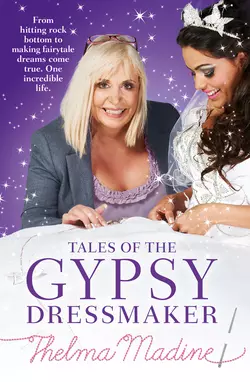

Tales of the Gypsy Dressmaker

Thelma Madine

Thelma Madine, star of Channel 4’s Big Fat Gypsy Weddings and fairy godmother of extravagant wedding dresses, reveals the drama, secrets and surprises involved in ten incredible traveller weddings.Through the tales of ten elaborate gypsy wedding dresses, Thelma Madine, trusted confidante and dressmaker extraordinaire, offers a window onto the world of traveller brides and their unbelievable celebrations.For Thelma’s young brides, a wedding dress is more than just a pretty white gown. For some it is a symbol of their fairytale-like hopes and dreams for the future, for others a mark of a long-standing friendship with a non-traveller they have welcomed into their community, and, for one small group, it is a sad reminder of day they know will never come.With each chapter based around the secrets and incredible truths hidden behind each different dress, Thelma’s second book is packed full of fascinating new stories. By turns laugh-out-loud funny and achingly sad, and brimming with hilarious anecdotes and larger-than-life characters, Thelma’s book will amaze, amuse and entertain.Beautifully designed and fully-illustrated throughout, it is crammed with glossy new photos, revealing never-before-seen dresses adorned with thousands of Swarovski crystals and hundreds of LED lights – an ideal gift for fans of Channel 4’s Big Fat Gypsy Weddings and Thelma’s Gypsy Girls.

Tales of the Gypsy Dressmaker

Thelma Madine

Dedication

I’d like to dedicate this book to the

travelling community.

You let me into your world and in turn

helped me to understand a little bit of your

culture. You opened my eyes to the

prejudices you face daily. You helped put me

where I am today.

Contents

Cover (#ulink_0e918c27-daad-5987-9080-ad88ff94a6c0)

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: The Pineapple and the Palm Tree

Introduction

1 The Tale of How It All Began

2 The Tale of the First Communion Dresses

3 The Tale of My First Big Fat Gypsy Wedding Dress

4 The Tale of a Love Gone Bad

5 The Tale of a Nightmare Come True

6 The Tale of Life Within Prison Walls

7 The Tale of the Motherless Child

8 The Tale of a Not So Happy Ever After

9 The Tale of the Unpaid Bill

10 The Tale of the Girl Who Dreamed of Being a ‘Swan Pumpkin’

11 The Tale of the Size 26 Bridesmaid

12 The Tale of the Bartering Brother

13 The Tale of the Dancing Kids

14 The Tale of the Groom Who Was Nicked at the Altar

15 The Tale of What Happened Next

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Picture Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

The Pineapple and the Palm Tree

‘I want you to make me a wedding dress like no one’s ever seen before.’

‘OK,’ I said, looking at the slim, blonde gypsy girl standing in front of me. ‘Have you got any ideas of the kind of dress you’d like?’

She’d made an appointment to come into my shop, Nico, in the centre of Liverpool, so I was expecting her. I was also expecting her request – all my traveller girls want to stand out, determined that their dress will be the biggest and the best, or both.

‘I want to be a palm tree,’ she said.

‘And I’m going to be a pineapple,’ piped up the girl who was with her and who I realised straight away was her younger sister, and one of the most enthusiastic bridesmaids I’d ever met. They were both pretty kids and I knew just by looking at them that they were from Rathkeale, the very wealthy gypsy community in Ireland. In Rathkeale the night-before outfits are just as important as the wedding dress. And these two were going all out.

‘A palm tree for the bride and a pineapple for the bridesmaid,’ I said, looking from one to the other. They were looking at me as though they had just asked me to make a wedding gown like Kate Middleton’s, their faces were dead straight, like any anxious bride and bridesmaid, determined that they had to look just right on the Big Day. ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘we can do that, no problem.’

‘Will anyone else have a dress like that?’ asked the young girl. ‘She’s really worried that there will be another bride who wants the same thing as her,’ she said, touching her sister’s arm, before turning to look at me again.

‘Oh, I think she’ll be safe with that one,’ I said, smiling at them.

I looked down at my sketchbook and started drawing.

Introduction

Now, the first thing everyone asks when they meet me is: are you a gypsy? So now’s my chance to put the record straight: no, I am not a gypsy. What I am is a woman from Liverpool who makes and designs wedding dresses. It just so happens that the people who have made my dresses some of the most recognised in the world are gypsies. And that’s why I’m now known, from Aberdeen to Auckland, as the Gypsy Dressmaker.

Nothing could have prepared me for the dramas that I have experienced since I started working with gypsies about fifteen years ago – and, believe me, what you’ve seen on TV is only the half of it.

And that’s one of the reasons that I was so keen to write this book – fans of Big Fat Gypsy Weddings are constantly asking me to tell them more about me and my gypsy stories. Because, beyond the cameras, since I was welcomed into the traveller community many years ago, I have been lucky enough to get a rare insight into what really goes on in their world and to share in their secrets and dreams, their highs and lows and, of course, their laughter. And, honestly, there has been a hell of a lot of that over the years.

The other thing that people are forever asking is: how did you end up working with gypsies in the first place? Well, I suppose it was a coincidence, but you could say that it was a twist of fate. You know, in the way that my mum used to say things like, ‘Everything happens for a reason,’ or ‘What’s for you won’t go by you.’

It was in 1996, when I had my dressmaker’s stall in Paddy’s Market in Liverpool, that my first traveller customer approached me. I didn’t even know she was a gypsy. I did realise, though, that there was something different about her because she looked very, very young. Too young, in fact, to ask me a strange question like ‘Can you make Gone With the Wind dresses?’

I mean, it’s not your run-of-the-mill request, is it? And it’s not the kind of thing that I imagine most dressmakers are normally asked for. The funny thing is, what that gypsy girl couldn’t have known that day, when she looked at all the ivory and white christening and Communion robes I had hanging up, was that that great 1930s film about Scarlett O’Hara and the American Civil War was one of the main reasons I wanted to be a seamstress in the first place. Since I was a little girl I had watched that movie a thousand times. And yet, up until then, I had never thought to actually make Gone With the Wind dresses.

So the idea that the girl had in her mind for how she wanted to dress her kids, and the kinds of dresses that I wanted to make, came together at Paddy’s that day and started what would eventually become a phenomenon.

I could never claim to know everything about gypsies and I’m not a spokesperson for travellers. It’s just that, like most people, I am fascinated by their world, and I really do feel lucky that I’ve been welcomed in by many of my customers as a friend. Not least because travellers’ tales are always packed full of drama, high emotion and laughs, and I’m part of their story now too.

And that brings me to another reason that I am so fond of the gypsies I know. About ten years ago I went through something that most of us fear – something that probably tops the list of things that you never, ever want to go through: I was sent to prison. And through it all, along with my friends and family, my gypsy customers supported me, and their support is something that I will never forget.

Of course, I know that some people will always judge me and my relationship with travellers – and they are free to do so – but if my time in prison taught me anything, it was not to judge others. And maybe that’s why I get along with the gypsies so well: I treat them the same way that I treat everyone else – simply taking them as I find them.

The past fifteen years that my gypsy customers have been coming to me to make their dresses have been some of the most interesting times of my life. And the fascinating stories that have grown from working with them have also provided the backdrop to my own life story, which I will be revealing in this book.

You see, like the gypsy girls, I also got married very young. I wanted the best wedding ever, the biggest cake, the most beautiful dress, and, most of all, to be happy ever after. Now we all know that, no matter how nice your life may turn out to be, happy ever after is just a dream, a fairytale. And no one knows that more than me. But then no one believes in fairytales more than a gypsy girl who is about to become a bride.

And, as the Gypsy Dressmaker, it’s my job to make her fairytale come true.

