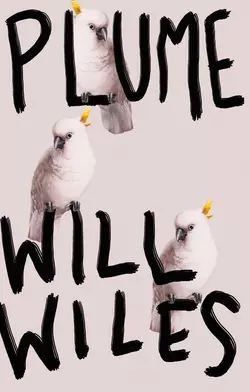

Plume

Will Wiles

The dark, doomy humour of Care of Wooden Floors mixed with the fantastical, anarchic sense of possibility of The Way Inn, brought together in a fast moving story set in contemporary London.Jack Bick is an interview journalist at a glossy lifestyle magazine. From his office window he can see a black column of smoke in the sky, the result of an industrial accident on the edge of the city. When Bick goes from being a high-functioning alcoholic to being a non-functioning alcoholic, his life goes into freefall, the smoke a harbinger of truth, an omen of personal apocalypse. An unpromising interview with Oliver Pierce, a reclusive cult novelist, unexpectedly yields a huge story, one that could save his job. But the novelist knows something about Bick, and the two men are drawn into a bizarre, violent partnership that is both an act of defiance against the changing city, and a surrender to its spreading darkness.With its rich emotional palette, Plume explores the relationship between truth and memory: personal truth, journalistic truth, novelistic truth. It is a surreal and mysterious exploration of the precariousness of life in modern London.

Copyright (#u12ebdc24-7568-5f1f-957f-b8f9476145db)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Will Wiles 2019

Cover design by Luke Bird

Cover illustration © Blue Jean Images / Alamy

Will Wiles asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears here (#litres_trial_promo).

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008194413

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008194420

Version: 2019-03-25

Dedication (#u12ebdc24-7568-5f1f-957f-b8f9476145db)

For my parents, with love.

Epigraph (#u12ebdc24-7568-5f1f-957f-b8f9476145db)

‘People begin to see that something more goes into the composition of a fine murder than two blockheads to kill and be killed — a knife — a purse — and a dark lane. Design, gentlemen, grouping, light and shade, poetry, sentiment, are now deemed indispensable to attempts of this nature.’

‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’

Thomas De Quincey

Contents

Cover (#u08e4147d-a5f5-5e28-a482-9befe979262c)

Title Page (#u9ac9b441-b925-58f6-8b95-55746e51bba4)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Will Wiles

About the Publisher

ONE (#u12ebdc24-7568-5f1f-957f-b8f9476145db)

We want beginnings. We want strong, obvious beginnings. Start late, finish early, that’s the advice from people who write magazine features. Ditch the scene-setting, background-illustrating and throat-clearing and get stuck in. It’s not a novel.

Lately, however, I’ve been fixated on beginnings, and their impossibility. I trace back and back through my life, trying to find the day, the hour I started to fail. Whenever I alight upon a plausible incident, where it might make sense to begin, I find causes and reasons and conditions and patterns that can be traced back further. And then I discover that I have gone back too far, that I have reached a point well before the event horizon of my failure, where the mass of it in my future overcomes any possibility of escape in the present. No fatal slip, or fatal sip.

Start late, finish early. Start with a bang. Later, a couple of my colleagues would claim that they heard the explosion. The rest would insist that it was too far away to be heard and that the others were mistaken.

I did not hear it. I felt it. The shockwave, widening and waning as it raced through east London, passed through my chair, through my notebook, through my phone, and through the people seated around the aquarium conference table. As it passed through me – through the acid wash of my gut, through raw, quivering membranes, through the poisoned fireworks of my brain – the wave registered as a shudder. It tripped a full-body quake, a cascade of involuntary movements beginning at the base of my spine and progressing out to my fingertips. These episodes had been getting worse lately, but I knew this was more than the usual shakes: as I felt the wave, I saw it. My eyes were focused on the glass of sparkling water in front of me. I had been trying to lose myself in its steady, pure, radio-telescope crackling. When the shock of the blast reached us, it had just enough strength to knock every bubble from the sides of the glass, and they all rose together in a rush. No one else reacted. No one else saw.

No ripple could be seen in the rectangular black pond of my phone, which was lying on the conference table in front of me. Within it, though, beneath its surface, ripples … But the Monday meeting had rules, strict rules, and my phone was silenced. Really, it should have been turned off, but I knew that it was on behind that finger-smeared glass, awaiting my activating caress.

‘Explosion’ was not my first thought. I guessed that a car had hit the building, or one nearby. These Victorian industrial relics all leaned up against each other, and interconnected and overlapped in unexpected ways. Strike one and the whole block might quiver. But it could have been nothing. Without the evidence of the glass in front of me, I might have believed that I had imagined the shock, or that it had taken place within me, a convulsion among my jangling nerves, and I had projected it onto the world.

Even the bubbles were no more than a wisp of proof that an Event had taken place; they were gone now, and no further indications had shown themselves. None of my colleagues had stirred – they were either discussing what to put in the magazine, or looking attentive. As was I. There were no shouts or sirens from the street, not that we’d hear them behind double glazing six storeys up.

But on the phone, though, through that window … Whatever had happened might now be filling that silent shingle with bright reaction. With a touch, I would be able to see if anyone else had heard, or felt, an impact or quake in east London; I would be able to ask that question of the crowd, and see who else was asking it. And I might be able to watch as an event in the world became an Event in the floodlit window-world – the window we use to look in, not out. It was magical seeing real news break online, from the first hesitant, confused notices to the deluge of report and response. An earthquake, a bomb, a celebrity death. And if you scrolled down, reached back, you could find the very first appearance of that Event in your feed or timeline, the threshold – the point where, for you, the Event began, the point at which the world changed a little. Or a lot. In front of me, in real time, the Event would be identified, located, named and photographed. And the real Event would generate shadow events, doppelhappens, mistaken impressions, malicious rumours, overreactions, conspiracy theories. More than merely watching, I would be participating, relaying what I had seen or heard or felt, recirculating the views of others if I thought they deserved it, trimming away error and boosting truth. Journalism, really, in its distributed twenty-first-century form.

(I sickened as I thought of the Upgrade, the digitisation effort taking place on the floor below, all those features I had written being plucked from their dusty, safe, obscure sarcophagus in the magazine’s archives, scanned, and run through text-recognition software. Soon they would be online. It couldn’t be stopped.)

Being denied the chance to check if an Event was indeed happening felt physical to me, withdrawal layered over withdrawal. The action would be so quick: a squeeze on the power button, dismiss the welcome screen, select the appropriate network from the platter of inviting icons on my home page. I no longer even saw those icons: the white bird of Twitter against its baby-blue background, the navy lower-case t of Tumblr, the mid-blue upper-case T of Tamesis, enclosed in a riverine bend. For something happening in London, Tamesis might be best, the smallest and the newest of those three. It had started as a way of finding bars and restaurants, and prospered on the eerie strength of its recommendations. But it was evolving into much more than that, rolling out new functions and abilities, constantly sucking in data from other networks, informing itself about the city and its users. If there had been a bomb, or a gas explosion, or even a significant car accident, Tamesis would know about it before most people, pulling in keywords and speculation from Twitter and Facebook and elsewhere, cross-checking and corroborating, and making informed guesses – preternaturally informed. Maybe that, really, was twenty-first-century journalism: done by an algorithm in a black box.

With the passing minutes the importance of the vibration diminished, but my desire to escape this room and dive into the messages, amusements and distractions of the phone only strengthened. It was right there in front of me, but inaccessible – Eddie would be greatly displeased. He was relaxed about a lot of things that might bother other bosses, but the no phones rule in the Monday meeting was sacrosanct, and I saw his point. Allow one, just for a second, and everyone would be on them the whole time. But the thought had taken root. Not only was I cut off from the sparkling constellation of others, I was cut off from myself, the online me, the one who didn’t tremor and sicken at 11 a.m. on a Monday morning, the one who charmed and kept regular hours and lived a fascinating life, not this shambles who sweltered in the aquarium. The old image of life after death was the ghost, which inhabited without occupying, and observed without possessing or influencing. But here I was, in this meeting, alive and a ghost. Death, I imagined, would be more akin to being stuck on the outside of an unpowered screen – the world still blazing away there, wherever there was, but imprisoned behind vitrified smoke.

