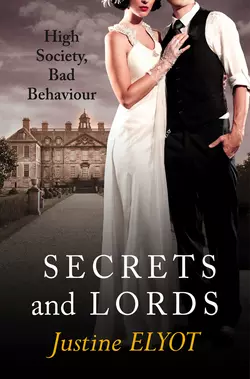

Secrets and Lords

Justine Elyot

The summer of 1920 brings illicit liaisons to stately home Deverell Hall. Lords, ladies, butler and maids all succumb to the spirit of the roaring 1920s as sex and scandal take over.From the author of bestselling Mischief titles ‘Kinky’ and ‘Game’, Justine Elyot’s ‘Secrets and Lords’ is a historical erotic novel that will seduce anyone who loves period drama Downton Abbey and delight fans of The Great Gatsby.Lord Deverell's new wife has the house in thrall to her theatrical glamour. His womanising son, Sir Charles, has his eye on anything female that moves while his beautiful daughter, Mary, is feeling more than a little restless. And why does his younger son, Sir Thomas, spend so much time in the company of the second footman?Into this simmering tension comes new parlour maid, Edie, with a secret of her own – a secret that could blow the Deverell family dynamic to smithereens.

Secrets and Lords

Justine Elyot

(http://www.mischiefbooks.com)

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u2955ee81-2ca4-5d48-b643-5df2c60c7953)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

More from Mischief

About the Mischief (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One (#u2f8c18b7-ecc3-5a7e-afc3-0fc6d3c60067)

Edie Crossland pulled another bramble from her skirt, then put her bloodied finger to her mouth, looking up with dismay at the gathering clouds. Her feet were sore and she’d had enough of it.

It was not that Edie was unused to walking. Her footprints were sunk into the paving stones of Bloomsbury and Holborn many times over, mixed with millions of others. But the London streets hardly compared with this new terrain. The grass verge of the road was bumpy and thick with weeds, and sometimes it disappeared so that Edie was forced back on to the narrow track that led out of Kingsreach from the station.

She could have been sitting up on the box of a pony and trap sent from the Hall, making this trip in relative comfort, carpet bag stowed safely at her feet. But she had not wanted her first view of Deverell Hall to be contaminated by the inane chatter of some fellow servant. So she had deliberately omitted to send them advance warning of the train she would be on, as she had been asked to do. When questioned, she would shrug and assume the letter was lost in the post. These things happen.

Words she did not particularly care to dwell on, given the context in which she had last heard them. The nagging, dark feelings overcame her again and she stopped for a moment, swallowing the bitter taste that came to her mouth.

As if in answer to a silent prayer for distraction from the misery of a stroll that now felt like a death march, there came a distant roar, like an approaching swarm of bees, from somewhere behind her. It was not thunder, although that looked likely, nor could it be attributed to any of the livestock in the surrounding fields. She was far enough away from the railway now to rule out a train.

It grew louder and louder and all she could do was look over her shoulder, transfixed with a vague fear that seemed to go hand-in-hand with her earlier brooding. Her legs weakened just as a gleaming silver fender appeared at the bend of the road, then the cream-coloured body of a motor car. It zoomed past her, expelling great gaseous clouds that made her splutter in their wake.

Of course, she thought with relief, they must have such things in the countryside too. But she had not seen one near the station or anywhere on the streets of Kingsreach until now. It must be heading for Deverell Hall. But to whom did it belong? Maybe to … But no. That was unlikely.

A fat drop of rain landed on her back. She had not thought to bring an umbrella. Sighing, she lowered her head, with its meagre protection of a cheap straw hat, and began to hurry, cursing the fashion for narrow skirts as she shuffled along.

* * *

A further half an hour passed before Edie’s first glimpse of Deverell Hall, and by then she was so thoroughly drenched and utterly miserable that a fairy palace would scarcely have impressed her.

The turrets were bare outlines against the black sky, every finer detail obscured by the driving rain. Edie perceived a great many windows and a prospect that would normally have delighted her. The road led downwards amidst lush green woodland until the landscape opened up, neatly planned and bordered, and the pale ribbon of driveway brought the eye to the stately entrance of the house. She saw fountains at the head of the drive and a hint of some formal gardens to the left side of the building. It was very much as she’d imagined and yet somehow less real.

‘It’s because of the weather,’ she told herself. ‘I never thought of it in the rain.’ In her imagination, Deverell Hall was impervious to the elements.

The sighting gave additional impetus to her journey, although she was fading with weariness, wetness and hunger now. She dragged her aching feet onwards, under the arching trees, for another half a mile.

As she emerged, another blast of engine noise made her jump to the side of the driveway, just in time to be splashed to the knee by the same cream-coloured car. Its driver, a dark-haired man in an expensive coat, cigarette in the corner of his mouth, did not pause even to look at her as he hurtled onwards and away from the estate.

She half-turned after him to remonstrate, but was surprised to see another car coming in the opposite direction, towards her. This one was less flashy, sleeker and quieter. All the same, it made a harsh coughing sound as it slowed down and came to a halt behind her.

A fair-haired man in a uniform wound down the window and stuck his head out.

‘You the new girl?’ he asked.

She nodded, too wet and cold to speak.

His stunningly blue eyes crinkled sympathetically at the edges.

‘You’re pretty much there, but hop in anyway. I’ll take you the rest of the way in style.’

She hesitated, tightening her slippery grip on her bag handle.

‘Come on,’ he insisted. ‘Don’t stand there like a statue.’ He opened the passenger door.

The first flash of lightning over the roof of Deverell Hall made her mind up for her. She scampered over to the other side of the car and climbed carefully inside and pulled the door shut. ‘I’m going to get the leather all wet.’

The man laughed, a glint in his eye. ‘It’s seen a lot worse.’ He put out a hand skinned in a tan driving glove. ‘Ted Kempe,’ he said. ‘His Lordship’s chauffeur. Delighted to make your acquaintance.’

‘Edie,’ she said, putting her own hand in his larger one, enjoying the warmth of the small squeeze he gave her fingers. ‘Edie … Prior.’ Close one, she thought. She had almost forgotten her new name.

‘That’s right,’ he said, unnerving her for a moment, sounding as if he was in the know about her and her situation. ‘I heard Mrs Munn mention you at breakfast. The new housemaid.’

‘Yes. And quite a house. There must be a legion of us.’

‘You’ve never been here before?’

‘No, I was interviewed up in London.’

‘Oh, a London girl, eh? You didn’t fancy getting a job up there then? Most of us here are local.’

‘I … needed a change of air,’ said Edie, feeling leagues out of her depth. She looked away from the shrewd blue gaze of her new colleague, but only succeeded in looking straight into the reflection of his face in the window. He watched her and, for an uncomfortably long moment, said nothing.

‘We all need those from time to time,’ he said eventually. ‘Well, Edie, you’ll be wanting to get out of those wet things. Better get you to the house.’

The way his look lingered over her after the mention of ‘wet things’ made the back of Edie’s neck prickle.

He was thinking of her peeling down her clinging damp stockings, unbuttoning the water-stained blouse. Her underwear was silk, not suitable for a servant girl, but she had not quite been able to bear the thought of wearing coarser fabrics next to her skin. Not yet.

No sooner was that thought in her mind than it was succeeded by other, even more disreputable imaginings. How would it feel to have the chauffeur’s leather-gloved hands on her, disrobing her, moving slowly and smoothly over the curves of her body?

Stop it. Just stop it.

Mercifully, he put his foot on the accelerator and drove, his attention diverted to the road.

‘I don’t know what your last place was like but you’ll find the servants’ hall here a very tight-knit bunch,’ he said. ‘A bit like a secret society. It’s hard to get in, but, when you’re accepted, you become a member of the family.’

‘Oh dear, that sounds rather intimidating. I suppose I shall be sized up. I hope I’m not found wanting.’

He gave her a sideways smirk.

‘Can’t imagine why you would be,’ he said gallantly. ‘Never mind the others, but keep the right side of Mrs Munn. She’s the power behind the Deverell throne. If she doesn’t take to you, you’ll never prosper here.’

‘Gosh, you really aren’t inspiring me with confidence, you know.’

He drew up at the huge front steps, pulled the handbrake and turned to her, frowning in confusion.

‘You sure you aren’t some kind of governess or something? I’ve never heard a parlourmaid talk like you do.’

Edie held her carpet bag tighter. ‘And how’s that?’ she asked with a nervous laugh. She had to watch her little quirks and mannerisms of speech. If possible, she must pare her conversation down to the bare minimum necessary for communication.

‘Ladylike,’ he said. ‘Are all the London slaveys like you?’

‘No, not at all. Well, perhaps some of them.’

He smiled. ‘I might consider moving to London, then.’

