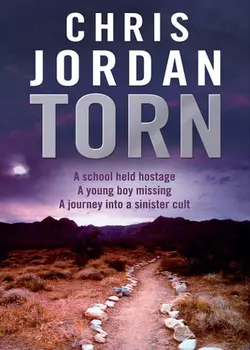

Torn

Chris Jordan

A deranged young man holds over one hundred school children hostage…and he blames the school for what he’s about to do After a tense, thirty-six-hour stand-off, the gym suddenly explodes into flames. Fortunately, all the students have escaped. All, that is, save ten-year-old Noah Corbin. Noah’s mother, Haley, is frantic. Was Noah killed in the explosion? Did he somehow wander away from the scene, hurt and confused? Did someone take him?Haley hires ex-FBI agent Randall Shane because she needs the truth, however devastating the answers may be. As Randall investigates, Haley is forced to admit a dark family secret… one that leads Randall to a desolate area where a powerful, secret cult controls the community. And it’s a secret people will kill to protect.Fast-paced and thrilling, Torn is a mother’s worst fear come to life

CHRIS JORDAN

TORN

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For the brave ones,

Molly & Annie Philbrick

PROLOGUE

The Pinnacle Conklin, Colorado

He awakens with no memory of who he is, or how old he is, or why he should be in this palatial chamber. No, not so much a chamber as a grand hall, with one distant wall formed entirely of high, soaring glass, beyond which magnificent mountains rise from a stark landscape.

Men have gathered at his bedside. Doctors? Attendants? No, they are more like acolytes, for their eyes defer to him in supplication. Is he a prince? A king? A movie star?

He feels like a movie star. The enormous, glass-walled space, with its high curved ceiling melded into shadows, it has the look of a set, something designed for film. But if he’s a movie star—the star of this scene, surely—why can’t he recall his lines? Where have all the words gone?

“Good morning, sir,” says one of the acolytes, looming over the bed. A homely gnome of a man who looks vaguely familiar. “How are you feeling today?”

He searches for the words, wanting to respond, but the only thing readily available is one simple syllable.

“Ha,” he says, suddenly aware of the dryness in his mouth, a thickness in his throat that makes it hard to swallow.

“Bring water!”

A straw appears. He refuses, taking direction from his body, an instinctive recoiling from anything that must pass his lips. And then his mind catches up, slowly unfolding in all its complexity, and with a shudder he remembers that someone is trying to poison him. It is poison that thickens his throat and slows his mind. Poison that traps him in this bed.

He struggles but the poison has made him weak. A needle slips into a vein and the poison drips into him. A subtle, insidious, undetectable toxin that seeps into the cells of his brain, interfering with synaptic response. The bag appears to be harmless saline solution, but it cannot be. The notion that he’s being slowly poisoned is something that he has deduced, rather than proved. The theory is highly probable because it’s the only explanation for his condition: under no other circumstance would men like this—mere drones attending the queen—dare to treat him in this fashion. Unless they had betrayed him.

The drone with the homely face dares to speak for him, as if interpreting the words that clot in his throat.

“Stand clear. He wishes to see the mountains.”

He has issued no such command—what does he care of mountains?—and then the rising sun strikes the peaks in just such a way, as if etching them into the sky, that his labored breathing catches. He knows it is only reflected light glancing off stone, ever so briefly imprinted on his retinas, but the image has the power to bring tears to his eyes.

He remembers, then. For a fleeting moment he regains a sense of who he is. Not a king, exactly, and certainly nothing as insignificant as a mere movie star. He is like the mountain and these lesser beings seek to erode him. They scratch and fuss and block him from the light. They drip their pathetic poisons like rain upon the mountain and like the mountain he will prevail, he will survive, in the most fundamental way, long after they are gone and forgotten.

The drone looks away, as if aware of the greater man’s thoughts and ashamed for his own. He glances at an expensive wristwatch, feigning patience, and when the sunrise ceases to color the mountains he calls for a screen to be drawn around the bed.

Nurses attend to him, changing his catheter, evacuating his bowels. Sponging him down, patting him dry, as if he was some mewling infant and not…whatever he is. He struggles to hold a sense of self. Who is he? Who? A great man in a glass room, beset by lesser species, suffering various indignities. Indignities soon forgotten, absorbed by the scent of baby powder. Beyond that he does not recall.

Nothing holds, nothing stays.

Drip, drip, drip.

“Sir? Your wife is here. Would you like to see her?”

With great effort, fighting up through the silky gauze that swathes his mind, he musters a single “Ha.”

A woman who claims to be his wife floats into view, and if he could laugh, he would. Because it is beyond a bad joke. The woman is old enough to be his mother. Regal, beautifully preserved, expensively coiffed, and obviously very wealthy. But old.

As if he would marry a woman like that! He finds the notion so absurd that it’s hard to hold her words in his mind and sort them into something meaningful.

“Arthur? Can you hear me, darling? Blink if you can understand. I’ve done exactly what you requested. What you spelled out months ago. I followed your instructions precisely, do you understand?” She studies him, then announces triumphantly to the others, “He blinks! He understands!”

He understands only that she must be an elaborate fraud. An aging actress contracted to play a role. She may be in league with the fawning acolyte. Whatever she is, whatever her motives, he cannot trust anything she says.

“You have the best doctors, my darling. The very best in the world. We are not giving up on you, do you understand?” She leans in close, wafting the scent of lilies, and whispers words meant only for him. “You can’t die, Arthur. Not now, not ever. Whatever happens, you must come back to us. One way or another, you must live forever.”

Then she draws away, dabbing at her eyes, and vanishes from his sight line. The scent of lilies. For a moment he knows with absolute conviction who he is and how he has come to be in this place.

He is the one, the Ruler of Rulers, he is all minds in one.

A moment later he begins to drool.

Part I

Humble, New York

1. A Simple, Ordinary Lif

The day before my son’s school exploded, he asked me if heaven has a zip code. We’re having breakfast, me the usual fruit yogurt, Noah his mandatory Cocoa Puffs, cup of ‘puffs’ to one-half cup milk, precisely. He licks his spoon, gives me that wide-eyed mommy-will-know look, and asks the big question.

“Not a real zip code,” he adds, “a pretend zip code, like for Santa. Like for writing a letter to Dad. Just to say hello, let him know we’re okay and everything.”

It’s a strange and wonderful thing, the mind of a ten-year-old child. Last night, as we read our book before bed—the very exciting Stormrider—Noah had asked, out of nowhere, “How we doing, Mom?”

We’d both known exactly what he meant by that—the slow, painful rebuilding of our world—and without missing a beat I’d responded, “We’re doing okay,” and he’d filed it away in his amazing brain and twelve hours later, out pops the idea of writing a letter to his dead father.

“You write it,” I suggest, “I’ll find out about the zip code.”

“Deal,” he says, and grins to himself, mission accomplished.

Then he calmly and methodically finishes his cereal.

My husband, Jed, used to say that Humble, New York, was well named, but only because ‘Hicksville’ was already taken. Humble being a small, one-of-everything town thirty miles outside of Rochester. One convenience store, one barber/beauty shop, one police station, one firehouse, one elementary school. At last count there were more farm animals—mostly dairy cows, cattle, and sheep—than people.

We moved here shortly before Noah was born and my first impression wasn’t exactly positive. I’m a New Jersey girl, a mall rat at heart, and the idea of living upstate in sight of a cornfield wasn’t exactly my dream come true. Postcards are meant to be mailed, not lived in. But Jed was convinced a small town would be safer than Rochester, where he’d just been hired, and which has the usual problems with poverty, drugs, and empty factories, so when he found the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ on the Internet there was no way I could say no.

Not that I ever said no to Jed. What he wanted, I wanted. We agreed that we had to get out of the city, had to make a new life for ourselves, as far away from his crazy family as possible. It was all good, and for a while—nine wonderful years—we lived the American dream, or as near as real people can live it. Not that everything was perfect. Sometimes Jed brought home his job tensions—he was an electrical engineer with a struggling company, lots of pressure there. Sometimes I let my resentment—how did his family situation get to run my life?—overpower my own good sense.

Sure, we squabbled now and then, all couples do, but we never went to bed angry. That was our rule. Arguments had to be settled before we hit the sheets. I’d grown up in a family that fought—my parents divorced when I was in high school—and Jed’s parents had been, to say the least, dysfunctional as human beings, and therefore more than anything we’d both longed for normality. A normal family in a small town, living a simple, ordinary life. The fact that Jed’s family was far from normal no longer mattered, because we were making our own family, our own life, far from them.