If I could be reunited with that shining soul behind the glass, though, the happy success, not the ailing failure, I could check in with the others – Kay, for instance, sitting across from me but looking at Eddie, as mute and inaccessible as my phone. I could send her a message, see what she had been saying on Twitter, Tamesis, Facebook, Instagram … I doubted there would be anything to see. I greatly preferred the other version of me who would be doing the looking, though, the assurance and charisma of his interactions with others. He had no hands that might shake or knees that might buckle. His visage appeared only behind moody filters, hiding the sweat and pallor. He was always on his way somewhere interesting, not fleeing rooms full of people. What would become of that Jack Bick when this one was finished? I wondered. His was the greater tragedy. He had not brought failure upon himself. How I wanted to be in his company, but how bittersweet I now found those times together. It was like seeing an attractive house from a train window and thinking, Yes, what a fine place to live – and realising that the railway line ran right past its windows, the passing trains full of strangers gawping in. This was the relationship between my online and my offline. The phone is the dark reflecting pool for the monument of the self.

‘Jack?’

Kay was looking at me now, and so was Freya, and so were the Rays, and Ilse, and Mohit and the others. They were all looking at me. Eddie was looking at me – he had spoken.

‘You with us, buddy?’ Eddie said, and some of the others laughed. I forced a smile.

‘Feature profile,’ Eddie continued. Everyone looking.

How must I look to them? I wonder: the thin layer of greasy sweat pushed up by the warmth of the aquarium, the unlaundered shirt over an unlaundered T-shirt, unshowered and unshaved on a Monday morning. Was there odour? The air around me could not be trusted; I feared the tell-tale vapours that might be creeping into it. My index finger was resting on the rim of my glass, where I had been watching for tremors and thinking about the bubbles.

‘Something just happened …’

Thirty or so eyes on me. No one spoke.

‘Did anyone feel that?’

No one spoke.

‘Feature, profile,’ Eddie said. ‘What do you got for us, Jack?’ He enunciated this carefully, savouring the carefully remixed syntax.

The really bad part was that I actually had an answer to this, I was in fact prepared, but I had completely tuned out while Freya was talking, lost in ascending bubbles and the vibrating gulf between the icy crystalline world of the water and me, its observer, a low-voltage battery made by coiling an acid-coated length of bowel around a spine filled with tinfoil and bad cartilage. I searched for the correct page in my notebook, sweat prickling.

‘Oliver Pierce,’ I said.

One of the Rays pulled their head back, an almost-nod of recognition. Ilse appeared to tighten. Kay smiled, though only specialist devices aboard the Hubble Space Telescope could have detected it. The others did not react.

‘The mugging guy,’ Eddie said.

‘Yes, the mugging guy.’

‘He’s been interviewed a lot.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘He was interviewed a lot, when the mugging book came out. But he hasn’t said anything to anyone in years. Not a word. Deleted his Twitter, doesn’t answer emails …’

‘Does he have a book coming out?’

‘No,’ I said, too quickly, a mistake. Then, scrambling to recover: ‘Well, he must have been working on something – when I—’

‘Maybe he’s got nothing to say,’ Eddie said. ‘No book, no hook. How do we make it urgent?’

‘He must have been working on something …’

‘I haven’t even seen any pieces by him lately,’ Freya said. She was as bright-lit as the rest of us, but it was as if she had stepped from the shadows. I had tuned out of the meeting during a lengthy argument about feature lifestyle, her domain. We used to have a food correspondent, but after she left, food was added to Freya’s brief. Freya hated food. Her one idea had been a feature about the next big thing in grains – trying to sniff out the next quinoa, the spelt-in-waiting – which Eddie, Polly and Ilse had united in hating. Boring, impossible to illustrate. It had been a bruising business for Freya, and part of her recovery was to try to make someone else’s ideas and preparation look worse than hers had been. That someone would be me. Every month the flatplan served me up after Freya, a convenient victim if the meeting had gone badly for her. Unless I booked an interview high-profile enough to lead the feature section (not for a while now), feature profile followed feature lifestyle like chicken bones in the gutter followed Friday night.

‘Nothing on Vice,’ Freya continued, ‘nothing in Tank. What if he’s blocked or something?’

Pain, a steady drizzle behind my eyes. The quake visited my right hand, which was resting on the table in front of me, on top of my pen. I stopped it by picking up the pen and making a fist around it. The aquarium air was acrid in my sinuses, impure. What time was it? The Need wanted to know. I had to push on.

‘Isn’t that interesting in itself?’ I asked, emphasising with the pen-holding hand, keeping it moving until the quake subsided. ‘A writer has a smash hit like that mugging book. Big surprise. Awards. Colour supplements. Then, he goes Pynchon. Recluse. Emails bounce. Changes mobile number. Why? Isn’t that worth a follow-up?’

‘But he’s not a recluse,’ Eddie said. ‘He’s talking to you. Why’s that?’

I wished I knew. ‘He must have something to say.’

‘There were loads of interviews when that book came out,’ Freya said. There was brightness in her tone, no obvious malice, but I knew her game. She was trying to smear my pitch. And as she spoke, it was as if I could detect the gaseous content of each word, the carbon dioxide in each treacherous exhalation, subtracting from the breathable air in the room, adding to the fog around me. ‘And besides … A novelist … Not much visual appeal.’ She pursed her lips into a red spot of disapproval.

No one else spoke. Eddie pushed back in his chair. ‘When are you meeting him?’

‘Tomorrow,’ I said. ‘Morning. Tomorrow morning.’

‘Let’s have a back-up,’ Eddie said. ‘I want you to meet Alexander De Chauncey.’

An action took me without my willing it, an autonomous protest from my body. My head fell back and my eyes rolled; my lower jaw sagged; and I made a noise: ‘Euuhhhh …’

Another boss might have regarded this as insolence – it was insolence, after all, a momentary lapse into teenage rebellion, not calculated but real – and hit back hard, but this was Eddie, our friend. He smiled at it. ‘Look, I know you don’t rate the guy …’

‘He’s a prick.’

‘Have you met him? You wouldn’t say that if you met him. Ivan introduced us. He’s actually a great guy. Fun, creative, down-to-earth. An ideas guy.’

‘He’s a fucking estate agent.’

Eddie was away, fizzing with enthusiasm for his own proposal. ‘That’s the angle. An estate agent, but a new breed. Young, hip, creative. Progressive. One of us, you know? Not one of them. He’s got some really amazing ideas. You’ll love him.’

Every particle of my body screamed with cosmic certainty that I would hate him. ‘Maybe next month?’

The change in Eddie’s manner was so slight that perhaps only half the people in the room picked up on it, if they were paying attention: a hardening, a cooling. ‘What, you’re too busy this month?’ A chuckle from the ones who had detected the change in Eddie-weather. ‘Look, it’s win-win, Jack. If your mugging guy pays off we can go large on him and maybe hold De Chauncey for next month. It won’t hurt you to have one in the bag, to get ahead of yourself. If mugging guy is so-so, we do both. If Mr Mugging is a dud, we do De Chauncey. Yeah?’

There was no real question at the end of Eddie’s statement – more a choice between consenting by saying something or consenting by staying quiet. I chose to stay quiet. Eddie turned to his flatplan and struck out six spreads, over which he scrawled PROFILE PIERCE? / ALEX. The spread after this block he put an X through.

The flatplan was the map of the magazine – a blank A3 grid of paired boxes indicating double-page spreads, used to plot out the sequence of stories, features and adverts, letting editors decide the distribution and balance of contents: too word-heavy or too picture-heavy? Are there deserts to be populated or slums to be aerated? Editors, not generally a whimsical breed, often attribute mystical properties to the ‘art’ of flatplanning. They talk – their eyes drifting to the middle distance – of matching ‘light’ and ‘dark’, of rhythm and counterpoint, and the magazine’s ‘centre of gravity’, its terrain, its movement. But basically, the flatplan is a simple graphical tool and can be mercilessly blunt in what it shows.

