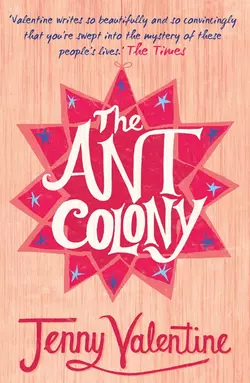

The Ant Colony

Jenny Valentine

An irresistible novel from Guardian-award-winning novelist, Jenny Valentine.Number 33 Georgiana Street houses many people and yet seems home to none. To runaway Sam it is a place to disappear. To Bohemia, it's just another blip between crises, as her mum ricochets off the latest boyfriend. Old Isobel acts like she owns the place, even though it actually belongs to Steve in the basement, who is always looking to squeeze in yet another tenant. Life there is a kind of ordered chaos. Like ants, they scurry about their business, crossing paths, following their own tracks, no questions asked.But it doesn't take much to upset the balance. Dig deep enough and you'll find that everyone has something to hide…

Copyright (#ulink_5ecd142d-b990-549a-a4f8-1ccab5abee95)

HarperCollins Children’s Books A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Jenny Valentine 2009

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2009

Jenny Valentine asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007283590

Ebook Edition © MAY 2012 ISBN: 9780007381012

Version: 2015-04-01

For Alex

(and Reg)

Contents

Cover Page (#u2d07413f-25f4-596c-95c8-607daeadd04c)

Title Page (#u325b7a17-e96c-5bed-96c1-e2e5c6b3b23e)

Copyright (#ufea1eb2a-f6a0-58e9-9906-10cc7953f328)

Dedication (#u0a9ce355-4842-5b21-9f3a-7a4fa30d2c4a)

One (Sam) (#u0eb578f3-3290-537b-9e01-73b1ee93c28f)

Two (Bohemia) (#ua53e87ef-ba93-5f51-88c9-578bd2fa9b08)

Three (Sam) (#u87737509-9288-5c62-b7de-6bcad658f259)

Four (Bohemia) (#uee9d887a-6a28-58b7-953e-85cfd510a33a)

Five (Sam) (#ue82ea7ef-6e74-565a-91eb-67f304bc0348)

The Story of My Life Part One by B Hoban (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of My Life Part Two by B Hoban (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of My Life Part Three by B Hoban (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of My Life Part Four by B Hoban (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-one (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-two (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-three (Sam) (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of My Life Part Five by B Hoban (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-four (Bohemia) (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Jenny Valentine (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (Sam) (#ulink_c20b1490-4c12-553e-ade7-00f5988e23d2)

I saw a girl. Just a kid. It’s not what happened first, but it’s a good place to start. I can see her now. She could be standing right in front of me. I wish she was. Dark red hair, cream white skin, eyes to the ground.

I was walking past and she was there in a doorway, an open doorway on to the street. Behind her was another door into the place, a bar I think, or a club maybe. And around her, between the two doorways, was just black, pure matt black. Her clothes were black, so her dark red hair and her pale face and hands were the only places of light.

She looked like she was appearing out of the night, sitting for a painter who’d been dead two hundred years. I’m not joking. There she was, in the rougher end of Camden High Street, looking like she belonged on the wall of the National Gallery.

I kept walking and I held her picture in my head, and I remember thinking, What if I went back and said hello? What if I told her how she looked, and how much I wished I had a camera and some idea of how to use it? I’d scare her, a big bloke like me. She’d think I was a freak. She’d move away and leave her place of perfect darkness and ruin the picture forever.

So I didn’t. I marked her down as one out of the eight hundred mental snapshots I’d taken that minute. It’s what you do in a place so crammed full of things to look at. Blink and keep moving. I’d been here less than one day, and even I’d been in London long enough to know that.

My name is Sam and I’m not from here.

I grew up in a house beneath a mountain, hidden in a dip that filled with snow in the winter, with water in the spring. Night time there was proper darkness, a total absence of light, apart from the stars which were infinite and spread just right to show you the curved shape of the sky.

There aren’t any stars in the city. I used to drag my mattress over to the window and lie on my back looking out at the damp blanket of orange that bounced off every available surface, at the flashing wings of aeroplanes.

The day I left home was like this: high sky, still air, shouting birds. I woke up and it was beautiful, and I hated the sight of it because there was no way I could stay. I forced myself to lie in bed until Dad had gone, staring at the sun through my window for so long that I could see it with my eyes shut.

I was sitting at my desk, dressed and ready to go when Mum banged on my door around eight. Three short raps. She made the distance beween us obvious even in the way she did that.

Afterwards I often wondered how things would have been different if she’d known I was leaving, if she’d have kept those feelings to herself just that once. But you can’t go around treating everyone like you might never see them again, just in case. And anyway, it was way too late by then. I already knew how she felt.

Missing the bus was way easier than catching it. I changed my school sweatshirt in the broken down barn at the end of our lane and stashed it in my bag. And then I hitched into town to catch the train. Aaron Hughes the old farmer picked me up – truck like the inside of a haystack, trousers held up with bailer twine, vicious Jack Russell on the passenger seat; that kind of old. He drove at about ten miles an hour, which is not exactly getaway speed. But he didn’t hear too well and he wasn’t bothered about talking, and I was glad about that. I wondered what he would do if he knew he was helping me escape.

The sky was this intense blue, palest at the bottom, dark around the edges. The surface of the hills shifted with the light, darkened with the shadows of high clouds. I was sick to death of all of it: the same curves, the same trees, the same beauty. But because I knew it was the last time, I stared like I’d never seen it before.

Aaron laughed. He said something about the land being like a woman, stunning when you leave her and grey and ordinary when you don’t.

We were quiet then. I didn’t know what to say to that.

The station was about a twenty minute walk from where he dropped me. People were waiting on the platform, saying goodbye to each other, huddling around cars. I didn’t see anyone I knew, thank God. I bought a ticket, crossed the iron bridge over the railway and sat there in the tunnelling wind on my own.

