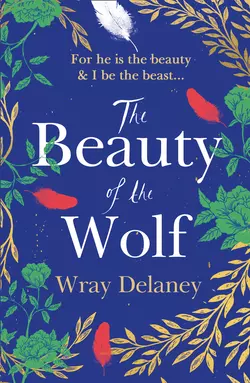

The Beauty of the Wolf

Wray Delaney

'What some might call beauty, I find monstrous'In the age of the Faerie Queene, Elizabeth I, Lord Francis Rodermere starts to lay waste to a forest.Furious, the sorceress who dwells there scrawls a curse into the bark of the first oak he fells:A faerie boy will be born to you whose beauty will be your death.Ten years later, Lord Rodermere’s son, Beau is born – and all who encounter him are struck by his great beauty.Meanwhile, many miles away in a London alchemist’s cellar lives Randa – a beast deemed too monstrous to see the light of day.And so begins a timeless tale of love, tragedy and revenge… A stunning retelling of Beauty and the Beast

WRAY DELANEY is the pen name of Sally Gardner, the award-winning children’s novelist, who has sold over 2 million books worldwide and been translated into 22 languages. She lives in East Sussex, and this is her second adult novel.

Copyright (#ulink_4309f947-e3c3-5493-a31a-70e7031e4c25)

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Wray Delaney 2019

Wray Delaney asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008217389

PRAISE FOR WRAY DELANEY (#ulink_e24c446c-8fc3-546b-96d1-9ee860e26705)

‘Shades of Sarah Waters … irresistible’

Guardian

‘Compelling’

Sarra Manning, Red

‘A bawdy, romping affair’

The Times

‘This is one hell of a read’

Sun

‘A fun, explicit romp with real stakes that will have you trying to finish this book in one sitting’

Stylist

‘An irresistible world to drop into’

Emerald Street

‘An amazing book… like a box of treasures’

Meg Rosoff

To Julia, the wisest woman I know, whose love

and patience have been my greatest anchor.

Contents

Cover (#u32c1b426-e1b9-5aa6-94dd-06ea719a4694)

About the Author (#uf9baf8cd-6a5b-5886-b41f-fa988be6ab8f)

Title Page (#u2edaff5b-74f6-50a8-a703-c59c61b68436)

Copyright (#ulink_96bfc655-0d8c-5118-bb3e-a805a9ba7b09)

PRAISE (#ulink_e336c395-88dc-5b0e-9026-cbfab16e5765)

Dedication (#ue4de94b8-a793-533d-8285-e6160e96d6b4)

THE SORCERESS (#ulink_ce61d01e-33ae-50bc-96e0-21e727e9d09f)

CHAPTER I (#ulink_1fbe6a38-5527-57c4-b0c7-3d76b2ad330b)

CHAPTER II (#ulink_00cc27d2-9e17-59ea-96e3-6554c4d2d2b0)

CHAPTER III (#ulink_f278e06b-812c-5395-b83c-fc4331a0a5d8)

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_a9fbea81-21ee-5407-b3ec-e1c548f80fee)

CHAPTER V (#ulink_b931e8fa-dbbc-5842-8376-b3bdd8c93f11)

CHAPTER VI (#ulink_ea506eb5-bd7f-549f-93f8-10c137cf4599)

CHAPTER VII (#ulink_b0924aac-9d0e-5290-ad39-9251c1a3016b)

CHAPTER VIII (#ulink_25c4c68f-6d0b-5276-a8e8-56981333e9b0)

CHAPTER IX (#ulink_acc0eb2d-4acf-557b-ada5-00146d0e7c80)

CHAPTER X (#ulink_97af841c-5331-5df9-b88c-0bc8b2d5cad0)

CHAPTER XI (#ulink_80900f5e-0ca4-56e0-bc7f-c4e94613d267)

CHAPTER XII (#ulink_bb4a0e48-6f30-58c7-ba7c-da0317d256f5)

CHAPTER XIII (#ulink_1e2d6c8c-9d65-53a7-ab69-e0324c3cdd32)

CHAPTER XIV (#ulink_c20f9ca7-15bc-5a09-8a22-5584a7984a3b)

CHAPTER XV (#ulink_c8ab1534-e603-5de5-a16f-60027806a6f1)

CHAPTER XVI (#ulink_59abded5-35a0-50bb-a99e-7e5b7cfc9c04)

CHAPTER XVII (#ulink_25cf4db9-532d-531a-b49a-f7b08d069916)

CHAPTER XVIII (#ulink_d31eb89b-daf1-5370-9f4c-3906c35249d0)

CHAPTER XIX (#ulink_1f0c7ee3-6b0c-58c0-b148-84a8bb25c666)

CHAPTER XX (#ulink_2a72bc24-fcf2-5e05-9a6e-e913104d11b8)

CHAPTER XXI (#ulink_c331f355-f3fc-50dd-b9a6-d9ca39b733e8)

CHAPTER XXII (#ulink_99a55a08-afb4-5e12-8881-58182c309732)

CHAPTER XXIII (#ulink_73eed5dc-11ab-5864-91bc-17f17ff24442)

CHAPTER XXIV (#ulink_0960b8e6-6a16-517e-90a6-e6469f533e08)

CHAPTER XXV (#ulink_1eec1671-4f9c-5983-8fb3-8fd82ba5072b)

CHAPTER XXVI (#ulink_fafcecf4-735c-5250-adf3-78f5ef4f8b84)

CHAPTER XXVII (#ulink_7ec593c6-ae88-5b4d-869b-df6004f2e086)

THE BEAST (#ulink_659494b7-3735-5f11-b498-2bd8f2726098)

CHAPTER XXVIII (#ulink_6cc369cb-427e-5f76-9118-1c62594aab70)

CHAPTER XXIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXX (#litres_trial_promo)

THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXVI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXVII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXVIII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XXXIX: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XL: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLI: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLIII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLV: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLVI: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLVII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XLIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER L (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LIII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LVI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LVII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LVIII: THE SORCERESS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXIII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXVI: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXVII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXVIII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXIII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXIV: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXV: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXVI: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

THE BEAUTY OF THE WOLF (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXVII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXVIII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXX: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXV: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXVI: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXVII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXVIII: THE SORCERESS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER LXXXIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XC (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCIII: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCIV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCV (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCVI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCVII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCVIII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XCIX: THE BEAUTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER C (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER CI: THE SORCERESS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER CII (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER CIII: THE BEAST (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER CIV (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

THE SORCERESS (#ulink_50cf8ca1-cd49-5cd9-a975-01c9534395ba)

When I go musing all alone

Thinking of divers things fore-known.

When I build castles in the air . . .

THE ANATOMY OF MELANCHOLY ROBERT BURTON

I (#ulink_b8048def-6873-5e99-9a8e-c99dab596a21)

I woke when the mighty oak screamed.

No mortal heard the sound those roots made when their weighty grip upon the soil was lost to them. No mortal saw the desperate clawing at the earth, the very life snapping from the trunk as the ground crumbled, shivered with the cacophony of destruction. How could I sleep, tell me, for it had awakened the very rage in me.

My oak trees outlive men by hundreds of years, yet it is these mortals with but a few seasons to their names that claim the wisdom of God in their insect hours upon this earth.

I have no time for sweet, enchanting tales that fool the reader with lies and false promises. Too long I have lived and seen, and seen yet never said, been counselled strong to leave off the telling of my tale. What care have I for such timid sentiments? Let the Devil make his judgment.

Do you not know me? I was born from the womb of the earth, nursed with the milk of the moon. Flame gave me three bodies, one soul. In between lies my invisibility. I am the maiden, the mother, the crone, in all I am one. You think that I am unlike you. Look again. I am the dark side of the glass, proud to own my power for good or for ill.

My sorcery, unlike your malcontent prayers, cannot be undone. I relish my powers to shift my shape without boundaries, to move freely between the holy trinity of women. No church would ever make me give up my body in all its lustful glory to a fleshless lord. For what purpose? To be tamed, to live in servitude, to be robbed of my mystery?

Why then should I remain silent just when the mortal world has decided to overthrow magic in favour of religion and rational thought? When our ways are about to be sacrificed to the Lord of Despair, he whose feet never touched this earth of mine?

