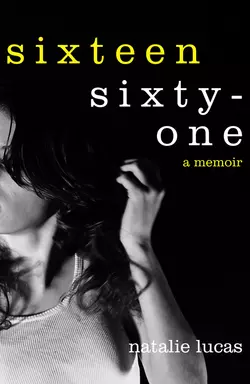

Sixteen, Sixty-One

Natalie Lucas

Sixteen, Sixty-one is the powerful and shocking true story of an illicit intergenerational affair, in the vein of Nikki Gemmell and Lynn Barber.Natalie Lucas was just 16 when she began a close relationship with an older family friend. Matthew opened Natalie’s mind and heart to philosophy, literature and art. Within months they had begun an intense, erotic affair disguised as an innocent intergenerational friendship. They mocked their small town’s busybodies, laughing at plebs like her parents and his in-laws, all of whom were too blinkered to look beyond the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave. They alone danced in the sunshine outside.Or so Nat believed until she decided to try living a normal life.Written with striking candor and a remarkable lack of sentimentally, SIXTEEN, SIXTY-ONE is more than an account of illicit romance; it is the gripping story of a young girl’s sexual awakening and journey into womanhood.

NATALIE LUCAS

Sixteen, Sixty-One

A memoir

authonomy

by HarperCollinsPublishers

For Trish, who saved my life

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ue0243faa-e768-56f6-a9fd-919001ffedd4)

Dedication (#u34943f20-34cd-5d14-b7d2-7493cdfffeb0)

Preface (#ua1b4fdc6-fcfa-5439-9de1-45b63009720a)

Part One (#u0231901b-5e95-57f4-be36-ef66edc65825)

Chapter 1 (#uffa24efc-9c9c-54ea-b825-47a30bfa20a5)

Chapter 2 (#u1eebebc4-92ce-5e32-8bf1-7cdb5f8768eb)

Chapter 3 (#uee778c80-c0f8-5e5f-8e11-9668e0985aac)

Chapter 4 (#u9cbe9117-adaf-58b0-bcfb-bd326a87fc67)

Chapter 5 (#u0de1767f-c129-5144-9697-5287d7690a20)

Chapter 6 (#u30aa2f24-905d-5f45-b78b-01d682904ddd)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Thanking (#litres_trial_promo)

About Authonomy (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter 1 transcript (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter 2 transcript (#litres_trial_promo)

Letter 3 transcript (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_54d93013-e2d4-559d-a41b-017227fcdc34)

14th May 2007

Dear Matthew

Dear Mr Wright

Dear Albert Sumac

Dear Bastard

Dear Ghost,

My therapist keeps asking what I’d say to you if I had the chance. I wonder this myself: what will I say if we bump into each other when I return home this summer? I see your grey eyes coolly inspecting my appearance, noticing I’ve put on weight and look plainer with my hair this length. I imagine you composing an email after the event, though you no longer have my address, so perhaps it’ll be a letter. It will tell me I’ve turned into my mother or that I was cruel to return or that you’re shocked by how evil I’ve become. The worst thing you could write would be that you’re proud of me.

None of this will have been provoked. I see myself still moving on the same strip of pavement, heading for a collision, and I see the moment of horrified surprise that will wash your tanned face of its careful persona, a flash of reality, followed by your collecting yourself, straightening your spine and telling me how nice it is to see me, how was studying abroad?

But I cannot see my own face in this. I cannot form a response, hysterical or otherwise. All I can picture are fantasies of keying your car and smearing pig’s blood on your door, of scratching the letters P-A-E-D-O on your bonnet and hurling bricks through your French windows. Sometimes I scare myself thinking I actually would post a petrol bomb through your letterbox if I could be sure Annabelle was out. And if I wasn’t a wimpy English Literature student with no idea how to make a petrol bomb.

I imagine you now, reading this and laughing. This means you’ve won, doesn’t it? You are still inside me. At sixteen, you filled me with love and that was bad, but now you fill me with hate and this is worse. I hate that you have this power still. Are you flattered? Maybe this is better for you: most people can be loved, there is nothing extraordinary in that. Even the plebs you scorn have their Valentine’s cards and wedding bands. But how many people are utterly despised? How many people are in someone else’s thoughts every day and in their nightmares every night? You should be proud: you’ve achieved some kind of immortality, even if you haven’t written that book you said you would, filmed your screenplay, or established your name.

I hate you by any name.

Sincerely,

Nat

Harriet

Lilith

Natalie

PART ONE (#ulink_8cc477f4-a952-5417-b6ba-211caeb731f5)

1 (#ulink_df476227-a605-5d13-8f27-9b0c8d778f7e)

I was fifteen when my second life began.

It was the summer of 2000. Other things that happened that summer included Julie Fellows allowing Tom Pepper to touch her nipples for the first time, Sam Roberts claiming to have gone all the way with Rose Taylor and her denying it, Wayne Price getting permanently excluded for selling his crushed-up medication on the playground, Mrs Forman resigning her post as head of English amid rumours of an affair with the new science teacher, Pete Sampras winning his thirteenth Grand Slam title at Wimbledon, the leaders of North and South Korea meeting for the first time and the News of the World campaigning for new legislation giving parents the right to know whether a convicted paedophile lived in their area.

Sheltered from such dramas, my first life had been pretty regular. I grew up in a small town in the countryside. I had a mother, a father and a brother. My parents separated when I was eleven, but my mum, my brother and I only moved across town, a few streets away. After we moved, I fell out with my dad for a few years. He began dating twenty-three-year-olds, going to raves and acting like a teenager. I began revising for my SATs, reading books and swapping notes with boys in class. I had my first kiss when I was eleven – with Harry Heeley on the bus back from swimming practice while Kayla Weatherford timed us with her digital watch and Danny King looked out for Mrs Rice walking up the aisle. Shortly after that I started secondary school, where I held hands with Ben Legg, Robbie Burton, Chris Price, Michael Peterson, Stephen Hunt, Simon Shaw, Steven Critchley, David Robson, Gavin Gregs, Reece Cook and a guy at youth club known as Spike.

My favourite item of clothing was a floor-length denim skirt I could hardly walk in. My dark blonde hair reached my shoulder blades in a thick tangle, curtaining my face when I wanted to hide from the world. I’d recently purchased my first pair of tweezers and a box of Jolen personal bleach but had yet to use either, thus noticeable hairs shadowed both my upper lip and between my brows. I was short, not even five foot one – a situation I had tried to rectify a month ago by convincing my dad to spend £16 on five-inch silver platform sandals. I’d worn them with denim pedal-pushers to go shopping and would never again remove the Bowie-esque disasters from beneath my bed.

I considered a day a good one if I managed to avoid embarrassing myself during the seven excruciating hours spent at my mediocre school in the next town. They were few. Most recently, the blonde, bronzed netball captain had seemed to befriend me in order to confirm rumours that I had a crush on Stuart Oxford and, moments after I confided in her, summoned him to tell me – over the sniggers of all around – that he had a girlfriend (a hockey-playing, make-up wearing, French-kissing, Winona Ryder-look-alike girlfriend), but if she and all the other girls in this and every other school coincidentally fell in a vat of beauty-destroying acid, perhaps he’d take me to the cinema. Later that week, I’d also managed to alienate Rachael, the one friend I still had, while we secretly watched her sister’s Sex and the City videos by claiming with confidence that spooning was a kinky form of anal sex and I thought it disgusting. She’d asked her sister to clarify and told me at school the next day that I was full of shit and would probably die a virgin.

While on the topic, though I’d had a few boyfriends and even touched Peter Booth’s thing after we’d been ‘going out’ for six months (but only for a second before feeling utterly repulsed, darting out of the tent to find another cherry-flavoured Hooch and telling him I didn’t want to be his girlfriend any more), I had never handled a condom, still believed you could get pregnant from oral sex and had a poster of Dean Cain dressed as Superman on my wardrobe door that I’d torn out of Shout magazine at the age of twelve.

However, for all my naiveties, I was worldly-wise enough to realise owning up to them was out of the question. I may have known nothing about boys or sex that I hadn’t read in the Barbara Taylor Bradford novels my mum left in the loo, but I had never received less than an A*. I studied long words in the dictionary with the same voracity others my age collected Pokemon cards, I watched the news rather than cartoons and I made it a point to have every adult who met me comment, at least to themselves, ‘She’s so mature for her age.’

