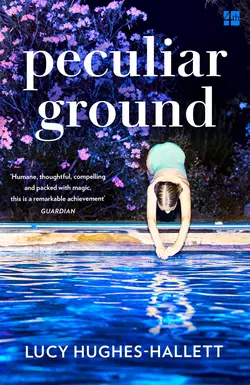

Peculiar Ground

Lucy Hughes-Hallett

‘One of the best novels of the year so far’ The TimesA SPECTATOR BOOK OF THE YEAR‘Unlike anything I’ve read. Haunting and huge, and funny and sensuous. It’s wonderful’ Tessa Hadley‘I just enjoyed it so very much’ Philip PullmanIt is the 17th century and a wall is being built around a great house. Wychwood is an enclosed world, its ornamental lakes and majestic avenues planned by Mr Norris, landscape-maker. A world where everyone has something to hide after decades of civil war, where dissidents shelter in the forest, lovers linger in secret gardens, and migrants, fleeing the plague, are turned away from the gate.Three centuries later, another wall goes up overnight, dividing Berlin, while at Wychwood, over one hot, languorous weekend, erotic entanglements are shadowed by news of historic change. A little girl, Nell, observes all.Nell grows up and Wychwood is invaded. There is a pop festival by the lake, a TV crew in the dining room and a Great Storm brewing. As the Berlin wall comes down, a fatwa signals a different ideological faultline and a refugee seeks safety in Wychwood.From the multi-award-winning author of The Pike comes a breathtakingly ambitious, beautiful and timely novel about game keepers and witches, agitators and aristocrats, about young love and the pathos of aging, and about how those who wall others out risk finding themselves walled in.

(#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

Copyright (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright 2017 © Lucy Hughes-Hallett

Lucy Hughes-Hallett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover images © plainpicture/Melanie Haberkorn

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Map drawn by John Gilkes

‘Don’t Fence Me In’ (from Hollywood Canteen), words and music by Cole Porter © 1944 (Renewed) WB MUSIC CORPS. All rights reserved. Used by Permission of ALFRED MUSIC.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008126544

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008126537

Version: 2018-01-16

Dedication (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

For my brothers,

James and Thomas,

with love

Epigraph (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

We are a garden walled around,

Chosen and made peculiar ground;

A little spot enclosed by grace

Out of the world’s wide wilderness.

ISAAC WATTS

Contents

Cover (#u03789958-48c1-58eb-bdbe-e0bbf3a795e5)

Title Page (#ua417a75c-75b9-5d22-8250-e43498fd976d)

Copyright (#u62558696-1ab3-5c79-951b-b469eb571f7c)

Dedication (#ucc868b76-4f42-5b6c-85d7-ca0597d57ef0)

Epigraph (#u195c2b43-cdfb-55f1-8251-3f92cef91a65)

Dramatis Personae (#ua8c9b23f-0475-50b5-9dc6-5ad4b879b357)

Map (#u6e5c9ccd-1dca-5b95-840e-b02127e74ae7)

1663 (#u3f9629f2-1f32-5fb1-b85e-da8ca9344ecb)

1961 (#u8d6e2dcd-ab6f-5e23-91ef-b8e0ba47d57a)

Friday (#u557e10b0-bd2f-50d3-bfb2-8a51da28d36a)

Saturday (#ucf4856e2-a080-52b8-9651-12842748bd65)

Sunday (#litres_trial_promo)

1973 (#litres_trial_promo)

June (#litres_trial_promo)

July (#litres_trial_promo)

August (#litres_trial_promo)

1989 (#litres_trial_promo)

September (#litres_trial_promo)

October (#litres_trial_promo)

November (#litres_trial_promo)

1665 (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Dramatis Personae (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

1663–1665

John Norris – landscape-maker

Arthur Fortescue, the Earl of Woldingham

The Countess of Woldingham, his wife

Their children – Charles Fortescue, Arthur Fortescue and a little girl

Sir Humphrey de Boinville, brother to Lady Woldingham

Lady Harriet Rivers, Lord Woldingham’s sister

Cecily Rivers, her daughter

Edward

Pastor Rivers – brother to Lady Harriet’s late husband

Another pastor

Robert Rose – architect and comptroller

Meg Leafield

George Goodyear – head forester

Armstrong – ranger

Green – head gardener

Slatter – farm overseer

Underhill – major-domo

Lane – steward

Richardson – apothecary

Lupin, a pug-dog

1961–1989

Living at Wood Manor

Hugo Lane – land agent

Chloe Lane – his wife

Nell – their daughter, aged eight in 1961

Dickie – their son, aged five in 1961

Heather – nanny

Mrs Ferry – cook

Wully, a yellow Labrador, and later his great-nephew, another Wully

Living at Wychwood

Christopher Rossiter – proprietor

Lil Rossiter – his wife

Fergus – their son

Flossie/Flora – Christopher’s niece, aged eighteen in 1961

Underhill – butler

Mrs Duggary – cook

Lupin, a pug-dog, and later another Lupin, also a pug-dog

Grampus, a black Labrador

Visitors

Antony Briggs – art-dealer

Nicholas Fletcher – journalist

Benjie Rose – restaurateur, interior designer, entrepreneur

Helen Rose – his wife, art-historian

Guy – Benjie’s nephew, aged thirteen in 1961

On the estate

John Armstrong – head keeper

Jack Armstrong – his son, aged seventeen in 1961

Doris, Dorabella, Dorian and Dorothy – all spaniels

Green – head gardener

Young Green, his son

Brian Goodyear – head forester

Rob Goodyear, his son

Slatter – farm manager

Meg Slatter – his wife

Bill Slatter – their son

Holly Slatter – Bill’s daughter

Hutchinson – estate clerk

In the village

Mark Brown – cabinet-maker

Nell’s fellow students at Oxford in 1973

Francesca, Spiv Jenkins, Manny, Jamie McAteer, Selim Malik

In London

Roger Bates – wartime military policeman, subsequently in Special Branch

(#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

1663 (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

It has been a grave disappointment to me to discover that his Lordship has no interest – really none whatsoever – in dendrology. I arrived here simultaneously with a pair of peafowl and a bucket full of goldfish. It is galling that my employer takes more pleasure in the creatures than he does in my designs for his grounds.

He is impatient. Perhaps it is only human to be so. He wishes to beautify his domain but he frets at slowness. When we talked in London, and I was able to fill his mind’s eye with majestic vistas, then he was satisfied. But when he sees the saplings reaching barely higher than the crown of his hat he laughs at me. ‘Avenues, Mr Norris?’ he said yesterday evening. ‘These are sticks set for a bending race.’

The idea having once occurred to him, he set himself to realising it. This morning he and another gentleman took horse and, like two shuttles drawing invisible thread, wove themselves at great speed back and forth through the lines of young beeches that now traverse the park from side to side. There was much laughter and shouting, especially as they passed the ladies assembled at the point where the avenues (I persist in so naming them) intersect, the trees forming a great cross which will be visible only to birds and to angels. I confess the gentlemen were very skilful, keeping pace like dancers until, nearing the point where the trees arrive at the perimeter, where the wall will shortly rise, they spurred on into a desperate gallop in the attempt to outdistance each other, and so raced on into a field full of turnips, to the great distress of Mr Slatter.

They are my Lord’s trees, his fields and his turnips. Like Slatter and his muddy-handed cohort, I must acknowledge the licence his proprietorship gives him, but it grieved me inordinately to find that eleven of my charges, my eight hundred carefully matched young beeches, have been damaged, five of them having the lead shoot snapped off. I attended him after dinner and informed him of the need for replacements. ‘Mr Norris, Mr Norris,’ he said. ‘It is hard for you to serve such a careless oaf, is it not?’

He authorised me to send for substitutes. He is not an oaf. Though it pained me, I took delight in the performance of this morning. He incorporated my avenue, vegetable and ponderous, into a spectacle of darting grace. But it is true that I find him careless. To him a tree is a thing, which can be replaced by another thing like it. Is it lunacy in me to feel that this is not so?

