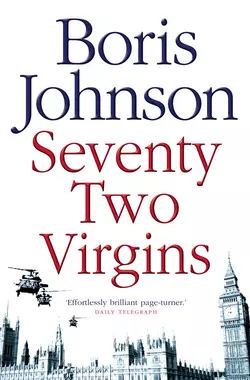

Seventy-Two Virgins

Boris Johnson

Seventy-Two Virgins is a comic political novel, with similar appeal to Stephen Fry or Ben Elton, written by one of Britain's most popular politicians. It is Boris Johnson’s first novel and was widely acclaimed on publication.The American President, on a State Visit to Britain is giving a major address to a top-level audience in Westminster Hall. Ferocious security – with some difficulties in communication – is provided by a joint force of the United States Secret Service and Scotland Yard. The best sharpshooters from both countries are stationed on the roof of the Parliament buildings.Then a stolen ambulance runs into trouble with the Parking Authorities. A hapless Member of Parliament, having mislaid his crucial pass, is barred from Westminster, his bicycle regarded as a potential lethal weapon. And a man going by the name of Jones, although born in Karachi, successfully slips through the barriers, and whole new ball game starts.Despite the united efforts of the finest security minds, events begin to spin out of control. A remarkable new worldwide reality television show dominates the airwaves. And the most unlikely heroes emerge…

BORIS JOHNSON

Seventy-Two Virgins

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_df16ffe8-66e3-54cd-acbe-c2408a88d0fa)

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Boris Johnson 2004

Boris Johnson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007198054

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2016 ISBN: 9780007383504

Version: 2016-04-18

PRAISE FOR SEVENTY-TWO VIRGINS (#ulink_a8ef0916-6797-5cd3-835e-63d317c67159)

‘A hectic comedy thriller … refreshingly unpompous and very funny.’

Mail on Sunday

‘Johnson scores in his comic handling of those most sensitive issues… he succeeds in being charming and sincere … a witty page-turner.’

Observer

‘Among the hilarious scenes of events and the wonderful dialogue which keeps the story moving at a cracking pace, Johnson uncovers some home truths … I can give no higher praise to this book than to say that I lapped it up at a single uproarious sitting.’

Irish Examiner

‘As an author, he is in a class of his own: ebullient, exhausting but irresistible.’

Daily Mail

‘Fluent, funny material … the writing is vintage, Wode-housian Boris … it has been assembled with skill and terrific energy and will lift morale in the soul of many.’

Evening Standard

‘At the centre of his first novel is a terrorist plot of frightening ingenuity … the comedy is reminiscent of Tom Sharpe.’

Sunday Times

‘This is a comic novel, but Johnson is never far away from making serious points, which he leads us towards with admirable stealth.’

Daily Telegraph

‘A splendidly accomplished and gripping first novel … Few authors could get away with it, but this one most certainly does. Highly recommended.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘The rollicking pace and continuous outpouring of comic invention make the book … The guardians of our author’s future need not worry. This is a laurel from a new bush, but certainly a prizewinner.’

Spectator

‘Invents a genre all of his own: a post 9/11 farce … a pacy, knockabout political thriller which takes in would-be terrorists careering through Westminster in a stolen ambulance, a visit from the US president, celebrity chefs, snipers, tabloids chasing extra-curricular … as much fun reading it as Johnson had writing it.’

GQ

‘As well as Mr Johnson’s inside knowledge of Parliament and his exuberantly idiosyncratic prose style, Mr Johnson is also brilliant at characterisation – each one of his cast of hundreds leaps to life in a few sentences … and yes, I laughed out loud approximately every 30 minutes.’

Country Life

DEDICATION (#ulink_4367316b-6ad0-5ba4-81d3-3e5fd067c706)

Optimis parentibus

CONTENTS

Cover (#ucacae23f-4eca-5319-89b8-59b8237c050a)

Title Page (#u6dc558c4-00fc-56ab-a4b8-00f520502a59)

Copyright (#ulink_5e536b68-9b06-550b-8226-455363250d1d)

Praise for Seventy-Two Virgins (#ulink_52d3992c-91e6-5032-9480-5d5d6cecc08d)

Dedication (#ulink_c64c8dfd-8ee0-5c95-97fc-fc22685267b9)

Part One: The Trojan Ambulance (#ulink_d97cdec9-7b2d-5c55-81fe-8b6251c19688)

Chapter One: 0752 Hrs (#ulink_19f55190-7428-57ff-81b2-70925f636602)

Chapter Two: 0824 Hrs (#ulink_2623cdd8-85a8-5662-8b4f-c8b46ffac788)

Chapter Three: 0832 Hrs (#ulink_577a0b02-d41c-5fac-afd9-03c3d313b536)

Chapter Four: 0833 Hrs (#ulink_7268bf98-c740-51c7-86a3-a2a60d173ba9)

Chapter Five: 0835 Hrs (#ulink_aec6d2e1-1912-53ae-8262-7d1266741b47)

Chapter Six: 0837 Hrs (#ulink_651ec640-4fb1-56bf-8cbd-694df93582a1)

Chapter Seven: 0839 Hrs (#ulink_7bf5cc3d-5a80-5d90-b239-4190dc1cf98e)

Chapter Eight: 0841 Hrs (#ulink_d4c4e2d9-530f-5965-af28-6924752cc173)

Chapter Nine: 0843 Hrs (#ulink_d1549738-86ba-54d4-85a3-f9d07c5f0744)

Chapter Ten: 0844 Hrs (#ulink_27303082-1d9c-5d63-9811-44bfa39fd958)

Chapter Eleven: 0845 Hrs (#ulink_8efc2282-5b84-5725-80b8-05703498a3a7)

Chapter Twelve: 0851 Hrs (#ulink_acc802d1-4937-53c5-b003-f5b089bc0e89)

Chapter Thirteen: 0854 Hrs (#ulink_43e63410-eed4-5262-a40b-c19757b19a31)

Chapter Fourteen: 0857 Hrs (#ulink_fbb6aa6b-276f-5187-9206-29c0f3fffa76)

Chapter Fifteen: 0900 Hrs (#ulink_b243d187-fd58-580f-ad38-d60095ece532)

Chapter Sixteen: 0908 Hrs (#ulink_ff8cb2a7-f4a1-5246-a799-b3b7026fd6df)

Chapter Seventeen: 0909 Hrs (#ulink_c666a3e2-fece-5455-a13d-9a6d8945927d)

Chapter Eighteen: 0911 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: 0914 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: 0916 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: 0919 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: 0924 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: 0926 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four: 0935 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five: 0938 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six: 0940 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven: 0942 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight: 0944 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine: 0946 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty: 0958 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: The Special Relationship (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One: 1000 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two: 1007 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three: 1010 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four: 1011 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five: 1021 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: I Come To Bury Caesar (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six: 1024 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven: 1027 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight: 1028 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine: 1030 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty: 1033 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One: 1036 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two: 1037 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three: 1038 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Four: 1040 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Five: 1043 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Six: 1044 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Seven: 1049 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Eight: 1052 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Nine: 1053 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty: 1058 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-One: 1103 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Two: 1105 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Three: 1108 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Four: 1112 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Five: 1114 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Six: 1118 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Seven: 1119 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Eight: 1123 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Nine: 1125 Hrs (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_cf722899-e844-5bb0-b1b3-5dd2acbd88ae)

THE TROJAN AMBULANCE (#ulink_cf722899-e844-5bb0-b1b3-5dd2acbd88ae)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_8f87d9d2-cc2c-545a-92a1-b94b629bf7f8)

0752 HRS (#ulink_8f87d9d2-cc2c-545a-92a1-b94b629bf7f8)

On what he had every reason to believe would be the last day of his undistinguished political career Roger Barlow awoke in a state of sexual excitement and with a gun to his head, the one fading as he became aware of the other.

The gun was equipped with an orange whale harpoon, and would have been lethal, had it been more than six inches long and made of something other than plastic.

‘Say your prayers, buddy,’ said the four-year-old. Roger’s eyelid quivered.

If Sigmund Freud had been able to catch this kid’s conversation, he would have been thrilled. Seldom had there been so exuberant and uninhibited an Oedipus complex.

One morning they were lying all three of them in bed, and Roger was trying to persuade the kid to go and watch Scooby Doo. The child turned to his mother.

He spoke prettily, in the kind of voice he might use for ordering another fish finger.

‘I am going to kill Daddy, and then I am going to marry you.’

Today, Roger didn’t want to be rude to the four-year-old, and he didn’t want to exacerbate his complex, but he was damned if he was going to be treated in this way. He grunted, and rolled away, gripping his slumbering wife with both arms.

