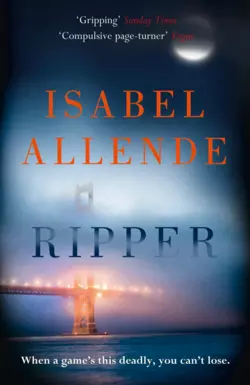

Ripper

Isabel Allende

For teenage sleuth Amanda Martín and her friends, Ripper was all just a game. But when security guard Ed Staton is found dead in the middle of a school gym, the murder presents a mystery that baffles the San Francisco police, not least Amanda’s father, Deputy Chief Martín. Amanda goes online, offering ‘The Case of the Misplaced Baseball Bat’ to her fellow sleuths as a challenge to their real-life wits. And so begins a most dangerous obsession.The murders begin to mount up but the Ripper players, free from any moral and legal restraints, are free to pursue any line of enquiry. As their unique powers of intuition lead them ever closer to the truth, the case becomes all too personal when Amanda’s mother suddenly vanishes. Could her disappearance be linked to the serial killer? And will Amanda and her online accomplices solve the mystery before it’s too late?

Copyright (#ulink_14aa7327-e40c-58e8-8eae-6d16696fea02)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

Copyright © Isabel Allende 2014

Translation copyright © Isabel Allende

Originally published in Spain in 2014 by Random House Mondadori under the title El juego de Ripper

Isabel Allende asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007548941

Ebook Edition © January 2014 ISBN: 9780007548965

Version: 2015-02-02

Dedication (#ulink_144089d5-b6f1-56f7-842d-a3a67e8ed125)

To William C. Gordon, my partner in love and crime

Contents

Copyright (#ulink_02cf9edd-c26f-562a-bbba-97bc90fa7724)

Dedication (#ulink_d84a1cd3-e995-5f7f-a6b4-7695b91a226d)

Mom is still alive, but (#ulink_0a432933-fbe8-5d90-88ad-58626d1506f9)

January (#ulink_d82fe2a3-afca-57d3-bf97-e506c725ed32)

Monday, 2 (#ulink_c4879461-847b-5704-8195-d8ea869750af)

Tuesday, 3 (#ulink_c5b9fbd3-a88f-5195-a67e-e72f5b9eedae)

Wednesday, 4 (#ulink_76615159-2b28-5bab-9fbe-13e6ba2106b0)

Thursday, 5 (#ulink_0a693c97-7660-510c-9535-a773017d50ac)

Saturday, 7 (#ulink_f5de7ef6-e362-567d-bcdd-8fd3dc74e5cb)

Sunday, 8 (#ulink_afc7abbd-25fe-5166-af43-aa38fda286e7)

Monday, 9 (#ulink_a73e9e5f-2f39-5f75-b8b5-d0cbbb0d84dd)

Tuesday, 10 (#ulink_62204068-4470-5a8f-84bd-814b33c06cbb)

Wednesday, 11 (#ulink_8079a901-e31a-580a-9e02-fb38cff81413)

Friday, 13 (#ulink_7e705fd2-764f-5f07-8d15-15439c70d620)

Sunday, 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

February (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

March (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday, 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

April (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday, 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday, 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday, 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday, 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday, 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, August 25, 2012 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Isabel Allende (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Mom is still alive, but (#ulink_e77c4c43-8b45-5f91-90b4-931f68949a93) she’s going to be murdered at midnight on Good Friday,” Amanda Martín told the deputy chief, who didn’t even think to question the girl; she’d already proved she knew more than he and all his colleagues in Homicide put together. The woman in question was being held at an unknown location somewhere in the seven thousand square miles of the San Francisco Bay Area; if they were to find her alive, they had only a few hours, and the deputy chief had no idea where or how to begin.

They referred to the first murder as the Case of the Misplaced Baseball Bat, so as not to insult the victim by giving it a more explicit name. “They” were five teenagers and an elderly man who met up online for a role-playing game called Ripper.

On the morning of October 11, 2011, at 8:15 a.m., the fourth-grade students of Golden Hills Elementary School raced into the gym to whistle blasts from their coach in the doorway. The vast, modern, well-equipped gym—built using a generous donation from a former pupil who had made a fortune in the property market before the bubble burst—was also used for graduation ceremonies, school plays, and concerts. Normally the fourth-graders would run two laps around the basketball court to warm up, but this morning they came to a shuddering halt in the middle of the hall, shocked by the grisly sight of a man sprawled across a vaulting horse, his pants pooled around his ankles, his buttocks bared, and the handle of a baseball bat inserted into his rectum. The stunned children stood motionless around the corpse until one nine-year-old boy, more daring than his classmates, bent down, ran his finger through the dark stain on the floor, and realized that it was not chocolate but congealed blood; a second boy picked up a spent bullet cartridge and slipped it into his pocket, intending to swap it during recess for a porn magazine, while a girl filmed the scene on her cell phone. Just then the coach bounded over to the little group of students, whistle trilling with every breath, and, seeing this strange spectacle—which did not look like a prank—suffered a panic attack. The fourth-graders raised the alarm; other teachers quickly appeared and dragged the children kicking and screaming from the gym, followed reluctantly by the coach. The teachers removed the baseball bat, and as they laid the corpse out on the floor, they noticed a bullet hole in the center of the victim’s forehead. They covered the body with a pair of sweatpants, closed the door, and waited for the police, who arrived precisely nineteen minutes later, by which time the crime scene had been so completely contaminated it was impossible to tell what the hell had happened.

A little later, during the first press conference, Bob Martín announced that the victim had been identified as one Ed Staton, forty-nine, a school security guard. “Tell us about the baseball bat!” a prurient tabloid journalist yelled. Furious to discover that information about the case had been leaked, which was not only humiliating to Ed Staton but possibly damaging to the reputation of the school, the deputy chief snapped that such details would be addressed during the autopsy.

“What about suspects?”

“This security guard, was he gay?”

Deputy Chief Martín ignored the barrage of questions and brought the press conference to a close, assuring those present that the Personal Crimes Division would keep the media informed of all pertinent facts in the investigation now under way—an investigation he would personally oversee.

A group of twelfth-graders from a nearby high school had been in the gym the night before, rehearsing a Halloween musical involving zombies and rock ’n’ roll, but they did not find out what had happened until the following day. By midnight—some hours before the crime was committed, according to police—there was no one in the school building. Three teenagers in the parking lot, loading their instruments into a van, had been the last people to see Ed Staton alive. In their statements they said that the guard had waved to them before driving off in a small car at about twelve thirty. Although they were some way off, and there was no lighting in the parking lot, they had clearly recognized Staton’s uniform in the moonlight, but could not agree on the color or make of the car he was driving or whether anyone had been in the vehicle with him. The police quickly worked out that it was not the victim’s car, since Staton’s silver-gray SUV was parked a few yards from the band’s van. It was suggested that Staton had driven off with someone who was waiting for him, and who came back to the school later to pick up his car.

At a second press conference, the deputy chief of the Personal Crimes Division explained that the guard was not due to finish his shift until 6:00 a.m., and that they had no information about why he had left the school that night, returning later only to find death lying in wait. Martín’s daughter Amanda, who was watching the press conference on TV, phoned her father to correct him: it was not death that had been lying in wait for Ed Staton, but a murderer.

For the Ripper players, this first murder was the start of what would become a dangerous obsession. The questions they were faced with were those that also puzzled the police: Where did the guard go in the brief period between being seen by the band members and the estimated time of death? How did he get back to the school? Why had the guard not tried to defend himself before being shot through the head? What was the significance of a baseball bat being inserted into such an intimate orifice?

Perhaps Ed Staton had deserved his fate, but the kids who played Ripper were not interested in moral issues; they focused strictly on the facts. Up to this point the game had revolved around fictional nineteenth-century crimes in a fog-shrouded London where characters were faced with scoundrels armed with axes and icepicks, archetypal villains intent on disturbing the peace of the city. But when the players agreed to Amanda Martín’s suggestion that they investigate murders in present-day San Francisco—a city no less shrouded in fog—the game took on a more realistic dimension. Celeste Roko, the famous astrologer, had predicted a bloodbath in the city, and Amanda decided to take this unique opportunity to put the art of divination to the test. To do so she enlisted the help of the other Ripper players and her best friend, Blake Jackson—her grandfather, coincidentally—little suspecting that the game would turn violent and that her mother, Indiana Jackson, would number among its victims.

