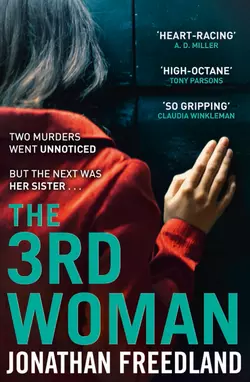

The 3rd Woman

Jonathan Freedland

THE FIRST TWO MURDERS WENT UNNOTICED. BUT THE NEXT WAS HER SISTER…A terrifying yet unputdownable thriller from No. 1 bestselling author and award-winning journalist Jonathan Freedland.SHE CAN’T SAVE HER SISTERJournalist Madison Webb is obsessed with exposing lies and corruption. But she never thought she would be investigating her own sister’s murder.SHE CAN’T TRUST THE POLICEMadison refuses to accept the official line that Abigail’s death was an isolated crime. She uncovers evidence that suggests Abi was the third victim in a series of killings hushed up as part of a major conspiracy.SHE CAN EXPOSE THE TRUTHIn a United States that now bows to China, corruption is rife – the government dictates what the ‘truth’ is. With her life on the line, Madison must give up her quest for justice, or face the consequences…

Copyright (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Jonathan Freedland 2015

Jonathan Freedland asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photographs © Nikaa / Arcangel Images;

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007413690

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007413706

Version 2015-12-22

Dedication (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

For my sister Fiona, 1963–2014.

A woman of strength, wisdom, laughter and constant love

Table of Contents

Cover (#u1473dc4c-7261-53b7-87a5-45f768124d54)

Title Page (#ufd60f60e-e0b1-557a-a7c9-8ddfcf53c84b)

Copyright (#uac30da58-c71c-58ac-892d-5a18858511c9)

Dedication (#u78723b56-b5c2-5c18-837e-e1a040890374)

Prologue (#ua912ab7e-b23d-55f5-a3c8-f580e5f8d8b1)

Chapter 1 (#uae29a586-1e6c-5243-aa2f-91684a9fd345)

Chapter 2 (#uc61d3baf-99da-56db-9640-316ef2af6bc5)

Chapter 3 (#u944a86fe-89f2-5f52-8f87-753dc1efe211)

Chapter 4 (#uf0c33783-550a-593f-9d29-3bb1c15ae191)

Chapter 5 (#u325a94e4-88b5-5546-8af1-73238d126ec8)

Chapter 6 (#u3ccc288e-b1e3-5811-ac79-ac5e4eea1d0e)

Chapter 7 (#u4f572147-9b65-55b0-a6bf-5a7f66f2c353)

Chapter 8 (#u653f7b0c-8495-51e9-9a35-b925d37d2ad3)

Chapter 9 (#uf2c49e8d-c20b-5332-99a9-1b1016f37222)

Chapter 10 (#ud0d43590-416d-585a-ae08-1414b37ea6c0)

Chapter 11 (#ud1103a59-028b-5f67-861c-6dcd1cdaa75c)

Chapter 12 (#ub8113128-c662-5708-801e-bfc3289babcd)

Chapter 13 (#u4e9e4ab1-707a-5714-b1ab-e6d51edb2e5c)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the author (#litres_trial_promo)

Writing as Sam Bourne (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

It was the last day of January and the New Year was approaching. The city of Los Angeles had been winding down for more than a week. The only place still humming was the airport, as the expats headed home, crossing the ocean to see devoted fathers, doting mothers and the occasional abandoned wife. Offices were closing early: with no one on the end of the phone and no deals to be made, there was little point staying open. It was the second break in six weeks, but this one felt less wanted and somehow involuntary, the way a city falls quiet during a strike or a national day of mourning. Still, the red lanterns hanging from the lampposts and trees gave the city some welcome cheer, especially after dark.

Not that it gave her much comfort. The night had never been her time. She had always been a child of the early mornings, up with the sun. She lost interest in the sky once it was no longer blue. She was the same now, even in winter, running out into the morning as soon as it had broken.

Which was another reason why she hated having to do this. Working in this place was bad enough, but the time was worse. These were hours meant for sleep.

But she managed to be cheery to the girls when she said goodbye, throwing her clothes into a tote bag and slinging it over her shoulder in a single, well-practised movement. She gave the guy on the door a smile too even though her jaw felt strained from a night spent in a fixed expression of delight.

Walking to her car out in the lot, she kept her eyes down. She had learned that lesson early enough. Avoid eye contact inside if you could, but never, ever meet anyone’s eye once you were outside.

She aimed the key fob at the car door but it made a useless, dull click. Three more goes, three more empty clicks. The battery on the damn thing was fading. Opening the car door manually, she got in, taking care to lock the door after her.

The drive back was quicker than usual, thanks to the New Year emptiness. She put on a music station, playing oldies, and tried to forget her evening’s work. She looked in her rear-view mirror occasionally, but besides the smog there was precious little to see.

At the apartment building, she had her key in hand and the entrance door opened smoothly. Too tired to close it after her, she let it swing slowly shut. All the same, something made her glance over her shoulder but in the dark she saw nothing. This was why she hated working late at night: she was always jumping at shadows.

When the elevator opened on her floor and she nudged the key into the apartment’s front door, he was ready for her. She had heard no sound, her first awareness of his presence being the gloved hand over her mouth. Her nostrils sought out the air denied to her mouth, filling instantly with the scent of unwashed leather and sweat. Worse was the breath. The urgent, hot breath of a stranger against her neck, then dispersing around it, as if enveloping her.

She tried to call out. Not a scream but a word. If her mouth had not been gagged it might have come out as ‘What?’

All of that was in the first second. But now, in the moments that followed, there was time for fear. It sped through her, throbbing out from her heart through her veins, into her brain, which seemed to be filling with flashing red and yellow, and then into her legs, which became light and unsteady. But she did not fall. He had her in his grip.

She felt him use his weight to push the apartment door, already unlocked, wide open, his shove splintering wood off the frame. Once she was bundled inside, he closed the door – deliberately not letting it slam.

Now the scream rose, trying to force its way through her chest and into her throat, but it came up against the leather hand and seemed to be pushed back into her. She felt his left hand leave her shoulder and move, as if checking for something.

Instinctively she tried to wriggle free, but his right arm was too strong. It held her in place, sealing her mouth at the same time.

Now she heard a ripping noise: had he torn her clothes? The first, primeval, terror had been of death, that this man would kill her. But the second fear, coming in instant pursuit, was the horror that he would push his brute body into hers. She made a wordless calculation, a bargain almost: she would withstand a rape if he would let her live.

But the sound she had heard was not of torn clothing. She saw his left hand hover in front of her face, a piece of wide, silver-coloured masking tape spanned between its fingers. Expertly, he placed it over her mouth, leaving not so much as a split-second in which she could emit a sound.

Now he grabbed her wrists, containing them both in the grasp of a single hand. Still behind her, still not letting her glimpse his face, he pushed her towards the centre of the room, in front of the couch. He shoved the coffee table out of the way with one foot, then tripped her from behind, so that she was face down on the carpet with pressure on her back, a knee holding her in position.

This is it, she thought. He’ll rip my clothes off now and do it here, like this. She told herself to send her mind elsewhere, so that she could survive what was to follow. Live through this, she thought. You can. She closed her eyes and tried to shut down. Live through this.

But he had not finished his preparations. A strip of black cloth was placed over her eyes, then tied at the back. Next, this man – whose face she had not seen, whose voice she had not heard – flipped her over, firmly but not roughly. Perhaps he had sensed that her strategy for survival was to co-operate.

One wrist was pulled above her head, so that she looked like a child demanding the teacher’s attention. A moment later, the wrist was encircled by a kind of plastic bracelet. Loose at first, but then she heard that distinctive zipping sound she remembered from childhood, the sound of a hardware-store cable tie. Her father would use them to bundle loose wires together, keeping them neat behind the TV set; they were impossible to break, he said. Now this man did the same to her right wrist. She was lying on the floor, gagged and blindfolded, with both her arms stretched upward and tied to a single leg of the couch.