Why was I mature? One therapy analysis would conclude it had something to do with being a product of a broken home, my parents splitting up the same year I transferred from primary to secondary school and my devastated mother telling me every nasty thing she could think about my father as we packed our family lives into boxes and moved out of the thirteen-room Georgian detached house that had been a home for the first eleven years of my life. Another would suggest it was down to the amount I read and my stubborn insistence on skipping straight from The Famous Five to Anita Shreve, Margaret Atwood, Pat Barker and Paul Auster, bypassing entirely those Goosebumps and Point Horror years that might shape an average teenager’s development. And another theory entirely would say that, as of yet, I wasn’t any more mature for my age than every other teenager who wants to be grown: that it was what came next that thrust me into an adult world with a child’s mind.

My second life began one Saturday in March when I begrudgingly followed my mum to a tea party at a neighbour’s house. We lived on a row of skinny Edwardian semis on the edge of town, the gardens backing on to a small wood beyond which acres of farmland stretched towards the horizon. The party was at the end of the street. Even my brother James decided this outing required sufficiently little effort to warrant attending, so the three of us plodded the few dozen steps along the pavement to be ushered through to the open-plan kitchen of number twenty-seven.

Once inside, the host Annabelle handed us mugs of tea and directed us through clumps of people to help ourselves from the buffet table. I loaded a plate with sausage rolls and fairy cakes and scuttled to a chair in the corner. When I’d swallowed my first mouthful and was reaching for my sugary tea, a voice spoke from my left.

‘I hate these things.’

I looked over and saw the mildly familiar face of Annabelle’s husband.

‘Isn’t this your party?’ I placed another sausage roll on my tongue and, noting the glass of wine in his hand, wondered if he was drunk.

‘Oh yeah, of course you have to put on a show, keep them all happy.’

‘What d’you mean?’ I asked, only half interested.

‘See over there?’ He pointed. ‘My in-laws. She chairs the WI and he sets the church quiz every Tuesday. If I didn’t throw a party, especially for a “big” birthday like this, I’d be hung, drawn and quartered by the gossipy blue-rinse brigade. Barbara’d come knocking on our door asking Annabelle what’s wrong, was I ill? Were we having marital problems? Annabelle would try to shut her mother up and Barb’d shriek, “What will everyone say?” and we’d end up having a party just to calm her down anyway. Much easier this way.’

I tried to stifle a giggle and almost choked on a large flake of pastry as he put on an old woman’s voice and flailed his arms in prim horror.

‘I’m sure it’s not as bad as all that. How old are you anyway?’

‘How old do you think I am?’ He looked at me with a smile.

‘Oh no, now you’ll get offended.’

‘I promise I won’t.’

‘Hmm, okay. Well, you said it’s a big one, and I’m pretty sure you’re older than my parents, so I guess it must be fifty.’

‘HA!’ His face cracked into a grin and he spilt a little wine on his beige trousers as he chuckled to himself.

‘What?’

‘I think you’re my new best friend.’

‘What, are you older? Fifty-five?’

‘Nope.’ He grinned.

‘Well you can’t be sixty, I don’t believe you’re sixty.’ Sixty was the age of grandparents, that pensionable age where spines curved and walking sticks were suddenly required. The man before me was a little wrinkled and his hair was silver, but his skin was brown, his eyes sparkled and his limbs moved with muscular ease. He certainly betrayed no signs of qualifying for free prescriptions on the NHS. I liked him; he was funny; he couldn’t be sixty.

But he was nodding.

‘Wow.’

‘Yep, I was born in the first half of the last century. It scares me because I don’t feel that old, but I can remember the coronation of Queen Elizabeth.’

I was silent.

‘You don’t even know when that was, do you? Oh dear. 1953. I was eleven. But that’s enough of old-fuddy-duddy talk anyway; let’s speak of youthful things. What rubbish are they teaching you at school these days?’

‘I’m revising for my GCSEs,’ I replied importantly, dismissing his implication that my studies were anything but monumental. ‘And next week I have to pick what subjects to do for A-Level. It’s pretty stressful.’

‘What are you going to take?’

‘Well, at the moment, I think it’ll be Maths, Further Maths, Business and Geography, but I’m not sure.’

He recoiled. ‘Yikes, what would you want to do those for?’

‘What’s wrong with them?’

‘Nothing, they’re just all so dull.’ He faked a long, loud yawn. ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’

‘An actuary … or maybe a lawyer.’

‘Oh dear. Child, you’re going to have a boring life. Have you met the people who go into those professions? They have no gnosis, no emotions, no pulse. They’re just money-grubbing machines.’

‘That’s not true,’ I replied defensively, though I’d no idea what ‘gnosis’ meant. ‘Some of the work’s really interesting. And I like numbers.’

‘But what about the poetry? The passion?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Don’t you do English and Art? Aren’t there any subjects that make you feel excited, spark your creativity?’

‘Well, sure. I love English and I gave up Art in Year 9 but I still like sketching and things. They’re not exactly practical career options, though.’

‘Says who?’

‘Um, my mum, my teachers, the careers adviser.’

‘What do they know? They’re stuck in unfulfilling jobs that sap all creativity. What would the world be like if every artist since Shakespeare had followed the advice of their careers advisers and become lawyers instead?’

I was silent.

‘What they don’t want to tell you is that none of it’s real. Earning money and following the system isn’t real living, it’s just what you have to do in order to find the space to live. The whole thing is an elaborate unreality designed to make us conform. Have you read Nineteen Eighty-Four?’

I shook my head.

‘What about Hermann Hesse?’

‘No.’

‘I tell you what, you say you like English, how about I lend you some books? You can take them away and when you’re done, come and have a pot of tea with me and we’ll talk about this actuary business.’

I took away Steppenwolf and The Outsider that day. Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World, Mrs Dalloway, The Age of Innocence, Brighton Rock, The Plague, The Bell Jar, The Pupil and Sophie’s World followed.

Each time I returned a book, Matthew would carry it down the stairs and place it delicately on the farmhouse table while he boiled the kettle. After nestling the cosy on the pot, he’d offer me a chair and, sitting opposite me, begin: ‘So, what did it make you think?’

‘I don’t know.’ I was shy at first; worried my thoughts wouldn’t be deep enough, worried I would have missed the point of the prose, that I wasn’t reading as I was meant to, that he might think me stupid.

‘Come on, there’s no right or wrong answer. I just want to know how the book affected you.’

Gradually, I allowed myself to answer.

‘It made me wonder why people have to conform.’ (Camus)

‘It made me think one single day can offer more beauty and pain than a whole lifetime.’ (Woolf)

‘It made me question whether a society can condition you to accept anything and, if so, whether there’s any such thing as right or wrong.’ (Huxley)

‘It made me think philosophy is like maths: just logic applied to the world. So, if you think hard enough, there must be an answer, but that religion seems to get in the way.’ (Gaarder)

‘It made me think I should dislike the character, but I didn’t.’ (Hesse)

‘It made me wish I’d been born in that time.’ (Sartre)

And, of course, like every girl my age: ‘It reminded me of me.’ (Plath)

‘Excellent.’ Matthew smiled. ‘Existentialism asks all those questions and comes to the conclusion that the only thing that’s for certain is that we exist; we are here. Nothing else is real. All this crap society puts into our heads: money, work, school, cars, class, status, children, wives – everything we’re supposed to care about – it’s completely unreal. True reality is what’s in our minds. And when you accept that, you realise that conforming to society’s rules just makes you a sheep. You might as well die now. Only a few people have the courage to truly accept this and those are the few that stick their heads above the manhole-cover, who make art and seek out love. I call them Uncles. They’re usually persecuted for it, but at least they’re living.’

‘Why “Uncles”?’ I asked.

He frowned as if I’d missed the point, but shrugged and replied, ‘Because parents are too close, they fuck you up, so it’s down to Uncles, relatives with a little distance, to guide you through life. When I was slightly older than you I found a mentor, I called him Uncle. It was a sign of respect back then, but now I know it means more.’

I considered his words after I left. I watched my mum cooking dinner and wondered if she had ever stuck her head above the manhole-cover. I observed James playing on the PlayStation and decided he hadn’t yet realised the world was unreal. Visiting my dad at the weekend, I looked at him tinkering in the shed and thought perhaps he’d never read Camus.