Edie’s wet clothes suddenly felt too tight, especially around the chest, and her toes curled inside her boots. He was flirting with her. And he was rather attractive, even if he was only a chauffeur.

‘Oh,’ she said, tongue-tied, looking all around her for extra luggage that did not exist. ‘Well. Thank you for the, for, you know, driving me.’

‘A pleasure,’ he said. ‘No, don’t open the door yourself. You’ll do me out of a job.’

He got out into the rain and ran around the front of the car to the passenger side.

Edie, toting her carpet bag, put her feet out of the door, preparing to stand.

‘Now remember, Miss Prior,’ he said, leaning down and speaking softly, ‘if you ever need a friend in this place, Ted Kempe’s your man. Do you promise you’ll remember it?’

She nodded. ‘I promise.’

‘One more word,’ he said, looking over his shoulder as if he expected a legion of eavesdroppers to have materialised from the sheets of rain all around. ‘Watch Sir Charles. Don’t let him …’ He shook his head. ‘Just watch him, all right? Servants’ entrance is round the back.’

Edie had almost made the ridiculous mistake of walking up the front steps.

‘I’d see you inside, but His Lordship’s ordered the car up to take him into Kingsreach. Good thing he sits in the back – you’ve left the passenger side all wet.’

She shot Ted one last breathless nod and a smile, then ran around the side of the building, looking for the way in.

It took a long time to find, given the vastness of the edifice. Edie looked in at every window on her way round, but saw only empty room after empty room until she arrived at the rear of the house. A kitchen garden lay a few hundred yards off, beyond a low wall. Surely the kitchen must be close to that.

She scrambled along a gravel path, desperate now to be out of the rain. A crash of thunder accompanied her descent into a basement area that belched heat up the stairs she squelched down. In the corner a large door stood invitingly open.

Shelter, at last. She stood with her back to the wall, blinking raindrops out of her eyes. Once they were gone she realised she was not alone in the room. The clatter of steel and crockery that filled the room stopped instantly. Two girls, their faces crimson from their endeavours within the hot room, and neither of them much above fourteen, stood against a huge Belfast sink, staring at her.

‘Are you the new girl?’ one of them asked.

Edie nodded.

‘Filthy weather,’ she said, hugging herself.

‘Mrs Munn thought you weren’t coming. You never wrote. She’s been cursing your name all morning,’ said the stouter of the two girls.

‘You’d better go and find her,’ added her companion.

‘How shall I do that?’

Both girls shrugged and turned back to their washing up.

Tight-knit, that was what Ted had said. Meaning ‘unfriendly’ apparently.

Here, in this dark scullery, Edie’s splendid plan did not seem so splendid any more. It had seemed so easy when she had huddled with Patrick and his sisters, evening after evening, discussing and fine-tuning. Now that she stood here, in Deverell Hall, it had immediately assumed a new character with an objective that appeared insurmountable. Failure seemed so likely that she thought about leaving then and there.

A red-faced woman in a dusty cap and apron appeared in the inner doorway and brandished a rolling pin at her. ‘Whatever have we got here? A drowned rat from the garden?’

‘I’m Edie Prior, the new parlourmaid.’

‘Well, what are you doing skulking in here with these two ne’er-do-wells, then? Mrs Munn’s got no hair left, she’s torn that much of it out over you. Come on.’

Edie hurried after her, through a cavern of a kitchen that seemed to swarm with bodies rushing this way and that, and out into a cool, tiled hallway.

‘I’m Mrs Fingall, the cook,’ said the woman. ‘You’ll want to keep civil with me, because I’m the one as feeds you.’

‘Oh, I hope I’m always civil,’ said Edie.

The cook stopped and stared at her, hands on hips. ‘You jolly well do, do yer?’ she said. She knocked on a door. ‘Mrs Munn’s office,’ she said confidentially.

Edie was relieved to be out of the heat and clash of the kitchen, which she had found unnerving. All the same, perhaps she had just left the frying pans – literally – for the fire.

‘Come in.’ The voice was low and calm, giving the lie to what everyone had said about the occupant tearing out her hair.

‘Miss Prior, the new parlourmaid,’ said Mrs Fingall, jabbing her in with two fingers between her ribs.

An angular woman sat at a desk, poring over a ledger.

She looked up at Edie, expressionless.

‘Thank you, Mrs Fingall. Would you fetch Jenny, please?’

Edie wondered why she had never considered the reality of the role she had thrown herself into. She had to converse with people, convince them of her background in domestic service. The best she could do was mimic her friend Josie McCullen, who worked as a daily girl in a house in Pimlico. She had shown Edie how to black-lead a grate and polish silver, but how to be another person … that was a rarer skill.

‘Why did you not write?’ asked Mrs Munn. ‘I’d have sent Wilkins to meet you with the trap.’

‘Oh, did you not receive my letter?’ muttered Edie, finding the barefaced lying more difficult than she had expected.

‘No, I did not. You were interviewed by Mrs Quinlan from the London residence?’

‘Yes.’

‘I suppose you were hoping for a job in Belgrave Square.’

‘I am perfectly happy to work here.’ As an afterthought, she added, ‘ma’am’, finding the word so odd that she had to suppress an embarrassed smile.

Mrs Munn was right, though – Edie had assumed that her application to work for the Deverell family would result in a place in their London residence. The fact that the only opening was at Deverell Hall had been the first snag in the plan. It was only thirty miles from London, but it seemed that a huge ocean stood between Edie and her familiar urban world.

Mrs Munn picked up a piece of paper and sneered at it.

Edie, recognising the character her friend’s mother had written for her, felt her heart skip.

‘Your last place seems to be a respectable house, if not one of the best in society. You will find the scale of things here somewhat different. It may alarm you at first, but if you keep a cool head and attend to your duties first and foremost, you will soon settle.’

A timid knock at the door interrupted Mrs Munn’s flow.

‘One last thing,’ she said, before bidding the knocker enter. ‘There must be no communication beyond that which is strictly necessary between you and the gentlemen of the house. Do you understand me? None whatsoever.’

‘Of course, ma’am. By “gentlemen of the house”, do you mean …?’

‘His Lordship’s sons. The elder in particular.’

‘I see.’

Mrs Munn raised her eyebrow. ‘I hope you do.’ She looked past Edie at the door. ‘Come in, Jenny.’

Jenny was a mouse in human form and parlourmaid’s black-and-whites. She hid in a corner while Mrs Munn instructed her to show Edie her room and help her with her uniform prior to a grand tour of the house.

The servants’ staircase seemed to go up and up for ever. Conversation – a desultory affair – died out after the first flight and, from then on, nothing was heard but puffing and the echo of boots on stone.

‘You’re a London girl, then?’ said Jenny, once they were at the very top of the building, in a low-ceilinged, dark room containing four beds and little else.

‘Yes,’ said Edie, moving instinctively towards the window, against which the rain beat so dismally that little could be seen outside.

‘Most of us here are from Kingsreach and hereabouts. We’ve grown up on Deverell land. You don’t know anything about us.’

Edie turned to the plain little creature, surprised at the edge of resentment in her voice.

‘We’re all of us in the same boat, aren’t we?’ she said. ‘Service. What does it matter where we learned to wax a floor, so long as we wax it well?’

Jenny shrugged and pointed to some folded clothes on the bed furthest from the door. ‘Uniform,’ she said. ‘Hope it fits. You’ve got a lovely figure.’

‘Thanks,’ said Edie. She tried a smile, but the wistful look on the girl’s face caused it to misfire.

‘He’ll have an eye for you,’ said Jenny.

‘An eye for me? Who will?’

‘Charlie Deverell. He tries it on with all the pretty maids.’

‘Well, he won’t try it on with me,’ said Edie stoutly, moving behind a screen and unbuttoning her blouse.

‘Yes, he will. You’re ever so pretty. Even prettier than Susie Leonard, and she had to leave in disgrace when he got her into trouble.’

‘Heavens!’ Edie’s fingers paused on the faux-pearl buttons. This must be what Mrs Munn was driving at before.

‘He denies it was him, but everyone knows it was. Susie didn’t even have a sweetheart. And I’ve seen her with the baby – got his eyes, she has, and his dark hair.’

Dark hair. The man driving the car.

‘Well, I’m no fool and no flash Harry is going to seduce me,’ said Edie briskly. She allowed room for a little pause, removing her skirt in the silence, before changing the subject. ‘What do you think of Lady Deverell? She’s new to the house, isn’t she?’

‘Not so new. Been here a year now.’

‘Is she nice?’

‘My ma always says if you can’t speak well of someone, don’t speak of them at all.’

Edie laughed uncomfortably, her face flushing hot.