We who trade in landskips see the world not as it is but as it will be. When I walk in the park, which is not yet a park but an expanse of ground hitherto not enhanced but degraded by my work in it, I take little note of the ugly wounds where the earth has been heaved about to make banks and declivities to match those in my plan. I see only that the outline has been soundly drawn for the great picture I have designed. It is for Time to fill it with colour and to add bulk to those spare lines – Time aided by Light and Weather. I suppose I should say as well, aided by God’s will, but it seems to me that to speak of the Almighty in these days is to invoke misfortune. It is more certain and less contentious to note that Water also is essential.

*

Of the people who manage this estate my most useful ally has been Mr Armstrong, chief among my Lord’s rangers. For him, I believe, the return of the family is welcome. He is an elderly man, with the hooked nose and abundant beard of a patriarch. He remembers this house when the present owner’s father had it, and he rejoices at the thought that all might now be as it was before the first King Charles was brought down. I think he has not reflected sufficiently on how this country has changed in his lifetime, not only superficially, in that different regiments have succeeded each other, but fundamentally. It is true that there is once more a Charles Stuart enthroned in Whitehall, but the people who saw his father killed, and who lived for a score of years under the rule of his executioners, cannot forget how flimsy a king’s authority has proved.

Armstrong and Lord Woldingham talk much of pheasants – showy birds that were abundant here before the changes. Armstrong would like to see them strut again about the park. He has sent to Norfolk for a pair, and will breed from them. For him, I think, I am as the scenery painter is to the playwright. He is careful of me because I will make the stage on which his silly feathered actors can preen.

For Mr Goodyear, though, I am suspect. He is the curator of all of Wychwood’s mighty stock of timber. The trees are his precious charges. Some of them are of very great antiquity. He talks to them as familiars, and slaps their trunks affectionately when he and I stand conversing by them. I do not consider him foolish or superstitious: I do not expect to meet a dryad on my rambles, but I too love trees more than I care for most men. Goodyear is loyal to his employer, but it seems to me he thinks of those trees as belonging not to Lord Woldingham but in part to himself, his care for them having earned him a father’s rights, and in part to God. (I do not know to which sect he is devoted, but his conversation is well-larded with allusions to the deity.) He is ruddy-faced and hale and has a kind of bustling energy that is felt even when he is still. I will not enquire of him, as I do not enquire of any man, which party he favoured in the late upheavals, but I think him to have been a parliamentarian.

Today I walked with him down the old road that leads through the forest to the spring called the Cider Well. The road is still in use, but very boggy. ‘His Lordship would like to close it,’ said Goodyear. ‘I suppose he may do so if he wishes,’ I said. Goodyear made no reply. I have heard him allude to me as ‘that long lad’. I think he has judged me too young to be competent, and too pompous to be companionable.

Passing the spring, we dropped down into a valley, its mossy sides bright with primroses. The rabbits had already been at work on the new grass beneath our feet, so that the track was pleasant to walk upon.

A woman I had seen before – old but quick of step – was walking ahead of us. Goodyear called to her. She looked back over her shoulder, nodded to him, and then darted aside, taking one of the narrow paths that slant upwards, and vanished among the trees.

‘You know that person?’ I asked.

‘I’d be a poor forester if there were any soul in these woods without my knowledge.’

I ignored his pettish tone. ‘Does she live out here, then?’

‘She does.’

‘I encountered her in the park on Sunday. She made as though she wished to speak to me, but thought better of it.’

‘It’s best so. Don’t let her bother you, sir.’

I let the matter rest and began to talk to him of the plans I have discussed with Mr Rose, the architect. Rose is one of the many Englishmen of our age who, following their prince into exile, have grown to maturity among foreigners. There are constraints between such men and those of us who stayed at home and picked our way through the obstacles our times have thrown up. Rose and I deal warily with each other, but our work goes on harmoniously. In Holland Mr Rose interested himself in the Dutchmen’s ceaseless labours to preserve their country from the ocean to which it rightfully belongs. My Lord calls him his Wizard of Water.

We would build a dam where this pretty valley debouches into a morass, and thereafter a series of further dams. Thus contained and rendered docile, the errant stream will broaden into a chain of lakes. The three upper lakes will lie without the wall, as it were lost in the woods. The last watery expanse will be within the park and visible from the house, a glass to cast back the sun’s light and duplicate the images of the trees clumped about it.

It was as though Goodyear could see at once the prospect I sketched with my words, and soon we were in pleasant conversation. Willows, judiciously positioned, he rightly said, would bind the dams with their roots, and red alders might give shade. The ‘tremble-tree’, he suggested (I understood him to mean the aspen, a species of which I too am fond), ranged along the watery margins, would give a lightness to the picture, and his tremendous oaks, looming on the heights above, will take off the brashness of novelty, so that my lakes will glitter with dignity, like gaudy new-cut stones in antique settings.

How gratifying it would be to me, if I could enjoy such an exchange of ideas with his Lordship!

*

I could wish nutriment were not necessary to the human constitution, but alas, whatever else we be (and my mind swerves, like a wise horse away from a bog-hole, to avoid any thought that smacks of theology), we are indisputably animals, and animals must eat. My situation here is agreeable enough when I am in my chamber. In the drawing room – where Lord Woldingham expects me to appear from time to time – I am less easy. In the great hall where we dine I am wretched.

It is not the food that discommodes me, nor, to be just to the company, the mannerliness with which I am received. I am my own enemy. My self, of which I am pleasantly forgetful at most times, becomes an obstacle to my happiness. I do not know how to present it, or how to efface it. See how I name it ‘it’, as though my self were not myself. My Lord and his friends talk to me amiably enough. But the contrast between the laborious politeness with which they treat me, and the quickness of their wit in bantering with each other is painfully evident.

As I write this, I feel myself to be quite a master of language, so why is it that, in conversation, words fall from my lips as ponderously as dung from a cow’s posterior? I will be the happier when the guests depart, and so, I fancy, may they be. Although the old portion of the house has not yet been invaded by the joiners and masons, the shouting emanating all day long from the wing under construction is an annoyance. And now that the work on the wall has begun, the park is encumbered with wagons hauling stone to every point on its periphery. The quarrymen set to at first light. We wake to the crack of stone falling away from the little cliff, and our days’ employment has as its accompaniment the clangour of iron pick on rock.

One congenial companion I have found. She is a young lady, not staying in the house, but frequently invited to enjoy whatever entertainment is in hand. She came to me boldly outdoors today.

I had been conferring with Mr Green, who is the chief executor of my wishes for the garden. He is, I consider, as worthy of the name of artist as any of the carvers and limners at work on the house – but because he is tongue-tied, those precious gentlemen are apt to treat him as a mere digger and delver. His own men show him the utmost respect.

Those goldfish that so put me out of countenance on my arrival have proved the seeds from which a delightful scheme has sprouted. The stony paving of the terrace is to be bisected by a canal, within whose inky water the darting slivers of pearl and orange and carnation will show as brilliant as the striped petals, set off by a lustrous black background, in the flower-paintings my Lord has brought home with him from Holland.

‘I hear, Mr Norris, you are rationalising Wychwood’s enchanted spring,’ said the lady.

‘You hear correctly, madam. Some small portion of its waters will trickle beneath the very ground on which you now stand. More will feed a fountain in the valley there, if Mr Rose and I can manage it.’

‘But have you appeased the genius loci, Mr Norris? You cannot afford to make enemies in fairyland.’

I was taken aback. I could not but wonder whether she teased. Were she any other young lady I would have been sure of it. But she is as simple in her manner as she is in her dress. Her name is Cecily Rivers.

*

‘I am glad you and my cousin are friends,’ Lord Woldingham said to me this morning as I spread out my plans for him. He is my elder by a decade, and inclined to mock me as though I were a callow boy. We were in the fantastically decorated chamber he calls his office. Looking-glasses, artfully placed, reflect each other there. When I raised my eyes I could not but see the image of the two of us, framed by their gilded fronds and curlicues, repeated to a wearisome infinitude. I, Norris the landskip-maker, in a dun-coloured coat. He, who will flutter in the scene I make for him, in velvet as subtly painted as a butterfly’s wing seen under a magnifying glass.

I do not much like to contemplate my own appearance. To see it multiplied put me out of humour. My Lord’s remark was trying, too. Often when it comes to time for inspecting the plans he finds some conversational diversion. I did not know whom he meant.

‘Your cousin, sir?’

‘My cousin, sir. You can scarcely pretend not to know her. Pacing the lawn with her half the afternoon. I have my eye on you, Norris.’

