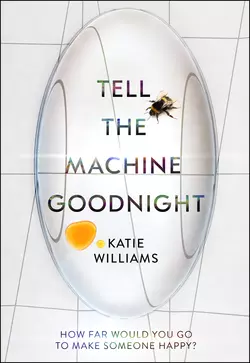

Tell the Machine Goodnight

Katie Williams

‘Philosophical, funny, cleverly structured, unpredictable’ Gabrielle ZevinIf a machine could offer a prescription for happiness but you might not like the results would you take the test?Eat more tangerines. Divorce your wife. Cut off your right index finger. The Apricity machine’s recommendations are often surprising, but they’re 99.97% guaranteed to make you happier. Pearl works for Apricity – meaning happiness is her job – but her teenage son Rhett seems more content to be unhappy, and refuses to submit to the test. Is Pearl failing as a mother and in her job – and does she even believe in happiness any more?Warm, witty and utterly charming, Tell the Machine Goodnight is where A Visit from the Goon Squad meets Where’d You Go Bernadette.

Copyright (#u9c91ed89-a8b4-553f-a81d-e1e137c3f56f)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Katie Williams 2018

Cover design by Andrew Davies/HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Jacket imagery by Andrew Davies. Bee images © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Katie Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008265038

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008265052

Version: 2018-05-30

Dedication (#u9c91ed89-a8b4-553f-a81d-e1e137c3f56f)

For Uly and Fia

Contents

Cover (#u548b2270-00cb-56aa-bbe8-388d4bfefbbd)

Title Page (#u48242f7d-17b8-50c8-8063-b07092e89c05)

Copyright

Dedication

1. THE HAPPINESS MACHINE (#u626ba3de-ceda-5f88-bd0b-f36d1cccb295)

2. MEANS, MOTIVE, OPPORTUNITY (#udc77a3d6-dfa8-5368-8ec8-082c3c3b78dd)

3. BROTHERLY LOVE (#u95ad17eb-c287-5eb2-be50-559a54aa4c1c)

4. SUCH A NICE AND POLITE YOUNG MAN (#litres_trial_promo)

5. MIDAS (#litres_trial_promo)

6. ORIGIN STORY (#litres_trial_promo)

7. SCREAMER (#litres_trial_promo)

8. BODY PARTS (#litres_trial_promo)

9. THE FURNITURE IS FAMILIAR (#litres_trial_promo)

10. TELL THE MACHINE GOODNIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Katie Williams

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_06ce6bd0-bd4c-582f-bc59-6ae9f4280a99)

The Happiness Machine (#ulink_06ce6bd0-bd4c-582f-bc59-6ae9f4280a99)

Apricity (archaic): the feeling of sun on one’s skin in the winter

The machine said the man should eat tangerines. It listed two other recommendations as well, so three in total. A modest number, Pearl assured the man as she read out the list that had appeared on the screen before her: one, he should eat tangerines on a regular basis; two, he should work at a desk that received morning light; three, he should amputate the uppermost section of his right index finger.

The man—in his early thirties, by Pearl’s guess, and pinkish around the eyes and nose in the way of white rabbits or rats—lifted his right hand before his face with wonder. Up came his left, too, and he used its palm to press experimentally on the top of his right index finger, the finger in question. Is he going to cry? Pearl wondered. Sometimes people cried when they heard their recommendations. The conference room they’d put her in had glass walls, open to the workpods on the other side. There was a switch on the wall to fog the glass, though; Pearl could flick it if the man started to cry.

“I know that last one seems a bit out of left field,” she said.

“Right field, you mean,” the man—Pearl glanced at her list for his name, one Melvin Waxler—joked, his lips drawing up to reveal overlong front teeth. Rabbitier still. “Get it?” He waved his hand. “Right hand. Right field.”

Pearl smiled obligingly, but Mr. Waxler had eyes only for his finger. He pressed its tip once more.

“A modest recommendation,” Pearl said, “compared to some others I’ve seen.”

“Oh sure, I know that,” Waxler said. “My downstairs neighbor sat for your machine once. It told him to cease all contact with his brother.” He pressed on the finger again. “He and his brother didn’t argue or anything. Had a good relationship actually, or so my neighbor said. Supportive. Brotherly.” Pressed it. “But he did it. Cut the guy off. Stopped talking to him, full stop.” Pressed it. “And it worked. He says he’s happier now. Says he didn’t have a clue his brother was making him unhappy. His twin brother. Identical even. If I’m remembering.” Clenched the hand into a fist. “But it turned out he was. Unhappy, that is. And the machine knew it, too.”

“The recommendations can seem strange at first,” Pearl began her spiel, memorized from the manual, “but we must keep in mind the Apricity machine uses a sophisticated metric, taking into account factors of which we’re not consciously aware. The proof is borne out in the numbers. The Apricity system boasts a nearly one hundred percent approval rating. Ninety-nine point nine seven percent.”

“And the point three percent?” The index finger popped up from Waxler’s fist. It just wouldn’t stay down.

“Aberrations.”

Pearl allowed herself a glance at Mr. Waxler’s fingertip, which appeared no different from the others on his hand but was its own aberration, according to Apricity. She imagined the fingertip popping off his hand like a cork from a bottle. When Pearl looked up again, she found that Waxler’s gaze had shifted from his finger to her face. The two of them shared the small smile of strangers.

“You know what?” Waxler bent and straightened his finger. “I’ve never liked it much. This particular finger. It got slammed in a door when I was little, and ever since …” His lip drew up, revealing his teeth again, almost a wince.

“It pains you?”

“It doesn’t hurt. It just feels … like it doesn’t belong.”

Pearl tapped a few commands into her screen and read what came back. “The surgical procedure carries minimal risk of infection and zero risk of mortality. Recovery time is negligible, a week, no more. And with a copy of your Apricity report—there, I’ve just sent that to you, HR, and your listed physician—your employer has agreed to cover all relevant costs.”

Waxler’s lip slid back down. “Hm. No reason not to then.”

“No. No reason.”

He thought a moment more. Pearl waited, careful to keep her expression neutral until he nodded the go-ahead. When he did, she tapped in the last command and, with a small burst of satisfaction, crossed his name off her list. Melvin Waxler. Done.

“I’ve also recommended that your workpod be reassigned to the eastern side of the building,” she said, “near a window.”

“Thank you. That’ll be nice.”

Pearl finished with the last prompt question, the one that would close the session and inch her closer to her quarterly bonus. “Mr. Waxler, would you say that you anticipate Apricity’s recommendations will improve your overall life satisfaction?” This phrasing was from the updated training manual. The question used to be Will Apricity make you happier? but Legal had decided that the word happier was problematic.

“Seems like it could,” Waxler said. “The finger thing might lower my typing speed.” He shrugged. “But then there’s more to life than typing speed.”

“So … yes?”

“Sure. I mean, yes.”

“Wonderful. Thank you for your time today.”

Mr. Waxler rose to go, but then, as if struck by an impulse, he stopped and reached out for the Apricity 480, which sat on the table between them. Pearl had just last week been outfitted with the new model; sleeker than the Apricity 470 and smaller, too, the size of a deck of cards, the machine had fluted edges and a light gray casing that reflected a subtle sheen, like the smoke inside a fortune-teller’s ball. Waxler’s hand hovered over it.

“May I?” he said.

At Pearl’s nod, he tapped the edge of the Apricity with the tip of the finger now scheduled to be amputated in—confirmations from both HR and the doctor’s office had already arrived on Pearl’s screen—a little over two weeks. Was it Pearl’s imagination or did Mr. Waxler already stand a bit taller, as if an invisible yoke had been lifted from his shoulders? Was the pink around his eyes and nose now matched by a healthy flush to the cheek?

Waxler paused in the doorway. “Can I ask one more thing?”

“Certainly.”

“Does it have to be tangerines, or will any citrus do?”

PEARL HAD WORKED AS A CONTENTMENT TECHNICIAN for the Apricity Corporation’s San Francisco office since 2026. Nine years. While her colleagues hopped to new job titles or start-ups, Pearl stayed on. Pearl liked staying on. This was how she’d lived her life. After graduating college, Pearl had stayed on at the first place that had hired her, working as a nocturnal executive assistant for brokers trading in the Asian markets. After having her son, she’d stayed on at home until he’d started school. After getting married to her college boyfriend, she’d stayed on as his wife, until Elliot had an affair and left her. Pearl was fine where she was, that’s all. She liked her work, sitting with customers who had purchased one of Apricity’s three-tiered Contentment Assessment Packages, collecting their samples, and talking them through the results.

