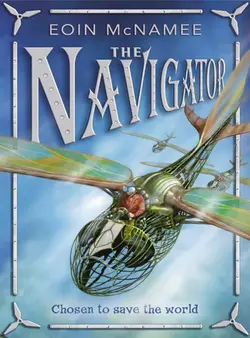

The Navigator

Eoin McNamee

Time travel adventure in which a boy joins a rebel uprising against a sinister enemy – ‘The Harsh’ – in order to repair the fabric of time.Owen's ordinary life is turned upside-down the day he gets involved with the Resisters and their centuries-long feud with an ancient, evil race. The Harsh, with their icy blasts and relentless onslaught, have a single aim – to turn back time and eliminate all life. Unless they are stopped, everything Owen knows will vanish as if it has never been…But all is not as it seems in the rebel ranks. While Owen is accepted by new friends Cati and Wesley, and the eccentric Dr Diamond, others are suspicious of his motives. Could there be a Harsh spy in their midst? Where and what is the mysterious Mortmain, vital to their cause? And what was Owen’s father’s role in all this many years before?As he journeys to the frozen North on a mission of destruction, Owen comes to understand his own history and to face his destiny.

EOIN McNAMEE

THE NAVIGATOR

Dedication (#ulink_73f48a83-8eaf-5a91-b78c-cae5de26d4b8)

For Owen and Kathleen

Contents

Cover (#ud744fd3b-0528-5d8a-8a2c-e591aeb22825)

Title Page (#ude04d55c-408f-574e-9e13-b8059e5a347b)

Dedication (#u843efe76-24aa-592d-b47c-753ea0ab9cac)

CHAPTER ONE (#u7113a356-1405-507b-b1bf-582d73c523b8)

CHAPTER TWO (#u5e033e6f-f581-5c23-967e-c6307dfad1ad)

CHAPTER THREE (#u31356080-d84f-552e-8b22-a6f6645d77a4)

CHAPTER FOUR (#u4e49f15c-3b6b-59d7-8cb0-88071376fafd)

CHAPTER FIVE (#u7bc78ad9-b83a-5160-80cd-32d70d73dadf)

CHAPTER SIX (#uee9e896b-b014-5c03-b451-f530fede287d)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_d163c47f-3832-557f-be17-b3ffca26177b)

There was something different about the afternoon. It seemed dark although there wasn’t much cloud. It seemed cold although the sun shone. And the alder trees along the river stirred and shivered although the wind did not seem to blow. Owen came over the three fields and crossed the river just below the Workhouse on an old beech tree that had fallen several years before, climbing from branch to branch with his eyes almost closed, trying not to look down, even though he knew the river was narrow and sluggish at that point, and that there were many trailing branches to cling on to if he fell. Only when he reached the other side did he dare to look down, and even then the black, unreflecting surface seemed to be beckoning to him so that he turned away with a shudder.

He had woken early that morning. It was Saturday and he had tried to get back to sleep, but that hadn’t worked so he had got up and got dressed. Before his mother could wake, Owen had slipped out of the house and down to Mary White’s shop. Mary had run the shop for many years. It was small and packed with goods and very cosy, with good cooking smells coming from the kitchen behind. Mary, who was a shrewd but kindly woman, smiled at Owen when he came in. Before he had even asked, she handed him a packet of bacon, milk and half a dozen eggs. He had no money, but then he never had. Mary used to write down what he got in a little book, but now she didn’t even bother with that. As always, she could see his embarrassment.

“Stop looking so worried,” she said. “You’ll pay it back some day. Besides, you have to be fed, for all our sakes.”

She often said mysterious things like that, telling him that it was a pleasure and a privilege to look after him. Owen didn’t know what she meant, for no one else seemed to think that way. Sometimes, when he walked through the little town at the bottom of the hill, you would think he had a bad smell the way people shied away from him and whispered behind their hands. It was the same in school. Sometimes, it seemed the only reason that anybody ever talked to him was in order to start a fight. He knew that he had no father, and that his clothes were older and more worn than the other boys and girls at the school, but something seemed to run deeper than that.

“It’s not that they don’t like you,” Mary said, in her curious way. “They see something in you that both frightens them and attracts them as well. People don’t like things that they don’t understand.”

When Owen got back to the house, he cooked the bacon and eggs and took them up to his mother. She woke and smiled sleepily at him, as if awakened from a pleasant dream, then looked around her and frowned, as if bad old memories had come flooding back. He handed her the tray and she took it without thanking him, a vague, worried look on her face. She was like that most of the time now.

Then there was the photograph. It had been taken shortly after Owen had been born. His father was holding him in the crook of one arm, his other arm around Owen’s mother. He was dark-haired and strong and smiling. His mother was smiling as well. Even the baby was smiling. The sun shone on their faces and all was well with the world. After his father’s death, Owen’s mother had taken to carrying the photograph everywhere, looking at it so often that the edges had become frayed. As a reminder of happier times, he supposed. Then one day he noticed that she hadn’t looked at it. “Where is it?” he had asked gently. “Where is the photograph?”

She looked up at him. “I lost it,” she’d said, and her eyes were full of misery. “I put it down somewhere and I don’t remember…”

He made a bacon sandwich for himself and took it to his room where he sat on his wooden chest to eat it. The lock on the trunk was missing and it had never been opened. There was a name on it, J M Gobillard et Fils. It sounded strange and exotic and always made him wish that he was somewhere exciting. Owen knew that his father had brought it back from somewhere, and had insisted on it being put in his room, but that was all he knew about it.