He made me uneasy. He loves to throw a man off his stride. In the tennis court, which abuts the stables, I have seen the way he will tattle on – this painter is new come to court and he must have him paint a portrait of his spaniel; this philosopher has a curious theory about the magnetism of planetary bodies – until his opponent lets his racket droop and then, oh then, my Lord is suddenly all swiftness and attention and shouting out ‘Tenez garde’ while his ball whizzes from wall to wall like a furious hornet and his competitor scampers stupidly after it.

I had no reason to fumble my words but yet I did so. ‘Mistress Rivers. Your cousin. I did not know of the relationship.’

‘Why no. Why would you, unless she chose to speak of it?’

‘She lives hereby?’

‘Hereby. For most of her life she lived here.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes. In this house. Cecily’s mother was not of the King’s party. She stayed and prospered under the Commonwealth while her brother, my father, wandered in exile.’

‘And now . . .’

‘And now the world has righted itself, and I am returned the heir, and my aunt is mad, and her husband is dead, and my cousin Cecily is delightful and though I do not think she can ever quite be friends with me, her usurper, she has made a playmate of you.’

‘Your aunt is . . .’

‘The quickness your mind shows when you are designing hanging gardens to rival Babylon’s, Mr Norris, is not matched by its functioning when applied to ordinary gossip. Yes. My aunt. Is mad. And lives at Wood Manor. Hereby, as you say. And Cecily, her sweet, sober daughter, comes back to the house where she grew up, in order to taste a little pleasure, and to divert her thoughts from the sadness of her mother’s plight.’

I must have looked aghast.

‘Oh, my dear Aunt Harriet is not wild-mad, not frenzied, not the kind of gibbering lunatic from whom a dutiful daughter needs protection. My aunt smiles, and babbles of green fields and is as grateful for a cup of chocolate as one of the papists, of whom she used so strictly to disapprove, might be for a dousing of holy water. I am her dear nevvie. She dotes on me. She forgets that I am her dispossessor.’

It is true that yesterday afternoon Miss Cecily and I walked and talked a considerable while on the lawns before the house. Had I known my Lord was watching us I might not have felt so much at ease.

*

It is Lord Woldingham’s fancy to enclose his park in a great ring of stone. Other potentates are content to impose their will on nature only in the immediate purlieus of their palaces. They make gardens where they may saunter, enjoying the air without fouling their shoes. But once one steps outside the garden fence one is, on most of England’s great estates, in territory where travellers may pass and animals are harassed by huntsmen, certainly, and slain for meat, but where they are free to range where they will.

Not so here at Wychwood. My task is to create an Eden encompassing the house, so that the garden will be only the innermost chamber of an enclosure so spacious that, for one living within it, the outside world, with its shocks and annoyances, will be but a memory. Other great gentlemen may have their flocks of sheep, their herds of deer, but, should they wish to control those creatures’ movements, a thorny hedge or palisade of wattle suffices. Lord Woldingham’s creatures will live confined within an impassable barricade. As for human visitors, they will come and go only through the four gates, over which the lodge-keepers will keep vigil.

Mr Rose took me today to view the first stretch of wall to have been constructed. He is justly proud of it. It rises higher than deer can leap, and is all made of new-quarried stone. When completed, it will extend for upward of five miles.

I said, ‘I wonder, are we making a second Paradise here, or a prison?’

‘Or a fortress,’ said Mr Rose. ‘Our King has had more cause than most monarchs to fear assassins. Lord Woldingham is courageous, but you will see how carefully he looks about him when he enters a room.’

‘His safety could be better preserved in a less extensive domain,’ I said.

‘He craves extension. He has spent years dangling around households in which he was a barely tolerated guest. There were times when he, with his great title and his claim on all these lands, had no door he could close against the unkindly curious, nor even a chair of his own to doze upon. He has been out, as a vagabond is out. Now, it seems, he chooses to be walled in.’

The wall is a prodigy. It will be monstrously expensive, but I am gratified to see what a handsome border it makes for the pastoral I am conjuring up.

*

This has been a happy day. It is never easy to foresee what will engage Lord Woldingham’s interest. I was as agreeably surprised by his sudden predilection for hydraulics as I had been saddened by his indifference to arboriculture. Having discovered it, I confess to having fostered his watery passion somewhat deviously, by playing upon his propensity for turning all endeavour into competitive games.

We were talking of the as-yet-imaginary lakes. I mentioned that the fall of the land just within the girdle of the projected wall was steep and long enough to allow the shaping of a fine cascade. At once he gave his crosspatch of a pug-dog a shove and dragged his chair up to the table. I swear he has never hitherto looked so carefully at my plans.

‘What are these pencilled undulations?’ he asked. I explained to him the significance of the contour lines.

‘So where they lie close together – that is where the ground is most sharply inclined?’ He was all enthusiasm. ‘So here it is a veritable cliff. Come, Norris. This you must show me.’

Half an hour later our horses were snorting and shuffling at the edge of the quagmire where the stream, having saturated the earthen escarpment in descending it, soaks into the low ground. My Lord and I, less careful of our boots than the dainty beasts were of their silken-tasselled fetlocks, were hopping from tussock to tussock. Goodyear and two of his men looked on grimly. If Lord Woldingham stumbled, it would be they who would be called upon to hoick him from the mud.

The hillside, I was explaining, would be transformed into a staircase for giants, each tremendous step lipped with stone so that the water fell clear, a descending sequence of silvery aquatic curtains.

‘And it will strike each step with great force, will it not?’

‘That will depend upon how tightly we constrain it. The narrower its passage, the more fiercely it will elbow its way through. This is a considerable height, my Lord. When the current finally thunders into the lake below it will send up a tremendous spray. Has your Lordship seen the fountain at Stancombe?’

Here is my cunning displayed. I knew perfectly well what would follow.

‘A fountain, Mr Norris! Beyond question, we must have a fountain. Not a tame dribbling thing spouting in a knot garden but a mighty column of quicksilver, dropping diamonds. I have not seen Stancombe, Norris. You forget how long I have been out. But if Huntingford has a magician capable of making water leap into the air – well then, I have you, my dear Norris, and Mr Rose, and I trust you to make it leap further.’

The Earl of Huntingford is another recently returned King’s man. Whatever he has – be it emerald, fig tree or fountain – my Lord, on hearing of it, wants one the same but bigger.

So now, of a sudden, I am his ‘dear’ Norris.

This fountain will, I foresee, cause me all manner of technical troubles, but the prospect of it may persuade my master to set apart sufficient funds to translate my sketches into living beauties. It is marvellous how little understanding the rich have of the cost of things.

‘My master,’ I wrote. How quickly, now the great levelling has been undone, we slip back into the habits of subservience.

*

This morning I walked out towards Wood Manor. I set my course as it were on a whim, but my excursion proved an illuminating one.

The road curves northward from the great house. I passed through a gateway that so far lacks its gate. Mr Rose has employed a team of smiths to realise his designs for it in wrought iron tipped with gold.

The parkland left behind, the road is flanked by paddocks where my Lord’s horses graze in good weather. It is pleasantly shaded here by a double row of limes. Their scent is as heady as the incense in a Roman church. The ground is sticky with their honeydew. The land falls away to one side, so that between the tree-trunks I could see sheep munching, and carts passing along the road wavering over the opposite hillside, and smoke rising from the village. It was the first time for several days, sequestered as I have been, that I had glimpsed such tokens of everyday life. I had not missed them, but I welcomed them like friends.

I became aware that I was followed by an old woman, the same I had now seen twice already. My neck prickled and I was hard put to it not to keep glancing around. I was glad when she overtook me and went hurriedly on down the road.

I had not intended to make this a morning for social calls, but it would have seemed strange, surely, to pass by Miss Cecily’s dwelling without paying my respects. I had told Lord Woldingham, before setting out, that I needed to acquaint myself thoroughly with the water-sources upon his estate. He seemed surprised that I might think he cared how I occupied myself. He was with his tailor, demanding a coat made of silk dyed exactly to match the depth and brilliance of the colour of a peacock’s neck. The poor man looked pinched around the mouth.

