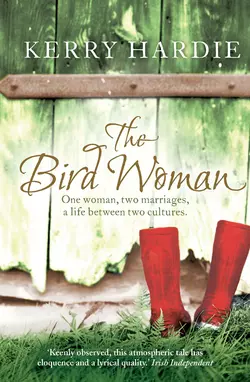

The Bird Woman

Kerry Hardie

The much anticipated second novel from prize-winning Irish poet and novelist, Kerry Hardie.'The Bird Woman' is a moving account of two marriages, a gift that feels like a curse, and the freedom that lies on the far side of family or group identity.Ellen McKinnon, red-haired, clairvoyant, fiercely independent, finds her marriage, her health, her sanity threatened when she 'sees' the death of a man in a bomb attack before it has really occurred. Terrified by what's happening to her, she leaves her home, her tribe, her husband, to live with a man she barely knows in Southern Ireland. There she strives to live a normal life in a different culture, to be accepted by her husband's family and friends, to learn a new way of living. Though determined to suppress her 'gift' at any cost, with the birth of her children the clairvoyance changes and broadens into a power to heal. Slowly the rumours spread and the sick seek her out, yet she turns them away from her door.Her husband and her closest friend demand that she question her right to suppress her remarkable powers. Reluctantly she accepts her fate, and begins her work as a healer. But the personal cost is high, and this work begins to damage her most intimate relationships. When news of the final illness of her long-estranged mother forces her return to her native city, everything falls apart for her and she finds there's no safe ground beneath her feet.

The Bird Woman

Kerry Hardie

For Sean, who walked with meevery step of the way

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u9ed23f5c-8001-5e7e-99d3-7bfae1c14c65)

Title Page (#ue818e309-4b62-5b8a-a2b0-1af7ca30f6c6)

Dedication (#u96cbc2dd-4c9e-5212-b58c-382b0a4a892d)

Epigraph (#u5bd8f4f4-2ac9-589a-a866-2cb5e33c124d)

Prologue (#u10539796-abb7-5c04-9ea3-9e168555d463)

Chapter 1 (#u63132f9a-bbab-5e3e-b188-6ffe0bd7571f)

Chapter 2 (#u519a0046-33ba-5ce2-a622-50d3b9961f47)

Chapter 3 (#u25208548-4064-5c43-a67b-f74e93362937)

Chapter 4 (#u5277bdf0-ac5d-5cde-be37-903212970287)

Chapter 5 (#ud0e3f16b-e8b5-516f-8cd1-c3d35ce50f11)

Chapter 6 (#u1807c2f6-18b8-59e9-9608-8d80dfa9550b)

Chapter 7 (#ud5b4bad9-c5ca-50dc-9dbe-cca8e6181f0c)

Chapter 8 (#u098c0e27-e174-51a4-aa83-a4e585ff36f2)

Chapter 9 (#uc92c1d6d-c0e5-5303-bea9-d18a58ff4c15)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Kerry Hardie an interview with Declan Meade (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Kerry Hardie (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Every year in Ireland about twenty thousand people go to healers looking for cures for an extraordinary range of things: burns, brucellosis, skin cancer, bleeding. And many claim to be cured.

[These healers are not] chiropractors or homeopaths or that whole section of alternative medicine: those who have developed unorthodox skills and knowledge to put at the service of the sick…They claim neither special training, knowledge, nor skills, but a gift passed from God. Or from nature. Or from inheritance. Or passed on from someone else. Ultimately they do not know whence the gift comes…

They are not faith healers either. An infant who heals can hardly be said to have faith…Faith healers rely on prayer and faith: these do not. The phenomenon of these healers is comparable to water diviners in that they use a gift that nobody can begin to understand, yet many avail of…

The more you know of these gift healers the more baffled you become. No one seems able to offer an explanation for their extraordinary abilities. The more baffling this mystery grows, the more fascinating it becomes. “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

—FROM The Gift Healers BY REBECCA MILLANE, BRANDON PRESS 1995

Prologue (#ulink_a724b025-e2a7-5ec8-b86e-5f509b86b442)

KILKENNY, FEBRUARY 2001

Sometimes life goes on at an even pace for months, years, the rhythm the same, one step following after the step before, so you get to thinking that it’s always going to be this way, and maybe part of you even longs for something to change.

Then all of a sudden it does. And when it does, it doesn’t change only the once. The first change comes, then the next, and before you know it the changes are at you so thick and fast that you’re running as hard as you can and still you’re not keeping up.

The phone call came from Derry, and everything changed. My brother, Brian, rang, only he didn’t—he got his wife, Anne, to phone for him. I listened until I’d got the gist; then I made her go and get Brian.

“I’m not being uncivil,” I told Anne. “But it’s his mother we’re talking about, not yours. Some things even Brian has to do for himself.”

I heard Anne put down the phone; then I heard footsteps and voices off, then footsteps again and the phone being lifted.

“Yes, Ellen,” Brian’s voice said down the line.

It was strange hearing Brian. If you’d asked me I’d have said I’d forgotten what his voice even sounded like, but the minute I heard it I knew every nuance and inflection—I even knew what his face looked like as he talked.

Only I didn’t. It was more than ten years since I’d laid eyes on Brian; he might be fat and bald for all I knew, he might have grey hair and reading glasses. He might have three toes missing from his right foot or no right foot at all.

But if he did, all that was in the future. For the moment I spoke to the brother who lived in my mind.

“Cancer,” I said to Liam, the word sounding strange, as though I was being needlessly melodramatic. “It seems she had a mastectomy two years ago, but she wouldn’t let them tell me. This is a secondary—something called ‘metastatic liver cancer.’ They’re talking containment, not cure.”

Liam stirred in his chair, but he didn’t speak; he waited for me to go on.

“Brian said she’s been living with them for the last two months. Anne’s off work, and the Macmillan nurse has been calling in. She took bad four nights ago, and now she’s in the hospital. They told him she might have as much as two months, but more likely it’ll be weeks…No one’s mentioned sending her home.”

We had ordered the children next door to do their homework, had banished them, unfed, and with no explanation. They were too surprised to object. Now Liam was searching my face, but I kept it blank and calm. Liam had never been to Derry, had never met any of my family; my life up there predated him and belonged entirely to me.

There was power in that and also safety: I could dispense information as I felt inclined, could tell him or withhold from him, I didn’t have to let him see what I didn’t want seen.

So I talked on, my voice as flat and dead as my face, and I knew as clear as I knew anything that keeping him shut out like this was dangerous and wrong. But I was a long way off from myself, and I couldn’t get back. I didn’t want to get back; I was too afraid of what might be there waiting for me if I did.

“How many hours’ drive to Derry?” Liam asked. “Five? Six? We’ll bring the children. When do you want us to leave?”

“I don’t.”

“Wait till she’s nearer the end? You’d be taking a bit of a chance, wouldn’t you? But if you want to be there when she dies…?”

“You’re not listening to me, Liam,” I said. “I’m not going. Not now, not next week, not next month, never. And neither are they.”

“Ellen, she’s your mother, you have to go—”

“Have to? Who says? Why do I have to?” So much for flat and dead—I could hear the hysteria rise in my voice.

“Because you’ll regret it for the rest of your life if you don’t.”

Liam’s mother had died of a stroke when Andrew was not quite two and I was heavy with Suzanna. It was a long vigil, and they were all there—her husband, children, grandchildren; her brothers and her only sister. I wasn’t. Liam had said I was better off at home; he said everyone would understand. But I hadn’t stayed away on my own account, I’d stayed away for Maura herself. I’d liked Maura; she was a big-boned, overweight countrywoman, red-faced and dowdy, with wonderful deep, warm eyes. She was devout, too—Liam was anxious when he brought me there first, for all that he swore to me he wasn’t. But she’d never said a word about my not being Catholic, or our not being married, or Andrew not being christened, not a word. Maybe she’d felt for me because I was a stranger, or maybe she’d liked me as I’d liked her. Whatever it was, she’d always taken my part.

Liam had thought it the best of deaths, but I hadn’t. I wouldn’t want to die like that myself, everyone pressing and watching, I’d want a bit of privacy and peace. So I’d cast around for something to do for her, and staying away was all I’d been able to think of.

But that was Maura. It wasn’t why I wouldn’t go North to see my own mother.

