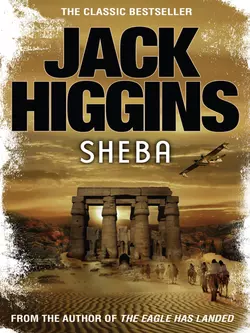

Sheba

Jack Higgins

The Lost Temple of Sheba is not just a biblical legend. A German archaeologist has found it. The Nazis have claimed it. And one American explorer has stumbled upon their secret - a plot that could change the course of World War II.The year is 1939. An American archaeologist named Gavin Kane is asked to help a woman search for her missing husband.When Kane follows the man’s trail into the ruthless desert of Southern Arabia he makes two shocking discoveries. One is the legendary Temple of Sheba, an ancient world as fantastic as King Solomon’s Mines. The other is a band of Nazi soldiers who plan to turn the sacred landmark into Hitler’s secret stronghold…This electrifying thriller is Jack Higgins’ most exciting novel of World War II intrigue since The Eagle has Landed.

Jack Higgins

Sheba

Contents

Cover (#ulink_d6b04aa8-66ed-59d4-821e-993c8774440e)

Title Page

Publisher’s Note

Map

Berlin

March 1939

1

As rain drifted across Berlin in a great curtain on…

2

On Wednesday morning Canaris, after sleeping once again on the…

Dahrein

August 1939

3

The wind, blowing across the Gulf from Africa, still carried…

4

They came into Dahrein in the early afternoon. As the…

5

They didn’t talk much on the way to the hotel.

6

He moved along the corridor and as he reached the…

7

The hotel was ablaze with lights, and the foyer was…

8

The fishing boats were slipping out through the harbour entrance…

9

Kane gave a long, shuddering sigh and wiped sweat from…

10

Jamal gently cleared loose sand away from the base of…

11

It was almost noon when the two guards came to…

12

The moon had risen over the rim of the gorge…

13

The cave was in complete darkness and Kane took out…

14

They entered a large chamber which was about three feet…

15

They left an hour later on the three camels Jamal…

16

A thorough search of the camp produced plenty of food,…

17

He opened his eyes slowly. For a moment his mind…

18

It was quiet in the garden and a slight breeze…

About the Author

Other Books by Jack Higgins

Copyright

About the Publisher

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

SHEBA was first published in the UK as Seven Pillars of Hell by Abelard-Schuman in 1963. It was then rewritten and published by Michael Joseph in 1994 and has been out of print for several years.

In 2012, it seemed to the author and his publishers that it was a pity to leave such a thrilling story languishing on his shelves. So we are delighted to be able to bring back Sheba for the pleasure of the vast majority of us who never had a chance to read the earlier editions.

In 24 BC the Roman General, Aelius Gallus, tried to conquer Southern Arabia and succeeded only in losing most of his army in the awesome region known as the Empty Quarter, the Rubh al Khali. Amongst the survivors was a Greek adventurer named Alexias, centurion in the Tenth Legion, who walked out of the desert carrying with him a secret of the ancient world as astonishing as King Solomon’s Mines, a secret that was lost for two thousand years. Until …

Map

Berlin

1

As rain drifted across Berlin in a great curtain on the final evening of March a black Mercedes limousine moved along Wilhelmstrasse towards the new Reich Chancellery which had only opened in January. Hitler had given them a year to complete the project. His orders had been obeyed with two weeks to spare. Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Chief of Military Intelligence, the Abwehr, leaned forward and wound down the window so that he could obtain a better view.

He shook his head. ‘Incredible. Do you realize, Hans, that the frontage on Voss-Strasse alone is a quarter of a mile long.’

The young man who sat next to him was his aide, a Luftwaffe captain named Hans Ritter. He had an Iron Cross Second and First Class and was handsome enough until he turned his head and the dreadful burn scar was visible on his right cheek; and there was a walking stick on the floor at his feet, the unfortunate result of his having been shot down by an American volunteer pilot while flying with the German Condor Legion in the Spanish Civil War.

‘With all those pillars, Herr Admiral, the marble, it’s more like some marvel of the ancient world.’

‘Instead of a symbol of the new order?’ Canaris shrugged and wound up the window. ‘Everything passes, Hans, even the Third Reich although our beloved Führer has given us a thousand years.’ He took a cigarette from his case and Ritter gave him a light, as always slightly alarmed at the mocking in the older man’s voice.

‘As you say, Herr Admiral.’

‘Yes, it’s a bizarre thought, isn’t it? One day people could be wandering around what’s left of the Chancellery, tourists, just like they inspect the ruins of the Temple of Luxor in Egypt saying: “I wonder what they were like?”’

Ritter was thoroughly uncomfortable now as the Mercedes drove through the gilded gates into a court of honour and moved towards the steps leading up to the massive entrance. ‘If the Herr Admiral could give me an idea of why we’ve been called.’

‘I haven’t the slightest notion and it’s me he wants to see, not you, Hans. I simply want you on hand if anything unusual turns up.’

‘Shall I wait in the car?’ Ritter asked as they pulled up at the bottom of the steps.

‘No, you can wait in reception. Much more comfortable and you’ll be able to feast on the new art forms of the Third Reich. Vulgar, but sustaining.’

The Kriegsmarine Petty Officer who was his driver ran round to open the door. Canaris got out and waited courteously for Ritter, who had considerably more difficulty. His left leg was false from the knee down, but once on his feet he moved quite well with the aid of his stick and they went up the steps together.

The SS guards were troops of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler and wore black dress uniform and full white leather harness. They saluted smartly as Canaris and Ritter passed inside. The hall was truly remarkable with mosaic floor, doors seventeen feet high and great eagles carrying swastikas in their claws. A young Hauptsturm-führer in dress uniform sat at a gold desk, two orderlies standing behind. He jumped to his feet.

‘Herr Admiral. The Führer has asked for you twice.’

‘My dear Hoffer, I didn’t get his summons until half an hour ago,’ Canaris said. ‘Not that that will do me any good. This is my aide, Captain Ritter. Look after him for me.’

‘Of course, Herr Admiral.’ Hoffer nodded to one of the orderlies. ‘Take the Herr Admiral to the Führer’s reception suite.’

The orderly set off at a sharp pace and Canaris went after him. Hoffer came round the desk and said to Ritter, ‘Spain?’

‘Yes.’ Ritter tapped his false foot. ‘I could still fly, but they won’t let me.’

‘What a pity,’ Hoffer said and led him over to the seating area. ‘You’ll miss the big show.’

‘You think it will come?’ Ritter asked, easing himself down and taking out his cigarette case.

‘Don’t you? And by the way, no smoking. Führer’s express order.’

‘Damn!’ Ritter said, for his pain was constant and cigarettes helped.

‘Sorry,’ Hoffer said sympathetically. ‘But coffee we do have and it’s the best.’

He turned, went to his desk and picked up the phone.

When the guard opened the enormous door to Hitler’s study, Canaris was surprised at the number of people in the room. There were the three commanders-in-chief, Goering for the Luftwaffe, Brauchitsch for the Army and Raeder for the Kriegsmarine. There was Himmler, von Ribbentrop, generals like Jodl, Keitel and Halder. There was a heavy silence and heads turned as Canaris entered.

‘Now that the Admiral has deigned to join us we can begin,’ Hitler said; ‘and I will be brief. As you know the British today gave the Poles an unconditional guarantee of their full support in the event of war.’

Goering said. ‘Will the French follow, my Führer?’

‘Undoubtedly,’ Hitler told him. ‘But they will do nothing when it comes to the crunch.’

‘You mean, invade Poland?’ Halder, who was Chief of Staff at OKW, said. ‘What about the Russians?’

‘They won’t interfere. Let us say there are negotiations in hand and leave it at that. So, gentlemen, my will is fixed in this matter. You will prepare Case White, the invasion of Poland on September the 1st.’

There were shocked gasps. ‘But my Führer, that only gives us six months,’ Colonel-General von Brauchitsch protested.

‘Ample time,’ Hitler told him. ‘If there are those who disagree, speak now.’ There was a profound silence. ‘Good, then get to work, gentlemen. You may all leave except for you, Herr Admiral.’

They all filed out and Canaris stood there waiting while Hitler looked out of the window at the rain. Finally he turned. ‘The British and the French will declare war, but they won’t do anything. Do you agree?’

‘Absolutely,’ Canaris said.

‘We smash Poland, wrap things up in a few weeks. Once it’s done, what is the point of the British and French continuing? They’ll sue for peace.’

‘And if not?’

Hitler shrugged. ‘Then I’ll have Case Yellow implemented. We’ll invade Belgium, Holland, France and drive the English into the sea. They’ll come to their senses then. After all, they are not our natural enemies.’

‘I agree,’ Canaris said.

‘Having said that, it occurs to me that I should demonstrate to our English friends as soon as possible that I do mean business.’