1

The Tale of How It All Began

I think it was around October. It was definitely 1996. And I will never forget it was winter because Dave, my partner, would always arrive at my flat early, it was always pitch black, and it was always bloody freezing. But I suppose we got used to it as every week was the same – we’d be out loading the van at five a.m., as careful as we could with the little ivory and white christening gowns and boys’ suits that were beginning to make my stall one of the most talked-about on Paddy’s Market.

Great Homer Street Market – to give it its real name – was the scruffiest-looking place you’ve ever seen. It’s an Everton institution and it’s been there forever. My mum’s aunty even had a stall at Paddy’s in the 1930s – that’s how old it is. It’s massive and it’s got hundreds of indoor and outdoor stalls.

Now, I’ll bet you every kid in Liverpool has been to Paddy’s on a Saturday morning with their mum at some point, dragged around, feet sticking to the floor. There was always talk that Liverpool Council was going to redevelop Paddy’s, and the indoor part was moved to a better spot over the road, but really, it hasn’t changed, and I have always loved it. The stalls at Paddy’s stretch right out and along Great Homer Street, so you’d always find all sorts there, from fruit stands to second-hand clothes stalls and furniture places or people selling off job lots, that kind of thing. Years ago you’d get moneylenders hanging about too. ‘Mary Ellens’ – that’s what we used to call them.

When I set up my stall there the indoor part of the market was mainly filled with second-hand traders. Then, as you moved through, there would be other types of stalls – people who made their own stuff, like ladies’ clothes, knitted clothes, curtains, jewellery and kids’ clothes. Some of them were kind of homespun-looking, but some of it was really well made. The ones that always made me laugh, though, were the shoe stalls where they had big holes in the sides to pull string through so as to bind them together in a ‘pair’. Even funnier was that people actually bought them.

So this was Paddy’s, and every Saturday I’d set up my stall with children’s clothes I’d designed and made myself. I’d sold there before, but this time my stall was bigger. It was in the indoor part of the market, in the middle aisle at the back, alongside the dressmakers and second-hand clothes traders.

It was mainly christening dresses I was doing then, but I’d make other accessories to go with them to make a set. There would be these tiny top hats and bibs with children’s names embroidered on them. I’d even do these little ballet shoes. And bonnets – I loved making bonnets. I had had a thing about them ever since I was a kid and used to watch films like Little Women.

I taught myself how to make bonnets – no pattern; nothing. But I wanted to do them properly so I went to the library and looked for as many books about the American Civil War as I could find. I’d take them home and really study the pictures of the women in stiff peaked hats, you know, those ones with big ribbon ties under the chin.

I wanted to make my bonnets look exactly like the ones I saw in the books, and that meant making sure that I got every detail right, like the little frills inside the peaks. I would use different silks to create these, and it made all the difference. Then I’d add other details, like a huge bow on the side, say. The more I looked at the pictures of the bonnets in the books while I was making them, the more they turned out just like the ones I saw in films. They were lovely, they were, really lovely, and I’m sure that’s what started selling the christening robes – everyone wanted the matching bonnets.

Dave had helped me make my stall look really nice. He said you couldn’t see the little dresses very well when they were just hanging up, and that the way I had displayed them didn’t do them justice.

Dave is a builder and is really good at making things, so it was his idea to do stands to put the dresses on. They really made a difference and the stall looked classy, which was an achievement because the market was a right mess and it wasn’t unusual to see rats running around the back of the stalls. But after Dave did our corner up, it stood out. It took us two hours every Saturday morning to set up that stall. But it looked special – just rows and rows of pretty little white and ivory silk and satin dresses. It was quite talked about and people used to come by just to see it. Then the local press did a story on our stall and after that I got loads of interest, with people coming from miles around just to take photographs of the children’s outfits. The business really started to take off then.

There were a lot of gypsies who used to come to the market – all the travellers go to Paddy’s – but I didn’t realise they were gypsies then. The one person I knew with connections to that world was a woman in the market known as Gypsy Rose Lee, whose stall was next to mine.

Now, Gypsy Rose is a Romany. But back then I didn’t know the difference between a Romany and an Irish traveller, or whatever. I didn’t even relate her to being a traveller. To us, she was just someone who read palms, like those women in Blackpool near the pier – the ones who stop you and say, ‘Can I read your palm, love?’

Gypsy Rose was lovely. She was a good-looking woman with long, brown hair. She was kind and good company and not at all like the gypsies we were scared of as kids and that my mum had warned me about. I’ll never forget seeing my mum hiding in the house one day when I was little. This woman had knocked on the door trying to sell lucky heather and pegs.

‘Don’t ever open the door to them,’ Mum whispered, ‘because if you don’t buy off them they’ll put a curse on you. And don’t look one in the eye, right, or they’ll put a curse on you. And if you ever meet one and they try to give you lucky charms, take them, because if you don’t they’ll put a curse on you for that too.’

I was terrified of gypsies after that. Since then, I’ve had loads of curses put on me. Honestly, loads of them.

But I do remember the first time I encountered a real gypsy. This girl came to see me at my stall and was looking at the christening dresses. Up she walked. Dead tall, she was. And blonde. Really stunning. She was about nineteen and I remember her because she was really friendly, a naturally nice girl, you know. Michelle, that was her name. I’ll never forget her face. And I’ll never forget Michelle’s kids – gorgeous, they were. They stood out, all really blonde with pretty ringlets. That’s another reason I could sense something different about her – her kids just looked like they came from another era, as though they had stepped out of the pages of an old-fashioned story book.

‘Can you do Gone With the Wind dresses?’ she asked in a quiet voice.

You know by now what that film meant to me – Gone With the Wind, Scarlett O’Hara, velvet, big skirt, bonnet …

‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘I can do that.’

‘Well, how much will they be?’

I told her that I couldn’t give her a price because I didn’t use that kind of velvet at the time and I’d have to find out how much it cost.

‘Well, I want three red ones,’ she said, looking down at these three beautiful little girls trailing behind her.

‘You’ll have to leave a deposit,’ I said.

She handed over £80 and I measured up the kids. She said she’d be back the next Saturday to pick them up.

So off I went, thinking about Gone With the Wind and all those big, hooped dresses. The moment in the film that made the biggest impression on me was when Scarlett O’Hara has no money and she pulls the curtains down so that she can use the fabric to make a dress. And the sound of the dresses! Oh, I loved the way you could hear the taffeta swish when Scarlett walked in the room. I adored these dresses. I remember watching it one time, thinking, ‘Why don’t we all dress like that?’ You know, in big dresses with tiny little waists and with beautiful bonnets on the side of our heads.

Could I do Gone With the Wind dresses? I don’t think that girl could ever have known just how much she’d come to the right person. I couldn’t wait to get stuck in and start making them.

I’ve still got pictures of these little red velvet dresses somewhere. They stuck right out, and had wide ribbon belts around the waist with big red bonnets to match. It nearly killed me making them, as I was trying to get them done in time for the girl coming back while having to make new stuff for the market on Saturday as well.

In the end I did finish them in time, and I’ll always remember the struggle I had loading them into the van and carrying them to the market because the hooped underskirts weighed a ton. When I got to Paddy’s I laid them flat, behind the stall, ready for this girl to come in and pick them up that morning, which was when she said she’d come back.

It was getting later and later, and so at about twelve o’clock I thought, ‘These are going to get filthy lying through the back here by that dirty floor.’ You only have so much space behind your stall at Paddy’s, and people are always traipsing in and out, bringing more rubbish in with them. Not only that, there was a leak in the roof right above my area, so I thought, ‘I’ll just put them up with the other dresses for now.’

Baby Mary had just bought me a cup of tea. Her stall was right opposite mine. Baby Mary sold baby clothes and beautiful hand-knitted coats and hats. We were standing having a chat and she was looking up at the little Gone With the Wind dresses. ‘They’re lovely, them, aren’t they?’ she said. ‘Just gorgeous.’ I had to admit that they did look really nice. Another woman went by and said, ‘God, they’re lovely. How much are they?’ I told her that they were actually sold and that the girl who ordered them was coming back to pick them up later.

Then I remembered that I had the girl’s phone number, so I tried calling her. There was no answer; the phone didn’t seem to work. Later, I would come to realise that this was normal with travellers – phones that don’t work; numbers that don’t exist; calls that are never returned.

