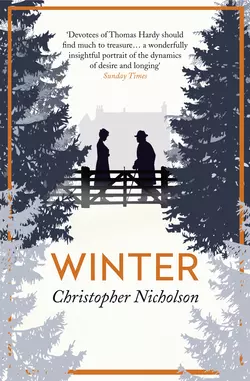

Winter

Christopher Nicholson

In the winter of 1924 the most celebrated English writer of the day, 84-year-old Thomas Hardy, was living at his Dorset home of Max Gate with his second wife, Florence. Aged 45 but in poor health, Florence came to suspect that Hardy was in the grip of a romantic infatuation. The woman in question was a beautiful local actress, 27-year-old Gertrude Bugler, who was playing Tess in the first dramatic adaptation of Hardy’s most famous novel, ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’.Inspired by these events, ‘Winter’ is a brilliantly realised portrait of an old man and his imaginative life; the life that has brought him fame and wealth, but that condemns him to living lives he can’t hope to lead, and reliving those he thought he once led. It is also, though, about the women who now surround him: the middle-aged, childless woman who thought she would find happiness as his handmaiden; and the young actress, with her youthful ambitions and desires, who came between them.

Copyright (#ulink_990e4c4e-1550-5b9d-aa77-279d67bc6b9d)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

4thestate.co.uk (http://4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

Copyright © Christopher Nicholson 2014

Christopher Nicholson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007516087

Ebook Edition © January 2014 ISBN: 9780007516063

Version: 2015-01-28

Dedication (#ulink_9e112e45-4310-5a68-a993-de768a154bad)

To Kitty

(1958–2011)

Contents

Cover (#u6cd6e08a-880d-5e67-a3c2-e4d7a375d7da)

Title Page (#ue6e31c87-1666-5442-9dfa-d81365e09f66)

Copyright (#u73b75214-3498-53f1-bb5a-05ce8d5a68c5)

Dedication (#u01a0f2f4-9393-5a7a-8520-7e70b0b0910e)

Part One (#u7ed28098-e21a-50a9-8705-ef3431175a58)

Chapter I (#u276c7e1d-84fa-52f9-a26a-6dc15062fa74)

Chapter II (#u3e2ccdca-a2e8-5a9a-a9c1-46fed3f455da)

Chapter III (#u2ded2523-deea-5ae5-acc6-2985f81ff57b)

Chapter IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter V (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_07de8a40-55a1-5404-b182-7db9621a0edb)

CHAPTER I (#ulink_cf21e9fc-a7e5-5b50-9198-faaa53308918)

One of the old roads leaving a well-known county town in the west of England climbs a long slope and finally reaches a kind of open plain, a windy spot from which a wide prospect of the countryside is available. Fields of corn occupy the near and middle distance, while the rolling downs further off are grazed by numerous flocks of sheep. Much closer at hand there stands a clump of pines and other trees, the branches of which overhang a brick wall surrounding a dwelling of some substantial kind. Chimneys and a roof may be glimpsed especially in winter, but the wall is of sufficient height to obstruct the gaze of any pedestrians on the road, and the house remains as well hidden as if it were deep in a wood. Most wayfarers pass by scarcely aware of its existence. Yet a few curious souls, noticing a white entrance gate set in the wall, occasionally linger to ask themselves who may live in such a secluded, lonely place.

On a blue November dawn, not long before the present time, an old man might have been observed walking down the short drive that led from the house to the gate. He walked slowly, with a slight stoop, and carried a stick in his right hand. A small dog, a wire-haired terrier, accompanied him, snuffling at the vegetation on either side of the drive.

The drive was flanked by trees, and the depth of shadow beneath their boughs was such that the old man seemed to emerge by degrees out of a dim obscurity. He wore a tweed jacket, a wool tie and trousers of a nondescript colour, and on his head sat a wide-brimmed hat. When he reached the gate he halted, leaning on its top rail and scrutinising the world beyond. His moustache and eyebrows were pale, his face lined by a lifetime of experience and thought. While the down-turned nature of his mouth suggested a deeply ingrained scepticism, his eyes were keen and sharp and the wrinkles at each corner seemed to contain a distinct humour.

So, at least, he imagined himself. Not that bad for eighty-four, he thought, with a certain touch of vanity.

The road itself was empty, little traffic using it at this early hour on a Sunday. An erratic breeze blew, stirring the pines above his head. In the air hung a damp, resinous fragrance often encountered in wooded parts of the countryside in the last stages of autumn. This was, with the possible exception of spring, the old man’s favourite season, the year quietly burning down and the steady passage of time made visible by the lowered sun and shortened days.

There was no sun today, or none visible, but the light was gradually increasing and the sombre blue of the air had turned to a dull grey as he retraced his steps. The drive curved around a thick shrubbery and brought the front of the house into view. A handsome brick edifice, it had been built to his own design, and he was as proud of its dark slate roof, imposing porch and low turrets as he was of some of his literary works. The piece of land on which it stood had formerly been nothing but a bare pasture exposed to the full force of the prevailing westerly wind, and the trees that now encircled and protected it had taken forty years to grow to their present height. Inspecting the garden always gave him considerable satisfaction, and he strolled here and there, occasionally turning his head to follow the progress of the dog or to listen to the song of some bird. The lawns were thick with freshly fallen leaves. After a time he retired indoors, leaving his stick in a corner of the porch and hanging his hat on a wooden peg.

The house was too far from the town to be supplied with electricity, and all artificial light came from oil-lamps. One such had been lit in the dining room, where the old man ate breakfast in the company of his wife, Florence. He had married her a decade earlier, his first wife having died unexpectedly. They sat at opposite ends of the table and by mutual agreement talked very little; early morning was never a good hour for conversation. It being a Sunday, the newspaper had not yet been delivered, and she seemed content to read a book while sipping her coffee. The room was rather chilly, and around her neck she wore a fox stole. The head of the fox, with its glass eyes, dangled over the book.

She had a round face, dark brown hair tied in a bun, and heavy-lidded eyes that gave a powerful impression of melancholy. The old man wished it could have been otherwise, for his own personality had melancholic tendencies which would perhaps have adjusted to some counterbalancing force. Still, one was what one was. His outlook on Life, his essential philosophical beliefs, had been formed long ago. At his age he could hardly expect himself to change.

He drank tea, and ate bacon and toast. The dog sat by his side, saliva spooling from the edges of its mouth, uttering polite whines. ‘Wait, Wessex,’ the old man chided. ‘Now now. Where are your manners? Stop begging.’ But the begging was a regular part of breakfast, and as happened every day the whines grew more urgent and insistent until the old man at last dangled the bacon rinds above the dog’s nose. ‘Gently. Gently. Don’t snap. There.’

Once he had finished he wiped his fingers on his napkin and drained his tea. As he rose from the table Florence looked up with an anxious expression and appeared on the point of speech, but then chose to remain silent. The old man was relieved: her anxieties were almost always unnecessary, and at this hour of the day his mind was on his work. But, out of kindness, he felt obliged to say something.

‘How are the hens laying?’ he asked.

The abruptness of his inquiry seemed to startle her, and it took a moment before she gave the reply that they were laying well. ‘I think they are laying well,’ she corrected herself, as if experiencing a degree of uncertainty on the matter. But the old man’s interest in the hens was limited and he was disinclined to be drawn into further talk. He nodded and left her, the dog trotting at his heels.

Adjacent to the dining room lay the hall. It was simply furnished: a grandfather clock stood and ticked by the side of a flight of stairs, a black telephone gleamed on a small table, and a barometer in a mahogany case hung on one wall. The old man went up the stairs, turned right along a short corridor and entered the study which was his daily refuge, even on Sundays. Wrapping a woollen shawl around his shoulders he settled at his desk, while the dog curled up on a rug.