Canaris cleared his throat. ‘Exactly what do you have in mind, my Führer?’

Hitler gestured towards the huge map of the world that hung on the far wall. ‘Come over here, Herr Admiral, and let me show you.’

When Canaris returned to the reception hall at the Chancellery an hour later, Hoffer was seated behind his desk with the two orderlies. There was no sign of Ritter. The SS Captain stood up and came to greet him.

‘Herr Admiral.’

‘My aide?’ Canaris asked.

‘Hauptman Ritter was badly in need of a smoke. He went back to your car.’

‘My thanks,’ Canaris said. ‘I’ll find my own way.’

He went out of the huge doors and stood at the top of the steps, buttoning his greatcoat, looking out at the rain. He went down the steps and had the rear door of the limousine open before his driver realized what was happening, and climbed in beside Ritter.

‘My office,’ he called to the driver, then closed the glass partition.

Ritter started to stub out his cigarette as they drove away, and Canaris sat back. ‘Never mind. Just give me one of those things. I need it.’

Ritter got his cigarette case out and offered a light. ‘Is everything all right, Herr Admiral? I saw them all leave. I was worried.’

‘The Führer, Hans, gave us his personal order to invade Poland on September the 1st.’

‘My God,’ Ritter said. ‘Case White.’

‘Exactly. He has been negotiating with the Russians, who will do a deal. They’ll let us get on with it in return for a slice of eastern Poland.’

‘And the British?’

‘Oh, they’ll declare war and I’m sure the French will go along. The Führer, however, is convinced they will do nothing on the Western Front and for once I agree. They’ll sit there while we wrap up Poland, and his feeling is that once it’s an accomplished fact, we can all get round the negotiating table and get back to the status quo. Britain, as he informed us, is not our natural enemy.’

‘Do you agree, Herr Admiral?’

‘He’s right enough there, but the British are a stubborn lot, Hans, and Chamberlain is not popular. Since Munich his own people despise him.’ Canaris stubbed out his cigarette. ‘If there was a change at the top, Churchill for example …’ He shrugged. ‘Who knows?’

‘And what would we do?’

‘Implement Case Yellow. Invade the Low Countries and France and drive whatever army the British had brought across the channel into the sea.’

There was a pause before Ritter said, ‘Could this be done?’

‘I think so, Hans, as long as the Americans don’t interfere. Under the Führer’s inspired leadership we have reoccupied the Rhineland, absorbed Austria and Czechoslovakia plus one or two bits and pieces. I have no doubt we’ll win in Poland.’

‘But afterwards, Herr Admiral? The French, the British?’

‘Ah, well now we come down to why the Führer kept me back when everyone else left.’

‘A special project, Herr Admiral?’

‘You could say that. He wants us to blow up the Suez Canal on the 1st of September, the day we invade Poland.’

Ritter, in the act of snapping his cigarette case open, said, ‘Good God!’

Canaris took the case from him and helped himself. ‘He got the idea from this Colonel Rommel who commanded the Führer’s escort battalion for the occupation of the Sudetenland. He thinks highly of Colonel Rommel and with reason and there is a certain mad logic to the idea. I mean, the Suez Canal is the direct link to the British Empire. Cut it and all shipping to India, the Far East and Australia would have to go by way of Africa and the Cape of Good Hope. The military implications speak for themselves.’

‘But Herr Admiral, how on earth would we get men and equipment into the area?’

Canaris shook his head. ‘No, Hans, you’ve got it wrong. We’re not talking direct military action here, we’re talking sabotage. The Führer wants us, the Abwehr, to blow up the Suez Canal on the day we invade Poland. Put the damn thing out of action. Close it down so fully that it would take a year or so to open it again.’

‘What a coup. It would shock the world,’ Ritter said.

‘More to the point, it would shock the British to the core and make them realize we mean business. At least that’s the way our beloved Führer sees it.’ Canaris sighed. ‘Of course, how the hell we are to accomplish this is another matter, but we’ll have to come up with something, at least on paper, and that’s where you come in, Hans.’

‘I see, Herr Admiral.’

The limousine pulled in to the kerb outside the Abwehr offices at 74–6 Tirpitz Ufer. The Petty Officer hurried round to open the door for Canaris and Ritter scrambled out after him. The young Luftwaffe officer was frowning slightly.

Canaris said, ‘Are you all right?’

‘Fine, Herr Admiral. It’s just that there’s something stirring at the back of my mind, something that could suit our purposes.’

‘Really?’ Canaris smiled and led the way up the steps, pausing at the door. ‘Well, that is good news, but sooner rather than later, Hans, remember that,’ and he led the way inside.

It was perhaps an hour later and Canaris was seated at his desk working his way through a mass of papers, his two favourite dachshunds asleep in their basket in the corner, when there was a knock at the door and Ritter entered with a file in one hand and a rolled-up map under his arm. He limped forward, leaning on his stick.

‘Could I have a word, Herr Admiral, on this Suez Canal venture?’

Canaris sat back. ‘So soon, Hans?’

‘As I said, there was something at the back of my mind, and when I got to my office I remembered. A report I received last month from a professor of archaeology here at the University, Professor Otto Muller. He’s recently returned from Southern Arabia. Intends to go back there soon. He needs additional funding.’

‘And what has this to do with us?’ Canaris asked.

‘As the Herr Admiral knows, all German citizens working abroad have to make a report to us here at Abwehr Headquarters of anything of an unusual nature that they may have come across.’

‘So?’

‘Allow me, Herr Admiral.’ Ritter went across to the map board on the far wall, unrolled the map under his arm and pinned it in place. It showed Egypt and the Suez Canal, the whole of Southern Arabia, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. ‘As you can see, Herr Admiral, the British in Aden, the Yemen and then various Arab states along the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, Dhofar and the Oman.’

‘Well?’ Canaris asked, examining the map.

‘You will notice Dahrein, a port on the Gulf coast. This is where Muller was working from. It belongs to Spain. Rather like Goa on the Indian coast. The Spaniards have been there for four hundred years.’

‘I can imagine what the place is like,’ Canaris said.

‘North across the border with Saudi Arabia is the Rubh al Khali, the Empty Quarter, one of the most awesome deserts on earth.’

‘And this is where Muller was operating?’

‘Yes, Herr Admiral.’

‘But what on earth was he doing?’

‘There are remains of many ancient civilizations in the area, inscriptions and graffiti on the rocks. Muller is an expert on ancient languages. He uses a latex solution to take impressions, which are brought back here to the University.’

‘And what has this to do with the Suez Canal, Hans?’

‘Bear with me, Herr Admiral. The area around there called Saba has long been associated with the Queen of Sheba.’

‘My God,’ Canaris said and returned to his desk. ‘Now it’s the Bible.’ He took a cigarette from a silver box. ‘I always understood that except for the biblical reference there has never been actual proof that she existed.’

‘Oh, she did exist, I can assure you,’ Ritter said. ‘There was a cult of the Arabian goddess. Asthar, their equivalent of Venus. In legend, the Queen of Sheba was high priestess of that cult and built a temple out there in the Empty Quarter.’

‘In legend,’ Canaris said.

‘Muller has found what he thinks could be the ruins of it, Herr Admiral. Naturally he kept his discovery quiet. Such an event would rival the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Archaeologists would descend from all over the world. As I said, he returned to Berlin for funding, but made a full description of his find in his report to Abwehr.’

Canaris frowned. ‘But where is this leading?’

‘This place is unknown, Herr Admiral, hidden out there in the desert. Used for supplies, an aircraft, it could provide a base for a strike against the Canal.’

Canaris got up and went to the map. He examined it and turned. ‘A thousand miles at least from that area to the Suez Canal.’

‘More like twelve hundred, Herr Admiral, but I’m sure I could find a way.’

Canaris smiled. ‘You usually can, Hans. All right, bring Muller to see me.’

‘When, Herr Admiral?’

‘Why now, of course, tonight. I intend to sleep in the office anyway.’

He returned to his papers and Ritter went out.

Professor Otto Muller was a small, balding man with a wizened face tanned to the shade of old leather by constant exposure to the desert sun. When Ritter ushered him into the office to meet Canaris, Muller smiled nervously, exposing gold-capped teeth.

Canaris said, ‘That will do, Hans.’ Ritter went out and Canaris lit a cigarette. ‘So, Professor, a remarkable find. Tell me about it.’

Muller stood there like a nervous schoolboy. ‘I was lucky, Herr Admiral. I’ve been working in the Shabwa area for some time and one night an old Bedouin staggered into my camp dying of thirst and fever. I nursed him back to life.’

‘I see.’

‘They’re a strange people. Can’t bear to be in debt so he repaid me by telling me where Sheba’s temple was.’

‘Payment indeed. Tell me about it.’

‘I first saw it as an outcrop of reddish stone, out there in the vastness of the Empty Quarter. The Herr Admiral must understand that there are sand dunes out there that are hundreds of feet high.’