I could have dreamed my way through such lunacy, deep under my trees, wrapped safe in darkling sleep and all that happened would never have happened. For the loss of one oak tree I put my curse on he who claimed my church, who had the arrogance to fell my cathedral. I might have forgiven him one of my glorious, bejewelled treasures, but Francis Thursby, Earl of Rodermere, would have none of it. Foolish jester. He had no idea at whom he jangled his bells.

Come then, follow me down, for I am but the crack between the words, a riddle to be solved. Come, follow me, into the shadow of a sorceress’s spell and think no more of my presence. I am but the unseen, all-knowing storyteller.

No man should have dared to wake me. No man. No man.

II (#ulink_aa9cad38-3401-55af-9330-3ecb25469f01)

There is little merit in sticking pins in time, in searching for a date to tie this story to. Suffice to say it is set in an England ruled by a faerie queen, a period of ruffles and lace, of wrought velvet and blanched satins, silk stockings costing a king’s ransom. It is the age of imagination, when the philosopher’s stone would make gold of your dreams. A time when the world became curved and the seas led to strange lands and brought back unknown treasures. It is the day when the play be everything, and all men’s lives had their season there. And it would have meant nothing to the sorceress.

In her chamber deep underground she dressed in all her finery. Her petticoat was the colour of damask rose and in the embroidered stitchery lay her magic, ancient as snakes, the very weave of the cloth testament to her power. She wore her crown of briars on her amber hair, a ruff of raven’s feathers, a farthingale embroidered with beetles black as jet. Her skirt borrowed from midnight’s wardrobe showed the hem of her petticoat beneath. And in the witching hour she went to find him.

III (#ulink_e66a50f1-77be-5499-a485-254ec4537810)

Invisible in her cloak the sorceress took the measure of the man before making her appearance. She had found Lord Rodermere at the refectory table where once the monks had dined in silence. He was a large, sprawling man whose doublet battled to contain his flesh. His small eyes that suited swine looked mean in a man; his nose dominated his features; his lips, hard, thin. It was not a handsome face and his fondness for the wine accounted for the redness of his complexion. The stags’ heads on the wall were testament to his passion for hunting.

Lord Rodermere’s father, Edmund Thursby, had been given the monastery and its lands by a king who, in need of a new wife, had the monks made destitute. The late Earl of Rodermere had lived there and done nothing to its chambers that were bitter cold even in the summer months. Neither had he touched the forest other than to care for it by good husbandry. He had applied the same principle to his land and his people. Unlike his son, he had had the wisdom to leave the great oak trees alone for he believed in the tales of the forest, of the sorceress and the wolf. Only those who did not live in those parts and were ignorant thought these stories to be no more than faerie tales.

When Edmund Thursby died, his son returned home from fighting abroad determined to build a manor house from the forest, as if by the destruction of the oak trees he would be hacking at the roots of pagan beliefs. He had sworn to rid his land of superstitions, bring his peasants under the control of the church and there such nonsense would be banished, by force if necessary. He would prove that man is master of nature and if in the heart of the forest there were both sorceress and wolf, he would hunt them down with horse and hound and kill them.

Three mastiffs lie at Lord Rodermere’s feet. His page serves him wine, hands shaking as he lifts the jug to refill his master’s goblet. Irritated, Lord Rodermere pushes the boy away. For all his bravado he looks uncomfortable in the dining hall of shadows. His dogs stir, their hackles rise, they snarl. They sense an unknown presence.

‘Quiet,’ says Lord Rodermere. ‘It is only the wind.’ And, cursing, he demands more wine. The page, pale of face, refills his glass. ‘What? Are you frightened of a breeze?’

‘No, my lord.’

The muscles tighten in Lord Rodermere’s neck, beads of sweat form on his forehead. His heart pounds faster than it should. He jumps when a log falls into the fire.

‘More candles,’ he demands.

More candles are lit and the unseen, uninvited guest takes pleasure in blowing them out one by one. The servants and the dogs back away from their master. It is only when he lifts his wine once more to those dry lips that the sorceress appears before him in a blaze of light. His lordship’s hand loses its grip on the goblet which clutters to the floor.

Time stops. And her voice echoes in the rafters.

‘Francis Thursby, Earl of Rodermere, I will grant you any wish you might desire if you will – as your father did and the monks before him – leave my forest be. I am prepared to be generous.’

‘What godless creature are you? From whence did you come?’

He is wondering if this be the Devil in the form of a woman.

His deep voice quavers. ‘By what trickery do you conjure yourself before me? Who are you to claim my oak trees and my land, to threaten me, your lord and master?’

‘You mistake me,’ says the sorceress. ‘I do not threaten you. And you are not and never will be my lord and master. I have come to tell you plainly what you must do if you are not to feel the burden of my curse upon you.’

‘What did you say, mistress?’

He is shocked that a mere woman would speak to him thus. He calls for his servants. He stands high and square and points to the sorceress and orders that this witch be thrown out. Not one of his men dares go near her. Lord Rodermere was not expecting such insubordination. His temper now well and truly lost to reason, he bellows for his steward.

Master Gilbert Goodwin, who was born in these parts and knows them well, comes quickly, his footsteps ring on the stone floor as he enters the hall and slow when he see the sorceress.

‘Lock her up and call the sherriff,’ commands his master.

Master Goodwin – wisely – stays where he is.

‘Did you not hear me?’ shouts Lord Rodermere.

‘My lord,’ says Master Goodwin. ‘You would do well to hear her out.’

His lordship draws his sword.

‘Do you disobey me too? Be careful, Master Goodwin . . .’

The sorceress raises her hand to silence the fool. She has had enough of his blabbering tongue. One look is all it takes and stock still he stands, mouth wide open, unable to move. The sword falls from his grip and, like the goblet, clatters to the floor.

‘You should do as Master Goodwin suggests,’ says the sorceress. ‘You should listen to every word and mark it well. Fell another of my oak trees and I will put a curse on you that no man will have the power to undo. But leave my forest be and I will grant you one wish.’

She snaps her fingers and Lord Rodermere is returned to the trumpets and drums of his fury. He shouts at her as if the sound of his voice will have the power to undo her threat.

‘Woman, your charms and other such trumpery be worthless. I damn you as a sorceress, a bullbegger.’

And before his eyes, she vanishes.

IV (#ulink_fa909347-2020-5402-85ca-84b3a5a4f71c)

The next day at dawn, to show his mettle and his belief in a higher heaven, Lord Rodermere felled the second stag oak – broader than three kings and taller than any church in those parts. The majestic tree had stood sentinel over the forest, half in shade, half in sun so that it knew both the woods and the fields. Autumn had not yet stripped the tree of its cargo of leaves, yet regardless it was crudely felled. Sap blood on the earl’s hands, the sorceress’s curse upon his soul. She wrote it on the bark of that noble fallen tree, words written in gold for all to see.

A faerie boy

will be born to you

whose beauty will

be your death.

Lord Rodermere laughed when he was shown it.

‘What jade’s trick is this?’ he said to Master Goodwin. ‘Does she think I would be soul-feared by such sorcery?’

His peasants trembled when they saw the words but not because of their master’s threats. They knew from the ancient laws that it be a bad omen that the words be written in gold, that they be etched so deep into the bark.

A bad omen indeed.

For every oak that Francis felled, the sorceress’s curse went deeper, slithering into the branches and the very roots of the Rodermere family tree.

As seasons passed and gathered years with them, one turret rose out of his grand house, then another, slightly taller, and finally the third turret rose higher, taller than the tallest oaks, a monstrous scar upon the forest. The sorceress’s land was cleared to make way for a park, gardens, jousting grounds, orchards of stunted trees. The house itself had claimed four thousand and sixty of her oaks. Its banqueting hall, its chapel, its carved wooden panelling, its long gallery, its staircases – all from her oaks made. Those faithful trees told her the truth of that family, of the twisted knots of its unhappiness.

In their dying, dried-out whispers, they said, ‘He has no son, he wants a son. Two daughters born, two daughters dead and still no son has he.’

They spoke of a house petrified, of Lord Rodermere’s many cruelties, of his servants who shivered at his presence, of his wife who dreaded his voice at her chamber door.

It was the Widow Bott who told the sorceress what her oaks could not, she being the local midwife and cunning woman, and close with the servants at the House of the Three Turrets. The sorceress knew her well. There was not a babe born in these parts whose birth she had not attended except those of the daughters of Eleanor, Lady Rodermere. Her arrogant, bumble-brain, shit-prick of a husband never wanted the Widow Bott near his wife. The widow was a handsome woman, her own mistress and had not succumbed to his oafish charms. In a fury at being rejected, he had threatened to ruin her unless she lay with him, accused her of putting him under a spell, stated publicly that he distrusted her forest remedies and advised all godly men not to let her near their wives for he believed her to be a witch.

