Rewilding

David Woodfall

A hopeful yet practical collection of essays exploring the many opportunities and benefits of rewilding and how to get involved today. Highly illustrated with nature photography tracing landscape change over thousands of years. Rewilding is the thoughtful practise of letting natural ecological processes run their course to change a habitat. Both nature and people are enriched by the process. There are many ways of being engaged in rewilding, and a whole range of people helping to achieve it. Essays in this book are written by professionals in in the fields of wildlife conservation, recreation, education, agriculture, and forestry, as well as by people actively involved in successful rewilding. Each one contributes to our understanding of what 'rewilding' really means, and provides a practical guide for more communities to strive for more connected, satisfying and sustainable lives.

COPYRIGHT (#u8e808d58-f6dd-55bd-a879-21d8994fc2a9)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright in this compilation © David Woodfall 2019

Individual essays © Respective authors

All photography © David Woodfall 2019, with the exceptions of here (© Stephen Barlow) and here (© Ben Andrew).

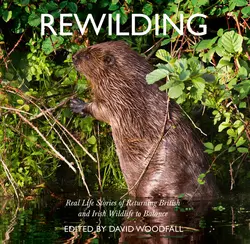

cover image: European Beaver, Bevis Trust, Carmarthenshire, Wales

David Woodfall asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008300470

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008300487

Version: 2019-05-09

Sheep on snowscape, Conwy, Wales.

Definition of Rewilding (#ulink_197fca1e-6760-5710-ad87-b2b37919a10f)

Rewilding is a contested idea, and people have different views on what exactly it should aim to achieve. For me, two elements of rewilding are crucial. The first is that natural ecological processes should be allowed to run their course, whereby new species can colonise an area, or a new habitat develop – which may, then, be replaced by a subsequent habitat. The second aspect is just as important, and this is that rewilding is something enacted by people, even where the intention is to leave nature to it. These people benefit from rewilding: this benefit might be spiritual, health-related or, indeed, economic. The overall goal is to kindle a more thoughtful approach to living on the Earth, and to support a move to more sustainable living.

This way of thinking has been around a long time. For example, in a book called Sharing the Work, Sparing the Planet by Anders Hayden, published in 1999, the author sets out a vision to enable us to achieve both greater sustainability and an enhanced quality of life. He argues that a lifestyle that is less rushed, more thoughtful and community-orientated could both enrich peoples’ lives at the same time as stopping us from degrading the life support which our planet now struggles to provide. This reflects my two themes: enriching nature and enriching people’s lives in the process.

The aim of this book is to show the many ways of being engaged in rewilding, and the great range of people who are helping to achieve it. I have visited a wide variety of places and spoken to many people, alone and in groups and within organisations, in the UK and Ireland. When I started out I had little idea how many people were actively rewilding. I recorded my impressions through photography – photographs that trace the changing landscape across thousands of years, and the human timeline from stone beehive huts to contemporary homelessness. The significance of rewilding is illuminated in essays written by professionals in the fields of wildlife conservation, recreation, education, agriculture and forestry, and by the people actively involved in making rewilding successful. I hope the book will contribute to our understanding of the potential opportunities and benefits that rewilding offers, and to provide a practical guide for new communities to strive for better connected, satisfying and sustainable lives.

FOR TESNI AND HELEN WITH LOVE

Contents

Cover (#u145f3177-cb09-549b-b802-63b608b9cf12)

Title Page (#u5af8987e-8cc8-59d8-9e8b-a29645600789)

Copyright

Definition of Rewilding (#ulink_b09afc06-6e7b-5a58-b87f-01f7188abd5c)

Dedication (#u096678dd-ef6c-51ee-82d7-3a38adcb7ff0)

Introduction David Woodfall (#ulink_30613324-2f74-5db8-836e-fc2fc8ee21bf)

Rewilding in Alladale Paul Lister (#ulink_de8ff2e3-1a67-59b0-b37b-375c38604a9c)

Rewilding in the Cairngorms National Park Will Boyd-Wallis (#ulink_6b06def5-c50b-55fe-b00e-4cabf6bf28eb)

Restoring the Caledonian Forest Doug Gilbert (#ulink_f601fb6e-0a82-5daa-8d95-9a5b8785482b)

Carrifran Wildwood Philip Ashmole (#ulink_8da37bcf-7934-53dc-8eb2-10285fc610c1)

Rewilding and Nature Agencies Robbie Bridson (#ulink_90a6ed4a-4973-5d6a-9803-c0b7af8565e9)

Wild Nephin National Park Susan Callaghan (#ulink_667bc63b-cb0b-544d-bc7f-39e962865eea)

A Wetland Wilderness Catherine Farrell. (#ulink_88f3fed9-dcf3-5ee4-b837-7dd209920d93)

Rewilding the Marches Mosses Joan Daniels (#ulink_af8b1958-3950-5c7a-b13a-a103db25ce60)

Kielder’s Wilder Side Mike Pratt (#ulink_8d216100-b68c-5b46-9b14-470ed6c035e3)

Minimum-Intervention Woodland Reserves Keith Kirby. (#ulink_56f19033-1c87-5433-ae05-45e2924534fa)

Wild Ennerdale: Shaping the‘Future Natural’ Rachel Oakley (#ulink_06f7779a-9787-5ce1-9389-760be8e86c45)

Epping Forest: A Wildwood? Judith Adams (#ulink_e92394e8-6783-59a1-b9e1-84950e4025c9)

The Burren: History of the Landscape Richard Moles (#litres_trial_promo)

Red Squirrel Craig Shuttleworth (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Oxwich NNR Nick Edwards (#litres_trial_promo)

Cabragh Wetlands Tom Gallagher (#litres_trial_promo)

Lough Carra Chris Huxley (#litres_trial_promo)

Time is Running Out Drew Love-Jones & Nicholas Fox. (#litres_trial_promo)

The North Atlantic Salmon Allan Cuthbert (#litres_trial_promo)

Riverine Integrity William Rawling (#litres_trial_promo)

Moorland Geoff Morries (#litres_trial_promo)

Reflections on the Summit to Sea Project Rebecca Wrigley (#litres_trial_promo)

The South Downs Phil Belden (#litres_trial_promo)

Landscape-scale Conservation of Butterflies and Moths Russel Hobson (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding in the Context of the Conservation of Saproxylic Invertebrates Keith Alexander (#litres_trial_promo)

Great Bustards David Waters (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Bumblebees Dave Goulson (#litres_trial_promo)

New House Hay Meadows Martin Davies (#litres_trial_promo)

Pigs Breed Purple Emperors Isabella Tree (#litres_trial_promo)

Pant Glas Nick Fenwick (#litres_trial_promo)

The Pontbren Project Wyn Williams (#litres_trial_promo)

Lynbreck Croft Sandra & Lynn Cassells (#litres_trial_promo)

South View Farm Sam & Sue Sykes (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding in My Corner of Epping Forest Robin Harman (#litres_trial_promo)

Prayer for Red Kites at Gleadless Martin Simpson (#litres_trial_promo)

Species Introductions Matthew Ellis (#litres_trial_promo)

Steart Marshes Tim McGrath (#litres_trial_promo)

Whiteford Primary Slack Nick Edwards (#litres_trial_promo)

Seashore Richard Harrington (#litres_trial_promo)

Little Terns David Woodfall (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding at the Coast Phil Dyke (#litres_trial_promo)

Machair Derek Robertson (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Whales Simon Berrow (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Notes on Forest Gardens Mike Pope (#litres_trial_promo)

The ‘Wilding’ of Gardens Marc Carlton & Nigel Lees (#litres_trial_promo)

Vetch Community Garden Susan Bayliss (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding: My Hedgehog Story Tracy Pierce (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Cities Scott Ferguson (#litres_trial_promo)

Colliery Spoil Biodiversity Liam Olds (#litres_trial_promo)

The Place of Rewilding in the Wider Context of Sustainability Richard Moles (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding the Law Mumta Ito (#litres_trial_promo)

Homeless Siobhan Davies (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding Reborn Em Mackie (#litres_trial_promo)

Rewilding of the Heart Bruce Parry (#litres_trial_promo)

Conclusion David Woodfall (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Colonising silver birch in glaciated valley, Alladale.

