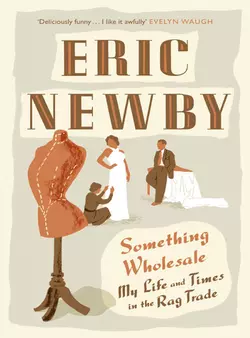

Something Wholesale

Eric Newby

Veteran travel writer Eric Newby has a massive following and is cherished as the forefather of the modern comic travel book. However, less known are his adventures during the years he spent as an apprentice and commercial buyer in the improbable trade of women's fashion.From his repatriation as a prisoner of war in 1945 to his writing of the bestselling ‘A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush’ in 1956, Eric Newby’s years as a commercial traveller in the world of haute couture were as full of adventure and oddity as any during his time as travel editor for the Observer.‘Something Wholesale’ is Newby's hilarious and wonderfully chaotic tale of the disorder that was his life as an apprentice to the family garment firm of Lane and Newby, including hilariously recounted escapades with sudden-onset wool allergies, waist-deep predicaments in tissue paper and the soul-destroying task of matching buttons. In addition to the charming chaos of his work in the family business, it is also a warm and loving portrait of his father, a delightfully eccentric gentleman who managed to spend more energy avoiding and actively participating in disasters than he did in preserving his business.With its quick wit, self-deprecating charm and splendidly fascinating detail, this is vintage Newby - only with a garment bag in place of a well-worn suitcase.

ERIC NEWBY

Something Wholesale

My Life and Times in the Rag Trade

Dedication (#ulink_a8ade80b-3d6a-5e0d-8796-c61a8c3fb3b9)

To My Father

Splendid in Defeat

Contents

Cover (#ub9a83f7a-29f4-5d03-bbef-9049772a2737)

Title Page (#u3388e6b2-bb1f-5320-8977-f7c7d116cf2b)

Dedication (#u6831ae12-97f5-57fd-94eb-48c3a6456038)

Preface (#ud34d4db3-5904-5412-9c55-a7e20c53ae72)

1. A Short History of the Second World War (#u08128959-b335-5493-bd3e-81c6017e2b9f)

2. An Afternoon at Throttle and Fumble (#uf1367932-e27d-5b28-b57b-eec30764bf14)

3. Life with Father and Mother (#u0b3ee31c-ed11-5634-9280-70174652d15c)

4. Old Mr Newby (#u597142f9-3bf7-5578-b652-e5fa98cf0acd)

5. Back to Normal (#u0c19f996-57c6-5c4a-a6c2-8748a154c9c1)

6. In the Mantles (#ud91c0f85-f585-52b6-9ef1-dd9788dd9206)

7. All Bruised (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Sir No More (#litres_trial_promo)

9. George’s Boy (#litres_trial_promo)

10. A Day in the Showroom (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Export or Die (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Something Wholesale (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Hi! Taxi! (#litres_trial_promo)

14. A Nice Bit of Crêpe (#litres_trial_promo)

15. North with Mr Wilkins (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Caledonia Stern and Wild (#litres_trial_promo)

17. On the Beach (#litres_trial_promo)

18. A Night at Queen Charlotte’s (#litres_trial_promo)

19. A Man Called Christian (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Birth of an Explorer (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Lunch with Mr Eyre (#litres_trial_promo)

22. The End of Lane and Newby (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Model Buyer (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue – The Last Time I Saw Paris (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_843c9e1c-e205-5f19-8f0c-6ccaf5dd316e)

The hero of this book, if it has one, is the man who, during the years it describes, was head of the dressmaking firm of Lane and Newby – in other words my father. But this was my father in old age. We were separated by a great gulf of years, and when I was old enough to appreciate him the world which he knew and of which he was a part had passed away.

What do I know of my father as a young man? Practically nothing. His father came from the East Riding of Yorkshire and he acquired a stepmother at an early age. I know that with her his life was not very happy. It was one of the few things that when he spoke of it moved him to tears.

I look at photographs of him in our family albums taken when he was twenty or so – great group photographs of men and girls upriver, perhaps, after an outing or a regatta – and wonder what he and his companions were really like. He was very handsome, this is obvious – with a fine, well-tended moustache – and he was elegant, either in a negligent manner with a silk handkerchief knotted round his neck and a panama hat with the brim turned up in the front or else more formally in a dark suit with a watch chain and a straw hat with a black band.

The girls are dressed to the nines with fichus of lace and hats like great presentation baskets of fruit from Fortnums.

They must be upriver. In the background of the particular picture of which I am thinking there is a white clap-boarded house. It is probably a club-house or it might be a mill and beyond it the woods are thick and green, like the Quarry Woods at Marlow, only the house is not at Marlow.

Where is it? I wish I knew. There is no one left to ask. Perhaps, somewhere, one or two of those young men and women are left alive, but they would be very old now.

Some of the girls must have been beautiful but one must make an effort of will to believe it. Their clothes makes them seem older than they really were. And the way in which the photographer took his pictures endows them with too much chin, or else no chin at all. They look absurdly young or else like maiden aunts. The effort of keeping still for the photographer on that warm summer’s day and looking into the sun was too much for them, particularly for the men. Some of them are squinting, some are out of focus, some have an air of being slightly insane. It is gratifying to see that in all these groups my father took the precaution of seating himself next to the most good-looking girl available. I would like to know how they spoke, these friends of my father; the idioms they used; the things that made them laugh; but I shall never know, more’s the pity and neither will my children.

There are more rural scenes. Photographs taken not by a professional but by one of my father’s companions when they were camping, in the doorway of a tent, early in the morning with the mist still rising from the meadows. They look dishevelled, as if none of them had slept well, perhaps there were horses in the field. One of them is smoking a meerschaum pipe with a Turk’s head carved on it. In the foreground there is a large black cooking pot, suspended from a metal tripod, simmering over a wood fire. All the cooking equipment is tremendously heavy. How did they get it there? They must have used a horse-drawn vehicle. It is a pity that there is no picture of it.

There is a series of photographs taken off the East Coast in a yacht with a hired man. ‘He was a real old salt,’ my father told me. In these pictures he and his friends are all wearing black and white striped trousers rolled up to the knees and stockinette caps. In the background of one of them there is a light-ship and close to it a barquentine, deep-loaded, running before the wind. Whoever took the photograph had difficulty with it because the horizon goes rapidly downhill! ‘There was a bit of a lop on,’ my father said, wistfully. He had always wanted to be a sailor. And when his father married again he tried to run away to sea but was brought back in a cab. Next in time are the photographs of my mother taken the year before I was born, looking gentle and rather sad, and another of my father looking severe and bristly reclining on a velvet cushion up in the bows of his skiff. I wonder how things went that day. Was she having sculling lessons at that time? Perhaps she wasn’t getting her hands away properly.

The next photographs are of my father partially domesticated, taken on the beach at Frinton. I am on the scene now, large and shiny in a large, shiny pram. I look like an advertisement for some health food. I think my father has just arrived from London on the afternoon train. He is dressed for London. Looking at the photograph now I almost convince myself that I remember the moment when it was taken. But who took it? I seem to remember a nurse with starched cuffs and dark rings under her eyes who used to have assignations with old men in the local cemetery when she was supposed to be giving me an airing, and was summarily fired for it. Perhaps she took the picture.

There are pictures on Sark. I am sitting on my father’s head as he wades through the bracken. It was an enchanting spot in the Twenties. There are a lot of photographs of the Twenties. My mother in a cloche hat at Deauville. Scenes at Branscombe in Devonshire of two sisters, both store buyers, Lolly and Polly, friends of my parents, identical in long jerseys and strings of beads, surrounded by a whole pack of Pekinese.

Lolly was the best suit buyer in London. She was extremely good-hearted but could be extremely autocratic. On one occasion a customer had a suit on approval and, thinking that she would not be detected, wore it at the Royal Military Meeting at Sandown Park, where she was seen by Lolly, who was mad about racing.

On the following Monday the customer returned to the store and complained that the suit which she was wearing had some imperfection in it and demanded a reduction in price.

‘If there’s something wrong with it,’ said Lolly, ‘then you shan’t bloody well have it.’

She made her take it off in a fitting-room. ‘Now bloody well go home without it!’ she said.

Eventually the customer had to buy another suit in order to leave the building, one that was even more expensive than the original, which Lolly promptly marked-down in price and appropriated to her own use, having wanted it for herself in the first place.