This is what I remember of the train journey. Identical twins. Women with shining scruffy black hair sleeping against each other two tables away. They were thin and tired, and they kept opening their eyes and not speaking, and then closing them again. Each of them was beautiful because there were two of her, like someone put a mirror down the middle of the train.

A group of kids behind me on their way to a maths marathon. They spoke so everyone could hear, like they were important, like nothing could touch them, like being good at maths was all you’d ever need to make sense of the world. I wanted to set them straight, but I knew they’d find out soon enough without me.

A little boy at the window of another train, crammed in, surrounded by arms, the sleeve of a quilted jacket squashed flat against the glass like someone pulling a face.

I took the sim card out of my phone, dropped it in a half empty paper teacup and gave it a stir. The woman opposite me stared without blinking while I did it and then went back to her magazine. I made sure I still had my money on me. I’d been taking some out of the bank every day. I kept checking it was there, all the time, because it was all I had.

The mountains shrank and the land flattened out, got boxed in and carved up. The view from the window was cramped and ordinary and fascinatingly strange. The twins woke up and looked out at it without saying a word.

I closed my eyes.

The first thing I learned about London was not to smile. I got off the train and looked around. The platform emptied like an organised stampede. I smiled at this man in a suit, darkskinned, middle-aged, clean-shaven. He was walking towards me. The shine on his shoes reflected the sky through the glass roof of the station. I smiled and it didn’t go down so well. He did three things, lightning quick, in less than a second. I watched him. He changed the rhythm of his walk ever so slightly. He looked hard at me, like steel, to make sure he wasn’t seeing things. Then he let his eyes cloud over, so he was still looking, but right through me, never at me. The one thing he definitely didn’t do was smile back. I learned pretty quick that the only people who smile at everyone in London are newcomers and the clinically insane.

Later, in the ticket hall at Paddington, I saw more people in one go than I’d seen in the whole of my life before. Thousands lining up for tickets and funnelling through turnstiles, going up escalators and coming down. I stood dead still at the eye of the storm, just one of me, and stared. I kept looking at this list I’d scribbled on the back of an envelope, like it might help. I couldn’t read my own writing.

Everyone else knew where to go and moved in swift, strong lines that picked me up and took me in the wrong direction, like the river at home after a night of rain.

I thought about Max then. He came back to me in the middle of all that sound and rhythm and colour and fumesmell and movement. He surprised me. I thought about walking behind him in the dappled darkness of the woods. I pictured his permanent frown, his sticking out ears, his chaotic hair. I thought about the nervous flicker of his smile.

It was all I could do to keep breathing.

You know when people say they wish the floor would open up and swallow them whole? Well, it’s pretty easily done, if you really mean it. I came out of Camden Town Station at twenty-nine minutes past four and vanished without a trace. Nobody knew who I was. I couldn’t stop smiling.

The sky was lower than I was used to. I went into a baker’s and bought a sandwich, and I couldn’t understand half of what the girl behind the counter said to me because she said it all so fast. I took too long counting out the right money and I could hear her foot tapping and she didn’t smile back, in fact she didn’t even look at me. The sandwich tasted of nothing and made me incredibly thirsty. I bought a Coke from a paper shop that you couldn’t fit more than two bodies in at one time. It was so crammed full of things to buy they forgot to leave room for people.

That’s what Camden looked like to me – it was the first thing I noticed. There was stuff for sale everywhere and I wondered who the hell would want to buy any of it.

I sat down on the wall of a bridge over the canal and finished my drink. I opened my bag and looked inside, for no reason at all. It was so loud. Layers of noise crowded and collided in my head, like sheep in a lorry, and made it hard to think. I walked all the way down one side of the street, into the yards, stopping for everything, studying everything, and then all the way back down the other. It was dirty, all greys instead of greens, like everything had a coat of dust on it. I felt like I needed to wash my hands even though I’d hardly touched anything.

I read about the dust on the London Underground once, that there’s tonnes of it every week and it’s mostly human skin. I hadn’t really believed it. But now I wondered if that was what was covering everything – pieces of all the people I’d already seen and all the people I hadn’t.

That’s when I saw the kid in the doorway, when I was walking up and down thinking about the dust. That’s when I filed her away in my memory box of people you don’t ever speak to. I was killing time because I had no idea what should happen next. It’s probably why I noticed her.

I went into a pub and had a pint. The man behind the bar didn’t look at me, didn’t ask how old I was. Nobody looked at me. It was like magic, like finding an invisible cloak.

It was the opposite of home.

It’s what I’d longed for, for weeks and weeks, to be the blind spot in a room, the black hole in the universe, to be absent without trying to at all.

I wanted to stay like that forever.

Later, I stood on the pavement outside the pub and tried to make sense of where I was. I remember pretending the road was a river, fed by other smaller roads like the streams that run off the hills, but thick with cars and bikes and buses instead of water. I remember thinking I’d had too much to drink.

Across the street a black plastic sign with pink writing said The Kyprianos Hotel. There was a fracture in the plastic and a round hole, like someone had thrown a tennis ball in there, or a rock. I had my hand around all the money in my pocket. I could afford it, I knew that, maybe not for long, but I suddenly needed to sleep.

I’d never stayed in a hotel before. It didn’t amount to much, apart from some soap in a box and a plastic shower cap, and a bathroom where you had to practically stand on the loo seat if you wanted to close the door. I didn’t close the door because there was nobody watching. I was completely and utterly on my own.

I almost regretted it then. I very nearly decided I’d done the wrong thing. But I swerved away from it at the last minute and kept my eyes on the road.

If only I’d learned to do that earlier.

I couldn’t sleep because there was too much going on outside the window – a whole orchestra of sirens and yelling and footsteps and door slams and engines. I wondered how anyone ever slept. I stared at a clamshell stain in one corner of the ceiling and thought about becoming someone new with nothing to be ashamed of, no past, just a future.

I thought about how weird it was, to be missing in one place while you’re right there in another.

Two (Bohemia) (#ulink_ec9e4cc4-8c56-5700-80e9-167e72de4840)

I was waiting for my mum. That’s what I was doing.

