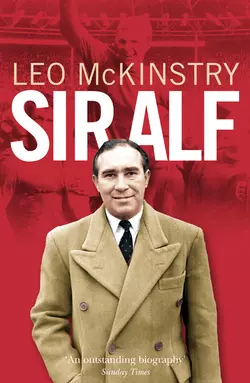

Sir Alf

Leo McKinstry

Since England’s famous 1966 World Cup victory, Alf Ramsey has been regarded as the greatest of all British football managers. By placing Ramsey in an historical context, award-winning author Leo McKinstry provides a thought-provoking insight into the world of professional football and the fabric of British society over the span of his life.Ramsey’s life is a romantic story of heroism. Often derided by lesser men, he overcame the prejudice against his social background to reach the summit of world football.The son of a council dustman from Essex, Ramsey had been through a tough upbringing. After army service during the war, he became a professional footballer, enjoying a successful career with Southampton and Tottenham and winning 32 England caps.But it was as manager of Ipswich Town, and then the architect for England’s 1966 World Cup triumph, that Ramsey will be most remembered. The tragedy was that his battles with the FA would ultimately lead to his downfall. He was sacked after England failed to qualify for the 1974 World Cup and was subsequently ostracised by the football establishment. He died a broken man in 1999 in the same modest Ipswich semi he’d lived in for most of his life.Drawing on extensive interviews with his closest friends and colleagues in the game, author Leo McKinstry will help unravel the true character of this fascinating and often complex football legend.

Sir Alf

Leo McKinstry

A Major Reappraisal of the Life and Times of England’s Greatest Football Manager

This book is dedicated to the memory of Dermot Gogarty, 1958-2005

Another man of dignity, courage and leadership

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u4be16f9a-fb46-59e5-9434-fbbba8913640)

Title Page (#uba47ac4b-a104-502e-b573-20d73ff9a279)

Dedication (#ua8f6c7c7-acfd-50af-9ef2-fd261c3675ea)

Preface (#ubb3189d1-deb1-5466-a8f5-5792f4593d90)

Introduction (#ud706db77-1a36-5cef-a772-3f1954ea56f1)

ONE Dagenbam (#u682ef12a-902a-5b22-8f43-eceea7d46845)

TWO The Dell (#ufb25a90b-4ee7-500e-bef0-eeb6f1b58d72)

THREE White Hart Lane (#u514d3d69-991a-52b8-9bc3-9fa6e27a9d2e)

FOUR Belo Horizonte (#u1cda7351-54b9-5cc2-a1f1-5520479ccb07)

FIVE Villa Park (#litres_trial_promo)

SIX Portman Road (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVEN Lancaster Gate (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHT Lilleshall (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE Hendon Hall (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN Wembley (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN Florence (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE Leon (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN Katowice (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN St Mary’s (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_7c29b38d-550e-586e-9422-231ff5984cb9)

Wembley, 30 July 1966. Amid scenes of jubilation, Geoff Hurst slams the ball into the top left-hand corner of the West German net. After a pulsating match, England are only seconds away from winning the World Cup. But as wave upon wave of ecstatic cheering echoes throughout the Wembley stadium, the England manager remains seated on the bench, showing not a flicker of emotion.

Sir Alf Ramsey’s almost superhuman calmness at the moment of victory has become one of the iconic images of the glorious summer of 1966. For all his outward imperturbability, no one had greater cause to rejoice than him. He was the true architect of England’s triumph, the man who had moulded his players into a world-beating unit. The experts and press had mocked when he had declared, soon after his appointment to the national job, that England would win the World Cup. After 1966, he was never laughed at again. Yet Ramsey was acting entirely in character on that July afternoon at Wembley. In his behaviour, he demonstrated the very qualities that helped to make him such a superb manager: his majestic coolness under pressure; his natural modesty which meant that he always put his players’ achievements before his own; his innate dignity and authority.

Since the World Cup victory, Sir Alf Ramsey has rightly been regarded as the greatest of all British football managers, winning at every level of the game. Through his tactical awareness, motivational powers and judgment of ability, he not only turned England into World Champions, but also, perhaps even more incredibly, he took unfashionable Ipswich Town from the lower reaches of the old Third Division South to the First Division title in the space of just six years. No other manager has been able to equal this record. Sir Alex Ferguson may have won a boardroom-full of trophies at Old Trafford, but he has been almost untested on the highest international stage. Similarly Sir Matt Busby, Brian Clough and Bob Paisley all gained the English championship and the European Cup, but none of them managed any national side, in Clough’s case to his bitter regret, having been turned down for the England job in 1977. Bill Shankly, the legendary boss at Anfield, and Stan Cullis, the iron manager at Molineux, each won three league titles and two FA Cups, but, again, their excellence was confined to the domestic arena. Of international British managers, Jack Charlton may have worked a near miracle with the Republic of Ireland but he could not do the same with any of his clubs, nor could Billy Bingham, who took modest Northern Ireland to successive World Cups in the eighties. Perhaps the man who comes closest to Ramsey was one of his successors at Portman Road, Sir Bobby Robson, who in his long and honourable career won the FA Cup and UEFA Cup with Ipswich Town, the Cup Winners’ Cup with Barcelona and two domestic championships with both PSV Eindhoven and Porto, as well as taking England to the semi-finals of the World Cup in 1990. But the greatest prize eluded him.

For all his extraordinary breadth of achievement, however, Sir Alf Ramsey has always been an elusive figure, an enigma whose life story has remained shrouded in mystery. A private, shy man, he was never at ease with the limelight and throughout his career had an awkward relationship with the media. Even those who worked with him for years, such as his secretary at Ipswich, Pat Godbold, or his longest-serving England player, Bobby Charlton, say that they never got to know him. Partly because of his insecurities about his humble upbringing, he built a protective shield around himself. In contrast to the expansive Sir Bobby Robson, who has written at least four versions of his autobiography, Alf never produced any memoirs, nor did he give many revealing interviews to the press.

There have been three previous books about Sir Alf, of varying quality. In 1970, the journalist Max Marquis wrote a thin, viciously skewed account, Anatomy of a Manager, which was based on recycling negative press stories about Sir Alf. It was hysterical in its vituperation, limited in its scope. Another book, England: The Alf Ramsey Years, by Graham McColl, published in 1988, dwelt entirely on his record as manager of the national team, though it did have the seal of Ramsey’s approval. A more comprehensive biography, Winning Isn’t Everything, was written in 1998 by Dave Bowler, who has also produced a superb life of Alf’s nemesis at Tottenham Hotspur, Danny Blanchflower. Bowler’s portrait was balanced and used much original testimony, and was particularly good on Alf’s tactical innovations. Yet it still left many aspects of Sir Alf’s life and career uncovered.

By dint of extensive research and interviews, I have sought to provide a fuller, more rounded portrait of this remarkable figure. I have been able to unearth new information about his upbringing, his marriage, his early social life, particularly when he was a player at Spurs, his relationship with his England team and the circumstances surrounding his sacking. During my research, I was intrigued to learn of the real reasons why England were knocked out of the World Cup in Mexico in 1970, when Sir Alf displayed a rare but disastrous neglect of certain logistical arrangements.

I have aimed to write more than just a conventional biography. By placing Ramsey in his historical context, I have also sought to analyse professional football and the fabric of British society over the span of his life. One of the many appealing features of Sir Alf’s story is the way it covered a revolution not only in soccer but also in social attitudes. The labourer’s son from Dagenham witnessed the end of the age of deference, the abolition of the maximum wage, the rise of the superstar player, the demise of amateur administrators, the collapse of rigid class structures, the first majority Labour government, the arrival of the permissive society and the disappearance of Empire. Ramsey himself, as a traditionalist in his personal outlook but a revolutionary on the soccer field, appeared to embody that fluid climate of resistance and change.

