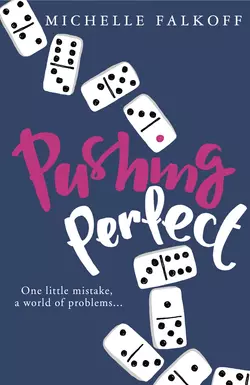

Pushing Perfect

Michelle Falkoff

Kara Winters is always striving for perfection. But when her anxiety takes over, the price of perfection spirals out of control…'Perfect' Kara Winters has always hated her nickname. Especially now that she no longer lives up to it. She used to have normal friends, she used to be normal. Now all she wants is to get into Harvard and leave high school behind.So when the pressure to ace her exams finally gets to her, Kara does one tiny bad thing, just to help out, to ease the stress. If it will help Kara get a perfect exam score and one step closer to a new life, it’s a price she’s willing to pay.But she never expects to get caught out. Or that Alex, Raj and her other not-so-perfect new friends might get embroiled in a horrible mess that could ruin all of their futures.Sometimes perfection isn't what it's cracked up to be.

Copyright (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

First published in the USA by HarperTeen, a division of HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Spilled Ink Productions, 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover illustration © Anneka Sandher

Michelle Falkoff asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008110697

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008110710

Version: 2016-11-16

FOR MY PARENTS

Contents

Cover (#u172e51a2-3768-5c13-a49a-3b233f842f1b)

Title Page (#u76412ee7-f283-55c3-8b78-cdebd918d427)

Copyright

Dedication (#udaa89e8b-a49c-570e-9df4-c9cd136b614c)

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Michelle Falkoff

About the Publisher

1. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

During the summer between eighth and ninth grade, I turned into a monster.

It didn’t happen overnight; it’s not like I woke up one day, looked in the mirror, and let out a dramatic scream. But it still felt like it happened really fast.

It started at the pool with my two best friends, Becca Walker and Isabel DeLuca. School had just let out for the summer, and though the weather still felt like spring, the sun was out and the pool was heated and Isabel had a new bikini she wanted to show off. Normally she hated going to the pool with us, since Becca and I spent most of our time in the water swimming laps to practice for swim team tryouts, but Isabel had gotten all curvy and hot and kind of boy crazy, and there was a new lifeguard, so getting her to come with us wasn’t that hard.

We couldn’t get Isabel to actually swim, but that was okay; Becca and I spent most of the day racing. I usually won when we swam freestyle, but Becca always killed me in the butterfly. I was terrible at butterfly. We raced until we were exhausted, and then we got out of the water, dripping in our Speedos as we headed for the showers.

“Your butterfly’s getting better,” Becca said, stretching her long, muscular arms over her head. With her wingspan and power I’d never catch her in butterfly, but it was nice of her to say I was improving. Becca was always nice. Isabel was a different story.

“Thanks,” I said. “Not sure it will be good enough to make the team, though.”

“You never know. We don’t have to be perfect to get on. We just have to be good enough. And if you talk to your parents, we’ll be able to spend the whole summer practicing.”

The goal was for me to stay with the Walkers for the summer, instead of going on the family trip my mom was planning. Dad had just gotten forced out of his own start-up once it went public, and Mom thought he needed to get away while he figured out his next move. She’d rented a condo in Lake Tahoe for the whole summer, and I really, really didn’t want to go. I hadn’t brought up the idea of staying behind with the Walkers yet, though, since I was having trouble imagining my parents saying anything but no. “I’ll do it soon,” I said. “I’m just waiting for the right moment.”

We both rinsed quickly under the showers and then pulled off our swim caps. Something stung as I removed mine; I reached up to my forehead to feel a little bump there. I ran over to the mirror to look at it as Becca shook her braids out of the swim cap. “I’m going to miss these when they’re gone,” she said.

“Are you sure you can’t keep them?” The bump hurt a little, though all I could see was a spot of redness, not the protrusion I’d have thought based on how it felt. I took my hair out of its bun and brushed it over my face so Becca and Isabel couldn’t see the bump. They’d always teased me for having perfect skin, and I knew they’d find it amusing that I didn’t anymore.

“Braids are way too heavy for swimming. Besides, you promised we’d cut our hair off together. You’re not going to bail on me, are you?”

“Nope. I’m in.” I’d never had short hair before, and besides, what did it matter? I always wore my hair in a bun or a ponytail anyway. It was kind of handy to have long hair now, though, to cover this thing on my face, which was starting to throb.

We went out to tell Isabel we were done for the day. She was lounging on a towel near the lifeguard station, where some cute high school guy was sitting in a tall chair that gave him a perfect view of her cleavage. “Finally!” she yelled. “I thought you guys were going to stay in the water forever. I’m bored. Let’s get frozen yogurt.”

“Can’t today,” I said. It wasn’t true, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the red bump. I just wanted to go home.

“Suit yourself,” Isabel said. “We’ll just go without you.”

Usually that was enough to get me to change my mind; I hated feeling left out. It wasn’t going to work today, though. “Have fun,” I said, and texted Mom to pick me up.

“Come over later,” Becca said. “We’ll be at my house.”

“I’ll see if I can,” I said. Maybe the bump was just a temporary thing. I watched them walk away and then pulled my hair back into a bun as soon as they were gone.

“Oh, sweetheart, it looks like you’ve got a pimple,” Mom said when I got in the car. “I can put some concealer on that when we get home.”

Trust Mom to see a problem and immediately want to fix it. That was her job back then, after all; she had a risk-management consulting business and helped all the local venture capital firms decide what kinds of investments were safe. “Better to identify issues when they’re small,” she’d say, but I’d heard her talking to Dad about work when she thought I wasn’t listening, and I knew a big part of her job was helping cover stuff up.

When we got home, she marched me straight into the bathroom, put the toilet seat down, and made me sit while she dug through her cabinets for makeup. I snuck a look at the bump, which seemed like a whole other thing from the whiteheads and blackheads Isabel and Becca complained about. Their zits were angry little dots, vanquished by a fingernail or an aggressive exfoliating scrub. Mine had begun to throb like a furious insect under my skin, just waiting for its moment to break through and escape. Maybe it wasn’t even a zit. Maybe it was a spider bite. Or a parasite.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Mom said when I suggested it. “Now hold still.” She squeezed some concealer onto the space on her hand between her forefinger and her thumb, rubbed it all together with a delicate brush, and dotted it gently on my face. “You have to have a light touch, or else it will cake up.”

I tried not to roll my eyes. Mom was just trying to be helpful, I knew, but all I could think of was what Isabel would say if she could see me now. She’d been begging her mom to let her wear makeup since we started middle school; she’d finally gotten permission this year, and now every time we went to the mall, she dragged Becca and me to the cosmetics counters in the makeup stores. One time she’d pressured one of the salesladies into giving us makeovers, one of those older women whose face looked like a smooth mask and who wore a lab coat, as if wanting to look prettier was some kind of science project. She’d covered Becca’s face with foundation a shade lighter than her dark skin; she’d slathered me with bronze eye shadow and coral lipstick and made my freckles disappear. We were both miserable.

Isabel wasn’t willing to concede defeat, though. “Okay, we’ll have to try another place,” she said. “But just wait until school starts and you see all those cute boys. We’ll need everything we’ve got to compete.”

She made it sound like a swim meet. “Meeting boys is not a sport,” I said.

Isabel laughed. “It is if you do it right.”

She would know better than we would. She was the first of us to get a boyfriend; Becca and I had just nursed crushes all year. “You guys need to ditch the Speedos and get some bikinis,” she’d say. “You’re totally missing out.”

Missing out on what? I wanted to ask her. From what I could see, getting a boyfriend meant letting some kid who was shorter than me lick my face in public. When I imagined kissing a boy, it was more romantic, private. Less messy. I was happy to wait until high school, where I dreamed there would be boys who were at least as tall as I was. I was sure that in their presence my awkwardness would magically disappear.

“Perfect Kara wants a perfect kiss,” Isabel would say.