Her current assignment was a typical one. The customer, the up-and-coming San Francisco marketing firm !Huzzah!, had purchased Apricity’s Platinum Package in the wake of an employee death, or, as Pearl’s boss had put it, “A very un-merry Christmas and to one a goodnight!” Hours after the holiday party, a !Huzzah! copywriter had committed suicide in the office lounge. The night cleaning service had found the poor woman, but hours too late. Word of the death had made the rounds, of course, both its cause and its location. !Huzzah!’s January reports noted a decrease in worker productivity, an accompanying increase in complaints to HR. February’s reports were grimmer still, the first weeks of March abysmal.

So !Huzzah! turned to the Apricity Corporation and, through them, Pearl, who’d been brought into !Huzzah!’s office in SoMa to create a contentment plan for each of the firm’s fifty-four employees. Happiness is Apricity. That was the slogan. Pearl wondered what the dead copywriter would think of it.

The Apricity assessment process itself was noninvasive. The only item that the machine needed to form its recommendations was a swab of skin cells from the inside of the cheek. This was Pearl’s first task on a job, to hand out and collect back a cotton swab, swipe a hint of captured saliva across a computer chip, and then fit the loaded chip into a slot in the machine. The Apricity 480 took it from there, spelling out a personalized contentment plan in mere minutes. Pearl had always marveled at this: to think that the solution to one’s happiness lay next to the residue of the bagel one had eaten for breakfast!

But it was true. Pearl had sat for Apricity herself and felt its effects. Though for most of Pearl’s life unhappiness had only ever been a mild emotion, not a cloud overhead, as she’d heard others describe it, surely nothing like the fog of a depressive, none of this bad weather. Pearl’s unhappiness was more like the wisp of smoke from a snuffed candle. A birthday candle at that. Steady, stalwart, even-keeled: these were the words that had been applied to her since childhood. And she supposed she looked the part: dark hair cropped around her ears and neck in a tidy swimmer’s cap; features pleasing but not too pretty; figure trim up top and round in the thighs and bottom, like one of those inflatable dolls that will rock back up after you punch it down. In fact, Pearl had been selected for her job as an Apricity technician because she possessed, as her boss had put it, “an aura of wooly contentment, like you have a blanket draped over your head.”

“You rarely worry. You never despair,” he’d gone on, while Pearl sat before him and tugged at the cuffs of the suit jacket she’d bought for the interview. “Your tears are drawn from the puddle, not the ocean. Are you happy right now? You are, aren’t you?”

“I’m fine.”

“You’re fine! Yes!” he shouted at this revelation. “You store your happiness in a warehouse, not a coin pouch. It can be bought cheap!”

“Thank you?”

“You’re very welcome. Look. This little guy likes you”—he’d indicated the Apricity 320 in prime position on his desk—“and that means I like you, too.”

That interview had been nine years and sixteen Apricity models ago. Since then Pearl had suffered dozens more of her boss’s vaguely insulting metaphors and had, more importantly, seen the Apricity system prove itself hundreds—no, thousands of times. While other tech companies shriveled into obsolescence or swelled into capitalistic behemoths, the Apricity Corporation, guided by its CEO and founder, Bradley Skrull, had stayed true to its mission. Happiness is Apricity. Yes, Pearl was a believer.

However, she was not so naïve as to expect that everyone else must share her belief. While Pearl’s next appointment of the day went nearly as smoothly as Mr. Waxler’s—the man barely blinked at the recommendation that he divorce his wife and hire a series of reputable sex workers to fulfill his carnal needs—the appointment after that went unexpectedly poorly. The subject was a middle-aged web designer, and though Apricity’s recommendation seemed a minor one, to adopt a religious practice, and though Pearl pointed out that this could be interpreted as anything from Catholicism to Wicca, the woman stormed out of the room, shouting that Pearl wanted her to become weak minded, and that this would suit her employer’s purposes quite well, wouldn’t it, now? Pearl sent a request to HR to schedule a follow-up appointment for the next day. Usually these situations righted themselves after the subject had had time to contemplate. Sometimes Apricity confronted people with their secret selves, and, as Pearl had tried to explain to the shouting woman, such a passionate reaction, even if negative, was surely a sign of just this.

Still, Pearl arrived home deflated—the metaphorical blanket over her head feeling a bit threadbare—to find her apartment empty. Surprisingly, stunningly empty. She made a circuit of the rooms twice before acknowledging that Rhett had, for the first time since he’d come back from the clinic, left the house of his own volition. A shiver ran through her and gathered, buzzing, beneath each of her fingernails. She fumbled with her screen, pulling it from the depths of her pocket and unfolding it.

“Just got home,” she spoke into it.

k, came the eventual reply.

“You’re not here,” she said. What she wanted to say: Where the hell are you?

fnshd hw wnt out came back.

“Be home in time for dinner.”

The alert that her message had been sent and received sounded like her screen had heaved a deep mechanical sigh.

Her apartment was in the outer avenues of the city’s Richmond District. You could walk to the ocean, could see a corner of it even, gray and tumbling, if you pressed your cheek against the bathroom window and peered left. Pearl pictured Rhett alone on the beach, walking into the surf. But no, she shouldn’t think that way. Rhett’s absence from the apartment was a good thing. It was possible—wasn’t it?—that he’d gone out with friends from his old school. Maybe one of them had thought of him and decided to call him up. Maybe Josiah, who’d seemed the best of the bunch. He’d been the last of them to stop visiting, had written Rhett at the clinic, had once pointed to one of the dark bruises that had patterned Rhett’s limbs and said, Ouch, so sadly and sweetly it was as if the bruise were on his own arm, the blood pooling under the surface of his own unmarked skin.

Pearl said it now, out loud, in her empty apartment.

“Ouch.”

Speaking the word brought no pain.

To pass the hour until dinner, Pearl got out her latest modeling kit. The kits had been on Apricity’s contentment plan for Pearl. She was nearly done with her latest, a trilobite from the Devonian period. She fitted together the last plates of the skeleton, using a tiny screwdriver to turn the tinier screws hidden beneath each synthetic bone. This completed, she brushed a pebbled leathery material with a thin coat of glue and fitted the fabric snugly over the exoskeleton. She paused and assessed. Yes. The trilobite was shaping up nicely.

When it came to her models, Pearl didn’t skimp or rush. She ordered high-end kits, the hard parts produced with exactitude by a 3-D printer, the soft parts grown in a brew of artfully spliced DNA. Once again, Apricity had been correct in its assessment. Pearl felt near enough to happiness in that moment when she sliced open the cellophane of a new kit and inhaled the sharp smell of its artifice.

Before the trilobite, she’d made a Protea cynaroides, common name king protea, the model of a plant that, as Rhett was quick to point out, wasn’t actually extinct. She could have grown a real king protea in the kitchen window box, the one that got weak light from the alley. But Pearl didn’t want a real king protea. Rather, she didn’t want to grow a king protea. She wanted to build the plant piece by piece. She wanted to shape it with her own hands. She wanted to feel something grand and biblical: See what I wrought? The king protea had bloomed among the dinosaurs. Think of that! This blossom crushed under their ancient feet.

The Home Management System interrupted Pearl’s focus, its soft librarian tones alerting her that Rhett had just entered the lobby. Pearl gathered her modeling materials—the miniature brushes, the tweezers with ends as fine as the hairs they placed, and the amber bottles of shellac and glue—so that all would be put away before Rhett reached the apartment door. She didn’t want Rhett to catch her at her hobby because she knew he’d smirk and needle her. Dr. Frankenstein? he’d announce in his flat tone, curiously like a PA system even when he wasn’t imitating one. Paging Dr. Frankenstein. Monster in critical condition. Monster code blue! Code blue! Stat! And while Rhett’s jibes didn’t bother Pearl, she also didn’t think it was especially good for him to be given opportunities to act unpleasant. He didn’t need opportunities anyway. Her son was a self-starter when it came to unpleasantness. No, she hadn’t thought that.

The sound of the front door, and a moment later, there Rhett was, each of the precious ninety-four pounds of his sixteen-year-old self. It had been cold outside, and she could smell the spring air coming off him, metallic, galvanized. Pearl looked for a flush in his cheeks like the one she’d seen in Mr. Waxler’s, but Rhett’s skin remained sallow; his visible cheekbones were a hard truth. Had he been losing weight again? She wouldn’t ask. After all, Rhett had arrived in the kitchen without prompting, presumably to say hello. She wouldn’t annoy him by asking him where he’d been or, to Rhett’s mind the worst question of them all, the one word: Hungry?