Introduction (#ulink_51becb2e-10a6-5763-9643-a282b6bf160b)

David Woodfall (#ulink_51becb2e-10a6-5763-9643-a282b6bf160b)

Following the end of the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago, Britain and Ireland began to colonise with birch and oak which, apart from mountain tops, became established in all of our islands. Rewilding, essentially a new concept, is the return to allowing nature to take its own course and carpet our islands once more in natural vegetation and its associated fauna. During the Mesolithic period (15,000–5,000 bce) this native forest was considerably modified by burning and felling. By the Middle Ages (500 ce onwards) the wildwood had been replaced by a mosaic of cultural landscapes, created by an ever-increasing population. The Enclosure Acts of the eighteenth century were swiftly followed by the Industrial Revolution, with its increasing demands on mineral and timber resources, and further modified our landscapes. Landscapes became empty of all of our major predators, such as wolves, and landscape modifiers such as the beaver. While our cultural landscapes contained wonderful chalk grassland grazed by huge flocks of sheep, numerous heathlands grazed by cattle and diminishing peat bogs harvested by crofters in the north and west, these landscapes were unrecognisable from their native state, much of their diversity and richness gradually stripped away. During the Industrial Revolution there was a rapid reduction in the number of people employed on the land and a consequent decline of rural communities. There were changes, too, affecting limestone pavements, peatbogs – a reduction of sheep farming led to the depletion of chalk grassland. The last time our islands possessed any degree of biological richness was the 1930s, a richness that disappeared swiftly during the 1940s when World War II interrupted food imports, leading to a massive increase in lands given over to arable crops.

By the 1960s only a handful of intensively managed nature reserves contained a fraction of our previous flora and fauna, often isolated islands in an extensive agricultural prairie, where food production was continually supported by pesticides and chemical fertilisers, further diminishing our wildlife – the future of peregrine falcons were threatened by the build-up of toxins in the food chain. In the US, scientists such as Rachel Carson began to draw the public’s attention to such concerns and the environmental movement was born. This has subsequently led to the evolution of the rewilding movement, which I would define as allowing the natural succession from open ground to forest to take place, much in the way it happened 10,000 years ago. Essentially, to allow the landscape to develop in an organic way, opening up the full range of available niches for local species. However, much of the landscape of the UK and Ireland has been so severely modified that in many cases it is a challenge to allow rewilding to take place, as this process can lead to a short-term reduction in the existing diversity. In effect, the decision on the part of conservation organisations to cease management is a form of management in itself. Many of the priorities in conservation previously seen as set in stone will have to be carefully reconsidered. Further complications emerge from the significant changes being wrought on our landscapes, ecology and ourselves by climate change.

Dinosaur footprint, Severn Estuary.

By the modern age, most of the significant apex, ‘game changers’ within our flora and fauna, were now absent – in parallel with a naturally developing climax vegetation, it was deemed necessary to reintroduce many of the key animals which significantly affect the ecology of our landscapes. These include beavers, lynx, sea eagles, and red kites: species that will help stimulate and revive ecological processes that have been absent from our lands for thousands of years. The introduction of beavers could have a significant effect on reducing the flooding of agriculture areas and towns, something that appears to have increased in both intensity and frequency. Species such as sea eagle and red kite have already demonstrated that their increased presence can have a significant beneficial effect on tourism at both a local and national level.

This work has been carried out by inspired individuals, scientists and a growing number of NGO organisations, who are working with the government conservation agencies to help negotiate with landowners, carry out research and conduct trials with reintroduced species to ensure that such populations are sustainable and equitable among our highly managed islands. In addition, rewilding calls for a greatly reduced grazing regime in our uplands by both deer and sheep, and a general reduction in the grazing of our grassland ecosystems where appropriate to increase both plant and invertebrate populations, which in turn will greatly increase our mammal and bird populations. Due notice will have to be given to our ‘cultural habitats’, e.g. downland, which have evolved through our grazing regimes. Also both the significance and value of our post-industrial sites will have to be given greater recognition as we are blessed with large numbers of places that are great examples of the beneficial effect of rewilding, without us doing anything active at all. The reduction in fishing through a system of quotas, during the last ten years, has once again made the North Sea a place in which to fish sustainably, and the introduction of many wind turbines has had the effect of creating ‘artificial reefs’ which have further increased marine diversity. This is nowhere better demonstrated than the huge growth in cetacean and grey seal populations throughout Britain and Ireland. In turn this has attracted significant populations of killer whale. The changing sea temperatures around our coasts, due to changes in the jet stream, are also enhancing our whale and dolphin populations. Tuna weighing up to 230 kg (500 lb) have been caught off the Hebridean island of St Kilda, demonstrating that our seas, too, can be rewilded.

Our agricultural landscapes, even more so than the native habitats, have the potential for great change through rewilding. Our agriculture has been heavily subsidised through the European Economic Union (via Common Agricultural Payments), since the 1970s, and this has had a profound effect on both the landscapes themselves and their biodiversity. We are about to leave Europe and at the very least this is going to produce uncertainty for our agricultural landscapes. The most likely outcome of this will be that large areas of land will not be cultivated as intensively as previously. On the other hand, financial conglomerates, pension funds and extremely rich individuals may well buy up aggregations of small farms and produce ‘super farms’, leading to even greater insensitive management of our landscapes. The first of these outcomes ought to give the opportunity for a theory like rewilding to really flourish, allowing for many natural processes to take hold once more, rather than the more manicured effects of conservation that have been attempted so far. We have reached a point in our islands’ evolution where our growing understanding of rewilding has the realistic prospect of gaining both political and popular support. This has been achieved, in part, by the rapid growth of environmental education, and the popularity of TV and radio programmes by such people as David Attenborough – informing and enthralling the public with the ‘natural world’. This in turn has inspired countless individuals, paid and voluntary, to get involved in disparate conservation projects employing both species introduction and the development of more naturally developing climax vegetation communities. Rewilding has arrived and I feel that now is the right time to publish a book highlighting all the wonderful organisations and inspired individuals who are making the UK and Ireland such a biologically rich series of islands once again.

Mawddach Estuary, Snowdonia NP, Gwynedd.

Red deer stag at Alladale.

Rewilding in Alladale (#ulink_38f2e60e-3f86-57f2-a24d-16b92d59fea0)

Paul Lister (#ulink_38f2e60e-3f86-57f2-a24d-16b92d59fea0)

I spent my childhood growing up in north London and at a West Country boarding school, with simply no family connection to Scotland. My first trip north of the boarder was at the age of 23 in 1982 when my father, Noel, decided to take Mum and me on a trip to Argyll and Perthshire to look at some commercial forestry opportunities, on a cold, bleak and wet day. We were shown around by Fenning Welstead of the land agents John Clegg, and Des Dougan, a local deer stalker working for the Forestry Commission. After the decision was taken to invest, Des and I struck a chord and he invited me hind stalking.

For the following ten or so years, I met up with Des once or twice a year in a number of locations to help (or hinder) in the culling of red deer hinds and the odd invasive sika. When I first pulled the trigger all those years ago, I wondered what the sport was all about – why was it necessary to shoot so many deer? In my usually inquisitive way, I asked many questions and began to better understand the sorry state of the UK’s environment and especially the negative effects on wildlife. Most noticeably, the missing carnivores whose task, until driven to extinction, was to keep browsing deer numbers in check, which allowed native forests to regenerate and create a natural balance. Sadly, for a multitude of reasons, the vast majority the UK’s native woodland has been felled or burned over the last millennia; with trees gone, sheep and deer took over. Landowners/managers had little tolerance for large carnivores and their threat to livestock and they all soon vanished.