The four-year-old fired the plastic dart carefully into the back of Roger’s neck.

Barlow’s blow went wide. Ceding his place to his rival, he rose. He tended to wear T-shirts in bed, and this one was a relic of a brief but illustrious former Tory leadership under which he had been proud to serve.

‘It’s Time For Hague’, proclaimed the T-shirt, while the back announced: ‘The Common Sense Revolution’. As a piece of nightwear, his wife claimed that it had anti-aphrodisiacal properties of a barely credible order.

‘MMM,’ said his wife.

‘Mmm,’ said Roger. ‘Back in a mo.’

As he went into the bathroom he heard the flap of the letterbox. Cee-rist! he thought, the papers …

He scooted downstairs and scooped them up off the mat. Quickly he went through the brutal tabloid that was most likely to have done him in, and then the ones that pretended to be more responsible.

Nope.

Nothing.

Nope. Nothing.

Phew.

Just the usual flammed-up load of old cobblers, masquerading as news.

There was allegedly a ‘dirty bomb’ threat to London, or so said ‘sources’ in the Home Office, with an eye, no doubt, to stirring up public alarm, and then introducing some fresh repression of liberty. There were acres of predictable drivel about the security arrangements for the celebrations today.

The police had launched some Al-Qaeda raid in Wolverhampton and Finsbury. But then there was one of those every month.

In other words, there was nothing important, and certainly nothing to feed his ludicrous paranoia. But some guilty instinct told him to purge the house of these bullying quires of paper.

So he stretched down the Common Sense Revolution to make it a kind of nightshirt (common sense, innit?) and zipped outside into the summer morning. He stuffed them into the fox-ravaged bin, and then checked that no one had seen him.

Drat. Someone had indeed seen him. It was that funny woman who was always muttering under her breath, and who had once seen him administering physical chastisement – in fact it was about the only occasion he had ever done so – to one of his other children.

He beamed at her, tugging the T-shirt over his hips.

With a shudder his neighbour hurried about her business, and Roger darted back up the steps to see the door shutting in his face.

‘Oi. You. No!’ he said.

He bent down to look through the flap.

‘Please,’ he said.

The child’s sweet face came closer. He was now dressed in a red crusader’s tabard, and brandished a plastic gladius or stabbing sword.

‘You are not necessary,’ he said to Roger through the letterbox. ‘Mummy,’ he called, looking back over his shoulder, ‘do we know this man?’

Five minutes later, and with the help of his wife, Roger Barlow had regained access to his house, dressed, washed, and was thrashing around the kitchen looking for that … that thing.

‘You know,’ he said to his wife, ‘the thing with the thing in it.’

His wife had been around long enough to know what to do in these circumstances. She got on with drinking her coffee. ‘Ah yes,’ she said, ‘that thing.’

Barlow cast a worried glance at his watch. It was that green folder thing, the one all about poor Mrs Betts. They were threatening to close the respite centre she needed for her son, who had such severe learning difficulties that he had no realistic hope of education. And last night, in a fit of alcohol-induced elation, he had been staring at the autistic Betts kid’s drawings, which were pretty good, and thought he had seen the answer. But he had had had HAD to have the file.

He was going to ring Mrs Betts that afternoon, and it was no use if he …

Maybe Cameron still had it. He looked again at his watch and wondered whether to dial his beautiful, omnicompetent American researcher. It was too early.

He searched again in his office, under the bed, under the sofa, under the doormat, in the stuff being put out for recycling. He had a sudden horror that he had accidentally thrown the folder away with the papers, and went back to the bins. And then he saw something under his son’s chair, where the child was eating his second breakfast.

He had no time to ask how it had got there. He had no time to speculate on the industrial-strength adhesive with which it was now covered, and which is created by mixing Weetabix with milk.

He had no time because he had a speech to prepare, a respite centre to save, and he had to get to the Commons before the whole of Westminster was blockaded by the Americans.

The President was due to start speaking at 10 a.m., and Roger had to be in his seat in less than an hour. He pointed the bike south and started to churn his legs.

As for the President’s breakfast, it differed from Roger’s in almost every respect. It was a leisured and ruminative repast, taken at a round table in a vast bay window in the same vaulted apartments that have been given to every visiting head of state for the last fifty years.

Olaf of Norway had slept there. So had King Baudouin of Belgium. So had the Pope, and come to that, President Marcos of the Philippines and sundry other thugs the Foreign Office had once thought fit to foist on Her Majesty, notably President Ceaucescu of Romania in 1978 and President Mugabe of Zimbabwe in 1994.

On the bedside table was a guide to the British Museum, a volume of Tennyson and a Dick Francis hardback that might have been new in 1973, when the room was used by President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire.

Now the President looked out over Windsor Great Park, at the ancient oaks, trussed and propped with iron, and the deer, and, in the distance, the looming turrets of Legoland; but what fascinated him most was the yellow packet of breakfast cereal, reposing in a specially constructed silver cruet.

‘Say, honey, look at this,’ he said to the First Lady, and read out the awesome royal warrants. ‘By appointment to Her Majesty the Queen, Weetabix and Co., purveyors of breakfast cereals. And Prince Charles. And the Queen Mum. I thought she passed away.’

‘Gee,’ said the First Lady, who had also been trying to eat the Weetabix. ‘Does that mean they make this stuff specially for the Queen?’

‘I guess she has to sort of approve it.’

‘How much does she have to eat?’ asked the First Lady.

They both stared at their bowls. ‘I dunno,’ said the President. ‘Kind of soaks up the milk, doesn’t it?’

Like Barlow, the President considered the amazing physical properties of a Weetabix/milk solution, and its possible application in the construction industry. The First Lady fleetingly wondered what it would be like to have the Presidential seal on the back of a packet of Froot Loops.

There was a knock on the door.

‘Sir,’ said a US Secret Service man in a blue blazer, ‘Colonel Bluett just called. He wanted to be sure you were aware of the security implications of the arrests last night.’

The President grimaced. He had naturally read the papers, but had been hoping not to bring the subject up in front of his wife.

‘You bet,’ he said. ‘Good job by the Brits.’

‘We should go now, sir, if you’re ready, ma’am.’

‘Too bad they didn’t catch the main guy,’ said the First Lady, who had also read the news.

That wasn’t the only detail troubling Deputy Assistant Commissioner Stephen Purnell, who had been sitting at his desk since 6 a.m. in the New Scotland Yard Ops Room. News had come in of a vehicle theft in Wolverhampton, a crime that appeared to have taken place shortly before the not-quite-successful synchronized raids. It might mean something; it might mean nothing. But it was a very odd thing to steal, and his dilemma, now, was whether or not to share the information with the Americans. After ten days working on this visit with Colonel Bluett of the US Secret Service, he somehow couldn’t face the conversation. ‘Don’t worry, sir,’ said his assistant, who was called Grover. ‘Even if it was our friends who took it, where the hell are they going to park it? I bet someone will find it within an hour.’

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_98da8ed9-b87e-548d-b49b-2cd2cd1f4649)

0824 HRS (#ulink_98da8ed9-b87e-548d-b49b-2cd2cd1f4649)

It was going to be a beautiful day, thought William Eric Kinloch Onyeama, as he walked across Lambeth Bridge.

No. Wait.

He stopped, and his delighted eye scanned the landscape, dapply and wavy and branchy. He could do better than that.

He searched for his new favourite word. It was on the tip of his tongue. He had just confirmed its rough area of meaning with his teachers at the Euro language school in Peckham Rye.

He looked at the happy brown river, winking beneath the bituminous scum.

He looked at the gilt flèches and steeples of the Houses of Parliament, which inspired in him a deep and unfashionable reverence. That building was, in his view, heart-stoppingly lovely, but too spiky, surely, to qualify for the adjective he was now struggling to recall.

He took in the roses in Victoria Tower Gardens, and the red, white and blue flags that flew over the heart of Westminster on this day of glorious commemoration; the white ellipse of the London Eye; the leaves on the plane trees, turning up their light undersides in the breeze.

They were all beautiful, beautiful, but they were not exactly b— What was it again?

He looked down at his shoes, which he had polished the night before. They were fat Doc Martens, burnished and blushing like bumps or buns. They were bu— What was it? They were like the black rumps of the taxis, the bashful bums that beetled before him over the bridge. They were b—; they were bu— they were busty – no, they were buck, they were bucks—

That was it.

It was going to be a buxom day.

He grinned, and thought of all the things that might be classified as buxom.

Obviously there was Mrs (Nellie) Naaotwa Onyeama. She was as buxom as all get out. This he had amply confirmed a little while ago, just before he rose from her bed.

And the clouds above him were high and fleecy. How foolish they were to talk of rain, thought Eric; and how typically gloomy of the Apcoa people to make them take their pacamacs.