Instead, Pearl pulled out a chair and was rewarded for her restraint when Rhett sat in it with a truculent dip of the head, as if acknowledging she’d scored a point on him. He pulled off his knit cap, his hair a fluff in its wake. Pearl resisted the impulse to brush it down with her hand, not because she needed him to be tidy but because she longed to touch him. Oh how he’d flinch if she reached anywhere near his head!

She got up to search the cupboards, announcing, “I had a horrible day.”

She hadn’t. It’d been, at worst, mildly taxing, but Rhett seemed relieved when Pearl complained about work, eager to hear about the secret strangeness of the people Apricity assessed. The company had a strict client confidentiality policy, authored by Bradley Skrull himself. So technically, contractually, Pearl wasn’t supposed to talk about her Apricity sessions outside of the office, and certainly many of them weren’t appropriate conversation for a teenage boy and his mother. However, Pearl had dismissed all such objections the moment she’d realized that other people’s sadness was a balm for her son’s own powerful and inexplicable misery. So she told Rhett about the man, earlier that day, who’d been unruffled by the suggestion that he exchange his wife for prostitutes, and she told him about the woman who’d shouted at her over the simple suggestion of exploring a religion. She didn’t, however, tell him about Mr. Waxler’s amputated finger, worried that Rhett would take to the idea of cutting off bits of himself. A finger weighed, what, at least a few ounces?

Rhett grinned as Pearl laid the office workers bare, a mean grin, his only grin. When he was little, he’d beamed generously and frequently, light shining through the gaps between his baby teeth. No. That was overstating it. It had simply seemed that way to Pearl, the brilliance of his little-boy smile. “Moff,” he used to call her, and when she’d pointed at her chest and corrected, “Mom?” he’d repeated, “Moff.” He’d called Elliot the typical “Dad” readily enough, but “Moff” Pearl had remained. And she’d thought joyously, foolishly, that her son’s love for her was so powerful that he’d felt the need to create an entirely new word with which to express it.

Pearl went about preparing Rhett’s dinner, measuring out the chalky protein powder and mixing it into the viscous nutritional shake. Sludge, Rhett called the shakes. Even so, he drank them as promised, three times a day, an agreement made with the doctors at the clinic, his release dependent upon this and other agreements—no excessive exercise, no diuretics, no induced vomiting.

“I guess I have to accept that people won’t always do what’s best for them,” Pearl said, meaning the woman who’d shouted at her, realizing only as she was setting the shake in front of her son that this comment could be construed as applying to him.

If Rhett felt a pinprick, he didn’t react, just leaned forward and took a small sip of his sludge. Pearl had tried the nutritional shake herself once; it tasted grainy and falsely sweet, a saccharine paste. How could he choose to subsist on this? Pearl had tried to tempt Rhett with beautiful foods bought from the downtown farmers’ markets and local corner bakeries, piling the bounty in a display on the kitchen counter—grapes fat as jewels, organic milk thick from the cow, croissants crackling with butter. This Rhett had looked at like it was the true sludge.

Many times, Pearl fought the impulse to tell her son that when she was his age, this “disease” was the affliction of teenage girls who’d read too many fashion magazines. Why? she wanted to shout. Why did he insist on doing this? It was a mystery, unsolvable, because even after enduring hours of traditional therapy, Rhett refused to sit for Apricity. She’d asked him to do it only once, and it had resulted in a terrible fight, their worst ever.

“You want to jam something inside me again?” he’d shouted.

He was referring to the feeding tube, the one that—as he liked to remind her in their worst moments—she’d allowed the hospital to use on him. And it had been truly horrible when they’d done it, Rhett’s thin arms batting wildly, weakly, at the nurses. They’d finally had to sedate him in order to get it in. Pearl had stood in the corner of the room, helpless, and followed the black discs of her son’s pupils as they’d rolled up under his eyelids. After, Pearl had called her own mother and sobbed into the phone like a child.

“‘Jam something’?” she said. “Really now. It’s not even a needle. It’s a cotton swab against your cheek.”

“It’s an invasion. You know the word for that, don’t you? Putting something inside someone against their will.”

“Rhett.” She sighed, though her heart was hammering. “It’s not rape.”

“Call it what you want, but I don’t want it. I don’t want your stupid machine.”

“That’s fine. You don’t have to have it.”

Even though he’d won the argument, Rhett had afterward closed his mouth against all food, all speech. A week later he’d been back in the clinic, his second stint there.

“School?” she asked him now.

She fixed her own dinner and began to eat it: a small bowl of pasta, dressed with oil, mozzarella, tomato, and salt. Anything too rich or pungent on her plate and Rhett’s nostrils flared and his upper lip curled in repulsion, as if she’d come to the table dressed in a negligee. So she ate simply in front of him, inoffensively. The ascetic diet had caused her to lose weight. Pearl’s boss had remarked that she’d been looking good lately, “like one of those skinny horses. What are they called? The ones that run. The ones with the bones.” Fine then. Pearl would lose weight if Rhett would gain it. An unspoken pact. An equilibrium. Sometimes Pearl would think back to when she was pregnant, when it was her body that fed her son. She’d told Rhett this once, in a moment of weakness—When I was pregnant, my body fed you—and at this comment he’d looked the most disgusted of all.

But this evening, Rhett seemed to be tolerating things: his nutritional shake, her pasta, her presence. In fact, he was almost animated, telling her about an ancient culture he was studying for his anthropology class. Rhett took his classes online. He’d started when he was at the clinic and continued after he’d returned home, never going back to his quite nice, quite expensive private high school, paid for, it was worth noting, by the Apricity Corporation he disdained. These days, he rarely left the apartment.

“These people, they drilled holes in their skulls, tapped through them with chisels.” There was fascination in Rhett’s flat voice, a PA system announcing the world’s wonders. “The skin grows back over and you live like that. A hole or two in your head. They believed it made it easier for divinity to get in. Hey!” He slammed down his glass, fogged with the remnants of his shake. “Maybe you should suggest that religion to that angry lady. Tap a hole in her head! Gotta bring your chisel to work tomorrow.”

“Good idea. Tonight I’ll sharpen its point.”

“No way.” He grinned. “Leave it dull.”

Pearl knew she must have looked startled because Rhett’s grin snuffed out, and for a moment he seemed almost bewildered, lost. Pearl forced a laugh, but it was too late. Rhett pushed his glass to the center of the table and rose, muttering, “G’night,” and seconds later came the decisive snick of his bedroom door.

Pearl sat for a moment before she made herself rise and clear the table, taking the glass last, for it would require scrubbing.

PEARL WAITED UNTIL an hour after the HMS noted Rhett’s light clicking off before sneaking into his bedroom. She eased the closet door open to find the jeans and jacket he’d been wearing that day neatly folded on their shelf, an enviable behavior in one’s child if it weren’t another oddity, something teenage boys just didn’t do. Pearl searched the clothing’s pockets for a Muni ticket, a store receipt, some scrap to tell her where her son had been that afternoon. She’d already called Elliot to ask if Rhett had been with him, but Elliot was out of town, helping a friend put up an installation in some gallery (Minneapolis? Minnetonka? Mini-somewhere), and he’d said that Valeria, his now wife, would definitely have mentioned if Rhett had stopped by the house.

“He’s still drinking his shakes, isn’t he, dove?” Elliot had asked, and when Pearl had affirmed that, yes, Rhett was still drinking his shakes, “Let the boy have his secrets then, as long as they’re not food secrets, that’s what I say. But, hey, I’ll schedule something with him when I’m back next week. Poke around a bit. And you’ll call me again if there’s anything else? You know I want you to, right, dove?”

She’d said she knew; she’d said she would; she’d said goodnight; she hadn’t said anything—she never said anything—about Elliot’s use of her pet name, which he implemented perpetually and liberally, even in front of Valeria. Dove. It didn’t pain Pearl, not much. She knew Elliot needed his affectations.

Ever since they’d met, back in college, Elliot and his cohort had been running around headlong, swooning and sobbing, backstabbing and catastrophizing, all of this drama supposedly necessary so that it could be regurgitated into art. Pearl had always suspected that Elliot’s artist friends found her and her general studies major boring, but that was all right because she found them silly. They were still doing it, too—affairs and alliances, feuds and grudges long held—it was just that now they were older, which meant they were running around headlong with their little paunch bellies jiggling before them.

The pockets of Rhett’s jeans were empty; so was the small trash basket beneath his desk. His screen, unfolded and set on its stand on the desk, was fingerprint locked, so she couldn’t check that. Pearl stood over her son’s bed in the dark and waited, as she had when he was an infant, her breasts filled and aching with milk at the sight of him. And so she’d stood again over these last two difficult years, her chest still aching but now empty, until she was sure she could see the rise and fall of his breath under the blanket.