“It’s the last chance we’ll have to set things right,” he told me now. “She’ll see her grandchildren before she dies.”

I sat there, my belly full of this cold emptiness, waiting for the surge of anger that would protect me from despair. It didn’t come. Instead I felt tears rising up in me, and I pushed them down. I looked for the thing that comes through me and into my hands, but it wasn’t there; my body felt only numbness and exhaustion. I stood up and crossed to the sink, ran cold water into it, fetched potatoes from the larder, the tears running soundlessly down my face. Liam got up from his seat and tried to hold me, but I pushed him away.

“I have to make the dinner,” I said.

“Dinner can wait. Leave that, Ellen. Sit down; we have to talk.”

“Talk? What for? What’s there to say? She’s my mother, this is my business, not yours. But I can’t stop you going if that’s what you want. Do what you want—you will, anyway—but I’m not going and neither are they, and that’s flat.” I dumped the potatoes into the water and covered my face with my hands. My whole body shook with those great gulping sobs I thought I’d left behind me in some childhood drawer with the ankle socks.

Liam had the wit to sit himself down again and wait. Gradually the heaving died down, but the tears still came; they slid under my hands and ran down my wrists and soaked themselves into my sleeves. At last I wiped my eyes with the back of my hand, blew my nose in a tea towel, and turned to face him.

“I know she’s my mother, you don’t have to keep saying it,” I said. “But I don’t want to see her again. And I never want to forgive her. Never, ever, ever, Liam. That’s what I’m saying, and that’s what I mean.”

“Why?”

I stared.

He stared back, waiting.

“You know well why,” I said slowly.

“No,” he said, “you’re wrong, I don’t know. I know you don’t like her. But I don’t know what she did to you to deserve the way you feel.”

I couldn’t speak.

“What did she do to you that’s so bad, Ellen, tell me that? Not come to our wedding? I wrote to ask her—you didn’t. It was obvious you didn’t want her there.”

“She never came to see the children—”

“You’d have shut the door in her face if she had—”

I put my hands over my ears like a child.

“She made me what I am.”

That silenced him. It silenced me as well. I turned my back and started in on the potatoes, the tears running down my face again—yet again—and dripping into the muddy water. Sometimes I don’t know what I’d do without domestic tasks. The simple, ancient rhythm of them. I’d no idea I felt like this, no idea it ran this deep.

I heard the door open, but I kept my head well down, I was bent over the sink, scraping away, the tears still dripping.

“Daddy,” came Suzanna’s voice, cool as you please, from somewhere to the left of me. “Daddy, why is Mammy crying again?”

“O where hae ye been, Lord Randal, my son, O where hae ye been, my handsome young man?”

“I hae been to the wildwood; mother, make my bed soon, For I’m weary wi’ hunting, and fain wald lie down.”

I sit at the table and say it aloud. It’s a poem I learned at school—years and years ago in Derry, when I still called it Londonderry, when I still knew who I was.

It’s a ballad, very old, about a young, strong man who goes out hunting with his hounds and comes home sick and dying. His mother keeps tormenting him—where’s he been, what’s he eaten, where’s his hounds? All these questions.

“O they swell’d and they died; mother, make my bed soon…”

His true love has poisoned him, see. His hounds have died, and you know rightly that’s what’s about to happen to him too. His mother can’t save him, no one can, for he’s been to the Wildwood, a place I know well.

Liam found me in the Wildwood. He picked me up, lifted me onto his horse, carried me clean away. In the early years, whenever I was so homesick for the North that I was certain sure I couldn’t thole it down here for another minute, I’d hear the words in my head and something would change. It always worked.

And later on, whenever I was fed up with Liam, or out of sorts with my life, I’d think of the Wildwood and how he saved me from it, and I’d calm down.

Missing somewhere may not only be about wanting to be there, it may be a bone-deep need for the voices and the ways you were reared to, even when you know well how lonely they’d make you now. Lonely with that special, sharp loneliness that comes when you’ve got what you longed for and it isn’t enough anymore—it isn’t ever going to be enough again.

And that’s what’s ahead of me now. The bag’s packed, the alarm’s set, but I’m walking the night house, sleepless. And when I’m not walking I’m sitting here all alone.

All alone, and trying to frighten myself into remembering how Liam saved me, to frighten myself into being so grateful again that I’ll forgive him for what he’s done. I try, but it doesn’t work. The kitchen doesn’t work either, though I love the kitchen at night—its lit quietness, the floor washed, the work done, everything red up and put away. But the kitchen is different; everything’s different and so far away from itself it might not ever get back.

I go upstairs again, past our shut door, with Liam sleeping behind it. I want to shake him awake, but what’s the use? Liam awake won’tbring me sleep, and I’m sick of hearing my own voice saying the same things over and over.

Suzanna’s door’s next. I go in and watch her, flat on her back, her duvet pulled into a scrumpled nest all around her. You could dance a jig on Suzanna and she’d only stretch and maybe smile and wriggle back down into sleep. She’s eight years old, full up with herself, her own child. She has Liam’s soft brown curls all round her head, and it’s her will against mine.

I stand at the half-open door of Andrew’s room, but I don’t go in, for the slightest movement wakes him. Andrew is different—so different you’d nearly think him Robbie’s child and nothing to do with Liam at all. But Robbie’s child was a girl, and she slid from out of me way before her time. I held her in my hand—all the size of her—and I called her Barbara Allen, after the song. Then the ambulance came and they put me on a stretcher and one of the ambulance men took her, he said he would mind her for me, but he lied, for I never saw poor wee Barbara Allen again. That was the day I saw Jacko Brennan die in a bomb a full month before it happened. Then they put me into the hospital and they filled me up with drugs to keep the Wildwood away.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_0c9a33b9-34b3-5353-b4ee-7beb45a01efe)

SEPTEMBER 1988

The first time ever I saw Liam he was standing at the bar of Hartley’s in Belfast. I was married to Robbie then—I’d been married to Robbie for near on four years for all I was only twenty-three. I was married and that was that; I’d no more thought of going off with anyone else than of dandering down to the travel agents and booking myself a nice wee holiday on the moon.

I was to meet Robbie around eight, along with a bunch of his drinking friends that he’d known from way back. I walked in, and the minute I saw Robbie I knew from the cut of him that he hadn’t just strolled through the door. Stan and Rita were there, they were sitting at a table along with a couple more of our crowd, plus a black-haired girl with a widow’s peak who I’d never laid eyes on before. She was wearing jeans and a sweater, and she hadn’t a scrap of makeup on her, though it was Friday night and there wasn’t another woman in the place without heels and lipstick and mascara. She wasn’t talking to anyone, and no one was talking to her.

Robbie was up at the bar buying a round, and he called me over.

“Mike phoned,” he told me. “Christine started early. He’s away up to the hospital to hold her hand—”

“I thought she wasn’t due for another month?”

“So did she. But she got ahead of herself, and nothing would do her but she had to have Mike. I told them a bit of a story at work, and they’re not expecting me back till sometime next week. I’m covering for Mike while he’s otherwise occupied, I’ve been round at the gallery all afternoon.

“This is Liam,” he added. I looked up at this tall, thickset man with brown curly hair and grey eyes. “He’s from Dublin, so he is. He’s up here about a show in the Arts Council Gallery.”

Robbie was an electrician with a firm on the Lisburn Road, but he did nixers on the side whenever they came his way. His mate Mike did the lighting for the Arts Council Gallery, and he made sure to always ask Robbie when he needed an extra hand.

“Robbie’s been great,” Liam said. “We’ve been sorting out what we’ll need for the show—”

Robbie nodded, but he didn’t say anything. I knew right away he didn’t like this Liam. Then the drinks came and more chairs were fetched across, and when everyone finally settled down again, there I was, beside Liam.

Liam was introduced all round and so was the black-haired one in the jeans, whose name, it seemed, was Noreen. Liam told us he was a sculptor, and your woman Noreen was a potter from Cork and something called the Crafts Council of Ireland was organising a group exhibition in the North in November. They were up here in Belfast, he said, to look at the “space.”

No one was listening; none of us cared. I saw Stan look at Robbie, and his eyes closed down from inside, plus that wicked wee pulse that means he’s up to something was showing beside his mouth. After that, I knew not to bother my head with them; that look of Stan’s meant Liam and Noreen wouldn’t be with us for long.