There is a whole gallery of memorable characters in these albums. Captain and Mrs Buckle – Mrs Buckle smoked a hundred cigarettes a day. ‘Gaspers’ she used to call them, and her voice was reduced to a hollow croak. Ivor – a young man who had an open Vauxhall with a boat-shaped body and used to drive to Devonshire in silk pyjamas after parties in London. He inherited a fortune when he was twenty-one, got through it in a year and became a bus driver. He used to wave to my mother when he drove the number nines over Hammersmith Bridge. And there is another buyer called Phyll – who lived in sin with someone called Uncle Fred, who wasn’t an uncle. At Christmas time Auntie Phyll’s flat resembled a robber’s cave with presents from manufacturers piled high in it. Those were days when a fashion buyer was expected to feather her nest (nobody else was going to do it for her) and many a buyer was able to retire to a riverside cottage on the proceeds of the toll she exacted from the manufacturers on every dress that went into her department. On one occasion a disgruntled manufacturer informed the management that Auntie Phyll was taking a percentage in this way but was nonplussed when he was told by the Managing Director that they didn’t care what bribes she received providing that the clothes she bought were as well chosen and as cheap as those of their competitors.

And there is a whole supporting cast of rural characters from the village where we had taken a cottage for the summer. Photographs of the innkeeper, who was having a violent affair with the barmaid under the nose of his wife; photographs of his wife and the barmaid, who looks very innocent in a velvet dress, and pictures of village children with whom I used to float paper boats down an open sewer; and the policeman’s son who taught me to say bloody. Once for a bet I drank the water from the sewer. The results were not what normal medical experience would lead one to expect. Instead of contracting dysentery I had a complete stoppage of the bowels that lasted for more than a week.

And there is the last photograph I have of my father. He is sitting with my mother in an umpire’s launch on the river at Hammersmith. It is the summer of the year he died. He has shrunk with the years, but with his white club cap he looks for all the world like a mischievous schoolboy.

CHAPTER ONE A Short History of the Second World War (#ulink_7a781cae-682a-5e26-9bdc-584b3d953d9e)

One morning in August 1940 ‘A’ Company, Infantry Wing, was on parade outside the Old Buildings at the Royal Military College, Camberley. Company Sergeant-Major Clegg, a foxy looking Grenadier, was addressing us ‘… THERE WILL BE NO WEEKEND LEAF,’ he screamed with satisfaction. (There never had been.) ‘That means no women for Mr Pont, Mr Pont (there were two Mr Ponts – cousins). Take that smile off your face Mr Newby or you’ll be inside. Wiring and Demolition Practice at 1100 hours is cancelled for Number One Platoon. Instead there will be Bridging Practice. Bridging Equipment will be drawn at 1030 hours. CUMPNEE … CUMPNEEEE … SHAAH!’

‘Heaven,’ said the Ponts as we doubled smartly to our rooms to change for P.T. ‘There’s nothing more ghastly than all that wire.’

I, too, was glad that there was to be no Wiring and Demolition. Both took place in a damp, dark wood. Wiring was hell at any rate and Demolition for some mysterious reason was conducted by a civilian. It always seemed to me the last thing a civilian should have a hand in and I was not surprised when, later in the war, he disappeared in a puff of smoke, hoist by one of his own petards.

In June 1940, after six months of happy oblivion as a private soldier, I had been sent to Sandhurst to be converted into an officer.

Pressure of events had forced the Royal Military College to convert itself into an O.C.T.U., an Officer Cadet Training Unit, and the permanent staff still referred meaningfully in the presence of the new intakes to a golden age ‘when the gennulmen cadets were ’ere’.

‘’Ere’ we learned to drill in an impressive fashion and our ability to command was strengthened by the Adjutant, magnificent in breeches and riding boots from Maxwell, who had us stationed in pairs on the closely mown lawns that sloped gently to the lake. A quarter of a mile apart, he made us screech at one another, marching and countermarching imaginary battalions by the left, by the right and by the centre until our voices broke under the strain and whirred away into nothingness.

Less well we carried out a drill with enormous military bicycles as complex as the evolutions performed by Lippizanas at the Spanish Riding School. On these treadmills which each weighed between sixty and seventy pounds, we used to wobble off into the surrounding pine plantations, which we shared uneasily with working parties of lunatics from the asylum at Broadmoor, for T.E.W.T.s – Tactical Exercises Without Troops.

Whether moving backwards or forwards the T.E.W.T. world was a strange, isolated one in which the lunatics who used to wave to us as we laid down imaginary fields of fire against an imaginary enemy might have been equally at home. In it aircraft were rarely mentioned, tanks never. We were members of the Infantry Wing. There was an Armoured Wing for those who were interested in such things as tanks and armoured cars and the authorities had no intention of allowing the two departments to mingle. Gradually we succumbed to the pervasive unreality.

‘I want to bring home to you the meaning of this war,’ said a visiting General. ‘In four months those of you who are not R.T.U.’d – Returned to your Units – will be platoon commanders. In six months’ time most of you will be dead.’

And we believed him. Our numbers were already depleted by a mysterious outbreak of bed-wetting – an R.T.U.-able offence. In a military trance we imagined ourselves waving ashplants, charging machine-gun nests at the head of our men. The Carrara marble pillars, which supported the roof of the chapel in which we carried out our militant devotions, were scarcely sufficient to contain the names of all those other ‘gennulmen’ who, in the earlier war, had died in the mud at Passchendaele and among the wire on the forward slopes of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. They had sat where we were sitting and their names were set out in neat columns on the pillars like debit entries in some terrible ledger.

This dream of Death or Glory affected our leisure. Most of us had passed our formative years in the outer suburbs. Now, to make ourselves more acceptable to our employers we took up beagling (the College had the Eton Beagles for the duration); ordered shirts we couldn’t afford from expensive shirt-makers in Jermyn Street and drank Black Velvet in the Hotel. The snugger pubs were out of bounds for fear we might meet a barmaid who ‘did it’. No one but a maniac would have wanted to do it with the one at the Hotel.

The bridging equipment was housed in a low, sinister-looking shed near the lake on which we were to practise. This was not the ornamental lake in front of the Old Buildings on which, in peace time, playful cadets used to float chamber pots containing lighted candles – a practice now forbidden by the blackout regulations. It was an inferior lake, little more than a pond; from it rose a dank smell of rotting vegetation.

Inside the shed there were a number of small decked-in pontoons and strips of heavy teak grating which were intended to form the footway. Blocks and tackle hung in great swathes from the roof; presumably they were to hold the bridge steady in a swiftly flowing stream. Everything seemed unnecessarily heavy, as though it was part of the gear of a wooden ship-of-the-line.

There was every sign that the bridge had not been used for years – if at all. The custodian, a grumpy old pensioner rooted out of his cottage to open the door, confirmed this.

‘What yer think yer going to do with it, cross the Channel?’ he croaked.

The Staff Sergeant detailed to instruct us in the use of the bridge was uneasy. He had never seen anything like it before. It bore no resemblance to any kind of bridge that he had encountered.

‘It’s not an ISSUE BRIDGE,’ he kept repeating, plaintively. ‘Gennulmen, you must help me.’ We were deaf to him. The Army had seldom been kind to us; it was too late to call us gentlemen.

Finally, after rooting in the darkness he discovered a battered manual hanging on a nail behind the door. It confirmed our suspicions that the bridge had been constructed at the time of the Boer War. No surprise at the Royal Military College where a whole literature of the same period – text books filled with drawings of blockhouses with corrugated-iron roofs; men with droopy moustaches peering through loopholes; and armoured trains that I associated with the early life of Mr Winston Churchill – were piled high on the tops of cupboards in the lecture rooms and had obviously only recently fallen into disuse.

With the manual in his hand the Sergeant was once more on familiar ground – if one can use such an expression in connection with a bridge. His spirits rose still further when he discovered that there was a drill laid down for assembling the monstrous thing.

‘On the command “One” the even numbers of the front ranks will about turn, grasp the Caissons with both hands and advance into the water. On the command “Two” the odd numbers of the front rank will peg out the Guys, Retaining Caisson. On the command “Three” the even numbers of the rear rank will pick up the Sections, Decking’ … and so on.

On the command ‘One’ the Caisson Party, of which I was one, moved gingerly into the water, which was surprisingly warm. Some of the more frivolous cadets began to splash one another, but were rebuked by the Sergeant. After some twenty minutes all the Caissons were in position, secured by block and tackle.

