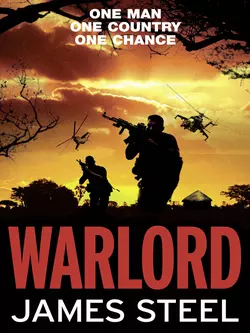

Warlord

James Steel

An utterly gripping thriller that sees former cavalry Major turned hardened mercenary Alex Devereux plunged into conflict in the dark heart of Africa, as he battles bloodthirsty militia in the Congo.China intends to take over the Kivu region in The Democratic Republic of Congo, a tribal slaughterhouse of rival militias who are butchering the local population and fighting over mineral resources.Alex’s mission is to defeat the dominant militia, the FDLR. But details of how Kivu will be governed under the new order are sketchy and Alex must run the gamut of the United Nations, the Congolese army and the clash of superpower claims on the region.Alex knows that the plan is risky. But he can’t resist – could he succeed in bringing stability when everyone else has failed? He and his crack regiment take on their toughest assignment yet. But the road to hell is paved with good intentions and Alex is about to find out why the region has been called the dark heart of Africa…

James Steel

Warlord

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

WARLORD. Copyright © James Steel 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

James Steel asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9781847561619

Ebook Edition © JULY 2011 ISBN: 9780007443291

Version: 2018-07-23

Epigraph

‘There is no book on the Congo, we must write one ourselves.’

Congo Mercenary

Colonel Mike Hoare,

Commander of 5 Commando mercenary regiment,

deployed in eastern Congo, 1964.

Contents

Cover (#uc0f8ae39-92c9-5c8e-a12b-72986b94de1d)

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph (#ua602c3af-dac4-5462-8cab-b3ba9cd6bb41)

Map

In the Beginning

Chapter One

Eve Mapendo sees the figure lit by moonlight.

Chapter Two

‘We are going to make a new country, Mr Devereux.’

Chapter Three

Alex is struggling to get a grip on the scale…

Chapter Four

‘Come on, we’ve got to hurry up.’

Chapter Five

‘You stink of piss.’

Chapter Six

Sophie’s car pulls up to the barrier and the soldier…

Chapter Seven

The megaphone crackles and squawks, ‘Move up!’ and Eve dutifully…

Chapter Eight

Alex taps the end of a wedge into a log…

Chapter Nine

‘Hello, hello, welcome to Panzi hospital! My name is Mama…

Chapter Ten

‘You are joking, Devereux! You are joking! You’ve lost it,…

Chapter Eleven

Eve is lying on her back on a gynaecological examination…

Chapter Twelve

Alex and his men walk up the hill towards their…

Chapter Thirteen

Rukuba finishes his speech to Team Devereux and a strange…

Chapter Fourteen

Gabriel watches the bare legs of Patrice, the FDLR soldier,…

Chapter Fifteen

Alex continues his talk to the Chinese, Rwandan and Kivuan…

Chapter Sixteen

Gabriel is stuck in the narrow tunnel, underwater and in…

Chapter Seventeen

Matt Hooper is a newly commissioned sergeant in the Kivu…

Chapter Eighteen

A huge explosion comes from his right and Jason Hall…

The Promised Land

Chapter Nineteen

The two undercover Unit 17 men have been hanging around…

Chapter Twenty

Alex is standing in front of another group of people.

Chapter Twenty-One

While the troops wait by the helicopters, Zacheus is lying…

Chapter Twenty-Two

Zacheus lies in the bush and waits for the rockets…

Chapter Twenty-Three

Alex hangs on as Demon 6 flares and they decelerate…

Chapter Twenty-Four

Further back along the ridge Alex is collecting Tac, Zacheus…

Chapter Twenty-Five

‘He’s so sweet.’ Eve lets the fat baby boy get…

Chapter Twenty-Six

‘Beelzebub, this is Black Hal, do you copy, over?’

Chapter Twenty-Seven

The slight, middle-aged man wears a cheap suit and an…

Chapter Twenty-Eight

A heavy explosion shakes Gabriel awake at two a.m.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Dieudonné Rukuba stands in front of a large audience seated…

Chapter Thirty

Joseph squats on the ground and looks up as eleven…

Chapter Thirty-One

Eve looks out over the elegant hotel dining room packed…

Chapter Thirty-Two

Sophie points Alex towards the large grass field just inside…

The End of Days

Chapter Thirty-Three

The United States Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs,…

Chapter Thirty-Four

Gabriel heaves himself off the back of the old blue…

Chapter Thirty-Five

‘Well, welcome to Heaven,’ Alex says, spreading his hands and…

Chapter Thirty-Six

Joseph sits on the ground in the new detention facility…

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Alex looks at Rukuba across the table from him.

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Alex looks at Rukuba reclining in his hammock in front…

Chapter Thirty-Nine

The two helicopters wind up their engines on the new…

Chapter Forty

Up on top of the bluff in Tac’s position, Sophie…

Chapter Forty-One

Alex looks at Sophie.

Chapter Forty-Two

A week after the battle at Violo, on 21st June,…

Chapter Forty-Three

Secretary of State Patricia Johnson has expensive blonde hair, shrewd…

Chapter Forty-Four

Joseph and Simon are bursting with excitement as the bus…

Chapter Forty-Five

The helicopter skims low over Lake Kivu. It disappears behind…

Chapter Forty-Six

Sophie turns and looks out of the rear window of…

Chapter Forty-Seven

Sophie is sitting on Alex’s lap after dinner. He has…

Chapter Forty-Eight

Joseph stands laughing on the roof of the cab of…

Chapter Forty-Nine

The Fadoul refinery on the outskirts of Goma is a…

Chapter Fifty

Alex is pacing up and down in the ops tent,…

Chapter Fifty-One

Carla Schmidt and the other journalists are still waiting in…

Chapter Fifty-Two

Joseph and the crowd of young men watch the American…

Chapter Fifty-Three

Alex leans over the shoulder of the door gunner and…

Chapter Fifty-Four

Joseph is near the front of the mob charging towards…

Chapter Fifty-Five

One thousand kilometres away to the northeast, night has just…

Chapter Fifty-Six

Joseph has his face pressed down into the wet grass.

Chapter Fifty-Seven

A shout comes through the trees to Alex’s right.

Chapter Fifty-Eight

The second rifle grenade smashes through the windscreen of the…

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Yamba pours water from his canteen over Alex’s face and…

Chapter Sixty

The helicopter settles down gently on the lawn and sinks…

Epilogue

Author’s Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books by the Same Author

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map

In the Beginning

Chapter One

KIVU PROVINCE,

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

Eve Mapendo sees the figure lit by moonlight.

It has the body of a muscular man stripped to the waist and the head of a kudu, a dark antelope head with two heavy horns spiralling out of it like madness.

The creature stands in an opening in the forest on the hillside above her, at the front of a file of soldiers. They wear black cloth hoods over their heads with ragged holes cut for eyes and mouths. They stand in complete silence; the silver light frosts the surface of every leaf around them.

The horned head turns in her direction, the large eyes darkened by the shadow of its heavy brows.

Her pupils dilate wide as the adrenaline hits them. She clenches her throat muscles and painfully chokes off a scream. It cannot see her in the shadows of the doorway of her shack but she feels its gaze bear down on her like a hard hand gripping her shoulder, pushing her until she crouches on the ground.

The creature unslings the assault rifle from its shoulder, cocks the weapon and gestures to the soldiers to fan out and move down the hill towards the refugee camp. They disappear into the trees.

A whimper of fear escapes her and the baby stirs inside the shack.

She knows what the creature is and she knows what it wants.

Joseph bares his teeth and screams at his enemy.

It’s his first proper firefight and he wants to prove to his platoon leader, Lieutenant Karuta, that he can fight. He’s fourteen or fifteen, maybe sixteen – he doesn’t know. He was born in a refugee camp during a war and he never knew his parents.

He sees the enemy soldiers darting in and out of the trees across the small valley, a hundred metres from him now, firing wild bursts from their AK-47s and shouting insults. They are wearing a ragtag of green uniforms and coloured tee shirts. The bushes next to him twitch and shudder with the impact of their bullets, cut branches and leaves tumble down around him. The men in his platoon fire back with a cacophony of gunfire.