She willed her mind to transport itself somewhere else. But the fear was making her teeth chatter. Nausea was working its way up from her stomach and into her mouth. Please God, let this be over. Let this end, please God.

It was all happening so fast, so … efficiently. There was no rage in this man’s actions, just purpose and method, as if this were a safety drill and he was following an established procedure. One of his hands was now on her right arm, except the touch was not the rough leather she had felt over her mouth. It was light, just a fingertip, but not human skin. Sightless, she could not be sure of the material, but the hand was close enough to her face that she could smell it. It was latex. The man was wearing latex gloves. Now a new terror seized her.

He gripped her wrist again and then she felt it, the sharp puncture of a needle plunged into her right arm. She cried out, hearing only the sound of a muffled exclamation that seemed to come from somewhere else entirely.

And then, in an instant, the fear melted away, to be replaced by a rapid, tingling rush, a wave of blissful comfort. She felt no pain at all, just a deep, wide, unexpected happiness. When the tape was removed from her mouth, she let out no scream. Perhaps she had succeeded in sending herself far away after all, onto the Malibu beach at dawn, where the sand was kissed by sun. Or into a clear-blue ocean. Or into a hammock on a desert island in the South Pacific. Or into a cabin in mid-winter, the amber glow warming her as she lay on the rug before a fire that popped and crackled.

She heard the distant sound of the cable tie being cut loose, its job now done. She sensed the blindfold coming away from her face. But she felt no urge to open her eyes or move her arms, even though she was now free. Every nerve, every synapse, from her toes to her fingernails, was dedicated instead to passing messages of pleasure to her brain. Her system was flooded with goodness; she was a crowd assembling on the mountain top at the moment of the Rapture, every face grinning with delight.

Now she felt the lightest, most fleeting sensation between her legs. A hand was peeling back her underwear. Something brushed against her. It did not penetrate. It did not even bother her. Rather something still and smooth was resting there, against her most intimate place. She felt her skin kissed by silk petals.

A second passed and she was in the sealed, safe hiding place before any of that, floating in the fluid that could nourish her and support her and where no one could disturb her. She was in her mother’s womb, utterly content, breathing only love and love and love.

Chapter 1 (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

Normally Madison Webb liked January. If you grew up used to golden California sun, winter could be a welcome novelty. The cold – not that it ever got truly cold in LA – made your nerves tingle, made you feel alive.

Not this January, though. She had spent the month confined to a place of steel and blank, windowless walls, one of those rare corners of LA compelled to operate throughout the Chinese New Year. It never stopped, day or night. She had been working here for three weeks, twenty shifts straight, taking her place alongside the scores of seamstresses hunched over their machines. Though the word ‘seamstresses’ was misleading. As Maddy would be explaining to the LA public very soon, the word suggested some ancient, artisan skill, while in reality she and the other women were on an assembly line, in place solely to mind the devices, ensuring the fabric was placed squarely in the slot and letting the pre-programmed, robotic arm do the rest. They were glorified machine parts themselves.

Except that machines, as she would put it in the first in a series of undercover reports on life in an LA sweatshop, would be treated better than these people, who had to stand at their work-stations for hours on end, raising their hands for a bathroom break, surrendering their phones as they arrived, lest they surreptitiously try to photograph this dingy basement where, starved of natural light and illuminated by a few naked lightbulbs, she felt her eyesight degraded by the day.

Being deprived of her phone had presented the most obvious obstacle, Maddy reflected now, as she fed a stretch of denim through the roller, ensuring its edges aligned before it submitted to the stitching needle. She had worked with Katharine Hu, the resident tech-genius in the office and Maddy’s best friend there, to devise a concealed camera. Its lens was in the form of a button on her shirt. From there, it transmitted by means of a tiny wire to a digital recorder taped into the small of her back. It did the job well, giving a wide-angled view of everything she faced: turn 360 degrees and she could sweep the whole place. It picked up snatches of conversation with her fellow seamstresses and with Walker, the foreman – including a choice moment as he instructed one ‘bitch’ to get back to work.

With nearly two hundred hours of recordings, she knew she had enough to run a story that would have serious impact. The camera had caught in full the incident nearly a week ago when Walker had denied one of Maddy’s co-workers a bathroom break, despite repeated requests. The woman’s pleas had grown desperate, but he just bellowed at her, ‘How many times do I have to say it, shabi? You been on your break already today.’ He used that word often, but calling a woman a cunt in a room full of other women represented an escalation all the same.

When the other workers started yelling, Walker reached for the night-stick that completed his pseudo-military, brown-and-beige polyester uniform, the kind worn by private security guards in supermarkets. He didn’t use the weapon but the threat of it was enough. The crying woman collapsed at the sight of it. A moment or two later a pool of liquid spread from her. At first they thought it was the urine she had been struggling to contain. But even in this light they could see it was blood. One of the older women understood. ‘That poor child,’ she said, though whether she was referring to the woman or the baby she had just miscarried, Maddy could not tell. She had been near enough to film the whole scene. Edited, it would appear alongside the first article in the series.

She was writing in her head at this very moment, mentally typing out what would be the second section of the main piece. Everyone knew already that sweatshops like this one were rife across California, providing cheap labour, thanks mainly to migrants who had dashed across the Mexican border in the dead of night, to make or finish goods for the US or Latin American markets. That wasn’t news. LA Times readers knew why it had happened too: these days the big Chinese corporations found it cheaper to make goods in LA than in Beijing or Shanghai, now that their own workers cost so much. What people didn’t know was what it was actually like inside one of these dumps. That was her job. The stats and the economics she’d leave to the bean-counters on the business desk. What would get this story noticed was the human element, the unseen workers who were actually paying the price. Oh, that sounded quite good. Maybe she should use that in the intro. The unseen workers—

There was a coughing noise, not especially loud but insistent. It came from the woman opposite her on the production belt, an artificial throat-clearing designed to catch her attention. ‘What?’ Madison mouthed. She glanced up at her machine, looking for a red light, warning of a malfunction. Her co-worker raised her eyebrows, indicating something about Maddy’s appearance.

She looked down. Emerging from the third buttonhole of her shirt was a tiny piglet’s tail of wire.

She tried to tuck it away, but it was too late. In four large strides, Walker had covered the distance between them – lumbering and unfit, but bulky enough to loom over her, filling the space around her.

‘You give me that. Right now.’

‘Give you what?’ Maddy could hear her heart banging in her chest.

‘You don’t want to give me any taidu now, I warn you. Give it to me.’

‘What, a loose thread on my shirt? You’re ordering me to remove my clothes now, is that it, Walker? I’m not sure that’s allowed.’

‘Just give it to me and I’ll tell you what’s allowed.’

That he spoke quietly only made her more frightened. His everyday mode was shouting. This, he knew – and therefore she knew and all the women standing and watching, in silence, knew – was more serious.

She made an instant decision, or rather her hand made it before her brain could consider it. In a single movement, she yanked out the tiny camera and dropped it to the floor, crunching it underfoot the second it hit.

The foreman fell to his knees, trying to pick up the pieces: not an easy manoeuvre for a man his size. She watched, frozen, as the tiny fragments of now-shattered electronics collected in his palm. It was clear that he understood what they were. That was why he had not shouted. He had suspected the instant he caught sight of the wire. Recording device. His instructions must have been absolute: they were not tolerated under any circumstances.

Now, as he pulled himself up, she had a split-second to calculate. She had already got three weeks of material, downloaded from the camera each night and, thanks to Katharine, safely backed up. Even today’s footage was preserved, held on the recorder strapped to her back, regardless of the electronic debris on the floor. There was nothing to be gained from attempting to stay here, from coming up with some bullshit explanation for the now-extinct gadget. What would she say? And, she knew, she would be saying it to someone other than Walker. There was only one thing she could do.

Swiftly, she grabbed the security tag that hung around the foreman’s neck like a pendant, whipped it off and turned around and ran, past the work benches, heading for the stairs. She touched Walker’s tag against the electronic panel the way she’d seen him release the women for their rationed visits to the bathroom.