After Rhett’s first time at the clinic, when treatment there hadn’t been working, they’d taken him to this place Elliot had found, a converted Victorian out near the Presidio, where a team of elderly women treated the self-starvers by holding them. Simply holding them for hours. “Hug it out?” Rhett had scoffed when they’d told him what he must do. At that point, though, he’d been too weak to resist, too weak to sit upright without assistance. The “treatment” was private, parents weren’t allowed to observe, but Pearl had met the woman, Una, who had been assigned to Rhett. Her arms were plump and liver-spotted with a fine mesh of lines at elbow and wrist, as if she wore her wrinkles like bracelets, like sleeves. Pearl held her politeness in front of her as a scrim to hide the sudden hatred that gripped her. She hated that woman, hated her sagging, capable arms. Pearl had sat here in this apartment, imagining Una, only twenty-two blocks away, holding her son, providing what Pearl should have been able to and somehow could not. Once Rhett had regained five pounds, Pearl had convinced Elliot that they should move him back to the clinic. There he’d lost the five pounds he’d gained and then two more, and though Elliot kept suggesting returning him to the Victorian, Pearl had remained firm in her refusal. “Those crackpots?” she said to Elliot, pretending this was her objection. “Those hippies? No.” No, she repeated to herself. She would do anything for her Rhett, had done anything, but the thought of Una cradling her son, as he gazed up softly—this was what Pearl couldn’t bear. She would hold Una in reserve, a last resort. After leaving the Victorian, Rhett was back in the hospital again and then the terrible feeding tube. But it had worked, eventually it had. Pearl had eked out her son’s recovery pound by pound. Was that where Rhett had been this afternoon? Had he gone to see Una? Had he needed her arms?

A subtle shift of the bedcovers as Rhett’s chest rose, and Pearl slipped out of the room. If she were to sit for Apricity again, she wondered if there’d be a new item listed on her contentment plan: Watch your son breathe. Though, in truth, this practice didn’t make her happy so much as stave off a swell of desperation.

THE NEXT MORNING, the web designer was late for their follow-up appointment. When she finally arrived, she entered in a huff, which Pearl mistook for more of yesterday’s outrage. But once the woman had taken her seat and unwound a long red scarf from her neck, the first thing she did was apologize.

“You probably won’t believe this,” she said, “but I hate it when people yell. I’m not one to raise my voice.”

The woman, Annette Flatte, made her apology in a practical manner with no self-pity or shuffling of blame. She wore the exact same outfit she had the day before, a white T-shirt and tailored gray slacks. Pearl imagined Ms. Flatte’s closet full of identical outfits, fashion an unnecessary distraction.

“Did they tell you about what happened after the Christmas party?” Ms. Flatte said. “Why they brought you in?”

Pearl made a quick calculation and decided that Ms. Flatte would not be the type of person who would consider feigned ignorance a form of politeness. “Your coworker who killed herself? Yes. They told me at the outset. Did you know her?”

“Not really. Copywriting, Design: different floors.” Ms. Flatte opened her mouth, then closed it again, reconsidering. Pearl waited her out. “Some of them are joking about it,” Ms. Flatte finally said.

Pearl was already aware of this. Two employees had made the same joke during their sessions with Pearl: Guess Santa didn’t bring her what she wanted.

“It’s tacky.” Ms. Flatte shook her head. “No. It’s unkind.”

“Unhappiness breeds unkindness,” Pearl said dutifully, one of the lines from the Apricity manual. “Just as unkindness breeds unhappiness.” She reached for something else to say, something not in the manual, something of her own, but the landscape was razed, barren. There was nothing there. Why was there nothing there?

“They’re scared,” she finally said.

“Scared?” Ms. Flatte snorted. “Of what? Her ghost?”

“That someday they might feel that sad.”

Ms. Flatte stared at the scarf in her lap, combing its fringe. When she spoke, it was in a rush: “She wrote something for me once, a little line of copy, or actually poetry. She left it on my desk my first week here.”

“What did it say?”

Ms. Flatte bent down to the bag at her feet. Pearl could see the bones of her skull through the close crop of her hair, could see the curve and divot where spine and skull met. Pearl pictured fitting these pieces together, turning the tiny screws. Ms. Flatte came back up with a pocketbook, and from its coin compartment she extracted a slip of paper. Pearl took the slip carefully between two fingers. It was printed with a computer font designed to imitate hasty cursive.

You will take a long trip and you will be very happy, though alone.

“I looked it up,” Ms. Flatte said. “It’s from an old poem called ‘Lines for the Fortune Cookies.’ And see? Doesn’t it look like the little paper you get inside the cookie? Apparently she did it for everyone on their first week, chose a different line from a different poem. To welcome them. No one else told you about how she did that?”

“They didn’t say.”

Ms. Flatte pressed her lips together.

“The truth is, you were right,” Ms. Flatte said. “Or your machine was anyway. I do need something.” She laid heavily on the last word. “I don’t know about religion. I was raised to distrust it. But … something. This morning—” She stopped.

“This morning?” Pearl prompted.

“The bus takes me through Golden Gate Park, and there’s always these old people out on the lawn doing their tai chi. Today I got out and watched them for a while. That’s why I was late to meet you. Do you think … could that be it? For me, I mean? Do you think that’s what the machine could have meant?”

Pearl pretended to consider the question, already knowing she would deliver the standard reply. “Try and see. With Apricity, there’s no right and wrong. There’s just what works for you.”

Ms. Flatte smiled suddenly and broadly, her whole face changed by it. “Can you imagine?” She laughed. “All those old Chinese people … and me?”

She thanked Pearl, apologizing once more for her outburst the day before, before bending to gather and rewind her long red scarf.

“Ms. Flatte,” Pearl said as the woman stood to go, “one more thing.”

“Yes?”

“Would you say that you anticipate Apricity’s recommendations will improve your overall life satisfaction?”

“What’s that?”

“Will you be happier?” Pearl asked. “Will you … will you be happy?”

Ms. Flatte blinked, as if surprised by the question; then she nodded once, curt but sure. “I think I will.”

Pearl was surprised to feel a flare of … was it disappointment? She watched the gentle nape of Ms. Flatte’s neck as the woman walked from the conference room, and she felt a sudden and ferocious wish that Ms. Flatte would turn around and, as she had the day before, begin to shout.

WHEN SHE RETURNED HOME, Pearl wondered if she’d find the apartment empty again. But no, there was Rhett, in his room at the computer, doing schoolwork, just as he was supposed to be.

“Hey,” he said without turning around.

Pearl was so focused on the delicate wings of his hunched shoulders that it took her a moment to spot the half-finished trilobite set out on his desk.

“Is it okay I took it?” He’d turned and followed her gaze.

“Of course. But it’s not finished yet. It still needs its details: antennae, legs, a topcoat of shellac.” Then, on impulse, “You could help me finish it.”

“Yeah, maybe.” He’d already turned back around.

“This weekend?”

“Maybe.”

Pearl lingered. She wished she could make her departure now, on this promising note, but they had to get it done before Rhett ate (drank) his dinner.

“Rhett? It’s weigh-in day.”

“Yeah, I know,” he said tonelessly. “Just let me finish my paragraph.”

He met her, minutes later, in the bathroom, where he shrugged off his sweatshirt and put it into her waiting hand.

“Pockets,” she said.

He gave her a look but obliged without comment, turning them inside out. It had been his trick in the past to load his pockets with heavy objects. When Pearl nodded, Rhett stepped on the scale. She was not tall, but he was taller than her now, taller still as he stood on the scale. Taller, but he weighed less than her, and she was not a large woman. Rhett stared straight ahead, leaving Pearl to gaze at the number on her own. She felt it, that number. Higher or lower, she felt it every week, as if it affected her body in reverse, lightening her or weighing her down.

“You’ve lost two pounds.”

He stepped off the scale without comment.

“That’s not good, Rhett.”

“It’s a blip.” “It’s not good.”

“You’ve seen me. I’m drinking my shakes.”

“Where were you yesterday?”

He closed his mouth slowly, defiantly. “Nowhere that has anything to do with that number.”

“Look. I’m your mother—”

“And I’m sorry for that.”

“Sorry? Don’t be sorry. I just want you to—” She stopped. What was she saying? She just wanted him to what? She sounded as if she were reading from some sort of script. “We’ll do an extra weigh-in. On Saturday. If it’s just a blip, it’ll be back to normal then.”

“Okay.”

“If it’s not, we’ll call Dr. Singh and adjust the recipe for your shake. He may want us to come in.”