‘Caisson Party, about turn, quick march!’ To the accompaniment of weird sucking noises we squelched ashore.

‘Decking Party, advance!’ The Decking Party staggered forward under its appalling load. Standing on the bank, with the water streaming from the bottoms of our trousers, we watched them go.

‘It all seems rather pointless when we’ve already walked across,’ someone said.

‘Quiet!’ said the Sergeant. ‘The next cadet who speaks goes on a charge.’ He was looking at his watch, apprehensively.

‘Decking Party and Caisson Party will retire and unpile arms,’ he went on. We had already performed the complicated operation of piling arms. It was one of the things we really knew how to do. ‘Now then, get a move on.’

We had just completed the unpiling when Sergeant-Major Clegg appeared on the far side of the lake, stiff as a ramrod, jerkily propelling one of our gigantic bicycles. Dismounted, standing half-hidden in the undergrowth, he looked more foxy than ever.

He addressed us and the world in that high-pitched sustained scream that even now, when I recall it at dead of night twenty years later, makes me come to attention even when lying in my bed.

‘SAAAAN ALUN!’

‘SAAAAH!’

‘DOZEEEE … DOZEEEE … GET THOSE DOZY, IDUL GENNULMEN OVER THE BRIDGE … AT … THER … DUBBOOOOL!’

‘SAAAAH!’ shrieked Sergeant Allen and wheeled upon us with a face bereft of all humanity. ‘PLATOOOON, PLATOOOON WILL CROSS THE BRIDGE AT THER DUBOOL – DUBOOOOL!’

Armed to the teeth, bowed down by gas masks, capes antigas, token anti-tank rifles and 2” mortars made of wood (all the real ones had been taken away from us after Dunkirk), we thundered down the bank and on to the bridge.

The weight of thirty men was too much for it; there was a noise like a succession of pistol shots as the Guys, Retaining Caisson parted, the central span of the bridge surged away and the whole body of us crashed into the water. It was like the end of the Gadarene Swine, the Tay Bridge Disaster and the Crossing of the Beresina reproduced in miniature.

As we came to the surface, ornamented with weed and surrounded by the token wooden weapons which, surprisingly, in spite of their weight, floated, we began to laugh hysterically and what had begun as a military operation ended as a water frolic. The caissons became rafts on which were spread-eagled the waterlogged figures of what had until recently been officer cadets, who now resembled nothing more than a band of lascivious Tritons. People were ducking one another; the Ponts were floating calmly, contemplating the sky as if offshore at noon at Eden Roc …

Gradually the laughter ceased and a terrible silence descended on us. A tall ascetic figure was looking down on us with a mixture of incredulity and disgust from an ornamental bridge in the rustic taste. The Sergeant was saluting furiously; Sergeant-Major Clegg, foxy to the last, had slipped away into the undergrowth – only his bicycle, propped against a tree, showed that he had ever been there. The face on the bridge was a very well-known face.

Without a word General de Gaulle turned on his heel and went off, followed by a train of officers of high rank. His visit had been unannounced at his special request so that he could see us working under natural conditions. What he must have thought is unimaginable. France had just fallen. It must have confirmed his worst suspicions of the British Army. Perhaps the intransigence that was later to become a characteristic was born there on that bright morning beside a steamy little lake in Surrey.

For Sergeant Allen the morning’s work had a more immediate significance. His career seemed blasted.

‘You’ve gone and done me in,’ he said sadly, as we fell in to squelch back to the Old Buildings.

Four years, seven months and twenty-five days after that first abortive amphibious operation amongst the Camberley pines I stood on the dockside at Tilbury, the last of the last boatload of returning prisoners from Oflag 79.

I was much changed since that far-off day when Company Sergeant-Major Clegg had told me to take that smile off my face. Then, at least, I had been a soldier in embryo. Now, wearing a suit of battle dress that had been made for a giant, sprinkled liberally with delousing powder, which the authorities at Brussels had thought necessary before allowing me out to eat an ersatz gooseberry tart on Boulevard Anspach, I resembled nothing human, civil or military.

En masse, my companions and I were not objects of compassion. Ten days of liberty during which we had roamed the countryside of Saxony, searching for food that the local farmers had been too terrified to withhold from us, had so inflated our faces that they resembled grotesque balloons at a carnival, in startling contrast with our emaciated bodies, which were concealed by our uniforms.

Unlike the returned prisoner of popular imagination we were heavily laden: with kitbags stuffed with coats and great rubber riding mackintoshes bought at officers’ shops along the route, and with long woollen underpants that had been pressed upon us by helping organisations. In addition I was encumbered with a number of scientific instruments which I had looted from a German experimental station, under the impression that they would make my fortune, and, heaviest of all to bear, an anxiety neurosis brought on by my failure to complete, before liberation, a petit-point fire screen, one of thousands sent out by the Red Cross with the express purpose of allaying anxiety neurosis. I still have the instruments. No one has ever been able to tell me what they are intended for. I burned the fire screen and felt better for having done so.

It began to rain heavily. ‘Officers this way,’ said a sergeant from the disembarkation staff and we trailed after him under the arc lights, across greasy railway tracks on which tank engines hissed with steam up, to a long, low, wooden hut. Inside the other ranks were already eating bacon and eggs and drinking tea which was being served to them by cheerful, common ATS.

We were given tea by members of a more fashionable volunteer organisation whose roots were deep in S.W.7. They seemed more interested in the effect that they were producing on a number of men, who had not seen an English woman for anything up to five years, than in producing the victuals for which we still craved.

‘Do you know Jamie Stuart Ogilvie-Keir-Gordon in the Scots Guards? I think he was with you.’

‘No, I’m afraid not.’

‘Or Binkie Martyn-Sikes?’

‘No!’

‘How very odd that you shouldn’t have known him. He’s my second cousin.’

‘Do you think it would be possible for me to have something to eat?’

‘Oh, how stupid of me. It’s been so interesting talking to you I quite forgot.’

Whilst we were eating a Colonel entered. He was large, with a face as red as the tabs on his lapels.

‘Carry on, gentlemen,’ he said, genially. No one had in fact stopped. His costume was an unconvincing parody of a panoply which I now associated with a long-dead past. Neither breeches nor boots were as those worn by the terrifying but beautiful Eddie, our Adjutant at Sandhurst. Particularly the boots; they were downat-heel as though they had been worn over-much on urban pavements.

He sat himself down on the edge of one of the tables and tapped his awful boots with a little swagger cane.

‘Before you chaps move on from here,’ he said with a bonhomie which we found extremely distasteful, ‘there is just one thing I would like to say to you.

‘We realise here that things have been pretty rough for you on the other side. The Hun’s finished, now it’s our turn. I expect you saw some pretty rotten things – atrocities. I happen to be the Commandant of a P.O.W. Camp at—(he named a place somewhere remote in East Anglia). I’m also,’ he added, surprisingly, ‘a Member of Parliament. If you’ve witnessed any kind of atrocity in the last few years I would like you to report it to me, now. I promise you that whatever you tell me here will be brought home to the men in my camp. They’ll sweat it out.’

It had been a long day. I thought of the journey we had made through Belgium. There had been a shortage of rolling stock and we had entrained in carriages intended for the transportation of German prisoners. The windows were festooned with barbed wire. At the halts, which were numerous, small boys had thrown stones at us under the impression that we were members of the opposition. Who was to blame them? I thought of Germany – how I loathed pine trees and Alsatian dogs. I thought of the camp near Munich: the S.S. stripping Yugoslav men and women, kicking them round the compound in the snow and later singing harmoniously together in their huts, full of gemütlichkeit. I had seen a lot of things and this was too much.

Finally, an officer, who had been captured with the Rifle Brigade at Calais in 1940, got to his feet.

‘Colonel,’ he said, ‘I have two observations to make. The first is that you yourself are, without doubt, the biggest atrocity I have seen in the last five years. Secondly, the sooner there is a by-election in your constituency the better.

‘And in case,’ he went on, ‘you are now thinking of having me placed under arrest I will tell you that I have not yet been medically examined and I am probably quite insane – and that, Colonel, goes for everyone else in this room.’

There was a long, long train journey from Tilbury to Sussex without changing – a tour-de-force only possible in time of total war; the train stopping in the small hours of the morning at a disused platform deep in the bowels of Holborn viaduct.