In the mid-1990s Roy Dennis introduced me to Christoph Promberger, a German ecologist who as working for the, now defunct, Munich Wildlife Society in ‘post-communist’ Romania. Two weeks later I set off to meet Christoph and his two socialised wolves, rescued from a fur farm about to close. In the middle of the wild and pristine snowy Carpathian mountains, I learned about a unique and unspoilt corner of Europe; a place lost in time and that had never suffered from mass industrialisation, like so many other countries in Europe. The incredible biodiverse nature of Romania blew my mind and made me realise just how much we had lost in Western Europe, and even more so in the Scottish Highlands. It’s really not difficult to imagine why the UK’s future King has chosen to spend his annual spring holidays in rural Romania, where he owns a home in a remote village, three hours from the nearest airport.

In my mid-forties, and with over twenty years in the furniture business, my mentor and father suffered a severe stroke, which shook our family and left me reflecting on what my life was all about. After some months of reflection and soul searching, I decided that, rather than be a part of the growing environmental problem, I wanted to be part of the solution. After decades of thinking about Britain’s bleak and desert-like environment, I decided to look for a Highland estate to rewild, whilst also establishing The European Nature Trust (TENT), a charity which now supports conservation and wildlife initiatives in Romania, Italy, Spain and Scotland.

After a couple of years and a stringent ‘must-have’ list, Alladale, a sleepy, stunning and remote deer-stalking estate, was purchased with the sole intention of rewilding. Some 15 years on, as the custodians of Alladale Wilderness Reserve (AWR) we have planted almost a million native trees, mainly in the riparian areas, to help mitigate flooding, prevent river bank erosion, provide food and shade for the salmon and trout, while also acting as a significant carbon sequester! Around 50 years ago the Scottish government naively believed landowners should be incentivised to drain peatlands, which would increase the amount of land available for livestock grazing. The resulting consequence was a huge release of carbon into the atmosphere. To counter this, and in partnership with the finance firm ICAP, we pioneered the restoration of our peatlands by blocking 20 km of hill drains. Our restorative actions have now led to newly moistened peat with live sphagnum moss, which once more acts as a massive carbon sequester.

While much of the discussion centred around Alladale has been about large carnivores, we have been busy with other less controversial species. In 2013, with support of TENT and in partnership with Highland Foundation for Wildlife, we released 36 red squirrels on Alladale and three neighbouring estates. The project has been a huge success, with hundreds of squirrels now spread far and wide, bringing smiles to neighbours and visitors alike. In addition we have a small collection of breeding wildcats which will be used to stock a larger-scale breed and release centre, now being planned by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS). We also keep a small herd of Highland cattle whose grazing, trampling and excrement play a significant role in improving the biodiversity of the ground while enriching our newly planted native forests. Over the last 15 years we have reduced deer numbers to around 6–7/km

, which is still above European norms where large carnivores exist. This action has already led to a significant increase in natural tree regeneration! In 2018 we stopped guest stalking with the aim of further reducing total deer numbers down to between 300 and 400 (3–4/km

).

Wild cat, Alladale.

AWR’s Highland Outdoor Wilderness Learning (HOWL) programme has been operational since 2008. Each year we host over 150 teenagers, from multiple regional schools and colleges, who come up for five days at a time to wild-camp and undertake a variety of nature-based activities. This transformational experience has led to two past attendees becoming AWR rangers!

Finally, guest numbers staying at one of Alladale’s four lodges has increased exponentially, which is a clear indicator that, with an environmental focus, it’s possible to attract more visitors and create greater job opportunities than would be the case operating an upland stalking estate. All in all a better plan, while also greatly enhancing the reserve’s biodiversity. That’s what I call a legacy.

Loch Morlich, Badenoch and Strathspey.

Rewilding in the Cairngorms National Park (#ulink_bd527850-82aa-5ddc-8dcf-1ec482355933)

Will Boyd-Wallis (#ulink_bd527850-82aa-5ddc-8dcf-1ec482355933)

Rewilding is as simple as planting wildflower seeds in a window-box, as complex as landscape-scale restoration of habitats – it’s also everything in between. All forms of rewilding lead to more people connecting with nature and this is happening by the bucket-load in the Cairngorms National Park.

The largest National Park in the UK contains a quarter of Scotland’s native woodland and an incredible 1,200 species of regional, national and international importance. The central mountain core, towering over northeast Scotland, is a broad plateau with thin soils and vegetation more akin to the Arctic. Yet even in the wildest, most remote and most extreme uplands, the vegetation hints at a long and complex history of landscape and land-use change.

In the core of the Park there is evidence of hunter-gatherer camps estimated to be nearly 10,000 years old. Ruined shielings (stone and turf shelters) remind us that our vast open landscapes have been altered for many centuries. Gaelic place names litter the maps, hinting at a more wooded landscape where our ancestors had an intimate knowledge and close connection with every wood, crag, hill and cave. The landscape is more cultural than natural, but now more than ever before, we have the potential to give back more to the land than we take.

If you have a head for heights, you may be lucky enough to find very rare plants like the woolly willow or the alpine sow thistle hidden on a ledge. The ledges keep them safe from fire and herbivores, but they cannot cling on for ever. The chances of pollen passing from one isolated plant to another and the delicate seeds finding a safe place to germinate are slim, but that is set to change. Thankfully rare plants, like the montane willows, are subject to a lot more attention now that there are prominent goals to restore woodland, wetland and peatland habitats – but we still have a long way to go.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) is pushing hard to inspire and encourage nature conservation throughout the National Park. The top three conservation goals set out in our National Park Partnership Plan are all to do with landscape-scale collaboration, deer management and moorland management. We aim to see real meaningful change over the next few decades that will lead to bigger, healthier and better connected habitats. With forest cover at only 15% of the Park area, there is vast scope to expand and connect our native woodlands. Guided by our new Forest Strategy, the health and species diversity of our existing forests will be enhanced and native woodlands expanded by willing landowners.

Many estates already incorporate conservation management of woodlands, wetlands and peatlands alongside their other management objectives, for the greater good of nature and for us all. Four ‘Cairngorms Connect’ landowners already manage 9,800 ha of forest and 10,000 ha of wetlands with an ambitious 200-year vision to expand them further through deer management and peatland restoration. Six ‘East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership’ landowners aim to integrate habitat enhancement and species recovery alongside moorland management. Three other partnerships work with landowners in the Spey, Dee and South Esk catchments to restore wetlands, plant riparian woodland, re-meander rivers and encourage natural flood management.

The Cairngorms Nature Action Plan has helped to focus attention on the habitats and species most in need of help. Over 1,000 ha of peatland restoration and well over 3,000 ha of native woodland creation has been achieved by landowners supporting these goals over the last five years alone. There has been a strong emphasis in involving people in conservation through volunteering and events to celebrate Cairngorms Nature. Major complex projects to care for the capercaillie and the Scottish wildcat have received millions of pounds of investment from the Heritage Lottery Fund. These charismatic species deserve all the help they can get, but we haven’t forgotten the ‘little guys’: the Rare Invertebrates and Rare Plants projects are doing great work to involve more and more people in helping these crucial threads in the web of life.

Ptarmigan.

We are at a time of great change. Opinions on the future of our uplands are often polarised and yet, if our recent ‘Europarc’ conference is anything to go by, there is an overwhelming force of commitment across Europe to rewild, repeople and reconnect us all with nature in our National Parks.

Golden eagle on a decimated mountain hare.