If you added it all together, thought Eric, if you looked at all the glitter and lustre and promise of the new summer’s day, then you could argue – and he stood to be corrected – that this July morning stood fully in the semantic field of his new best word.

So he went on down Horseferry Road, past the obelisks with their odd pineapple finials, past the bearded stone Victorians who had conquered the continent from which he came, and he, the colonial, began to hunt in the former imperial metropolis.

He checked the Resparks. He checked the tax. If someone had stuck a ticket in the window, he noted the time of expiry and plotted his return.

All the while he was savouring this language which ruled the world, and over which he was acquiring mastery …

And there in Maunsel Street was his first prey of the morning, buxom in the curvature of its forequarters, a gleaming black four by four which had flouted the Respark and was therefore in defiance of Code 04 and a thoroughly ticketable vehicle.

He reached down for his Sanderson Huskie computer, the wizard device that has given the parkie the whip hand over the motorist. Eric started to record the time, place, and exact dereliction of a Pajero station wagon, licence plate L8 AG41N.

But now a woman was running back down the pavement towards him. She had a kid in tow, with a satchel and a blazer, and she wore an expression of tragic supplication.

‘Oh please,’ she wailed.

She was dressed with terrific chic. She had long blonde hair, dark eyebrows, a tight black T-shirt over a willowy figure and a belt made out of copper plates. It was hard to believe she could be the mother of a ten-year-old.

‘I am very sorry,’ he said and continued to tap.

‘I’ll be literally THREE minutes.’

‘It is not for me to say. It is de rule.’ Eric had caught a glimpse of himself in the smoked Pajero pane, and he knew what she was looking at: six foot two of anthracite handsomeness and power, as richly accoutred with high technology as an American infantryman. He had a smart peaked cap with the cap-badge of the council; he had metallic silver numbers on his epaulettes. He carried a TDS Huskie minicomputer. He had a two-way T8 288 Motorola radio. He had a Radix FP40 printer, ready to discharge his literary efforts, and he was about to print the ticket now.

‘Oh please,’ she said, ‘I’ve got to drop him off at school, and he’s got an exam.’

Eric smiled. ‘What kind of exam?’

‘It’s a maths exam, isn’t it, darling? Oh please, he’s going to be late.’

‘I don’t care,’ said the child.

‘Oh darling.’

Eric approved of maths exams. A cadet branch of Eric’s family had made a great deal of money by scamming arithmetically untalented Europeans, and he was generally in favour of encouraging our children to better themselves.

‘Just one minute,’ wheedled the woman.

The parkie considered. Many traffic wardens are traumatized by the verbals, as they are called, COON, NIGGER, MONKEY, APE.

Those were some of the names Eric had been called, shorn of their participial expletives.

IS THIS YOUR IDEA OF POWER? WHY DON’T YOU GET A BETTER JOB? These were some of the questions he was asked.

Faced with such disgusting behaviour, some traffic wardens respond with a merciless taciturnity. The louder the rant of the traffic offenders, the more acute are the wardens’ feelings of pleasure that they, the stakeless, the outcasts, the niggers, are a valued part of the empire of law, and in a position to chastise the arrogance and selfishness of the indigenous people.

Eric was unusual in that he liked sometimes – every once in a while – to show mercy, as befitted his kingly lineage. The scars on his cheeks denoted that he was a prince of the royal blood in the Hausa tribe, and it was only the evil of primogeniture that debarred him from substantial estates outside Lagos.

Sometimes he would exercise clemency, if he were offered a really rococo excuse, as a bored tutor will indulge a crapulous undergraduate if his reason for missing a class is truly bizarre and degenerate. Sometimes, as today, he could be moved by the appeal of a damn good-looking woman. But today he had a peculiar reason of his own for not wanting to prolong the conversation.

The night before Mrs Onyeama had been very good to him. She had made him his favourite meal, a chicken Kiev with a kind of special West African garlic called kulu, rather like the North American ramps, and he had slept well on it. But he knew from experience that Mrs Onyeama’s chicken Kievs had an amazing effect on the digestive system. There was nothing normally detectable, but from time to time the kraken would wake, and then a globule of air would force itself up the oesophagus and press on the palate … until he was obliged to let it go.

It had happened to him at a wedding party recently. He had been telling a joke, and he came to the punchline, and everyone was crowded around him, like maternity unit staff, waiting for the birth of the joke, and he had suddenly felt – whup – this thing come out of him, involuntarily, rather like the thing in Alien coming out of John Hurt. His audience had reacted in much the same way as the characters in the movie.

So he beamed at her, without a word.

‘Mmm-hmmm,’ he murmured, and put down the Huskie.

‘Really?’ She couldn’t believe it.

‘Mmmmbmm.’

She gushed her thanks and was gone. And it was therefore with a faint sense of a hunter-gatherer who has missed one easy kill that he turned into Tufton Street, for the second time that morning.

He could hardly believe his eyes. It was still there.

It was the big one, el gordo. This was the white whale, and he was Ahab.

It had been there, to his certain knowledge, for half an hour, and probably far longer. The ambulance was on a single yellow. That was a Code 01 offence, and it was on the footway – that was Code 62. But what made it a légitimate target, in Eric’s view, was that it was blocking the thoroughfare, in the sense that two cars could certainly not pass abreast.

It was not true – as the tabloids hinted – that he received a bounty for every car he successfully caused to be plucked from the streets. But it certainly was true that he received bonuses for ‘productivity’, and productivity was measured – well, how else could it be measured?

Eric and Naaotwa Onyeama were ambitious for their children, and on the televised urgings of Carol Vorderman they were currently investing in a series of expensive ‘Kumon’ maths text books. Since Eric Onyeama only made £340 per week, working from 8.30 a.m. to 6.30 p.m., this was not an opportunity he could responsibly pass up.

He reached for his Motorola and summoned the clampers. Then, since there could be no question of the vehicle staying where it was, he rang the tow-truck company.

Hee hee hee, chortled Eric, and he laughed at the multiple pleasures of the morning.

He knew all the tow-truck men, and Dragan Panic, the Serb, was the hungriest of the lot. Unless the mysterious crew of this ambulance returned within five minutes, the vehicle was a goner.

In the Tivoli café on the corner of Great Peter Street and Marsham Street three men and a kid of about nineteen were coming to the end of breakfast. The restaurant was non-posh to the point of affectation. Up the nostrils of its diners rose the tang of vinegar, mothering in its bottle, mingling with the ammoniacal vapours that hummed from the cloth that was used to wipe the Formica.

But the four dark customers had done well. They had eaten a meal of Henrician proportions: eggs, beans, chips, chops, schnitzels, steaks. The proprietor was amazed, especially considering it was not yet nine in the morning.

They had swallowed draughts of milkless tea, turned into a kind of sugary quicksand, and then they had eaten the Danish pastry and the doughnuts, ancient thickly iced things that had been in the display so long he had feared he would have to reduce the price.

They had eaten, in fact, as if there were no tomorrow; but today their mortal frames required relief. Owing to their eccentric bivouac they had been unable to pass water all night.

‘Quickly,’ said the one called Jones, coming back from the toilets. ‘The traffic wardens will be here.’ There was certainly something lilting and eastern about his accent; but if you shut your eyes and ignored his brown skin, there were tonic effects – birdlike variations in pitch – that were positively Welsh.

‘I must go too,’ said one of his colleagues, who had a moustache.

‘Well, hurry, God help us.’

Haroun scowled. It was obviously inequitable for their leader so to privilege his own requirements, but no doubt he was under pressure.

‘Sir, please can I go?’

It was the kid. ‘Quickly, Dean,’ said the man called Jones.

There was only one toilet, identified by a pictogram on the door, of a Regency buck and a crinolined dame, to show it was for the use of both sexes, and by an unspoken agreement Dean went in first.

Full though his bladder was after a night of appalling discomfort on a stretcher in that airless vehicle, he found he was trembling too much.

‘What is going on?’ hissed the man called Jones.

‘What are you doing in there?’ Haroun banged on the door and Dean felt that any hope of micturition was gone. He respected Jones, but he was seriously frightened of Haroun, who had the pale blue eyes and tiny black pupils of a staring seagull.

Jones saw a traffic warden pass the window. Their researches had already established that the wardens around here were sticklers, and he had a sense of impending disaster.

He ran out and round the corner. He stood still. He shut his eyes. He clenched his fists.

‘Nooo,’ he called. ‘Stop it, you!’

Already a clamp had appeared on the right-hand front wheel of the ambulance, a green clamp, moronic, infernal. He swore in Arabic.

Hmar. Jackass.