He glances across at Lieutenant Karuta who is yelling away and firing his rifle in long bursts, spraying bullets. Joseph brings his AK up to his shoulder and squints through the circular sight on the muzzle. The rifle is old and heavy, its metal parts scratched and its wooden stock stained a dark brown by the sweat of many tense hands that have clutched it during the decades of Congo’s wars. He’s often cursed its weight as the platoon trudged up and down the countless hills in the bush, but now it feels light and vital in his hands, an extension of himself growing out of his shoulder.

He pulls the trigger and the gun chatters, slamming back hard into his collarbone. It clicks empty and he quickly ducks down, presses the magazine release, yanks it out, flips it over and shoves the spare one, strapped to it with duct tape, into the port. This is his first big firefight but he’s practised these moves over and over again.

He doesn’t know who the enemy are: one of the poisonous alphabet soup of groups in Kivu – PARECO, AFL-NALU, FJPC, one of the government FARDC brigades, even a rival FDLR battalion or one of the many mai-mai militias from the different tribal groups: Lendu, Hema, Nandi, Tutsi. No one knows what the hell is going on out in the bush.

This lot look like a local mai-mai militia. Joseph’s platoon of soldiers are from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, more commonly known by their French acronym, the FDLR. They bumped into the mai-mai by accident as they were coming down the valley side into the village and the fighting broke out in a confused way.

An RPG whooshes off near him, the white fire of the propellant shoots across the valley and the rocket explodes against a tree. The enemy gunfire slackens and they begin to withdraw. This is subsistence warfare and no one actually wants to get killed – what’s the point? You can’t steal, eat or rape if you’re dead.

The FDLR soldiers that he is with start yelling and cheering. Lieutenant Karuta is next to him and Joseph looks at his excited face, eyes filled with laughter. The lieutenant is his father figure. His own father was an FDLR soldier killed when he was a baby, somewhere in the middle of the big Congo war. No one knows where or when – over five million people died so it’s not like anyone paid much attention to him.

Lieutenant Karuta is forty and a génocidaire from the old days in Rwanda. He is a big man in green army fatigues with a wispy beard patched with white that he grows to distinguish himself from the young men under his command.

He waves his rifle joyfully in the air and Joseph joins in. The village is theirs; they must get there before the peasants run off.

They charge down the valley side, jumping over tangles of vines and bursting through bamboo thickets. The ragged line of cheering fighters rushes out of the shade of the trees and into the sunshine. They hold their rifles over their heads as they bound through the waist-high grass towards the collection of round mud huts with thatched conical roofs on the flat land at the bottom of the valley. Villagers burst out of the huts and start running around screaming in panic. Women try to grab their kids, old men stumble and fall, chickens fly up, goats run around bleating. Joseph is laughing with excitement. He’s hungry after weeks in the deep bush living on pineapples and snails.

A woman in a red and blue wrap bursts up from a clump of grass to his right, squawking like a parrot, flapping one arm and dragging a goat on a string with the other. Lieutenant Karuta is onto her, changing direction and chasing fast as she flees down a path into a field of head-high maize. Joseph stumbles, recovers and follows him.

He rushes down the narrow path, the tall green stems blurring past him on either side. Lieutenant Karuta catches up with the woman quickly, kicks the goat out of the way and shoves her in the back so she goes sprawling. The goat runs on over her and the lieutenant has a moment of indecision – do I grab the goat or her?

But her shrieks excite him and he looks down at her on the ground in front of him. ‘Get the goat!’ he shouts to Joseph who squeezes past him and races down the path. The screaming starts.

Weird high-pitched animal shrieks come out of the night from all around the refugee camp. It turns her blood to cold liquid fear in her veins.

Eve crouches inside her shack clutching her baby, thinking, ‘No human being can make that sound.’

She is nineteen, with a broad face, oval eyes, a blunt nose and smooth brown skin. Short and stocky, she wears a patterned pagne wrapped around her body and a plastic cross on a string round her neck. Her free hand clutches it involuntarily.

She and her nine-month-old daughter, Marie, are alone in a shelter at the edge of the camp. She has blown out her tiny candle and crouches in terror in the darkness at the back of the hut. It is ten feet long by four feet high; the walls are made of palm leaves woven onto sticks that are fixed to a frame of branches and she can hear everything outside. A piece of blue and white UNHCR plastic sheeting completes the curved roof. Her boyfriend, Gabriel, proudly made a door for her out of a corrugated iron sheet tied onto the branch frame with some electrical flex he found. He showed her how to tie it shut before he left – ‘That will keep you safe!’

The camp mongrels started barking at the attackers as they came near but this turns to frightened whimpering once the screaming starts. She can hear the soldiers shouting now in Swahili, ‘Over there! Look in that one over there!’ ‘Open up! Open the door!’

Screams of fear come from her neighbours in return.

‘Open the door, or I’ll kill you!’

Some confused banging and shouting.

‘Where is it? Where is the albino?’

More sobbing and crying and then the dull sound of blows and screaming.

Her blood pounds so loud in her ears, she is sure they can hear it. She tries to still her heart – if she can make herself very quiet and very small she might escape. They want her baby but she can’t give it up. Marie starts crying and she forces her hand over her mouth, pressing her face into her breast and smelling her milky baby smell one last time.

The shouting nearby has gone quiet. She hears footsteps approaching the hut. The thin corrugated iron sheet is all there is between her and them. A hand grabs the edge of it and tries to open the door but the flex holds it fast to the branch frame. There is a grunt of anger and then the iron bangs loudly as a machete hacks at the flex. Heaving, banging, tearing, they pull the door off its flimsy hinges and throw it to one side.

The demonic figure silhouetted in the moonlight is half man and half animal. The kudu head and horns look huge. It is stripped to the waist and muscular and in the flat silver light she can see the artery in its neck, beating fast just under the rim of the headdress. It is breathing hard and beads of sweat roll down its chest. The smell of the forest pours into the hut, musty and damp.

Eve cowers on the floor and looks up, wide-eyed in terror. Her hand moves to hold the baby tighter and Marie lets out a loud wail.

The creature holds its Kalashnikov in its right hand and stretches out its left to her. Eve makes a noise of denial, just a whimper. The Kudu is enraged and bellows at her before ducking its long horns under the roof and grabbing her arm. Its fingers are like steel, biting deep into her flesh, dragging her out of the doorway, clutching the baby in one arm. She is screaming now with fear, ‘No! No! No!’

As soon as she is out in the open, a soldier in a black cloth hood shouts excitedly at the sight of the pale baby and hits her in the back with the butt of his rifle. A rib cracks and she makes an oof sound as the air is forced out of her.

She loses her grip on the child and the Kudu grabs it by one arm and lifts it up in the air. It throws back its horned head and howls in triumph. The other members of the gang all join in howling and firing their rifles in the air.

Eve lies winded on the ground until they finish celebrating. The baby is taken away and then they look down at her. Rough hands grab her under her arms and throw her on her back and tear off her pagne. As the first man presses his heavy weight on her stomach, something inside her says, ‘This isn’t happening.’

But the tearing and jabbing continues and she thinks, ‘Why are you doing this to me, God? Why have you made this terrible country?’

Chapter Two

‘We are going to make a new country, Mr Devereux.’

The Chinese businessman looks at him closely to gauge his reaction.

Alex Devereux has the face of a man with strong feelings deeply controlled.

Dark tides run just under the surface but you will never find out what drives them.

His eyes lock onto the businessman’s and flicker with interest before a shutter comes down and he glances away to look out of the window over the lawns of his country house.

Alex has a stern cast to his face, the habit of command engraved on his features by his time as a major in the Household Cavalry and his subsequent career as a mercenary commander. He is six foot four, broad shouldered, lean and fit, running every day up and down the hills of his Herefordshire estate – ‘exercising his demons’ he calls it.

Outwardly he is dressed like a modern gentleman with jeans, loafers and button-down shirt, black hair neatly trimmed; he’s just turned forty and there is some salt and pepper at the temples. But there is a lot more to him than that.