The observance of an unvarying routine was one that the old man valued highly and that, he believed, contributed in large measure to his productivity as a writer. For many years he had begun each day with a walk around the garden, in the belief that the fresh air invigorated his brain; likewise, for the same indeterminate number of years, he had withdrawn after breakfast to his study, where he remained for the whole of the morning and the greater part of the afternoon. The chair on which he now sat had served him for much of his life, and the worn condition of its tapestry seat – the once bright floral design now chiefly bare sacking – bore testament to the thousands of hours in which he had been engaged in literary endeavour. The desk itself had also done long service, and despite its inanimate nature stood in the category of a friend. The shawl draped over his shoulders he held in the same affectionate regard.

When seated here, pen in hand, he did not feel old. Physically, he was aware how much he had declined – he no longer felt safe on a bicycle, and it was many years since he had danced – but in his mind he felt as strong and vigorous as he had done in his youth. Yet he was aware that he did not always achieve very much. This was particularly so in the last few months; some days he made no progress at all, and spent long periods staring at a blank page or making inconsequential notes. However, routine was routine, and if he did not try to work he would achieve nothing at all. Behind him lay a string of novels and hundreds of poems, and to break with the habits of a lifetime merely because he happened to have reached a certain age was impossible. Even if he had received some authoritative assurance that this day was his last on the planet, he would have spent it in the same fashion, writing as best he could. Perhaps he might have drunk a glass of champagne at lunchtime, and perhaps if the weather had been good he might have taken a short stroll; but it would not have been in his nature to have done anything out of the ordinary. When it came to a consideration of possible ways of drawing to a close his earthly sojourn, the thought of being at his desk, with the ink drying on the last words of a final poem, was an altogether agreeable one.

This morning he found himself singularly lacking in inspiration, and he knew the reason well enough: in the afternoon he was expecting a visitor for tea, which was the meal he nowadays preferred for social intercourse. In its favour, above all, was its brevity; guests who came at four had generally left by five. Visits of any longer duration tended to leave him exhausted.

She was a young woman by the name of Gertrude, although in his mind he always called her Gertie. He had been thinking of her visit for days, not only because he always enjoyed her company but because there was a certain proposition that he intended to put to her and he was interested to see how she reacted. He admired her greatly. The daughter of a local tradesman, she was in every way a product of the Wessex environment and yet she possessed qualities that, in his mind, put her on a superior plane. He remembered how disconcerted he had been when, some years earlier, he had heard of her impending marriage to a man who came from the town of Beaminster. Beaminster lay in the far west of the county, and men bred there tended to have the slow, plodding qualities of the oxen that had once been used to plough the heavy soils found in the surrounding countryside. Love blooms in the most unlikely of places, but he could not entirely repress a feeling that, as the saying goes, she might have done better for herself.

He wondered what she would be wearing. She always dressed with remarkable style and taste, yet it was perhaps true that she would have looked elegant whatever her dress.

Preoccupied as he was, the morning was an undoubted failure from an artistic consideration, and when after a frugal lunch he returned to his desk he was again unable to write anything of any worth. His impatience grew, and after the grandfather clock in the hall had struck three he changed from his old trousers into a pair of more respectable tweeds. He watched for her from a window, stroking his moustache as the sky behind the trees grew darker. Below him, Mr. Caddy, the gardener, could be seen plying his rake on the lower lawn, barrowing up leaves and wheeling them away.

The dusk was already thick when he discerned her figure on the drive. For fear of being observed at the window he stepped back a pace, and when he heard the ring of the bell, immediately followed by a volley of loud barking from Wessex, he hurried back to his study. Then there came a knock on the study door from one of the maids. The house had two maids, one called Nellie, the other Elsie, so similar in manner and appearance that he often mixed them up.

‘Mrs. Bugler has arrived, sir. And Mrs. Hardy told me to say that she is not feeling well, sir. She hopes you can manage by yourself.’

The old man was neither displeased, nor very much surprised. Probably a head-ache, he thought.

‘Is there a fire lit?’

‘Yes, sir.’

He stood up and collected himself. Upon checking his apparel he discovered that at some point during the previous hour the top three buttons of his trouser fly had mysteriously unbuttoned themselves. He fumbled them shut, stepped into the corridor, descended the stairs and crossed the hall.

Gertrude Bugler was at this time in her mid-twenties and at the height of her beauty, although varying opinions as to the source of that beauty might have been put forward. Her hair was a conspicuous feature; thick and very black, with tresses that shone in the light of the fire, it was the kind of hair that in a former age might have adorned the head of a Cleopatra or a Helen of Troy, and a man with an imaginative cast of mind might have wished himself transmuted into a comb, merely for the pleasure of being drawn through its length. Yet another admirer might have noticed her lips, which were perfectly shaped, full and generous and red, with just the hint of a pout, and a third have chosen her face, which was faintly oval, her complexion smooth and pale. Her eyes were what most men noticed. Wide and innocent, with a bright, liquid sparkle, they hinted at a great depth of emotion and sensibility.

She was by the fire in the drawing room, tickling Wessex, who was flat on his back with his paws in the air.

‘How good of you to come.’

She straightened, smiling.

‘I am afraid Mrs. Hardy is unwell, but she sends her best wishes.’

She was wearing a green skirt with a white blouse and long grey cardigan, and despite the best efforts of the wind not one hair of her coiffure was out of place.

The old man drew the curtains. ‘And your baby is in good health?’ was his next inquiry, for he knew how women always loved to be asked about their children. ‘What is her name? Diana, is it not?’

She agreed that it was. ‘She is very well, though she doesn’t sleep very regularly at night. She always wakes up about two o’clock, bright as a daisy, which is a little inconvenient.’

‘What do you do when she doesn’t sleep?’

‘I sing to her, but it doesn’t always work. Sometimes I bring her into my bed, but she kicks.’

‘I am sure she is very beautiful, if she is anything like her mother.’ His success in managing this compliment delighted him enormously. ‘You should bring her here some time. I should love to see her. Mrs. Hardy and I never see enough children,’ he added a trifle wistfully.

After a quick knock the two maids came into the room together, each bearing a tray – one with a teapot and crockery, the other with a plate of tiny white sandwiches from which the crusts had been cut. They put the trays down on a small table. With Florence not there, Gertie played the part of hostess and poured out the tea.

Once they were settled, they began to discuss theatrical matters. Gertie was a member of a local amateur dramatic company, and was currently playing the leading role in a play that would be performed in less than three weeks’ time in the town’s Corn Exchange. The old man was intimately involved, being the author of the play, a dramatic version of a novel that he had written some thirty years earlier, and he asked her a series of questions: how rehearsals were going, whether the actors and actresses knew their lines, and whether any of them had seen their costumes yet. Her answers were that, in general, all was going well – although one of the actors was growing a moustache that was still not particularly convincing. The old man, amused by this, stroked his own moustache, and sipped his tea. Then he came to the point for which he had been waiting.

‘Over the years,’ he said, ‘various people in the theatre business have asked permission to stage the play in London. I have always been rather opposed to such an idea, but lately I have been approached by Mr. Frederick Harrison – the manager of the Haymarket Theatre. The Haymarket is one of the best theatres in London, and Mr. Harrison seems very enthusiastic.’

He was aware of her attentiveness. She was sitting on the sofa, very upright, with her cup of tea on her knees, but her eyes never left his face.

‘Of course, if the play is to end up on the London stage, the question of who should play your part – the title role, the part of Tess – arises. There are a number of well-known actresses who have expressed considerable interest. However, some while ago, if I remember rightly, you asked me about the possibility of acting in a professional capacity, and I feel that you should have first refusal.’

His voice could not have been more cautious, but she answered immediately that she would love to play the part.

‘It is very uncertain,’ he told her. ‘Nothing is definite. The reviews may not be good enough. But Mr. Harrison’s plan, as I understand it, is to put on a production next spring, or in the early summer.’

‘What of the rest of the cast?’

‘They will be professional actors, of course.’

She seemed momentarily overwhelmed. Her lips were slightly parted; her teeth shone. He could sense the excitement running through her body. A slight flush even spread over her face.