I hated when she called me that. It was an old nickname, from back when one of my grade school teachers had used my scores on math tests to try and motivate the class. “Look at Kara—one hundred percent perfect, every time.” I’d felt my face turn red under all the freckles and prayed that no one was paying attention. But everyone was, and I’d never lived it down. The only person who’d never called me Perfect Kara was Becca.

Well, I wasn’t so perfect now. “There we go,” Mom said. “No, wait, it’s not blending properly. Let me just put on a little something else.” She went through bag after bag of makeup, which was kind of funny, since it wasn’t like she wore so much herself. The bag she settled on had a bunch of shiny lips on it.

“No lipstick,” I said.

“No lipstick,” Mom agreed. “This is where I keep my foundation.”

I was tempted to ask why she’d keep foundation in a bag covered with lips, but I didn’t want to seem too interested in her makeup collection. Mom pulled tubes and compacts out of the bag, opening and closing them, grabbing my wrist and putting samples of skin-colored creams on them, frowning, digging back in the bag. Finally, she found a shade she liked. She patted some liquid on my forehead and cheeks with her fingertips, then smeared it around with a little triangle-shaped sponge. “Close your eyes,” she said, as she opened a compact filled with beige powder and then reached for an enormous fluffy brush. I obeyed and tried not to sneeze as she swept the powder all over me.

“You can open your eyes now.” I did, and then watched her inspect my face. She smiled, and I worried that meant I’d be dealing with another horrible mask, like the lab-coat lady had given me. I must have looked like I was going to freak out, because Mom laughed. “I promise it’s not as bad as you think. Come on, check it out.”

I stood up and turned to look in the mirror. At first I was confused but relieved: there was no thick mask, no scary unrecognizable me. And no zit. But there were also no freckles; my skin looked smooth and soft. Really, it was kind of nice. If lab-coat lady had done something more like this, maybe I wouldn’t have taken such a hard stance against this stuff.

“So?” Mom asked. “Was I right?”

She knew how much I hated admitting it, but at the same time, she’d made it easier for me to decide what to do. I’d rather Becca and Isabel make fun of this makeup than the horrible monster zit. “Yeah, you were right,” I said. “Thanks.”

She kissed the top of my head. “Excellent. This was fun, wasn’t it?”

“I guess.” It actually had been. It reminded me of when I was little, when Dad’s first start-up had just taken off and he was at work all the time. Mom and I had spent hours at the kitchen table doing logic puzzles together. At first it had been great, having so much of her time and attention, when normally she was almost as focused on work as Dad was.

But then she’d figured out that I was really good at those logic puzzles, really good at math in general, and all of a sudden everything was about school. She started asking more questions about what we were doing in class, whether it was hard for me or whether I was bored, and when I made the mistake of admitting that I didn’t find any of it all that difficult, she started giving me extra homework. “You’re gifted,” she said. “Pushing yourself is the only way to get better.”

Better at what? I wanted to ask her, but I had a feeling I knew the answer. Better at everything. It would never end. At least not until I was perfect. Maybe that was why I was so freaked out about this one zit. I knew I wasn’t perfect, but I didn’t need my face to broadcast it.

“It’ll be nice to spend more time with you this summer, when we can relax,” Mom said.

There it was—my opening. But I felt bad trying to get out of the trip after she’d just finished helping me. There would be another time. I just nodded.

“I told Becca I’d go over to her house,” I said. “Can I?”

“Of course,” she said. “Let me know what the girls think about the makeup.”

“I will,” I said, though I hoped they wouldn’t notice it.

No such luck.

“Something’s different,” Isabel said as soon as I got to Becca’s house.

We were in her bedroom, where we always hung out. It was huge, almost more like a suite, and she’d set it up like a studio apartment: bed and dresser on one side, and a little lounge area on the other, with a love seat and two chairs. I sat in my usual chair and slung my legs over the side; Becca was in the other chair, her legs crossed. Isabel relaxed in the love seat like she was waiting for someone to feed her grapes. Becca had lit one of those big scented candles in a jar, so the room smelled like cantaloupe.

“I don’t see it,” Becca said. “T-shirt, Converse, cutoffs.” Just like hers.

“We really need to go shopping this summer,” Isabel said. “But seriously.” She tilted her head and looked at me more closely. “Wait, I know. It’s the freckles. They’re gone. What did you do, soak your face in lemon juice?”

“Don’t be mean,” Becca said.

“I’m not. I’m evaluating. Stand up.” I did, and she gave me the up-and-down look she was becoming notorious for. “Makeup,” she said. “Kara Winter’s wearing makeup.” She waved her hand in front of her face as if it were a fan. “My stars,” she said, in a fake Southern accent. “Our little girl’s growing up.” Then she collapsed back onto the couch. Always the drama queen. I sat down too.

Becca frowned. “I thought you hated makeup. You said you’d never wear it. What’s changed?”

“Nothing.” I hated lying to them, but if I told them about the zit, Isabel would make a Perfect Kara joke and Becca would feel bad for me, and neither one of those things was appealing. Isabel had a way of finding my most sensitive spots and poking them with a sharp stick, and I was getting tired of it. And Becca’s pity just made me feel like I wasn’t good enough to be her friend. I hated feeling like I wasn’t everything people wanted me to be. Better to hide the feeling with a little concealer.

“Was it your mom?” Becca asked. “Did she talk you into this?” She made it sound like my mom had tattooed my face while I slept.

“Smart to try to soften her up,” Isabel said. “Did you ask her?”

I shook my head.

“You missed the window,” Isabel said. “You have to just do it. Be bold!” She raised her fist in the air.

If only it were that easy. “I still don’t know what to say. They’re making such a big deal out of this trip.” No one knew how much my parents really needed this. They’d been fighting a lot lately; Dad was really stressed about finding a new idea, and Mom had taken on more work to make up for his lost salary, so she was exhausted. She’d been talking about our vacation for months.

“You just have to make it easy for them to say yes,” Isabel said. “Tell them you’ve already worked it out, that Becca’s mom already agreed to it.”

“Tell them you’ve got a lifeguarding job,” Becca said.

“I don’t want to lie to them.”

“You wouldn’t be lying,” she said. “My old camp counselor is in charge now, and she said we can work there if we want. We just have to go meet with her before camp starts in two weeks.”

“Becca, that’s amazing! Is there drama stuff there Isabel can do? Then we can all be together.” I was getting excited enough that the idea of asking to stay home seemed less scary than it had just a few minutes ago.

“I signed up for a drama camp in San Francisco,” Isabel said. “I’m not about to spend that much time in a pool with you losers. My hair will turn green.” She blew us a kiss, which took away some of the sting of her calling us losers, though I already knew she was kidding. Isabel said stuff like that all the time.

“We’ll just have to find a way to live without you,” Becca said. “We’ve got a lot of work to do before swim tryouts.”

I felt a wave of nausea. Swim tryouts. Becca and I had been practicing all year; keeping our schedule was one of the reasons I didn’t want to go on vacation. But I had no idea whether we’d be good enough. What if one of us made it and the other didn’t? I’d never been in that high-pressure a situation before, and just the thought of it made me anxious. The only way I’d feel better was if I spent the summer practicing, and for that, I had to be here.

And then a new fear kicked in. What would happen if they spent the summer without me? They’d been friends first; I’d met Becca through swimming, and Isabel through Becca. Though the three of us were close now, I’d always felt like it was temporary, like they could go back to being a twosome at any time. They’d done it before, after some stupid fights in middle school, and I remembered the ache of that loneliness. What if they had an amazing time with me gone, and didn’t want me back? My thoughts started to spiral. What if they saw the zit and decided they didn’t want to be seen with me at school? I was being ridiculous; I knew. It was just one zit.

“Don’t worry,” Becca said. “Your freestyle is amazing, and we’ll keep working on your butterfly. We’ll be great. We just have to make sure we aren’t separated this summer. You have to sell it.”

“I will,” I said. “I promise.”

When I woke up the next morning, the horrible monster zit had multiplied by five. I asked my mother to go to the store and get me some benzoyl peroxide, like I’d seen advertised on TV. I didn’t ask her about staying with Becca; instead, I stayed in the bathroom and practiced putting makeup on by myself. It was a disaster.