At the moment he is very relaxed with one arm thrown over the back of the old Chesterfield and his long legs stretched out in front of him. It’s April, a shower is thrashing the rose bushes about outside, and it’s cold so he’s lit a log fire in the oak-panelled drawing room of Akerley, the Devereux country house where he lives alone. His family has been there nearly a thousand years, since Guy D’Evereux was granted the land by William the Conqueror. He is currently restoring the house with money from his Russian adventures but it is still always freezing cold.

He looks back at Mr Fang Xei Dong and says, ‘That sounds interesting,’ without any feeling.

It is a measure of how much more relaxed he is about life than before his success that he can be so detached about such a huge project. He refused to go up to London for the meeting and only agreed to it if it was at Akerley. It is also a measure of how interested in him the businessman must be that he agreed to the demand, arriving just after lunch in the back of a chauffeur-driven Mercedes.

Alex was surprised by Fang when his long limbs unfolded themselves like a daddy longlegs from the car door. He is northern Chinese, as tall as the Englishman, with wavy black hair, blue eyes and an angular face with cheekbones that seem painfully large. His skin is smooth and he looks to be about thirty.

When he arrived he strode up the imposing stone steps of the house towards Alex, full of confidence, completely unfazed by his first time in the heart of the English countryside. He thrust his hand out, ‘Hello, my name is Fang Xei Dong but my business name is Simon Jones.’

His English is American-accented but it still has the flat, staccato Chinese diction. He clearly knows that no Westerner will ever get the sliding tones of his name right and doesn’t want them to embarrass them with untoward mispronunciations. He cheerfully laughs off Alex’s polite attempts at saying his name. ‘Don’t worry, in Congo I am called Monsieur Wu. It’s the only Chinese name they can pronounce.’

He talks in rapid bursts, his long arms often reaching forwards as he speaks, as if trying to get hold of some perceived future.

He wears the casual uniform of the modern global businessman: neatly pressed chinos, button-down blue shirt with a pen in his top pocket and iPod earphones hanging down over his top button, a casual black blazer and loafers. When he settles himself in the drawing room he sets out an iPad and two BlackBerries on the coffee table in front of him that beep and chirrup frequently.

He sits forward on the leather armchair now and pushes his narrow-lensed titanium glasses back up his nose with a rapid unconscious dab of his hand; they slip off the bridge of his nose because his head jerks about as he speaks.

‘This operation is completely covert at the moment but I understand from my contacts in the defence community that you are used to operating in this manner?’

Alex just narrows his eyes in response.

‘I am referring to your operation in Central African Republic, which I understand was a Battlegroup level command?’

Alex nods. He is very cagey about his past activities. His CAR mission has achieved legendary status in the mercenary community but they don’t know the half of it. Any mention of the word Russia or any possible operations he was involved in there and he clams up completely.

Fang is reassured by his discretion.

‘This operation will require that level of skill and more. To be candid with you, we realise that it is …’ he pauses ‘…unconventional, from an international relations point of view, and we would prefer to work with a discreet operator such as yourself rather than one of the big defence contractors. They are much more … conventional,’ he finishes, sounding evasive.

Alex knows that by conventional he means law-abiding. He nods politely in acceptance of the point but winces internally. It wasn’t the sort of reputation he had sought at the start of his career. He had always wanted to be able to serve his country for his whole life; major general was what he had been hoping for. Somehow things just didn’t work out like that.

Fang blasts on regardless. ‘I represent a consortium of Chinese business interests that will lease Kivu Province off the Congolese government for ninety-nine years. Under the terms of the lease it will effectively be ours to do what we want with.’

He stretches out his arms and says with a note of wonder in his voice, ‘In Operation Tiananmen we are going to set up a new country and bring order out of anarchy!’

Alex looks at him quizzically. ‘Is that Tiananmen as in Square?’

‘Yes, it means “the mandate of heaven”.’

‘What’s that?’

‘It’s the ancient Confucian right to rule, the basic authority that any government has to have in order to form a country. And you are going to establish it, Mr Devereux. It is our new vision for the world.’

Gabriel Mwamba is twenty-one and in love.

He is an itinerant salesman, pushing his tshkudu cargo-scooter uphill along a narrow track through the forest, breathing hard and sweating, beads of it stand out in his black, wiry hair like little pearls. The tendons across his shoulders and neck stand out and feel like red-hot wires.

He has covered thirty miles in two days over the hills; today he started out at 4am. To dull the pain he is thinking about Eve and how he is going to impress her when he gets back to the refugee camp where she lives. He is an ugly man and knows it, so he realises he has to compensate for it in other ways – he will be a successful businessman.

When he met Eve last year he liked the look of her, small and stocky with good firm breasts and smooth skin. When he heard of her rejection by her husband because of her albino baby, he knew she was the one for him. A fellow outcast. She looked so sad and he just wanted to put a smile on her face.

His own features have been carelessly assembled: his jaw is too big, he has tombstone teeth, puffed-out cheeks and heavy eyebrows. His body looks odd, composed of a series of bulges: a large head, powerful shoulders, protruding stomach and bulging calf muscles. It’s all out of proportion with his short legs, a broad trunk and long arms. Because he knows he looks unusual his face has an anxious, eager-to-please look that irritates people and leads them to be crueller to him than they would otherwise be. However, Gabriel is an optimist with big plans and he never gives up.

He has been reading a French translation of a self-help book – I Can Make You a Millionaire! – written by an American business guru. He has absorbed a lot about spotting opportunities in the market and is sure he is onto one now. Market intelligence is key to these breakthroughs and he listens to his battered transistor radio once a day (to preserve the batteries, which are expensive) to catch the main radio bulletin from Radio Okapi, the UN radio station that broadcasts throughout Kivu.

The local Pakistani UN commander was on the bulletin talking in very bad French about the success of their recent operation against the FDLR and how they had opened up the road into the village of Pangi and installed a Joint Protection Team to allow the market to be held there on Saturday.

Immediately Gabriel knew this was his opportunity. He got together all his money and bought a load of consumer goods off another trader who hadn’t heard the news and was selling them cheap. Pangi had been inaccessible for months so they would be crying out for what he had to offer, and that meant profit. As the self-help book put it: ‘Adversity is spelt OPPORTUNITY!’ It’s a big investment but he is going to make a killing.

The tshkudu he pushes is loaded up with old USAID sacks containing cheap Chinese-manufactured goods: soap, matches, batteries, condoms, combs, print dresses, needles and thread, some tins of tuna (way past their sell-by date), boxes of smuggled Ugandan Supermatch cigarettes and six umbrellas in a bundle. He also has sacks of charcoal from the charcoal trading network throughout the province – he is following one of their secret paths through the woods.

It is heading downhill now into Pangi. The tshkudu is heavy and tugging at his grip. It’s six feet long and made of planks – he built it himself. He hauls back on the handlebars to prevent it from running away from him, digging the toes of his flip-flops into the mud. The trail comes out of the trees and onto a dirt road leading to the village, where he passes the local massacre memorial. The date and number of people killed are scorched with a poker onto a wooden board nailed to a tree: 20 July 1999, 187 people. He doesn’t give it a second look; every village has one from the war.

He is looking to the future and full of hope. At the moment he is a small-time trader, but one day he will graduate to be one of les grosses légumes – the big vegetables, the businessmen in the regional capitals of Goma or Bukavu, running an internet café or a trucking company.

A jolt of fear goes through Gabriel and he stops daydreaming. His step falters and he wants to run away but they have seen him already and to show fear would invite an attack. Three soldiers with Kalashnikovs are lounging at the side of the road on a log, smoking and staring at him through their sunglasses. Like everyone in Kivu, Gabriel is well practised at avoiding attention from the police or the army: his head drops, his eyes look at the ground and his body seems to halve in size as he pushes the tshkudu towards them.

The UN commander said there would be a Joint Protection Team in place but there don’t seem to be any Pakistani soldiers around. That the three men are wearing the plain, dark green uniform of the government army, the FARDC, is bad enough, but what makes them even more of a threat is that they have the distinctive blue shoulder flashes of the 64th Brigade. The Congolese army is made up of militia groups that have been integrated into it over the years and the 64th Brigade is a former mai-mai group, a tribal militia of the Shi people in South Kivu.

