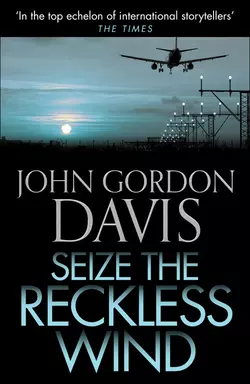

Seize the Reckless Wind

Seize the Reckless Wind

John Gordon Davis

A magnificent novel of ambition, love and adventureIt had not been easy for Joe Mahoney to leave his beloved Rhodesia. All he possessed by the time he reached England was a battered cargo plane and a dream. From this slender beginning, Mahoney and his partner built the Rainbow – the project that would revolutionise the face of commercial flying.Mahoney had everything to gain and little enough to lose – but there were some very interested parties who planned to make certain he lost it all …

JOHN GORDON DAVIS

Seize the Reckless Wind

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_a5e2fabd-5283-5f35-99e7-fcec5e6155e0)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1984

Copyright © John Gordon Davis 1984

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com

John Gordon Davis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007574414

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780008119300

Version: 2014-12-19

DEDICATION (#ulink_cd1031e8-6246-50d4-80be-5f7ee604045b)

FOR ROSEMARY

I am deeply indebted to Malcolm Wren of Wren Airships Ltd. and his staff for all their patient instruction in the science of airships, and to Kevin McPhillips, Harry Green, Lynn Wilson and Michael Owen for taking me literally under their wing and allowing me to learn at first hand about the air frieght business.

All the characters in this novel are, however, fictitious.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u5bd39797-2fd1-54a7-b506-eabf715954ca)

TITLE PAGE (#uffa9cf00-c079-5155-b69d-c09899f7f0b4)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_a4447baa-3b3d-54c1-b120-48d8b2169386)

DEDICATION (#ulink_427bf77b-98ec-53a7-9262-360ebe10dc9d)

PART 1

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_d108ee95-b20e-58cc-abbd-3dd2d5ce2862)

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_78856bac-f341-507b-9747-936d8e1fb957)

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_5c420dcb-fcec-5bd3-aebf-a54c4d6ead94)

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_8847445b-e85f-5e79-ba98-eab38d44f0ba)

PART 2

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_b28b0367-e533-5d8a-9900-d307ad6e3555)

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_aea74879-23f2-5922-90d3-040608fbe383)

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_0a2bd203-bb0b-514e-9150-458717e9a302)

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_3a3781e8-4e32-594c-9dd8-fd7c6ed7bc98)

CHAPTER 9 (#ulink_1715f88e-60bf-5e92-9a61-dadb96f27b20)

PART 3

CHAPTER 10 (#ulink_916e3906-6c3f-5ba3-874e-c2e67366e384)

CHAPTER 11 (#ulink_b85e6005-6760-56d1-9dd4-e7d23ee0a563)

CHAPTER 12 (#ulink_75acc77b-f5a7-5bd6-b0fa-6cab951287b8)

CHAPTER 13 (#ulink_5841b559-4ced-53a8-82d2-06c7d1cbe6b6)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 4

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 5

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 6

CHAPTER 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 7

CHAPTER 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 8

CHAPTER 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 9

CHAPTER 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 10

CHAPTER 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 72 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 73 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART 11

CHAPTER 74 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 75 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 76 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 77 (#litres_trial_promo)

KEEP READING (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

PARIS 1897

It was a beautiful morning. The Eiffel Tower rose up into a cloudless sky. Crowds thronged the Champs-Elysées and the cafés, bonnets and parasols and top hats everywhere, and carriages were busy. A parade marched towards the Arc de Triomphe, the people cheering and flags waving. Then there was a new sound above the applause, and a blob came looming over the treetops, spluttering. It was a man flying a tricycle.

His name was Alberto Santos-Dumont. It was one of those newly-invented De Deon motor-tricycles; but the steering was connected to a canvas frame behind, like a ship’s rudder, and the engine turned a wooden propeller. Above this contraption floated a big egg-shaped silk balloon of hydrogen, from which the tricycle with the incumbent Alberto were suspended.

Alberto sailed low over the crowds, and all faces were upturned, delighted and waving. The air-cycle went buzzing and backfiring round the Arc de Triomphe, then it headed over the rooftops towards the Eiffel Tower. It rose higher and higher, then sailed ponderously round the mighty tower to roars of applause.

Whereupon Alberto wanted a drink. He came looming down towards the boulevards, spluttering between the treetops, making horses shy. Ahead was his favourite café. Alberto brought his flying machine down lower, and steered it towards a lamppost. He threw down a coil of rope, and his friends grabbed it and tied it to the lamppost. Alberto’s engine backfired, and died. The balloon-cycle was moored, hitched above the cobblestones like an elephant.

Alberto jumped down, and walked jauntily into the café, smiling and shaking hands.

ENGLAND 1929

Those were the days of glory and empires, when the statesmen of Europe carved up the world, planted their flags and brought law and order, and Christianity, to the heathen. Everything was well ordered, and if you looked at an atlas much of it was coloured red, for Great Britain, not red for communist as it would be coloured today. The world was full of adventure; and the vast wild places teemed with animals, the seas were full of fish and whales. This was only yesterday, only in your father’s day, and maybe in your own. The world was beautiful, and there were no oilslicks on the seas, no oil fumes hanging in the air, no pollution blowing across oceans to make acid rain in faraway places. In those days there were some dashing young men in flying machines, but it was before the age of air travel.

In a field outside the town of Bedford stood two great hangars. Inside one of them, hundreds of men were building a great airship, as long as two football pitches put end to end, great frames of aluminium covered in canvas, and its huge gasbags were made of ox-intestine, to be filled with hydrogen. The ship was being built by the government and it was called the R 101. Across country, in Yorkshire, another airship was being built by a private company for the government, and it was called the R 100. The R 100 was finished first, and she flew on her trials to Canada and back, to much acclaim. There was great urgency to finish the R 101 so she could carry the Secretary of State to India and back in time for the Empire’s Jubilee. But when the R 101 was tested, she was sluggish. So they cut her in half and added a whole new section to hold another huge gasbag. But there was not time for all her trials before she left.

It was a cold, rainy afternoon when the R 101 took off for India, with her famous personages aboard. She flew over London, and down in the streets people were waving madly. It was dark when she flew over the Channel, and the rain beat down on her. As she flew over the coastline of France the captain reported by radio to London that his famous passengers had dined well and retired to bed.

That was the last communication.

It is not known for certain why it happened but near Beauvais the great ship came seething down to earth out of the darkness. There was a shocking boom and the great frame crumpled and a vast balloon of flame mushroomed up, and then another and another, and the huge mass of buckled frames glowed red in the ghastly inferno.

There were only six survivors. The world was horrified. And, after the Commission of Inquiry, the other airship was dismantled in her hangar, and broken up with a steam-roller, and sold for scrap.

NEW JERSEY, AMERICA: 7 MAY 1937

In the late afternoon the monster appeared.

It came from the Atlantic, looming slowly larger and closer towards the skyscrapers of New York. It had huge swastikas emblazoned on its tail. It was over seven hundred feet long, a leviathan filled with seven million cubic feet of hydrogen. The sun shone silver on her mighty body, and down in the concrete canyons the people stared upwards, awed, and the passengers gazed down on beautiful Manhattan, the Hudson with steamships from all around the world, the Statue of Liberty, Long Island fading into distant mauve, America stretching away in the lowering sun: Her sister ship, the Graf Zeppelin, had made one hundred and thirty trans-Atlantic flights in the last nine years, but people never tired of seeing such massive beauty sailing so majestically through the sky. She was called the Hindenburg, and she was the newest prize of the German airfleet. She could carry seventy passengers, sleeping in real cabins and dining in a saloon at real tables with real cutlery, strolling along promenade decks, looking down on to the countrysides gliding quietly by below, so close they could even hear a dog bark and a train whistle.

There was a big crowd awaiting her at the Lakehurst airfield in New Jersey; the ground crew, people to meet the passengers, pressmen, sightseers. The sun was setting when she came into sight. She came through the darkening sky, slowly becoming larger and larger, the captain slowly bringing her down, and the crowd broke into a mass of waving.