The house Lord Woldingham is creating will extend itself complacently upon the earth, its pillars serenely upright, its longer lines horizontal as the limbs of a man reclining upon a bed of flowers. Wood Manor, by contrast, is all peaks and sharp angles, as though striving for heaven. The house must be as old as the two venerable yew trees that frame its entranceway. As I passed between them I saw the sunlight flash. A curious egg-shaped window in the highest gable was swiftly closed. By the time I had arrived at the porch a serving-woman had the door ajar ready for me.

‘Is Miss Cecily at home?’ I asked.

‘You will find her out of doors, sir,’ she said, and led the way across a flagged hall too small for its immense fireplace. An arched doorway led directly onto the terrace. Cecily was there with an elder lady. Looking at the two of them, no one could have been in any doubt that this lady was her mother. The same grey eye. The same long teeth that give Cecily the look (I fear it is ungallant of me to entertain such a thought, but there it is) of an intelligent rodent. The same unusually small hands. Both pairs of which were engaged, as I stepped out to interrupt them, in the embroidery of a linen tablecloth or coverlet large enough to spread companionably across both pairs of knees, so it was as though mother and daughter sat upright together in a double bed. The mother, I noticed, was a gifted needlewoman. The flowers beneath her fingers were worked with extraordinary fineness. Cecily appeared to have been entrusted only with simpler tasks. Where her mother had already created garlands of buds and blown roses, she came along behind to colour in the leaves with silks in bronze and green.

I addressed my conversation to the matron.

‘Madam, I hope you will forgive the liberty I take in calling upon you uninvited. I am John Norris. I have had the pleasure of meeting Miss Cecily at Wychwood. I was walking this way and hoped it would not be inconvenient for you if I were to make myself known.’

She replied in equally formal vein. So I must be acquainted with her nephew. Any connection of his was welcome in her house. She hoped I enjoyed the improved weather. No questions asked. No information divulged. The maid brought us glasses of cordial while we played the conversational game as mildly and conventionally as a pair of elderly dogs, in whom lust was but a distant memory, sniffing absent-mindedly at each other’s hinder parts. But then she demonstrated that she could read my mind.

‘I suppose young Arthur has told you that I am deranged? You will be puzzled to find me so lucid.’

Cecily murmured something, but the older lady persevered. ‘He tells everyone so. He has reasons for the assertion. One is that there is some truth in it. My mind’s eye sees the world’s affairs in a manner as blurred and uncertain as that with which my corporeal eyes see that tree. Fine needlework, as you observe, I am good for, but for keeping a lookout I am useless. And although in cheerful sunlight like this I can be as bright as the day, in dark hours I grow dull.’

‘I am sorry to hear it,’ I began awkwardly. She didn’t pause.

‘So you see, judging that to lie unnecessarily is to lay oneself open to exposure when one could be safely armoured in truth, he broadcasts an opinion that is not quite a falsehood, and under this cover he hides his other purposes.’ Her voice trailed away.

Cecily laid down her needle and took her mother’s hand.

‘Mr Norris cannot be as concerned with our affairs as we are, Mother,’ she said. ‘He is an artist. A maker of landscapes.’

‘A painter?’

I explained that, no, the kind of picture I make is not the representation of a scene, but the scene itself. That while God makes countryside, man refines it into landscape (an audacious joke, but one I thought I could allow myself in this secluded place). That nature and the unnatural make happy partners, and flourish when coupled. I said that those painters who depict what they call pastoral scenes seldom or never show brambles or stinging nettles or the mud churned up on a riverbank by herds of beasts. Their pastorals are all artifice, their pastures in fact gardens.

I was becoming excessively wordy. It is mortifying to know, as I do all too well, that when I talk with greatest satisfaction, expatiating on a subject that truly engages me, then I am most tedious. Becoming self-conscious, I fell quiet.

‘Mother,’ said Cecily, ‘you are tired. Mr Norris would like to see our orchard, I dare say.’

The lady appeared sprightly still, but she acquiesced. ‘Lead him to it then, and show him.’

I would truly have welcomed the opportunity to inspect the orchard, which was admirably well set out. I was struck by the fireplaces inserted into a wall, which I fancied must have been of double thickness, with a cavity which could thus be filled with heated air. So peaches and apricocks could lean against warm brick, even when the untrustworthy English sun had failed to shine upon them. This ingenious arrangement was a novelty to me. I would have liked to give it my full attention, but as soon as we were within the enclosure, Cecily turned.

‘I wonder how much Lord Woldingham has spoken to you of me.’

‘Very little, but to say that Wychwood was your home while he was abroad.’

‘Our home yes, but always his house. My parents were not his usurpers. They were his stewards while, for his safety, he could not be with us.’

My eyes, which I believed to be shaded by the brim of my hat, dwelt with pleasure on a blossoming tree. Damson, Damascenum, if I was not mistaken. This family’s divisions formed a familiar tale. Barely a household in the land has not been so cut up. I wondered why she was so eager to take me into her confidence.

‘But he spoke of my mother?’

‘He did, and forgive me for repeating what may distress you, but she is correct in supposing that he told me that her wits had failed.’

‘She is also correct in saying that his motives for so speaking of her are several. That there is a smidgeon of truth in the allegation, she openly accepts, as you have heard. Many people of her age are forgetful. She is no longer so ready as she once was to apprehend new ideas. At night she is sometimes seized by unreasonable fears, and her distress then is painful . . .’

A tiny hesitation. I thought she had meant to say ‘painful to witness’, but had silenced herself for fear of seeming to complain.

I said, ‘She seems as gracious a lady now as she ever must have been.’ I was greatly pleased to see that someone had thought to underplant the apple trees with anemones, so that the blush of the blossom’s fat petals was counterpoised by the blue fringe of the little ground-flowers’ raggedy show.

‘Lord Woldingham is not quite the person he pretends to be. He is considerate.’

I bowed my head slightly. It was not for me to discuss my employer’s qualities with a connection of his.

‘I think that when he asked my mother to remove herself and her daughter from Wychwood, he pacified his own conscience and the opinion of those around him with a pretence that she was incapable. She needed absolute tranquillity, he said, and he could grant her this old manor as a refuge. His wife did not want another mistress in the great house.’

I have so far encountered Lady Woldingham only fleetingly, in London. I would gladly have asked for Cecily’s impressions of her, but we were not under-servants to gossip about those set above us.

‘Now he sustains the myth of her incapacity for another reason. It is a shield for us.’

She had my attention. I would like to have understood her. But we were interrupted. The old woman who had seemed to follow me came through the wicket that led from the orchard out onto a paddock and thence to the woods. A boy, delicate-featured, accompanied her, carrying a basket. Cecily went to her and took her hand.

‘Meg, this is Mr Norris,’ she said. ‘It is he of whom I spoke. He who would make lakes with the well-water.’

The other spoke no word, but regarded me intently.

Soon thereafter Miss Rivers indicated that my visit should be concluded. As I walked away I saw her and Meg pacing, heads together, beneath the fruit trees. The boy was swinging by his hands from an apple bough. It pained me to observe that Cecily walked quite needlessly over a patch of grass where I had noticed the glistening spears of coming crocuses. How many purple-striped beauties must have been crushed prematurely by the wooden sole of her clog!

*

This morning I found myself, unintentionally, spectator to an affecting scene.

The room that serves me as an office overlooks the yard. In times to come, carriages will set visitors down before the new portico. That they will enter the house through an antechamber shaped like a Grecian temple is not, to my mind, Mr Rose’s happiest notion. For the present, though, they come clattering in the old way, by the stables, so that the horses’ convenience is better served, perhaps, than that of the persons they transport.

A din of wheels on cobblestones and the shouting of grooms. I went to the window. A great number of chests and bundles were being lowered from the carriage’s roof. Only the luggage, then, I thought, and made to return to my writing desk, when a man ran across the yard below in a state of undress that shocked me. A footman run amuck. But no, the shirt flapping out of his breeches was fine, its billowing sleeves trimmed four inches deep with lace. The stockings in which he darted so noiselessly over the paving were silken; the breeches, scarce buttoned, were of a lavender hue with which I was familiar, but not from seeing them on a servant’s shanks. That shaven head, that I had never before seen unwigged, bore on its front a face I knew. By the time I had identified him, Lord Woldingham was down on his knees on the cobbles and three small children were climbing him as though he was a rigged ship, and they the midshipmen. He was laughing and snatching at them and in a trice the whole party had tumbled over in a heap. Various bystanders – whom I took to include nurse and nursemaids, governor and tutors – remonstrated and smiled by turns. And all the while the grooms kept on with their work, seeing to the horses and unloading the carriage with an almighty bustle.