Along the way this suburban Jersey girl got pretty good at stripping old plaster, hanging new Sheetrock, painting and wallpapering, the whole nine yards—whatever that means. My old posse would just die if they knew prissy little Haley Corbin had learned how to solder leaky pipes, unclog blocked drains, refinish old kitchen cabinets. With Jed working so hard, and being dispatched as a troubleshooter to distant locations, much of the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ renovation was left to me. I had no choice but to take off my fabulous custom-lacquered fingernail extensions and get to work. This Old House and HGTV became my gurus. I attended every workshop offered at the nearest Home Depot.

I took notes. I paid attention. I learned a thing or two.

My personal triumph, after studying a chapter on home wiring repairs and puzzling over a diagram, was wiring up a three-way switch for a new light in the foyer. Jed was truly amazed by that little adventure. I mean his jaw dropped. Claimed my body had been taken over by alien electricians. I offered to flip his switch, and did, right there on the stairs with Noah fast asleep in his crib.

Life was good. No, life was great. We’d done it. We’d managed to escape from a really bad scene and get a new start. Then it ended, as sudden as a midnight phone call, and the kind of hole it left cannot be plastered over, not ever. The best you can do is push your way through the days, concentrate on being the best mom possible, even if you know in your bones it can never really make up for what’s missing.

Lately Noah seems to be faring better, which is good. He’s not acting out in class quite so much. He’s testing me less, a great relief. That’s the thing about kids. When the impossible bad thing happens, they accept it. Eventually they adapt, and, as the saying goes, ‘get on with their lives.’ One of those clichés that happens to be true. But really, what choice do we have?

“Mom?” says Noah, holding up his wristwatch. A gift from his dad he has never, to my knowledge, taken off.

“Ready?”

“Like five minutes ago. You were noodling, Mom.”

Noah doesn’t approve of me ‘noodling’because he thinks it makes me sad. He may have a point. I feel better when I’m busy, focused in the moment. Not wallowing in daydreams.

Moments later we’re out the door, into the car.

Noah never takes the bus to school, not because he wouldn’t like to—he has made his preference known—but because of the seat belt thing. No seat belts in buses, which drives me nuts. We’re legally required to strap them into car seats until they shave, make sure they wear helmets while riding bikes and boards, but school buses get a pass? What’s that all about?

Jed always thought I overreacted on the subject and maybe he was right, but I can’t help picturing those big yellow buses upside down in a ditch, or in a collision, small bodies hurtling through the air like human cannonballs. So I drive my boy to Humble Elementary School—distance, three point four miles—and see him inside the door with my own eyes. And when school gets out I’ll be right here waiting to pick him up and see that he gets home safely.

A mother can’t be too careful.

2. Waiting For The Voice

Roland Penny watches from behind the filthy windows of his 1988 Chevy van as the children enter the school. The little brats with their backpacks and their enormous shoes. Probably need the big shoes so they don’t tip over from the weight of the backpacks—they look like miniature astronauts stomping around in low gravity.

Strange, because when Roland himself attended this very same school, he, too, had big fat shoes with Velcro fastenings and a Mickey Mouse backpack, which he thought was cool at the time. Now he knows how small and ridiculous he must have looked to the adult world. How pitiful and partially formed—barely human, really. A lifetime ago, long before his mind was successfully reprogrammed with an understanding of the forces that rule the universe. Before he understood the fundamentals. Before he evolved to his present phase.

The cell on his belt vibrates. Very subtle, almost a tickle, but there it is. Incoming, baby. He touches the phone, hears the bright voice in his headset. A rich, persuasive voice that always seems to be perfectly in tune with his harmonic vibrations.

He listens intently. After a moment he responds.

“Yes, sir. I’m in place, on station.”

The Voice, his own personal guidance mechanism, helps him keep focus. Centers him in the vortex. Reveals the secret rules and structures. Shows him the way. The Voice calms him, guides him, persuades him.

The Voice thinks for him, which is a great relief.

“Yes, sir, understood. Wait for the chief. Will do.”

The connection is severed, causing him to wince. It’s a physical sensation, losing connection to The Voice. Like having the blood supply to his brain cut off. But he has trained for this day for the past four months, guided every step of the way, and he knows The Voice will come to him exactly when he needs it, and not a moment before.

Roland Penny sits back in the cracked, leatherette seat of his crappy van and smiles at the thought of the new vehicle he’s going to purchase when this mission is successfully concluded: a brand-new Escalade with all the options! Sweet. For now The Voice tells him that his old van is good cover. Patience. Complete the mission, then savor the reward. The Humble police chief is due at the top of the hour. Doubtless he will be on time, but if not, remain calm. Roland understands that he must not panic, must not deviate from the plan. If he deviates in any way, The Voice will know, and that would be bad.

Very bad.

3. Prime Numbers

Noah loves his homeroom teacher, Mrs. Delancey. Mrs. Delancey is kind and smart and funny. Also, she’s beautiful. Not as beautiful as his mother, of course—Mom is the most beautiful person on the entire planet—but Mrs. Delancey is pretty in a number of interesting ways. Her hair, which she keeps putting back in some sort of elastic retainer thing, the way her dark eyes roll up in amusement when something funny happens, and her nice, fresh vanilla kind of smell, which Noah finds both familiar and reassuring.

The most attractive thing about her, though, is the smart part. At ten years of age Noah Corbin is an uncanny judge of intelligence. He can tell right away if an adult is as smart as he is, and Mrs. Delancey passes. In fourth grade there’s no more baby stuff, no picture books or adding and subtracting puppy dogs and rabbits. They’re learning real science and real math, complicated stuff that teases pleasantly at his brain. Mrs. Delancey isn’t just reading from the textbooks or going through the motions—not like dumb-dumb Ms. Bronson who just about ruined third grade—Mrs. Delancey really understands the concept of factors and multiples and even prime numbers.

In Noah’s mind, prime numbers glow with a special kind of magic. Almost as though they’re alive. Alive not in the human way of being alive, of course, but in the way that certain numbers can have power. When he thinks of, say, 97, it seems to have a pulse. It’s bursting with self-importance—look at me!—as if it knows it can’t be divided. Because dividing by one doesn’t really count. That’s just a trick that makes calculations work, but everybody who understands knows that what makes prime numbers prime is that they can’t be cleanly or perfectly divided. They remain whole, invulnerable, no matter what you try and do to them. Primes are like Superman without the Kryptonite. Which is actually how Mrs. Delancey described them on the very first day of math, totally blowing him away. What an amazing concept!

Yesterday Mrs. Delancey gave him a special tutoring session during recess. Noah had not wanted to go out on the playground at that particular moment—it just didn’t feel right, he couldn’t explain why—and lovely Mrs. Delancey had opened up a high-school-level math book and explained about dihedral primes. Dihedrals are primes that remain prime when read upside down on a calculator. How cool is that! Mrs. Delancey knew all about dihedrals and even more amazing, she knew he’d understand, even though it was really advanced.

Noah, having stowed his backpack, sits at his desk, waiting for the class to be called to order. At the moment mayhem prevails. Children run wild. Not exactly wild, he decides, there is actually a sort of pattern emerging. His classmates are racing counterclockwise around and around the room, a sweaty centrifuge of fourth-grade energy, driven mostly by the Culpepper twins, Robby and Ronny, who have been selling their Ritalin to Derek Deely, a really scary fifth grader who supposedly bit off the finger of a gym instructor in Rochester, where he used to go to school. Necessitating that his entire family escape to Humble, where they’re more or less in hiding. That’s what everybody says.

Noah finds it perfectly believable that a kid would bite off a teacher’s finger. He’s been tempted himself, more than once. Although that was mostly last year, when everybody thought that feeling sorry for him was the way to go. Like Ms. Kinnison always trying to hug him and ‘check on his feelings.’ Which really should be against the law, in Noah’s opinion. Feelings were personal and you weren’t obliged to share them with dim-witted adults who didn’t know the first thing about aerodynamics, momentum effects, or dead fathers.

“Take your seats! Two seconds!”

Mrs. Delancey hasn’t been in the room for a heartbeat and everything changes. Two seconds later every single child has plopped into the correct seat, as if by magic. As if Mrs. Delancey has waved a wand and made it so. While the truly magical thing is that she has no wand—Noah doesn’t believe in magic, not even slightly, not even in books—but has the ability to command their attention.