Stan wouldn’t be one for socialising with those from the other persuasion. Especially not when they came from the South.

Liam gave me a cigarette. I was only a few weeks out of the hospital and still smoking like a chimney. He brought out a lighter and stuck it under my nose and flicked it. It didn’t light. He looked at it, surprised, then shook it and tried it again, but still it didn’t light. I remember being surprised that he was surprised by his lighter not lighting; I mean, it isn’t exactly unusual—lighters are always playing up or running out or just not working. I was watching him and thinking all this in an idle, distant sort of a way; then I glanced down at his other hand, laid flat on the table, and I got this terrible shock. It was a big hand, broad, with a thatch of brown hairs on the back and nails that weren’t that clean. I looked, and the noise of the bar dropped away and I couldn’t look anywhere else, for I knew for certain sure that I had some business with this Liam that I didn’t want.

Business? Ah, tell the truth, Ellen. You knew this “business” of yours was bed, and maybe a whole lot more.

I dropped my cigarette, and it rolled onto the floor. I bent down and started fishing around for it, the sweat springing out on my skin. I’m going crazy again, I thought, though I wasn’t seeing anything and nothing was happening that definitely shouldn’t be happening; there was only this weird knowing-something-ahead-of-its-time that always frightens me stupid.

I didn’t want to come up, I’d have stayed right there, safe among the chair legs, but Robbie was watching me like a hawk since the hospital, so I didn’t dare.

I found the cigarette, wet through in a puddle of beer, then I unbent myself and lifted my head up over the edge of the table. My eyes met Robbie’s.

For fuck’s sake, woman, Robbie’s eyes said, for fuck’s sake get ahold of yourself—

Implacable, his eyes. No softness, nowhere to hide. So I knocked back the vodka, straightened my backbone, and turned to this Liam and talked.

I drank a lot that night, and I wasn’t the only one.

I was waiting for Stan—it was always Stan who made the moves—but he didn’t; he let them sit on.

He’d glance across at Liam, who was labouring away, trying to get the conversation up and running; then he’d sneak a wee look at Noreen, but she’d given up and was staring into her glass.

Sound move. She wanted to go—any fool could tell you that—but she couldn’t catch Liam’s eye, he was way too busy with me.

I began to wonder what game Stan was playing. Stan could be cruel—a cat-and-mouse streak a mile wide. Was he waiting for Robbie to catch on that someone was trying too hard with his wife?

The paranoia was fairly setting in when Stan starts reminding Robbie we’re meeting up with Suds Drennan and Josie at ten. Then he turns round to Liam, his face dead serious, and he tells him he’s sorry but the place we’ve fixed to meet Suds and Josie in wouldn’t be anything like the bar we’re in now.

Liam nods and smiles warily. He knows he’s being told something; he just hasn’t figured out what.

Stan says what he means is the bar we’re going to wouldn’t be that mixed.

They’re all attention, even Noreen. This is Belfast after all, this is what they’re here for. Stan says “hard line,” he mentions their accents, he mentions the fact that Liam’s called Liam, which is a Catholic name…He lets his voice trail off regretfully. They understand.

Northerners love frightening Southerners—telling them what not to say, where not to go, where not to leave their Southern-registered cars—seeing their eyes grow large and round. The Southerners love it too, you can nearly hear them telling themselves what they’ll tell their friends when they go back home down South.

Everyone loves it: the drama, the bomb blasts, the kick of danger in the air. So who’s suffering, tell me that? No one at all, till some unreasonable woman starts into grieving over the daughter blown to bits, the son sitting rotting in jail, the husband shot through the head, his body thrown down an entry or dumped on waste ground.

Some woman, or maybe some man. For men grieve too, and even your hardest hard-man is not as hard as he likes to let on when it comes to next of kin. And children are soft; children cry easily and long.

It’s a sorry business alright, we humans are a sorry business, the way it’s all mixed up inside us, the ghoulish bits that come alive watching the horror, the soft, gentle bits that will go thinking the sky’s fallen in when we find out that someone’s not coming home to us ever, ever again.

Where was I? In Hartley’s, 1988.

So we left them sitting there, the two of them, and went dandering off up the road to the Lancaster, which is a mixed bar, safe as houses, where you’ll get served till two in the morning, no bother at all. And I was drunk, and frightened even through the drink. I thought if I could only get clear of Liam that awful feeling that he was my fate would vanish away.

At the Lancaster we fell in with the crowd we still knocked around with from student days, so we sat down and set about getting much drunker. And somewhere along the way Robbie began collecting money. He was organising a carry-out to drink back in the flat.

It had got so late it had turned into early. There was no drink left, half the crowd had gone home, and the rest were mostly passed out in their seats or they’d slithered down onto the floor. Suds was still hanging in there, but wee Peter Caulfield was out for the count and so was Suds’s girlfriend, Josie.

Time for bed. Robbie made it up onto his feet, shook Stan awake, pulled out the spare blankets, and dumped them onto the floor. Stan was all for bedding down there and then, but Rita was soberer—she found their coats and somehow got him downstairs. Then she heaved his arm over her shoulders and staggered him off up the road.

Suds had given up; he was curled on the floor like a baby, and there was no way Josie was about to wake him up and take him home. I shook out a blanket and covered her up, then I threw another one over the foetal Suds. He stirred, tucked the edge of it in under his chin, smiled, and snuggled down deeper into the manky old carpet without once opening his eyes.

I thought I’d start lifting the glasses and bottles out into the kitchen, but I couldn’t seem to aim my hand straight, so I sat and smoked a cigarette instead. I could drink for ages without passing out or vomiting in those days. I thought I was great and Robbie was proud of me; I never once stopped to ask myself did I like it or what was the point or was it worth the crucifying awfulness of the hangover the next day.

I was desperate for bed, but I held off joining Robbie; I wanted to be certain sure that he wouldn’t wake up. I didn’t like sex with Robbie when he was really drunk, I could have been anyone or no one for all he cared, he was clumsy and rough and only thought of himself.

I’d have bedded down with the rest on the floor, but I knew there’d be no holding Robbie if he woke in the morning and I wasn’t there alongside him where I belonged. He’d accuse me of doing I-don’t-know-what with I-don’t-know-who—then he’d take me by the shoulders and shake the teeth near out of my head while the rest of them scuttled off-side as fast as they could like so many crabs with the runs. And it was all in his head. There wasn’t a sinner who wasn’t way too afraid of him to look sideways at me, much less try to get a leg over Robbie’s wife.

But if I hated Robbie in bed when he’d drunk too much, I hated him worse when we were out together and the drink took him in that twisted way it sometimes did. There were times he got so jealous I couldn’t even take a light off someone. I’d be grabbed by the wrist, pulled from a room, pushed into a corner of some landing or hallway, and fucked against the wall. That was Robbie with the drink on him: not caring how I felt, not caring if anyone saw, not caring about anything except himself and whatever it was that was eating him alive.

I’ve seen me walk home holding my skirt closed to keep it up, torn knickers stuffed into my pocket, dead tear trails running down my face.

And in the morning he’d be all over me: how sorry he was, how he knew I didn’t look at other men, how it was only the drink—

If he remembered at all, that is.

And I learned fast; I’d forgive him fast—at the start because I was shocked and ashamed, later because I knew if I didn’t he’d stop being sorry and start into listing the things he’d seen me do with his own two eyes. What I’d said to this one, how I’d flirted with that one—

It was a funny time, I can see that now, and I know what Liam means when he says he can’t understand why I stood for it. But it wasn’t like that—it wasn’t a question of standing for things.

I was young, I didn’t know much, I thought if he was that jealous it meant he was dying about me.

And I was dying about him—I really was—he was that good-looking and streetwise and together. Sometimes I’d be waiting for him and I’d see him coming up the street before he’d spotted me. Then I’d stand there, watching him, and I couldn’t believe my luck.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_daebba94-b7a6-51ad-a459-b5fc3fcf72ef)

When I met Robbie I was a good girl trying hard to be a bad one. I was at Queens, studying Russian and living in a flat with four girls from Lurgan who were all doing geography and knew each other from school. I’d got talking to one of them in the coffee bar at the end of the first week: they’d rented this flat, she said, and there was a room going spare if I didn’t mind it being a wee bit poky.

“How poky’s a wee bit poky?” I asked.