The children and their sire had only just righted themselves, and begun to shake off the straw tangling in their hair, when half a dozen riders trotted into the yard. Lord Woldingham turned from his little human monkeys and stood a-tiptoe, until his wife was lifted down from the back of a dappled grey. My Lady is scarce taller than the eldest boy, very pale and small-featured. He could have picked her up and swung her in the air, as he had done to the children, but he was now all decorum. He bowed so gracefully that one hardly noticed the absence of plumed hat from hand, or buckled shoe from foot. I could not see the lady’s face clear, but it seemed to me she made no reference, by smile or frown, to his scandalous appearance, but simply held out a hand, with sweet gravity, for him to kiss.

*

I walked out after breakfast with Mr Rose, at his request, to prospect for a suitable site for an ice-house. In Italy, he tells me, the nobility build such houses, in shape like a columbarium, for the preservation of food.

A broad round hole is made in the ground. It is lined with brick and mortared to make it watertight, and a dome built over it with but a narrow entranceway, so that it looks to a passerby like a stone bubble exhaled by some subterranean ogre. The chamber is filled to ground-level with blocks of ice brought from the mountains in covered carts insulated with straw. Even in the fiery Italian summers, says Rose, the ice is preserved from melting by its own coldness. So the exquisites of Tuscany can enjoy chilled syrups all summer long. Better still, shelves and niches are made all around the interior walls of the dome, and there food can be kept as fresh as in the frostiest winter.

I was inclined to scoff at the notion. We are not Italian. We have neither mountain ranges roofed with snow, nor summers so sultry that a north-facing larder will not suffice to keep our food wholesome. Mr Rose took no offence, saying jovially, ‘Come, Norris. The air is sweet and my poor lungs crave a respite from plaster-dust. You will wish to ensure my stone beehive is not so placed as to ruin one of your fine views.’

He plays me adroitly. At the mention of a vista I was all attention. My mind running away with me, as it has a propensity to do, in pursuit of a curious likeness, I was picturing his half-moon of a building, rising pleasantly from amidst shrubs as a baby’s crown emerges from the flesh of its dam. Or I would perhaps surround it with cypresses, I thought, if they could be persuaded to thrive so far north. Then this humble food-store could make a show as pleasing as the ancient tombs surviving amidst greenery upon the Roman campagna.

(I let that last sentence stand, but note here, in my own reproof, that I have not seen the campagna, or any of Italy. I must guard myself from the folly of those who seek to appear cosmopolitan by alluding to sights of which they have but second-hand knowledge. The Roman campagna is to me an engraving, seen once only, and a fine painting in the drawing room here, whose representation of the landscape is doubtless as questionable as its account of its inhabitants. If the picture were to be believed, these go naked, and many of them are hoofed like goats.)

Mr Armstrong found the two of us around midday. He rapidly grasped the little building’s usefulness for the storage of meat and, accustomed as he is to lording it over his underlings, began to give Mr Rose orders as to where he should place hooks for the suspension of deer carcasses or pairs of rabbits. ‘Once you’ve made us that round house, Mr Rose,’ he said, with the solemnity of a monarch conferring a knighthood, ‘we’ll eat hearty all year.’

He kept rubbing his hands together. It is his peculiar way of expressing pleasure. I have seen him do it when the two fowl – the Adam and Eve of his race of pheasants – arrived safely in their hamper after traversing the country on mule-back. Already his inner ear hears the rattling of wing-feathers and the crack of musket shot. He fought for the King. The scar that traces a line from near his cheekbone, over jaw and down into his neck, tells how he suffered for it. It is curious how those who have been soldiers seek out the smell of gunpowder in time of peace. Most of the keenest sportsmen I know have experience of battle.

‘Have you anything in your pocket worth the showing?’ asked Rose. The question seemed impertinent, but Armstrong gave an equine grin. His back teeth are all gone, but those in front, growing long and yellow, make his smile dramatic. He reached into the pouch, from which he had already drawn a pocket-knife and a yard-cord for measuring, and, opening his palm flat, showed three small black coins. It came to me that it was for the sake of this moment that he had sought out our company. Rose took one up daintily, holding it by its edges as though it were a drawing he feared to smudge. ‘Trajan,’ he said, ‘Traianus,’ and he sounded as happy as I might be on finding a rare orchid in the wood. ‘Silver.’ He and Armstrong beamed at each other, then both at once remembered their manners and turned to me.

‘Mr Norris,’ it was Armstrong who spoke first. ‘If you can give us more of your time, we’ll show you what lies beyond those lakes of yours.’

‘Yes, come,’ said Rose. ‘We have been much at fault in not letting you sooner into our secret. Mr Armstrong and I are by way of being antiquaries.’

The two of them led me at a spanking pace down to the marshy low ground where the last of the lakes will spread and uphill again through bushes until we were on the slope opposing the house, and standing on a curiously humped plateau raised up above the mire.

It was as though I had been given new eyes. I had been in this spot before, but had seen nothing. This mass of ivy was not the clothing of a dead tree, but of an archway, still partially erect. Those heaps of stone were not scattered by some natural upheaval. They are the remains of a kind of cloister, or courtyard. This smoothness was not created by the seeping of water. Armstrong and Rose together took hold of a mass of moss and rolled it back, as though it were a feather-bed, and there beneath was Bacchus, his leopard-skin slipping off plump effeminate shoulders, a bunch of blockish grapes grasped in hand, all done in chips of coloured stone.

We were on our hands and knees, examining the ancient marvel, when we were interrupted.

‘Oh Mr Rose, shame on you for forestalling our pleasure! I have been anticipating the moment of revelation this fortnight.’ Lord Woldingham was there, and others were riding up behind him. Servants walked alongside a cart. There were baskets, and flagons, and, perched alongside them, three boys and a little moppet of a girl – Lord Woldingham’s offspring and the boy I had seen at Wood Manor.

‘Here are ladies come to see our antiquities. And here are scholars to enlighten us as to their history.’ Lord Woldingham was darting amongst the horses. As soon as the groom had lifted one of the ladies down, he would be there to bow and flutter and lead her to the expanse of grass where I was standing, the best vantage point for viewing the mosaic. I would have withdrawn, but Cecily Rivers detained me. It is as gratifying as it is bewildering to me to note that she seeks out my company. I am accustomed to being treated here as one scarcely visible, but her eyes fly to my face.

‘So Mr Norris,’ she said, ‘you have discovered our heathen idol? I told you this valley had supernatural protection.’

‘You spoke of fairies, not of Olympians.’

‘Do you not think they might be one and the same? Our one, true and self-avowedly jealous God obliges all the other little godlings to consort together. Puck and Pan are mightily similar. And this gentleman, with his vines and his teasel, is he not an ancient rendering of Jack in the Green?’

‘The thyrsus,’ I said, ‘resembles a teasel in appearance, but the ancients tell us it was in fact made up of a stalk of fennel and a pine cone.’

She laughed. Of course she did. I was afraid of the freedom with which her mind ranged, and took refuge in pedantry. A dark-haired gentleman in a russet-coloured velvet coat came up. She turned, and I lost her to him. I believe he is my Lady’s brother.

Rose beckoned me away. ‘We’ll leave them to their fête,’ he said. Armstrong remained and I could see, glancing backwards, that he was displaying the Roman pavement as proudly as though he had made it himself.

*

This morning my Lord’s eldest son was drowned. The boy and his brother were playing around the quagmire where lately the father and I had wallowed in mud. He slipped in water barely deep enough to reach his ankle-bone, if upright. He toppled face forward, wriggled round to rise, and in so doing thrust his sky-blue-coated shoulder so deep into the slime it would not release him. He died silently, while the other child whooped and shouted. How great a change can be effected in a paltry minute. The littler boy had made a slide at the base of what will be the cataract. Governor and tutors, seeing how he might so precipitate himself into the ooze, rushed to forestall him. And so the cadet was saved, at mortal cost to the heir. He fell unwatched.