It was the afternoon by now and I was still hoping she might turn up. I was standing there having another cup of tea when another girl walked past.

‘How much are they, love?’ she asked.

‘About eighty quid,’ I said, just picking the first price that came into my head, while also kind of knowing that was far too cheap because there was quite a lot of velvet in them.

Anyway, as the afternoon went on more and more people stopped to look at the little red dresses, with their little matching bonnets perched to the side.

‘My God, there’s a lot of interest in them, isn’t there?’ said Baby Mary.

‘Yeah,’ I thought. ‘Isn’t there just.’

At that point another woman walked by, then came back to take a closer look.

‘Can you do them in different colours?’ she asked.

It seemed that about every ten minutes people walking past were stopping to ask about the outfits. How much are these? Can you do them in this? Can you do them in that? How long will it take you to do them?

I was beginning to realise that something strange was happening. ‘Who are these people?’ I thought. ‘Why are they so interested in these dresses?’

The thing is, when it first started to dawn on me that the young girl with the pretty kids wasn’t going to come back and pick up the dresses, I was annoyed. ‘If she doesn’t buy these outfits, who the hell else is going to?’ I wondered. They were just so over the top, all lace and frills and stuff, and I didn’t much fancy the idea of carrying them back home again.

But then this stream of interested onlookers kept on. Some even went off and brought others back with them to have a look. By about quarter to three in the afternoon loads of people had stopped by my stall. ‘What’s going on here?’ I wondered.

I noticed that the women who were stopping by were all rather similar, but different from the Liverpool girls who usually came to buy the christening stuff. They were all crowding around and getting quite close to me, as though they had no sense of personal space. It was pretty overpowering and really quite scary. I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it was about them that really struck me most but, looking back, I guess it was the way that they spoke.

All gypsies speak differently – the Romanies and the English gypsies probably sound nearest to the way settled people speak but their accents are different still, so you know that they are not what they call country folk. But it was the Irish travellers who really made me sit up and take notice that something was going on: they speak so fast that they’re hard to understand and they sound as though they’re talking in a foreign language. They are very, very loud and they all speak over each other. I found it quite intimidating, so that day I just stood there looking and listening and wondering what the hell was going on.

I also remember that these women looked different to our usual customers. It wasn’t instantly obvious, but I did notice that they were quite young, from the very young-looking – 14 or 15, say – to women in their late 20s and early 30s. And the young girls looked quite glitzy – in some cases a bit too racy, I remember. What with their tiny belly tops and short skirts, I thought that they were dressed quite inappropriately for their seemingly young years. Then the older women looked like they may have been big sisters – a bit more dressed-down and casual – but they talked to the younger girls as though they were their mums. All of them looked as though they cared about the way they looked, though, and I could tell that they had spent time doing their hair and things.

Their hair – that’s another thing that struck me. Almost every one of these girls and young women had beautiful hair – long, glossy, tumbling blonde or jet-black flowing hair. They were all striking looking. And boy, did they make a noise.

‘They’re travellers,’ said Gypsy Rose Lee.

I looked at her and then looked at all the girls crowding around the stall, and the penny started to drop. I was really fascinated then.

I took ten orders for those dresses that Saturday. After that first one, which I knew I’d undersold, I started asking for £100 per dress, as I needed more money for a roll of velvet in a different colour. It was getting nearer Christmas time, so a lot of them wanted red velvet, which was good because it meant that I could use up the 50-metre roll I had at home. As well as phone numbers, I took deposits from them all.

The next week I took a different style back with me, a more ornate dress with layers and layers of lace, a cape and what was to become my most sought-after top hat. I’d bought two rolls of velvet, as someone else wanted a dress in blue. I’d made it for the woman already, but as she wasn’t coming in to pick it up for three weeks I put it on display on the stand. I got more orders that week than I’d ever had before.

I was still trying to make everything myself, but with all these new orders coming in that was becoming impossible. So I asked a seamstress called Audrey, who I used to work with, to help me. Audrey had actually taught me to sew properly a few years back when I had my first children’s clothes business, so she knew exactly what to do. Then we got another girl, Angela, and there were three of us doing it. We still had to work all week, with me working every night to get them done, though. The bonnets used to take the longest to do because Angela and Audrey found them tricky – maybe they hadn’t watched Gone With the Wind as many times as I had. They gave it a good go, but their bonnets weren’t quite as detailed as I knew they should be, so I had to do them myself, which was a nightmare as each one took about three hours to make. Finally, after lots of practice, I got the making time down to an hour.

By November I was getting loads more customers, so I thought I might start doing boys’ outfits as well, as not many people were doing them. I started to make suits with little matching caps with feathers, or with a big, droopy tassel – like an emperor’s hat. I also made old-fashioned Oliver Twist-style suits and caps. I got a reputation for doing boys’ suits then. But I have to admit that these were no ordinary suits. Seeing pictures of them now reminds me of all those nights I stayed up to get them finished in time for the market. They were so over the top, but that’s why I loved making them.

But then I’ve always loved historical costumes, especially the really old-fashioned ones that Henry VIII and Elizabeth I wore. All those big Tudor sleeves, lace collars and ruffs and things fascinated me. And anything Victorian – I just love Victorian styles.

One of my favourite things about the whole dressmaking process is going to the library to look at all the books about history and the clothes people wore in the old days. I liked the way the Little Princes in the Tower were dressed. You know, those two little boys who were locked up by their uncle hundreds of years ago. After looking at pictures of them I made these little gold, embroidered coats with little matching cravats for boys. They turned out really smart.

Of course, looking at all these old books gave me loads of new ideas, and the clothes I made were all very costume-like, I suppose, because that’s what I liked. But I do remember feeling a bit worried that the boys’ ones wouldn’t sell because they were so different from what we had been doing.

As ever, though, Dave was quick to reassure me: ‘You know what, babe, they’re brilliant.’ He said he’d never seen anything like them. Everyone knew Dave on the market then, because he used to come with me on Saturday mornings. He’d load all the stuff in his van and take me down there. But to give you an even better idea of the kind of man Dave really is – in the end he gave up his Everton season ticket to come and help me every Saturday.

Dave gave me confidence and encouraged me all the way. That felt good and it was great to have him around. Of course, he was right, I needn’t have worried: the little boys’ suits went down a storm.

I really loved doing Paddy’s Market, and I became good friends with a lot of the other stallholders and regular customers there. We’d fetch each other cups of tea and look out for each other. We were like a family.

Occasionally, the DSS or the police used to come to Paddy’s and do raids, looking for counterfeiters or people who were working while signing on. When someone heard that they were coming, word would spread through the market like a speeded-up Chinese whisper. You’d see people with dodgy DVDs and the like flying all over the place. The stalls would clear as if by magic. It was dead funny. We used to have some laughs on that market, we really did.

Just how much my Paddy’s mates would look out for me would become clearer later when I was to go through what would be one of the worst times of my life. When the going got really rough, not only did my market friends not let me down, they stuck right by me.

Things did start to get a little strained, though, when the travellers came to my stall. They’d all crowd round at once – the sister, the mother, the kids – touching things, asking things, all trying to talk to me while I worked out a price for what they wanted. It was pandemonium.

Some of the travellers who didn’t know I had a stall there, but who had seen other gypsies with the dresses, would come by and say things like, ‘Oh God, I didn’t know you were here. I’ve just given a deposit to the other woman around the corner for a dress, but I’m going to go round and get my money back.’ And they would.

I think it got up the noses of some stallholders, who didn’t seem that happy about the amount of attention I was getting. Some of them probably resented me for it. I suppose I can’t really blame them, because at times my stall would be teeming with women placing orders.

‘How much, love?’ they’d ask – usually all at once, while talking to their kids and sisters at the same time, the kids talking over them.

‘The price is on it, look, up there,’ I’d say.

But then they’d start: ‘Oh, go on, love, you can do better than that. I’m going to order three of them. I’ll give you £1,000 now, love.’

Now, I hadn’t seen £1,000 for a long time and so I’d be like, ‘Oh, all right, go on then.’