“There’s space for a single bed. And a window as well, but it’s too high up to see out.”

I said yes right away. It was cheap, and already I hated my landlady. Besides, if there’d been enough room they’d have stuck in another bed and I’d have had to share. But they didn’t really want me, nor I them. They were into country and western and the Scripture Union and cocoa in their pyjamas and studying hard. I wasn’t, but I might as well have been. I was stuck with them, knowing there was more to this student-thing than I was getting, not knowing how I was going to lay hands on it. Until I met Robbie, that is, and everything changed.

It was in the canteen of the Students Union. I mostly didn’t go there because it was cheaper to eat at the flat, but I was going to see a Russian film at the University Film Theatre and there wasn’t time to go back before it began. There I was, a plateful of food on a tray in one hand, cutlery from the plastic bins in the other, when Robbie knocked into my elbow and near sent the whole lot flying.

“Sorry,” he said.

“That’s alright,” I said, though my fried egg had a wet, orange look to it and the chips and sausages were afloat in spilled Fanta. Then he was trying to give me his plate and I was refusing and he was insisting, and the end of it was we were sitting at the same table sharing his chips and his fry and I never did get to The Battleship Potemkin and the girl I was supposed to see it with never spoke to me again.

After that I was Robbie’s girl.

I thought it had all been a providential accident, but a week hadn’t passed before he was telling me he’d had me picked out, he was only waiting his chance.

“What d’you mean by that?” I asked him.

“I fancied you, stupid,” he said, sliding his hand between my thighs. But I wasn’t having that, or not right away, so I made him spell it out.

He’d fancied me, he said. He’d seen me around, but somehow I always vanished before he got near enough to speak. Then there I was, right under his nose, so he’d knocked into me, just to get talking like, and look how we’d ended up.

Robbie wasn’t a student, but he lived two streets up and he shared a flat with students. He used the university canteen because it was a good place to pick up girls. He looked at me hard when he said the last bit, but I wasn’t going to rise to that one; I knew it was sort of a test to see would I make a fuss.

I didn’t rise, but I did take my courage in both hands and I asked him why he fancied me. I wasn’t fishing for lies or for compliments either—I badly needed to know.

He said it was my hair, but he wouldn’t say anything more. Later, when we’d been to bed a few dozen times in about two days, he said he’d been right, so he had, I looked so repressed, a volcano waiting to blow.

I didn’t say anything. Part of me was offended, and part of me was the opposite. Repressed at least held potential. And I sort of liked the volcano bit. But maybe he’d meant frustrated?

A couple of weeks later I moved into Robbie’s flat. His flatmates smoked dope and drank way too much and never went near the Scripture Union. I was shy with them, but I liked them as well, and soon I knew loads of the wrong sort of people and felt I was halfway alive.

Just the same, it wasn’t that long before we started looking around for a place of our own. It was Robbie’s idea, but I was into it too. We wanted to be by ourselves.

We found a place and moved in, and Robbie began to talk about getting married. I’d say I was nearly flattered to begin with, but then it dawned on me that he meant it and I panicked.

I couldn’t, I told him, I hadn’t even finished first year. Besides, I was way too young, and everyone would think I was pregnant.

He gave me a funny look.

It was a shock that look, I can tell you.

“Hold on now,” I said to him, hardly knowing what I was saying. “Marriage is one thing—I could maybe even get used to it. But not pregnancy. Pregnancy is definitely, definitely out.”

He laughed and said he could always get a rise out of me, and when did I want to get married, what about early July? He’d take extra time, and we could go off somewhere over the Twelfth Holiday and I could start into my second year with a ring on my finger, then everyone would know who owned me.

You’d think, wouldn’t you, that I’d have had the wit to hear that, but I didn’t. I never had sense—my mother was never tired telling me that—I never had any idea of what I was doing till it was done.

Before we were married I took Robbie home to Derry for the weekend. Londonderry, I should say, for I was a proper Protestant then, a paid-up member of the tribe. It only turned into Derry after I’d moved down South.

We went to Londonderry on the bus. Separate rooms and best behaviour. Robbie’s idea. I could have told him for nothing we weren’t about to get anyone’s blessing.

My brother, Brian, took me aside about half an hour after the introductions.

“You’re not serious, are you?” He didn’t expect an answer.

I phoned my mother from Belfast for her verdict, though it was plain as the nose on her face what she’d thought. But I couldn’t ever leave her be, I always had to force her hand, to make her spell things out in black and white.

There was a small, deep silence down the phone line. Then, in that neutral, damning voice of hers, she told me he was common.

And I laughed aloud, for he was, he was all the things she had reared me against—he was working-class, sectarian; he drank too much; he neither knew nor cared what people thought.

And there was I, the teacher’s daughter.

I laughed, but she’d hurt me and she’d meant to.

Poor Robbie, he wanted me to have my family’s blessing; he was trying in his own way to do right by me.

Dream on. The only thing in his favour was that he wasn’t a Catholic, but even I couldn’t make her say that out loud, for being sectarian was part of being common.

So that was that. My father was dead, and I’d no other siblings, which meant there was no one else to object except for Robbie’s family. And they did, by Christ they did. If they said I was the wrong girl for him then that was far and away the kindest thing they said.

None of them liked me. His brother Billy said four years, five at the most—it would take that long for the bed to cool. And there’d be no children—not unless I got caught—there’d be nothing to hold us together, so we’d part.

His sister Avril said my mother’s unsayable: at least she’s a Protestant. Which shocked his sister Rita, for it had never once occurred to her that anyone belonging to her would even think of marrying out.

They said all this to Robbie behind my back, knowing full well he’d repeat every word to my face. He wouldn’t listen any more than I would. He booked the Registry Office, and he put the notice in the paper; then he told them they could come if they wanted or stay away, it was all the same to him.

We didn’t even ask my family.

In the end they all came, but Billy was right, it was four years and only half a child, and yes, he was right again, I was taking no chances, I hadn’t been on the Pill that first night with Robbie, but I was round at the family planning clinic first thing the next morning.

The baby—what there was of her—was only because I got drunk and slipped up.

You’ll think me hard, but I wasn’t hard, only very young. And you weren’t reared there, you don’t know what it is to grow up in a place where everything seems normal enough on the surface but underneath it’s all distorted and wrong. And the worst part is that you don’t even know it’s distorted because for you it is normal, and if you don’t leave it behind and live somewhere truly normal, you’ll never find out.

I suppose the Catholics were right when they called it a war, though our lot denied it. It was a war, but it wasn’t like a normal war; there weren’t any uniforms or fronts or advancing-and-retreating armies, and when the peace finally came there wasn’t any going back home to your own place and learning how to forget. A civil war.

A few years back, Liam showed me a catalogue someone had sent him, the work of a German painter called Otto Dix. These were portraits Dix had done in Germany between the two World Wars, Liam said, when Germany was all busted up and the streets were full of profiteers and prostitutes and starving young soldiers minus their arms or legs.

But it wasn’t despair that Otto Dix had painted; it was people who’d made money fast and were getting through the pain of the world by living as hard as they could. Black-marketeers, pimps, club owners, satirists. The paintings were normal, but at the same time they were distorted, they fairly glittered with rage and hope-lessness, they hurt you as you looked. I glanced through the first few pages then shut the catalogue fast and put a big pile of ironed clothes down on top of it to cover it up. I wanted to be by myself with it, to turn the pages slowly and stare at the pictures, which frightened me yet somehow brought me home.

Robbie only ever struck me the once, and that was on account of his sister Rita leaving her husband and my not being home all night.

Rita was fifteen years older than Robbie, she had more than half-reared him, so his feelings were softer for her than for Avril or any of the brothers. Rita was married to a man by the name of Larry Hughes, who had strong paramilitary connections. Larry was UDA and no picnic to live with, but he’d got himself a longish stretch for aiding and abetting on a murder charge, so it was a good while since she’d had to.

Well, Rita buckled down, she went out to work, reared the two young ones, never looked at another man nor missed out on a prison visit. Not for Larry’s sake, mind, but to keep Larry’s comrades in the Organisation off her back—or that’s what she told Robbie. And she told him she’d be gone the minute Larry was out, but he never really believed her. He thought it was only talk.

Larry did five years then got early release, and home he came. The key was in the lock, the fridge was stuffed with food, the whole place was spotless. But when Larry lifted his voice and yelled for Rita he knew from the feel of the silence that the house was empty.