“I said okay.”

DINNER WAS SILENT, except for the deliberate sound of Rhett slurping his shake. Pearl comforted herself by thinking that this was the exact sort of thing teenage boys did, acted purposely obnoxious to get back at you for scolding them. After dinner, she got out a new modeling kit, this one for a particular species of wasp, and began the armature, twisting the wire filaments with her pliers. As usual, Rhett had disappeared to his room directly after dinner. To study for a test, he’d said. Pearl was lost in her work with the wasp, only emerging when she heard a scrape on the tabletop to find Rhett there, returning the trilobite. He stood, as if waiting, his hand still on the model. She couldn’t read his expression.

“It’s fine if you keep it in your room,” she said. “I mean, I’d like you to.”

“But you need to finish it? You said that.”

On impulse, she reached out and grabbed his wrist. It was so thin! You didn’t really know until you’d touched it. She could have circled it with her thumb and finger easily. There was still a bit of the fur on his skin, the silky translucent hair that his body had grown to keep him warm when he’d been at his skinniest. Lanugo, the doctors had called it. They both stared down at her hand on Rhett’s wrist. She knew he was probably horrified; he hated being touched, especially by her. But she couldn’t make herself release it. She stroked the fur with her finger.

“It’s soft,” she murmured.

He didn’t speak, but he also didn’t pull away.

“I wish I could replicate it on one of my models.” She’d spoken without thinking, a bizarre and horrible thing to say.

But Rhett stayed and let her stroke his wrist for a moment longer. Then, something more, he touched it—improbably—to her cheek before extricating himself.

“Goodnight,” he said, and she thought she heard him add, “Moff.” Then he was gone; again, the sound of his bedroom door. Pearl stared at the unfinished trilobite, imagined it swimming through the dark oceans without the benefit of its antennae to guide it, a compact little shell, deadened and blind. Surely he hadn’t said “Moff.”

Pearl stayed up late again, pretending to work on the wasp, but really making unguided twists in the wire, ending up with an improbable creature, one that had never existed, could never exist; evolution would never allow it. She imagined that the creature existed anyway, imagined it covered with fur, with feathers, with scales, with cilia that reacted to the slightest sensation. When the light to Rhett’s room finally shut off, she went down the hall and got a cotton swab from her bag.

Rhett slept on his back with his lips slightly parted, the effect of the sleeping pill she’d crushed into his shake when fixing his dinner. It was easy to slip the swab into his mouth, to run it against his cheek without causing a murmur or stir. Easier than perhaps it should have been, this act that Rhett and the company, both, would consider a violation. The Apricity 480 sat on the kitchen table, small and knowing. Pearl approached it, the cotton swab in her grip. She unwrapped a new chip, the little slip of plastic that would deliver her son’s DNA to the machine.

You will take a long trip and you will be very happy, though alone.

She loaded the chip, fit it into the port, and tapped the command. The Apricity made a slight whirring as it gathered and tabulated its data. Pearl leaned forward. She unfolded her screen and peered into its blank surface, looking to find her answer there, now, in this last moment before it began to glow.

(#ulink_e62117f0-444c-59ef-9924-b1f110c3c42f)

Means, Motive, Opportunity (#ulink_e62117f0-444c-59ef-9924-b1f110c3c42f)

CASE NOTES 3/25/35

Saff says it’s funny to think of someone hating her enough to do what they did. She says it’s funnier to think that she herself was there while they were doing it, that she already knows the solution to this mystery; she just can’t remember what it is. She says that her body must remember—that the person’s fingers are printed on her skin, their voice in her eardrums, their reflection on the backs of her eyes—and maybe her body could tell her, if only she could get her brain to shut up and let it. She lifts her bracelets to her elbow and lets them drop back down to her wrist, where they fall against each other, chiming. “You think I’m crazy, don’t you, Rhett?” she says, adding, “Tell me the truth.”

“I don’t think you’re crazy,” I say. “But then most people wouldn’t consider my sense of what’s crazy to be particularly reliable.”

Saff crinkles her nose. Does she think we’re flirting? If she does, I let her go on thinking it because it’s less trouble that way.

And I don’t tell Saff the truth: that my body knows more than my brain does, too, that that’s why I starve it. Instead, I tell her a lie. I tell her that I can help her.

CASE NOTES 3/26/35

THECRIME

On the night of 2/14/35, Saffron Jones (age 17) was dosed with “zom,” short for “zombie,” so named for the drug’s effects of short-term memory loss paired with extreme suggestibility. Basically, if you’re on zom, you’ll do whatever anyone tells you to and you won’t remember any of it afterward, won’t remember much of what came before it either, which is the nastiest part because you won’t remember who dosed you. While on zom, Saff was told to strip naked and recite conjugations of the French verbs dormir, manger, and baiser (respectively, “to sleep,” “to eat,” and “to fuck”). She was told to shave off her left eyebrow and to ingest half a bar of lemon soap. These events occurred in the basement of Ellie Bergstrom (age 18) during a party at Ellie’s house and were recorded on Saff’s screen. No one besides Saff is visible or audible in the video. As is typical with zom, Saff woke up the next morning with no memory of the previous night. She remembered leaving her house for Ellie’s party, that’s it. She thought she’d gotten drunk. She didn’t realize anything more had happened until she accessed Facebook and discovered the video posted to her account. It had 114 dislikes, 585 likes.

“IT COULD HAVE BEEN A LOT WORSE,” Saff tells me.

We’re sitting in her car in Golden Gate Park, pulled over on one of the access roads behind the flower conservatory. I can almost see the white spires of the conservatory through the treetops, but my clearest view is of the dumpster in the back where they throw out the flowers that have wilted and gone to rot.

“Saff. They made you eat soap.”

Saff showed me the video. (I don’t go on Facebook anymore.) In it, she took bite after bite of the thick bar of soap like it was a tea cake. Her pupils were huge and lavender in the dim basement light. (So were her nipples.) Her eyes weren’t dead, though, not zombified like you’d think. She has big, dark eyes, Saff does. And in the video, they glittered. Also, she smiled as she chewed. We think she must have been told not just to eat the soap, but to like eating it. I stared at her mouth so I wouldn’t look at her breasts, all too aware that the clothed Saff was sitting across from me, watching me as I watched her. In the video, the tip of her tongue darted out to collect a stray flake of soap from her bottom lip. Her lips parted, and a bubble formed between them, quivering like a word you can’t speak. Then she threw it all up, a foamy yellow torrent. After that, the video cut out.

Saff shrugs. “At least my eyebrow is growing back. Can you tell?” She’s penciled in the missing brow with care, but I can tell because it’s a slightly different shade of brown from the real one. “It could have been worse.”

“Are you sure it wasn’t? Are you sure you weren’t …?” Raped is what I’m not going to say.

“I think I could tell. It would have been … new.” I’m a virgin is what she’s not going to say.

Saff is sneaking looks at me, but this time it’s not because she’s trying to flirt. She’s embarrassed, either to tell me she’s a virgin or maybe just to be one. I want to tell her not to bother being embarrassed, not around me. When I left school last year, all the kids in our class had started declaring themselves straight, gay, bi, whatever. Me, I had nothing to declare. Because I was nothing. I am nothing. I’m not interested in any of it. The doctors say I would be if only I ate more, but they think every true part of me is just another symptom of my condition. What they don’t understand is that my condition is a symptom of me. That I am a stone buried deep in the ground, something that will never grow, no matter how good the dirt.

“You were, though.” I decide I’m going to say the word this time. “Raped.” And when I do, Saff ’s breath hisses out. “Even if you weren’t actually. They made you do those things. They forced you. I know how it is.”

“Yeah. Well. Everyone knows how it is because of that damn video.”

“No. I mean I know how it feels. To be forced.”

“Oh, Rhett,” Saff whispers. “Oh no.” And she’s misunderstood me. She thinks I mean that I was raped. What I mean is that the doctors shoved a feeding tube down my throat when I was too weak to resist. That my parents told them it was okay. That it felt like I was drowning. I let Saff misunderstand, though. I let her clasp my hand and stare at me with her big, dark eyes. Because I know that when people comfort you, they’re really just comforting themselves.

CASE NOTES 3/27/35, LATE MORNING

OPPORTUNITY

Opportunity holds no clues for us. Everyone in the class had the opportunity to dose Saff. Zom is taken transdermally. It’s loaded on a see-through slip of paper, like a scrap of Scotch tape. You press the paper to your bare skin—your arm, your palm, your thigh, your anywhere—and it dissolves into you. You can take it on purpose for the side effects: slowed time, heightened sense of smell, euphoria. Even though you won’t remember much of any of it the next day. Or you can get dosed without knowing it. A stranger’s hand on your bare shoulder as you push through the crowd, on your cheek pretending to brush away a stray eyelash, on the back of your hand in a show of sympathy.