The travellers always wanted discounts. But it wasn’t just 10 per cent that they wanted off, and the same scene would be played out every time it came to the money bit. ‘I haven’t got any more money, love. Come on, that’s all I’ve got, love. Oh, go on, love.’

Before I knew it I’d be making ten dresses, so though I’d just been given £1,000, I was already out of pocket. I was making those dresses for practically nothing.

I knew I’d have to change my tune, because if I didn’t I was never going to make a profit. As it turned out I didn’t have to think about it too much, as it just happened quite naturally one Saturday. We were really busy and the stall was chaos – all these women chattering and shouting out all over the place. I thought my head was going to burst open. Only my mouth did instead.

‘That’s it!’ I screamed. ‘Nobody is getting served until you all shut up!’

‘Oh, love. Sorry, love,’ said one of the women. ‘We don’t mean any harm. We just talk loud. It’s just our way.’

They weren’t so perturbed and I realised that she was right, that was just their way, and if I wanted these women to carry on buying my dresses I’d just have to find my way of dealing with their way. From then on I got into the bargaining and even started to enjoy it. All I had to do, I learned, was stick to my guns. And it all added to the chaotic nature of the market.

Whether it was the travellers, local Liverpool girls, or the occasional raids, there was never a dull moment at Paddy’s, because if there’s one thing that flea markets throughout the world have in common, it’s great characters. And my stall was surrounded by them.

There was Baby Mary opposite me, Second-hand Mary over on one side, and Dancing Mary, who used to do all the dancing gear for kids at the back of me, and a regular at the market, Mary Hughes. Honest to God, I think they were all Marys!

Then there was Second-hand Joan. She was a real con merchant. Second-hand Joan used to borrow money from everyone but always seemed to have trouble paying it back. Second-hand Mary and Baby Mary had warned me never to lend Second-hand Joan anything.

Funnily enough, about three years ago Joan came into Nico, my shop in Liverpool that you might have seen me in when Big Fat Gypsy Weddings was on TV. She asked me if I had any old stuff that I could give her for her stall. I was happy to offload bits and bobs that we had lying around, so I went off upstairs to have a look. Joan followed me, but when we got up there I turned around and she literally fell to her knees.

‘Please help me, Thelma,’ she cried. ‘Help me. Please help me! I’ve got to pay all this money.’ She asked me to lend her £2,000. I just looked at her. It was all a bit awkward.

‘I just don’t have that kind of money to give you right now, Joan,’ I said.

‘Oh, but can you get me it? Can you get me it?’ she sobbed.

I felt sorry for her, as I knew that feeling. ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘I’ll try. But for God’s sake, get up, Joan!’

I quickly walked back downstairs. Pauline – who has been my trusty right-hand woman for as long as anyone can remember, but who no one forgets – was staring at me as we walked down. She had a look on her face that said: ‘Don’t you dare – don’t you dare trust her.’ We managed to calm Joan down a bit and got her to leave.

Then, just as if someone had written it in a play, who should walk in minutes later but Baby Mary. It was like Paddy’s Market days all over again. ‘Give her nothing,’ she said. ‘She owes so and so and so and so. She’s borrowed some money from some woman on the market and her husband has come down and said, “You get my wife’s money back now!” So now she’s come to you to get it.’

I didn’t give Joan the money – though I did think about it, because, as you’ll find out, it wasn’t that many years before that I had been in a desperate situation myself. I felt genuinely sorry for her. And I had been pleased to see her again because I used to talk to her a lot on the market.

But that night I went to the bingo with my mum and who should be sitting there playing? Joan! Yes, the woman with no money – out playing bingo! But then, you’ll always get her type on a market.

After a few months at Paddy’s, I’d kind of started to recognise the travellers from the other people at the market. One day this woman came to the stall – older than most of the traveller girls that came in – and I wasn’t sure if she was a traveller or not. She told me she had nine sons and had just had a baby girl after twenty years. She was absolutely besotted with the child.

This woman was from London, and had heard about me and our dresses, so she’d made the trip up to Liverpool with her husband to find me. That Saturday will always stick in my mind because when her husband came over he looked around the outfits on the stall and, after about four seconds, looked at me and said, ‘I’ll take the lot.’

And he did. He took every single thing I had that day that would fit the little girl. Everything. And just before they turned to leave he said, ‘I want you to make more for her because we live in London and we’re going back there. Can you make me all different ones? In different colours?’ I think I worked solidly for three weeks after that, just making dresses for that woman’s baby.

I knew that the dresses we made were special, and as the travellers used to request that more and more be added to the designs they started to look even more so. But sometimes I remember thinking while I was making them, ‘How the hell are the poor kids going to walk in these?’ I suppose, as some of them were for girls who were only around six months old, that wouldn’t be such a problem. But they were big and heavy and they really stuck out. And sometimes the little ruff necks would be stiff because I couldn’t use anything softer to make them stand up. So I’d suggest to the women that it might be a good idea to have a different design and to maybe leave out the hoop so that the baby could move a little easier.

‘I don’t think this will be very comfortable, you know, for the baby to lie in,’ I’d say.

‘No, no, love, she’ll be all right, she’ll be all right,’ they’d come back. These women were determined to have the biggest and best, regardless.

Not so long ago I was reminded of those days when I had gone to meet some English gypsies at their house, which was a massive place in Morecambe. I was a little bit apprehensive about going at first, as the travellers can be a bit wary of you if they don’t know you, and some of the Romany and English gypsies were not happy at the way they had been portrayed on the TV programme. So I was thinking, ‘Oh, we’re going to get a right reception here.’

But when we walked in they were all just so happy to see me. Pauline and me got chatting to them and one of the young girls came up to me and said: ‘I’ve got a dress you made for me when I was four. Do you remember?’ I couldn’t, because she must have been about sixteen or seventeen by this time. ‘Have you still got it?’ I asked. So she ran upstairs and brought down this little brown and ivory velvet dress.

At that point her dad walked in and said, ‘Do you remember we came to your house on Christmas Eve to pick it up?’

‘God,’ I said. ‘Yeah, I do remember that!’ It was about thirteen years ago. ‘Bloody hell,’ I thought, looking at that dress again. It was still in perfect condition, still in its bag and everything. It was short and sticky-out, made in velvet panels that were all braided around the edge, and it had a little coat that went over it, with a tiny muff and a beret. I had seen that outfit on a woman in a book about the 1800s and then made my own little version of it.

When I looked at that dress it brought back all these really happy memories of that time at Paddy’s in the late 1990s and how everything had started to pick up with those little Gone With the Wind dresses. They really were sweet.

I suppose my original Victorian designs look a bit dated now, when you think about the requests we get for Communion dresses these days, with their giant skirts, hundreds of ruffles, miles of material and all the glittery crystals and crowns, and the kids turning up to church in their own pink limos. And I couldn’t be happier doing all the fantastic and elaborate designs that we are asked for today, but I do have fond memories of making these early designs, of being so determined to get them right, so that all these gorgeous little kids would look like characters out of a film, all perfectly pretty. And I’m dead chuffed when my long-standing traveller customers want to pull them out and show me those early ones again. Luckily, my English and Romany customers still like to dress their kids in these romantic old styles, so I do still get a chance to make them.

By the end of that first year on the market I’d got to know a little bit more about the travellers’ ways; I suppose I’d started to accept their way of doing things and was becoming less surprised that travellers’ lives weren’t much like mine. But a memory that still really sticks in my mind was of a little girl hanging about the stall in December. She was looking at the dresses while her mum was settling up for orders and she was chattering away about how they were all going to meet on Christmas Day and Boxing Day. Then she said something about them all being in their trailers. It had never actually occurred to me that gypsies still lived in caravans.

‘Bloody hell,’ I thought, ‘how are you all going to get round the Christmas table in a caravan with these dresses on?’ I thought of all these lovely little girls in all their lovely little velvet dresses … Then I pictured all of them covered in chocolate on Christmas Day. I didn’t feel as romantic about the whole thing after that.

But then I was exhausted. It had been a rollercoaster couple of months and I knew I needed a rest before our busiest time of the year – First Communion season, which was going to start as soon as Christmas and New Year were over.