The kids who played Ripper were a select group of freaks and geeks from around the world who had first met up online to hunt down and destroy the mysterious Jack the Ripper, tackling obstacles and enemies along the way. As games master, Amanda was responsible for plotting these adventures, carefully bearing in mind the strengths and weaknesses of the players’ alter egos.

A boy in New Zealand who had been paralyzed by an accident and was confined to a wheelchair—but whose mind was still free to explore fantastical worlds, to live in the past or in the future—created the character of Esmeralda, a cunning and curious gypsy girl. A shy, lonely teenager who lived with his mother in New Jersey, and who for two years now had left his bedroom only to go to the bathroom, played Sir Edmond Paddington, a bigoted, cantankerous retired English colonel—an invaluable character, since he was an expert in weapons and military strategy. A nineteen-year-old girl in Montreal who had spent much of her short life in the hospital suffering from an eating disorder, had created Abatha, a psychic capable of reading minds, manipulating memories, and communicating with the dead. A thirteen-year-old African American orphan with an IQ of 156 and a scholarship to an academy in Reno for gifted children decided to be Sherlock Holmes, since logic and deductive reasoning came effortlessly to him.

In the beginning, Amanda did not have her own character. Her role was simply to oversee the game and make sure players respected the rules; but given the impending bloodbath, she allowed herself to bend those rules a little. She moved the action of the game from London, 1888, to San Francisco, 2011. Furthermore—now in direct breach of the rules—she created for herself a henchman named Kabel, a dim-witted but loyal and obedient hunchback she tasked with obeying her every whim, however ridiculous. It didn’t escape her grandfather’s notice that the henchman’s name was an anagram of his own. At sixty-four, Blake Jackson was much too old for children’s games, but he agreed to participate in Ripper so he and his granddaughter would have something more in common than horror movies, chess matches, and the brainteasers they set each other—puzzles and problems he sometimes managed to solve by consulting a couple of friends who were professors of philosophy and mathematics at Berkeley.

January (#ulink_f0ae5f25-ab22-5868-b18a-2e7375162c1a)

Monday, 2 (#ulink_a5f4b890-736a-5834-bf10-80000153faf1)

Lying facedown on the massage table, Ryan Miller was dozing under the healing hands of Indiana Jackson, a first-degree Reiki practitioner, well versed in the techniques developed by the Japanese Buddhist Mikao Usui in 1922. Having read sixty-odd pages on the subject, Ryan knew that there was no scientific proof that Reiki was actually beneficial, but he figured it had to have some mysterious power, since it had been denounced by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2009 as dangerous to Christian spiritual welfare.

Indiana worked in Treatment Room 8 on the second floor of North Beach’s famous Holistic Clinic, in the heart of San Francisco’s Little Italy. The door to the surgery was painted indigo—the color of spirituality—and the walls were pale green, the color of health. A sign in copperplate script read INDIANA, HEALER, and beneath it was a list of the therapies she offered: intuitive massage, Reiki, magnet therapy, crystal therapy, aromatherapy. One wall of the tiny waiting room was decorated with a garish tapestry, bought from an Asian store, of the Hindu goddess Shakti as a sensual young woman with long raven hair, dressed all in red and adorned with golden jewels. In one hand she held a sword, in another a flower. The goddess was depicted as having many arms, and each hand held one of the symbols of her power—which ranged from a musical instrument to something that looked like a cell phone. Indiana was such a devout disciple of Shakti that she had once considered taking her name until her father, Blake Jackson, managed to convince her that a Hindu goddess’s name was not appropriate for a tall, voluptuous blond American with the looks of an inflatable doll.

Given the nature of his work and his background in the military, Ryan was a skeptic, yet he gratefully surrendered to Indiana’s tender ministrations. He left each session feeling weightless and euphoric—something that could be explained either as a placebo effect combined with his puppyish infatuation with the healer, as his friend Pedro Alarcón suggested, or, as Indiana insisted, by the fact that his chakras were now correctly aligned. This peaceful hour was the most pleasurable in his solitary existence, and Ryan experienced more intimacy in his healing sessions with Indiana than he did in his strenuous sexual gymnastics with Jennifer Yang, the most regular of his lovers. He was a tall, heavyset man with the neck and shoulders of a wrestler, arms as thick and stout as tree trunks, and the delicate hands of a pastry chef. He had dark, close-cropped hair streaked with gray, teeth that seemed too white to be natural, pale gray eyes, a broken nose, and thirteen visible scars, including his stump. Indiana suspected he had other scars, but she hadn’t seen him without his boxer shorts. Yet.

“How do you feel?” the healer asked.

“Great. I’m starving, though—that’s probably because I smell like dessert.”

“That’s orange essential oil. If you’re just going to make fun, I don’t know why you bother coming.”

“To see you, babe, why else?”

“In that case, my therapies aren’t right for you,” Indiana snapped.

“You know I’m just kidding, Indi.”

“Orange oil is a youthful and happy essence—two qualities you seem to lack, Ryan. And I’ll have you know that Reiki is so powerful that second-degree practitioners are capable of ‘distance healing’; they can work without the patient even being present—though I’d probably need to spend twenty years studying in Japan to get to level two.”

“Don’t even think about distance healing. Without you here, this would be a lousy deal.”

“Healing is not a deal!”

“Everyone’s got to make a living. You charge less than your colleagues at the Holistic Clinic. Do you know how much Yumiko charges for a single acupuncture session?”

“I’ve no idea, and it’s none of my business.”

“Nearly twice as much as you,” said Ryan. “Why don’t you let me pay you more?”

“You’re my friend. I’d rather you didn’t pay at all, but if I didn’t let you pay, you probably wouldn’t come back. You won’t allow yourself to be in anyone’s debt. Pride is your great sin.”

“Would you miss me?”

“No, because we’d still see each other as friends. But I bet you’d miss me. Come on, admit it, these sessions have really helped. Remember how much pain you were in when you first came? Next week, we’ll do a session of magnet therapy.”

“And a massage, please. You’ve got the hands of an angel.”

“Okay, and a massage. Now get your clothes on, I’ve got another client waiting.”

“Don’t you find it weird that almost all your clients are men?” asked Ryan, clambering down from the massage table.

“They’re not all men—I treat women too, as well as a few children. And one arthritic poodle.”

Ryan was convinced that if Indiana’s other male clients were anything like him, they paid simply to be near her, not because they had any faith in her healing methods. This was what had first brought him to Treatment Room 8, something he admitted to Indiana during their third session so there would be no misunderstandings, and also because his initial attraction had blossomed into friendship. Indiana had burst out laughing—she was well used to come-ons—and made a bet with him that after two or three weeks, when he felt the results, he would change his mind. Ryan accepted the bet, suggesting dinner at his favorite restaurant. “If you can cure me, I’ll pick up the tab, otherwise dinner is on you,” he said, hoping to spend time with her somewhere more conducive to conversation than these two cramped cubicles, watched over by the omniscient Shakti.

Ryan and Indiana had met in 2009, on one of the trails that wound through Samuel P. Taylor State Park among thousand-year-old, three-hundred-foot-high trees. Indiana had taken her bicycle on the ferry across San Francisco Bay, and once in Marin County cycled the twenty or so miles to the park as part of her training for a long bike ride to Los Angeles she planned to make a few weeks later. As a rule, Indiana thought sports were pointless, and she had no particular interest in keeping fit; but her daughter, Amanda, was determined to take part in a charity bike ride for AIDS, and Indiana was not about to let her go alone.