Gabriel is terrified of them because he is a Hunde, a member of the Rwandan tribe brought into the province by the Belgians during the colonial era as cheap labour. They are hated by the ‘originaires’, the indigenous Congolese peoples.

If he can just get past this group then he can blend into the market, do his business and sneak out with the crowd at the end of the day. His eyes are wide with fear but he keeps them lowered as he passes the soldiers. Their heads turn and they watch him intently.

Sophie Cecil-Black is feeling carsick and frazzled.

The white Land Cruiser swings round another switchback on the dirt road up the hill and her head swoons horribly.

They’ve been doing this since six o’clock this morning and it’s early afternoon now. Up three thousand feet from Goma to Masisi and then down three thousand feet into the Oso valley and then up another three thousand feet to here.

God, one more swing and I am going to puke.

Saliva pours into her mouth but she tenses her throat muscles and forces the vomit back down.

She looks out of the window. Everywhere around her are stunning views out over rugged hills covered with grassland and small fields. It reminds her of a family holiday to Switzerland in the summer, but she is not in the mood to appreciate the beauty now.

Sophie is thirty-one, six foot tall and slim with straight brown hair, a striking face and a strident manner. Some men think she is very beautiful, others think she is very ugly. It’s the Cecil-Black nose that makes the difference: secretly she used to want to file down the prominent bridge of it when she was a teenager but she has learned to live with it now. She wears a tight green GAP tee shirt, hipster jeans and green Croc shoes.

The Cecil-Blacks are a branch of the Cecil family who ran the British government from the time of Elizabeth I. Sophie went to Benenden, her father is a stockbroker and her mother is very concerned that she is over thirty and not married. Sophie couldn’t care less about that: she knows she is called to higher things and has been doing her best to break the mould of being a safe, Home Counties girl ever since she refused to join the Brownies aged seven. She has a first in PPE from Oxford, a Masters in Development Economics from the School of Oriental and African Studies and an ethnic tattoo across the small of her back.

She is now a project manager with an American humanitarian aid charity, Hope Street, which has a large presence in Kivu and specialises in work with street kids, schooling and training them but she also does general humanitarian work. She leads a team of fifteen people based in Goma, where they have a large training facility.

One of her team, Natalie Zielinski, is sitting in the backseat. She doesn’t get carsick. She’s a small, bubbly Texan with brown, frizzy hair in a bob that never quite works. Sophie likes her optimism, but sometimes finds her irritating.

Nicolas, their Congolese driver, is a slim, self-effacing young man, very glad to have such a cushy job driving for an NGO, it’s a lot easier and safer than the backbreaking life of the peasants in the bush. He is quiet and calm with the soft manner of a lot of Congolese men. He drives smoothly but even that can’t iron out the constant bumping from side to side on the dirt road and those horrible lurching turns.

They started so early because they need to get a load of vaccines to a remote clinic before they go off in the heat. Several thousand dollars worth of polio, hepatitis, measles and other vaccines are packed into coolboxes in the back of the jeep. Once they get them to the clinic at Tshabura they can go into the solar-powered fridge and will be fine for the big vaccination day that they have set up later that week. The clinic is at the head of the Bilati valley and local field workers have spread the word around the farms and villages there, as well as advertising it on Radio Okapi. They are expecting two hundred children to be brought in to be inoculated.

The other reason they started at six is that Tshabura is on the edge of the area under the nominal control of the UN forces. The security situation in Kivu is always volatile; they listen to the radio every morning for the UN security update, like a weather forecast. At the moment their route is Condition Bravo – some caution is warranted, no immediate threat but follow normal security procedures. Condition Echo means evacuate urgently to save your life but it doesn’t happen often. Lawlessness is just part of everyday life in Kivu and Sophie has become used to the daily list of rapes, muggings and burglaries, as well as keeping track of which roads are closed due to militia activity.

After a prolonged security assessment and unsuccessful wrangling with the UN to do the delivery by helicopter, Sophie got fed up with waiting and decided that they could race there in the daytime, get to the clinic, stay overnight in their compound and then race back the next day. White NGO workers are generally safe in Kivu, apart from the usual hassling for bribes from the police and army, but she doesn’t want to be out on the roads after dark when armed groups roam at will.

All these factors are weighing on her mind and she’s also irate because they are behind schedule. They had a puncture on a track that had been washed out by heavy rain and then lost an hour getting over the river at Pinga where a truck had got a wheel stuck in a hole in the old metal bridge.

The car at last comes to the top of the hill and Nicolas pulls up so Natalie can look around the surrounding area and check the map. She scans either side of the jeep and all she can see are lines of green hills in bright sunshine receding into the distance. It is completely quiet but for the noise of a breeze buffeting the car.

‘Daniel Boone would get lost out here,’ she mutters, as she looks back and forth between the map and the view. ‘One hill begins to look much the same as another.’ The map has proved inaccurate already that day and there are no signposts anywhere.

‘Look, can we just get on with it, please,’ Sophie snaps.

‘OK, OK,’ Natalie says cheerfully. ‘We’re on the right route.’

Chapter Three

Alex is struggling to get a grip on the scale of the project that Fang has just outlined.

He stops being relaxed and sits forward, the fingers of one hand pressed to his temple.

‘Hang on; the Congolese government is going to lease you Kivu Province?’

Fang nods confidently. ‘Yes, just like the British government leased Hong Kong from China for ninety-nine years.’

‘OK. How many people live there?’

‘Well, that is a good question actually. No one really knows because surveys are from before the war, but we think about six million.’

‘Six million people?’ Alex looks incredulous but Fang looks back at him unfazed.

‘Yes.’

Alex shakes his head. ‘Why is the government going to do that?’

‘Well, Kivu is actually an embarrassment to the government in Kinshasa. The President promised to bring peace to the country when he got elected but he has failed to end the fighting, or deliver on any of his other Cinq Chantiers policies.

‘The government has no control there. I mean, look at the distances: Congo is the size of western Europe and trying to run Kivu from Kinshasa is like trying to run Turkey from London. Plus there are no road or rail links between the two areas.

‘The government had to get the Rwandan army in to try and defeat the FDLR but that failed. Now they throw their hands up and say it is a Rwandan problem and the Rwandans do the same back to them. No one takes responsibility for it so the whole problem just festers on and will never get solved. I mean, the whole of Congo is just …’ Fang waves his arms around trying to communicate the depth of the exasperation he feels about the country ‘…completely dysfunctional, the country makes no sense. The only reason it exists is as the area of land that Stanley was able to stake out.’

He begins ticking points off on his fingers: ‘The country makes absolutely no sense on a geographic, economic, linguistic or ethnic level. There are over two hundred different ethnic groups in it and the Belgians practised divide and rule policies that exacerbated the differences between them. The only things they have in common are music, Primus beer and suffering.’

Alex is nodding in agreement with this. He has had some dealings with the place and is aware of its legendary chaos.

‘OK, they don’t control Kivu so they might as well get some money off you for it, right?’

Fang clearly doesn’t want to be drawn into detail on money but nods. ‘Yes, we are talking very significant sums here. China is already the largest investor in the Democratic Republic of Congo with a nine billion dollar deal and we have been able to leverage this to give us more influence.’

Alex nods; he can well imagine what ‘influence’ billions of dollars of hard cash could get you amongst Kinshasa’s famously rapacious elites.

Fang continues to justify the project. ‘Actually the deal is not that unusual if you look around at the land purchases that are going on at the moment. UAE has bought six thousand square miles of southern Sudan, South Africa has bought a huge area of Republic of Congo, Daiwoo Logistics tried to buy half the agricultural land in Madagascar …’

‘Is that the one where the government was overthrown because of it?’

Fang nods, unfazed by Alex’s implied scepticism about his own project. ‘Yes, but that was different. No one in the rest of Congo cares about what happens in Kivu; when you go to Kinshasa there is nothing on the TV or in the papers about it.’

‘Hmm.’ Alex is still not reassured – the more he begins to get to grips with the project the more he can see problems with it.

Fang continues, ‘So your role would be to …’

Alex holds up a hand to stop the tide of enthusiasm. ‘Hang on, who said anything about me actually being involved? This is a huge and very risky project and I am very comfortable at the moment. I’m not looking to take on any new work.’