‘Thank God it’s Christmas Eve,’ I said to Dave, when he got back from delivering our last order to a traveller site in Leeds. ‘At least they’re not going to want any of these dresses in summer …’

2

The Tale of the First Communion Dresses

My gypsy customers started coming back to Paddy’s the first few weeks in January. Only now they were coming from all over the country, not just Liverpool or Manchester but from London and Ireland too. As I was getting to know them all a little better, I started giving my phone number out to some of the travellers. They had also started to talk to me more.

One Saturday, a girl approached the stall with a pram. She had a big black coat on and was wrapping it tightly around her. The coat seemed huge because she was tiny. She was very, very young, and, to be honest, looked like she had the world on her shoulders. She kind of shuffled up.

‘Are you the Liverpool woman who makes the dresses?’ she asked, softly. ‘I want dresses made for two little girls,’ she said, pointing to the pram.

I looked down and saw these two tiny little things. One looked around twelve months old, the other a newborn baby. ‘I want them really sticking out.’ And then I want this, and I want that, the young girl carried on. She said that she wanted a bonnet for the really tiny one, who I noticed, when I looked in at her properly, was so small that she looked premature.

‘I’m not sure that the dresses are quite right for your newborn,’ I said to her.

‘Oh, she’s not newborn, she’s ten months. And she’s two,’ she said, pointing at the older baby. They really were the smallest babies I’ve ever seen.

Then the girl started asking if she could have diamonds on the dresses. Now, she was the first traveller to ask for diamonds, and as I’d never done that before I was a bit unsure. So I told her, ‘I can’t start them without half the money as a deposit.’ She said she’d go and get the money and be straight back. So off she went.

Ever since the stall had become popular with the travellers, a lot of the other stallholders had been warning me against working with them. ‘Be careful. Don’t trust them. Just don’t trust them,’ they’d say.

Surprisingly, Gypsy Rose Lee was always stressing the point. But by then I realised that she was different from them. Gypsy Rose was Romany. Romanies are wary of other travellers and, to be honest, sometimes I think they see themselves as a cut or two above them.

Gypsy Rose’s kids were around her stall all the time. They were lovely, really well-behaved, and they’d go and get us all cups of tea. The other traveller kids that came to us, on the other hand, mostly Irish, were loud and boisterous and just so full of confidence. And the language! My God, it was terrible. But I soon got used to that and realised it’s just the way they speak. It’s not threatening or anything.

So, I waited for the girl who wanted the diamond dresses to come back, and deep down I suppose I never expected to see her again – the travellers are always full of promises of coming back but quite often they don’t. But she did, and this time she had her husband in tow. He was carrying one of the babies and was smothering her in kisses. ‘What a lovely dad,’ I thought, surprised at how kind and affectionate he was being. He looked up at me and said, ‘How much are the dresses going to be?’

Now, for the tiny little baby’s outfit the girl had said that she wanted a diamond collar and diamond cuffs. She wanted diamanté all over the dresses, basically. I didn’t know a trade supplier of Swarovski crystals, so I knew I’d have to buy them at the full retail price, which would be dear.

‘£600 for the two,’ I said, thinking he’d say ‘No way’, saving me all the trouble of having to make such a tricky order.

But he didn’t even think about it. He put his hand in his pocket, flicked through the notes and handed me the cash. As they left I remember standing there thinking: ‘Jesus, I’d better make sure these dresses are really nice.’ The couple came back a few weeks later to pick them up. The young mum was over the moon.

A month or so after that I was talking to another traveller woman, Mary – Mary Connors. She was a good-looking woman, Mary, tall with long, brown, wavy hair. You could tell, just by looking at her, that she must have been stunning as a girl. By the time I got to know Mary she must have been around 35 and had had seven kids. She still had a cracking figure, though, and I always liked the way she dressed. Mary was smart and classy looking and would wear long skirts with boots, that kind of thing. She had a neat style, well-off looking, you know?

The other thing I liked about Mary was her confidence. She had an air of authority about her and I knew that she was well liked in the community. The fact that she had seven children earned her the respect of her peers, as the more children a traveller woman has the more status she gets. I always liked seeing Mary with her kids – she was a really warm person and a good mum. Her kids adored her.

But Mary was tough, and even though she was only in her mid-30s, you could tell that she had lots of experience. She was wise and taught me a lot, and would come to the stall just for a chat, asking how things were going and whether I’d had more traveller customers. When I described to her who had come in, she instantly knew who the family was and would tell me all about them. In a way Mary was educating me, teaching me more and more about the travellers that would finally make my business.

So she’d become a bit of a regular on the stall, and though we didn’t know each other really well then, we hit it off and she obviously enjoyed my company as much as I did hers, so she was always popping in for a gossip. One day she came in and asked me: ‘Did you do Margaret’s dresses for the wedding?’

‘Who’s Margaret?’ I said.

‘Margaret, you know, Sweepy’s Margaret?’

The thing is, the gypsies think that you know everyone that they do because they live in such a closed community and all know each other. But I had no idea who Margaret was. Also, in my experience all traveller women seemed to be called Margaret or Mary!

‘Oh, they were handsome, love,’ she said. ‘All these diamonds on them. Oh, they were really handsome.’

Then, of course, I knew who she was talking about.

‘Do you know him, love?’ she asked, meaning the man who’d given me the cash that day.

‘No, not really,’ I told her.

‘Oh, he’s a multi-millionaire,’ said Mary. I was gobsmacked, thinking back to the day that I first set eyes on young Margaret, remembering that black coat and how she was the poorest-looking soul I’d ever seen.

I know the family really well now. The girls in that pram are all grown up and they love the fact that they were the first to get their dresses covered in diamonds. They still talk about it.

Shannon, the two-year-old, is 16 now, and the really tiny one that I was worried about, Shamelia, is 15. They’ve got two more sisters now as well, and we have made swishy little dresses for them since they were little too. Shannon and Shamelia are a great barometer of how traveller tastes have changed. When we first started making designs for them their mum wanted all the Victorian stuff, but with lots of glitter, really pretty dresses. Now that the girls are older and have their own ideas about how they want to dress, it’s all sparkly Swarovski-covered catsuits and the like. They’ve grown up to be really gorgeous, lovely kids, these girls.

The thing is, travellers always like to dress their children well. And, you know, I think Liverpool people are exactly the same as gypsies that way, because if you don’t have much to call your own, your whole pride comes from how good your kid looks. Nothing feels better than to have your child with you, dressed up so nice that people stop and say, ‘Oh, look at what she’s wearing.’ You just want to give your kids everything. There are probably more designer kids’ boutiques in Liverpool than anywhere else today. Yet for the Liverpool mum there are never, ever enough.

I’m the same myself. About thirty years ago I bought my daughter Hayley a pair of shoes that cost around £70. To be honest, she wasn’t even at the walking stage, but I didn’t care, I just loved dressing my kids up.

A few years back, when my youngest daughter, Katrina, who’s seven now, went to nursery, all the girls who worked there used to get so excited when I dropped her off. I wasn’t on the telly then, so they didn’t know I was a dressmaker. ‘We can’t wait to see what she’s got on when she comes in,’ they’d say. So I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll definitely need to make sure I have something new on her every day if they are waiting to see what she’s wearing!’ Now I’m the same with my granddaughter Phoebe – I buy her new outfits all the time.

It’s such a Liverpool thing – maybe you need to come from Liverpool to understand it. You see, when I was a kid, no matter how little money we had, I always had the best dress and, from as far back as I can remember, I knew exactly what I wanted to wear: dream-come-true dresses that moved when you moved, dresses where you could feel the weight of the fabric swinging about you as you walked.

Once my mum asked this woman, who used to make costumes for the dancing school I went to, if she would make me a couple of day dresses. I was so excited when we went to collect them. The first one was pink with lots of frothy net under it and a big tie belt wrapped into a big bow at the side. As soon as I put that one on, I just didn’t want to take it off. I had to, though, because I had to try on the other one.