The day after that, there were ten. They were hard and red and they hurt. I kept looking at myself in the mirror, hoping I was imagining them. But they didn’t go away. I got back in bed and stayed there all day, trying to avoid envisioning showing up for my first day of high school looking like this.

With every day came more angry red bumps, throbbing away under my skin. The benzoyl peroxide didn’t do anything. Becca called, and I told her I had a weird summer cold so I could avoid seeing her. I knew Becca probably wouldn’t think the zits were a big deal; she’d be sympathetic and supportive, like she always was. But behind her support would be that pity, and I couldn’t bear the thought of it. And Isabel—Isabel wouldn’t want to hang out with a monster. Not if it would interfere with her social life. Becca would have to choose, and why would she choose me? She and Isabel had the history; all I had was swimming.

Maybe the monster face was just a summer thing. Or maybe Mom could help me find a doctor who could give me medicine to make the zits disappear. Or she could teach me enough about makeup that I could hide them myself. I just needed some time. I realized I wasn’t just avoiding asking Mom about staying with the Walkers; I’d decided I wasn’t going to ask at all.

Once I had so many red blotches on my face that my freckles had all but disappeared, I called Becca. “Mom said no,” I told her. “I tried as hard as I could.”

“That sucks,” she said, not bothering to hide her disappointment.

“I’m sure Isabel will be fine with it.”

“Don’t say that.” Becca knew I worried sometimes that Isabel just tolerated me. “She’ll miss you as much as I will. Have a great time, and make sure to find somewhere to practice. And I’ll make hair appointments for us when you get home.”

“Sounds great,” I said, though I couldn’t imagine cutting off all my hair with this face. I’d worry about that when the time came.

I got off the phone and told Mom I wanted to see a doctor before we went to Lake Tahoe. And that I wanted to go buy some makeup.

By the end of the summer I had a diagnosis: papulo-pustular acne, which basically meant that my whole face and neck were covered with zits. I had a dermatologist I would see every week who told me chlorine might have triggered the initial breakout and I should give some serious thought as to whether continuing to swim was a good idea. I didn’t get in the water all summer.

By the time school started, I had two new regimens: drugs and makeup. Every day I got up, took my pills, and counted the cysts to see if there were fewer than the day before, writing the numbers down in a notebook I kept in the bathroom. And then I slathered my face with foundation, along with a little eye shadow and lip gloss so the foundation didn’t look weird. Self-evaluation, cover-up, and makeup.

SCAM.

2. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

The Brain Trust was occupying its regular table when I came into the cafeteria with my brown bag lunch. As always, I had to walk by the drama table, where Isabel hung out with her theater friends, and the swim team table, where Becca sat. They didn’t look up when I passed them by. They never did.

Mom had made me spinach salad with quinoa and feta and a lemony dressing. Brain food. She’d done a ton of research into my skin condition and had made me try a million different diets that, just like everything else, did nothing. She’d amped up her game in anticipation of the SAT exam. The test was coming up in a little over a week, and though I’d studied so much I’d worn my Princeton Review guide to shreds, I was terrified to actually take it.

Ever since everything went down with Becca and Isabel, I’d buried myself in schoolwork, spending all my time writing papers and studying for tests and making sure I did as well as I possibly could. It was all I had left. I was still hiding my face with makeup, but sometimes it felt like I was hiding my whole self, too. Or that I didn’t have much self left to hide. By my count, it had been over a year since I’d talked to anyone about anything except school. Even at home, all my parents talked about was how well I was doing, how proud they were of my hard work; they didn’t seem concerned that I was always alone. Sure, Mom had asked about Becca and Isabel at first, but I’d mumbled something about people changing in high school and she’d let it go. I’d convinced myself that everything would be different if I went to the right college.

But I could only do that if I killed it on the SAT.

I’d always been good at taking tests, but the SAT was different. I don’t know if it was just the pressure of how much was riding on it, or if some secret part of me was convinced that standardized tests would somehow reveal how very not perfect I was, but I’d had a full-on panic attack when I took the PSAT—I hadn’t even finished it. I’d left the room before people could see me freaking out. I was so spooked by the thought of the SAT that I’d put it off until this year, rather than taking it as a junior like everyone else in my classes.

The Brain Trust was a group of kids I’d met in the Gifted and Talented Program back in grade school. We weren’t friends, exactly, but we had all our classes together, and we all shared the common goal of wanting to go to college on the East Coast. Harvard, specifically. Arthur Cho was a classical violinist whose parents didn’t want him to go to Juilliard because they thought it would limit his options; David Singer dreamed of being an entrepreneur like Mark Zuckerberg, even though I kept telling him what my parents told me, which was that Silicon Valley was full of Stanford grads who looked down on people from Harvard. Julia Jackson, my nemesis, was gunning for a particular science scholarship and wanted to go straight from undergrad to Harvard Med.

As for me, I just wanted to get as far away from Marbella as possible. I liked the idea of Harvard because it seemed like the kind of place I could start over, where everything might be different. No one would know me as Perfect Kara there; at a place like Harvard, it would be normal to love math and to care about academics more than anything else. It didn’t necessarily have to be Harvard; any good school out east would do. My last name was Winter and I’d only ever seen snow in Tahoe. I wanted red and orange leaves in the fall, tulips in spring, baking heat in summer. I wanted change.

“The National Merit Semifinalist list came out today,” Julia said, her voice all sugary. “Didn’t see your name on there.” Julia and I had been in classes together since kindergarten and teachers had been pitting us against each other the whole time. Handwriting competitions in first grade, speed-reading contests in second, multiplication table races in third—by then it had gotten old for me, but it never had for her. Now I was first in the class, but she was right on my heels, and I knew she’d made it her mission to pass me by.

“Nope,” I said, trying to keep my voice light. “I assume congratulations are in order?”

Julia nodded, as did the other two. Great. So I was the only one. “Well, I’m really happy for you guys.” And I was, but I could also feel the anxiety kicking in. It had become a familiar feeling—I’d get this wave of nausea, then a weird thumping in my head, and then my pulse would start to race. I’d feel cold but get sweaty, which was usually the point when I’d take a walk or something to calm myself down. They were sort of my friends, but they were also my competition, as my guidance counselor kept reminding me. The problem was that they each knew exactly what they wanted, and everything they did was in service of their goals. I had no idea what I wanted, other than knowing it had something to do with math, and that put me at a disadvantage. The only way to make myself stand out—the only way to have a real chance at a new life—was to be valedictorian at one of the most competitive public high schools in the country, which Marbella High was. And to nail the SATs.

Basically, I had to be perfect.

I had to put the SATs out of my head if I wanted to avoid an actual panic attack, though, so I turned to the immediate task, which was staying at the top of the class. Which meant acing next week’s calc and econ exams. “We should get out of here,” I said. “I don’t want to be late for class.”

We all had calculus next, which was my favorite class, with Ms. Davenport, who was my favorite teacher. Today was a review session for a test we had coming up, and I was actually looking forward to it.

The thing I loved about math was that you could usually tell when you got the right answer. Like the logic puzzles I used to do with my mom that I now did on my own, for fun: if seven girls go to a birthday sleepover and each one brings different gifts and snacks and has to leave at a different time the next morning, how do you figure out which is which, given a list of clues? There was something so satisfying about creating a chart, with little boxes for Xs and check marks, and drawing inferences from the clues that let you put all the pieces together. Calculus, with its graphs and equations, was similar enough to be fun.

I finished the practice test quickly, secure in the knowledge that I’d gotten all the answers right. It took another ten minutes or so for everyone else to get done, and then Ms. Davenport started going over the answers. She was such a great teacher—she walked through everything so carefully, I couldn’t imagine how anyone didn’t get it after that. She’d been the same way when I had her for geometry as a freshman, a class I found much harder than calculus. And she was cool, too—she dyed her hair auburn and wore it in fancy rolls like she was from the twenties, with vintage dresses and cowboy boots. She seemed so much younger than the other teachers, though I knew she couldn’t be as young as I thought she was, given how long she’d been teaching.