I sat on my bed and looked out the window.

That is unreal, I thought. Only I am real.

At school, I began to feel I was play-acting in my unreality. It made it easier to deal with the popular girls who told me to pluck my eyebrows, but I found my reality a little lonely. I felt like Matthew was the only person who understood it, so I began visiting him more often. If school and home and youth club and the Post Office were all unreal, Matthew’s kitchen and the pack of cards between us were real.

Annabelle often busied herself in her bedroom, but always asked if I wanted to stay for dinner. The three of us gossiped about the neighbours over shepherd’s pie and sometimes climbed the stairs to watch Friends in their living room. I shared the second sofa with the cat.

One evening, after I’d brushed my teeth and was climbing into bed, my mum knocked on my door.

‘Can I come in?’

‘Of course.’

‘I just wanted to say goodnight.’

She looked uncomfortable.

‘Sweetie, I know you’re spending a lot of time with Matthew and that you’re fond of him. I just want you to be a little careful with him.’

‘What on earth do you mean?’ She didn’t reply and I looked at her in astonishment. ‘That’s ridiculous!’

‘I know, he’s a lovely man and I’m sure he wouldn’t do anything, but I’m a mother and I have to worry. So just promise me you’ll look after yourself.’

I made the promise and muttered angrily to myself as she left about just wanting a father figure because she’d picked such a rotten one in the first place.

When I told Matthew of the conversation the following day, he looked concerned.

‘Your mother’s a nice woman, but she’s steeped in the unreality. She’ll never be an Uncle and she’ll never understand. You may have to be more careful from now on.’

‘What do you mean?’

Instead of answering me, he sent me away with a collection of Oscar Wilde plays, one of which, The Importance of Being Earnest, was indicated with a bookmark.

On page 259 I found a word had been circled in pencil.

ALGERNON: … What you really are is a

. I was quite right in saying you were a Bunburyist. You are one of the most advanced Bunburyists I know.

JACK: What on earth do you mean?

ALGERNON: You have invented a very useful younger brother called Ernest, in order that you may be able to come up to town as often as you like. I have invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury, in order that I may be able to go down into the country whenever I choose. Bunbury is perfectly invaluable. If it wasn’t for Bunbury’s extraordinary bad health, for instance, I wouldn’t be able to dine with you at Willis’s tonight, for I have been really engaged to Aunt Augusta for more than a week.

‘You think I should create my own Mr Bunbury?’ I asked the next time I saw Matthew.

‘Sure,’ he smiled, leading me to his study. ‘Bunburying is an essential part of life.’

‘I’m not sure I want to lie, though.’ I perched instinctively on the navy chaise longue.

‘I know you don’t, because you’re honest and true.’ Matthew sighed and sat heavily beside me. ‘But sadly you’ll have to if you want to live freely. It’s the dreadful irony of life that all Uncles really want is to live pure, innocent lives, but society forces them to play its sordid little games.’

‘So, do you have a Bunbury?’ I turned to face him.

‘I have many Bunburys my dear,’ he answered with a wink. ‘I’ve even had to assume whole other identities.’

After making me promise not to tell anyone, he unlocked a drawer in his desk and showed me the credit cards he had in other names.

Albert Sumac.

Leonard Bloom.

Charles Cain.

‘I mainly just use the first one. It’s been necessary for me to hide certain parts of my life from other parts of my life,’ he paused as he relocked the drawer. ‘For, um, financial reasons as well as personal ones.’

‘You’ve stolen money?’ I hiccupped.

‘You’re very blunt.’ His lips curled into that lazy smile I liked.

‘I don’t think I’ll be shocked.’ I sat up straight, feeling suddenly adult. ‘I’m just curious.’

Matthew returned to the chaise and spoke quietly to the bookcase on his left. ‘I took what I needed from my last employer when I left, yes. My son helped me hide it in the Channel Islands, and later I invested it in property in Kew. It was a one-off thing; now I just do a little tinkering of the books with my racing clients and the housing association where one of my flats is. They pay me – well, Albert – to manage the building and I skim a little off the top. It’s no worse than the banks do every day.’

‘And the personal reasons?’ I whispered excitedly.

‘Ah.’ He turned his wrinkled eyes to me. ‘Well, I’m afraid you might be shocked by those.’

‘I’m not a child!’ I blurted.

‘You’re right, you’re not a child. Okay, well I suppose you’ll find out sometime.’ He glanced quickly towards the closed door before whispering that he and Annabelle had an ‘arrangement’. I listened to his words with wide-eyes, neither daring to ask for details about this ‘arrangement’ nor questioning for one moment whether this might be the sort of line all adulterous men use to justify their actions.

‘You mean you see other women?’ My voice hit an embarrassingly-high note.

‘Shhh!’ He sat back with a grin. ‘I think you’re trying to make me blush today. Yes, I have other women. It’s a necessity of being an Uncle … and a man.’

I mulled over this for a moment, and then asked, ‘How many?’

‘Excuse me?’ He raised one caterpillar eyebrow.

‘Sorry, you don’t have to tell me,’ I mumbled. ‘I’m just curious how many women you’ve “needed”?’

‘In my whole life?’ he chuckled. ‘Annabelle asked me that once and made me count. I think it was sixty-three.’

‘You’re lying!’ I choked. ‘That’s ridiculous. It’s probably impossible.’

‘I wish it was,’ he sighed. ‘Sadly, there have only been a few I really cared about. For some, I can’t even remember their names.’

Over the coming weeks, in between philosophical discussions about art and Uncles and gossipy chats about next-door’s decision to cut down the oak tree, Matthew told me about the women in his life.

‘I used to have to sneak girls past the witch I lodged with. We tried every trick in the book. As far as she knew, I had seven sisters who would each visit me on a different night of the week. Stupid old bag!’

I knew it was weird being told these stories, but I enjoyed them. I imagined them as scenes from black-and-white movies flickering through my mind and tried to work out what my silver-haired friend must have been like as a young man.

‘Sometimes, if I liked a girl, I’d treat her to a hotel room. But in those days they wouldn’t let just anyone into hotels, so you had to pretend to have just got married or, if the manager had a heart, you could make up some sob story about her dad being out to get you but you just being a nice lad after all.’

‘My friend Thomas had this plan to put a mattress in the back of his van, but I think it got him more slaps than shags.’

‘I once kissed three generations of the same family. I was in love with Mrs Shelby when I was six and she gave me a kiss after the school play, then later I dated her daughter Jenny, and when she got too old and grey, I took out her daughter Rose.’

‘Jocelyn was an actress. She never had a penny, but her breasts were magnificent.’

‘Linda was a secretary and used to steal office supplies for me, so I could work from my flat. I hated going into Fleet Street; drinking was the only thing that made it bearable.’

‘Amy was fun; she didn’t mind doing it outside or in the car.’

‘Julie almost killed me. She came to pick me up from work so we could go to the pictures, but what I didn’t know was that she’d found out I was going with her flatmate too. Everything seemed normal and she stayed quiet as I chatted about my day, until she turned onto the motorway and just kept accelerating until we were going 120mph and I was clutching the door handle for dear life.’

‘Kate was beautiful, but she peed herself when she had an orgasm. I could never get into that.’

‘Elizabeth and I used to eat at the best restaurants, and then run out without paying. It put us on such a high. But she always fancied my friend more than me.’

‘Lucy wanted to marry me.’

‘Irene did marry me: trapped me into it by getting pregnant. I was still in Norfolk in those days and you couldn’t run out on a girl in farm country. It was different in the city. I liked the city.’

‘Marie – Annabelle’s friend whom I was seeing before her – was utterly neurotic. The stupid cow used to cry after sex and then insist on cooking me bacon and eggs, even in the middle of the night.’

After hearing these tales, when the teapot was cold or empty and Annabelle was making quiet fumbling noises in the hall – indicating she wanted some attention now – I would stumble onto the street and stare bewilderedly at the pavement I had plodded so many times before. I imagined the seven-year-old me, clad in a gingham dress and kicking stones with sensible shoes, and I wondered how she and I were still in the same place, how I could know so much now, yet still have to pretend to be the same little girl living the same little life in the same little town.

One day Matthew played me a Leonard Cohen album and began speaking in a much more serious tone.