Restoring the Caledonian Forest (#ulink_13c5bfd6-498e-5210-8a5e-3ccfef94bbe4)

Doug Gilbert (#ulink_13c5bfd6-498e-5210-8a5e-3ccfef94bbe4)

I’m setting off today to monitor the progress of natural regeneration in the woodlands at Dundreggan. As I climb through the birch woods, I notice some of the smaller creatures that abound – wood ants scurrying busily about, a woolly caterpillar crossing the track in front of me, the green flash of a tiger beetle as it drones away from my step. As I pass a grove of old Scots pine trees, I notice a few seedlings poking out of the heather at the side of the pathway. A feeling of excitement – it’s happening! – enters my thoughts. In the quiet thrum of a summer morning, I start to tune in to the natural world around me. A young buzzard mews; a woodpecker chacks in annoyance at me and I stoop down to examine a pine cone dropped by a red squirrel some time ago. They’re on their way back too, I muse. Reaching the upper edge of the wood, I emerge from the dappled green shadow of the birches and squint in the full sun on the moorland. The wood ends abruptly – tall mature birch trees give way suddenly to a treeless moorland, which now stretches ahead as far as I can see above me. I find my monitoring point among some tall heather on the slope of a small, steep hill and start counting and measuring all the young seedling trees I can find – lots of tiny downy and silver birch, a few young juniper bushes and several rowan. A few of these are beginning to emerge above the general level of the heather vegetation – poking their heads above the parapet – and I see that one of the rowans has not been browsed for at least two years. All good signs. As I get my eye in, I can see a few birches in the vicinity also poking above the heather and bog myrtle. If we continue like this for the next few years, it will really begin to look like a young forest!

Dundreggan is a small island of hope for the future of the Caledonian Forest, a wild woodland that once stretched across much of Highland Scotland but which is now reduced to a shadow of itself. Only 4% of Scotland’s land area is currently covered by native woodland, and over half of that is in poor condition, mainly because of high browsing pressure from herbivores – mainly sheep and deer.

I joined Trees for Life in 2014, inspired by the vision for a big native forest in the north-central Highlands of Scotland. There is something fundamentally exciting about the prospect of a big forest, inhabited by all the things that should be there, and one where natural processes are in charge. We live in a highly managed landscape: urban cityscapes, straight-edged agricultural monocultures, commercial forests of regimented conifers and checker-board treeless moorlands. Where are those places where we can experience the full power of natural growth – the sheer exuberance of plant and animal diversity that develops in more natural systems?

At Dundeggan, a 4,000+ ha estate in Glen Moriston, just west of Loch Ness, Trees for Life are building habitats for the future. Our treeless uplands are accepted by most people as ‘they way things are’, almost unable to imagine a landscape of wooded hills and mountains. Treeless uplands have landed Scotland with a triple whammy of reduced biodiversity and resilience to climate change; increased risk of flooding, as water cascades rapidly off the hillsides into spate rivers; and degradation of peatlands, leading to pollution of drinking water sources and more greenhouse gas emissions. Trees for Life’s vision of naturally wooded hills and mountains is an antidote, not only to these ecological problems, but also to the feeling of hopelessness that often pervades people’s thinking about environmental issues. At Dundreggan volunteers take part in practical action which addresses these issues at a fundamental level – we plant trees and encourage natural regeneration of native woodlands, building the beginnings of a new, hopeful future for the uplands of Scotland.

At the heart of these issues is the red deer population, particularly the stags so beloved of Visit Scotland as the poster boy of the Highlands. The original painting, The Monarch of the Glen, by Sir Edwin Landseer recently toured the public spaces of Scotland and the picture of a huge, wild, noble animal still resonates with people as an icon of wild Scotland. However, the development of a commercial industry around sport shooting of red deer stags has meant more and more management of the deer population of the highlands – selective culling, translocations of stags across the country in an attempt to ‘improve stock’, habitat manipulations and more recently winter feeding with silage and turnips have reduced the wild red deer herds of the past to semi-ranched livestock. For decades now, public bodies such as the Red Deer Commission and its successors, Scottish Natural Heritage and now the Scottish government have been encouraging, cajoling and more recently threatening the deer sector in Scotland to take action to reduce the over-population of the uplands with red deer (along with other deer species), but the industry seems entrenched in the view that a high red deer population is required to produce a sporting stag ‘surplus’. As this impasse grinds on, Scotland’s upland habitats become more and more degraded.

The rewilding of red deer is arguably now the most urgent conservation challenge in Scotland. By reducing the deer population and expanding their natural woodland habitat, we can begin to address all these problems. Biodiversity, flooding, pollution, greenhouse gas emission and, importantly, the welfare of the deer themselves can all improve under a reduced deer population. Even the sport stalking experience can be enhanced. The need to fence establishing woodland would reduce – or even disappear – if natural process were truly allowed to establish. Imagine a Scotland where unstoppable native woodland expansion was happening across large areas of the Highlands – new habitat areas for our native woodland flora and fauna; a more natural patchwork of wooded and unwooded habitats fundamentally based on natural processes; where hunting wild red deer was truly a challenging activity in a wonderful varied natural landscape of woods, bogs, mountain tops and meadows.

These are all big issues and big visions, but we have to start in the here and now. As the old adage goes – ‘the best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago; the next best time is now’. Trees for Life’s Dundreggan rewilding project beckons us towards a new future for the uplands of Scotland – not a return to some past idyll, but forward to a more sustainable, more diverse and more entrancing natural landscape.

Carrifran on a cold February day.

Carrifran Wildwood (#ulink_936861cb-02e8-58c0-8023-94e8f1e44eb3)

Philip Ashmole (#ulink_936861cb-02e8-58c0-8023-94e8f1e44eb3)

The vision of a restored wildwood in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, conceived by Philip and Myrtle Ashmole in 1993, was based on the conviction that a grassroots community group could purchase an entire valley and – by a science-led process of ecological restoration – recreate an area of upland wilderness. This had to be large enough to establish plant and animal communities comparable to those flourishing there 6,000 years ago – long after the loss of the ice sheets, but while the sparse human inhabitants had relatively small impact on their environment. That date was easy to choose, since it was the age of the oldest longbow known from Britain, found in peat high on Carrifran in 1990.

Central to the wildwood concept was the idea that after planting and protecting missing species of trees and shrubs, we could gradually hand over management to nature, so that the wildwood would develop as a naturally functioning ecosystem, with a wide variety of beautiful habitats and a rich diversity of species.

Establishment of the Millennium Forest for Scotland Trust (MFST), an inspired offshoot of the National Lottery, triggered formation of the Wildwood Group in 1995. Members came from a wide range of backgrounds and occupations, united by a clear vision and a willingness to work for free. With other activists, we helped to form and become part of Borders Forest Trust (BFT) in 1996. However, a suitable site for the wildwood was hard to find, and lottery deadlines had passed by the time we had made a deal for the purchase of Carrifran, so the group decided to raise the funds themselves. A link with the John Muir Trust gave weight to our appeals, and there was an extraordinary response from members of the public, so that BFT was able to purchase Carrifran on Millennium Day.

Carrifran is a spectacular ice-carved glen extending some 650 ha, and rising from 160 m by the road to 821m at the summit of White Coomb, the fourth-highest peak in southern Scotland. In 2000 the entire site had been grazed and browsed for centuries by sheep and feral goats. However, because some rare mountain flowers remained, it formed part of the Moffat Hills SSSI and is now also a Special Area of Conservation.

For a grassroots group with an ambitious vision, gaining the confidence of relevant authorities is crucial. Planning the transformation of Carrifran began with a major conference in Edinburgh under the title ‘Native Woodland Restoration in Southern Scotland: Principles and Practice’. This was followed in 1998 by monthly meetings in a local pub of a diverse and lively planning group convened by our local volunteer Adrian Newton, a forest ecologist at Edinburgh University. The group developed a restoration plan for Carrifran which gained the necessary approval of Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) and the Forestry Commission late in 1999. Within BFT, we agreed that management decisions for Carrifran should be made by a Wildwood Steering Group and a small Site Operations Team, maintaining the grassroots character of the project. Ultimate responsibility, however, rests with the BFT Trustees, some of whom are also members of the Steering Group as volunteers.

On Millennium Day more than a hundred supporters were piped onto the site to plant the first trees, raised in back garden nurseries. By the end of that month our Woodland Grant Scheme application had been approved, an extraordinary benefactor had agreed to pay for half a million trees (all of them to be propagated from seed collected locally by volunteers) and Hugh Chalmers had been appointed as Project Officer with funding from SNH. In the summer an 11-km perimeter stock fence and some temporary internal fences were erected with windfall funding from MFST, and that autumn most of the goats were rounded up and taken to sites in England found for them by Hugh.