He went mad. He went straight to the mother—no joy—then he went and got Robbie out of his work, for if anyone knew where she’d gone it would be Robbie.

But Robbie didn’t know. He told Larry over and over till Larry had no choice but to believe him.

Larry started coming on heavy. He wanted her found or he’d know where to lay the blame, he told Robbie. Robbie was soft for his sister, he said, and every bit as bad as she was. He wasn’t rational. Robbie was sorry for Rita, but in his book she shouldn’t have left no matter what, so he let himself be worked on and shamed by Larry, and the end of it was that Robbie said he would find her, and off he went with Larry to leave no stone unturned.

They asked everyone, they looked everywhere, they even sent Avril to the women’s refuge to check if she was there. But Rita wasn’t in Belfast at all; she was on the boat with the kids and heading for London, where the cousin of an aunt-by-marriage had promised to make room for them till they got a start. The mother knew alright, but she wasn’t saying. If Larry found Rita, the mood he was in, Rita wouldn’t be walking for months.

So, no joy all over again, and off they went to a bar to make a few further enquiries. Larry started running Rita down. He said she was a fat, idle, good-for-nothing bitch, a toe rag, not fit to lick the corns on his feet, and a whole lot more besides. Robbie took it for a bit then he said that was his sister Larry was slagging off, but Larry didn’t care whose sister she was, he got worse and worse, till the filth fairly rolled off his tongue. So Robbie hit him—which took some courage—and soon they were rolling around on the floor among the chair legs, half the bar either joining in or trying to pull them apart.

Robbie made it home in the early hours. He was battered and bruised, his tail between his legs; he was looking for comfort, but I wasn’t there.

No way was I there, I wasn’t stupid. I was afraid of Larry, and there was a girl I was friendly with just round the corner who owned a passable sofa. I left no note, in case they came looking.

The next day I took my time. I went to a lecture then sat on in the coffee bar, and when I got home I let myself in very quietly and stood in the hallway, listening. Silence. The flat was empty, Robbie away back out to work. But he wasn’t away back out to work. He was there, in the kitchen, waiting.

“Where were you?” he asked, but I didn’t answer. He lifted his hand, and the black eye he gave me took weeks to lose its colour.

That was back in the early days, we weren’t long married, and I suppose I bought into the hard-man myth along with near everyone else in Belfast at that time. And he was sorry, really sorry—he promised he’d never do it again, and he didn’t.

But not doing it again was killing him—even I could see that—it was the reason he shook me till my teeth rattled; it was why he couldn’t let me be when we were out together.

And he was a nice lad when he let himself off the hook. That’s all he was, just a lad who thought he had to be a hard-man, take no shit, drink till he couldn’t stand up, and look out for his own. He was bright too—every bit as clever as I was. He’d grown up on the streets, education was crap, but a part of him hungered after it. That’s why he hung round with students—it wasn’t only to pick up girls, the way he let on. And he wasn’t a hard-man either, he was a soft man with a hard-man’s training. His own man as well, for he’d feinted and ducked and somehow stayed clear of the paramilitaries. Not so many—reared as he was—managed that at all.

So that was Robbie, poor Robbie that never did anything on me but what he’d been programmed to do: find a girl, stick a ring on her finger, get some kids on her, feed them and clothe them, and keep the whole show on the road whatever the cost. Well, we’ll leave Robbie out of this now, I’ve nothing to hold against him—not the torn knickers, nor Barbara Allen, nor the hospital for the mind that came after the hospital that saw the last of Barbara Allen. He couldn’t help himself. He was near as much a victim of himself as I was.

And those were strange times, and people found strange ways of coping. Sometimes down here I remember those times and hardly believe myself that some of the things that happened happened at all. And I couldn’t ever talk about them to folk here. They’d think I was mad or I’d made them up.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_fc4f0f40-2306-5144-acf3-03ef3ef42ec0)

Icried a lot after Jacko died, so the doctor put me on antidepressants. He said they might do the trick.

I took the tablets and felt even worse, so I cried all the time, and the more I cried the more I couldn’t stop. Robbie kicked up, so I kept going back, but nothing the doctor did seemed to make any difference.

Robbie said he’d come with me the next time, and I was glad. He talked to the doctor, the doctor talked back, then the doctor sighed and said that a week or two in Purdysburn might be worth a try. Robbie looked at me, I nodded my head, and the doctor filled in the forms.

What you can’t see doesn’t exist. If you start into seeing things that aren’t there at all you have to be schizophrenic or mad. Purdysburn is Belfast’s mental hospital, so my going there made sense to me as well as to Robbie. And it wasn’t so bad, once I was used to it. Plus it was such a relief not to have to try to be normal that the crying stopped a few hours in, and I hardly noticed.

The dining room frightened the wits out of me that first night. All those mad people, eyes down, eating away; I was terrified someone would take it into their heads to speak to me.

Then when no one did I started wishing they would.

“D’you not want that?” It was the fella sitting across from me, leaning forward, staring at the potato bread I’d been pushing around my plate. I didn’t answer.

“Give it to Annie,” he said. “Annie’s mad for potato bread.” He still hadn’t looked at me, but I was looking at him and what I saw was a pasty-faced lad hardly older than I was, with hoody owl eyes that looked out from behind those round National Health glasses, the same as John Lennon wore.

“You’re a picky eater,” he said to what was left of my Ulster fry. He had little slim wrists and brown tufty hair that stuck out round his head as though he’d just woken up.

“I’ve a tapeworm,” I told him. “That’s why I’m thin.”

“You have not. If you had one of them you’d have cleared the plate.”

“It’s asleep,” I said. “On account of the medication.” He lifted his eyes slowly and looked at me and didn’t look away. His eyes were light blue, and the lids were large and his gaze seemed to come from a long way off.

“Which one’s Annie?” I asked, just for something to say.

“The auld doll at the end of the next table.”

His name was Michael. After that, I always sat beside him in the dining room. He was the first person I’d spoken to, and that gave him stability in my uncertain world. That, and the impermeable distance in his half-closed eyes. He was in because he’d tried to drown himself. He didn’t tell me this right away, he waited till he was used to me, then he sprang it on me one afternoon, the two of us sitting in the dayroom, smoking.

“It takes all sorts,” I said when I’d heard his news. “The Lagan’s a dirty old river, I wouldn’t go jumping in it myself.”

“Who said anything about the Lagan?” He stared into the middle distance. “I built a raft, so I did. Pushed off from Ballyholme Bay.”

“Where’s Ballyholme Bay?”

“Bangor, County Down.”

“Rafts are so you can float, not so you can drown.”

“Fair point,” he said. “I had a bike, a Harley.”

I stared. For a moment I wondered if he was really mad.

“It’s a hard world, so it is,” he said carefully. “I couldn’t just go off and leave her now, could I?”

It took me a minute to get it. “You put the bike on the raft?”

He nodded and lit another cigarette. “I put the bike on the raft and chained my leg to the wheel. That way we’d both go down together—”

“Sounds like a cry for help to me,” I said firmly.

“Don’t be negative.”

“I’m not being negative. Oh look, there’s a man and a bike on a raft. Looks like they’re floating out to sea—Did it not cross your mind that someone might try their hand at a rescue?”

“It was four o’clock in the morning. I’d have been home and dry—or more to the point, wet—but for this wee lad running away from home.” He was staring at me as he spoke, with that blank owl gaze that told nothing. “He takes one look, sets down his red plastic suitcase, and scuttles off to raise the alarm—”

“You could have jumped in right away,” I said stubbornly. “You didn’t have to wait around.”

“I got the tides wrong. It wasn’t deep enough to drown.”

He was serious. I wanted to laugh, but I stopped myself. Either the story was true or it wasn’t. Either way, he was mad. I wasn’t prepared for his question.

“And you?” he asked.

“Me?”

“There’s no one else in the room, is there?”

“I had a miscarriage,” I said. “Then something else happened. And after it happened I couldn’t stop crying.”

A raised eyebrow and that look again.

“It’s true,” I said. (Why was I sounding defensive?)

“There’s more.”

“No, there isn’t.”

“Yes, there is.”

“I see things that don’t happen. Sometimes they happen, but not always. And not till a good while after.”