‘Hasn’t been used since 1918,’ said the guard. He stood on the platform ankle deep in black soot, the accumulation of twenty-seven years, whilst those of us who lived in London argued whether or not to abandon the train and take taxis.

‘Can’t get a taxi in London after midnight – Yanks,’ said a gloomy looking Major with a handlebar moustache and little tufts of ginger hair growing out of his cheeks. ‘Had a letter from m’brother.’ At dawn the train crept into Barnes Station. I lived at Hammersmith Bridge, five minutes away by bus. It seemed ridiculous not to get out. I started assembling my extraordinary luggage. ‘Chap told me at Tilbury,’ the hairy Major said, ‘that they’re giving out special food and clothing coupons at Repatriation Centres.’

The train moved forward with a shattering jerk. Once more the house where I was born receded into the distance.

The Repatriation Centre was two Nissen huts in the middle of a wood somewhere in Sussex. It was staffed entirely by escaped prisoners of war, most of whom we already knew. In one hour dead they had us medically examined, documented and back at the station.

‘You get two months’ leave. Personally I don’t think that anyone will ever want to see you again,’ said the C.O. He had been in the same squad with me at Sandhurst. ‘The thing is,’ he said, slipping effortlessly back into the idiom, ‘you look so very, very idul.’

CHAPTER TWO An Afternoon at Throttle and Fumble (#ulink_4136bb9c-1d3f-5538-ad82-70edaf919b8d)

‘It’s not the slightest use hanging about here all day doing nothing,’ my mother said firmly. ‘You’re becoming demoralised.’ She had come into the bedroom where I was skulking unhappily for what she called ‘a little talk’.

My leave was not proving to be as pleasant as I had expected it to be. Most of the girls I knew were in jobs they refused to discuss, alleging that they were ‘secret’. (At that time it was fashionable to be in something secret even though you were issuing camp beds at the White City.) By day I had been forced back on the company of a succession of predatory widows, who drew false hope from my air of melancholy and who listened with awe to the rumbling noises made by a stomach which had been unable to stand the strain of liberation. My friends all seemed to be prisoners of war, busy like me nursing their private neuroses and we had so much in common that we used to cross the road to avoid meeting one another.

Even the Army seemed to have lost interest. Four days after I arrived home I received a letter from a remote camp in Ayrshire. It was signed by the Adjutant and ordered me to report there forthwith for posting. Someone who knew the place told me that it was in a bog ten miles from a railway station. I disregarded the letter. Every Friday for two months I received a letter from the Adjutant. It was always the same letter, except for the date and no reference was ever made to the previous ones. Finally they ceased altogether. I felt slighted. ‘I’m very worried about you,’ said my mother, sitting down on the edge of the bed. ‘I’ve been speaking to your father and we both think that you must do something.’

‘I am doing something.’

She wasn’t listening. ‘We’re sending you to Sheffield,’ she said, ‘with the Gown Collection. Mr Wilkins is ill.’ (Mr Wilkins was the Traveller.) ‘There’s a new Buyer at Throttle and Fumble. She hasn’t been in to see us this season and we can’t afford to lose the account.’

Here I must explain that my parents were in the wholesale business, what is known in the trade as ‘The Better End’. Twice a year, Summer and Winter, they made a collection of Models, based until the war came, on something that was supposed to have happened in Paris (what heavier industries call prototypes), and invited the buyers of the big department stores and smaller enterprises, called ‘Madam Shops’, to visit London and place an order for the coming season. But not all the buyers came to London and some of those who did would pass my parents by. It then became necessary to stalk them on their own ground and make a killing there – this was where Mr Wilkins came in, but Mr Wilkins was ill.

I was not in the business myself and knew nothing about it but now my mother had me cornered. I couldn’t think of any reason why I shouldn’t go.

‘You can take Bertha,’ she added, ‘to show the gowns.’

Bertha was a free-lance model my parents employed to display their outsize clothes so that the buyers could make their choice under battle conditions. I had first met Bertha some weeks previously at a fashion show at a London hotel at which our firm was ‘showing’. My mother had insisted on me attending it on the grounds that ‘it would cheer me up’. Bertha was very outsize indeed and grunted as she eased herself down at our table after the show. She had fat little feet of which she was inordinately proud and quite soon Bertha was massaging my ankles with them under the table, like a mare scratching itself against an old post. I was absorbed in studying the model girls employed by less-specialised firms, who looked like racehorses, and in wishing that we were showing small sizes. Before she left, unasked she wrote her telephone number on my programme.

‘I’ll do anything,’ I said, ‘as long as it’s not with Bertha.’

‘Then you’ll have to show them on the hangers,’ said my mother. She sounded vexed. ‘But they won’t look the same without Bertha. She’s such a willing girl.’

‘I know, that’s why I’d rather show them in the hand.’

‘I think it will do you good to get away, dear,’ my mother said, as she got up to go, triumphant as usual. ‘Oh, and by the way, a Mrs Bassett has telephoned three times already. I said you were asleep.’

Two days later I arrived in Sheffield, by train. I was wearing a pre-war suit that was so full of moth holes when I first put it on that it looked as though it had been peppered with shot. My mother had had it neatly repaired in the workroom with wool of an odd shade of blue.

It was raining steadily and although it was only eleven o’clock in the morning the sky was almost as dark as night. With me were four enormous wicker baskets, things called ‘skips’, which contained the Gown Collection.

‘Commercial?’ demanded the man at Left Luggage. He was a gloomy-looking, hollow-eyed fellow. If it was always like this it was difficult to see how he could have looked otherwise.

‘No,’ I said. At this stage I was sensitive about my amateur status. ‘Have it your own way,’ he said. ‘Cheaper if they’re Commercial. It’s all the same to me if they’re full of corpses,’ and gave me a ticket.

My father had written to Throttle and Fumble announcing that ‘Our Mr Newby will be calling on you,’ but no reply had been received when I left London, so I telephoned.

‘Throttle and Fumble,’ a voice said at the other end and I pressed Button A. There was a click and I was disconnected. All attempts to gain the attention of the operator failed.

There was an interval while I bought a magazine I didn’t want in order to collect some change and a further wait in a queue for a telephone.

‘Throttle and Fumble,’ said the voice again.

‘I want to speak to the Gown Buyer.’

‘Speciality Model Gowns, Model Gowns, Dream Girl Room or Inexpensives?’ the voice said, archly. Confronted with such a choice I wasn’t sure.

‘Well, if you’re not sure, I can’t connect you.’

‘Speciality Model Gowns,’ I said, guessing wildly.

There was a whirring noise and a new voice said, ‘Throttle and Fumble, Dream Girl Room, Good morning.’

‘I want Speciality Model Gowns.’

‘Just a moment, I’ll have you transferred.’ There was a succession of tocking noises and yet another voice said, ‘Sorry to trouble you, dear, will you transfer this call to Specialitys.’

‘Hallo, Speciality Model Gowns? I want to speak to the Buyer.’

‘I’m Miss Flagstone, the Under Buyer. Miss Trumpet can’t be disturbed. She’s having a Fashion Parade. Whom do you represent?’

‘Lane and Newby of London. My name is Newby.’ Put in this way it sounded ridiculous.

‘Oh yes, we had a letter about you. You should have been here earlier. We don’t see Travellers after eleven o’clock, and Miss Trumpet has done all her buying. I’ll have to speak to her. She’s just going to coffee. Are they nice dresses?’

‘All the dresses are very nice,’ I said.

There was an interval of five minutes which seemed longer. People were banging on the door of the telephone box.

‘Miss Trumpet doesn’t want anything unless you have something very special she could use in her parade.’

‘They’re all very nice.’

‘In that case Miss Trumpet says to come right away. Don’t bring a lot. And she doesn’t promise to buy.’

There were no taxis outside the station.

‘Don’t you know there’s a war on?’ said the porter, who was trailing after me with a trolley piled high with my wicker baskets. ‘Like Gol-dust. You need a Barrow Man.’

‘Barrow Man?’

‘Chap with a barrow to push your stuff up to Throttle and Fumble.’

‘How far is it?’

‘Couple of mile.’

At this moment, a man appeared, pushing a barrow. He was a shifty-looking little man with watery eyes.

‘Throttle and Fumble. Cost you a couple of quid.’

It seemed a lot of money.

‘Carry ’em yourself,’ said the little man, ‘it’s all the same to me.’