Yebnen kelp. Son of a bitch.

Hee hee hee, chortled Eric Onyeama.

Jones ran back into the Tivoli and rounded up his men. By now only Haroun had failed to make use of the facilities.

‘Come,’ said Jones.

‘I must just go …’ said Haroun, but such was the power of Jones, and so contemptuous was the expression in his eyes that Haroun followed him like a lamb and Jones ran back into the sunlight.

And now he couldn’t believe it … He couldn’t flipping well believe it. Surely he had been gone only seconds, and now the clamp had gone but the ambulance was being hoisted up into a kind of hammock by a hydraulic lift, and the parkie was standing there, still scribing zealously away into his Huskie computer.

‘I am sorry, sir,’ recited Eric, ‘but once all four wheels are off the ground, you have lost control of the vehicle. It is now the responsibility of Westminster City Council.’

Jones waved the keys. ‘But it is ours. Put it down.’

‘All the craps are on,’ said Eric.

‘The craps?’

‘Yessir, these are the craps. The metal craps.’

‘You mean the crabs.’

‘That is right, sir, they are the craps.’

Jones gave up. ‘Did you say all four wheels?’

‘Yes, that is correct, sir. Now that all four wheels are off the ground, it is the law that you no longer have any control over this vehicle.’

This was a big ambulance. Fully laden it weighed not far short of three and a half tonnes, with a 3.5 litre Rover V8 engine and bulky aluminium chassis, so that it was already astonishing that the tow-truck had been able to hoist it.

At that moment Jones had an inspiration. It was technically true that the wheels were off the ground. But the front pair were only a few inches up.

‘What about now?’ asked Jones. He and Haroun jumped on the bonnet of the Leyland Daf vehicle, painted with a blue star and caduceus, and it sunk its nose until the front offside wheel brushed the ground.

‘See!’ shouted Jones. ‘Now it is ours again!’

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_70dcdf1b-f51c-55e2-8b78-aca8407edff3)

0832 HRS (#ulink_70dcdf1b-f51c-55e2-8b78-aca8407edff3)

‘Whose ambulance did you say it was?’ asked Deputy Assistant Commissioner Purnell, who was, today, in charge of anti-terrorist and security operations throughout the Metropolis.

Grover entered the room with an air of satisfaction. ‘What did I tell you? We’ve got it. An ambulance from the Bilston and Willenhall NHS Trust was seen at the Travelodge in Dunstable at one a.m.’

‘Good. And it’s still there, is it?’

‘Er, no. It left.’

‘Aha.’

‘We’re on the case.’

A second later, he was back again. ‘I’ve got Bluett on the line.’

The two London policemen looked at each other. They knew – or strongly suspected – that the Americans were tuning in to their frequencies.

‘Put him through,’ said Deputy Assistant Commissioner Purnell.

He listened with half-closed eyes to the American’s demands.

‘You want a sniper on the roof of the Commons? What did you say his name was?’ On a piece of headed notepaper Purnell printed ‘PICKLE’. Then he crossed it out and wrote ‘PICKEL’.

‘I see, yes,’ he said, ‘I see, yes.’

He listened some more, and then said: ‘Well, I can understand if the First Lady is a bit anxious but … Right you are. Colonel … Okeycokey, chum. Yep. See you later, I expect … No, no, everything else is, um, fine. We have no evidence of anything, you know, untoward.’

He disconnected with a groan.

‘They want a sniper on the roof of the Commons, above New Palace Yard. I’ve said we’ll oblige. Someone answering to this name will be presenting himself in a few minutes. Whatever happens, I am not having him sitting up there alone.’

He handed over the sheet of paper. ‘And I want the choppers to start scanning Westminster for this flaming ambulance.’

High above Soho a Metropolitan Police Twin Squirrel Eurocopter AS 355N banked and turned down Shaftesbury Avenue.

It passed directly over the head of Roger Barlow, who looked up and felt vaguely resentful. Why did they hover in that threatening way over innocent streets? It was like some dreary lefty movie about Thatcher’s Britain.

Then he continued to thread his way through the cars. That’s what he loved about bicycles: the autonomy, the ability to put your wheel wherever you chose. As you looked over the handlebars you could see your front tyre as a snub-nosed cylinder, nosing at will down the open streets of London. He passed an Evening Standard hoarding, announcing full coverage of the state visit.

Uh-oh. The Standard. He had forgotten about the Standard. How would he stop his wife seeing that one?

The traffic was getting heavier. Now he understood. It was the exclusion zone. The American security people had insisted on a total ban on traffic in the area to be honoured by their presence, and the result was that a freeborn Englishman could not even move down the Queen’s highway.

‘Strewth,’ he cursed, and used a disabled ramp to mount the pavement. He knew he shouldn’t do it, but there you go. In any case, his political career might be over by tomorrow morning.

Then he was back on the road again, watching the shimmer starting to rise from the hot bonnets of the backed-up traffic, and thugga thugga whok whok the helicopter was ceasing to impinge on his consciousness.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_0cb347e1-f2fc-55e4-923c-3f484281ef17)

0833 HRS (#ulink_0cb347e1-f2fc-55e4-923c-3f484281ef17)

In the Twin Squirrel Eurocopter the two sun-goggled officers peered into the hot canyons and smoking wadis of the city. ‘So who’s meant to be driving this ambulance?’ said the pilot, as they passed over Trafalgar Square and made for the river. ‘He’s called Jones,’ said Grover from New Scotland Yard.

‘Jones? What’s he look like?’

‘Kind of Arab-type thing.’

Hundreds of miles away, at Fylingdales in Yorkshire, the word Arab triggered an automatic alert in the huge golfball-shaped American listening post, and within seconds the conversation was being monitored in Langley, Virginia.

The pilot continued: ‘That’s all we know: that he’s a kind of Arab called Jones?’

‘That, and he’s on the CIA’s most wanted list. His father was a gynaecologist in Karachi who was struck off for some reason. He knows a lot about explosives and is a serious wacko. That’s what we know about Jones …’

Who at that moment was sliding with Haroun off the bonnet of the ambulance and on to Tufton Street, as the vehicle was jerked up into the air.

Dragan Panic was standing by his Renault 150 authorized removal unit, twiddling the vertical line of six hydraulic knobs, and grinning. It was always fun when they went doolally.

One chap had leapt aboard his Porsche Cayenne, manacled to the truck, and put it into reverse.

He took it up to about 7,000 revs, smoke pouring everywhere, as the Bavarian beast struggled to escape the gin. There had been a bang and a fresh convexity appeared in the gleaming black bonnet, like a rat in a rubbish sack. That HAD been gratifying.

Jones decided to take a different tack with the traffic warden. He made the obvious point.

‘But we are ambulance men.’

The parkie looked at him.

That was just it. He had watched the vehicle like a tethered goat. He had seen the men get out, leaving it parked in a disgracefully dangerous position.

He had seen them shamble into the Tivoli for breakfast. He didn’t believe for one minute that they were ambulance men. They were the first ambulance men he had ever seen in scruffy old T-shirts and jeans, and he didn’t see why they should be in possession of an ambulance belonging to the Bilston and Willenhall NHS Trust.

‘Please, let us pay now.’

‘No, you must come to the pound.’

‘Why?’

‘You must establish that the vehicle is yours.’

‘But I have lost the papers.’

‘Then you must come to the pound.’

The man called Jones went to the cabin of the ambulance and rootled in the glove box. He came back with a brick of cash, like the wodge the winner has at the end of a game of Monopoly, or what you get for a fiver in Zimbabwean dollars. Eric frowned and pretended to study his Huskie.

‘Please do not force me to beg,’ said Jones.

‘I ain’t forcing you to beg, sir.’

‘My sister is pregnant.’

With every second that passed, Eric was surer that he had done the right thing. Now if they had said that they were taking the Duke of Edinburgh on a secret assignation with a nurse from St Thomas’s hospital, that would have been one thing.

If they had said that they had a freshly excised human liver on board, and that it needed to be transferred in ten minutes to a terminally alcoholic football player, or if they had claimed to be part of Scotland Yard’s counter-terrorist unit, they would have appealed to his imagination.

But to say that his sister was pregnant – that was sorry stuff. He looked at the four of them. He noticed that the youngest one was staring at him in a funny way, as if terrified.

Am I really so frightening? wondered Eric Onyeama, king of the kerb. He continued to tap into the Huskie.

‘L64896P’, ‘Tufton Street’, ‘02, 62’ … The details were soon pinged into space, and stored in irrefutable perpetuity in the Apcoa computers. Somewhere in cyberspace the electronic data began to team up with other groups of electrons; in less than half a second they were having a vast symposium of sub-atomic particles, and among the preliminary conclusions would be that the vehicle was from Wolverhampton.