In helping me to cover this material, I owe a large debt to many people. A great number of ex-England and Ipswich footballers, who were managed by Alf, agreed to give interviews for this book, so I would like to record my thanks to: Jimmy Armfield, Alan Ball, Gordon Banks, Barry Bridges, Sir Trevor Brooking, Allan Clarke, Ray Clemence, George Cohen, John Compton, Ray Crawford, Martin Dobson, Bryan Douglas, John Elsworthy, the late Johnny Haynes, Ron Henry, Norman Hunter, Brian Labone, Jimmy Leadbetter, Francis Lee, Roy McFarland, Ken Malcolm, Gordon Milne, Alan Mullery, Andy Nelson, Maurice Norman, Mike O’Grady, Terry Paine, Alan Peacock, Mike Pejic, Ted Phillips, Fred Pickering, Paul Reaney, Joe Royle, Dave Sadler, Peter Shilton, Nobby Stiles, Ian Storey-Moore, Mike Summerbee, Derek Temple, Peter Thompson, Colin Todd, Tony Waiters and Ray Wilson. I must also express my gratitude to the many Southampton, Spurs and England footballers who gave me the benefit of their views about playing alongside Alf: Eddie Baily, Ted Ballard, Ian Black, Eric Day, the late Ted Ditchburn, Terry Dyson, Stan Clements, Bill Ellerington, Sir Tom Finney, Alf Freeman, Mel Hopkins, Tony Marchi, Arthur Milton, Derek Ufton and Denis Uphill. Ed Speight, a Dagenham-bred youth player at Spurs during Alf’s last days at White Hart Lane, generously showed me some of his correspondence with Alf.

I am, in addition, grateful to those journalists who gave me their views of Alf: Tony Garnett, Brian James, Ken Jones, David Lacey, Hugh McIlvanney, Colin Malam, Jeff Powell, Brian Scovell and Martin Tyler. I am especially indebted to Nigel Clarke, who knew Alf for more than 30 years and cowrote his column for the Daily Mirror in the eighties. Key figures at the FA during Alf’s reign, David Barber, Margaret Fuljames, Wilf McGuinness and Alan Odell, gave me many fascinating insights into Alf’s style of management, while I further benefited from speaking to Hubert Doggart, son of Graham Doggart, who chaired the FA committee that appointed Alf as England manager in 1962. Dr Neil Phillips, the national team doctor in the second half of Alf’s England career, could not have been more helpful with his advice and frank testimony.

Information about Alf’s early days in Dagenham was given by Cliff Anderson, George Baker, Jean Bixby, Phil Cairns, Charles Emery, Father Gerald Gosling, Pauline Gosling, Beattie Robbins, Joyce Rushbrook, Gladys Skinner and Tommy Sloan. Invaluable assistance about other aspects of Sir Alf’s life was provided by Terry Baker, Mary Bates, John Booth, Tommy Docherty, Anne Elsworthy, Peter Little, Margaret Lorenzo, Matthew Lorenzo, Bill Martin, Pat Millward, Tina Moore (widow of Bobby) and Bernard Sharpe.

Several experts were extremely generous in providing me with contact numbers and historical details: David Bull, author of an excellent life of Southampton stalwart Ted Bates; Rob Hadcraft, who wrote a fine study of Ipswich’s Championship-winning season in 1961-62; Kevin Palmer, amongst whose many works is a history of Spurs’ two titles in 1950-51 and 1960-61; and Andy Porter, who has an encyclopaedic knowledge of ex-professionals’ careers. Pat Godbold, still working at Ipswich after more than half a century, not only gave me an interview about her time as secretary to Alf but also helped with Ipswich contacts. Roy Prince, archivist with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry Association, shed some light on Sir Alf’s army career.

For all their help with other research material, I am grateful to staff at the BBC archives, the ITN archives, the British Newspaper Library, Southampton Central Reference Library, the Register of Births, Marriages and Deaths, the Probate Division, the Press Association, the library of the Daily Mail, Tottenham Hotspur FC, the Barking and Dagenham Record office at Valence House Museum, the Barking and Dagenham Recorder and the Football Association.

Lady Victoria Ramsey, Sir Alf’s widow, felt she could not co-operate with this book, though she did write to me expressing how devoted she was to her late husband.

I would like to thank Tom Whiting and Michael Doggart at HarperCollins for overseeing this project and giving me endless encouragement and support.

Finally, I owe a huge debt to my dear wife Elizabeth, who put up with the many, isolated months I spent in research and writing without complaint. I can never thank her enough for putting me on the path to becoming an author.

Leo McKinstry

Coggeshall, Essex, April 2006

Introduction (#ulink_7c29b38d-550e-586e-9422-231ff5984cb9)

15 May 1999. The ancient Suffolk church of St Mary-le-Tower in Ipswich had never previously held such a large or distinguished congregation. Three hundred mourners were crowded tightly on its polished wooden pews, while hundreds more lined the streets outside. England’s greatest living footballer, Sir Bobby Charlton, sat near the front, looking more sombre than ever. Alongside him were colleagues from the World Cup-winning team of 1966, including the bald, bespectacled Nobby Stiles, the flame-haired Alan Ball and Bobby’s own gangly brother Jack, who had left his Northumberland home at first light to attend the event.

They had gathered on a bright afternoon to pay their last respects at the memorial service of Sir Alfred Ernest Ramsey, the former England and Ipswich manager who had died at the end of April after a long illness. The venerable provincial setting was appropriate to the man whose life was being honoured, since modesty was one of the hallmarks of his personality. For all his success as both player and manager, for all his brilliance as a leader, he continually shunned the limelight and was uneasy with public adulation. The august Gothic expanse of Westminster Abbey or the classical grandeur of St Paul’s would not have suited a farewell for this least bombastic of men.

The personal qualities of Sir Alf were referred to throughout the service. Afterwards, outside the church, former players spoke of his loyalty, his essential decency and his strength of character. ‘He was an incredibly special manager. I just loved being with him, because I knew everything was straight down the line,’ said Alan Ball. ‘He was responsible for the greatest moment I had as a footballer and I will never forget or be able to thank him enough for that,’ said Jack Charlton.

In a moving eulogy, George Cohen, another of the 1966 Cup winners, described Ramsey as ‘not only a great football manager but a great Englishman’. Highlighting the way Sir Alf would stick by his players, Cohen gave the example of the occasion when Sir Alf refused to give in to pressure from FA officials to drop Nobby Stiles from the 1966 side after a disastrous challenge on the French player Jacques Simon. Though the tackle, according to Cohen, had been ‘so late Connex South East would have been embarrassed by it,’ Sir Alf supported Stiles to the hilt and even threatened to resign if the FA ordered him to change the team. In a voice cracking with emotion, Cohen continued: ‘Sir Alf established a strong bond with his players who stood before every other consideration. We all loved him very much indeed. What Alf created was a family that is still as strong today in feeling and belief as it was thirty-three years ago when we won the World Cup.’ Cohen then speculated as to how Alf might have reacted to such words of praise. ‘If he is looking down at this particular moment, he is probably thinking, “Yes, George, I think we have had quite enough of that.” Finally, Cohen turned in the direction of Sir Alf’s grieving widow, Lady Victoria. ‘Alf changed our lives, not just because of what we achieved with him but because our lives were richer for having known and played for him. He was an extraordinary man. Thank you for sharing him.’

Though the memorial service had been billed as ‘a celebration’ of Sir Alf’s life, it was inevitable that the day should also be wreathed in sadness at his loss. ‘I could not be more upset if he was family,’ said Sir Bobby Charlton. Big Ted Phillips, one of Ipswich’s strikers during Ramsey’s years at the Suffolk club, told me: ‘At Alf’s memorial service, I could not speak. There were tears rolling down my cheeks. They wanted me to say a few words, but I told them I couldn’t do it. Alf meant so much to me. He was a superb guy. He was unique. Under him at Ipswich, we were like a big family.’

Yet the sense of sorrow went much deeper than merely regret at the passing of one of England’s modern heroes. There was also a mixture of guilt, disappointment and anger that, during his lifetime, Sir Alf had never been accorded the recognition he deserved. He might have been the man who, in the words of Tony Blair, ‘gave this nation the greatest moment in our sporting history,’ but he was hardly treated as such by the football establishment. Throughout his career as England manager, many in the FA regarded him with suspicion or contempt. He was never given a winner’s medal for the 1966 World Cup victory, something that rankled with him right up to the moment of his death. His pay was always pitifully low, far worse than most First Division managers of his time, and when he was sacked in 1974, he was given only a meagre pension.