In that alone he was right and it was the powers of the sorceress that had made her so. He should have known no one lived in the heart of her forest unless she had invited them there. The monks who first claimed this land had been wise enough to fear the darkness of the woods where the sunlight had little power. They began to believe that at the heart of forest, in the darkest place, lived the Devil himself in the guise of a black wolf. These stories grew in the retelling until the black wolf took on monstrous proportions. It was dread of this beast that stopped many a brave heart from venturing deep into the forest but it did not stop Gilbert Goodwin.

When first the sorceress laid eyes on him he was but a lad, adrift in her realm. He showed no fear, only a curious interest in finding himself with night coming on and his path lost. And being alive to everything he watched the moon shine through the trees, bewitched by the darkness that lifted the curtain onto another forest more magical, more savage than that of his daytime wanderings. He climbed one of the sorceress’s oaks and slept in its mossy hollow till morning. Then, refreshed, he found by her design the rich larder of the forest where he gathered mushrooms and there saw his way home.

He was apprenticed to the steward of the late earl, Edmund Thursby, and the earl wisely saw in him more than a glimmer of intelligence. Gilbert Goodwin had learned a great deal from the old earl. He had admired his care of the forest and respect for his peasants.

Master Goodwin understood his neighbours. They may well go to church on Sunday, sit through dull sermons, chill their knees on stone floors, yet he knew in their souls they prayed that the black wolf stayed in the heart of the forest and did not eat their livestock or their babes.

After the sorceress’s oaks were felled the sightings of the black wolf became more numerous. Its very size and shape belonged to a deep magic that Gilbert Goodwin knew should be respected if you valued your life and your land.

All this the sorceress had learned for she oft walked invisible beside Master Goodwin, listening to his thoughts, though he was never aware of it. He had filled out the thinness of his youth, grown well-built with a kind, thoughtful face and grey eyes that saw more than many and a tongue wise enough to hold its peace until speech became necessary. Francis, Lord Rodermere, for reasons that he could not fathom, felt inadequate when speaking to his steward. Even in height, Master Goodwin was superior.

On a spring morn they stood together, side by side, in a graveyard of oaks whose stumps stood as raw wounds that broke from barren soil, their once ethereal canopies but a ghost’s memory. Now in this new season there was no leafy protection from the rain that drizzled on leather and fur, that dripped from brims of hats. Gilbert Goodwin’s thoughts that miserable morning were filled with sadness for the utter pointlessness of such destruction. He looked at the standing trees and wondered if they too were doomed.

‘It is only a matter of time before the head of that black wolf is nailed to my wall,’ said Lord Rodermere. ‘If it were not for the quality of the hunting I would have these woods felled. That would put an end to the pagan beliefs of the peasantry.’

‘The forest has stood for thousands of years, my lord,’ said Master Goodwin. ‘You are the first man to have had an axe taken to those great oaks.’

‘Do not say that you, like my buffoon of a father, believe in all that elfin gibberish.’

‘Your father was a wise man,’ said Master Goodwin, ‘and understood his people. I would call a buffoon a man who thinks he knows everything, is averse to all advice, who acts without knowledge and is driven by conceit, only to be surprised at the consequences.’

Lord Rodermere was unsure if he had just been insulted by his steward but not knowing how to respond if he had, he continued.

‘You believe that some sorceress has the power to put a curse on me?’

‘I believe,’ said Master Goodwin, his grey eyes never leaving his master’s face, ‘that you would have fared better if you had let the forest be, and built your house of bricks and mortar. This forest has always been a place of great beauty and greater terror.’

Gilbert Goodwin’s wit was too fast for the slow, wine-soaked brain of Lord Rodermere, who in order to enforce his authority said, ‘You are not seen often in church on Sunday. Do you worship at a different altar?’

Master Goodwin did not answer.

‘I thought you better than a mere peasant.’

Again the steward held his tongue.

‘Never married?’

‘No, my lord.’

‘Why not? Is your prick so small it could bring no woman satisfaction?’

Gilbert Goodwin, well-versed in his master’s rages and jibes, had expected as much. Lord Rodermere was thinking of his own baubles.

The hands of time tick on, the sorceress’s remaining oaks, her elders, and her ashes – white trees of death – move imperceptibly closer to the House of the Three Turrets. For all his lordship’s boast of glass windows very little light shines in and long shadows fall across his lordship’s gardens and his lordship’s orchards.

Lady Eleanor bears him a third daughter. The child lives, but smallpox makes her soft skin toad-blemished and only now does Lord Rodermere begin to wonder if he has indeed been cursed. He enquires of his steward where he might find the sorceress who visited him when he hacked the first oak. Master Goodwin tells him plainly that it is best he looks no more. This time Lord Rodermere does not laugh so loudly for the words of the curse are echoing in his empty head.

. . . whose beauty will

be your death.

V (#ulink_90ec1109-7801-5e79-b962-586d5d0ca020)

One May morning, Lord Rodermere, out hunting with a party of friends, thought he saw in a thicket a vixen and set off after her until by twists and turns he became lost. He stopped and shouted out in the hope of one of his party hearing him. And all he saw and all he heard was the chanting melody of birds, quivering leaves, cooling winds, and shadows. The mocking echo of hounds and a distant horn confused his senses. A snake unseen slithered past and so startled his horse that it bolted, taking his lordship by surprise. It was all he could do to hold tight to the saddle and reins as his horse, wild-eyed, nostrils flaring, took flight. Low branches scratched his face and Lord Rodermere fought not to lose his ride.

He is conscious, perhaps for the first time, of how deep and far the forest stretches.

On and on they go, horse and rider, this way and that, he all torn and knocked about, unable to bring his horse under control for in the mind of the creature the snake follows faster than he can gallop. Into the darkness the horse takes his rider. He, too, wild with terror, for was that not the cry of a wolf? And all sight is lost and then it seems he has passed through some unseen curtain into blinding light. The ground beneath his horse is moss, soft moss, and from it rises an intoxicating perfume.

Lord Rodermere thinks to call out. He is rewarded not by the sound of the hunting horn but by a song that has such yearning at its heart that his horse becomes calm and he, enchanted, dismounts. Forgetting how he arrived here he follows the music which calls him on until he comes upon a clearing.

Through the trees, he spies a stream, and under a willow in the dappled light a maiden dressed in an apple blossom gown stands bare-footed in the shallow waters. He, all in wonder, lets his horse drink.

‘Maiden, do you know this forest well?’ he says. ‘Methinks I am lost.’

She takes no notice of him or his fine horse. She ripples the waters with her toes. Her silence intrigues him.

‘I am Rodermere,’ he says.

She glances up at him, her eyes as golden as the sun, her skin rose pink, her hair as black as midnight, her face an enchantment. She says not a word. She takes his hand and leads him into the stream.

‘No,’ he says, ‘my boots . . .’

And she lets go of him and walks out into the deep water where the stream whirls. Swimming away from him, her blossom gown floats free. The sight of her voluptuous nakedness, her loosened hair, flower filled, near undoes him. Disregarding his boots, his clothes, he wades out to her. But he is a cloven-footed lover whose grace lies in brutality. That, this sweet maiden does not allow and she casts him off.

Finding that his strength has no power over her, he follows her to the bank of the stream, desperate for his lust to be allayed, and there goes down on his knees and begs her to lie with him. She comes, puts her arms round his neck, kisses him softly on the lips.

If he had known anything of elfin ways he would have had the wisdom to climb fast upon his horse and ride free. For we are the stuff of dreams, void of time’s cruel passing. We are creatures of freedom that only brush against the world of envious man whose desires are made dirty with guilt.

It is one of the sorceress’s handmaids who now stands near-naked before him in all her ethereal perfection. Her strength will haunt him ere long he lives, the smell of her soft skin a perfume he will never forget or find again. She is what man wishes for in bed but freedom is her birthright: she will not be tied to hearth or home. She is mother, good, bad all in one and none is she. A friend, no friend of man be she.

The Earl of Rodermere is now tamed, unclothed, brought to his knees, and hers to do with as she will. No man has loved a faerie and lived whole to tell the tale. But such is the pleasure she gives him that long afternoon that there he stays in her arms, honey from her breast he drinks and all time lost.