‘Remarkable.’

‘As I got closer we entered a gorge. I had two Bedouin with me as guards. We had journeyed by camel. There was a flat plain, very hard-baked, then a gorge, a broad avenue of pillars.’

‘And the temple? Tell me about that.’

Which Muller did, talking for a good half-hour while Canaris listened intently. Finally the Admiral nodded. ‘Fascinating. Captain Ritter tells me you made an excellent report to Abwehr.’

‘I hope I know my duty, Herr Admiral, I’m a party member.’

‘Indeed,’ Canaris observed drily. ‘Then you will no doubt be pleased to return to this place with suitable funding and do what you are told to do. This is a project the Führer himself is interested in.’

Muller drew himself up. ‘At your orders, Herr Admiral.’

‘Good.’ Canaris pressed a button on his desk. ‘We’ll keep you informed.’

Ritter entered. ‘Herr Admiral?’

‘Wait outside, Professor,’ Canaris said, and waited until Muller had gone out. ‘He seems harmless enough, but I still have my doubts, Hans. If you used this place as a base it would require a flight of say twelve hundred miles to the Canal and what real damage could one bomber do? In fact, do we have a plane that could make the flight?’

‘I’ve already had a thought,’ Ritter said, ‘but I’d like to explore it further before sharing it with you.’

Canaris frowned. ‘Is this serious business, Hans?’

‘I believe it could be, Herr Admiral.’

‘So be it.’ Canaris nodded. ‘I don’t need to tell you to squeeze Muller dry, details of this Dahrein place, how the Spanish run it and so on. At least they’re on our side, which could be useful.’

‘I’ll see to it, sir.’

‘At your soonest, Hans. A feasibility study. I’ll give you three days.’

Ritter turned and limped out and Canaris went back to his papers.

2

On Wednesday morning Canaris, after sleeping once again on the little military bed in his office, was in the bathroom shaving when there was a knock at the door.

‘Come in,’ he called.

‘It’s me, Herr Admiral,’ Ritter replied. ‘And your breakfast.’

Canaris wiped his face and went out to the aroma of good coffee, and found an orderly arranging a tray on his desk, Ritter standing by the window.

‘Dismissed,’ Canaris said, and picked up his cup as the orderly went out. ‘Join me, Hans.’

‘I’ve already had breakfast, Herr Admiral.’

‘You must have risen early. How conscientious of you.’

‘Not really, Herr Admiral. It’s just that I find difficulty sleeping.’

Canaris was immediately all sympathy. ‘My dear Hans, how stupid of me. I’m afraid I often forget just how difficult life must be for you.’

‘The fortunes of war, Herr Admiral.’ He laid a file on the desk as Canaris buttered some toast. The Admiral looked up. ‘What’s this?’

‘Operation Sheba, Herr Admiral.’

‘You mean you’ve come up with a solution?’

‘I believe so.’

‘You think this thing could be done?’

‘Not only could it be done, Herr Admiral, I think it should be done.’

‘Really.’ Canaris poured coffee into the spare cup. ‘Then I insist that you have a cigarette and drink that while I see what you’ve got here.’

Ritter did as he was told and limped across to the window. The 3rd of April. Soon it would be Easter and yet it rained like a bad day in November. His leg hurt, but he was damned if he was going to take a morphine pill unless he really had to. He swallowed the coffee and lit a cigarette. Behind him he heard Canaris lift the telephone.

‘The Reich Chancellery, the Führer’s suite,’ the Admiral said, and added after a moment, ‘Good morning. Canaris. I must see the Führer. Yes, most urgent.’ There was a longer pause and then he said, ‘Excellent. Eleven o’clock.’

Ritter turned. ‘Herr Admiral?’

‘Excellent, Hans, this plan of yours. You can come with me and tell the man yourself.’

Ritter had never ventured beyond the main reception area at the Chancellery before and what he saw was breathtaking, not only the huge doors and bronze eagles but the Marble Gallery, which was four hundred and eighty feet long, the Führer’s special pride as it was twice as long as the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

When they were admitted to the Führer’s enormous study they found Hitler seated at his desk. He looked up. ‘Something important, I trust.’

‘I think so, my Führer,’ Canaris said. ‘This is my aide, Captain Ritter.’

Hitler took in the scarred face, the stick, the medals, rose, came round the table and took Ritter’s hand. ‘As a soldier I salute you.’

He went back to his chair and Ritter, overwhelmed, stammered, ‘What can I say, my Führer?’

Canaris intervened. ‘The question of the Suez Canal. Captain Ritter has come up with an extraordinary plan. In fact, what is the most extraordinary thing about it is its simplicity.’ He laid the file on Hitler’s desk. ‘Operation Sheba.’

Hitler leaned back, arms folded in an inimitable gesture. ‘I’ll read it later. Tell me, Captain Ritter.’

Ritter licked dry lips. ‘Well, my Führer, it all started with a professor of archaeology at the University called Muller and an extraordinary find he made in Southern Arabia.’

‘Fascinating,’ Hitler said, his eyes glowing, for his passion for architecture was intense. ‘I’d give anything to see that temple.’ He sat back. ‘But go on, Captain. You use the site as a base, but how does that advance the cause?’

‘The essence of the plan is its absurd simplicity. A single plane, a bomber trying to attack the Canal is an absurdity. One can never be certain of accuracy.’

‘So?’ Hitler said.

‘There is a two-engined amphibian called the Catalina, an American plane that can drop wheels and land on the ground as well as water. It has an extraordinary cruising range. Better than sixteen hundred miles carrying a bomb load of one and a half thousand pounds.’

‘Impressive,’ Hitler said. ‘And how would such a plane be used?’

‘As I say, absurdly simple, my Führer. The plane lands at our site in the desert and takes on not bombs, but mines. It flies to Egypt and lands on the Suez Canal itself. There the crew offload many mines, which will drift on the current. I would suggest somewhere near Kantra as a good spot. The crew will of course sink the Catalina, leaving on board a large quantity of our latest explosive, Helicon, which will do an enormous amount of damage to the Canal itself. I need hardly point out that the mines floating down will meet ships travelling north from Lake Timsah. I think we may count on several sinking and thus causing a further blockage.’

There was silence for a while as Hitler sat there staring into space and then he smacked a fist into his palm. ‘Brilliant and as you say, absurdly simple.’ He frowned. ‘But this plane, this Catalina. Can you get hold of one?’

‘There is one available for sale in Lisbon, my Führer. I thought we could buy it and start our own airline in Dahrein, a Spanish company, naturally. I’m sure there would be plenty of coastal trade.’

Hitler got up, came round the desk and clapped him on the shoulders. ‘Quite. I like this man, Herr Admiral. Put his plan into force at once. You have my full authorization.’

‘My Führer.’ Canaris led the way to the door, turned and forced himself to give the Nazi salute. ‘Let’s get out of here,’ he whispered to Ritter, turned and opened the door.

As they went along the Marble Gallery Canaris said, ‘You certainly covered yourself with glory there. Naturally I’ll authorize the necessary funding for the Catalina but it occurs to me that there might be a problem regarding a suitable crew. Of course, there is no reason why Germans should not be flying for a Spanish airline.’

‘But much better if they were Spanish,’ Ritter said.

‘And where would you procure them?’

‘The ranks of the SS, Herr Admiral, they have many Spanish volunteers.’

‘Of course,’ Canaris said. ‘It would be perfect.’

‘I have already tracked down a suitable pilot, a man with much combat experience in the Spanish Civil War. He is at present employed as a courier pilot by the SS. I’m seeing him later this morning at Gatow airfield.’

‘Good. I’ll come with you and see for myself,’ Canaris said, and led the way down the marble stairs.

Carlos Romero was twenty-seven; a saturnine, rather handsome young man, son of a wealthy Madrid wine merchant, he had learned to fly at sixteen, had joined the Spanish Air Force at the earliest possible moment and trained as a fighter pilot. When the Civil War came he had opted for Franco, not because he was a dedicated Fascist, but because that’s what people of his class did. He’d shot down eleven planes, and had the time of his life. He’d even flown with the German Condor Legion.

Suddenly it was all over and he didn’t want that, and then he’d got a whisper that the SS were taking Spanish volunteers. A pilot with his record they had snapped up without hesitation, employing him mainly on courier duties, ferrying high-ranking officers.

So here he was at the controls of a small Stork spotter plane a thousand feet above Berlin, an SS Brigadeführer behind him. He called the tower at Gatow, received permission to land and drifted down towards the airfield, bored out of his skull.

‘Mother of God,’ he whispered softly in Spanish, ‘there must be something better than this.’

There was, of course, and he found it when he went into the mess and took off his flying jacket, revealing a well-tailored SS uniform in field grey. He had a small Spanish shield on his left shoulder, and wore the Spanish Order of Merit for gallantry in the field and an Iron Cross First Class for his exploits with the Condor Legion.