A forester, perilously perched halfway up one of the distant ring of elms, ready to hack off a branch shattered by last winter’s storms, saw him lie, and shouted down to his mate, who began to race down the slope, his arms flailing as he leapt over clumps of broom and young bracken. He was wailing like the banshee; words, in his horror, forsaking him. Desperate to save, he increased the danger. Those near enough to where the poor boy lay to have helped him, looked not towards him, but at the man hurling himself so crazily downhill. So seconds were lost, and so the mud seeped into the little fellow’s mouth and nostrils and stoppered up his breath.

When I saw them clambering over their sire two days ago I thought I was looking at happiness.

Lady Woldingham sits by her dead boy as still and quiet as though the calamity had rendered every possible action otiose. The other children are brought to her from time to time, when their nurses despair of stilling their howls. She looks at them as though glimpsing them dimly, across an immense dark moor. To what purpose speech, in the face of such grief?

I cannot bear to come anywhere near my Lord.

*

The guests have all gone. They will return for young Charles Fortescue’s funeral, but yesterday they started up and fluttered away with a unanimity to match that of a murmuration of starlings. I would that I could do the same.

Ten years ago it was a common thing to see how, when a man’s brother or father was accused, that person’s friends would seem not to notice him when he passed by in the street. One would fuss with the fastening of a glove rather than catch his eye when it came to choosing where to seat oneself in the coffeehouse. Then I thought that we were all cowards, but prudent with it. When a country has been at war with itself every citizen has a multitude of reasons to fear exposure – exposure of miscreancy, but exposure also of those actions which might at the time of their performance have seemed most honourable. Now I think that the shrinking from those marked by misfortune was not the ephemeral outcome of civil war. It was not only that we feared spies and informers. There is something appalling about misfortune itself.

The tribulations of others are our trials. By our response to them we shall be judged, and I fear that, awkward as I am, it is a trial I am bound to fail.

It is less than a week since I wrote in these pages that Lord Woldingham was careless. I thought him boisterous and gay. I made of him a benevolent despot who would fill this house with colour and bustle. I mocked him, just a little, and so timidly that even I could not hear myself do it. I was like a child who thinks his parents omnipotent, and so licenses himself to jeer at them, and then is terrified to see them cry.

There was crying aplenty yesterday, but not from him.

He had not sent for me. But I knew that, however irksome he found my attendance, to stay away from him longer would prove me inhuman.

I found black clothes. Not difficult for me – my wardrobe is sober. When I judged that Lord Woldingham would have breakfasted, and might be walking out in the garden, with his dog Lupin waddling behind, I prepared to encounter him there.

As I stepped out of my room I all but knocked down a maid whose hand was already lifted to beat upon the door. It wasn’t until I looked at the note she handed me that I knew where I had seen her before – at Wood Manor. Cecily apologised for making so peremptory a request but asked me to come at once, and discreetly. My uncertain resolution to offer my condolences to my employer was laid aside in an instant.

There is a horse provided for my use. I told the groom I might be out a considerable while. I am not a confident horseman, but I asked the cob to hurry, and, heavily built as she is, she obliged with a pace that quite alarmed me. She made her way to Wood Manor almost without my guidance. Cecily was waiting in the entrance hall, and led me at once to a small room where the woman Meg sprawled on the rushes in a corner, bundled in a cloak, her head thrown back against the distempered wall, her eyes closed.

‘She has been set upon,’ said Cecily. ‘They chased her with dogs.’

‘Is she hurt?’

‘I think only very much afraid. She is prone to fits. Perhaps she has had one. Our man found her and saw off her assailants and brought her here across his saddle.’

‘I am no physician.’

‘Mr Richardson will be here shortly. But it is not only medicine we need. My cousin’s men harass her and her companions, but I do not think he knows it.’

We stood in the centre of the room, speaking urgently and low.

‘If he is informed, he will surely discipline them.’

‘Today is not . . .’

She was right. I too shrank from the idea of pestering him in his grief. But there was a worse reason for Cecily’s hesitation.

‘They say she killed the boy.’

I began to protest at such idiocy, and then recalled that I myself have been afraid of Meg.

‘But he died surrounded by his attendants. The woodcutters, the other children. So many people were present. Not a one has said that she was there.’

‘They say she can kill with a wish.’

The woman moaned, and a little blood ran from the corner of her mouth. The room smelt of last year’s apples. The sole window was veiled with cobwebs, and kept tight shut. We were as though imprisoned.

‘My mother too. They call the two of them weird sisters.’

I am a man of reason. I live in a nation that has been riven by doctrinal disputes for more than a century. I have listened to temperate, kindly disposed people swear that they will never again feel any affection for a brother, or a friend, because that other holds an opinion they cannot share as to what precisely takes place when the priest mumbles over the wafer of a Sunday morning. I am not an atheist. I marvel, as any natural philosopher must, at the intricate and ingenious thing the world is. But I am sure that, whatever the Creator may be, no human conception of him can be incontrovertibly right. Bigotry is abhorrent to me. But worse even than the intolerance of churches (and chapels, and conventicles) is the frenzy of the weak when fear drives them to blame their fellow beings for the catastrophes which lie in wait for us all.

‘I had thought that that madness was passed by.’

Cecily seemed to be holding herself upright with a great effort. ‘Meg’s teacher was called a witch, and ducked, and died of it.’

‘Before the wars, surely.’

‘There are many who remember it.’

‘But your mother. No one would presume. Lady Harriet is not the kind to be suspected of witchcraft.’

Cecily gestured irritably, a mere twitch of her hand. ‘Witchcraft is a meaningless word. A mere pretext. This is because my mother and Meg both worship in the forest.’

I had no idea what she meant. She didn’t deign to help me.

‘We cannot wait. Go to my cousin and tell him what is being said. Say that my mother is in danger. Here is Mr Richardson. Go quickly.’

In her nature playful gentleness and a tendency to be dictatorial are most oddly combined. I bowed myself out quite sulkily, as the apothecary was ushered quickly into the little room from which I had just been summarily expelled.

My Lord received me calmly, albeit his face looked blurred, as though he had been roughly handled in the night. I delivered my condolences, to which he made only perfunctory answer, and my message, which he seemed to understand more clearly than I did. There ensued much galloping about. A carriage was sent. Lady Harriet, complaining feebly, was brought back with her daughter and ensconced in one of the recently vacated guest-chambers. Her maid came after on a cart. Meg was carried in, still as in a dead faint, with Mr Richardson attending, and laid among cushions on a settle in my Lord’s study.

Lord Woldingham gave orders that all the estate workers should be called together on the grass patch before the house. Once a sizeable crowd had gathered, he took his hat and went out to them, I following along with the people of the household. All in black, he looked oddly reduced.

‘You know that I have suffered a great loss. I speak now to all of you, to those who knew me when I was an infant in this place, and to those who have shared my exile. I have been away a long time. But do not suppose that Wychwood was ever left behind me.

‘We have all observed, from conversing with our grandparents and other elders, that the very first impressions are the most deeply inscribed. Even one who can scarce remember whether it be time to rise or to go to bed will marvel at a butterfly seen half a century ago. Another asks fondly after a dog who died before our King’s father came to the throne, even if he cannot recollect the latter end of that unhappy monarch.

‘I am not yet in my decline, but I assure you that many of the dreary days of exile have been erased from my mind, while pictures from my first three years, passed in this very house, have comforted me in my absence. Yesterday morning my boys were playing with a wooden ark they found in their nursery. I have gone so far, and my homeward course has meandered so unconscionably, it seemed a miracle to see the little dents in the rump of the wooden elephant. It is a marvel that the mind can sling a bridge across so sad a gulf of time, and yet I tell you all that as I handled the toy I could feel again the pleasure with which, as a child, I bit down on that piece of painted wood.

‘The milk-teeth that made those little wounds are shed, but the jaw in which those teeth grew is here’ (at this he tossed back the curled tresses of his long wig as though presenting his throat to be cut). ‘You have yet to know me, but I am one of you. One of the men of Wychwood.’

This was not at all what the assembled listeners had come to hear. A man loses his child, and then alludes to the boy only in passing, as an unnamed player in a scene with an inanimate toy. It seemed as though my Lord had no heart. What did they care about the vagaries of memory? They had expected him to display his mourning to them. The women, especially, appeared downright offended.