‘Of course, what I was looking for yet was afraid to find all those years was what I had right at the beginning. When I went to university, my family made a big deal about it because I was the first one of us not to work on the farm. I wanted to go to Oxford, of course, but I failed my Latin, so Exeter it was. I was reading English Literature and rushed to join the department paper, to set up a John Donne society and to establish the best way to sneak books past the librarians. I was so innocent then, hardly thinking about girls.

‘Suzanne was in one of my lectures. She was from Paris and wore only black. All the boys were in love with her, but for some reason she came over to speak to me. I bought her a hot chocolate at a café and she took me back to meet her flatmate Marie-Anne.’

I noticed with something approaching panic that a tear had dribbled from Matthew’s eyeball.

‘We had from November to June together and it was perfect. The three of us lived in harmony: Marie-Anne and I both totally in love with Suzanne and loving each other for our mutual predicament. I would watch Suzanne spread out on the bed on spring afternoons, reading poetry aloud as Marie-Anne ran a razor ever so gently over her pubic bone, then softly kissed the raw skin.

‘But that upstart Mickey Robinson decided to publish something in the campus paper about our ménage à trois as he called it. It was the biggest scandal of the term and I was hauled into the Dean’s office. He was so embarrassed he couldn’t even look me in the face when he told me I was being sent down. Suzanne’s parents were informed and she was summoned back to France before any of us could say goodbye. But it was Marie-Anne who took it the worst.’

He was crying fully now and, borrowing a gesture learnt from films rather than life, I walked over to his chair and wrapped my skinny arms over his shoulders.

‘What happened to Marie-Anne?’ I asked softly.

‘She hanged herself in our flat. The landlady found her. I wasn’t even allowed to go to the funeral.’

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Before I learnt about Suzanne and the others, before I’d committed too fully to my second life, Matthew and I had to organise my Bunbury.

‘It’s regrettable, but I think it would be safest if we offered your mother a reason for you to come here so often.’

‘What sort of reason?’

‘Well, perhaps you could work for me. I’ll employ you to sort my books and maybe put my horseracing accounts on the computer. How about that?’

I’d never thought about what Matthew ‘did’. I knew he’d once been a journalist and was vaguely aware he now made money offering betting tips to a mysterious collection of ‘clients’, but generally I imagined he spent his days reading poetry and waiting for my visits. In contrast to my workaholic parents, Matthew’s life was so theoretical and luxurious that the concept of him sat in front of a computer concentrating on paid employment was almost laughable.

‘I really could do with sorting through my books – both the horsing ones, and these,’ he said, brushing his hand over an old edition of To the Lighthouse. ‘I’d like them in order throughout the house. We could do it together and drink cups of tea and discuss the dead poets as we go. As far as your mother’s concerned, you’d just be earning a bit of pocket money helping out a scatterbrained old gambler.’

Thus I began ‘working’ for Matthew. The legitimacy of this work was never clear; sometimes he would thrust a small amount of money into my hand as a kind of payment ‘to show Mummy’, but most of the time I just spent my Saturday and Sunday afternoons reclining on his chaise longue reading scraps of verse from the anthologies we were meant to be alphabetising.

Sometimes I felt a pang of guilt when I returned home and my mum asked me how the afternoon had gone, if we’d got much done. But mostly I rationalised that it wasn’t a lie as such and, anyway, such measures were only necessary because she and everyone else who thought it odd for a teenager to spend so much time with a sexagenarian were so steeped in the dismal unreality of the world they couldn’t see the true beauty of friendship. Besides, Matthew was adept at sensing my angst and, whenever I began to slip too far into the vicinity of guilt and shame, I would find an email waiting in my inbox, pulling me back to the beautiful world of literature and poetry:

From: Matthew Wright

To: Natalie Lucas

Sent: 12 July 2000, 08:27:31

Subject: Your worries

I know you struggle with the lies, but never forget what is real. You feel guilty about your Ma, who herself feels guilty about you and her Ma and all of the world, simply because she’s trying too hard. She can’t see the beauty.

But you, my angel (my Uncle), can. And that is a gift (for me as well as you).

Edmond Rostand said: ‘The dream alone is of interest.’

So, my darling, let us dream.

MW

*

About halfway through the summer, just after my sixteenth birthday, we began discussing love. We read the Romantics, then moved on to Whitman and finally picked up some collections by Leonard Cohen. I liked the singsong neatness of Blake and the hallmark sentiments of Burns, but Matthew would always reach for Leaves of Grass or mumble the lyrics to ‘Death of a Ladies’ Man’.

We discussed unrequited, inexpressible and forbidden love; we talked about communities running people out of town, countries stoning women for infidelity and religions turning their backs on faithful worshippers. We watched The Wicker Man and flicked through the writings of the Marquis de Sade. Wereread extracts from Brave New World and talked about the concept of everyone ‘belonging’ to one another. He told me monogamy was just as abstract an idea as polygamy and we discussed his relationship with Annabelle once more. We talked about the line between friendship and love, about why the world has to be so blind to the possibilities of their overlap. Sometime in late August, Matthew told me he loved me and I wrote in my diary that he was not being improper.

A lingering hug became our ritual goodbye. Back in my bedroom I would miss his arms and want the safe feeling of being enveloped by a true friend. We swapped ‘I love you’s in emails and notes through the letterbox. We knew the others wouldn’t understand, but we also knew that it was true and innocent.

My Bunbury evolved so that once I returned to school to begin the sixth form I had permanent employment archiving Matthew’s racing tips at the weekends. I never went near his computer, but sometimes he’d tell me about reading the form and calculating probabilities so I could blag my way through knowing about gambling. Through a slow accumulation of half-truths and almost-lies, Matthew and I constructed a wall around our friendship that allowed us to spend intense afternoons discussing Uncles, love and poetry. The neighbours, my parents and his in-laws ceased raising their eyebrows and gradually came to expect us to sit together at parties, to dawdle behind or step out ahead on Sunday afternoon walks and to be found together when we were nowhere else.

My diary during that time was a scruffy composition book I’d covered with an angsty painting on squared graph paper. I’d bought it as I walked through the town one Thursday in Year 11 after Josephine Cuthbert had taunted me about my crush on Adam Hound and my brother had poked me in the arm for the duration of our bus ride.

Arriving home, I’d slammed the front door and ran up to my room at the top of my house. I’d spread my paints and brushes over the floor and began making crude, angry marks. After a while, my mum had knocked tentatively at the door. She asked what was wrong and listened sympathetically for a while as I sobbed and tried to describe the hideous impossibility of school and life and myself.

When I paused to hiccup my breath, she glanced towards the window, sighed, and said, ‘Well, I’m sure it will get better. It could be a lot worse – at least you have food on your plate. Dinner will be at seven.’

She left and I grabbed a pen. My first entry looked like this:

21/03/2000

‘Maybe it’s not the school,’ she said. ‘It’s happened before.’ Does she think I don’t know that? Does she think that every day I don’t wish I could fit in, just lazily walk into school and be greeted by a few proper friends instead of worrying who I’m going to burden myself with next?! I hate it. I hate school. I know I’ve never really been able to settle down with good friends, not at primary school either, but I just think that if I reinvent myself one more time then maybe someone will like me. And sixth form is different. If I could just switch schools one more time I shouldn’t get so much of the ‘keen bean’ stuff. It’s only a week until the end of term, thank God. Maybe I’ll make it.

Why the hell am I writing this crap? I hate diaries. They’re pointless and I always write in them for a month or two and then stop. It’ll probably be the way of this one. I just don’t get the point of writing something no one is ever going to read. But then it scares me to rely on memories. I don’t want to forget things, especially not the bad stuff, because that’s what reminds you not to live in the past but the present.

I don’t think I live in either, though. Half the time I seem to be daydreaming: thinking, scheming, planning. And then when I wake up it all hits me again and I get a great wave of depression at the sorry facts of my life.

You probably want to slap me right now. I would. I mean, there are starving kids in Africa and I’m complaining that I have no friends! Not really comparable, I know. My mum says I’m self-indulgent. She cries a lot of the time too, though. I just have issues, you could call it paranoia (is it ‘io’?). I mean, I always find I don’t trust people. Why should I? I don’t trust myself even. I’m two-faced and I lie, so how can I expect all the other girls not to be bitching behind my back? I can’t stand myself. I cringe as I say things and I hate being shy. I hate the way I go red and my eyes fill up with water at the slightest things. I hate biting my nails, I hate how people intimidate me just because they don’t hate themselves. I don’t hate the way I look all the time, but I’m forever wishing I was someone else.