Fang is momentarily checked and nods. ‘OK, I can see that this is a highly unusual project that will take a while for you to absorb.’ Then he just storms on anyway. ‘The role of the military partner in the consortium would be to neutralise the FDLR.’

Alex feels he has made his point and that he can continue the discussion on a hypothetical basis. ‘The Hutus?’

‘Yes. After they conducted the Rwandan genocide in 1994 against the Tutsis they were driven out by the returning Tutsi army in exile and a million Hutu refugees fled across the border to Kivu.’

‘And have destabilised the province ever since.’

‘Yes. The genocide was twenty years ago now but their leadership have successfully maintained their ideology of Hutu power and indoctrinated a new generation of fighters. Their continued presence means that there are about thirty armed groups in Kivu but the FDLR is the main cause of the instability that breeds the others. Defeat them and the other militias would agree to negotiate; there would be no need for them to exist if a strong authority was established.’

‘So it’s a bit like Israel having the SS sitting on its border?’

‘Yes, the Hutus killed eight hundred thousand civilians in a hundred days with machetes so Rwanda’s government doesn’t feel comfortable with them there. They will be our partners in the consortium.’ Fang’s mind is racing ahead already. ‘How long would it take to set up a Battlegroup operation to deal with them?’

Alex takes a deep breath and considers the issue for a moment. ‘Well, for the sort of air mobile strike warfare you would need, you would want to start the campaign at the beginning of the dry season in May, so next year, that would be thirteen months.’

‘Is that long enough set-up time?’

‘Yes, that would be fine.’

Fang makes a note on his iPad.

Alex continues, ‘But look, President Kagame is safe now, isn’t he? Why does he need to be involved with all this?’ He’s aware of the Rwandan leader’s reputation for ruthless efficiency and running the country with an iron grip.

‘Well, yes and no. The FDLR is not capable of reinvading Rwanda right now but he is still a Tutsi in charge of a country that is eighty-five per cent Hutu. If he were assassinated like the last president in 1994 then the whole thing would start again. He is not the sort of guy who is prepared to have that level of threat right on his border.’

‘So are you saying that the Rwandan military are on board on the project?’

Fang looks momentarily uncomfortable.

‘This is a very delicate area.’ He clears his throat. ‘As I think you know, the Rwandans were involved in atrocities when they were in Kivu that attracted …’

One of the BlackBerries in front of him rings. He cuts off in mid-flow and answers it aggressively in Chinese and then starts listening with occasional grunts. He gets up and walks over to the window and looks out over the rose garden. He suddenly lets forth a tirade of angry instructions, jabbing his free hand into the air.

Joseph wrestles the goat to the ground and holds its head down.

He then faces the dilemma of how to hold both his rifle and the goat. The goat’s string has snapped; he looks back and forth between the two. Should he hitch his rifle on his chest and hold the goat on his shoulders?

Eventually he settles on dragging it by a horn in one hand with his rifle in the other. He sets off down the path in the maize field, back towards the village where he can hear shouting, screaming and gunshots as the hungry FDLR troops set about the civilians.

There is the noise of a struggle going on ahead. As he comes through the maize he sees Lieutenant Karuta wrestling with the woman on the ground. She is putting up a fierce resistance. The goat bleats and Karuta looks up, his face puffy and angry with frustrated lust. Joseph stands and stares at him.

Karuta rolls off the woman and grabs his rifle off the ground and points it at her. She lies on her back looking up at them, eyes wide in terror.

‘Cover her!’ he orders Joseph, who holds his rifle by its pistol grip and the goat in the other hand. She stares at the muzzle just above her face as Karuta pulls out a knife, gets hold of her feet and quickly slits her hamstrings. She screams in agony.

He puts the knife away and straightens his uniform. ‘Come on, she’ll keep for dessert. Let’s have dinner first.’ He walks off down the path towards the village.

When they get back there the lieutenant organises the looting of food and three women are tied to trees. He sends out a patrol under the command of Corporal Habiyakare, another old génocidaire. They are to scout around the small valley to check that the mai-mai have gone. Meanwhile the men slaughter the goat and start cooking it whilst eating foufou and drinking the farmers’ home-brewed beer from gourds.

An hour later the patrol returns, dragging a thirteen-year-old boy with them. He is barefoot, wears shorts and a ragged tee shirt, is crying and looks terrified.

Corporal Habiyakare reports back. ‘Lieutenant Karuta, we have captured a prisoner!’

Karuta’s eyes are already reddened from drinking; he is in a boisterous mood.

‘Bring the prisoner over here, we will interrogate him!’

The boy is dragged into the middle of the village and stripped to his red underpants. His belt is used to tie his elbows behind his back so tightly that his chest sticks out painfully. Karuta sits on a wonky wooden chair in front of him but the boy falls over in tears. The men gather round and laugh and clap as they drink the beer.

The corporal drags the boy to his feet.

‘What is the charge against the prisoner?’ asks the lieutenant.

‘Sir, we found him hiding in the woods, spying on our soldiers. He was armed with this axe.’

‘What have you got to say for yourself?’

The boy sniffles and mutters, ‘I was chopping wood.’

‘You were chopping wood! You think I am a fucking idiot! You are a spy!’

‘No! Not spy!’

‘You were spying on my men!’

‘No, not …’

‘Shut up!’

‘No spy …’

‘Shut up! You are a spy! You work for Rwanda! Look at his feet, he is a Rwandan!’

The crowd pushes forward and looks at the boy’s feet; none of the younger soldiers has ever been to Rwanda so they accept the older génocidaire’s word.

‘Not Rwandan!’ the boy screams in a high-pitched shriek.

‘You will admit it! Beat him!’ The lieutenant gestures to the crowd of men who push the boy to the ground and start kicking him. Others run off and pull supple branches off trees, then run back in, push through the crowd and start whipping the boy.

He curls up in a ball but his hands are behind his back and the blows rain down all over him.

‘You are a Rwandan spy! Confess!’

He cannot speak under the torrent of blows; raw red and pink gashes open up all over his dark skin from the slashing branches.

A soldier pushes the others back and jumps on him, his Wellington boots landing on his hip with a heavy thud. The man springs off laughing and others take running jumps onto the boy.

‘OK, OK!’ Lieutenant Karuta waves his hand: laughing, the men back off.

The boy lies still, covered with dust, his pants wet with urine.

‘OK, come on.’ Karuta shakes his head, grinning at the enthusiasm of his men. ‘On your feet, boy.’

The boy doesn’t move.

‘Get him on his feet.’ He gestures to Corporal Habiyakare, who gets hold of the belt holding his elbows together and yanks him up. The boy stirs and sways on his feet.

‘Over here, heh.’ Karuta points casually to the ground at the edge of the cleared area between two huts.

The boy senses something bad and starts struggling. Habiyakare tries to drag him backwards by the belt but the boy becomes desperate so the corporal kicks his legs out from under him and pulls him along by the belt. The boy shrieks with pain and fear in a high-pitched cracked voice.

Lieutenant Karuta walks ahead with his Kalashnikov and the crowd of men follow, grinning in anticipation.

‘Here!’ Karuta points to a spot on the ground and the corporal throws the boy forward and jumps out of the way.

In one smooth action the lieutenant hefts his assault rifle by its pistol grip so that the weapon is held upright in his right hand. He cocks it with a flourish with his left and then fires a long burst at point-blank range into the boy. His body bounces on the ground and a red mist appears over it briefly.

The men give a huge roar of approval and Karuta turns and brandishes his weapon with a broad grin.

He starts call and response, shouting, ‘Hutu power!’

‘Hutu power!’ the men respond, raising their guns in the air and punching out the words with their fists.

‘Free Rwanda!’

‘Free Rwanda!’

Chapter Four

‘Come on, we’ve got to hurry up.’

Sophie can hear the tetchiness in her voice. Nicolas, as ever, takes it in his stride, nods obediently and pushes the Land Cruiser on faster.