Then I told about walking down the street and seeing the bomb going sailing over the security fence and onto the roof of the bar. How I was somehow inside the bar at the same time as being outside, watching. And then about seeing Jacko Brennan being blown to smithereens.

“And I’m screaming and screaming,” I said. “And people are coming running and they’re taking me to the hospital and I’m losing Barbara Allen, which is what I call the baby.” I could hear my voice, and it was going high and shaky. He held out his cigarettes, and I took one and he lit it and I saw that my hand was shaking as well as my voice.

“Only it didn’t happen,” I said. “I mean, Jacko dying didn’t happen. Losing Barbara Allen happened alright. But six months later Jacko died, and it was all the way I saw.” He waited. I took a long drag at the cigarette and went on. “It was evening. I was ironing, and the window was open and I heard the blast and I knew exactly where it came from and I knew that Jacko was dead. But this time I didn’t see a thing. I went on ironing. But the shaking started in my hands, and it went up my arms and wouldn’t stop. I sat down and waited for Robbie. Robbie came in, and he said it was true; there’d been a bomb and Jacko was dead, but that was all hours and hours ago. Funny, wasn’t it? Jacko, dead like that? And why hadn’t I turned the light on, why was I shaking?

“That’s all he said. He never once mentioned me seeing it all six months before it ever happened. Maybe he didn’t want to think about that or maybe he saw the state I was in and he didn’t want to make things worse…But he took me over to the hospital, and they gave me sedatives. They said it was shock. The next day I started this crying-thing, and it wouldn’t stop.”

“Who’s this Jacko Brennan?”

“No one special. I only knew him to nod to, say hello—”

“That’s not mad, it’s clairvoyant.”

“There’s no such thing, stupid. People who see things are mad.”

“You’re mad if you think that. You should be in Purdysburn.”

“I am in Purdysburn, and so are you.” I glared at him. “Anyway, what’s so great about what you did? What’s so great about trying to drown yourself?”

He looked back at me, unblinking. For a moment I wanted to kill him; then I started to laugh and I couldn’t stop. I laughed, and I laughed and when I came up for air, he was looking at me still, his expression completely unchanged.

“That’s more like it,” he said.

After that I had company. Michael and me, a twosome. It was June, and the trees in the grounds were green and thick in the summer night. The dayrooms were all on the ground floor, and it wasn’t a heavy-duty part of the hospital, most of the windows weren’t locked. After dark people flitted about like moths. The staff must have known, but nothing was said. Perhaps they were sorry for us; or perhaps it kept us quiet, and they didn’t care. I’d climb with Michael through a window of the empty dining hall, and we’d walk about under the trees and lie on our backs spotting stars through the darker darkness of leaves. We told each other stories, sometimes from books, sometimes incidents that had happened in the past. It was lovely, so it was. Words spoken into the night. Small, soft words, far off and glimmery like the summer stars. Sometimes we climbed into the trees and sat in the forks of their branches, swinging our heels. I was better at climbing than he was, more agile, more sure-footed; I’d join my hands into a stirrup to give him a start then I’d scramble up behind him.

After the first week I asked Michael if he fancied having sex with me, but he turned me down.

“Sorry,” he said. “Nothing doing.”

“Why not? Are you gay?”

He gave me his sniffy look. “I don’t fancy you,” he said. “Besides, I’m married.”

“What’s that got to do with it? Anyway, I don’t believe you.”

“That I’m married? Or that I don’t fancy you?”

“Both,” I said. “I don’t think you’re married. I think you fancy me but you can’t get it up.” (It was wonderful, that hospital. All your inhibitions went sailing off down the river.)

“Correct,” he said. “On both counts. It’s the drugs. Why don’t you try Catriona?”

“Do I look like a dyke?”

“Silly girl—ugly word. Catriona’s so beautiful. Those red lipstick circles she draws on her cheeks. I’d try for her myself if I was able.”

“Is she a dyke?”

“Who knows? She might feel like giving it a go if you asked her nicely. Lots of people have a bit of both.”

“Speak for yourself,” I said. “I certainly don’t.” I was shocked. Besides, I was afraid of Catriona, though I didn’t say that to Michael. She saw blood coming out of the taps, which was worse than seeing people being blown to bits.

Michael stared at me, a long, slow, speculative look from those hooded eyes. “You’re very narrow-minded for a redhead,” he said.

I wanted to ask him what he meant, but I didn’t. I was afraid of my hair, even then.

Michael never touched me, never as much as took my hand walking back through the dark. And I was glad enough, for it kept things light and simple. My forwardness was really only bravado.

Robbie came and when he did Michael vanished from sight.

“Hubby alright?” he’d ask me afterwards. “Not pining?”

“Robbie,” I’d say. “His name’s Robbie.”

But he went on stubbornly calling him Hubby. I wouldn’t answer him when he did. I sulked, but he wouldn’t shift; it was Hubby this and Hubby that till I lost my temper.

“Lay off, would you? You’ve never even set eyes on him.”

But he had. He’d seen Robbie from a window.

“I wouldn’t want to meet him on a dark night down a back entry,” he said. “He’s the sort kicks the shite out of people like me—”

He had a point, though I didn’t say so.

Robbie hated coming to the hospital. Shame made him narrow his shoulders and kick out sparks with his steel-shod boots. His wife in that place, labelled forever, was more than he could handle. And no Barbara Allen. He’d wanted Barbara Allen as I never had, and now she was flushed down some hospital sluice, gone when she’d hardly started.

My mother came on the bus from Derry. I told her the doctor had said I could ask for a transfer to the hospital there. That way she could visit more often.

She gave me a long, straight look and told me I had a husband. Then she said Londonderry was just a wee village for talk, and folk said these things ran in families, and what about my two wee nieces? Had I no thought for Brian and Anne at all?

“Oh, folk know alright,” she added. “I don’t try to hide what can’t be hid, that’s not my way. But some things are best not advertised.”

Hard words, but there was a tenderness in that hospital, a looking-out-for-one-another that nearly made me not mind them. We were all raw with our own failure, and as well as that our minds were turned down low with drugs so we weren’t so keen on judging. That was a kind of liberation, for what could you do at the bottom but laugh—the laughter of gentleness, not of derision? Derision was for out there. Derision and fear-of-derision had landed us in here. We had broken ourselves on our own wheels, trying to be what we thought was required of us, trying to be “normal.” Failing. In here we moved slowly, taking care, as wounded things take care. Oh, there were dislikes and resentments alright, but only because we were human. Mostly we were as careful of each other’s sore places as of our own, or nearly so. And in a funny way there was no one out there as real for us as the ones inside that we lived with every day. Perhaps what bound us together was pity more than love. I don’t know, I don’t know where the one stops and the other starts.

I was discharged before Michael was. I wrote out my address and I said good-bye, and it never once crossed my mind that I might not see him again. I’d accepted the gifts he’d given me—gifts that were given freely, as you give when you are young. I took them without thought or gratitude; took them in the fullness of youth, when life is opening and everything seems natural and yours by right.

I sent him a postcard. Later on I scribbled half a letter, but I lost it on a bus. I never rewrote it. I was living my life, I forgot about Michael. When at last I remembered, my letter came back with “unknown at this address” scrawled over the envelope. Perhaps he’s alright, perhaps he’s alive, but I get no sense that he’s out there still. The depression was very bad with him; it never let him alone.

I am thirty-six and already so much left undone and regretted. What will I do when I’m old?

Chapter 4 (#ulink_c82ab1e5-53dd-5a5a-ae85-18c1808a9ccd)

Where was I? The day after the night I first met Liam. Saturday. I met him again in the street late that morning. He was walking towards me, his head down, his eyes on the pavement, no sign of Noreen. I was dying with the hangover and the lack of sleep, but I wanted to be out of the flat and away from Robbie, away from Robbie’s foul words, away from the misery in his eyes when he came out with them.

I’d told him I’d messages to do. I was out the door almost before he knew I was going.

When I saw Liam my first thought was to turn on my heel and run, but I didn’t. I’d be past him in a flash, I told myself, there was no call to be drawing attention to myself, running off like an eejit. So I went on ahead, my eyes on the ground, the same as his were. Then the next thing I felt a hand gripping my arm and a voice saying my name out as if it was news to me.

“You can leave go of my arm,” I said. “I’m not about to run off with your wallet.”

He let go. He said he hadn’t seen me till I was nearly past, he hadn’t meant to hurt me.