She had just stopped the bike to take a drink from her water bottle, one foot on the ground, when Ryan raced past with Attila on a leash. She didn’t see the dog until it was practically on top of her; the shock sent her flying, and she ended up tangled in the bike frame. Ryan apologized, helped her to her feet, and tried to straighten the buckled wheel while Indiana dusted herself off. She was more concerned about Attila than with her own bumps and bruises. She’d never before seen such a disfigured animal: the dog had scars everywhere, bald patches on its belly, and two metallic fangs worthy of Dracula in an otherwise toothless maw; one of its ears was missing, as though hacked off with scissors. She stroked the animal’s head gently and leaned down to kiss its snout, but Ryan quickly jerked her away.

“Don’t get your face too close! Attila’s a war dog.”

“What breed is he?”

“Purebred Belgian Malinois. They’re smarter and stronger than German shepherds, and they keep their backs straight, so they don’t suffer from hip problems.”

“What on earth happened to the poor thing?”

“He survived a land-mine explosion,” Ryan said, dipping his handkerchief in the cold water of the river, where a week earlier he’d watched salmon leaping against the current in their arduous swim upstream to spawn. Miller handed Indiana the wet handkerchief to dab the grazes on her legs. He was wearing track pants, a sweatshirt, and something that looked like a bulletproof jacket—it weighed forty-five pounds, he explained, making it perfect for training because when he took it off to race, he felt like he was flying. They sat among the thick, tangled roots of a tree and talked, watched over by Attila, who studied Ryan’s every move as though waiting for an order and from time to time nuzzled Indiana and discreetly sniffed her. The warm afternoon, heady with the scent of pine needles and dead leaves, was lit by shafts of sunlight that pierced the treetops like spears; the air quivered with birdsong, the hum of mosquitoes, the lapping of the creek, and the wind in the leaves; it was the perfect setting for a meeting in a romantic novel.

Ryan had been a Navy SEAL—a former member of SEAL Team Six, the unit that in May 2011 launched the assault on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan. In fact, one of Ryan’s former teammates would be the one to kill the Al-Qaeda leader. When he and Indiana met, however, Ryan could not have known this would happen two years later; no one could, except perhaps Celeste Roko, by studying the movement of the planets. Ryan was granted an honorable discharge in 2007 after he lost a leg in combat—an injury that didn’t stop him continuing to compete as a triathlete, as he told Indiana. Up to this point she had scarcely looked at Ryan, focused as she was on the dog, but now she noticed that he wore only one shoe; his other leg ended in a curved blade.

“It’s called a Flex-Foot Cheetah—they model it on the way big cats run in the wild,” he explained, showing her the prosthesis.

“How does it fit?”

He hiked up the leg of his pants, and she studied the contraption fastened to the stump.

“It’s carbon fiber,” Ryan explained. “It’s so light and perfect that officials tried to stop Oscar Pistorius, a South African double amputee, from competing in the Olympics because they said his prostheses gave him an unfair advantage over other runners. This model is designed for running,” he went on, explaining with a certain pride that this was cutting-edge technology. “I’ve got other prosthetics for walking and cycling.”

“Doesn’t it hurt?”

“Sometimes. But there’s other stuff that hurts more.”

“Like what?”

“Things from my past. But that’s enough about me—tell me about you.”

“Sorry, but I haven’t got anything as interesting as a bionic leg,” Indiana confessed, “and I’ve only got one scar, which I’m not going to show you. As a kid, I fell on my butt on some barbed wire.”

Indiana and Ryan sat in the park, chatting about this and that under the watchful eye of Attila. She introduced herself—half joking, half serious—by telling him she was a Pisces, her ruling planet was Neptune, her lucky number 8, her element water, and her birthstones, silver-gray moonstone, which nurtures intuitive power, and aquamarine, which encourages visions, opens the mind, and promotes happiness. Indiana had no intention of seducing Ryan; for the past four years she had been in love with a man named Alan Keller and had chosen the path of fidelity. Had she wanted to seduce him, she would have talked about Shakti, goddess of beauty, sex, and fertility, since the mere mention of these attributes was enough to overcome the scruples of any man—Indiana was heterosexual—if her voluptuous body were not enough. Indiana never mentioned that Shakti was also the divine mother, the primordial life force, the sacred feminine—as these roles tended to put men off.

Usually Indiana didn’t tell men that she was a healer by profession; she had met her fair share of cynics who listened to her talk about cosmic energy with a condescending smirk while they stared at her breasts. But somehow she sensed she could trust this Navy SEAL, so she gave him a brief account of her methods, though when put into words they sounded less than convincing even to her ears. To Ryan it sounded more like voodoo than medicine, but he pretended to be interested—the information gave him a perfect excuse to see her again. He told her about the cramps he suffered at night, the spasms that could sometimes bring him to a standstill in the middle of a race. Indiana prescribed a course of therapeutic massage and a diet of banana and kiwifruit smoothies.

They were so caught up in the moment that the sun had already begun to set when Indiana realized that she was going to miss the ferry back to San Francisco. She jumped to her feet and said good-bye, but Ryan, explaining that his van was just outside the park, offered to give her a ride—after all, they lived in the same city. The van had a souped-up engine, oversize wheels, a roof rack, a bicycle rack, and a tasseled pink velvet cushion for Attila that neither Ryan nor his dog had chosen—Ryan’s girlfriend Jennifer Yang had given it to him in a fit of Chinese humor.

Three days later, unable to get Indiana out of his mind, Ryan turned up at the Holistic Clinic just to see the woman with the bicycle. She was the polar opposite of the usual subjects of his fantasies: he preferred slim Asian women like Jennifer Yang, who besides having perfect features—ivory skin, silken hair, and a bone structure to die for—was also a high-powered banker. Indiana, on the other hand, was a big-boned, curvaceous, good-hearted typical American girl of the type that usually bored him. Yet for some inexplicable reason he found her irresistible. “Creamy and delicious” was how he described her to Pedro Alarcón, adjectives more appropriate to high-cholesterol food, as his friend pointed out. Shortly after Ryan introduced them, Alarcón commented that Indiana, with her ample diva’s bosom, her blond mane, her sinuous curves and long lashes, had the larger-than-life sexiness of a gangster’s moll from a 1970s movie, but Ryan didn’t know anything about the goddesses who’d graced the silver screen before he was born.

Ryan was somewhat surprised by the Holistic Clinic—having expected a sort of Buddhist temple, he found himself standing in front of a hideous three-story building the color of guacamole. He didn’t know that it had been built in 1940 and for years attracted tourists who flocked to admire its art-deco style and its stained-glass windows, inspired by Gustav Klimt, but that in the earthquake of 1989 its magnificent facade had collapsed. Two of the windows had been smashed, and the remaining two had since been auctioned off, to be replaced with those tinted glass windows the color of chicken shit favored by button factories and military barracks. Meanwhile, during one of the building’s many misguided renovations, the geometric black-and-white-tiled floor had been replaced with linoleum, since it was easier to clean. The decorative green granite pillars imported from India and the tall lacquered double doors had been sold to a Thai restaurant. All that remained of the clinic’s former glory was the wrought-iron banister on the stairs and two period lamps that, if they had been genuine Lalique, would probably have suffered the same fate as the pillars and the doors. The doorman’s lodge had been bricked up, and twenty feet lopped off the once bright, spacious lobby to build windowless, cavelike offices. But as Ryan arrived that morning, the sun shimmered on the yellow-gold windows, and for a magical half hour the space seemed suspended in amber, the walls dripping caramel and the lobby fleetingly recovering some of its former splendor.

Ryan went up to Treatment Room 8, prepared to agree to any therapy, however bizarre. He half expected to see Indiana decked out like a priestess; instead she greeted him wearing a white coat and a pair of white clogs, her hair pulled back into a ponytail and tied with a scrunchie. There was nothing of the sorceress about her. She got him to fill out a detailed form, then took him back out into the corridor and had him walk up and down to study his gait. Only then did she tell him to strip down to his boxer shorts and lie on the massage table. Having examined him, she discovered that one of his hips was slightly higher than the other, and his spine had a minor curvature—unsurprising in a man with only one leg. In addition she diagnosed an energy blockage in the sacral chakra, knotted shoulder muscles, tension and stiffness in the neck, and an exaggerated startle reflex. In a word, he was still a Navy SEAL.