“Deep breaths everyone,” she instructs, inhaling by way of demonstration. “There. Are we good? Are we calm? Excellent!”

As Mrs. Delancey takes attendance, checking off their names against her master list, Noah decides that she is the living equivalent of a human prime number. Indivisible, invulnerable. Superteacher without the Kryptonite.

4. The Cheese Monster

The amazing thing, given his family background, is how normal Jed turned out. Okay, my late, great husband was brilliant—after he died, his coworkers kept saying he was some kind of genius, the smartest guy in the company—so maybe having a brilliant mind isn’t exactly normal, but in all the usual normal human ways Jed was normal. He loved me unconditionally and I loved him back the same way. We wanted to make a life together, raise children, do all the normal kinds of things that normal people do. And we did, so long as we both shall live.

Not that it wasn’t a challenge. And luck played a role, right from the start. It was luck that we ever met. Blame it on Chili’s. Jed was working his way through Rutgers—he’d already cut all ties with his family—slogging through four-hour shifts at a local Chili’s three days a week and full-time—often twelve hours per shift—on weekends. Forty hours busing tables, thirty hours in lecture halls and labs, another thirty hitting the books—it didn’t leave much time left over for things like sleeping, let alone meeting mall girls from South Orange who just happen to be at a Chili’s celebrating a friend’s birthday, downing way too many Grand Patrón margaritas. Mall girls who get whoopsy drunk and barf in a tub of dirty dishes. Mall girls who are then so humiliated they burst into tears and cry inconsolably.

Well, not inconsolably. I wasn’t so drunk I didn’t have the presence of mind to take the dampened napkins the hunky busboy provided to clean up with, or let him walk me outside so I could get some fresh air. He was so sweet and kind, and so careful not to put his hands on me, even though I could tell he wanted to. And when I came back the next evening, cold sober, to formally apologize, we sat down and had a coffee and by the time we stood up I knew he was the man for me. The very one in the whole wide world. All the other boys—hey, I was a hot little mall girl—all the others were instantly erased, gone as if they’d never existed. My heart beat Jedediah, and it still does.

Jedediah, Jedediah, can’t you hear it?

* * *

After dropping Noah off at school I stop by the Humble Mart Convenience Store for a loaf of bread and some deli items—the selection is limited but of good quality—but mostly to hear the latest gossip being shared by Donald Brewster, the owner/manager. Called ‘Donnie Boy’ by everyone in town, which dates from his days as a high school football hero. Donnie Boy Brewster keeps a glossy team photo up behind the deli counter, blown up to poster size. When the customers mention it, and they do so frequently, Donnie Boy rolls his eyes and chuckles good-humoredly and says who is that kid? What happened to him, eh?

The ‘eh’ being the funny little Canadian echo some of the locals have, from living so close to the border.

Anyhow, Donnie Boy is one of the nice ones, a local kid who made good by staying local. He obviously loves his store, keeps it spiffy clean and well stocked, and he knows everything that’s going on in the little village of Humble and, best part, loves to share. Even with recent immigrants like me.

“Hey, Mrs. Corbin!”

I’ve given up trying to get him to call me Haley. All of his customers are Mister, Missus, or Miz, no exceptions. On the street he’ll call me Haley, but when he’s on the service side of the counter, I remain Mrs. Corbin. Donnie Boy’s rules.

Donnie in his little white butcher’s cap and his long bulbous nose and radar scoop ears, going, “We’ve got that Swiss you like. No pressure.”

“No, no, give me a quarter. It’s Noah’s favorite.”

“Coming right up,” he says, placing the cylinder of cheese in the slicing machine. “Thin, right?”

“Thin but not too thin.”

“Not so thin you can read through it. Got it. D’ja hear about the dump snoozer?”

Why I come here, to hear about mysterious local events like dump snoozing.

“Old Pete Conrad. You know, out Basel Road? The farmhouse with the leaning tower of silo?”

Happily, I am indeed familiar with the ‘leaning tower of silo.’ Nice old farmstead, with the main house kept up and painted and all the other buildings, barns and sheds in a state of disrepair, including a faded blue silo that’s seriously out of plumb. I don’t know Mr. Conrad personally, but have seen him at a distance, fussing at an ancient tractor.

“Pete’s out the dump—excuse me, the recycle center—in that old Ford, and it’s parked there most of the day before anyone notices Pete’s not in the freebie barn, which is where he usually hangs out. They’re about to lock the gate when somebody thinks to check his truck, and there’s Pete, lying on his side, obviously dead.”

“No!”

“That’s what they thought. So they call Emergency Services, the ambulance and crew arrive, everybody is hanging around, reminiscing about the deceased, when all of a sudden Pete sits up and demands to know what’s going on.”

“No!”

“Sound asleep! Said his wife’s snoring kept him awake all night and he came out the dump to catch a few winks. He finds garbage peaceful. Lulled to sleep by the sound of front-end loaders. Which is apparently a whole lot less noisy than Mildred snoring.”

“What a riot,” I say, chuckling.

“Anyhow, that’s my cheesy gossip for the day,” he says, handing the neatly wrapped Swiss across the counter.

“Thanks, Donnie.”

“De nada, Mrs. Corbin. Noah’s in for a treat today, eh?”

“He loves his cheese.”

“No, I meant Chief Gannett. He’s giving his talk to the elementary school kids. For D.A.R.E.?”

“Really? Is there a drug problem in the elementary school?”

“Not that I know of. And Chief Gannett will tell you that’s because he starts early. He gives a wonderful presentation, very entertaining in a this-is-your-brain-on-drugs kind of way. Fire and brimstone but sort of funny, too, you know?”

I leave the Humble Mart with a smile on my face. Fire and brimstone, but sort of funny, too. Perfect. Plus Noah will have a treat when he gets home from school. He likes to take little bites around the holes, pretending they are black holes in the universe and he’s the cheese monster, one of the many nicknames given to him by his doting father.

Ruggle Rat, Crumb Stealer, Noah-doah, The Poopster, The Cheese Monster. When I pick him up at two-thirty, no doubt full of excited, exaggerated stories about the visiting police chief, that will be the highlight of my day. And I wouldn’t have it any other way.

5. Killing Yourself To Live

The van windows are so dirty and pitted it’s hard to see inside, but when the cop car eases into the school parking lot Roland Penny nevertheless slinks down in his seat, to avoid being recognized. Can’t be too careful. The chief knows him, and may recall certain events in Roland’s teen years, and that might prove awkward, or even lethal. Later, once events have been set in motion, there will be time for recognition.

Hey, Q, remember me?

‘Q’ came from ‘cue ball’ because longtime Humble police chief Leo Gannett is bald, completely hairless with alopecia totalis, a condition considered comical by many teenage boys. As funny as being retarded or crippled or, for whatever reason, hideously uncool. Yo, Q! shouted on the street as the cruiser rolled by was guaranteed to get laughs from your buds. Or the derisive snorts of those you wished were your buds.

Whatever. That was over. That was the old Roland, before he emerged from his chrysalis.

Eyeballing the scene in his rearview, Roland watches the familiar figure of the tall, paunchy cop get out of his cruiser, straighten his uniform, and set his lid on his shiny head. Roland knows that big city police officers refer to their regulation hats as ‘lids’because he watches lots of cop shows on TV. Just as they call their uniforms ‘bags,’ supposedly. And how they like to sum up situations by saying things like ‘code four,’ which means ‘everything is okay,’ and ‘code five,’ which means there’s a warrant out on a suspect, and ‘code eight,’ officer calling for help.

Hey, Q! Code eight coming right up, sir! Roland chuckles, amazed by his own ability to think humorously, wittily, at such a critical juncture. Obviously he has developed nerves of steel, strengthened by training and practice. Amazing that when the big moment finally arrives he experiences no uneasiness, no fear, just a pleasant feeling of anticipation. Various tasks to be performed. The next level to be attained. Homage paid to the Profit.

Not the prophet. Never the prophet. The Profit. Crucial difference.

Once the big, bald cop is safely inside the school, Roland emerges from the van. He opens the creaky rear door. His tools are inside, neatly laid out. First to be removed is the small janitorial cart, rattling as it hits the pavement. Inside the cart he places a ragged string mop, intended for show—look, I’m a janitor cart!—and then, very gingerly, a zippered gym bag. The bag is heavy, more than fifty pounds heavy.

Careful, careful, don’t want that little sucker activated before the time comes.