Those Xed-out spreads that came between features were advertising. And each of those ads would be for a high-status brand – BMW, Breitling, Paul Smith – appropriate to the magazine’s luxury-lifestyle brief. One spread, very occasionally two, between each feature. No one commented on that, as if it had always been that way. But when I had started at the magazine there had been three or four ad spreads between features. Sometimes ad spreads would interrupt features. Advertisers would insert their own magazines and sponsored supplements into ours. The ads would experiment and try freakish new forms. They would have sachets of moisturiser glued to them, or fold-out strips reeking of perfume, or the page would be an authentic sample of textured designer wallpaper or a hologram or it would come with 3D specs. It had been quite normal for the magazine’s writers and editors to complain about the ads, about features getting swamped by them, about the magazine becoming cumbersome. We were afloat on a sea of gold, and whining it was too thick to paddle, that the shine of it hurt our eyes.

There were still grumbles about the adverts, but now they dwelled on quality, not quantity. Was this Australian lager, or that Korean automobile, really the kind of advertiser we wanted? Couldn’t the ad team do better? But Eddie was able to turn away these gripes with a sympathetic yet helpless shrug – a shrug that said, ‘I know, but what can you do?’ – and no one pushed past that.

Every year there were fewer of us to complain.

Ilse was unhappy with the inclusions, the loose advertising leaflets tucked into the magazine. One was a sealed envelope printed with a black and white photograph of a child’s face, dirty and miserable. Underneath the face was the message IF YOU THROW THIS AWAY, MIRA MAY DIE.

‘This kid, I don’t know – this kid is threatening me? They are holding a gun to this kid and threatening it? It’s a threat?’

‘It’s a charity appeal,’ Kay said. ‘They are just trying to create some urgency.’

‘It is ugly,’ Ilse said. ‘Not the photograph, a good photograph I suppose, lettering fine, but what they are saying with this is ugly, it is a threat. When I open my magazine, my beautiful magazine’ – she acted this out, closing last month’s edition on the envelope, then opening it again – ‘and, oh my goodness, this kid, I don’t even know. It is not the correct mood.’

Eddie pushed a hand into his thick black curls. Ilse had been with the magazine longer than anyone except him, and along with him was the only surviving remnant of the Errol era. Dutch, brittle, she had a temper that was the basis of several office legends: that she was unsackable, that she had once hit a sub-editor with a computer mouse, that her giant desk was not a reflection of her status as art director but rather an exclusion zone established to keep the peace. When I was new, before the office became the roomy, under-populated space it was now, I had to sit near Ilse for two days while the wall behind my desk was repainted. Two days of terrified silence. On the second day, I ate lunch at my desk and for some reason – a self-destructive, reckless impulse, a death wish – that lunch included a packet of Hula Hoops. As I crunched my way through the fourth or fifth Hula Hoop, I became aware of eyes focused through steel-framed glass, of pale skin taut over sharp cheekbones. She said nothing, just looked. The remainder of the pack I softened in my mouth before chewing. It took about an hour and twenty minutes to finish them all.

This was back at the beginning of my time, and it was commonly held that she had mellowed. Recent budget cuts she had borne with (public) silence, if not good grace. Nevertheless, art directors are dangerous as a breed. They spend too much time playing with scalpels. Here we are in the age of Adobe Indesign and Photoshop, and still they won’t be separated from those vicious little blades that come wrapped in wax paper like sticks of gum, and those surgical green rubber cutting boards. Why, if not for murder? Or at least recreational torture.

Before Eddie could answer, Freya spoke. ‘Last month it was the National Trust. That seems off, to me. I mean, stately homes?’ She threw up her hands and grimaced.

Eddie smiled. ‘Good high-quality product. Not starving kiddies.’

‘But it’s just so Boden. Where do we draw the line? Those fucking catalogues of William Morris shawls and ceramic owls and reproduction Victorian thimbles?’

‘If their money’s green,’ Eddie said with a teasing little shrug, clearly relieved to be arguing with Freya and not Ilse, who could thus be answered by proxy. ‘Look, these pay, and quite frankly beggars can’t be choosers. You want to sit in on one of my meetings with the ad team. You don’t want.’

One of Eddie’s tics – along with the suffering-in-silence hands-in-the-hair – was starting sentences with the word ‘look’. You could see why he liked it: there was that note of Blairish candour, of plain dealing. It insisted on your attention and assent. But it was also a tell. It cropped up when he felt a discussion was not going his way. When he felt, for whatever reason, that he was not being sufficiently convincing. This was a double-look.

‘Look, they’re not going to do anyone any harm, they’re not going to kill anyone. You might not like them, I don’t care for them, but we need them.’

A silence fell.

‘Is that everything?’

Polly, the deputy editor, whispered, ‘Friday …’

‘Aha, Friday, yes,’ he said as he caught her eye. ‘A reminder of what we agreed last week: I’m not here next week, so the next Monday meeting will be on Friday, and it’s an important one. Has everyone kept the morning free?’

There were nods and mumbles of agreement. The change in schedule had been mentioned at the last Monday meeting, and its importance had been emphasised. Since then, it had been much discussed, out of Eddie and Polly’s hearing, in quiet, nervous huddles. Eddie or no Eddie, the Monday meeting was sacred. When Eddie was away, Polly took his place, and the meeting went on. A Monday meeting on Friday was a patent absurdity, and an ill omen. But how to express the suspicions of the group?

After a tense silence, Kay spoke, and was direct. ‘Are there going to be redundancies?’ Seeing Eddie wince, she added, ‘I don’t like to ask, no one does, but we’re all thinking about it and, frankly, the atmosphere is beginning to get a little stifling.’

Stifling was about right. Could Kay see it too? The room was filling with smoke, slowly, silently. It was going to choke us all, me first, unless we got out. No one else appeared to notice it – was it not affecting them, or was it killing them invisibly, undetectably, like carbon monoxide? No, I reasoned, probably not them, they would be just fine. The smoke was for me alone, it would fill my lungs and drag me down, and I would end right here in front of everyone before Eddie rapped the table with his knuckles and said, ‘That’s it.’ How would they react if I expired in the middle of the Monday meeting? Would they be sad, would there be a tasteful black-border tribute in the next issue, using that photo they took last month for the new website? Or the other photo, the one from four years ago when I was entered for an award, the one with the puppy fat and the smile, not the gaunt, hollow-eyed creature I had become. I feared the new picture, crisp shadows in 8-bit greyscale.

Or would the expressions of grief be limited to: ‘Sadly Jack has let us down again, so we have ten pages to fill …’

My death might save Eddie a redundancy. Kay was right. She had asked the question we all feared to, the question we asked each other when Eddie wasn’t present, preferring to swap ignorant speculation for an actual answer.

‘Look,’ Eddie said, grabbing a fistful of his hair as he spoke, ‘I’m not going to sugar-coat it. It’s tough. Tougher than it’s ever been. But I promise you I will do everything it takes to avoid … having to do anything like that.’

He looked around the table, carefully making eye contact with each of us in turn. Freya, at his left hand, was reached last, and she did not raise her eyes from her pad, where an extensive pattern of angry spirals had appeared.

‘So for the time being the inserts stay,’ Eddie continued. ‘We’ll just have to live with them. Even those fucking pewter eggcups, if it comes to that, God help us.’

A couple of people managed to chuckle. Eddie rapped his knuckles against the table. ‘OK. Friday then. That’s all.’ And the meeting broke up, like a cloud dispersing.

In spite of my desperation, I did not immediately rise from my seat, fearful of wobbling in front of the others. Polly had been sitting at Eddie’s right hand, on my side of the table, and my view of her had been blocked during the meeting by Ilse and Mohit. As the others left the aquarium, she was revealed. And she was staring right at me, chair swivelled in my direction, no trace of a smile. Her clipboard, a stainless-steel thing that was in effect a corporate logo for Brand Polly, lay on her lap. At first I thought she was going to speak to me, so I turned my own chair her way and looked attentive, trying to straighten up and compose myself. But she said nothing, and just stared at me, as if I were an inanimate object that presented a problem; a knackered sofa that needed to be taken to the dump, for instance. She was still staring as she stood, and only looked away when she reached the door and left the meeting room.

My head swam. I had to get out.