Indiana assured him that some of her therapies would be helpful, but that if he wanted them to be successful, he had to learn to relax. She recommended acupuncture sessions with Yumiko Sato, two doors down, and without waiting for him to agree, picked up the phone and made an appointment for him with a Qigong master in Chinatown, five blocks from the Holistic Clinic. It was only to humor her that Ryan agreed to these therapies, but in both cases he was pleasantly surprised.

Yumiko Sato, a person of indeterminate age and gender who had close-cropped hair like his own, thick glasses, a dancer’s delicate fingers, and a sepulchral serenity, took his pulse and arrived at the same diagnosis as Indiana. Ryan was advised that acupuncture could be used to treat his physical pain, but it would not heal the wounds in his mind. He flinched, thinking he had misheard. The phrase intrigued him, and some months later, after they had established a bond of trust, he asked Yumiko what she had meant. Yumiko Sato said simply that only fools have no mental wounds.

Ryan’s Qigong lessons with Master Xai—who was originally from Laos and had a beatific face and the belly of a Laughing Buddha—were a revelation: the perfect combination of balance, breathing, movement, and meditation. It was the ideal exercise for body and mind, and Ryan quickly incorporated it into his daily routine.

Indiana didn’t manage to cure the spasms within three weeks as promised, but Ryan lied so he could take her out and pay for dinner, since by then he’d realized that financially she was bordering on poverty. The bustling yet intimate restaurant, the French-influenced Vietnamese food, and the bottle of Flowers pinot noir all played a part in cementing a friendship that in time Ryan would come to think of as his greatest treasure. He had lived his life among men. The fifteen Navy SEALs he’d trained with when he was twenty were his true family; like him they were inured to rigorous physical exertion, to the terror and exhilaration of war, to the tedium of hours spent idle. Some of his comrades, he had not seen in years, others he had seen only a few months earlier, but he kept in touch with them all; they would always be his brothers.

Before he lost his left leg, the navy vet’s relationships with women had been uncomplicated: sexual, sporadic, and so brief that the features of these women blurred into a single face that looked not unlike Jennifer Yang’s. They were usually just flings, and when from time to time he did fall for someone, the relationship never lasted. His life—constantly on the move, constantly fighting to the death—did not lend itself to emotional attachments, much less to marriage and children. He fought a constant war against his enemies, some real, others imaginary; this was how he had spent his youth.

In civilian life Ryan was awkward, a fish out of water. He found it difficult to make small talk, and his long silences sometimes seemed insulting to people who didn’t know him well. The fact that San Francisco was the center of a thriving gay community meant it was teeming with beautiful, available, successful women very different from the girls Ryan was used to encountering in dive bars or hanging around the barracks. In the right light, Ryan could easily pass for handsome, and his disability—aside from giving him the martyred air of a man who has suffered for his country—offered a good excuse to strike up a conversation. He was never short of offers, but when he was with the sort of intelligent woman he found attractive, he worried so much about making a good impression that he ended up boring them. No California woman would rather spend the evening listening to war stories, however heroic, than go clubbing—no one, that is, except Jennifer Yang, who had inherited not only the infinite patience of her ancestors in the Celestial Empire but also the ability to pretend she was listening when actually she was thinking about something else. Yet from the very first time they met among the sequoias in Samuel P. Taylor State Park, Ryan had felt comfortable with Indiana Jackson. A few weeks later, at the Vietnamese restaurant, he realized he didn’t need to rack his brains for things to talk about; half a glass of wine was all it took to loosen Indiana’s tongue. The time flew by, and when he checked his watch, Ryan saw it was past midnight and the only other people in the restaurant were two Mexican waiters clearing tables with the disgruntled air of men who had finished their shift and were anxious to get home. It was on that night, three years ago, that Ryan and Indiana had become firm friends.

For all his initial skepticism, after three or four months the ex-soldier was forced to admit that Indiana was not just some crazy New Age hippie; she genuinely had the gift of healing. Her therapies relaxed him; he slept more soundly, and the cramps and spasms had all but disappeared. But the most wonderful thing about their sessions together was the peace they brought him: her hands radiated affection, and her sympathetic presence stilled the voices from his past.

As for Indiana, she came to rely on this strong, silent friend, who kept her fit by forcing her to jog the endless paths and forest trails in the San Francisco area, and bailed her out when she had financial problems and couldn’t bring herself to approach her father. They got along well, and though the words were never spoken, she sensed that their friendship might have blossomed into a passionate affair if she wasn’t still hung up on her elusive lover Alan, and Ryan wasn’t so determined to push away love in atonement for his sins.

The summer her mother met Ryan Miller, Amanda Martín had been fourteen, though she could have passed for ten. She was a skinny, gawky girl with thick glasses and a retainer who hid from the unbearable noise and glare of the world behind her mop of hair or the hood of her sweatshirt; she looked so unlike her mother that people often asked if she was adopted. From the first, Ryan treated Amanda with the exaggerated courtesy of a Japanese gentleman. He made no effort to help her during their long bike ride to Los Angeles, although, being an experienced triathlete, he had helped her to train and prepare for the trip, something that won him the girl’s trust.

One Friday morning at seven, all three of them—Indiana, Amanda, and Ryan—set off from San Francisco with two thousand other keen cyclists wearing red AIDS awareness ribbons, escorted by a procession of cars and trucks filled with volunteers transporting tents and provisions. They arrived in Los Angeles the following Friday, their butts red-raw, their legs stiff, and their minds as free of thoughts as newborn babes. For seven days they had pedaled up hills and along highways, through stretches of beautiful countryside and others of hellish traffic. To Ryan—for whom a daily fifteen-hour bike ride was a breeze—the ride was effortless, but to mother and daughter it felt like a century of agonizing effort, and they only got to the finish line because Ryan was there, goading them like a drill sergeant whenever they flagged and recharging their energy with electrolyte drinks and energy bars.

Every night, like an exhausted flock of migrating birds, the two thousand cyclists descended on the makeshift campsites erected by the volunteers along the route, wolfed down five thousand calories, checked their bicycles, showered in trailers, and rubbed their calves and thighs with soothing ointment. Before they went to sleep, Ryan applied hot compresses to Indiana and Amanda and gave them little pep talks about the benefits of exercise and fresh air.

“What has any of this got to do with AIDS?” asked Indiana on the third day, having cycled for ten hours, weeping from sheer exhaustion and for all the woes in her life. “What do I know?” was Ryan’s honest answer. “Ask your daughter.”

The ride may have made only a modest contribution to the fight against AIDS, but it cemented the budding friendship between Ryan and Indiana, while for Amanda it led to something impossible: a new friend. This girl, who looked set to become a hermit, had precisely three friends in the world: her grandfather, Blake Jackson; Bradley, her future boyfriend; and now Ryan Miller, the Navy SEAL. The kids she played Ripper with didn’t fall into the same category; she only knew them within the context of the game, and their relationship was entirely centered around crime.

Tuesday, 3 (#ulink_80c0e220-29d5-5350-9bfd-47bc8f75c8a7)

Amanda’s godmother, Celeste Roko, the most famous astrologer in California, made her “bloodbath” prediction the last day of September 2011. Her daily show aired early, before the morning weather forecast, and repeated after the evening news. At fiftysomething, thanks to a little nip and tuck, Roko looked good for her age. Charming on screen and a dragon in person, she was considered beautiful and elegant by her many admirers. She looked like Eva Perón with a few extra pounds. The set for her TV show featured a blown-up photo of the Golden Gate Bridge behind a fake picture window and a huge model of the solar system, with planets that could light up and be moved by remote control.

Psychics, astrologers, and other practitioners of the mysterious arts tend to make their predictions on New Year’s Eve, but Madame Roko could not bring herself to wait three months before warning the citizens of San Francisco of the horrors that lay in store for them. Her prophecy was of such magnitude that it captured the public imagination, went viral on the Internet. Her pronouncement provoked scathing editorials in the local press and hysterical headlines in the tabloids, speculating about terrible atrocities at San Quentin State Prison, gang warfare between blacks and Latinos, and an apocalyptic earthquake along the San Andreas Fault. But Celeste Roko, who exuded an air of infallibility thanks to a former career as a Jungian analyst and an impressive number of accurate predictions, was adamant that her vision concerned murders. This provoked a collective sigh of relief among devotees of astrology, since it was the least dreadful of the calamities they had feared. In northern California, the chance of being murdered was one in twenty thousand; it was, everyone believed, a crime that happened to other people.