‘You must think about it carefully,’ he advised. ‘Talk to your husband. It would involve staying in London for some time.’

‘O, but my husband won’t mind, not at all!’

‘Perhaps. But there is also your baby to consider. If, after consideration, you are sure you would like to do it, I will write to Mr. Harrison. I am neither encouraging nor discouraging you, although I can see you on the London stage. You would be a great success.’

The old man believed this sincerely. She was an actress of great expressive talent, and not only in his own estimation: London critics who had seen her perform in previous local productions had showered her with praise.

‘I don’t know how to thank you,’ she said.

He modestly disclaimed all influence. ‘There is no need to thank me – it is nothing to do with me, and it may come to nothing.’

They talked of it for some time. Seeing how much he had raised her hopes, he repeatedly counselled caution, telling her to look at it from all aspects. Acting in a professional company would, he said, be very different to acting with amateurs and he would entirely understand it if in the end she decided against going to London. ‘As I say, there are other actresses willing to play the part – including Sybil Thorndike, I believe,’ he added dryly, unable to resist dropping the name of one of the most famous actresses of the day into the conversation.

Gertie was barely listening in her excitement.

‘As early as the spring? How long will it run for?’

‘I imagine that depends on its success. You must meet Mr. Harrison. He may well come down to see the play here – Wessex! Wessex, do stop that! Stop dribbling!’ he said, for the dog was pestering her for a sandwich.

‘May I give him one?’ she asked.

‘If you like.’

He watched as she held out a sandwich. Wessex took it from her fingers with remarkable delicacy, given his usual propensity to snatch. She smiled.

‘I believe you spoil him.’

‘Ah, he is an old dog. He is too old to be spoiled.’ The old man was vaguely conscious of a desire to be in Wessex’s position, licking her fingers. ‘He likes you,’ he said.

‘I feel honoured,’ she said, ‘even if it is cupboard love.’

He tossed out another compliment. ‘You are a favourite, Gertie. He likes you more than anyone else.’

She left a little later, thanking him again as she put on her coat. From the porch he watched as she disappeared into the darkness.

Once he had shut the door the house seemed unusually quiet, as if reflecting on what had passed. He stood by the grandfather clock, listening to its slow, measured ticks and the intervening silences, frowning slightly. He was conscious that he might have started a fire that would be hard to control. Should he have waited until the play had been performed at the Corn Exchange? What if it received poor reviews and Mr. Harrison changed his mind?

Then he remembered his wife. Reluctantly he went up the stairs to her bedroom. Florence was lying on her bed, with the curtains undrawn and the lamp on the bedside table casting such a feeble light that only her head and shoulders were visible in the general darkness. Her back was turned to him, and as he stood in the doorway and regarded her still shape he wondered if she was asleep. But she became aware of his presence. She turned with opened eyes.

‘Has she gone at last? She stayed a very long time; it’s nearly six o’clock. You must be worn out. Did she bring her baby?’

‘No.’

‘I couldn’t face meeting her. She is always so healthy. I feel unwell even seeing her.’

The old man gave a grunt. ‘She is much younger than you.’

This was true, for Florence was a score of years older than Gertie, but it was also true that Florence’s health was far from good. She had a weak constitution and suffered not only from headaches and recurrent toothache, but also from neuritis, a condition caused by undernourished nerve endings, for which she took some large pills manufactured by a chemist in the town. Nor was this all: less than a month earlier, in London, she had had a surgical operation to remove a lump from her neck. It was to hide the scar that she had taken to wearing the fox stole, an object that the old man had never much liked.

She was wearing it now. She sat up, pulling it tight round her neck. ‘It’s very cold in here,’ she complained. ‘What did you talk about?’

‘Nothing. Nothing of any consequence.’

‘Who was on the telephone? Someone rang.’

‘I didn’t hear it.’

‘It rang several times.’

‘One of the maids must have answered it. I never heard it ring. Perhaps it was a bird,’ he said, rather improbably.

‘Thomas, it rang at least four or five times, about an hour ago. Of course it wasn’t a bird. It was nothing like a bird.’ Her voice was suddenly severe. ‘I certainly didn’t imagine it. I must ask the maids.’

‘I’m sure you didn’t,’ he said hurriedly, not wanting to upset her.

There was a silence between them.

‘I can’t think who it can have been,’ she said. ‘Maybe it was Cockerell. He sometimes rings.’

‘Why would he have rung?’

‘I don’t know. He does ring.’

The conversation was going nowhere.

The old man returned to the drawing room. The fire was burning down – let it burn, he thought, she had gone, she was on her way back to Beaminster, there was no point in wasting more coal. Yet something of her presence remained, even now. The cup from which she had drunk still sat in its saucer, and the faintest smudge of red was visible on the rim. There it had touched her lips – and there she had sat! There – one of the sofa cushions was indented – she had sat only minutes before! Something else caught his eye. On the sloping back of the sofa lay a long black hair.

With some difficulty he grasped it between finger and thumb and held it to the firelight. It trembled and swayed, stirring in the current of his breath like a living thing.

One of the maids entered with a tray. She stopped short at the sight of him.

‘Excuse me, sir.’

‘No, no, go on.’

He watched without a word as she cleared the tea things. Then he went upstairs to his study. He spread the hair on a sheet of white paper and turned up the lamp so that it shone as brightly as possible. In its light the strand of hair gleamed, thick and strong. A hair was merely a hair, but it was the kind of token that, in a romantic age, a secret admirer might have treasured – might have put in a locket and worn on a chain around his neck, and examined now and then when unobserved. According to the common view of such matters he was many years too old for that sort of thing, yet he was reluctant to throw it away. Why throw it away? Only a short space of time ago it had been part of her.

On one of the book-shelves in his study was a small volume bound in green leather, containing the collected poetical works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Of English poets, there was no one whom he admired more than Shelley, a man of blazing courage and single-mindedness, ready to defy the narrow morals and social conventions of his age. The old man pulled down the book and turned its leaves until he reached the title page of a poem entitled ‘The Revolt of Islam’. A long and obscure work, little read nowadays but breathless in ambition and beauty, its opening section was a passionate address to Shelley’s young wife Mary, with whom he had eloped not long before. The section concluded with an image of the two lovers as a pair of tranquil stars, shining like lamps on a tempestuous world. It was on these last lines that the old man placed Gertie’s hair.

As he closed the book and replaced it on its shelf in the bookcase he was conscious of a certain absurdity in what he had done. He was eighty-four! Too old! What a thousand pities that he and she had not met when they were both young. Had she been born earlier, or he later, ‘had time cohered with place’, what then might have ensued? How different their lives might have been!

It was the type of reflection that often appealed to the old man as the subject for a poem: how different lives might have been in different circumstances. Picking up his pen, he dipped it in the ink-well and began to write freely.

The old man’s interest in Gertrude Bugler was a complicated one, and he frequently found himself dwelling on her in the damp days that ushered in the start of winter. At one level, it might be said, he had always been an admirer of feminine beauty, and she was, without question, a radiant member of that company, young and healthy and full of joie de vivre. Yet, as he was well aware, there were other reasons that lay behind his sentiments towards her, and these had their origin in an incident that had occurred many summers earlier, on what he remembered, whether correctly or not, to have been his forty-seventh birthday.

He had spent the day at the house. During the morning he had worked hard on the final draft of a novel, and during the afternoon he and Emma, his first wife, had taken tea in the garden. The sun shone, but he had been in a reflective mood; birthdays always filled his consciousness with a sense of the brevity of life. How many years were left before Death laid its cold hand upon his shoulder? How much more had he to do before he could feel that he had accomplished his life’s aims? True, he came from a long-lived family, but longevity was not something upon which anyone could count with certainty. He was not yet financially secure; and the house was proving much more expensive to run than he had originally anticipated. What if he were to fall ill, or what if, for some reason, his novelistic powers were to leave him? He felt no waning of ability, but there were many examples of writers whose once bright careers had ended badly. Such were the thoughts that came to oppress him, that summer’s afternoon.