“Ready for the test?” she asked me, on my way out of class.

“Ready enough, I hope,” I said.

“I’m so not,” a voice said from behind me. “Ready, that is.”

I turned to see Alex Nguyen, a girl who was in my calculus and econ classes. I didn’t know her very well; she didn’t talk much in class unless Ms. Davenport made her, and we’d never done more than say hi in the hallway once in a while. Last year she used to fall asleep in class a lot but this year she’d gotten it together.

“It won’t be so bad,” I said.

“Oh, you’re just humoring me. This stuff is totally easy for you.”

I hated when people said things like that. They had no idea how hard I worked, how much pressure I was under. Sometimes it felt like I was treading water all the time, working as hard as I could to stay afloat. I just wanted to swim. Alex didn’t seem to mean anything by it, though. “I’m going to have to study all weekend,” I said.

“Want to study together? You can come to my house. I can even bribe you with food—my dad is a really good cook.”

My first instinct was to say no; my study habits were pretty set, and it wasn’t likely that working with her would help me. But then I remembered how my dad would make me teach the class materials back to him when he helped me study, and how much better I understood things once I could explain them. Maybe it would be good for both of us. And then I remembered something else.

“How are you doing in econ?” I asked.

“Oh, econ,” she said, with a wave of her hand. “Nothing to it.”

“Can we study for that too?”

“Really? You want my help?” Alex clapped her hands. “Totally! It’ll be fun. How about tomorrow?”

I had nothing but time. “Sure.”

“Give me your number and I’ll text you the address.”

We traded info as we walked to econ. I couldn’t help but feel kind of excited—the thought of going over to Alex’s to study actually sounded fun. I hadn’t gone over to anyone’s house in more than a year, and it had been even longer than that since I’d studied with someone else. Maybe we’d even talk about something other than classes, though the thought of it made me a little nervous. What did I have to talk about these days? I only hung out with the Brain Trust, and almost always at school—I hardly ever saw them outside it. Once in a while I went to the movies or the mall with Julia, but we both knew it was because we didn’t have anyone else to go with. Every time I swore I’d never hang out with her again; all she wanted to talk about was school, even after she and David started hooking up. I refused to ever study with her. The only person I’d ever had fun studying with besides my dad was Becca, and that was way back in middle school, before we got put in all different classes.

Of course, the minute I thought of Becca, there she was. It had been over a year since we’d last spoken, but I still missed her all the time. Isabel too, though not in the same way. Becca looked striking, like she always did; she wore smoky makeup around her green eyes and her dark skin was as clear and perfect as ever. She’d started to let her hair grow back, but just barely, so her head was covered in tight little black curls.

I still remembered the day she’d cut off her braids. I’d just gotten back from Tahoe, and as promised, she’d made us appointments at the same time. When she first suggested the haircuts, I thought it was a great idea; I liked the idea of us doing something together, something that would publicly mark us as friends. And it wasn’t like my long hair was so fabulous; it was a washed-out brown and not particularly thick, and I never wore it down anyway.

But then there was the skin. When things got bad over the summer, I got in the habit of taking down my bun and wearing my hair over my face. There was something comforting about it, like I was doing a better job of hiding the problem even just by virtue of covering myself a little more. Mom had gently suggested that if I was going to wear it down, I might want to brighten it up a bit, so I’d gotten a trim and some super subtle highlights and started paying more attention to how I styled it. Becca hadn’t seen it yet. She hadn’t seen my new clothes, either, or how much makeup I was wearing regularly now. Mom said I looked like a new person, all grown up and ready for school. I was just happy not to look like myself, now that looking like myself had become so scary.

The appointment was scheduled for the day after I got back into town. “We need to do this like ripping off a Band-Aid,” she said. “No chickening out.”

I should have just told her then. Instead, I showed up at the hairdresser late. Becca was sitting in the chair covered in an apron, her braids already half gone. Even before the haircut was over, it was clear she could pull it off; she had a really great-shaped head.

“You’re back!” she said, as I approached the chair. “I’d get up and hug you, but you see what’s happening here.” She pointed at the hairdresser, who held up a big pair of scissors.

“I sure do,” I said. “You’re really going for it.”

“We’re really going for it,” she corrected. Then she paused and looked at me. “Come here.”

I came closer. She reached out and touched my hair. “You got highlights,” she said. “And layers.”

I nodded.

“You’re not going for it.”

“No,” I said, quietly.

“You’re kidding. What happened? We had a plan.”

The hairdresser moved the scissors away from Becca’s head. “I’m going to give you girls a minute,” she said, and went into the back.

“I know we did, and I’m really sorry,” I said. “But you know I’ve never had the same trouble with the swim cap thing as you, and I did that thing where you upload a picture and try out different hairstyles online, and I look awful with short hair.” That was only kind of a lie—I’d done it, and I didn’t look great with short hair, but that wasn’t the real reason. It was time for me to just tell her the truth. I hated keeping secrets, especially from Becca; I never had before. I opened my mouth to say more, but I thought about having to tell Isabel, and I wondered whether I could ask Becca to keep my secret for me. Was that too much to ask her? I wasn’t sure what to do.

I didn’t have to decide what to say next, though, because Becca had already made up her mind. “You should go,” she said. Her voice was cold, and I knew she was furious. Becca wasn’t like Isabel, who yelled and screamed whenever she was pissed off. When Becca was mad, she got very, very quiet. “If you’re not keeping your appointment, you don’t need to be here.”

That was the moment I should have said something. But I didn’t. “I’ll make it up to you. I promise.” That was kind of a lie too, since I had no idea how, but I didn’t know what else to say. And I didn’t want to ask her to forgive me, because I was afraid she’d say no. So I just left.

We’d gotten over that eventually, just as we’d gotten over other things in the past. We hadn’t yet reached our limits; it would take nearly two years and a lot more than a haircut for our friendship to end. But eventually, it did. So when Becca and I made eye contact in the hall, I saw the flash of emotions that passed over her face whenever she saw me: sadness, confusion, a little bit of anger, resignation. I imagined mine probably weren’t all that different.

And then we both looked away.

3. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

Alex lived in a subdivision not too far from mine. The only way to tell it was different was the style of the homes—in my neighborhood it was all ranch houses, but in hers there was a little bit of variation, though not much. Marbella didn’t have a lot of architectural range. Alex’s house was almost identical in layout to Becca’s; it felt familiar, which made me nostalgic.

Alex’s mom opened the door and welcomed me in. She wore the local mom uniform of yoga pants and a zipped-up track jacket, her thick black hair pulled into a high ponytail. “You must be Kara,” she said. “Come on in—Alex is inside and my foolish husband is slaving over the hot stove.”

She led me into the kitchen, where a short man in khakis, a denim shirt, and an apron that read TROPHY HUSBAND was frowning over a cookbook as several pans bubbled on the stove. “Hi, I’m Kara,” I said. “It smells amazing in here.” I meant it, too; the air was full of ginger and garlic and other spices I didn’t recognize.

“Oh, it’s a disaster,” he said, cheerfully. “I’ve been taking classes and reading these cookbooks to try to reconstruct all these old recipes my mom used to make, but she took her secrets to the grave.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, though he hadn’t sounded sad about it.

“I’m just sorry she didn’t teach me how to cook. You can be sure I won’t make the same mistake with Alex. Hi, honey! Come over here and give me a hand.”

I turned around to see that Alex had just come into the kitchen. “You don’t really want my help,” she said. “I wouldn’t want to get in the way of the fun you’re having.” She said it with a completely straight face, so it took me a second to realize she was kidding.

But her dad understood right away and stuck his tongue out at her. She stuck hers out right back. “Stop screwing around and help me,” he said. This was obviously not the first time they’d done this bit.

“What do you need?” She gave me a nod to acknowledge she knew I was there and then went to read the cookbook over her dad’s shoulder. “I thought you were just going to do pho. You can make that in your sleep.”

“I got ambitious,” he said, looking a little embarrassed. “Shaking beef with red rice … it’s been a while since you had company.”

Now it was Alex’s turn to look embarrassed. “I told you, this is not a big deal!” She glanced over at me. “No offense.”