I was pressing patterns into a piece of old chewing gum with the bottom of my shoe. There were more than nineteen pieces of gum on the square of pavement outside the bar. I was counting them.

I wasn’t allowed in cos I’m underage. That’s why I was waiting outside in the black doorway in the freezing cold. She was in there for ages. Mr Thing and her weren’t friends any more, which meant she’d also lost her job and we had to leave the flat. Things happen that way a lot because Mum’s good at putting all of her eggs in one boyfriend.

We went so she could collect her wages and they had one more massive row while I stood outside counting spat out gum, trying not to listen. When she stormed out her mascara had slipped and the end of her nose was red, and she was halfway through a sentence about what a something he was.

When she saw me she rubbed her nose with the back of her hand and cracked a smile. She’s got nice teeth, my mum, all straight and small. Not like my mouth, which is still full of holes and frilly edges, even though I’m ten already. I hope I get teeth like her when I’m finished. I hope I hurry up.

“Let’s go,” Mum’s pretty teeth said. “Let’s spend some of his money, quick.”

She got me by the hand and we walked really fast across the road, and I thought she was saying stuff to me that I couldn’t hear.

“What?” I said, and she turned to me and I saw she had her mobile out already.

We packed before we went to see Mr Thing cos Mum’d been expecting it and she’d helped herself to a few extras out of his house, like towels and wine and stuff. We’d stashed our bags in a pub.

She phoned around and found a place, quick as a flash. She’s clever like that.

“Small apparently,” she said, and then licked her lips. “Like we could afford anything else”.

We lugged everything from the pub and stood outside the house with our suitcases. I looked at Mum, her big black glasses reflecting the sun, a little smudge of lipstick on her teeth when she smiled. I didn’t have time to point it out cos she rang a couple of bells and this lizard man in a pair of faded jeans appeared in the basement.

He stood there talking to her. I swear he was trying to see up her skirt. I tried to tell her, to pull her a bit out of the way, but she just said, “Not now!” sort of through her grin, so I glared at him instead. He was the landlord and I didn’t like him at first, smarmy old scale-face called Steve.

The corridor smelled funny, of cabbage and pot noodle and then something else like bleach with flowers in it. There was a big stack of old letters so the door couldn’t open all the way. Steve kicked it to one side with his cowboy boot and it fanned out over the floor. The carpet was the colour of a camel and looked like a camel had been eating it. He said it needed to be “refurbished” and when he said the word, he flowered his arms around like we might see it change before our very eyes, but we didn’t. There was a bike against the wall, with no front tyre and no saddle. It made me think of dinosaur bones in the desert. It was locked to the radiator with a big big chain.

“That’s Mick’s,” he said. “He lives below you. The rest of it is in his kitchen.”

We were on our way upstairs when an old lady came through the front door. It was only me that turned round to see. Her little dog started sniffing around all the envelopes and lifted its leg for a pee. It made me laugh, the sound of it landing. I didn’t tell. The old lady winked at me and tickled the dog and jingled her keys and went into her flat.

Our house was at the top. Steve carried one of Mum’s bags and she took one of mine. I dragged the other one up with two hands cos it was easier than lifting and it made this sound, scratch-thump, scratch-thump, on every step.

There was a loo, straight ahead, like as soon as you walked in, actually a bathroom, a kitchen to the left and a room with a sofa bed in it. I like sofa beds cos they’re a secret and you can have a bedroom any time you want, night or day. This one was a weird peachy colour that wasn’t so nice, but I didn’t mind cos it was bigger than our old one and it didn’t have such sharp corners.

“What do you think, Mum?” I said. “It’s all right, isn’t it?”

She frowned at me for calling her Mum in public and then she said to Steve, “We’ll take it.”

They shook hands and she did that laugh she does for boys only, which sounds like tiny stones landing on the high bit of a piano.

After she handed over the money and Steve handed over the key and left, she did a bit of ranting. That’s what I call it when she’s angry and she talks like she’s forgotten I’m there or I could be anyone, or something.

She said that maybe this was what Steve meant by “furnished” – one crap sofa, rubbish in the bins, not even a table, a couple of plates – but she could think of another name for it. She couldn’t believe how low she’d sunk. She said the place was filthy. She said, how did we know he wasn’t just re-letting to us while the people who really lived there were out at work?

“Huh!” she said, like a cross sort of laughing. “Imagine them coming home to you and me.”

While she ranted I did our Mary Poppins trick. I call it that cos there’s a bit I really like in the film where Mary has a bag made out of carpet and it’s full of stuff you’d never fit in a bag in real life, lamps and flowerpots and everything. My bag is a bit like that. Unpacking it never seems to end and there’s all sorts of stuff you can fling about until it feels more like home. Me and Mum’s favourite thing in that bag was a fold-up cardboard star with holes cut out. It was white when we got it and I painted it ages ago, when I was like six, and even though I didn’t do such a great job of it I never let her throw it away. It goes over the light bulb in your ceiling and makes everything look like a disco at Christmas. Except there wasn’t a light bulb, just an empty socket hanging, so I said I’d go to the shop and get one.

Mum was in the bathroom by then. I know what she does in there.

The street was way nicer than where Mr Thing lived, which was just flats and more flats and dark places I didn’t like being in by myself. For a start it was quiet, except for the cars whizzing across at the end. There was a garden on the other side of the road and a pub halfway down. The pub was covered in green tiles, like a bathroom. The houses were all the same and sort of elegant. I walked slowly, looking into all the windows. You can learn a lot about a place that way, about who lives there and the kind of stuff they keep. Like in some places there’s always books, more than you need really, and some houses look like they’re actually in a magazine, with the right flowers and everything. And some have net curtains older than me and Mum put together, and you can’t see in at all, but you can see they need washing and that nobody who lives in them ever goes out.

In our new street it was harder to see cos the bottom windows were under the pavement and the next windows up were too high. The basements mostly had leaves and bicycles and dustbins and broken chairs in, apart from one that had little trees cut to look like squirrels, but you couldn’t swing a cat down there.

Each house was cut up into so many flats you wondered where they put them. I read the little lit-up cards by the door on my way back in to ours and tried to work them out.