He looked up again, and saw the kindlier-looking one, Habib, who was cleaning his teeth with a carved juniper twig. But where was the other one?

Haroun had vanished.

He had stolen inside the machine and he was searching for something.

He knocked aside a cervical collar-set. He brushed a mouth-to-mouth ventilator to the floor. Ha, he thought to himself. This would unquestionably do the job, he decided. He extracted the prong of a pericardial puncture kit, and tested its needle point on his finger.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_7171b758-d38a-5f16-bf06-b20f76046dc2)

0835 HRS (#ulink_7171b758-d38a-5f16-bf06-b20f76046dc2)

‘Looks like a killer,’ said Purnell. He gave a small shudder as he looked at the file on Haroun Abu Zahra, a slim docket. ‘What do we know about him?’

‘Not a lot,’ said Grover, ‘but the Yanks are pretty keen on talking to him as well. There is one thing, though.’ He paused, as all subordinates will when they are keen to emphasize some tiny advance.

‘Our lads were talking to the Travelodge, and they said there was something most peculiar about their room.’

‘After they’d left?’

‘Yeah. There’s a picture by some posh artist on the wall, of a naked girl, you know, a print.’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘Tits out, very tasteful and all.’

‘Go on.’

‘And they had turned it to the wall. Twenty minutes later they checked out.’

‘Wackos.’

The phone went in the outer room. They both knew it was Bluett.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Purnell looked at the clock on the wall.

‘They’ll be on their way, won’t they?’

‘No way of stopping them now,’ said Grover.

No fewer than fifteen BMW 750 police motorcycles were engaged in sheepdogging the traffic out of the way of the slowly oncoming cavalcade.

Now they were approaching Junction 4 for West Drayton and Heathrow, and seeing the signs the President looked over to his right.

He tried to spot the two Boeing 747-700s, painted in the eggshell blue livery of the President of the United States; but no sign. Perhaps they had been tactfully concealed in a hangar.

After the airport the wailing host of outriders and motorbike voortrekkers took the red route that runs from Heathrow to London. They shovelled the taxis aside and cowed the cursing commuters.

One woman tried to see into the tint-windowed limos and crashed her Nissan Micra into the back of an expensive but vulnerable Alfa 164. The ensuing delay added an average of fifteen minutes to the journeys of more than 1,000 motorists.

As the traffic thickened down the Charing Cross Road, it occurred to Roger that this security business would be no joke. What if he couldn’t even get into his office?

Cameron. That was the answer.

Cameron would have all the passes necessary.

He reached into his breast pocket for his mobile, since he was all in favour of using his bike as his office.

Damn. Oh yes. He’d thrown it away the other day when it rang at the wrong moment. Straight out of the car window, as it happened, on the M25, landing safely in some buddleias in the central reservation.

He negotiated the Palio of Trafalgar Square and howled round into Whitehall. And here it was.

A fence. Ribbons of aluminium fences, and policemen in fluorescent yellow, sprouting like dandelions in the grey of the stone and the tarmac, and the whok-whok-whok of a helicopter in the distance.

‘I’m sorry, sir, you’ll have to dismount.’

‘But I’m a Member of Parliament.’

The policeman looked at him with open disgust.

‘I don’t care if you’re the Queen of Sheba, sir.’

And so it went on as Roger was shunted in a ludicrous arc westwards of the place to which his electors had sent him. Every time he attempted to penetrate the cordon of fencing he was sent off again in search of some mythical entry point.

‘I’m sorry, sir, you can’t take your bike through here.’

At one point, to his shame, he snapped at the men in blue.

‘What’s wrong with my bike?’

‘It’s a lethal weapon, sir.’

‘You can say that again. It’s almost killed me several times.’

‘Now don’t try to be funny, sir. I’ve seen these things packed with explosives. I’ve seen what they can do. Look, I know it’s annoying, sir,’ said the copper, seeing his expression, ‘but please try to bear with us. We’re all doing our best, but the whole caboodle has been agreed with the Americans.’

And so Roger Barlow tacked ever round and west, until he found himself in Pimlico and puffing up Tufton Street.

Where he saw Dragan Panic standing by the tiplift of his Renault 150, heaving some large white vehicle aboard.

‘Come on, droogie moi, come on, my friend,’ said Dragan to himself in Serbo-Croat.

In theory the Renault could lift 4,450 kilos, but the hydraulics were puffing a bit and the stabilizing rods were biting into the tarmac the way a heart attack victim clutches his chest.

Dragan wanted to take this bleeding ambulance, and then he wanted to scarper. Personally, he thought Eric the parkie was mad.

OK, so it was dangerously parked. But you didn’t lift an ambulance. Nah, not an ambulance. Since fleeing Pristina in 1999 Dragan had slotted in nicely in the East End. His knuckles were richly scabbed and crusted with doubloons, and he dressed in trackie bums. At Christmas he sold Christmas trees on the street corner, thumping his mittened hands together. He did a bit of gamekeeping for some toffs out in Essex, place called Rayleigh, and he did like a high bird.

But lifting an ambulance – well, it was like shooting a white pheasant, wasn’t it? He wasn’t on for that. And above all he didn’t like being in the company of Muslims. That wasn’t just because he was a Serb killer from Pristina, and a former member of Arkan’s Tigers.

It was also because he was as big a coward as ever set fire to a Muslim hayrick in the dark, and experience had taught him that you had to keep an eye on the sneaky bastards. Speaking of which …

A couple of them seemed to have vanished. Now there was just the young kid and the spooky-looking fellow, and the parkie taking his time.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_913a37a5-f4b1-5586-af2f-897a07c9090d)

0837 HRS (#ulink_913a37a5-f4b1-5586-af2f-897a07c9090d)

Eric Onyeama was struggling with the urge not to burp.

This man was rude, and Eric had to maintain his poise and dignity. It was impossible to do this while burping.

‘Please … Oh you bastard,’ said the man called Jones. ‘Just do what I say or I’ll …’

‘I must warn you that it is the policy of our company to take legal action against anybody who uses the verbal or physical ab—’

As when scuba divers find a pocket of stale air in a sunken submarine, and the bubble rises to the surface in a distended globule, so the garlic vapours were released from Eric’s stomach.

‘Abuu—’

They passed in a gaseous bolus through his oesophagus, and slid out invisibly through the barrier of his teeth.

‘Abuse,’ he said, and a look of mystification, and then horror passed over the face of the man called Jones. He staggered back.

Ah yes, thought Roger Barlow, a classic scene of our modern vibrant multicultural society, a group of asylum seekers in dispute with a Nigerian traffic warden.

Poor bleeders, he thought. What were they? Albanians, Kosovars, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Martians? Now their day was wrecked. They would have to find the thick end of £200 just to spring their motor. How many windscreens would they have to wash to earn that back?

He composed a sorrowful speech in his head, to the effect that the law was cruel, but that its essence was impartiality. Hang about, he said to himself as he drew nearer. That’s bonkers. They can’t take an ambulance.

Barlow rescues ambulance, he said to himself reflexively. Have-a-go hero MP in mercy dash. ‘I couldn’t believe my eyes,’ said Mr Barlow last night. The Mail asks: Has the world gone mad? He was thinking Newsroom Southeast, he was thinking Littlejohn. He was thinking Big Stuff. Well, this was a story, all right. That should get that awful Debbie woman off his back.

He saw the traffic warden say something to the olive-skinned man, and the olive-skinned man reeled; and no wonder he reeled, poor dutiful fellow. He could imagine that they were already late for a mission.

Across London, the mere act of getting up was taking a terrible toll. People were braining themselves in the shower, slicing their nostrils with Bic razors, brushing their teeth with their children’s poisonous Quinoderm acne cream, sustaining cardiac infarcts at finding themselves misreported in the paper – and where was the ambulance?

It was outrageous! Roger braked and spoke in the mellow bedside tones of the MP’s surgery.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_0ee77809-f46a-54fe-9070-dce758f7167f)

0839 HRS (#ulink_0ee77809-f46a-54fe-9070-dce758f7167f)

‘Excuse me. I wonder if I can help.’

The traffic warden smiled bashfully. ‘It’s OK, sir, we do not need any help here. De law is de law.’

‘I know it’s none of my business, but are you seriously going to remove that ambulance?’

‘Please, sir, do not get involved. I cannot make de rules. I can only enfoooo – oo excuse me, I can only enforce them.’

Barlow blinked as he was engulfed. ‘But this is absurd,’ he said, turning to the victims. ‘I know this shouldn’t make any difference,’ he said superbly, ‘but I am an MP.’