“How about a cup of coffee?” he added. “Wouldn’t you let me buy you a coffee or a drink or something? Would you fancy a bite of lunch?”

No, I said, I didn’t want a drink, or not yet, and where was Noreen, wouldn’t she be wanting her lunch any minute now?

“That should keep you busy and out of trouble,” I added nastily.

“Noreen got the early train to Dublin. Said she couldn’t be doing with Northerners. Always arguing and complaining and telling the rest of us what to do. Said she knows when she isn’t welcome, even if I don’t.”

“And don’t you?”

“Oh, I do. It’s coming through loud and clear, I just don’t want to admit it’s what I’m hearing—”

My head hurt, and I wanted to get away from him. By now I was well on my way to forgetting all about the business with him the night before. It seemed like a dream, a stupid dream, and I was sick of myself and the way I let my imagination lead me up garden paths. Then he put out his hand and took mine. Straightaway I was back there, ready to drop with the knowing of what I had known last night. And with the fear of it.

He didn’t let go of my hand. Instead he put his other one under my elbow and drew me round to face him. I kept my head down, my eyes well away from his. But I let him move his hands to my upper arms and hold them there to steady me. After a while his hands dropped.

“Right,” he said. “Lunch,” he said, and steered me into the Sceptre and sat me down in a snug. Then off he went to the bar and came back with sandwiches and pints of Guinness.

“I don’t like Guinness,” I said.

“You could do with building up.”

I don’t remember any more than that, I don’t remember what I said next or what he said next or whether I drank the Guinness or left it sitting or poured it over his head. But I remember how I pressed back into the chair, how I tried to get small and still inside my clothes to get away from him. He never touched me, and I never touched him, but when I got back to the flat two hours later, I had a story ready for Robbie and I wasn’t slow running it past him. I told him I’d rung my mother from a pay phone while I was out. Brian and Anne and the babies had been there with her.

“They’re away off to the West for a week’s holiday,” I said. “They’ve rented a house—a place off the coast of Mayo called Achill Island. Brian came on to ask did we want to come with them?”

Robbie was looking at me, but I was busy taking the dishes off the drainer and stacking them into tidy piles by the sink.

“We?” Robbie said, so I knew he’d bought the rest of the lie.

“Well, not exactly,” I said, still not looking at him. “He asked were you working, and I said you were. Then he said did I want to come?”

A new cottage had been built hard behind the old one, its front door facing across to the other one’s back door. For the old couple or maybe the young couple—family, anyway—a natural proximity. Sometime later someone had added a joining arm so the two had become the one, with a bit of a yard in the space between. Hardly even a yard. Just a rough place for hens to pick over and washing to hang, sheltered from wind and weather.

Achill. We’d been there four days. I had carried a kitchen chair out and was sitting doing nothing at all, the gnats rising, the shirts I’d washed in the kitchen sink just stirring in the quiet air. Liam had gone off after groceries and a mechanic to look at his car. There was a noise he didn’t much care for in the engine, he said, and maybe he wanted some time off from me as well, maybe he’d bitten off more than he could easily chew. For myself, I was glad to be on my own. My thoughts went wandering about in the whitish sea light that you get off that western coast.

The yard was three sides cottage, with the fourth side closed off by a big thick dark fuchsia hedge, red now with hanging blooms that were starting to drop. It was early September, a bare two months since they’d let me out of the hospital, a bare four since the bomb had gone off that killed Jacko and left me not able to stop crying. The yard had been covered over with a scrape of rough concrete, breaking up now so the weeds and the moss had taken hold, the whole place littered with things that were most likely never going to be used again but just might come in handy one day: broken boards and odd stones and shells carried up from the beach, floats for a fishing net in a tangled heap, a black plastic bucket half filled up with rainwater over by the wall. A shallow brick drain was clogged up with silt and leaves and drained nothing.

If I lived here I might learn to do less, I thought. To wash less, to go on wearing things that were soiled. Even in the few days we had been here the urge to clean it all up had died in me. I no longer itched to chuck out the junk, to unblock the drain, to sweep it all down; I no longer wanted to do anything much except sit on the straight-backed chair in the soft bloom of light and stretch out a hand to check the shirts on the line.

On the first day I’d washed all the windows in the kitchen. I’d intended doing the whole house, there wasn’t a clean window anywhere; they were splattered with rain marks and mud and had deep layers of ancient cobwebs veiling the corners. Liam laughed when he saw what I was at. I asked him why, and he went red and shook his head, but I pressed him and finally he said he thought it strange to be starting in on cleaning on your holidays.

But that wasn’t why he’d laughed, and I knew it. I kept on at him, and he went redder, but still he wouldn’t say. In the end he gave in and told me about being on the sites in London and working alongside an old Cockney who thought Liam was way too innocent and needed wising up. He had a dirty old tongue in his head, Liam said, but he meant well—he was forever passing on bits of tips and information. It seems he’d told Liam to look out for women who were workers because women who were workers were always on for sex.

I rinsed out the cloth in the water, then turned and washed down the last pane. But I didn’t give them a shine with newspaper as I’d intended, and I didn’t wash any more. I was angry. I didn’t laugh and brush it aside; my mind closed like a trap round his words. I remembered Robbie—what he’d said about knowing as soon as he saw me that I was repressed, a volcano ready to blow.

I’d made a mistake with Robbie, I thought, and I was surprised at myself, for this was the first time I’d let myself think such a thing.

Now it looked like I might well be on the way to making another one with Liam. I took my coat from the peg without a word.

“Where are you off to?” Liam wanted to know.

I didn’t reply. I shrugged on my coat and was gone through the door without looking back.

Out on the road I went steaming along, the wind on my face, my hair ripping out, the bog stretching red-brown to either side. The sky was flying above me; the wind keened in the telephone wires; my ears sang with the lovely fresh running noise of water going pelting down the ditches. With every step I took I was freer, the anger draining away.

“What ails ye?” Liam was asking me, coming up from behind.

“You know rightly,” I said, without slowing down. He started to say he was sorry, but I wasn’t having it, I turned around to his face.

“Why shouldn’t women like sex?” I demanded. “And why do men have to sneer and joke if we do? Wouldn’t you think men would be pleased that we like it? Wouldn’t you think it would make life easier all round?”

He stared. He started to try to say something, but I only laughed in his face. I threw my arms round his neck and pulled him to me; then I undid my arms and pushed him away and went striding off over the bog, all the anger gone from me.

It’s a wonderful place, Achill; there never were such skies. I was used to skies from Derry, but still it wasn’t like Achill. Achill had the best skies that ever I saw in all Ireland. It could be ink black up ahead, but away to the left you’d see light breaking through in a shaft like a floodlight, while off to the right there’d be rain, a grey curtain, and behind that again you’d see where the rain had passed over and the land was shouldering its way back up through the gloom.

So we went striding along together, all thought of regret vanished clean away and Robbie only a flicker of guilt at the back of my mind.

Night came, and we sat by the smoking fire with a bottle of whiskey that I was throwing into me but Liam had hardly touched. It was awkward as hell, but I didn’t care. We’d ease up in bed and no need for talk—our bodies would say it all. Or that’s what I thought, but I’d reckoned without Liam: when I put my hand on his leg, you’d think he’d been stung by a wasp.

He hadn’t brought me here, he said, for that.

“Why not?” I asked him. “What’s wrong with that?”

It seemed Liam thought we should learn to talk first.

“If we can’t talk,” he said, “there isn’t a future—”

I gaped at him. No future was fine by me. A bit on the surface of me was playing with the notion of leaving Robbie, but deeper down that wasn’t what I meant to do at all. Deeper down I wasn’t leaving Robbie, I was having a bit of a fling with Liam and while I was at it destroying whatever shared future I’d glimpsed that night in the bar. I was trying to avoid my fate, you see; I thought I could go with him to Achill and then sneak back home again to Robbie. Outwit my fate, give it the slip.

So I sat there, not believing what I was hearing, thinking it all some game on his part that would resolve itself in an hour or so’s time in the bed. Only it didn’t. He’d taken himself off to a different bed the first night, and the next and the next. And for all I knew he would do the same tonight.

In the day we’d walked long, long walks, together but alone. And now we were both so miserable we were relieved to be apart.