He was aware of Canaris first, because of his high rank, although he did not recognize him, but Ritter he did, and went forward with genuine pleasure.

‘Hans Ritter, by all that’s holy.’

Ritter got up to greet him, leaning on his stick, and shook hands. ‘You look well, Carlos. Spain seems a long time ago.’

‘I heard about your leg. I’m sorry.’

Ritter said, ‘Admiral Canaris, Head of the Abwehr.’

Romero got his heels together and saluted. ‘An honour, Herr Admiral.’

‘Join us, Herr Hauptsturmführer.’ Canaris waved to the mess steward. ‘Champagne. Bollinger for preference, and three glasses.’ He turned to Romero. ‘You are a courier pilot, I understand. Do you like that?’

‘To be frank, Herr Admiral, these milk runs of mine bore me to death.’

‘Then we’ll have to see if we can find something more rewarding for you,’ Canaris said as the champagne arrived. ‘Tell him, Hans.’

Romero finished reading the file and closed it. His face was pale and excited as he looked up. Canaris said, ‘Are you interested?’

‘Interested?’ Romero accepted a cigarette from Ritter and his hand shook. ‘Herr Admiral, I’m willing to go down on my knees and beg.’

Canaris laughed. ‘No need for that.’

Ritter said, ‘The Catalina would not present you with a problem?’

‘Good God no, an excellent aircraft to fly.’

‘And what about a crew?’

Romero sat back thinking about it. ‘I could manage with a second pilot and an engineer.’

‘And where would we find them?’ Canaris asked.

‘Right here in the Spanish Legion of the SS. Like myself, Herr Admiral. I can think of two suitable candidates right now: Javier Noval, a fine pilot, and Juan Conde, an aircraft engineer of genius.’

Ritter made a note of the names. ‘Excellent. I’ll have them transferred to Abwehr duties along with yourself.’

‘What about the explosives and the mines?’ Romero asked.

‘We’ll have them delivered by some suitable freighter,’ Ritter told him. ‘There should be no problem in a place like Dahrein. You will naturally build up your credentials during the run-up to September. Coastal trade, freight, that kind of thing.’

Romero nodded slowly. ‘But I do have a suggestion. When the time comes we could make the transfer of the mines at sea. I could land beside the freighter with no problem. From there a direct flight to the base would simplify the whole thing.’

‘Excellent.’ Canaris stood up. ‘I think you should meet our friend Professor Muller. You can come back to town with us, drop me off on the way and then continue to the University. From now on, you deal with Captain Ritter in all things.’

‘At your orders. Herr Admiral.’

‘Good,’ Canaris said, and he turned and led the way out.

Muller’s department at the University was housed in a vast echoing hall filled with artefacts of every description. Egyptian mummies, statues from Rome and Greece, amphorae retrieved from ancient wrecks at the bottom of the Mediterranean, it was all there. Ritter and Romero browsed while Muller sat at his desk in his glass office and read the Operation Sheba file. Finally he got up and went to join them.

Ritter turned. ‘Well, what do you think?’

Muller was highly nervous, tried to smile and failed miserably. ‘A wonderful idea, Herr Hauptman, but I wonder if I have the qualifications you need. I mean, I’m not a trained spy, I’m just an archaeologist.’

‘This will be done, Professor, and by direct order of the Führer. Does this give you a problem?’

‘Good heavens no.’ Muller’s face was ashen.

Romero clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Don’t worry, Professor, I’ll look after you.’

Ritter said, ‘That’s settled then. When Hauptsturmführer Romero leaves from Lisbon in the Catalina, you go with him, so make your preparations. I’ll be in touch.’

Ritter limped away, his stick tapping the marble. As they moved along the hall to the entrance, Romero said to him, ‘He’s a nervous little bastard, Ritter.’

‘He’ll come to heel and that’s all that’s important.’ They went out of the main entrance and stood at the top of the steps. ‘I’ll make arrangements for the immediate transfer of you and Noval and Conde today. You’ll leave for Lisbon tomorrow, in civilian clothes naturally. I’ll arrange priority seats on the Lufthansa flight. As regards the purchase of the Catalina our man at the German Legation will be your banker. Once you’ve checked the plane out, report back to me on the Embassy secure phone. I’ll expect to hear from you by Thursday at the latest.’

‘Mother of God, but you don’t hang about, Hans, do you?’

‘I could never see the point,’ Ritter said, and started down the steps to the Mercedes.

The River Tagus, as someone once said, is the true reason for the existence of Lisbon, with its wide bays and many sheltered anchorages. It was from here that the great flying boats, the mighty clippers, left for America and it was here, attached to two buoys about three hundred yards out to sea from the waterfront, that Carlos Romero found the Catalina. He had arrived at the dock close to the Avenida da India together with Javier Noval and Juan Conde ten minutes early for the appointment with the owner’s agent, a man called da Gama. They stood at the edge of the dock looking out at the amphibian.

‘It looks good to me,’ said Noval, a tough young man around Romero’s age, who wore an old leather flying jacket.

Conde was older than either of them, thirty-five and stocky. He also wore a flying jacket and looked across at the Catalina, shading his eyes from the sun.

‘What do you think, Juan, can you handle it?’

‘Just try me.’

A motor boat nosed in to the dock and a man in a brown suit and Panama hat waved from the stern. ‘Señor Romero?’ he called in Spanish. ‘Fernando da Gama. Come aboard.’

They went down the steps and joined him, and he nodded to the boatman, who took the motorboat away.

‘She looks good?’ da Gama suggested.

‘She looks bloody marvellous,’ Romero told him. ‘What’s the story?’

‘A local shipping line had the idea of regular flights down to the island of Madeira. Purchased the Catalina in the United States last year. It has performed magnificently, but they wanted to concentrate on passengers and the capacity is limited – too limited for there to be any money in it. May I ask what your requirement would be?’

Romero stayed very close to the truth. ‘General freight in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, flying as far as Goa perhaps. It’s a new venture.’

‘I know that area,’ da Gama said. ‘The Catalina would be perfect.’

They bumped alongside a small floating dock and as the boatman killed his motor, Noval and Conde grabbed a line and tied up. Da Gama opened the cabin door and led the way in. Romero looked into the cockpit with conscious pleasure, took one of the pilot’s seats and reached for the control column. Noval took the other seat and examined the instrument panel.

‘What a beauty.’

Da Gama, Conde at his shoulder, opened a file. ‘I’ll just give you approximate dimensions. Length sixty-three feet, height twenty, wingspan a hundred and four. The twin engines are Pratt and Whitney, twelve hundred horsepower each. Cruising speed a hundred and eighty miles an hour. Remarkably long range. Without freight it is possible to fly for four thousand miles before the need to refuel. I can’t think of another aircraft that could do this.’

‘Neither can I,’ Romero told him and got up. ‘You can take us back now.’

As they scrambled into the motor boat da Gama tried the usual tack. ‘Of course, a number of people are interested.’

The motor boat pulled away and Romero said, ‘Drop the sales pitch, my friend, just draw up the contract. I’ll give you my lawyer’s name, we sign tomorrow and you’ll receive a cheque for your asking price. Satisfied?’

Da Gama looked astonished. ‘But of course, Señor.’

Romero took out a cigarette and accepted a light from Noval. He looked back at the Catalina and blew out a long plume of smoke.

‘Looks like we’re in business, boys,’ he said.

Baron Oswald von Hoyningen-Heune was Minister to the German Legation in Lisbon. An aristocrat and career diplomat of the old school, he was no Nazi and, like most of his staff, was thankful to be as far away from Berlin as possible. Initially wary of the strange Spaniard who was a Hauptsturmführer in the SS, and resigned to following orders from Berlin, he had been pleasantly surprised, had taken to Romero.

He rose to greet him now as the Spaniard entered his office. ‘My dear Romero, it went well?’

‘Couldn’t have been better. Da Gama will be in touch with the lawyer you gave me. You provide the funding and we conclude tomorrow. I’ll need to speak to Captain Ritter at Abwehr Headquarters at once, by the way.’

‘Of course.’ The Baron reached for the red secure phone on his desk and placed the call. ‘It shouldn’t take long.’ He stood up. ‘Cognac?’

‘Why not?’

Romero lit a cigarette and sat on one of the sofas. The baron handed him a glass and sat opposite. ‘All very intriguing, this business.’

‘And also highly secret.’

‘But of course. I’m not prying. In fact, I’d rather not know.’ He raised his glass. ‘But I’ll drink to your success anyway.’

At that moment the red phone rang. Romero said, ‘With your permission?’

‘But of course. I’ll leave you to it.’

The Baron went out and Romero picked up the phone. ‘Hans, is that you?’

‘Who else?’ Ritter said. ‘How did it go?’

‘Perfect,’ Romero told him. ‘A superb aircraft. I couldn’t be more pleased. Tell the Admiral we’re on our way.’