‘She’s awfully glamorous, though, isn’t she?’ she said, putting the black dress on. It was a little tight under the bust but, apart from that, a snug fit. ‘I saw her on the stage in London, in one of Mr Bernard Shaw’s plays. She was quite magnetic.’

Jenny sat down on the side of one of the beds.

‘London,’ she said, as if intoning a magic spell. ‘I’d so love to visit the theatre one day. I mean, I’ve seen the Kingsreach Players, everyone has, but the proper theatre. All red and gold, with balconies and plaster cherubs. That’d be smashing.’

‘Well, I suppose you will one day,’ said Edie, trying to steer the conversation back to her preferred subject. ‘But Ruby Redford won’t be treading the boards.’

‘Hush, you’re not to call her that! It’s Your Ladyship and Lady Deverell now. She hates anyone mentioning her past. She’s a bit sensitive about it. Well, more than a bit. You’re best off forgetting it, if you’ve seen her on stage. Not that you’ll get to speak to her much. She don’t have much to say to the servants.’

‘Really? I thought she might be a good mistress to have – since she’s closer to, to our class than most of the gentry.’

‘The opposite. Everyone says the first Lady Deverell was a real smasher, kind and sweet. She gave extra half-holidays when the weather was nice sometimes, and she always asked after your family. This one don’t even acknowledge you. Like I say, she’s funny about her past. She thinks talking to us like we’re people shows her up, I reckon. But we all know that that’s the mark of a someone who ain’t a real lady. But I mustn’t talk like this.’

A flicker of fear had crossed Jenny’s pale face.

‘Not when I don’t know you. You won’t repeat any of this, will you? Do you promise? Not to a soul?’

‘Of course not. What has passed between us is in strict confidence. You may be sure I will observe it.’

‘Gaw, you London girls talk proper, don’t you?’ Jenny’s momentary anxiety had turned to a curious admiration.

‘Oh, not really, I studied my mistress and her daughters at my last place and tried to imitate them. It’s a habit. I expect I shall grow out of it here.’

Jenny stood again, seeing that Edie had tied her apron and pinned on her cap.

‘Well, might be for the best,’ she said. ‘You’ll get teased for it downstairs. Come on. I’m to help you find your feet today. What would you like to see first?’

‘Well, I hardly know. Should we do a wing at a time?’

‘Good idea. Let’s start with the West Wing.’

They sallied forth, black-and-white neatness in duplicate, to the servants’ staircase.

‘The West Wing’s used for visitors and children. We spend less time on it, especially since there aren’t any Deverell children just at the moment. The ground-floor rooms aren’t used at all.’

The West Wing was indeed, though splendid, a little neglected; its carpets threadbare and its wainscots dusty in places. The unused downstairs apartments were empty of furniture – huge, high-ceilinged bunkers with ornate plaster mouldings and pictures behind dust sheets.

Edie found it quite sinister and was glad to cross the courtyard to the East Wing, which contained the family rooms.

On the upper floor, the younger son and daughter of the house kept their suites.

‘This is Sir Thomas’s rooms,’ said Jenny, briefly opening a door into a neat and unusually plain chamber. ‘We needn’t go in.’

‘Who is Sir Thomas?’

‘Lord, you really don’t know nothing, do you? He’s the younger son. He joined the Army and did very well for himself at first, but after getting shot in the war, he wanted out. Lord Deverell had to buy him out, even though he was injured. Walks with a limp now, always will.’

‘Does he have another occupation now?’

‘No, nothing.’ Jenny shook her head. ‘He can’t settle. They say Lord Deverell’s at his wits’ end with him.’

‘What is he like?’

‘Well, I don’t know him, really. He keeps himself to himself. Spends a lot of time at the races, or out with the dogs.’

They reached the next door.

‘Whose rooms are these?’

‘Lady Mary’s, but I wouldn’t be opening them if I didn’t know she’d gone out. She gets wild if anyone disturbs her in her room.’

Jenny opened them with a furtive, mysterious air then stepped a little way into the light, airy chamber. Everything seemed to sparkle in there. Edie thought, with a sickening pang, of her room at home in London. She had the same cut-glass scent bottle on her dresser. The silver-backed hairbrush looked familiar too, even if Edie’s was not monogrammed like Lady Mary’s. Fresh cut flowers stood on the bedside table and the chest of drawers, and a tangle of stockings and scarves were strewn all over the bed.

‘I suppose she was trying to decide what to wear tonight,’ said Jenny with a laugh. ‘She’s fearful fussy. Ask Louise, her maid. She leads her a merry dance, she does.’

‘A hard taskmistress?’

Jenny whispered, ‘A spoiled little madam,’ and then put a hand to her mouth, giggling guiltily.

‘What is happening tonight?’

‘Didn’t Mrs Munn say? A big dinner, some visitors from London. I don’t know who they are but I think they’re supposed to be important.’

Another surge of panic rose through Edie’s stomach.

‘Will I have to serve them?’

‘I shouldn’t think so, not your first day.’

She exhaled gratefully.

‘I wonder if Lady Mary will announce an engagement soon,’ Jenny prattled on. ‘They say she’s got ever so many admirers in London. But, like I said, she’s fussy.’

‘Neither of the sons are married?’

Jenny sighed. ‘No, and it don’t look likely neither. One’s a womaniser and the other’s a recluse. Come on, shall we go downstairs?’

The windows were bigger on the floor below and the fittings notably more elaborate.

‘Sir Charles’s rooms,’ whispered Jenny, her hand on an antique gold door handle.

‘Should we?’ Edie was suddenly nervous. ‘What if he’s in there?’

‘He went to town,’ she said. ‘With Lady Mary. Come on.’

‘There could be a woman in there.’

Jenny let out a peal of merry laughter. ‘You ain’t met him yet and you’ve got the measure of him already. Come on.’

She opened the door.

No woman was hidden behind it. The rooms were magnificent, crimson and gold, but the style was decidedly masculine and his valet had not yet cleared away his shaving things from the basin in the little bathroom. Edie felt possessed by a sense of the man who used these rooms; the scent of his cologne, mixed with a faint aroma of smoke, crept into her and took up residence in the corners of her consciousness. A dressing gown hung carelessly on a bedpost and his slippers were in the middle of the floor.

‘Who is his valet?’ Edie wondered aloud. ‘Should he not have tidied these things?’ She was proud of herself for remembering that aristocratic men all had valets. Although the social circles she moved in at home were mixed, they rarely involved lords and ladies.

‘He is between valets at the moment,’ said Jenny. ‘His last one resigned a few days ago. He is sharing with Sir Thomas until they can hire a replacement.’

‘Why did the last one resign?’

Jenny pinched her lips and shook her head.

‘I don’t know.’

But Edie thought that Jenny was concealing some further knowledge.

Moving towards the other side of the room, Edie saw a book on Sir Charles’s bedside table and was consumed with curiosity to know what kind of thing this man enjoyed reading.

‘Oh!’ she said, picking it up. ‘The Moon and Sixpence. I have read this.’

‘Put that down,’ exclaimed Jenny, rushing over. ‘Don’t touch a thing.’

‘We shouldn’t be in here, should we?’

‘No,’ she admitted. ‘Come on.’

She dragged Edie out by her elbow, but Edie was already wondering to what extent Sir Charles might identify with the book’s hero, his namesake, a man who abandons his established life to pursue an impossible dream.

‘His Lordship,’ she said, flapping her hand at another door without opening it, following up a moment later with ‘Her Ladyship’.

‘Oh, can we not go in?’

‘Her Ladyship is in. No, we cannot.’

‘I would so like to see her rooms.’

‘Well, you can’t. So there. Come on, let’s go to the ground floor. Like reading, do you?’

She opened a smaller door at the end of the corridor. It led on to a large gallery, looking down into a treasure trove of bookcases.

‘Oh, a library! Oh, this is huge. How wonderful.’

It occurred to Edie that perhaps she should not be displaying such raptures in her role as a housemaid. But surely housemaids might like to look at a book or two now and again?

‘Do a lot of reading, do you?’ asked Jenny, leading her down the steps to the main room. ‘You can’t have been very busy in your last place.’

‘Oh, I was, but I read on my days off, you know.’

‘Must have been nice for your family.’

‘They didn’t mind.’

Edie barely registered Jenny’s disparaging tone, too engrossed in the endless spines of gold-embossed leather that lay behind the glass doors of each cabinet.

‘At least they had the shelves turned into cupboards,’ said Jenny with a sniff. ‘I hated dusting all those perishing things. Lord Deverell thought we were going to ruin them just by touching them so he locks them away now.’

‘He is a keen scholar?’

‘No, not really. I suppose they’re worth a few bob, that’s all.’