The last 25 years of his life were spent in a sad, twilight existence. The lack of money was compounded by the refusal of the football authorities to make any use of his unparalleled knowledge of the game. While football enjoyed an embarrassment of riches from the early nineties onwards, Sir Alf was left in uncomfortable exile, isolated and ignored. As late as 1996, the FA denied him any participatory role in the ceremonies to mark the opening of the European Championship in England. ‘I sometimes look back and become bitter about it. I achieved something perhaps no manager will ever do again, yet the wealth of the game passed me by. I would have liked to have retired in comfort, and have no worries about money, but that has not been the case. And I couldn‘t understand why, after I left the FA, nobody there was prepared to let me work for my country,’ he said in 1996.

This neglect of Sir Alf was symbolized by the absence from his memorial service of a host of key figures from the football world, despite the attendance of most of the 1966 side. Invitations were sent to all 92 Football League clubs, but only five of them were represented. Neither the then England manager Kevin Keegan nor any Premiership manager were present, though there were no fixtures that Saturday. Not one current England player showed up. As Gordon Taylor, Chairman of the Professional Footballers’ Association, put it afterwards: ‘It is amazing. If we cannot honour our heroes, what is the point of it all – and was there ever a greater hero for our game than Sir Alf? Everyone in the English game who could have been here should have been. It is a matter of simple respect.’

But in truth, outside the confines of his England squad, respect was something that Sir Alf had rarely been shown. The reluctance to honour him was not confined to the FA. Ever since the triumph of 1966, he had been the subject of a stream of criticism for his approach to football. His manner was condemned as aloof and forbidding, his methods as over-cautious and ultra-defensive. He was widely seen as the leader who hated flair and distrusted genius, a dull man in charge of a dull team. ‘Ramsey’s Robots’ were said to have taken all grace and romance out of football. ‘Alf Ramsey pulls the strings and the players dance for him. He has theorized them out of the game. They mustn’t think for themselves. They have been so brainwashed by tactics and talks that individual talent has been thrust into the background,’ claimed Bob Kelly, the President of the Scottish FA. The 1966 triumph was belittled as the fruit of nothing more than perspiration, dubious refereeing and home advantage.

Indeed, many critics went even further, claiming that winning the World Cup had been disastrous for British football in the long-term, because it encouraged a negative style of play. Particularly regrettable, it was said, was his abandonment of wingers in favour of a mundane 4-3-3 formation, which relied more on packing the midfield than in building attacks from the flanks. Sir Alf’s enthusiasm for the aggressive Nobby Stiles was seen as typical of his dour outlook, as was his preference for the hard-working Geoff Hurst over the more creative, less diligent Jimmy Greaves in the final itself against West Germany. In Alf’s England, it seemed, the workhorse was more valued than the thoroughbred. The doyen of Irish football writers, Eamon Dunphy, who played with Manchester United and Millwall, put it thus: ‘Alf came to the conclusion that his players weren’t good enough to compete, in any positive sense, with their betters. His response was a formula which stopped good players.’ Similarly, the imaginative Manchester City coach Malcolm Allison argued that ‘to Alf’s way of thinking, skill meant lazy’.

This chorus of criticism reached full volume in the early seventies, when Sir Alf became more vulnerable because of poor results. He was the Roundhead who kept losing battles. As England were knocked out of the European Championship by West Germany in 1972, Hugh McIlvanney summed up the mood against Alf:

Cautious, joyless football was scarcely bearable even while it was bringing victories. What is happening now we always felt to be inevitable, because anyone who sets out to prove that football is about sweat rather than inspiration, about winning rather than glory, is sure to be found out in the end. Ramsey’s method was, to be fair, justifiable in 1966, when it was important that England should make a powerful show in the World Cup, but since then it has become an embarrassment.

Some of the attacks grew vindictive, with Alf painted as a relic of a vanishing past, clinging on stubbornly to players and systems no longer fit for the modern age. His old-fashioned, stilted voice and demeanour were mocked, his lack of flamboyance ridiculed. In early 1973, soon after England had beaten Scotland 5-0 at Hampden, with Mick Channon performing well up front, the satirical magazine Foul! carried a cruel but rather leaden article entitled ‘Lady Ramsey’s Diary’, parodying the Private Eye series of the time about Downing Street, ‘Mrs Wilson’s Diary’. One extract ran:

He’s terribly worried about this Mr Shannon (sic). ’You see, my dear,’ he told me (it’s amazing how different he sounds after those elocution lessons), ‘we just can’t afford to have individuals playing so well. It undermines the whole team effort. Besides, people will start expecting us to score five goals in every game, and we can’t have that.’

The critics had their way in April 1974, when Sir Alf was sacked as manager after eleven years in the post. The FA’s decision was hardly a surprise, given England’s failure to qualify for the World Cup the previous autumn. But it still fell as a painful blow to Sir Alf, one from which he never really recovered. He once explained that only three things mattered to him – ‘football, my country and my wife’. Football had turned out to be a fickle mistress, and for the remainder of his years he carried a feeling of betrayal. ‘Football has passed me by,’ he said towards the end of his life.

Since his sacking, no other England manager has come near to the pinnacle he climbed. When he departed in 1974, it seemed likely that England might one day reach that peak again. In the subsequent 30 years and more, however, the national side has endured one failure after another, with just two semi-finals in major championships during those three decades. Yet it should also be remembered that before Sir Alf’s arrival as manager in 1963, England’s record was equally dismal, having never gone further than a World Cup quarter-final; indeed in 1950, the national side suffered what is still the greatest upset in the history of global soccer, losing 1-0 to the unknown amateurs of the USA. Set in the context of England’s sorry history, therefore, the extent of Sir Alf’s achievement becomes all the more remarkable, putting into perspective much of the carping about his management.

He might not have inspired electrifying football, but for most of his reign he achieved results that would have been the envy of every manager since. Nobby Stiles told me: ‘I cannot say enough in favour of Alf Ramsey. His insights were unbelievable. I would have died for him.’ It is a telling fact that the 1970 World Cup in Mexico is the only occasion when England have ever gone into a major tournament as one of the favourites to win it – in 1966, England, still living with the burdens of their past record, were regarded as outsiders. The status that England had earned by 1970 in itself is a tribute to the supreme effectiveness of Ramsey’s leadership. Moreover, his success in 1962 in bringing the League Championship to Ipswich Town, an unheralded Third Division club before he took over, is one of the most astonishing feats in the annals of British football management, unlikely ever to be surpassed.

Yet even now, as nostalgia for the golden summer of 1966 becomes more potent, the memory of Sir Alf Ramsey is not one treasured by the public. He is nothing like as famous as David Beckham, or George Best or Paul Gascoigne, three footballers who achieved far less than him on the international stage. In his birthplace of Dagenham, he seems to have been airbrushed from history. There is no statue to him, no blue plaque in the street where he was born or the ground where he first played. No road or club or school bears his name. The same indifference is demonstrated beyond east London. When the BBC recently organized a competition to decide what the main bridge at the new Wembley stadium should be called, Sir Alf Ramsey’s name was on the shortlist. Yet the British public voted for the title of the ‘White Horse Bridge’, after the celebrated police animal who restored order at the first Wembley FA Cup Final of 1923 when unprecedented crowds of around 200,000 were spilling onto the pitch. With all due respect to this creature, it is something of an absurdity that the winning manager of the World Cup should have to trail in behind a horse. As one of Ramsey’s players, Mike Summerbee, puts it: ‘Alf Ramsey’s contribution to international football was phenomenal. Yet the way he was treated was a disgrace. We never look after our heroes and in time we try to pull them down. I tell you something, they should have a bronze statue of Alf at the new Wembley. And they should call it the Alf Ramsey stadium.’

Part of the failure to appreciate the greatness of Alf Ramsey has been the result of his severe public image. He was a man who elevated reticence to an art form. With his players he could be amiable, sometimes even humorous, but he presented a much stonier face to the press and wider world. The personification of the traditional English stiff upper lip, he never courted popularity, never showed any emotion in public. His epic self-restraint was beautifully captured at the end of the World Cup Final of 1966, when he sat impassively staring ahead, while all around him were scenes of joyous mayhem at England’s victory. The only words he uttered after Geoff Hurst’s third goal were a headmasterly rebuke to his trainer, Harold Shepherdson, who had leapt to his feet in ecstasy. ‘Sit down, Harold,’ he growled. Again, as the players gathered for their lap of honour, they tried to push Alf to the front to greet the cheers of the crowd. But, with typical modesty, he refused. This outward calm, he later explained, was not due to any lack of inner passion but to his shyness. ‘I’m a very emotional person but my feelings are always tied up inside. Maybe it is a mistake to be like this but I cannot govern it. I don’t think there is anything wrong with showing emotion in public, but it is something I can never do.’