Basement was S Robbins, which was lizard-face Steve.

Flat one said Davy, the old lady with the peeing dog.

Flat two was water damaged, all brown and cloudy so I couldn’t read it.

Flat three said Flat three, which seemed pointless and was where the rest of the bike was.

Four was ours now, but it still said Fatnani.

The first thing I did, before the light bulb even, was cut a little piece of paper the right size off an envelope. I wrote CHERRY & BOHEMIA, drew some stars and fireworks, to put downstairs at the button for number four.

Cherry’s my mum’s name. I’m supposed to call it her now I’m ten cos the word MUM makes her feel old. Cherry loves it the times someone asks if we’re sisters. She knows they don’t mean it and they know she doesn’t believe them, but everyone plays along anyway. That’s what she told me. She said, “The men I hang out with are suckers.”

The time I like her best is some Sunday afternoons. We stay in our pyjamas, watch TV if we’ve got one, and eat what we want under a duvet. Some Sundays, she looks at me like she hasn’t seen me all week.

Steve the landlord lent us a broom and some bin bags and we cleaned up. Mum sprayed some perfume about so the whole flat smelled of her. When he came to get his stuff back, he asked Mum if she wanted to come out for a drink, just down the road at the pub that looked like a bathroom.

“You can come if you want, little lady,” he said to me. “Have a lemonade and a packet of crisps.”

Mum said I was all right here. She said, “You don’t mind do you, Bo, if I pop out?”

It was fine with me. I like being in a new place because there’s loads to do and look at and think about, and it takes longer than normal to mind being on your own. Mum gave me a pound for some chips if I got hungry and she said she wouldn’t be long. I put the money in my pocket and I made the sofa into a bed for later. I unpacked my clothes and made two really neat piles of them under the window. Then I played snake on Mum’s phone and made a few calls – not real ones because if she ran out of money I’d be in for it, and anyway, who would I speak to? I pretended to be like her when she’s on it, talking really quiet and biting her nails and saying things like “No way” and “ten minutes” and “you out tonight or what?”

Before she left I showed her the card I made for the front door. She liked it. She said she’d take it with her and put it by our bell. Maybe nobody would notice. But at least it showed we were alive in there.

Three (Sam) (#ulink_9f736e10-717a-5b44-8f28-0e3409da8e4e)

It happened faster than I’d thought, my new life getting started. First I found a job, stacking shelves in an all night sort of supermarket. I only went in for a carton of milk. From the shelves I stacked most, I’d say most people went in for SuperTenants and five-litre bottles of cider. The hours were strange and peopled with drunks. I kept my head down. Nobody asked me any awkward questions and they didn’t need any paperwork, and they were as content as I was not to bother being friends.

And I found somewhere to live.

My place at number 33 Georgiana Street was the third bell of five. All the other bells had a name on apart from mine, and no name suited me fine. I found it outside a newsagent’s on a notice board. A guy came out while I was standing there and stuck a postcard on with a pin. I watched him walk back in the shop before I read it.

I’d been throwing my money away at the hotel for nearly a week. I couldn’t afford it and I couldn’t go home. I didn’t want to be one of those people who moves to London and then ends up sleeping on the streets before they know it. The postcard said STUDIO FLAT. NICE VIEWS. CHEAP RENT. NO DSS. 2 MINS TUBE. DEPOSIT.

I phoned the number from a call box that stank so hard I had to keep the door open with my leg. I was standing at the end of my new road.

The landlord’s name was Steve. He lived in the basement. His skin was the exact dead texture of his leather jacket. He did the welcome tour, meaning the communal bathroom and the under-stairs cupboard where my meter was, and I couldn’t take my eyes off the folds and creases in his cheeks.

The electricity was pay as you go, same as the rent, which Steve kept telling me was way below the going rate, and which had to be cash in a brown envelope, I’m guessing so he could stuff it under his mattress and not tell anybody. I handed over half of everything I’d ever saved for the first month’s rent. The whole place was pretty trashed, but it felt so good to shut the door to my own room and stand with my back against it. It could have been exactly what I’d dreamed of doing with the money all along.

The place had a little kitchen and a bigger room for everything else, like eating and reading and sitting and thinking and sleeping. The floorboards were painted in thick black gloss with stuff trapped in it, hairs and fluff and sharper lumps, like bugs in amber. There were two massive windows, floor to ceiling, that flooded the place with streetlight all night long and let in the sounds of outside. You are never alone with noise and light, not completely.

From my windows I could see straight into other windows, then across the pattern of rooftops and into the tower of a Greek Orthodox church, and down on to the street below. I spent a long time looking.

It took me about a week to remember where I was when I woke up.

On the first day I cleaned the flat. I found a folded-up note between the floorboards that said please let me stay in this house forever, please let me, please. The handwriting was small and spiky and distinctive, all the words joined together like one long word. I closed it up and put it back where I found it, and I felt sorry that whoever wrote it didn’t get what they wanted. I felt sorry for them that I was there instead.

When everything was clean I unpacked my bag, which took all of ten seconds. Two T-shirts, three pairs of socks, a spare pair of jeans, toothbrush, toothpaste and soap, a spare jumper, the school uniform I’d taken off, the shell of my phone and two unreadable books which belonged to Max and should have been given back a long time ago.

On the second day I hung blankets on the windows, but they kept falling down so I gave up and learned how to live in a goldfish bowl without caring, like everyone else.

On the third I worked out how to use the little oven. Someone else’s cooking burned off the red elements and filled the room with hot, damp smoke.

On the fourth someone upstairs had a domestic in the darker hours of morning. Things kept falling past my windows on to the road below. Clothes float with grace and land silently, while cutlery is more chaotic.

On the fifth the electricity kicked out halfway through my shower because I’d forgotten to charge my top-up key.

On the sixth I walked in on somebody in the communal bathroom. They were just a shadow behind a curtain, but they were shouting.

On the seventh I ate toast and cream of tomato soup for the fourth time that week, and I thought about home and how I could never go back there.