It was a relief to be out of the aquarium, out of the meeting, but I was not free yet. The earliest, the absolute earliest, I could justifiably leave for lunch was after noon, and it had only turned eleven thirty. The Monday meetings used to start at nine thirty sharp and had been known to run until one or even two. Now they started at ten and rarely ran past twelve. Fewer pages to fill, smaller, simpler flatplans, less international travel to coordinate in the diary, fewer voices around the table. Today we hadn’t even started until ten fifteen – my fault, I had been late.

I wanted to talk to Eddie, to try to excuse myself from the office until Friday. That was the one advantage of being expected to do two interviews: I could justifiably work from home all this week and perhaps half of next week, in theory using the time to meet the subjects, type up the transcripts and then write the pieces. And other things.

But Eddie was talking with Polly in his ‘office’. This was not truly a separate room, more a stockade in the corner of our open-plan expanse, made more private by metal archive cabinets on one side and chest-high acoustic panels on the other. The publisher – who had a very nice office – had fixed ideas about editors working in the midst of their staff. And so it had been, back in the Errol days: he had a big desk opposite Ilse, right in the middle of the floor, surrounded by his team. By the time I started on the magazine, Eddie had migrated to the corner. The archive cabinets and acoustic panels had appeared during a reorganisation a couple of years ago, a reorganisation made possible by our declining numbers. We would tease Eddie about his fortress, and he would tease back, saying he needed a bit of space to himself, to give him a break from all of us. Then those deep, gentle brown eyes would turn serious, perhaps even a little sorrowful, and he would say that sometimes people, us, came to him with delicate matters, sensitive personal or professional issues, and he wanted us to feel secure in doing that, to have some privacy. Really it was for our benefit, not his. And didn’t we prefer having a bit of distance from our boss? Not having him looking over our shoulder the whole time?

He really was an amazingly thoughtful guy. But he was talking with Polly, and it looked tense. Polly was holding her steel clipboard in Clipboard Pose #4: Body Armour, clutching it to her chest in crossed arms. As Eddie spoke, she gave a series of little nods to punctuate what he was saying, a human metronome on a slow beat. She was behind the De Chauncey stitch-up, I was certain of it. Two interviews – the injustice of it was planetary, galactic.

As if to confirm my private suspicions, she abruptly turned to leave Eddie’s office, and as she did so she looked straight at me. Our eyes connected, and something burned in hers, something that could be read as ruthlessness, or even cruelty.

Eddie looked up wearily as I entered his enclosure, announcing myself with a knock on the acoustic panel, a knock robbed of almost all its sound, reduced to a submarine bump. I had gone over as soon as Polly left, wanting to catch him before he picked up the phone or was detained by someone else.

‘Jack …’ he began, and his expression said, Never a quiet moment.

‘Eddie,’ I said. ‘These two interviews …’

He rolled his eyes. ‘No. Stop. We discussed this in the meeting. You’re doing both.’

‘It’s fine, that’s fine,’ I said, holding up my hands in surrender. There was a little armchair by Eddie’s desk for visitors to sit in but I chose to stand, as Polly had done. Business-like. On task. ‘I just want to make sure it’s OK to take the time I’ll need to do them properly. I’m seeing Pierce tomorrow, Wednesday for transcribing, then Thursday and Friday for writing. So if we arrange De Chauncey for Monday next week …’

‘No,’ Eddie said. He frowned, eyebrows coupling. ‘No. No. I’m not having you out of the office for two weeks, not when I’m out as well. You don’t need that much time. You’re meeting Pierce tomorrow morning, right?’

I nodded.

‘You can do De Chauncey in the afternoon, while you’re out. Transcribe both on Wednesday. On Thursday I can take a look at both transcripts, and we’ll know where we stand.’

I shifted from one foot to the other, uncomfortable. Standing suddenly felt like a lot of effort.

‘Come on,’ Eddie said. ‘Don’t give me this. I know you can do it, you used to do it all the time. Come Thursday, I want you back in the office, and we’ll make decisions about which feature to prioritise. I want clear progress before I go on leave, something I can have confidence in. Ready to show on Friday. Important day, Friday. Then you’ll have a clear run at writing, OK? Without me breathing down your neck.’

My ankles were doing a lot of extra work to keep me upright, I realised. I was being undermined – the pleasant sensation of the sand being sucked from under the soles of your feet by a receding wave on the beach, reborn as a nightmare. Undermined, yes, that was it – Polly digging away at my basis, unseen.

‘Sure,’ I said. I wished I had sat down when I came in – it might have looked less formal and professional, but there was nothing formal and professional about falling over.

‘Look, I don’t enjoy micromanaging you this way, but I also don’t enjoy it when you let us down, and when I have the others complaining that they have to pick up your slack.’

Polly – that had to mean Polly. Or Freya?

‘I don’t want a reprise of last month, or the month before,’ Eddie continued. ‘You were in the meeting this morning – it’s a tough time. The toughest. We can’t carry anyone. No passengers, get it? Need you up front, stoking coal.’

‘Sure,’ I said, squeezing out a smile. Had I been in the meeting? What had been said? It was a swirl already, nothing but half-gestures and loose words.

‘Great.’ Eddie smiled back, a comforting sight, which gave me hope I might make it out of his office and back to my chair without total collapse. ‘Pierce is a good catch. How did you get him?’

‘Uh, I’m a fan,’ I said. ‘Quin – F.A.Q. – put me in touch with him.’

‘The Tamesis guy? F.A.Q.?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I thought he wasn’t best pleased with us?’

I shrugged. ‘I smoothed him over.’

‘Anyway, Pierce could be great,’ Eddie said. Even in my depleted state, I noticed this was a bit more equivocal than ‘great catch’. ‘Get the goods from him, something new and exclusive, and you’ll have a great piece. Listen for a strong opening. Once you’ve got that the rest’ll write itself on the Tube home.’

‘Sure thing,’ I said, and my affirming smile took a little less effort.

‘Big week, then,’ Eddie said. He nudged his computer mouse, waking the screen, to indicate that the meeting was over. ‘Real chance to do something great. Make us all proud.’

‘Sure. Great. Thanks, Eddie.’

It was 12.04. That would do. I slipped out of the office. Having had my dreams for the rest of the week dashed, I had no desire to be interrupted over lunch, so I ‘accidentally’ left my phone on my desk. The bubbles, the vibration, had completely left me.

It was about ten to two when I returned. We were allowed an hour for lunch and I liked to do some generous rounding in my interpretation of that rule. Eddie was pretty relaxed and didn’t count the minutes. I figured that if it was twelve-something when I left and one-something when I returned, that’s an hour. The people who left at one wouldn’t be back yet, the people who left at twelve thirty would have only just returned. It was normally quite easy to slide back into the office without anyone paying attention to how long I had been gone.

Normally. Today, however, there was a small crowd of my colleagues gathered between my desk and the window: woman Ray, Polly, Mohit, Kay, Kim from promotions, and even a couple of golf wankers and craft weirdos from downstairs, whose names, of course, I did not know. My desk, with its dank heaps of notebooks and magazines, was not their focus, thank heavens. They were looking out of the window.

‘Walthamstow?’

‘Don’t be silly, Walthamstow’s over there. It’s the estuary somewhere.’

‘Royal Docks?’

‘City Airport? Oh God …’ A murmur of horror passed through the group; a couple of people covered their mouths.

We were on the sixth storey of an eight-storey building, and the windows on my side faced east, ‘offering’, as Wolfe / De Chauncey would put it, ‘panoramic views of east London and Docklands’. In the foreground were the roofs and tower cranes of Shoreditch; much further away, to the right, were the towers of Canary Wharf, and behind those the yellow masts of the O2 Arena; to the left, at about the same remove, you could make out a little of the Olympic Park. On a clear day you could see a distant, dark line of hills on the far right and in places the mercury glimmer of the river. But in winter a grimy white dome, twin to the Teflon tent in Greenwich, was clamped down on the city.

Today, however, a new landmark had appeared. A column of black smoke rose from the ill-defined low-rise muddle of the horizon city. Further out than the skyscrapers on the Isle of Dogs, it nevertheless bested them in height and weight. While their glass and steel edges blurred in the cold grey air, the smoke tower was crisp and shocking, appearing as the most solid structure in sight, an impression only strengthened by its slow distensions and convolutions. It was blackening the dome, pumping darkness into the pallid sky.