Now, this other one was probably a lovely dress but it was straight up and down with a pleated hem. As soon as I saw it I thought, ‘No! No! No!’ I looked at my mum and started crying. She told me to try it on. ‘I don’t want it,’ I wailed. ‘Get it off me!’

‘No, no, they’re lovely,’ my mum said to the woman as she paid for the dresses, obviously dead embarrassed, trying to rush me out the door. So off we went back home with both of the dresses. But I never did wear that straight dress. I never wanted it. All I ever wanted were pretty, girly, sticky-out dresses. So when these young gypsy girls come to me now, I know exactly why they want them too. But then I’ve always had a strong vision in my head of what the perfect girl’s dress should be.

Back in the early eighties, long before I’d set up at Paddy’s, I’d just had my youngest daughter Hayley. On Saturdays I used to go shopping with my mum, and we’d go to all the little kids’ boutiques in Liverpool looking for clothes for her.

The thing is, I could never find anything that I really liked and I remember thinking I’d like to do kids’ clothes myself. I’d just had a baby and was looking at it from the point of view of what I’d like to dress her in, as a customer. ‘If I can’t find the right thing,’ I thought, ‘then there must be loads of other mums out there who feel the same.’

More than anything else, though, I just wanted to dress Hayley the way I liked. I thought about it a lot, and then it just came to me: I’ll start up my own children’s clothes business. And so I went about setting up a shop, Madine Miniatures. At the time I was married to Kenny, my three older kids’ dad. Kenny already had a successful glass firm, so we were well-off enough for me to give it a go. And things were not that great with me and Kenny by then, so starting the business was also a good way of taking my mind off our troubles at home. My mum had also just been made redundant from the GEC factory, where she had worked as one of her three jobs for twenty-five years. So she put all her redundancy money in to get the business started.

Soon it was up and running and I threw myself into the task of finding out when all the clothing fairs were on. I’d travel the country with my mum, looking for the best stuff we could find.

The first shop I opened was in Ormskirk, just north of Liverpool. But as there was already a kids’ clothing boutique there the reps would give them priority stock and wouldn’t sell to any competitors. But this meant that I was being left with the not-very-good stuff, which I certainly didn’t want. What I wanted to sell were special children’s outfits, the kind that gave me butterflies in my stomach when I looked at them.

I remember talking to one rep and asking if I could order this particular dress. ‘Sorry, you can’t have that,’ he said, in that nose-in-the-air kind of way, explaining that so-and-so from the other shop had bought it. I looked at him and thought, ‘You cheeky get! One of these days, you’ll be dying for me to stock your clothes!’

‘Don’t worry, love,’ my mum used to say, ‘you’ll think of something. We’ll just make sure you’re the biggest and the best.’ The thing is, the man was the rep for all these lovely Italian, German and Dutch designs that you couldn’t get over here. ‘OK,’ I thought, ‘I’ll just go to Italy, Germany and Holland to buy this stuff myself.’ And that’s exactly what I did – I brought ranges of kids’ clothing to Liverpool that nobody had ever seen or even heard of before.

I had a big opening day for that first shop, and everything felt good. Because we’d made sure that Madine Miniatures was stocked with quite unusual kids’ clothes and unique designs, it really took off, and before long we had six shops all over Liverpool. Madine Miniatures was getting a great reputation and our Communion dresses were the most sought-after in the city.

Communion dresses are a very big deal in Liverpool, with it being such a big Catholic community. Even today a big part of my business is designing Communion dresses. And there are three milestones in a gypsy girl’s life – her christening, her First Communion and, of course, her wedding.

I first started doing Communion dresses after noticing that all the ones I’d see at European suppliers were the same. And the one thing that a mum doesn’t want is her daughter’s Communion dress looking the same as the next girl’s. I’d look at them and think: ‘They’re all straight up and down. They don’t move. Where’s all the bloody fabric?’ And then I thought: ‘I’d make the skirt bigger and I wouldn’t have that there; I would put buttons down here …’ I was not very impressed by what I was looking at – but actually what I was really looking at was a giant gap in the market.

So I decided that the best thing to do was to make the dresses myself. Even though I couldn’t sew that well, I knew exactly what I wanted. My mum had learned how to sew at a night class when me and my brother Tom were kids. She would sit up all night making me new dresses, determined that I would always be the best-dressed little girl at school. Also, my Aunty Mary was a tailoress, so I thought, ‘I have all the ideas in my head, all I have to do is to draw them out and Mum and Aunty Mary can make them.’ I used to watch my mum and Aunty Mary sewing and then have a go myself. I wasn’t very good at it at first, but I wouldn’t give up until I got it perfect.

Soon the dresses were going down really well. Everyone wanted them, and after a while we were getting so many orders that we had to think about getting someone else in to help. Thank God we found Audrey. Now, Audrey was a little bit older but that was good because she was old school. She knew exactly what she was doing.

In fact, Audrey was so by the book that, come five p.m. every day, she’d have her coat on and she’d be off. Out the door by one second past, was Audrey. She was strictly a nine-to-fiver, but I have to give it to her, when she was there she didn’t stop for a minute. But as more orders came in we needed to put more time in, which made me determined to improve as a seamstress. Audrey taught me a lot – far more than the college I had started attending did. The more I learned, the more I could finish the dresses myself. We also took on a younger girl, Christine, to do the cutting. So, business was picking up, we were all working from a room above the shop in Ormskirk and everything was good.

Every time we put a new Communion dress in the shop, people would come in and admire it. ‘Oh, isn’t that lovely,’ they’d say. ‘I’m quite good at this,’ I thought, so I just focused on making my ideas for these Communion dresses come to life. I suppose, looking back, I’ve always been the kind of person who sets her mind to things, thinking, ‘Right, I’m just going to do it.’ I can’t do anything half-heartedly.

After I came up with a few dress design ideas, I started really going for it. I always thought that the dresses could be bigger, because no one else was doing ones like that, so I looked through all my history books and wedding magazines for ideas – because, essentially, they were little wedding dresses. I’d have them with these big, Victorian-style leg-o’-mutton sleeves and then maybe add a little cape. And I always liked to put a large bow or flower on them to finish them off. That way they really made a statement.

People loved them and, as more and more requests came in for them, we started having to limit each school to ten differently designed Communion dresses. The way it worked was this: every season I’d create ten different designs, and the first mum from each school to put a deposit down on the design she liked best was the only one who could have that dress, and so on. It meant that ten little girls in the same school might be wearing our dresses come Communion Day, but there would never be two wearing the same one.

Even so, there was often pandemonium over who got these dresses, with real rivalry breaking out between the mums at each school. I remember that there were women literally fighting in the shop in County Road. Honest to God, they were actually punching each other.

Another time I did this dress – I think I was into Elizabeth I at the time – with the ruff collar and the really tight, tiny waist with a V-shaped bodice all covered in pearls. I made the skirt in satin panels, which were differently decorated. Everyone who saw it was like, ‘Oh My God, it’s amazing. It’s fantastic. I don’t care how much it is. I’ve got to have that dress.’ There was a big hullabaloo over who was going to get that too.

The thing is, it was all good for business and I was able to start building up a team. I took on another three girls, and then Pauline started working in the County Road shop. Pauline had been a customer originally, but as time went on she began to pop in every day to have a chat and see the new dresses that had come in. She became such a part of the furniture that one day, when I was run off my feet, I asked her to muck in and help me out there and then. I was well aware that Pauline knew that shop – and the stock it carried – inside out.

It was one of the best moves I ever made. Pauline is the best saleswoman you could ever wish for. We have worked together on and off ever since. Pauline whipped our customers up into a right frenzy about the Communion dresses. ‘Oh, you should see the new designs coming in,’ she’d say. ‘They’re gorgeous. You’ll be amazed when you see them.’ All the women, desperate that their kid would look the best of the lot, would be like, ‘Oh, put my name down for one, put my name down.’ None of these dresses ever reached the shop – because before they could get there Pauline had sold every single one.

So, it was really through the Communion dresses that I first got into dressmaking. And all these things that I liked, all these old, historical costumes that I was influenced by, were obviously touching a nerve with people, because the next thing I knew I had an agent in Belfast who started selling our dresses all over Ireland.