Then, clipped to the inside of the cart rim, just out of sight, a canvas holster, quick release, containing a Glock 17, modified with a reduced-power spring kit for the lightest possible trigger pull. Perfectly legal and not, as the kit warned, for self-defense. Point and shoot without even having to squeeze, that’s how soft the pull—the gun will practically shoot itself.

Before setting off with the cart, Roland places the white earbuds in his ears and activates the iPod. The Voice has instructed him in the use of the iPod, a device that does not respond well to his clumsy, insensitive fingers. Roland prefers buttons, switches, triggers, not wimpy touch screens. Still, he learned, he practiced until he got it right, and it’s not as if he has to scroll through the selections. The only playlist is a comp of Black Sabbath, specifically selected by The Voice. Even in the heaviest throes of his metal phase, Roland was never a Black Sabbath fan. Way too old. Geezers in wigs. Pathetic. His taste tended more toward classic Megadeth tracks, or if he was really twisted, anything by Municipal Waste. Thrash? Don’t mind if I do. The fact is he hasn’t listened seriously to metal since he began to evolve—nearly a year now—but The Voice specified Black Sabbath, and once he has the Ozzified itch of “Killing Yourself to Live” buzzing in his ears it’s okay, strictly as a kind of soundtrack to the sequence of events that have been so painstakingly rehearsed and memorized.

Roland can see the task list in his mind’s eye, clear as day. Start from the top, follow the numbers, execute each task.

1. Gain Access

A wheel spins out of kilter as he pushes the cart across the parking lot, approaching a side door marked Exit Only. Although it is not marked as such, this is where the school takes deliveries. Roland knows this because he worked, ever so briefly, for custodial services. Ring the delivery buzzer and they will come. The buzzer sounds in the coffee room—little more than a closet—and the duty custodian will grudgingly put down his cup, amble out to the door, maybe cadge a smoke from the truck driver making the delivery.

Roland presses the button, waits. Counts to ten, pushes it again. Lazy bastards.

It seems to take forever. His heart pounds like a boxer’s padded glove hitting the canvas bag, but in less than a minute the fitted metal door yawns open.

“Hey, hey,” says Bub Yeaton, his usual salutation.

Roland figured old Bub would be on duty. Not that his presence is crucial to the plan. Any warm body will do, so long as the door opens. But seeing Bub start to squint, as recognition dawns—his watery eyes tracking from the cart to Roland, looking comically quizzical—having Bub in his sights is pretty sweet, all things considered.

“Roland? Hey. Um, what are you doing here?”

“They give me my job back,” says Roland, reaching into the cart.

“I don’t think so,” says Bub warily. “Nobody told me.”

“Check with him,” Roland says, pointing at the empty corridor.

Bub turns to look. Pure instinct—if someone points, you turn to look. And as the elderly custodian turns his head, Roland withdraws an eighteen-inch length of lead-filled iron pipe from the cart and smacks old Bub on the back of the skull, midway up. Exactly as he has rehearsed, practicing on ripe watermelons.

The only sound the custodian makes is a flabby wet thump as he hits the hard rubber tiles of a floor he recently cleaned, waxed, and polished.

2. Subdue Custodian.

Roland turns up the volume and grins to himself as Sabbath bruises his eardrums. So far so good.

6. Eva The Diva

The sun has barely cracked the horizon in Conklin County, Colorado. Dawn oozing up over the eastern edge of the mountains like a tremulous egg yolk charged with blood. Blood is on the mind of Ruler Weems, who has been wide-awake and manning his operations desk for many hours. His work hampered by the fact that he dare not use cell, e-mail, or text in the certain knowledge that his adversaries—mostly notably the Ruler security chief, Bagrat Kavashi—have broken his personal cipher and are monitoring all electronic communication coming from the Bunker.

All of which makes it difficult to marshal his forces, keep them informed. Difficult but not impossible. Back in the day, when Rulers were few, none of those media existed, and yet still he helped build an enterprise whose power and influence extended from Wall Street to the upper echelons of government. And now the entire organization is in grave danger. The county, the village, the institute itself—everything he’s helped forge, build, and create could be destroyed by the willful actions of one woman, in league with her ruthless security chief.

Weems rises from his command post, goes to the window slit, allows himself to be bathed by the slash of sunlight pouring through the two-foot thickness of the concrete bunker. He has many flaws, but physical vanity is not among them—he’s keenly aware of a homeliness that has not improved with age. At sixty-three his hatchet nose, wattled throat, and severe underbite make him look like an old tortoise without a shell. The curvature of his upper spine, naturally drooping shoulders, and dark, deep-set eyes add to the effect.

Long ago he accepted his ugliness, learned how to use it to his advantage. Blessed with a resonant voice, he honed his speaking abilities, perfected his courtly good manners, his natural deference. So that, despite an aspect that can make people cringe at first sight, he tends to make a favorable impression in the long run. Those who offer loyalty are always rewarded. Those who misjudge him do so at their peril.

The woman has misjudged him. But that doesn’t mean she’s not exceedingly dangerous, that the inevitable implosion of her ambition might not be powerful enough to destroy all those around her, the innocent and the guilty alike.

Behind him a vault door slides open.

“Evangeline,” he says without turning.

“You rang, sir?”

His tortoise head swivels, dewlaps quivering.

“That’s a joke, Wendall,” she informs him. “TheAddams Family, I think. That makes you Lurch the butler. Take away his chin, there’s a distinct resemblance.”

Weems happens to know she just turned fifty-five, although you’d never know it. The miracles of nip and tuck, priceless ointments, personal trainers, and a low-calorie diet composed, from what he can see, of little more than twigs. Twigs and malice, for never has he known a woman who harbors so many self-sustaining resentments. Her blood must be acid by now, and her eyes, still large and beautiful and hopelessly compelling despite surgical tightening, have, at a closer examination, the sheen of cold anthracite. Animal eyes peering out through a lovely human mask.

She plops down in his chair, smiling as she takes possession. “Kind a Star Trek thing you’ve got going here,” she observes. “‘Ruler Weems on the bridge, sir!’”

“You seem to have vintage television shows on your mind,” he says. “TV will rot your brain, Eva. It may already have done so, if what I hear is true.”

The smile chills.

“You’ve put us all in danger,” he says. “Terrible, destructive, senseless danger. Are you crazy?”

The smile stays frozen, but the beautiful eyes are amused. “You know what, Wendall?” she says, somehow swiveling her hips and the chair in the same subtle motion. “You need to grow you some gonads. Doing nothing is not a policy. It’s not a strategy. It’s simply doing nothing.”

“He wouldn’t want this.”

“And how would you know what Arthur wants?” she says, taunting. “He hasn’t spoken to you in months.”

“I visit his bedside many times a day,” Weems responds, defensive despite himself. “He speaks to no one. That part of his mind has been damaged.”

“He speaks to me,” she insists.

“Prove it,” he suggests. “Make a digital recording.”

“It’s more a mind-meld kind of thing,” she says with a seductive smile, shaping her recently plumped lips. “I look into his eyes and I know what he wants. I know it as deeply and as surely as if he’s spoken. Arthur is beyond words now. He wants me to act as his voice to the world.”

Weems sighs, puts a hand to his forehead, intending to shield the flash of cold rage in his eyes. “If it was only speaking, that would be one thing,” he says, in his most reasonable voice. “But to hatch this lunatic plot? Endangering God knows how many children? To put us all at risk of arrest? Not to mention what it will do to recruitment and revenues if the truth comes out. It’s insane, Eva. And whatever our differences, I never doubted your sanity.”

“There is no God.”

“What?”

“You just said ‘God knows how many children.’”

“It’s an expression, Eva. Don’t try to change the subject. You reached out, willful and shameless in your ambition, you set loose a man you know is capable of murder, and now terrible things are going to happen in some little town that’s never done us any harm. If your hand is found in this, and surely it will be, we’ll all be destroyed.”

She laughs. “Wendall, don’t be so dramatic. You sound like some old fruit from a daytime drama. ‘Dear me, we shall all of us be destroyed!’ You’re being ridiculous. No one will ever know—Vash will see to that, and when it’s all over, Arthur’s wish will have been carried out.”

“And you’ll take control of the entire organization. You, speaking for Arthur, with the help of that thug Kavashi.”

“Pretty much, yeah.”

“And where do I figure in your great plan? Me and those I represent?”