Edie shook her head. The idea of valuing books for their monetary worth was quite beyond her. At home, in her room, her books lay in piles, higgledy-piggledy, with dog-eared pages and dusty jackets, but they were the landscape of her life, to be kept round about her, not shut away in cages.

She was reluctant to leave this wonderland, but they had to move on regardless, to a breakfast room in modern pinks and pale greens, then a comfortable sitting room and a brace of cold gilt state rooms, until they were at the central part of the house.

The splendour of these rooms left even Edie open-mouthed – as huge as the British Museum galleries and several times more ornate. She craned her neck up at pricelessly painted ceilings and then let her eye move downwards to works of Tudor and Stuart art, interspersed with gold leaf twining all over everything. The impression was sometimes sumptuous, sometimes intimidating. It was nothing like a home. How did people conduct their daily business in rooms like these? Reception rooms opened on to more reception rooms; then there were morning, drawing, breakfast and dining rooms, each with a different colour scheme and each groaning with antiques that would need careful dusting and cleaning, over and over again.

Seeing everything with a maid’s eye, Edie came to resent all the magnificence, much as her artistic senses were impressed. But really, who needed all this?

Out of the wings, Edie and Jenny now ran across several of their colleagues, all working hard to get the grandest rooms of the house into a fit condition to receive guests. Flowers were being arranged, feather dusters wielded and, in the dining room, a French polisher attended to a scratch on the table.

‘They’ll cover it with a cloth,’ whispered Jenny, whisking Edie past. ‘But Tilly Gresham got in terrible trouble for it all the same.’

A tall, thin, fastidious-looking man in a dark suit and white gloves appeared to be directing the carrying up- and down-stairs of a number of ornamental urns.

‘Jenny,’ he said. ‘Is this the new girl?’

‘Yes, Mr Stanhope, Edie Prior.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Miss Prior.’

‘Likewise,’ said Edie, unsure whether or not to curtsey. She decided against it.

‘Well, I’m sure you have work to do,’ said Stanhope after an awkward pause. ‘On such a day as this. And if not, I’ll be asking Mrs Munn why not.’

‘Don’t mind him,’ muttered Jenny, leading them to the back stairs. ‘He gets himself a bit worked up when there’s a big do. He’s the butler, if you didn’t know.’

They descended to the depths of the house once more, where Jenny collected a trug of cleaning materials before showing Edie to the room where Mrs Munn had ordered them to work.

They passed along endless yards of corridor, under the baleful eyes of the Deverell ancestry, up and down the back stairs and through that busy, bustling series of reception rooms before arriving at the well-named Green Drawing Room.

It was very green, and very golden, and very velvety and very cold – in style rather than temperature. Everything in it was heavy and sharp-cornered. When Edie considered her family drawing room in Bloomsbury, with its cheerful patterns and fringed shawls all over the place, it could not have been more remote.

‘Do people come in here to relax?’ she asked, looking over a two-hundred-year-old spinet in the corner of the room.

‘People hardly come in here at all,’ said Jenny vaguely, sorting through rags and polishes. ‘It’s not much used. Here, I’ll wax the wooden furniture and you can polish the mirror there.’

Edie accepted a rag and a tub of metal polish and made a start on the heavy ormolu-framed square mirror that stood over an unused fireplace.

They worked silently and diligently until Edie was drawn to the window by the sound of a car drawing up in the drive. She would not have admitted it to herself, but she was hoping for a glimpse of Ted.

The car was not the one she had ridden in earlier, though. It was that same sleek, cream-coloured monster that had twice passed her on the road.

The rain had abated and its driver got out on to wet gravel, looking up at the house windows as he did so. Edie took a swift step back, her heart pounding. Why did she not want to be seen? Because this must be Charles, the rake of the Deverell’s, and she had no wish to draw his attention to her.

He was pristine in a pinstriped blazer over light-coloured waistcoat, shirt and trousers. His dark hair was immaculately cut and he was clean-shaven. He didn’t wear a hat, and Edie approved of this, for she had no taste for the current fashion for straw boaters on men.

His eye was soon drawn away from the house, and he went to the passenger side to open it for a young woman.

‘Who is that?’ asked Edie, and Jenny came to look over her shoulder.

‘Lady Mary. Oh, don’t look. Sir Charles will see you.’

‘She is fearfully lovely.’

‘Yes. Come away.’

But a creeping fascination had overcome Edie, who noted that Mary was exceptionally fashionable and glamorous in a calf-length beige skirt, a lace-collared blouse and a loose belted jacket. Her hat was low on her brow over dark, shiny bobbed hair and she wore three long strands of pearls.

Jenny tried to tug her away but to no avail. Edie watched Charles take Mary’s arm to help her up the steps, then – disaster! He looked directly at her window. Her throat tightened and she tried to move away but she felt held there by the keen penetration of his gaze. It only lasted a moment, before Lady Mary slapped him on the elbow, as if in reproof, and he turned back to her, laughing.

But a moment was enough. Edie had been noticed, and now she felt like a marked woman.

Chapter Two (#u2f8c18b7-ecc3-5a7e-afc3-0fc6d3c60067)

Her stomach in knots, she returned reluctantly to her mirror. The surround was devilishly full of sharp points and curlicues and polishing it was a more arduous task than she had imagined.

‘Lady Mary, the spoiled beauty. Shouldn’t she be in London for the season?’ she asked, resuming her labours.

‘So many questions,’ said Jenny briskly, putting the polish back in the trug. ‘Oh, lor’. Oh, dear me, no.’

Edie looked around, putting her materials down on the mantelpiece as a stricken-faced Jenny drew nearer.

‘What is it?’

‘You don’t never use polish on the ormolu. Didn’t you know that? It damages it. You can only dust that down.’

‘Oh, I had no idea,’ said Edie, her hands flying to cover her mouth.

Josie McCullen had never mentioned ormolu. Only silver and plain brass. Oh, there were so many gaps in her domestic education. She would be making huge mistakes all the livelong day.

Jenny sighed. ‘It’s probably all right,’ she said. ‘But that polish strips the gilt away. The most you can do is dab it with meths and a soft cloth, and then only when you can see some corrosion. Let me look a bit closer. Oh. Oh, dear.’

A tiny scrap of one of the curlicues had dulled, a tarnished patch amidst the bright gilt.

‘We’ll have to tell Mrs Munn,’ Jenny decided. ‘She’ll know how to fix it.’

Mrs Munn did know how to fix it – or, at least, she knew a restorer who did – but she still pursed her lips and tapped her fingers against the mantel in the servants’ dining hall when the maids made their confession.

‘It’ll have to come out of your wages,’ she told Edie. ‘I can’t imagine how you could be so careless. What kind of place have you come from, where they had no ormolu in the house?’

‘I’m sorry,’ repeated Edie, feeling like a spot of grease on the floor at Mrs Munn’s feet. ‘I only had charge of the silver and brass at Mrs Winchester’s.’

‘Perhaps we should keep you to the corridors and anterooms,’ mused the housekeeper. ‘But if I can’t use you where I see fit, then what’s the good of having you?’

‘Please, I promise to do better,’ pleaded Edie, close to tears.

‘Come on, have a heart, it’s her first day.’

The male voice from the doorway belonged to Ted Kempe.

‘I’ll thank you to keep your opinions to yourself, Kempe,’ snapped Mrs Munn. ‘This matter does not relate to motor cars, or any other area to which you can be expected to contribute.’

Ted shrugged. ‘We’ve all made mistakes, the first few days of a new place. Haven’t you, Mrs Munn?’

‘Yes, and I was properly corrected,’ she hissed, clearly unappreciative of the chauffeur’s attempts to pour oil on the troubled waters. ‘And thankful for it. You may go, Edie, and I will expect a substantial improvement on this performance tomorrow.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Munn,’ whispered Edie, and she ran from the servants’ hall, regardless of the fact that it was almost dinnertime, and into the darkening kitchen garden where she sat herself down on a low wall and burst into tears.

This was all a crazy, ridiculous mistake.

She would pack her bags, go back to London, back to papa and back to her circle of friends. Service was perfectly horrid and so was Deverell Hall and so was everything.

Except Ted Kempe. He was not horrid. He was kind and handsome, and he approached her now from the scullery door, uniform cap in hand, smile of rueful sympathy on face.

‘Hey, you’ll be missing your supper,’ he hailed her, coming closer and perching at her side. ‘That won’t do.’

‘Oh, please, leave me be. I’m not fit for company and I can’t bear to go in there and have all those eyes on me, knowing what a useless creature I am.’

‘Don’t be daft. They don’t think that at all. Here. Dry your eyes. I’m sure you don’t need to blow your nose, a ladylike person such as yourself but …’

He handed her a handkerchief and she giggled woefully.

‘Actually, I do,’ she said. ‘But I won’t, not in front of a gentleman.’

‘First time I’ve been called that,’ he said, beaming brightly. ‘I’ll treasure it.’

‘Well, you are, you know. Thank you for standing up for me in there. You didn’t need to do it.’

‘Mrs Munn needs reining in a bit sometimes, that’s all. She breathes fire on everyone and everything, not realising that, half the time, it just ain’t needed. You don’t need the same amount of flames for a paper tissue as you do for a bloomin’ oak tree.’

Edie laughed again. ‘Am I a paper tissue then?’

‘More like a paper rose,’ he said gallantly.

‘Oh, give over,’ she said, rather proud of herself for replicating one of Josie McCullen’s favourite expressions.

‘So, are you coming in? Get yourself some food, it’ll cheer you up. Steak and kidney pudding tonight, one of Fingall’s specials.’

Edie tried a few moments more of token resistance but ultimately she could not resist Ted’s blend of charm and solicitude. She followed him back into the house just as the first spots of new rain fell on already sodden ground.

* * *

‘I have my reservations about this.’ Mrs Munn hardly needed to voice the words; her face said them for her. ‘But Carrie really isn’t well enough to serve at table tonight. I don’t have anybody else. I’m counting on you.’

‘Thank you, I won’t let you down,’ Edie assured her, though she hoped she wouldn’t be asked to swear on her life.

Dinner in the servants’ hall had been surprisingly heartening, most of the staff having secret sympathetic smiles for her for her misfortune in getting on Mrs Munn’s bad side so soon. Nobody asked any awkward questions and only a couple of the girls looked askance at her when she came out with an overly London turn of phrase.

She had been sent on an errand after tea, a kind of test of her knowledge of the house’s geography. Unfortunately she had failed.

The first footman, Giles, had found her wandering about in the East Wing, wringing her hands as she passed the same door for a third time.

‘Hey,’ he said, appearing from behind a door – one of the family bedrooms, if she wasn’t mistaken. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘I don’t know where I am,’ she said helplessly. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Let me show you back to the basement. Too many stairs in this place, that’s the problem. Don’t worry. I was the same when I started here.’

‘How long have you been here?’ she asked, following him along yards and yards of crimson carpet patterned with gold fleurs-de-lys.

‘Couple of years,’ he said vaguely. ‘Straight after I demobbed.’

‘Gosh, were you in the trenches?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s a bit different to that here.’

He turned around and gave her a very odd smile.

‘Yes. In some ways,’ he said.

No more was spoken until they reached the kitchen.

But now Edie was in best black-and-whites, listening to Mrs Munn’s pep talk on how to behave when serving dinner guests.

She felt like breaking in and telling the woman that she’d been to enough dinners to know what was done and not done, but she had to endure the sermon without interruption.

In the background, Ted was eating a chicken leg and grinning at her.

It was too bad of him – Edie was flustered enough already and when he winked at her she had to look away and block him from her mind.

She was already a little feverish at the prospect of being in the same room as Sir Charles again. What was this peculiar fascination he held for her? She had never been drawn to such characters before. The thought that Jenny might be accurate in her surmise that he would notice her and try to seduce her made her feel alternately hot and cold all over.

By the time Mrs Munn’s talk was through, Edie felt an uncomfortable band of sweat beneath the elastic of her cap. All she could think of was the way he had looked up at her from the forecourt below, a blend of curiosity and something else, something she had never thought much about because it frightened her.

The trap. The thing that caught so many good women and took them out of the world, where they could have forged a path of their own.

She thought about this all the time she helped to lay the table, placing forks within forks and spoons below spoons. Jenny showed her how to fold the napkins ‘the Deverell way’ but she was clumsy and could not manage to pleat them properly, so she was sent to set out the glasses instead.

Cars had been pulling up outside the house all evening. Ted Kempe had made several journeys to and from the station as well.

She could hear the muffled voices from the reception room beyond and she tried to make out what people might be saying, but it was too hard. Now and again she heard the fruity, theatrical tones of Lady Deverell, followed always by laughter. This made her knees weaken. Sir Charles’s voice was distinctive too, but he didn’t seem to amuse quite as much.

Stanhope, the butler, sailed into the room just as the last piece of crystal was set in place.

‘Take your positions,’ he muttered.

Like frilled centurions, Edie and Jenny stood guard by the table, with four other servants, while Stanhope threw wide the large double doors on the far side of the room to announce dinner.

There were twenty-four at table and Edie found a vicarious interest in looking at the gowns and jewels as they shimmered past, adorning pale aristocratic flesh.

She did not know the woman on Sir Charles Deverell’s arm, but she saw him cast the quickest little dart of a glance in Edie’s direction before pulling out his companion’s chair.

Lady Mary was gorgeous in royal-blue satin overlaid with net, beaded and jewelled at the neckline and on the sleeves. She was transparently a female version of her brother, his dark looks softened and made sleek on her smaller canvas.

The man who limped in behind her must be the other brother, Sir Thomas. He had a thin moustache that did not look as if it had much more growth in it and his eyes were tired and hooded.

And then – yes, it could only be Lady Deverell, in sweeping floor-length emerald silk that swished about her and was overlaid with a cloud of black tulle. The emeralds at her throat and in her tiara set off the deep red of her hair, while swirls of black beads decorated her bodice and the hem of her skirts. She was like a creature from another world, and yet she was so familiar that Edie’s throat tightened and ached.

Lord Deverell, at her side, was a grizzled, faded nobody.

Edie felt a blush of transferred shame, as if all the gossip that must inevitably be attached to their marriage had infected her. But she was nothing to do with it.

The guests were mainly elderly, it seemed, with a sprinkling of younger people, perhaps their children. Everybody was talking about the grouse and salmon seasons, so perhaps they were fellow landowners from the local area.

She could not take her eyes off Lady Deverell, who smiled as brightly as the electric lamps at the theatre, dazzling the candlelight into a dim second place. But her smile was strange, not quite natural. At times it almost looked as if it wavered at the edges of her lips and then it found renewed purpose and flashed again in its full glory. Her eyes wandered, frequently settling on Sir Charles, who seemed to know a lot about their baffling topic of conversation and held the floor with effortless authority. She leant towards him when he cut across or contradicted his father and gave him an extra gleam of her teeth. She was amazingly beautiful.

Lady Deverell looked towards her, sharply, as if she had noticed Edie’s unbroken gaze. Edie dropped her eyes and looked instead at Jenny, who signalled that they were to serve the soup which had been brought up from the kitchen.

When she reached the table, Lady Deverell was still looking at her, but not hostilely now. She had a distant, dreamy kind of look upon her face, but it disappeared when somebody asked her about her jewels, whisking her back into the social slipstream.

Edie had been consigned to the end of the table, serving six of the elderly guests, but even at this distance Lady Deverell’s radiance reached out to her. Her hand shook and she could barely breathe.

‘Be careful, girl,’ snapped a dowager in pink and black lace.

A splash of soup had escaped the ladle and spotted the cloth.

‘Oh, I am so sorry,’ blurted Edie, desperate not to draw attention to herself.

The tiny contretemps had reached the notice of Sir Charles, however, for Edie became hotly conscious of his eye upon her. If only he would look away.

She avoided his gaze as studiously as she could, attending to her other guests, but when she glanced back up, he still watched her.

Her grip on the ladle slipped and it fell with a clatter back into the tureen.

Lord Deverell frowned and several ladies tutted, their jewels flashing as they turned to grimace at each other.

Edie apologised again, on the verge of tears. This was all a terrible mistake. She would catch the mail train back to London and tell papa she was sorry, she had been wrong and he had been right, could she now take back her old life, please?

‘Leave her be.’

The voice was rich and commanding and it belonged to Sir Charles.

‘She is new, I think. Isn’t that so?’

Edie nodded, wanting to be anywhere but this place, with all these eyes upon her.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, then. First-night nerves. You know all about them, don’t you, mama?’ The way he said this, with a sneer, to Lady Deverell made Edie gasp, and she was not alone.

‘Charles!’ Lord Deverell reproved his son.

‘Sorry, did I speak out of turn?’ He sat back, dabbing his napkin at his lips with an insolent air.

Lady Deverell was flushed but it only made her more beautiful. She levelled a combative stare at Sir Charles and shook her head.

For a moment there was silence while stepmother and stepson locked everybody else in the room out of their mutual tension, then somebody complimented the soup and everybody rushed to agree.

Edie, for the moment, was forgotten, and she melted back into her place with gratitude, waiting for the first course to be finished.

The fever that had affected her on her first sighting of Lady Deverell eventually wore off and Edie was a better mistress of herself when called upon to serve the other courses. She was thankful to be at the end of the table furthest from the family, able to watch them without having to get too near.

Lady Mary sulked about coming back from the London season too early and missing the best closing balls, while Lord Deverell heavy-handedly reminded her that there was a good reason for that, which made her sulk all the more.

Edie exchanged a look with Jenny that asked, ‘What reason?’ Jenny responded with a tiny shrug.

Conversation was far from lively. Sir Charles occasionally attempted to stir things up with a sly barb or two, but nobody seemed to be in sufficient spirits to react in the way he wanted. Sir Thomas barely spoke at all, glaring down at his plate as if he saw the face of a mortal enemy in it.

Edie was lulled by the low murmurs, the scraping of knives and forks on fine china, the low light and the ambient warmth into a kind of daze. Her legs and feet ached and her head was so fuzzy now. She had been awake since five o’clock in the morning and she had walked as many miles inside the house as she had outside it.

Could they not just finish their meal quickly and let her go to bed?

Through half-shut eyes, she saw the red-gold glow of Lady Deverell and the gleam of Sir Charles’s teeth, dangerously bared. Points of light from various gems danced across the walls and ceilings behind them. The wallpaper pattern was a repetitive curl of red and gold, a curiously soothing thing to look at. She fixed her attention on it, lulled, comforted. She leant back against the door jamb, feeling her legs twitch a little and then …

A kick on her shin.

‘Keep upright,’ hissed Jenny.

She had been on the point of falling asleep where she stood, like a horse. How did anyone live this life without doing so all the time? And this was only her first day.

Somehow she dragged her body through pudding, but it was still another half-hour before the ladies retired to the drawing room.

She swooped forwards to take the dishes downstairs for the last time. Gathering the last of them up, she made the mistake of looking again at Sir Charles, who was smiling at her as he poured himself a brandy. The smile struck Edie as predatory and she made a hasty escape to the kitchen, feeling like one of the grouse they had spoken of shooting at.

‘Told you,’ said Jenny at the bottom of the staircase. ‘He’s got an eye for you already. Watch yourself, girl.’

‘I don’t want to watch anything,’ said Edie, stacking the dishes up by the sink, thanking her lucky stars that she wouldn’t be washing them. ‘I want to shut my eyes and fall into my bed.’

‘Aren’t you coming for a game of cards in the kitchen?’

‘I simply can’t. I’m half asleep already.’

‘Fair enough. Sweet dreams, then. I hope they won’t be of him. I don’t want to see you go Susie’s way.’

‘I won’t.’

* * *

Edie’s dreams were of nothing, or, if they had substance, it soon melted from her memory. Her first consciousness was of a foreign place, a bed too hard, a pillow too flat, and a peculiar smell of other bodies and their exhalations.

She was the only one abed. The other three girls were dressing already, yawning and tying each other’s apron laces.

The rain still beat dully against the little square-paned window and somebody had thought to light a candle, even though the summer dawn had broken half an hour since.

Edie had never risen this early, save on a handful of special occasions, and she bitterly resented having to leave the warmth of her bed to engage in a day of more hard and mystifying work.

The girls seemed disinclined to talk, going about their morning ablutions in pale-faced trances. The memory of Charles and Lady Deverell at last night’s dinner hit Edie once more – a big, nauseating blow. Why had she been so stupid as to get herself noticed? All she had had to do was serve some soup, for heaven’s sake.

‘How was the bed? Could you sleep in it?’ asked Jenny, coming up behind Edie as she brushed her hair, having waited patiently for the use of the room’s only mirror.

‘Oh, it was a little narrow, but comfortable enough,’ she said vaguely.

‘I was so pleased to have a bed to meself, I never worried about its being narrow,’ confided Jenny. ‘Had to share with two sisters back at home. Have you got brothers or sisters?’

‘None.’

‘You won’t be missing them, then. Is your ma and pa alive?’

‘I live with my father. Lived,’ she corrected.

‘He’ll feel your absence, then. Only child gone away from home.’

She pursed her lips sympathetically. Edie, feeling underhanded and low for garnering the girl’s simple compassion, merely smiled tightly and put the brush down.

‘Could you arrange my hair? I have no skill for it myself.’

‘You’ll have to get it,’ said Jenny with a laugh. ‘Heavens, you need to be able to do these things. You’ll never rise to lady’s maid if you can’t fix hair.’

‘You’re quite right. I wonder, Jenny, would you let me practise on you sometimes?’

‘If you like.’

There was a silence while Jenny’s fingers worked deftly on Edie’s heavy auburn hair.

‘You’ve got such a lovely lot of it,’ she said, fixing the cap on top with a quantity of pins. ‘It’s just like Lady Deverell’s – that glorious colour too. I’ve always longed to be her maid and get my hands on those locks. I can play with yours instead now.’

Edie laughed. ‘I’ve been told I have a look of her sometimes. Do you think so?’

Jenny narrowed her eyes, looking over Edie’s shoulder into the mirror.

‘The hair, yes. The eyes, no. Hers are blue, yours are brown. And your nose is completely different … but I think in the shape of the face … Well, let’s say I wouldn’t get you mixed up from the front, but I might from behind, if your hair was down.’

‘There are many worse people to resemble,’ said Edie.

‘Yes, look at me, I’m told I favour Little Tich.’

Edie burst out laughing. ‘Oh, you don’t!’ she exclaimed. ‘That’s a wicked and cruel thing to say.’

Verity, the senior housemaid of the group, stood in the doorway tutting.

‘Enough of that,’ she said. ‘You’ll be late for breakfast. Jenny, you aren’t her lady’s maid, for heaven’s sake. If she can’t do her own hair, it’s high time she learned.’

Downstairs – such a way downstairs – Edie served herself a ladleful of porridge from the big pan and sat down at the long trestle. She did not want to draw attention to herself, but she had questions on her mind and hoped somebody would be able to answer them.

In the event, Ted did the job for her, without her having to say a word.

‘Morning, Topsy,’ he said, ruffling her hair as he passed. ‘Can’t stay, I’m afraid – got to take His Lordship to London.’

‘He is going away?’

‘Yes, some shindig at the club, birthday do, I think. Nice little jaunt to the Smoke for me. Wish you could come.’

‘Ted,’ reproved Mrs Munn. ‘That will do.’

He saluted her and made a brisk exit, grabbing his peaked cap from the nail by the door as he went.

‘In view of yesterday’s somewhat inauspicious start,’ Mrs Munn continued, addressing herself to Edie, ‘I’m going to have Jenny keep an eye on you again today. If there’s any repetition of the fiasco with the mirror, I’ll have to consider letting you go. Is that clear?’

‘Perfectly, Mrs Munn,’ said Edie, feeling like a recalcitrant schoolgirl. No Latin prose had ever been as challenging as the mysteries of cleaning and serving, though.

* * *

‘Ted likes you,’ said Jenny, kneeling down beside Edie to sweep the first of a great many fireplaces free of ashes.

‘Oh, he’s a ladies’ man, though, isn’t he? I bet he’s like that with all the girls.’

‘Not all of them,’ Jenny insisted. ‘A lot of the girls are after him, though. He does wear that uniform well.’ She let out a tiny sigh.

‘Oh, Jenny, do you …?’ She left the question delicately poised.

‘It’s a silly daydream, that’s all it is. Plain little Jenny Wrens don’t land fellows like that. I’ll live and die in this place, I don’t doubt.’

‘Oh, don’t say that.’ But Edie knew Jenny was right. Men were scarce these days and those who remained were keenly sought after.

‘I suppose Ted fought in the war?’

‘Yes, he was an infantryman. Fought in the trenches, he did. He won’t never talk about it though. Says he’d rather forget all about it.’

‘And what about … the Deverell sons?’ Edie’s heart stepped up its pace at the mere mention of the name. Damn Charles Deverell and his insidious ways. ‘Did they go to the Front?’

‘Yes, both of them. I’ve told you, haven’t I, about poor Sir Thomas and his shrapnel wound. Very unlucky. Mind you, I suppose he’s still alive, at least.’

Edie wanted to ask after Charles, but she did not trust herself to speak his name without putting in some nuance of tone that might give her away. Jenny already suspected her of a pash on him. Was she right? No, she could not be right. The man was a perfect stranger, and not a very nice one at that.

Instead, they chatted about inconsequential things while grates were black-leaded and floors swept.

They were working in the morning room, Edie on her knees, making heavy work of polishing the fender, when their joint rendition of ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ was silenced by the entrance of a family member.

‘No, do continue,’ Charles said, sinking into a chair and unfolding a newspaper. ‘A little music while I read would be rather congenial, as it happens.’

Edie’s fingers clenched around the cloth, her arm too stiff to move for a moment or two. She did not dare move, knowing that every inch of her skin from the tips of her ears downwards was burning bright. She willed Jenny to ignore her.

‘How’s our new girl?’ he asked softly. ‘Getting into the swing of things?’

Edie made no reply, and Charles did not pursue the conversation. For a deeply uncomfortable half-hour there was no sound but the rustling of newspaper and the scrubbing of iron. She was mortifyingly aware of her bottom sticking out in its tight black skirt, swaying from side to side as she worked. She felt sure that Charles Deverell was watching it. Her skin prickled, an itch at the back of her neck. And something else too – a damp heat between her thighs that she wished would go away.

A masculine cough, the click of a lighter, then the smell of cigarette smoke wafting over her. He wanted her to be aware of him. With rising excitement she wondered, what would happen if Jenny was not in the room?

Would he come over to her, crouch down beside her, tell her he knew that she thought of him, put his hand on her spine and rub it up and down, moving ever lower until he reached her bottom …

This was not a profitable line of speculation. She shut it down and forced herself to concentrate on conferring a high shine upon the poker and the shovel instead.

The only person to come and crouch beside her was Jenny.

‘Next room,’ she whispered. ‘Grate’s looking lovely, too, that’s a nice job you’ve done.’

Only because she had displaced all her thoughts about Charles into hard work, Edie realised. The next task might not absorb her so thoroughly.

She picked up her trug and tried to walk primly out of the room without looking at the indolent Lord in his chair of state, but at the last minute she flicked him a sideways glance and saw that he was watching her.

She lifted her chin higher and stared ahead.

‘Dinner at eight again? I’ll look forward to it,’ he drawled as she hurried through the door.

‘What was all that? Why are you flirting with him?’ hissed Jenny, once they had attained the freedom of the corridor.

‘Flirting with him! I’m doing no such thing. I didn’t even look at him, didn’t even answer his question.’

‘To him, that’s flirting. The more you run, the harder he chases. The worst thing you can do is ignore him.’

‘But that makes no sense. Are you saying that I should, should … make sheep’s eyes at him and then he’ll lose interest and pursue some other poor girl? Perhaps I should offer myself to him. Is that what I should do?’

Her agitation seemed to quell Jenny’s suspicions, but she did not sound entirely convinced when she said, ‘I’m sorry. You weren’t flirting, I know that. But I’d make sure I was never alone in a room with him if I was you.’

He ruins girls. He could ruin me.

Chapter Three (#u2f8c18b7-ecc3-5a7e-afc3-0fc6d3c60067)

Carrie, the indisposed housemaid, was better and so Edie was not called upon to serve the family at dinner that night.

Instead she sat in the kitchen with the cook, the scullery maids and various low-level male staff, drifting in and out of their conversation while she stitched at a rent she had made in her sleeve.

‘You’re accident-prone, you, aren’t yer?’ remarked Mrs Fingall, tiring of some talk about how Lady Mary had reacted to a mail delivery that morning.

‘I’m afraid so,’ said Edie. ‘I’m fearfully clumsy. Have been from a child.’

‘Perhaps service ain’t for you,’ suggested the cook. ‘All that precious china up there. Clumsy people ought to keep away from it. Gawd, ain’t you never sewed before? You’re making a hash of that too. Here, let me.’

She sat beside Edie and took over the operation, her sausage fingers surprisingly deft with the needle.

‘Little bird tells me,’ she said in a low voice once the youngsters had started joshing each other about sweethearts, ‘that one or two fellas round here is sweet on you.’

‘Oh, no,’ protested Edie, wanting to get up and run away, but trapped by the thread that Mrs Fingall held taut.

‘I’m sure you’ve been warned about our Sir Charlie,’ she carried on. ‘So I won’t repeat what’s already been said. But Ted’s a lovely lad. A real prize. Do you think you could look kindly on him?’

Put on the spot, Edie could not pluck one single word from the air.

She swallowed and shook her head, then nodded, then shook her head again.

‘Oh, I am not here for … for that kind of thing,’ she whispered.

‘Of course not. And quite right too. Just, you know, if you ever was so inclined … you could do a lot worse.’ She winked.

A bell rang and Edie glanced up at the complicated system of pulleys and levers that hung on the far wall.

‘Sir Thomas for you, Giles,’ Mrs Fingall called out.

The footman leapt up from the table and dashed away.

‘I’d get to my bed if I were you, dear,’ said Mrs Fingall, cutting the thread with her teeth and tying a final knot. ‘They’ll be finished at dinner soon and they won’t need you for anything more.’

‘Yes, I think I will,’ said Edie, eager for some solitude.

Alone in the attic, she looked out of the window and thought about how far she was from home, in more senses than the strictly geographic. She had never realised how easy her life was, nor how free she had been compared to most women. And not just the servants either. Lady Mary was discontented, straining against the yoke of her father’s expectations for her. Most women lived in prison. She had heard it said but had never understood it as fully as she did now.

She sat on the bed, pulled her knees up to her chin and thought of Sir Charles. It was different for him. He could do as he liked and nobody called him to account. It made her angry, made her want to seek him out and slap his face.

But, of course, that was impossible.

What about Lady Deverell? Was she the most imprisoned of all, forced to play a role for the rest of her life, even though she had fled the stage? If only she could ask her. If only things could be simple.

The thunder of feet on the back stairs drove her to undress quickly and slip into bed, where she feigned sleep before she could be questioned on anything further.

‘Sir Charles wants her,’ she heard Jenny say.

‘Do you think she’ll fall for him?’

‘They all do, don’t they?’

A sigh.

‘If only he’d fall back,’ said Verity. ‘But he never does.’

‘Surely Lord Deverell’d kick him out if he got another girl in the family way.’

‘Maybe. Remember how it was when they found out about Susie?’

There was a collective shudder.

‘You could hear the shouting right across the lawns.’

They fell silent then and Edie waited, curled up on her side, until each body creaked into its bed and the candle was snuffed.

As the girls drifted into sleep, Edie thought back to Mrs Fingall’s words at the trestle table. Could she think of looking kindly on Ted?

Ted.

It would not do to be mooning over a chauffeur. He was lovely, of course, but no doubt he was the same with all the girls. He was a natural flirt, that was all.

Besides, there was to be none of this lovey-dovey frippery for Edie Crossland. She had not spent the last seven years wedded to the Women’s Suffrage movement to be swept off her feet by a fellow in a peaked cap who dropped his aitches. It was inconceivable.

No, he was a helpful friend, and that was as much as he could be. Love was the silly trap into which so many good women fell. It was not going to catch her.

And why was sleep staying so stubbornly away tonight? An hour ago, as she toiled up the back staircase, she had been fantasising about her old bed with its pile of pillows and patchwork throw. Every limb ached, her feet were blistered and her eyelids were gritty with the day’s exertion, and yet her mind would not let her be.

It persisted in going back over the emotions of the last forty-eight hours, so that she swirled in a vortex of fear, exhilaration, curiosity, humiliation, attraction.

The narrow bed was less than comfortable, and the air of the high-up room was thick and humid. She needed to clear her head.

Slippers and dressing gown on, she stole out of the stifling dormitory and down the uncarpeted back stairs, as quietly as she could. At first, she had no notion of where she might wander, but it soon occurred to her that she could find Lady Deverell’s room and stand, albeit divided by the door, in the close presence of that fascinating woman.

She had had the opportunity to drink her in at yesterday’s dinner, but today had brought disappointingly few glimpses of the red-haired beauty. She had watched her cross the lawn in her riding habit, head low and stride determined. How much better, though, to perhaps see her, through a keyhole, in repose. The mask she wore every day would be stripped away and she would see the woman behind it, unadorned and unshielded.

Edie slunk on silent feet along the confusing maze of corridors she had negotiated earlier in the day, trying to remember which had led where.

A wrong turn took her to the library, and she was at once thrilled and soothed by its familiar bookish smell, naturally drawn to the shelves where she squinted to make out the gold lettering on the spines. But the night was too cloudy and the light from the arched stained glass windows too dim as a consequence.

There would be no reading in here tonight.

She found at length the right staircase and the corresponding corridor and walked along it swiftly, taking no notice of portraits and busts that might otherwise interest her, until she was in the wing that housed Lady Deverell’s private rooms.

Did she sleep with Lord Deverell? He had a private bedroom and dressing room at the far end of the same corridor. She knew this was a usual arrangement in the grandest of the old family houses, but it struck her as strange. Did they make appointments for love? Or were the separate rooms a mere formality, an age-old habit they did not possess the modernist urge to break?

Here was her door.

And, oh.

What were these noises coming from behind that door? Surely Lord Deverell was in London? He must have returned straight after the gathering, Ted driving him through the night back to his wife’s side. He must be in the grip of passion.

Edie put her hands to her furiously heating cheeks, guilt-ridden at her snooping now. She should not be here. She should go back to bed immediately.

And yet she found she could not come away from the luxurious moans and sighs that poured through the keyhole.

The act of love. That thing she despised and feared, and yet was fascinated by. She had read Freud and found it terrifying, throwing the book aside in repulsion. No man would make her want to do such a thing.

But what was such a thing? She had never seen it, and reading about things was not always the same, loth as she was to admit the treacherous fact.

Lord Deverell, she knew, was a man nearing his sixties, while his new wife was barely forty. Did she desire him, truly? Surely everybody knew it was a transaction – his wealth and status for her fleshly charms and charismatic glamour.

But love?

Perhaps it was. And, if so, what did love look like? She bent to the keyhole, all the while in a kind of horrified trance, her body driving her towards actions of which, in the light of day, she would strongly disapprove.

At first, she saw that the room was in dim light, the gasoliers on the wall turned down low. The huge four-poster bed could be seen only from an angle that hid the heads of the occupants, but she could see the lower portion, and two pairs of feet protruding from the covers. The larger pair lay between the smaller, and the sheets and counterpane rose up from them into an arch – an arch that moved, quite vigorously and in a rhythmic pattern that matched the low grunts emitting from the unseen upper half.

If this was love, it seemed awfully brutal, thought Edie with dismay, and really little more than animalistic. The creak-creak-creak of the bed springs masked some words being spoken, but then a female voice grew louder and higher, and they became distinct.

‘Yes, you awful, awful beast of a man, have your way with me.’

Edie grimaced. It sounded so savage, almost as if she hated her husband. Perhaps she did.

And then tears came to her eyes as she matched the violent, half-delirious voice with the mellifluous tones she had heard on stage, playing Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. This was what she had come to – loveless coupling with an old man who had bought her.

‘Oh, Ruby Red, you’re mine, you are,’ vowed a deeper voice, snarled up in pain by the sound of it.

‘I’ve told you, don’t call me that!’ objected Lady Deverell, and then her words were muffled, as if he had placed a hand across her mouth.

‘I’ll call you what I damn well like, you bitch.’

Edie drew in a great breath, almost nerved to hammer on the door and drag that dreadful man off his poor wife. But then she heard the most unexpected sound, a high-pitched melting into pleasurable surrender, still coming from behind the obstructing door but none the less clear for it; then falling, sobbing, into a deep sigh.

‘That’s it,’ hissed Lord Deverell, almost inaudibly – but by now Edie’s ear was honed and she caught every syllable. ‘You love it, don’t you? You love what I do to you. Oh, God.’

And now it was his turn to tumble into that dangerous uncontrollable place his wife had just visited.

He made the most terrible, frightening sounds, like a man raging into battle, and Edie saw his feet stretch straight out, every muscle tense, then relax.

The feet flexed and moved, all four together, while the coverlet tent collapsed. The voices lowered to murmurings and languid kissing.

Edie, feeling horribly sick, stood straight, wanting very much to run outside and get some air, regardless of the lashing rain, which had begun again.

She heard Lady Deverell from behind the door say, ‘Oh, darling, must you?’ and then – oh, heavens! – the Lord’s reply, very close to the door.

‘I promised Mary. She’ll garrotte me if I disappoint her again.’

Was that Lord Deverell? Suddenly she was not at all sure. But it could not be …

Edie almost fell over her feet in her haste to get away. A very quick examination of the corridor around her yielded no curtained alcoves in which to hide, nor was it possible to get to the staircase in time. The handle was already turning.

Perhaps one of these other rooms would be unoccupied?

But before she could try one, the door was open and in the corridor in front of her, resplendent in paisley silk dressing gown, was …

But she could not let her jaw drop, could not make any kind of exclamation.

Now she had to use all of her own dramatic powers, or everything was lost.

She stiffened and widened her eyes, making them stare out of her face at the man who stood in front of her.

‘Good God,’ he said. ‘What’s this?’

She said nothing, maintaining her tense, glassy-eyed posture as she walked slowly towards him.

A streak of lightning almost made her jump, but she mustn’t. She must appear oblivious to all around her.

He took a step closer, his head on one side. Edie saw a gleam of recognition brighten his grey-blue eye.

‘It’s the new girl, isn’t it? The parlourmaid?’

Edie stood her ground and stared as if looking straight through him.

‘The old sleepwalking gambit, eh?’

He snapped his fingers in her face.

She did not flinch.

‘Looks like stronger measures are called for,’ he said, and he took hold of her arm and brought his face, dark with wicked intent, so close to hers that she could smell Lady Deverell’s perfume on him. He was going to kiss her! No, he could not …

She pretended to come to her senses, letting her limbs loosen and her breath rush from her in great gasps.

‘Oh,’ she exclaimed. ‘Whatever is this? Where have I come to?’

She tried to shake herself free of him but he was not having it, and he marched, dragging her along with him, to the nearest empty room, into which he unceremoniously pushed her.

‘Please,’ she remonstrated. ‘Please let me go back to bed. I didn’t mean to be here, I swear it.’

He took his hand from her and folded his arms, glowering darkly down at her.

‘I don’t know who you are or what you saw,’ he said in a low, menacing tone. ‘But, whatever it was, you’ll do well to forget it. Do you understand me? Not a word to anyone.’

‘I promise, sir, I won’t … I didn’t … anyway. I don’t know what you mean, I’m sure.’

‘Hmm, I’m sure,’ he said, looking at her assessingly, his eyes all over her, making her flush hot and drop her gaze to the ground.

‘I’d better get back,’ she said, half-turning.

He put his fingers under her chin, gently holding her in position, shaking his head and tutting his disagreement with this proposition.

‘You are the new parlourmaid, aren’t you?’

She nodded, constricted somewhat by his unyielding grip on her face.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Edie. Edie Cr–, uh, Prior.’

‘Edie Cruuur-Prior?’ he repeated, tauntingly. ‘Unusual name.’

‘Just the Prior. I changed my name when my mother remarried. I forget, sometimes.’

He regarded her for a silent stretch of time, during which Edie committed his face to memory – its angles and shadows, the prominent nose, the full, sensual lips, the gleaming eyes, the lustrous dark hair, the cruel, handsome whole of it.

He looked utterly heartless to her, and glitteringly magnetic at the same time.

She was more afraid than ever.

‘You know who I am, of course?’

‘You’re Sir Charles, I think, sir.’

‘That’s right. I’m Charles Deverell, Lord Exley, heir to the estate. How’s life in service so far, Edie?’

‘Tiring,’ she said, tripping over the words in her anxiety. ‘I’m tired. I should sleep.’

‘Yes, they treat you like working dogs down there, don’t they? My hounds have a better life. But I’ll give you a little tip, Edie. Be a good girl, and you might find that there are perks to your job.’

His fingers brushed up her cheek, so lightly that the caress in them could almost be attributed to the air.

‘Are you a good girl, Edie?’ he whispered.

Weakness rinsed through her limbs. She had no reply to offer.

‘Tired,’ she whispered, her lips quivering.

He seemed to take a step back, though in reality he did not move. The seductive intensity in his eyes broke and he smiled, half-laughing.

‘Yes, you’re right, it’s late and I don’t have much more in me, much as I’d like to test the proposition.’

‘You and Lady Deverell–’

He held up a finger.

‘I’ve told you. Seal your lips. Well, until I want to unseal them, that is.’

That dazzling grin again, unsettling as a punch to the solar plexus.

‘I suggest,’ he continued, ‘that you take the three wise monkeys as your template while you’re working here.’

See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.

‘I understand, sir.’ She looked towards the door and he relented.

‘Run along then, Edie Cruur-Prior. Perhaps I should speak to Mrs Munn tomorrow about having a lock put on your dormitory door. But only if I can have a key.’

She turned and fled, running through the corridors and up the staircases, losing her way half a dozen times, until the low-ceilinged corridor that housed the staff dormitories appeared at the head of the uncarpeted back stairs.

All three of her roommates were deep in sleep, making the most of time away from dishpans and dustpans. A flash of lightning lit the room and she noticed how red and coarse Peggy, the young scullery maid’s, hands already were, and her only fourteen years old.

Edie inspected her own hands, pale and unblemished. How long would they remain so?

Her stomach was in knots and her head whirling when she lay down and tried to sleep through the thunderous rain. This had been a terrible idea. She had knowledge she did not want now, about Lady Deverell, and she had played directly into the hands of Sir Charles, who might now hound her with seduction attempts.

Which she would, of course, repel.

Of course.