The hunting party searched all that afternoon and into the evening until, exhausted, they returned home without Lord Rodermere. The next morning they went again to look for him. For a week the search continued but there was no sign of him. The parson prayed in the chapel for his master’s swift return. The following Sunday, the earl’s horse came home without its rider. Gradually, as the days become weeks and the weeks turned into months, the mystery of Lord Rodermere’s vanishing deepened. Those who lived near the great forest knew well he was not the first to be elfin taken.

Only his wife, Eleanor, Lady Rodermere, and his little daughter, Lady Clare Thursby, kept their hopes to themselves and their prayers tight on their lips for both wife and daughter prayed – prayed as they had never done before – that Francis Thursby, Earl of Rodermere, might not be found.

Wife and daughter dared to believe that their prayers had been answered. It had been a harsh winter when even the birds had fallen from the sky, frozen by the cold. Surely, Lady Rodermere told herself, no one could survive in the forest in such unforgiving weather.

VI (#ulink_854b54f5-365b-5c97-b64b-2f12e54bf66e)

Nine months have passed. It is midnight in the House of the Three Turrets. A servant sleepily attends to the fires before returning to his trundle bed. The cat, all whiskers and claws, sits watching the space behind the cupboard in hope of a mouse. The flea sucks on the sweet flesh of dreamers till he is ready to burst with blood. The distant church bells ring the hour. The dogs in the hall begin to bark.

Yes, this is the hour that will alter all the hours to come.

VII (#ulink_8cb299c4-cd57-5c44-98a4-2cb8e6a91f1b)

The infant was brought to the sorceress at one of the clock, one minute after his birth, more beautiful than even she had imagined. There was no kiss upon his brow, no faerie wish to interfere with her curse, or so she supposed, for who would dare disobey her? So certain was she of her powers that she did not examine the babe – perhaps his beauty beguiled her but she took the word of his mother when she said she had not kissed the boy, that he was innocent of any wish.

What is done is done and one kiss would not have the power to interfere with the sorceress’s magic. But she had no notion of what a mother’s love in all its sticky gore was like. Only later did she discover that the faerie had lied and the sorceress was aggrieved that she had ever trusted her womb-ridden words.

Her task that morn was to make sure that Lady Rodermere took this infant as her own, to love and to cherish.

She placed the basket with the babe in it on the steps leading up to the great front door of the House of the Three Turrets. The dogs howled but the household did not stir; it was asleep, deep under her spell. She required only two people to be awake: Master Gilbert Goodwin, Lord Rodermere’s trusted steward, and Lady Rodermere, Lord Rodermere’s trusted wife.

Lady Eleanor was lying in her great bed, listening to the dogs. She watched the door and held her breath, every sinew in her body stretched to breaking. She stayed that way, suspended between sleep and wakefulness, taking short, sharp breaths until she could tentatively assure herself that there was no tightening of the air, no drowning of hope, no weighted foot upon the stair. Her husband had not returned. She lay back on the linen sheets, relished the chilly space around her, the warm island her body had made in the centre of that vast cold bed.

Lady Eleanor, unlike her lord, believes in the Queen of Elfame. She is certain that her husband has been faerie-taken and she prays that he might never be returned to the shores of her bed.

Through the large bottle-glass panes of the window a beam of moonlight falls accusingly on the carved wooden cradle. It has been in this chamber ever since Eleanor first wed Francis, Lord Rodermere. Three daughters born, one still lives. Over the years the cradle has come to represent her failure to produce a son, an heir for his vast estate. Tomorrow, she thinks, she will have it removed.

Her bravery wavers, for the dogs have not ceased their howling. She rises, puts on her fur-lined gown over her underdress, her feet bare on the chill oak floor, as cold as the fear in her heart.

Please do not send his lordship back, please do not.

Taking a candle, she opens her chamber door, listening for distant voices in that cavernous House of the Three Turrets. There are none. For a moment she wonders whether she should call for Agnes, her maid. Eleanor has always loathed the black whalebone beams of the long gallery, full as it is of oaken shadows. Hearing Agnes’s peaceful snores from the adjoining chamber, she thinks better of it.

At the main staircase Eleanor stops and looks over the banisters. The dogs are now whining; why, she cannot fathom. Only her husband’s steward is there. What could be the reason for the hounds to be so disturbed? She watches Master Goodwin. He is holding a basket, staring at its contents with a puzzled expression. Snow dusts his doublet and cakes his boots. The glow from the fire catches his face. A face to be relied on, she thinks, and in that moment she sees him for the first time, as if she had never noticed him before. Kind eyes, generous lips unlike her husband’s mean, hard slit of a mouth. She wonders what those lips might feel like if they were to kiss hers. One thought stitches itself into another forbidden thought and she finds herself imagining Gilbert Goodwin being a gentle lover . . . and in that instant she knows what she wants, what she longs for: to be loved without leaden cruelty.

So the sorceress’s magic begins to work, for tell me how does a cuckoo lay her egg in a magpie’s nest if not with the help of nature’s charms?

Lord Rodermere had never considered his wife to be a handsome woman but that night Eleanor is not without beauty – a slight frame, delicate. Her hair is tumbled, sleep has given her a soft glow. As she walks slowly down the grand staircase, holding on to the balustrade, her gown falls open. The outline of her body, her breasts, show through the muslin underdress.

Gilbert Goodwin is suddenly aware of her and sees, not the wife of his lord and master, but someone vulnerable, lost; finds himself moved by the very image of her.

Eleanor and, she suspects, Gilbert Goodwin, knows there is another, invisible, presence watching them. This house of whispering oak seems always to be calling the forest closer, admitting its spirits.

‘What is it?’ she says.

Gilbert holds out the basket to her.

Her sad brown eyes take in the infant, fast asleep in the wicker basket, wrapped only in rabbit fur.

‘Is it faerie born?’ she asks.

‘I do not know, my lady,’ says Gilbert.

He does not think it an unwise question.

The babe lifts one small, perfect hand, nails as delicate as sea shells. She touches his finger and feels her heart being pulled towards the infant’s, knotted round his.

‘Have you ever seen such a beautiful child?’ she says.

‘No, my lady. There is a note.’

Pinned to the fur, written in the unmistakable hand of Francis, Earl of Rodermere, it reads, This is my son.

VIII (#ulink_9330131a-379d-52ce-a229-d03672d48244)

Later that St Valentine’s Day, when the snow had settled thick and white, covering the truth of earth and the lies of lovers, Eleanor wondered who it was who had entered the house that bitter winter morn, who it was who had been intent upon mischief. In the quiet of that afternoon, as the sun once more began to fail and the snow fluttered at the window, she shuddered with the joy of remembering and felt not one ounce of guilt.

Gilbert, Eleanor at his side, had carried the basket up the stairs, through the long gallery to her chamber. Neither of them had said a word, nor had the infant announced its arrival. Gilbert closed the door and they waited, hoping that none of the servants had heard or seen them.

She whispered, ‘My maid is asleep in there,’ and Gilbert Goodwin silently closed the door to the antechamber.

Still the infant had not cried out.

At the end of the bed was a chest where Eleanor had kept the swaddling clothes and the sheepskin bedding that her babes had slept in when newly born. She took out what was needed and wrapped the babe in the long linen cloth before laying him in the cradle to sleep. His hand fought its way free to find his mouth.

‘You will be needing a wet nurse, my lady,’ said Gilbert.

‘Not yet awhile,’ she said and sat to rock the cradle, to think what she should do, how she would explain the child’s sudden appearance. Could she claim the baby as her own? True, when she was with child, she had been slight, had never grown to the size of a galleon in full sail.

Back and forth, back and forth, the cradle rocks back and forth and with each gentle movement she feels a strange heat. It starts in her thighs and spreads up into her belly, into her very womb, up to her breasts. It is an overwhelming heat, the like of which she had never experienced before. She stands up abruptly and forgetting all about Gilbert, forgetting all about modesty, she throws off her fur-lined gown. Still her womb feels to be a cauldron of flame. She discards her underdress.

‘I am on fire,’ she says.

Gilbert sees her naked, her arms wide open and turns his face away.

‘My lady, shall I call for Agnes?’

She looks at him and he turns to her, his full lips parted. She leans forward, her lips touch his. It is kindling for the blaze.