At the clubs, everyone stays covered up: full-length gloves, turtlenecks, pants, high boots, even veils and masks. In fact, the more covered you are, the more provocative, because you’re saying that you might let a stranger touch you anywhere there’s cloth. Some kids will let bits of skin show through, peeks of upper arm, ankle, and neck. Not too much skin, though, just enough to stay vigilant over. You have to protect what you show.

Saff wasn’t covered up when she left her house. She was wearing a T-shirt and jeans and had left her sneakers at the door: bare arms, bare hands, bare neck, bare feet. So many vulnerabilities. But Saff wouldn’t have thought she was vulnerable. This was a party at Ellie’s, just like a hundred other parties at Ellie’s going back to her platypus-themed fifth-birthday party, an event all the same kids had attended, add me. Seneca Day School is exclusive, meaning tiny, designed for kids with parents in big tech. There are only twelve students in each graduating class. (Eleven in mine, since I left.) We’ve all known each other forever. We all trust each other.

Except of course we don’t. After all, where is there more distrust than in a small group of people trapped together for eternity? Old grudges; buried feelings; past mistakes; all those former versions of you that you could, in a larger school, run away from. Trust? You’d be safer in a crowd of strangers.

I EXPLAIN TO SAFF that we’ll solve her mystery by looking for three things: means, motive, and opportunity. I tell her that everything everyone does can be predicted by this trinity of logic: Are they able to do it? Do they have a reason to do it? Do they have the chance to do it?

“Everything everyone does?” Saff repeats with a raised eyebrow, her real eyebrow. “What if I did something, like, totally spontaneous?”

Her hand whips out and knocks over the saltshaker. We’re meeting in the diner across from school in Pac Heights. Salt cascades across the table, over the edge, soundlessly to the floor. The waitress glares at us.

“You’ve just proved my point,” I tell her. “Your arm works. That’s means. You wanted to challenge my theory. That’s motive. The saltshaker was right there in front of you. That’s opportunity.”

Saff considers this. “You helping me then. How is that means … whatever?”

“Well. I have the means because I’ve read about a thousand detective novels and because I’m smart. Opportunity is that you asked me to help. Also, I’m in school online, which means I don’t have adults watching over me all day.”

“And motive?” she says.

Because they forced a feeding tube down my throat, I could tell her. Because when I saw you again, you didn’t say how healthy I looked, I could tell her. Because kid-you knew kid-me, before all of this shit.

Instead I say, “Because I feel like it.”

Saff screws her mouth to one side. “For it to be an actual motive doesn’t there have to be, like, a reason?”

In response, I reach out and knock over the pepper shaker.

She laughs.

There’s movement in the diner window. Ellie and Josiah are there across the street, beckoning to Saff. They’re both on our list. Ellie is an obvious suspect. Because she would. That there is a true sentence: Ellie would. Whatever your proposition, Ellie would do it without hesitation. But Josiah? Josiah wouldn’t hurt anyone. He might stand there with his hands in his pockets and say, Hey. Come on, guys. Stop it. (And that’s almost worse, isn’t it?) But he wouldn’t actually do anything to anyone.

I haven’t seen Josiah in almost a year. He looks the same. Taller. That stupid thing adults always say, You look taller, as if that’s an accomplishment, and not just something your body does on its own, without your permission.

“Gotta go.” Saff leans forward like she’s going to kiss me on the cheek.

Across the street, Josiah squints, trying to make out who it is Saff is sitting with. I slouch down in the booth, and so Saff ’s kiss is delivered to the empty space where I just was.

“Don’t tell them you saw me,” I say.

CASE NOTES 3/27/35, AFTERNOON

MOTIVE

The Scapegoat Game started as a unit in Teacher Trask’s junior English. She assigned “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” “The Lottery,” The Hunger Games, Lord of the Flies, and other classics with a scapegoat theme. They even watched a Calla Pax movie, The Warm-Skinned Girl, where Calla Pax is sacrificed to a god living in an ice floe to stop planet heating and save the world. Saff says everyone got really into it, so much so that the class decided, without Trask’s knowledge, to test the scapegoat concept in real life. My former classmates charted out eleven weeks, for the eleven of them, each one signing up for a weeklong turn as scapegoat. Like in the stories, the scapegoat had to take everyone else’s abuse without comment or complaint. For that one week, ten were free to vent all their anger, frustration, pain, whatever, on the eleventh, knowing that the next week someone else—maybe you yourself—would become the scapegoat. They decided that made it fair.

SAFF COMES OVER AFTER SCHOOL to continue our conversation from the diner. When I swing open the door, she looks upset. Her eyes are pink. The inner edge of her penciled brow is smeared like she’s been rubbing at it. I have the impulse to reach up and touch it, that bare little arc of skin. I shove my hands in my pockets.

“Are your parents home?” she says.

I tell her no, that my mom is at work. And that my dad doesn’t live here anymore.

“Okay,” she says.

And I’m grateful she doesn’t say, I’m sorry, because then I don’t have to say, It’s okay. Or, I see him on weekends. Or, It’s better this way. Or any other of that divorce-kid bullshit.

“We have until six,” I say. “My mom usually gets home around then.”

Not that it’s against the rules to have Saff over. In fact, I’m pretty sure Mom would be delighted, which is precisely why I don’t want her to find Saff here. It’s too hard to have Mom hoping things about me. She got home before me yesterday, when I was at the park with Saff. Now she keeps looking at me, but she won’t ask where I was, and I won’t tell her. Not just out of stubbornness.

I’ve bought a tube of cookies and a couple sodas from the corner store in case Saff is hungry. There’s plenty of food in the kitchen, of course, but Mom will notice if any of it is missing, and she’ll think (hope) that I’m the one who’s eaten it. I offer the snacks to Saff like I haven’t bought them special. I even left them in the kitchen so that I can pretend to go in and get them from the cupboard. We take the food into my room.

Saff turns in a slow circle. I picture my room through her eyes: twin bed, rag rug, desk-chair-screen setup. No bullshit band posters or Japanese mech figurines to announce my unique storebought personality. I threw all that stuff in a box last year. Now the room is simple (bare, Mom says), pure (monkish, Mom says). The walls are its only distinction. Today they’re set to Victorian wallpaper, an exact replica of the wallpaper in the old BBC show Sherlock. On one wall there’s even the image of a fireplace, complete with ashtray and curling pipe.

I wait to see if Saff gets the joke, but she sinks down on the floor by my bed without comment. She slides out a couple cookies, then shakes the tube at me. When I say, “No thanks,” she doesn’t push it, doesn’t study me with meaningful eyes, doesn’t say, Are you sure? So I return the favor and don’t ask why she’s been crying.

Instead, I say, “Tell me more about the game.”

“Game?”

“The Scapegoat Game.”

She rolls her eyes and bites off half a cookie in one go. “Oh. That fucking thing.”

“Whose idea was it?”

“Whose do you think?”

“Ellie’s.”

She nods.

Popularity—who’s cool, who’s not, jocks, nerds, whatever—is, for Saff and me, something that exists only in movies about high school. When you have a class of twelve people, there really aren’t enough of you to divide up into cliques. Sure, there are some best friends, like Ellie and Saff, or like Josiah and me (used to be). There’re some couples, Ellie and Linus for a while, then Brynn and Linus, basically every girl and Linus. Except Saff. She’s never been with Linus. Though maybe she has this past year; I wouldn’t know, I’ve been gone. My point is, mostly everyone hangs out with everyone else.

There is one role, though, one rule: Ellie is always the leader. It’s been that way from our first year, back when Ellie would whip the dodgeball at you and then, when you cried over the burn it’d left on your leg, explain how that was just part of the game, explain it so calmly and confidently that you found yourself nodding, even though the tears were still rolling down your cheeks. That makes it sound like I think Ellie is a bad person. I don’t. In fact, the older I get, the more I think that Ellie’s got it right, that she knew at five what the rest of us wouldn’t figure out until our teens: the world is tough, so you’d better be tough right back.

“And so?” I say to Saff, because there’s always more to the story when Ellie is involved.

“And so, after Ellie comes up with the scapegoat idea, she even volunteers to go first. Which, if you think about it, is pretty smart because at first everyone is, you know, gentle. Warming up to it. Also, if you go first, you haven’t scapegoated anyone else yet, so they don’t have anything to pay you back for.” Saff pauses. “Do you think she actually plans this stuff out ahead of time?”