There was another reason for the cloud that hung on his spirits. His relations with Emma, which for so long had been excellent, had undergone a sharp turn for the worse. It was not largely his fault, or so he felt. Not long before, she had claimed – he recalled this distinctly – that he loved his mother more than her. This charge had caught him by surprise, although in an earlier novel he had written about just such a problem – there one of the central characters had been fatally torn between the demands made by his mother and those made by his wife.

He had considered Emma’s words – which had struck a gaping wound in his heart – and rejected them. It seemed to him that she was asking him to choose between her and his mother, when no choice was necessary. Surely, he had said to her, it was possible for a man to love and respect his mother, and also to love and respect his wife. The one did not make the other impossible. But this careful, emollient response she had immediately and wilfully misinterpreted as confirmation of his elevation of his mother above her.

In truth, this dispute was merely a symptom of deeper division. They talked less to each other than they had once, and laughed even less. She was dissatisfied here in the country, and lately had begun to make disparaging remarks about the house: ‘an ugly, misshapen house, on the edges of a narrow, ugly, superstitious town’. Such words, never to be forgotten! Now, this very day – his birthday – as they sat over tea, she had gone further, saying that they should sell up and return to London, where they would be among people of their own class and education.

Everything in this offended him deeply, even if he took care not to show it. The house did not, he thought, merit such an attack, and nor did the worthy folk of the town and its surrounding villages deserve to be dismissed in such terms. Among them were old friends and acquaintances, not to mention relatives, whom he had known his entire life; to him they were intensely interesting.

As for returning to London, he could scarcely have been more strongly opposed. True, there was a good deal to be said in favour of London, but even more on the other side. When he and Emma had last made their home in the city, when they had lived in the convenient suburban locality of Tooting – their house overlooking the Common – he had fallen so gravely ill that for a time the doctors, who seemed unable to decide whether he was suffering from a kidney stone, an internal haemorrhage, or some altogether different malady, had doubted that he would live. As he lay in what might have been his death-bed, with a strange glare of light in the room from the snow which, although it was October, had fallen a few days before and was now slowly melting, the countryside had beckoned him with a series of alluring, radiant images and he had understood that he and the city, for all its glitter, would never be wholly reconciled.

Emma had felt the same; she had been delighted to move back to Dorsetshire. Now, it seemed, she had changed her mind! The fickleness of women! Well, he had no intention of leaving. Here he was, and with quantities of novelistic material at hand. Even now, he was brooding on his next story – that of a beautiful young countrywoman destroyed by Fate – which, he thought, might be his best yet. To return to London would be fatal.

Thus the tea which he and his wife took that birthday afternoon on the sunlit lawn, and which, to an observer positioned some distance away and having no knowledge with which to interpret the scene, would have seemed an expression of a warm and harmonious marriage, was in reality a chilly affair in which few words were exchanged between the man and woman.

Towards the end of it Emma had returned to the subject that divided them.

‘I must ask you to change your mind, Thomas,’ she had stated in a peremptory tone.

‘If by that you mean that we should move back to London, I cannot,’ was his reply.

‘Then,’ said she, ‘you are no longer the man I married.’

On this melodramatic note she had left him, stalking across the lawn to the house; and when, that night, he betook himself to bed, he found that she had moved to a room in the attic. Well, he thought, if he was not the man she had wed, neither was she the woman he had met at the altar. ‘Marry in haste, repent at leisure’ – that old saying was as true nowadays as it had ever been – and it struck him, not for the first time, but more forcibly than it had ever done hitherto, that the vows of lifelong love made by each party in the solemn rite of matrimony ran contrary to nature, forcing husbands and wives to endure each other’s company when the fire that had brought them together was naught but ashes.

He slept badly. Waking before dawn and in need of a space of further reflection, he decided on a walk. He took a familiar path, one that crossed the low-lying meadows by the river and that, if followed long enough, led to the little church at Stinsford.

It was one of those lovely dawns often encountered in the Wessex countryside in early summer. The sky was a clear grey-blue, the air deliciously clean, and the birds were singing loudly. A still mist had risen from the damp earth and spread itself like a white lake over the meadows, and as he descended from the higher ground into this thin, gaseous stratum he found his feet, legs and waist swallowed up, while his chest and head remained clear. The pollarded crowns of the willows on the river-bank floated on a bed of nothingness, the rising sun shone brightly on the dancing particles, and the cables of a thousand spider webs swayed and shimmered. How, he asked himself, can I possibly leave this Eden for London?

The path took him close to the buildings of a farm, and he heard light female voices penetrating the vapour. Presently the luminous shapes of the dairymaids, five in number, each one carrying a stool and a bucket, came into view as they made their way from the barton towards the river. To his gaze, they seemed to him as much spiritual as physical beings; humble country lasses, but also angels, he thought to himself. Among them was one whose beauty stood out from the rest, and who fastened on his mind with the power of a dream: a girl with long dark hair and pale features. She and the rest passed down the slope without even a glance in his direction, entirely taken up with their own chatter.

Not being in a hurry, he followed them as they receded into the lake of mist. At first he was frustrated to find that the girl who had so engaged his interest seemed to have vanished. Then she reappeared, only to duck behind the body of one of the cows. He waited, hoping that the uneven textures of the mist might thin enough to afford him a further view of the maiden, and was presently rewarded by another vision of her face, revealing a full mouth, dark eyebrows and large eyes.

She was a type of womankind to whom he was particularly susceptible. When, in thought, he used to picture his ideal woman, the face that he conjured was very like that of this innocent young Madonna of the meadows. How is this possible? he thought. Why has it taken until now for me to find her? What shall I do?

She and the other maids were now settling to their work, each one setting up her stool, and with the commencement of the milking a quietness settled on the scene. He imagined as much as saw the bevy of girls with their cheeks pressed against the smooth bellies of the cows, and seemed to hear the purring sounds of the streams of milk as they struck the sides of the pails.

A conversation between the maids began. Although he could discern neither the exact words, nor even the general sense, he was occasionally able to make out what, from its tone, he took to be a remark addressed to one of the cows. He then became aware, from the looks sent in his direction, that some of the girls had noticed him. Now, had he been younger, he could and would have walked up to them, engaged them in conversation, amused them with some light remark, impressed them – or, rather, impressed her, the maiden of his dreams. But he was middle-aged and balding, and more significantly – for the aforementioned particulars might not have been an insuperable obstacle – he was married. Well, there it was. Destiny had failed him by thirty years.

He left, walking on briskly, but the seed of the vision had germinated. Later that day he had to catch a train for London. He chose a window seat, and as the train left the town he was afforded a distant view of the meadows. The dawn was long past, the mist had evaporated, the milkmaids were gone, she was gone. Unheeding, the train bore him eastwards and finally deposited him in the dirt and noise of the great metropolis. He stayed the night in a small and unremarkable hotel; the next morning, as he walked down the great thoroughfare of Kingsway, crowded with pedestrians on their way to their places of toil, his mind was far away. He seemed to see what he had not actually seen: the girl with her cheek turned against the dappled flank of the cow, her hands kneading the teats and the milk squirting into the pail in alternate streams. A heron rose from the mist, its wings creaking faintly, a scatter of silver droplets falling from its stiff legs. He was so blind to his surroundings that he stepped into the traffic, and narrowly avoided being run down by a cab.

Back home, he made careful, roundabout inquiries of the farm manager, and discovered that her name was Augusta. She was the daughter of Jack Way, who ran the dairy. He knew Mr. Way, of course: a big, busy man whose loud voice often rang out as he bawled at the cows. He had seen Mr. Way wielding a heavy stick, clouting the rumps of cattle that lingered too long.