Frantically, she undoes his doublet. He pulls off his shirt, her hand slips into his breeches, she is pleased to feel his cock is hard. On the bed he parts her tender limbs, kisses her lips, her neck. He nuzzles her breasts and gently enters her, not with the violence she is used to, nor is the act over with the pain of a few uncaring thrusts.

Gilbert whispers, ‘Slowly, my lady, slowly.’

He takes his time, waits for her. At each stile the lovers encounter he helps her over, and deeper into her he goes. Then, at the height of their ardour, when all appears lost, Eleanor gives a cry that wakes the baby, that makes the lovers pull away, she embarrassed by the completion of an act that she never knew could be so tender.

Gilbert climbs out of bed, picks up the infant and holds it to him. They wait for the knock on the door, for their sin to be discovered.

But there is not a sound, the house is still wrapped in an enchanting spell. The sorceress would not allow these two lovers to be disturbed. More needs to happen before the cuckoo is well and truly hatched.

IX (#ulink_7ef52618-5c65-5fb8-a0bb-fca2a9388860)

Eleanor looks at Gilbert, naked, holding the infant close to him and her breasts ache. They feel full, painfully full, just as when she’d had her own babes. Leaking milk, she takes the babe from Gilbert and begins to feed him. With each thirsting suck he assures his place in her affections. She looks up at her new lover.

‘Tell me what has happened to us – do you know?’

Tears fill his eyes.

When the infant had finished feeding, Eleanor searched hungrily for a mark upon him for she had no doubt that her husband had been faerie-taken, no doubt that this was his child.

The infant fell asleep and Gilbert wrapped him warm and snug and laid him in the cradle. And as he did so, the steward felt that time had gathered itself in quick, aching heartbeats, each beat becoming a month, the months becoming nine. This faerie child was as much his and his mistress’s – born in a flame of a desire – as ever it was his master’s.

Gilbert awoke only when there was a tear of light in night’s icy cloth. Eleanor had the babe at her breast once more.

She reached out towards her lover and whispered softly, ‘I will not give up the child. He is ours. What will we say? What should we do?’

Gilbert kissed her.

‘Leave that to me,’ he said.

In a basket near the bed lay a heap of bloodied sheets. Blood spilt on the floor, jugs of water, pink in colour, clothes and all such stuff to dress a stage for a woman who had given birth.

When Agnes finally stirred she was confused first by how late the hour was, then mystified at the sight of her mistress propped up on pillows with a newborn babe.

‘Oh, my lady,’ said Agnes, ‘why did you not wake me?’

‘I tried,’ said Lady Rodermere, ‘but you were fast asleep and it came so quick upon me.’

‘Was no one with you, my lady?’

Not a beat did Eleanor miss.

‘Yes – Gilbert Goodwin.’

After all it was the steward’s duty to make sure that any child born to Lord Rodermere’s wife was no usurper.

‘I am most truly sorry,’ said Agnes. ‘The thought of you being on your own, and you never knowing you were with child.’

Eleanor felt the smile deep within her and kept her face solemn as she said, ‘If asked, perhaps it would be best that you were to say you were with me all night.’

‘Willingly,’ Agnes said.

And by doing so is caught in the nest of lies.

X (#ulink_fea6f34e-3ce1-5d51-9b13-f240287f6432)

It was Gilbert Goodwin who after the infant’s birth sent for the Widow Bott. The widow had delivered many a changeling child and watched them fade as bluebells in a wood when the season has passed. For the truth is, there are few children who have a mortal and a faerie for a parent and those that are born always have a longing to return to our world rather than stay in the human realm, and who can blame them. Changeling children, instead of being plump and round are sickly things that hang on to life as does a spider swing on a thread in a tempest. These changeling babes, left behind unwanted by the goblins, are placed in cradles where newborn babes lie and when no one is looking they take the child’s form as their own. But not this half-elfin child. He was born to be the sorceress’s instrument of death.

Lord Rodermere had often decried faeries as diminutive creatures made of air and imagination. But we are giants for we hold sway over the superstitions of humankind. I have hunted the skies, chased the clouds in my chariot, I have seen wisdom in the eye of a snake, strength beyond its size in an ant, and cruelty in the hand of man. Our sizes, our shapes, our very natures are beyond the comprehension of most. We are concerned with pleasure and the joy of love, we use our powers to shift our shapes, to build enchanted dwellings, to fashion magic objects and to take dire revenge on mortals who offend us. But for those we protect, such as the Widow Bott, we ensure their youth and health.

She has a far greater understanding in the knowledge of herbs and plants and their properties than many an apothecary, much more than the quack wizard, or so called alchemist, hoping to turn lead to gold, to cheat men from their money.

So it was important – nay, I would say it was a necessity – that Gilbert called for her, for she alone could sway all incredulity, she could assure any doubters that the sheets held the evidence of a human birth, not the blood of a slaughtered rabbit. In short, she would give weight to the child’s arrival, confirm that he was indeed the son of Francis Thursby, Earl of Rodermere.

XI (#ulink_8f104a8c-be0f-5ff5-8245-a7f0e3441091)

The sorceress had no desire to remain at the House of the Three Turrets that morning. It pained her to see her trees used that way, their branches bent, carved into unforgiving shapes. Instead she went to the widow’s cottage and waited by the fire.

It was dark by the time the Widow Bott returned. Wrapped against the cold, her cloak caked in frost, snow and she came in as one. Putting down her basket, she fumbled for a candle to light. The sorceress lit it for her, set the fire to blaze and the pot upon it.

‘I should have known that you would be here,’ said the Widow Bott. ‘Well, I am not talking to the air. Show yourself, or be gone. I am tired and it shivers me when I cannot see you for who you are.’

For some reason she was out of sorts.

‘You always know when I am near,’ said the sorceress, to comfort her.

‘Tis a pity that a few more folk are not as wise as me to your ways,’ said the widow, dusting the snow from the hem of her dress and taking a chair by the fire. ‘What mischief have you been up to?’

The sorceress laughed. ‘So you saw the child?’

‘Yes. He is more beautiful than any mortal babe should ever be. He has already won the heart of Lady Eleanor.’

The sorceress seated herself opposite the widow. ‘You should be in better spirits,’ she said.

‘And what of Gilbert Goodwin?’ asked the widow.

‘What of him?’

‘Never has a man been more lovestruck.’

‘And Lady Eleanor?’

‘The same. Do you intend to return Lord Rodermere? For he is not missed at all, especially not by his wife who trembles at his very name.’ The widow stood, took a long clay pipe from a jug that sat on the mantelpiece and kicked a log with the heel of her boot, before sitting down again in her rocking chair. ‘You have made a mistake if you think Lord Rodermere is of any importance.’

‘He has dented my forest.’

‘Will you put a curse on every man who fells a tree?’ snapped the widow. ‘Perhaps it would have been best if you had travelled further than the forest and seen what is abroad before you laid your curse, for there are many roads that lead now to the city and news travels both ways upon the Queen’s highway.’

‘Tell me,’ the sorceress said, ignoring her jibe. ‘Did you examine the infant?’

‘Lady Eleanor would not let me hold of the babe. She seems as devoted to it as if it was hers and she has no need of a wet nurse. Though she did ask about the star that be on his thigh.’

The sorceress stood. ‘What star? The child was blemish free. Did you see it?’

‘No, for the infant was swaddled.’

‘She is mistaken.’

‘I think not,’ said the Widow Bott.

‘What did you tell her?’

‘That such a mark . . .’

‘Such a mark,’ the sorceress interrupted, ‘was not upon the child.’

The widow never once had been frightened of the sorceress. She shrugged her shoulders.

‘I have no need to argue with you,’ she said. ‘If you say there is no star then what I say means little.’

‘What did you say to Lady Eleanor?’

‘That such a mark shows him to be of faerie blood and the star, a gift. She asked what kind of gift and I told her that only his mother could answer that question. She blushed when she realised that she had unwittingly confessed that the child be not hers, milk or no milk. She begged me never to say a word. She showed me the note left pinned to a fur and I assured her that her secret was safe.’

‘Good, good. But there is no mark.’

‘If you say so,’ said the widow. ‘But Lady Eleanor knows more of your ways than her husband did. She asked if the babe be a hollow child for she has heard of women who give birth to changelings and having no appetite for life, they mock a mother’s love and fade away. I promised her this be no such child. Was I right?’