For the first time the olive-skinned man faced the MP. His passport said his name was Jones, and that he had been born in Mold, Clwyd. Though it was true that he was currently a student at an institution implausibly called Llangollen University, these biographical details seemed unlikely.

Roger Barlow noticed something about his eyes. They had a kind of wobble. It was as though he was watching a very close-up game of ping-pong.

‘Piss off,’ he said. ‘Piss off and die.’

‘Eh?’ Barlow gasped.

‘Not necessarily in that order,’ said Jones.

Barlow looked for guidance to the warden. There was something badly out of whack here. When all was said and done, were they not, he and the warden, part of the same team?

He made the law, the warden enforced it. They were like two china dogs, bracketing the sacred texts of statute.

‘I’m sorry … ?’ he said, pathetically.

Tee hee hee, sniggered Eric Onyeama, and shook his head at the busybody. He felt sure he had seen dis man before, maybe in church, or at a meeting of parents and teachers. But if Roger was looking for an ally now, he was out of luck.

‘De man is right,’ he said. ‘You must go away.’ And Roger did. For once he felt he could have made a difference. He could have improved things here. He cycled on. Was it getting hotter, or was that the sweat of embarrassment?

That man told me to piss off, he told himself. And die, too. He wondered whether anyone had seen his humiliation.

Had Barlow not been so mortified, he might have seen Haroun issue from the side of the van and pass something to Jones. The leader of the gang of four now looked at his watch and decided it was time to bring matters to a close.

‘Please be so kind as to put the ambulance down now, and stop this damnfoolery.’

Hey dere, said Eric to himself. The Huskie was chirruping back to him.

I knew it, he thought. The ambulance had been reported stolen last night, from Dymock Street, Wolverhampton.

‘Did you hear what I said?’ Jones’s voice had an evil snit to it.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Eric, thinking fast, ‘but you must come with me to the pound.’

‘I’m going to ask you one last time: give us back our vehicle.’

‘You have broken de law.’

‘No,’ sneered Jones: ‘you broke de fucking law. You lifted the thing off the ground while we were here.’

‘I am sorry, but that is wrong.’

‘You IDIOT! Tell him to put the ambulance down. Tell him to do it now.’

In defence of its parking attendants, men and women who must put up with some of the worst abuse known to this coarsened, selfish and irresponsible age, Westminster Council gives them cameras.

These are used not just to record the offence, but also to deter the protesting traffic offender just as he is about to bust a blood vessel or commit a common assault. Now Eric took out his Sony DSU-30 digital camera, and left the Huskie hanging by his neck. As he was doing this Haroun was creeping unseen up the side of the tow-truck.

In his hand he held a nasty-looking piece of medical equipment which was, did he but know it, a thorax draining kit. The man called Jones began to swear – never a good sign for those who had dealings with this horrid person.

‘Omak zanya fee erd.’ Your mother committed adultery with a donkey.

‘I am sorry?’ beamed Eric, who had decided to call the police.

‘Yen ‘aal deen ommak!’ barked Jones. Damn your mother’s rooster – a deadlier insult than you might think, if only to an Arab.

‘What for do you need an ambulance anyway?’ asked Eric, and he took a couple of quick shots of Jones: billhook nose, grubby neck, short grey-flecked hair and peculiar eyes.

‘It is for the disabled,’ said Jones.

‘Who are the disabled?’

Haroun tiptoed round the front of the Renault and prepared to lunge at Dragan Panic.

‘I don’t see a disabled person anywhere,’ repeated Eric. ‘Show me the disabled person.’

‘Here is the disabled person,’ said Jones.

‘Where?’

‘Here.’

The last noise Eric heard before he fainted with shock was the ripping of his own pericardium as it was punctured by the pericardial puncture unit. Then there was a scraping noise as the spike hit something hard that might have been bone.

‘Help me,’ shouted Jones to Dean, the nineteen-year-old, as he caught the falling warden.

Dean watched, mouth agape, as his boss buckled under the weight; and then leapt forward to help him arrange the traffic warden in the gutter.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_c6e1ed41-8c7b-54d8-9f7f-2d2a91fdefa1)

0841 HRS (#ulink_c6e1ed41-8c7b-54d8-9f7f-2d2a91fdefa1)

Dragan the Serb had been weaned on tales of heroic assassination and glorious betrayal. From the Battle of Kosovo Pole onwards, Serbs have learned to glory in a sense of victimhood. But today he decided to give the national myth a miss.

He pushed away Haroun and his spike, and thudded off, weaving and shoulders hunched, as though with every yard he expected a bullet in his back from the Kosovo Liberation Army.

He sprinted from the Muslim extremists, down Tufton Street, past the (former) Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, founded in 1701, and turned on to Great Peter Street. He weaved one way, he ducked the other.

Haroun watched him go.

‘Leave him,’ called Jones. ‘We have no time.’

Dean already felt he had good reason to be admiring of Jones, but he was amazed at the self-possession with which his boss now began to unload the ambulance from the tow-truck.

‘Whoa,’ he called, as the telescopic arm of the crane jerked into life, and the vehicle was thrust out into the street.

The arm was powered by three separate hydraulic lifts, the first capable of carrying 2,500 kilos, the second 1,700 kilos and the third 1,300 kilos; and in theory they were well capable of lifting a three-and-a-half-tonne ambulance.

But Jones was in such a hurry that he neglected the basic laws of physics.

‘Hey!’ said Dean, as the white machine was swung out over the street, like some mad mediaeval siege engine.

Haroun gave a curse – something nasty about a dog. Dean guessed – and even Habib broke off from flossing with his juniper twig.

‘Yow need to come back a bit,’ shouted Dean over the roar of the Renault engine.

The front wheels of the tow-truck were now on the verge of leaving the ground; black smoke was coming from the exhaust; the whole thing was about to keel over, and Dean instinctively ran to drag the body of Eric the warden out of the way.

‘It is fine, it is fine,’ shouted Jones, and flipped the next toggle, so that their stolen machine crashed back towards them and bust a taillight on the bed of the tow-truck.

‘Do it like this,’ called Habib quietly in Arabic. Habib was also called Freddie, and came from a good Lebanese family. He was a Takfiri, a man who masked the ferocity of his faith with a sympathetic worldliness; and he had spent enough time in gambling houses to understand the principles of the grabby machines you use to pick up a watch or a fluffy toy.

Together, and with what Dean thought was remarkable coolness, he and Jones worked out how to ease in the last extender arm and, in hydraulic pants, the van was lowered to the ground.

With the speed of Formula One pitstopmen they now undid the metal crabs and hessian straps, bunged them on the back of the tow-truck, and loaded poor Eric in the back of the ambulance.

Haroun paused only to read the sign on the side of the Renault.

‘How ees my driving?’ he said, and laughed, a horrible carking yelp.

It says something for the tranquillity that has descended on the Church of England that no one else observed these events outside Church House.

No one took any notice of them as they drove in full conformity with the laws of the road – apart from the taillight – in the direction of the Palace of Westminster.

They began thereby to catch up with Roger Barlow, who was waiting with his bike at a red traffic light, as all good lawmakers must.

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_834f2abd-c99c-527e-8e49-5b10bdd459be)

0843 HRS (#ulink_834f2abd-c99c-527e-8e49-5b10bdd459be)

Barlow’s thoughts of political extinction had taken a philosophical turn. Did it matter? Of course not. The fate of the human race was hardly affected. The sun would still, at the appointed date four billion years hence, expand to the girth of a red giant and devour the planet. In the great scheme of things his extermination was about as important as the accidental squashing of a snail. The trouble was that until that happy day when he was reincarnated as a louse or a baked bean, he didn’t know how he was going to explain the idiotic behaviour of his brief human avatar.

It wasn’t the sex comedy side of things. It wasn’t the waste of money, the cash that should have gone into Weetabix and plastic guns for shooting him in bed.

It was the gullibility – that was what worried him.

Should he wait for the papers to present this appalling Hieronymus Bosch version of his life? Or should he try to give his account first, and thereby win points for frankness?

Hang on a tick: there was a colleague. Swishing down the pavement, hair cut by Trumpers, suit cut by Savile Row – it was Adrian (Ziggy) Roberts. Bright. Forceful. Decisive. Very far from completely unbearable; in fact, by any standards really rather nice.

Roger conceived a desire to talk to him, not least because he could see under his arm the early edition of the Evening Standard.

‘Ziggy, old man,’ called Roger Barlow, kerb-crawling on his bike.

‘Hombre!’ replied Ziggy.

‘You going to this Westminster Hall business?’

‘God no,’ said Ziggy, who had benefited from the most expensive education England can provide. ‘Can’t be arsed.’

Roger felt welling up in himself the urge to confide in a friend. A problem shared, he whispered to himself, is a problem halved.