Over the next seven years 300 ha of broadleaved woodland were established in the lower parts of the valley, using contracts with individual planters and small groups. The rules of the grant scheme left us deficient in shrubs such as hazel, hawthorn, blackthorn, juniper, roses and all the scrubby willow species that would be expected in and around ancient woodland, so tens of thousands more shrubs had to be added later. This planting has been the main role of a dedicated band of ‘Tuesday volunteers’ who have come to work at Carrifran each week, some of them for more than ten years. In addition, hill-walker volunteers have inspected and made running repairs to the perimeter fence almost every month since 2001.

The great altitudinal range of Carrifran offered an unusual opportunity to establish treeline woodland and ‘montane scrub’, low-growing, wind-pruned shrubs growing in such exposed conditions that upright trees could not survive. This habitat is almost lost from Britain but widespread in Scandinavia and elsewhere. In the last decade about 30,000 willows and junipers have been planted high up at Carrifran, mainly during a series of 15 High Planting Camps in spring.

In the main valley some of the trees are now 4 to 5m high and in some places the canopy is closed, favouring shade-tolerant flowering plants, such as ferns and bryophytes, and causing the retreat of bracken. Bluebells are rapidly colonising the woodland from a few places where they have survived for centuries, and some of the special mountain flowers have escaped from their prisons on the crags and spread down the burns, providing a wonderful floral display in summer.

Other changes following removal of grazers and planting of trees have been revealed by formal studies at Carrifran and the adjacent valley of Black Hope, still grazed and functioning as a ‘control’ site. Vegetation surveys carried out in 2000/01 and 2013 showed extensive replacement of anthropogenic grassland by heathland and recovery of tall herb communities (especially along watercourses). Annual surveys of breeding birds show woodland species flooding in to reclaim habitats lost many centuries ago. Data of this kind are rare, and their publication generated a marked increase in visits by student groups and professional environmental managers. Furthermore, feedback from members of the public shows that Carrifran has now become truly inspirational, as we had always hoped.

In the meantime, Borders Forest Trust has been developing a more extensive vision, ‘Reviving the Wild Heart of Southern Scotland’. In 2009 the Trust purchased the 640-ha farm of Corehead and Devil’s Beeftub, which now features both low-intensity sheep farming and 200 ha of developing native woodland. Four years later BFT purchased Talla and Gameshope, meeting the northern boundary of Carrifran and extending to 1,830 ha, more than half of which is above 600 m. Grant-aided planting on this site already covers 40 ha, and volunteers have planted thousands of trees, as well as starting to establish montane scrub on the 750 m summit of Talla Craigs.

Of the 3,000 ha of hill land owned by BFT, a large proportion falls within one of only two ‘wild land areas’ identified in southern Scotland in a recent SNH project. BFT hopes that in the years to come, restoration work by the Trust and nearby landowners will ensure that the whole of the area becomes a truly wild and naturally functioning ecosystem.

Ulpha Common, Lake District National Park.

Rewilding and Nature Agencies (#ulink_1f88f8fc-26c2-5fd0-bbc2-8448d7e8889f)

Robbie Bridson (#ulink_1f88f8fc-26c2-5fd0-bbc2-8448d7e8889f)

Between 1969 and 2007 I was privileged to work on nature conservation and land management as a Nature Conservancy Council warden, afterwards chief warden, and ultimately regional manager. Over this period my responsibilities involved working in Wiltshire, the Highlands and coast of Scotland, and North West England. During those 38 years, there was plenty of opportunity to be involved in species research and management on most major habitats. As chairman of the wardening staff association in Britain I had a unique opportunity to be involved throughout the country. After retirement in Cumbria my appointment to the Lake District National Park Authority gave an insight into planning, recreation and tourism.

Having been ‘out of the loop’ for some time my memories and assumptions might not be accurate, but I am aware that changes have affected the management of nature conservation over the past 50 years.

It seems improbable now, but I recall that in 1974 there were only two of us (a warden and a scientific officer) working on the ground in Scotland south of the Clyde and Forth. The RSPB had wardens on sites in Britain but many fewer in number than now. The Wildlife Trusts were not widely known and had few site managers.

The National Trust was involved in its country house management, landscape, and recreation, with just a small number of staff dedicated to nature conservation. The Forestry Commission was focused on timber production.

All that has changed. I am always pleased to see Wildlife Trust staff featuring regularly on Countryfile and the RSPB has become the most well-known and influential organisation for nature conservation in the UK with many links to the rest of the world. The National Trust employs dedicated ecologists and staff who are knowledgeable and effective in safeguarding the natural environment on their properties. The same commitment to nature conservation with well-informed staff has occurred in the Forestry Commission along with their emphasis on recreation. Throughout Britain local authorities now have officers working in all aspects of managing the environment and involving people.

When I became a warden there was no training to equip anyone becoming involved in nature conservation. Working as a volunteer was a way to become part of the system but there were no academic or technical opportunities. Today there are myriad colleges and agricultural establishments offering degrees in a range of land and wildlife management. Perhaps there are already courses in rewilding?

Governments have also made some major changes that improve the safeguarding of biodiversity, with the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, the European Habitat and Species Directives, and the creation of the Environment Agencies perhaps being the most significant.

It might seem that wildlife is now safeguarded in Britain, but it all remains vulnerable. The long-term consequences of climate change, agricultural intensification, pollution, and development will always be major threats.

Looking back over the years, I feel there are some aspects of the changes to the Scottish, Welsh and English wildlife agencies that have diminished their ability to protect the environment. They are directly linked but there are three elements that I feel are significant.

The break-up of the Nature Conservancy Council The government set up the former Nature Conservancy (later Nature Conservancy Council) with very focussed policies based on science and research. The agency was filled with dedicated, and inspirational, ecologists and developed into a national network. I remember that if there was a question, for example about entomology, ornithology, or geology, an expert was at the end of a phone and could arrange a visit. That national network and the focus on science and research has gone.

The clumping together of the environmental responsibilities This would seem a positive move, as all the impacts on our environment are linked and should be coordinated, but it relies on sufficient qualified staff and management. My occasional discussions with former colleagues in the three national agencies reveal that their nature conservation responsibilities are being overwhelmed because recreation, development and agriculture have a higher profile.

The diminished power of the national agencies Would the problems faced by the efforts in safeguarding scheduled coastal sites from golf development in Scotland, or fracking in England, have had a different outcome with a national and powerful nature conservation agency? Long-serving staff I knew in the RSPB and the Wildlife Trusts have negative views about the power and effectiveness of the agencies, which saddens and worries me.

Clump of ash trees, Snowdonia National Park.

Yes, there is so much to celebrate in the work of the non-governmental organisations and individuals in safeguarding our dwindling wildlife. The contributors to this book show the range and diversity of rewilding projects making a positive difference to benefit our wildlife.

The work never ends. National and local governments have policies and commitments to safeguard and improve our natural environments. They must, however, be constantly held to account and balance the pressures from so many other powerful interests.

River Owenduff and blanket bog, Western Ballycroy National Park.

Wild Nephin National Park (#ulink_fd168b02-0f7d-5d1d-803c-757c684c1c29)

Susan Callaghan (#ulink_fd168b02-0f7d-5d1d-803c-757c684c1c29)

The Bangor Trail is an ancient cattle drovers trail that meanders along the western slopes of the Nephin Beg mountain range through the heart of Wild Nephin (Ballycroy) National Park – it leads you to a timeless place. Rainbows are often your welcome banner and a gentle reminder that this can be a ‘soft’ place where the mist and drizzle is only a rainbow away.

Stunning views immerse you in its enormity – but it can be a bit unsettling in its remoteness. It is not just a simple ‘walk in the park’. A few kilometres along the trail a lone, gnarled oak tree (crann darach) is a welcoming site in the vast expanse of heath and bog. It gives you comfort, like an oasis in the desert. This oak is a survivor, a gladiator in this wild world.