It’s four o’clock and the vaccines in the back are getting warmer by the minute. Their medical technician recommended that they get them to the clinic by late afternoon or else they would be ruined and the whole inoculation event would have to be reorganised. It will be a big waste of money and effort and a loss of face for the charity in the local community if they can’t deliver on their promises. Sophie hates not getting things right. At least the tension is making her forget her carsickness; she sits forward and swigs nervously from her water bottle.

They’re pretty sure they are on the right road. It is winding down the hill into the Bilati valley and they can now see the river far away in the bottom, a fast-flowing upland torrent.

They come down onto a flat saddle of land where another road joins theirs before dipping down into the valley. All around is lush green grassland but up ahead Nicolas spots a checkpoint, a striped pole across the road next to a dilapidated single-storey building.

‘Hmm,’ says Natalie in annoyance. ‘That’s not on the map.’

‘Bugger,’ mutters Sophie.

Yet more hassle. She has spent a lot of time getting the paperwork in place for the journey. Government officials demand documents for everything: they are rarely paid and make their living from bribes. She pulls her document wallet out of the glove box and flicks through it again. The key document, their blue permit à voyager issued by the Chief of Traffic Police in Goma, is on the top, pristine and triple-stamped.

Sophie is keyed up now. One last barrier and they can get there just in time. Several hundred kids live healthier lives – how can you argue with that?

As they drive up towards the barrier they can see government FARDC soldiers standing inside sandbagged positions on either side of it. This is the last outpost of their control before the militia-dominated land beyond and they are very nervy, assault rifles held across their chests and fingers on triggers. They are questioning the driver of a battered Daihatsu minivan, ordering his passengers out and poking around in their woven plastic sacks stuffed with vegetables and bananas.

As they wait in line Sophie asks Nicolas in French, ‘What brigade are they?’

Nicolas peers at their shoulder flashes.

‘Orange is 17th Brigade.’

‘Is that good or bad?’ She knows that the different units have different temperaments depending on which militia they come from and which colonel runs them.

Nicolas replies quietly, ‘Well, they used to be CNDP. They were a good army – Tutsi like me, and they defeated the FARDC whenever they fought them. But then they did a deal with the government and became the 17th Brigade with Congolese officers. After six months they shot up a UN base in protest because their officers had stolen their wages,’ he pauses and then finishes with a shrug and, ‘c’est la magie du Congo.’

Sophie frowns. ‘Great.’

‘Just take it easy, remember the training,’ Natalie says cautiously from the backseat. ‘Don’t make eye contact, keep your voice down, just be sweet. Maybe we’ll have to pay a bribe to get through.’

‘OK, all right!’ Sophie holds up a hand to cut her off. Natalie is really getting on her nerves. ‘We don’t pay for access, it’s our policy.’

Natalie falls silent, the soldiers wave the minivan through and they drive up to the barrier.

Gabriel makes his way past the soldiers and heads down the hillside to Pangi market.

He is torn between turning round and getting out of there immediately and his belief that he can make a killing and return to Eve with a stack of cash. He could use it to try and fix up her hut or buy her something for the baby or maybe get her that sewing machine she wants.

Pangi is a typical Kivu village, a group of palm-leaf and wooden huts in the bottom of a steep valley strung out along the banks of a small, fast-flowing river. All around are rugged hills topped with bright green forest, spotted with patches of white mist; it’s cold and overcast. Meadows and small fields of maize, beans and cassava cut into the woods on the lower slopes.

As he pushes the tshkudu onto the flat ground he keeps his head down but his eyes flick back and forth taking in little details, gauging the atmosphere. It’s ten o’clock and the market is busy, people have been cut off by the FDLR troops for months and have come in from the bush to stock up on food and consumer items. He will have to move fast to find a pitch and set out his wares. All his money is invested in his stock and he has got to get it out in front of his customers quickly before they spend the tiny reserves of cash they have.

A crowd of a couple of hundred people are milling around in a grassy area in the middle of the village, women in their brightly patterned pagne and men in an assortment of jackets and tee shirts, cast-offs from the West. Around the edge of the area women squat behind their goods, carefully laid out on banana leaves on the ground: piles of bush fruits, mangoes, blood oranges, cassava tubers, chickens tied up by the legs and silently awaiting their fate, lumps of bush meat covered in fur and some monkey flesh with little black hands sticking out. Protein is scarce as all the cattle and goats have been killed or driven off by the FDLR. People pick over the goods and pay for it warily with filthy Congolese franc notes.

Gabriel is worried, his eyes and ears taking in danger signals. The scene is unusually quiet, there is none of the usual chatter of a market and there are no children around – normally a village is teeming with them. People’s body language is tense and fearful; no one makes eye contact with each other. Heads constantly flick about looking for trouble, shooting sullen glances at the soldiers. The FDLR may have been driven off but the government FARDC troops are no better. The soldiers swagger around in groups with their rifles, occasionally taking some goods without paying and eyeing up women. The people live in patches like this between outbursts of fighting and flights into the forest. They are angry about their lives but powerless. The atmosphere is one of suppressed violence, like petrol vapour hanging in the air.

Gabriel scans the crowd; the grey sacks hang off his tshkudu, bulging with wares. A pair of soldiers stand at the side of the market with their rifle butts resting on their hips, heads flicking around in a predatory manner.

He is looking for an empty patch of ground to set up his stall. He spent a lot of time making a lightweight folding table from bamboo that he can display his goods on, rather than having them on the ground. He is sure this will draw the customers in.

As he scans around he accidentally catches the eye of one of the soldiers. He ducks his head immediately but the man has seen him and thrusts his jaw forwards aggressively, drawing his finger across his throat in a slitting gesture. Gabriel turns his head and moves away towards the other side of the market.

The soldier follows him and shouts, ‘Hey you! Where is your permit to trade?’

Gabriel freezes, turns and hurriedly goes into his most placatory mode, ducking his head into his shoulders and keeping his eyes averted. ‘Pardon, Monsieur Le Directeur, would you be interested in this small box of cigarettes?’ He holds out the packet.

This is bad; people are turning round and looking at them.

‘I said, where is your permit to trade? Are you deaf?’

The soldier snatches the cigarettes and stuffs them in the front of his combat jacket, his eyes dancing greedily over Gabriel’s sacks.

‘Ah, Monsieur Le Directeur …’

‘Hey, you sound Hunde! Are you Hunde?’

‘Err, no, I …’

‘Hey, he’s Hunde!’ the man calls to the other soldiers in the market and they start moving towards them. A crowd is forming around them, a sea of angry faces straining for an outlet for their misery.

The soldier is right up close to him – he’s big and his face is dark with anger. He shoves Gabriel in the chest. ‘You are Hunde and you come into my market with no permit to trade!’

The crowd gives an angry growl; they are mainly Shi people like the soldier.

‘We are confiscating your property!’ He grabs the handlebars of the tshkudu.

‘Hey! That’s mine!’ This can’t be happening, it’s all his worldly wealth.

The crowd closes around Gabriel, sensing his weakness. A hand shoots out and grabs a sack.

‘Hey, get off, that’s mine!’

Gabriel’s face is contorted in desperation and fear. He is surrounded; he tries to pull the handlebars back from the soldier and pushes a woman grabbing at his goods at the same time. She shrieks and slaps him across the face.

The petrol vapour ignites in a flashover.

The crowd roars and a frenzy breaks out. The soldier brings up the butt of his rifle and smashes it into his face. His nose breaks and blood gushes down his front. He falls backwards and the crowd punch and kick him.

His scooter falls over and there is a mad scramble as people yank open sacks and clamber on top of each other to get at the goods on the ground, shouting, screaming and clawing. Combs, batteries, cigarettes, condoms scatter everywhere. His bamboo display table is smashed to pieces.

Gabriel curls up in a ball on the ground, his arms over his head. He’s in the middle of a tornado, a mad whirl of screaming, kicking, spitting mayhem. Blows rain down on his arms, head, back and legs. Every part of his body is being battered.

Through it all the pain is still mind-shattering, it feels like his face has been smashed into the back of his head.

This is it … I’m going to die.

And then it stops.

The fire burns out as quickly as it started. The mob vent their anger, tear him down to their level of misery and then just as quickly lose interest in him and drift back to looking at the piles of bananas and tomatoes.