He made no attempt to contact her, having no possible pretext; besides, he knew himself too well not to fear that, were they to meet, he might be disappointed by what he found. It was better for Augusta to remain as he had seen her that dawn in the mist, a quintessence of unattainable, unapproachable beauty, never to be forgotten. It was she, he now thought, she and no one else, for whom he had been searching for so long; she who would become the model for Tess. The vision of his heroine grew out of the vision of the milkmaid.

A further thirty years had elapsed, and the beauty of the maiden to whom he would never speak had continued to haunt him. In those years – years that included the death of Emma – time had creased and leathered his skin, but she and the scene that she had inhabited so briefly remained unchanged. He associated her with all that pertained to the freshness and serenity of those early mornings in the water meadows: the profusion of pale pink flowers, the clumps of bright yellow kingcups, the dew-soaked grass. Details accrued, without his willing: the occasional squawk from some disgruntled coot on the nearby river, the distant call of a cuckoo.

In old age, naturally, these visions became rather less frequent than they had been hitherto. Then, some years ago, he had attended a rehearsal of one of his plays in the town, and she had appeared once more. He recognised her immediately. ‘Who is she?’ he had asked Harry Tilley, who was directing the play, and Tilley told him that she was Gertrude Bugler, daughter of Arthur and Augusta Bugler, who ran the Central Hotel in South Street. His heart had turned over. His mind was so confused he hardly knew what else Tilley had said, although he seemed to remember one remark: ‘It’ll be a lucky man who ends up putting a ring on her finger.’ He watched her in rehearsal after rehearsal. He scarcely noticed the other actors and actresses, and when he talked to her, her attentive eyes left him half dumb. He found her sympathetic, interesting, eager – everything a young woman should be.

He had never bothered to unfold this history to Florence, when there had been no reason for so doing. A suitable moment had never presented itself, and besides, experience had taught him that in general it was best not to talk to her about private matters, especially those which lay deep in the past; she was easily upset, and inclined to misinterpret things.

Three evenings after Gertie’s visit, he was in his bedroom on the first floor of the house. Wearing night-shirt, dressing gown and slippers, and holding a glass of whisky, he was seated on a wooden chair. He had a small woollen blanket over his legs. Two oil lamps were lit, one stationed by the bed and the other on a side table, and in the pool of light cast by the latter, Florence, seated in another chair, was reading aloud. She too was in her night-clothes, and in addition to a blanket over her legs she had the fox stole wrapped round her neck. Wessex, deep in sleep, one of his sandy-brown ears flopped over an eye, lay on the floor between them.

Ever since the start of their marriage she had read to him at night, usually for about an hour, occasionally for longer. It was part of the routine of their existence together, and an agreeable way of bringing the day to a natural close. Sometimes she read a novel, sometimes from a volume of poetry, so long as it was not too modern. The book that she was presently reading was one of the novels of Jane Austen, ‘Pride and Prejudice’, and for once it was her choice, not his. The old man was enjoying it a great deal. When he had read it last, a very long time ago, he had found Miss Austen a little narrow and strait-laced, but now she seemed to him an adroit observer of the human scene, and he was particularly amused to discern in himself a certain resemblance to the character of Mr. Bennet, the distant and reserved father of Jane and Elizabeth. In a pause between chapters, he said as much: ‘Do you not think I resemble Mr. Bennet, to a degree?’

Florence saw the likeness instantly. ‘Yes – you do, a little. Quite a lot, in fact.’

He nodded, pleased.

‘I very much hope I do not resemble Mrs. Bennet,’ she responded.

‘Not in the least.’

‘She is such an empty-brained chatterbox.’

‘You are not in the least like Mrs. Bennet.’

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘What a relief! Shall I go on?’

‘If you like.’

Moments such as this, the old man thought, were part of the success of his life with Florence. She was a good reader, sympathetic to the cadences of the prose, with a gentle, soothing voice. When she had been up in London for her operation, when he had been alone, he had tried reading to himself, both silently and out loud, but it had not worked. Late in the day his eyesight was not good enough to follow the print easily, and in any case it was not the same; just as tickling oneself fails to amuse the tickler, so reading to himself seemed a less than satisfactory affair.

He reached out for the glass of whisky, an inch of which he always drank at night and which helped him sleep. Florence never seemed to sleep that well, although he suspected that she slept better than she claimed. He watched her as she bent over the book. Her hair lacked lustre, her complexion was dull, and she had bags under her eyes. This neuritis – and then the lump in her neck! Despite the operation, she seemed as frightened as ever. Why else did she keep it perpetually wrapped up?

The doctors, he was sure, had not helped. The old man had a natural distrust of doctors that probably went back to the days of his youth, when the English countryside was home to travelling quacks who sold medicines that upon chemical examination were found to consist of no more than flour and water. Although those disreputable pedlars no longer existed, it remained the case that doctors made their livelihoods out of the illnesses of their patients, and a cynic might have suggested that it was in the interests of doctors that their patients should remain unwell as long as possible. The old man sometimes felt that there was more than a little truth in the notion. Florence seemed to derive such pleasure from her visits to her London doctors.

It was inevitable that the contrast with Gertie, who was such a picture of health, should cross his mind. Of course, he reminded himself, she was younger than Florence by perhaps two decades. Florence was forty-five. How old was Gertie? Twenty-four, twenty-five? In a trick that no doubt came from his long career as a writer, he slipped into a kind of trance in which he pretended that she, not Florence, was sitting here now, reading to him.

‘Thomas!’ she broke into his reverie. ‘Do you want me to go on?’

‘If you are happy to.’

‘I thought you were asleep.’

‘I was listening. I was thinking of Mr. Bennet.’

‘What were you thinking about him?’

‘O … nothing much.’

She read on awhile, and he did his best to pay attention, or to seem to do so, but his thoughts came and went of their own accord. He noted the sparkle of the whisky as he turned the glass; he noted the gleam of Wessex’s nose; he noted the shadows moving on the wall by his bed, among them two of Florence, each cast by a different oil lamp, one darker and stronger than the other. There was also his own double-shadow, shifting. It was common enough to see shadows as reminders of death, but what if they were more than that? What if shadows were owned not only by the quick but also by the dead, or if attached to one side of a shadow was the body of the living man, and to the other his dead self?

He explored the fancy that shadows lived outside time, possessing knowledge and consciousness; that they were not mute but had tongues, and could whisper what they knew of the invisible country beyond. It was a possible subject for a poem, the shadow soliloquising on its corporeal self, and if he had had the energy he would have fetched a pen.

Curious ideas such as these often entered the old man’s mind when Florence was reading. They were like clouds drifting in a clear sky; he enjoyed looking at their shapes and structures, without any sense that they had any great significance.

‘I think I shall stop now. Her sentences are so long.’ She put her hand to the stole. ‘My throat is a little painful tonight. I sometimes feel as if there is something still there.’

‘You should try whisky.’

‘I hate whisky. You know I hate the taste of whisky.’

The old man saw that he had said the wrong thing, or the right thing in the wrong tone. He kept quiet, which seemed the best course.

‘You don’t think there is anything still there?’ she asked anxiously.

‘I am sure there is not. If there were, the doctors would have found it.’

She closed the book and got up from her chair. She smoothed the front of her night-gown, turned down one of the oil lamps and seemed about to leave for her bedroom. Then she paused.

‘Thomas,’ she said, ‘I have been thinking about the trees. We must get them cut back this winter. This is the time to do it. This is the time.’

Although it was far from the first occasion on which she had spoken to him about the trees, the old man was perplexed. Why mention it now?

‘They are so oppressive,’ she went on. ‘Some of them are so big, when they sway in the wind they are so worrying. Imagine if one came down on the house. And they make the house so dark. They shut out the light, even at this time of year. We never see the sun!’

This was a very considerable exaggeration. The sun was low in November, but not so low that the trees hid it for the entire day.

‘They are not at all dangerous,’ he said. ‘I know they make a lot of noise, but they are in excellent health, according to Mr. Caddy. You shouldn’t worry about them; there is no need. They are perfectly safe.’