Nowhere was Ramsey’s awkwardness more apparent than in his notoriously difficult relationship with the media. Believing all that mattered were performances on the field, he made little effort to cultivate journalists. ‘I can live without them because I am judged by the results that the England team gets. I doubt very much whether they can live without me,’ he once said. Hiding behind a mask of inscrutability, he usually would provide only the blandest of answers at press conferences or indeed none at all. He trusted a select few, like Ken Jones and Brian James, because he respected their knowledge of football, but most of the rest of the press were given the cold shoulder. He also had a gift for humiliating reporters with little more than a withering look. As Peter Batt, once of the Sun, recalls: ‘There was a general, utter contempt from him. I don’t think anyone could make you feel more like a turd under his boot than Ramsey. It is amazing how he did it.’ This hostile attitude led to a string of incidents throughout his career. Shortly after England had won the World Cup, for instance, Ramsey was standing in the reception of Hendon Hall, the team’s hotel in north-west London. A representative of the Press Association came up to him and said:

‘Mr Ramsey, on behalf of the press, may I thank you for your co-operation throughout the tournament?’

‘Are you taking the piss?’ was Alf’s reply.

On another occasion in 1967, he was with an FA team in Canada for a tournament at the World Expo show. As he stood by the bus which would take his team from Montreal airport to its hotel, he was suddenly accosted by a leading TV correspondent from one of Canada’s news channels. The clean-cut broadcaster put his arm around England’s manager, and then launched into his spiel.

‘Sir Ramsey, it’s just a thrill to have you and the world soccer champions here in Canada. Now I’m from one of our biggest national stations, going out live coast to coast, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And, Coach Ramsey, you’re not going to believe this but I’m going to give you seven whole minutes all to yourself on the show. So if you’re ready, Sir Ramsey, I am going to start the interview now.’

‘Oh no you fuckin’ ain’t.’ And with that, a fuming Coach Ramsey climbed onto the bus.

Such dismissiveness might provoke smiles from those present, but it ultimately led to the creation of a host of enemies in the press. When times grew rough in the seventies, Alf was left with few allies to put his case. The same was true of his relations with football’s administrators, whom he regarded as no more than irritants; to him they were like most journalists: tiresome amateurs who knew nothing about the tough realities of professional football. ‘Those people’ was his disdainful term for the councillors of the FA. He despised them so much that he would deliberately avoid sitting next to them on trips or at matches, while he described the autocratic Professor Harold Thompson, one of the FA’s bosses, as ‘that bloody man Thompson’. But again, when results went against Sir Alf, the knives came out and the FA were able to exact their revenge.

The roots of Sir Alf’s antagonism towards the media and the FA lay in his deep sense of social insecurity. He was a strange mixture of tremendous self-confidence within the narrow world of football, and tortured, tongue-tied diffidence outside it. He had been a classy footballer himself in the immediate post-war era, one of the most intelligent full-backs England has ever produced, and was never afraid to set out his opinions in the dressing-rooms of Southampton and Spurs, his two League clubs. Performing his role as England or Ipswich manager, he was the master of his domain. No one could match him for his understanding of the technicalities of football, where he allied a brilliant judgement of talent to a shrewd tactical awareness and a photographic memory of any passage of play. ‘Without doubt, he was the greatest manager I ever knew, a fantastic guy,’ says Ray Crawford of Ipswich and England. ‘He had a natural authority about him. You never argued with him. He was always brilliant in his talks because he read the game so well. He would come into the dressing-room at half-time and explain what we should be doing, and most of the time it came off. He was inspirational that way.’ Peter Shilton, England’s most capped player, is just as fulsome: ‘From the moment I met Sir Alf I knew he was someone special. He was that sort of person. He was a man who inspired total respect. Any decision he made, you knew he made it for the right reason. He had real strength of character. I have been with other managers who were not as strong in the big, big games. But Alf could rise above the pressure and dismiss irrelevancies.’

Yet Sir Alf never felt comfortable when taken out of the reassuring environment of running his teams. All his ease and self-assurance evaporated when he was not dealing with professional players and trusted football correspondents. He could cope with a World Cup Final but not with a cocktail reception. ‘Dinners, speeches,’ he used to say of the FA committee men, ‘that’s their job.’ Amongst the Oxbridge degrees of the sporting, political or diplomatic establishments, he felt all too aware of his humble origins and lack of education. Born into a poor, rural Essex family, he left school at fourteen and took his first job as a delivery boy for the Dagenham Co-op. To cope with this insecurity, Sir Alf devised a number of strategies. One was to erect a social barrier against the world, avoiding all forms of intimacy. That is why he could so often appear aloof, even downright rude. From his earliest days as a professional, he was reluctant to open up to anyone. This distance might have been invaluable in retaining his authority as a manager, but it also prohibited the formation of close friendships.

Pat Godbold, his secretary throughout his spell as Ipswich manager from 1955 to 1963, says: ‘I was twenty when Alf came here. My first impression was that he was a shy man. I think that right up to his death he was a very shy man. You could not get to know him. He was a good man to work for, but I can honestly say that I never got to know him.’ Sir Alf guarded the privacy of his domestic life with the same determination that he put into management. The mock-Tudor house on a leafy Ipswich road he shared with Lady Victoria – or Vic, as he always called her – was his sanctuary, not a social venue. Anne Elsworthy, the wife of one of the Championship-winning Ipswich players of 1962, recalls Sir Alf and Lady Ramsey as a ‘a very private couple. After he retired, I would occasionally see them in Marks and Spencer’s in Ipswich, but all they would say would be ‘Good morning’. They were not the sort to stand around chatting in a supermarket. When Alf went to play golf, he would just go, complete his round. He would not hang around the bar.’

Another strategy was to reinvent himself as the archetypal suburban English gentleman. The impoverished Dagenham lad, who could not even afford to go to the cinema until he was fourteen, was gradually transformed in adulthood into someone who could have easily been mistaken for a stockbroker or a bank-manager. The pinstripe, made of the finest mohair, was a suit of armour to protect from his detractors. When he went to Buckingham Palace to collect his knighthood in 1967, he went to extraordinary lengths to ensure that he was dressed in the exactly the correct attire. But by far the most obvious change was in his voice, allegedly the result of elocution lessons, as he dropped his Essex accent in favour of a form of pronunciation memorably described by the journalist Brian Glanville as ‘sergeant-major posh’. Like Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion, Sir Alf occasionally betrayed his origins when he slipped into the vernacular of his childhood, as on the embarrassing occasion in a restaurant car travelling to Ipswich when, in the presence of the club’s directors, he told a waitress during dinner, ‘No thank you, I don’t want no peas.’

Tony Garnett, the Suffolk-based journalist who covered Ipswich’s great years under Sir Alf, told me: ‘He did drop some real clangers when he was trying to talk proper, as they say. One of the best was when Ipswich went abroad after they had won the championship and Alf began to talk about going through ‘Customs and Exercise.’ Nobody dared to correct him. He could not do his ‘H’s properly, nor his ‘ings’ at the end of a word.’ With his attempts at precision, his lengthy pauses, his twisted syntax and his frequent repetition of the same phrase – ‘most certainly’ and ‘in as much as’ were two particular favourites – it seemed at times that he was almost trying to master a foreign tongue.

The Blackpool and England goalkeeper in the 1960s, Tony Waiters, who led Canada to the 1986 World Cup finals and has wide experience of working in America, says: ‘It was always worth listening to Alf. But occasionally he would fall down on his pronunciation or would drop an “H” every so often. As a coach myself, I am aware that if you say the wrong thing, it could come back to haunt you. And sometimes Alf would give an indication that this was not his natural way of speaking. He was very deliberate in what he said. I work with a lot of people who are coaching in their second language. Generally speaking they slow down because they are thinking ahead and almost rehearsing in their own mind what they are going to say. With Alf, it was always good stuff but maybe he had to do a bit of mental gymnastics as he prepared to speak.’