It was on the day of this prediction that Amanda and her grandfather finally decided to challenge the power of Celeste Roko. They were sick and tired of the influence Amanda’s godmother wielded over the family by pretending that she could foretell the future. Madame Roko was a temperamental woman with the unshakable belief in herself common to those who receive direct messages from the universe or from God. She never managed to sway Blake Jackson, who would have no truck with astrology, but Indiana always consulted Celeste before making important decisions, allowing her life to be guided by the dictates of her horoscope. All too often Celeste Roko’s astrological readings thwarted Amanda’s best-laid plans. When she was younger, for example, the planets had deemed it an inauspicious moment to buy a skateboard but a propitious time to take up ballet—which left Amanda in a pink tutu, sobbing with humiliation.

When she turned thirteen, Amanda discovered that her godmother was not in fact infallible. The planets had apparently decided that Amanda should go to a public high school, but Encarnación Martín, her formidable paternal grandmother, insisted she attend a Catholic boarding school. For once Amanda sided with Celeste, since a co-ed school seemed slightly less terrifying than being taught by nuns. But Doña Encarnación triumphed over Celeste Roko—by producing a check for the tuition fees. Little did she suspect that the nuns would turn out to be feminists in pants who challenged the pope, and used science class to demonstrate the correct use of a condom with the aid of a banana.

Encouraged by the skepticism of her grandfather, who rarely dared to directly challenge Celeste, Amanda questioned the relationship between the heavenly bodies and the fates of human beings; to her, astrology seemed as much mumbo-jumbo as her mother’s white magic. Celeste’s most recent prognostication offered grandfather and granddaughter a perfect opportunity to refute the predictive powers of the stars. It is one thing to announce that the coming week is a favorable one for letter-writing, quite another to predict a bloodbath in San Francisco. That’s not something that happens every day.

When Amanda, her grandfather, and her online buddies transformed Ripper from a game into a criminal investigation, they could never have imagined what they were getting themselves into. Precisely eleven days after Celeste Roko’s pronouncement, Ed Staton was murdered. This might have been considered a coincidence, but given the unusual nature of the crime—the baseball bat—Amanda began to put together a case file using information published in the papers, what little she managed to wheedle out of her father, who was conducting the investigation, and whatever her grandfather could dig up.

Blake Jackson was a pharmacist by profession, a book lover, and a frustrated writer until he finally took the opportunity to chronicle the tumultuous events predicted by Celeste Roko. In his novel, he described his granddaughter Amanda as “idiosyncratic of appearance, timorous of character, but magnificent of mind”—his baroque use of language distinguishing him from his peers. His account of these fateful events would end up being much longer than he expected, even though—excepting a few flashbacks—it spanned a period of only three months. The critics were vicious, dismissing his work as magical realism—a literary style deemed passé—but no one could prove he had distorted the events to make them seem supernatural, since the San Francisco Police Department and the daily newspapers documented them.

In January 2012, Amanda Martín was sixteen and a high school senior. As an only child, Amanda had been dreadfully spoiled, but her grandfather was convinced that when she graduated from high school and went out into the world that would sort itself out. She was vegetarian now only because she didn’t have to cook for herself; when she was forced to do so, she would be less persnickety about her diet. From an early age Amanda had been a passionate reader, with all the dangers such a pastime entails. Although the San Francisco murders would have been committed in any case, Amanda would not have been involved if an obsession with Scandinavian crime novels had not developed into a morbid interest in evil in general and premeditated murder in particular. Though her grandfather was no advocate of censorship, it worried him that Amanda was reading books like this at fourteen. His granddaughter put him in his place by reminding him that he was reading them too, so all Blake Jackson could do was give her a stern warning about their content—which of course made her all the more curious. The fact that Amanda’s father was deputy chief of the homicide detail in San Francisco’s Personal Crimes Division fueled her obsession; through him she discovered how much evil there was in this idyllic city, which could seem immune to it. But if heinous crimes happened in enlightened countries like Sweden and Norway, there was no point in expecting things to be different in San Francisco—a city founded by rapacious prospectors, polygamous preachers, and women of easy virtue, all lured by the gold rush of the mid-nineteenth century.

Amanda went to an all-girls boarding school—one of a handful that still remained since America had opted for the muddle of mixed education—at which she had somehow survived for four years by managing to be invisible to her classmates, although not to the teachers and the few nuns who still worked there. She had an excellent grade-point average, although the sainted sisters never saw her open a textbook and knew she spent most nights staring at her computer, engrossed in mysterious games, or reading unsavory books. They never dared to ask what she was reading so avidly, suspecting that she read the very books they enjoyed in secret. Only the girl’s questionable reading habits could explain her morbid fascination for guns, drugs, poison, autopsies, methods of torture, and means of disposing of dead bodies.

Amanda closed her eyes and took a deep breath of fresh winter-morning air. The smell of pine needles told her that they were driving through the park; the stench of dung, that they were passing the riding stables. Thus she could calculate that it was exactly 8:23 a.m. She had given up wearing a watch two years earlier so she could train herself to tell time instinctively, the same way she calculated temperature and distance; she’d also refined her sense of taste so that she could distinguish suspect ingredients in her food. She cataloged people by scent: her grandfather, Blake, smelled of gentleness—a mixture of wool sweaters and chamomile; Bob, her father, of strength—metal, tobacco, and aftershave; Bradley, her boyfriend, of sensuality, sweat and chlorine; and Ryan smelled of reliability and confidence, a doggy aroma that was the most wonderful fragrance in the world. As for her mother Indiana, steeped in the essential oils of her treatment room, she smelled of magic.

After her grandfather’s spluttering ’95 Ford passed the stables, Amanda mentally counted off three minutes and eighteen seconds, then opened her eyes and saw the school gates. “We’re here,” said Jackson, as though this fact might have escaped her notice. Her grandfather, who kept fit playing squash, took Amanda’s heavy schoolbag and nimbly bounded up to the second floor while she trudged after him, violin in one hand, laptop in the other. The dorm room was deserted: since the new semester did not begin until tomorrow morning, the rest of the boarders would not be back from Christmas vacation until tonight. This was another of Amanda’s manias: wherever she went, she had to be the first to arrive so she could reconnoiter the terrain before potential enemies showed up. Amanda found it irritating to have to share the dorm room with others—their clothes strewn across the floor, their constant racket; the smells of shampoo, nail polish, and stale candy; the girls’ incessant chatter, their lives like some corny soap opera filled with jealousy, gossip, and betrayal from which she felt excluded.

“My dad thinks that Ed Staton’s murder was some sort of gay revenge killing,” Amanda told her grandfather before he left.

“What’s he basing that theory on?”

“On the baseball bat shoved—you know where,” Amanda said, blushing to her roots as she thought of the video she’d seen online.

“Let’s not jump to conclusions, Amanda. There’s still a lot we don’t know.”

“Exactly. Like, how did the killer get in?”

“Ed Staton was supposed to lock the doors and set the alarm when he started his shift,” said Blake. “Since there was no sign of forced entry, we have to assume the killer hid in the school before Staton locked up.”

“But if the murder really was premeditated, why didn’t the guy kill Staton before he drove off? He couldn’t have known Staton intended to come back.”

“Maybe it wasn’t premeditated. Maybe someone sneaked into the school intending to rob the place, and Staton caught him in the act.”

“Dad says that in all the years he’s worked in homicide, though he’s seen murderers who panicked and lashed out violently, he’s never come across a murderer who took the time to hang around and cruelly humiliate his victim.”

“What other pearls of wisdom did Bob come up with?”

“You know what Dad’s like—I have to surgically extract every scrap of information from him. He doesn’t think it’s an appropriate subject for a girl my age. Dad’s a troglodyte.”

“He’s got a point, Amanda. This whole thing is a bit sordid.”

“It’s public domain, it was on TV, and if you think you can handle it, there’s a video on the Internet some little girl shot on her cell phone.”