The mooring mast was a high steel structure. The ship came purring across the airfield towards it, headed into the breeze, a wondrous silver monster easing down out of the sky; a rope came uncoiling out of her nose; the ground crew ran for it. There was the sound of an explosion; for an instant there was a hellish blue glow, then a great flame leapt upwards.

It exploded out of the stern, and in a moment most of the airship was engulfed in barrelling fire. Instantly half the canvas was gone and the frame glared naked in the sky; the flame mushroomed enormously upwards, yellow and black, and the stern began to fall. There was a second explosion and more flame shot up, the great ship shook. All the passengers knew was the terror, and the deck suddenly lurching away beneath them, and the terrible glare, and the heat. Now the flaming ship was falling to earth in a terrible slow-motion, stern first. There was a third explosion and the airship hit the ground, a blazing mass of frames and flames. The crowd was screaming, people were running to try to help and the radio commentator was weeping, ‘Oh my God … It’s terrible … I can’t watch it … All those people dying … Oh my God this is terrible …’

Some people leapt out before it hit the earth, some managed to fight their way out as it crashed. They came staggering out, reeling, on fire, twisting and beating themselves, roasting and crazed. The night was filled with flame and weeping and shouting.

PART 1 (#ulink_1c97e7eb-e398-55c8-958c-7a58a4a37a01)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_458e203b-effc-50d3-8a8c-32ea315e7297)

It is always hot in the Zambesi Valley. From the hard escarpments the valley rolls away, descending through many hills, stretching on and on, mauve, fading into haze, like an ocean, so vast you cannot see the escarpments on the other side. It is a wonderful, wild valley, with elephant and lion and all the buck, and the river is hundreds of yards wide, with sandy banks and islands, and hippo, vundu fish as big as a man, big striped fighting tiger fish, and many crocodiles. The mighty river flows for thousands of miles, from the vast bushland of Angola in the west, over the Victoria Falls – the Smoke that Thunders – through Rhodesia, and Mozambique, and out into the Indian Ocean in the east. The river flows through many narrow rock gorges on this long journey, and where it twists and roars through the one called Kariba it is the home of Nyamayimini, the river god. It was at the entrance to this god’s den that the white man built a mighty wall across the river, to flood a huge valley to the west and create an inland sea.

For those were the days of the ‘winds of change’ that swept through Kenya to the rest of Africa, and the big brave days of Federation and Partnership between white go-ahead Rhodesia, black copper-rich Zambia and poor little Malawi; partnership between the races, equal rights for all civilized men, big white brother going to help little black brother, economic and political partnership, white hand clasped with black hand across the Zambesi. And the white man built the wall across the mighty river to create electricity for the industries that were going to boom, and the inland sea was a symbol of this new partnership. There were the political ones, black men in city clothes who came to the valley and told the Batonka people that the story of the flood was a white man’s trick to steal their land, and that they must make war; but the wall slowly went up and the great valley slowly, slowly drowned and died. And with it a whole world of primitive wonder. It was heartbreakingly sad. One day all of Africa would die like that, under the rising tides of the winds of change.

And very soon the partnership died as well, because by the nature of things it was a partnership between the white rider and the black horse, and because the winds of change moaned that there must be One Man One Vote and that the rider must be black. And the political ones, who had been to Moscow and Peking, swaggered through the bush calling the people to meetings, telling them that they must join the Party and take action. Action, boys, action! Burn the schools and burn the missions, burn the diptanks in which the government makes you dip your cattle, stone the policemen and stone the people who are going to work in the factories, burn the huts of the people who do not take Action, maim their cattle and beat their wives and children – and when we rule the country every man will have a white man’s house and a bicycle and a transistor radio. And great mother Britain had lost her will; she dissolved the partnership and gave independence to black Zambia and black Malawi because it was easier and cheaper to give away countries than to govern. But she refused independence to white Rhodesia, because that too was easier than to shout again st the winds. And the white men in Rhodesia were angry, for they had governed themselves for forty years and they feared that if they were not independent Great Britain would give them away too, and so they declared themselves independent, as the American colonies had done two hundred years before. Thus the white men made themselves outlaws, and the winds of change howled for their blood, and began to make war.

In the third year of that Rhodesian war, when a new election was coming up, Lieutenant Joe Mahoney, who was a lawyer when he was not soldiering, almost won a medal for valour, but do not be too impressed by that because it happened like this:

The truck carrying his troopers was trundling along the escarpment of the Zambesi valley when suddenly there was a burst of gunfire, the truck lurched and Mahoney, who was standing at that moment, fell off the back. He landed with a crash on the dirt road, but still clutching his rifle. For a bone-jarred moment all he knew was the shocked terror of being left in a hail of gunfire; then he collected his wits, scrambled up and fled. He fled doubled-up across the road, and leapt into the bush, desperately looking for cover, when suddenly he saw terrible terrorists leaping up in front of him.

Leaping up and running away, terrorists to left of him, terrorists to right of him, all running for their lives instead of blowing the living shit out of him. For Mahoney, in his shock, had run into their gunfire instead of away from it; all the terrorists saw was the angriest white man in the world charging at them with murder in his heart, and all Mahoney knew was the absolute terror of running straight into the enemy and the desperate necessity of killing them before they killed him, and he wildly opened fire. Firing blindly from the hip, sweeping the bush with his shattering gun, the desperate instinct to kill kill kill the bastards before they kill me, and all he saw was men lurching and crashing in full flight – he went crashing on through the bush after them, God knows why, gasping, Joe Mahoney single-handedly taking on the fleeing buttocks of the Liberation Army – he ran and ran, rasping, stumbling, and through the trees he saw a man, fired and saw the blood splat as the man contorted; then Mahoney threw himself behind a tree and slithered to the ground, on to his gasping belly; then his own boys were coming running through the trees; and he sank his head, heart pounding, sick in his guts.

He had just killed seven men all by himself, and he was a hero. Maybe the whole thing had taken one minute.

For the next two days they tracked the rest of the terrorists. The tracker walked ahead, flanked by two men to watch for the enemy while his eyes were on the ground; the troopers followed behind, eyes constantly darting over the bush, every muscle tensed for the sudden shattering gunfire, ready to fling themselves flat. For two days it was like that, stalking through the endless bush under the merciless sun, slogging, sweating, and all the time every nerve tensed to kill and die – and oh God, God, Mahoney hated the war, and hated himself.

Because Joe Mahoney, QC, Africa-lover, African lover, just wanted to kill kill kill and get it over, with all his stretched-tight nerves he longed for contact, so that he could go charging in there and get it over with … But for what?

Because the enemy were murderous bastards who brutalized their own tribesmen, burned their huts and crops and schools and maimed their cattle, terrorizing everybody into submission because that is the only law Africa respects? Because they were smash-and-grab communists, their heads stuffed with the nihilism of Moscow and Peking who are dedicated to the destruction of the West, to the wars they were waging and winning in the rest of Africa and Central America and Asia and the Middle East, winning by default because the West was now so pusillanimous and gutless? Ah yes, when he reminded himself of these matters Joe Mahoney did not feel so bad. ‘What are you fighting for, lad?’ he sometimes asked round the fire at night, when the theory is you should be a father-figure to your men, though he really asked it because he wanted to ease his conscience.

‘For my country, sir.’

‘Against the communists, sir.’

‘Anything else?’

(And, God knows, was that not enough?) There always ensued a rag-bag discussion in which half-digested evidence steamrollered itself into gospel truth, tales of barbarity mixed with contempt. How the fucking hell can they rule the fucking country, sir? Usually Mahoney just listened like the magistrate he used to be when large tracts of the world were still governed by the impeccable Victorian standards of the old school tie, a good grasp of Latin verbs and the ability to bowl a good cricket ball. Sometimes he interrupted them with something like: ‘Gentlemen, I know we’re all in the bush getting our arses shot off without the comfort and society of our womenfolk, but do you think we can uphold some of these standards we cherish by not making every adjective a four-letter word?’

But usually he just sat there and listened, his dulled heart aching, for Africa. Because Africa was dying, bleeding to death from self-inflicted wounds. And his heart ached for his troopers too, because Africa was all they had and they were going to lose it, and they did not realise that it was really a black man’s war they were fighting and dying for. ‘For my country, sir, because how the hell can they run the country, sir?’ Oh, it was true. But they thought they were fighting a white man’s war, for the white man’s status quo. And, if so, was it a just war? Had the white man given the black man his fair share of the sun? And, if not, could this war be won? To win, must not the army be the fish swimming in the waters of the people? Was not the real battle for hearts and minds?