For all his anxiety about his accent and his appearance, Sir Alf could never have been described as a snob. Just the opposite was true. He loathed pretension and social climbing, one of the reasons why he so disliked the fatuities of the FA’s councillors. David Barber, who has worked at the FA since 1970, beginning as a teenage clerk, recalls Alf’s lack of self-importance: ‘Right from the moment I first took a job there, I was not in the slightest bit overawed by him. Though he was the most famous man in football at the time, he was down to earth. He was very nice, treated me like a colleague, not an office boy. He was uncomfortable with the press and FA Council members and in public could be a shy man, but with people like me, whom he worked with on a daily basis, he could not have been more friendly.’

Utterly lacking in personal vanity, Alf deliberately avoided the social whirl of London and was unmoved by fashionable restaurants and hotels. His knighthood did not change him in the slightest, while he always retained a fondness for the activities of his Dagenham youth, such as a visit to the greyhound track accompanied by a pint of bitter and some jellied eels. As reflected by his penurious retirement, he refused to exploit his position for personal gain, unlike most of his successors; in fact, it was partly his repugnance at commercialism that led to his downfall.

Alf’s favourite self-preservation strategy, though, was to ignore the world outside and retreat into football, the one subject he really understood. Since his childhood, he had been utterly obsessed with the game. He was kicking a ball before he was learning his alphabet. It was the great abiding passion of his life. When he was truly engaged with the sport, his introversion would disappear, the barriers would fall. Apart from his wife, nothing else had the same importance to him. As his captain at Ipswich, Andy Nelson, remembers: ‘He was a very private, quiet man, very unhappy to have any conversation that was unrelated to football. When we went on the train, we used to have a little card school. Roy Bailey, our goalkeeper, was a big figure in that. Alf would come into our compartment and start talking about football. And then Roy would say, “Anyone seen that new film at the pictures?” You would literally be rid of Alf in two minutes. He’d be off, gone.’ Hugh McIlvanney told me that he could see the change in Alf’s personality as soon as he shifted the ground onto football. ‘Alf liked a drink and he could get quite bitter when he was arguing about football. That front of restraint, which was his normal face for the public, was pretty superficial; he quite liked to go to war. All the insecurity he so obviously had socially did not apply for a moment to football. He was utterly convinced of his case – and with good reason. He was a great manager in any sense.’

It is impossible to deny that, in his obsession with football, Sir Alf was a one-dimensional figure. He had a child-like affection for movies, especially westerns and thrillers, enjoyed pottering about his Ipswich garden and was genuinely devoted to Vickie. But he was uneasy with any discussions about politics, current affairs or art beyond privately mouthing the conventional platitudes of suburban conservatism. An unabashed philistine, he turned down an offer to take the England team to a gala evening with the Bolshoi Ballet during a trip to Moscow in 1973; instead, he arranged a showing of an Alf Garnett film at the British Embassy. He had an ingrained xenophobic streak, and had little time for any foreigners, in whose number he included the Scots. In fact, his dislike of the ‘strange little men’ north of the border was so ingrained that one Christmas, when he was given a pair of Paisley pyjamas as a present, he soon changed them at the shop for a pair of blue and white striped ones.

Nigel Clarke, the experienced journalist who worked more closely with Sir Alf than anyone else in Fleet Street and wrote his column for the Daily Mirror in the 1980s, provides this memory: ‘Alf was certainly conservative with a small ‘c’. But he was not a worldly man and we never really talked about current affairs or wider political issues. He was just happy talking about football. I think that was partly because he knew the subject so well. He could talk about football until the cows came home. He never wanted to discuss governments or religion or anything like that. His life revolved around football. He had little conversation about anything else. His face would lighten up when you mentioned something about the game. We would be sitting in the compartment of a train, going to cover a match for the paper, and Alf would be dozing. Then I might refer to some player and his eyes would open, he would sit up instantly, and say, ‘Oh really, yes, I know him. I saw him play recently.’ He just loved football, loved anyone who shared his passion for it.’

When it came to football itself, Sir Alf Ramsey was anything but a one-dimensional figure. Beneath his placid exterior, the flame of his devotion to the game burned with a fierce intensity. It was a strength of commitment that made him one of the most contradictory and controversial managers of all time. He was a tough, demanding character, who could be strangely sensitive to criticism, a reserved English gentleman who was loathed by the establishment, an unashamed traditionalist who turned out to be a tactical revolutionary, a stern disciplinarian who was not above telling his players to ‘get rat-arsed’. His ruthlessness divided the football world; his stubbornness left him the target of abuse and condemnation. But it was his zeal that put England at the top of the world.

ONE Dagenbam (#ulink_4599549c-dc3d-5123-abfe-6144da9e5a3d)

The Right Honourable Stanley Baldwin, the avuncular leader of the Conservative Party in the inter-war years, was not usually a man given to overstatement. But in 1934 he was so impressed by the new municipal housing development at Becontree in Dagenham that he was moved to write in an official report:

If the Becontree estate were situated in the United States, articles and newsreels would have been circulated containing references to the speed at which a new town of 120,000 people had been built. If it had happened in Vienna, the Labour and left Liberal press would have boosted it as an example of what municipal socialism could accomplish. If it had been built in Russia, Soviet propaganda would have emphasized the planning aspect. A Pudovkin film might have been made of it – a close up of the morning seen on cabbages in the market gardens; the building of the railway lines to carry bricks and wood, the spread of the houses and roads with the thousands of busy workers, gradually engulfing the fields and hedges and trees. But Becontree was planned and built in England where the most revolutionary social changes can take place and people in general do not realize they have occurred.

The Becontree estate was certainly dramatic in conception and scale. It was first planned in 1920, when the London County Council saw that a radical expansion in the number of homes would be needed to the east of the city, in order both to provide accommodation for the men returning from the Great War and to alleviate the terrible slum conditions of the East End. This was to be Britain’s first new town, a place providing ‘homes fit for heroes’. The scheme to convert 3000 acres of land into a vast urban community was, as the LCC’s architect boasted, ‘unparalleled in the history of housing’. The establishment of the Ford motor works in Dagenham in 1929 was a further spur to the urbanization of the area. By 1933, with the building programme reaching its peak, the LCC proclaimed that, ‘Becontree is the largest municipal housing estate in the world.’

Right in the midst of this gargantuan sprawl, untouched by bulldozer or bricklayer, there stood a set of rustic wooden cottages. These low, single-storey dwellings had been built in 1851, when Dagenham was entirely countryside. For all their quaintness, they were extremely primitive, devoid of any electricity or hot running water. And it was in one of them, Number Six Parrish Cottages, Halbutt Street, that Alfred Ernest Ramsey was born on 22 January 1920, the very year that saw the first proposals for the Becontree Estate. The row of Parrish Cottages remained throughout the development of the estate, an architectural and social anachronism holding out against the tide of modernity. They did not even have electricity installed until the 1950s and they were not finally pulled down until the early 1970s. In one sense, the cottage of his birth is a metaphor for the life of Alf Ramsey: the arch traditionalist, modest in spirit and conservative in outlook, who refused to be swept along by the social revolution which engulfed Britain during his career.

For much of his early life, Ramsey was not completely honest about his date of birth. In his ghost-written autobiography, published in 1952, he stated baldly that he was born ‘in 1922’, without giving any details of the month or the day. Now the reason for this was not personal vanity but sporting professionalism. When Ramsey was trying to force his way into League football at the end of the Second World War, a difference of two years could make a big difference to the prospects of a young hopeful, since a club would be more likely to take on someone aged 23 than 25. In such a competitive world, Ramsey felt he had to use any ruse which might work to his advantage. His dishonesty was harmless, and it passed largely unnoticed until after he received his knighthood in 1967. Having been asked to check his entry for Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Sir Alf decided not to mislead that most elevated of reference works. As Arthur Hopcraft put it in the Observer, ‘Alf Ramsey the dignified, the aspirer after presence, could not, I am convinced, give false information to the book of the Peerage.’ But by then the issue of his age had ceased to matter; in any case, because of the stiffness of his character, he had always seemed much older than his stated years.