‘Not City,’ a voice said behind us. The other Ray, man Ray, was hunched at his Mac. ‘It’s on the BBC, just a couple of lines: fuel depot in Barking. Explosion and fire. Oh, that’s awful. It says here people are being evacuated.’

‘Better than being in danger,’ Polly said.

Ray shook his head. ‘But people aren’t evacuated. Places, buildings, neighbourhoods are evacuated. Evacuating people would mean scooping out their insides.’

‘And that’s the BBC?’ the other Ray asked. ‘Really, you expect better.’

Man Ray shook his head in sad agreement.

‘Are we in danger?’ Kim from promotions asked. ‘From – I don’t know – gases.’

‘I doubt it,’ Polly said. ‘It’s a good long way away. If they were evacuating here, they’d be evacuating half of London. It’s just a fire, a big fire.’

‘It’s drifting this way,’ Kim from promotions said.

‘It’s just smoke,’ Mohit said.

‘When did it happen?’ I asked. I had reached my desk, which put me to the rear of the group, and I don’t think that any of them noticed my approach. Their eyes were on the plume.

‘When did what happen?’

‘Ray said it was an explosion …’

‘It doesn’t say,’ Ray said. ‘This morning.’

‘I think I …’ How to explain about the bubbles? If I said I saw the explosion I would sound ridiculous. ‘I think I felt it … The vibration …’

‘The earth moved for you?’ Kay asked, and a couple of people chuckled, Mohit and a golf wanker.

‘Now you mention it,’ Ray – woman Ray – said, ‘I think I felt it too.’

This prompted a more general and impossible-to-transcribe group conversation about who thought they had heard or felt what, whether it was possible to feel anything at this distance, and so on. I didn’t contribute much, and the group’s focus, such as it was, broke away from me. But Polly was still looking at me, and I frowned back, trying to figure out what I had said or done to earn this special attention. Her eyes darted down to my desk, which I was leaning against. My right hand was resting on one of the stacks of papers that are permanently encroaching on my keyboard and work space. It was this heap that Polly had glanced at, just a pile of torn-off notes, newspapers and magazines like the others, but I saw the top sheet, the one pinned under my hand, was not in fact mine at all. It was a yellow leaf from an American legal pad, and it was clipped, with many others like it, to a steel clipboard, which must have been left there by its owner while she was distracted by the drama at the window.

‘Excuse me,’ Polly said, and she grabbed her clipboard out from under my hand just as I lifted it to see what was written on it. Then she flipped the pages that had been folded over the back of the board to cover the sheet I had seen. But I had seen it. Columns of numbers – dates, times. The lowest line, the only one I saw in detail, read:

MONDAY: 10.11 12.05

Then two blank columns. I knew immediately, instinctively, what was recorded there, and what it meant. It was the time I had arrived that morning, and the time I had left for lunch, with spaces left for the times I returned from lunch and left the office at the end of the day. Polly was recording my movements – my latenesses, my absences, the myriad small (and not so small) ways I was robbing the magazine of time. The purpose of this record was obvious: she was building a case for my dismissal.

I did my best to hide the fact that I had seen the numbers and guessed their meaning. Grey oblivion enclosed my panicking mind on all sides, squeezing in. I pulled the chair from under my desk and sat down heavily. Polly was no longer looking at me. Instead she was staring fixedly out of the window, jaw tense, clipboard clutched to chest, being scrupulous about not looking at me. The grey closed in, appearing in my peripheral vision, cutting off my oxygen. I hit the space bar to rouse my computer and that small action felt like an immense drain on my resources. Fainting was a real possibility. No air. Horrible implications were spreading outwards from what I had seen, a thickening miasma of betrayal and threat. Firing an employee was cheaper than making them redundant – perhaps that was Polly’s game. Perhaps she was collecting a dossier against me to spare someone else, a friend, an ally: Freya? Kay? Mohit? But of those names, none was more clearly on the axe list than mine. If I was already doomed, and they could save themselves that redundancy payment into the bargain …

Unread emails. Hundreds of new tweets. Fifty new Tumblr posts. I looked at the latter, not able to face the clamour of Twitter, and it was a good choice – calming. Attractive concrete ruins. Unusual bus shelters in Romania. Book covers from the 1970s. Silent gifs of pretty popstars. New Yorker cartoons. Feel-good homilies and great strings of people agreeing with heartfelt, bland statements against racism and injustice.

But the smoke was there, too. A camera-phone photograph on the blog of another magazine, showing the same plume we could see but over a different roofline. A much better photograph from the feed of Bunk, F.A.Q.’s company, taken from a higher angle and showing the column’s base, orange destruction under buckling industrial roofs, in a necklace of emergency-service blue lights.

More of my colleagues were returning from lunch, some unaware of what was going on in the east, others brimming with urgency, disappointed to find that we all knew about the fire already. There was a volatile, excitable atmosphere in the office. Having an unusual event like this, a news event, so very visible in front of us all was turning people into restless little broadcasters, vectors for the virus of knowing, eager to find audiences as yet uninfected with awareness of it. This floor of this building was dead, saturated, so the group broke up and the spectators went to their phones and their keyboards to email, tweet, update Tamesis, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat – transmit, transmit, tell, tell. And all with this weird glee, the perverse euphoria that accompanies any dramatic news event taking place nearby, even a terrible event. Any other day, I would be among them – I felt that rush, that fascination, but at a distance, behind a firewall of private pain – but all I could do was gaze at my screen, barely seeing, hand dead on my mouse.

‘Crazy.’

Polly was at my side. I had no idea how long she had been standing there, but I knew I had done nothing in that time, not the slightest movement.

‘What?’

She nodded at my screen. It was still showing the Bunk picture of the fire.

‘Crazy,’ she repeated. ‘I wonder how they got that shot? The high angle … Helicopter? From the look of it, it’s amazing no one was hurt.’

Her tone was pleasant – just a regular chat between co-workers, as if nothing had happened, or was about to happen. A very casual assassin.

‘Long lunch?’ she asked.

Aha, I thought, here we go. I patted the book I had taken with me – Pierce’s Murder Boards, decorated with a jolly fringe of fluorescent sticky bookmarks. ‘Was doing some background. Working. Notes. Ready for tomorrow.’

‘Oh, good.’ Polly appeared genuinely pleased by this, which only intensified my suspicion that a trap lay ahead. ‘Have you looked at your emails? I’ve set things up with De Chauncey’s people – 3 p.m. tomorrow, at their Shoreditch branch. Easy-peasy.’

‘Right,’ I said. Grim tidings, but it didn’t feel like the gut-shot I had been expecting. Her chirpiness was concealing something, I knew. Sure enough, the trap revealed itself. She adopted Clipboard Pose #2: Moses, supporting it with the left forearm and laying her right palm on the attached papers, as if drawing from them some inviolable truth.

‘I wonder if you could do something else for me?’

I didn’t reply. Maybe I shuddered.

‘I’m trying to do some planning. To see if we can get past living hand-to-mouth, as we have been. When you have a spare moment, do you think you could jot down some future subjects for profiles? Your top ten people you would like to interview for the magazine.’

‘The thing is, what with De Chauncey …’

‘Eddie’s keen to see this as well.’

‘I just spoke with Eddie.’

‘I think he said to help me out with the front? This is what I want you to do. Just this.’

I coughed, throat dry, and the action churned the liquid lunch in my stomach, acid frothing, rising.

‘Just give me your target list,’ Polly continued, no less sanguine. ‘You must have people you’re pursuing? Ideas? Ambitions?’

Once I did, sure. ‘Sure.’

‘Just stick ’em on a page and give them to me. Say by Friday? Then we can get planning for the future.’

‘Sure.’

‘Great!’ And she hurried away cheerfully, clipboard swinging like a scythe.

The photograph of the plume on my computer screen disappeared, replaced by the writhing rainbow tentacles of my screensaver. But I didn’t need photographs to see it. I could just raise my eyes to the window and look at the real thing: a tight black column at the bottom of the frame, an ominous addition to the dusty publishing trophies lined up on the sill; filling the sky at the top of the frame, choking out the light.