Ritter knocked on the door and went in. Canaris was drinking tea, one of the dachshunds on his lap. He looked up.

‘What is it, Hans?’

‘Romero has just spoken to me from Lisbon, Herr Admiral. The Catalina is perfect and the sale will be concluded tomorrow.’

‘Excellent.’ Canaris nodded. ‘Do an additional report bringing everything up to date and I’ll make an appointment for us to see the Führer.’

‘At once, Herr Admiral.’

As Ritter limped to the door, Canaris called, ‘Oh, and Hans.’

‘Yes, Herr Admiral?’

‘We’ll take Muller with us.’

The summons came sooner than they had expected and took them to the Chancellery for an appointment at ten o’clock that night. They picked up Muller at the University on the way and the news that he was to meet the Führer shocked him completely.

When they reached the reception area of Hitler’s suite the aide on duty rose to greet them. ‘I understand you have a report for the Führer, Herr Admiral.’

‘That’s right,’ Canaris said.

The aide held out his hand. ‘He would like to read it before seeing you.’

‘Of course.’

Canaris gave him the file; the aide opened the door and went in. Canaris nodded to the other two and they sat down.

Muller was trembling slightly and Canaris said, ‘Are you all right?’

‘For God’s sake, how do you expect me to feel, Admiral. This is the Führer we’re talking about. What do I say?’

‘As little as possible,’ Canaris told him and added with some irony, ‘Remember he’s a great man and behave accordingly.’

The door opened and the aide appeared. ‘Gentlemen, our Führer will see you now.’

The room was a place of shadows, and Hitler sat at the enormous desk with only the light of a single brass lamp. He was reading the file, closed it and looked up.

‘Still brilliant, Herr Admiral. An absolutely first-class job.’

‘Captain Ritter really deserves all the credit.’

‘No, Herr Admiral, I think after all this that Major Ritter would be more appropriate. In fact, I warn you that I could well steal him for my own staff.’

He stood up and Ritter said the obvious thing. ‘You do me too much honour, my Führer.’

Hitler came round the corner of his desk and approached Muller. ‘Professor Muller, isn’t it? An amazing discovery and you sacrifice it for the sake of the Reich.’

And Muller, shaking almost uncontrollably, said exactly the right thing. ‘For you, my Führer, for you.’

Hitler clapped him on the shoulders. ‘A great day is coming, gentlemen, the greatest in Germany’s history.’ He walked slowly away and the desk lamp threw his shadow across the huge map of the world. He stood there, arms folded. ‘You may go, gentlemen.’

Canaris nodded to the other two, jerked his head and led the way out.

Later, after dropping Muller off at the University, Canaris told the driver to take them back to Tirpitz Ufer. As they turned into a side street they came to a café on the corner, windows lighted.

Canaris leaned forward. ‘Stop here.’ He turned to Ritter. ‘A nightcap, coffee and schnapps. We’ll toast your promotion, Major.’

‘My pleasure, Herr Admiral.’

The café was almost deserted and the proprietor was overwhelmed. He ushered them to a booth by the window and hurriedly took the order. Canaris pulled out his cigarette case and proffered it to Ritter, who took one and gave him a light.

‘He was pleased,’ the Admiral said and blew out smoke. ‘Muller was a mess though. He’s not strong enough.’

‘I agree,’ Ritter said. ‘We need a professional to back him up.’

The proprietor brought coffee and schnapps on a tray and Canaris waved him away. ‘You’ll have to find somebody, an old Abwehr hand. Somebody reliable.’

‘No problem, Herr Admiral.’

‘You know this thing is so simple it could work,’ Canaris said and poured schnapps from the bottle into two glasses.

‘I agree,’ Ritter said.

Canaris nodded. ‘There’s only one problem.’

‘And what’s that, Herr Admiral?’

‘It won’t win us this coming war, my friend, nothing can do that. You see, Hans, we’re all going straight to hell, but here’s to your promotion anyway.’

He raised the glass of schnapps and drained it at a single swallow.

Dahrein

3

The wind, blowing across the Gulf from Africa, still carried some of the warmth of the day to Kane as he stood on the deck of the launch, listening.

There was no moon and yet the sky seemed to be alive, to glow with the incandescence of millions of stars. He breathed deeply, inhaling the freshness, and followed a school of flying-fish with his eyes as they curved out of the sea in a shower of phosphorescent water.

A door opened and light from the saloon momentarily flooded out as Piroo, the Hindu deckhand, came up the companionway with a mug of steaming coffee.

Kane sipped some of it gratefully. ‘That’s good.’

‘The Kantara is late tonight, Sahib,’ Piroo said.

Kane nodded and checked his watch. ‘Almost two a.m. I wonder what the old devil O’Hara is playing at?’

‘Perhaps it’s the whisky again.’

Kane grinned. ‘More than likely.’

As he finished his coffee, Piroo touched him on the arm. ‘I think she comes, Sahib.’

Kane listened intently. At first he was conscious only of the slap of the waves against the hull of the launch and the whisper of the wind, and then he became aware of a muffled, gentle throbbing across the water. In the distance, he saw the green pin-point of light that was the starboard navigation light of the Kantara.

‘Not before time,’ he said softly.

He went into the wheelhouse and switched on the navigation lights, and when he pressed the starter, the engine coughed into life. He waited until the steamer was almost upon them, before he opened the throttle gently and took the launch forward on a course which would bring them together.

The old freighter was doing no more than two or three knots, and Piroo put out the fenders as Kane took the launch in close. A Lascar appeared at the rail and tossed down a line which Piroo quickly secured. A rope ladder followed a moment later, and Kane cut the engines and went out on deck.

The high, rust-streaked side of the Kantara reared into the night, the single stack a long black shadow above. As he climbed the ladder, Kane wondered, and not for the first time, exactly what it was that kept this heap of scrap-iron floating.

He scrambled over the rail and said in Hindi, ‘Where’s the Captain?’

The Lascar shrugged. ‘In his cabin.’

He quickly climbed a companionway to the upper deck and knocked on the door of the captain’s cabin. There was no reply. After a moment, he opened it and went in. The cabin was in darkness and the stench was appalling. He fumbled for the light switch and turned it on.

O’Hara was on his bunk. He lay on his back in singlet and pants, mouth open, exposing decaying yellow teeth. Empty whisky bottles rolled across the floor with the motion of the ship, and Kane wrinkled his nose in disgust and went out on deck.

Another Lascar was waiting for him. ‘The mate, he say you go to bridge,’ the man said.

Kane crossed the deck quickly and climbed an iron ladder to the bridge. Guptas, the mate, was at the wheel, his turbaned head disembodied in the light from the binnacle.

Kane leaned in the doorway and lit a cigarette. ‘How long has he been like that?’

Guptas grinned. ‘Ever since we left Aden. It should take him at least two days to sleep this one off.’

‘What a way to run a ship,’ Kane said. ‘What happened this time, anyway? Why didn’t you call at Dahrein on the run-in from Bombay, as usual?’

‘We had cargo for Mombasa,’ Guptas told him. ‘After that, Aden.’

‘Skiros wasn’t too pleased,’ Kane said. ‘I presume you’ve got the stuff all right.’

Guptas nodded. ‘They should be bringing it up now. By the way, we have a passenger this trip.’

‘A passenger?’ Kane said incredulously. ‘On this tub?’

‘An American woman,’ Guptas said. ‘She wanted to leave Aden in a hurry. We were the only ship available and the Catalina wasn’t due for a week.’

Kane flicked his cigarette in a glowing spiral into the night.

‘Then I won’t hang about. No sense in waking her up. She might get curious.’

Guptas nodded in agreement. ‘I think that would be wise. A strange thing happened just before dawn yesterday.’

‘What was that?’

‘The Catalina – Romero’s Catalina. We saw it on the horizon about thirty miles out. It landed beside some Portuguese freighter. They were offloading crates.’

‘So what’s the difference between that and what we’re doing now? So Romero’s doing a little smuggling too.’ Kane shrugged. ‘We’ve all got to get by. I’ll see you next month.’ And he went down the ladder to the deck.

He leaned over the rail and watched two Lascars lower an oil drum down to Piroo on the deck of the launch. A voice said quietly from behind, ‘Do you happen to have a light?’

He turned quickly. She was rather tall and the smooth rounded face might have suggested weakness had it not been for the firm mouth. She wore a scarf and a light duster coat.

He held out a match in his cupped hands. ‘Rather late for a promenade round the deck.’

She blew smoke out and leaned against the rail. ‘I couldn’t sleep. The facilities for passengers on this ship are strictly limited.’

‘That I can believe.’

‘A strange place to meet a fellow-American.’

He grinned. ‘We pop up everywhere these days.’

She leaned over the rail and looked down at the launch. ‘That’s your boat, I presume?’