The immense load was transferred to the barrow. I rewarded the porter, I thought handsomely.

‘What’s this?’ he screamed. Other travellers waiting for the taxis that were now beginning to appear turned at the noise.

‘Five shillings.’

‘Five—shillings! What do you think I am a—coolie?’

‘I think you’re a—robber,’ I said with a sudden resurgence of spirit.

‘I’ll take a quid in advance,’ said the Barrow Man, who was listening to this exchange with interest.

I thought of hurrying on to Throttle and Fumble to announce my arrival, but terrible stories of lost collections, recounted by my parents, made me stay with the Barrow Man. At first I walked on the pavement a few paces behind him but this seemed rather snobbish so I descended into the gutter and marched a few yards ahead with my umbrella up. It was like a procession.

‘Throttle and Fumble,’ said the Barrow Man after an interminable journey.

The store was housed in an Edwardian building shaped like a hunk of cheese. It was difficult to see how human beings could be accommodated in the thin end of it at all. We came to a slithering halt outside one of the principal entrances at which a commissionaire in an absurdly pretentious royal blue uniform stood guard.

‘You can’t stop here. Round the back for travellers,’ he said. Then he looked at me again and said, ‘Oh, blimey!’

‘Frognall,’ I said, ‘what the devil are you doing here? And in that rig-out?’

Frognall had been one of our less-attractive acquisitions in the Middle East. He was a boastful, drunken fellow who enjoyed dropping dark hints to his girl friends about the nature of the operations on which we were employed. In Alexandria, far from war’s alarum, unless watched closely he went about armed to the teeth with fighting knives and a .45 Colt Automatic.

For security reasons our unit did not possess a badge; each man wore the badge of the regiment from which he had been seconded. Frognall invented one, a tasteful design of crossed tommy-guns over a submarine, wreathed with the names of places on the enemy coastline which had been visited by members of our organisation in the course of their work. He had it embroidered in the bazaar. Frognall had left us in 1942; the last I had heard of him was that he had deserted.

‘More to the point, what’re you doing?’ Frognall said belligerently, there had been little love lost between us. ‘Come down a bit, haven’t you?’

‘I’m selling clothes, Frognall. But what are you doing with all those medals.’ He was wearing the ribbons of the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the Military Medal and Bar, and the Croix de Guerre with Palm.

‘Gottem in ther Resistance.’

‘You had to work fast to do that.’

‘I’m Sarn-Major Bodkin now,’ said Frognall defiantly, ‘at Throttle and Fumble.’

‘Well, when I’m back in London I’ll remember you to the Commanding Officer. He’ll be glad to know that you’ve done so well.’

‘I shouldn’t do that,’ said Frognall, ‘towards the end I wasn’t on very good terms with the C.O.’

‘All right, Frognall, we’ll see. But just at this moment there’s a nice bit of work here, carrying these baskets upstairs.’

Speciality Model Gowns were on the third floor. The lift was too small to accommodate us. We puffed up the stairs with the first basket, butting the shoppers with it, through the restaurant where the customers were gorging themselves on bilious-looking cakes, through the Dream Girl Room and into the Department.

At first I thought that it was being demolished. The showroom was full of workmen sawing wood and hammering away at something that looked like a packing case for an obelisk. One wall was stacked with little gold chairs.

‘STOP!’ said a great voice.

It came from a woman more than six feet high with hair dyed bright orange. I had never seen anything like her in the whole of my life. She was like a Valkyrie. The remains of such women are occasionally discovered, together with their consorts, decked with amber beads, stretched out in the bottoms of Viking burial ships.

‘STOP!’ she said again, even louder. ‘Where do you think you’re going with that basket. SERGEANT-MAJOR, PUT IT DOWN!’

We let it fall in terror.

‘Good morning,’ I said, ‘Miss Flagstone?’

‘I am not Miss Flagstone. I am Miss Trumpet, the Buyer. Who are you?’

‘I’m Newby of Lane and Newby of Flagstone … I mean London.’

‘I know nothing of you. I never see travellers in the Department.’

‘Miss Flagstone …’

‘She had no right to tell you to come here. Can’t you see that we’re having a Fashion Parade? The Compère’s arriving at any moment.’

‘I thought you might like to see something on a hanger.’

At this moment a sound like someone keening over the dead rose from a little cubicle and a downtrodden little woman in a scurfy black twin-set came racing on to the floor, wringing her hands.

‘Miss Trumpet! Oh, Miss Trumpet! He can’t come! He’s broken something!’

‘Who can’t come? Pull yourself together, Flagstone.’

‘The Compère, Miss Trumpet. He slipped on a marble staircase leaving the B.B.C. He’s in the Middlesex Hospital. They’ve just telephoned.’

Miss Trumpet had not battled her way to the buyership of Speciality Model Gowns for nothing. The qualities that had got her there now stood her in good stead.

‘I will not have a Commère,’ she said firmly. ‘We must have a man.’

‘Young Mr Fumble?’

‘Young Mr Fumble is not fit for anything after lunch, as you should know, Flagstone.’ Miss Trumpet’s eyes were boring into me.

‘You’ve got a fine, deep voice,’ she said. ‘If you’ll do it I’ll show some of your models.’

At three o’clock the Parade began. Great changes had taken place since the morning. The platform was tastefully draped and banked with fern and chrysanthemum. In the background a three-piece orchestra from the tea lounge scraped away industriously. Three hundred chairs groaned as three hundred women leant back to enjoy something for nothing.

‘And this,’ said Miss Trumpet, towering over the microphone, ‘is Mortimer Fell of the B.B.C., who has come specially from London to compère our show … Over to you, Mortimer,’ she ended, roguishly.

I picked up the script. ‘The theme is “Back to Normal”,’ I said. All through what would normally have been the lunch hour I had rehearsed it. During this time Miss Trumpet had displayed the gentler side of her nature. I soon came to the conclusion that being cosseted by Miss Trumpet was an even more macabre experience than meeting her in the normal way of commerce with, as it were, the gloves off.

Almost at once the first model girl came prancing on. ‘Number One, FROU-FROU,’ I continued, looking down from my eminence on the platform on to the bald head of young Mr Fumble, asleep in the front row. ‘A neat little number, isn’t it? Suitable for COCKTAIL WEAR OR GOING ON SOMEWHERE AFTERWARDS. (What the devil did this mean?) Notice the detachable halter and CLEVER BEADING.’

FROU-FROU was followed by a terrifying looking woman of ample proportions with blue hair. A vintage version of Bertha. ‘Number Two, Mrs Whistle shows TWO CIGARETTES IN THE DARK, a gown suitable for the woman who is a teeny bit larger.’ (I recognised one of our own productions here.) And so on to Number Seventy. Number Seventy was the Wedding Group. This had been carefully rehearsed. The string orchestra was to break into Mendelssohn and rose petals were to be scattered. It was to be the climax of the afternoon at Throttle and Fumble.

Number Sixty-Nine, SOIXANTE-NEUF, went loping off. ‘Number Seventy,’ I said, ‘GREAT DAY.’ The band plunged into the Wedding March; but the Wedding Group failed to appear.

I tried again. ‘Number Seventy, GREAT DAY.’ Nothing happened. The audience began to twitter. From behind the curtains came a gentle mooing sound. There was still one more line of script. I read it.

‘… And that brings us to the end. Throttle and Fumble hope you have enjoyed seeing these lovely things as much as they have enjoyed showing them.’

And young Mr Fumble still slept on.

‘Miss Trumpet has gone home,’ said Miss Flagstone, much later, as we sat together drinking tea among the ruins. ‘She was most upset about the Wedding Group. She’s not coming again this week.’

I asked her what had happened to it.

‘Never you mind,’ she said, darkly.

‘Did Miss Trumpet say anything about keeping any of the dresses?’

‘No.’

‘But they’re all covered with lipstick and the velvet one’s split up the back.’

‘Ah,’ said Miss Flagstone, ‘That Mrs Whistle, I always said she was a slut.’

Next day I sent a frantic telegram to the Adjutant in Ayrshire asking to be posted abroad.

