed pages together, thumbing through until she found what she was looking for. “Thank you, Sweet Mary. Here it is: coltsfoot. Some likes to call it the son-before-the-father ‘cause it sends up its flowers before the leaves. Just the thing for an angry throat. You write your name down in the corner of the page, Dora. So’s you remember to remember.”

From the last apple, she made a charm, grinning and singing as she pared the peel away to form a long curling ribbon of red. “The snake told Eve to give Adam her apple, oooh, Dora, who gonna get yours?” She threw the peel over my left shoulder and then stooped on her hands and knees to study it. She crossed her chest, then drew a cross in the air. “Look at that … I sees a pretty little house, a fat silk purse and the strength of a hunter’s bow.”

I bent down to join her. “What does it mean?”

“Nothin’—not right now, anyways.” She patted my hand as I helped her to her feet. “You’ll knows it when it do.”

I’d beg her to tell me more, but there’s no use in bothering Miss B. with questions. She’s said all she wanted to say. I suppose Tom Ketch is a hunter; he’s got to have a bow, living in Deer Glen and all … but there’s no pretty little house and not enough money to fill a thimble, let alone a silk purse. Miss B.’s never wrong about these things. She can tell a woman that she’s with child before the woman knows it herself. She can tell if it’s a boy or a girl, and the week the baby will arrive, most times getting it right down to the day. She can touch a person’s forehead, or hold their hand, and tell them what’s making them sick. So, even though she never said who, or even when, I can’t stop guessing at her clues and thinking over each word.

4 (#ulink_a949bd01-a313-5920-86bb-b501d544d8ea)

THINKING IS SOMETHING that Father says I do entirely too much of: “You think on things too long, especially for a woman.” At first I thought it was just something that fathers tell their daughters, but he’s not alone in this; Aunt Fran never seems to tire of carrying her journals of medical findings to the house and reading aloud from them during tea with Mother and me. Her latest is The Science of a New Life by Dr. John Cowan, M.D. “It’s right here, Charlotte, see? Oh, never mind your trying to read it just now, I want Dora to hear it too. I’ll just read this bit out loud. It won’t take but a minute. Let’s see … here it is … the esteemed Dr. Cowan states, ‘Closely allied to food and dress, in woman, as a producer of evil thoughts, is idleness and novel-reading. It is almost impossible for a woman to read the current “love-and-murder” literature of the day and have pure thoughts, and when the reading of such literature is associated with idleness—as it almost invariably is—a woman’s thoughts and feelings cannot be other than impure and sensual.’ There now, Charlotte. There it is in black and white. Overthinking and novel-reading causes, at the very least, fretting, nightmares and a bad complexion.”

This past autumn she was convinced that my bout with a cold and cough was brought on by my constant attention to Wuthering Heights. She even scolded Mother for letting me read it. “Lottie, whenever I see that daughter of yours, she always has a book under her nose! It would be one thing if she was studying psalms or even a verse or two of poetry … no wonder her health’s been compromised by the slightest change in the weather.”

Mother laughed. “Oh, Fran, with all your talk, you’d think Dora’s caught her death just by reading about the God-forsaken moors of Yorkshire.”

She turned to me and asked, “This is the one about the moors, isn’t it, Dorrie?”

“Yes, Mother.”

“And then there’s the one about that poor woman whose husband kept her locked in the attic … I always get them confused. Of course, I’ve got no time to read them myself, I’m so slow at it and all, but Dora’s kind enough to tell me about them from time to time. Don’t you worry about her, she’ll be back to feeling right in no time at all.”

Aunt Fran lowered her voice. “Her cold is just the start of a greater sickness. These ‘stories,’ as you call them, will only lead her to more pain.”

“Fran, talk plain, will you?”

“I’m talking about derangement.”

“Don’t be silly!”

She whispered. “And deviant behaviours.”

Aunt Fran decided it was best to give Mother her copy of The Science of a New Life. “Normally, I wouldn’t lend this out. But I’ll make an exception in Dora’s case. You can’t put this sort of thing off and expect it to cure itself.” She patted Mother’s hand. “I’ve marked several pages for you. The ones that apply to her condition.”

Mother smiled and nodded. She no sooner put it on the dresser next to her bed than Father was ordering me to “Gather up those books of yours, Dora. Bring them out to the brush pile.” I acted as if I didn’t hear him and walked out to the pen to feed the sow. Before long I could hear the crackle of the fire, smell the smoke from dried twigs, Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice and all the rest. I leaned against the fence and cried. There’s no point in arguing with him. There never is. I’ll say one thing for the boys: at least they don’t cry. I’ll never understand you, Dora.

Last night was the first night of bunking down. When I was little, I looked forward to cold December winds and the first snow, to Father closing off the upstairs and all of us children dragging our pillows, blankets and feather mattresses down to the front room. Each night we lay piled together, Mother kissing our cheeks in the order of our births—Albert, Borden, Charlie, Dora, Ezekiel, Forest and Gord—cozy and snug until the grass turned green in the spring. Although our winter sleeping arrangement has become crowded and a bit smelly in the last few years, I still love listening to Borden’s late-night storytelling: the time old Bobby One Eye paddled the riptides off Cape Split, how he and Hart Bigelow came to invent pig bladder baseball, the tale of the hidden treasure that’s never been found on Isle Haute, and the ghost of Old Cove Fisher’s lost foot.