On the eighth day it was raining. I watched the puddles growing on the road. Why did it make me think about me and Max, staying late at school? I didn’t want it to. It was the rain and the books by my bed that did it.

Max was chess club and I was football. I can’t play chess and he’s rubbish at football. Mum drove him home across the wind battered common which was bedraggled with sheep and rotting bracken. The house stood at a bend in the road, an L-shaped farmhouse with geese and dogs and mud in the yard. It had rained and the road was streaming down the hill towards us, and the windscreen was blind with puddle water.

We walked through his yard to the front door while Mum turned the car around. He didn’t knock. We just walked in and left our shoes inside the door. The house was warm and smelt of cinnamon, gold and orange against the grey of outside. I followed him into the kitchen and his mum was there, warming herself like a cat against the Aga.

Max’s mum didn’t think much of me. “Hello,” she said, and Max pretty much ignored her, but I looked at her and smiled because she wasn’t my family to ignore. Her hair was wet, bleeding water into the fabric of her shirt like blotting paper.

Max grabbed two apples from the fruit bowl and offered one to me across the table. I shook my head, so he offered it to her and she took it and bit hard. It was quiet between the three of us, and awkward.

“Wait there,” Max said suddenly without looking at me. “I’ll just get that thing.”

I had no idea what he was talking about.

I stayed where I was while he climbed the stairs and walked across the room over our heads. I listened to the wall clock and the hum of the fridge. There was a hole in my sock.

Max’s mum didn’t talk to me. She finished the apple. She arched her back and stretched her arms above her head. I saw the skin at her hips, above her jeans, below the lift of her shirt. Then she turned her back and filled a saucepan at the sink, started chopping carrots. I wasn’t there to her. I might have been a ghost in the room.

I was glad when Max came back with the thing – a book he’d been talking about in the car, something complicated about life on other planets. According to this book, there were so many galaxies and universes out there, even if the odds against life were a billion to one, there’d still be a billion planets teeming with it. As he gave it to me his mum looked at us and laughed quickly to herself. She knew I was never going to read it. I could tell just by the cover that I’d get bogged down on the first page and never pick it up again.

But Max wanted me to leave with something, if not an apple then a book, so I took it. I held its spine and flicked through the pages with my thumb. Mum beeped outside in the yard and I said I should be going, and Max’s mum left the room.

“See you mate,” I said, and Max said, “Bye,” and she said nothing.

I was putting my shoes back on at the door when he came running out of the kitchen. His socks made a shushing noise on the floorboards.

“Take this one as well,” he said. He was out of breath.

“Another book,” I said.

“The Ant Colony,” he said, in a voice like you hear at the cinema. “By Dr Bernard O Hopkins.”

I laughed. “Thanks Max.”

“It’s brilliant,” he said, looking at the book and not at me. “A real page turner.”

It was so like Max to talk about an ant book like that, like it was a thriller or something.

I said, “I won’t be able to put it down.”

He nodded, like that was the right answer, and he stood in the orange light of the doorway and watched me walk to the car.

On the drive home Mum and I talked about the books Max had given me. “Ants?” she said. “What a surprise.” Because Max was obsessed with them, how organised they were, how many of them there might be, how they all worked together like one animal. Max told me a long time ago that looking down at them made him think he was a giant towering over the earth.

Ants were what we did when we were seven and eight and nine. It was all Max wanted to do. I was like the genius professor’s assistant or something. We dug and photographed and measured. We tracked and timed and watched. We collected them in bottles. Max pickled specimens in vinegar and kept them in the garden shed. He’d forget where we were and who I was even, and everything was just about the ants.

When we got older, and everyone wanted to play football and drive cars on the common and get wrecked and show off down the river to girls, Max was still into ants. There wasn’t a cure for his ant thing.

I showed Mum the other book. I said, “Do you think the life on other planets idea comes from watching ants?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, ants are kind of weird, like from outer space, and Max has told me before he thinks humans are just like ants, even less if you put them in the context of the universe,”

“Very scientific.” Mum was smiling at me. “Some of his brain cells are rubbing off.”

“Leave it out, Mum,” I said.

She said, “I get vertigo just thinking about life on this planet, never mind scouting around somewhere else for more.”

We started inventing intergalactic package holidays, imagining a time when everybody had got bored of space travel because it was too easy, because everyone was doing it, because it was just not cool. I said Max might find someone nearer his IQ on planet Zargon.

Mum said, “What planet is he going to find his people skills on?”

She said this because Max is one of those clever people who are also about the shyest, most awkward you could meet. Often this can be mistaken for just rude.

“He was talking to you,” I said to Mum. “That’s a start isn’t it?”

“When was he talking to me?” she said.

“Today, in the car, about the book.”

“No,” she said, “he was talking to you.”

I smiled at Mum. “He was talking to you. He was looking at me.”

“See?” she said. “People skills. How do you know that anyway?”

“I know Max,” I said. “Haven’t I known him all my life?”

I told her that in school Max was different, in class anyway. In class Max didn’t speak in sentences – he spoke in whole paragraphs.

“Well, not to me he doesn’t,” Mum said. “I’m lucky if I get one syllable.”

I said, “Some people think one syllable is enough. Like Max’s Mum. She hardly talks to me.”

“Don’t get me started on that woman,” Mum said. “God knows what she’s got against you. I’ve no idea.”

“Whatever,” I said, and I looked out of the window at the rain and thought about something else. Like Rosie, this girl at school I was trying to impress. And Mr Hanlan, the Geography teacher who should’ve been a prison officer, and whether he’d notice I copied Max’s homework, and what he would do if he did. And what I was going to eat when I got home because I was starving.

I watched myself in that car, my head leaning against the water-beaded window, my mind on a lot of nothing. I watched from where I was sitting in a room in Camden with black floorboards, and I thought, if you knew when your life was about to start going wrong, would you change it before it was too late?

Four (Bohemia) (#ulink_732433cc-f33b-5184-8e80-81e6003f21e7)

The old lady with the dog was called Isabel. She seemed all right to me. Mum told me to watch out cos people like that were never nice for nothing. I was watching out, but I was just walking past her door when she said, “Come on in, whoever you are.”