‘Thomas, they are getting bigger and bigger, they are so much bigger than they were. You can’t deny it. We are almost engulfed!’

Trees were fine things, noble things, thought the old man; he simply did not understand the problem.

‘My dear, this is a very exposed, draughty spot; if there were no trees, imagine what it would be like. I remember it when Emma and I first came here, before the trees were planted. She was always complaining about the wind. If there were no trees, we should be blasted.’

‘I am not talking about cutting them down, it is a matter of cutting back. They are so big. They take so much light. And the spores … the spores are so bad for one’s health.’

She was becoming upset; this was what the neuritis did to her. ‘Let us talk about it another time.’

‘When?’

‘In the morning. Now is not a good time. Has Wessex been out? Wessex? Have you been out?’

‘Yes, he has,’ she said.

They wished each other good night and she departed for her bedroom, where she no doubt took one of the pills that were meant to improve the blood supply to her nerves.

He forgot about the trees straight away. Instead, as he finished his whisky, he again allowed his mind to be occupied by thoughts of Gertie, with her pale complexion, oval face and liquid eyes. Fifteen miles of dark countryside lay between here and Beaminster, but he had no difficulty in bringing her to life. He saw her in her little cottage, standing by the fireside, hoisting her skirts to warm her legs. He saw her red lips as she yawned, and the white of her teeth, and the skin shining on her arms, just as he had once imagined Tess yawning, red-mouthed, arms shining like satin. Gertie was the very incarnation of Tess.

Sighing to himself, he wondered whether he would ever have the opportunity to explain how close she was to his heart. The discrepancy in their ages seemed to make such a disclosure impossible; nonetheless, between them there was a perfect reciprocity of thought and emotion, or so the old man felt.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_f3e59e7f-e5fc-5ace-b1ee-59c102996d56)

Last night I asked him, not for the first time, for indeed I have asked him a number of times, if we could have a few of the branches taken down as the house is now in shadow for much of the day. The problem is most acute in the summer, when we are engulfed by foliage, but even now, with winter almost upon us, the trees are an oppression. They oppress me, they darken my life. This is a dark house. He would not discuss it. I tried again this morning.

‘Thomas,’ I said, ‘forgive me for mentioning it again but we must talk about the trees. I know you are very preoccupied, but this is the right time of year – this is the time for tree work. The birds are not nesting now.’

We were at the breakfast table, and he said nothing, not a word, he looked elsewhere as if he had not heard me. He looked at his toast. He studied his toast. I wondered if I had spoken or if I had merely imagined speaking. Had my senses deserted me? Had my words left my mouth or had they stuck in my throat?

I drew a breath. I pressed on. ‘You said in the summer we could not cut back then, because of the birds, and now it is nearly winter. The servants agree with me – they agree entirely. Mr. Caddy agrees too, I have spoken to him. The trees have to be cut back sometime. And the ivy, too,’ I added, aware that I was annoying him by my persistence, that he would prefer me not to mention the subject.

He looked at his toast as if it was burnt. He fiddled with the handle of his tea-cup.

He believes that the trees must not be touched for fear of wounding them. Can trees be wounded? Trees are not sentient creatures. He talks of mutilation and disfigurement. To care for the feelings of birds and animals is one thing, yet to believe that trees are capable of suffering as human beings suffer is quite another. What of my suffering? I am still not well, I know I am not well. The doctors say that on all accounts I must avoid straining my nerves. Can he not see how the trees are hampering my recovery? Can he not see how I suffer?

‘This is such a dark house,’ I said. ‘I feel everything would be different if there were more light.’

He raised his eyes to mine. ‘Later, Florence, later,’ he said, softly. ‘Not now. I am thinking.’

I fell silent. I could say no more, for the moment. He was thinking; that is, he was thinking about his work; a poem was possibly taking shape inside his head. How should I know what shapes form inside his head? All I know is that on account of the trees I am condemned to shadow. I wish he would understand how dark and gloomy they make the house, and how much the absence of sunlight oppresses my spirits during the winter months, but this it seems is of no consequence when set against the supposed feelings of the trees and the nesting birds.

This is how our breakfasts always are. I am not meant to speak and therefore I do not speak, although in the spaces that might be occupied by speech I often address him with silent questions. When were you ever happy? Were you happy when you were a boy? What could make you happy now? Should we not be happy? Is it not in our natures, is it not part of our beings, to strive for happiness? Has your writing made you happy? Would you not be happier if you were to say, I have written what I have written, enough is enough, and to put down your pen? What iron compulsion makes you continue? Thomas?

My life is full of these unanswered questions.

What irks me, more than anything, is that he is perfectly capable of gaiety. When guests arrive for tea it is as if an electric light were switched on (not that we have any electricity here!): suddenly he becomes a different human being. He chats and jokes and entertains, and reminisces about his childhood and tells confidential witty anecdotes. He performs. None of our visitors has any idea what he is truly like. They marvel at him! ‘What a marvel he is!’ they confide in me as they leave. (O that word, ‘marvel’!) ‘So sprightly! So spry! Such vigour!’ I nod in agreement. As soon as they are gone, the light switches off; he relapses to his former self.

The truth is, he cannot be bothered to make an effort for me, his wife. I who do nothing but make an effort for him, I whose whole life is devoted to him, I who tiptoe after him, lay out his clothes, help him dress, read to him for hours every evening and do all that is humanly possible to make him happy, I am not worthy of the performance.

He left, with Wessie at his heels. O Wessie, Wessie, stay with me, I beseeched him silently, do not leave me now – it was all I could do not to call him back – but they were both gone. I remained at the table with my feelings, my words which I may or may not have uttered. The door closed. My hand shook as I tried to drink my cup of coffee.

I am not suggesting that all the trees should be cut down, merely that those nearest to the house should be thinned. Is that so much to ask? To thin the trees so that light, blessed light, will once again shine freely into the rooms? Was this not his intention when he built the house, forty years ago? The house faces south; it should be filled with sunlight, and yet it is dark. But there is nothing to be done, until later; later, later, it is what he always says; and so the matter is forever postponed, and meanwhile the trees grow ever nearer. The branches are nearly scratching at the panes of the windows, and the gutters are blocked with autumn leaves, and the chimneys are covered in ivy. The air is damp. Even the lawns are affected: they are thick with moss and ugly worm-casts.

I cannot feel that trees are necessarily friendly creatures. In the right situation, I admit, they are pleasant enough. Here they are hostile. Left alone, they will overwhelm the house. This is how I choose to begin my account, which I tell to myself, since there is no one else to tell.

I am busy, too; I have my daily round of tasks. There are the hens to let out of their coop. They have a little field to the side of the garden, away from the trees, in sunshine. I bought this field with my own money, four years ago, since he would not buy it, although he has so much more money than I, although he may well be, according to Cockerell, the wealthiest writer in the entire country. Is that possible? How does Cockerell know? I waited to see if he would offer to buy the field for me, but it did not seem to occur to him. If it did occur to him, he gave no sign of it having occurred to him. I might have asked him directly, but I have my pride. Thus I had to raid my own small savings. That is how things are. That is the way of things.

I open the door of the coop and out they come; seven lovely hens. ‘My beauties, my darlings. How are you today?’ I love my hens and I talk to them in a particular voice which I persuade myself – with what truth I cannot say – they recognise. O, but I am sure that they do. I have names for them all. This is Betty; this is Jess; that is Hetty. Dear little Hetty! That one is Maud.

In the low sunshine they glow with light. Their feathers shimmer. ‘Patience, patience,’ I say to them, ‘patience, my dears.’ They fuss and cluck as I hold up the bag of grain, and then I dip in my hand and throw out the seed. They make a quick rush and begin to peck and stab, and as they do so wheedling sounds of gratitude come from their throats. Even when they are eating! How sweet and contented they are!

It does me good to see such contentment, I who feel so little contentment. It does me good to be in the sun, away from the long shadows of the trees.