“I think Ellie has an instinct for weakness.”

“Well, that first week we didn’t do much—tugged Ellie’s hair, kicked the back of her chair in class, made her carry our lunch trays. Nothing really. I think she had fun. Actually, I know she did. The last day, she dressed up as Calla Pax, from that sacrifice-on-the-ice movie we watched. In, like, a sexy white robe. She looked great. Of course. Then, the next week, Linus went. The guys were rougher on him, but not in a mean way, if that makes sense? And you know how Linus is. Easy with it all. It felt like a game. Fun even. Like free. When you have permission to … if you can do whatever … sometimes it’s like …” She taps a thumb against her chest, then gives up trying to explain and takes another cookie. Her third. (I can’t help counting other people’s food.)

“But then it got bad. Each week, each new person. We kept upping it. Meaner. Rougher.”

“When did you go?”

“Last,” she says, smiling bitterly. “Like a fucking fool.”

She looks like she’s going to start crying again. I type some notes into my screen to give her a chance to get ahold of herself.

“‘An instinct for weakness,’” she mutters.

I look up from my screen. “I didn’t mean that you’re weak.”

“I don’t know. I feel pretty weak.”

“You’re not, though. That’s why they gave you zom. They had to make you weak. Which proves you’re not. See?”

She bites on her lip. “I haven’t told you about Astrid yet.”

“Astrid is weak.”

“Yeah, I know. She was scapegoat just before me.”

Astrid’s parents both work as lawyers for big tech, her mom for Google, her dad for Swink. For them, arguing is sport, which maybe partway explains the way Astrid is. If you’re someone who needs to explain why people are the way they are. In second grade Astrid used to brush her hair over her face. Right over the front of it until it covered everything right down to her chin. The teachers were constantly giving her hair bands and brushes and telling her how nice she looked in a ponytail. At Seneca Day, there’s a certain style the teachers are all supposed to use, “suggesting instead of correcting.” But finally one day, Teacher Hawley lost it and shouted, “Astrid, why do you keep doing that!” And all the rest of us looked to the back row where Astrid sat and here comes this little voice, out from behind all that hair: “Because I like it better in here.”

I still think about that. Because I like it better in here.

“We got carried away,” Saff says. “We thought because we’re such good friends that we could say anything, do anything, and it was safe.”

She goes quiet, so I prompt her: “Astrid.”

“I just rode her, Rhett. All week. I didn’t let up.” As she talks, she pushes up her sleeves like she’s preparing for hard work. “I knew it was bad, too. I knew she was going into the bathroom to cry during break. And that made me even harder on her. Talk about an instinct for weakness.”

“You’re saying Ellie put you up to it?”

“That’s the thing. She didn’t. It was me. All of it. I was way worse than the rest of them. Even Ellie probably thought I was going too far. Not that she’d ever stop anyone from going too far.” Saff shakes her head. “I didn’t know I could be like that.”

“And you think Astrid wanted to get back at you?”

Saff shrugs. “I’m the one crying in the bathroom these days, aren’t I?”

She looks so beyond sad. Which is maybe why I make the mistake of saying, “It’s been pretty bad, huh?”

And Saff starts crying right there in my room.

“It’s not the soap,” she says, through sobs, “though I still gag every time I have to wash my hands. It’s not the stupid eyebrow.” She touches it, rubbing away more of the pencil. “It’s not even that I was naked. It’s that everyone saw me. All the seniors. All the middle graders. The teachers. My friends’ parents. My parents’ friends. When they look at me now … well, mostly they won’t look at me. That, or they look at me really intensely, and I can practically hear them thinking to themselves, I’m looking her in the eye. I’m looking her in the eye.”

She puts her face in her hands. I watch her cry. I know I’m not going to hug her, know I’m not even going to pat her arm. But I feel like I should do something. So I take a cookie from the tube. So I bite it. It’s the first solid food I’ve had in over a year, and chewing feels funny. Saff looks up at the crunch. Her eyes are wide, like it’s some big deal, which makes me want to spit out the bite. Instead I take another bite. Then I pass it to her. She takes a bite and passes it back to me. We finish the whole cookie that way, bite by bite.

CASE NOTES 3/27/35, EVENING

MEANS

Any of our suspects could have found the means to dose Saffron Jones.

Linus Walz (age 17) deals recreational drugs, primarily LSD, X, and hoppit, but it wouldn’t be difficult for Linus to get zom, either for his own use or for a classmate. Ellie never confessed where she got the zom she was caught with last year, but it’s common knowledge that Linus got it for her.

Josiah Halu (age 16) is Linus’s close friend, and like Ellie, he could’ve asked Linus to get him the zom or even stolen it from Linus’s stash.

Of the four suspects, Astrid Lowenstein (age 17) seems the least likely to have been able to secure the drug, though she shouldn’t be ruled out on these grounds.

At this point, none of them can be ruled out. Any of them could have done it, even if it’s difficult to imagine any of them having done it. It’s difficult because they used to be my friends. I can’t allow my bias to blind me. One of them did do it. Sentimentality must be starved.

THAT WHOLE NIGHT, I keep thinking about Saff crying in my bedroom. For the first time since I left school, I almost wish I could be back at Seneca Day so that Saff would have someone there to, I don’t know, trust. Except, if I’d stayed at Seneca, I would’ve played the Scapegoat Game with the rest of them, I would’ve gone to Ellie’s party that night, and then I would’ve been just another one of Saff ’s suspects. I’m only able to help her because I’m here, on the outside.

I ask myself why I even care about helping Saff. Ask myself why I keep picturing her blotchy one-eyebrowed face. I mean it’s not like Saff cared about me. None of them did. After I left, a few emails, a handful of texts, a “get well” card some teacher undoubtedly bought and made them all sign. Linus and Josiah came by the apartment a few times, then just Josiah, then no one. Not that I wanted anyone to visit. Not that I answered any of their emails or texts. Then just last week, almost a year to the day that I’d left school, Saff texted me: I think you’re maybe the only person who hasn’t seen it yet. I need you to tell me you haven’t seen it yet. Please don’t have seen it.

It was the video. And, no, I hadn’t seen it yet. Saff and I met at the bus stop outside my building. We sat in the plastic rain shelter, even though it was sunny, and let bus after bus go by. She looked the same, Saff did, short crinkly hair; round face; sleeve of metal bracelets, like her own personal wind chimes. I’d never thought much about Saff; she was always Ellie’s friend, daffy and harmless, a sidekick, a tagalong. Ellie wasn’t here now, though. Saff had come to meet me by herself. And maybe she looked different after all. Maybe she looked harder. Braver.

She sat on the bench next to me and said, “Hey, Rhett.”

She didn’t say, You look better, or You’ve gained weight.

Which meant that I didn’t have to say, Yeah, I got fat again.

Which meant that I was able to say, “Hey, Saff.” Like we were just two normal people waiting for the bus.

I told Saff that she didn’t have to show me the video if she wanted there to be one person who hadn’t seen it. She said it was different because she was choosing to show it to me. She unfolded her screen and told me to check that the projection wasn’t on, then she watched me while I watched it. When I handed her screen back, I made sure not to glance at her body, made sure not to not glance at her body. What Saff said about the way everyone looks at her, I know about that. People do it to me, too.

The idea for how to help Saff comes to me that night in the middle of a calculus exam, and I’m so excited about it that I get the last question wrong on purpose because it’s taking too long to work out the numbers. I hit Submit on my screen and jump out of my seat. Mom is due back from work any minute, and if I don’t get it now, then I’ll have to wait until morning. Mom’s work just upgraded her machine a few weeks ago, and so if I’m lucky, the old model will still be in the hall closet waiting to be returned to the office. And it turns out that I am lucky because there it is sitting next to her rain boots: the Apricity 470. I pick it up and weigh it in my hand, that little silver box. And I forget that I hate it, hate Mom’s belief in it and its so-called answers. I ditch all my moral qualms. Because this is how I’m going to do it. This is how I’m going to figure out who dosed Saff.

CASE NOTES 3/28/35, AFTERNOON

FROM GROVER VS. THE STATE OF ILLINOIS CONCURRING OPINION

“Whether or not the Apricity technology can truly predict our deepest desires is a matter still under debate. What is certain, however, is that this device does not have the power to bear witness to our past actions. Apricity may be able to tell us what we want, but it cannot tell us what we have done or what we will do. In short, it cannot tell us who we are. It, therefore, has no place in a court of law.”