“Jeez, that’s cold-blooded. Kids these days are so used to violence that nothing scares them. Now, back in my day . . .” Jackson trailed off with a sigh.

“This is your day! It really bugs me when you talk like an old man. So, have you checked out the juvenile detention center, Kabel?”

“I’ve got work to do—I can’t just leave the drugstore unattended. But I’ll get to it as soon as I can.”

“Well, hurry up, or I might just find myself a new henchman.”

“You can try! I’d like to see anyone else who’s prepared to put up with you.”

“You love me, Gramps?”

“Nope.”

“Me neither,” Amanda said, and flung her arms around his neck.

Blake Jackson buried his nose in his granddaughter’s mane of frizzy hair, which smelled of salad—she washed it with vinegar—and thought about the fact that in a few months she would be off to college, and he would no longer be around to protect her. He missed her already, and she had not even left yet. He flicked through fleeting memories of her short life, back to an image of the sullen, skeptical little girl who would spend hours hiding in a makeshift tent of bedsheets where no one was admitted except Save-the-Tuna, the invisible friend who followed her around for years, her cat Gina, and sometimes Blake himself, when he was lucky enough to be invited to drink make-believe tea from tiny plastic cups.

Where on earth does she get it from? Blake Jackson had wondered when Amanda—aged six—first beat him at chess. It could hardly be from Indiana, who floated in the stratosphere preaching love and peace half a century after the hippies had died out, and it wasn’t from Bob Martín, who had never finished a book in his life. “I wouldn’t worry too much about it,” said Celeste Roko, who had a habit of showing up unannounced, and who terrified Blake Jackson almost as much as the devil himself. “Lots of kids are precocious at that age, but it doesn’t last. Just wait till her hormones kick in, and she’ll nosedive to the usual level of teenage stupidity.”

But in this case the psychic had been wrong: Amanda’s intelligence had continued to develop throughout her teenage years, and the only impact her hormones had was on her appearance. At puberty she grew quickly, and at fifteen she got contact lenses to replace her glasses, had her retainer removed, learned to tame her shock of curly hair, and emerged as a slim young woman with delicate features, her father’s dark hair, and her mother’s pale skin, a young woman who had no idea how beautiful she was. At seventeen she still shambled along, still bit her nails, and still dressed in bizarre castoffs she bought in thrift stores and accessorized according to her mood.

When her grandfather left, Amanda felt, for a few hours at least, that she was master of her own space. Three months from now she’d graduate from high school—where she’d been happy, on the whole, despite the frustration of having to share a dorm room—and soon she’d be heading for Massachusetts, to MIT, where her virtual boyfriend, Bradley, was already enrolled. He’d told her all about the MIT Media Lab, a haven of imagination and creativity, everything she had ever dreamed of. Bradley was the perfect man: he was a bit of a geek, like her, had a quirky sense of humor and a great body. His broad shoulders and healthy tan, he owed to being on the swim team; his fluorescent yellow hair to the strange cocktail of chemicals in swimming pools. He could easily pass for Australian. Sometime in the distant future Amanda planned to marry Bradley, though she hadn’t told him this yet. In the meantime, they hooked up online to play Go, talked about hermetic subjects and about books.

Bradley was a science-fiction fan—something Amanda found depressing; more often than not science fiction involved a universe where the earth had been reduced to rubble and machines controlled the population. She’d read a lot of science fiction between the ages of eight and eleven before moving on to fantasy—imaginary eras with little technology where the difference between heroes and villains was clear—a genre Bradley considered puerile and pernicious. He preferred bleak dystopias. Amanda didn’t dare tell him that she’d read all four Twilight novels and the Millennium trilogy; Bradley had no time for vampires and psychopaths.

Their romantic e-mails full of virtual kisses were also heavily laced with irony so as not to seem soppy; certainly nothing explicit. The Reverend Mother had expelled a classmate of Amanda’s the previous December for uploading a video of herself naked, spread-eagled, and masturbating. Bradley had not been particularly shocked by the story, since some of his buddies’ girlfriends had made similar sex tapes. Amanda had been a little surprised to discover that her friend was completely shaven, and that she’d made no attempt to hide her face, but she was more shocked by the hysterical reaction of the nuns, who had the reputation of being tolerant.

While she messaged Bradley online, Amanda filed away the information her grandfather had managed to dig up on the Case of the Misplaced Baseball Bat, along with a number of grisly press cuttings she’d been collecting since her godmother first broadcast her grim prophecy. The kids who played Ripper were still trying to come up with answers to several questions about Ed Staton, but already Amanda was preparing a new dossier for their next case: the murders of Doris and Michael Constante.

Matheus Pereira, a painter of Brazilian origin, was another of Indiana Jackson’s admirers. But their love was strictly platonic, since Matheus devoted all his energies to his painting. Matheus believed that artistic creativity was fueled by sexual energy, and when forced to choose between painting and seducing Indiana—who didn’t seem interested in an affair—he chose the former. In any case, marijuana kept him in a permanent state of zoned-out bliss that didn’t lend itself to amorous schemes. Matheus and Indiana were close friends; they saw each other most days, and they looked out for each other. He was constantly harassed by the police, while she sometimes had problems with clients who got too fresh, and with Deputy Chief Martín, who felt he still had the right to interfere in his ex-wife’s affairs.

“I’m worried about Amanda,” Indiana said as she massaged Matheus with eucalyptus oil to relieve his sciatica. “Her new obsession is crime.”

“So she’s over the whole vampire thing?”

“That was last year. But this is more serious—she’s fixated on real-life crimes.”

“She’s her father’s daughter.”

“I never know what she’s up to. That’s the problem with the Internet—some pervert could be grooming my daughter right now, and I’d be the last to know.”

“It’s not like that, Indi. They’re just a bunch of kids playing games. By the way, I saw Amanda in Café Rossini last Saturday, having breakfast with your ex-husband. I swear that guy’s got it in for me, Indi.”

“No, he hasn’t. Bob’s pulled strings to keep you out of jail more than once.”

“Only because you asked him. Anyway, like I was saying, Amanda and I chatted for a bit, and she told me about their role-playing game, Ripper. Did you know that in one of the murders, the killer shoved a bat—”

“Yes, Matheus, I do know,” Indiana interrupted. “But that’s just what I mean—do you really think it’s healthy for Amanda to be obsessed with gruesome things like that? Most girls her age have crushes on movie stars.”

Matheus Pereira lived in an unauthorized extension on the flat roof of the Holistic Clinic, and in practice he also acted as the building supervisor. This ramshackle shed that he called his studio got exceptionally good light for painting and for growing marijuana—which was purely for his personal use and that of his friends.

In the late 1990s, after passing through various hands, the building had been sold to a Chinese businessman with a good eye for an investment, who had the idea of turning it into one of the health and wellness centers flourishing all over California. He had the exterior painted and hung up a sign that read HOLISTIC CLINIC to distinguish it from the fishmongers in Chinatown. The people to whom he rented the units on the second and third floors, all practitioners of the healing arts and sciences, did the rest of the work. A yoga studio and an art gallery occupied the two ground-floor units. The former also offered popular tantric dance classes, while the latter—inexplicably called the Hairy Caterpillar—mounted exhibitions of work by local artists. On Friday and Saturday nights, musicians and arty types thronged the gallery, sipping complimentary acrid wine from paper cups. Anyone looking for illicit drugs could buy them at the Hairy Caterpillar at bargain prices right under the noses of the police, who tolerated low-level trafficking as long as it was done discreetly. The two top floors of the Holistic Clinic were subdivided into small consulting suites that comprised a waiting room barely big enough for a school desk and a couple of chairs, and a treatment room. Access to the treatment rooms was somewhat restricted by the fact there was no elevator in the building—a major drawback to some patients, but one that had the advantage of discouraging the seriously ill, who were unlikely to get much benefit from alternative medicine.

Matheus Pereira had lived in the building for thirty years, successfully resisting every attempt by the previous owners to evict him. The Chinese businessman didn’t even try—it suited him to have someone in the building outside office hours, so he appointed Matheus building supervisor, giving him master keys to the units and paying him a notional salary to lock up at night, turn out the lights, and act as a contact for tenants in case of emergency or if any repairs were needed.