The next afternoon the spoor led to a kraal of five huts. The troopers silently surrounded the kraal, while the tracker did a big three-sixty through the surrounding bush, looking for the terrorists’ spoor leading out. After fifteen minutes he found it.

‘How old?’

‘A few hours,’ the tracker said. ‘They left about noon.’

Mahoney turned and ran back to the kraal, while his men kept him covered. ‘Where is the headman?’ he shouted.

The African woman looked up, astonished. An infant with flies round his nostrils stared, then burst into tears. People came creeping out of the huts, wide-eyed, young and old, in white man’s tatters. ‘Are you the headman, old gentleman?’ Mahoney demanded.

The man was grey-haired. ‘Yes, Nkosi.’

‘Some terrorists have been to your kraal today. How many?’

The old man was trembling. ‘I have seen nobody, Nkosi.’ Everybody was staring, frightened.

Mahoney took him by the elbow and led him aside.

‘Their spoor leads into your kraal. Where were they going?’

The old man was shaking. ‘They did not say, Nkosi.’

‘What did they want from you?’

The old man trembled. ‘They ordered my wives to cook food.’

‘How many men?’

‘I think there were ten.’

Mahoney took a big, sweating breath. ‘If anymore come, you have not seen me. When I leave now, you will obliterate my spoor in your kraal. Understand?’

Mahoney turned and left. The soldiers started following the spoor again, hard.

When darkness fell they were less than two hours behind the terrorists. With the first light they started again.

After an hour the spoor split into two groups.

‘They’re looking for more kraals. For more food.’

Mahoney divided his men. After an hour the spoor he was following turned. It headed back towards the old man’s kraal.

When the terrorists got back to the kraal they ordered the women to cook more food and they sat down to wait.

‘Have you seen any soldiers?’

‘No,’ the old man mumbled.

Everybody had their eyes averted. Then a child spoke up boastfully: ‘Yesterday a white soldier came.’

First they beat up everybody, with fists and boots and rifle butts, and the air was filled with the screaming and the wailing. Then they threw the old man on his back. They lashed his hands and feet to stakes. They staked his senior wife beside him. Then the commander thrust an axe at the eldest son: ‘This is how we treat traitors to the Party! Chop your father’s legs off!’

And the women began to wail and the youth cowered and wept and so they threw him to the ground and kicked him, and then the commander picked up a big stone and he held it over his mother’s face: ‘This is how we treat people who do not obey!’

He dropped the stone on to the old woman’s face. And her nose broke and she cried out, spluttering blood, half-fainted; he picked up the stone and held it over her again, and dropped it again. Her forehead gashed open and she fainted, gurgling blood. The commander shouted: ‘Now chop your father’s legs off!’

And the boy wept and cowered, so they beat him again. And the commander held up the stone again: the old woman had revived, her face a mass of blood and contusion, breathing in gurgling gasps, and when she saw the stone poised again she cried out, cringing; and the man dropped the stone again. There was a big splat of blood and she fainted. The commander shouted: ‘Tie wire around his testicles!’

They pulled the boy’s trousers off and tied a long wire tight around his scrotum so he screamed, then they yanked him to his feet in front of his father and thrust the axe in his hand.

‘Chop well! For each chop we will pull your balls and drop the stone on your mother’s face! Now chop!’ And the wire was wrenched.

The boy screamed, and the wire was wrenched again, and he lurched the axe above his head, his tears streaming, and the old man wrenched at his bonds, and the commander slammed his boot down on his throat. ‘Chop!’ he roared and the wire was wrenched and the boy screamed again, and they wrenched the wire again and his face screwed up in agony, and he swung the axe down with all his horrified might. There was a crack of shin-bone and the leg burst open, sinews splayed, and the old man screamed and bucked and the commander bellowed.

‘One!’

And he dropped the stone on the woman’s face and the wire was wrenched so the boy screamed through his hysterical sobbing, and he swung the axe on high again and swiped it down on the other shin, and there was another crack of bone, and another gaping wound in the glaring sunshine, white shattered bone and sinews and blood, and the commander shouted.

‘Two!’

And he dropped the stone again and the wire wrenched and the boy screamed, reeling, and he swung the axe again at his father’s legs.

‘Three!’

And another crash of the stone, and another wrench of the wire. ‘Four!’ And again. ‘Five!’ And now the boy was hysterically swinging the axe, out of his mind with the horror and the agony, and there was nothing in the world but the screaming and the blood and stink of sweat under the African sun. Altogether it took the boy nine swipes to chop his father’s legs right off, but his mother was dead before then, suffocated in her own blood.

The troopers heard the screams a quarter of a mile away. They came running, spread out. Mahoney saw the old man writhing, the youth reeling over him with an axe, the terrorists, and he thought the youth was one of them – and he fired; then his men opened up, and there was pandemonium. The cracking of guns and the stench of cordite and the screaming and the scrambling and the running.

A minute later it was almost over. The women had fled into a hut. Three terrorists lay dead, three others had dived into a hut, but they had been flushed out by the threat of a hand-grenade. Mahoney knelt beside the groaning old man in the bloody mud, aghast, holding two tourniquets while the sergeant gave the man a morphine injection. He could not bear to look at the two stumps, the splintered bones sticking out, the severed feet. After a minute the man fell mercifully silent. Beside him lay his wife, her head twice its normal size, her lacerated eyes and nostrils swollen tight shut, her split lips swollen shut in death.

Then Mahoney got the story from the weeping women. He stared at the youth he had shot, and he felt ringing in his ears and the vomit rise in his gut. He walked to the back of the hut, and he retched, and retched.

When he came back the sergeant had lined up the terrorists. They were trembling, glistening with sweat. Mahoney could feel his men’s seething fury for revenge.

‘Shoot them, sir?’

Mahoney stopped in front of the three.

‘Or let the women shoot them, sir?’

‘Chop their legs off too, sir?’ a trooper shouted theatrically.

Mahoney looked at the three. One had his eyes closed in trembling prayer.

‘You savages,’ Mahoney hissed.

Silence. He could feel his men seething behind him. The commander said, ‘I demand the Geneva Convention.’

Mahoney blinked. ‘The Geneva Convention?’ he whispered. Then his mind reeled red-black in fury. ‘The Geneva Convention?’ – he roared and he bounded at the man and seized him by the neck and wrenched him across the kraal to the corpses. He rammed the man’s head down over the stumps of legs: ‘Did the Russians teach you this Geneva Convention? And this?’ He rammed the head over the woman’s pulped face. He seized up the bloody axe and shook it under the man’s face: ‘Is this your Geneva Convention?’

For a long hate-filled moment he held the cowering man by his collar, and with all his vicious fury he just wanted to ram the axe into the gibbering face. Then he threw it down furiously. The sergeant grabbed the man. ‘Shoot them, sir?’

The three terrorists stood there, terrified. Mahoney stared at them. Oh God, to shoot them and give them their just deserts. Oh, to shoot them so that the weeping kraal members could see that justice had been done. Oh, to shoot them so that all the people in the area would know that the white man’s justice was swift and dire.

‘They’re going to be tried for murder and hanged. Radio for a helicopter.’

And oh God, God, he knew why Rhodesia could not win this war. Not because these bastards outnumbered them, not because Russia and China were pouring military hardware into them, and certainly not because they were better soldiers; but because the likes of Joe Mahoney could not bring themselves to fight the bastards by their own savage rules; Joe Mahoney could not even shoot the bastards who chopped people’s legs off. Instead he had to hand them over to the decorous procedures of the courts, where they would be assigned competent counsel at the public’s expense, presumed innocent until proved guilty. They would have a lengthy appeal and thereafter their sentences would be considered by the President for the exercise of the Prerogative of Mercy.