This long-distance trail (26 km) is the only access into the western side of the Nephin mountains and the Owenduff bog, the largest intact lowland blanket bog in Ireland. It is a wild expansive peatland – one of Ireland’s natural treasures. Looking west, the sunlight catches a mosaic of bog pools – a patchwork of life, glittering with the reflections of an ever-changing sky. It’s like a universe of planets, each one teeming with life, a minute world within the vast space of bog. The ruins of a cottage along the trail inspires reflection on the many lives that have passed here and, remarkably, some who would have lived here. It was a life dictated by the seaons, where summer grazing for stock brought people into the hills to live. This cottage is long abandoned and nature is reclaiming it. Lichens and mosses decorate the stones and a stunted rowan tree takes root in the tops of the tumbled wall – eeking out nutrients from the slow accumulation of soil in its cracks. The sound of silence can be overwhelming, interrupted occasionally by the guttural croak of a raven, or the descending trill of a meadow pipit. A flash of gold among the dancing bog cotton steals your attention and then a plaintive call. It is a golden plover calling to its mate. This beautiful bird is a delight, it is the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Carabus clathratus, rare beetle typical of peat bogs.

The National Park is managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), part of the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht, and encompasses approx 14,000 ha, including a recent consolidation of lands to the east of the Nephin Beg mountain range, which previously had been managed by Coillte Teoranta (Coillte) for commercial forestry. These lands, like many of the peatlands in Ireland, were viewed as ‘marginal’ lands in the 1950s and 1960s and of little economic use – so they were drained, modified and planted to create the monoculture of Sitka spruce and lodgepole pine that now dominates the landscape. These uplands have also been characterised by decades of overgrazing by sheep – a consequence of the broken subsidised system of the European Agricultural Policy in the 1980s and 1990s. This led to serious overgrazing in the hills, with soil erosion, siltation of the rivers and loss of biodiversity.

The Nephin forest plantation is approx 4,000 ha and fringes the entire eastern section of the National Park up to an altitude of 250m on the eastern slopes of the Nephin Beg mountain range. NPWS acquired these lands with the specific intention to rewild and to allow natural processes to become the dominant driver in shaping this highly modified landscape – where biodiversity is enhanced, functioning ecosystems restored and people have the freedom to engage with nature. A place where the visitor can experience solitude and reconnect with nature. We intend for this area to be the ‘honey pot’ for the National Park, where visitors will have an opportunity to explore the rewilded landscape along a network of trails. From here the visitor can venture further into the heart of the National Park along the Bangor Trail, where there are opportunities for primitive and challenging recreation in a wild and remote landscape, free from mobile phone coverage, free of houses and roads, free from the noise of a busy world. A place where time passes slowly.

The National Park lands are divided into primitive, semi-primitive and semi-developed natural zones. These zones will guide us on how to manage recreational access, with the overarching theme of a minimal tool approach. The National Park is also designated as a Dark Sky Park, a designation from the International Dark Sky Association. We have committed to maintaining our pristine, unpolluted skies from light pollution.

The rewilding project is ambitious for such a large, highly modified area – and with no budget secured yet for conservation initiatives, or extra staff, the challenges can seem overwhelming when you look at the project in its entirety. The invasive Rhododendron ponticuum is a notable concern, with significant mature stands in the south of the site – with the prevailing strong westerly winds, the seeds spread with vigour and wild abandon.

The first major step, though, has been to set out the vision for the rewilding project. A ‘Conversion Plan’ was completed in 2018 setting out a strategy for the next 15 years, the vision to move from a commercial forestry plantation to a place where the conditions have been prepared for nature to become the dominant force. Specific measures have been identified for forested and non-forested areas, as well as riparian and aquatic zones. Blocking drains and bog restoration is essential to mitigate against flooding, improve water quality, and enhance linkages and wildlife corridors.

Felling of conifers over the next five years will be significant, with the purpose of creating an open and diverse forest with improved connectivity between bog, mountain, lakes and rivers. Habitat conditions throughout much of the plantation are currently not suitable for native woodland, so the vision is to develop low-density forest which will allow old growth. Broadleaf cover with native tree species will be promoted on suitable soils, as well as introduced tree species of high ecological value (Monterey pine). We will focus planting of native trees along riparian zones and where soils are drier.

We have already started planting small trial plots of trees (aspen, Scots pine, birch and rowan) to monitor success rate in various site conditions. There are significant pressures from grazing animals (deer and sheep), but we have planted aspen on steep ground to avoid browsing animals. The aspen has been propagated from various locations in the west. We hope to have tree-planting events where local community groups, volunteer groups and schools can come and get involved in the rewilding process.

Deer management as well as rhododendron clearance and control will be essential to allow native trees to establish. The concept of long-term management may be at odds with the overall principle of rewilding, where nature is the dominant force. Without natural predators, though, these two invasive species become the overall dominant force and hinder the natural processes – so it is likely that management of deer and rhododendron will need to continue into the future. Many rewilding projects include the introduction of top predators or large mammals – beaver, crane, black grouse, wolf, lynx – to create a trophic cascade that will balance the ecosystem. It is indeed visionary to try and establish the trophic levels that would have existed here during the postglacial period. Is this a feasible option, though, in Wild Nephin National Park? The state, as landowner, cannot rewild this area without the enthusiasm and support of the local communities. We want to maximise benefits for people as well as the environment. Benefits in terms of environmental services, opportunities to grow ecotourism and ‘cottage industry’ initiatives.

Ballycroy National Park.

The National Park should not be a separate place to the local community; it needs to be part of the community. This landscape has been influenced by humans since the Neolithic period. Ancient human remains, discovered by a local hillwalker in a natural boulder chamber in Ben Gorm (part of the Nephin range) in 2016, date back to 3,600 bce. Research suggests that this site was used as a burial chamber for over 1,000 years. The large ring fort, Lios na Gaoithe (Fort of the Wind), in the northeast of the rewilding site, would have been sited at a strategic location (500–1000 ce) with clear views south and north along the river valley. These views were lost as the conifers grew – but with time and sensitive management this important fort can become part of the wild landscape again, reconnecting the past to the present.

The possibilities are endless, our ambitions and vision are evolving all the time – but with initial small steps and with many steps together, we hope that this place, Wild Nephin National Park, will become an integral part of the community, allowing connection to our past, present and a wild future. A place where peace is found and nature is protected.

Large heath butterfly.

A Wetland Wilderness (#ulink_3bf8feaa-13eb-59f2-9e46-a989725052af)

Catherine Farrell (#ulink_3bf8feaa-13eb-59f2-9e46-a989725052af)

Hundreds of birds create shadows across the landscape. It’s winter. Curlew, lapwing, whooper swan and a range of other birdlife have flocked to the Lough Boora Discovery Park, in the heart of Ireland, to make use of the wide range of habitats that spread across over 3,000 ha of this Irish Midlands refuge.

The Boora Bogs have been central to many changes over the course of their history. Up until the early 1900s most of this area of middle Ireland was a rich tapestry of sphagnum-dominated raised bogs, with associated streams, bog woodland, flushes and the odd human settlement in between. A tranquil place, with little or no industry. But those deep and wet bogs were to become the source of the highly-valued peat that fed the Ferbane power station in County Offaly, and the domestic fire places of families across Ireland. To mine the resource, the great bogs were taken on by Bord na Móna (the Irish Turf Board) in the 1930s, working with the local communities who were forging a living in an otherwise bleak time, for the nascent Irish Republic. And so, the wild bog became industrial bog, and habitats and species that had existed there for millennia were pushed to the edges.

At the time, there was no one to shout ‘stop’. That didn’t come until the late 1970s and 1980s, when the view of the Irish bogs gradually shifted from being one of ‘resource and wasteland’ to ‘wildlife wonderlands and super ecosystems’. The work of ENGOs, such as the Irish Peatland Conservation Council, championed the bogs, and now they are seen more as heritage, than places only worthwhile once drained.