Matheus exhibited his paintings—inspired by German Expressionism—at the Hairy Caterpillar from time to time, though they never sold. A few of his canvases also hung in the lobby, and though the anguished, misshapen figures painted in thick angry brushstrokes clashed not only with the Holistic Clinic’s last vestiges of art deco but with its new ethos of promoting physical and emotional well-being in its clients, no one dared suggest taking them down for fear of offending the artist.

“This is all down to your ex-husband, Indi,” Matheus said as he was leaving. “Where else do you think Amanda gets her morbid fascination with crime?”

“Bob’s as worried about Amanda’s new obsession as I am.”

“It could be worse, she could be taking drugs—”

“Look who’s talking!” Indiana laughed.

“Exactly! I’m an expert.”

“If you want, I can give you a ten-minute massage tomorrow between clients,” Indiana offered.

“You’ve been giving me free massages for years now, so I’ve decided—I want you to have one of my canvases!”

“No, no, Matheus!” said Indiana, managing to disguise the rising panic in her voice. “I couldn’t possibly accept. I’m sure one day your paintings will be very valuable.”

Wednesday, 4 (#ulink_7d03d7c2-43bc-5e68-9bc2-4d4e43f80685)

At 10:00 p.m., Blake Jackson finished the novel he’d been reading and went into the kitchen to fix himself some oatmeal porridge—something that brought back childhood memories and consoled him when he felt overwhelmed by the stupidity of the human race. Some novels left him feeling this way. Wednesday evenings were usually reserved for squash games, but his squash partner was on vacation this week. Blake sat down with his bowl of oatmeal, inhaling the delicate aroma of honey and cinnamon, and dialed Amanda’s cell phone number. He wasn’t worried about waking her, knowing that at this hour she would be reading. Since Indiana’s bedroom was some distance from the kitchen, there was no chance that she would overhear, but still Blake Jackson found himself whispering. It was best his daughter didn’t know what he and his granddaughter were up to.

“Amanda? It’s Kabel.”

“I recognized the voice. So, what’s the story?”

“It’s about Ed Staton. Making the most of the unseasonably warm weather—it was seventy degrees today, it felt like summer—”

“Get to the point, Kabel, I don’t have all night to chat about global warming.”

“ . . . I went for a beer with your dad and discovered a few things I thought might interest you.”

“What things?”

“The juvenile detention center where Staton worked before he moved to San Francisco was a place called Boys’ Camp, smack in the middle of the Arizona desert. He worked there for a couple years until he got canned in 2010 in a scandal involving the death of a fifteen-year-old kid. And it wasn’t the first time, Amanda—three boys have died at the facility in the past eight years, but it’s still open. Every time, the judge has simply suspended its license temporarily for the duration of the investigation.”

“Cause of death?”

“A military-style regime enforced by people who were either stupid or sadistic. A catalog of neglect, abuse, and torture. These boys were beaten, forced to exercise until they passed out, deprived of food and sleep. The boy who died in 2010 had contracted pneumonia; he was running a temperature and had collapsed more than once, and still they forced him to go on a run with the other inmates in the blazing, sweltering Arizona heat. When he collapsed, they kicked him while he was on the ground. He spent two weeks in the hospital before he died. Afterward, they discovered he had a couple of quarts of pus in his lungs.”

“And Ed Staton was one of these sadists,” concluded Amanda.

“He had a long record at Boys’ Camp. His name crops up in a number of complaints made against the facility, alleging abuse of inmates, but it wasn’t until 2010 that they fired him. Seems nobody gave a damn what happened to those poor boys. It’s like that Charles Dickens novel—”

“Oliver Twist. Come on, Kabel, cut to the chase.”

“So, anyway, they tried to hush up Staton’s dismissal, but they couldn’t—the boy’s death stirred up a hornet’s nest. But even with his reputation, Staton still managed to get a job at Golden Hills Elementary School in San Francisco. Doesn’t that seem weird to you? I mean, they must have been aware of his record.”

“Maybe he had the right connections.”

“No one took the trouble to look into his background. The principal at Golden Hills liked the guy because he knew how to enforce discipline, but a number of students and teachers I talked to said he was a bully, one of those candy-asses who grovel to their superiors and become viciously cruel the moment they get a little power. The world’s full of guys like that, unfortunately. In the end, the principal put him on the night shift to avoid any trouble. Staton’s shift ran from eight p.m. to six a.m.”

“Maybe he was killed by someone he’d bullied at this Boys’ Camp.”

“Your dad’s looking into the possibility, though he’s still clinging to the theory that the murder is gay-related. Staton was into gay porn, and he used hustlers.”

“What?”

“Hustlers—male prostitutes. Staton’s regular partners were two young Puerto Rican guys—your dad questioned them, but they’ve got solid alibis. Oh, and about the alarm in the school, you can tell the Ripper kids Staton was supposed to set it every night, only on the night in question he didn’t. Maybe he was in a hurry, maybe he planned to set it after he got back.”

“I know you’re still holding out on me,” Amanda said.

“Me?”

“Come on, Kabel, spit it out.”

“It’s something pretty weird—even your dad’s stumped by it,” said Blake Jackson. “The school gym is full of equipment—baseball bats, gloves, balls—but the bat used on Staton didn’t come from the school.”

“Don’t tell me: the bat was from some team in Arizona!”

“Like the Arizona Devils? That would make the connection to Boys’ Camp obvious, Amanda, but it didn’t.”

“So where did it come from?”

“Arkansas State University.”

According to Celeste Roko, who had studied the astrological charts of all of her friends and relatives, Indiana Jackson’s personality corresponded to her star sign, Pisces. This, she felt, explained her interest in the esoteric and her irrepressible need to help out every unfortunate wretch she encountered—including those who neither wanted nor appreciated her help. This made Carol Underwater the perfect focus for Indiana’s indiscriminate bursts of compassion.

The two women had met one morning in December 2011. Indiana was locking up her bike and, out of the corner of her eye, noticed a woman leaning against a nearby tree as though she was about to faint. Indiana rushed over, offered the woman a shoulder to lean on, led her to the Holistic Clinic, and helped her up the two flights of stairs to Treatment Room 8, where the stranger slumped, exhausted, into one of the rickety chairs in the waiting room. After she got her breath back, the woman introduced herself and explained that she was suffering from an aggressive form of cancer and that the chemotherapy was proving worse than the disease. Touched, Indiana offered to let the woman lie down on the massage table and rest for a while. In a tremulous voice, Carol Underwater said she was fine in the chair but that she would be grateful for a hot drink. Indiana left the woman and went down the street to buy a herbal tea, feeling bad that there wasn’t a hot plate in the consulting room so she could boil water. When she got back, she found that the woman had recovered a little and even put on brick-red lipstick in a pathetic attempt to smarten herself up. Pale and ravaged by the cancer, Carol Underwater looked simply grotesque, her eyes standing out like glass buttons on a rag doll. She told Indiana she was thirty-six, but the wig and the deep furrows made her look ten years older.

So began a relationship based on Carol Underwater’s misfortune and Indiana’s need to play the Good Samaritan. Indiana often offered therapies to bolster Carol’s immune system, but she always managed to find some excuse for postponing them. At first, suspecting the woman couldn’t afford to pay, Indiana offered the treatments for free, as she often did with patients in straitened circumstances, but when Carol continued to find excuses, Indi did not insist; she knew better than anyone that many people still distrusted alternative medicine.

The women shared a taste for sushi, walks in the park, and romantic comedies, and were both concerned about animal welfare. Carol—like Amanda—was a vegetarian but made an exception with sushi, while Indiana was happy just to protest against the suffering endured by battery hens and laboratory rats and the fashion industry’s use of fur. One of her favorite organizations was PETA, which a year earlier had petitioned the mayor of San Francisco to change the name of the Tenderloin district: it was inexcusable that a neighborhood should be named after a prime cut from some suffering animal; the area should be renamed after a vegetable. The mayor did not respond.