And Joe Mahoney knew that he would soldier no more, that he was not much longer for God-forsaken Africa.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_13a2582e-d439-5e3e-a91e-637cbf847940)

The town of Kariba is built on the hot valley hilltops above the great dam wall, and the inland sea floods into these hills to make many-tentacled bays and creeks. Along this man-made coastline are hotels and beaches. The army barracks is on the hilltops overlooking the vast blue lake that stretches on and on, over the horizon, reaching into the faraway hills. Way out there was a safari lodge for tourists, which Mahoney partly owned. In those days of war, Kariba was an alive little town. At nights the hotel bars were full of soldiers happy to be back from the bush alive, and Rhodesian tourists who had almost nowhere else to go because of the war, so the air throbbed with dance and music, and talk and laughter. Mahoney was always happy when he came back to Kariba: it was an end to weeks of confrontation with death, and exhaustion, an end to running, and fear, and sweat, and thirst. But when he came out of the bush that last time, trundling down the hot hills of the escarpment back to his barracks, Joe Mahoney was not happy, because he loved somebody who did not love him.

‘But I do love you,’ he heard Shelagh say. ‘It’s that I can’t live with you anymore … I’ve got to be my own person. If I didn’t fight every inch of the way you’d just steamroller my needs underfoot. I’m an artist, which means delicacy, whereas you bulldoze your way through life, like you go into court and bully the witnesses and bully the other lawyers and come out dusting your hands – I’ve seen you in court.’

‘You can stop work altogether and paint all the time.’

‘But I don’t want to stop work, I’m me, I don’t want to be dependent on you! God, why must women be housewives and second-class citizens and even change their names – put “Mrs” in front, like we’re somebody’s sexual property? …’

But he ruthlessly pushed Shelagh out of his mind – he had had six weeks in the bush to get used to the idea. He showered and drank three bottles of beer while he wrote his report. Then he drove to the officers’ mess to buy a few more to take with him. It was a small mess and as he walked in the first person he saw was Jake Jefferson, the Deputy Director of Combined Operations; he turned away, but Jake looked up, straight into his eyes. ‘Hullo, Joe,’ he smiled.

Mahoney stopped. ‘Good afternoon, sir.’ He shook hands. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘Jake’s the name, off duty. A few days’ fishing. With my son. What’ll you have?’

Mahoney felt his heart contract. He desperately wanted to see the lad – just to see him – but yet he didn’t think he could bear it. ‘Nothing, thanks, I’m only buying a few for the road. Barman,’ he called.

Jefferson looked at Mahoney while he made his purchase. ‘I hear you made quite a kill?’

‘Luck.’ Mahoney wondered how the man really felt about him. He then heard himself say, although it was the last subject he wanted to bring up: ‘And how is your son?’

‘Top of his class,’ Jefferson said, and Mahoney wondered for the thousandth time how the man could have no doubts. The barman mercifully came back with his change and he picked up the bottles.

‘Well, excuse me, Jake, good to see you.’

‘Look after yourself,’ Jefferson smiled.

Mahoney walked out, clutching his beers, into the harsh sunlight, trying to look as if nothing had happened. His old Landrover had ‘Zambesi Safaris’ painted on it. He got in, started the engine, and drove off hurriedly, in case the boy should arrive. He got out of sight of the mess, then slowed, letting himself feel the emotion, and the confusion. Then he took his foot off the accelerator entirely, his heart suddenly beating fast. His vehicle rolled to a stop.

Walking towards him was an eight-year-old boy, carrying a fishing rod. Mahoney stared at him, eating him up with his eyes: the blonde hair, just like his mother’s, the same eyes and mouth … The boy came level with the Landrover and Mahoney knew he should not do it, for his own sake, but he couldn’t resist it. ‘Hullo, Sean.’

The boy turned, surprised. ‘Hullo, sir,’ he said uncertainly.

Mahoney smiled at him. ‘Do you know who I am?’

The lad looked embarrassed. ‘I’m not sure, sir.’

‘I’m Joe Mahoney, a friend of your father.’ He wanted to say, And your mother. ‘I haven’t seen you for a couple of years, I should think.’

‘Oh,’ Sean said. ‘How do you do, sir?’

Mahoney felt shakey. ‘You’ve grown,’ he laughed.

‘Yes, sir,’ the boy smiled, and Mahoney wanted to cry out Don’t call me sir!

‘Your father tells me you’re top of your class?’

‘Yes, well, this year, sir.’

Mahoney felt his heart swell. ‘Keep that up. And how’s the rugby?’

‘Well, I’m in the Under Nines A team,’ the boy said, ‘but I’m better at cricket than rugger so far.’

Oh, he wanted to watch him play. ‘Your dad says you’re going fishing?’

‘Yes.’ The boy held up a can. ‘Been buying some worms. We’re after bream, though we won’t have much luck until later.’ He looked as if he wanted to get going.

Mahoney said: ‘Well, do you trawl for tiger fish while the sun’s high?’

‘Yes, sir, I’ve caught five tiger fish in my life.’

In your life … And oh, Mahoney longed to be with him, teach him all about life. How he wished he was taking him fishing this afternoon. Sean said earnestly, ‘I’d better go now, sir; my father’s expecting me.’

‘Well, have a good time, Sean.’ Mahoney reached out his hand. The boy hastily transferred the rod and with the feel of the small hand Mahoney thought his heart would crack. ‘Look after yourself, my boy.’

Sean pumped his hand energetically once. ‘Goodbye, sir.’

‘Goodbye,’ Mahoney said. And it really was goodbye.

The boy strode resolutely on down the road towards the officers’ mess. Mahoney sat, watching him in the rear-view mirror, and the tears were burning in his eyes. He whispered: ‘And keep coming top of the class!’

He drove slowly on, out of the barracks, shaken from seeing the boy; up the winding hills; to the little cemetery at the very top.

He got out of the Landrover. The sun was burning hot. The Zambesi hills stretched on and on below, into haziness. It was a year since he had been here. He stood, looking about for some wild flowers. He picked one. He walked numbly into the cemetery.

The headstone read: Suzanna de Villiers Jefferson.

Mahoney stood in front of it. And maybe it was because he was still tensed up from seeing the boy, and from the bush, but it was all unreal. He whispered: ‘Hullo, Suzie. I’ve come to say goodbye.’

But Suzie did not answer. Suzie only spoke to him when he was drunk nowadays. He did not often speak to her now either, even when he was drunk, because it was all a long time ago, and he loved somebody else now. He stood there, trying to reach her. He whispered: ‘I’m going to tell the people what I think, Suzie. The truth. And they’re not going to listen to me, so then I’m going to leave.’

Suzie did not answer.

Mahoney stood there, waiting. There was only silence. He knelt on one knee, laid the solitary flower on her grave. He closed his eyes and tried to say a small prayer for Suzie to the God he was not sure he believed in. He whispered: ‘Goodbye, Suzie, forever …’ And suddenly it was real, the word ‘forever’, and he felt the numb tension crack and the grief well up through it, the grief of this grave high up in these hot hills of Africa. The heartbreaking sadness that he would never come back, to these hills, to this valley, to that mighty river down there, to this Africa that was dying, dying, to this grave of that lovely girl who had died with it: suddenly it was all real and he felt the tears choke up and he dropped his head in his hands and he sobbed out loud, and he heard Suzie say: ‘Come on now, it’s not me you’re weeping for, or the boy, is it, darling? It’s for yourself; and for Shelagh.’

And he wanted to cry out loud, half in happiness that Suzie was there and half in protest that Shelagh was over, and Suzie smiled: ‘Well, you always wanted a soulmate. And you got one, in spades. But you’re still not happy. Will you ever be happy, darling?’

‘You made me happy, Suzie.’

She smiled, ‘Ah, yes – but I wasn’t clever enough for you, I couldn’t argue the problems of the world with you, and it’s not me you’re weeping for now.’

‘Oh God, forgive me, Suzie …’

She smiled, ‘Of course, darling. Didn’t I always forgive you everything? But what about our son?’

And Mahoney took a deep breath and squeezed his fingertips into his face in guilt and anger and confusion. He whispered fiercely: ‘He’s safe, Suzie, he’s safe and it would be wrong for me to interfere.’

Suzie did not answer; and suddenly she was gone. And Mahoney knew very well that she had never been there, that the conversation had not taken place, but in his heart he almost believed it. He knelt by her grave, trying fiercely to control his guilt and his grief. For a long minute more he knelt; then he squeezed his eyes and took a deep breath. ‘Goodbye, Suzie … ,’ he whispered. He got up, and walked quickly away from her grave.