‘Yes. Yes,’ the sorceress said again and all the while the thought of the star worried her.

‘You should not toy with us as if we be puppets,’ said the widow.

‘Come, that is unfair – I do not.’

‘But you do. Look how many lives will be changed by your curse. You would be wise to leave it be, not have Lord Rodermere return to plague his wife, to accuse me again of being a witch. Let the good of his disappearance be your comfort.’

‘No, what is done is done and cannot be undone.’

The sorceress watched the Widow Bott as she relit her pipe.

‘So you know how all this will play out? How Lord Rodermere will meet his end?’

These questions annoyed the sorceress.

‘My curse will come to pass. What befalls the players on the way has little to do with me.’

‘I think you are mistaken. You are dealing with our lives.’

The Widow Bott pulled at the sorceress. But no one talks that way to her and she turned to leave.

‘Wait,’ said the widow. ‘Wait. You know there is a reward for anyone with information about Lord Rodermere that would lead to his safe recovery?’

‘They will never find him – of that I have no worry.’

‘You may have no worry, but I do. They may never find him unless you will it but what you have done this day will bring to leaf a tree of questions that fools and mountebanks will try to answer, their brains baited by the riddle of the boy’s unholy beauty. I will be marshalled and again accused of witchcraft. The monks feared nature’s beauty, seeing it as a seducer, a tormenter of men. Even in the soft petals of the rose, they thought they saw the face of evil. Do you believe this child will go unnoticed, that his very looks will not be brought into question? How far do you suppose the news of his birth has already travelled?’

The sorceress said, ‘Your word is enough, I am sure, to confirm that the child is the son of Francis Thursby, Earl of Rodermere. No one will question his parentage.’

‘Again, you are mistaken.’

The sorceress had no interest in this. What concerned her was the star.

‘Keep yourself to yourself, widow,’ she said, ‘and you will be safe.’

‘Perhaps. But for how long?’

‘Near seventeen years,’ said the sorceress.

She was in no mood to contemplate consequences and as she lifted the latch on the door, she congratulated herself that her powers had not waned.

XII (#ulink_88fb5d97-7e08-5443-a58c-3a039f8bbe86)

The sorceress returns to her dwelling deep under her angel oak, whose veiny tendrils weave the domed roof of her chamber. Here stands her bed – raven black, the colour of dreams – with its canopy of stars. Fireflies light the room and gather, as do the moths, round one golden orb, a heavy pendant that swings slow across the chamber. She sleeps suspended between the streams of ages. Her spirit barely stirs to hear minutes passing. It is a parcel of time put to good use.

A moth’s wing flutters and almost seventeen years are gone.

XIII (#ulink_7d999d35-19f1-5aee-84a7-2a4eeb2d7414)

Something gnaws at the edges of sleep. Not the rhythm of the days but her passion for Herkain, the King of the Beasts. It is not wise, she knows, to let herself visit him even in dreams for it brings her to the well of her own emptiness. He who had the sorceress’s very heart where all her love lay, who sunk his glorious teeth into its arteries, pulled it beating from her breast, left her heartless. He did not take her power, only her reason. She conjures the memory of Herkain’s tongue licking the flesh from her to reveal her pelt in all its lush resplendence. Once, she longed to return to him, ached to feel his prick deep inside her, to feel his strength contain her, the howl of his whole being released into hers. When they lay together they were one, she his dark, he her light.

Memory can disturb even the deepest sleeper with its incessant chimes upon the mind. Does the sorceress deceive herself when she dreams again of Herkain? Or is it the infant’s beauty that so enchants her that she cannot rest until she has the measure of the boy, knows what kind of fiend she has created?

Though he be half of faerie blood, all of him will be his father’s child. His beauty will corrupt him and the years will make a monster of the man.

And she wakes. By the lantern light she sees that the hem of her petticoat is torn, a scrap of the precious fabric gone, her very inner sanctum violated.

A tear in her petticoat is an unbearable weakness. It wounds her as if it is her flesh that is peeled from her for that piece of fabric is a charm that would give the thief power over her.

Who would do such a thing? No mealy mouthed mortal could part the watery curtain that divides the world of man from faerie. No spirit would dare come near her. Was this Herkain’s mischief? No, no, it was not he, of that she is certain. Then who?

Such was her fury, such was her malice, that she howled with the pain of it. And her faithful trees stayed silent and gave no clue as to who the thief might be. Her rage was uncontainable, she rocked the earth with it and heard winter shiver.

The sorceress dressed to hide the tear and against the season of snows she wore a gown made of summer gold, sewn with the silk of spiders’ threads, embroidered with beads of morning dew. Its rubies ladybirds, its diamonds fireflies, hemmed with moonshine’s watery beams; yet it was the tear in the hem of her petticoat that weighed her down for some mortal held its threads and by such stitchery, she was tied to them. She smelled blood, she smelled the shit and the fear of mortals.

She hardly noticed the cold or winter’s white mantle. Rage kept her warm and fury brought on a blizzard. Only in the icy breeze did her balance return to her. All was frozen, held tight against nature’s cruelties.

The Widow Bott, she will know. She will know who committed this crime.

She reached the clearing where the widow’s cottage stood. A papery yellow light glinted through the slatted windows. The wind whirled the snow as she knocked on the door.

‘Who is it?’ said a voice.

‘You know it is I.’

The widow unbolted the door that had never before been locked for she had no one to fear, not even the black wolf. She was wrapped as tight as her cottage, her clothes quilted against the cold. The fire flared in the draught of the open door and she closed it quickly, and moved to her chair.

‘So, mistress, you come at last,’ she said.

‘I told you it would be near seventeen years,’ said the sorceress, ‘and true to my word I am here. What is wrong, old widow?’

The widow’s hollow eyes as good as told her that something was amiss. She took the chair opposite her and the widow turned her face away. Where, thought the sorceress, was the widow’s bright, piercing stare that dangled challenge in its light?

She thought to ask a simple question.

‘The babe – what did Lady Rodermere call him?’

‘He is called Lord Beaumont Thursby, but all that know him call him Beau.’

‘He is now near grown, is he not? Ruined by the knowledge of his beauty and its power?’

‘If that was your design then you will be disappointed. He has grown to be the sweetest of young men. If his beauty has any consequence it is to those who look upon him for, man or woman, it makes no difference, all are enchanted by him.’

‘So, I am right,’ the sorceress persisted. ‘He uses his looks to make slaves of those who his beauty entraps.’

‘Again you are wrong.’

‘Impossible.’

The Widow Bott leaned forward and poked at the fire as if she had no desire to speak the truth.

‘His sister,’ continued the sorceress. ‘That toad-blemished creature: surely she is bitter with jealousy?’

‘Again, no. Powerful is the bond of affection between brother and sister. And tomorrow, their mother, Lady Rodermere, is to marry Gilbert Goodwin.’

‘But she is still married to Lord Rodermere, is she not?’

‘Not. The queen was petitioned to annul the marriage as Lord Rodermere has not been seen, alive or dead, for eighteen years come May. Please, mistress, I beg of you, let this be. Do not return Lord Rodermere to them.’

The sorceress looked at the widow more closely as she repacked her pipe and lit it, sucking in her sallow cheeks.

‘What are you not telling me?’

‘There is nothing to tell,’ she said.

She was lying, trying to hide her thoughts, the sorceress knew it. One name escaped the store cupboard of her mind. Sir Percival Hayes.

‘What are you frightened of?’ the sorceress asked. ‘Who is this man – this Sir Percival Hayes?’

The widow shivered. The sorceress caught her eye. ‘I am waiting,’ she said, ‘and I am not in the mood to be lied to.’

‘Sir Percival Hayes has an estate not far from here. Lady Eleanor is his cousin. When the earl vanished, Sir Percival went to the house and swore he would be found. He too had heard stories of people being elfin taken – it was a subject that much interested him. Cunning men and wizards made a path to the door of the House of the Three Turrets, promising that they had the charm, knew the spell that would release Lord Rodermere from the faerie realm. Two years of fools came and went, and for all their enquiries—’

‘Yes, yes,’ the sorceress interrupted. ‘Nothing was discovered.’

‘Mistress, let me tell this in my way.’

At last a spark of the woman she remembered.

‘After two years had passed, Sir Percival sent from London his own alchemist, Master Thomas Finglas.’