Now that the use of industrial peat is rapidly coming to an end, the future of the bare, barren, brown peat fields is in sight. The work by the Bord na Móna pioneers at Lough Boora has shown that with targeted and minimal intervention the cutaway bogs can be utterly transformed into a new tapestry, this time with wetlands, such as poor fen, marsh, open water, reedbed and pioneer birch woodland – all precursor habitats of the former great raised bogs. Each of these habitats is of value, and present opportunities for a wealth of species as well as a feast for the eyes and ears. A walk through Ballycon Bog during May will yield vistas of extensive bog cotton with breeding lapwing calling happily amidst a frame of birch woodland. And so, the bogs that had become electricity and heating, and supporting systems for tomato plants, are now the newborn wetland and woodlands mosaic within this rapidly changing landscape.

Because of the extent of the Bord na Móna lands – in the region of 80,000 ha, or thereabouts – there is room for everything. Local community walkways, targeted management for rare and ‘on the brink’ species like grey partridge, ecotourism, renewables in the shape of wind turbines and solar panels (you must produce electricity somehow!), and the space and solitude for true – what could be called – wilderness.

My own involvement in these landscapes began in the mid-1990s, when as a research student I was tasked with giving 6,500 ha of Bord na Móna industrial cutaway blanket bog, a helping hand ‘back to nature’. This was in the west of Ireland close to what is now referred to as the Wild Atlantic Way. The approach I took was to observe what happened when the cutaway bog was left to nature’s devices. What I found was that heavily modified landscapes do need a helping hand – especially those bare industrial cutaways of the west. Drain blocking, creating berms to hold water and allowing time for recovery proved to be the best approach. We worked together – nature and I – along with great support from the Mayo bogmen who drove the diggers and excavators, to rewet and rehabilitate the land. When the last drain was blocked, we let go of expectations and left the pockets of bog-moss to grow. And it does, slowly, steadily.

Next to the Midlands, in the mid-2000s, to basically do the same again, albeit on a grander scale. I began a journey of walking through those far less dramatic and exposed industrial bog units, learning from where peat fields had been taken out of production, and imagining how things would be when the Bord na Móna machines passed through that last time on their rehabilitation run. Where the deeper peat layers are exposed by industrial peat production, fen communities establish with fringes of birch. Where deep peat remains, these are the places where a bit of extra effort can recreate those sphagnum-dominated habitats and true bog formation can be restored.

Like in Ballydangan Bog in County Roscommon. Here, the Bord na Móna ploughs barely scratched the surface and this allowed the active raised bog to persist while peat harvesting continued in neighbouring bogs. Ballydangan Bog also acted as a space for the extremely rare Irish red grouse to persist, despite its disappearance from the surrounding bogs. The local gun club and wider community have taken charge here, working to control the fiercely unbalanced predator effect and sustain curlew and grouse, thankfully, successfully and promisingly.

The rehabilitation and restoration work on the Bord na Móna lands today is being coordinated by a small group of ecologists working with a wider team of bog engineers, project managers, surveyors and machine drivers. And, let’s not forget the finance people. But those who drained the bogs – the true bogmen – are critical to the successful post-peat phase. Draining a bog for decades creates an understanding of hydrology, and the fundamentals of ecology. Blocking drains, raising outfalls, turning off pumps – it’s all part of enabling the future.

The work to date has been truly transformative, with values for carbon, water, people, renewable energy and nature. With barely 15% of the lands rehabilitated or restored so far, and another 60,000 ha to go, who knows what benefits are to come? The network of sites across the Irish Midlands will link up other state and privately owned lands zoned for nature, and while people will have their place, it will be alongside thousands of species that will find space in an otherwise crowded-out-by-agriculture landscape. Some people talk about the possible return of the great bittern, lost to the wetland drainage of the last century. Others talk about reintroducing the crane. But maybe they’ll find these wetland-woodland mosaics on their own, along with who knows what other species.

Let’s leave that door, and our minds, open.

Four-spotted chaser, Whixall.

Rewilding the Marches Mosses (#ulink_180ac613-e9db-56af-84bb-169088e8c121)

Joan Daniels (#ulink_180ac613-e9db-56af-84bb-169088e8c121)

The key to landscape-scale rewilding of damaged wetlands is the restoration of the hydrological conditions necessary for their long-term self-maintenance. For 27 years, I have been lucky enough to lead Natural England/Natural Resources Wales’s rewilding of the centre of Fenn’s, Whixall, Bettisfield, Wem and Cadney Mosses Special Area of Conservation (the Marches Mosses), which straddles the English/Welsh border near Whitchurch in Shropshire, and Wrexham.

Over the last 10,000 years, a 1,000-ha rainwater-fed lowland raised bog climax community has developed there because of the amazing powers of sphagnum bog-moss. This has created cold-water-logged, nutrient-poor, acidic conditions: pickling a peat dome, 10 m higher than the current flat, drained landscape – swallowing up the wildwood and spreading over the plain of glacial outwash sand, to the limits of its enclosing moraines.

However, for the last 700 years, this huge wilderness has been drained for agriculture, peatcutting, transport systems and more recently forestry and even a scrapyard. By 1990, the centre of the moss had a peat-cutting drain every 10m and mire plants and animals had been eradicated from most of the site. Nationally, less than 4% of lowland raised mires were left in good condition by then: consequently, many raised bog plants and animals are internationally rare and raised bog is one of Europe’s most threatened habitats.

A large increase in the rate of commercial peatcutting in the late 1980s led NGOs to form the Peatlands Campaign Consortium, to save the Mosses and others like it. The campaign was driven by Shropshire Wildlife Trust’s (SWT) local volunteer Jess Clarke. North Wales Wildlife Trust staff, including myself, and SWT staff, aided by brave Nature Conservancy Council staff, particularly Mark July and Paul Day, pushed to get the government to take on the restoration of this devastated site. The realisation that there was not enough raised bog in good condition to meet Britain’s international conservation obligations, combined with the new peat-extraction company finding that the Mosses’ peat quality was inadequate to meet their site-rental costs, resulted in the Nature Conservancy acquiring the centre of the Moss in 1990.

Cowberry.

Since then, Natural England and Natural Resources Wales have been doggedly acquiring more of the bog, clearing smothering trees and bushes, damming ditches and installing storm-water control structures. SWT mirrored this on the smaller Wem Moss, at the south of the peat body. The knowledge of our local team of ex-peatcutters, particularly Bill Allmark, and Andrew and Paul Huxley, has been invaluable in understanding how to reconstruct the Mosses.

In 2016, a land-purchase opportunity led to a successful funding bid by a partnership of Natural England, NRW and SWT for the five-year, €7-million European and Heritage Lottery-funded Marches Mosses BogLIFE Project, which aims to make a step change in the rate of rewilding of the Mosses.

Importantly, the project addresses a problem affecting all British raised mires – the loss of our mire-edge ‘lagg’ (fen, carr and swamp communities), whose high-water table sustains the water table in the mire’s central expanse. Restoring the lagg involves buying marginal forests and woodland and clearing their smothering trees, buying fields, disconnecting their under-drainage, stripping their turf and reseeding with mire species. A new technique of linear cell damming or ‘bunding’ the peat then restores water levels. Lagg streams, canalised within the peat during the Enclosure Awards, to lower marginal water tables, will be moved back to the bog’s margin, so peats can be hydrologically re-united. And all without affecting our neighbours!

The project also involves adjusting dams on the central mire areas and bunding peats which haven’t got a cutting pattern to dam. The project even addresses clearing up the scrapyard and beginning to tackle the problem which is affecting most nature conservation sites nationally – high levels of aerial nitrogen pollution and, at the Moss, its consequent high coverage of purple moor-grass.

So why bother with this mammoth struggle on such a damaged peatland? In the 1980s, the main driver was biodiversity – its unusual bog wildlife, its cranberries, all three British sundew species, lesser bladderwort, white-beaked sedge, its raft spiders, large heath butterflies and moth communities, including Manchester treble-bar, silvery arches and argent and sable moth. Despite its devastation, this huge site provided corners for rare wildlife to hide in, waiting for the restoration of mire water tables. Today crucial bog-mosses have recolonised central areas and flagship species like the white-faced darter have been dragged back from the brink of extinction. Now, in spring, rare mire picture-winged species like Idioptera linnei dominate the cranefly community and the mire spider community is breaking national records. Regularly, invertebrate species, often new to either countries or counties, like micro-moth Ancyllis tineana, emerge from hiding, and the wetland bird community now is of national importance.