I sat on, thinking these thoughts, glad of his absence, wondering should I cut my losses, find a bus, and head back to Belfast, but knowing I wasn’t yet able for Robbie or the city. Beside me on the windowsill were two oval stones, very white, and the skull of some long-dead ewe. Or some long-dead ram—how would I know? What did I know about sexing live sheep, much less something like this, stripped of its flesh and blood?

It was ugly, the bone grey and pitted, the horns broken off at the tips. A row of hefty grey teeth stuck out from the upper jaw, but the lower one had long since vanished away, and round holes, empty and dark, stared out where the eyes should have been. Once it was its own sheep, I thought, with some sort of life of its own and some sort of consciousness. Idly, I looked down at my hand in my lap, imagining the bones lurking under the flesh, wondering would they stay linked in the grave or fall away, like the sheep skull’s lower jaw.

I should have kept a tighter hold on my thoughts, for I got more than I’d bargained for. I watched, and my skin turned yellowy-blue, as though it was badly bruised, then puffed and swelled, and the yellowy-blueness darkened into black. A foul stench hung on the air, and I saw my flesh breaking open, heaving with maggots and pus. I screamed and jumped up. I tried to throw my hand off from me, but it stayed joined onto my arm. It was like trying to throw your own child away; you can’t do it even if you want to, you can’t rid yourself of a part of yourself just because you don’t like what it does or says or because it’s manky with maggots.

I don’t know how long it lasted: it might have been half an hour or only seconds. But I watched, and it all changed back. My hand was my hand, the flesh clean and regrown, and not a maggot in sight. I reached for my cigarettes, but the same hand shook so hard I couldn’t get one out of the packet.

Sweet Jesus, I thought. Not that again, don’t let it be that again. How am I going to live if I can’t even think a thought without seeing it act itself out before my eyes?

But it was—I knew well that it was. I was seeing things again. Barbara Allen and Jacko Brennan came flooding back, and my little bit of quiet and kind idleness in the broken yard was gone.

I sometimes wonder now, could I have left Robbie if Barbara Allen had lived? There are times when I think I could, but more often I think I couldn’t. He wouldn’t have let me take her, that’s certain sure, and I don’t think I could have defied the whole world and myself and gone off without her, but I don’t know. It’s no good thinking and saying to yourself “I’d do this” or “I’d do that.” You don’t know till it happens; you don’t know what you will find in yourself till it’s found.

What I do know is that I couldn’t have gone to Liam half as easily as I did if something of what had been between Robbie and me hadn’t died along with Barbara Allen.

But all that was ahead, and nothing to do with my standing there, shaking from head to foot, my eyes on the sheep’s skull, full up with fear. It wasn’t that I thought it foretold anything. It was it happening at all that scared me stupid. The bruising, the maggots, the pus—they had come and gone in a flash—but the speed of it all somehow only made the thing worse. It was as though my life were a bicycle I’d been riding happily down the road: one minute I was up there, the wind on my face, and the next I was sprawled on the tarmac, broken-boned and with all the wind knocked from me.

I didn’t hear the car; I didn’t hear Liam getting out or shutting the door or walking around the house. The first thing I knew he was standing in front of me, and I moved forward without knowing what I was doing and threw myself against him. His arms went around me and held me, and I never wanted him to let go. He held me without words, but small, soothing noises were coming from low in his throat, the same sounds you make to comfort a hurt dog.

I don’t know how long we stood like that, and I don’t know how we moved from being like that to sitting together there in the yard, his hand holding mine, me telling him in a big jumbled rush about what had just happened, about Barbara Allen and Jacko’s death, about the hospital and its drugs which had stopped me seeing things.

The empty eyes of the sheep’s skull stared from the sill.

“Is this the first time you’re after seeing anything since the hospital?”

I shook my head. “The night I met you—there was something then.”

He just nodded; he didn’t ask what. I put my hands over my face, and I started to weep. I felt the tears running through my fingers and down my wrists. He stroked my head, then he shifted a bit and put his arms round me again, and I wept into the warm place under his chin. After a while I stopped. I drew away from him. I patted my pockets, looking for something to blow my nose in, and I found a scrumpled bit of tissue and blew. I felt better. The weeping was a release, it had got me past the fear to a place where what was happening to me was simply what was happening, it wasn’t any longer something I was desperate to shut out.

“D’you think have I a screw loose?” I said when I’d finished blowing.

He shook his head. “I do not. You see things. Sometimes just things. Sometimes things that are going to happen but haven’t happened yet. That’s not the same thing as having a screw loose.”

I looked at him then. He was so serious and so innocent, his grey eyes very round and wide open, his brown curls lifting in the strengthening breeze. I started to laugh. He looked surprised, then a bit offended.

“What’re you laughing at?” he asked.

“You,” I said. “Is there nowhere you’d draw the line?”

“What d’you mean by that?”

“If I told you there was a wee man dancing a hornpipe on your left shoulder I think maybe you’d believe me.”

He smiled. “Why not?” he asked. “Because I don’t see something doesn’t mean it isn’t there. It just means I don’t see it.”

Fear hit me in the belly with the force of a man’s fist.

“You don’t see it because it isn’t there,” I shouted at him. “It’s a chemical in my brain, making me think I see things, that’s all. But they’re not there, they’re not there, they’re not there—”

Everything crumpled, and I started to sob again. “Easy now, easy,” he was saying, holding me tight in his arms and stroking my hair. “Easy, girl, easy.”

The wind had risen in the night. Storm waves rolled in, and the damp sands blew with flocks of shiny bubbles like tiny hermit crabs scurrying off sideways as fast as they could go. Further down there were big curvy swathes of pale foam, and I took off my shoes and walked in them, kicking the empty white fizz with my bare, bony feet, making it fly. The wind blew, and the clouds raced over the big, clean sky and the air snapped and rushed about my head like a flag. Where the beach curved out of the wind there were stranded castles of dark-cream foam like the tipped-out froth from hundreds of pints of Guinness.

A lone dog was trotting about, some sort of a collie cross, black and white with splashes of tan. When he came to a castle he’d crouch down and bark, his tail would lash back and forth, then he’d pounce. Nothing. The castle had disappeared, leaving only splatters of foam and claw marks deep in the sand. He couldn’t work it out. He’d stand there with such a puzzled, affronted expression on his face that I laughed aloud.

I was happy as a lark. We both were. Happy with the happiness of two people who have just found each other’s bodies and are amazed by them. Liam hadn’t moved away off from me after the time in the yard. It showed in a touch to my hair, a hand on my arm. Later, when I’d sat in beside him on the sofa, his arm had gone around my shoulders and stayed there. After that it was only a short step to bed and the pleasures of bed.

And pleasures they were. We had bodies that matched on a deeper, surer level than anything I’d known with Robbie, though Robbie was more athletic and knew better what he was doing. But Liam made me laugh, which Robbie never had. He talked to me, where Robbie was all silent concentration. And Liam got hungry—he was forever jumping out of bed and bringing back half the fridge and spreading it out on the coverlet. Then he’d feed me from his hand till I felt like a bird or a horse. Soon the sheets were greasy with buttery prints, and I slept with tiny islands of discomfort on my bare skin, never giving it a thought.

I should have known from that. I’m too fastidious by nature not to mind, and I didn’t. I thought I was only in ankle deep, when I’d waded in up to my neck.

But that day we were only beginning, and it seemed all the weight of the last hard months had fallen away and nothing but ease remained. We went strolling along the strand, the dog trotting behind us, the tide pulling out and out till you felt you might walk to America. Liam asked me why I feared it so—this habit I had of seeing things. Was it on account of not knowing if it would stop?

I didn’t answer him. I picked up a length of stick that the sea had laid down, and at once the dog was lepping and yapping for me to throw it. I didn’t. Instead I wrote my name in big broad strokes on the sand. Then I looked at Liam out of the corner of my eye and I wrote his name under mine. Then I wrote “Dandy the dog” under his. I took another peek at him to be sure he was watching me, and I lifted the stick and drew a big wide circle around the three names, linking us all together. He was disappointed, and I knew he would be. When I went to circle the names he had thought it would be with a heart. And it almost was, for it seemed a small thing to do for him when he’d made me so happy. But I held back, I wanted to stay in the happiness; I didn’t want to move on into hearts and love and all the trouble they’d bring. I dropped the stick and fell into step beside him.