She shrugs. “You don’t. Retire. Write your own book. Start another enterprise. It makes no difference to me. You and all your friends ride off into the sunset, that’s the bottom line.”

“Which you think will happen because why? Because you want it to?”

“No, Wendall. Because he wants it to.”

Weems shakes his head. They’ve had variations on this conversation before, never settled anything. “You lie so well,” he says, almost with admiration. “If I didn’t know better.”

“When it comes to lying, I stand on the shoulders of giants.”

“Naked ambition,” he says.

She stands up from his custom-built command chair, strokes her hands on her hips playfully. Poisonously. “What are you saying, Wendall? You want to see me naked? Does little Wendy have a woody for pretty wittle Eva the Diva?”

“Get out,” he says.

She gives him an air kiss as she passes him by. “You’ll try and stop me,” she whispers huskily. “You’ll fail.”

7. The Bad Clown

Most of the kids, as they stream into the bleacher seats, contrive to sit with friends. The teachers remain at the aisles, directing traffic, making sure the individual homerooms don’t get blended. Order must be maintained or, as Mrs. Delancey is fond of saying, all heck will break out.

All heck. Noah loves the way she says it—the twinkle in her eye—and also her other favorite phrases like “think smart and you’ll be smart” and “one fish doesn’t make a school,” which she had to explain to some of the slower kids wasn’t about school construction but the way fish—and people—react to other fish and people.

Although most of his classmates find Noah interesting or at least entertaining, he doesn’t have any particular best friends—friends who might ask about personal stuff—and so his goal upon entering the gymnasium is to end up sitting as close as possible to Mrs. Delancey. Preferably a spot, an angle, where she won’t be aware that he’s keeping an eye on her. Because Mrs. Delancey is very careful about not playing favorites, and she’s already giving him special time, what she calls ‘one-on-one’ sessions, when he’s supposed to be out on the playground.

One-on-one. He likes that phrase because he sees it as one raised to the first power, or one times one, or one divided by one, all of which result, amazingly enough, in one. You can’t escape one—no matter where you go, it leads you back. It stands alone but takes care of itself. According to the book, one is not a prime, although Noah hasn’t quite figured out why not, if it is only divisible by itself and by one, which it is. That’s the first definition, right? So why make an exception? Mrs. Delancey explained that once upon a time the number one was considered a prime, but in modern math the primes begin with two, the only even prime number.

Noah intends to pursue this further, the next time he has a chance. The next time he has Mrs. Delancey one-on-one. Right now she’s concentrating on getting her students seated and behaving.

“Bethany! Christopher!”

That’s all it takes, just their names announced with a certain tone, and both kids stop what Mrs. Delancey sometimes calls ‘skylarking.’ Skylarking being okay at recess, even at certain times in class, but never at assembly.

Noah has often been guilty of skylarking, or worse—right here in the gymnasium, in fact—but this morning he vows to behave himself, not wanting to embarrass his homeroom teacher in front of the principal, Mrs. Konrake. Often called Mrs. K. Who stands by the gymnasium doors in her dark mannish suit, her prim, pursed mouth a little pink O, as she oversees the assembly. What she lacks in stature—in heels she’s not that much taller than the biggest fifth grader—Mrs. K makes up in voice power.

If most people have voices like car horns, Mrs. K is a big truck. An 18-wheeler. When she honks, you pull over just to get out of the way. First graders have been known to wet their pants upon being sent to her office. There are even rumors of a spanking machine, something with paddles and a big crank handle. Noah, who has spent some considerable time in Mrs. K’s office, has never seen such a machine and knows from his own experience that when it gets down to one-on-one—those magic numbers again—Mrs. K is actually pretty nice, and her office voice is much less threatening than her hallway voice. As if she has different horns for different places.

When all of the students have been seated, Mrs. K raises her right hand for silence and waits until all one hundred and fifty-seven students have raised their hands to indicate compliance. Aside from the squeaking of the wooden plank seating, the resulting quiet is remarkable. As Noah’s dad used to say, you could hear a germ fart.

“Thank you,” says Mrs. K. “As was explained to you in your homerooms, this morning we have a very special event. Chief Gannett has taken time out of his busy schedule to give us his presentation for the D.A.R.E. program. He’ll be telling you about drug abuse resistance education, and the new Web site for kids, and a lot of very interesting stories from his own experience as a police officer. Let me stress that this is very important and that we are very fortunate to have Chief Gannett with us today. I’m confident that you will give him your full attention, and that when the time comes for questions you’ll be polite and respectful. So without further ado let’s put our hands together and give our guest a great big Humble Elementary welcome!”

The chief has been waiting patiently, looking very somber and formal in his dress uniform. He’s the only man Noah has ever seen who wears white dress gloves. It reminds him of a cartoon character, because in cartoons the hands look like gloves. Thinking of the chief as a variation on SpongeBob or Goofy makes Noah smile. His secret, you’ll-never-guess-why-I’m-laughing smile. He stares into his folded hands, grinning to himself and fighting back a giggle.

The giggle wins when the clown suddenly enters the gymnasium. Noah knows he’s not a real clown—there’s no rubber nose or makeup—but like all of the other children he can’t help but laugh when the man with the little janitorial cart bumps through the gym door. Because at that precise moment the police chief has stepped behind the podium and is testing the microphone by tapping it with one of his white-gloved fingers. Tap, tap, tap. There’s something comical about the contrast between the somber, formally dressed policeman and the disheveled-looking man hurriedly pushing the little cart right out onto the gymnasium floor. The man pushing the cart has a pinched look on his face, as though he’s smelling something bad. A fart maybe. That’s funny. He’s wearing earbuds and bobbing his head to the beat, and that’s funny, too, because no one else can hear the music. Even the mop sticking up from the cart looks comical, as does the fact that one of the cart wheels is spinning wildly around.

The children laugh uproariously.

Noah notes that Mrs. Delancey is smiling, too. So maybe the sudden entrance of the funny man with the cart is part of the D.A.R.E. presentation. That’s how it looks. The puzzled expression on the policeman’s round face appears to be exaggerated, as does Mrs. Konrake’s look of stern consternation. It’s all part of the entertainment, like at a circus or a TV show, with everybody playing his or her part.

The funny man reaching into the funny cart for some sort of funny prop. The nice policeman reacting hastily, awkwardly, fumbling at his belt.

A loud popping noise like a balloon exploding, or a really loud party favor.

Noah is studying Mrs. Delancey when it happens, so at first he has no idea why the shrieks of laughter have turned into shrieks of screaming.

8. A Very Dangerous Word

I’m in the library discussing books with Helen Trefethern when the first siren goes by. Helen runs our little two-room public library with a velvet fist, and she almost always has suggestions on what books Noah and I might enjoy reading together. Stormrider was her idea.

“There’s a bunch more books in that series,” she tells me. “And if he gets sick of spy stories and wants something funny, you might try Hoot. Really smart and sassy, and it will make you laugh out loud. I think Noah will like it—he’s a tough one to pick for—but I’m certain you’ll love it.”

Helen is about my mother’s age—or the age my mom would be were she still alive—and a real Humble native with family roots that extend back a century or more. Unlike most of the local best and brightest who go away to college—in her case Syracuse—she had returned to marry and raise a family. Her husband had passed away a year or so before we lost Jed, so that was another thing that bridged the age difference and made me think of Helen as one of my trusted local friends. As opposed to my old New Jersey posse, who have no idea why I vanished, or where I might have gone.

“So how’s he doing?” she asks. With her it’s not a casual question—she really wants to know.

“Better,” I tell her, with great relief. “New year, new teacher, it’s really made a difference.”

Last year Noah went through this disruptive behavior phase, mostly by acting the clown. They told me—very pointedly—that you can’t teach a classroom of children when they’re howling with laughter because my son has attached erasers to his ears like headphones, or when he is making ghostly noises from inside the air ducts. He always had the tendency to go his own way, right from kindergarten, and for a couple of months after the accident it got worse. Much worse. There were many calls from the principal requesting that I take Noah home, which of course I did. What I would not agree with was the advice offered by the school district’s child psychologist, who thought my son’s behavioral problems could be improved with psychotropic drugs. A cocktail of Ritalin and Paxil. As if grief can be erased by a pill. And even if it can, would you really want to?

The psychologist pushed, but I stood my ground and this year has been better. This year Noah has a crush on his homeroom teacher, and if you think that makes his mother jealous, you’ve no idea how relieved I am that my brilliant little boy has been trying to impress Mrs. Delancey with his good behavior.