The tasks I had been set were impossible. Not for the others, but impossible for me. I knew I would not be able to do them. I knew that I was going to be fired. I knew the how, and I knew the when. And I already knew the why.

TWO (#u12ebdc24-7568-5f1f-957f-b8f9476145db)

Latenesses, absences, missed deadlines, empty pages. I knew how it looked. It looked idle. It looked like the work – the lack of work – of a man who no longer cared. No passengers, Eddie said. We can’t carry anyone. He wasn’t the sort of boss to crack the whip unless he had to. No, his methods were persuasion and consensus. But I could see the change in him. The moment was coming. The moment when I could no longer be excused, when the accumulating evidence toppled into a landslide that would sweep me away.

Facts, accumulating. Polly’s scrupulous notes, the implacable grid of the flatplan. Gather enough facts and you have the truth. But an interviewer, a profile journalist like myself, knows different. There are, for a start, too many facts. Far too many. Punch a name with even modest achievements into a search engine and back come hundreds, thousands, of relevant results. Search someone like Oliver Pierce or Francis Quin – someone who operated online, someone with a following, an active fan base – and there are tens of thousands if not more.

Add to that what you gather yourself. People have no idea how much they say in the course of a normal conversation. Talk to someone for an hour and the transcript can approach 5,000 words. Trim away all the worthless ‘yeahs’ and ‘umms’ and ‘I thinks’, cut all the bits where they’re ordering a drink or asking their PR how much time they have left, and unless they are the worst kind of drone celeb you will still have far more quotable material than can be squeezed into the 2–3,000 words you have been given to write.

So you select. You edit. And here the interview stops being photography and becomes impressionist painting. Ten quotes that make the subject look generous, warm and inspiring can be found in the transcript. The same transcript can yield ten quotes that make them sound weary, bitter and self-centred. The person remains the same, what they said remains the same, but they are seen through a series of funhouse mirrors, appearing first hypertrophied, then stunted, then undulating …

A correction. What they said does not remain the same, not quite. The interviewer does not merely prune, then select. They edit. People talk nonsense. They speak in fragments and non-sequiturs, they repeat themselves and omit. Sometimes they skip verbs, sometimes nouns. And by ‘they’ I mean we. We are all, always, skirting total aphasia, total nonsense. But we don’t mind, we don’t even hear it, because our inner editors smooth it all away in the hearing. The real evolutionary breakthrough was not the ability to speak – it was the ability to understand.

Record the unedited spew that is natural human speech and write it down word for word, and the result is unprintable. The subject would be furious if you put these words – their exact words – in their mouth. Rightly so. They’d sound like a babbling fool. The work needed to correct this impression – to make people sound as they believe they sound – isn’t slight. It goes far beyond cutting out the ‘umms’ and ‘ahhs’. It can entail wholesale reorganisation and rephrasing of what was said. In other words – in other words! – the writer must extract the ore of what was meant from the slag of what was spoken. Done correctly, the subject won’t believe a word has been changed.

Even after explaining these difficulties, admitting the fundamental elasticity of the truth, the professional profile journalist will still insist that truth is the very soul of their work. Their profile, they will claim, is a fair portrayal, or an authentic depiction of an encounter. But I was beginning to believe that a true portrayal of another person might not be possible – not because the truth was impossible to portray, but because there might not be any truth to expose. It might be that every man and woman is a fractal Janus, infinitely involuted, showing at least two faces at every level of magnification. It might be that every human encounter is a cryptogram impervious to codebreakers.

The data Polly had collected gave the impression of idleness. If she was in a position to fill in the widening gaps in my day, that impression would only grow stronger. Perhaps she had already guessed the truth. I have considered telling the truth. I have wondered what that would sound like, what I would say, and where I would begin. But even a straightforward statement of facts is not the truth, not the whole truth.

I am not idle. I work hard. I start early, I work through lunch, I work in the evening, I work late into the night. I work until I drop. When I am kept away from work, by the Monday morning meeting or by the quiet drink I enjoyed with Mohit that same evening, work was always on my mind.

Idle, no. Polly would not see, but it is there to see, out on the streets. You are outside a pub, queueing for a cashpoint, waiting for a bus. They approach and ask for money. Maybe they have a story they tell. Look at them – the stance, the gait, the eyes. Abject, yes. But not idle. No languor, no sloth. They are busy. They are on a deadline. They are working. Addiction is work, all-consuming, urgent work. And unlike my post at the magazine, the job security is total. Addiction will never fire me. It will never let me go.

It was true that I was often late for work. But I overslept less than you might expect – I was rarely given the chance, rising promptly, at 7 a.m., when the drilling started. Next door was renovating their house. Renovate: to make new again. They were stripping that word back to its roots just as they were rebuilding their house down to its foundations. Deep into the London clay they dug, scraping out precious extra inches of floor area and headroom. They were in my head-room too. Their busy pneumatic drills were working perhaps only feet – perhaps only inches – from where my head rested on an under-washed pillowcase. They might as well have been drilling inside my skull.

I no longer got hangovers. I was never sober enough. So perhaps the universe supplied the drilling as a substitute. All the oxygen was gone from the room already. There was air, but it could not nourish or sustain. And it was thick with dust, created and stirred up by the building work. Dark grey was encroaching in the corners of the window panes, smooth surfaces crackled beneath my fingertips. My nose was blocked.

Shower first, then breakfast, I thought. But the Need disagreed. You’ll have time for that later, it lied. Me first. Still wearing no more than the T-shirt and boxers I had slept in, I went to the fridge, took out a can of Stella, cracked it, and took a swig.

The grit and stain was washed from the recesses of my mouth. Cold brilliance. Appeased for the moment, the Need receded. The choking fog around me parted and I saw the leftovers from the previous night. Grey tatters of lettuce on a sauce-smeared, greasy plate, plain newspapers balled up nearby, seven empties crowded on the little table beside the sofa – none spilled. The cushions were piled up on one side of the sofa, still indented with the impression made by my reclining form. It was dark in the living room, but it was always dark in the living room. The only natural light came through the glass roof of the kitchen extension, and that was the depleted stuff that had found its way through the winter sky and down into a canyon between the backs of Victorian terraced houses. It was further filtered by the grime that had built up on the glass roof, and the branches of the neighbours’ lime tree.

‘Good morning,’ I said to the black skeleton of the tree. It dripped filth in response.

I started to pick up empties. One turned out to be two-thirds full, and the surprise weight almost caused it to slip from my unready fingers. Another, tucked behind the lamp on the table, had about a third left in it. How long had they been there? Were they from last night, or earlier? Three days was a gamble.

The empty empties I crushed and put in the recycling; the part-empties I left by the sink. Then I sat on the sofa. The drilling had not stopped, or even subsided, but I had a little insulation in my head now, and it was at the other end of the flat. And only on the one side, for now. I felt pretty good, relatively. The meeting with Pierce was set for eleven, a civilised time, and I wasn’t expected in the office until Thursday. That was an aeon away. All that mattered was not screwing up the Pierce interview – and I was unusually well-prepared. I had actually read Pierce’s books and many of his articles; that was the reason I wanted to interview him in the first place. I just had to focus and stick to it for a couple of days, and the Polly-threat might recede, give me some time and space to get my head together, to make some changes, stabilise things.

‘Getting myself back on track, yes indeed,’ I said to the tree. ‘What do you have to say about that? Two interviews today, and they’re both going to go great.’

It had nothing to say about that.

The TV and DVD player were on standby, not completely off; they had done this themselves during the night. So discreet, so obliging. I turned the TV on and switched to the news. London Blaze, said the red caption beside the crawl.

‘… real concern isn’t the fuel but some of the additives used in some of these related processes, which we understand were on the site.’ Not a newsreader voice but the unpolished, hesitant voice of an expert, speaking over pre-dawn helicopter footage of the fire, hungry orange squirts of flame, the smoke column like a thick black neck attached to a head that was buried in the ground, swallowing, chewing, consuming. Around it, a necklace of twinkling blue lights.

‘So just how concerned should we be?’ The interviewer, a female voice, cut in. I liked this question. I wanted to precisely calibrate my concern.