This opening, though, was but the overture. Having tuned his instrument, Lord Woldingham launched abruptly into a lament as ardent as the divine Orpheus’s. ‘I have lost a child. Not for the first time. My firstborn left this life, when he himself had barely glimpsed it, before I could ever see him, ever touch him. I was so far away. But my Charles who died yesterday was near to me. My wife brought him to me in Holland, and from thenceforward it was as though I, who had been homeless, had a home. Father and mother can build a house, but it is no more than a shelter from bad weather until a child runs through it. I used to walk by a pond near to my lodging at The Hague, and I thought it dreary. Then this boy came, and chuckled to see the geese come splashing down on the muddy water, and the unlovely mere became delightful. I am thankful that I have two babes yet. But just as a parent’s love is big enough to embrace every child that comes, so it will never shrink to cover over the wound left where one of those precious ones is missing.’

People were glancing up at the windows of my Lady’s apartments on the first floor, but there was nothing to see there.

‘I have been a child in this place, and so have many of you. I have lost a child here. Many of you will have had private cause to grieve over the clashes of our country’s unhappy recent history. You will know, as I do, how it is to mourn. Some of you have already offered me your sympathy. I thank you. Others have held back discreetly. I thank you too.’

He was speaking very smoothly and soberly. I noticed Mr Goodyear looking at him with an appraising air, but not unkindly. I have heard that Goodyear is a bard, whose storytelling has made him a known man in this region.

My Lord proceeded. ‘Some among you have said most generously that they would do anything possible to alleviate the sadness of this time. There is something I would ask of you.

‘A woman has been brought to this house today grievously ill. She has been so frightened and harassed that her mind has become a blank. I do not know whether she will ever revive from this strange vacancy. She is Meg Leafield. She has been a faithful servant of this family, and I would have had her treated with respect as one of my own. Some of you may have imagined you were performing my secret wish in troubling her. I declare most roundly that that belief was mistaken.

‘I am no sectarian. It is my wish, as it is His Majesty the King’s – and he is wise in this – that we should put aside our quarrels and strive to make this a peaceful nation, whose people are united in their desire to see their country prosper.’

The peacock was crossing the elevated lawn behind the assembled listeners. Its attention caught by the gathering beneath it, it interrupted its gawky pavane and turned in our direction. Very slowly, with a loud dry rattling of quill upon quill, it elevated its showy panoply of tail-feathers – green, bronze, purple, black and tawny, all metallic and glinting, a sumptuous medley setting off the blue of the creature’s throat as an immense brocaded skirt shows off the jewel-coloured satin of a stomacher.

Lord Woldingham has longed to see this. I have observed him with Mr Armstrong, one whole afternoon, following the bird around, attempting to interest it in its mate, or in some tidbit or other, in a vain attempt to persuade it to perform the trick for which it had been purchased. Now, as it turned itself this way and that, as though set upon compelling admiration, I wondered whether it would cheer him, or throw him from his intent.

He ignored it. He was saying, ‘I do not enquire into the niceties of your relationships with our Maker. Worship in church or chapel, with vicar or presbyter, or with a wayside preacher whose pulpit is the hedge. It is all one to me, so long as you treat each other with civility. Those of you who have been long abroad, as I have, may have a quarrel with some of our fellows who have flourished here. I say put those quarrels aside. We want no vengeance, no hunting down, no settling of scores. I have heard it said that to make peace with an opponent is shameful and unmanly. I say it is an honourable thing, a wise and benevolent thing, a thing on which God, however you may imagine him, will smile.’

‘I applaud our employer’s breadth of mind,’ murmured a voice in my ear. ‘Surely, though, to speak of “imagining” the divinity is over-bold.’ It was Mr Rose. I was surprised at his addressing me in such an insinuating tone. I dislike whisperers. I nodded, but didn’t turn my head.

Now Lord Woldingham’s rumblings gave way to a thunderclap. He strode through the crowd, and mounted the plinth I have had prepared ready for the ancient marble figure of Flora, which is making its way towards us by painfully slow degrees. My Lord’s agent in Rome purchased it there. Now it is creeping along the canals of France, drawn by huge shaggy-heeled horses. Some time this summer, it will make the dangerous crossing to these shores before being heaved aboard another barge to float upstream to us here. The stone nymph will be twice the height of Lord Woldingham, whose quickness of movement and forcefulness can lead one to forget that he is, in person, just a wisp of a man. But on the plinth, his funereal satins lustrous in the sun, he seemed as darkly substantial as the improbably gigantic bronze mastiffs recently set up as guardians of Wychwood’s new front door. The assembled people had stepped nervously aside to let him pass; now they swivelled to see him again. The sun was in their eyes; he a silhouette against a background of white sky. For the first time he raised his voice.

‘A harmless, helpless woman has been ill-treated here. Shame on you. A member of my own family, to whom you all owe deference, has been slandered. More shame upon you. There has been nonsensical babble of witchcraft. We are not savages, to give credence to such piffle. My son is dead and you foul the pure grief of his family with superstitious blatherings. Let me hear no more of this. Those of you who have frightened Meg Leafield will come to me and explain yourselves. Lady Harriet is my aunt, and my honoured guest. When she pleases to return to Wood Manor, she goes under my protection. Any man or woman who breathes a word against her makes an enemy of me.’

He stood silent for upwards of a minute. No one fidgeted or uttered a word. When he stepped down he did so deliberately, and walked back into the house with the demeanour of one following a coffin, but that his eyes were turned, not to the earth, but upwards as though defying the gloomy clouds to rain upon him.

I went to my office and occupied myself with new sketches for the parterre. Seeing my Lord so elevated had brought home to me how the proportions of the terrace will appear altered once Flora queens it over the space. The eye must be led to her, and the flowerbeds must seem to flow out from her, the bringer of flowers.

*

I am as much a fool as that ridiculous peacock. The fowl, disdaining its proper mate, has become enamoured of one of the garden boys. The display it made for us all yesterday was an attempt to catch the youth’s attention. It follows him around with pathetic constancy.

He was at work in the rose garden as I set off for my walk this afternoon. As he spread horse-dung on the beds (not all of a gardener’s tasks are fragrant), the amorous bird was on the pavement alongside him, its cumbersome fan extended, turning very slowly, first to one side and then to another, as though imploring him to notice how the vari-coloured filaments in its plumage flared and changed in the shifting light.

The boy, who is very young, is being plagued by the others’ teasing. I think he hardly understands the game of love yet.

I walked out towards Wood Manor and had a happy encounter. I have had much to think about these past hours – sad matters for the most part. Yet, as I write these words, I find myself absurdly gay.

*

I will allow yesterday’s entry to stand. At least it is evidence that I am sensible of my folly. There is no dishonour in loving an admirable woman, so long as I refrain from pestering her with my suit.

What seems to me now most reprehensible is that my pre-occupation with things private to myself makes me negligent of my employer’s grief. Lovers, it is rightly said, are solipsistic imbeciles.

Wychwood sitting nearly on the summit of a low hill, the land falls away from it on three sides. To the west, a set of ancient stone steps leads down to a sunken lawn, cupped by steep banks and floored with violets. This was a pond once, made by Romans perhaps, or by the monks who had a dwelling here after the Romans had gone. Mr Green tells me that when his men were levelling the ground they found a rubble of petrified sods within which time and decay had drawn the skeletons of ancient fishes. The tiny bones had dematerialised to leave an effigy of themselves made of nothingness, a vacuity which might, had the gardeners’ spades not chopped them up, have survived, insubstantial and indestructible as the soul is to a true believer, for ever and ever, amen.

I walked there this afternoon. Lupin the pug snuffled about me. When he saw me take my hat and open the door to the garden he came scuttling bowlegged down the corridor to join me, his claws clicking on the flagstones.

The world being full of graceful creatures, it puzzles me why the ugly should be so prized. After I had paced with Lupin half an hour, though, I found myself touched by the fortitude with which he bears the deficiencies of his bodily design. His walk is an ungainly waddle. His skin was made for a being twice his size and bunches around his neck like an ill-fixed ruff. He snorts and grunts, half suffocated. As he struggles for breath, liquid trickles from his nose, and he laps it up with a busy and repulsive action of his tongue, the only neat thing about him.