It was like walking past a phone box when it rings. I’ve always wanted to do that. And then for the phone call to actually be for me.

She was in the kitchen. She said, “Help me get the lid off this bloody yoghurt. Damn stuff is supposed to be good for you and the stress of it is going to finish me.”

She had the pliers out and everything. She’d been trying to pull off the side of the pot cos she couldn’t see where the lid started. I flipped it open in about three seconds. First she looked angry with it and then she laughed.

“I’m Isabel,” she said. “I saw your nice door sticker. Is your name Cherry or Bohemia?”

“Bohemia.”

“Where did you get a name like that?” she said.

I shrugged. “Most people just call me Bo.”

“Well, it’s not a piece of fruit at least,” she said, sort of under her breath so I wouldn’t hear it, except I did. “Cherry your mum’s real name, is it?”

“I think so,” I said, because I’d never been asked that question before.

“Cherry Chapstick?”

“No, Cherry Hoban,” I said.

She started spooning yoghurt into a mug. I was looking at it so she asked me if I wanted some and handed me the rest of the pot. She asked me how old I was and I told her I was ten.

“Why aren’t you at school, Bohemia Hoban?” she said.

I liked that she used my whole name. It made me feel like somebody important. I said I was home-schooled cos that’s what Mum says.

Isabel put her hands on her hips then and clucked her tongue and said, “What lesson is it now then?”

“Yoghurt opening,” I told her, and she laughed.

She said being home-schooled was a lot more than wandering about the place waiting for my mum to wake up.

“She is awake,’ I said, which was actually true.

She said, “If your mum got a whiff of what home-school was about you’d be down the local primary in a second. Home-skiving’s what you’re doing.”

See? That’s why Mum didn’t like Isabel.

I didn’t look at her, even though I know she was looking at me. I ate some more yoghurt before she could ask for it back.

“So you’ve met us all then,” she said.

“I’ve met you and the landlord with the face.”

“That’s Steve,” she said. “Don’t stare. It was an accident with a facial peel.”

I asked her what one of those was and then I wished I hadn’t because it was something to do with burning your old skin off with acid.

I gave her back the yoghurt. “Why would someone want to do that?” I said.

She told me not to underestimate the power of getting old, or something. “Ask your mum,” she said. “Watch her closely when she hits forty.”

I asked her who else there was to meet.

“Well, you’ve got Mick to come – beard, bike, body odour. Met him yet?”

“Nope.”

“Aren’t you the lucky one.” She looked at her ceiling. “The flat above me’s empty, but it won’t be for long.”

“What about your dog?” I said, and I asked her what it was called.

“Doormat,” she said. “Where is he?”

I laughed. “Doormat,” I said after her. “I don’t know where he is, I haven’t seen him. Only that time when he was peeing.”

“He’s always peeing,” she said. “He’s trying to be macho. Go and have a look in his basket, would you? It’s by my bed. You have to boot him out in the mornings sometimes, tell him who’s boss.”

When I was out of the room she called after me, “I’ll make you some toast.”

Doormat was curled up in his basket with his face hidden in his bottom. He wagged his tail a bit, just at the tip, and he stretched like everything hurt. I picked him up and took him to the kitchen.

“Don’t spoil my dog,” Isabel said. “Make him use his legs or I don’t know what’ll happen.”

I put the dog down and he lay in the corner and hid his face in his bottom again. You really couldn’t tell which end of him was which, like a dog doughnut.

“What does your mum do for work?” Isabel said. She had her back to me while she cut the bread.

I said she was “between jobs” because I like the way it sounds, all grown up. I said she was having an interview at the pub down the road and she was getting ready for it right now. “She was there last night and the man offered her one, just like that.”

“I bet he did. You tell her I can always babysit if she needs.”

“I don’t need a babysitter. I can sit myself,” I said.

“Well, not when you’re ten dear, that’s not really allowed. But you know where I am.”

That’s when I told her the rules of babysitting because I found them out once in a library, to be sure. The rules are that you can leave your child at home whenever you like as long as you can get home in fifteen minutes and they are good at looking after themselves and being sensible and they have your phone number somewhere. So seeing as I’m very sensible and the pub was only down the road, I wouldn’t be needing a babysitter at all. That’s what I told her.

Nobody ever believes me. Isabel didn’t believe me either. She scribbled her phone number on a piece of paper and then she made me learn it and say it to her without looking, and then she asked me what I wanted on my toast.

“Anything.”

She asked me if I slept well and I said, “Fine, thanks. Me and Mum slept like logs.” I crossed my fingers she didn’t hear Mum coming in at four in the morning. I know it was four cos she made so much noise doing it. I think she tripped over and whoever was with her couldn’t see well enough in the dark to help her up. I think it was Steve.

I said, “Mum?” And I sat up in bed to see what was going on.

Mum said, “Shush, go to sleep, it’s four o’clock in the morning.” So that’s how I know.

They went into the kitchen and sat on the floor, and Steve must’ve been a very funny man cos Mum was just laughing and laughing. Maybe he told Mum about his facial peel.

I smiled at Isabel right through my lie, without even blinking, and she smiled back exactly the same, so maybe she knew and maybe she didn’t, but neither of us was going to say.

She put a pile of toast on the table. Isabel made her own bread. It had all lumps and bits in it, but it wasn’t as bad as it sounds.

I was on about my fifth bit when I heard Mum’s shoes on the stairs. She was coming down carefully cos of the heels. I could picture her, sort of sideways and a bit stiff looking, pressing her hands against the walls. I brushed the crumbs off my front and Doormat jumped up and started hoovering them straight away, like a living, breathing dust buster. He followed me when I went and put my head out the door. Maybe he thought I’d leave a trail of crumbs.

“What are you doing in there?” Mum said. She looked pretty and important, and you couldn’t tell she’d had two late nights in a row at all.

“Just visiting Isabel.”

“Oh yeah?” she said and she came in the flat and almost trod on the dog. “Oh shit!” she said “Sorry, dog,” as she walked in the kitchen.