It helps that Irene Delancey has a graduate degree in mathematics. No doubt she could be making a lot more money as an actuary, or whatever else math types do when they focus on making money. Instead of chasing the bucks, Irene decided to teach in public schools, this being her first year at Humble. I find her a bit cool and cerebral—she’s one of those unflappable types—but she’s been devoting a lot of extra time and energy to dealing with Noah, and for that I am grateful.

It’s the second siren that finally gets my attention. Two sirens in less than a minute. Must be an accident. Traffic or farm—and around here farm accidents tend to be the most horrific.

Helen says, “Humph,” and ambles over to a window overlooking the street. “Haley? Those were troopers.”

I join her at the window. “Not local cops?”

“State police. Must be serious. Escaped prisoners, maybe?”

The nearest prison is in the next county, fifty miles distant, but we Humble residents worry because four years ago Mildred Peavey was tied up and gagged and had her car stolen by one such escapee. The really tragic part is that Mildred lived alone and it was several days before anybody missed her. By then she’d died of a stroke, still bound and gagged. So the notion of an escaped prisoner is our local boogeyman.

Here comes another siren, a shrill wee-waw wail from a light-flashing ambulance. And this time we’re both able to see it take a left turn onto Academy Road.

“Oh my god,” says Helen, stealing a look at me. “The school.”

By the time I get there, half a dozen state cop cars have arrived, as well as the ambulance. A young trooper with a bright pink face is frantically trying to control the incoming traffic.

Hopeless.

Parents, mostly mothers, are converging from every direction. Most are not bothering to find a parking space, but are abandoning their vehicles and running toward the school, eyes wide with concern, or panic—both.

I’m one of them. Under normal circumstances I’m a pretty calm and rational person. But this is not normal. You can feel it in the air, pick it up from the way the young cops don’t want to look us in the eye. Something terrible has happened.

There’s talk among the moms about panicked phone messages from inside the building. From teachers and also from a few students who apparently ignored the ban on cell phones. Something terrible has happened but no one seems to know what, exactly.

All I know for sure is that Noah doesn’t have a cell phone. Since when do fourth graders need such things?

Since right this very minute.

What kind of mother am I, not foreseeing the need?

“Get them out!” someone shouts.

The crowd surges forward, and me with it.

Uniformed state troopers armed with shotguns are barricading the school entrance.

“Nobody gets in! Stay back!” one of them bellows, his voice cracking.

“What’s happening? What’s wrong?”

That’s me, pleading. Sounding like a frightened ten-year-old, and feeling that way.

The young trooper with the big voice and the baby-blue eyes shakes his head reluctantly, as if he’s under orders not to divulge information. “You’ll have to get back!” he repeats, pointing a finger at me.

Beside me, a furious, tubby little woman ignores the shotguns and the big shoulders barring her way, and attempts to burrow through the troopers, screaming, “They’ve got the kids! They’ve got the kids!”

It’s Becky Bedlow. She has a boy in Noah’s class, a shy little guy, small for his age. And when she says they’vegot the kids in that desperate tone of voice we all know what it means.

Mad bombers, terrorists, Columbine. Every fear we’ve ever had, every nightmare news story, has come careening into our little school. It’s like the entire town is having a panic attack. Mothers are shouting, demanding to be let into the school. The troopers look shocked and maybe a little frightened by the raw passions being expressed—some of it scatological—but refuse to back down.

“Establish a perimeter!” one of the older troopers bellows. From the way they react he’s the big boss, the man in charge.

“What’s happening! Somebody tell us what’s happening!”

The trooper in charge—he’s got a jaw as big as a clenched fist, eyes as pale as gray ice—wades into the crowd, holding up his hands, palms out like a traffic cop.

“Stop it!” he commands. “Stop right there!”

Amazingly enough, he’s rewarded with a cessation of shoving. As the volume lowers, I can hear women weeping. I’m one of them.

“We have a hostage situation!” the big trooper explains. “Man with a gun, barricaded inside the gymnasium with most of the children and teachers.”

“What about the children? What about the kids?”

“As far as we know, no children have been harmed. But if anybody tries to force their way inside, that may change, do you understand? You’ll only make it worse, maybe get somebody killed. So allow us to establish a perimeter. Allow us to do our jobs. Please!”

It takes more persuasion, but within a few minutes he has managed to get us all back behind a flimsy barricade of yellow crime scene tape that has been hastily erected at the far side of the parking lot.

Before I can get my breath I notice a nearly hysterical Meg Frolich waving around her iPhone. Evidently she’s just received an image from her daughter’s cell phone, somewhere inside the school. “Look at this!” she’s screaming, trying to get a beleaguered state trooper’s attention. “They shot Chief Gannett! He’s dead! They killed him! Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god!”

I try to get a glimpse of the tiny image on the iPhone screen, but someone else wrestles it away. Can it be real? Does she have it right? Could the child have misunderstood whatever it is that’s happening inside? Maybe this is all a scary mistake, a group panic kind of deal. But it seems so real, this strange gravity of fear that thickens the air somehow, making it hard to breathe.

Not knowing is killing me. It feels as if icy fingers are clawing at my insides. The way it did when they told me Jed’s plane was down with no survivors. An end-of-the-world sensation, as though I’m falling and falling and it will never stop. The vertigo makes me so dizzy I have to sit down on the grass and cry until my eyes are blind with tears.

Noah, Noah, Noah. I know he’s in there with all the other children, with his teachers and maybe even the principal, but in my head he’s all alone.

9. An Angry Blur

Whatever the cops know, they’re not sharing it with us. Not beyond “man with a gun in the gym.”

Most of what I learn is secondhand at best. An uncertainty that somehow adds to the fear. For example, Megan Frolich had her iPhone seized by the state troopers, with vague promises of getting it back once the images have been downloaded. So we have to rely on what she recalls of the pictures and the accompanying text message from her eleven-year-old daughter.

“I know what she was trying to say,” she insists, her normally pretty eyes looking like overinflated pink balloons. “Bd, that’s ‘bad’ and m-n, that’s ‘man’—s-t has to be ‘shot’ and c-o-p is ‘cop,’ that’s obvious. ‘Bad man shot cop.’ Then c-a-n-t and then m-v, must be ‘can’t move,’ right? And A-f-r-d is ‘afraid.’ I know it is! She repeated it three times. Afraid, afraid, afraid. Bad man shot cop. Can’t move. Afraid, afraid, afraid.”

The accompanying image, as Meg remembers it, is a slightly blurred snapshot of the gymnasium floor, as seen from the stands. On the gym floor is what appears to be a blue plastic tarp. Not lying flat, but jumbled, covering something. And in proximity to the mysterious blue tarp—that very disturbing blue rectangle—Meg recalls a young man who looked, she says, vaguely familiar. Someone local maybe. Meg hadn’t actually seen a gun in the man’s possession—only part of him was on-screen—but she formed the impression he was agitated.

“It was the way he blurred,” she says, trying desperately to grasp whatever meaning had been imbedded in the image. “An angry blur, does that make sense?”

We all agree that it makes perfect sense. An angry blur, a frightened girl. Afraid, afraid, afraid. We’re all afraid, frightened out of our wits, and the sense of anxious dread exuding from the cops—state, local, and county—doesn’t do anything to allay our fears.

We’re waiting, all of us, cops and parents, for whatever comes next. Wrestling with the awful notion that the world as we know it, our little patch of it, may be coming to an end. That from this moment on our lives will be altered. Unbearable. I’m gritting my teeth so hard my jaw aches. All around me desperate parents are calling family and friends, and it occurs to me, with a body-wrenching pang of sorrow, that I have no one to call. Jed is gone. I have no siblings. My mom died in her late fifties of breast cancer. My father, twelve years her senior, passed a year later. My old New Jersey homies have no idea where I am these days and I have to keep it that way. And my new, local friends already know about the situation at the school because by now the whole village has heard about it. Indeed most of the population seems to be on-site, milling around the parking lot and athletic field in a state of shock and anxiety.

This can’t be happening. Bad things happen to good people, I know that, but do bad things keep happening? Isn’t it enough to lose a husband so young? What will I do if something happens to my precious boy?

I somehow force my eyes to focus on the school. Noah’s school. It looks so peaceful. A cheerful little elementary school, carefully constructed of cinder block and brick to keep our children safe. A typical, totally normal public school found anywhere in suburban or small-town America. The main building is one story with a flat roof and plenty of glass to make the classrooms airy and filled with light. The boxy, windowless gymnasium at one end, higher than the rest of the building.