He drove slowly down the hot, winding hills. He felt wrung out; and when he got to the lakeshore he just wanted to turn left and start driving up out of this valley on to the road to goddamn Salisbury, three hundred miles away, and start telling the people what they had to do to save the country, tell them and then get the hell out of it – wash his hands of goddamn Africa …

But he was going to Salisbury by air, and he had two hours to wait.

He did not want to hurt himself any further: but he had to say goodbye to the Noah’s Ark too. He drove slowly to the harbour.

There she lay on her mooring, long and white, her steel hull a little dented where drowning animals and treetops had hit her.

Mahoney sat, looking at her. The brave Noah’s Ark … He was leaving her too. He picked up a beer, got out of the Landrover and walked on to the jetty. There were a number of rowboats tied up. He rowed out to his Ark.

‘Hullo, old lady …’

He clambered aboard her. He stood on the gunnel, looking about. It was a long time since he had used her, because of the war. He stepped over to the wheel, held it a moment. Below, fore and aft, were the cabins and saloon, locked.

He sat down behind the wheel, with a sigh.

And oh, he did not want to sell her. He had bought her to keep forever. She was part of his Africa, a symbol of this great valley that had died, she had been here from the beginning – that was why he had bought her. For in those brave days of Partnership, when the waters began to rise behind that dam wall, the wild animals retreated into the hills, and slowly the hills became islands as the water rose about them, thousands of hilltop islands stretching on and on; and the animals stripped them of grass and bush and bark, as all the time the waters rose higher, and they crowded closer and closer together; and now they were starving; and eventually they had to swim. But they did not know which way to swim to get out of this terrible dying valley, so they swam to other hilltop islands they could see, and they were already stripped bare. The animals swam in all directions, hooves and paws weakly churning, great emaciated elephants ploughing like submarines with just their trunktips showing, starving buck with heads desperately stuck up, desperate monkeys and baboons and lions. Many, many drowned. The government sent in the Wildlife Department men, and volunteers like Joe Mahoney, to drive the animals off the islands with sticks and shouts and thunder-flashes, to make them swim for the faraway escarpments while they still had strength, heading them off from other islands, trying to drag the drowning aboard. The animals that would not take to the water they had to catch, in nets and ambushes and with rugby tackles, wild slashing buck and warthog and porcupine, and bind their feet and put them in the boats. For many, many months this operation went on as the waters of Partnership slowly rose and more hills became islands and slowly drowned: and the motherboat of the flotilla was this Noah’s Ark.

Now he sat behind her wheel on the great lake, eyes closed; and he could hear the thrashings and the cries and the cursing and the terror, the struggling and the dust and the blood, and the heartbreak of Africa dying. And he remembered the hope: that all this was going to be worth it, that out of this dying would come the new life that Great Britain promised. But it had not come. And now the valley was dead. There were now new cries and screams under the blazing sun, new blood and terror. Partnership was dead, and this grand old boat was all that was left of those brave days, and she also was going to be left behind.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_fd128fcc-a2a6-59e6-9440-484cb6f1bc2d)

There was military transport to Salisbury, but Mahoney and Bomber Brown and Lovelock and Max and Pomeroy flew back to the city in Mahoney’s Piper Comanche, with a crate of cold beers. Bomber did the flying because he did not drink and because Mahoney did not like piloting any more. In fact he downright disliked it. He had asked Lovelock to fly the aeroplane, but Lovelock had shown up at the aerodrome brandishing a brandy bottle and singing, so Mahoney had asked Bomber along. It was a squeeze in the Comanche with five of them, and there were only four sets of headphones, but they made Lovelock do without so that they could not hear him singing, only see his mouth moving. Pomeroy could have flown the plane, for he was an aircraft engineer who also had a commercial pilot’s licence, but Pomeroy was accident-prone and tonight he was throwing one of his back-from-the-bush parties and he had already started warming up for it. Pomeroy was a sweet man but when he drank he tended to quarrel with senior officers. Mahoney had represented him at several courts martial. ‘But Pomeroy,’ he had sighed the last time, ‘why did you make it worse by assaulting the police who came to arrest you on this comparatively minor charge?’

‘I didn’t,’ Pomeroy protested – ‘they assaulted me. They send six policemen to arrest me? An’ they say, “Are you coming voluntary?” An’ I said, “Voluntary? Nobody goes with coppers voluntary – you’ll ’ave to take me.” An’ they tried. Six police? That’s downright provocation, that is …’

But the army put up with Pomeroy because he was such a good aircraft engineer, like they put up with Lovelock because he was such a good flier. Lovelock always looked the same, even when he was sober; amiable and lanky and blonde and pink, not a hard thought in his head. He was one of those English gentlemen who had never done a day’s work in his life because all flying was sport to Lovelock, like golf. The Royal Air Force had finally had enough of him. The story was that he was bringing in this screaming jet for an emergency landing and he had the choice of two airfields: ‘For God’s sake, man, which one are you going for?’ his wing commander had bellowed over the radio. ‘Which one has the pub open, sir?’ Lovelock had asked earnestly. The RAF had fired him. So he got a job with British Airways, and the story was that when he was getting his licence on 747s he rolled the jumbo over and flew her along upside down for a bit, for the hell of it, and got fired again. Now he flew helicopters for the Rhodesian army, and the terrorists fired at him. It was said Lovelock may look like a long drink of water but he had nerves of steel. Mahoney’s view was that he had no nerves at all. He had been flown into combat only once by Lovelock, and that was enough: goddamn Lovelock peering with deep interest into a hail of terrorist gunfire, looking for a nice place to put his helicopter down to discharge his troops, had given Mahoney such heebie-jeebies that he had threatened to brain him then and there. Now Lovelock’s head was thrown back, his mouth moving in lusty silent song:

‘Oh Death where is thy sting-ting-a-ling …

‘The bells of Hell may ring, ting-a-ling …

‘For thee, but not for me-e-e— …’

Max shouted in his ear: ‘Louder, Lovelock, we can’t lip-read.’

‘I can’t hear you,’ Lovelock shouted apologetically, ‘I’m not a lip-reader, you know.’ But they couldn’t hear him.

Mahoney smiled. He had a lot of time for Max. Max was a Selous Scout, one of those brave, tough men who painted themselves black, dressed in terrorist uniform and went into the bush for months spying on them, directing the helicopters in by radio for the kill. Max still had blacking in his hairline and he was going to Pomeroy’s sauna party tonight to sweat it out and run around bare-assed. Bomber said to Mahoney over the headphones: ‘Do you want to fly her for a bit?’

‘No thanks,’ Mahoney said, ‘I don’t like heights.’ And he heard Shelagh say: ‘I don’t know why you bought the wretched thing. As soon as we’re airborne you say “Have you had enough, shall we go back now?” Why don’t you sell it? But no, it’s like that Noah’s Ark, and your safari lodge – you just like to have them.’

‘What else is there to do with money? You can’t take any out of the country.’

‘You could buy a decent house in the suburbs, like a successful lawyer, instead of living behind barbed wire on that farm.’

Oh, he could buy a lovely house in the suburbs for next to nothing these days, he could have lovely tennis courts and clipped lawns and hedges in the suburbs instead of his security fence; and he could also go right up the fucking wall. Mahoney took a swallow of beer to stop himself thinking about Shelagh as the aeroplane droned on across the vast bush, and Pomeroy said: ‘Why don’t you sell the bleedin’ thing if you don’t like flying?’

‘But I do love you,’ he heard Shelagh say. ‘It’s just that you’re so stubborn …’ He said to Pomeroy: ‘I’m going to. And the farm, if I can get anything like a fair price.’

They all looked at him, except Lovelock. ‘Is this Shelagh speaking?’ Max said. ‘Are you getting married at last?’

‘No,’ Mahoney said grimly, ‘I’m going to Australia.’

Max glared at him. Then looked away in disgust. ‘Here we go again. He’s taking the Chicken Run again.’

It was a stilted, staccato argument, over the rasping headphones.