“It’s funny cos his name is Doormat,” I said to her, but it was only me who was laughing.

“Hello, Isabel,” she said and she sounded really loud in the tiny kitchen. “I’m Cherry, Bo’s mum. Is she bothering you at all? You all right with her in here?”

“I invited her in,” Isabel said. She wasn’t really smiling.

“Well, that’s nice,” Mum said. “I’m off now. Job interview. I’ll be back in a bit. Wish me luck.”

I put my arms round her waist and she smelled all lovely, and she kissed me in that way she does when she’s thinking about her lipstick, all gentle and hardly there, like an eyelash or a butterfly.

Mum was almost out the door when Isabel called after her, asking should she give me my lunch as well as my breakfast. There was a bit of an edge in the way she said it that made me feel bad for eating so much toast.

“No need,” Mum said, clicking back in and looking hard at me. “I’ll be back by then. And Bo has lunch money, don’t you, darling?”

I shook my head. It was quiet and nobody moved. I counted to three. Then Mum opened her purse and shoved a crumpled fiver in my hand. It was soft and old like tissue. I opened it out to have a proper look. I didn’t know what to think. I never normally got that much just for lunch.

Mum told me not to spend it all at once and then she said, “Come and kiss me goodbye then.”

I followed her to the door. She took the fiver off me and put it back in her purse. “Sorry, Bo,” she said. “It’s all we’ve got. I won’t be long. I’ll bring you back a sandwich or something.”

And then she was gone.

I pretended to be putting the money in my pocket when I walked back in. I didn’t want Isabel thinking anything about anything.

Five (Sam) (#ulink_c9b21bba-cf5d-59ea-b384-20d9114c77a0)

The old lady on the ground floor was nocturnal and so was her dog, probably through habit rather than choice, because she walked it in the middle of the night. I know because that’s how we met, on my eighth day. She got locked out at half past four in the morning. I believed her at the time anyway. She was the first person to speak to me in my new life.

There was a park just round the corner. I learned to call it a park, but actually it was a patch of grass with two benches and some bushes and a bin for dog shit. It was also an openair crack house. Isabel told me, but she clearly didn’t care. She’d been there the night I had to let her in. She threw stones at my window. I thought I’d dreamed them.

“Oi!” she said in this shouting sort of whisper. “Country! Get down here and open the door.”

I had to put some clothes on. The stairs were cold and gritty under my feet and I could hardly see. I thought I might still be asleep. She stood there on the doorstep like I’d shown up three hours late to collect her.

“Doesn’t anyone brush their hair any more?” she said.

It felt strange, someone talking to me, like having a spotlight shined in my eyes.

“How long’ve you been here?” she said.

I had to clear my throat to speak, like it was rusty. “I just got up,” I said.

“No, Einstein, how long’ve you lived here?” she said.

“Oh. About ten days.”

“I haven’t seen you,” she said, like that meant I was lying. She was feeling about for her spare key above the doorframe but she wasn’t quite tall enough to reach.

“Well, I’ve been here,” I said. “I’ve been keeping to myself.” I got the key for her.

She looked me up and down and laughed once. “Pink lung disease.”

“What?”

“Pink lung disease. Don’t you young people know anything?”

She told me about this policeman at the dawn of the motor age who got sent from his village to do traffic duty in Piccadilly. He wasn’t any good at directing traffic. Nobody was because it was a new thing. The policeman got hit by a car and he died. The doctor who cut him up had never seen healthy, pink, country lungs before. He was used to city lungs, all black and gooey, so he said that was the cause of it. Pink lung disease. Not a car driving over him at all.

She looked at me the whole time she was talking. She was the very first person to see me since I’d been here. I was conscious of it.

“You’ve got lovely country skin,” she said. “Look at the glow on you.”

“Thanks,” I said, because I didn’t know how else to take it.

“You stick out like a sore thumb with that healthy skin.”

“No I don’t,” I said.

“Put that key back for me, would you?” she said, and I reached up and put it back above the doorframe. She noticed my watch. It has a thick strap. I always wear it. “What’s the time?” she said.

“Four thirty-six.”

“Well, what are you standing here for, at that hour?” she said, and she sent me back to my room and shut the door behind her, like she’d forgotten I was only standing there because of her.

I couldn’t go back to sleep. Someone was boiling a kettle in the flat upstairs. I heard the plug going into the socket, the switch click to ON, the thrum of the water bubbling on the counter top. I heard an alarm clock somewhere beep seventeen and a half times and then stop. I heard the scrape and warble of pigeons waking up on the windowsill.

I pictured the walls and ceilings and floors separating everyone in their little boxes. I thought about how thin they were, and what might be between them, like dust and mice and lost letters, like feathers and crumbling plaster and hundred-year-old wallpaper. I thought about everyone in the whole city, alone in our boxes like squares on graph paper, like scales on a fish, like ants.

Now I was an ant, maybe Max would’ve liked to study me, navigating my way round the Tube, walking down a crowded street without colliding, stacking shelves and watching them empty again, sweeping my floor, putting the rubbish out.

Do ants know that they are working for the colony? That whatever little job they get to do until they die actually forms a meaningful part of the whole? Do they know that? Because I certainly didn’t.

Have you ever done that thing where you interrupt a line of ants? They’re all moving along, no questions asked, filled with a sense of purpose, and you draw a line across their path in the mud or the sand or whatever, just a line, with a stick or your shoe or an empty vinegar bottle. The ants in front of the line carry on like nothing happened, like there’s nothing to worry about. They don’t look back. But the ones behind the line, the ones who walk into it, they lose the plot. It’s like they all go insane and run around tearing their hair out because they’ve got no idea what the hell they’re supposed to be doing. Like they’ve forgotten everything they ever knew.

Max hated it when I did that. It drove him crazy.

That’s what I was wondering, sitting in my room listening to other people who didn’t know that I existed. If Max was watching me then from above, what side of the line in the ants was I on?

A few nights later I bumped into the old lady again in the hallway. It wasn’t late. I was going out for some air because I’d been in my room all day. She came out of her flat just before I got to the front door.