‘Can I ask you something, Zigs?’

‘Of course.’

Roger looked at his colleague, his high, clear forehead, his myriad certainties. On second thoughts, no.

Ziggy counted as a friend, but it was, in the end, your friends who did you in. And quite right, too. That was what friends were for.

‘That posh suit,’ said Barlow. ‘Just tell me roughly how much.’ But Ziggy’s answer was lost in the noise of the Twin Squirrel Eurocopter. Blimey, thought Barlow: this was worse than the helicopter paranoia scene in Goodfellas.

‘Wait a sec,’ said the co-pilot of the chopper, as they bullocked over towards the Embankment. He craned backwards the way they had come, and the City of Westminster – touching in its majesty – was reflected in the black visor of his helmet.

‘I just realized …’

‘Say again?’ yodelled the pilot into the mike on his chin.

‘I think we just flew over it. It was on a tow-truck. I didn’t really take it in …’

‘On a tow-truck?’

‘Yeah, you know, a council truck.’

‘Bollocks,’ said the pilot. ‘No one lifts an ambulance.’

‘Go on, it’ll take thirty seconds. Just back there in that little street near Marsham Street.’

The pilot sighed and turned the joystick. ‘Well,’ he said a little later. ‘There’s your tow-truck, but I don’t see any ambulance.’

The co-pilot stared. It may have been unusual for an ambulance to be hoisted, but it was positively unheard of for a vehicle of any kind to escape the clutches of a tow-truck operator.

‘Where’s the driver, anyway?’ he asked himself.

Here, thought Dragan Panic. Down here! Look this way!

For a couple of seconds he jumped up and down, waving and staring at the police helicopter until his eyeballs began to ache from the glare.

No use. They couldn’t see him.

Dragan had a pretty good idea what he had witnessed: the shambolic beginning of something that might end with eternal loss and heartache for thousands of families. He had read about the idiotic punch-up outside Boston’s Logan Airport on the morning of 9/11 itself, when the Islamic headcases left their maps and their Koran and their flight manuals in the stolen hire car. But mere incompetence was no guarantee of failure, as he knew from his own soldiering.

Dragan looked down towards Marsham Street. He saw a building site; he saw men in yellow hats and muddy boots. Tough men, who could help.

He was older and fatter than he had been as a purple-pyjamaed Serb MUP man, and he was soaked with sweat; and though he had absolutely no reason to love the United States, not after what they had done to Serbia, he stamped and grunted as fast as his Reeboks would carry him.

‘Hey!’ he shouted. ‘Help, please!’

Dark faces looked up.

Dragan put his hands on his knees in exhaustion, and began to explain to the immigrant builders that there was a plot against America.

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_14114879-cd0e-557d-afcf-794a54d1c306)

0844 HRS (#ulink_14114879-cd0e-557d-afcf-794a54d1c306)

‘I’m starting to think we should warn the Yanks,’ said Deputy Assistant Commissioner Purnell.

‘You mean about the ambulance?’ said Grover. ‘What makes you think they don’t know already?’

But when Purnell came to dial Bluett he once again found himself changing his mind. Why raise the temperature?

He cleared his throat when Bluett picked up, and was on the point of improvising some excuse when the American cut in.

‘Mr Deputy Commissioner, we have a problem.’

‘Oh yes,’ said Purnell, ‘I know. I mean, what problem?’

‘We got reports of helicopter activity right over the cavalcade route, and the Black Hawk needs to go that way.’

‘…’ said Purnell.

‘We need that Black Hawk in the aerial vicinity at all times, and neither of us wants a mid-air collision.’

Purnell found his eyes closing, and he listened some more.

‘Unbelievable,’ he told Grover, when the conversation was over. ‘We’ve got just over an hour till the President starts speaking, and the Americans are fussing about the French Ambassador’s girlfriend. They say they don’t want her in the hall.

‘And tell the boys in the chopper to clear out of the way, would you?’

The trouble with today, thought Purnell, was that if something did go wrong, no one could say they hadn’t been warned.

BOMB SCARE HITS LONDON read Roger Barlow, continuing to steal shifty looks at Ziggy’s Standard; and then page after page about the state visit.

Of course there was nothing about him. He felt like laughing at his own egocentricity.

There was something prurient about the way he wanted to read about his own destruction, just as there was something weird about the way he had been impelled down the course he had followed. Maybe he wasn’t a genuine akratic. Maybe it would be more accurate to say he had a thanatos urge. By this time next week, he thought, there would be nothing left for him to do but go on daytime TV shows. Perhaps in ten years’ time he might be sufficiently rehabilitated to be offered the part of Widow Twanky at the Salvation Army hall in Horsham.

‘Catch you round, then,’ said Barlow to Ziggy.

‘Ciao-ciao,’ called Ziggy, the man of efficiency and ambition. He flashed his pink ‘P’ form, and was admitted to the security bubble.

For the eighth time that morning, Barlow presented his bike for inspection by the authorities.

Roadblock was too modest a word for the Atlantic wall of concrete that the anti-terrorist mob had put in Parliament Square. Each lithon of black-painted aggregate was packed with steel and designed to withstand 83 newtons of force, or a suicide ram-raid with a Chieftain tank.

There was a gap through which cars were being admitted in drips, but all cycles were being stopped.

‘Whoa there, sir,’ said a sixteen-and-a-half-stone American man with a kind of transparent plastic Curly-Wurly coming out of his ear and disappearing into his collar. ‘How are we today?’

‘We’re fine,’ said Barlow shortly.

‘I can’t let you through without a pink pass with the letter P.’ Barlow had grown up in the Cold War, and when at school he had read Thucydides. It had been obvious to him that America was the modern Athens – energetic, pluralistic, the guarantor of democracy and freedom; and therefore infinitely to be preferred to the Soviet Union, closed, nasty, militaristic, the modern Sparta. But now, on being intercepted by an enormous Kansan, just feet away from the statue of Winston Churchill, he felt his gorge rise. His eyes prickled with irritation. ‘I am a Member of Parliament.

‘Oh, damn it all,’ he added; though as luck would have it his curse was lost in the noise of the Metropolitan Police Twin Squirrel swinging high and away towards Victoria.

Had he looked 200 feet behind him, he would have seen the ambulance come to a halt in the queue for the very same traffic lights-cum-checkpoint.

Sitting at the wheel, Jones swore. Any minute now the cavalcade would be upon them. He looked at the Americans, checking each vehicle with glacial deliberation, and checked his watch.

‘Aire fe Mabda’ak,’ he said, which means ‘My cock in your principles’.

The cavalcade was now approximately twenty-seven minutes away from Parliament Square. Apart from the outriders, it consisted of thirty black vehicles, a mobile operating theatre complete with the appropriate blood supplies and a specially adapted Black Hawk helicopter in a continuous hover, intended to snatch the principals in the event of an ambush. The two ‘permanent protectees’, as they were known to the 950 American agents in London, were in a Cadillac De Ville so fortified it was a wonder it could move. The armour plating was five inches thick and designed to withstand direct fire from a bazooka or a mine placed beneath it. There was a tea-cosy of armour around the battery, the radiator and the engine block, to minimize the risk of the fuel catching fire. The glass was three inches of polycarbonate laminate and instead of allowing the driver simply to look through the windshield, an infra-red camera scanned the heat signature of all the objects in the path of the car, and projected an image on the inside of the windscreen. But move the Cadillac did, though at something less than the US speed limit.

Permanent Protectee number one shuffled the papers of his speech and touched the hand of Permanent Protectee number two. It was an insane way to travel, but kind of fun. The cavalcade mounted the ramparted expressway at the end of the M4, and West London was spread out beneath them in the morning sun, like a beautiful woman surprised in bed without her make-up.

‘Gee,’ said the second Permanent Protectee, ‘ain’t that something?’

She smiled at her husband, but secretly she was worried. She had been reading the papers; she knew about the abortive raids on the Islamist cells. That was why she had furtively telephoned Colonel Bluett and begged him to take extra precautions.

Bluett had been frankly amazed, but also pleased to be made her confidant.

‘Yes, ma’am,’ he said. ‘Never mind what the Brits say: that place is gonna be full of my people. I mean some of our top men.’

As the cavalcade began to crawl the last nine miles of its journey, a hatch was opening on the roof of the east wing of the Palace of Westminster, in the cool shadow of Big Ben. Out scrambled the sizeable figure of Lieutenant Jason Pickel.

He stood for a moment on the duckboards, 120 feet above New Palace Yard, listening to the honking of horns down the Embankment, the protesters bleating to each other, like ewes in some distant fold. He held out his hand and squinted at it.