He nodded. ‘I’m a deep-sea fisherman out of Dahrein. Got caught in a storm and ran out of fuel. It’s lucky the Kantara came along.’

‘I suppose it is,’ she said.

Her perfume hung disturbingly in the air and, for some reason, he could think of nothing more to say. And then Piroo hailed him from the launch and he smiled. ‘I’ll have to be going.’

‘Ships that pass in the night,’ she said.

He went down the ladder quickly and Piroo cast off the line. The Kantara pulled away from them at once and, when he looked up, he could see the woman in the yellow glare of the deck lights, leaning over the rail watching them until they faded into the night.

He dismissed her from his mind for the moment, because there were more important things to think of. The two-gallon oil can stood on the deck where Piroo had left it. Kane checked it quickly and then went below to the saloon.

Piroo had the air tank ready, and Kane stripped to his shorts and the Hindu helped him on with it. They went up on deck. Piroo vanished into the wheelhouse and emerged with a large, powerful spot-lamp on a long cable, specially designed for underwater use, which plugged into the boat’s lighting system.

A ring bolt had been welded to each end of the oil can, and Piroo threaded a manilla rope through them as Kane pulled on his diving mask and gripped the mouth-piece of his breathing tube firmly between his teeth. He took the lamp in one hand and vaulted over the side.

For a moment, he paused to adjust the flow of oxygen and then he swam down in a long, sweeping curve that brought him underneath the hull.

The sensation of being alone in a silent world, of floating in space, was somehow accentuated by the circumstances. The water gleamed with a sort of phosphorescent fire all around him, and transparent fish, attracted by the lamp, glowed in its light.

After a moment, the oil can dropped down through the water. He grabbed the manilla rope with one hand and quickly passed it through two more ring bolts set in the keel of the launch.

He turned from securing it and paused, held by the wonder of the scene. The sea seemed alive with fish, incandescent, glowing like candles in its depths. A school of barracuda flashed by like silver streaks, and then an eight-foot shark swung into the beam of the lamp and poised there, watching him.

As it moved forward, he pulled his breathing tube from his mouth, emitting a stream of silvery bubbles. The shark altered course with a flick of its tail and disappeared into the gloom.

He swam up to the surface quickly and Piroo pulled him up over the low rail. ‘Everything all right, Sahib?’

Kane nodded as he unstrapped the tank. ‘No trouble at all. One shark, and he was only trying to be playful.’

The Hindu grinned, teeth flashing in the darkness, and handed him a towel, and Kane went below. The water had been surprisingly cold, and he rubbed himself down briskly and then dressed.

When he went back on deck, the wind was freshening and Piroo brought him more coffee. As he drank it, Kane caught a last glimpse of the Kantara’s navigation lights on the horizon, and remembered the woman.

She had certainly been attractive and he wondered what she was doing on an old tub like the Kantara. There could be no satisfactory answer, of course.

For a moment, he seemed to catch a faint touch of her perfume on the night air. He smiled wryly and, going into the wheelhouse, started the engines and took the launch forward into the night.

4

They came into Dahrein in the early afternoon. As the launch rounded the curved promontory crowded with its white houses, a two-masted dhow, lateen sails bellying in the Gulf breeze, moved out of harbour on the long haul across the Arabian Sea to India.

The Kantara was unloading at the jetty. On the white curve of the beach, fishermen sat patiently mending their nets and a few children played naked in the shallows.

Kane cut the engines and signalled to Piroo, who was standing in the stern, anchor ready in his hands. It disappeared into the green waters of the harbour with a splash. For a moment longer, the launch glided forward and then, with a gentle tug, it came to a halt fifty or sixty yards from the crumbling stone jetty that formed the east side of the harbour.

Piroo disappeared into the cabin, and Kane stepped out of the wheelhouse. He lit a cigarette and walked slowly along to the stern, where he stood with one foot on the brass rail, the peak of his battered and salt-stained cap pulled well forward to shield his eyes from the intense glare of the sun.

He was a tall, powerful man in faded blue denims and sweat-shirt. His brown hair was bleached by the sun and badly needed cutting, and there was a three days’ growth of beard on his chin. The sun-dried skin of his face was drawn tightly over prominent cheek-bones and his eyes were deep-set in their sockets, calm and expressionless, always staring into the middle distance or beyond the next hill as if perpetually searching for something.

As he looked across the harbour, a small rowing boat appeared from between two moored dhows. The brawny Arab who pulled on the oars was being urged on by a fat, bearded official in crumpled khaki uniform and white head-cloth. There was a slight cough from behind, and Kane reached out a hand without turning round. Piroo passed him a large gin-sling in which ice tinkled, and said gently, ‘Perhaps Captain González will wish to search the boat, Sahib?’

Kane shrugged. ‘That’s what he’s paid for.’

He sipped the drink slowly, savouring its coldness with conscious pleasure, and watched the boat approach. As it bumped against the side of the launch González smiled up at him, his face shiny with sweat, a paper Japanese fan fluttering in his right hand in a vain effort to keep the flies at bay.

Kane grinned down at him. ‘Looks as if the heat’s getting to you, Juan.’

González shrugged, and replied in perfect English, ‘Only duty compelled me to put in an appearance on the quay in my official capacity when the mail boat came in from Aden.’ He mopped his face with a corner of his head-cloth. ‘Where are you from this time?’

Kane finished his drink and handed the glass to Piroo, who was still standing at his elbow. ‘Mukalla,’ he said. ‘I had some letters to deliver for Marie Perret.’

González kissed his fingers. ‘Ah, the delightful Mademoiselle Perret. We are privileged men. Here on earth a glimpse of Paradise. Are you carrying any cargo?’

Kane shook his head. ‘We tried for a shark on the way back, but he took half my line as well as the hook.’

González raised a hand and rolled his eyes. ‘You Americans – so energetic, and for what?’

‘Are you coming aboard to check?’ Kane said.

González shook his head. ‘Would I insult a friend?’ He waved to the oarsman to push off. ‘I hurry home to a tall drink and the cool hand of my wife.’

Kane watched the boat disappear amongst the mass of moored fishing dhows that floated a few yards from the beach. After a while, he tossed his cigarette down into the water and turned from the rail. ‘I think I’ll go for a swim,’ he said. ‘Get the deck swabbed down, Piroo. Afterwards, you can go ashore to visit that girl of yours.’

He went below to the cabin and changed quickly. When he came back on deck, he was wearing an old pair of khaki shorts, and a cork-handled knife in leather sheath swung from the belt at his waist.

Piroo was standing by the rail, hauling vigorously on a rope, and a moment later a large canvas bucket appeared. He emptied its contents over the deck and threw it back into the water.

Kane didn’t bother with a diving mask. He went past Piroo on the run and dived cleanly over the rail. At this point, the harbour was some twenty feet deep, and he swam down through the clear green water, revelling in its coolness. For a brief moment he hovered over the bottom, and then he kicked against the white sand and started up.

When he had almost reached the surface, he changed direction slightly until he was underneath the hull. The two-gallon oil can still hung suspended beneath the keel as he had left it.

He examined it and then quickly surfaced. Piroo was standing at the rail, the canvas bucket in his hands. Kane nodded briefly, took a deep breath, and dived again.

When he reached the oil can, he took out his knife and slashed the rope which secured it in place. At that moment the canvas bucket bumped against his back and he pulled it towards him with his free hand and pushed the oil can inside. He jerked twice on the rope and the bucket was hoisted smoothly to the surface.

He was in no hurry. He swam down to the white sand of the harbour bottom again and then floated lazily upwards in a stream of sparkling bubbles. When he surfaced and hauled himself over the rail, the deck was deserted. A towel was lying on top of the hatch, neatly folded and waiting for him. He quickly dried his body and, as he went below, he was rubbing his damp hair briskly.

Piroo was squatting on the floor of the cabin. The oil can was between his knees and he expertly prised open the lid with a chisel. His hand disappeared inside and came out holding a bulky, oilskin package. He raised his face enquiringly. ‘Shall I open, Sahib?’

Kane shook his head. ‘We’ll let Skiros have that pleasure. After all, he’s paying. Better get rid of that can, though.’

The Hindu took the can and went up on deck. Kane hefted the package in his hands for a second, a slight frown on his face, then he dropped it on to the table and went and lay on the bunk.

Tiredness flooded through him in a sudden wave and he remembered that he hadn’t slept for the past twenty-four hours. He closed his eyes and relaxed. There was the unmistakable bump of a boat against the side of the launch, and Piroo appeared in the doorway. ‘It is Selim, Sahib.’

For a moment Kane sat on the edge of the bunk, a frown on his face, and then he slipped a hand under the pillow and took out a .45-calibre Colt automatic. He pushed it into the waistband of his pants, brushed past Piroo, and went up on deck.

A tall Arab was climbing over the rail. He was dressed in immaculate white robes, and his head-cloth was bound with cords of black silk. Cold eyes flashed in a swarthy face and his mouth was thin and twisted by an old scar, which disappeared into the beard.