“Ah, Country,” she said. “Come in, meet the neighbours.”

I didn’t want to meet anyone. I shook my head. “No thanks,” I said, and I opened the door. I could see a slice of blackish, street-lit sky. I could smell the warm metal and dust of outside.

“You’ve got to meet the neighbours,” she said.

“No, it’s all right.”

The door was properly open now. Two people walked past on the street, a man and a woman, and they glanced up at me in the light of the hall for less than a second. My shadow was long down the front steps.

She said, “What are you on about, ‘No, it’s all right’? It’s the rules. I have to introduce you.”

I said I’d rather she didn’t.

“What do you mean?”

She was standing in the doorway now and I was halfway to the pavement. I couldn’t really see her face because the light was behind her.

“I don’t want to meet the neighbours,” I said.

“Suit yourself,” she said. She pushed the door shut in front of her, its rectangle of light on the street disappearing in one quick, diminishing movement.

“I will,” I said to nobody at all.

I wasn’t out for long. I walked about. I sat on a bench at the canal. I watched people in cafes and bars to see what they were doing with their time. I got a newspaper and stared at some TV through the window at Dixons for a bit.

When I got back the lights were still on at the old lady’s house. I could see them from the street. Inside, the door to her flat was open. I heard her moving around, heard the muffled sound of her voice and the tap of the dog’s feet somewhere, like fingers on a table. I leaned my head against the edge of the front door and watched the sky slice squeeze to nothing while I closed it without making a sound.

“What’s your name, anyway?” she said suddenly close behind me, before I’d even turned around.

“God, you made me jump,” I said.

“Sorry,” she said. She asked me my name again.

“Sam.”

She repeated it, like she was testing it for something.

“I’m Isabel,” she said. “Meet the neighbours for five minutes and I won’t ask you to do anything ever again.”

What a good liar.

Her place was crowded and tiny, like someone had pushed the walls together after she’d moved her furniture in, like the storeroom of a bad antique shop.

Steve was there, the landlord, wearing sunglasses inside, something I think you’re allowed to hold against a person as soon as you meet them. The dog was in one chair, his nose tucked down between the arm and the cushion, the whites of his eyes new moons as he glanced up at me and breathed out hard with pure boredom. In the other chair there was a hungry-looking bloke with a big pale beard his face was way too small for. He frowned at me and licked his lips, which looked lost in the middle of all that hair. His sweatshirt was the colour of dead grass. He had a full size tattoo of a gun on the side of his calf. It was poking out of his sock like it was a holster. I couldn’t keep my eyes off it once I knew it was there.

And on the arm of his chair there was a woman called Cherry, thin and blonde and pretty, and just about the tiredest person I ever saw. Her nails were bitten so low, so close to where they started, I couldn’t look at them. Her fingers were covered in rings.

Isabel introduced me as Country. Steve nodded at me behind his shades and clinked the ice cubes in his glass. Cherry waved with one hand and covered a yawn with the other.

“Mick,” the man in the chair said. “You walked in on me in the bathroom the other day.”

Steve said to Mick, “You probably woke him up the night before chucking your stuff out of the window.”

“Sorry,” I said, and he grunted at Steve, something about getting a lock on the door that worked.

“Oh, cheer up, Mick,” Isabel said. “There’s always someone worse off than you. Take Country here. Not a friend in the world.”

“Really?” Mick said, perking up a bit, like this was good news.

“Not a soul,” Isabel said, patting me on the arm.

She started explaining where everybody lived: Steve in the basement, her on the ground floor, me and the bathroom on the next, Mick on the third floor and Cherry and her daughter at the top.

“Welcome to the madhouse,” Steve said, and drained his glass.

There was a silence then that I wasn’t going to fill. Cherry stared out of the window, chewing at her nails. Isabel said she was going to get me a drink. Steve followed her out.

Cherry lit a cigarette and dragged on it like there was something at the very end she was looking for. She had too much make-up on. When she brought her hand up to her mouth it looked like somebody else’s hand entirely, somebody paler and older.

Mick said to nobody in particular, “Why are we here?”

I didn’t know if he meant there, in Isabel’s room, or in London, or even alive, and I had no idea of how to answer him.

I got up and tried to see out of the windows. There was a spiral staircase down to a tiny yard, like five hay bales side by side. There were window boxes crammed with rainbashed petunias. Inside, Isabel’s sofas matched the curtains and the carpet was a pond-weed green. There were a couple of paintings on the walls, of ships and insipid landscapes, and they might have some value to an old lady, but they didn’t mean anything to me. The most interesting thing in the room by a mile was a clay head on top of a bookcase, a peaceful man with a wide nose and closed eyes. I liked the tight curl of his hair, the fingerprint marks of the hands that had made him on his skin.

Isabel came back with the drinks and sat down in the chair next to Doormat. I stayed standing until she told me to stop it and then I knelt on the floor.

There were crisps in a bowl on the coffee table. I didn’t eat that many because the sound of them was too loud in my head and I didn’t want to fill the room with crunching. Mick was on to them like only he knew it was the last meal in the building. Little bits of crisp littered his beard like dandruff.

Isabel said there were more in the kitchen and he should go and get them.

Mick looked like his bones were melting. “Can’t the new boy do it?”

“No, he can’t,” Isabel said. “And his name is Country.”

I wanted to leave. “My name is Sam,” I said, but nobody took any notice.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/jenny-valentine/the-ant-colony/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Jenny Valentine

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An irresistible novel from Guardian-award-winning novelist, Jenny Valentine.Number 33 Georgiana Street houses many people and yet seems home to none. To runaway Sam it is a place to disappear. To Bohemia, it′s just another blip between crises, as her mum ricochets off the latest boyfriend. Old Isobel acts like she owns the place, even though it actually belongs to Steve in the basement, who is always looking to squeeze in yet another tenant. Life there is a kind of ordered chaos. Like ants, they scurry about their business, crossing paths, following their own tracks, no questions asked.But it doesn′t take much to upset the balance. Dig deep enough and you′ll find that everyone has something to hide…