I am proud to be a rebel, said the T-shirts, I am fighting for my country. And by God they could fight! And the government told them, and they believed it, and it was almost all true, that they were fighting for the best of British values, for the impeccable British standards of justice and efficiency that had gone by the board everywhere else; the rest of the world had gone mad, soft, kow-towing to forces of darkness it had not the guts to withstand, and subversion of trade-unionism and communism that was rotting the world – the Rhodesians were the last bastion of decency and sense, the last of the good old Britishers of Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, they alone would fight for decency and commonsense in this continent of black political persecution and incompetence, this rich continent that could not even feed itself any more since the white man left, this marvellous continent that had gone mad with One Man One Vote Once. And anybody who does not stay to fight is taking the Chicken Run.

‘Their fair share of the sun?’ Max echoed angrily over the headphones. ‘The African has his share of the sun but what does he do with it for Chrissakes? He lies in the shade and sleeps off his beer and watches his wives scratch a living! He doesn’t want to work for anything more – he’s incapable of anything more! How can you hand over the country to people like that? What was his share of the goddamn sun before the white man came? Tribal warfare and pillage!’

Mahoney rasped: ‘A whole new generation of blacks has grown up who wants more than that, and two guerilla armies are massing across the Zambesi to get it—’

‘And who’re these armies fighting for? A handful of wide-boy politicians, and if they win because people like you take the Chicken Run the poor bloody tribesmen will get even less of the sun because the country will sink back into chaos!’

‘And how the hell are you going to beat these armies—’

‘By blowing the living shit out of them!’

‘– if we don’t win the hearts and minds of the people?’

‘We’ve tried to win their hearts and minds for Chrissake! Schools and hospitals and agricultural services and diptanks – who paid for all that?’

‘But we didn’t give them Partnership!’

‘Partnership?’ Max shouted. ‘We gave them Partnership and Britain sold us down the river for thirty pieces of silver! We’ve still got Partnership here – the blacks have got fifteen seats in Parliament out of a total of sixty-five!’

Mahoney shouted, ‘Hearts-and-minds Partnership, Max! The educated ones can vote but do we pay the uneducated ones a decent wage, the factory workers and farmboys who’re the basis of the economy? Do we make the black man who’s got a tie and jacket and a few quid in his pocket and wants to take his girlfriend on the town? Do we make him feel like a Rhodesian? Do we hell! Do the black kids at school feel the sky’s the limit if they work hard? And do we make the poor bloody tribesman feel like a Rhodesian, that we’re doing everything to improve his lot?’

‘Oh Jesus!’ Max shouted. ‘How can a handful of whites do more? We do ten times more than the rest of Africa where their own black governments cannot even feed their people! Oh Jesus, somebody stop me from braining this bastard!’

‘I’m going to a better land, a better land by far,’ Lovelock’s mouth bellowed silently.

When you love somebody and she doesn’t love you anymore …

Mahoney tried to thrust Shelagh out of his mind as he drove into Salisbury from the airport, and he was almost successful because he was still angry from his shouting-match with Max, and he had had six weeks in the bush to get used to the idea, and few things unclutter a man’s mind so well as the constant prospect of sudden death: but when he saw the familiar outskirts, he was coming home home home, and every street shouted Shelagh at him; and, when he stopped at wide Jamieson Avenue, all he wanted to do was keep going, across the big intersection into the suburbs beyond, just swing his car under the jacaranda trees with a blast on the horn and go running up the steps and see her coming running down into his arms, a smile all over her handsome face, everything forgiven and forgotten.

But he crunched his heart and turned right, into central Salisbury.

The city rose up against the clear sky, the new buildings and the old Victorians, the streets wide enough to turn a wagon drawn by sixteen oxen, and all so clean. It was home time and the streets were busy, people hurrying back to their homes and clubs and pubs and cocktail parties. Many were carrying guns. There was the big old High Court where he earned his living, the prime minister’s office opposite, the Appeal Court beyond, Parliament and Cecil Square with the bank that kept his money – it was his hometown, and he loved it, and, oh God no, he did not want to give it away.

He parked outside Bude House, left his kit-bag but took his rifle. He took the lift to the seventh floor, to Advocates’ Chambers. The clerk’s back was turned; he hurried down the corridor, past the row of chambers, into his own.

His desk held a stack of court briefs, tied with red tape. He propped his rifle against the wall and started flicking through briefs.

‘I saw you dodging past me. Welcome back.’

He turned. It was the clerk. ‘Hello, Dolores,’ he smiled. ‘I’m in a hurry.’

‘Is Pomeroy all right?’ Pomeroy was her ex-husband.

‘Fine. I flew back with him.’

She relaxed, and turned to business.

‘Well, unhurry yourself, you’ve got lots of work there, first one Monday.’

He sighed. ‘But I’m not going to wake up till Monday! What is it?’ He scratched through the briefs.

‘Company Law,’ Dolores said.

‘But I’m no good at Company Law and I’m going to sleep till Monday!’

‘It’s a fat fee.’

‘What good is money I can’t take out of the country?’

Dolores leant against the door and smiled wearily. ‘Here we go again. Where to this time?’

‘Australia.’

She shook her head, then ambled into the room. ‘But only after you’ve run for parliament, huh?’ She sighed and sat down on the other side of the desk, and crossed her plump, sexy legs.

He was flicking through the briefs. ‘That’s right.’

She looked at him. ‘You’ll be a voice in the wilderness.’

‘I’ll at least do my duty. And make a hell of a noise while I lose.’

‘So we should just give up everything we’ve built? Just hand it to savages on a platter?’

‘There’s a middle course. And if we don’t take it, it’ll be our heads on that platter.’

She sighed bitterly. ‘How goes the war? Are we really losing?’

‘We’re thrashing them. But we can’t keep it up forever.’ He put down the briefs and crossed his chambers and closed his door. He sat down heavily. He dragged his hands down his face. ‘Dolores, we’re going to lose the war, this way. Not this year, not next, but soon. By sheer weight of numbers. And the rest of the world is against us, the whole United Nations.’

‘The United Nations,’ Dolores said scornfully – ‘that Tom and Jerry Show.’

‘Indeed,’ Mahoney sighed. ‘But that’s where the economic sanctions come from. We’re outlaws, Dolores. And we cannot win unless we also win the hearts and minds of our own black people.’ He spread his hands wearily. ‘The answer is obvious. We’ve got to make a deal with our own moderate blacks – bring them into government. Form a coalition with them, and unite the people, black and white. Have a wartime coalition, with black co-ministers in the cabinet, and meanwhile write a constitution that guarantees One-Man-One-Vote within the next five years.’ He spread his hands. ‘Then we can turn to the world and say, we are truly multi-racial, so stop your sanctions now! And then we can get on with winning this war against the communists. As a united people.’ He looked at her wearily. ‘That’s the only way, Dolores.’

She said bitterly: ‘What you’re saying is we must fight the black man’s battle for him, so that within five years he can rule us with his usual incompetence.’

Mahoney cried softly, ‘For God’s sake, either way you slice it, it’s a black man’s war we’re fighting. Because if we carry on this way we’re going to lose and we’re going to have the terrorists marching triumphant into town and ruling all of us, black and white, butchering all opposition. We must act now, while we’ve still got the upper hand and can bargain to get the best terms for ourselves under the new constitution. Next year will be too late.’

She was looking at him grimly. He smacked the pile of court-briefs. ‘I’ll do these cases, but don’t accept any new work for me. I’m starting my brief political career.’

She sighed deeply and said, ‘You and your sense of duty – I hope it makes you learn some Company Law before Monday.’ She stood up wearily. ‘Come on, I’ll buy you a beer.’

He shook his head. ‘I’ve got to work, Dolores. And sleep.’

She looked at him. ‘It’s Shelagh, isn’t it? You want to wonder who’s kissing her now.’ He smiled wanly. ‘She’s just not worth it, Joe! Heavens, snap out of it, you could have just about any woman you wanted.’ She glared, then tried to make a joke of it. ‘Including me. Pomeroy says I should have a fling with you, get your mind off Shelagh.’

He smiled. ‘It’s a pretty thought.’ He added, ‘Are you going to the party?’

‘Hell no, it’s Vulgar Olga’s turn tonight.’

‘Why do you put up with him?’ Mahoney grinned.