The old widow was silent awhile and then said, ‘He brought with him his apprentice, a lad whose skin was as dark as an acorn. They made a strange pair, the boy and the man. The alchemist, I was told, handed Gilbert Goodwin a letter from Sir Percival who wrote that Master Finglas was tasked to bring back Lord Rodermere from the faerie realm. You may well imagine that Master Goodwin was none too eager to welcome this guest. Near two years had passed, two years of managing his master’s estate, of loving his master’s wife, of sleeping in his master’s bed. The last thing he wanted was his master’s return.’ ‘The quest failed,’ said the sorceress. ‘The alchemist – you met him?’

The widow nodded.

‘What sort of trickster was he? Soaked in books, steeped in knowledge, lacking in wisdom?’

The widow looked her straight in the eye. ‘If you know all, why did you never come when I called for you?’ She gazed into the embers of the fire and said, ‘Master Finglas failed to find Lord Rodermere and his failure to do so turned Sir Percival Hayes against all such alchemy. He had me examined for witchcraft. He said there be reports of me dancing with the black wolf, he even accused me of casting an owl-hunting enchantment on Lord Rodermere. He said I worked with a familiar.’

‘What led him to think this?’

‘I know not. Sir Percival sent his steward here this Yuletide to collect proofs against me: cheese that would not curdle, butter that would not come, the ale that drew flat.’

The sorceress laughed. ‘As if we would be bothered with such domesticity.’

‘There is more,’ she said. ‘I be accused of bewitching Lady Rodermere’s maid, Agnes Dawse, and by doing so cause her death. But I did nothing, nothing. I never even saw her when she was ill.’

Sleep had made the sorceress slow. She should have known from the moment the widow opened the door that the spell that kept her safe was broken and age had taken its revenge. She had cast herself from the sorceress by the folly of her tongue. The sorceress should have been more circumspect. The tear in her dress was a weakness that pulled her imperceptibly into the mortal world. Time is the giver and time the thief.

‘You betrayed me, old widow. You spoke my name.’

Her fury rumbled the rafters of the cottage and she was in a mind to bring it down on the old widow and let it be her tomb.

‘Do you not care what happens to me?’ said the Widow Bott. ‘Be it of no importance to you?’

‘Some may think that a tear in their petticoat is of no importance.’ The sorceress showed her where the cloth had been taken. ‘If you can tell me where I might find the missing piece, I could be kind to you still.’

The widow peered at the hem and felt the fabric between her fingers. Snow thudded to the floor from a hole in the thatch.

‘I think I saw it – but I cannot be certain.’

Then the sorceress caught it – a fleck of a secret in the widow’s eye.

‘Be warned, old widow,’ said the sorceress, her anger a blood-red moon, ‘for I speak willow words that, if I so desire, can snatch your soul away, turn your good fortune to bad and bad to evil. My magic is eternal. What is it you are keeping from me?’

The widow shivered.

‘A scrap of your hem. He had it. The alchemist had it.’

Blinded by rage at what she had heard, such was her impatience to be gone that in all the Widow Bott had said the sorceress had missed the details. The truth, as tiny as spring flowers, lay unnoticeable beneath the snow.

XIV (#ulink_edcab741-7309-5266-b94d-a3ab0146083f)

That night, this night, midnight, the end of Christmastide. Father Thames has begun to freeze, so tight is winter’s grip. Silent, soft, canny snow begins to fall; thick is each determined flake that gathers unrelenting in its purpose to make white this plague-ridden, shit-filled city.

On such a night in Southwark, the bastard side of the Thames, by the sign of the Unicorn where the houses bow towards one another, their spidery beams made solid with salacious gossip. There the torches that would have lent light to the street have long been defeated, but one paltry candle burns in the cellar window of the house of the alchemist, Thomas Finglas. A vixen trots up the narrow alleyway, her soft pads leaving paw prints that are soon to vanish in a layer of crisp snow. She sniffs the night air and sees at the bars of the cellar window a creature, not of human shape. For a moment their eyes meet. Then, with a nod, the fox sets off once more, her brush proud behind her, her breath licked with flames. At the back door, the sorceress hesitates and listens. From the cellar comes an unearthly cry.

Herkain’s long-ago words return to her unheeded.

‘Pride, my love, is the Mistress of Misrule.’

Pride? she thinks. No, it is not pride that brings me here, unless pride be the essence of my being. She is here to retrieve what is rightfully hers, a piece of her hem, perilous, too powerful to be taken by a mere mortal.

Unseen, a ghost, she steps into the house and as she enters the threads from the stolen hem needle into her, pull her towards this unknown thief. Quite suddenly she feels her powers wane, her magic weaken. Surely it is impossible that a man could possess wizardry equal to her own?

Not a sound do her feet make on the stairs and there, in a tattered, long-neglected chamber, the alchemist lies on his lumpy mattress. The sorceress can hear his thoughts as she can with most mortals. In the flicker of troublesome dreams he notes the bluish light, the bitter cold, and longs for a peaceful sleep to rob him of all conscious thought. He thinks the cause of so much waking is a dry brain and his continual fears, he believes, account for his lack of sleep.

But it is the memory of his late wife, deep buried, that is the cause. He had hoped with her death would go all the bell, book and candle curses that had tortured his days, made barren his nights. Half asleep he stares up at the canopy of the bed. His disquiet mind frets at the shabby drapes until in the fabric he sees the face of his dead wife, hears her voice crab-clawing at him.

‘Nay, Husband. I would call you a murderer.’

And into the covers of his bed, he mumbles, ‘It was your curiosity that killed you, woman, not me.’

Her cackle was as thick as his blood and just as black. ‘Suspicion will always fall on you, husband. I made sure of it – a gift from my winding sheet. I might be dead and maggoty-eaten but the power of my mischievous tongue has outlived me, has it not, Husband?’

Thomas sits bolt upright in bed. He is a thin man, his eyes hooded by anxiety. He has lost the optimism that had once given him an arrogance that marked him out, as if he alone knew the answer to all the world’s conundrums. His mind is kept sharp with knowledge yet his wits are dulled by superstition and a terror of the power he has unleashed.

This dead wife of his is an indigestible piece of gristle. Her bitter words sit heavy on the right side of his stomach, a pain no remedy of his devising can ease. A cold wind moans into the chamber through the gaps in the glass. He hears the vengeful night conquering the current of the Thames, transforming water into ice. He hears with a heavy heart his late wife’s waspish voice prattle on.

‘I would call you an adulterer, a dealer in the Devil’s magic.’

He sinks back and pulls the covers up over him.

‘And you,’ says Thomas Finglas, ‘what brought you to our table apart from rumours and lies to make misery of my tomorrows? Never once an infant came from that barren womb of yours to comfort my days. Be damned, be gone.’

He thinks back to his mistress, his beloved Bess, her flesh so soft, her breasts so firm, her belly round. Her belly round that had given him his one and only infant, a secret to be protected from this cruel world and from his wife’s vicious temper.

‘You never knew the truth, woman,’ he says into the hollow silence.

The sorceress is intrigued.

‘Tell me, Thomas,’ she says. ‘Tell me the truth.’

‘Bess . . . is that you? Bess . . .’

Sleep takes him, exhausted, in its kind embrace. And just as he dreams of Bess’s round bottom, her soft cheek, just as he feels her lips upon his, downstairs something heavy falls.

‘The cat,’ says Thomas sleepily.

He cares little, for only Beelzebub now will make him rise from this floating warmth of oblivion, from the tender-breasted Bess. All else can go to the Devil.

‘The cat,’ he says again, his eyes heavy, his mind at last clear of the past.

But it is no cat.

XV (#ulink_8221e1ef-ce77-5e70-ae5e-edd6f43b21a1)

There are two men in the house, heavy of build but nimble of foot, the stench of the river and the tavern on them, mercenaries in search of any paid work. Kidnapping, assault, murder, all arts they are well-versed in as long as they are paid and can own their own boots. Each step they take in hope of waylaying their prey.

Thomas’s apprentice, John Butter, does not wake at the sound of the intruders. He is asleep in the kitchen. He, unlike his master, sleeps the deep sleep of youth. Walls may crash, trees may fall and still he would dream on.

Thomas wakes with a start. He tries to gather his dreaming wits and fails.

‘Bess?’ he calls into the darkness. ‘In the name of God, show yourself.’

Swift are the two men. He has no chance to scream before he is muffled in a cloak, wrapped and strapped.