One of soldiers puts his heavy black boot on the side of his head and presses it down into the earth. He tastes the mud in his mouth mixed with the metallic tang of his own blood.

‘That will teach you to come into an authorised area without a permit from the Person Responsible! You have learned your lesson today!’

The soldiers pick over the remains of his stock but everything has either been stolen or smashed – someone has even wheeled the tshkudu away. The troops look at Gabriel’s inert body lying in the mud, laugh and wander off, lighting up some of his cigarettes.

He lies still for ten minutes, dazed and winded with broken fingers, busted lips, cracked ribs and a broken nose. People walk past him and carry on chatting. He doesn’t exist. They don’t see weakness: after decades of fighting and lawlessness there is no pity left in Kivu.

Slowly he pulls his hands away from his head and looks out. One eye is closed from a kick and his whole face is swelling from the rifle butt. He sits up, sways and looks around. Painfully, he eases himself up onto one hand and then gets his legs underneath him and creaks upright, his back bent from a kick in the kidneys.

He keeps his eyes down on the ground and shuffles away from Pangi market towards the trail he came in on, his clothes ripped and covered in blood and dirt. It is going to be a long and painful walk back to the refugee camp.

What will he say to Eve when he gets there? He has lost everything. What will she think of him now?

As he shuffles past the soldiers sitting on the log one of them is trying to make his transistor radio work but it has been trodden on. He gives up, throws it on the ground, smashes the casing with the butt of his rifle, pulls the batteries out and pockets them.

They don’t even look at him as he staggers past.

Chapter Five

‘You stink of piss.’

Eve’s older sister, Beatrice, looks at her askance and waves the flies aside that are buzzing around them.

Eve’s pagne is soaked in urine and the wetness has spread up through the cloth and into the waist of her tee shirt. She has no more clean clothes to wear; she has gone through all the ones given to her by her family in the two weeks since the rape. She feels dirty and uncomfortable, she is wet when she lies down to sleep at night and she is wet when she wakes up in the morning. The smell of sour piss is the constant companion in her life now.

Her rape was violent, involving four men and the barrel of a rifle; the metal foresight cut her deeply. It is part of the practice of warfare in Kivu province, an attempt to destroy women and smash the society they traditionally hold together. It has left her with a fistula, a tear in the wall of her vagina into her bladder so that urine constantly seeps out.

Her family look after her but their patience is finite – many victims of rape are rejected by their husbands and thrown out of their houses. She feels lucky that her family has not done that. She is broken and ruined and knows that it is her fault. Eve’s head sinks lower and she shuffles away from Beatrice.

Where is my baby?

The thought recurs in her mind at least once a minute.

The two women are squatting on the ground on a low rise overlooking the refugee camp, rows and rows of palm-leaf shelters, covered in white plastic sheeting in a sea of dark brown mud. It is morning, with a cold, grey overcast sky, there is dew on the ground and people’s breath smokes. They hear the chopping of wood, a babble of voices, the hawking and spitting of old men. It smells of mud, shit and wood smoke from the cooking fires.

People are packed into the view everywhere, clothed in a clashing kaleidoscope of patterns: red, yellow, blue, green, tartans, stripes, every possible combination of brash local styles and Western cast-offs.

Women wash naked children as they stand in battered metal bowls, making them blow their noses into their fingers and then deftly flicking away the snot. Older people stand around in groups with their arms folded and talk quietly, the men dressed in tattered old suit jackets to try to maintain some dignity. They look gloomily at what their lives have become: forced by the endemic warfare from their home villages into the camps, they cannot work and have no control over their destiny.

Everywhere there are kids, running around the shacks, playing, laughing and chattering. For them this is normal life, it’s what they have grown up with. They are dressed in rags, adult tee shirts that are stained and ripped and drag in the mud. All are barefoot, their feet and ankles covered in purple ulcers from cuts that weep pus. It is a noisy, hectic, dirty place to live.

Worst of all though is the fear. They have food from the UNHCR and other NGOs but they have no law and order and the constant uncertainty is etched in deep worry lines on people’s faces. Militia groups can wander in from the bush at any time, just as the Kudu Noir did with Eve.

They have no protection from them. The Congolese army, the FARDC, all are as bad as the militias, which is what they were before they were put into another uniform and then not paid by the central government. As former President Mobutu famously said to those generals who asked him for salaries: ‘You have rifles, why are you asking me for money?’

Rape is another one of the FARDC’s specialities. As for the police, the PNC, they don’t get out this far into the bush; they stay in the towns and anyway are just unpaid bandits who live on bribes.

When the Kudu Noir had finished with her, Eve couldn’t walk. She crawled under the piece of corrugated iron that had been her front door to hide. It did then provide some protection for her; to cover their tracks the Kudu Noir fired a white phosphorous mortar over where they had been – the airburst shell split the night with a white flash and showered burning pieces of felt soaked in the chemical. The ground around her was covered in an impossibly bright light that spewed white smoke. Wherever the pieces touched huts they burst into flame. Peering out from under the metal sheet she could see figures running around lit by orange flames and the banana palm leaves on the edge of the camp twisting in the heat.

Her hut was burnt to cinders and with it all her possessions: a short-handled hoe for tilling her vegetable patch, a plastic basin for washing, a metal cooking pot, two pieces of pagne cloth, a comb, a small piece of soap, some dried cassava, three cooking utensils, a candle stub, a tee shirt. That was it, that was her life.

Eve gets up and moves painfully away from her sister. She thinks about her boyfriend Gabriel: what will he say when he gets back from his trading trip? Will he reject her like her husband?

She rubs her forehead as if she has a terrible headache.

Where is my baby?

Fang stops shouting into his BlackBerry, hangs up and returns to his armchair, facing Alex as if nothing has happened.

He shakes his head. ‘I have a steel shipment on a freighter getting into Port Sudan and the harbour master is a pain in the ass. We pay him too much already and he wants more – we go to Mombasa if he don’t like it.’

Alex feels slightly bemused by this but doesn’t show it. ‘You were saying about the Rwandan involvement in the project?’

‘Yes, it’s delicate because they carried out massacres in Kivu when they invaded it in the main war between 1997 and 2003. So the people there hate them and they can’t send troops back in on a permanent basis. That was a big part of the international treaty at the end of the main war, that all the eight countries involved would get their troops out of Congo.’ He shrugs. ‘There are no good guys in Kivu. So now they have to try this.’

‘So what is “this”?’

‘Well, they have agreed to provide logistical support for the military operation from Rwanda. Because of the international pressure they have been under in the past and their activities in Kivu, the Congolese would not accept them just sending troops into Kivu on a long-term basis. They have been very clear about this in our negotiations.

‘We are envisaging a large Battlegroup operation that cannot just appear in Kivu – it will have to be established in secret in Rwanda first and have a supply chain running through there to the Kenyan ports.’

Alex nods. His military mind is attracted by the idea; it sounds feasible. Suddenly he stops himself.

What the hell are you doing? This is not something you are going to get involved in.

He throws out more objections to try to rubbish the plan.

‘OK, but what about the UN? I mean, they have substantial forces in Kivu and they are not just going to say OK to this sort of deal. It is unprecedented in modern times; the US will go mad on the Security Council. They can’t just let China grab a chunk of the middle of Africa.’

He looks at Fang in exasperation, sure that he has found a way to stop the flow of smooth certainty.

Fang nods to acknowledge the point but continues undaunted.

‘Yes, you are right, there are about five thousand UN troops there but the Congolese government won’t tell the UN in advance of the deal. In terms of the UN troops, they are allowed into a country only at the invitation of that country’s government, they don’t invade places. The Congolese president will simply withdraw their invitation as part of the lease agreement and they will be confined to base and then have to leave. It will just be presented as a fait accompli and there is nothing that the UN or the US will be able to do about it. If a sovereign state decides to lease some of its territory then it can do it.

‘You are right though – they won’t like it. But China and Russia will veto any action that the US want to take through the Security Council. The Americans don’t have any troops anywhere near the area; there is nothing they can do about it. The Congolese President will issue a decree and sign the province over to us and then it is Year Zero for the Republic of Kivu. We’ll have free range to start again and build a new country.’ He shrugs. ‘Although we may keep some UN troops on to continue policing work – we will see how it goes because they could be useful. No one in Kivu is very keen on them. They have been there since 2003 and they haven’t stopped the fighting. They stop it blowing up into an international war but they have been pretty ineffectual at bringing law and order. The province is just a series of fiefdoms run by different local groups.’