CHAPTER THREE Life with Father and Mother (#ulink_72780cd0-21a9-551e-863a-a2ffc268e0fd)

Lane and Newby Limited, the family business of which my father was the patriarchal head and my mother a director was a commercial venture of a sort that is now extinct. By the time I visited Throttle and Fumble on its behalf in that first damp Autumn after the war nothing quite like it existed in the western world. Perhaps on the peripheries, in the coastal towns of Asia Minor and the Levant, a blurred pastiche of it might still be found in those agencies with British names managed by Armenians wearing grey flannel suits and club ties. In England it was probably unique.

It was unique because it was one of the first establishments of its kind – and now it was the last. In the nineties, when my father had gone into partnership with Mr Lane, their joint venture had been a novel one. At that time the idea of expensive women’s clothes being ready-made was almost unheard of. That a store buyer could be persuaded to visit premises situated in the West End of London, far from the vast, wedge-shaped warehouses that hemmed in St Paul’s Cathedral seemed a remote possibility. Nevertheless they prospered.

In 1945 Lane and Newby, by then shorn of much of its prosperity, occupied a house with an elegant eighteenth-century façade in Great Marlborough Street. The Partners had moved there in the Twenties when Regent Street had been demolished to make way for the buildings that make it such a dreary, open ditch and which are now being dwarfed by even more outrageous structures. When they bought the lease Great Marlborough Street housed solicitors and firms that sold sheet music. It had not yet become the epicentre of that spectacular convulsion, the wholesale fashion industry, a dwarf counterpart of Seventh Avenue.

Mr Lane, the senior partner, was no more. The dissolution of the partnership and his departure from the firm had been preceded by an orgy of litigation from which the Newby faction had emerged in a state of near-financial collapse.

I remember seeing Mr Lane on one occasion only; when, as a small boy, I had been on my way to Wimpole Street to have a gumboil lanced. With his great beard he had looked to me like Moses.

There the resemblance ended. For Mr Lane was a man of uncertain tastes. His exploits were always referred to in hushed whispers. In my presence words descriptive of practices of which, at the age of seven, I had not the slightest inkling, were spelled out laboriously by my parents in order to render them doubly unintelligible.

As the years passed my father and Mr Lane became very distant indeed. Both were sportsmen – but of a different kind. My father took his exercise in the open air.

My father was obsessed by rowing. When he was forty-five he married one of his model girls, who was twenty-five years his junior, not an unusual thing to do in the business in which he was engaged; but instead of allowing her to gain the upper hand and run to fat, as is customary, he taught her to row and reconstructed her into one of the most stylish oarswomen on the River Thames.

The best man, who was subsequently to become my Godfather, viewed the impending marriage with misgiving. He was himself a dedicated rowing machine who had won the Diamond Sculls at Henley and the Olympics at Stockholm. He and my father were owners of a double-sculling racing shell which, when they were properly bedded into it, was one of the fastest things on the river between Putney and Mortlake.

It was not the union itself the best man objected to. He himself had married the previous year, probably because he felt that a rowing man, like an ocean-going submarine, needed the equivalent of a depot ship to return to. It was the implied threat to their partnership in the double-sculler that worried him. His fears were groundless.

The wedding reception was held at Pagani’s, a now long-defunct restaurant whose knives and forks survived until recently in a public house in Great Portland Street, W.1, still the great throbbing heart of the dress trade. Only a few guests were invited. My father lacked the necessary courage to inform Mr Lane that he was depriving the business of its best model girl; and in retrospect the wedding day can be regarded as the beginning of what modern historians refer to as A Time of Troubles. As nothing else could, the ceremony underlined the disparity of interest that separated Mr Lane from my father.

As soon as the cake was cut, my Godfather suggested a workout in the double-sculler.

‘The train isn’t for hours yet,’ he remarked. The honeymoon was to be spent at the Lotti in Paris, where the senior partner thought my father was going in order to buy models from the Autumn collections.

‘There’s plenty of time to get down to Hammersmith. It’s just coming on to high water.’

‘We can take a cab,’ he added, improvising recklessly to suit the occasion. And they did. ‘We had a jolly good blow,’ was how my father described it when he returned to his bachelor chambers at Queen’s Club, long after the departure of the boat train, to find his bride in tears, supported by her best friend, who had herself made the mistake of marrying the best man and could offer little but cold comfort.

In the following ten years my mother devoted herself to raising me; enjoying herself with my father after office hours and getting on with her rowing. She had abundant opportunity to get on with her rowing.

In the evenings on week days in the Summer, when he was not travelling with the Autumn collection, my father used to row in eights; on Sunday mornings he used to scull ten miles. This Sunday morning ritual was a great trial to everyone as he used to return to the house, which he had taken at Hammersmith so as to be near the river, at half past two in the afternoon, roaring for hot roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. Because of the timing we rarely had servants; even in the Twenties only the most feudal-minded domestics would wait until mid-afternoon to serve lunch.

This unseasonable food despatched, he used to order his motor, a modest open Citroen (he had a great dislike for ostentation) to be brought round to the door where the chauffeur loaded it with baskets containing ‘the tea’. Then, together with my mother, who by this time was in a state of nervous prostration, we would set off for Richmond.

Even this short journey of five miles or so was memorable. My father was a back-seat driver in excelsis; at the slightest real or imaginary provocation he used to stand up in the open machine and deliver broadsides of vituperation at any other road user who endeavoured either to pass him or, if a pedestrian, simply to cross the road.

He himself had driven only on one memorable occasion. On that afternoon, returning from what he always referred to in retrospect as ‘my trial spin’ he had placed his foot inadvertently on the accelerator instead of the brake when about to enter the garage and had destroyed the façade.

In the Twenties Richmond still preserved some of the idyllic atmosphere of an earlier, more leisured age, and on a warm summer afternoon the Thames flowing quietly at the foot of the hill had something of the quality of a painting by Claude Lorraine, an illusion that was heightened by the misty blueness of the shadows among the trees and the grotto-like entrances to the boathouses of the mansions whose gardens ran down to the river, which were overgrown with vegetation, dim, mysterious and cool.

My father’s private boat was exactly what you would have expected him to own if he hadn’t been in the wholesale business. It was a really big double-sculling skiff built of mahogany and beautifully maintained. In 1926, when I first remember it, it was already fifty years old and I was still using it in 1959 when an unusually oafish, so-called waterman broke its back putting it in the water; by which time it was over eighty years old. Now for the first time in memory our family is without a river boat.

It had fixed rowlocks and fixed seats, each with a perforated felt pad for the scullers to sit on. The sculls were the original set made when the boat was built and were the most perfect I have ever handled. The craft was equipped with a boathook, what is called in river parlance a hitcher – actually a paddle-cum-hitcher with a long handle, which was very useful for getting in and out of locks – and a mast and a sail which was never used. The only times we used the mast were on the rare occasions when we towed the boat, which my father and I sometimes did, employing a sort of double harness of webbing. But even in the Twenties the towing path along the bank of the river had ceased to be used for its proper function; horses were no longer employed to tow barges, vegetation had sprung up and our efforts at towing usually ended in our becoming caught up in a blackberry bush. Why we should want to tow the boat at all was never clear to me. My father said it made a change and my mother, who used to steer, took the blame when anything went wrong.

The internal appointments were sumptuous. Up in the bows there was a long, fitted cushion of dark-blue plush with buttons on it, on which one could lounge at full length. The seat on which my mother sat while steering had a plaited cane back like the body of an Hispano-Suiza motor car; aft there was another long cushion. The carpets were of fine quality and matched the cushions. The boat was varnished and was the colour of fine old furniture. It was lined out with real gold leaf and beneath the rowlocks inboard there were black and gold transfers of sphinxes’ heads. On the bow were my father’s initials. Everything had its place; the picnic baskets were specially made to fit the boat and there were mahogany table tops that fitted across the gunwales, with holes in them for plates and glasses so that the contents would not spill ‘in a heavy sea’. If any china got broken replacements had to be specially made – a process that took months, even years, as the holes were of an unusual size. There were hidden lockers and drawers for such things as loose change and tickets for going through locks; there was even a wicker holster affair, similar to the things mounted policemen keep their truncheons in, intended to hold a parasol – my mother kept an umbrella in it. Altogether the skiff could hold five people comfortably for an afternoon. It was also a camping boat. Iron hoops fitted into brass sockets in the thwarts to form a skeleton frame over which fitted a green tarpaulin cover. By day this cover was brailed up, but at night or during bad weather it could be let down to form a tent over the whole boat. This produced a sort of half-light which turned the occupants a curious shade of green. The same kind of cover is still fitted to punts on the Thames. In spite of their colour, or perhaps because of it, punt covers have the property of making young Englishmen amorous which, under normal circumstances they seldom are, except in liquor at three o’clock in the morning.