‘Stop right there, bitch!’ Walker was shouting. ‘You stop right there.’ He was coming after her, the thud of each footstep getting louder. The door beeped. She tugged at it, but the handle wouldn’t open. She held the damn card against the panel once more and this time, at last, the little light turned green, accompanied by another short, sharp and friendlier beep. She opened the door and stepped through.

But Walker had been fast, so that now his hand reached through and grabbed at her shoulder. He was strong, but she had one advantage. She swivelled to face him, grabbed the door and used all of her strength to slam it shut. His arm was caught between the door and the frame. He let out a loud yowl of pain and the arm retracted. She slammed the door again, hearing the reassuring click that meant it was electronically sealed.

Leaping up the stairs two at a time, she clutched at the rail as she reached the first landing and pulled herself onto the next flight, seeing daylight ahead. She would only have a few seconds. Walker was bound to have alerted security in reception by now.

Maddy was in the short corridor that led to the entrance of the building. From the outside it resembled nothing more than a low-rent import–export office. That was in her article, too. If you walked past it, you’d never know what horrors lay beneath.

She breathed deep, realizing she had no idea what to do next. She couldn’t breeze out, not from here. Workers were allowed to exit only at prescribed times. They would stop her; they’d call down to Walker; they’d start checking the computer. She needed to think of something. Her head was pounding now. And she could hear sounds coming from below. Had Walker got the downstairs door open?

She had the merest inkling of a plan, no more than an instinct. Flinging the door open, her voice rising with panic, she bellowed at the man and woman manning the front desk. ‘It’s Walker! I think he’s having a heart attack. Come quick!’

The pair sat frozen in that second of paralysis that strikes in every crisis. Maddy had seen it before. ‘Come on!’ she shouted. ‘I think he might be dying.’

Now they jumped up, barrelling past her to get down the stairs. ‘I’ll call for an ambulance!’ she shouted after them.

She had only a second to look behind the desk, at the grid of cubby-holes where they kept the women’s confiscated phones. Shit. She couldn’t see hers. She thought of simply rushing out there and then, but she’d be lost without it. Besides, if they found it once she’d gone, they’d instantly know who she was and what she’d been working on.

Commotion downstairs. They’d be back up here any second. She moved her eye along the slots one last time, trying to be methodical while her head was about to explode. Calm, calm, calm, she told herself. But it was a lie.

Then at last, the recognizable shape, the distinct colour of the case, lurking in the corner of the second last row. She grabbed it and rushed out of the door, into the open air.

The sound of the freeway was loud but unimaginably welcome. She had no idea how she would get away from here. She could hardly wait for a bus. Besides, she had left her wallet downstairs, tucked inside her now-abandoned bag.

As she began running towards the noise of the traffic, working out who she would call first – her editor to say they should run the story tonight or Katharine to apologize for the broken camera – she realized that she had only one thing on her besides her phone. She unclenched her fist to see Walker’s pass now clammy in her hand. Good, she thought. His photo ID would complement her article nicely: ‘The brute behind the brutality.’

Seven hours later the story was ready to go, including a paragraph or two on her ejection from the sweatshop and accompanied online by several segments of video, with greatest prominence given to the miscarriage episode. ‘How LA sweatshop conditions can mean the difference between life and death.’ Use of the Walker photo had taken up nearly an hour’s back-and-forth with the news editor. Howard Burke had worried about naming an individual.

‘Fine to go after the company, Madison, but you’re calling this guy a sadist.’

‘That’s because he is a sadist, Howard.’

‘Yes, but even sadists can sue.’

‘So let him sue! He’ll lose. We have video of him causing a woman to lose her baby. Jeez, Howard, you’re such—’

‘What, Maddy? What am I “such a”? And tread carefully here, because this story is not going anywhere till I say so.’

There was a silence between them, a stand-off of several seconds broken by her.

‘Asshole.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘You’re such an asshole. That’s what I was going to say. Before you interrupted me.’

The exchange that followed could be heard at the other end of the open-plan office.

Burke’s frustration overflowing, he drove his fist through an office partition, which newsroom historians recorded was the second time he had performed that feat – the first some four years earlier, also prompted by a clash with Madison Webb.

It took the intervention of the executive editor herself to broker a compromise. Jane Goldstein summoned Maddy into her office, making her wait while she took evidence from Howard over by the newsdesk. Clearly she had decided it was too risky to have them both in the same room at once.

It gave Maddy time to look at the boss’s power wall, which was a departure from the usual ego mural. Instead of photos with assorted political bigwigs and worthies, Goldstein had displayed a series of framed front pages of the biggest story she – or any other American reporter since Ed Murrow – had ever covered. She’d won a stack of Pulitzers, back when that had been the name of the biggest prize in US journalism.

Maddy’s phone vibrated. A message from a burnt-out former colleague who had left the Times to join a company in Encino making educational films.

Hey Maddy. Greetings from the slow lane. Am attaching my latest, for what it’s worth. Not exactly Stanley Kubrick, but I’d love any feedback. We’ve been told to aim at Junior High level. The brief is to explain the origins of the ‘situation’, in as neutral a way as possible. Nothing loaded. Tell me anything you think needs changing, especially script. You’re the writer!

With no sign of Goldstein, Maddy dutifully clicked the play button. From her phone’s small speaker, the voiceover – deep, mid-Western, reliable – began.

The story starts on Capitol Hill. Congress had gathered to raise the ‘debt ceiling’, the amount of money the American government is allowed to borrow each year. But Congress couldn’t agree. There was footage of the then-Speaker, banging his gavel, failing to bring order to the chamber.

After that, lenders around the world began to worry that a loan to America was a bad bet. The country’s ‘credit rating’ began to slip, downgraded from double A-plus to double A and then to letters of the alphabet no one ever expected to see alongside a dollar sign. That came with a neat little graphic animation, the A turning to B turning to C. But then the crisis deepened.

On screen was a single word in bold, black capital letters: DEFAULT. The voiceover continued. The United States had to admit it couldn’t pay the interest on the money it owed to, among others, China. In official language, the US Treasury announced a default on one of its bonds.

Now there were images of Tiananmen Square. Beijing had been prepared to tolerate that once, but when the deadlock in Congress threatened a second American default, China came down hard. A shot of the LA Times front page of the time.

Maddy hit the pause button and splayed her fingers to zoom in on the image. She could just make out the byline: a young Jane Goldstein. The headline was stark:

China’s Message to US: ‘Enough is enough’

A copy of that same front page was here now, framed and on Goldstein’s wall.

At the time the People’s Republic of China was America’s largest creditor, the country that lent it the most money. And so China insisted it had a special right to be paid back what it was owed. Beijing called for ‘certainty’ over US interest payments, insisting it would accept nothing less than ‘a guaranteed revenue stream’. China said it was not prepared to wait in line behind other creditors – or even behind other claims on American tax dollars, such as defence or education. From now on, said Beijing, interest payments to China would have to be America’s number one priority.

Maddy imagined the kids in class watching this story unfold. The voice, calm and reassuring, was taking them through the events that had shaped the country, and the times, they had grown up in.

But China was not prepared to leave the matter of repayment up to America. Beijing demanded the right to take the money it was owed at source. America had little option but to say yes. There followed a clip of an exhausted US official emerging from late night talks saying, ‘If China doesn’t get what it wants, if it deems the US a bad risk, there’ll be no country on earth willing to lend to us, except at extortionate rates.’

Experts declared that the entire American way of life – fuelled by debt for decades – was at risk. And so America accepted China’s demand and granted the People’s Republic direct access to its most regular stream of revenue: the custom duties it levied on goods coming into the US. From now on, a slice of that money would be handed over to Beijing the instant it was received.

But there was a problem: Beijing’s demand for a Chinese presence in the so-called ‘string of pearls’ along the American west coast – the ports of San Diego, Los Angeles, Long Beach and San Francisco. China insisted such a presence was essential if it was to monitor import traffic effectively.

Now came a short, dubbed clip of a Beijing official saying, ‘For this customs arrangement to work, the People’s Republic needs to be assured it is receiving its rightful allocation, no more and no less.’