But today the driver for rewilding the Mosses is also restoration of the ecosystem services provided by a functioning bog – regulation of water quality and flow (particularly important with increasingly frequent flood events), re-pickling the bog’s vast carbon stores so their release doesn’t add to climate change and encouraging future carbon sequestration.

The growing pride for the restored Mosses in the local community and the increasing numbers of visitors from far afield, boosting the local economy, are a testament to the success of rewilding this quagmire and will be helped by further sensitive provision through the BogLIFE Project.

Wading through knee-high bog-moss on Clara Bog in central Ireland some years ago, brought home to me the potential resilience of bogs and their capacity to regenerate themselves after damage. The bog was acting like a giant shape-shifting amoeba: localised marginal drainage for domestic peatcutting had made the crown of the bog dome move, channelling more water and nutrients to a shrunken area, accelerating the accumulation of bog-moss and ultimately restoring the bog’s profile. Even at our devastated Marches Mosses, particularly with the challenges of climate change, the only viable option for the landscape seems to be a return to functioning raised bog. The bog is shrinking towards the lowered water table set by Enclosure Act culverts, making other land uses progressively less economically viable. Now forests fall down, marginal fields flood and pumping costs have become more expensive and cause further peat shrinkage.

Now, like at Fenn’s and Whixall, it is the time to capitalise on these devastating consequences of past drainage, to be bold, to grasp opportunities and to rewild our wetlands and regain their age-long benefits for all of us.

Curlew in flight.

Rewilding site, Kielderhead Nature Reserve.

Kielder’s Wilder Side (#ulink_a7bf0b79-08ea-5418-b0b3-c0942460537e)

Mike Pratt (#ulink_a7bf0b79-08ea-5418-b0b3-c0942460537e)

Kielder wildwood is a wilding project with an especially big ambition. It is a woodland restoration and creation project in its own right, but is also conceived as a means to a much greater goal – that of integrating degrees of restored natural processes across the vast landscape of forest and open land between Whitelee Moor on the Scottish border and the whole of the wider Kielder Forest and Water Park landscape. Indeed, the wider vision is to extend this wilding approach across the Scottish border and to complement the already largely rewilded Border Mires – one of the largest restored peatscapes in England.

Thus, we are working with our partner landowners the Forestry Commission and Kielderhead (cross-border) Committee and others, to make all of the area wilder by degrees, recognising that even within the commercial forestry areas, there are already integrated wild lands, such as impressive riparian corridors. If nothing else, this Kielderhead wildwood concept is ambitious and certainly landscape-scale – more a ‘future proofing’, area-wide approach, than a mere project.

Part of the vision is very much about creating a ‘forest for the future’, a more natural, open montane woodland of mainly native species, with a more complete ecosystem over the longer term. Initially, this will focus on a 94 ha area of the Scaup Burn valley, which will be planted with 39,000 trees over three seasons, all by volunteers.

We recognise we are starting not in prehistory but in the twenty-first century, in a commercially important, working forest context and we have reasonable acceptance of this in species-mix selection, management and establishment techniques.

This vast area of open land runs for over 8,000 ha up to the Scottish border. Today many of the hillsides beyond where plantation forest is still maintained are devoid of trees and, because the blanket bogs on top of the moors are important open landscapes in themselves, tree cover is actively discouraged. Large areas have special conservation designations to protect their special habitats and species, though often such land has the marks of human interference, being prepared long ago for possible forestry use.

The idea is to create ‘future-scape wildwood’, which has elements of species and habitat that thrived in prehistoric times here when the ecosystem was more complete. We aim to plant locally appropriate species such as downy birch and rowan, willow (some of which is already recolonising areas), juniper and many other species.

People are closely involved, despite the area’s remoteness. We started gathering local seed early on, including from rare old pines, growing seedlings with a view to planting to local seed stock. We draw additional inspiration from historic and prehistoric perspectives locally.

One key feature is a group of old Scots pines, the ‘William’s Cleugh Pines’, long thought be possible remnants of ancient or even prehistoric lineage – if true, they would constitute the first confirmed specimens of native English Scots pine.

Genetic work that has been carried out is inconclusive, but nevertheless the possibility remains of Scots pine being a surviving component of prehistoric forests. Evidence of the ancient forests is seen in the peat beds underlying the site and exposed in banksides and the burn – a layer of horizontal forest dated to 7000 bce, including pollen and preserved evidence of pine.

In addition to this, a branch was discovered in the side of the burn that dated to the fourteenth century and clearly exhibited beaver activity! In these historic remains we have perhaps some historical precedent, if we needed it, to develop a restored and more natural ecosystem.

Thus far we have initiated a massive volunteer effort in the middle of nowhere and started the establishment phase – the rewilded landscape is already taking shape, with 7,000 trees planted in the first year. We bid for and won Heritage Lottery funding, which is now enabling staff, volunteer effort and material planting and development of the project. We’ve brought on board world-renowned experts and undertaken micro-propagation from those old pines.

We are also addressing the cultural resonances of this remote part of the Anglo-Scottish landscape, a disputed land for centuries and perhaps also in the future, as border politics have definitely not completely gone away. Allied to the wildwood project we have successfully undertaken the Restoring Ratty project, aiming to restore water voles to the catchment.

What then might the future look like in decades to come? Ecological change is a certainty, natural processes will be restored, more natural and complete ecosystems come into effect and this should include the restoration of absent species.

Despite the very man-made nature of Kielder Forest and Kielder Water, the scale and breadth of wooded and open habitats across the whole area makes for a very natural feel, similar in character to parts of Scandinavia, and it is already surprisingly diverse relative to other areas of the UK.

Kielder already carries significant populations of key species like red squirrel (largest population in England), roe deer, badger, tawny owl, otter, wild goat and now, once again, water vole. Pine marten are recolonising themselves, golden eagle have just been reintroduced over the border and we hope may re-establish. We have osprey and other rare raptors that have come in – and a very wide range of bird, amphibian, reptile, insect and plant species, as expected.

So, in the future it can be envisaged that this rich range of species will be strengthened and extended – and joined, eventually, by beaver and even, perhaps, wildcat and other larger predators and herbivores: judiciously reintroduced after proper inclusive consultation and preparation. Reintroduction of species is only a long-term aim here and not the prime focus of the wildwood and Kielder in these early stages. Habitat restoration and development, though, will tend to lead the way to this.

This is a large, potentially resilient, forest area and, as it becomes more naturalised, will develop a sophisticated ecology. Balanced against this will always be the needs of commercial forest interests and the views of local farmers, and communities who live here and manage large areas nearby for other complementary uses. They too are part of the developing ecology of a ‘Wilder Kielder’.

Oak woodland at sunset.

Minimum-Intervention Woodland Reserves (#ulink_089a17ec-b75a-5b01-ab37-64cdde8595a5)

Keith Kirby (#ulink_089a17ec-b75a-5b01-ab37-64cdde8595a5)

The composition and structure of British woods has been shaped by centuries of management. However, in the second half of the twentieth century many semi-natural woods were left alone, either deliberately set aside as minimum intervention reserves, or left largely unmanaged because there was no market for the timber. Most of these areas are small, typically a few tens of hectares; mostly young-mature stands with dense canopies.

Such reserve areas were set up in Wytham Woods under the guidance of Charles Elton, shortly after the woods were donated to Oxford University in 1942/3. He later commented:

It is … clear that Wytham Woods have not for many centuries been ‘virgin’, though if given the chance to do so they might well return to something resembling a natural woodland, even if this would be different in composition from the original Saxon forest. What could be more fascinating than to watch this happen and record its progress over a hundred years or more, armed with the methods of modern ecology?

(The Pattern of Animal Communities, 1966).