Our clothes matched our craft. My father wore white flannel trousers with a narrow black stripe, turned up to show his black-and-pink club socks. He wore white buckskin shoes and he had a magnificent blazer of cream flannel with five buttons up the front. None of the clothes made by his tailor ever wore out. They belonged to a period before the First World War when a button once put on was on for ever. My mother always contrived to be extremely elegantly turned out and at the same time workmanlike as she needed to be.

Normally the least sensitive of men to what others wore, my father was extremely put out if anyone turned up for an afternoon on the water in what he described as ‘the wrong sort of clobber’. There was an occasion when a detective from Scotland Yard was invited to accompany us. My father had an extraordinarily wide acquaintance and I think he hoped that the presence of a real live detective would please me. For days before I was consumed with excitement, but when he finally appeared, in scorching weather, the detective wore a black suit, black boots and, when he took off his jacket and waistcoat, displayed a thick flannel shirt and rather grubby braces. He lent an air of gloom to an otherwise happy outing. From that time onwards my father always referred to him in the past tense as ‘that fellow who wore braces’.

At Messum’s boathouse, when we finally arrived at Richmond, there was always a tremendous palaver about putting the skiff in the water. An experienced boatman would be in charge of the operation and apprentices were routed out of the dark recesses of the building to help with the launching. The wicker baskets were stowed away; there was a great business of putting on and taking off sweaters; at the last moment the leathers of the sculls would have to be greased. Finally we were away, my mother steering, I in the bows trailing my hand in the water and being told to ‘sit her up’ by my father, who was sculling strongly, ‘to get her up a bit’ as he put it. He was shoving her through the green water – for at that time Thames water was not the barely diluted sewage it is today – past Glover’s Island, that beautiful little island with the noble trees growing on it that makes the view from Richmond Hill; Eel Pie Island; Pope’s Villa at Twickenham, and Strawberry Hill where Horace Walpole lived; until somewhere by the sluices at Teddington Lock, where the Thames ceases to be tidal, we would have our picnic tea.

In those days our skiff was not an anachronism. There were friends of my father whose private boathouses held at least a dinghy, and sometimes a punt and skiff as well, friends whom he used to salute and before whom I made my best efforts with the one scull I was allowed to use as a mighty oar. The only interlopers were what my father used to call ‘trippers’, who came down on the bus from London and hired a boat for an hour or so. They were usually to be found in midstream and, if they were in a punt, happily paddling from both ends in opposite directions, trying to tear the thing apart.

It was not so much the social implications of their performance that upset my father, although the idea of a punt being propelled by anything other than a pole must have been repugnant to him, it was the menace to his property.

‘AHEAD SCULLER!’ he used to roar at some otherwise innocuous artisan who was intent on ramming him. ‘SILLY KITE!’ he would shout, shoving the interloper off with his hitcher. To which the answer was invariably, ‘Sorry Guv!’

But as the years passed, taxation and death duties played havoc with my father’s friends. Their incomes were much reduced and they shut down their riverside houses. And worse than all this was the development of The Engine. It became possible to hire motor boats. The occupants of hired motor boats were not people who knew their place as far as the river was concerned, but aggressive young men anxious to show off in front of their girls. Cries of ‘AHEAD MOTOR BOAT!’ meant nothing to them. Once one of them rammed us. There were no cries of ‘Sorry Guv’, only a loud blowing of raspberries and the need to re-varnish the boat. On one occasion my father impaled one of these opponents with his hitchercum-paddle and only his rage and undoubted physical strength saved us all from a ducking. But it was not until someone laughed at him and shouted ‘By Gad, Sir!’ in parody of some retired Colonel, that he decided to seek shelter higher up the river.

Once a year we used to have a week’s camping on the river between Windsor and Henley. It was a complicated and awesome operation. For weeks beforehand equipment considered necessary to our comfort was assembled in a spare room: travelling rugs smelling of moth balls, hurricane lanterns, shovels for digging holes in fields and, at the last moment, veal and ham pies with designs of thistles and acorns worked in the crust, cold Scotch ribs of beef, tins of fruit salad, bottles of hock, glasses of tongue.

We used to arrange to be towed upstream as far as Staines. It was always a mystery to me that my father, who had such an abiding sense of propriety so far as the river was concerned, could risk his vessel in such a hair-brained way, but he did; and no accident ever befell us.

On the day of the tow we used to hang about in mid-stream (just like the trippers) waiting for the steamer to come up from Richmond Bridge. As she surged past bells rang, hundreds of eyes gazed down on us and my father threw a specially prepared line to someone hanging over the stern. There was a tremendous jerk and we would be off, with the bow high out of the water, the skiff yawing horribly until my mother got the hang of the steering. The locks were a nightmare. It was my job to fend the steamer off and stop her from squashing us against the slimy, green walls.

All sorts of ludicrous adventures befell us on these holidays. My father was seldom good-tempered since he was either averting disasters or participating in them: like the time at a delightful, Arcadian place called Aston Ferry, when he discovered that we were moored near a wasp’s nest and insisted on smearing the bottom of a frying pan with jam to ‘attract the beggars’. We soon found ourselves rowing for our lives in mid-stream, having abandoned our equipment, as heavily engaged as a convoy in the Coral Sea. It was difficult to feel sorry for my father when he was stung on the nose.

Generally it rained. The rain in the Thames Valley is like the tropical downpour in some fever-ridden jungle, but more intense. And there were swans, made friendly by my mother, who used to give them sardine sandwiches. My father would mistake their intentions.

‘Strong enough to pull you under, those beggars,’ he would observe, lunging at them with the hitcher; dismayed by this unfriendly reception they would raise themselves in the water and hiss ferociously.

In July, 1937, we were on our way downstream, bound for Richmond after Henley Regatta. We arrived very damp at Bray, a village once famous for its vicar, latterly for the Hind Head Hotel, which at that time had one of the finest cellars in England. We had an excellent dinner. My father drank burgundy and my mother drank claret (this was one of the provinces in which he never succeeded in subordinating her tastes to his own).

My father decided that he liked Bray. It was also a very wet night. We never went back to Richmond; the boat was hauled out and put in the boathouse. My father had had enough.

At Bray all went well for a bit; but in the long run affluent members of his own trade, in electric canoes, and the Guards Boat Club at Maidenhead proved too much for him. A knowledge of watermanship is not one of the conditions of membership of the Brigade of Guards. The members of the Boat Club who drifted across my father’s course purveyed a brand of ill-manners that was unequalled in the civilised world and for which he was no match.

‘You don’t find many young fellows interested in skiff work down here,’ he remarked one evening as we were easing the boat in to the landing stage after a particularly disagreeable encounter. ‘I think I’ll move her up next year.’ He meant to Henley, the last stronghold of the rowing man.

It was July 1939. Fifteen years were to elapse before he was able to put his plan into operation.

CHAPTER FOUR Old Mr Newby (#ulink_68ad8dfb-1799-5ba2-b6a4-2a76aedbface)

If I have dealt at what may seem unnecessary length with my father’s addiction to rowing it is because, seeing his life in retrospect, I realise that it meant more to him than any other part of it.

My father was a complex man. With his love of active sport and the pleasure he derived from the good things of life there was coupled a deep, Victorian sense of guilt that he never succeeded in throwing off. It partly sprang from a deep-rooted conviction that no one should enjoy life as much as he did and partly from a feeling that he was not cultivating his garden with the same assiduity as some of his fellows; those now elderly men who before 1914 had fled from the pogroms of Eastern Europe and set themselves up as tailors in the East End of London.

Working sixteen hours a day, knowing only a minimal amount of English, the most forceful of these refugees had succeeded in setting their sons and daughters on the road to a way of life which to them, working in their sweat shops, must have seemed a crazy dream. In the Thirties their children and grandchildren were beginning to reap the harvest which they themselves had sown with toil and tears – the showroom in Margaret Street, the family house in Cricklewood, the weekends at Cliftonville and Hove, the grandchildren down for Westminster and St Paul’s. It was these men who had trodden the muddy streets of Lvov, Kovel and Voronezh often in fear and trembling who laid the foundations on which the British Rag Trade was raised.