The US government said no. It insisted a physical presence was a ‘red line’. Finally, after days of negotiation, the two sides reached a compromise. A small delegation of Chinese customs officials would be based on Port Authority premises – including in Los Angeles – but this presence would, the US government insisted, be only ‘symbolic’.

Archive footage of a CBS News broadcast from a few months after that agreement, reporting Chinese claims of smuggling and tax-dodging by American firms, crimes they suspected were tolerated, if not encouraged, by the US authorities. Beijing began to demand an increase in the number of Chinese inspectors based in Los Angeles and the other ‘string of pearl’ ports. Each demand was resisted at first by the US authorities – but each one was met in the end.

Next came pictures of the notorious Summer Riots, a sequence that had been played a thousand times on TV news in the US and around the world. A group of Chinese customs men surrounded by an angry American crowd; the LAPD trying to hold back the mob, struggling and eventually failing. The narrator took up the story. On that turbulent night, several rioters armed with clubs broke through, eventually killing two Chinese customs officers. The two men were lynched. The fallout was immediate. Washington acceded to Beijing’s request that the People’s Republic of China be allowed to protect its own people. The film ended with the White House spokesperson insisting that no more than ‘a light, private security detail’ would be sent from China to LA and the other ‘pearls’.

Maddy smiled a mirthless smile: everyone knew how that had turned out.

She was halfway through a reply to her former colleague – ‘Think that covers all the bases’ followed by a winking emoticon – when she looked up to see the editor striding in, three words into her sentence before she got through the door.

‘OK, we run the Walker picture tomorrow.’

Short, roundish and in her mid-fifties, her hair a solid, unapologetic white, Goldstein exuded impatience. Her eyes, her posture said, Come on, come on, get to the point, even before you had said a word. Still, Maddy risked a redundant question. ‘So not tonight?’

‘Correct. Walker remains unnamed tonight. Maybe tomorrow too. Depends on the re-act to the first piece.’

‘But—’

Goldstein peered over her spectacles in a way that drew instant silence from Maddy. ‘You have thirty minutes to make any final changes – and I mean final, Madison – and then you’re going to get the fuck out of this office, am I clear? You will not hang around and get up to your usual tricks, capisce?’

Maddy nodded.

‘No looking over the desk’s shoulder while they write the headlines, no arguing about the wording of a fucking caption, no getting in the way. Do we understand each other?’

Maddy managed a ‘Yes’.

‘Good. To recapitulate: the suck-ups on Gawker might think you’re the greatest investigative journalist in America, but I do not want you within a three-mile radius of this office.’

Maddy was about to say a word in her defence, but Goldstein’s solution actually made good sense: if a story went big, you needed to have a follow-up ready for the next day. Naming Walker and publishing his photo ID on day two would prove that they – she – had not used up all their ammo in the first raid. That Goldstein was perhaps one of a tiny handful of people on the LA Times she truly respected Maddy did not admit as a factor. She murmured a thank you and headed out – wholly unaware that when she next set foot in that office, her life – and the life of this city – would have turned upside down.

Chapter 2 (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

LA tended not to be a late night town, but the Mail Room was different. Downtown, in that borderland between scuzzy and bohemian, it had gone through a spell as a gay hangout; the Male Room, Katharine called it, explaining why she and her fellow dykes – her word – steered clear of it. Though now enjoying a wider clientele, it still retained some of that edgier vibe. Unlike plenty of places in LA, the kitchen didn’t close at eight and you didn’t have to use a valet to park your car.

Maddy found a spot between a convertible, the roof down even now, in January, and an extravagant sports car with tinted windows. The high-rollers were clearly in; maybe a movie star, slumming it for the night, plus entourage. She considered texting Katharine to suggest they go somewhere else.

The speakers in her car – a battered, made-in-China Geely that had been feeling its age even when she got it – were relaying the voices of the police scanner, announcing the usual mayhem of properties burgled and bodies found: the legacy of her days on the crime beat. She stabbed at the button, found a music station, wound up the volume. Let the beat pump through her while she used the car mirror to fix her make-up. Remarkably, despite the stress, she didn’t look too horrific. Her long, brown hair was tangled: she dragged a brush through it. But the dark circles under her green eyes were beyond cosmetic help: the concealer she dabbed on looked worse than the shadows.

Inside, she had that initial shudder of nerves, known to every person who ever arrived at a party on their own. She scanned the room, looking for a familiar face. Had she got here too late? Had Katharine and Enrica come here, tired of it and moved on? She dug into her pocket, her fingers searching out the reassurance of her phone.

While her head was down, she felt the clasp of a hand on her shoulder.

‘Hey, you!’

It took her a second to place the face, then she had it: Charlie Hughes. They’d met straight after college.

‘You look great, Maddy. What you doing here?’

‘I thought I was going to be celebrating. But I can’t see the people I’m meet—’

‘Celebrating? That’d be nice. I’m here to do the very opposite.’

‘The opposite? Why?’

‘You know that script I’ve been working on for, like, years?’ Charlie was a qualified, practising physician but that wasn’t enough for him. Ever since he’d been hired as a consultant on a TV medical drama, Charlie had become obsessed with making it as a screenwriter. In LA, even the doctors wanted to be in pictures. ‘The one about the monks and devils?’

‘Devil Monk?’

‘Yes! Wow, Maddy, I love that you remember that. See, it does have a memorable title. I told them.’

‘Them?’

‘The studio. They’ve cancelled the project.’

‘Oh no. Why?’

‘Usual story. Sent it to Beijing for “approval”. Which always means disapproval.’

‘What didn’t they like?’ God, she could do without this. She gazed over his shoulder, desperately seeking a glimpse of her friends.

‘Said it wouldn’t resonate with the Chinese public. It’s such bullshit, Maddy. I told them the most particular stories are always the most universal. If it means something to someone in Peoria, it’ll mean something to someone in Guangdong. The trouble is, if they won’t distribute, no one will fund. It’s the same story every time—’

She showed him glazed eyes, but it made no difference. He was off. So lost was he in his own tale – narrative, he’d call it – that he barely looked at her, fixing instead on some middle distance where those who had conspired to thwart his career were apparently gathered.

With an inward sigh, Maddy scoped the room. The group that caught the eye had occupied the club’s prime spot, perhaps a dozen of them gathering against the wide picture window that made up the far wall. Their laughter was loudest, their clothes sparkling brightest. The women were nearly all blonde – the exception was a redhead – and, as far as Maddy could see, gorgeous. Cocktails in hand, they were throwing their heads back in laughter, showing off their long, laboriously tonged hair. The men were Chinese, wearing expensive jeans and pressed white shirts, set off against watches as bejewelled and shiny as any trinket worn by the women. Princelings, she concluded.

She hadn’t realized the Mail Room had become a favoured hangout for that set, the pampered sons of the Chinese ruling elite who, thanks to the garrison and the attached military academy, had become a fixture of LA high society. Soon these rich boys would be the officer corps of the PLA, the People’s Liberation Army. PLAyers, the gossip sites called them.

The redhead was losing a battle to stay upright, tugged down by her wrist to sit on the lap of a man whose broad grin just got broader. He ran his hand down the woman’s back, resting it just above her buttocks. She was showing her teeth in a smile, but her eyes suggested she didn’t find it funny.

Maddy contemplated the tableau they made, the Princelings and their would-be princesses, their Aston Martins and Ferraris cooling outside. She was surprised this place was expensive enough for them. Now that they were here, it soon would be.

Charlie broke into his own monologue to wave hello at one of the PLAyers.

‘Is he an investor?’ Maddy asked, surprised.

‘I wish,’ Charlie sighed. ‘He’s a patient. The thing is …’

Suddenly she caught sight of Katharine standing at full stretch in a corner, her mouth making an O of delight, waving her to come over. Maddy gave Charlie a parting peck on the cheek, mumbled a ‘Good luck’ and all but fled to Katharine and Enrica, standing in a cluster with a few others around a small, high table congested with cocktails.