“None taken.” It was all pretty amusing. “Can I help?”

“No!” they both yelled at the same time.

Alex’s mom laughed. “Let me get you something to drink, and then we can sit at the table and watch the show. It’s usually entertaining, if messy. Last time they made shaking beef, I had to renovate the kitchen afterward.”

I wondered whether she was joking. It was a really nice kitchen, with shiny sea-green tile that looked like little bricks lining the walls behind enormous stainless steel appliances. Even if she was serious, though, it didn’t sound like she minded. Though she was wearing the Marbella uniform, she didn’t seem as high-strung as some of the other moms. Mine included.

She handed me a glass of iced tea and we sat at the table and watched Alex and her dad prepare the food. They worked well together, only talking occasionally, trading ingredients and utensils back and forth like people who did this all the time, which they clearly did. I couldn’t even imagine having that kind of a routine with my dad; he was so caught up in work that even my earliest memories were of him on his cell phone. The only time we’d really spent alone together was when he helped me study—he was really good at English and all the nonmath stuff that I wasn’t so into—but that hadn’t happened in a long time.

“Almost there,” Alex said.

Once they were done, they stuck big spoons right in the pots and handed out bowls so we could all serve ourselves. Then we sat at the kitchen table and completely pigged out. I liked how casual it all was, but that they all ate together. In my house we mostly fended for ourselves or ate in front of the television; we only ate at the dining room table when my parents were having people over. Which happened almost never.

“This food tastes even better than it smells,” I said, fighting the urge to talk with my mouth full so I could keep eating.

“He’s a better cook than his mother was,” Mrs. Nguyen said. “And he knows it, too.”

“Don’t be silly.” Mr. Nguyen waved her off, but he looked pleased. “Cooking is just a hobby.”

“A likely story,” Alex said. “I keep waiting for you to tell us you’re ditching work to open a restaurant.”

“It’s a great idea. Your mom can quit her job and take care of the books, and you can quit school to waitress.”

Mrs. Nguyen laughed. “You’re welcome to trade software for soft-shell crabs, but you’d have to carry me out of the office bound and gagged. And don’t even joke about Alex dropping out of school.”

There it was—that Marbella-mom edge to her voice. I wasn’t the only one at this table with high-pressure parents, then.

“Speaking of school, we should probably get to work,” Alex said.

I thanked her parents for dinner and then followed Alex to her room. Just as I’d expected, she had the same enormous bedroom setup that Becca had, though she’d done something completely different with the space. Her bed was in the same place, but instead of a lounge area she had a huge desk that ran the length of the entire back wall and then turned and tracked half of the rest of the room. That was where the computer monitors were. Three of them: one in the center and two at forty-five-degree angles on either side. Also huge.

“Are you an air traffic controller or something?” I asked.

She shook her head. “I guess you could say I’m a programmer.” She sat down in a big fancy-looking desk chair and motioned to a smaller chair next to it for me.

I sat down. “What kind of programming do you do?”

She gave me a little smirk, like I’d caught her doing something she wasn’t supposed to. “Well, maybe I exaggerated a little. I told my parents I needed all this stuff for programming. Can you keep a secret?”

If only she knew. “Sure.”

“I need the screens for poker. I play online. Like, a lot.”

“Isn’t it illegal? I mean, not to sound like a goody-goody or anything …”

She shrugged. “It’s, like, dubious. The playing part isn’t so much illegal, but the money part isn’t something I want people to find out about, if you know what I’m saying.”

“You make money? You must be good.”

“Yeah, I am,” she said, but she didn’t sound arrogant. Just proud. “But that’s also where the programming comes in. I wrote a bunch of tracking programs to help with my game, to run statistics, that sort of thing. It gives me a real advantage over some of the idiots who play online.”

I was impressed. I’d thought she was just this random girl in some classes with me; it turned out she had this totally other secret life. My secrets weren’t nearly as interesting as hers. “Why do you need so many screens?”

“Because I usually play about five or six games at a time. That’s the nice thing about being online—you don’t have to sit at just one table. Your avatar can be in lots of places at once.” She clicked and her screen lit up with the image of a poker table covered in felt; she clicked again and I saw an image of a boy’s face, with short dark hair.

“That’s your avatar?”

“That’s virtual me. I pretend I’m a boy so they’ll take me more seriously. Sad, but poker’s pretty sexist. It’s weirdly not as racist, though—there are a lot of famous players with the same last name as me, so being Alex Nguyen is actually kind of helpful. Not that I use my real name, but some people I play with a lot know it. And they know my uncle, too—he was a professional poker player, a really famous one. Taught me everything I know.”

“When do you have time to do all this?

“At night. I don’t need much sleep.”

I knew that couldn’t be true; I remembered last year, when she used to fall asleep in class every day. “Don’t you need a lot of math for programming? Do you really need my help? It sounds like you could help me more than I could help you—I’m way behind in AP Statistics, too.” I’d loaded up my schedule with math electives, mostly to avoid having to take more science classes.

“Well …” She got that look again, like I’d busted her, and then started talking really fast. “I mean, yeah, calculus isn’t my best subject, but I get by. It’s just … most of my friends are guys, and you and I have been in classes together forever but we’ve never hung out, and I only see you with those Brain Trust kids, and in class you seem smart and funny and they’re smart but not even a little bit funny, and they can’t be a whole lot of fun, and you seem like someone who should maybe be having more fun than you are, and I thought maybe we should be friends.”

She took a deep breath. I stared at her.

“Well, are you going to say something? Did I just totally humiliate myself? We can just study. No problem. I’ve got stats down cold. Took it sophomore year.”

“No, wait,” I said. “You just talk way faster than I can think. You’re right.”

“Right about which part?”

“Right about all of it. I do pretty much only hang out with Julia and those guys, and only at school, because they’re not fun.”

“I’m totally fun. We’re going to start getting you out more.”

I’d never met anyone so direct. It was kind of amazing. “That would be great,” I said. I wanted to tell her that I used to have friends, that it wasn’t always like this, but that wouldn’t change anything.

“Oh, that is so excellent. I have such a good feeling about you, you know? And we’re like twins.” She pointed to our outfits, which were both variations on the hoodie/tank top/jeans/tennis shoes combo.

I raised my eyebrows at her. One minute into our friendship was too early to state the obvious.

“Oh, yeah, except for the Asian thing,” she said.

Or maybe it wasn’t. Even better.

Alex started her fast talking again. “Isn’t it weird, how hard it is to make new girlfriends? It’s like you hang out with the same people forever, and at a certain point that’s all there is. Boys are so much easier. You can just go right up to them and say whatever you want, and either they’ll be friends with you or they won’t. Girls are so much more complicated.”

“Is it really that easy?” I asked. “With boys, I mean?”

“It has been so far. Except for if they get a thing for you. Then it gets complicated. But I bet you know how to deal with that, pretty as you are. God, it’s so great to have someone to talk to about this stuff! We should tell each other everything!” She must have seen the look on my face. “Uh-oh. Is this not a good topic? Are you not into guys? Girls are good too. I mean, I’ve only made out with a couple, just to see if it was my thing, but …”

I couldn’t help it—I started cracking up. She was so different than she came across at school. She wouldn’t be the kind of friend Becca had been, but that was okay. “I’m not into girls. It’s more that my experience with guys is kind of … limited.” I was flattered that she thought I was pretty enough to have dealt with guy issues before, but of course she had no idea what I really looked like. Then again, no one did.

“Well, then, we’ve got some work to do. We’ll have to strategize. Let’s hang out next weekend.”

“Saturday’s the SAT,” I said.

“You didn’t take it yet? I got it out of the way at the end of last year,” she said. “Such a relief.”

I didn’t feel like explaining about the whole panic attack thing. Besides, I’d studied my ass off and read a bunch of meditation books and eaten my mom’s brain food for weeks. I’d be okay this time. “I put it off,” I said. “I really need to do well.” That much was true, anyway. So much for telling each other everything, though.

“Just come over after,” she said. “We can keep it low key. We’ll just hang out.”