*

By the time Matthew got his hands on my diary, there were many pages of similar complaints about my mother, school, nobody understanding me and the black bags under my eyes. But there were a couple of other things that made me hesitate when he gently asked to read my thoughts.

‘I want to know you inside out.’

‘I know you’re writing it because you want to be read, so why not let me?’

‘It would be the most intimate act imaginable.’

Firstly, of course, I worried because by this time he featured quite extensively. There was probably nothing in there I wouldn’t say to his face given we’d developed such an open form of conversation, but still, what would it be like to have him see things like this in ink:

14/08/00

The only Uncle I have is Matthew, who is four times my age. It scares me because I’ve become quite dependent on him but he’s going to leave me. Be it death or moving to Bournemouth like Annabelle’s always talking about or me going off to university, he’s not always going to be here and that makes me want to weep.

22/08/00

Of course, I wouldn’t go there. Yuk. I can’t believe my mind just came up with that. He’s just my best friend and I’m looking for a father figure. It must be all those French films we’re watching.

29/08/00

I can’t help it. I was in the chemist’s the other day and the woman in front looked ancient. She had a prescription three pages long. I looked over her shoulder and read her date of birth. 1926. She was 74. All I could think was that, when I’m thirty, that’ll be Matthew. He’ll turn seventy the same year I’m twenty-six.

The second thing that I worried would set my diary apart from any other sixteen-year-old’s Matthew happened to read was the confession that had made one of my ex-boyfriends, Todd, exclaim, ‘Oh God, you’re just confused. Every girl I’ve ever met says that. Get over it, you’re not a lesbian!’ I didn’t know if I was a lesbian or not, but after the incident with Todd I stopped admitting seriously to friends that I thought I might like girls. I did, however, scrawl lines and lines about my concerns and ventured tentative explorations behind the mask of alcohol.

22/03/00

I figured out why I’m writing a diary. It’s because I watched Girl, Interrupted (my favourite film, along with American Beauty and The Virgin Suicides) and she writes a diary in that. I guess I thought it might help me figure out some of my feelings. Watching that film again was really scary. It’s about a girl with Borderline Personality Disorder and the scary bit is I could relate to everything she said: all about not fitting in, not being listened to, not being able to just accept life and finding it easier to live in a fantasy land. The only thing I didn’t really relate to was the whole promiscuous thing – still being a virgin and all. But even that’s quite shady because I think that if I had the confidence, I may be promiscuous. I keep thinking about shagging some random girl. I don’t even know how it would work but I look at Jenna and Claire and Becky in class and I just want to press my lips onto theirs. Sometimes I worry they can see my thoughts, so I tell them I was thinking about Juan, this fit new Spanish guy in my tutor group. But, truth is, I’m far more interested in the lesbian thing. I heard some girls in the year below got really drunk last Saturday and all took each other’s tops off and had an orgy. All the girls in the toilets squealed with horror and said to keep away from them in PE in case they perved on us, but I just wanted to ask who they were and how I could make friends. Am I a freak?

*

Matthew had asked me ages ago whether I kept a diary and what security measures I had to prevent my brother and parents from reading it. He’d also asked in a teasing tone what secrets I recorded there and whether I kept secrets from him. For a few weeks I’d been entertaining the idea of letting him see it, of allowing another person to read me. I’d read and reread my own hand, wondering what Matthew might make of it: would he be shocked by my curiosities about my sexuality? Would he laugh at my immaturity? Would he think I was a bad daughter because I wrote angrily about my mother? Would he realise I was a loser with no friends at school and not want to spend time with me any more? Would he be offended by my thoughts about him? Would he still like me?

Eventually these doubts were outweighed by the heavy desire to be known: for a single person in the world to understand all that was in my head and help me work it out. One Sunday, after we’d had tea and chatted about Emily Dickinson, I removed the tatty book from my backpack and, with a trembling hand, offered it to Matthew. I paced miserably home and woke a dozen times in the night wondering if I had an email from him.

The next day, Matthew hung my diary from our doorknob in a plastic Safeway’s bag, along with two other items. The first was a new, spiral-bound, orange-flowered notebook; the second, a palm-sized engraved metal shape that Google later informed me was an ankh, the Egyptian symbol for immortality. My immediate concern, though, was the printed page wrapped around the object:

Extract from The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler

The ordinary mortal in our urban civilisation moves virtually all his life on the Trivial Plane.

You are not ordinary, Natalie.

I saw Matthew a few hours later and all seemed normal, but as he poured me a cup of tea he asked nonchalantly, ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were wondering about such things?’

I looked at him blankly.

‘It’s perfectly natural. In fact, it’s essential for Uncles to be open to love in any possible form. Most people go through their lives too afraid to admit their desires; they lock them up and only let out what their mummies say is okay, then end up in dead-end marriages having sex twice a year and finding their wives have been having an affair with the gardener.’

I giggled at his wild, angry gesticulations.

‘Your friends at school are just threatened by your insight. They probably go home and masturbate over you, wishing they had the guts to follow through.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ I smiled. ‘But is it okay then? Is it normal?’

‘Why on earth would you want to be normal?’ he chided. ‘But of course it’s okay for you, it’s what you feel. It’s exciting.’

There wasn’t a day that innocence turned to deception and friendship to seduction. The declarations of love and the poetry we were reading lent themselves to hypothetical discussions about erotic possibilities, but they began in the abstract.

‘If society is so wrong that it forbids a perfectly healthy friendship between an old man and a young girl,’ I’d ask, ‘how can we be sure that everything else it deems “wrong” isn’t just as natural?’

‘Exactly,’ Matthew would grin. ‘The machine is there to perpetuate itself, not to protect us. You must find your own rules.’

‘But it’s absurd that a society it doesn’t affect in the slightest condemns it so forcefully. What difference does it make to Mrs Roberts and my mum and Pat down the road whether you’re my best friend and I want to tell you I love you?’

‘None.’

‘And obviously I don’t, but what difference would it make if I wanted that to be romantic love? As long as it made you and me happy and Annabelle was not hurt by it, who else could it possibly affect?’

‘No one.’

‘And it makes you wonder what else we’re being conditioned to disapprove of. Why is euthanasia banned? Why is bigamy illegal? Why can’t tribes live as they want? Homosexuals get married? Lesbians adopt? Prostitutes work in the open and couples swing?’

‘Because true freedom is too much for most people. Only Uncles realise the true possibilities of love and life. And sadly it means they must spend their lives fighting against society just to stay alive.’

By mid-September, we’d all but given up on sorting books. Instead, we’d carry a tray of tea and Eccles cakes into his study and close the door. We’d sit sideways on the chaise and I’d snuggle into his arm while cradling a cup in two hands. Being cuddled by Matthew was my favourite thing and I conveniently ignored the occasional slip of his hand or sniff of my hair.

Sometimes, if we were having an impassioned debate about literature or the world, our faces would get close, our eyes locked together in intensity. One day, his argument trailed off and I thought I must have won my point, but his face remained close and my eyes couldn’t turn away. I felt something tingle in my throat and shoulders. I had a sensation like pressing a bruise and became strangely aware of my sandalled toes. Was it my imagination, or was his face inching closer, were his eyelids drooping closed?

I pulled away and straightened my T-shirt.

Matthew reached for his mug and sat back, smiling.

‘You almost let me kiss you then.’

‘No I didn’t!’ I blurted out, then blushed.

Matthew sipped his tea and muttered, ‘Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,’ before replacing his cup and asking what time I’d be able to come tomorrow.

The scene of the almost-kiss was repeated a few days later on the couch in the living room and again over the table in the kitchen. Each time, I allowed myself to indulge that dizzying feeling for a moment longer; smelling his musky cologne and studying his wrinkled lips; tasting and enjoying the unknown before being plunged into the confusing rapids of shame and regret.

I wrote pages in my diary each night, convinced this elastic band of emotions was true passion and I was the only person ever to have felt it so potently. And every second or third weekend, Matthew read my angst-ridden thoughts and told me my soul was beautiful, my life would be incredible.