At this point Alex gets annoyed. ‘Well OK, but what about the local people? I mean, have you consulted them about this?’

Fang makes a moue but continues, ‘Well, the project is being developed with local political partners, the whole government will be run by them. We have found a local politician without links to any of the militias and he has agreed to be our front man.’ He looks at Alex pointedly and then adds, ‘I mean, you have to be realistic here, Mr Devereux – there really is very little government in Kivu. That’s the problem. There is some control in the areas around the main towns but outside that it is anarchy. There are thousands of rapes there every year. For most people government just doesn’t exist. This operation will establish law and order and give them the hope of a bright economic future.’

Alex sighs: he isn’t getting very far with puncturing the plan. He holds up his hands in acceptance of this.

‘All right, all right, I accept all that. But why does China want to be there in the first place? I mean, if it’s so awful?’

‘Ah, well. You see, you have a very Western view on Africa. Your media portrays it only as a basket case, a land of poverty and starvation or, even worse, a place full of smiley people who dance a lot.’

Alex has to nod ruefully; the shallow and patronising nature of most Western media coverage of African issues is a bugbear for him.

‘But in China, we see Africa as a long-term investment opportunity. The main thing we want in Kivu are minerals. The trade in tin, gold and coltan is worth about two hundred million dollars a year at the moment because it is all artisanal mining, just guys with hammers and spades. But once we get in there and mechanise it, it will be worth billions.

‘The main mineral we want is coltan: columbite-tantalum. We need the tantalum for pinhead capacitors in things like mobile phones, laptops and game consoles.’

Fang grins, thinking about the future. ‘When we get going, the profit margins will be immense! But apart from that, we have big plans to develop the agriculture export trade in Kivu. It’s very fertile and has a great climate. We want to use Goma airport as an export hub for cut flowers, fruit and veg to the Middle East and Europe. We’ll come to rival Kenya pretty quickly and the return on capital will be very attractive.

‘The other big draw for us is that we are building the Chinese corridor from Tanzania to Sudan, up through the middle of Africa to open the whole continent up to trade, and we can’t put the railway through Kivu at the moment because of the fighting so we need to pacify the province first.’ He grins and points at Alex. ‘That’s your job, Mr Devereux.’

Joseph has just raped a woman.

He has never had sex before and is not sure what he thinks about it. His confusion is not helped by the fact that he is drunk on home-brewed beer. He staggers back across the bumpy ground following Lieutenant Karuta towards the firelight. It is dark and the FDLR troops have made a big campfire in the centre of the village to accompany their ongoing celebrations. He can see figures around it silhouetted in the firelight and hear them singing and shouting.

Everyone in the platoon is drunk, they have been eating and drinking all afternoon, stuffing themselves after months hiding out in the deep bush in western Kivu province.

Joseph stumbles along, doing up his trousers. Lieutenant Karuta regards what has just happened as a rite of passage for an FDLR soldier and led the initiation on the woman that he had hamstrung in the maize field in the morning. She had only crawled a few hundred yards by the time they got to her in the evening and it was easy to follow the marks on the ground and the bloodstains smeared on the maize stems. More men are finishing their business behind them.

They rejoin the main group and the men leer and wink at Joseph. He’s the youngest in the platoon and a new recruit. He’s a rather gormless-looking boy, heavily built and with shaggy hair from months in the bush. They giggle and pass him a gourd; he sits down on a log looking dazed, drinks deep and then stares into the bonfire.

After a while, the initiation continues – they blindfold him and make him walk around the fire. The soldiers have fun shouting and pushing him about and he feels scared.

‘Now you do target practice, boy!’

‘What?’

He feels Lieutenant Karuta’s hot, sweaty arm around his shoulder and his beery breath in his face. ‘Come on, you fought well today but you need to learn how to fight better.’

He leads Joseph away from the fire and then a rifle is shoved into his hands. He fumbles around, gets hold of it properly and slips his finger onto the trigger.

‘Whoa, whoa! Careful!’

Men around him laugh.

‘I can’t see.’

‘Doesn’t matter, just point the gun here.’

Karuta’s rough hands guide his so that the rifle is pointing slightly downwards.

‘Now select automatic.’

He clicks the small lever on the casing downward, proud that he can do it blindfold.

‘OK, now give it the magazine.’

Joseph pulls the trigger and thirty bullets blast out.

A howl of laughter goes up around him and Karuta claps him on the back.

‘Heh! Well done, Hutu boy!’

Joseph grins, not sure what he has done, and tentatively pushes up the blindfold.

Sitting on the ground in front of him with her back propped up against a log, her hands tied behind her and a rag stuffed in her mouth is the woman from the maize field. Her body is riddled with bullet holes, her face looks ridiculous with the mouth wedged open with rags but there is an expression of terror frozen in her eyes.

Joseph stares at her aghast.

Karuta carries on laughing. ‘You see how easy it is to kill someone! Come on!’ He throws his arm around him again and wheels him back to the fire where there is another huge cheer as he stumbles in.

Joseph is numb.

‘Hey, come on!’ Karuta shakes him and starts singing a war song to get him over it. He jabs his rifle in the air and shouts at the men to get on their feet. They all jump up, grab their rifles and start jogging on the spot, shaking their rifles in time. Their black faces gleam silver with sweat in the firelight as they sing the words over and over again.

Hutu boy, why are you sitting down?

Kill your enemy!

Kwa! Kwa! Kwa!

They make machete gestures with their free hands.

Hutu boy, why are you sitting down?

Kill your enemy!

Kwa! Kwa! Kwa!

Chapter Six

Sophie’s car pulls up to the barrier and the soldier steps towards her window. He is heavy-set with a fuzz of stubble and a sergeant’s stripes on his uniform.

She winds down her window and he leans his rifle on the ledge.

‘Your papers! Where is your accreditation?’ he says in the aggressive, officious tones of Congolese officials. She smells beer on his breath. As he leans in to take the documents his wrist stretches from his sleeve and she sees he is wearing three gold watches.

Six other soldiers stand around the car. Their faces are impassive but their eyes flick back and forth watching everything, rifles held across their chests, fingers on their triggers.

Usually white NGO workers are regarded as neutral in the multi-sided conflict in the province and only get minor hassle for bribes rather than serious assaults. They float around in white Land Cruisers like some magic tribe with ‘No weapons’ stickers on the windshield (an AK-47 with a red cross over it) proclaiming their neutrality, but Sophie still feels nervous. The edge of the manila folder in her grasp is damp with sweat.

She opens it to show the sergeant. ‘All our papers are in order and we have our permit à voyager here.’ She shows him the document on the top of the stack in the folder.

He grunts in reply and takes it from her.

‘You are in a security zone, this is a military installation here!’ He points at the cement block building with a rusting corrugated iron roof and ochre paint that is flaking off like a skin disease. Bullet holes are dotted across the front of it and there is a larger one where an RPG exploded. Piles of rubbish and plastic bags are caught in the grass and bushes around it. The ground on either side has been used as a latrine by the soldiers and drivers. ‘You must park over there, switch off the engine and deposit the key with the security manager for safekeeping.’ He points to a teenager with a rifle. ‘I will confirm your accreditation with the captain.’

He snatches the folder away from her and marches into the building.

She glances nervously across at Nicolas who calmly reverses the vehicle and parks off the road where the teenager is pointing. He then reluctantly hands over the keys and they sit and wait in tense silence. Sophie gets out and paces up and down, glancing at her watch and the building. Nicolas leans against the jeep and lights a cigarette.

Five minutes later the sergeant comes marching back out with the folder and strides up to her.

‘There is a problem with your documents. You must come and see the captain.’

‘What?’

‘Your permit à voyager is not present, you must see the captain to explain yourself!’

Sophie is incredulous and stares at him. ‘My permit à voyager?’

‘Yes.’

‘It was on the top of the folder.’

‘There is no permit.’