She slowed down when she saw him. What on earth was he doing here? She thought it was going to be a night with the girls, or at least men she hadn’t met, ideally gay. A night off. She gave Katharine a glare. But it was too late. He was already there, glass in hand, with his trademark embryonic smile. The beard was a new addition. When they lived together, she had always vetoed facial hair. But that was nearly nine months ago and now she saw it, she had to admit, it suited him.

‘Leo.’

‘Maddy. You look as stunning as ever.’

‘Don’t be slimy. Slimy never suited you.’

‘I was being charming.’

‘Yeah, well, charming never suited you either.’

‘How would you like me to be?’

‘Somewhere else?’ She lowered her voice. ‘Seriously, Leo. I thought we were going to give each other some space.’

‘Come on, Maddy. Let’s not ruin your big night.’

‘How do you know about that?’

He nodded towards Katharine, then took a sip of his drink. The budding smile had blossomed in his eyes, which never left her. They were a warm brown. In the right mood, when his interest, or better still his passion, was engaged, they seemed to contain sparks of light that would careen around the iris, bouncing off each other. They were brightening now.

‘What did she tell you? K, what did you—’

He reached for her wrist. ‘Don’t worry, she didn’t tell me anything. Just that you’ve reeled in a big one. Big enough to win a Huawei.’

‘Katharine doesn’t know what’s she’s talking about,’ Maddy retorted. But her shoulders dropped for the first time since she walked in here. She couldn’t hide it: she’d been thinking this story had the potential to win a Huawei prize from the beginning, before she’d even written a word. It had just what the judges liked: investigation, risk, its target corruption – at just that mid-level where its exposure did not threaten those at the very top. In more than one sleepless hour, she had worded the imaginary citation.

‘But you do, Maddy. And your face is telling me I’m right. You’ve landed a biggie.’

‘Don’t think you’re going to get me to tell you by flattering me, because it won’t work.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I know you, Leo Harris. I know all your tricks. Leaking my exclusive to everyone else, so it makes no impact—’

‘Not that again.’

‘Don’t worry. I’m not going to let you ruin this evening. I’m in a happy mood and I’m going to—’

‘OK, just tell me one thing.’

‘No.’

‘Does it affect the mayor in any way at all?’

‘No.’

‘Do I need to worry about it in any way at all?’

‘No.’ She paused. ‘Not really.’

‘Not really? And I’m supposed to be reassured by that?’

‘I mean, only in the sense that it’s happening in this city. And,’ she tilted her chin towards her chest and dropped her voice two octaves, ‘“Everything that happens in this city concerns—”’

‘“—concerns the mayor.” You see, Maddy, you do remember me.’

She said nothing but kept her eyes trained on his, brown and warm as a logfire. Seeing his pleasure, his tickled vanity, the thought came out of her mouth before she was even fully aware of it. ‘You’re such an asshole, Leo.’

‘Let me get you a drink.’

He turned and headed towards the bar, leaving Maddy to the gaze of Katharine, simultaneously quizzical and reproachful. Her friend and colleague, shorter, older and always wiser in such matters, was wordlessly asking her what the hell she was doing. By means of her eyes alone, she said, I thought we’d talked about this.

Leo was back, handing Maddy a glass. Whisky, not wine. I know you. She downed it in one gulp.

‘So,’ he began again, as if drawing a line under the previous topic. ‘I tell you what would win an instant Huawei.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Inside the campaign of the next Governor of the great state of California. Unprecedented access, fly on the wall. In the room.’

‘Are you offering me access to Berger’s campaign?’

‘No. I’m telling you what you could’ve had if you hadn’t broken up with me.’

‘Leo.’

‘All right. If you hadn’t decided we should have a “break”.’

‘We decided.’

‘Whatever. The point is, the mayor’s going to win, Maddy. He’s the most popular mayor in the history of Los Angeles.’

‘Well, I’ll just have to live with that, won’t I?’

He shrugged. Your loss.

They were joined just then by an improbably tall, slender woman perched on four-inch heels, wearing a dress which appeared to be slashed to the waist. Her skin was tanned and flawless. She was, Maddy decided, either a professional model or twenty-three years old. Or possibly both. When she spoke, it was with an accent that suggested an expensive education.

‘Aren’t you going to introduce me, Leo?’ The woman’s smile was wide and white. She gave Maddy a look of unambiguous warmth, as if they were destined to be friends for life.

‘This is Jade,’ Leo mumbled.

A long moment passed before Madison extended her hand and, realizing Leo was not going to do it for her, offered her own name. The three smiled at each other mutely before Madison finally turned and said under her breath, ‘Goodnight, Leo.’

He whispered back, ‘Don’t break my balls, Maddy.’

‘I don’t want to go anywhere near your balls, Leo. Have a good night.’

It was after midnight when Enrica announced that it was past her bedtime and that, unless Katharine wanted to deal with a woman no longer responsible for her actions, she needed to take her home. As Maddy followed them down the two flights of stairs, Katharine steadying her wife as she negotiated each step, she imagined what Leo would make of this sight: the lesbian couple, one Chinese-American, the other Latina, both committed Angelenos. It was a wonder he hadn’t cast them in a Berger campaign ad ages ago.

Now, in the dead of night, Maddy was experiencing what was, to her, the rare sensation of having done what she had been told. She had gone out and gone back home and not phoned the desk once. She had not bothered Howard or complained. She had not tried to tweak the odd sentence here and there. Nor had she exploited the fact that she knew all the relevant codes to go online and make the changes herself – an action that would squarely fall into the category defined by Goldstein as ‘her usual tricks’. Sure, she had looked at the website a dozen times, she had checked Weibo, which was now humming with the story. But, by her standards, she had exercised remarkable restraint.

She stood in the shower, unmoving, not washing, letting the water envelop her. Prompted, perhaps, by the sensation of warmth on her skin, she found herself tingling, her hands’ movements turning to caresses. Unbidden, came Leo – not the look of him so much as the sense of him, his presence. And the memory of his touch when he had been close to her, right here, in this shower, his body next to hers.

And yet she lacked the energy for what would ordinarily come next. What she wanted most of all was to fall into a deep, restoring sleep. But what else was new?

The water was turning cold. She stepped out, grabbed a towel and wandered into the living room. Or ‘living room’ as she would put it, in heavy quotes, were she writing a profile of somebody whose apartment looked like this. She assessed it now, with the detached eye of an observer. Outside lay the neighbourhood of Echo City, one part funky to two parts rundown. Inside, a large table, big enough to seat six or eight, entirely covered with paper, two laptops and a stack of filled notebooks, none arranged in any order except the one known exclusively to her. A couch, both ends taken up by piles of magazines and more papers, narrowing it into a seat for one.

Off to one side, through an open archway, the kitchen area, deceptively clean – not through fastidiousness so much as underuse. Even from here she could see there was a veneer of dust on the stove. The explanation lay in the trash can, filled almost exclusively by take-out cartons, deposited in a daily stream since she’d been on this story – and, she conceded to herself, long before.

For a moment Madison pictured how this place looked when she and Leo lived together. No tidier, but busier. Fuller. She enjoyed the memory, interrupted by that cut-glass accent. This is Jade.

She glanced down at her phone. So busy writing all afternoon and into the evening, she’d repeatedly ignored it when it rang. She’d not even checked her missed calls. But here they were: two from Howard, one from Katharine, both now obsolete, six from her older sister, Quincy, and one from her younger sister, Abigail.

She instantly thumbed Abigail’s name and hovered over the ‘Call’ button. It was late and Abigail was no night owl. On the other hand, she was a teacher at elementary school: blessed with a job that allowed her to turn off her cell when she went to bed. No risk of waking her up, no matter how late. Maddy perched on the end of the couch, still in her towel, and pressed the button. It rang six times and then voicemail, her sister’s voice so much younger, so much lighter, than her own.

No one leaves messages on these any more. But go on, you’ve come this far. Let me hear how you sound.

Maddy clicked off as soon as she heard the beep. She looked at the others, at Quincy’s six attempts. That suggested low-level incandescence rather than full-blown rage. Maddy wondered what she had done wrong to offend her older sister this time, what rule or convention or supposedly widely understood sisterly duty she had violated or failed to comprehend. She would not listen to the voicemail, she didn’t need to.