“That would be great.” If all went as planned, I’d be in a good mood, and it would be fun to talk about it with a friend. Now that we were friends.

4. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

The morning of the SAT I stumbled out of bed bleary-eyed and in desperate need of coffee. I’d resolved to get a good night’s sleep to prepare, had even tried the stupid meditation techniques from the books I’d read, but nothing worked. I’d stayed up most of the night remembering that disastrous attempt at the PSAT, the one that had kept me from taking the test last year, when I should have. This time had to be different—if I didn’t manage to get through it, I only had one more shot.

Mom was in the kitchen by the time I got downstairs, coffee brewed, a plate of what looked like green eggs at my seat. “Are we channeling Dr. Seuss today?” I asked.

“Scrambled eggs blended with spinach, kale, spirulina, and hemp seeds,” Mom said, coming over and kissing my forehead. “That plus coffee should help you focus. I packed some baggies of almonds and blueberries for you to bring in with you. You’re going to be terrific today.”

“Wow,” I said, picking at the eggs with my fork. They looked beyond disgusting. “Um, thank you?”

“I tasted them first,” Mom said. “They’re not as bad as they look. I added lots of salt and pepper. Give it a shot.”

I took a very, very small bite. They tasted … green. Which was fine. Other than that epic dinner at Alex’s, I’d eaten almost nothing but green food for a week in preparation for today. I was used to it. “Not bad,” I said, though I loaded up my coffee with cream and sugar, just to have something that tasted good. “Where’s Dad?”

“He’s at work already.”

“On a Saturday?” I shouldn’t have bothered asking; lately he’d been working every weekend, and most of the time Mom had too, now that she was working with him. Weekends were irrelevant now that he was starting a new company.

“He’s stressed about the next round of funding,” Mom said.

“Should he be?”

“I don’t think it matters. He’d stress out either way. Just like you.”

And here we’d been doing so well. She was right, though; Dad and I did have a lot in common, and we both had a tendency to stress. But Dad’s stress always seemed tied to work, while I managed to get myself anxious about everything. At first I’d thought it started with the skin, but then I thought about all the things I’d worried about before that—my friendships, school, my parents. Really, I worried about everything, all the time; the only thing that had ever helped me relax was swimming, and that was gone now.

I’d tried to talk to my dad once about how he managed, hoping he’d have a suggestion that would help me, but he’d told me he just tried to convert his stress to energy and put the energy into work, which to me seemed kind of circular. “I did go to a doctor once,” he said. “He put me on some medication, but I had a really bad reaction to it.”

“I don’t remember that,” I said.

“You were really young. And that was a good thing, because it was a very scary time. I was hallucinating and stopped sleeping. It was awful for your mother. She still doesn’t like to think about it.”

That did explain a lot, especially her emphatic “No!” when I’d asked her about beta blockers or Xanax. I knew lots of kids at school were taking them, but she wasn’t having it. The whole brain food thing was her way of trying to make up for it, which I appreciated.

“When do you need to get going?” Mom asked, watching me pour myself another cup of coffee.

“Not for almost an hour,” I said. “Can you pass me the crossword?” Better to keep my brain busy than to think about what was coming, I figured.

“Oh, I don’t think it’s here yet,” she said, not looking at me.

“Mom. They drop the paper off in the middle of the night. You bring it in every day. The one time it wasn’t here when you woke up, you called them to complain. I know you have it, so where is it?” I didn’t mean to sound irritable, but I could hear the edge in my voice.

She sighed. “Can you just skip the crossword for today? You can do it when you get home. You have enough to think about as it is.”

“Which is exactly why I need it.” Why was she being so weird?

My question was answered as soon as she pulled the paper out from under a stack of magazines and handed it over. Marbella was small enough that the newspaper was half the size of a normal paper like the San Francisco Chronicle. And we had so little crime that the front cover was usually devoted to something related to local politics, or high school sports. Or good news.

JULIA JACKSON, NATIONAL MERIT SEMIFINALIST, WINS SCHOLARSHIP! the headline screamed at me.

Oh, great.

I skimmed the article. Julia had won the Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship Society’s first annual prize, a ten-thousand-dollar-per-year scholarship to the school of her choosing. The prize was reserved for students of “exceptional promise,” the article read. “‘It’s a new award, but it’s a tremendous honor,’ said an admissions officer at UC Berkeley, who wished to remain anonymous. ‘It’s certainly the kind of thing we’d take into account when choosing between students.’”

It was like they’d written the article just to mess with my head.

“I think I can see the steam coming out of your ears,” Mom said. “That’s why—”

“—you didn’t want me to have the paper,” I said. “I get it. You were right. You’re right about everything.” I got up from the table and took my plate and cup over to the sink. “Thanks for breakfast. I’ll see you when I get home.”

“Honey, I don’t care about being right,” Mom said. “I won’t be here this afternoon, but I’ll see you when I get home from work. Call and tell us how it went?”

Figures she’d go to work on a Saturday too. Bad enough when it was just Dad. “Yeah, I’ll call. I’m going out tonight anyway.”

“Really? With who?” Mom sounded excited.

“A new friend. No big deal.”

“Well, you can tell me all about that too, when you get home. Don’t stay out too late.”

“I won’t,” I said. When had I ever?

Outside, the sun was shining and the sky was perfectly blue and free of clouds and it was like the day had been sent to mock me. I had a terrible feeling about how things would go; it would have been more appropriate for it to be raining. I got in my car and cracked an energy drink for the ride. It would probably be too much on top of the coffee, but I was too tired to do without it. By the time I got to school I was wired; I hoped that was the primary explanation for the jangling of my nerves.

Ms. Davenport was the SAT proctor, so the test was in her classroom. That was a good sign in more ways than one—all my associations with that room were positive. I’d aced lots of tests there, and just seeing Ms. Davenport at the front of the room was comforting. Maybe my feeling of foreboding was wrong.

Of course, the room was also full of seniors, since it was too early for even the most enterprising juniors to be taking their first shot at the test. But most of the kids in the AP classes I took had already taken it last year, so as I looked around the room, there were only a couple of really familiar faces.

Becca and Isabel.

Both of them were in their workout clothes, not much makeup, Isabel’s long blond hair in a high ponytail. Both of them had big Starbucks cups in front of them and matching energy bars. They must have met up beforehand and come together. I wondered whether they still had the same favorite drinks: skinny vanilla latte for Isabel, and matcha green tea for Becca. Isabel and I used to tease her for that one; it smelled terrible, and though Becca insisted it tasted better than it smelled, we both refused to try.

I still missed them.

I couldn’t let them get me off track, though. I had to concentrate on the good things: the luck of getting to be in this room, with its comforting smell of chalk dust; the fact that my usual class seat was open, so I could pretend this was just another test instead of the thing that was going to decide my whole life; the meditation exercises I’d practiced last night and that I had time to do now. So what if they hadn’t worked before? Today would be different. It had to be.

I closed my eyes and breathed naturally, in and out, focusing on each breath. My pulse slowed; I could see patterns forming on the backs of my eyelids, white dots swirling like kaleidoscopes against a dark-red backdrop, and let them soothe me. Ms. Davenport’s voice came into focus as she read the directions. I opened my eyes to see her passing out the exam packets.

I was going to be fine. I was ready.

Ms. Davenport gave the signal, and we tore open the seals holding our packets together. The first section was math, thank goodness. I started working through the early problems, the easier ones, and managed to get through five questions before I started feeling thumping in my head. Breathe, I thought. Focus. I calmed myself down enough to finish the section, which wasn’t too hard. Just like I’d practiced.

I was relieved to know I could do this.

The second section was critical reading. Two fill-in questions, no problem. The words started to go blurry when I got to some analogies, but I reminded myself to think of them like ratios. I slowed down and concentrated, using the techniques I’d learned from the study guide to narrow my options. All fine.

Until.

The first paragraph took up the entire left-hand column of the page. I started reading it and got halfway through before I realized I’d only taken in maybe every third word. Something about global warming? Rain forests? Endangered species? I started over. I still wasn’t getting it.

I held my thumb to the left side of my chin to check my pulse. It was speeding up.