Parrish Cottages may have become outdated with the arrival of the Becontree Estate, but when Alf Ramsey was an infant they were typical of rural Dagenham, where farming was still the main source of subsistence. ‘Dagenham was like a little hamlet. It was much more countrified until they built the big estate. There was a helluva lot of open space here in the twenties,’ says one of Alf’s contemporaries Charles Emery. ‘Most people think of Dagenham as an industrial area. But until I was six there was nothing but little country lanes. I saw Dagenham grow and grow,’ Alf wrote in 1970. A reflection of that environment could be seen at the Robin Hood pub in the north-west of the borough, where customers drank by the light of paraffin or oil lamps, and the landlord had to double as a ploughman. As one account from 1920 ran: ‘A customer would enter the bar and finding it empty, would shout across the fields for the landlord. After a time he would arrive, and wiping his hands free from the soil, would draw a pint of beer, have a talk about the weather, and then depart again to the fields.’

A striking picture of life in Dagenham in the early twenties was left by Fred Tibble, who died in 2003 after serving as a borough councillor for 35 years. He grew up with Alf, often playing football and cricket with him, and remembered him as ‘a very quiet boy who really loved sport’. The late Councillor Tibble had other memories:

We were very much Essex, we were country people. Many people came to the village selling things. There was a muffin man, who would come to the area once a week, ringing a bell with a tray of muffins on his head. The voluntary fire brigade was based in Station Road in the early 1920s, and when the maroon sounded, men would have to leave their jobs and homes to man the appliances. It could be difficult in the daytime, as they would have to try to get the horse which was being used for the milk round. At the weekends and summer evenings, the police used a wheel-barrow to take drunks from the pub to the police station. The drunks would be strapped into the barrow. We always found that amusing. Sometimes we would climb up the slaughterhouse wall to take a look at cattle being pole-axed. We often hoped to get hold of a pig’s bladder, which we could stuff with paper and play football with.

It was a country life that young Alf relished, especially because it provided such scope for football. He wrote in Talking Football:

Along with my three brothers, I lived for the open air from the moment I could toddle. The meadow at the back of our cottage was our playground. For hours every day, with my brothers, I learnt how to kick, head and control a ball, starting first of all with a tennis ball and it is true to say that we found all our pleasure this way. We were happy in the country, the town and cinemas offering no attractions to us.

But it was also a deprived existence, one that left him permanently defensive about his background. ‘We were not exactly wealthy,’ he admitted euphemistically. His later fastidious concern for his appearance stemmed from the fact that his family was poorer than most in the district, so he was not always dressed as smartly as he would have liked. If anyone commented on this difference, he retreated further into his shell, ‘We grew up together in Halbutt Street. Alf was very introverted, not very forthcoming. I sometimes went to his house, a very old cottage, little more than a wooden hut. His family were just ordinary people. He was not especially well-turned out as a child. That only came later, when he bettered himself,’ says his contemporary Phil Cairns.

Alf’s father, Herbert Ramsey, made a precarious living from various manual activities. He owned an agricultural small-holding, while on Saturdays he drove a horse-drawn dustcart for the local council. He also grew vegetables and reared a few pigs in the garden at the front of Parrish Cottages. He has sometimes been described as ‘a hay and straw dealer’, though it is interesting that when Alf married in 1951, he referred to his father’s occupation as a ‘general labourer’. Others, less generously, have said he was little more than a ‘rag-and-bone man’. Alf’s mother, Florence, was from a well-known Dagenham family called the Bixbys.

Pauline Gosling, who was a neighbour of the Ramseys in Parrish Cottages, recalls:

The cottages had outside toilets and no hot water. If you wanted a bath, you had to heat up the water in a copper pan and then fill a tin tub by the fire. Friday was usually bath night. There was no electricity, so you had to use oil lamps. If you wanted to go out to the toilet at night, you had to take one of those. Alf’s mother was a lovely lady. She and my mother were very close. They were a quiet family, very private, like Alf. They had worked the land for years around Dagenham. My own great-grandfather used to work on the land with Alf’s great grand-dad.

Gladys Skinner, another former neighbour, says:

There was an outside loo in a little shed in their back garden. You could see their tin bath hanging up on the wall outside. They were never a family to tell other people their business. Alf’s mother was a dear old thing. When they were installing electricity round here, she wouldn’t have it, said it frightened her. Alf’s father was also a very nice man. He sometimes kept pigs and we would go round have a look at the little piglets in the garden.

Alf always maintained that his was a close family. ‘My mother is in many ways very like me. Like me she doesn’t show much emotion. She didn’t, for instance, seem very excited when I received my knighthood. But she is very human and I like to think I was like her in that respect,’ he wrote in a 1970 Daily Mirror article about his life. He also felt that, despite the lack of money, his parents had taught him how to conduct himself properly. ‘He told me that he was brought up very strictly and that is why he was such a stickler for punctuality and courtesy. He said that it was part of his upbringing to be courteous and polite to people,’ says Nigel Clarke.

Alf was one of five children. He had two older brothers, Len and Albert, a younger brother Cyril, and a sister, Joyce, though he was the only one to go on to achieve public distinction. Cyril worked for Ford; Len, nicknamed ‘Ginger’, became a butcher; and Joyce married and moved to Chelmsford. Albert, known in Dagenham as ‘Bruno’, was the least inspiring of the siblings, utterly lacking in Alf’s ambition or focus. A heavy drinker, he earned his keep from gambling and keeping greyhounds. Alf himself was always interested in the dog track, liked a bet and was a shrewd gambler. But he never allowed it to dominate his life in the way that Albert did. ‘Bruno was a big chap. I can picture him now, with a trilby turned up at the front. He had a great friend called Charlie Waggles and the two of them never went out to work. At the time I thought that was terrible. They just gambled on the dogs,’ says Jean Bixby, who grew up in Dagenham at this time. In later life, Bruno’s disreputable life would cause Alf some embarrassment.

From the age of five, Alf attended Becontree Heath School. Now demolished, Becontree Heath had a roll of about 200, covering the ages of four to fourteen. Alf was neither especially diligent about his lessons nor popular with his fellow pupils. ‘I was never particularly clever at school. I seem to have spent more time pumping at footballs and carrying goalposts,’ Alf once said. ‘He was a year above me but I remember him all right. Know why? ’Cos he looked like a kid you wouldn’t get to like in a hurry,’ said one of them in a Sun profile of Sir Alf in 1971. For all his introspection, Alf was not a cowardly child, as he proved in the boxing ring at school. ‘I weighed only about five stones, but I was a tough little fighter. I won a few fights,’ he later recalled. But when he was ten years old, he was pulverized in a school tournament by a much larger opponent. ‘He was about a foot bigger than I was and I was as wide as I was tall. I was punched all over the ring.’ That put a halt to his school boxing career, though for the rest of his life he retained a visible scar above his mouth, a legacy of that bout. Alf was also good at athletics, representing the school in the high jump, long jump, and the one hundred and two hundred yards. And he was a solid cricketer, with a sound, classical batting technique.

But, as in adulthood, football was what really motivated Alf Ramsey. ‘He did not have much knowledge of the world. The only thing that ever seemed to interest him was football,’ says Phil Cairns. ‘He was very withdrawn, almost surly, but he became animated on the football field.’ From his earliest years, Alf demonstrated a natural ability for the game, his talent enhanced not only by games in the fields behind Parrish Cottages, but also by the long walk to and from school with his brothers. To break the monotony of the journey, which took altogether about four hours a day, the boys brought a small ball with them to kick about on the country lane. On one occasion, Alf accidentally kicked the ball into a ditch, which had filled with about three feet of water after heavy rainfall. He was instructed by his brothers to fish it out. So, having removed his shoes and socks, he waded in, soon found himself out of his depth, and was soaked to the skin. On his return home, he developed a severe cold and was confined to bed for a week. He wrote later: ‘That heavy cold taught me a lesson. I am certain that those daily kick-abouts with my brothers played a much more important part than I then appreciated in helping me secure accuracy in the pass and any ball control I now possess.’

Alf’s ability was soon obvious to his schoolmasters. One of his teachers, Alfred Snow, recalled in the Essex and EastLondon Recorder in 1971: ‘I was teaching at Becontree Heath Primary and I taught Alf Ramsey for two years. I remember him particularly well because he was so good on the football field. It didn’t really surprise me to see him get where he has.’ At the age of just seven, Alf was placed in the Becontree Heath junior side, in the position of inside-left. His brother Len was the team’s inside-right. Alf’s promotion to represent his school meant that, for the first time, he had to have proper boots. His mother went out and bought him a pair, costing four shillings and eleven pence – with Alf contributing the eleven pence from the meagre savings in his own piggy bank. ‘If those boots had been made of gold and studded with diamonds I could not have felt prouder than when I put them on and strutted around the dining room, only to be pulled up by father. “Go careful on the lino, Alf,” he said, “those studs will mark it,”’ Alf’s ghost-writer recorded in Talking Football.