His two assailants are big-built, battle-dented men. Thomas is an easy customer. The knife held to his side tells him they mean business.

‘Keep quiet and no harm will come to you. Make a sound and the knife will find its home in your heart.’

He is bundled from the chamber. The vixen slips out unseen before them.

The garden gate creaks back and forth in the wind. Thomas struggles to free his face from the cloak, shaking his head vigorously. From the low window of his cellar comes the high-pitched yowl and the vixen sees there again the feathered creature who stares out through the bars, eyes glinting; a halo of light outlines its shape, talons scrape at the glass. The image is disjointed by the round panes so there appears more than one and behind all a shadow of wings looms great. The sight seems to torture Thomas.

Under his breath he whispers, ‘In the name of God be secret and in all your doings be still.’

Momentarily, the sound stops his assailants.

‘What’s that?’ says one, lifting his lantern.

He points at the cellar window. The sound sends a shiver down their hardened spines. Not even in war, when the battle was over and men lay wounded and dying, had these two heard such a cry.

‘Let us be gone from this cursed place,’ says the other and pulls Thomas into the alleyway. And in that moment, not fully able to see his enemies, he tries to make a fight of it. His reward for his effort is a sharp blow to the head. He stumbles and loses consciousness.

The mercenaries take hold of an arm each and carry Thomas with all haste towards the river. If anyone had the gall to stop them they would say they were helping an old drunk home. But no one is about to see them and only their footsteps tell which way they are bound. By the water steps, not far from the Unicorn alehouse, they drag Thomas to where a barge is waiting. On board is a gentleman, dressed in black, his jerkin slashed through with red taffeta, a fur-lined cloak speaks of a wealthy master.

‘What is this?’ he says, seeing Thomas unconscious. ‘Is he alive? I am not taking a dead man to the House of the Three Turrets.’

‘He is not dead. He will recover soon enough. Now, where is the money?’

The knife glitters in the darkness. Neither party wants an argument. A purse of coins is handed over and Thomas is dragged into a curtained cabin.

The oarsmen push off and out into the slushy water towards the middle of the river where a ribbon of mercury is all that is left of the fast-flowing tide, for the Thames has by degrees begun to turn white. Behind the barge London Bridge looms monstrous high, and an army of buildings, a fortress to remind England’s enemies that this country is ruled by a queen with a lion’s heart.

When the river freezes it speaks; fragments of ice crackling with confessions of the murdered and the lost. On the ill-lit bridge the sorceress alone sees the frosted ghost of a young woman, a group of drunken men laughing, jostling her. She loses her footing and slips, tumbles unnoticed into the icy, churning waters. The voices of the dead bring an eerie sense of solitude to this usually frantic thoroughfare. Among them Thomas hears his Bess.

‘Not long, my love, ’til we embrace again. Not long, my love.’

The river is near deserted. The oarsmen battle on, sweating even in the cold of this grievous night. Slowly the city disappears, past Westminster and out into the pitchy black darkness of the countryside.

XVI (#ulink_4d57ef7a-f65b-5237-a426-cf105d740e3c)

But the sorceress cannot leave. Not now, not until she knows what it is that the alchemist has hidden in the cellar. Crude curiosity pulls at her and to the house she returns.

Still no one had stirred. Then she heard it, the frantic flapping of wings and scratching of talons, and she perceived a smell – pungent, musty, animal. Determined to see the creature she was at the cellar door when she heard a call.

‘Master, master – is that you?’

A young man stared at her and through her to where the back door had swung open letting in the raw cold. Dark of skin and dark of eye, this, then, is the alchemist’s apprentice. Unlike his master his thoughts were guarded and he kept them close to him. The sorceress found it hard to fathom what he was thinking other than the obvious. The footprints in the snow increased his fears. She followed him as he took the stairs, two at a time, to his master’s chamber, cursing under his breath. One glance at the disarray of the bed clothes, enough to tell him what had happened.

In the apprentice’s ebony eyes she saw the heat of the sun from an unknown world, the place from whence he was stolen. He knows better than his master the power of magic, knows it possesses a life force that not even death can defy. He survived the seas where the battle with the waves had been fought. The wooden boat, weighed down with the thief’s treasure, ill-equipped to deal with the fury of such a tempest, had been tossed as if it were a child’s plaything and, limping into port, had brought him to these cold, anaemic shores.

Again the sound from the cellar. It is a noise that she sees he dreads and it is louder, more urgent than ever before. As he runs down the stairs, his thoughts, the ones she catches, have an energy to them, his whole being is more alive than the alchemist’s. She listens hard. He hopes his master’s secret is not to be discovered, he knows he must calm the creature in the cellar. She is in the passage when she hears a creak on the stairs and a young maidservant appears.

‘Oh, lord,’ she says, ‘Master Butter, what has happened?’

Master Butter speaks with a stammer and he is careful not to trip over his words. He knows that his stammer is especially pronounced in the presence of a pretty girl. He does his best to sound commanding.

‘Go into the kitchen, Mary,’ he says. ‘Stay there until . . .’

To his surprise she looks at him in a direct manner that has little fear in it.

‘Do you want me to help you?’ she asks, following him to the small cellar door at end of the passage.

For one moment he thinks he might laugh, the notion is so ridiculous.

‘No,’ he says.

The sorceress can see that Mary is new to the household and that she has never before met anyone like Master Butter. The colour of his skin, darker than the beams of the house. His eyes are darker still. He is tall. He turns to look at her as he takes his master’s key. Her presence gives him courage.

‘Be still,’ he says into the darkness of the alchemist’s cellar.

He opens the door, turns to make sure Mary will not follow and in that instant the sorceress slides in before him.

XVII (#ulink_e01cb5c3-b328-5207-be73-cdfca6e34a45)

You are not from my realm, Thomas Finglas, and your magic confuses me. You confuse me, for I saw what it is that you keep locked in your cellar and she is not of this world. Did you steal her from Herkain’s realm? No, it is impossible for any mortal to pass through that watery curtain into the kingdom of the beasts and return alive to tell the tale for the flesh of man is the sweetest of all meats. There is something more worth knowing. Perhaps she was sold to you, this winged beast. She would not be the first – the unicorn, the griffin made the journey and survived. But no and no again. And methinks that if a ‘no’ was a brick then a wall I would build with them. You go against the wool of me and muddle my thoughts. How is this possible, what potions, what magic charm did you use to create her? Was it by the hem of my petticoat or have you stolen more from me?

A knot of human making pulled becomes more impossible to untangle and yet the sorceress, knowing all this and more, cannot let it be.

Who are you, Thomas Finglas? You who possess power enough to rob me of myself, to flood my mind with your narrative. Who are you? There is trickery here. By what means did you find my chamber? Was it with a knife you cut my petticoat or did you pull the fabric from me? And why did I feel nothing? The cloth is as good as my skin. The pain alone would have woken me and yet I was numb to you. How can that be? These questions enrage me. Never before have I not listened to my instinct. It has ruled me. In the depth of my ancient being my wisdom echoes loud: return to your chamber, sleep and dream. Let time take care of the curse, not you. Not you.

Her excuse is the beast. And so she follows the barge which looks to her eye as a black slug does that leaves a slime trail in the thin surface of ice and snow. She has no choice but to stay close to this Thomas Finglas for he holds the answer to the many questions that sit, crumbs upon her lips.

The alchemist was conscious by the time he was helped up the steps at the watergate of the House of the Three Turrets, his mind making a mosaic of his broken thoughts that the sorceress furiously pieced together to find an answer. There was none. Overriding everything was his simple anxiety to be home. Now she listened far more attentively to all that the moth of his memory brought to the light.

He thinks his apprentice will not know the right words to calm his child. The thought of her escaping into the streets fills him with dread. She will be hunted like an animal, torn apart. She is still only a child, he thinks. Only a child.

And the sorceress thinks, she is no child of this world.

XVIII (#ulink_86172155-5482-56e8-be23-d1019dcc9b20)

It was a bitter dawn and snow illuminated the grounds. The light made beard shapes of trimmed hedges and in the distance, looming large through unnatural angles of bush and wall, the three turrets rose, each spire impaling the sky’s tapestry. Surrounding all, the forest cast its shadows. The sorceress heard its familiar, deep, slow heartbeat. This was a place Thomas had never wanted to see again and he had a feeling – no, a surety – who it was who had sent for him and to know it made his bones cold as stone.