On 28th September, Matthew succeeded. I wrote in my diary it was ‘Nothing huge, but special all the same.’

That evening, he sent me an email:

From: Matthew Wright

To: Natalie Lucas

Sent: 28 September 2000, 22:37:31

Subject: Thank you

Your mind was beautiful today, your body pure bliss. I belong to you.

Ancient Person of thy heart

*

You can probably see where this is going now. It wasn’t quite as clear-cut and sordid as it might appear. Naive as I may have seemed thus far, I realised there were certain lines that required more consideration than others before crossing.

While the kissing gradually led to ‘sorting books’ in a horizontal position in the top room, I was quite insistent that whatever his hands and mouth did to please me, his belt-buckle was not going to budge. And though we sent emails most evenings telling the other of our desire, dreaming of total abandonment from the safety of separate bedrooms and discussing the orgasmic meeting of my ‘baby kitten’ and his ‘throbbing doppelgänger’, I was certain of one thing: I didn’t want him to be my first.

I was aware mine was an unorthodox adolescence. I realised I could grow to regret it, despite my enlightened knowledge that this was the real world. So, for the sake of damage limitation, I wanted to lose my virginity to someone else. Matthew and I discussed the situation via email only, never referring to it between declarations of love in person.

From: Matthew Wright

To: Natalie Lucas

Sent: 4 October 2000, 09:20:12

Subject: Two roads in a wood

I see you worrying about what the world will think and whether you will be able to take things back, whether you’ll regret our friendship in later life or discover you chose the wrong yellow-brick path. I see you struggling to find the answers and I wish I could take your pain away, because this time for me is beautiful and relaxed. As you grow, you will understand the world has its reason and things will happen as they please. Our decisions always seem more significant before we have made them.

So, if in your deliberations you ever worry about me, please don’t. I am a happy voyeur of your beautiful mind and the conclusions I know it will eventually reach. I cannot, of course, give you advice, but perhaps if you have your A* mathematician’s hat on today, you will appreciate the words of Mr Einstein: ‘Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the empirical world; all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it. Propositions arrived at by purely logical means are completely empty of reality.’1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Follow your heart, my love. I will await.

Your very parfait gentle knight

MW

Every night I’d retreat to my room and attack my diary. Matthew told me the decision was in my hands, but our mutual stumbling block was my virginity. He said he couldn’t ‘take the lid off’ that side of me because the first time would inevitably be disappointing and he didn’t want to ruin what we had. I agreed. Everyone said it hurt and I was sure I’d end up hating him. But how could I take the lid off with someone else knowing I was in love with Matthew?

What I needed was a boy my own age who wouldn’t mind being used and whom I trusted enough not to tell the rest of the sixth form about my proposition.

Richard was my target. We had been girlfriend and boyfriend for a short while in Year 10 and had remained flirty friends since. Our ‘relationship’ had ended when Richard had told me, quite seriously, that he had important and dangerous things he had to concentrate on to fulfil his destiny and he couldn’t be distracted by the usual trappings of teenage life. The gossip tree soon filtered to me that Richard had confided in his best friend Andy that he had been approached by an old homeless man while on holiday in Greece who had told him he was the Second Messiah and dark powers were approaching that only he could battle. Ever since, Richard had been bidding for Samurai swords on eBay.

To sum it up, in Richard’s favour:

Single

Too focused to want a girlfriend

Too self-absorbed to bother caring about my motives for such a deed

And, against him:

Possibly slightly unhinged.

I told Matthew I had decided on a person. I suggested the thing to Richard via MSN Messenger. And Richard agreed. The how and where were a little more complicated, so, though it was only October, we decided on New Year’s Eve, knowing somebody would have a party. It was settled. I would pop my cherry as I was meant to: drunk and in someone’s parents’ bed with an acne-ridden boy I found only mildly attractive, and thus I would be free to explore the world of Uncles with one less worry.

Then came the green candle.

On 4th November, I received the lyrics to a Leonard Cohen song via email. The first line was blown up in bigger font and some words made bold:

I lit a thin green candle to make you jealous of me.

Attached was an extract from Matthew’s diary:

November 2000

So, old man, what are you going to do?

About what? And who are you calling old? I thought we were only as young as we feel.

Fool. I suppose you’re telling me she’s the elixir of life?

Natalie? Yes, she might be.

So, what will you do?

I can’t hurry her. Her beauty and charm is in her innocence – she needs to find her own way.

But what about you? What about your needs?

My needs are less important than hers.

Less important, perhaps, but no less pressing. Every man has needs; it’s foolish to deny them.

Yes, yes, we’ve been down this path before. I know I must do something.

So?

Well, Suzie keeps pestering me.

The PhD student who snaps at you if you bring her flowers and doesn’t care if you don’t call? Sounds perfect.

Yes, and she tells me she’s spent the past six months in the gym.

But..

But every time I see her she tells me she wants my child.

Yikes.

Indeed. She says I won’t have to be involved, but I’m not so sure.

You think she’s tricking you?

Not deliberately, but women are irrational, they change their minds, especially when children are involved. I’ve had enough of that for a lifetime.

So, what’s the alternative?

Becky’s eager.

The one with the nice bum?

Yes, you perv, the one with the nice bum. But she’s not much older than Natalie. Eighteen, and nowhere near as mature.

Could be fun, though.

Yes, perhaps.

But..

But my heart’s not in it, I suppose. Even though I know I need something and Natalie’s talking about experimenting with some boy from school..

Wait! You’re talking about living like a monk while she goes around with spotty teenagers? You’re even more of a fool than I thought.

Perhaps. A fool for love?

Pah. It doesn’t seem fair at all.

No, but she’s a child, I can’t expect her to understand. I can’t make demands on her.

And what’s this email about? Are you lighting a green candle?

No, maybe, no. No, I just want her to know how I feel. Perhaps I won’t even send it.

And if you do?

Nothing. Then she’ll know I’ve chosen what I have with her over anything I could have with the others.

How very noble.

Don’t be so sarcastic. I mean it. I love her. It’s real. For the first time in my measly, ancient life, it’s real.

A bubble began to rise in my stomach as I read. Suzie and Becky. Who were they? Why should I care? Matthew said he was not lighting a green candle, but still sent me the lyrics to the song. What could that mean? The basement room where I was reading was lit only by the light of the screen and I imagined myself engulfed by a turquoise flame. I pounded up the stairs to my bedroom and scrabbled beneath my mattress for my diary.

After an hour sprawled on my bed with a biro in my hand and tears in my lashes, I paced back down to the computer, praying my brother hadn’t gone to play his stupid Age of Empires game and read the email I’d left open on the screen. Happily I passed the living-room door and saw James cross-legged in front of the PlayStation instead.

Back at the keyboard, I hesitated. As much as my fingers tingled to reply ‘No, don’t! I’m here and, yes, I’ll be an Uncle,’ my throat longed to scream that this was unfair, that I was being handled and manipulated and an Uncle wouldn’t do such a thing.

My fingers won.

From: Natalie Lucas

To: Matthew Wright

Sent: 4 November 2000, 22:42:03

Subject: RE: One of Us Cannot Be Wrong

The flame is burning moss. I have an in-service training day a week on Wednesday – can we find a Bunbury?

Later, in my room, I doodled in my notebook:

Am I condemned to be

Number sixty-four?

Will you tell your next girl

This one was a bore?

That innocent little kitten

You deflowered so well;

My young naive mind,

To the devil did I sell?

Will you tell of the chase?

The thrill of the game

That finally won me …

To discover I’m too tame?

Not like Suzie,

She was fun.

Not like Becky,

With the ‘nice bum’.

Is it worth it?

Will I disappoint?

Will you regret the effort?

Will I score a point?

2 (#ulink_2f760dd6-f65d-5d64-992f-51fd3c2a8833)

At approximately 3pm on 15th November 2000, in room 107 of The Swan Hotel in Swindon, I lost my virginity. I’d been wearing three-inch heels and an oversized suit-jacket, too much make-up for a teenager and black cotton knickers bought in a pack of five from BHS by my mum. I’d known Matthew had booked a hotel room and I’d lied to my mother about going to the cinema with a friend, but I still padded to the bathroom, self-conscious about my nakedness, and looked in the mirror with surprise. As I peed, I wondered what I had thought usually happened when a sixth-former allowed a sexagenarian to spend £150 on a plush suite that would only be used for an afternoon. Had I thought we would simply continue what we had been doing in his top room? Had I imagined his hands and mouth would always work eagerly to please me without his belt-buckle ever budging? Had I believed we could stay in the no-man’s-land of technically doing nothing wrong? Had I hoped the past few months contained mere digressions that I could take or leave when the mood struck and walk away with my purity intact?