Her skin dry now, she followed the promise of sleep into the bedroom. Letting the towel fall off her, she slipped into the sheets, enjoying their cool. She had a dim awareness that she was following at least two elements of the recommended advice to insomniacs – a good shower and clean bedclothes. Such advice was in plentiful supply. She had been deluged with it over the years. Go to bed early, go to bed late. A bath, rather than a shower. Steaming hot or, better still, not hot. Eat a hearty meal, pasta is especially effective, at nine pm, or six pm, or noon, or even, in one version, seven am. A cup of warm milk. Not milk, whisky. Give up alcohol, give up wheat, give up meat. Stop smoking, start drinking. Start smoking, stop drinking. Exercise more, exercise less. Have you tried melatonin? Best to clear the head last thing at night by writing a to-do list. Never, ever write a to-do list: it will only set your mind racing. People are not clocks: they need to be wound down before sleep, not wound up. Thinking before bed was good, thinking before bed was very bad. One thing she knew for certain: contemplating all the myriad, contradictory methods of falling asleep could keep a person up at night.

Indeed, here she was, shattered, her arms, her hands, her eyes, her very fingertips aching for sleep – and still wide awake. None of it worked. None of it had ever worked. Pills could knock her out, but the price was too high: groggy and listless the next day. And she feared getting hooked: she knew herself too well to take the risk.

She had been up for twenty hours; all she was asking for was a few hours’ rest. Even a few minutes. She closed her eyes.

Something like sleep came, the jumble of semi-conscious images that, for a normal person, usually presages sleep, a partial dream, like an overture to the main performance. She remembered that much from her childhood, back when she could rest effortlessly, surrendering to slumber the instant her head touched the pillow. But the voice in her head refused to fall silent. Here it was now, telling her she was still awake, stubbornly, maddeningly present.

She reached for her phone, letting out a glum sigh: all right, you win. She checked the LA Times site again, her story still the ‘most read’. Then she clicked on the scanner app again, listening long enough to hear the police reporting several bodies found around town. One was not far from here, in Eagle Creek, another in North Hollywood.

Next, a long article on foreign policy: ‘Yang’s Grand Tour’, detailing how the man tipped to be China’s next president had just returned from an extended visit to the Middle East and analysing what this meant for the next phase of the country’s ambition. The piece was suitably dense. Sure enough, it came close to sending her off, her mental field of vision behind her lidded eyes darkening at the edges, like the blurred border on an old silent movie. The dark surround spread, so that the image glimpsed by her mind’s eye became smaller and smaller, until it was very nearly all black …

But she was watching it too closely, wanting it too much. She was conscious of her own slide into unconsciousness and so it didn’t happen. She was, goddammit, still awake. She opened her eyes in surrender.

And then, for perhaps the thousandth time, she opened the drawer by her bed and pulled out the photograph.

She gazed at it now, looking first at her mother. She would have been what, thirty-eight or thirty-nine, when this picture was taken. Christ, less than ten years older than Maddy was now. Her mother’s hair was brown, unstyled. She wore glasses too, of the unfashionable variety, as if trying to make herself look unattractive. Which would make a kind of sense.

Quincy was there, seventeen, tall, the seriousness already etched into her face. Beautiful in a stern way. Abigail was adorable of course, gap-toothed and smiling, aged six and sitting on Maddy’s lap. As for Maddy herself, aged fourteen in this photograph, she was smiling too, but her expression was not happy, exactly: it contained too much knowledge of the world and of what life can do.

She reached out to touch her earlier self, but came up against the right-hand edge of the picture, sharp where she had methodically cut it all those years ago, excising the part she didn’t want to see.

Later she would not be able to say when she had fallen asleep or even if she had. But the phone buzzed shortly after two am, making the bedside table shake. A name she recognized but which baffled her at this late hour: Detective Howe. A long-time source of hers from the crime beat, one who had been especially keen to remain on her contacts list. He called her once or twice a month: usually pretending to have a story, occasionally coming right out with it and asking her on a date. They had had lunch a couple of times, but she had never let it go further. And he had certainly never called in the middle of the night. One explanation surfaced. The sweatshop must have reported her for assault and Jeff was giving her a heads-up. Funny, she’d have thought they’d have wanted to avoid anything that would add to the publicity, especially after—

‘Madison, is that you?’

‘Yes. Jeff? Are you all right?’

‘I’m OK. I’m downstairs. You need to let me in. Your buzzer’s broken.’

‘Jeff. It’s two in the morning. I’m—’

‘I know, Madison. Just let me in.’ He was not drunk, she could tell that much. Something in his voice told her this was not what she had briefly feared; he was not about to make a scene, declaring his love for her, pleading to share her bed. She buzzed him in and waited.

When he appeared at her front door, she knew. His face alone told her: usually handsome, lean, his greying hair close-cropped, he now looked gaunt. She offered a greeting but her words sounded strange to her, clogged. Her mouth had dried. She noticed that she was cold. Her body temperature seemed to have dropped several degrees instantly.

‘I’m so sorry, Madison. But I was on duty when I heard and I asked to do this myself. I thought it was better you hear this from me.’

She recognized that tone. She was becoming light-headed, the blood draining from her brain and thumping back into her heart. ‘Who?’ was all she could say.

She saw Jeff’s eyes begin to glisten. ‘It’s your sister. Abigail. She’s been found dead.’

Chapter 3 (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

Jeff waited while she threw on the first clothes she could find before leading her to his car. He spoke throughout, telling her what he knew but she digested almost none of it. The only words she heard were the ones that replayed themselves over and over. It’s your sister. Abigail. She’s been found dead.

She was plagued by pictures of Abigail as a child. No matter how hard she tried, she could not see her sister as an adult. One image recurred more than any other: Abigail aged five or six, clutching the doll Maddy herself had once played with, that had, like everything else, been handed down from sister to sister to sister. And in her head, variations on a sentence that would not quite form itself: I let you down, Abigail. I let it happen again. It was never meant to happen again.

They had been driving less than ten minutes when Maddy suddenly sat bolt-upright, heart pounding. It took a moment for her to understand. Even if only for a few seconds, she had fallen asleep. Microsleeps, they called them. They happened to all insomniacs. She knew she was especially vulnerable after a shock; it could prompt her system to shut down. It had happened once in college, after some jerk she had fallen for dumped her, the pain sending her into brief unconsciousness.

Arriving at LAPD headquarters helped. Like a muscle memory, she knew how to walk and talk and carry herself here. She shook off Jeff’s attempts to guide her like the walking wounded, a hand on her waist. She made for the entrance, determined to function like Madison Webb, reporter.

Later she would struggle to remember the exact sequence of those next few hours, even though individual moments were etched in her memory. She remembered pleading with Jeff, asking him to pull whatever strings he could to break the usual protocol and allow her to visit the coroner’s office. Once there, she would never forget the grey-white sheet pulled back to reveal the frozen mask of her sister’s face, her lips a faded purple now, though Maddy had been told they were cold and blue when Abigail’s housemate had found her. Nor would she forget the way the doctor on duty had lifted her sister’s right arm, as casually as if it were the limb of a mannequin, gesturing to a fresh needle mark. And she would never forget his words, dully announcing to her the provisional verdict based on the state of the body when found: that the deceased had died of a drugs overdose, specifically caused by a massive injection of heroin into the bloodstream.

A silent, glared rebuke from Jeff had prompted the physician to apologize for his use of ‘the deceased’ about a woman who until a few hours ago had only ever been known as Abigail – a vital, joyful, beautiful force of nature. But there was no room in Maddy’s heart for anger about that. She was too numb to feel anything as direct as anger. Besides, she had covered enough murders to know that that was how death worked. You could be energetic, smart and sexy, an Olympic athlete or a Nobel-prize-winning genius, but it made no difference: within a moment you became meat on a slab. The staff in the coroner’s office spoke and acted the way they did because that was all they were looking at. They couldn’t see Abigail. They could only see a corpse.