‘What the hell do you want?’ Kane demanded.

Selim fingered the silver half of the curved jambiya at his belt. ‘Skiros sent me,’ he said. ‘I have come for the package.’

‘Then you can bloody well go back to Skiros and tell him to come himself,’ Kane said. ‘I’m particular who I have on my boat.’

‘One day you will go too far,’ Selim said softly. ‘One day I may have to kill you.’

‘I’m frightened to death.’

The Arab controlled his anger with difficulty. ‘The package.’

Kane pulled the Colt from his waistband and cocked it. ‘Get off my boat.’

In the sudden dangerous silence which followed, a cask boomed hollowly from across the harbour as a labourer rolled it along the wharf. Selim’s hand tightened over the hilt of his jambiya, and Kane took a quick pace forward, lifted a foot and pushed him back over the low rail.

The two Arab seamen who were sitting at the oars of the heavy rowing boat hastily pulled their master over the stern, where he sprawled for a moment, coughing up water, sodden robes clinging to his body.

Kane stood with a foot on the rail, the Colt held negligently in one hand. For a moment Selim glared up at him and then he snapped his fingers and the two oarsmen pushed off from the launch, faces expressionless.

On the other side of the rusty freighter at the jetty, a large, three-masted dhow was moored, which Kane recognized as Selim’s boat, the Farah. The rowing boat moved slowly towards it and, after watching for a few moments, he turned from the rail.

Piroo shook his head slowly and his face was troubled. ‘That was a bad thing to do, Sahib. Selim will not forget.’

Kane shrugged. ‘Let me worry about that.’ He yawned lazily as the tiredness took hold of him again. ‘I think I’ll sleep for a while. Let me know when Skiros turns up.’

Piroo nodded obediently and squatted on the deck, his back against the rail, as Kane went below.

He pushed the Colt back under the pillow, poured himself a drink, and then lit a cigarette and went to the bunk. He lay with his head against the pillow, staring at the roof of the cabin, watching the blue smoke twist and swirl in the current from the air conditioner, and thought about Selim.

He was well known in every port from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf. He traded in anything that would make him a profit – gold, arms, even human beings. That was the part of his activities which Kane couldn’t stomach. There was still a heavy demand for slaves, particularly female, in most Arab countries. Selim did his best to satisfy that demand. His speciality was young girls.

Kane wondered how Selim would react if the Farah happened to meet with an accident one dark night. It could be simply arranged. A charge of that plastic water-proof explosive he had used on the salvage job at Mukalla would do the trick. It was a pleasant thought.

His eyes closed and the darkness moved in on him.

He had slept for no more than an hour when a gentle pressure on his shoulder caused him to awaken. Piroo was standing by the bunk.

Kane pushed himself up on one elbow. ‘What is it – Skiros?’

The Hindu nodded gravely. ‘He is waiting on the jetty, Sahib.’

Kane swung his legs to the floor, stood up and stretched. ‘Okay, you’d better bring him across in the dinghy.’

He went up on deck, the Hindu at his heels. Skiros was standing on the edge of the jetty, his face shaded by a large Panama hat. He was wearing a soiled white linen suit, and a slight breeze lifted from the water against him, moulding his grotesque figure.

As Piroo dropped down into the dinghy and sculled rapidly towards him, the Greek raised his malacca cane and called cheerfully, ‘Is it safe for me to come across? I’ve already had one bath today.’

Kane waved a hand. ‘I’ll have a drink waiting for you.’

He watched Skiros negotiate the iron ladder pinned to the side of the jetty and safely step into the dinghy, and then he went below. He had just finished mixing two gin-slings when the dinghy bumped against the hull of the launch. A moment later Skiros creaked heavily down the stairs and entered the cabin.

He flopped into a chair with a groan. ‘Why the hell do you have to anchor your boat in the middle of the harbour? Why can’t you tie up at one of the jetties like everybody else?’

Sweat stained his jacket in great patches and trickled along the folds of his fat face. He produced a red silk handkerchief and mopped the worst of it away, then removed his Panama and proceeded to fan himself. His hair was shiny with pomade and carefully combed, and his tiny black eyes sparkled with cunning.

Kane handed him one of the drinks. ‘You should know me by now. I don’t trust anybody in this damned town. Let’s say I prefer to have a moat around me.’

Skiros shook his head. ‘Crazy Americans. I shall never understand you.’ He sipped appreciatively at his drink and then placed it carefully on the table. ‘I believe you had a little trouble with Selim?’

Kane lit a cigarette. ‘I wouldn’t call it trouble. I simply tossed him off my boat. Since when has he been working for you, anyway?’

The Greek shrugged, and took his time over lighting an oily black cheroot. ‘I find him useful, now and then. He does the odd trip to India for me when it’s necessary. I only sent him this afternoon because I was busy with something else.’

Kane frowned. ‘Well, don’t send him again. I don’t like his smell. I once picked up four slaves he dumped overboard three miles out in the Gulf when a British gunboat was on his heels.’

Skiros shrugged and raised one hand in a gesture of submission. ‘All right, so you don’t like the way he makes his money, but take a tip from me. He’s lost a lot of face over the way you treated him this afternoon. From now on I’d be extremely careful if I were you.’

Kane pushed the oilskin package across the table. ‘Let’s get down to business.’

Skiros produced a clasp knife and proceeded to cut open the package carefully. ‘Did you have any trouble?’

Kane shook his head. ‘I was at the rendezvous just after midnight. The boat was late, and O’Hara was drunk as usual. Guptas was in charge. He told me something interesting.’

‘What was that?’

‘They saw the Catalina about thirty miles out, off-loading from a Portuguese freighter.’

Skiros laughed. ‘So Romero’s developed sticky fingers too. That is interesting. What about customs when you came in?’

Kane shrugged. ‘No trouble there. Gonzalez didn’t even come on board. All that business with the oil can under the keel was a waste of time.’

Skiros shook his head. ‘Nothing is a waste of time in this work. One day, when you least expect it, he will take it into his head to perform his duties conscientiously.’ He removed the outer wrappings of the package as he spoke, and revealed a neat stack of Indian rupees.

As Skiros counted the bundles, Kane shook his head. ‘I’ll never understand this racket. Gold smuggled into India, rupees smuggled out.’

Skiros smiled. ‘It’s all a question of exchange. In this modern world it is really so easy to make money. One doesn’t need to steal at all.’ His face was shiny with sweat once more. He held his hands lightly over the stack of bank-notes and sighed. ‘Ah, my friend, if you knew the effect money has on me. When I moved here from Goa six months ago I’d no idea what a gold mine the place is.’

Kane poured himself another drink. ‘Why don’t you try spending some of it once in a while?’

Skiros shrugged. ‘I started life on a mountain farm in northern Greece. The fields were more stones than soil. My mother was an old woman at twenty-five, and one year, when the crops failed in the drought, my two sisters died of starvation. It is something I have never forgotten. That is why I live only to make money. I gloat over the size of my bank balance. I begrudge every penny I have to pay out.’

Kane grinned. ‘While we’re on the subject of paying out, I’ll take my cut now. Dollars as usual, if you don’t mind.’

Skiros laughed so that the flesh trembled on his huge body. ‘But I would never forget you, my friend. After all, you are an essential part of my whole organization. The king-pin, I believe you call it.’

‘Skip the flattery and let’s have the cash,’ Kane said.

Skiros produced a bulging wallet and proceeded to count out hundred-dollar bills. His hands were sweating, and he placed each bill reluctantly upon the table. When he had reached twenty, he paused, then added five more. ‘There you are, my friend,’ he said. ‘We agreed on two thousand, but I give you a bonus of five hundred dollars. Let no man say Skiros does not reward good service.’

Kane swept the bills into the table drawer. ‘You old spider. You know damned well, most of it will come back to you, either over the bar at your hotel or across the gambling tables.’

Skiros laughed again, his face crinkling so that the eyes almost disappeared, and pushed himself to his feet. ‘Now I must go.’ He moved to the door and then paused. ‘But I am forgetting some important news.’ He turned slowly. ‘A woman came in from Aden on the boat this afternoon. An American named Cunningham – Mrs Ruth Cunningham. Extremely pretty. She has been asking for you.’

Kane stiffened, a surprised frown crossing his face. ‘I don’t know anyone called Cunningham.’

Skiros shrugged. ‘She appears to know you, or to know of you at least. She is staying at my hotel. I told her I would be seeing you, and she asked me to give you a message. She would like you to come to the hotel. She said it was most important.’

Kane still frowned down at the table, leaning forward, his weight on his hands. After a slight pause Skiros said, ‘You will come?’

Kane straightened up and nodded. ‘Sure, I’ll come. I’ll be there some time this evening.’