Perhaps I had. It wasn’t as if my bookshelves, teachers or friends could provide a precedent; it wasn’t as if there were any rules. But I’d responded to his green candle, hadn’t I? I wasn’t totally naive: I’d known what he’d wanted. But I hadn’t thought about this while clipping my bra and brushing my teeth this morning. I hadn’t said goodbye to my mum thinking that the next time I saw her I’d be, what, a woman? I’d thought of my Bunbury: I’d concentrated on not overlabouring my lies but making them seem natural. I’d wondered how easy it was going to be to walk nonchalantly towards the bus stop, then dart off onto North Street and slip unobserved into Matthew’s waiting passenger seat. I’d deliberated over whether to hide my heels in my handbag and change into them while crouched in his car, or to risk my mother’s disapproving comments about unsuitable footwear for the cinema and just leave the house in them anyway. But I hadn’t thought about what it would be like to be in a hotel room with Matthew, about his penis actually sliding inside me, about his body on top of mine, about whether it would hurt or whether I might have forgotten my pill even though I hadn’t once since I’d been put on it for period pains in Year 10, about all that advice in sex education classes to use condoms even if you’re taking contraceptives because you’re not protected from STIs that make your pussy resemble an erupting volcano. With the innocence of a teenager who has spent countless Maths classes giggling with friends and ex-best-friends over code-words for body parts and rumours that the girl at the back puts out for the price of a chocolate bar, I hadn’t thought we’d actually do it.

I didn’t bleed and I didn’t cry. I didn’t even see his thing. Matthew approached it technically, disappearing into the bathroom and returning in his shirt and underpants, smelling like talcum powder, before undressing me and laying me on the duvet. Next, he rifled through his briefcase and pulled out a bottle of Johnson’s Baby Oil, placed it neatly on the bedside table. Then, climbing delicately onto the bed, he fixed his eyes on mine.

‘Do you love me?’ His demanding tone surprised me and I nodded meekly, letting only a nervous breath escape my lips.

‘Yes, I can see the love-light in your eyes.’

And in a few minutes it was over. Matthew offered me a box of tissues to clean the stickiness from between my thighs and pulled his trousers back on.

After I returned from the bathroom, we lay on top of the duvet for a while, me naked, him clothed. I wanted to appear mature, but my head was reeling with excitement and disappointment: Was that it? Is thatwhat everyone whispers about in school? Am I different now? Will they be able to tell? Will my mother know? Will I remember this as special? Matthew withdrew his arm from around my stomach and walked to the dressing table to fetch his cigars. I pulled my knees up to my chest and hugged myself.

‘What are you doing?’ He turned back in amusement and horror.

‘Nothing. Just thinking.’

‘That’s what women do to get pregnant you know – lie back like that. You’re not trying to trap me, are you?’

‘What? No!’ I blushed and sat up straight, embarrassed that I’d let my ignorance show.

‘I was just thinking about Meursault,’ I said, defaulting to literature as a safe topic where we might speak as equals and forget the mundane realities of his grey hair and my smooth skin.

‘Hmm?’

‘He’s the hero of existentialism, the man who refused to play the game, let alone abide by the rules, and he highlights all that’s wrong with the world – all that makes this an impossible place for poets and Uncles to live in – but do you think he ever experienced love? Isn’t half the point of the novel that he doesn’t feel any passions, doesn’t understand the motivations of those around him or why laws must dictate x and y? He’s basically just an ordinary man: neither an Uncle nor a sheep. He sticks his head above the parapet, but not for any of the reasons that writers and lovers and you and I do.’

‘True. But he’s just a character. The point is that Camus was feeling all those things and rebelling through his creation.’ Matthew sat back against the headboard, a slight smile curling his lips.

‘But Camus didn’t actually challenge the law and expectations; he didn’t kill anyone and face punishment but not even experience it as punishment. For most of his life, he played society’s games and persona’d like the rest of us.’

‘So, you wanted him to martyr himself for a world that wouldn’t care?’

‘No, but it’s just, who should we celebrate? Camus or Meursault? Camus’s creation of Meursault almost serves to highlight how thoroughly trapped he himself was by the bullshit of the world.’

‘Hence why we have to Bunbury,’ he winked at me, exhaling a cloud of smoky air.

‘But, I want to know if any Uncles ever find the ideal, ever manage to live fully. That has to be the ideal, right? Otherwise what’s the point? Why would we continue? We should all wander into rivers with stones in our pockets or stick our heads in ovens. Because a little bit of poetry is not enough. This escape, being here, being with you is my reality and the rest is just gross, you know that? It makes me cry at night. And if I thought it was going to always be like this, I don’t know what I’d do. Sometimes I think I’d rather die on a happy note – that’s when I’d consider suicide, after the most ecstatic moment of my life, because the thought of falling after being so high would be totally unbearable.’

Matthew smiled at me and I knew I’d redeemed myself. We were no longer in a plush hotel room with a Bible in the drawer and a disapproving receptionist downstairs; we didn’t have to leave in a couple of hours and drive back home to face parents and wives, neighbours and peers; instead we were sitting on a cloud with Virginia Woolf and Edgar Allan Poe, sipping tea with Simone de Beauvoir and Marcel Proust. And on this cloud, Matthew’s leathery lips tasted like March daffodils as they pressed to my own. My skin buzzed as he folded me back into his arms, whispering into my neck about Helen of Troy.

We left Swindon around five, me sneaking past reception to the car while Matthew dawdled to tell the concierge he’d received a phone call requesting his immediate return, so alas would not be staying and would not require breakfast in the morning. He drove in silence and as we neared home I ducked my head between my knees in case the passing headlights of a neighbour or relative’s vehicle happened to illuminate our incongruous faces. He dropped me off at the other end of town and I changed back into my Nikes to plod home, past the Post Office, grocer’s and butcher’s, preparing my lies and not-quite-lies in my head.

‘Yes, Mum, Claire and I had a great time.’ Claire most probably enjoyed her day off too and I didn’t say we had a great time together, so we’ll call this true.

‘We went to this cool little café and had cream teas.’ True. It was called the Scribbling Horse and the woman gave us extra cream.

‘The Road to Eldorado is okay, it’s a bit childish, though.’ You don’t have to see the film to know this and, as my mother refuses to watch animations, it seems unlikely I’ll be quizzed about plot and character development. Therefore, true, plus extra points for successful Bunbury.

‘Hastings was really crowded.’ Also most likely true … I just wasn’t there.

‘No, I didn’t buy anything, but we did look in some book shops.’ True. Matthew bought a Collected Letters of Virginia Woolf and I fingered a first edition Oscar Wilde, but shopping wasn’t our main priority.

‘The bus was a little late.’ Okay, this one’s a lie, but unavoidable. Five truths and one lie – not bad.

A few hours later, my mum, my brother and I banged our gate and walked the 300 yards to number fourteen. Lydia answered and led us into the sitting room. Annabelle was already sprawled on the floor with her work-friend Lucy, inspecting hand-made jewellery. Lydia’s sister, Hannah, was fussing over a teapot by the bay window, and their frail but sharp-eyed mother, Valerie, was characteristically bent double beside a bookshelf, hunting for a specific volume of her 1948 edition of The Encyclopaedia Britannica. These were my mother’s friends: people who had been kind to me since I was in single digits; honorary aunts and uncles who cared for my brother and me like children of a collective. Occasionally I felt a pang of guilty tenderness towards this extended family, but mostly over the past few months I’d begun to see them through Matthew’s cruel cynicism, noting their individual quirks and scorning their refusal to stick their heads above the parapet.

‘I’m so glad you could come on short notice,’ Hannah gushed in over-the-top hostess mode. ‘Lucy’s showing us her gems. Isn’t she good? I’m thinking of taking a course.’

My mum had said we’d been invited to look at jewellery; a kind of Tupperware party with beads I supposed. I’d fancied a cup of tea and James had been bribed with biscuits. I shuffled into the room after my brother and noticed Matthew on the end of the couch, a book in his lap. He made eye contact and I turned away, willing my cheeks not to burn.