‘Well, as I say,’ the interviewee, a male voice, said, ‘it’s not really a question of the fuel but the other chemicals that may have been present; now we don’t know what these were exactly, not as yet, but we understand there were substantial quantities of material on the site, and some of these can be, well, you wouldn’t want to put them on your cornflakes, ha ha, but still the question as always is one of quantifying risk.’

One of those morning interviews, then, when the interviewee’s time isn’t particularly important and there are unending minutes to fill. Slightly informative noise had to be created to cover the real interest, the pictures. Not the helicopter any more: footage from the ground, also shot before dawn, of fire crews directing inadequate-looking streams of water into a pulsing orange hell, the ground a reflecting pool in which coiled hoses wallowed.

My can was half empty already, its comforting weight gone, its top warm. I returned to the kitchen and topped it up from the one-third-full can I had found behind the lamp. Waste not, want not. The coldness and fizz of the remaining half of the fresh lager would take care of the flatness and warmth of the older stuff. But as a precaution, I poured it through a metal tea-strainer I kept beside the sink. In the past there had been instances when I had watched, horrified, as a glob of mould had slipped from a too-far-gone can into perfectly good beer. It was heartbreaking to have to pour it all down the sink. And there had been times when I had not washed it away, and they were even worse. But the strainer, found in a charity shop, had been a useful investment. This time nothing was intercepted, and the found beer frothed in a reassuring way. I had three cans in the fridge. That would probably do me for the morning.

‘Chances of a serious reaction are one in a million, one in 10 million really,’ the television voice was saying.

‘Ten million people in London,’ I said to the TV, ‘so one poor bastard …’

I tried to drink from the refilled can, but misaligned the aperture with my mouth, dribbling beer down the front of my T-shirt.

‘Shit.’

I ran the back of my wrist across my chin. The drilling, which had paused for breath, chose that moment to resume. I hated the pauses in the drilling more than anything, because they invited the thought that the noise might have stopped for good, which was seldom the case. The builders on the other side were now making their own contribution: a hammer-blow, perhaps metal against metal, which repeated eight or nine times, then stopped, then started again. Through the flat, from the direction of the street, came the throat-clearing sound of a diesel engine and a steady rattle of machinery.

I threw the tree an angry glance. It was planted in next door’s back garden, another of their multiple insults. Through the splattered glass of the kitchen ceiling, I saw a flash of white in its black limbs.

A cockatoo, sitting in the tree, looking down at me.

No, not possible.

I changed my position to get a better view through one of the cleaner patches of grimy glass. The white shape ducked from view. I stepped back. There it was again – not a cockatoo, but a white plastic bag caught in the branches.

Pacing back to the sofa, I took my laptop from my shoulder bag and switched it on. The noise was intolerable, something had to be done. What, exactly, I did not know, and as a renter my options were limited.

To: dave@davestocktonlets.co.uk

Subject: Re: Re: NOISE

Hi Dave,

I had never met Dave, my landlord, but he was pleasant enough on email, if he replied. We had corresponded about the noise before and he made sympathetic sounds and said there was little he could do. But emailing him was my only outlet. The owners of the neighbouring houses were never around, of course – even when their homes weren’t the building sites they are now, I never saw them. Even if I could reach them, why would they do anything for me, a private tenant? I was simply nothing as far as they were concerned.

The email got no further than the salutation. Through the drilling, I heard an agitated rattling of my letterbox, then a triple chime on my doorbell. That special knock, this time in the morning, meant I knew at once who it was, and I groaned. Her, one of the ones from upstairs.

I wasn’t dressed but there was little point. The lager had soaked into the T-shirt and contributed to any pre-existing odours.

When I opened the front door I tried to stay mostly behind it. The icy air made me flinch. Her breath was fogging; she was dressed in running gear, a headband holding back dark blonde hair, her top a souvenir from the London School of Economics. She had been jogging on the spot, but stopped when I appeared, and took the headphones out of her ears.

‘Bella.’

‘Jack. Hi, you’re up!’ she said, surprised.

‘Every morning,’ I said. Bella had forced me out of bed on a couple of weekdays before the coming of the drills, and now she behaved as if I had a lie-in every day. If only I did. ‘Hard to sleep with the noise.’

‘I’ve been running,’ she said.

‘Cold,’ I said.

‘Are you in today?’

‘No, sorry.’

‘Really? Not at all?’ Bella said. She cocked her head to one side, a gesture that said: it’s OK, you can tell Bella, just admit that you will be lounging around in your flat all day and all will be well.

‘Really,’ I said. ‘I’m interviewing people.’

‘Ooh!’ she said, flashing her eyes wide. How did she get her lips to be so sparkly? Just looking at them made mine feel like sandpaper. The brick-dust was so thick in the air you could practically see it.

‘New job?’ she asked.

This took a moment to parse. ‘No. No! I’m interviewing people. For my job.’

She frowned. ‘To take over from you?’

I rubbed my eyes, feeling the grit in them. ‘No. I’m interviewing them for the magazine. The magazine I work for. In my job.’

‘Okey-dokey,’ she said, sceptical. ‘Will that take all day? Only we’re expecting a delivery.’

‘All day,’ I lied. ‘Can’t you get it delivered to your office?’

Her face pinched in consternation. ‘Ooh, no. It’s furniture.’

‘Sorry. Why did you arrange for it to be delivered today if you’re not going to be in?’

‘Well,’ she said with a little hauteur, ‘I expected you to be in.’

I felt that she had laid out a space for another sorry from me, but she wasn’t going to get it. ‘’Fraid not.’

She flicked her eyes downward and I made a small shuffle further behind the door.

Smiling brightly: ‘OK. You’re not dressed. I won’t keep you in the cold. Hope your interview goes well!’

I smiled back and started to close the door. She popped her earbuds back into her ears and turned towards the steps back up to the pavement.

‘Bella,’ I said, stopping her. ‘You guys own upstairs, don’t you?’

‘Sure,’ she said, as if startled by the implication that any other living arrangement could exist.

‘Have you complained to next door?’ I said. ‘Both next doors. About the noise. The building work.’

‘No,’ Bella said. ‘We’re out all day working, so …’

‘But, the dust,’ I said. ‘The dirt.’

She shrugged. ‘Thing is, it’s their property, isn’t it, so really they can do what they like with it.’

‘I guess so.’

In truth, I didn’t mind Bella as much as I might. She at least kept her low opinion of me heavily gilded with courtesy and cheer – I imagine she has no idea how she comes across. It’s him I can’t stand, Dan, her husband. A prime Mumford. I would happily murder Dan.

The front door sticks a little when it’s closed, and on occasion it needs a real bang to shut properly. This bang dislodged something from the letter flap, and this something fell with a turn that suggested the beat of a white wing.

A postcard from my parents: pretty toy-like buildings lined up on a picturesque quay. Could be anywhere. Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Stavanger, Lübeck. Five years ago, Dad had retired, and Mum had decided to join him. So this was victory, for them. They shared a belief – a widespread and wholesome belief – in the fixed path of virtue. School, as a path to University, as a path to a Proper Job (proper – an important qualifier, that). All this was the infrastructural spine that supported Marriage, Mortgage, Family and Responsibilities. But what was at the end of this path? What lay at the sun-touched horizon? What was the reward? Retirement, that’s what.

This might make them sound stuffy and orthodox – brittle mannequins of small-minded propriety cursed with a dissolute son. (My younger sister, a pharmaceutical chemist at Sheffield University, has done a little better at cleaving to the path.) Not true and not fair. They were never less than loving and supple in their accommodation of my occasional efforts to remove myself from the path. Their belief in the path manifested itself more subtly. Any unhappiness, for instance, could be diagnosed as deviation either past or planned. Miserable at school? I needed to treat it as a means to an end, the end being university. Restless and unmotivated at university? Again, its only purpose was as a step leading to the next step – head down, push on. Unable to save a mortgage deposit? Perhaps I should consider getting a more solid, more proper job – or moving back to Two Hours Away (by the faster train), the southern provincial city in which I was born. Love life problematic? Perhaps a Proper Job would yield more suitable candidates. None of this advice was delivered with self-righteousness or coercion, it was all meant honestly and kindly. And who could blame them for their belief in a system that had served them perfectly?