I scatter four handfuls of grain. Some of the hens – Betty, and Alice, particularly, are bigger and more forceful than the others. Please, please, I beg you, be patient! I have enough for you all.

They are laying well at the moment. Yesterday, I collected three brown eggs; today, three more, which will do very well for this evening’s dinner. I admit that there are times when I think that I should be kind and allow them to keep their eggs, to sit on their eggs. Would that be kinder? But the eggs would not hatch, there would be no chicks, they would sit and sit and nothing would happen, which would be dreadful for them, they would be perpetually disappointed. I think it is better that I take the eggs, to spare them that disappointment. They are fond of me, they do not care whether I take the eggs.

The sun shines over the field, the birds sing – O, I admit, my ownership of the field does afford me a certain satisfaction, for almost everything else is his. The house and its contents belong to him; they were his long before I became his wife. I live in the shell of his ownership. The field is mine, however, and therefore perhaps, upon further consideration, I am glad that I bought it with my own money, that he did not buy it for me. Yes, I am glad, I think, although I would have liked him to have offered to buy it for me, as he might easily have done. I am not saying that he is miserly but, if I may draw the distinction, he is very careful; he does not realise how much money he has and does not believe it, even when he is told. He avoids conversations about money, just as he avoids conversations about the trees. These are not matters I am able to talk to him about, among so many other matters.

Obstinacy is ingrained into his very nature. It blinds him to common sense. It makes him deaf to all persuasion. Was he always like this, or has his obstinacy grown over the years? He cannot have been like this as a young man. But then, how do I know? I did not know him when he was young. Even though I have seen a number of paintings and photographs, to relate the young man there with the old man now defeats me. Inasmuch as I am able to imagine it, he was exactly the same then as he is now.

To give one instance of his obstinacy: the telephone. I could not understand the nature of his objection, although it seemed to be based on some irrational fear of the instrument. He murmured vaguely: ‘Human beings have succeeded in communicating for centuries without the use of a telephonic apparatus; I do not understand why it must suddenly become a necessity.’ – ‘Thomas,’ I said, somewhat exasperated, not least by the absurdity of the phrase ‘telephonic apparatus’ in this day and age, ‘of course, it is not a necessity; it is a convenience. It would be very convenient to have a telephone here. It would be convenient for ordering groceries, and coal, and for visitors.’

I went on to say that it was becoming odd for us, in a house this size, not to have a telephone.

‘There would be wires everywhere,’ he said. ‘They are very ugly.’

‘We will soon be used to them,’ I countered.

He became a trifle petulant. ‘Florence, I do not want to be used to them. Merely because the world happens to have moved in a certain direction, it does not follow that we have to move with it. Besides, there is the cost.’ (As if he would even notice the cost, when he is so wealthy! The wealthiest writer in the entire country!)

Later, he said that the press would discover the number and that the telephone would never stop ringing. The noise would be an intrusion and would prevent him from working. ‘And what if it rings in the night?’ he went on. ‘Imagine that; we shall be woken by it ringing and you will hurry out and fall down the stairs and break your neck.’ I did not know whether to laugh or cry. ‘Is that likely?’ I asked. ‘Who on earth is going to ring in the night?’ He gave me a particular look, a look that I have come to know well, intended to convey the message that he was impervious to all argument, however reasonable.

I enlisted the help of Cockerell, when he next came to stay. He always pays greater attention to Cockerell than to me, although I am his wife. I took Cockerell aside and asked him whether he had had a telephone installed at his home in Cambridge, and he said that he had had one for four years and that it had come in jolly handy as it was so much quicker than the post and capable of carrying so much more information than the telegraph. Exactly! ‘Well,’ said I, ‘if you would persuade Thomas, I should be very grateful.’ So he said he would – that is, he would try – ‘But, Florence,’ he said, ‘your husband is a very hard man to bring round, once he has set his mind against something.’ – ‘Sydney,’ said I, ‘he is an ox! He doesn’t like anything new; he would like the world to be as it was in eighteen fifty! The world has changed, like it or not. But, please, don’t tell him that I asked you to say anything; if you do, he will set himself against it on principle. He is so prickly nowadays.’

The argument that Cockerell employed was that, if my husband were to fall ill and to need a doctor, a telephone would be immensely valuable and might even save his life. I had told him that much myself, had advanced the self-same point; he had paid not a farthing of attention. Once the point was made by Cockerell, however, it carried more weight; he nodded.

‘Is it not the case that, sometimes, the apparatus remains alive when it should not?’

‘How do you mean, alive?’

‘It is still alive. It listens when it should not.’

‘Thomas –’ I broke in – ‘a telephone is not alive; it is a machine.’

‘What I mean,’ said he (to Cockerell, not to me; although I had spoken, it was as if I had not spoken), ‘is that the line remains open when it should not. The operators at the exchange have the ability to eavesdrop on one’s private conversations, without one’s knowledge.’

‘Where on earth did you hear that?’

‘I believe that it occurs very commonly.’

‘I doubt it very much,’ Cockerell told him. ‘I doubt it very much indeed! The operators are far too busy to spend their time eavesdropping on people’s conversations. Is that truly your main objection to the telephone?’

‘It is one of my objections. If something is possible, then, human nature being what it is, it is likely to happen. You don’t have newspaper reporters poking about all the time, trying to discover details of your private life. It is different for me.’

‘That may be true,’ Cockerell agreed. ‘But I hardly believe –’ he stopped. ‘You see, I never use the telephone for conversation. It is simply a very handy little thing to have, for contacting people, in emergencies. You don’t have to use it yourself.’

Eventually my husband gave way, which pleased me, although I admit that I was slightly aggrieved that Cockerell had succeeded where I had failed. The truth is, he trusts Cockerell’s judgement but does not trust mine; that is the truth.

On the day the telephone was installed, and for several days afterward, he was very irritable and claimed that he had been unable to write a word on account of it. ‘But, Thomas,’ I said, ‘no one has rung! We have not had a single call!’ – ‘No,’ said he, in a very melancholy voice, ‘but I am thinking of it waiting to ring. It will ring sooner or later. It is there, in my mind; waiting.’

Mr. Caddy is wheeling his barrow past the vegetable garden. Mr. Caddy has been gardener here at Max Gate for a long time. He is a man of about fifty, entirely bald, with wide ears, and a ruddy face which comes not only from working all his life out-of-doors but also, I suspect, I suspect strongly, from drink. At my approach he drops the handles in order to touch his forehead.

‘The gutters need unblocking,’ I tell him. – ‘Yes, ma’am.’ – ‘Could you do it soon, please?’ I ask. ‘Before the next storm, if possible. It is almost winter. Winter is almost upon us.’ – ‘Yes, ma’am.’ – ‘And if you could pick up some of these twigs and sticks, and rake the drive.’

He nods and yes ma’ams me for a third time, a little slowly, as if behind his respectful exterior he is laughing at me. Yes, for some unaccountable reason I feel sure he is laughing at me, and that my stole must have slipped. He is staring at my scar. A terror seizes me, it is all I can do not to break down on the spot and gibber like a mad-woman. What has become of me? Pull yourself together, Florence, I tell myself, remember who you are. You are mistress here.

I hold his eye and say: ‘I very much hope we shall be allowed to cut back some of the trees this winter.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’

As I walk on I adjust the stole which, it turns out, has not slipped at all, but I am quite sure that he was thinking of it. Mr. Sherren, the surgeon who performed the operation, said that it was a very neat job and that the scar would fade in time but it has not faded at all; it is still red and ugly, even when I cover it with powder. I hate looking at it in the glass. But I can hardly speak too highly of Mr. Sherren, who is one of the best surgeons in London, if not the very best; of all the doctors I have ever met, he is the one in whom I feel most confidence. As soon as I saw him I felt more confident. He examined my neck with so much care and spoke to me so kindly. He has a very soft, warm voice and gentle hands. I noticed how long and delicate his fingers were, the fingers not of a surgeon but a pianist. His finger-nails were perfect. I said to him, ‘I always knew it was cancerous, but no one ever seemed to believe me,’ and he said, ‘Mrs. Hardy, you have come to the right place.’