Finally, Jeff ensured Madison got to meet the detective assigned to the case, Barbara Miller, a former partner of his. Brisk and businesslike, she gave them an initial briefing, describing the way Abigail’s body had been discovered: lying straight on the floor, on her back. An initial, brief search of the apartment could not confirm any forced entry. There were a few marks on the neck and back, but nothing that suggested a struggle.

It was past four in the morning when Maddy left, Jeff still at her side.

‘Thank you,’ she said, her voice a whisper.

‘You don’t have to thank me. You’ve just had the most terrible shock a person can have.’

‘I don’t believe it, you know.’

‘I know. It’s impossible to take in.’ He opened the passenger door for her, touching her elbow as he eased her into the seat.

‘I mean, I don’t believe it. Not a single fucking word of it.’

‘Of what?’

‘What your friend the detective was implying. In there.’

‘What was she implying?’

‘Come on, Jeff. No “confirmed” sign of forced entry. “Nothing to suggest a struggle.” I used to write that shit. We all know what it means. It means your friend thinks this was an “accident”.’ Maddy indicated quote marks with her eyebrows.

‘I don’t—’

‘I’ve seen that look you guys get when you talk about this stuff. She’s made up her mind that this was some kind of druggie sex game that went wrong.’

‘She didn’t say that.’

‘She didn’t have to. No forced entry, no struggle: it means consent. But I’m telling you, I know my sister, Jeff. I know who she is. She teaches elementary school, for Christ’s sake. She is not a fucking junkie.’

Jeff said nothing, so Maddy said it for him. ‘She was murdered, Jeff. Not killed by accident. Murdered. Someone murdered my baby sister.’

Then the words she thought but did not say out loud: I will find out who did this to you, Abigail. I broke one promise to you, but I will not break this one.

Chapter 4 (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

She woke from two hours of not-quite sleep – the fitful dozing that was often the closest she got to rest – with a momentary pause. It lasted less than a second, the most fleeting delay before she realized that the sense of a great, grave weight sunk onto her chest was not the product of a dream that would slip away, but of memory. She had remembered what had happened in the night, and her spirit sank with the recognition that it was no illusion or confusion, but real. Abigail was dead. She had not been able to save her.

She had refused Jeff Howe’s offer to sleep on her couch, which meant she had to drive herself to Quincy’s house in Brentwood. The long downhill ride along Huntley Avenue, the twists and turns, made her nauseous. Though she suspected that had less to do with the winding road – which was, in fact, remarkably free of the potholes that were standard in all but the richest, and usually expat Chinese, neighbourhoods of Los Angeles – and more to do with sickening anticipation of the duty that faced her.

The dashboard clock told her it was just before seven. Quincy would be up now, getting the kids ready for school.

She walked around the single BMW – an SUV – in the driveway. That meant Mark was already at the office. Some role in finance she struggled – or, rather, had not bothered – to understand. The dawn start was becoming rarer in LA these days: most began work later and carried on into the evening, so they could be on Beijing time. But it was a relief. She would need to be alone with Quincy.

She pressed the doorbell once and waited. She could hear her nephews squabbling, then her sister’s voice: ‘Juanita! Will you get that?’

The live-in maid; Maddy had forgotten about that. It still surprised her, the notion of anyone in her family being able to afford staff. When they grew up under the same roof, they could afford nothing.

The door opened to reveal Juanita’s pursed lips. Suddenly, and for the first time, Maddy thought of what she looked like: sleepless and in stained jeans with a sweater holed below the armpit. Was the Mexican-Catholic maid judging her appearance – or would she have got that look of disapproval no matter how she was dressed, thanks to a sustained campaign of propaganda from her employer?

‘Hello, Juanita,’ she managed, stepping inside. ‘Is Quincy around?’

‘We’re in here!’ her sister called out, her voice full of capable good cheer, the mom busy with her brood.

Maddy thought of asking Juanita to call Quincy out so they could speak alone, but thought better of it. So, bracing herself, she entered the kitchen that was as big as her entire apartment, large enough for the boys to be throwing a softball to each other in one area, their play barely disturbing their sister as she sat, eating cereal, at the breakfast bar. Quincy was stationed at what she called ‘the island’, making waffles.

‘Hi, Aunt Maddy,’ said the younger of the two boys, raising a mitt in greeting. His child’s smile stabbed at her heart. He was not much older than Abigail in the photograph.

Quincy looked up from the stove. ‘What happened to you? You look awful.’

Maddy moved over to her sister, dropping her voice. ‘We need to talk.’

‘I know,’ Quincy said, pulling at a wide drawer which noiselessly slid out to offer a vast range of cutlery. ‘That’s why I’ve been calling you. You know Mom has an appointment today, don’t you? At Cedar Sinai? Mark arranged it, with a specialist he knows. The thing is, I can’t take her. And it’s very much your turn, isn’t it? Why don’t you put these on the table? It’s so nice to see you. The kids haven’t seen you for ages.’ She handed her three plates and a small jug of maple syrup.

Maddy took them and put them straight down. ‘Quincy, it’s not that. It’s something terrible. We have to talk. Away from here.’

Into the vast living room, the silent black of the enormous TV screen that filled one wall reflecting them as they faced one another. Quincy’s brow was furrowed into a frown that said: What have you donenow?

‘It’s Abigail. The police called me in the middle of the night. She was found … They found her. She’s dead, Quincy.’

‘What?’

‘Don’t make me say it again.’

‘What are you talking about? I saw her on Sunday. She was here. She had lunch with us.’

‘They say it was a heroin overdose.’

‘Heroin? Abigail? Why would you say these things, Maddy? What’s wrong with you?’

‘I wish it wasn’t true. But I’ve seen … I’ve seen her. I was there a few hours ago, at the coroner’s office. It’s not a mistake.’

Once Quincy surrendered to the truth, she crumpled. As she did so, she instantly managed to find what had eluded Maddy all night: tears. Quincy held her arms open to be hugged by her younger sister, and they stood together, Maddy’s face growing wet from tears that were not her own.

‘You should have told me,’ were the first words Quincy managed.

‘I couldn’t do it over the phone.’

‘You should have come here earlier. I should have known.’

‘I couldn’t wake you up in the middle of the night. It would have terrified the children.’

‘It wasn’t right that you had to know this on your own, Maddy.’ After a few seconds, she spoke again. ‘And where was she?’

‘Like I said, in her apartment.’

‘No. I mean where?’

Maddy hesitated, picturing the image supplied to her at the coroner’s office and now seared into her mind: of Abigail, laid out on the floor. She should tell her. Quincy had a right to know. If Maddy had had to endure it, then they both should. Quincy had even said as much, that it was wrong for Maddy to carry this knowledge alone. Instead she said, ‘I don’t know. I’m not sure.’

At that, Quincy started sobbing again. Her son, Brett, was calling for her.

‘I’m really sorry, but there’s something I need to ask you,’ Maddy began. ‘About Abigail.’

Quincy stood up. ‘I’m going to go over to Mom’s now. I think we should go together.’

‘No. I can’t.’

‘What do you mean, you “can’t”?’

‘I can’t, Quincy.’

‘Don’t tell me you’re going to work. Jesus.’

‘Of course I’m not! For God’s sake. But I need to find out what happened to Abigail. None of it—’

‘Are you kidding? Let the police do that. Right now, you need to be with your family.’

‘I can’t do it, Quincy. I’m not going over there.’

‘Christ, Maddy. I don’t understand you at all, do you know that? At a time like this, your place—’

‘Look, just tell me. Did Abigail do drugs? Is that possible?’

‘Abigail? Abigail? I can’t believe you’d even ask that. Of course not.’

‘OK. Because what this means—’

‘Where would she even get drugs from? She didn’t mix in those kind of circles. And nor do I.’

‘What the fuck is that supposed to mean?’

‘Shhh. The children!’