My stomach clenched.

Beads of sweat formed on my forehead, even though I was really, really cold.

I looked back down at the test booklet and started reading the passage again. This time it was like I couldn’t even see the words.

Come on, I thought.

My lungs were getting smaller, making it almost impossible to squeeze breaths in and out of them.

I had to get out of here.

I looked up to see Ms. Davenport watching me, brows lowered. She tilted her head as if asking me a question. I stood up to tell her I had to go to the bathroom, but I’d waited too long. The patterns from the backs of my eyes were back, the white dots and the maroon behind them, except this time my eyes weren’t closed.

Then everything went dark.

5. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

I opened my eyes to white. White with little black dots that it took me a minute to recognize as ceiling tiles. I was lying on a bed—no, a cot. Brightly colored posters with warning signs for eating disorders and sexual abuse covered the walls.

I was in the nurse’s office.

I’d been here a couple of times, mostly to grab a tampon when I’d run out. The nurse was nice about making them easy to find, so we didn’t have to bug her when we needed them. But I’d never actually gotten far enough into the room to explore the cot situation. It was extremely uncomfortable, with springs that poked into my back, and I wondered if that was on purpose, to keep kids from using the nurse’s office to take naps.

I sat up and the springs creaked, loud enough to shock me, and apparently loud enough that they were audible outside the room because the nurse came rushing in.

“Kara, so glad you’re up,” she said. “You gave us a little scare but you’re going to be fine. Good thing I was here!”

“What happened?” I asked. I remembered standing up to leave the room, but that was about it.

“You fainted. Just for a minute, but you had us worried—you were very agitated when you woke up, so we brought you here for a little rest. We left a message at your house but we don’t seem to have your parents’ cell phone numbers.”

“I think I had a panic attack,” I said. It was the first time I’d said it out loud; even when I’d talked to my parents about the things that had happened in the past, I never used those words. “My parents are at work—I don’t want to call them.”

“You may be right about the panic attack,” the nurse said. “That’s something worth talking to your doctor about. Are you sure I can’t call your mom for you?”

I shook my head. No need to bring them into it. I wanted to manage my own disappointment in myself before I took on theirs. “I just want to go. My car’s in the lot.”

“I’m afraid I can’t let you do that quite yet,” she said. “I don’t want you driving until I’m sure you’re okay, and your teacher wanted to come by and chat after the exam. Should be done in just a couple of minutes, and in the meantime I’ve got some juice and crackers for you. Just to get that blood sugar up.”

“But the test just started,” I said. “I don’t want to wait that long.”

“Oh, you’ve been asleep for a couple of hours. You must have been wiped out. Here, have a snack and Ms. Davenport will be by in just a few minutes. Okay if I go man the desk outside? There are bound to be some post-exam meltdowns.”

I nodded, and she handed me the plate of crackers and a little flowered paper cup of juice. The mix of carbs and sugar reactivated all the caffeine I’d had, and I started to feel less sleepy and more alert. Which brought the memory of blacking out in the middle of the classroom right to the surface. I started to shake as I realized that not only had I not managed to actually take the stupid SAT, but I’d fainted in front of Becca and Isabel. I couldn’t remember ever feeling so humiliated.

There was a light tapping on the open door of the nurse’s office and I looked up to see Ms. Davenport. “I came as soon as I could,” she said. “Are you okay?”

I couldn’t help it—as soon as I heard her voice, I started crying. Ugly crying, too, not just a few tears; I sobbed until I was almost hiccuping, burying my head in my arms. The cot creaked as Ms. Davenport sat down next to me and patted my back, waiting for me to calm down. Once I’d stopped crying long enough to try to breathe, she handed me a Kleenex. “Do you want to talk about it?”

I opened my mouth to say no, but instead all these words came pouring out, along with more tears. “I can’t believe this is happening. I worked so hard and now I’m so embarrassed and I’m never going to get into college and I’m never going to get out of here and everyone saw and now they’re all going to talk about me and my parents are going to be so disappointed and …” I started sobbing again, enough that I couldn’t talk.

I couldn’t believe I’d said all that to Ms. Davenport, but it made sense that if I said it to anyone, it would be her. She’d become more than just a teacher to me; we’d worked really closely together during geometry, and after a while I’d started telling her about all the pressure I was feeling, and she gave me advice on how to keep it from getting to me, reminding me that everything I was doing was for me, not for my parents, or for the competition. It didn’t always work, but I did try to keep my eyes on the future. My future. I was thrilled to get her for calculus, and sometimes I’d stay after class or even after school and talk to her about colleges. She gave me a list of some of the East Coast schools with good math programs and said she’d write a recommendation for me for wherever I wanted to go. All the students loved her, so it made me feel special that she’d taken a particular interest in me.

I hated that she’d seen me like this, but I knew she wouldn’t judge.

“All right, Kara, you’re all about logic, so let’s break this down together,” she said. “I know you, so I have no doubt that you worked hard. And I understand you’re embarrassed, but no one made fun of you; a couple of the girls asked if you were okay, but everyone else just went back to the test, because that’s what people do—they worry about themselves. No one’s paying as much attention to you as you think, and that’s okay.”

I wanted to believe her, but I also knew that the worst of it wouldn’t happen in front of her. That would come later. I wondered whether Becca and Isabel were the girls who’d asked about me.

“You’re also going to get into college, and you’ll get out of Marbella too, if that’s what you want. You’re right that the SATs matter to a lot of places, so that’s something you’ll have to figure out some other time, but there are also schools that don’t require them, and some of those schools are fantastic. You have options. And I met your parents at parent-teacher conference night back when you were a freshman, and they were very loving and supportive.”

I did my meditation breathing while I listened to her. I liked that she knew me well enough to know that logic was the best way through this—if she’d just been all sympathetic and sweet, I’d have never stopped crying. “Okay,” I said, and tried to blow my nose as discreetly as possible. I hoped my makeup hadn’t smeared all over the place. “That helps.”

“Now, do you want to tell me what happened in there?”

“Panic attack,” I said from behind the Kleenex. It was getting easier to say it out loud.

“I’ve given you lots of tests and never even seen you break a sweat,” she said. “What’s different about the SAT? Or is it just the SAT?”

“It’s not just the SAT, but it’s mostly that. I just get so stressed out about it, because my scores need to be perfect if I want to go to Harvard, since there’s, like, nothing else interesting about me. I used to swim, but I don’t anymore, so now all my extracurriculars are just filler, and all the schools will know it. I have to ace this test. But if I keep losing it every time I try to take it, I’ll never get in.”

“If you’ve convinced yourself that you need perfect scores, then it’s no wonder you’re panicking every time you think about this exam. Perfection is an unrealistic aspiration.”

“That’s what my mom says. I should ‘just do my best.’” I made air quotes. “But we both know that’s not always good enough. She just won’t say it. She and my dad were both great students, killed it at Stanford, killed it in grad school. She can pretend that she doesn’t want me to be perfect, but she doesn’t mean it.”

“Maybe she does,” Ms. Davenport said. “Maybe you should take what she says at face value. Do what you can. Take the pressure off. All this pushing for perfection is damaging, you know. You’ve heard about what’s happening in Palo Alto.”

Of course I had. Everyone had. The papers were calling them suicide clusters. Kids who were scared of not getting into the right colleges didn’t see any other futures for themselves. I bet a lot of them felt like me. I don’t know what kept me from reaching that level of despair, but I felt lucky that I’d been able to avoid those kinds of thoughts.

“That’s not happening in Marbella,” I said.

“It could. Same circumstances—public high school in an affluent town, parents putting pressure on their kids to go to elite schools. I don’t want to have to worry about you.”

“You don’t have to,” I said. “Besides, I know I put a lot of the pressure on myself.” Which was true.

“Well, you need to find a way to let yourself off the hook, then.”

“I guess.” It was kind of a bummer to hear Ms. Davenport talking like a typical grown-up, which wasn’t usually her thing. She and Mom could say whatever they wanted about me not needing to be perfect, but I knew who I was competing with. My guidance counselor had basically admitted that if I didn’t make valedictorian and get near-perfect scores on the SATs, all the good East Coast schools would be out of reach. And all the best math departments were at research institutions, as Ms. Davenport well knew, and they all required the SATs. There was no getting around it.