By the age of just nine, Alf, despite being ‘a little tubby’, to use his own phrase, had proved himself so outstanding that he was made the school’s captain, commanding boys who were several years older than himself. He had also been switched to centre-half, the key position in any side of the pre-sixties era. Under the old W-M formation which was then the iron tradition in British soccer, based around two full-backs, three half-backs, two wingers and three forwards, the centre-half was both the fulcrum of the defence and instigator of attacks. It was a role ideally suited to Alf’s precocious footballing intelligence and the quality of his passing.

His performances brought him higher honours. He was selected to play for Dagenham Schools against a West Ham Youth XI, then for Essex Schoolboys, and then in a trial match for London schools. But in this match, Alf’s diminutive stature told against him. He wrote:

I stood just five feet tall, weighed six stone three pounds and looked more like a jockey than a centre-half. In that trial, the opposing centre forward stood five feet, ten and half inches and tipped the scale at 10 stone. After that game I gave up all hopes of playing for London. That centre-forward hit me with everything but the crossbar, scored three goals and in general gave me an uncomfortable time.

Compounding this failure, a rare outburst of youthful impetuosity led to a sending-off for questioning a decision of the referee during a match for Becontree Heath School. The Dagenham Schools FA ordered him to apologize in writing to both the referee and themselves. He did so promptly, but it was not to be his last clash with the authorities.

For all such problems, Alf had shown enormous potential. ‘He was easily the best for his age in the area,’ says Phil Cairns. ‘He was brilliant, absolutely focused on his game. He was taking on seniors when he was still a junior. Everyone in Dagenham who was interested in football knew of Alf because he was virtually an institution as a schoolboy. He was famous as a kid because of his football.’ Jean Bixby’s late husband Tom played with Alf at Becontree Heath: ‘Alf was a very good footballer as a boy. Tom said that he had great control and confidence. He always wanted the ball. He would say to Tom, “Put it over here.”’

Yet Alf’s schoolboy reputation did not lead to any approaches from a League club. He therefore never contemplated trying to become a professional footballer when he left Becontree Heath School in 1934. ‘I was very keen on football but one really didn’t it give much thought. There was no television then, and football was just fun to do,’ he told the Dagenham Post in 1971. Instead, he had to go out and earn a living in Dagenham to help support his family; this was, after all, the depth of the Great Depression in Britain, which spawned mass unemployment, social dislocation and political extremism. Alf first applied for a job at the Ford factory, where wages were much higher than elsewhere. But with dole queues at record levels, competition for work there was intense and he was rejected. Following a family conference about his future, he then decided to enter the retail trade, beginning at the bottom as a delivery boy for the Five Elms Co-operative store in Dagenham. The occupation of a grocer might not be a glamorous one, but at least it was relatively secure. People always needed food, and the phenomenal growth in the population of Dagenham in the 1930s provided a lucrative market for local businesses. In addition, there was a high demand for grocery deliveries in the area, because public transport was poor.

Alf immediately demonstrated his conscientious, frugal nature by giving the great majority of his earnings to the family household. ‘Every day I’d cycle my way around the Dagenham district taking to customers their various needs. My wages were twelve shillings a week. Of this sum, I handed over ten shillings to my mother, put a shilling in the box as savings and kept a shilling for pocket-money,’ he wrote. After several years carrying out these errands, Alf graduated to serving behind the counter at the Co-op shop in Oxlow Lane, only a short distance from his home in Halbutt Street.

He later claimed to be happy in his job, but what he missed was football. For two whole years, he could not play the game at all, since he had to work throughout Saturday and there was no organized soccer in Dagenham on Thursdays, when he had his only free afternoon. But then, in 1936, a kindly shopkeeper by the unfortunate name of Edward Grimme intervened. Grimme had noticed that a large number of talented Dagenham schoolboy footballers were being lost to the game because of their jobs. So he decided to set up a youth team called Five Elms United. Because of his excellent local reputation, Alf was soon asked to join. He had no hesitation in doing so, despite the weekly sixpence subscription, which left him hardly any pocket money. But he did not care. He was once more involved with the game he loved.

Grimme’s Five Elms United held their meetings on Wednesday evenings and played on Sunday mornings in a field at the back of the Merry Fiddlers pub. Playing on the Sabbath was officially banned by the FA in the 1930s. Strictly speaking, after breaking this rule, Alf Ramsey should have been obliged to apply for reinstatement with the Association, once he became a League player, by paying a fee of seven shillings six pence. ‘I was most certainly conscious that Sunday football was illegal then but it presented me with the only opportunity to play competitive football. Technically, I suppose, never having paid the reinstatement fee, I should never have been allowed to play for England or Spurs or Southampton,’ Alf wrote later. So, in effect, the World Cup was won by an ineligible manager.

Playing again at centre-half, Alf showed that none of his ability had disappeared, despite his two-year absence from the game. In fact, he was physically all the more capable because of his growth in height and his regular exercise on the Co-op bicycle. Tommy Sloan, now one of the trustees of the Dagenham Football club, saw Alf play regularly before the war on the Merry Fiddlers ground: ‘It was quite a good pitch there. All the lads played in the usual kit of the time, big shin guards and steel toe caps in their boots. Alf was a very impressive player. He used to tackle strongly, but fairly. He had a very powerful kick, especially at free kicks. He was subdued, never threw his weight about and was a model for any other youngster.’ Alf himself felt he benefited from the demanding nature of those teenage games with Five Elms, ‘I have often looked back upon those matches. Most of them were against older and better teams but we all learnt a good deal from opposing older and more experienced players. They were among the most valuable lessons of my life.’

It is interesting that many of the traits that later defined Alf Ramsey, including his relentless focus on football, his taciturnity and his attempt at social polish, were apparent in his teenage years. For all the poverty of his upbringing in Parrish Cottages, he had nothing like the usual working-class boister-ousness of his contemporaries. George Baker, who grew up near Halbutt Street and later became head of the borough’s recreation department, told me: ‘I was born within two years of Alf and I knew him and his brothers. As a lad, he was not like the locals. He somehow seemed a bit intellectual, a bit distant. He spoke a little bit better than the rest of us. He was pleasant, but he was different.’ Beattie Robbins came to know him in the thirties, because one of her relatives worked with him in the Co-op: ‘I remember him as well spoken, just as he was in later life. He was very nice, but seemed quite shy. I knew him best when he was about 17. He was polite, dignified, a very reserved person. We once went on a coach trip to Clacton with the Five Elms team and he sat quietly on the bus at the front. He did not play around much like some of the others. His life seemed to be just football.’

As he grew older, Alf appeared only too keen to distance himself from his Dagenham roots. The journalist Max Marquis wrote sarcastically in his 1970 biography of Ramsey, ‘There are no indications that Alf is overburdened with nostalgia for his birthplace…in fact the impression is inescapable that he would like to forget all connections with it.’ His Dagenham contemporary Jean Bixby, who worked with Alf’s brother Cyril at Ford, argues: ‘The trouble with Alf Ramsey was that he tried to make himself something that he wasn’t. He went on to mix in different circles and he tried to change himself to fit in with those circles. Yes, even as a child he was slightly different, but he was still ordinary Dagenham. Then he went away and changed. He was not one of the boys anymore. He became conservative, not like the others who all stuck together. He was one apart from them.’

At the heart of this unease, it has often been claimed, was a feeling of embarrassment not just over the poverty of his upbringing, but, more importantly, over the ethnic identity of his family. For Sir Alf Ramsey, knight of the realm and great English patriot, was long said to come from a family of gypsies. This supposed Romany background was reflected in the family’s fondness for the dog track, in the obscure way his father earned his living and in Alf’s own swarthy, dark features. ‘I was always told that he was a gypsy. And when you looked at him, he did look a bit Middle Eastern,’ says his former Tottenham Hotspur colleague Eddie Baily. Alf’s childhood nickname in Dagenham, ‘Darkie Ramsey’, was reportedly another indicator of his gypsy blood. ‘Everyone round here referred to him as “Darkie” and it was to be years later that I found out his name was actually Alf,’ recalled Councillor Fred Tibble. Even today, in multi-racial Britain, there is less tolerance towards gypsies than towards most other ethnic minority groups. And the problems of prejudice would have loomed even larger in the much more homogenous Britain of the pre-war era. In a Channel Four documentary on Sir Alf broadcast in 2002, it was stated authoritatively that ‘Alf had to put up with casual racism. Dagenham locals believed that he came from a gypsy background and so inherited his father’s nickname, Darkie Ramsey.’