‘Just because I divorced him doesn’t mean I’ve got to stop sleeping with him, does it? One may as well sleep with one’s friends …’

But he did not set to work. He went down the corridor to the library, found Maasdorp on Company Law, slung it in his robes bag, picked up his rifle and left. He started his car, then sat there, wondering where the hell to go. He did not want to go to Pomeroy’s house and swim bare-assed and hear how he couldn’t get spare parts for his aeroplanes; he did not want to go to Meikles and see the one-legged soldiers drinking, nor to any bars and feel the frantic atmosphere around the guys going into the bush; nor to the Quill Bar and listen to the journalists talking about how we’re losing the war; nor the country club and listen to the businessmen crying about sanctions. The only place he wanted to go was Shelagh’s apartment.

But he did not. He drove through the gracious suburbs with the swimming pools and tennis courts, on to the Umwinzidale Road. The sun was going down, the sky was riotously red. He drove for eleven miles, then turned in the gateway of his farm; he drove over the hill. And there was his house. He stopped at the high security fence, unlocked the gate, drove on. He parked under the frangipani tree, and listened. He heard it, the distant, ululating song coming from his labour compound. It was a reassuring sound, as old as Africa, and he loved it.

It was a simple Rhodesian house that he’d built before he had much money. A row of big rooms connected by a passage, a long red-cement verandah in front, the pillars covered with climbing roses, then thatch over rough-hewn beams. It was comfortably furnished with a miscellany which he had accumulated from departing Rhodesians. He went into his bedroom, slung down his bag and rifle. The room was stuffy but clean; he looked at the big double bed, and it shouted Shelagh at him.

He turned, went to the kitchen, got a beer. He was not ready for work yet. He opened the back door, and stepped out into the dusk.

It was beautiful, as only Africa can be beautiful. The smell and sounds of Africa. The lawns and gardens were surrounded by orchards. He had planted a eucalpytus forest and beyond were sties in which a hundred sows could breed two thousand piglets a year. Stables, chicken runs. He had nearly a thousand acres of grazing and arable land, plenty of water from bore-holes. It was a model farm. He did not make much profit, but what else had he been able to do with his money, except buy more land, start more projects? Beyond his boundaries was African Purchase Area, where black farmers scratched a living. Once upon a time he had cherished the notion that he could help them, by being an example, but that had not worked out. The wide boys from the towns had sabotaged that, burnt his house, killed his prize bull, and Samson – good old Samson, who had been with him on Operation Noah – had hanged for it. It was a model farm, but who would want to buy it now? And what good would the money do him? When he emigrated he could only take a thousand dollars.

Mahoney turned grimly towards the swimming pool. And, oh, he did not want to emigrate. He did not want to leave this marvellous land and go and live with the Aussies, where there was nothing important to do except make money. …

Suddenly he realized something had changed. He stopped and listened. Then he realized: the singing had stopped.

Not a sound, but the insects. Automatically, he wanted his rifle. He turned and started towards the labour compound, through the orchards.

From fifty yards he could see the huts. He stopped amongst the eucalyptus. He could see his labourers around the fire, their wives and children, silent, staring. He walked closer.

An old man was kneeling near the fire. In the dust were some small bones. Mahoney had never seen the man, but he knew what he was. He was a witchdoctor.

Mahoney stood there. What to do? The practice of witchcraft was a crime, but he did not like to interfere in tribal customs. He stood in the darkness, waiting for the man to speak: then his foreman glanced up. ‘Mambo …’ he murmured.

Everybody turned, eyes wide in the flickering firelight.

Mahoney called, ‘Elijah, please come to my house.’

He turned. The old foreman followed him.

Mahoney walked back through the trees, and stopped outside the kitchen. Elijah came, smiling uncomfortably. Mahoney clapped his hands softly three times, then shook hands. He spoke in Shona: ‘I see you, old man.’

‘I see the Mambo,’ Elijah said, ‘and my heart is glad.’

‘I have returned and my heart is glad also.’

Mahoney squatted on his haunches. Elijah squatted too, and they faced each other for talk as men should. And the ritual began. It was an empty ritual because Elijah knew the Nkosi had seen the witchdoctor, but it was necessary to say these things to be polite. ‘Are your wives well, old man?’

‘Ah,’ Elijah said, ‘my wives are well.’ The Nkosi did not have any wives, so Elijah said: ‘Is the Nkosi well?’

‘I am well. Is Elijah well?’

‘Ah,’ Elijah said, ‘I am well.’

‘Are the totos well?’

‘Ah,’ said Elijah, ‘the totos are well.’ The Nkosi did not have any children, so Elijah said: ‘Does the Nkosi sleep well?’

‘I sleep well. Does Elijah sleep well?’

Ah, Elijah slept well. Are the cattle well? Ah, the cattle were well; but there is drought. Are your grain huts full? Ah, there is drought, but there was grain in the huts. Are your goats well? Yes, the goats were well …

Everything was well. Business could begin. ‘Old man, is there sickness in the kraal?’

Elijah knew what was coming, and he looked uncomfortable. ‘There is no sickness, Nkosi.’

‘Are any of the wives barren?’

Elijah said, ‘The wives are not barren, Nkosi.’

‘Are there any witches living amongst us?’

‘Ah!’ Elijah did not like to talk about witches. ‘I know nothing of witches, Nkosi.’

Mahoney sighed. Once upon a time he had been a young Native Commissioner in charge of an area the size of Scotland or Connecticut. How many men had he sent to jail for this?

‘Old man, there are no such things as witches who cast spells to make people ill, or barren, or their cattle sick, or their crops to die. There are no such people as witches who ride through the sky on hyenas in the night.’ He made himself glare: ‘And it is a crime to consult a witchdoctor to smell out a witch, because stupid people believe him, and they banish the woman he indicates, and she is homeless. And very often she takes her own life. That is a terrible thing, old man!’

Elijah said nothing.

Mahoney breathed. ‘The cattle are thin.’ He looked up at the cloudless sky. ‘How much have you paid the witchdoctor, to make the rains come?’

Elijah shifted uncomfortably. It was no good to lie. ‘Each man paid thirty cents, Nkosi.’

Ten men, three dollars, his labour force had just been defrauded of three dollars. What was he going to do about that? Make the witchdoctor give the money back? Drive him off his property? He sighed. No. It would shock and embarrass Elijah, terrify his labourers, show contempt for the peoples’ customs which he certainly did not feel. He looked up at the starry sky again. ‘I see no clouds.’

Elijah stared at his bony knees. Then he said uncomfortably: ‘Does the Nkosi remember my bull, which he wanted to buy for two hundred dollars?’

Mahoney remembered. It was a good animal. He had offered several times to buy it, because he needed another bull and Elijah’s land was over-grazed. The old man shifted. ‘I will sell him to you for fifty dollars …’

Mahoney looked at him. ‘Fifty? Why? Is he sick?’

‘Ah,’ Elijah said, ‘he is very sick.’

Mahoney sighed. He did not want to buy more cattle, if he was emigrating. He said, ‘Have no more to do with witchdoctors. Where is this bull?’

‘I have brought him to your cattle pen,’ the old man said.

Mahoney got up resignedly, fetched his rifle, and followed the old man to the cattle pen beyond the eucalyptus trees.

The animal was sick all right. It was very thin, its head hanging. Mahoney knew what was wrong with it; because the native land was overstocked, it had eaten something bad. It would not live. He said wearily, ‘Fifty dollars?’

He counted out the notes. Elijah clapped his hands and took them. Mahoney regretfully walked to the bull’s head. He raised the rifle. There was a deafening crack, and the animal collapsed.

‘Cut it up, and hang it, then put it in my deep freeze, as ration-meat for your family.’

‘Thank you, Nkosi!’

Mahoney looked at the dead bull; the blood was making a tinkling sound. He said, ‘Elijah, your land is over-grazed. You could have sold this animal last year for two hundred dollars.’ He looked at him. ‘Why did you not sell him to me then?’

Elijah looked genuinely surprised, then held up his hand.

‘Nkosi, how much money have I got in my hand today?’

Mahoney looked at him. ‘Fifty dollars.’

Elijah held up the handful of money, and shook it.

‘And if I had sold him to you last year, how much money would I have in my hand today?’

Mahoney stared at him. Then shook his head, and laughed.