The business was doing well and everything was OK on that front. But things with me and Kenny were getting worse. The more successful I became, the more strained things were between us. Kenny, you see, always liked to be in control, and as I became immersed in my own thing I was becoming more independent.

Then I had another setback. The main shop in Liverpool kept getting broken into, and this put a massive strain on the business because it was becoming increasingly hard to get insurance. Eventually the only way I could keep things afloat was to close all of the shops except two. Looking back, it was probably too much having six of them and trying to make clothes and sell them at the same time.

There had also been a dispute over outstanding rent at the Ormskirk shop that we had sub-let. The woman who took it on refused to pay the rent because of a repair that had not been done. She moved out and left us with the bill. So, in what would be the first of many court appearances over the coming years, I was made bankrupt. I was distraught. But when I got my head around it I realised that things weren’t as bad as I had at first thought.

By this time Kenny had sold his business and he suggested that I put my business in his name, which of course meant that, effectively, I would be working for him. Businesswise it did seem to be the only way forward. We had a big house with loads of land, and a big garage too, so I was able to bring all the girls to work there, and that meant we could cut down on overheads.

The only difference was that when I had to go and buy fabric in Manchester Kenny would have to sign blank cheques for me to take, as he was in charge of the business bank account. Eventually it became impossible for me to have all the cheques I needed every time I wanted to buy something, so I would just sign them in his name. I thought he was fine with that – it wasn’t a big deal. Not then, anyway.

After the last robbery at the Liverpool shop, the police finally caught the thieves, so as part of the insurance claim I had to go to court to confirm that these people had no permission to be in my shop. As I was going up to the courtroom in the lift, two policemen and a young lad got in. I heard them talking and this lad – he must have been about 20 – looked at me and said: ‘Was it your shop we robbed?’

‘Yeah,’ I said, looking at him, surprised.

‘No offence, love, but you didn’t half pile it on there, did you?’ he said, trying to make out that our claim was higher than the shop stock was worth.

‘It’s all expensive designer stuff, you know,’ I said, affronted.

‘Ah well, nothing personal,’ he smirked.

Then, as the lift stopped and the police started to usher him out, do you know what the cheeky little get did? He turned to me and asked: ‘Sure you don’t want any videos or owt?’ Some people just can’t help themselves, can they?

But it was around this time that everything started to really go wrong. Since Kenny had sold his business he wasn’t working and so he was getting up at around midday and then going out and not coming back until early hours in the morning. I’d still be working in the garage, and he’d pop his head around the garage door and say, ‘You still working?’

‘Yes, I’m still working,’ I would think to myself, looking at him. ‘I’m the only one in this house working.’ In fact I was working all hours to try and rebuild the business and to keep the family going, after he had sold his business. But the bank account was in his name. I was still bankrupt and now Kenny was in control.

Our marriage had been rocky for a while, and the children were growing up. Hayley, my youngest, was now 12, Tracey was 19, and my son Kenny was 20. He had moved into a flat with his girlfriend, and they had just had a baby, Daniel – my first grandchild.

So, after years of always being at home or working all hours, I started going out with Pauline on Friday nights. Pauline understood what I was going through with Kenny and tried to take my mind off things. She is a good singer and she liked to enter all the pub karaoke competitions. They were a really big deal in Liverpool pubs at the time and you could earn good money if you won.

I started going with her on Sundays too, and Kenny didn’t like it. By this time, though, I didn’t care that we didn’t do anything together. Then I heard that he was seeing someone else. Had I been told that a few years back I would have been devastated, but I had started building a life of my own by then and I was enjoying my evenings out with Pauline. In the end, me and Kenny were just keeping up appearances, but because we had Hayley, who was still quite young, to think about, we kept going. I wanted her to be brought up by two parents, her mum and dad, like her brother and sister had been.

And, on the face of it, me and Kenny had the perfect marriage – big house, nice car, lovely kids. But he had let me down time and again. He just couldn’t take the responsibility of looking after a family, and I was the one who was left to do that. But boy, did he make me suffer.

Still, we lived in a lovely house in a nice area. How could I take that away from my kids? The thought of it made me stay in my marriage far longer than I knew I should.

Then, one Friday night, Kenny came home and said he wanted to talk. He was all dead nice and said, ‘Listen, I don’t want to keep going out on my own, and I want you to stop doing that too.’

I looked at him and said, ‘No, I don’t want to stop. If you want to stop going out then that’s up to you, but I’m not.’ I knew then that there was nothing left between us. It was the end. I had spent so many years doing what he wanted and being frightened not to. Now it felt easy; I wasn’t scared to say what I wanted.

The following Monday morning, me and Pauline and the other girls in the Central Station shop were all standing around talking and catching up on the weekend. No one was more surprised than me to see Kenny coming up to the shop. He opened the door and walked right up to me. ‘My shop – give me the keys,’ he barked.

His shop! Yes it was in his name, but it was my mum’s money and my hard work that built up the business. Still, I picked them up, looked straight at him and said, ‘Here you are.’ Then I turned around and said, ‘Come on, girls,’ and we walked out of the shop.

Kenny just stood there, watching. Me and the girls, who were a little bit in shock, went around the corner to this little café. Then we phoned the Indian fella who owned the shop opposite ours and asked him to look across to see what Kenny was doing.

‘Can you see anything?’ we kept asking him. ‘What’s he doing now?’ He said he could see loads of women coming into the shop. It was Communion time, so it was one of our busiest periods. We were all laughing at the thought of Kenny standing there with his hands open, not knowing what to do. But I just thought, ‘You know what, let him have it.’ And I did. He got the shop, but I felt free.

Just after that Kenny moved out and set up home with his girlfriend.

Apart from the kids, the business was his last hold over me. He couldn’t do anything then. Nothing. The shop closed down pretty soon after. But I couldn’t sleep for thinking about the customers who had come to us to have their Communion dresses made. I still had all the numbers and all the books, so I chased up the girls who had left deposits and said, ‘OK, no problem. I’ll do your dress for you and deliver it when it’s done.’ But we hadn’t managed to contact all the people, so I rang the local radio station and asked them if they could do a little appeal, asking the people I couldn’t contact to get in touch with me. They read it out over the air, and it worked! I managed to finish every order. At night, I’d jump in the car with Pauline and go round delivering them all.

Kenny still came to the house, and each time he came he would take more and more away with him. One September night he came to the house, picked up my car keys and drove off in our car.

It was my car too – I had bought it with money I had earned – but it was in his name. The worst thing about that was that we lived in a place that was quite out of the way, so I really needed a car to get around and to ferry Hayley about to all her mates’.

I was really upset by that. I called Pauline to tell her that I wouldn’t be able to come and see her sing in the karaoke final. But she wasn’t having any of it. ‘Get down here now,’ she said. ‘Don’t sit there on your own, crying – that’s just what he wants. Get a taxi and I’ll pay for it when you get here.’ She was right. I called the taxi.

That night Pauline introduced me to Ruth, a woman she had met at some of the singing competitions. Pauline had told Ruth what was happening with me and Kenny, and Ruth asked me more. I spent most of that evening pouring my heart out to her.

‘What’s your biggest problem?’ she asked me, trying to get some perspective on the situation.

‘Well, apart from the fact that I’ve no car, no business, no money, and am bankrupt, where do you want me to start?’ I said to her, with tears starting to run down my face.

On top of that, I’d just received a healthy amount of orders from my agent in Ireland that morning. ‘Now I’ll have to call her and tell her that I can’t do them,’ I said to Ruth. To my amazement she offered to help.

‘What do you need to fulfil the Irish orders?’ she asked.

‘About £5,000 for fabric and a car to go to the warehouses,’ I told her.

‘Come and see me tomorrow,’ she said. I couldn’t believe it. Here was a complete stranger offering to help me. I suppose alarm bells should have rung then, but I was probably the most vulnerable I’d ever been and I needed a lifeline. I needed someone to hold on to.