The gymnasium is where the bad thing is happening. Men in various uniforms swarm around the base of the gym. A wiry, long-limbed deputy from the county sheriff’s department begins scaling the wall, inching up a drainpipe like a black spider. As he hunches and turns I catch the white letters emblazoned on his padded vest.

SWAT.

Oh my god.

“Haley?”

It’s my librarian friend Helen, crouching in the grass, reaching out to touch my tear-soaked chin, a look of sorrow and concern on her open face. Next thing, we’re hugging and it’s all I can do not to call her ‘mom,’ the sense of maternal concern is that strong.

“Easy now,” she says, trying to comfort me. “They’ll get them out. It will be okay, you’ll see.”

“You think?” I respond, trying to smile.

“I heard it was Roland Penny. He’s harmless, Haley. Roland would never hurt the children.”

“Who?”

“Roland Penny. Kids used to call him ‘roll of pennies.’ Local boy. The cops have pictures from inside. Cell phone images. They recognize him.”

I want to believe her, that everything will be okay, but something in me can’t. Something in me expects the worst.

“Someone got shot,” I say. “That’s what we heard.”

Helen nods. “They think it was poor Leo Gannett. He’s been chief for years and he’s got a long history with Roland Penny, from when Roland was a kid.”

Just listening to her, my heart starts to slow, approaching something like normal. “How do you know all this?”

Helen smiles, her eyes crinkling with affection. “My sister’s boy, Thomas. He’s with the State Police Emergency Response Team. That’s him over there by the ambulance. Isn’t he a handsome boy? Listen to me, Haley. They’ve got it under control. They know who they’re dealing with. That’s what Thomas says and I believe him.”

“They’re going to start shooting, aren’t they?”

More men with SWAT lettered on their backs, a whole team armed with deadly looking rifles is assembling near one of the emergency exit doors.

“Not unless they have to,” Helen assures me. “They know about all the children, Haley. They won’t risk hurting the kids.”

“What does he want, this crazy man? What does he want?”

Helen shakes her head and sighs.

10. Can You Help Me Occupate My Brain?

Nobody warned him about the smell. Pack a hundred and fifty little kids in a gymnasium, scare the pee out of them, and you get these nasty, eye-watering fumes. Roland has been to the old Yankee Stadium exactly once in his life, on a church-sponsored outing for troubled youths, and the stadium lavatories smelled a lot like this, overflowing with urine and puked-up beer. No beer stink today, so it could be worse. And if the little brats are weeping and wailing—and many of them are—he can’t hear a thing, thanks to the Black Sabbath tracks bruising his eardrums. Turns out to be a good idea, the iPod, providing a useful soundtrack to events that have been ever so carefully orchestrated. Helps him concentrate. Leave the earth to Satan and his knaves. Yeah. Go Ozzy.

As to the plan, so carefully conceived by The Voice, so far so good. The essential action, taking out the cue-ball cop, had proved even easier than Roland had imagined. He’s destroyed the man thousands of times in his imagination, sometimes roasting him alive, but this had been as simple as raising the weapon and applying the slightest pressure on the customized trigger. What with the music pumping through his earbuds, he never even heard the pop. And old cue ball went down like a puppet with cut strings. Roland was expecting him to be blown backward, like in the movies, but the reality was he simply dropped where he stood, dead before he hit the floor.

True, there was a disturbing amount of blood, but Roland managed not to obsess on that, and whipped the blue tarp out of his handy little cart, covering both the body and the blood, exactly as he had been instructed. Out of sight, out of mind. Besides, it felt really good, knowing his old nemesis was no longer in the world. And when he saw the stricken looks of shock and horror coming from all those little faces in the stands, and the teachers recoiling in fear, man, he got pumped. What I’m talkin’ about, dude! Carpe diem like the book said. Seize the day. Make it your own. Establish who you are and what you desire. Ignore all contrary voices, tune them out, find your inner voice and concentrate on what you want. Visualize it. Make it so.

And he’d done it, he’d made it so. Told the stubby little principal to take the chains and padlocks he’d provided. She had followed his command, chained the exit doors, and then when a glimpse of defiance flashed in her beady little eyes, he promptly cuffed her with the late cue ball’s own official cop cuffs and commanded that she sit down, shut up, or get tarped. After that she was compliant, didn’t have the courage to look him in the eye.

“Listen up, toadstools! Anybody moves, I open fire, okay? And when the clip is empty, I detonate the bomb! Did I mention the bomb? No? Well, I got a bomb. And it’s really cool. Fifty pounds of C-4, which is enough to turn you all into jelly beans!”

Roland is unaware that with the music blasting, he’s shouting in a way that makes him sound like a raving madman. A babbling, out-of-control psycho. But that makes him all the more effective. None of his captives doubt that he will kill again at the slightest provocation.

“So stay in your seats!” he shouts. “Don’t move! You want to use your phones, make a few calls, go ahead! Let ’em know I got it under control!”

He raises his other hand, showing off the Sony TV remote he has cleverly modified, guided by The Voice. “See this! It’s a detonator! Tell all your friends! Press this button, we all go boom!”

Roland and The Voice had debated the cell phone issue when the plan was being formulated. At first Roland thought he should confiscate all the phones, take control of communication, but The Voice reminded him how difficult that might be. Many of the teachers would have cells, a lot of the kids might have them stashed, and texting made it easy to send messages without being obvious. One man couldn’t search all those kids and teachers, not by himself, and the whole purpose of the plan was that he do it alone, his own personal one-man show. Thus proving that he was ready to move on to the next level.

So the idea was, embrace the captives’ ability to communicate with the outside world. No need for Roland to use his own cell, or share his own identifying vocal patterns with the authorities. Let little Kelly or Timmy make the call. That way he can concentrate on managing the situation, not get distracted by some dippy hostage negotiator. Excuse me, Mr. Penny, would you kindly step intoour telescopic sights? No way. The Voice was right. Let the communication flow. Concentrate on the plan. Execute.

And whatever you do, don’t look at the tarp, or what seems to be flowing out from under it.

“People think I’m insane because I’m drowning all the time!” he shouts, unaware that he’s singing along with the heavy-metal lyrics pounding into his head. “Can you help me occupate my brain?” he screams. “Oh yeah!”

He’s right. Everybody in the gymnasium, students and teachers, and staff, they all think he’s totally insane.

11. The Calculus Of Heaven

Noah is pretty sure what it means to be turned into jelly beans. That’s what happens when a bomb goes off. You get blown into pieces no bigger than jelly beans. Not that he intends to explain it to the other kids, many of whom are confused about what the crazy bad man said. Jelly beans? Is the bad man going to give us candy?

Noah is not even slightly confused by what has happened. He gets it. He understands that none of this is pretend. The bad man is not a funny clown; he’s a killer. It’s all very real. The bad man really shot the white-gloved policeman and then quickly covered the body with a blue tarp. The bad man made Mrs. K lock the exit doors, weaving bright new chains through the push bars. The bad man keeps waving his ugly black gun, alternating between making threats and singing along with his stupid iPod.

One other thing Noah understands. The crazy bad man is getting worse, more crazy. He’s shouting things about Satan being inside his brain. He’s raging about cell phones, and the importance of letting the whole world know what’s going on, and some of the other kids are madly texting, as if the act of communicating what the bad man says will save them. Noah isn’t so sure about that. He thinks the bad man might really do it. He might press the button and turn them all into sticky red jelly beans. Then all of them would go to heaven—or not—Noah hasn’t decided yet about heaven, whether it really exists or whether it’s like Santa Claus, to make people feel better. He likes to think of his father as being in heaven, but if his dad was really in a place like that, wouldn’t he find some way to let his son know? Unless there are rules, and Noah supposes there might be, rules about not talking to those left behind. Rules as complicated and hard as calculus. He knows calculus exists because Mrs. Delancey has a book about it in her desk and Noah sneaked a look, and to his surprise could not immediately understand the contents. Whatever it is, calculus is more than arithmetic, more than algebra, more than geometry—it’s all of them mashed together, making something completely different, but at the same time tantalizingly familiar. Differentials? What are those? The formulas and symbols looked intriguing, as if they might contain all the answers about everything there is to know, including whether heaven really exists.