But just as the Correct Route Through Life had supplied its own built-in justifications, its completion had robbed it of purpose. My parents had spent their whole lives working dutifully, rewarded daily with the certitude that they were doing the right thing. The arrival of the real reward – comfortable retirement, two decent pensions, mortgage paid off, children through university and out of the house – had deprived them of the satisfaction of dogged, stately progress.

They went a little crazy.

When I was growing up, I never saw my parents argue. They disagreed at times, or frowned at each other, but never did they engage in that basic ritual of relationships, the big argument. Not in my sight, anyway. I have no inkling of what script discussions or creative disputes went on behind the scenes of their performance as Mum and Dad. But on stage, they were pros.

In the first year after their retirement, they argued: long, flamboyant arguments with epic scope, stirring chiaroscuro and elaborate, intertwined plots and subplots. Late in life, they found that they shared a gift for holding a really poisonous row.

They supplied their own reviews of these arguments. Ever since I turned eighteen, Dad had routinely taken me out for ‘a pint’ at the local pub. A pint, precisely: two half-pints of bitter, followed by a further two ordered with hints of wicked indulgence and declamations that that had never been the plan. After his retirement, those drinks turned into discussions of the arguments. ‘Your mum and I have been arguing a lot,’ he would say, every time, as if he didn’t say the same thing every time. He never criticised her, and I truly believe that it would never even occur to him to do so. But he would sadly acknowledge the fact of the arguments, without giving the slightest detail as to what might be causing them, and expect me to be sympathetic.

(My sister reported that she was getting the exact same from Mum, often at precisely the same moment. Mum did criticise Dad, but only in the vaguest, most all-encompassing terms: ‘Your Father!’, uttered as if his very existence was an affront we had all quietly tolerated for too long.)

Then, a transformation. After about a year of arguments, including the hellish Christmas of 2012, my parents decided they needed a holiday. For twenty-five years, French beaches had known their presence in the summer. Their knowledge of the French coast was probably rival to that of Allied high command, June 1944. But this time, in the spring of 2013, they went on a city break, to Brussels on the Eurostar.

They stayed four nights and I received three postcards. Dad ate a horse steak. Mum ate a waffle sold from a van. They were photographed in front of the Atomium, the Palais de Justice, the Tintin Museum, the restaurant where Dad ate the steak, the van from which Mum purchased the waffle, and the headquarters of the European Commission.

A mania took hold. An addiction, maybe. No city in Europe was safe. It didn’t really matter where this postcard came from, and I already knew the gist of what was written on the back. It would join a small pile of very similar postcards on the kitchen counter, next to a cork board thoroughly covered with a bright collage of classical columns, Gothic spires, Moorish palaces, Dutch gables and high pitched Nordic roofs.

The era of arguments came to an end. So began the era of city breaks.

Standing in the icy doorway for so long had completely thrown me off my stride. I opened another can of Stella, forgetting that I already had one on the go.

All the cans in the fridge were empty by the time I left the house, and so were the half-empty cans I had found. I would have to pick up more, but then I would have needed to make a run in any case. Three cans or fewer was completely insufficient, dangerous. The horrible thought that there was no alcohol in the flat would be at or near the front of my mind all day.

In other regards the morning was going well. I had showered, put on (mostly) clean clothes, and set out at a reasonable time. My bag was double-checked for all the things I needed: two digital voice recorders, my old one and my new one, and spare batteries for them. After the recent disaster with F.A.Q., I was taking no chances.

Also in the bag were Pierce’s books: two novels, the mugging book, and the cash-in collection of non-fiction that his publisher had put out the Christmas that the mugging book was at the top of every broadsheet ‘books of the year’ list. Actors, MPs, television historians, baking competition hosts, they all exerted themselves to overstate how luminous, powerful, searing, important, draining, life-affirming, etcetera, etcetera they had found Night Traffic. I felt quite resentful about all this, because I had been reading Pierce for years. My copy of Night Traffic was the softback Panhandler Press edition with the cheap cover art, not the classy Faber edition that appeared when the award shortlists and reviews started to pile up, and which is still inescapable on the Tube.

I had been reading Pierce since his first novel, Mile End Road, came out in 2009. This was a fairly conventional story of twenty-somethings finding love, losing it, finding it again and then losing it for a second and final time. But the few reviews it received praised its rendering of twenty-first-century London life and its (at the time) unusually realistic depiction of the mobile phone and social media habits of young Londoners. It was longlisted for a couple of prizes and did not trouble any bestseller charts.

Pierce’s second novel, Murder Boards, had the good fortune to appear just before the 2011 riots. To capitalise, the post-riot paperback was given a sensational cover, with a movie-like strapline: THE CITY IS ABOUT TO EXPLODE. This bore little relation to its contents, 500 pages of non-linear narrative and cut-up technique told from the multiple viewpoints of its spectral cast of characters. It was concerned – obsessed, really – with missing persons and unresolved crimes, and steeped in police jargon and the imagery and phrasing of TV news. At times, it appeared to be deliberately opaque and confusing, as if the reader were an investigator confronted with contradictory accounts of events and inscrutable enmity between characters, between reader and author, between author and reality, with the objective truth of the past unknowable. To give up on Murder Boards was to play Pierce’s game, to take on the role of the indifferent bystander, the grazing TV viewer, the desensitised inquisitor, the impatient and unsympathetic bureaucracy. The reader’s natural frustration with a long and frankly exhausting experimental novel was thus subverted. Read to the end or put the book down unfinished – either way, Pierce won. Reviewers were divided. One-third of them hailed Pierce as a genius, another third called him a charlatan. The remainder made it obvious they did not understand the book, and maybe had not even finished it, by playing it safe with cautious praise.

After the modest success of Mile End Road, Faber had poached Pierce from Panhandler and put out Murder Boards with much ballyhoo, but despite a brief life as an edgy fashion accessory and social media prop, it was a resounding commercial failure. Whatever happened, Pierce was back at Panhandler for his third book, Night Traffic. Maybe the big house took fright at the thought of releasing a long essay covering many of the same themes as the chunky, expensive literary novel that was stinking up its balance sheets.

But since the appearance of Murder Boards, Pierce had acquired a small and eager following, myself included. His post-riots essay for 3AM Magazine, ‘Beneath the Paving Stones, the Fire’, had circulated on Twitter and Tumblr for more than a month, and was republished by the New York Times. Pierce had been writing essays about London for years, but now his writing became more adventurous, more scandalous, and funnier. He was able to arrange gonzo escapades that other journalists – again, myself included – could only dream about. A night spent with criminal fly-tippers, dumping trash on street corners and narrowly evading the police. Searching for forgotten IRA arms caches in north London back gardens. A memorably hilarious excursion with three Russian heiresses, the daughters of Knightsbridge-resident oligarchs, to find and consume authentic East End jellied eels.

In the summer of 2012 – the ‘Olympic summer’, we journalists are now apparently bound by law to call it, although for me personally it has darker connotations – Night Traffic appeared. Short, extraordinary, explosive. Night Traffic was an account of an incident the previous year in which Pierce had been mugged by a group of youths, no more than teenagers, in a quiet part of his native east London. Finding Pierce’s mobile phone and about £20 in cash to be insufficient reward for their effort, the youths had shown the author a blade, marched him to a cashpoint and forced him to withdraw £300. He spent more than half an hour in their company, crashing through an immense range of emotions from outright terror to perverse bonhomie and back to terror. Afterwards he had been too traumatised to appreciate that he should report what had happened to the police. A dark week was spent shut up in his flat, turning the events of that night over and over in his head, before he realised that he did not want to report it after all. Instead he would compose his own report, tackle the matter as a writer, as a journalist. He returned to the scene during the day and at night, and retraced his steps. He tried to find witnesses. He searched for the youths, sitting out through the small hours. He tried to get CCTV footage of the incident, without success. And he found himself coming to a transgressive acceptance of what had happened: that his ordeal had been a natural part of the ecology of the city and the economy of the night, that it was all preordained and the product of order, not disorder – and, most controversially, that violence might be a salutary urban force, ‘the street seeking balance’.