I was meditating on the capriciousness of Providence, which kills a likely boy too young, and allows the survival of another being so evidently unfit, when I was struck hard at the back of my right knee.

The blow felled me. Half recumbent on the grass, I looked around and could see no sign of my assailant. Kneeling beside me, clucking and fidgeting with my waistcoat buttons, was old Meg. I am ashamed to admit I pushed her back roughly. The pain in my knee was sharp, but I was more shaken by the force of my fall. My previous reverie continued ad absurdum. How much more stable our posture would be, I thought groggily, had we four legs. In this respect Lupin was my superior. Balancing precariously on only two vertical supports, my body – when one of those supports was knocked out from under me – had lapsed to the horizontal with a most unpleasant thump.

Two people shot out of the thicket on the far side of the lawn. One was the boy I had previously seen with Meg. The other was Mr Rose, hatless, and demonstrating that a round belly is no diminisher of agility.

Rose shouted, ‘Are you hurt, Mr Norris?’

He caught the boy and hugged him from behind. The two swayed like wrestlers, the boy’s feet kicking. Meg went to them, met Rose’s eye deliberately and spat on his shoe. He let his arms fall limp. The boy sat sullen where he had dropped.

‘He threw that stone,’ Rose said to me.

He was looking past Meg as though she were of no account. She slapped his face. I was astonished to see him flinch like a chastened scholar. When last I had heard of her, she was lying insensible. Now she was articulate.

‘One boy dead, and you bullying another,’ she said. She tied her shawl crosswise over her chest and returned to my side. She lifted from the ground, not a stone, but a sphere of solid wood, finely turned, about the bigness of an apple and painted blue.

‘The gentlemen give him farthings to find their balls for them, and fling them back,’ she said, addressing me as though we were old acquaintances. ‘That a child should have to pick up toys for grown men!’ There were iron hoops set here and there about the lawn, and mallets propped against a bench.

I sat, then stood. I said to the boy, ‘Men are not rabbits, to be shied at.’ He looked up at me through his hair and I had a shock. His face was that of Lord Woldingham’s deceased son.

Mr Rose approached, stroking the round hat he had retrieved from a bramble. He shook his head at Meg and came to inspect my injury. The damage to my stockings was greater than that to my person. ‘You’ll do,’ he said. He bent and murmured to Meg, and passed on up towards the house.

I turned to the old woman and addressed her formally. ‘Mistress Leafield,’ I said, ‘I have wondered about you. This mishap has at least had the advantage of making us known to each other.’

We hobbled together, I leaning on her shoulder, to a stone bench. There, with Lupin and the boy growling at each other on the ground beneath us, she explained herself, and other things beside.

She was playmate to Lady Harriet, and to my Lord’s father, when they were all infants, because she was their wet-nurse’s child. She stayed with Lady Harriet, studying alongside her. ‘My Lady is an artist,’ she said. ‘You have seen it. The rich don’t honour silk-workers as they do paint-workers, but artists know their own. Mr Rose has the greatest respect for her. He brings the woodcarvers and plasterers to Wood Manor, and urges them to emulate her designs. I, though, was the better scholar.’

I had thought her ignorant and mute. How often in these past few days have I had to repent of a hasty judgement.

‘I learnt mathematics indoors,’ she said, ‘of my Lady’s governor. I learnt physic in the wood, taught by fairies.’ She looked carefully at me with small lashless eyes. I betrayed no scepticism, nor any inclination to burn her alive. ‘You are phlegmatic, Mr Norris,’ she said.

‘I am readier to learn than to condemn.’

The fairies, she explained, came to her not as weird visions, but speaking across aeons of time through the stories preserved and cherished by the people of the locality. From them, and from her own experiments, she had found out ways of using plants as remedies and preservatives. She had discovered that she had the gift of calming the frantic with incantations. She knew how to alleviate pain with simples. ‘There are some agonies which are too piercing for anyone to suffer them and live,’ she said. ‘I can help the sufferer to escape the pain by trauncing, by passing over temporarily into the place of death. There are some who do not return, and I have been blamed for that, but I do not doubt they were grateful to me.’

A silence fell. Perhaps she expected remonstrance. I waited for her to continue.

‘Lady Woldingham is in a grievous state,’ she said. ‘I can help her. Or rather this boy can.’

‘He is your grandson?’ I asked.

She looked taken aback, as though I had displayed extraordinary ignorance. ‘No,’ she said. ‘No, not mine.’

Mr Rose came back down the steps.

Meg called the boy to her. They went hurriedly away through the little bushes.

‘You are shaken up,’ said Rose. ‘Here, take my arm.’ I was glad to do so. It is true that I felt atremble. My face in the looking-glass was like porridge, lumpen and grey. I went to my room and slept an hour or two, as babies do when they have been dropped.

My habits are regular and somewhat ascetic. I rise early, and go punctually to my rest. It is unusual for me to be abed in daylight. Perhaps that is why I had such visions in my sleep. I seemed to be lapped around in a mist in which all colours were present, glimmeringly pale. I was swirled as in mother-of-pearl liquefied. I had no weight. Nothing grated upon me or pinched me. ‘Comfort’ is a state we do not prize enough. It is not so sharp as joy, or so exalted as rapture. But in my sleeping state I felt how delicious it is to be warm, to be wrapped in softness, to feel clean and smooth as milk, to be caressed by things silken and delicate. I rolled as in a heavenly cloud, freed of the dizziness one might feel if truly suspended in air, freed of the downward pressure that makes our flesh a burden to us. I was as jocund as the cherubs on my Lord’s painted ceilings.

The delight, intensifying, awoke me. My knee was aching. The pearly flood in which I had revelled had dwindled to a patch of slime on my sheet. My celestial tumblings had had an all-too-earthly outcome. I am glad that I had not seen Cecily as I dreamt.

I went downstairs to find a lugubrious silence. It is late. I asked for some supper to be brought to my room. I sit now to write in a state curiously suspended between contentment and anxiety.

I think about that boy. I wonder how Meg means to use him for the consolation of the bereaved mother.

*

Walking in the park, I met Cecily Rivers. I showed her the secret garden I am making in the woods for Lady Woldingham. We passed a remarkable few hours. I think it has not, to ordinary observers, been a bright day, but as I view it now, in retrospect, it dazzles me.

The mother of Ishmael told the angel that her name for the divinity was Thou-God-Seest-Me. To be seen, is that not what we crave? An infant reared by loving parents is cosseted by the vigilance of mother or nurse. Fond eyes dote upon its tiny fingernails, the gossamer wisps of its hair. Once grown, though, we fade from sight. We merge with the crowd of our fellows, all jostling for notice, all straining to catch fortune’s eye. To believe, as many do, that God has us perpetually under surveillance must be a very great consolation for our fellow-men’s neglect.

It is years, now, since I have felt myself held in the beam of a kindly gaze. Today, though, Cecily looked at me. She spoke to me. She touched my sleeve and laughed at me. She carried herself towards me not as though I was Norris the fee’d calculator of areas and angles; not as though I was the desiccated fellow politely withdrawing when the company dissolves into its pleasures; not as though I were a kind of gelding, neutered by misfortune and hard work. Thou-Cecily-Seest-Me. She sees me industrious, and full of energy. She sees me bashful, and considers it a grace. She sees that my eyes and hair are brown and my fingers long. She sees that I am a young man, and proud. She sees me not as a paving to be stepped on uncaring, but as a path to be followed joyfully. How do I know all this? Not by words.

I have been startled by her seeing. I have felt the carapace, in which I have lived like a tortoise in its shell, crack and fall away from me.

She did not have to reveal herself to me. She was already admirable in my sight.

What passed between us today is not as yet for writing down. Unshelled, I shudder with happiness, and I am afraid.

*

What I call the ‘secret’ garden is no such thing. How could it be, given that it has been dug and planted not by elves, but by men? It is, however, well secluded.

It was my Lord’s fancy to make his wife a place where she could walk unregarded. He promised it to her while they were still in London. ‘I will refrain,’ he told her, ‘even from looking at the plans. This will be as private to you as your closet. I hereby swear – with Carisbrooke and Mr Norris as my witnesses – that, except in some extraordinary emergency, I will never set foot within its bounds.’ Carisbrooke is a grey and red parrot whom my Lord’s father kept in the castle of that name, when he was there with the late King. It is much given to screeching.