Despite the things they had in common, Indiana and Carol’s relationship was somewhat strained, with Indiana feeling she had to keep a certain distance, lest Carol stick to her like dandruff. The woman felt helpless and forsaken; her life was a catalog of rejections and disappointments. Carol saw herself as boring, with no charm, no talent, and few social skills, and suspected that her husband had only married her to get a green card. Indiana gently advised that she needed to rewrite this script that cast her as the victim, since the first step toward healing was to rid oneself of negative energy and bitterness. Instead, Indiana suggested, Carol needed a positive script, one that connected her to the oneness of the universe and to the divine light, but still Carol clung to her misfortune. Indiana sometimes worried she might be sucked into the bottomless chasm of this woman’s need: Carol phoned Indiana at all hours to whine, and waited outside her treatment room for hours to bring her expensive chocolates that clearly represented a sizable percentage of her social security check. Indiana would politely eat these, counting every calorie and with no real pleasure, since she preferred the dark chocolates flecked with chili that she shared with Alan.

Carol had no children and no family, but she did have a couple of friends Indiana never met who accompanied her to the chemotherapy sessions. Carol’s only topics of conversation were her cancer and her husband, a Colombian deported for drug dealing whom she was trying to bring back to the States. The cancer itself caused her no pain, but the poison being dripped into her veins was killing her. Carol’s skin was deathly pale, she had no energy, and her voice quavered, but Indiana nurtured the hope that she might recover—her scent was different from that of the other cancer patients Indi had treated. What’s more, Indiana’s customary ability to tune in to other people’s illnesses didn’t work with Carol, something she took as a positive sign.

One day, as they were discussing this at the Café Rossini, Carol talked about her fear of dying and her hopes that Indiana would help her—a burden Indiana felt unable to take on.

“You’re a very spiritual person, Indi,” Carol said.

Indiana laughed. “Don’t call me that! The only people I know who claim to be spiritual are sanctimonious and steal books about the occult from bookstores.”

“Do you believe in reincarnation?” Carol asked.

“I believe in the immortality of the soul.”

“I’ve frittered away this life, so if reincarnation really does exist, I’ll come back as a cockroach.”

Indiana lent Carol some books she always kept at her bedside, an eclectic mixture of tomes about Sufism, Platonism, Buddhism, and contemporary psychology, though she didn’t tell the woman that she herself had been studying for nine years and had only recently taken the first steps on the long path to enlightenment; for her to attain “plenitude of being,” and rid her soul of conflict and suffering, would take eons. Indiana hoped that her instincts as a healer would not fail her; that Carol would survive her battle with cancer and have time enough in this world to achieve the enlightenment she sought.

On that Wednesday in January, one of Indiana’s clients had canceled a Reiki and aromatherapy session, so she and Carol arranged to meet at the Café Rossini at five. It had been Carol who suggested the meeting, explaining on the phone that she’d just started radiotherapy, having had two weeks’ respite after her last course of chemo. Carol arrived first, wearing one of the usual ethnic outfits that did little to hide her angular figure and terrible posture: a cotton shift and trousers in a vaguely Moroccan style, a pair of sneakers, and lots of African seed necklaces and bracelets. Danny D’Angelo, a waiter who had served Carol on several occasions, greeted her with an effusiveness many of his customers had come to fear. Danny boasted that he was friends with half the population of North Beach—especially the regulars at the Café Rossini, where he’d been a waiter for so long that no one could remember a time before he worked there.

“Hey, girl, I gotta say that turban you got on is a lot better than that fright wig you been wearing lately,” were his first words to Carol Underwater. “Last time you were here, I thought to myself, ‘Danny, you gotta tell that girl to ditch the dead skunk,’ but in the end, I didn’t have the heart.”

“I have cancer,” said Carol, offended.

“ ’Course you do, princess, even a blind man can see that. But you could totally rock the shaved-head look—lots of women do it these days. So what can I get you?”

“A chamomile tea and a biscotti, but I’ll wait till Indiana gets here.”

“Indi’s like Mother fucking Teresa, don’t you think? I tell you, I owe that woman my life,” said Danny. He would happily have sat down and told Carol Underwater stories of his beloved Indiana Jackson, but the café was crowded and the owner was already signaling to him to hurry up and serve the other tables.

Through the window, Danny saw Indiana crossing Columbus Avenue, heading toward the café. He rushed to make a double cappuccino con panna, the way she liked it, so he could greet her at the door, cup in hand. “Salute your queen, plebs!” Danny announced in a loud voice, as he usually did, and the regulars—accustomed to this ritual—obeyed. Indiana planted a kiss on his cheek and took the cappuccino over to the table where Carol was sitting.

“I feel sick all the time, Indi, and I’ve hardly got the strength to do anything.” Carol sighed. “I don’t know what to do—all I want is to throw myself off a bridge.”

“Any particular bridge?” asked Danny as he passed their table, carrying a tray.

“It’s just a figure of speech, Danny,” snapped Indiana.

“Just saying, hon, because if she’s thinking of jumping off the Golden Gate, I wouldn’t advise it. They’ve got railings up and CCTV cameras to discourage jumpers. You get bipolars and depressives come from all over the world to throw themselves off that freakin’ bridge, it’s like a tourist attraction. And they always jump in toward the bay—never out to sea, because they’re scared of sharks.”

“Danny!” Indiana yelped, passing Carol a paper napkin to blow her nose.

The waiter wandered off with his tray, but a couple of minutes later he was hovering again, listening to Indiana try to comfort her hapless friend. She gave Carol a ceramic locket to wear around her neck and three dark glass vials containing niaouli, lavender, and mint. She explained that, being natural remedies, essential oils are quickly absorbed through the skin, making them ideal for people who can’t take oral medication. She told Carol to put two drops of niaouli into the locket every day to ward off the nausea, put a few drops of lavender on her pillow, and rub the peppermint oil into the soles of her feet to lift her spirits. Did she know that peppermint oil was rubbed into the testicles of elderly bulls in order to—

“Indi!” Carol interrupted her. “I don’t even what to think about what that must be like! Those poor bulls!”

Just at that moment the great wooden door with its beveled glass panels swung open—it was as ancient and tattered as everything in the Café Rossini—and in stepped Lulu Gardner, making her daily rounds of the neighborhood. Everyone except Carol Underwater immediately recognized the tiny, toothless old woman. Lulu was as wrinkled as a shriveled apple; the tip of her nose almost touched her chin, and she wore a scarlet bonnet and cape like Little Red Riding Hood. She’d lived in North Beach since the long-forgotten era of the beatniks and was the self-professed official photographer of the area. The curious old crone claimed she had been photographing the people of North Beach since the early twentieth century when Italian immigrants flooded in after the 1906 earthquake, not to mention snapping pictures of every famous resident from Jack Kerouac (an able typist, according to Lulu), Allen Ginsberg, her favorite poet and activist, and Joe DiMaggio, who’d lived here in the 1950s with Marilyn Monroe, to the Condor Club Girls—the first strippers to unionize, in the 1970s. Lulu had photographed them all, the saints and the sinners, watched over by the patron saint of the city, Saint Francis of Assisi, from his shrine down on Vallejo Street. She wandered around with a walking stick almost as tall as she was, clutching the sort of Polaroid camera no one makes these days and a huge photo album tucked under one arm.

There were all sorts of rumors about Lulu, and she never took the trouble to deny them. People said that though she looked like a bag lady, she had millions salted away somewhere; that she was a survivor from a concentration camp; that she’d lost her husband at Pearl Harbor. All anyone knew for certain was that Lulu was Jewish—not that this stopped her celebrating Christmas. The previous year Lulu had mysteriously disappeared, and after three weeks the neighbors gave her up for dead and decided to hold a memorial service in her honor. They set up a large photo of Lulu in a prominent place in Washington Park where people came to lay flowers, stuffed toys, reproductions of her photos, meaningful poems, and messages. At dusk the following Sunday, when a dozen people with candles had gathered to pay a reverent last farewell, Lulu Gardner showed up in the park and promptly began to photograph the mourners and ask them who had died. Feeling that she had mocked them, many of the neighbors never forgave her for still being alive.