There is no doubt that Alf was acutely sensitive about these claims and this may have accounted for some of his habitual reserve. The journalist Nigel Clarke, who knew him better than anyone else did in the press, recalls this incident on tour:

The only time I ever saw Alf really angry was when we were going through Czechoslovakia in 1973 with the England team – in those good old days the press would travel with the team. We were all sitting on the coach as it drove past some Romany caravans. And Bobby Moore piped up, ‘Hey, Alf, there’s some of your relatives over there.’ Alf went absolutely crimson with fury. He would never admit to his Romany background and hated to discuss the subject. He used to say to me, ‘I am just an East End boy from humble means.’ But it was always accepted in the football world that he was a gypsy.

The rumours might have been widely accepted but that did not make them true. Without putting Sir Alf’s DNA through some Hitlerian biological racial profile, it is of course impossible to be certain about his ethnic origins. Indeed, the whole question could be dismissed as a distasteful irrelevance were it not for the fact that the charge of being a gypsy seems to have played some part both in Alf’s desire to escape his background and in the whispers against him within the football establishment. Again, Nigel Clarke believes that the issue may have influenced some snobbish elements in the FA against him: ‘Alf had a terrible relationship with Professor Sir Harold Thompson. An Oxford don like that could not stand being lectured by an old Romany like Alf. That’s when he began to move to get his power back and remove Alf’s influence.’

Yet it is likely that much of the talk about Alf’s gypsy connections has been wildly exaggerated, even invented, while the eagerness to turn a childhood nickname into a badge of racial identity seems to have been based on a fundamental error. According to those who actually lived near him, Alf was called ‘Darkie’ simply because of the colour of his thick, glossy black hair. In the 1920s in the south of England, ‘Darkie’ was a common moniker for boys with that hair type. ‘The Ramseys were definitely not of gypsy stock,’ says Alf’s former neighbour Pauline Gosling. ‘That is where that TV documentary got it wrong. I used to call him ‘Uncle Darkie’. Alf got his nickname at school, only because he had very dark hair as a young child. It was nothing at all to do with being a gypsy. I know that for a fact.’ Jean Bixby is of the same view: ‘His brother Cyril and I worked in the office at Fords and he was a quiet, decent chap. I have heard it said that Alf was a gipsy, but to know Cyril, I could not believe it. Cyril did not seem to be from gypsy stock at all.’ Nor did the family’s ownership and farming of the same plot of land in Dagenham for several generations match the usual pattern for travelling people moving from one area to another. In fact, some of the land used for the building of the Becontree Estate around Halbutt Street had originally been owned by Alf’s grandfather and was sold to the council. As Stan Clements, who played with Alf at Southampton in the 1940s, argues. ‘I never thought Alf was a gypsy. I cannot see that at all. When I first met him, his entire appearance was immaculate. And gypsies don’t own land for generations.’ Alf’s widow denied that he was gypsy. ‘That wasn’t true. I don’t know where that came from,’ Lady Victoria has told friends. And Alf himself, when asked about his origins in a BBC interview, snapped, ‘I come from good stock. I have nothing to be ashamed of.’

Yet, despite this protestation, there always lurked within Alf a sense of distaste about his Dagenham upbringing. He went out of his way to avoid the subject and seemed to resent any mention of it. Terry Venables, who also grew up in Dagenham and later was one of Alf’s successors as England manager, experienced this when he was selected for the national side in 1964, as he recalled in his book Football Heroes:

When Alf called me into the England set-up, my dad said to me, ‘Tell him I used to work with Sid down the docks. He was Alf’s neighbour and he’ll remember him.’ It sounded reasonable at the time. Now picture the scene when I turned up for my first senior England squad get-together. For a start, I was in genuine awe of Alf, who came over and shook my hand. ‘How are you?’ he asked. ‘Fine, thank you very much,’ I replied. ‘By the way, my dad says do you remember Sid? He was your next-door neighbour in Dagenham.’ Had I cracked Alf over the head with a baseball bat he could not have looked more gob-smacked. He stared at me for what seemed like a long, long time. He didn’t utter a single word of reply; he simply came out with a sound which if translated into words would have probably read something like, ‘you must be joking’. He must have seen I was embarrassed by this but he certainly did not make it easy for me.

Ted Phillips, the Ipswich striker of Alf’s era, recalls a similar incident when travelling with Alf through London:

We were on the underground, going to catch a train to an away game. And this bloke came up to Alf:

‘Allo boysie, how you getting on?’ He was a real ole cockney. Alf completely ignored him, and the bloke looked a bit offended.

‘I went to bloody school with you. Still on the greyhounds, are ya?’ Alf still said nothing.

When we arrived at Paddington, we got off the tube and were walking through the station when I said to Alf:

‘So who was that then?’

And he replied in that voice of his, ‘I have never seen him before in my life.’

It was the change in Alf’s voice that most graphically reflected his journey away from Dagenham. Terry Venables, like several other footballers from the same area, including Jimmy Greaves and Bobby Moore, always retained the accent of his youth. But Alf dropped his, developing in its place a kind of strangulated parody of a minor public-school housemaster. The new intonation was never convincing, partly because Alf was a shy man, who was without natural articulacy and could be painfully self-conscious in public, and partly because his limited education meant that he lacked a wide vocabulary and a mastery of syntax. Hugh McIlvanney says:

Alf made it hard for some of us to like him because of the shame he seemed to feel about his background. We all understand there can be pressures in those areas but the voice was nothing short of ludicrous. There were some words he could not pronounce and the grammar kept going for a walk. That could be a problem for any human being but, for Alf, it almost became a caricature.

In his gauche attempts to sound authoritative, particularly in front of the cameras or the microphone, Alf would become stilted and awkward, littering statements with platitudes and empty qualifying sub-clauses. One extreme example of this occurred when he was being interviewed on BBC Radio in the early sixties:

‘Are you parents still alive, Mr Ramsey?’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘Where do they live?’

‘In Dagenham, I believe.’

In his 1970 biography, when Ramsey was still England manager, Max Marquis gave a vivid description of Alf’s style. Describing his language as ‘obscure and tautological’, Marquis said that Ramsey

is unable to communicate with any precision what he means because he will never use a single-syllable word when an inappropriate two-syllable word will do and he dots his phrases with some strange, meaningless interjections…His tangled prose, allied with his capacity for self-persuasion, has made for some of his quite baffling pronouncements. In public he lets words go reluctantly through a tightly controlled mouth: his eyes move uneasily.

Because Ramsey never felt in command of his language, he could vary wildly between triteness and controversy. He could be absurdly unemotional, as when Ipswich won the League title in 1962, perhaps the most astonishing and romantic feat in the history of English club football.

‘How do you feel, Mr Ramsey?’ said a breathless BBC reporter, having described him as ‘the architect of this miracle’.

‘I feel fine,’ replied Ramsey, as if he had done nothing more than pour himself a cup of tea.

Yet this was also the man who created a rod for his own back through a series of inflammatory statements, like his notorious description of the 1966 Argentinian team as ‘animals’ or his claim in 1970 that English football had ‘nothing to learn’ from the Brazilians. As Max Marquis put it, ‘Ramsey is like a bad gunner who shoots over or short of the target.’

A serious-minded youth, always striving for some kind of respectability, Alf did not have as strong a working-class accent as some of his contemporaries. Nevertheless, his speech could not help but be influenced by his surroundings. ‘Dagenham had its own special brogue, and Alf spoke with that,’ says Phil Cairns, ‘It was a sort of bastardized cockney. He certainly had that accent as a child. I did notice how his voice changed when he got on in life. It was so obvious. When he had a long conversation, you would hear that he made faux pas.’ Eddie Baily, who was Alf’s closest friend at Spurs, told me of the difference he saw in Alf once he had gone into management with Ipswich Town: