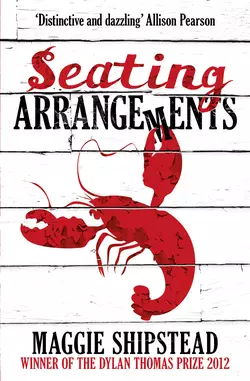

Seating Arrangements

Maggie Shipstead

A New York Times bestseller and winner of the 2012 Dylan Thomas Prize, this ebook special edition contains exclusive bonus content.The Van Meters have gathered at their family retreat on the New England island of Waskeke to celebrate the marriage of daughter Daphne to an impeccably appropriate young man. The weekend is full of lobster and champagne, salt air and practiced bonhomie, but long-buried discontent and simmering lust seep through the cracks in the revelry.Winn Van Meter, father-of-the-bride, has spent his life following the rules of the east coast upper crust, but now, just shy of his sixtieth birthday, he must finally confront his failings, his desires, and his own humanity.This ebook edition contains an extended extract of Maggie Shipstead’s second novel, Astonish Me.

About the Author (#ulink_028bd6fd-22b8-5253-ad9d-498a867c8017)

Maggie Shipstead graduated from Harvard in 2005 and earned an M.F.A at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She was also a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University. Seating Arrangements is her first novel and was awarded the Dylan Thomas Prize in 2012, the largest award in the world for writers under 30. She was also awarded the LA Times Book Award for First Fiction. She lives in California.

About the Book (#ulink_da0afe63-bb3f-5ac7-afed-25db8ad59b1a)

The Van Meters have gathered at their family retreat on the New England island of Waskeke to celebrate the marriage of daughter Daphne to an impeccably appropriate young man. The weekend is full of lobster and champagne, salt air and practiced bonhomie, but long-buried discontent and simmering lust seep through the cracks in the revelry.

Winn Van Meter, father-of-the-bride, has spent his life following the rules of the east coast upper crust, but now, just shy of his sixtieth birthday, he must finally confront his failings, his desires, and his own humanity.

Praise for Seating Arrangements (#ulink_0dd22ba9-472e-54d1-88ea-6a58cb324f2b)

‘Irresistible … her prose is joyously good’

DAILY MAIL

‘A ferociously clever comedy of manners’

GUARDIAN

‘A wise, sophisticated and funny novel about family, fidelity, class and crisis’

MARIE CLAIRE

‘Well-observed, hilarious, yet moving’

WOMAN & HOME

‘Definitely one to watch’

GRAZIA

‘Maggie Shipstead is an outrageously gifted writer’

Richard Russo, author of Empire Falls

‘Startling beauty’

NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

Seating Arrangements

Maggie Shipstead

Copyright (#ulink_a8475aa0-7e6a-5744-9429-f3d4e9ed323a)

The Borough Press

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2012

Copyright © Maggie Shipstead 2012

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013. Designed by Stuart Bache.

Maggie Shipstead asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

‘The Waste Land’ taken from The Waste Land and Other Poems © Estate of T.S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007467730

Ebook Edition © May 2014 ISBN: 9780007425235

Version: 2015-08-03

To my parents, Patrick and Susan,

pillars of everything

The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

And their friends, the loitering heirs of City directors;

Departed, have left no addresses.

T. S. ELIOT, “The Waste Land”

Contents

Cover (#ub5dd7bc4-b224-5fb3-a4b9-d1020b36205e)

About the Author (#u99621ce6-8607-5590-b6c2-f1b70d282a5c)

About the Book (#uda5236de-e6da-5e2a-bfc5-f3302e2a5926)

Praise for Seating Arrangements (#uf1eb5439-2ca2-544e-9b2b-f9f538448378)

Title Page

Copyright (#ulink_c25003c8-00f1-51f3-a560-cb3182159d91)

Dedication

Epigraph

Thursday

One · The Castle of the Maidens

Two · The Water Bearer

Three · Seating Arrangements

Four · Twenty Lobsters

Five · The White Stone House

Six · Your Shadow at Evening

Seven · The Serpent in the Laundry

Eight · A Party Ends

Friday

Nine · Snakes and Ladders

Ten · More than One Fish, More than One Sea

Eleven · Flesh Wounds

Twelve · Fortunate Son

Thirteen · A Centaur

Fourteen · The Sun Goes over the Yardarm

Fifteen · Raise Your Glass

Sixteen · A Weather Vane

Seventeen · The Maimed King

Saturday

Eighteen · The Ouroboros

Acknowledgments

Read on for an exclusive extract from Maggie Shipstead’s new novel (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday (#ulink_2935cfb2-32d6-5ca7-8868-8f432e1e7cba)

One · The Castle of the Maidens (#ulink_d261028b-8065-5720-b7bd-293385b18e35)

By Sunday the wedding would be over, and for that Winn Van Meter was grateful. It was Thursday. He woke early, alone in his Connecticut house, a few late stars still burning above the treetops. His wife and two daughters were already on Waskeke, in the island house, and as he came swimming up out of sleep, he thought of them in their beds there: Biddy keeping to her side, his daughters’ hair fanned over their pillows. But first he thought of a different girl (or barely thought of her—she was a bubble bursting on the surface of a dream) who was also asleep on Waskeke. She would be in one of the brass guest beds up on the third floor, under the eaves; she was one of his daughter’s bridesmaids.

Most mornings, Winn’s entries into the waking world were prompt, his torso canting up from the sheets like the mast of a righted sailboat, but on this day he turned off his alarm clock before it could ring and stretched his limbs out to the bed’s four corners. The room was silent, purple, and dim. By nature, he disapproved of lying around. Lost time could not be regained nor missed mornings stored up for later use. Each day was a platform for accomplishment. Up with the sun, he had told his daughters when they were children, whipping off their covers with a flourish and exposing them lying curled like shrimp on their mattresses. Now Daphne was a bride (a pregnant bride, no point in pretending otherwise) and Livia, her younger sister, the maid of honor. The girls and their mother were spending the whole week on the island with an ever-multiplying bunch of bridesmaids and relatives and future in-laws, but he had decided he could not manage so much time away from work. Which was true enough. A whole week on the matrimonial front lines would be intolerable, and furthermore, he had no wish to confirm that the bank would rumble on without him, his absence scarcely noticed except by the pin-striped young sharks who had begun circling his desk with growing determination.

He switched on the lamp. The windows went black, the room yellow. His jaundiced reflection erased the stars and trees, and he felt a twinge of regret at how lamplight obliterated the predawn world, turning it not into day but night. Still, he prided himself on being a practical person, not a poetic soul vulnerable to starlight and sleep fuzz, and he reached for his glasses and swung his feet to the floor. Before going to bed he had laid out his traveling clothes, and when he emerged from the shower, freshly shaven and smelling of bay rum, he dressed efficiently and trotted downstairs, flipping on more lights as he went. He had packed Biddy’s Grand Cherokee the night before, fitting everything together with geometric precision: all the items forgotten and requested by the women, plus bags and boxes of groceries, clothes for himself, and sundry wedding odds and ends. While the coffee brewed, he went outside with the inventory he was keeping on a yellow legal pad and began his final check. He rifled through a row of grocery bags in the backseat and opened the driver’s door to check for his phone charger, his road atlas—even though he could drive the route with his eyes closed—and a roll of quarters, crossing each off the list in turn. Garment bags and duffels stuffed to fatness made a bulwark in the back, and he had to stand on tiptoe and lean into the narrow pocket of air between them and the roof to confirm the presence in the middle of it all of a glossy white box the size of a child’s coffin that held Daphne’s wedding dress.

“Don’t forget the dress, Daddy,” the answering machine had warned in his daughter’s voice the previous night. “Here, Mom wants to say something.”

“Don’t forget the dress, Winn,” said Biddy.

“I won’t forget the damn dress,” Winn had told the plastic box.

He crossed “Dress” off the list and slammed the back hatch. Birds were calling, and yellow light bled through the morning haze, touching the grassy undulations and low stone wall of his neighbor’s estate. Strolling down the driveway to retrieve his newspaper from a puddle, he noticed a few stones that had fallen from the wall onto the shoulder of the road, and he crossed over to restore them, shaking droplets from the Journal’s plastic sack as he went. The hollow sound of stone on stone was pleasant, and when the repair was done, he stood for a minute stretching his back and admiring the neat Yankee face of his house. Nothing flashy and new would ever tempt him away from this quiet neighborhood inhabited by quality people; the houses might be large, but they were tastefully shrouded by trees, and many, like his, were full of thin carpets and creaking, aristocratic floors.

His Connecticut house was home, and his house on Waskeke was also home but a home that was familiar without losing its novelty, the way he imagined he might feel about a long-term mistress. Waskeke was the great refuge of his life, where his family was most sturdy and harmonious. To have all these people, these wedding guests, invading his private domain rankled him, though he could scarcely have forbidden Daphne from marrying on the island. She would have argued that the island was her island, too, and she would have said Waskeke’s pleasures should be shared. He wished that the ferry could take him back into a world where the girls were still children and just the four of them would be on Waskeke. The problem was not that he wasn’t pleased for Daphne (he was) or that he did not appreciate the ceremonial importance of handing her into another man’s keeping (he did). He would carry out his role gladly, but the weekend, now surveyed from its near edge, felt daunting, not a straightforward exercise in familial peacekeeping and obligatory cheer but a treacherous puzzle, full of opportunities for the wrong thing to be said or done.

HE DROVE NORTH along leafy roads, past brick and clapboard towns stacked on hillsides above crowded harbors. The morning was bright and yellow, the car scented with coffee and a trace of Biddy’s perfume. Freight trains slid across trestle bridges; distant jetties reached like arms into the sea. Pale rainbows of sunlight turned circles across the windshield. For Winn, the difficulty of reaching Waskeke was part of its appeal. Unless forced by pressures of time or family, he never flew. The slowness of the drive and ferry crossing made the journey more meaningful, the island more remote. Back when the girls were young and querulous and prone to carsickness, the drive was an annual catastrophe, beset by traffic jams, mix-ups about ferry reservations, malevolent highway patrolmen, and Biddy’s inevitable realization after hours on the road that she had forgotten the keys to the house or medication for one of the girls or Winn’s tennis racquet. Winn had glowered and barked and driven with the grim urgency of a mad coachman galloping them all to hell, all the while knowing that the misery of the trip would sweeten the moment of arrival, that when he crossed the threshold of his house, he would be as grateful as a pilgrim passing through the gates of the Celestial City.

Arriving at the ferry dock an hour early, exactly as planned, he waited in a line of cars at a gangway that led to nothing: open water and Waskeke somewhere over the horizon. Idly, he rolled down the window and watched gulls promenade on the wharves. The harbor had a carnival smell of popcorn and fried clams. When he was a child, for a week in the summer his father would leave the chauffeur at home in Boston and drive Winn down to the Cape himself (such a novelty to see his father behind the wheel of a car). The ferry back then was the old-fashioned, open-decked kind that you had to drive onto backward, and Winn had thrilled at the precarious process even though his father, who might have played up the drama, reversed the car up the narrow ramp with indifferent expertise. They had owned a small place on Waskeke, nothing grand like the Boston house, just a cottage on the edge of a marsh where the fishing was good. But the cottage had been sold when Winn was at Harvard and torn down sometime later to make room for a big new house that belonged to someone else.

The ferry docked with loud clanging and winching and off-loaded a flood of people and vehicles. Some were islanders on mainland shopping expeditions, but most were tourists headed home. Winn was pleased to see them go even if more were always arriving. A worker in navy blue coveralls waved him up the gangway into the briny, iron-smelling hold, and another pointed him into a narrow alley between two lumber trucks. He checked twice to be sure the Cherokee was locked and then climbed to the top deck to observe the leaving, which was as it always was—first the ship’s whistle and then the slow recession of the harbor’s jumbled, shingled buildings and the boat basin’s forest of naked masts. Birds and their shadows skimmed the whitecaps. Though he never wished to indulge in nostalgia, Winn would not have been surprised to see shades of himself stretching down the railing: the boy beside his father, the collegian nipping from a flask passed among his friends, the bachelor with a series of dimly recalled women, the honeymooner, the young father holding one small girl and then two. He had been eight when his father first brought him across, and now he was fifty-nine. A phantom armada of memory ships chugged around him, crewed by his outgrown selves. But the water, as he stared down over the rail, looked like all other water; he might have been anywhere, on the Bering Strait or the river Styx. Without fail, every time he was out on the ocean, the same vision came to him: of himself lost overboard, floundering at the top of that unholy depth.

As the crossing always had the same beginning, so, after two hours, it always had the same end—a gray strip of land separating the blue from the blue, then lighthouses, steeples, docks, jetties reaching for their mainland twins. There was a little lighthouse at the mouth of the harbor where by tradition passengers on outbound ferries tossed pennies off the side. Livia had said as a child that the sea floor there must look like the scales of a fish, and, ever since, the same thought had come to Winn as he passed the lighthouse: a huge copper fish slumbering below, one bulbous eye opening to follow the ferry’s turning propellers. They docked, and as he drove down the ramp into the bustling maze of narrow streets that led out of Waskeke Town, he hummed to himself, relishing solid land.

A BATTERED MAILBOX labeled “VAN METER” with adhesive letters stood at the entrance to his driveway. The narrow dirt track was edged by tall evergreen trees, and he drove up it with mounting excitement, the trees waving him on until he emerged into sunlight. Atop a grassy lump, not quite a hill, that rose like a monk’s tonsure from an encirclement of trees, the house stood tall and narrow, its gray shingles and simple facade speaking of modesty, comfort, and Waskeke’s Quaker past. Above the red front door a carved quarterboard read “PROPER DEWS,” the name he had given the house upon its purchase. The pun was labored, he knew, but it had been the best he could come up with, and he had needed to replace the board left by the previous owner—“SANDS OF THYME”—a name Winn disdained as nonsensical, given that no herb garden had existed on the property before he planted one. The house had been his for twenty years, since Livia was a baby, and over those twenty summers, time and repetition had elevated it from a simple dwelling to something more, a sacred monolith over which his summer sky somersaulted again and again. He parked the car near the back door and gazed up at the neat procession of windows, their panes black with reflected trees.

Something about the place seemed different. He could not have said what. The gutters, shutters, and gables were all intact, all trimmed with fresh white paint. The hydrangeas were not yet flowering but the peonies were, fat blooms of pink and white. He suspected he was projecting some strange aura onto the house because he knew Biddy, Daphne, and Livia were inside with all the bridesmaids and God only knew what other vestal keepers of the wedding flame. As he sat there, listening to the engine tick its way to quiet, a shard of his nearly forgotten dream punctured the pleasure of his arrival. He might have been in the car, or he might have been back in his bed, or he might have been running one finger down a woman’s spine. He tried to push the dream away, but it would not go. He wiped his glasses with his shirt and flipped down the rearview mirror to look at himself. The sight of his face was a comfort, even the chin someone had once called weak. He arranged his features into an expression of patriarchal calm and tried to memorize how it felt—this was how he wanted to look for the next three days. Extracting the dress box and leaving the rest, Winn went around to the side door and let himself in, almost tripping over an explosion of tropical flowers that erupted from a crystal vase on the floor just across the threshold.

“Biddy,” he called into the quiet, “can we find a better place for these flowers?”

“Oh,” came his wife’s voice from somewhere above. “Hi. No, leave them there.”

He let the screen door slam behind him—even though, years before, he had affixed a now-yellowed card to the door that said “do NOT slam”—and stepped around the flowers. He set the dress box down on the floor and grimaced at a pile of sandy and unfamiliar shoes. He matched them in pairs and lined them up along the baseboard. Down the hallway of white wainscoting was a bright rectangle of kitchen light. To his right, the back stairs bent tightly upward, and to his left was a coat closet. Inside he found the usual reassuring line of raincoats and jumble of tennis racquets and beach sandals, but on the top shelf, shoved in with a faded collection of baseball caps and canvas fishing hats, a cluster of gift bags overflowed with tissue paper and ribbon.

“Biddy! What are all these bags in the closet here?”

Again Biddy’s voice floated down from on high. “Bridesmaids’ gifts. Leave them alone, Winn.”

“But let me look first,” said someone close behind and just above him. “Daphne said they’re good.”

Winn turned around, unprepared to see her so soon. “Hello, Agatha!” he said, sounding too jovial.

Agatha came down a few steps and leaned to kiss his proffered cheek. Her collarbones and dark nook of cleavage dipped down and floated back up again. He caught a musky scent, heavy like a man’s cologne, and underneath it the smell of cigarette smoke. She always smelled like smoke even though he had never seen her in the act. She must still sneak around like a teenager, sitting on windowsills, dangling her cigarettes out pushed-back screens. Winn had known few women he would describe as bombshells, but from the undulant contours of her body to her air of careless, practiced dishevelment, Agatha was an authentic specimen. She wore assemblages of thin garments that might have been nightclothes—lace-edged dresses with torn hems, drawstring pants that sat below her hipbones, flimsy cotton shorts—clothing that answered the requirements of decency while still conveying an impression of nakedness. She piled up her hair with bobby pins and odd pieces of ribbon or elastic, and she was always rooting through her purse for something or other and tossing out an alluring potpourri of lipsticks, lighters, crumpled receipts, and bits of broken jewelry.

“How are you?” she asked in her slow way, sounding like she had just woken up. She was wearing a short dress of gauzy white layers that he found oddly bridal. “Welcome to the madhouse.”

“I’m very well.” Winn took a step backward, and something poked his thigh. A bird of paradise from the flower arrangement. “Is it a madhouse?”

“It’s fun—if you like girls. You’re outnumbered.” She counted on her fingers. “Three bridesmaids including me. Plus Daphne and Livia. Your wife and her sister. Am I missing anyone? No. That makes it seven to one.”

“Celeste is staying here?”

“Biddy didn’t tell you?”

“Maybe she did and I forgot.”

“Sorry, Charlie. Plus the coordinator is in and out all the time. We did a dry run with the hairstylist this morning. Daphne wants everything kept simple, thank God. One time I was in a wedding where they did our hair with tendrils dangling down everywhere like dead vines. Makeup practice is tomorrow, and what else? Manicures? There’s something with the dress, too, making room for baby probably. I’m sure I’m forgetting something. Anyway, lucky you.”

“Lucky me,” Winn said. He rubbed his chin and wondered how much all that was costing him. He wondered, too, how she could be so calm while he felt jumpy as a marionette. She, after all, had been the one to take his hand at Daphne’s engagement party, and he had been struggling to keep her from his thoughts ever since. Truthfully, he had been struggling to keep her from his thoughts for years, but the party was the first time she had shown any interest. He didn’t flatter himself—he had seen her around enough men to know flirtation was, for her, an impersonal reflex, and sex appeal was something she rained down on the world indiscriminately, like a leaflet campaign. And nothing had happened. Not really. Only an interlocking of fingers under the privacy of the tablecloth, but still the touch had shocked him. And she had been the one to take the seat next to him, to find his hand where it was resting on his knee and pull it toward her.

Agatha gazed down at him, her head tilted to one side, almost to her shoulder. “Anyway, I’ve been sent to get the dress.”

“Right!” He pivoted to pick up the white box and held it out. “All yours.”

She hefted it. “It’s heavier than I expected.”

“I’m told a pregnant bride requires scaffolding.”

She laughed, a single syllable that stuck in her throat, less an expression of mirth than a bit of punctuation, a flattering sort of ellipsis. She hitched her chin and rolled her eyes up toward the second floor. “I should take this to Daphne.”

He said Okay! and Bye! as though ending a telephone call and watched her disappear around the bend of the stairs. He’d known Agatha since she was fourteen and Daphne’s first roommate at Deerfield, and though she must be twenty-seven now, he couldn’t shake his idea of her as a Lolita. His attraction still embarrassed him as much as when it had revolved around her field hockey skirt. She had been a lackluster athlete; probably she had played only because she knew she looked spectacular in skirt and kneesocks, loping down the field with her hair in two messy braids. Did she even remember taking his hand? She had been tipsy at the party, everyone had been, and at the time he had panicked because, after all these years, she knew, perhaps had always known. But, that night, lying awake and thinking of her bare knee under the back of his hand, her palm against his, he found he was relieved; now the chips would fall where they may.

Stepping around the flowers, he shut the coat closet and walked down the hall to the kitchen. As children, Winn’s daughters had run through the house upon first arrival each summer to remind themselves of all its singularities and unearth relics of their own brief pasts. They made joyful reunions with the canvas sofas, the insides of closets, the views from all the windows, the books on fish and plants and birds, the bowls of sea glass, the wooden whale sending up its flat, wooden spout on the wall above Winn and Biddy’s bed, the flower patch where the sundial lay half concealed beneath black-eyed Susans, the splintery planks of the outdoor shower. The kitchen cupboards were thrown open so the cutting boards and bottles of olive oil might be greeted and the enormous black lobster pot marveled over. The hammock was swung in and the garage door heaved up to reveal, through cirrus whirls of dust, an upside-down canoe on sawhorses and the ancient Land Rover they kept on the island. The girls would converge on Winn and clamor at him until he unbolted and pulled open the hatch to the widow’s walk so they could stand on top of the house and look out over the island.

But sometime during their teens, they had stopped caring whether everything was as they remembered and moved swiftly and directly to their rooms to arrange their clothes and toiletries. Little blasts of squabbling percussed the walls as they vied for territory in their shared bathroom. Winn had taken up the job of walking around the house to inspect all the nooks and crannies. He breathed lungfuls of salt and mildew and tipped frames back to center with one finger. He opened all the closets. He tested the hammock. He walked blindly through the spiderwebs in the dark garage.

This time on his rounds downstairs he found that everywhere he looked there were more things than there should have been, more stuff, and yet for all the women in the house and all their feminine appurtenances, no one came down to greet him. He went out to the car and brought in the luggage and groceries. Leaving the duffels at the foot of the back stairs, he carried the groceries into the kitchen and pushed aside a layer of magazines to make room on the counter. Makeup pencils and brushes were everywhere, abandoned helter-skelter as though by the fleeing beauticians of Pompeii. He walked around collecting them and then set them upright in an empty coffee mug. He straightened the magazines into piles. From the sink he extracted an object his daughters had taught him was an eyelash curler. A round brass ship’s clock ticked at the top of a bookshelf, its arrow-tipped hands and Roman numerals insisting it was four thirty. He looked at his watch. Not yet one. He pressed his fingers into a puddle of face powder spilled on the dining table and walked them across the varnished top, leaving a trail of flesh-colored prints that he immediately wiped up with a sponge. Even in his study, his cloister of masculine peace and quiet, he found a nail file and the top half of a bikini on his desk.

He was holding the bikini top by its strings and examining it (it was white with red polka dots, the fabric worn thin, the straps looped in a messy knot instead of a bow; he wondered if Agatha’s were the breasts that had last filled its cups and if she could have left it on purpose) when a movement out the window caught his eye. From the side of the house a slope of grass rambled down to the trees, interrupted here by a pair of stray pines with a hammock strung between them and there by a badminton net and there by his vegetable garden, wrapped in flimsy green fencing to deter the deer. After years of taking a bearable tribute from around the edges, the deer seemed to have grown in numbers or appetite, and the previous summer, the family had arrived to find all Winn’s herbs and vegetables eaten down to nubs. He had gone out at once and bought a roll of green plastic mesh and strung it savagely around his plants. The fence was unsightly—Livia said the garden looked like a duck blind—and still the yield was a disappointment. Some condition of soil or climate had stunted the plants into spindly bearers of flaccid leaves and runty fruit. Biddy had broken the news to him over the phone, bridesmaids squealing in the background. “I’m afraid you don’t have much of a harvest,” she said.

“Is it the deer?” he had asked.

“No, everything’s just a little on the sickly side.”

“Why?”

“Oh, Winn, I’m not a botanist,” she had said, sighing.

Livia was lying in the hammock. Blue shade fell over her bare legs and arms, and she had twisted her hair into a dark rope and pulled it around her head and across her neck. A book lay open on her stomach, the breeze ruffling the pages. Her hands were pressed flat against her face. That was the motion that had attracted his attention: the lifting of her hands from the book. She was very still; he did not think she was crying. After a long time she dropped her hands to her clavicle and stared up into the branches. Winn’s softer emotions came upon him rarely, as unexpected visitations from a place he could not guess at. He reached out and touched the window. Flat on her back in the cool shadows, Livia looked like a funeral statue. He knuckled three quick beats on the window and then again, harder, but she didn’t turn her head. His powdery fingerprints ghosted the glass. He wiped them away. He thought he would go out and see her, but a stampeding sound came from above, and when he emerged, it was to a kitchen full of women.

“Hello, dear,” he said, pecking Biddy on the cheek.

“I want to leave those flowers there so I don’t forget to take them to the Duffs’ hotel later,” she said.

“I don’t know how you’d forget them. I thought I was in the Amazon.”

“After the wedding I’ll remember things again. Until then you’ll have to step around the flowers.”

He went around stamping cheeks with his businesslike kisses: first Daphne and then Biddy’s sister Celeste where she stood beside the refrigerator fishing an olive out of a jar with her index finger. Agatha and the other bridesmaids were lolling against the counter, and he kissed each of them, saying, “Agatha, hello again, Piper, Dominique.”

“How was the trip?” asked Biddy.

“Easy. I got an early start. The crossing was smooth.”

Celeste thrust a half-filled tumbler into his hand and clinked it with her own. Three olives drifted around the bottom. “You don’t have any martini glasses,” she said. “Other than that, everything has been fabulous.”

Setting the glass on a stack of magazines, he said, “Is the sun over the yardarm already?” He seldom drank hard liquor anymore, especially not in the middle of the day, but if he reminded Celeste of this, she would want to know for the umpteenth time why not, and he was in no mood to explain that it had to do with his headaches and not at all with any judgment of those who daily embalmed their innards from the moment the sun inched past its apex to the hour when their feet tipped them onto whatever couch or bed was handiest.

“Depends on where you keep your yardarm,” she said. Her smile was localized to her lips and their immediate region. Biddy had explained that Celeste had gotten carried away with wrinkle injections, but the effect was still eerie.

Winn frowned and turned to the bridesmaids. “Having a good time, girls?”

“Yes,” came the chorus from the bridesmaids, who had settled with Daphne in a languid clump against the sink. Like Daphne, Agatha and Piper were blond and short. Dominique was tall and dark, a menhir looming over them. She was the child of two Coptic doctors from Cairo and had spent most of her breaks from Deerfield with the Van Meters. Her face was symmetrical but severe, a smooth half dome of forehead descending to steeply arched eyebrows, a nose with a bump in its middle, and a wide mouth that drooped slightly at the corners in an expression of not unattractive mournfulness. Muscle left over from her days as a swimmer armored her shoulders and back. Her hair, which was not quite crimped and African but also not smooth in the way of some Arabs’, was cut very short. He hadn’t seen her for a few years. After college in Michigan she had flown off to Europe (France? Belgium?) to become a chef. He liked Dominique; he respected her physical strength and her skill with food, but he had never understood her friendship with Daphne, who took no interest in sports or cooking and who seemed diaphanous and flighty beside her.

Dominique pointed one long finger out the window. “Your garden is looking a little peaky,” she said.

“So Biddy told me. I haven’t gone out to take a look at it yet.”

“Were you having problems with the deer?”

“Terrible. They’re glorified goats, those things. But Biddy doesn’t think they’re the culprit this time.”

“Yeah, I didn’t see much nibbling, except around the edges. And I looked for aphid holes and that sort of thing but didn’t see enough to explain why it all looks so sad. Maybe the soil is too acidic.”

“Could be.”

“Did you do the planting?”

“The first time, eight or nine years ago, but a local couple does the basic caretaking when we’re not here. Maybe they tried something different. I hope if they wanted to experiment they wouldn’t do it in my garden.”

Dominique nodded and looked away as though concealing disdain for people who did not tend their own vegetable gardens.

“I’m so psyched for the wedding,” Piper announced out of the blue and in a high chirp, which was her way. She and Daphne had met at Princeton, and Winn knew her less well than the others. Always in motion, propelled along by a brittle, birdlike pep, she seemed a tireless font of chipper enthusiasm. She was pale as bone and dwelt beneath a voluminous haystack of white blond hair, her glacial eyes and red-lipsticked lips adrift in all the whiteness like a face drawn by a child. Her eyebrows were barely discernible, her nose small and sharp. Some men found her powerfully attractive, Winn knew, but she left him cold. Her looks were ethereal and a little strange, but Agatha’s were concrete, radiant, tactile; her limbs could almost be felt just by looking at them. Daphne fell somewhere in the middle. They were three shades of woman arrayed side by side like the bewildering, smiling boxes of hair dye in the supermarket.

“It’s beautiful here,” Agatha said, letting her head fall onto Piper’s shoulder. A male friend of Daphne’s had, years ago, in a moment of drunken gossip, implied that Agatha was a closeted prude—There’s no engine, he’d said. You hit the gas and nothing happens—but Winn had trouble believing something so disappointing could be true.

“Thanks for bringing my dress, Daddy,” Daphne said.

“Yes,” he said to Agatha. “Waskeke is the way the world should be.” He was staring at her too intently and looked away, at Biddy, who was rummaging through the grocery bags. With a grunt, Daphne pushed off from the sink, waddled across the kitchen, and plopped into a Windsor chair behind Winn. “Daphne,” he said, turning, “are you feeling all right?”

“I feel fine,” she said.

“Why did you make that noise?”

“Because I’m seven months pregnant, Daddy.”

He asked for and received a full briefing on the status of the weekend. Where was Greyson? At the hotel with his groomsmen, Daphne said. His parents? They would be arriving around five. The head count for that night’s party, a dinner Winn would be preparing, was seventeen. The get-together would be a casual thing, with lobsters, a chance for everyone to enjoy the island before they had to get serious about matrimony, a sort of pre-rehearsal-dinner dinner. Had Biddy confirmed the lobsters? She had.

Winn nodded. “All right,” he said. “Well, then good.”

“By the way,” Daphne said, “Mr. Duff is allergic to shellfish.”

Winn fixed her with a look. “Why didn’t you tell me sooner?”

“It’s no big deal. Just buy a tuna steak, too.”

“Are you going to call him Mr. Duff after you’re married?” asked Celeste.

“I have a hard time addressing him as Dicky,” said Daphne gravely. “He says to call him Dad, but most of the time I don’t call him anything.”

Biddy said, “Everyone calls him Dicky. It’s his name. He won’t think it’s odd for you to call him by his name. You’re being ridiculous.”

“Re-dicky-ulous,” said Dominique, and the women laughed.

“Where’s Livia?” Winn asked, even though he knew.

“Around here somewhere,” said Daphne. “Hating me. You know, I really think her dress is pretty. I really do. I wanted to set her off from the other bridesmaids, which is a nice thing, isn’t it? She’s just being contrary. It’s a green dress. That’s all. She says it’s the exact shade of envy and everyone already thinks she’s jealous even though she’s not, but it’s not the color of envy. It’s more of a viridian.”

“Too late to change it,” said Biddy.

The moment of welcome faded into a lull. The staring half circle of female faces made Winn uneasy. With a loud, contented sigh, he turned to look out the window. Daphne held her hands out to Dominique and was heaved to her feet. “Ladies,” she said, beckoning to her bridesmaids. They wandered off, their voices drifting through the house like the calls of distant birds.

“Nice trip?” Celeste asked, having lost track of the earlier part of the conversation.

“Couldn’t have been smoother,” he said.

“You must have gotten up at the crack of dawn.”

“Just before.”

“Drink up there, Winnifred.” She picked up his glass and handed it to him again with a wink. “You deserve it.”

“If you insist.” He touched his lips to the liquid. Gin.

The house was L shaped, with a planked deck filling the crook and extending out over the grass. Through the kitchen’s French doors, Winn saw Livia walk up the lawn and onto the deck. She wore an old pair of gray shorts, and her legs were thinner than he had ever seen them. When she came through the doors and into the kitchen, a push of salt air came with her.

“Oh, Dad,” she said. “Hi.”

She made no move to embrace or kiss him. In the hammock, she had appeared sepulchral and blue, but that must have been a trick of the shade because she looked fine now, a bit pale but fine. She turned away, chewing the side of her thumbnail.

“Hi, roomie,” Celeste said.

“You two are bunking together?” Winn said. Biddy must have sprung the arrangement on Livia, otherwise he would have already gotten an earful.

“Yes,” said Livia in a neutral voice, inspecting her hand. The nails were bitten to nothing, and the flesh around them was torn and raw.

Celeste jiggled her glass enticingly. “Can I get you a drink?”

“No, thanks.”

“Moral support for Daphne?” Celeste asked. “Poor thing not having a drink at her own wedding. I don’t know what I would have done without a drink or two during my weddings.”

“Let alone your marriages,” Biddy said.

“Only you,” Celeste said, swatting Biddy’s flat backside, “could say to that to me.”

“Daphne can have a glass of champagne,” Livia said. “She’s seven months. It’s fine.”

Celeste sipped. “Is it? Shows what I know.”

“Maybe I will have a drink,” Livia said. “I’ll get it myself.”

“How is Cooper?” Winn asked Celeste. “Still in the picture?” He reached out to touch Livia’s hair as she moved away.

“He’s fine. He’s sailing in the Seychelles. He wanted to come but he couldn’t.”

Livia took a bottle of wine from the refrigerator and picked at the foil. “Do you think he’ll be number five?”

“I’m getting out of the marriage business.” Celeste raised her glass as though someone had made a toast. “Though I’ll admit all this is making me sentimental. Nothing beats being a bride. Oh well. Days gone by. I’ll have to live vicariously through my nieces.”

Livia threw the foil into the garbage. “Don’t look at me.”

“Oh, sweetheart, it was his loss. There are so many fish in the sea. You’re only nineteen.”

“I’m twenty-one.”

“You are? Well, then, you’re an old maid.”

Livia put a corkscrew to the bottle and twisted it. Winn watched the curl of silver disappear. Her fingers wrapped so tightly around the bottle that her bones stood out under her skin. Winn wanted to tell her she didn’t need to squeeze so hard, wringing the bottle’s neck like she was. He remembered once watching her shatter an ice cream cone in her hand, crying out in surprise at the cold shards of waffle. “I forgot I was holding it,” she had said. “I was thinking of something else.” Why Livia always had to be so forceful, straining when she didn’t need to, was beyond him, but he held his tongue. She clamped the bottle between her knees and pulled until it exclaimed over the loss of its cork.

Two · The Water Bearer (#ulink_1fe5538c-9aa9-552f-bb1d-7765bef20ea6)

Before he became a father, Winn had assumed he would have sons. He had expected Daphne to be a boy, had lain with his ear against Biddy’s pregnant belly and heard male voices echoing down from future lacrosse games and ski trips. He saw a small blue blazer with brass buttons, short hair combed away from a straight part, himself teaching a boy to tie a necktie. He would drive his son to Harvard when the time came and help him carry his bags through the Yard, would greet his son’s roommates and their fathers with hearty handshakes. His son would join the Ophidian Club, and Winn would attend the initiation dinner and drink with the boy who would live his life over again, affirming its correctness at every juncture.

When the screaming ham hock the doctor pulled from between Biddy’s legs turned out to be unmistakably female, all crevices and puffiness, he felt a deep and essential surprise, not only that the child brewing in his wife those nine months was a girl but that he, Winn, possessed the seeds of a feminine anything. Inside the tangled pipes of his testicular factory there existed, beyond all reason, women. Watching Biddy and Daphne nestle together in the hospital bed, he realized he had been mistaken to think that pregnancy and birth had something to do with him. He had imagined that by impregnating this woman he had ensured she would deliver a son who would go forth and someday impregnate another woman who would, in turn, have a son, and so on and so forth down the Van Meter line into the misty future. But now, instead, there was this girl-child who would grow breasts and take another man’s name and sprout new branches on an unknown family tree and do all sorts of traitorous things a son would not do. The shifting and swelling of Biddy’s boyish body into a collection of spheroids, the quiet communion she lavished on her belly, her new status with her sisters and her covey of friends—all this should have told him he was standing at the threshold of a club that would not have him. Even though women held out their arms and exclaimed, “You’re going to be a faaa-ther!” he suspected they had seen him all along for what he was: the adjunct, the contributor of additional reporting, the lame duck about to be displaced from the center of his wife’s affections. The surprise should not have been that he had a daughter but that any boys were ever born at all.

When, five years later, Biddy announced she was pregnant for the second time, Winn assumed from the first that the baby would be a girl. The deck was stacked; the game was rigged. Daphne was so staunchly female that the possibility of his and Biddy’s genes being put back in the tumbler and coming out a boy seemed too small to bother with. Biddy gave him the news in bed in the morning, and he kissed her once, hard, and said, “Well!” before going downstairs to sit behind the Journal and think about a vasectomy. He was at the kitchen table, staring sightlessly at the pages when he heard the rustling, tinkling sound that announced Daphne. She slid into a chair and sat eating red grapes out of a plastic bag. She wore a piece of crenellated, bejeweled plastic in her hair, and a cloud of pink gauze stood up where her skirt bent against the back of the chair.

“Good morning, Daphne. Going to dance class today?”

“No. That’s on Wednesday.”

“Isn’t that a dance skirt you’re wearing?”

“My tutu? I just threw this on.”

Winn stared at her. She looked back at him and fingered one of the strands of plastic beads that garlanded her neck. Somehow in her infancy she had absorbed a set of phrases and mannerisms that Biddy called breezy and Winn called absurd but that, in any event, had her swanning through preschool like an aging socialite. They left her once with Biddy’s eldest sister, Tabitha, and went to Turks and Caicos for a week, hoping Tabitha’s son Dryden would get her to dirty her knees a little. Instead, they returned to find Dryden draped in baubles and Daphne arranging clips in his hair.

“Dryden,” Biddy said, “you look awfully dressed up for this time of day.”

The boy released a sigh of weary sophistication. He fluttered his blue-dusted eyelids and spread his fingers against his chest. “Oh, this? This is nothing. The good stuff’s in the safe.”

To Winn, Daphne was a foreign being, a sort of mystic, a snake charmer or a charismatic preacher, an ambassador from a distant frontier of experience. The academic knowledge that she was the product of his body was not enough to forge a true belief; he felt no instantaneous, involuntary recognition of her as flesh and blood. Not for lack of trying, either. He had changed her diapers and held her while she cried in the night and spooned gloopy food into her mouth, and certainly he loved her, but she only became more and more strange to him as she got older, and his love for her gave him no comfort but instead made him alarmingly porous, full of hidden passageways that let in feelings of yearning and exclusion. Sitting behind the paper, he imagined with trepidation a house populated by two Daphnes, a Biddy, and only one Winn.

“Daddy,” came the piping voice from across the table, “am I a princess?”

“No,” Winn said. “You’re a very nice little girl.”

“Will I be a princess someday?”

Winn bent the top of the newspaper down and looked over it. “It depends on whom you marry.”

“What does that mean?”

“Well, there are two ways for a woman to become a princess. Either she’s born one, or she marries a prince or, I think, a grand duke—although I’m not sure those exist anymore. You see, Daphne, many countries that used to have princesses don’t anymore because they’ve abolished their monarchies, and an aristocracy doesn’t make sense without a monarchy. Austria, for example, got rid of all that business after the First World War. Hereditary systems like that aren’t fair, you see, and they breed resentment among the lower classes. Anyway, the long and short of it is, since you weren’t born a princess, you would need to marry a prince, and there aren’t very many of those around.”

Reproachfully, she ate a grape and then wiped her fingers one at a time on a napkin. He returned to reading.

“Daddy.”

“What?”

“Am I your princess?”

“Christ, Daphne.”

“What?”

“You sound like a kid on TV.”

“Why?”

“Because you’re full of treacle.”

“What’s treacle?”

“Something that’s too sweet. It gives you a stomachache.”

She nodded, accepting this. “But,” she pressed on, “am I your princess?”

“To the best of my knowledge, I don’t have any princesses. What I do have is a little girl without any dignity.”

“What’s dignity?”

“Dignity is behaving the way you’re supposed to so people respect you.”

“Do princesses have dignity?”

“Some do.”

“Which ones?”

“I don’t know. Maybe Grace Kelly.”

“Who is she?”

“She was a princess. First she was an actress. Then she married a prince and became a princess. In Monaco. She was killed in a car accident.”

“What’s Monaco?”

“A place in Europe.”

Daphne took a moment to absorb and then asked, “Am I your princess?”

“We’ve just been through this,” Winn said, exasperated.

She looked like she was trying to decide whether her interests would be better served by smiling or crying. “I want to be your princess,” she said, teetering toward tears. Daphne was an accomplished crier, plaintive and capable of great stamina. For a girl so physically delicate and soft in voice, she was unexpectedly stalwart in her emotions. Her tears were purposeful, as were her smiles and pouts. Biddy called her Lady Macbeth.

Ducking back behind his paper, Winn did what was necessary. “All right,” he said. “Daphne, you are my princess.”

“Really?”

“Absolutely.”

Daphne nodded and ate a grape. Then she cocked her head to one side. “Am I your fairy princess?”

Biddy, when Winn went looking for her, was getting out of the shower. Through the closed door he heard the water shut off and the rattle of the shower curtain. She was humming something to herself. He thought it might be “Amazing Grace.” Knocking once, he pushed open the door, releasing a cloud of steam. Her bare body, flushed from the shower, was so close he could feel the heat coming off her back and small, neat buttocks. A foggy oval wiped on the mirror framed her breasts and belly button, the dark badge of hair below, his tight face hovering over her shoulder. After fall stripped away her summer tan, her skin tended toward a certain sallowness, but the hot water had turned her chest and legs a rosy pink. Already, her breasts looked swollen. A white towel was wrapped around her head. Her reflection smiled at him. Biddy, he had planned to say, maybe one is enough. He would suggest they sit down and make a pros and cons list. He was holding a yellow legal pad and a blue pen and had already thought of cons to counter all possible pros.

“What is it?” she asked, her smile draining away. He wondered if she had already guessed that he had trailed her to this warm, foggy room to argue her baby away from her. She had some lotion in her hand, and he watched her rub it on her sides and stomach, across stretch marks from Daphne that were only visible in the pale months. “Winn?” she asked. “What?”

“What was that you were just humming?” he asked.

“‘Unchained Melody,’” she said.

“Oh.”

“And?”

“And what?”

She took another towel and wrapped it around herself, tucking in the end beneath her armpit. “What else?”

“Nothing important.”

“What’s that for?” She pointed at the legal pad.

“I needed to take some notes.”

“About what?”

“A work thing.”

She turned to the mirror and asked, almost casually, “Are you excited about the baby?”

Winn was silent.

“Are you?” Biddy prodded.

“Yes,” Winn said. “No.”

“No, you’re not excited?” She and Daphne had the same way of wrinkling their foreheads when their plans went awry. “What were you going to say when you came in here?”

He tapped the legal pad against his thigh. “I’m not sure.”

“Winn, out with it.”

“Fine. I was thinking about saying we shouldn’t jump into anything. We didn’t exactly plan this.”

“We always said we would have two.”

“We hadn’t talked about it in years. Maybe four years.”

“No, we talked about it last year. On Waskeke. At the bar in the Enderby. You said you’d like to try for a son.”

“We’d been drinking, and that was still a year ago.”

“I didn’t think it was empty talk. We always said we’d have two. I understood our plan was for two. We always said so.”

“I thought … I assumed, apparently incorrectly, that we’d both cooled on the idea.”

“You should have said if you’d changed your mind.”

“You should have said you wanted another one.”

“Let me ask you this, if you could know right now that it’s a boy, would we be having this conversation? Would you have made one of your lists? That’s what you have there, isn’t it?”

He hid the pad behind his back and soldiered on. “I didn’t know you’d gone off the pill,” he said. “Did you do it on purpose?”

She rummaged in a drawer. “I forgot for a week. I know you don’t like to be surprised, but I thought we wanted this. I thought if it happens, it happens. I didn’t realize you had changed your mind. You should have said something.”

“I didn’t know I had to. I didn’t realize I had given tacit approval to conceive a child at the time of your choosing.”

He stepped back in time to remove himself from the path of the slamming door. The bath began to run. Biddy’s sisters said that Biddy was drawn to water in times of need because she was an Aquarius. Winn put no stock in astrology—the whole concept was embarrassing—but he admitted that his wife’s passion for baths, showers, lakes, rivers, ponds, swimming pools, and the ocean was a powerful force. Biddy descended from a line of people who were at once remarkably unlucky and extraordinarily fortunate in their encounters with the sea. Since a grandfather many greats ago had managed to catch hold of a dangling line after being swept by a wave from the deck of the Mayflower and be dragged back aboard, her forebears had been dumped into the ocean one after the other and then, while thousands around them perished, been plucked again from the waves. A grandaunt had survived the sinking of the Titanic; a distant cousin crossed eight hundred miles of angry Southern Ocean in a lifeboat with Ernest Shackleton; her father’s cruiser was sunk at Guadalcanal, and he saved not only himself but three others from shark-infested waters. The grandaunt’s photograph, a grainy enlargement of a small girl wrapped in a blanket and looking very alone on the deck of the Carpathia without her nanny (who had gone to the bottom of the Atlantic) hung in their front hallway.

Whatever the root of Biddy’s affinity for water, as long as Winn had known her, she had been able to submerge herself and come out, if not entirely healed, at least calmed, her mood rubbed smooth. But he could not have anticipated that she would emerge from this particular bath and find him where he had settled with the newspaper in his favorite chair and announce that she was going to have a water birth for this baby.

“A what?”

“A water birth. You give birth in a tub of warm water. There’s a hospital in France that specializes in it. We’re going there.”

Winn felt an “absolutely not” pushing its way up his throat. He had married Biddy partly because she was not given to outlandish ideas, and he felt betrayed. But the rafters of the doghouse hung low over his head. “Sounds like some kind of hippie thing to me,” he said.

“I’ve done research. Candace McInnisee did it for her youngest, and she swears by it.”

“You did research before you knew you were pregnant?”

“We always said we would have two, Winn. And since you’re not the one giving birth, I don’t see why you should mind where it happens.”

Winn lifted his paper and let it fall, a white flag spreading on the floor in marital surrender. He held out his arms. She came close, leaned to kiss him on the forehead, and slipped away before he could embrace her.

LIVIA WAS BORN in France in a tub full of water, and she, like Biddy, had spent the years since her birth returning, whenever possible, to an aqueous state. She had once come home from a fruitful day in the fourth grade and declared that she was a thalassomaniac and a hydromaniac while Biddy was only a hydromaniac, which was true. Biddy’s love of water did not extend past the substance itself, whereas Livia loved all water but especially the ocean and its inhabitants. During her time at Deerfield, she had baffled Winn by organizing a Save the Cetaceans society and by spending her summers on Arctic islands helping researchers count walruses or on sailboats monitoring dolphin behavior in the Hebrides. She had passionately wished to join the crew of a vessel that interfered with Japanese whaling ships, but Biddy had managed to convince her that she would be more helpful elsewhere. Now she was studying biology at Harvard with plans for a Ph.D. afterward. She had made it clear to Winn that she thought his ocean-provoked existential horror was a bit of willful silliness. From the age of eleven, she had insisted on getting and maintaining her scuba certification and was always after Winn to do the same, though the idea held no appeal for him. He had snorkeled a few times and once swam by accident out over the lip of a reef, where the colorful orgy of waving, flitting life dropped into blackness. He felt like he had taken a casual glance out the window of a skyscraper and seen, instead of yellow taxis and human specks crawling along the sidewalks, only a chasm.

Winn had expected Livia’s passion for the ocean to fade away like her other childhood enthusiasms (volcanoes, rock collecting), but a vein of Neptunian ardor had persisted in the thickening stuff of her adult self. She spotted seals and dolphins that no one else noticed, and she was on constant watch for whales. A stray plume of spray was enough to get her hopes up, and after she had stopped and peered into the distance long enough to be convinced no tail or rolling back was going to show itself, she would blush and fall silent, seeming to suffer a sort of professional embarrassment. She claimed she would be happy to spend her life on tiny research vessels or in cramped submersibles, poking cameras and microphones into the depths as though the ocean might issue a statement explaining itself. His selkie daughter. How Livia could feel at home in a world so obviously hostile was beyond him, as was her willingness to lavish so much love on animals indifferent to her existence.

Daphne was the simpler of his daughters to get along with but also the more obscure. By the time she finished college, she seemed to have shed the serpentine guile of her infant self, or else her manipulations had grown so advanced as to conceal themselves entirely. He couldn’t be sure. A smoked mirror of sweetness and serenity hid Daphne’s inner workings, but Livia lived out in the open, blatantly so, the emotional equivalent of a streaker. Livia’s problem was a susceptibility to strong feelings, and her strongest feelings these days were about a boy, Teddy Fenn, who had thrown her over. She had seen too many movies; she did not understand that love was a choice, entered and exited by free will and with careful consideration, not a random thunderbolt sent from above. He had told her so, but she would not listen. She was angry at the world in general and Winn in particular, so he was angry with her in return. In the interest of familial peace, he would try to put everything aside for the wedding, and perhaps Waskeke would exert a healing influence, bring her back to herself.

He needed to buy more groceries for dinner and to deliver Biddy’s lunatic flowers to the Enderby, where the Duffs were staying. With the aim of forging an alliance, he sought out Livia to see if she would come along. She was in the bathtub.

“It’s after two,” he said through the door, “so the sooner we go the better.”

“Where’s Celeste?” Livia asked.

“Up on the roof.”

“Communing with the vodka gods?”

“And with your mother.”

A splash. “Give me a minute.”

They rattled back down the driveway in the old Land Rover, the Duffs’ flowers blooming up from between Livia’s knees like a Roman candle.

“What do you say we take the scenic route?” Winn said, pausing at the road.

She shrugged. “I thought we were in a hurry.”

Only to get out of the house, he thought. In the hour since his arrival, he had managed to offend Biddy by suggesting that all the test runs with makeup and hair and such were an extravagance and also to walk in on Agatha in the downstairs bathroom. He hadn’t seen anything, only her surprised face and bare thighs (the gauzy white dress concealed their crux) and a wad of toilet paper clutched in her hand, nor had he said anything, which made the situation worse. He had closed the door—not slammed it but closed it quietly and deliberately—before fleeing up to the widow’s walk to tell Biddy he was going to the market.

The day was warm and unusually still. Split-rail fences and a thickety layer of brush hemmed in the road. The interior of the island was occupied mostly by scrublands called the Moors, low hills with sharp, rusty vegetation and bony, crooked trees, like a piece of the Serengeti delivered to the wrong address. On the ocean side, shingled houses were scattered among scrub pines, cranberry bogs, and marshes. They drove past the undulating, sand-trapped meadow belonging to the Pequod Golf Club, its ovoid greens marching off like footprints left by an elephant. Distant golfers bent and flexed, launching unseen balls into the blue air.

“Heard anything about the Pequod?” Livia asked.

“No, not yet,” Winn said, trying to sound cheerful. “I’ll have to call up Jack Fenn and get the latest.”

Livia let her head tip back until she was staring up at the Rover’s ceiling. “Would it be so bad not to join? You already belong to a thousand clubs. You hardly even go to half of them. I don’t see why belonging to the Pequod is so essential.”

“It’s not essential. Nothing is essential. I think we’ll all enjoy the membership, that’s all.”

“Can you leave the Fenns out of it at least?”

“Unfortunately, no. Look, they’re not my favorites, either, but Fenn and I go back long before you and Teddy were even born. We have a relationship that has nothing to do with you.”

“Not to mention Fee,” Livia said snidely, referring to Jack’s wife, Teddy’s mother, who was an ex-girlfriend of Winn’s.

“Ancient history,” said Winn. As a consequence of its selectivity, his world was sometimes too small. “No need to bring it up. Nothing to do with the Pequod.”

“No one besides you even golfs,” Livia said to the ceiling.

“There’s a gym there, and a bar. They have nice events—dances, silent auctions, theme parties. You’ll like it.”

She let her head roll in his direction. “I do love silent auctions.”

“Don’t be sarcastic, Livia. It isn’t ladylike.”

For three summers Winn had languished on a secrecy-shrouded wait list for membership in the Pequod. For three summers he had kept bitter evening vigils on the widow’s walk, staring out at what he could see of the course from the house: only a scrap of the tenth hole, but that bit of grass was the gateway to a verdant male haven and confessional. In the decades he had been coming to the island, he had always thought of membership as something obtainable but deliberately left for later. So it was to his bafflement that he had pulled all available strings and schmoozed all relevant parties, including the Fenns, and still he found himself relegated to guest status. He had an excellent track record with clubs. Though no club could equal the pleasures of his college club, the Ophidian—a brotherhood of such importance that he wrote one Christmas newsletter exclusively for its members and another for the remainder of the Van Meter family’s acquaintance—he had joined other clubs, in New York and in Boston, one in London, all places where he could drop in for dinner and feel welcome and sit in a leather chair and read newspapers hinged on long wooden sticks. He belonged to more specialized clubs, too, for the purposes of swimming or golf or racquet sports, and none had ever hesitated to accept him as a member. But Jack Fenn was on the Pequod’s membership committee and Fee Fenn was on the social committee, and, truth be told, Winn never knew where he stood with them, if bygones were bygones or not.

To change the mood, he reached over and patted Livia’s bony knee. “So,” he said, playing jolly, “the big day!”

“It’s not my big day.”

“Don’t be sour. Your day will come.”

She moved her leg irritably, and the flowers trembled. “I wouldn’t mind if everyone would stop telling me that. I’ll either get married or I won’t. I’m not jealous. I’m looking forward to this weekend being over. End of story.”

“That’s not quite the spirit, Livia.” Yearn as he might for the end of the wedding hoopla, Winn knew he must ride in front of the troops, sword raised, toward a successful event. “Especially from the maid of honor. You’re in charge of honor.”

He meant it as a joke, but she said, grimly, “I thought you weren’t impressed with my honor.”

He refrained from answering. They passed a marshy pond crowded with cattails and bulrushes.

“Look at the egret,” she said

Winn glimpsed a tall, slender shape and a flash of white wings. “It’s a heron,” he said.

“No, it’s an egret. Egrets are white. Herons aren’t.”

“Well,” said Winn in a voice that signaled he was being kind but not sincere. “All right.”

In town, the traffic was slow, and without a breeze the car was warm. Livia shifted the flowers, and some greenery tickled Winn’s hand. He pushed it away. Livia sighed and rested her elbow on the window’s edge. “All these people. Too many people.”

“Hopefully they’re not all wedding guests,” he said.

She snorted. “Do you have any idea what it’s like to share a room with Celeste?”

“I think I can imagine.”

“After the lights are out, I hear ice cubes rattling around. Then she tries to get me to girl talk with her and whispers questions about my love life until she falls asleep, which is when she starts snoring. You can’t imagine. She sounds like someone trying to vacuum up a mud puddle.”

Many times in the past, over holidays or vacation weekends, Winn had been kept awake by Celeste’s industrial rumble from several rooms away, but he said, “Buck up, pal. I’d appreciate if you’d contribute by being nice to your aunt.”

“I contribute. I contribute in lots of ways. I’m the maid of honor. I’m a servant to the pregnant queen. Why do I also have to be a companion to the drunken aunt?”

“Celeste has had some rough breaks along the way. The charitable thing would be to cut her some slack.”

“She’s a gargoyle.”

“She’s a ruin.”

“Of her own making. I can’t get away from her. She’s everywhere with her martinis and her stories. She’s like, ‘Roomie, did I tell you about the time my third husband ran off to Bolivia with my best friend’s daughter? You don’t know heartbreak until your third husband has run off to Bolivia with your best friend’s daughter.’ That clink-clink, clink-clink, clink-clink that lets you know she’s coming—it’s like the shark music in Jaws.”

“Be thankful you weren’t around for that divorce, the Bolivian one. That was a dogfight.”

“I don’t think a divorce that happened twenty-something years ago is an excuse for her to be a complete mess.”

“What do you propose we do?” Winn said. “Should we put her in a burlap sack and push her off the ferry?”

“The sack is probably overkill.”

“If she wants to get drunk and say the wrong thing, then that’s what she’s going to do. And as much as we’d like for her not to exist, she does. Death, taxes, and family, Livia.”

THE FARM might have been the end of the earth. A thin seam of ocean sealed its fields to the sky, all of it coppered by the sun. The water’s surface, choppy and striated with light, was beautiful, but Livia liked to think about what was teeming underneath: phytoplankton, of course, stripers, bluefish, bonito, maybe tuna, certainly fish larvae and fry, worms and mollusks in the sea floor. Pelicans diving to fill up their huge mouths. Seals. Perhaps a whale, although they were rare around Waskeke. In previous centuries, the islanders had hunted sperm whales and right whales almost to extinction, and Livia suspected the animals still picked up bad vibes from the surrounding waters.

The older she got, the more claustrophobic she felt within her family. Her father’s desire to join clubs had once seemed perfectly normal but now struck her as grasping and embarrassing. He seemed to believe his various clubhouses, stuffy old buildings full of stuffy old people, were bunkers that would shelter him from the fallout of ordinary life, protect him like the green fence out in the yard was supposed to keep his precious vegetables safe from the menacing deer. Teddy had felt a similar skepticism about his own family, and she had imagined that together they could forge a new freedom, make lives of their own, but then he had left her, an outcome she could not accept. She kept turning the breakup around and around in her mind like a Rubik’s cube, unable to puzzle out what had driven him off. She had never been so happy as she was with him. He had been happy, too—she was sure of it.

“For Christ’s sake,” her father said, waiting for an old lady to maneuver her Cadillac out of a parking space in the market’s gravel lot.

The market building, towering over a clump of greenhouses, resembled an enormous, gray-shingled schoolhouse. Livia got out first and walked ahead. Inside, the market was airy and cool and smelled of field dirt, tomatoes, cold meat, and cellophane. Her father caught up with her, peering over his glasses at a list he’d written on a napkin. “Corn, tomatoes, lettuce, I brought cocktail onions from home, we need pickles, we’ll get shrimp at the seafood place, we’ll get smoked salmon at the seafood place, something-not-shellfish for Dicky, lobsters are being delivered, then bread, cheese, et cetera, et cetera. You get the corn first, please, Livia.”

“How much?”

“We’ve got seventeen for dinner, so why don’t you get twenty ears.”

“Do you have a cauldron to cook it all in?”

Tilting his chin down, he gave her one of his trademark looks, half smiling, steely eyed.

“Okay,” she said. “Never mind. No problem.”

She found a cart and was steering it toward a tasseled mountain of corn when she saw Jack Fenn and his daughter Meg standing beside the refrigerated shelves of fresh herbs. Even from the back they were easy to identify because they, like Teddy, were redheads. Six months had passed since she’d last seen Jack, since before the breakup, but he looked the same, like Teddy but older. He wore a blue shirt with the collar undone, and he was handsome in a rough, shaggy-dog way, with full lips and thick marigold hair that was long enough to cover the tops of his ears. He was holding Meg’s hand, a market basket over the crook of his other arm. Meg was a tall girl, a woman really, and she was dressed with perfect neatness, like a child in a school uniform: oxford shirt, webbed belt, broomstick legs poking out of Bermuda shorts and into a set of ankle braces, beneath which her long feet in gray sneakers nosed each other like a pair of kissing trout. Her hair was in a French braid, exposing the hearing aids she wore in each ear, and her face might have been pretty if not for the wide, crooked mouth that slanted open, revealing teeth and darkness. Jack asked her something—Livia could not hear what—and she replied with a round, deep burst of sound like four or five words spoken all on top of one another. Shoppers looked up from their lettuces and bell peppers. Jack set down his basket and reached for a bag of baby carrots, still holding her hand.

Livia turned to find her father. He was holding a tomato in front of his nose and frowning at it. With as much stealth as she could muster, she abandoned her cart and slunk toward him, her back to the Fenns. Catching sight of her, he said loudly, “Livia, would you find me some black peppercorns?” Grasping his arm, she tried to turn him toward the door, but he stood as though hammered into the floor. “What are you doing?” he said. “I need tomatoes.”

“Can we just go? I’m not feeling well.”

That was true enough. Her desperation had become a sort of nausea. His eyes lit with worry, and he glanced once at her belly as though she were suddenly Daphne and pregnant and the object of great concern and pillow plumping. But Meg Fenn let loose another blast of her foghorn voice, and he looked up.

“Fenn!” Winn called boisterously over Livia’s head. “Jack Fenn!”

Jack lifted a hand and walked in their direction with Meg shuffling beside him, her trout feet tumbling over each other.

“Winn,” Jack said. “Hello, Livia.” He leaned in to kiss her cheek, and she felt the corner of her mouth spasm. She prayed she would not cry. Her father’s hand twitched toward Meg and then veered back and froze into a signpost pointing at Jack. Jack set down his basket and allowed Winn to pump his broad paw. Livia put her arms lightly around Meg, who stood very still to receive her embrace. “I like your belt,” Livia said. She noticed the girl was wearing lip gloss and remembered once seeing Teddy’s mother applying it, holding Meg’s chin in her hand.

Jack turned his green eyes on Livia, Teddy’s eyes, and she blushed, conscious of her thinness. “How are you?” he asked.

At the same moment, her father, radiating a sudden vigor, said, “Can you believe the traffic today?”

“I’m fine,” Livia said.

“Absolute pandemonium,” Winn said in answer to his own question.

Tripped up, they all hesitated, and gradually discomfort saturated the air as though puffed from an atomizer. The cause, Livia knew, would not be named or alluded to, not here beside the tomatoes or anywhere else where her father and Teddy’s father happened to be at the same time. Her father would rather die than acknowledge in Jack Fenn’s presence that, for five short weeks, the two of them had shared an embryonic grandchild. Nor had Livia ever spoken with Jack about her pregnancy. The last time she had seen him was in a different life, back before she had gotten knocked up, when Teddy was still her boyfriend.

“Have you been out on the links yet?” Winn asked Jack, a note of ingratiating fellowship creeping into his voice. His body was taut, humming with too much enthusiasm. The possibility occurred to Livia that he wasn’t even thinking about her but only about the golf club.

“Just once,” Jack said.

“Good!” Winn said. “Good! Glad to hear it.”

Meg spoke, addressing Winn. “You like golf?” she asked, vowels dwarfing her sticky, guttural k and g sounds. Livia had explained to her father a thousand times that Meg could understand him, but still he froze whenever he had to communicate with her. He stared, neck straining forward, pupils moving over her face in a rapid search for comprehension, and then he gave up and examined his wristwatch.

Meg repeated herself, louder, and Winn looked helplessly at Livia. With an apologetic glance at Jack, Livia translated. “She said, ‘You like golf?’”

“Oh. I do. Very much,” Winn told Livia.

Jack lifted his daughter’s hand and kissed it. Meg’s eyes and her wide mouth closed, making her face look, in its moment of repose, normal.

“Do you like golf?” Livia asked Meg, and Meg laughed like a honking goose.

“Say,” Winn said to Jack, “I heard somewhere that you’re involved in the bluffs project.”

“Unfortunately.”

Winn chuckled. “Fenn versus nature.”

“The lighthouse is set to be moved next summer,” Jack said. “But that’s the easy part.” He went on about some scheme to shore up a disappearing beach with drainage pipes and to reinforce crumbling bluffs with rebar, concrete, and wire baskets of rocks called gabions. A line of expensive houses sat atop the cliffs, and every year their owners paid a foot or so of lawn in taxes to the wind and rain, the brink creeping slowly closer to their cedar porches.

“I hate to say it,” Winn said, “but those houses are goners. Five years and they’re in the drink.”

Livia saw an Atlantis of gray-shingled houses, weather vanes spinning in the currents beneath a white foam sky, fish at the windows and in the attics, the shadow of a whale sweeping over the roofs like the shadow of an airplane. She marveled at the two of them, chattering on like this. Her father claimed things had been awkward with the Fenns since his college years, when he had belonged to the Ophidian and Jack, a legacy, had not been invited to join. Then Winn had slept with Jack’s wife (long before Jack met her, but still), and Livia had slept with Jack’s son. Then Teddy had broken her heart. She had sacrificed their child. What could be more intimate? Probably she should be grateful the conversation was only about rebar and property values even if something in her was longing for them to acknowledge, just once, what had happened. Not likely. Even when she and Teddy were still together, relations between the families had been less than comfortable. The few times both sets of parents came together for dinners in Cambridge they had all bravely skated the hours away on a thin crust of chitchat.

Jack shook his head. “I have to say I hope you’re wrong, Winn. That wouldn’t do the island any good.”

Winn raised a finger. “But you didn’t build there, did you? No sense taking that kind of risk when you’re finally getting your own place. Rent on the bluffs, buy on the flat.”

“I don’t know—we considered building there. Of course, we’re still renting. The new house won’t be livable until the end of the summer. Even that’s not for sure. How is your family? The wedding’s soon, isn’t it?”

“Saturday,” Livia said.

“Just a small affair,” Winn said. “Mostly family.” He touched his chin. Livia guessed he was worried Jack would feel slighted.

Jack said, “Remind me of the groom’s name.”

“Greyson Duff,” said Winn. “It’s a fine match. We’re all very pleased.”

“Congratulations,” said Meg, and Jack kissed her hand again.

Livia was astonished to feel her father’s fingers clasp her own, once, quickly, and then release. The touch was something between a caress and a pinch. She could not remember the last time he had held her hand. “Thank you,” she said to Meg.

“How is Teddy?” Winn asked.

Heat crept into Livia’s face. She willed herself to hold her gaze steady, not to fold her arms. Jack smiled. He had always been kind to her. “He’s fine,” Jack said. “In fact, he’s made a very big decision.” Livia braced herself, though she did not know for what.

“Oh?” said Winn.