When he visited me after the operation we had a long talk in which he told me that as a young man he had been to sea as a ship’s surgeon, which he had loved, and in return I mentioned the years I spent as a school-mistress, and how fulfilling that had been. I said to him (something I strongly believe) that there is nothing more important than education. ‘Sometimes,’ I said, ‘I think I might still be teaching now, but for my wretched health. Good health is such a blessing.’

He was very sympathetic. He said that good health was as important as good education, and that people who have a naturally strong constitution often find it so hard to understand what life is like for those who do not. In my experience that is true, very true.

Mr. Sherren then asked whether my husband was writing any more novels, and I said that he had given novels up completely and wrote nothing but poetry. I went on to mention that I too was a writer, and that I had written several books for children. He was interested and wanted to know more, and of course I had to admit that they had been published a long while ago and that I had written scarcely anything in the past few years except for one or two magazine articles. My days (I said) are so taken up with domestic duties that I have very little time for writing on my own account, and even when I do have time, no energy. I have not written on my own account for a long time, except in my head. Nonetheless, once I have recovered my health, once I have truly recovered, I shall be able to write again. That is what I constantly tell myself, and what I told Mr. Sherren, who said he would be very interested indeed to read anything I wrote. He was certain that I would be able to write again. ‘If there is one thing that I have learnt about life,’ he said, ‘it is that it is never too late.’ There was something about the confidence with which he uttered those words that I found quite inspiring.

I did not tell Mr. Sherren that my husband does not like me to write, although that also is true. When we first met he encouraged me, but soon after we were married this came to an end, or so it seems to me. Indeed I have come to suspect that he despises my writing. He has never said as much, not in so many words, but I have not forgotten what happened over my ‘Book of Baby Beasts’. It was a book for young children, describing the characteristics and behaviour of a large number of infant creatures found in the English countryside, and at the start of each chapter there was a little poem, for all children love the sound of a poem as I know so well from my days as a school-mistress. I always did my best to encourage a love of poetry in my pupils, and every morning after saying prayers and taking the roll I used to read them a few verses. Even now I remember the hush in the class-room and their eager faces, listening intently, drinking in the words.

Many of the poems in the book were written by my husband, but there were five that I had written myself, among them one poem in particular I was very proud of, of which I was very proud (grammar is so important). It was about a hedgehog, Master Prickleback.

My name is Master Prickleback,

And when alarmed I have a knack

Of rolling in a ball

Quite snug and tight, my spines without,

And so if I am pushed about

I suffer not at all.

As I say I was very proud of this poem, which I thought and still think is as good as any of his poems in the book, and I remember that he said that it was very good. However, a year or more after we were married there was a very strange incident when I awoke in the night and heard what I believed to be a baby crying in the garden beneath the window. When the cry came again, I instantly jumped to the conclusion that some servant girl must have left a baby that I should be able to take in and bring up as my own. I had never had this idea before, but now it grew upon me with tremendous force, and I ran through to Thomas, who was asleep, and he rose promptly and together we went to the window. The night was still and warm, with half a moon, but the ground around the trees was all in dark shadow. ‘It is a pleasant night,’ he said, after a time. – ‘I heard it clearly,’ I said, for I thought that he did not believe me; ‘I promise you; I know I heard it. We must search the garden. I am going down. Thomas, I beg you, let us search the garden. I am not imagining it, I assure you. I am sure that there is a baby.’ He hesitated for a moment, and then perceiving my state of anxiety he turned and put on his dressing gown and slippers. Together we went down the stairs. The bolts on the back door sounded very loud as he pulled them back, and Wessie began to bark. I was afraid that he would wake the maids who would think that the house was being burgled and I rushed to let him out. We proceeded into the garden. I was barefoot. The dew was very heavy and silvery blue in the moonlight, and Wessie who was very excited to be out at such an hour raced to and fro. Dogs can smell so well in the dark. I heard the cry again near the vegetable garden; it now had a piteous, mewing quality. ‘There!’ I said. We walked towards it, and found two hedgehogs in the act of congress. Their journey towards each other could be traced by the paths in the dew. Wessie sniffed at them, whereupon they recoiled and curled into their defensive postures. I felt very foolish to have mistaken the cry of a hedgehog for that of a baby, and apologised very much, but he very kindly said that it was an easy enough mistake to make, that the sounds were not that dissimilar and that he might well have made the same mistake himself. Even so, I was so very distressed that it took me hours to get to sleep.

In the morning when we were getting dressed I could see the funnier side of it, and I reminded him of my Master Prickleback poem. ‘We saw Master and Mistress Prickleback,’ I said. To my surprise he claimed not to remember the poem, so I recited it to him. ‘O, yes,’ he said, ‘very good,’ but in a tone that could not have been less complimentary.

‘Thomas,’ I said, ‘it is only a poem for children, you know. It is not pretending to be great literature. Do you think it so very bad? It was meant for children, you know. Children love it.’

He was bending over, tying the laces of one of his shoes. In those days he was still capable of tying his shoe-laces. He said nothing at all, not a word.

‘Please,’ I said, ‘tell me the truth! Do you think it is a bad poem? Is that what you think?’

‘I said that it was very good, if I remember correctly. Did I not?’

‘You did, but your tone seemed to me to indicate the opposite.’

He began to tie the laces of the other shoe. ‘You misinterpret my tone. My opinion is that it serves its purpose admirably.’

He added, as though to soften the blow, that he was sure that children appreciated it, although that was not what I had said, I had said that children love it. There is such a difference between loving something and appreciating it. All the difference in the world! It was clear that he despised the poem, and also that he despised me for writing it. When I say that my entire being felt crushed I am not exaggerating, not at all.

Thus I lost heart. Lacking encouragement, I wrote no more on my own account, and instead I act as his secretary, answering letters, making copies, filing. In addition, I labour (‘labour’ is the word; it is one of the labours of Hercules as I once said to Cockerell) on his biography, using his old notes to piece together the story of his life. I am glad to do so, I do not complain, it is a very sensible arrangement. Who else could do it? All the same, when, as usually happens, he takes my sentences – the sentences over which I have taken so much care – and writes them over in his own creaking style, it is a little galling. It galls me. It is as if he cannot bear to hear the sound of my true voice. After all, I am supposed to be the author of this biography! Is it so surprising that I am a little galled at the way he rewrites my sentences?

I do not complain. Nor do I point out his deficiencies of style. If I dared to do so, I know what would happen: he would not argue or seek to defend himself, but would withdraw into his own fortress. Yet I am not alone: others have commented on his antique vocabulary and his convoluted, Teutonic sentence constructions. Sometimes I think it is as if my husband was a great tree and I stunted from living in his shadow.

Of this much I am sure: that it is not possible for me to write well on my own account until I have recovered my health, and it is not possible for me truly to recover my health until the trees have been cut back. Once they are cut back, I shall feel such a weight lifted off me. But unless and until the trees are attended to I cannot begin to write for myself.

Here I should like to mention my strong belief that the growth on my neck may have been caused, at least in part, by the close proximity of the trees. I believe it is very probable, or if not very probable then at least highly possible, that the invisible spores shed by the trees, countless numbers of which I must inhale each day, play an as yet unknown but significant part in the formation of cancerous growths. Some time ago I asked Dr. Gowring for his opinion on the matter, but Dr. Gowring is next to useless, a country doctor with an inflated reputation, and all he would say, with a supercilious air, and in a decidedly offhand manner which made me feel that I, as a mere woman, should not have dared to give utterance to such a thought, was that there was no scientific evidence to support my thesis about spores. I could barely control my anger. ‘But Dr. Gowring,’ I said, ‘it is possible, is it not?’ With some reluctance, he agreed that it could not be discounted as a possibility.