The sky was full of stars. From the labour compound came the sound of a drum, the rise and fall of singing. The Company Law brief was spread on his study table, but Mahoney sat on the verandah of the womanless house, staring out at the moonlight, listening to the singing; and, oh no, he did not want to leave his Africa. Maybe he should have stayed a Nature Commissioner in the bush, with people who needed men of goodwill like him; to help them, to judge them, to show them how to rotate their crops and put back something into the land, how to improve their cattle; someone who knew all their troubles, who attended their indabas and counselled them, the representative of Kweeni, Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, Queen, Defender of the Faith … Maybe that was his natural role, to serve – and God knows thev’ll need men like me for the next two hundred years …

‘And if I had sold him to you last year, how much money would I have in my hand today, Nkosi?’ Oh, dear, this is Africa. Today! Today the Winds of Change have driven the white man away. Today we have his roads and railways and schools and hospitals. Today we have fifty dollars … And tomorrow when the roads start crumbling and the sewerage does not work any more, that has nothing whatsoever to do with today.

Joe Mahoney paced his verandah in the moonlight. It was so sad. Africa was dying, but not in the name of Partnership anymore like in those big brave days of Operation Noah, but in the name of Today. And tomorrow the new prime minister will be President-for-Life of a one-party state and there will be no more One Man One Vote, and the roads will be breaking up and the railways breaking down. And he heard Max shout: ‘Then why the hell do you want to give them more power?’

‘Because that’s the only way we can win the war and hang on to just enough!’

But that is only half the godawful story of the dying of Africa, Shelagh. The other half is even more godawful. Because the African counts his wealth in wives and cattle, and in daughters whom he sells as brides for more cattle – his standing is counted by the number of children he has. Twenty years ago there were two hundred million Africans in the whole of Africa, today there are four hundred million, in twenty years there’ll be eight hundred million – and they can’t even feed themselves now.

So what’s it going to be like in twenty years? But even that’s not all. What about the forests these starving millions are going to slash trying to feed themselves? What about the earth that’s going to turn to dust because they’ve sucked everything out and put nothing back? What about the rain that won’t come because the forests are gone? And what about the wild animals? Where are they going to go? The African word for game is nyama, the same word as ‘meat’!

Suddenly, out of the corner of his eye, he saw a man. He turned. Another figure followed. It was Elijah, followed by the witchdoctor. Elijah raised his hand. ‘The nganga wishes to speak with Nkosi.’

Mahoney sighed. He thought the man had gone. ‘Let him speak, then.’

The witchdoctor came forward, dropped to his haunches, his hands clasped. He shook them, muttering, then flung them open. The bones scattered on the ground.

Mahoney stared down at them. And for a moment he felt the age-old awe at being in the. presence of the medicine-man. The witchdoctor looked at the bones; then he picked them up, rattled them again, and threw them again. He stared at them.

He threw them a third time. For a full minute he studied them; then he began to point. At one, then another, muttering. Mahoney waited, in suspense. Then the man rocked back on his haunches, closed his eyes. For a minute he rocked. Then he began. ‘There are three women. They all have yellow hair … But the first woman is a ghost. She is dead …’

Mahoney was astonished. Suzie. …

‘The second woman has an unhappy spirit. This woman, you must not marry.’

Mahoney’s heart was pounding. The witchdoctor could know about Shelagh from Elijah, but not about Suzie.

‘The third woman …’ The witchdoctor stopped, his eyes closed, rocking on his haunches. ‘She has the wings of an eagle …’ He hesitated, eyes closed. ‘She will fall to earth. Like a stone from the sky …’

Mahoney tried to dismiss it as nonsense; but he was in suspense. He wanted to know why he must not marry the second woman.

The old man rocked silently.

‘And you too have wings. You will go on long journeys, even across the sea. You have a big ship …’ The man stopped, eyes still closed. ‘You have spirits with you … But you do not hear them …’ He was quite still. ‘There are too many guns.’

Guns? Mahoney thought. Too right there were too many guns. But ships? He waited, pent. But the man shook his head. He opened his eyes, and got up. Mahoney stared at him.

‘Nganga,’ he demanded, ‘what have you not told me?’

The man shook his head. He hesitated, then said: ‘The Nkosi must heed the spirits.’

And he raised his hand in a salute, and walked away in the moonlight.

Mahoney sat on his verandah, with a new glass of whisky, trying to stop turning over in his mind what the witchdoctor had said. But he was still under the man’s spell ‘This woman you must not marry …’

Suddenly he glimpsed a flash of car lights, coming over the hill, and he jerked. He watched them coming, half-obscured by the trees, and his heart was pounding in hope. They swung on to his gates a hundred yards away, and stopped. He got up. The car door opened and a woman got out.

Mahoney came bounding down the steps and down the drive.

She stood by the car, hands on her hips, a smile on her beautiful face. He strode up to the gates, grinning. ‘Hullo, stranger,’ Shelagh said. He unlocked the gate shakily. She held her hand out flat, to halt him. ‘Why didn’t you come to see me?’

‘You know why.’

She smiled. ‘Very well … What do you want first? The bad news or the terrible news?’

He grinned at her: ‘What news?’

She took a breath. ‘The bad news is I’m pregnant.’

Mahoney stared at her; and he felt his heart turn over. He took a step towards her, a smile breaking all over his face, but she stepped backwards.

‘The very bad news is: I’ve decided not to have an abortion.’

And, oh God, the joy of her in his arms, the feel of her lovely body against him again, and the taste and smell of her, and the laughter and the kissing.

Later, lying deep in the big double bed, she whispered: ‘Ask me again.’

He said again, ‘Now will you marry me?’

She lay quite still in his arms for a long moment.

‘Yes.’

The moon had gone. He could not see the storm clouds gathering. They were deep asleep when the first claps of thunder came, and the rain.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_6a5a7fce-d5db-5a1b-95de-1ea454c793eb)

And so it was that Joe Mahoney got married, stood for parliament, and bought a Britannia cargo aeroplane.

The wedding was the following Friday, before the District Commissioner in Umtali, a hundred and fifty miles from Salisbury. The bride wore red. Nobody was present except the Clerk of Court, as witness, and Mahoney had such a ringing in his ears that he went temporarily deaf. Afterwards they drove up into the Inyanga mountains, to the Troutbeck Inn, where they spent a dazed weekend. On Monday Mahoney got rid of all his cases to other counsel, and started his short political career.

He was standing as an independent. He had posters printed, bought radio and television time. He chose the most prestigious constituency to contest, so he would make the most noise. He made many speeches, visited over a thousand homes, had countless arguments. Not in his wildest dreams did he expect to win; his only interest was the opportunity to tell people the truth. He didn’t expect his message to make him popular. ‘Let’s make it a grand slam!’ the government propaganda cried. ‘Let’s show the world we are a united people!’ Let us BE a united people!’ Mahoney bellowed. ‘White and Black united to fight the enemy!’ He drew good crowds, much heckling, and few votes. On polling day the government won every white seat, and there was cheering.

Thus Joseph Mahoney did his duty, then washed his hands of Africa and prepared to emigrate to Australia; but ended up buying a big cargo aeroplane instead, which happened like this.

In those days there were many sanction-busters, men who made their living by exporting Rhodesian products to the outside world in defiance of the United Nations sanctions against Rhodesia, and Tex Weston was one. He was a swashbuckling American with prematurely grey hair, a perfect smile, and a Texan drawl that he could change to an English accent in mid-word; he owned a number of large freight airplanes which plied worldwide, changing their registration documents like chameleons. Tex Weston made a great deal of money by dealing in everything from butter to arms, with anybody. Today it might be ten million eggs, tomorrow hand-grenades. Tex Weston talked a good, quiet game, and claimed he owned a ‘consultancy company’ in Lichtenstein which devised plans for clandestine military operations for client states and put together the team to do the job. In the Quill Bar, where Mahoney did most of his drinking with the foreign correspondents, they called Tex Weston ‘The Vulture’, and nobody knew whether to believe him, although it was suspected that occasionally the government employed foreign professionals to carry out operations against the enemy in other countries. But it was undeniable that Tex Weston was once a major in the American Green Berets, that he was a supplier of arms to Rhodesia, that he knew all about aircargo, and that the Rhodesian government sorely needed the likes of him to bust the sanctions.