Skiros nodded. ‘Good, I shall tell her.’ He smiled. ‘Don’t look so worried. Perhaps she is only a tourist. Maybe she wishes to charter your boat to go spear-fishing along the reef.’

Kane nodded slowly. ‘Yes, you’re probably right.’ But he didn’t believe that was the reason – not for a moment – and, after Skiros had gone, he went back to the bunk and lay staring at the ceiling, groping back into the past, trying to place Ruth Cunningham. But it was no good. The name meant nothing to him.

He glanced at his watch. It was just after three, and for a little while longer he lay there; then, with a sigh of exasperation, he swung his legs to the floor and started to dress.

He pulled on his faded denims and a sweat-shirt and went up on deck. Piroo was lounging against the rail, head bowed against his chest so that only the top of his white turban was visible. Kane stirred him slightly with one foot, and the Hindu came awake at once and rose easily to his feet. ‘I’m going ashore,’ Kane said. ‘What about you?’

Piroo shrugged. ‘I think not, Sahib. Later, perhaps. I will row you across to the jetty and then return with the dinghy. It would be wiser. Selim might return.’

Kane nodded. ‘Maybe you’ve got a point. If he does, you’ll find my Colt underneath the pillow. Don’t hesitate to use it. I’ve got more friends round here than he has.’

He dropped over the side into the dinghy, and Piroo took the oars and pulled rapidly towards the crumbling stone jetty. When they reached it, Kane stepped on to the iron ladder and climbed it quickly. As his eyes drew level with the top of the jetty, he saw a woman sitting on a large stone a few feet away, watching him.

He moved forward and she got to her feet and came to meet him. She was dressed in an expensive white linen dress, a blue silk scarf was bound round her head, peasant-fashion, and she wore sunglasses.

When she removed them, he recognized her at once as the woman he had met on the Kantara the previous night.

She smiled uncertainly, and there was puzzlement in her voice. ‘You again! But I was looking for Captain Kane – Captain Gavin Kane.’

‘That’s me,’ he said. ‘You’ll be Mrs Cunningham. What can I do for you?’

She frowned and shook her head in bewilderment. ‘Mr Andrews, the American Consul in Aden, advised me to look you up. He told me you were an archaeologist. That you were an expert on Southern Arabia.’

He smiled slightly. ‘I presume, you mean I don’t look the part. Andrews was right on both counts. I am an archaeologist among other things, and I do know something about Southern Arabia. In what way can I help you?’

She stared out over the harbour, a slight frown on her face, and then she turned and looked at him coolly from steady grey eyes. ‘I want you to find my husband, and I’m willing to pay highly for your services.’

He reached for a cigarette and lit it slowly. ‘How high?’

She shrugged and said calmly. ‘Five thousand dollars now and another five when, and if, you find him.’

For several moments they stood looking at each other and then he sighed. ‘Let’s discuss this over a cold drink. I know just the place.’ And he took her arm, and they went along the jetty to the waterfront.

5

They didn’t talk much on the way to the hotel. Ruth Cunningham replaced her sunglasses and gazed about her with obvious interest, and Kane employed the time in studying her.

As they turned off the jetty and moved along the waterfront, he decided that Skiros had been wrong. She was not pretty – she was beautiful. The long slim lines of her were revealed to perfection by the simple linen dress as she walked. It had been a long time since he had talked to a woman like her – to a woman of his own kind.

The hotel was a tall, slender building with a crumbling façade and one narrow entrance that fronted on to the street. Inside, an ancient fan slowly revolved in the stifling heat, and he led the way across the entrance hall and into the bar.

There was no one there and the French windows which gave access to the terrace outside, creaked in the slight breeze from the harbour. Ruth Cunningham removed her sun glasses and frowned.

‘Isn’t there any service in this place?’

Kane shrugged. ‘There isn’t a great deal of action around here. Most people sleep during the afternoon. They figure it’s too hot to do anything else.’

She smiled. ‘Well, they say travel broadens the mind.’

He went behind the bar. ‘Why don’t you go and sit on the terrace while I get you a drink? There’s a wind coming in from the sea. You might find it a little cooler.’

She nodded, walked out through the French windows and sat down in a large cane chair shaded by a gaudy umbrella. Kane opened the ancient icebox that stood under the bar and took out two large bottles of lager, so cold the moisture had frosted on the outside. He knocked off the caps on the edge of the zinc-topped bar, poured the contents into two tall, thin glasses and went out to the terrace.

She smiled up at him gratefully when he handed her the glass, and quickly swallowed some of the beer. She sighed. ‘I’d forgotten anything could be so cold. This place is like a furnace. Frankly, I can’t imagine anyone living here from choice.’

He offered her a cigarette. ‘Oh, it has its points.’

She smiled slightly. ‘I’m afraid they’ve escaped me so far.’

She leaned back against the faded cushions of her chair. ‘Mr Andrews told me you were from New York. That you were a lecturer in archaeology at Columbia.’

He nodded. ‘That was a long time ago.’

She said casually, ‘Are you married?’

He shrugged. ‘Divorced. My wife and I never hit it off.’

Ruth Cunningham flushed. ‘I’m sorry I brought it up. I hope I haven’t upset you?’

‘On the contrary,’ he said. ‘We all make mistakes. My wife’s was in assuming that university professors are well paid.’

‘And yours?’

‘Mine lay in imagining I could be content with the ordered calm of academic life. I’d only stuck it for Lillian’s sake. She set me free in more ways than one.’

‘And so you came East?’

‘Not at first. The Air Corps was offering a full-time flying course for one year, then four on the reserve. I did that. Trained as a regular pilot. It was after that I came out here. I was in Jordan with an American expedition six years ago, then I did some work for the Egyptian government, but it didn’t last long. I came to Dahrein with a German geologist who needed someone who could speak Arabic. When he left, I stayed.’

‘Don’t you ever feel like going back home?’

‘To what?’ he said. ‘An assistant-professorship trying to teach ancient history to students who don’t want to know?’

‘Has Dahrein anything better to offer?’

He nodded. ‘There’s something about the place that gets into your bones. This was once Arabia Felix – Happy Arabia. It was one of the most prosperous countries in the ancient world because the spice route from India to the Mediterranean passed through here. Now it’s just a barren waste, but up there in the hills, and north into the Yemen, is the last great treasure hoard for the archaeologist. City after city, some standing in ruins – like Marib, where the Queen of Sheba probably lived – others buried beneath the sand of centuries.’

‘So archaeology is still your first love,’ she said.

‘Very much so, but we didn’t come here to talk about me, Mrs Cunningham. Isn’t it time we got on to the subject of your husband?’

She took a slim gold case from her purse, selected a cigarette and tapped it thoughtfully against her thumbnail. ‘It’s difficult to know where to begin.’ She laughed ruefully. ‘I suppose I was always rather spoilt.’

Kane nodded. ‘It sounds possible. What about your husband?’

She frowned. ‘I met John Cunningham back home at some function or other. He was an Englishman from the School of Oriental Studies in London, lecturing at Harvard for a year. We got married.’

Kane raised his eyebrows. ‘Just like that?’

She nodded. ‘He was tall and distinguished and very English. I’d never met anything quite like him before.’

‘And when did the trouble start?’

She smiled slightly. ‘You’re very perceptive, Captain Kane.’ For a few moments she stared down into her glass. ‘To be perfectly honest, almost straightaway. I soon discovered that I’d married a man of strong principles, who believed in standing on his own two feet.’

‘That sounds reasonable enough.’

She shook her head and sighed. ‘Not to my father. He wanted him to join the firm, and John wouldn’t hear of it.’

Kane grinned. ‘Well, bully for John. What happened after that?’

She leaned back in her chair. ‘We lived in London. John had a research job at the University. Of course it didn’t pay very much, but my father had given me a generous allowance.’

‘To enable you to live in the style to which you were accustomed?’ he said, and there was something suspiciously close to amusement in his voice.

She flushed slightly. ‘That was the general idea.’

‘And your husband didn’t like it?’

She got to her feet, walked to the parapet and looked out across the harbour. ‘No, he didn’t like it one little bit.’ Her voice was flat and colourless, and when she turned to face him, he realized she was very near to tears. ‘He accepted the arrangement because he loved me.’

She came back to the table and sank down into her chair. Kane gently placed his hand on hers. ‘Would you care for another drink?’ She shook her head slightly and he shrugged and leaned back in his chair.

She pushed a tendril of hair back into place with one hand in a quick, graceful gesture and continued, ‘You see, my father was a self-made man. He had to fight every inch of the way and he told John pretty plainly that he didn’t think much of him.’

‘And how did that affect your husband?’

She shrugged. ‘I insisted on living in the way I’d been used to, and it took my own money to do it. John began to feel inadequate. Gradually he withdrew into himself. He spent more and more time at the University on his research. I think, in some crazy kind of way, he hoped he might make a name for himself.’

Kane sighed. ‘That makes sense. And then he walked out on you, I suppose?’