More than anything else, Noah wants to live long enough to understand calculus, and have his mom read him a bedtime story, and get up and have breakfast, and go to school as if nothing bad had ever happened. So he’s thinking really hard about what to do. How to get away without being turned into jelly beans, or doing something that will turn Mrs. Delancey into jelly beans.

Meanwhile the bad man rages at them.

“I see a black moon rising and it’s calling out my name!” he shouts, bobbing his head and pretending to strum an air guitar like on Guitar Hero. Then the bad man seems to correct himself, like a funny skip on a DVD. “Text the world, I want to get off! They’ll be coming round the mountain, boys and girls!” Then, shouting so loud he spits: “Don’t move! I swear to the prophet, I WILL BLOW THIS BITCH!”

Now he’s waving around the detonator button, pointing at it with his gun as he grins, showing all of his small yellow teeth. He holds the pose for a few beats, as if he knows that his picture is being captured on cells.

“Noah?”

Somehow Mrs. Delancey has slipped along the bench and is beside him, a comforting presence, a still point in the chaos of fear and confusion that radiates from everybody in the gym, including the bad man. She pitches her voice for him alone, her mouth a mere inch from his ear. “I want you to go and hide,” she whispers. “Hide in the air duct, Noah, like you did before. Can you do that for me?”

“I’m scared to move.”

She hugs him. At this moment, in this place, she smells like home. Like flowers and bread and home. And so he doesn’t want to leave her side. Doesn’t want to risk doing something wrong. Something that will make the bad man press his crazy button and send them all to heaven.

“Listen to me, Noah,” Mrs. Delancey says in her beautiful, lilting voice. “He’s not focused on anything but himself. All you have to do, slip down through the space between the benches, like you did before. He won’t be able to see you. Hide, Noah, please? For me? Hide in the air ducts, okay? I’ll come to find you when all this is over.”

“You promise?”

“I promise. Now go.”

As the bad man raises his fist, shaking the detonator and screaming something about children of the grave, Noah slips under the bench, through the narrow gap, into the stands. Into the familiar geometry of the supports and trusses that hold up the benches. The last time he did this, slipped away into the space under the stands during an assembly, he got in a lot of trouble. Mrs. K was really upset with him then, told him he might have been injured and nobody would have known where to look for him. Noah thought it was pretty funny, the way he’d run along under the benches, tugging at dangling feet to make the girls giggle and shriek. Mrs. K didn’t think it was funny at all and his mom had to come to the school and take him home. But that was last year. Things were different last year. He was younger then and he didn’t have Mrs. Delancey. Mrs. Delancey who understands him, and wants to save him.

Hiding in the air ducts sounds like a really good idea. It will be snug and cozy in there. Noah discovered the attractions of the ducts last year, when he brought an adjustable screwdriver to school, removed a metal grate, and then shinnied around on his tummy, just as he’d seen in the movies, where air ducts were often a means of secret escape. The big difference was that the ducts at school were way too small for anybody even slightly larger than he was—Matt Damon wouldn’t ever fit, no way!—and they didn’t really go much of anywhere useful. Retreat a few feet and you ran into a fan, baffle, or filter system. So basically they were good for hiding in the classroom and making spooky echo noises to amuse your classmates. This is the booger monster and I’m comingto get you ooh ooh ooh! Even Mrs. K couldn’t keep a straight face when she marched him to the office. Booger monster? she had said, breaking up. Where do you get this stuff?

What Noah knew from his previous experience, and what Mrs. Delancey obviously knew, as well—there were a couple of fairly large duct openings under the stands. Part of the circulation system for the sock-smelling gym. He hadn’t attempted to access the ducts at the time—it was too much fun tugging on dangling feet—but once he climbs down to the floor beneath the stands—there’s pee dripping down from the benches, ick!—he makes a beeline for the wall, locates one of the ducts.

The duct is, like all the others, covered by a metal grate. The problem is, he no longer carries the adjustable screwdriver. Because of his previous ‘behavioral problems,’ the screwdriver set has been forbidden. Too much like a weapon, they said. He might poke out somebody’s eye. To which his mom had said all he needs for that is a pencil. Wrong answer. For a whole week they didn’t let him have pencils and he had to fill in the answers with a crayon, like a baby! And his mom was so mad she cried.

Noah has some change in his pockets, but none of the coins fits the special slots on the screws that hold the metal grate in place. He’s hurrying because the crazy bad man is shouting again. Scary shouting that doesn’t make sense.

“Don’t mess with success! Heed the prophet! I bite the heads off bats! Leave the earth to Satan and his slaves! Into the void, boys and girls! Into the void!”

A moment later there are gunshots, and children screaming. Teachers, too. Is that Mrs. Delancey? Has something happened to Mrs. Delancey? Has she been punished for helping him escape?

Fighting his fear, Noah creeps to the front edge of the gymnasium seating on his hands and knees and looks out through a slot between the benches.

The crazy man is running around in circles, firing his gun straight up in the air. He looks as frightened as the screaming children. Smoke is pouring out of his little janitor cart. Huge amounts of thick black smoke, billowing over the floor and into the stands.

The crazy man kicks at the cart as if he wants the smoke to stop, as if he doesn’t understand what’s going on. That’s the really weird thing. He looks genuinely puzzled. He looks scared.

When the smoke begins to filter under the stands, enough to make him cough and make his eyes sting, Noah retreats back to the air duct.

Stupid people taking away his screwdriver! He hooks his fingers into the metal grate and yanks with all his might.

To his surprise the grate swings open on its hinges. He climbs inside just as the whole building begins to shake and the air goes black with smoke.

12. Out Of The Smoke

When Jed proposed, he sealed the deal with his grandmother’s wedding ring. A thin band of gold set with a diamond about as big as a grain of sand. But if I’d ever had any doubts—and who doesn’t have a few?—that little old ring blew them away. A man you love more than anything, more than you can possibly describe, he drops to one knee with tears of joy in his gorgeous eyes, and he offers you not only a place in his heart, but a place in his most precious memories.

A girl just has to say yes. Actually I didn’t stop saying yes for about half an hour, and by then we were in bed, and, come to think of it, I was still saying yes. But that’s private. You don’t need to know.

What really matters was that Jed trusted me without reservation, holding nothing back. The proposal of marriage came with an escape clause. He was going to tell me a secret, a terrible secret, and if I wanted to back out, forget the whole thing, he’d understand.

And that’s the thing about Jedediah; he really would have understood. Because it wasn’t just the secret, it was what it meant about our future together. Marriage would mean leaving everything behind—friends, family—and making a new life.

First thing I asked him, joking: you mean like the witness protection program?

He’d nodded gravely and said yes, a little bit like that, except we’ll be totally on our own. No U.S. Marshals to protect us. Nobody to give us new identities or settle us into a new life. It will all be up to us alone.

So who did you kill? I asked.

He’d rolled his eyes at that—he got a kick out of what he called my ‘smart-mouth jokes’—and said, it’s nothing I did, it’s who I am. Who my father is.

So who’s your daddy? Tony Soprano?

And that’s when he told me who his father was, and what that meant, and after he was done, as he waited gravely for my answer, I kissed his eyes and said, didn’t you hear me the first ten thousand times? The answer is yes.

Saint Francis of Hoboken, patron saint of New Jersey, he said, regrets, I’ve had a few. Not me. Even after all we went through, I have no regrets. Not about saying yes. Not about loving Jed. Not about the life we lived, the baby we made, the time we had together. What would I be if I’d never met Jedediah? Another person, surely. Not Noah’s mother, that’s for sure.

And if I’d known Jed would be gone in twelve years, snatched away in one terrible instant? If instead of an unforeseeable fatal accident he’d had, say, a disease that would shorten his lifespan. Something we knew about from the start. Would I have said no and saved myself the loss, the pain? No, no, no. No matter how you make the calculation—and all of this has raced through my mind a million times, in every possible variation—I would never choose to erase those years. Would never, ever wish I had taken another path. You can’t truly love someone and make a choice based on how long he might live. Love isn’t something that can be rated by ConsumerReports—go with the Maytag or whatever, because it will last the longest with fewest repairs. That’s not how it works. We like to think we’re rational creatures but we’re not. And besides, when you’re twenty, twelve years seems like an eternity. It seems, indeed, like a lifetime well worth having.

And it was, it was. I swear on my wedding ring. So forgive me if I admit that when the smoke starts pouring from the building, my first reaction is that I’d rather die than endure this again. I simply can’t do it. If Noah doesn’t come out of that gym alive, I want my heart to stop beating. I want to go wherever he’s gone.