My eyes landed on Annabelle’s patterned skirt. She’d coupled it with an embroidered shirt and looked sumptuously hippyish. In contrast, Hannah wore tight black jeans, ankle-boots and an oversized jumper that made less than subtle allusions to the 1980s, a period in fashion that had not yet returned to the likes of Topshop and H&M.

Lucy, a tiny blonde woman swathed in coloured silk, was explaining how she chose each bead. Something about the karmic energy, I think. I watched her mouth as she talked for a while, but quickly turned my attention to her husband, Graham, who wore ripped jeans and sat with an air of boredom on the sofa next to Matthew. He and Lucy had a son two years above me at school, but Graham looked a bit like a floppy-haired George Clooney so I figured it wasn’t too bad to have a crush on him. I sat on the floor next to his feet and asked him about his motorbike, giggling when he said I should come for a ride one day.

‘If your mum says it’s all right, that is.’

I flushed with excitement and tried not to notice how old Matthew looked beside Graham, how his leg rested effeminately upon his knee and his shirt fell over a muscle-less torso. It wasn’t that I didn’t love him or that I didn’t want to repeat what we’d done this afternoon, but something had changed today and I felt a new kind of energy coursing through my limbs, one that drew me instinctively towards the Grahams and Lucys of the world.

I wasn’t the only one, though, and before the evening was over, Hannah was sat tipsily in Graham’s lap and Annabelle was fawning over Lucy’s earrings, brushing the skin on her neck as she fingered the green gems dangling from her lobes. My mum and Valerie were deep in discussion about the treatment of mental health patients in 1975 and James’s head rested heavily on his arm as Lydia spoke of the difficulties of getting out to do the gardening. On the way home, James growled at my mum that he’d never be forced to go to one of those things again and she muttered a reply along the lines of, ‘I don’t know why you have to be so antisocial; Nat seemed to enjoy herself.’

3 (#ulink_a4b1e0a1-f687-51f4-955e-fb64d0fbda1f)

On dreary country days, when the air choked with the pitiful mediocrity of small town life, old ladies wheeled their trolleys through town to collect their pensions from Nicky at the Post Office and Ray listened to people natter about haemorrhoids in the chemist before dispensing Preparation H, I would sit in Matthew and Annabelle’s open-plan kitchen, playing cards and drinking tea from a pot. Sometimes I’d curl my legs under me on the awkward unpadded chairs while Annabelle doodled flowers beside the crossword in the Telegraph and Matthew consulted The Racing Post. He sat at the head, with the two of us on either side; these were unarticulated but set places and it was always odd when Annabelle was away and Matthew set my place for dinner at her chair.

During term time, I spent six out of seven nights there and, on holidays, most days too. Eight front doors and eleven cars separated their house from my mum’s. The Grays, the Smiths, the Popels, Mrs Pratt, Mr Davis, Oliver and June, Beatrice and the Roberts lived in between. Our immediate neighbours, the Grays, had retired to tend their immaculate garden and always said hello when I passed them on the pavement, but would become more reserved in a few months once I moved in with my dad and my mum began muttering up and down the street about my being an ‘awkward teenager’. Mrs Pratt had been a teacher at my primary school and, although she asked kindly about my exams and future plans, I was still a little afraid of her and mumbled nervously whenever I encountered her on my way to the house on the end.

Matthew’s study lay behind the street-side window, so I could always tell before I arrived whether he or Annabelle would answer my knock first. Their post-box-red front door encased in its black frame now looms overly significant in my memory. Stepping through that doorway I would shed the unhappy teenager living in a deadly dull town that haunted me on the outside and enter the safe place of art, poetry, philosophy and love.

A kingfisher I had drawn in pastels at the age of eight hung above their stove, the Piglet I had won Matthew at the fair was pinned to the whiteboard in his study, my cribbage board had found a permanent home on the shelf with his chess set, and Juno, Annabelle’s cat, paid no attention to my comings and goings. Towards the end, I might even have had a key, and, of course, volumes of my angsty diaries lay in a locked drawer of Matthew’s bureau because we’d agreed early on that this was safer than having them only perfunctorily hidden beneath my mattress.

The three of us played cards, drank wine and sometimes smoked weed acquired from my friends at school. Matthew and I would touch feet under the table and sneak a kiss when Annabelle ran upstairs to fetch something. Sometime after 10pm Annabelle would pour herself a tiny glass of port and wish us goodnight. I would stay, wrapped in Matthew’s arms as we whispered secrets to each other or dared ourselves to forget Annabelle was only upstairs, until it got late enough that I worried a parent might come looking for me and I let myself out, arrived home and calmly watched some television repeat with my unquestioning family.

My first memories of Matthew and Annabelle hardly involve Matthew at all. Annabelle and my mum were introduced through Ruth, a woman who had had her first marriage annulled and convinced a Methodist priest, despite her four grown children, to perform her second attempt to a childhood friend. When my parents were ending their messy though marriageless relationship, Ruth was the witch who stole my mother from me when she cried, but Annabelle was the angel who gently entertained my brother and me; she turned packing up our family home into a game of make-believe pirates and princesses.

Annabelle’s husband was just one of those shadowy figures of husbands you remember from playing in the garden while your mother gossiped with her friends on the patio, drinking cups of instant coffee. He must have been in the background and I must have known him, but the squiggly jigsaw pieces of his identity in my mind didn’t slot together until our conversation at his birthday party. From that moment, though, it was like someone flicked a switch and swapped the direction of the escalators in a department store. As Matthew became a fleshy figure, a father, mentor, Uncle and lover, and I spent more time with Annabelle, building the friendship I’d craved as a child, the haloed idol of my youth slipped away and was replaced by her altogether more self-assured husband.

I didn’t, don’t and probably never will know what Annabelle knew about what was between Matthew and me, but she was my friend. I’d loved her in a childish way and still adored spending time with her, but I never felt guilty about sleeping with her husband. The larger difficulty was sneaking around. Matthew and I were conducting an affair in a small, gossipy town where privacy didn’t come easy. I had to sneak along the street, invent reasons to go into town, dart through his door when the coast was clear, tell my mother I checked my email five times a day because of school projects, leave notes under a plant by his door, pin myself to the wall until he’d drawn the curtains, worry about his aftershave on my coat and secretly wash my expensive lingerie in the bathroom sink.

Communication was the most difficult: frequently I would arrive at his door expecting intimacy only to be greeted by a booming, ‘Oh look, it’s Nat, how unexpected. We haven’t seen you in ages! Barbara and Richard are here, do come in. Have you come to borrow that book?’ and have to endure an afternoon of personaed small talk instead. Or I’d wait all day to visit at the appointed time, but discover Annabelle had changed her plans and run her errands in the morning.

Mothers and brothers and fathers and in-laws, neighbours and doctors, shopkeepers and postmen all thwarted our arrangements, left us tapping out frustrated messages from separate computers, compelling us to dream of a mythical time and place where we could be free to love in the open.

Sometimes we’d plot elaborate Bunburys and, to our surprise, they’d come together: we’d escape for a night in my half-term holidays to return to Swindon, or I’d skip my Wednesday afternoon Psychology class to drive to Rye for a cream tea and a hunt through the second-hand bookshops. But more often than not, these secret passionate or plebeian encounters would be spoilt or at least dissipated by unlucky coincidences.

A favourite free-period picnic spot was the Beachy Head car park in Warren Hill, where Matthew and I would share flasks of coffee and flaky pastries as well as more incriminating things. But two terrifying incidents marked an end to those visits. The first was Felicity Roberts, daughter of Mr and Mrs Roberts who lived next door to Matthew and Annabelle, passing our parked vehicle with her dog Bobby on the way to the footpath while Matthew and I were in the middle of one of those incriminatingly passionate things. I convinced myself she hadn’t seen or hadn’t recognised me and was persuaded to go back the following week, but returning from a lazy amble into Holywell, we found the passenger-side window of Matthew’s car had been smashed and my school-bag stolen. I had to sit in the back avoiding shards of glass on the way home and we developed a flat along a country lane, but none of that was as scary as having to explain to my parents how I’d lost my wallet, house keys, new glasses and a piece of coursework and why I didn’t want to try to claim them on the house insurance.