SAFF AND I DECIDE TO SPRING IT ON THEM, spring me on them. There’s a class meeting after school to come up with a proposal for the end-of-the-year trip. The only adult there will be Teacher Smith, a.k.a. “Smitty,” the junior class adviser, and Smitty insists on “student autonomy,” which means that during class meetings he sits across the hall in the teachers’ lounge grading papers. We can sneak in, me and Apricity, with no one the wiser.

“Let’s go through it again,” I say. We’re sitting in Saff ’s car at the far edge of the parking lot waiting for the meeting to start. “We’re focusing on four people: Linus.”

“Because he has access to zom,” Saff fills in.

“Ellie.”

“Because she could get zom and because she would do it.”

“Astrid.”

“Because I was a monster to her,” Saff says.

“And Josiah?” I phrase it like a question.

“Yeah. Josiah,” she agrees, but nothing else. She won’t tell me why she suspects him.

Is it because you two were together? I want to ask. The thought has been in my head all week. But I can’t ask, because then Saff might think that I care. Though maybe that’s why she’s not telling me. I should tell her not to worry about it, me caring. I should tell her that I don’t care. About her and Josiah. About her. About anything. I should tell her that.

Instead I say, “Have you ever thought it could be all of them? I mean, the whole class together?”

Saff turns to the window, blows on it, then erases the mark her breath has left. “Sure. But I don’t think about it for long. It’s too shitty to contemplate.”

“Sorry.”

She looks over, surprised. “Why are you sorry?”

“I don’t know. For saying it could be all of them.”

“But you’re right. It could be.”

“It won’t be all of them,” I say, though of course I don’t know that this is true.

“The only thing I’m sure of is it wasn’t you,” Saff says, holding my eye.

“Yeah. It wasn’t me.”

She flashes a smile, fleeting as the jangle of her bracelets. There and gone.

The meeting is about to start, so we go in.

Smitty does us one better than the teachers’ lounge. He actually goes out to sit in his car and (not-so-) secretly smoke. Saff enters the classroom first, while I wait in the hall. It turns out that I’m nervous. My heart is going at about a million. A few months ago, I would’ve had to sit down and put my head between my knees, but now I’m strong enough to keep standing. I guess that’s something anyway. The doctors would say that’s something. To stand when you need to stand. Strength. I count to thirty, then step into the room.

“Rhett!” Linus shouts, and suddenly, it’s a year ago, and I never left them. “My man!” He’s smiling big, his arms stretched wide in welcome. A couple of the girls, Brynn and Lyda, rush over to fuss at me. (“You look so good, so much better.” “Yeah, there’s, like, color in your cheeks.”) These two would make a project out of me if they could. Astrid gives a half wave, and Ellie calls out, “Hey, skinny,” causing a couple of the others to shoot her looks, which she ignores. Josiah doesn’t say anything until I catch his eye. As usual, his bangs are in dire need of a cutting. “Hey, man,” he says so softly I only know what the words are because I can read them on his lips.

The classroom is seminar style, so instead of desks there’s a conference table and swivel chairs. Brynn and Lyda guide me to the head of the table, where the teacher usually sits.

“Are you back?” Linus asks.

And it occurs to me that I could be. I could say yes and, just like that, be back with my class at Seneca Day just in time for my senior year. The school would let me. The doctors would, too. Mom would be overjoyed. But I look around at them, these too-familiar eleven faces, and I just can’t. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s nothing that any of them did, and it’s nothing that I think they would do. I just know that if I came back I’d stop eating again. And, look, I’m not saying I want to eat. But for the first time, I maybe want to want to.

Josiah is staring down at his lap. All the others are watching me. Saff has her lips parted like she’ll step in for me if I can’t answer.

“No. I’m doing a project for school,” I say. “Cyberschool,” I amend. And if there’s any disappointment that I’m not returning to Seneca Day, it’s whisked away by their excitement over the Apricity I set out on the table.

No one resists taking the Apricity. Everyone is willing to be, as Mom would say, swabbed and swiped. The only hint of hesitation comes from Ellie, who announces, “I don’t need to be told what makes me happy,” though she sucks on her cotton swab along with the rest of them. Ten times, I brush the cotton on a computer chip and fit the chip into the side of the machine, just like I’ve seen Mom do. And Saff and I lie to the class a second time, saying that my screen battery just ran out and that I’ll have to take it home to recharge it before I can get their results from the machine.

“So we’ll see you again?” Josiah says, a little stiffly. I can’t tell if this means that he wants to see me again or that he doesn’t.

Before I can answer, Smitty pops his head into the room, making a surprised face at seeing me there. “Rhett! What a surprise! If I’d known you were coming I would’ve baked you …” He trails off, embarrassed.

“A cake?” I finish the sentence for him. “Sorry, Smitty. Not hungry. Haven’t you heard? Never hungry.” And after an awkward pause, everyone laughs. Even me.

CASE NOTES 3/28/35, LATE AFTERNOON

SUSPECT APRICITY RESULTS

Linus: arrange fresh flowers, visit Italy, sing out loud

Josiah: put a warm blanket on your bed, spend time with your sister,

Astrid: take the night bus, drop math class, get a tattoo

Ellie: run ten miles a day, write poetry, don’t listen to your father

“I DON’T SEE ANYTHING SUSPICIOUS,” Saff says. “Do you?”

I shuffle through the results again, reluctant to tell her that I don’t see anything suspicious either. We’re sitting on the floor in my room, Saff with the tube of cookies again. She’s eating so frenetically I’ve lost count.

“I was hoping someone’s might say, Tell the truth, or Apologize to Saff,” she says through a mouthful of crumbs. “Isn’t that stupid?”

“No. That’s actually the kind of thing that happened when the police used Apricity in interrogations, you know, when that was still legal. It’s like the person’s guilt is what’s keeping them from being happy.”

“Well. I guess whoever did it must not feel guilty then,” Saff murmurs. “They must think I deserved it.”

“Yeah, maybe. But then again, whoever did it is pretty fucked up.”

She sighs. “What’d you get?”

“‘Get’?”

“On the Apricity?”

“I didn’t take it.”

“Yeah, but when you have?”

“I’ve never taken it.”

“What? Never? But your mom,” she says. “It’s, like, her job.”

I keep my eyes on the results. “Uh-huh. So?”

“So you’ve never even been curious?”

“I’m just not interested.”

“You’re not interested in happiness?”

“Yeah.” I look up at her. “Exactly.”

She narrows her eyes. “I’d think sad people would be the ones most interested in happiness.”

“I’m not sad.”

“Yeah,” she says, deadpan. “Me neither.”

We look at each other for a minute, but what is there to say? We’re both sad. So what.

“You know what’s funny?” I push our friends’ results at her. “What’s the first thing you think of when you look at this?”

“That I can’t imagine Linus arranging flowers?”

“Okay, but in general, looking at all of them, what do you think?”

She flips through the pages. “I don’t know. They don’t make much sense.”

“That’s what I mean,” I tell her. “Apricity results sound random. They don’t make sense. ‘Take the night bus.’ ‘Arrange fresh flowers.’ ‘Drop math class.’” I pause, then say, “‘Recite French verbs. Shave your eyebrow. Eat a bar of soap.’ The things you did on zom, it’s like someone made you do a reverse Apricity.”

“Oh.” Saff raises her hands to her mouth, and her bracelets clang. “I think maybe I took one.”

“An Apricity?”

“Yeah. Maybe.”

“You mean that night? You remember something?”

“Maybe,” she repeats, her eyes tracking back and forth as she tries to remember. “Maybe in an arcade?”

They have those remakes of the old fortune-teller machines with the papier-mâché Gypsy. You press your finger to a metal panel and the machine prints out a contentment plan. It’s not a real Apricity, though. There’s no DNA involved, no computing. It’s just a game.

“There’s an arcade on Guerrero, isn’t there?”

“Yeah. The Tarnished Penny.”

“Isn’t it just a couple blocks from Ellie’s house? Do you think you went there that night?”

“I told you. I don’t remember that night.” She brings her hands up higher, over her face, and I think of Astrid saying, I like it better in here. From behind her hands, Saff says, “Rhett. What did I do?”

CASE NOTES 3/29/35

Josiah’s Apricity results (in full):

Put a warm blanket on your bed.

Spend time with your sister.

Tell someone.

SO MAYBE I LIED TO SAFF. Because maybe it’s a clue, and maybe it’s nothing. Tell someone. This was Josiah’s last Apricity recommendation. I deleted it from his results before showing her. I rationalize the omission because the Apricity said, Tell someone, not Tell everyone. I rationalize it because I know I’ll do what’s right when it comes to Saff. And I know that sounds like some stupid hero-with-a-moral-code bullshit or whatever, but I also know that it’s true, that I’ll do right by her.