This year, Father didn’t seem to know what to do with me. I heard him arguing with Mother over it after breakfast.

“Maybe she could stay at Fran’s for the winter.”

Mother sounded upset. “Why would we send her away? Surely there’s enough room for sleeping.”

Father lowered his voice. “She needs to act like a proper young lady.”

“And she doesn’t?”

“It’s just that with six boys …”

“Judah Rare, you’re being foolish.”

“She’s getting to the age where she might be considered, someone might think …”

“That she’s a sweet girl who cares for her brothers?”

“She and Charlie still hold hands whenever they walk down the road, and no matter how many times I’ve scolded her, she insists on getting in the middle of the boys when they wrestle or fight.”

“Stop worrying over her. She’s got a pure and innocent heart. I’m almost certain she’s never even been kissed.”

“That’s the trouble. No man wants a girl who’s always tied to her brothers. The longer we let this go on, the more people will think there’s something odd about it. Let’s send her to Fran’s. I’m sure your sister would be happy to—”

“Yes, I’m sure Fran would be happy to make a housemaid out of my daughter. How we raise the children is our business and no one else’s. We’ll put Dora on the end after the twins, or lay her longways down by their feet, but she’s staying home and that’s that.”

Father’s right in supposing I’ve lost my innocence, but it wasn’t by having my rose plucked in the middle of a field that hasn’t been hayed. (I can still look forward to a bit of blood on the sheets on my wedding night.) Still, a girl can lose her heart long before she gives it away. Mother’s never mentioned it, or maybe she was too busy to notice, but I remember exactly how it happened. It was the day Father showed me I was no longer a child.

Before that day, I belonged with my brothers, I was one of them. If Borden or Albert teased me, I’d tease them right back. If Charlie put mud in my shoes, he’d find a toad under his sheets that same night. For every shove one of them gave me, I’d pinch two bruises into the fleshy part of a thigh or the back of an arm. Then Father put a stop to it. On a warm, sunny day (about the same time I started to bleed and my breasts began to feel heavy when I ran), Albert, Borden, Charlie and I snuck off to Lady’s Cove after school. The tide was just going out, the rocks were filled with pools of warm seawater, and a long strip of clay lay glistening at the edge of the shore. In the shelter of the cove, we did as we always had done: we stripped off our clothes and began throwing wet, heavy balls of mud and clay at each other. We must have been quite a sight, laughing and screaming, our bodies streaked with sloppy trails of brown and grey, but my name was the only name Father called out when he found us. It was a slow, angry insisting, Dora Marie Rare. I pulled my clothes over my dirty, crusty skin and he pulled me by my arm all the way home. I shouldn’t have argued with him, but it didn’t seem fair that I should be singled out. After all, it was Borden’s idea to go to the cove, it was Albert’s idea to wade in the water, it was Charlie who threw the first mud ball. Father didn’t care. He turned, took both my arms and shook me as he spoke. “I never want to see you behaving like that again.”

“But, Father, I—”

“Don’t make me cut an alder and take it to your skin, Dora.”

When we got to the house, Mother greeted us on the porch, looking concerned. She must have spotted us coming up the road and seen from Father’s stride that he was angry. He ordered me to pump a bucket of water from the well. “Get yourself cleaned up before supper, and I’d better not find a speck of clay behind your ears.” When I came back into the house, I heard him complaining to Mother. “She’s too old to fall in with the boys, and she’s gotten some smart with her mouth too. Talk to her, Lottie, tell her she’ll never get a husband if she keeps it up. No man around here wants a wife who talks back.”

He acted as if it made him sick just to look at me. He shook me so hard he put his fears right into my body. He let go of every nasty thought, every father’s nightmare, and put them in my head—the desire to watch animals mate in the spring, the thoughts of wanting to be touched, the need for men to notice me. I couldn’t have stayed innocent, even if I’d wanted to. I guess he finally realized that there’s no way to stop a girl from becoming a woman.

At least I’m not as far gone as Grace Hutner. She has a way of speaking, putting her finger to her chin and rolling her eyes while she giggles … it’s as sly as any county-fair magician or snake oil salesman. There’s always a slight dip to the front of her blouse and an impatient turn to her ankle as she sticks her leg out to the side of her desk or into the aisle of the sanctuary at church. The lightness of her hair and the blue of her eyes fool most everyone into thinking she’s perfection walking. Her one-dimpled smile pulls everyone into her path, boys, girls, men. They fall right to her side: “Do you need help carrying those books, Grace?” “Tell us about your new dress, Grace.” “A young thing like you shouldn’t walk alone.” Every churchgoing boy in the Bay, including both Albert and Borden, has rolled her in the hayloft. The only time I’ve ever seen the two of them come to blows was over her. She had them each believing her heart belonged to him. Even though they made peace and forgave each other when she took up with Archer Bigelow, she can still get them to argue over which one of them gets to walk her home from church. All the boys want her, and every little girl wants to be her. Grace Hutner could make a man want to go blind, just so he could better hear her lies.