My father was on excellent terms with these old men, many of whom he had employed as outside tailors at the time of the Siege of Sidney Street. A lesser man might have permitted himself a slight feeling of jealousy. If he did experience such feelings he never betrayed them. They too, in their own way, were extremely fond of him. Many of them had suffered fearful indignities and for this reason were at times slightly incredulous at his attitude (to someone who has been unsuccessfully sabred by a Cossack a display of tolerance is often equated with feeble-mindedness). Because he was so English and intolerant in many ways it was one of the last things that one might have expected of him. It was a contradiction in his character that he was only half-aware of, but one that gave him considerable pleasure. In a world that was becoming increasingly racially conscious, among the people with whom he did business his name was a by-word, a sort of laisser-passer.

He never, however, lost his inborn ferocity. There was an occasion when he picked up a man who was behaving in an objectionable fashion on his premises and threw him headlong into the street. The victim brought an action against my father for assault and battery. My father was put in the box and cross-examined by his opponent’s lawyer – an extremely didactic individual.

‘Tell the Court what you actually did to my client, Mr Newby.’

‘I ejected him from my premises,’ my father said.

‘Oh, you ejected him did you? Perhaps you would be good enough to give an ocular demonstration of what you actually did to my client?’

‘I did this,’ said my father. He leant forward and gave the lawyer a violent shove in the chest so that he sat down on the floor.

At this there was a great uproar. The lawyer, his client forgotten, rose to his feet himself claiming assault and battery.

‘Well, Mr Smallbones,’ said the Judge looking down from his eminence. ‘You can hardly complain. You asked for an ocular demonstration – and you got it. The whole thing is absurd. The case is dismissed.’

My father was much disturbed by the political state of the country and by the decline in religious observance. He had a deep-rooted regard for the established order of a religion which he never publicly practised. He never entered a church except as a tourist to look at some family vault.

Yet he would spend long periods on Sunday mornings before setting off for the rowing club reading interminable articles to my mother and me on the parlous state of the Church of England. The Observer was not the free-thinking organ that it is today. If it had been, in all probability he would have burned it ritually.

My mother bore these diatribes with fortitude. She had long since cultivated an expression of eager interest which she was able to assume for long periods of time whilst allowing her mind to range on more attractive subjects. He used to try and catch her out by stopping suddenly in the middle of a sentence, but she was equal to this.

‘Why don’t you go on, dear?’ she would say, blandly, sipping her lapsang souchong. My father would look daggers at her and perforce continue.

I was not so clever. As I grew older it became more difficult for me to listen with equanimity to a twenty-minute reading of a leading article by J. L. Garvin on The Decline of Imperial Responsibility with intervals in which my father made plain his own point of view, and as a result our relationship deteriorated.

He had a curious obsession with violence, but it was of an abstract kind. Walking along a beach he would come on a piece of wood made smooth by long immersion in the water. ‘Foo!’ he would say, weighing it in his hand. ‘You could give a wrong ’un a good slosh with that.’

And his house was full of weapons of offence. Life preservers made from cane and lead and pigskin from Swaine and Adeney, shillelaghs from the bogs and odd lengths of lead piping which he had picked up on building sites. ‘This might do,’ he would say and add it to his collection. But there was nothing eerie about this obsession. He was not addicted to canings and flagellation. ‘Silly kite,’ was all he used to say to me when roused, ‘You deserve a thick ear!’ and at the same time delivered it.

So far as his business was concerned my father travelled a good deal – whenever possible in such a manner that he would arrive back in time for his Sunday morning row – after the departure of Mr Lane he usually had my mother in tow. She accompanied him ‘to put the things on’. She also did most of the packing and unpacking. When he went to Paris or Berlin to buy models for copying she helped him to make up his mind. Sometimes they used to set off for a mysterious place called the Hook in order to sell gigantic coats to the Dutch.

They were both assiduous letter writers and to this day I possess what must be an almost unique collection of letter headings from the Grand Hotels of Europe, stretching from Manchester to Budapest. ‘We had a most disagreeable journey, dear,’ my mother wrote, ‘from Liverpool Street to Harwich, where you would have enjoyed seeing the destroyers. The ship was very dirty and draughty and everybody was sick except your father.’ With the letter arrived a box of sweets from Amsterdam that tasted of coffee beans.

They rarely travelled by air. My father had been a pioneer air traveller on Imperial Airways until on one occasion the machine in which he had been travelling had got into an air pocket and fallen vertically a hundred feet before regaining its equilibrium. The shock had been so great that my father’s head had gone clean through the roof and he had found himself in a screaming wind looking straight into the monocled eye of Sir Sefton Brancker, the Director of Civil Aviation, who had suffered a similar indignity. After the forced landing in a field near Romney Marsh, Sir Sefton had stood my father a bottle of champagne, but he had had enough of aeroplanes and his subsequent journeys were made by more conventional means.

My father’s letters were full of information, but declamatory. More like a Times Leader. ‘Be true to yourself,’ he wrote when I was in the Lower Fifth at the age of eight. ‘I hope you are getting on well with your boxing. When we last had a spar together I did not think that you were leading properly with your right.’ This was not at all surprising as I was left-handed and my father had made me change from left to right-handed writing on the grounds that left-handed men, ‘Cack-handers’ as he called them, were not acceptable in the world of commerce. Because of this for three months I wrote inside out and the results could only be deciphered with the aid of a mirror.

A minor obsession was his preoccupation with my respiratory system. ‘You should sniff up a little salt and water each morning in order to clear your passages,’ was an injunction that was never absent from his correspondence with me. For more than thirty years I religiously avoided practising this disagreeable operation but after his death some inward voice impelled me to follow his advice. As a result I contracted sinusitis and I was told by the specialist whom I consulted that this was an outmoded exercise that led to acute inflammation of the nasal cavities.

But however sombre the counsels contained in his letters he always ended them with a little joke or two to cheer me up. He was never at a loss for a little joke. He used to keep them, or rather the bones of them in neat columns on the backs of envelopes, of which he had an inexhaustible supply, which bore the letter heading of the Hotel Lotti in Paris.

This collection was one of his few legacies to me. The envelopes give the beginning of the joke, some of the attendant circumstances but nothing that would make it possible to deduce the joke itself. ‘Three men in a Turkish Bath – One Fat – It’s Pancake Day.’ Even now no one knows what was intended. To future generations they will prove as tantalising as the Rosetta Stone once was.

But not so tantalising as the visiting card which reads: Thos. W. Bowler (and an address at Walton-on-Thames) and on which my father had written in pencil in his neat handwriting ‘Met on train. Originator of the Bowler Hat?’

Another legacy was a set of dumb bells, weights and chest-expanders. At one time in the Nineties my father had been a pupil of Eugene Sandow, the strongest man in the world, who had opened a school of physical culture in the Tottenham Court Road. Sandow really was immensely strong. Eventually, at a time when motor cars were extremely heavy, he destroyed himself by lifting his own motor car out of a ditch into which he had accidentally driven it.

My father’s capabilities at the beginning and end of the course were embalmed in a small, morocco bound volume. Records of Development, Etc., Obtained During Three Months’ Course at Sandow’s Residential School of Physical Culture. Although the units of measurement employed are not recorded, the numerical increases are so impressive that it seems certain that my father must have graduated with honours.

What would he have emerged like if he had been a ‘resident pupil’?

All these instruments were made from a rustless, golden-coloured metal. The dumb bells were so heavy that when I inherited them after his death I found that I was unable to lift them in the manner prescribed by the instruction book. The compression and expansion of the springed instruments was also beyond me. This in spite of having myself been prepared for the business of being an ‘all-rounder’. Long before the age when English boys are subjected to this kind of treatment I was made to have cold baths and taken for what my father described as a ‘jog-trot’ along the towing path from Hammersmith to Putney and back early in the morning when no sane person was about. Sometimes for a change we would punt a football down deserted suburban streets, ‘passing’ to one another. As a result I too acquired a strong constitution but the outcome was not what my father intended. I secretly resolved that I would not be good at games and I have managed to keep this promise ever since.

CHAPTER FIVE Back to Normal (#ulink_8bf46786-4ca5-5e6c-89f9-6b9428961378)

Since no news had been received from the Adjutant about my future employment, within a week after my visit to Throttle and Fumble I was forced, with the utmost reluctance, to report for duty at Great Marlborough Street where, in the phrase that my parents were to employ with varying degrees of optimism in the succeeding months, I was to ‘learn the business’.