“I hear the skepticism,” Ms. Davenport said. “Just tell me you’ll think about it. And that you’ll come talk to me if the pressure’s getting to be too much. I’ll do whatever I can to help.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I will.”

“Now, can I call your mom to come get you?”

“She’s at work. I’m fine—I’ve got my car.”

“You sure you’re okay to drive?”

“I feel a lot better now,” I said. But it wasn’t true.

Alex texted as I was walking out to the parking lot: All done? How did it go? When are you coming over?

Good to know word hadn’t made it to her yet. Maybe Ms. Davenport was right; maybe people hadn’t been paying that much attention. I hated having to admit what had happened, but it was nice to have a friend checking up on me.

Disaster, I wrote. Tell you about it tonight. When do you want me?

Sounds like you need cheering up, she wrote. Let’s go for ice cream instead. Meet me downtown at seven.

I was about to suggest frozen yogurt, but then I figured, why bother? No need to keep up with the crazy health food diet if it wasn’t going to help anyway. Ice cream sounded awesome.

Now I just had to keep myself busy for the rest of the afternoon. If I kept thinking about the morning’s nightmare, I’d never stop crying. It was times like these when I really missed swimming. Being in the water, feeling the cool of it on my skin, concentrating on my arms and my legs and making them work together and nothing else—it was the perfect way to get out of my own head. My favorite stroke was freestyle, which had always come naturally to me; Becca was all about the butterfly, which made sense, given that she was more muscular than I was. She had so much power in her arms and shoulders, whereas I’d hit my growth spurt early and could use my long arms and legs to move through the water smoothly.

Swimming had been my only form of exercise. When I stopped, I missed the endorphins. I started getting depressed, though initially I’d assumed it was because high school was so hard and because Becca and Isabel and I were already growing apart.

Mom had seen what was going on. “Sweetie, you’re going to need to get some exercise,” she said one day, as I picked at my cereal, wishing I could just get back into bed instead of going to school.

“What, you think I’m gaining weight or something? Don’t I worry about my appearance enough as it is?” I was really not in the best mood.

“Not at all,” she said, unruffled. It took a lot to ruffle her. “You just seem unhappy, and I think you’d be surprised how much better you’d feel if you got in a workout.”

“Well, that’s impossible,” I snapped. “I can’t swim anymore, and I’m not about to go somewhere without the stupid makeup, and the stupid makeup is not sweat-friendly.”

Mom paused, trying to decide which aspect of what I’d said to take on. We hadn’t talked about my unwillingness to let anyone know about my skin problem, and back then she and Dad were just starting to work out their issues post-Tahoe, which I knew she hadn’t told anyone about either. It’s not like I’d have listened if she’d told me it was time to start sharing. “I understand,” she said finally, and I thought that was the end of it.

I came home from school that day to find a brand-new treadmill in the guest bedroom. I had no idea how she’d made it happen that fast, but I recognized the gesture immediately. She wasn’t even home from work yet; she must have come home to let the delivery people in and then gone back. My eyes teared up with embarrassment—I’d been such a jerk that morning, and this was how she’d responded. I changed into shorts, a T-shirt, and tennis shoes right away.

Ever since then, I’d come to enjoy running on the treadmill, at least as much as anyone liked running on a treadmill, and I used it to get away from being in my own head all the time. I cranked the stereo when no one was home (or blasted music through my headphones when they were), and for an hour I was free.

A long run would be the perfect way to get the morning out of my system. I put on the happiest music I could find and ran until I could barely feel my legs and my clothes were soaked with sweat. The feeling was exhilarating, and by the time I’d gotten out of a blissfully cold shower, I was ready to put the day behind me.

6. (#u419ea94d-00de-5bfc-b5a5-9685f48735e5)

Alex was waiting for me outside the ice-cream place when I got there, and I could tell she desperately wanted to ask me what happened; she was practically twitching with curiosity. But to her credit she waited until we’d both gotten big waffle cones filled with ice cream and topped with sprinkles—sea-salt caramel for her; mint chip for me—and walked over to the park nearby. Fall in Silicon Valley was almost more like summer—it was in the low eighties, even though it was October—and the store had been filled with people with the same plan as ours. Thankfully, though, the park itself was quiet.

We sat on adjoining swings and started on our cones. I liked to lick all the sprinkles off, giving the ice cream a little time to melt, but Alex just stuck her face right in there and took a big bite. “Oh my god, that hurts my teeth SO BAD!” she yelled, once she’d swallowed.

“At least you didn’t get brain freeze,” I said, but she was already squeezing her eyes shut. “Did I speak too soon?”

“If we’re going to be friends, I mean real friends, you are going to have to teach me patience.”

“You think I have patience?”

She pointed to my cone. “You’re even patient with your ice cream. Not to mention that you haven’t started talking yet and I am dying over here.”

“I thought that was just the brain freeze,” I said. “Maybe I can teach you patience by waiting a little longer.”

She gave me a side-eye glare and I laughed.

“Come on,” she said. “It couldn’t have been that hard. Not for a member of”—she deepened her voice—“the Brain Trust.”

“Hard wasn’t the problem,” I said. “The face-plant. That was the problem.”

“The what now?”

“I totally blacked out. Fainted. In front of everyone.”

“You’re kidding,” she said, and took another giant bite of ice cream, wincing as it hit her teeth. “Tell me everything.”

And the funny thing was, I wanted to. Had it really been over a year since someone had been really, truly interested in what was happening to me? At lunch we talked about school, about our futures, but we almost never talked about ourselves. How we felt about things. That was what I’d had with Becca and Isabel, until I’d stopped wanting to tell them what was really going on with me. Or they’d stopped wanting to listen. Either way.

“Well, this wasn’t my first panic attack,” I told Alex. I didn’t want to get into the specifics of the first one, but I told her there were some things that stressed me out and I’d started having these attacks, and then I told her about the PSAT.

“That sounds scary,” she said.

“Totally,” I agreed. “The thing is, there’s only one more SAT before college apps are due, and I just have to nail it. I don’t know what I’m going to do.” I licked my ice cream, which was about two seconds away from dripping all over me. The perils of patience.

Alex had powered through hers and was now chewing on the last bits of cone. “So is it more about fear or focus?”

“Does it matter? I’m kind of screwed either way.”

“Humor me,” she said. “I might have some ideas.”

I had to think about it. “I don’t know. I mean, I think it’s more about fear, but this time I got through that first bit, and then it turned into focus. It was like I forgot how to read—I finished the first section, math, but then when I got to reading comp it was like I couldn’t see, and then I couldn’t breathe, and then I was back to fear.”

Alex kicked at some of the gravel under the swing. “So, I don’t know if this is something you’d be into, but I kind of had some similar problems last year. It started out more as a focus thing—I was staying up all night playing poker, and I kept falling asleep in class. But then I was having trouble playing because my head just wasn’t in it, and it started affecting school. And when it was clear the focus was gone, the fear kicked in—I didn’t know if I’d ever get the focus back, and I was scared it was going to ruin everything. It was like this horrible cycle.”

“But you got over it? And don’t tell me it was like meditation or yoga—I’ve tried all that already. Total fail.”

“No, I’m not into any of that crap. I’m more into better living through chemistry.”

“I tried that,” I said. “Well, I didn’t actually try anything. But I asked my mom about getting some sort of medication. Adderall or Xanax or whatever.”

“That’s rookie stuff,” she said. “I found something better. It’s this new thing—it just got FDA approval, so not that many people know about it yet, but it’s all over Canada and Europe.”

I noticed she hadn’t said the word “drug.” “What does it do?”

“Everything! It’s kind of a miracle. It keeps me focused and steady, but not hyper or jittery, and I know people who’ve taken it for anxiety who said it makes them totally calm. It’s even helping my poker game—it’s like I can keep more information in my head all at once without getting distracted.”

“What’s it called?”

“Novalert. And it’s incredible.”