I went to Ruth’s house and she told me her plans. Her boyfriend would lend me the money I needed, and she suggested that, rather than me carrying on by myself, she and I could go into business together. She told me she had a business degree, so if I made the dresses she could look after the financial side of things. She set up a bank account in the name of My Fair Lady and rang the agent in Ireland explaining that she would be dealing with the business while I got on with the dressmaking. She set up credit accounts with some of the suppliers too.

When she came to my house one night to drop off some fabric, her jaw dropped when she saw where I lived. ‘I used to live in a house like this, about fifteen years ago,’ she told me, her voice filled with regret. ‘That’s until my ex-husband kicked me and the kids out on Christmas Eve.’ Ruth went on to tell me more about her past life. I felt for her – her story sounded so similar to mine.

The next day I made a start on the orders. That evening Ruth arrived at my door in floods of tears. Her boyfriend had run off with everything in the house, she told me, including my computer and other things I had lent her to get the business up and running.

I tried to calm her down. She said she would think about how to get the money and then she said, ‘Have you got any jewellery that we could pawn? It will keep us going until we get the money together.’ I had never been in a pawn shop in my life and didn’t know what to do. ‘Give it to me and I’ll sort it out,’ Ruth convinced me. In the meantime, in my desperation I turned to the only person I could and asked my Aunty Gladys to lend me £3,000 to keep things going.

We bought more fabric with the money and I carried on with the orders. ‘We should open a stall on the market with the old stock from your garage,’ Ruth suggested. So we did. She set up at Paddy’s and started selling there on Saturdays. Things went well for a bit, but then trade started to slow down when the First Communion season came to an end. So Ruth found a unit in another retail space and I started to make christening outfits for her to sell in it. But I had started to feel a bit unsure of Ruth, as she was becoming over-friendly. Then Ruth and Pauline stopped getting on and Pauline stopped working with us.

All this time, Tracey and Hayley were still in the family home. But I had no money whatsoever, not a penny, and I had to keep working to supply the shop as I needed to keep the house going. I also wanted to pay my aunty back as soon as I could. It was tough. In fact, it was turning out to be the hardest winter I’d had.

It’s funny how things work out, though, because me and my kids ended up having a cracking Christmas that year. When I was with Kenny, and used to consider leaving him, I would say to myself, ‘What would you do at Christmas?’ But we had a ball.

The house was massive and we didn’t have any oil for heating, and it was freezing, so the only thing for it was to go to the pub – me, Hayley, Tracey and her boyfriend. I stuck a duck in the oven and we all went for a couple of drinks (though, of course, Hayley was only drinking Coke). By the time we got back from the pub the duck was burnt. But we ended up playing games and having such a good laugh together that it didn’t matter. We had no money but we had a good time.

A couple of days into the new year I got a call from Audrey, the seamstress who had worked for me and taught me in the early days. She told me that Ruth had been in touch, asking if she and one of the other girls wanted to come and work for her, because I didn’t want to do the dresses any more. Ruth was trying to cut me out. I went down to see her in the unit. I was livid. ‘I want nothing more to do with you,’ I screamed at her.

And then it just clicked: I was the business. Without my skills, my contacts and the generosity of my family, Ruth’s ‘business’ would never have got off the ground. Had I not been at such a low point that night I met her in the pub, and had I looked at things calmly instead of getting in a panic about what was happening with Kenny, I could have done everything myself. It dawned on me then that all I had done was to replace a controlling husband with a controlling friend.

‘I’m taking over the stall in Paddy’s,’ I told Ruth. ‘You can keep everything else.’

3

The Tale of My First Big Fat Gypsy Wedding Dress

So that’s how I came to be at Paddy’s all these years ago. Now it was January 1997 and my trickle of travellers had turned into a stream.

One Saturday, one of my regular gypsy customers came up and pointed at a dress. ‘I’m going to a wedding. Can you do this for her?’ she asked, looking down at her little girl.

‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘no problem,’ and started measuring up.

‘Can you do me one for the next wedding too? It’s my brother’s wedding next.’

‘Bloody hell,’ I said, looking up at her. ‘There’s a wedding every week in your family. How often do you go to weddings?’

‘Oh, nearly every week,’ she said. I just laughed.

The stall was getting more and more crowded, and Saturdays were becoming a bit intense. Some days it felt as though I’d done thousands of orders. I’d be measuring up one kid and then some other woman would say, ‘Over here, love, will you do her one, love?’ And I’d be like, ‘Yeah, yeah,’ trying to write the other measurements down.

‘Measure here, love, measure here,’ another voice would pipe up. Then I’d look and there would be four of them behind the counter, and a baby.

‘Don’t touch, don’t touch,’ I said, trying not to sound too tetchy. They were my customers at the end of the day, and I wanted to treat them well. But, honestly, it was chaos, with kids running over there, under here … There were travellers all over the place.

Then the queues started. I’d open up at nine a.m. and soon a line would start to form. I used to feel guilty about keeping people waiting, so I’d ask if they wanted a cup of tea and send out the Saturday girl. ‘I’ll just deal with this and I’ll come back to you,’ I’d say. ‘Just give me a minute.’

Only it always took longer than I expected, because when it came to giving them the price for what they’d ordered the traveller women wanted to stand and haggle with me all day. Or I’d be in the middle of serving the next family, and the first family would come back and add to the order that we’d already agreed a price for.

‘Can you just do me a red one as well, love, put a red one on that?’ So, I’d be like, ‘OK, yeah,’ just so they’d go away and let me get on. And then she’d come back. ‘But I want a hat with it, love.’

I remember going home one night and taking all the stuff in from the van. I was sure that I’d lost something or that a couple of things had been stolen. Finally, I thought, ‘Jesus, I can’t do this on my own any more.’

Don’t get me wrong, I was really happy about the way it was all going, really happy, but I needed help. So Dave said he’d start coming down to the stall to give me a hand. Also, I needed him to take the money as I didn’t like having cash on me when I was leaving the market.

By this time Mary Connors, the traveller that I had struck up a friendship with at the start, had started to come to the stall a lot, almost every Saturday, and I’d started to recognise her, affectionately, as Gypsy Mary. She knew everybody. ‘Whatever I do, they’ll follow,’ she used to say. I knew that Mary was a bit of a queen bee, so I believed her. And she’d also taken to looking out for me: ‘You’ve got to be careful with her,’ she’d warn me about some other traveller. ‘Don’t give her this,’ she’d say. ‘Don’t give them that.’ She was full of good advice, was Mary.

She was kind but with a tough heart, you know. So there was an element of the ‘If I do this for you, you do that for me’ sort of deal. ‘Don’t charge me what you charge them, and I’ll get you more business,’ she’d promise. You wouldn’t mess with Mary. She had six daughters, and every Christmas or Easter, or whenever there was a celebration, she’d have dresses made for the youngest ones. So, to be fair, she had bought quite a lot from me. Dave had even been down to a site she was living on in Manchester to deliver dresses to her. He used to come back and say that Mary and her family always made him feel welcome.

Mary’s youngest – Josephine – must have been about eighteen months. Josephine was adored by all the family and Mary used to buy loads for her. But the thing I remember most about Mary’s girls was that every one of them was stunning: they were all tall and slim, with long, flowing hair.

I hadn’t seen her for a while, and then one day at the end of January she turned up at the stall. ‘Our Mary’s getting married. She’s been asked for,’ she said, ‘and I want you to do the wedding dress.’

‘Oh God!’ I thought. My stomach turned over. It was January and the First Communion season hadn’t really kicked in yet, but it was about to. I’d done a wedding dress for a cousin of mine, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to do weddings as a business thing. I didn’t really want to do adult dresses at all. I was quite happy doing the little ones. I’d even taken the cutoff age down from seven to six after all the gypsies started asking for bigger dresses. Anyway, I could do the kids’ stuff with my eyes shut by then, because I knew what to do and where to get everything, but I really didn’t want to do big ones.

Also, I liked the idea of having my weeks free and not having to be on the stall until Saturday, so that I could really concentrate on new designs. I loved studying to find new styles and it was great having time to have a really good look through all my history books. I’d study the costumes in them for hours, looking at every detail and the different braids and edgings, working out how I could apply all that fine decoration to my designs.