‘Man oh man,’ he said to himself. He stopped the tremor by gripping his sniper’s rifle, and walked on down the duckboard until he found a point of vantage.

‘Are you all right, Jason?’ asked Sergeant Indira Nath, who had followed him up. Indira had been specifically deputed to stay with Pickel, on the orders of Deputy Assistant Commissioner Stephen Purnell.

Not that the British cops had any reason to think of Pickel as a risk. It was just that if they were going to have a Yank sharpshooter on the east wing roof – and Bluett was very keen – then there was damn well going to be a Brit to accompany him.

Indira was from the SO 19 Firearms Unit. She had huge eyes, rosy lips, and tiny, delicate hands, in which she now toted an Arctic Warfare sniper rifle, built by Accuracy International of Portsmouth, capable in the hands of an average marksman of bunching bullets within a couple of inches at more than 600 yards. In the hands of Indira, the gun could shoot the horns off a snail.

‘You OK?’ she repeated.

‘It’s just that something gave me goosebumps here. I guess you could call it Dad flashbacks.’

Dad flashbacks? wondered Indira. It sounded like something worrying from Sheila Kitzinger’s Baby and Child Care. She looked at her neighbour on the roof. He was big and blond, with a proud nose and heavy brow, and hands that made his rifle-barrel look like a pencil. He was dressed in olive drab fatigues, and had the name Pickel sewn in black capitals on his chest, as well as the American flag. She hoped he wasn’t going to blab about some deathbed reconciliation with the father who never loved him.

‘Yeah, honey, it’s like a Nam flashback, ’cept it’s about Baghdad.’

‘Tell me about it, Jason,’ said Indira as they settled down together. ‘Were you scared?’

‘Scared? Did you say scared? Jeez, I was—What the hell was that?’

The American went rigid as percussive waves filled the air. He instinctively eased off the safety catch and now BONG the second explosion assailed his eardrums.

The whole roof vibrated as Big Ben sounded the opening carillon of a quarter to nine.

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#ulink_678a4787-2c6b-53c7-be0f-8040711fa5ec)

0845 HRS (#ulink_678a4787-2c6b-53c7-be0f-8040711fa5ec)

The great clock struck, and Jones cursed (something about a dog, again). The longer they stayed in this traffic jam, the higher their chances of being spotted. Surely the tow-truck man would by now have raised the alarm?

‘But why did he clamp us, sir?’ asked Dean.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Isn’t that why we got an ambulance, so this couldn’t happen?’

‘Have faith, Dean. Has not Allah looked after us? Think of the prophet in his youth, how he became a warrior for God.’

An electronic voice interrupted them. It was female, and spoke in an American accent.

‘Turn left now,’ she said. Haroun cursed. It was the satnav, determined to take the vehicle back to Wolverhampton. Much to the irritation of Jones and his team, they could find no way of silencing her.

‘Soon we will be in the belly of the beast,’ said Jones.

‘Make a U-turn,’ said the satnav, ‘and then turn right in 100 yards.’

The voice of the bossy little robot carried through the driver’s window, and might have reached the ears of Roger Barlow, who was now only a matter of a few feet away; except that he was turned away and bent over.

He was trying to lock up his bike against the railings of St Margaret’s, just until they sorted out this business with the pass.

‘Not there, sir,’ said an American.

‘Where?’

‘Not there, either, sir. I am afraid you will have to take it with you.’

‘But I can’t get into the Commons without a pass, can I?’ The USSS man shrugged.

Barlow stood on the pavement with his bike, like some washed-up crab, as the tide of traffic lapped through the gap and continued around Parliament Square. As he approached his fifty-second year, Roger was conscious that his temper was decreasingly frenetic. He had long since ceased to rave at airport check-ins. If his train was delayed for two hours, it no longer occurred to him to sob and squeal into his mobile. But there was something about being told what to do by this gigantic gone-to-seed quarterback that got, frankly, on his tits.

The Yank was wearing those clodhopping American lace-ups with Cornish pasty welts, a Brooks Brothers button-down shirt, and a large blue blazer. He had the Kevin Costner-ish Germanic looks that you see in so many members of the American military.

‘Well, can I borrow your mobile? I need to get this blasted pass from my assistant.’

‘That’s not allowed, sir.’

Barlow was fed up with the moronic anti-American protesters who were fringing the square and bawling their questions about oil and how many kids Nestlé had killed that day. But he was also fed up with being treated like a terrorist, when he was a bleeding Parliamentarian, and the people of Cirencester had sent him to this place, and it was frankly frigging outrageous that he should be denied access by this Yank. Not that he wanted to be anti-American, of course.

‘They’ll vouch for me,’ he said, pointing to a trio of shirt-sleeved, flak-jacketed Heckler and Koch MP5-toting members of the Met.

No they wouldn’t.

‘Sorry, Mr Barlow, sir,’ said one of them, ‘I am afraid you’ve got to have a pink form today. It’s all been agreed with the White House.’

‘Well, can I use your phone, then?’

‘They’ll have my guts for garters, sir, but there you go.’

Cameron had just reached the office, and was tackling the mail. ‘I’ll come now,’ she said, when he explained the problem.

Roger handed back the phone to the Metropolitan Policeman, and stared again at the American.

‘Is it true that there are a thousand American Secret Service men here?’

‘That’s what I read, sir.’

Barlow couldn’t help himself. He went back to Joe of the USSS.

‘Excuse me. I think you really ought to let me through, because I was elected to serve in this building, and you have absolutely no jurisdiction here.’

‘I know, sir,’ said the human refrigerator, and he touched the Curly-Wurly tube in his ear and mumbled into the Smartie on his lapel. ‘I’m not disagreeing with you, sir, not at all. I have no doubt that you are who you say you are, and I really apologize for this procedure. But my orders say clearly that I don’t let anyone through today without a pink P form, and if anyone gets through today who shouldn’t get through today, then my ass is grass. I’m not history, I’m not biology, I’m physics. Wait, Joe, who are those guys?’

Everything without a pass was being sent up Victoria Street, but now an ambulance had drawn up at the checkpoint. The linebacker was staring at it, but Roger wanted his attention.

‘May I see your ID?’ he said. He knew he was being a pompous twit, but honestly, this was London …

With great courtesy, considering what a nuisance the Brit MP was being, the American Secret Service man opened his wallet and produced a badge. It had a blue and red shield within a five-pointed gold star, and on the roundel was inscribed ‘United States Secret Service’.

‘There you go, sir. Is that OK?’

Roger couldn’t help it. These credentials should mean nothing to him, not on the streets of London. But he felt a childish sense of reverence.

‘Er, yes, that is … OK.’

‘Just wait here, sir,’ said the American, and he strolled towards the ambulance driven by the man whose passport said he was called Jones.

‘How are you guys today?’ he enquired, removing his shades, the ones with the little nick in the corner, and holding out his hand for their papers.

‘At the next junction, turn left,’ said the female Dalek of the ambulance satnav.

‘What’s that?’ said Matt the USSS man.

‘She is a machine,’ said Jones. ‘She is stupid. She is nothing.’

As Roger Barlow saw the Levantine-featured fellow hand over a pink P form, a thought penetrated his mental fog of guilt, depression and self-obsession.

‘Oi,’ he said to the American, but so feebly that he could scarcely be heard above the chanting. ‘Hang on a mo,’ he said, almost to himself.

‘Joe,’ called the vast American to one of his colleagues, ‘would you mind checking in the back of the van here? You don’t mind, sir,’ he said to Jones, ‘if we check in the back of your ambulance?’

‘It’s an ambulance, Matt,’ said Joe.

‘I know, but we gotta check.’

The queue behind set up a parping, and down the Embankment the noise of the protesters reached an aero engine howl.

All the Americans were now touching their trembling ears, and the men from the Met were listening on their walkie-talkies.

‘Joe,’ called Matt, as his colleague approached the rear of the ambulance, ‘we gotta clear this stretch of road more quickly. We got the cavalcade in around twenty minutes. We’ve got POTUS coming through.’

‘POTUS coming through,’ said Joe, and slapped the flank of the ambulance as if it were a steer. ‘You boys better git out of the way.’

‘Hang on a tick,’ said Roger Barlow, a little more assertively. ‘You know it really isn’t possible,’ he murmured, as the ambulance went slowly round the back of the green and came to a halt at the traffic lights. ‘I saw those guys a few moments ago.’ Another thought half-formed in his depleted brain.

Jones stowed the forged pink P form on the dashboard and touched the accelerator.

CHAPTER TWELVE (#ulink_e291f0df-dee5-57b1-b5b4-fbe0e93d5cc9)

0851 HRS (#ulink_e291f0df-dee5-57b1-b5b4-fbe0e93d5cc9)