‘No.’ Madison raised her voice louder, deliberately shouting out the word most likely to anger her sister. ‘What. The. FUCK is that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing, Maddy. Nothing. We’re all in shock. Ignore it, just ignore—’

‘Are you saying that I mix in those kind of circles, that I hang out with junkies? Is that what you’re saying? You can be a real shabi sometimes, you know, Quincy.’

‘How dare you use that language in this house!’

‘I can’t believe it. You’re blaming me!’

‘I’m not. Of course I’m not, Maddy. I’m just saying that you, you know, sometimes showed Abigail a more urban lifestyle than—’

‘More urban?What the hell is that supposed to mean? You mean because I don’t live in Crestwood fucking Hills with an SUV and a Merc?’

‘I think you should leave. I need to tell our mother that her daughter is dead.’

That stopped Maddy cold. She felt the rage ebb, leaving only exhaustion behind. ‘I’m sorry, Quincy. I’m not thinking straight. I’m just so …’ The sentence faded away.

Quincy looked at her with eyes that were raw. ‘OK. But you’re meant to be this great investigator, so brilliant at finding out the truth. But you don’t even know the people right in front of you, do you? You think you’re this big media star, Maddy, but guess what: you don’t always know everything. Not about me. Not about Mom.’ She paused, considering whether to continue. ‘Not even about Abigail.’

Chapter 5 (#uda5d8073-74b2-5eb3-9de4-9548ed7144a4)

She felt an extra rebuke in the fact that she didn’t have a key. Quincy probably had one, entrusted to her by Abigail in case of emergency. If Abigail had locked herself out or gone on vacation without turning the air-con off, who was she going to call? Madison didn’t blame her younger sister. Truth is, she’d have done the same in her position: rely on the one you can rely on.

You don’t always know everything. The words had stung her, replaying themselves as she had driven away from Quincy. So typical that, even now, her elder sister had managed to find a way to make Maddy feel excluded, as if she were somehow on the edge of the family, not privy to a knowledge shared by the other three women. Occasionally, Maddy felt that way, somehow lacking a clear place in the sibling line-up. Quincy was the eldest, Abigail the youngest but what was she? The middle sister? There wasn’t even a name for that.

In her head and even, for one moment, out loud in the car – alone in the driving seat – Madison had rehearsed her comeback. Truth is, Quincy, it’s you who doesn’t know everything. In fact, Quince, you know nothing. Thanks to us, you never did. You don’t have the slightest idea what happened that day, do you?

It was then that it struck her. With Abigail gone, and her mother in the state she was in, Madison was the only one left who knew. The only one left who remembered. The sensation of it left her queasy, as if she were at a great height looking down, her knees ready to buckle. It was like that thing they taught her in college, when she did a philosophy class: if a tree falls in the forest, and no one hears it, does it make a sound? If you are the last living soul to remember an event, did it even happen?

She considered the elevator but took the stairs, emerging onto the third floor to see the familiar yellow-and-black tape, barring her path to Abigail’s front door. There was no one around to enforce it, but Madison halted all the same. The door was ajar and there were voices coming from inside. Madison stared at the door frame, noticing some scarring close to the lock. Leaning in, she could see that a very small part of the surround had splintered, so that two or three painted wood shards jutted forward. Was that fresh damage or had it been done weeks earlier? She could not be sure. An initial, brief search of the apartment could not confirm any forced entry.

‘Hello?’ she called out, still on the wrong side of the police tape. The voices inside stopped. A few moments later, the door opened wider to reveal a young, fair-haired police officer bulked out by his uniform. Over his shoulder, four paces back, stood Abigail’s room-mate, Jessica. When she had first met her, whenever that was, Madison had marvelled at her bouncing hair and California Girl energy; she and Abigail looked as if they’d walked out of an orange juice commercial. But now Jessica’s shoulders were rounded and her hair was limp.

‘I’m Abigail Webb’s sister,’ Madison said, replying to the man’s unspoken question. ‘I won’t touch anything,’ she added as she lifted the tape and walked through the front door. By way of confirmation, Jessica stepped forward and opened her arms. Madison let herself be hugged, unsure whether she was receiving solace or administering it.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Jessica whispered, her cheeks wet against Maddy’s hair.

‘I’m sorry it was … I’m sorry you had to be here when …’

Once they had parted, Madison stepped back and looked at Jessica. She seemed crushed, as if the weight that had fallen on her had been physical. The police officer hovered nearby. They were still no more than a yard from the front door.

Maddy didn’t want to ask her sister’s friend to say it all over again, to make her re-live the moment of horror from several hours earlier. But she did, all the same.

Jessica started talking. ‘I walked in, put on the light and there she was. Lying on her back. She was still and she looked … so strange.’ Jessica’s voice faltered. ‘Her lips were blue. And her hair was real clammy.’

‘Did you know straight away that she was dead?’ Maddy said.

‘I wasn’t sure. At first I thought maybe she was breathing. Like tiny, faint breaths. I put my face by her mouth, to see if I could feel anything. And maybe I did. But it was just once. I waited and I didn’t feel it again. And she was so cold …’ Jessica’s chin began to tremble.

Maddy pressed on. ‘And you called the police right away?’

‘Not right away. I tried talking to her. You know, “Abigail, wake up. It’s me.” I might have slapped her, I can’t remember for sure. Her cheek was so cold.’

They talked for a moment or two longer when the police officer interrupted them. ‘Miss?’ He was looking at Jessica. ‘Do you know this gentleman?’

They both turned around to see an older man, his face covered by a smog mask, filling the door frame.

‘Daddy,’ Jessica said, moving towards him. Only then did Madison notice the overnight bag packed by the front door.

Jessica turned around and said, ‘I’m sorry, Madison. But my parents say it’ll be best for me if I leave town for a few days. They think I need to be home.’

‘Of course,’ Maddy said, attempting to smile. ‘Thanks, Jess.’ She had heard Abigail refer to her that way, but it sounded wrong coming from her. As Jessica followed her father out of the door – explaining to him that he didn’t need to wear the mask indoors – Madison called out to her once more. ‘I’m sorry it had to be you.’ Maddy knew as she said it that it could hardly have been anyone else. Certainly not her: she hadn’t been inside this apartment for months. It might even have been a year.

Once Jessica and her father had gone, the police officer turned to Madison and murmured a quiet ‘OK’, as if to say this visit had no doubt been tough but her time was nearly up.

‘I want to go into my sister’s room.’

‘I got very strict instructions, Miss. I’m not—’

‘I know about your instructions and I know the rules. I’m allowed in, so long as you’re present at all times to make sure I don’t remove anything. The place has been photographed and dusted for prints already, right?’

‘Yes, but have you checked this with—’

‘If you have any problems at all, call the Chief of Police. Tell him this is what Madison Webb has requested.’

It was a gamble, but a low-risk one. She had met Doug Jarrett a few times, though he was hardly a contact: he’d been appointed to the top job just as she was leaving the crime beat. For all that, she reckoned her name was well-enough known around the LAPD that had this officer called her bluff and telephoned headquarters – which he wouldn’t – she’d be OK.

He dipped his head in assent and she led the way, passing the living area and kitchen until she pushed open the door to the room that belonged to Abigail.

She stepped inside and was hit instantly by a wave of love and nostalgia that almost floored her. In just a few seconds, she was flooded by all things Abigail. On the bed were a couple of ethnic-style cushions Abigail had picked up on a trip to Santa Fe during her sophomore year. In the corner, the guitar she had taken up as a wannabe hippie in the eighth grade: Maddy only had to glance at it to hear again the sound of her sister strumming, out of time, to ‘Nowhere Man’. On the wall, the familiar collage of postcards of recent art exhibitions. On the night table, a copy of the latest novel by the young Nigerian literary sensation whom Maddy had heard interviewed on NPR in the middle of the night. The book was opened and face down, suggesting that Abigail – unlike all the journalist bullshitters Maddy knew – was actually reading it. The bed was rumpled, each crease a reminder that not long ago a living, breathing person had slept in it.

The room too was messy, a pile of exercise clothes and underwear in one corner. On the desk was a pile of children’s exercise books: all yellow, each one methodically laminated by hand. She opened one to see an infant’s scrawl.