He looked around. The only things he really owned in the world were in that room. The old chest. A guitar with broken strings. A dartboard. A set of cards and a battered CD player. There was a replica Spitfire hanging on fishing line from the ceiling. There were a few books on a broken bookcase, a pile of old jigsaws and a Game Boy.

Owen stood up on the chest and scrambled through the window and on to the branch of a sycamore tree. He swung expertly to the ground from a low branch and set off across the fields.

Owen crossed the burying banks below the mass of the old Workhouse and climbed the sloping bank, passing through the long, tree-lined gully that split the slope. It wasn’t that he was hiding from anyone. He just liked the idea of being able to move about the riverbank without anyone seeing him. So he found routes like the gully, or tunnels of hazel and rowan, or dips in the ground that rendered you suddenly invisible. The riverbank was ideal for this. There were ridges and trenches and deep depressions in the ground, as though the earth had been worked over again and again.

It took ten minutes to skirt the Workhouse. It was a tall, forbidding building of cut stone perched on an outcrop of rock which towered above the river. It had been derelict for many years and its roof had fallen in, but something about it made Owen shiver. He had asked many people about its history, but they seemed reluctant to talk. He had asked Mary White about it.

“I bet there are ghosts,” he said. She leaned forward in the gloom of her small shop and met his gaze with eyes that seemed suddenly stern and blue in a wrinkled face.

“No ghosts,” she had said, giving him a strange look. “No ghosts at the Workhouse. But there are other things. That place has been there longer than anyone thinks.”

It took another ten minutes to reach the Den. Owen checked the entrance as he did every time. A whitethorn bush was bent across it, tied with fishing line. Behind that he had built up a barrier of dried ferns and pieces of bush. The barriers were intact. He moved them carefully aside and rearranged them behind him. He found himself in a clearing just big enough to stand in. The space was lit from above by the sunlight passing through a thick roof of ferns and grass so that it was flooded with greenish light. In front of him was an old wooden door he had pulled from the river after the Winter floods. He had attached it to the stone doorway of the Den with leather hinges, but it was still stiff and took all his strength to open.

Inside, things were as he had left them. The Den was roughly two metres square, a room dug into the hillside, its roof supported by old roots. The floor was earth and the walls were a mixture of stones and soil. Owen had found it two years ago while looking for hazelnuts. He had cleared it of fallen earth and old branches, and had put an old piece of perspex in a gap in the roof. The roof was under an outgrowth of brambles halfway up the steep part of the slope and the perspex window was invisible while still providing the same greenish light as the space in front of the door.

He had furnished the Den with a sleeping bag and an old sofa that had been dumped beside the river. There were candles for Winter evenings, and a wooden box where he kept food. The walls were decorated with objects he had found around the river and in Johnston’s yard a quarter of a mile away across the fields. Johnston kept scrap cars and lorries and salvage from old trawlers from the harbour at the river mouth. Owen had often gone to Johnston’s, climbing the fence and hunting through the scrap. That was until Johnston had caught him. He winced at the memory. Johnston had hit him hard on the side of the head then laughed at him as he ran away.

Before that, Johnston used to come to the house three or four times a year, selling second-hand furniture, but he hadn’t been back since he’d caught Owen.

But that had been last year. Now Owen had a lorry wing mirror, a brass boat propeller, a car radio cassette and an old leather bus seat with the horsehair filling poking through. He had also found an old wooden dressing table painted pink. He looked at himself in the mirror as he passed. A thin face, his hair needing a cut. He had a wary look. His eyes a little older than they should be. He made a face at himself in the mirror and the eyes came alive then, youthful and dancing. He let the mask fall again and saw the same watchful face looking back.

He spent as much time as he could at the Den. Sometimes, he felt that people were watching him, whispering that he was the boy whose father had killed himself. Suicide, that was the word he heard. He could see it in people’s eyes when he went into shops. A strange boy. One day he heard a woman whisper behind him. “Like father like son.” “He’ll go the same way,” another voice said. Sometimes it was just easier to stay away from them.

Owen sat down heavily on the bus seat. He knew he was in trouble. He’d skipped school again that week and spent his day around the harbour where the river met the sea. He couldn’t help it. He kept being drawn back. And yet when he got close to the edge of the dock, he could feel the terrible panic welling up in him. The coldness, the heavy salt greenishness of the water filling his mouth and his lungs, and then the terrible blackness below. Each time he would come to as if he’d been asleep, finding himself many metres from the edge of the dock, his limbs trembling and his mouth dry.

It had been like that for as long as Owen could remember. He wanted to ask his mother if he’d always suffered from such fear, but she seemed so weighed down and lost in her own thoughts that she barely noticed him these days, and when he did ask a question she raised dull, lifeless eyes to him, staring at him as if she was struggling to remember who he was.

That was the worst thing of all, so he had stopped asking questions.

Owen emptied his bag. In the kitchen he had found some cheese and some chocolate biscuits. He took a magazine from the small pile that he kept in the Den. The cheese was a little stale and tasted odd with the chocolate biscuits, but he ate everything and washed it down with the milk. Outside, the wind sighed through the trees, but the Den was warm and dry. These are the best times, he thought to himself. No one knew where you were, but you were safe and warm in a secret place that no one else knew about but you.

He had found the Den a few years ago, when things were normal, or almost normal. Those were the days when he could talk to his mother. About most things, anyway. Except, of course, when he had tried to talk about his father. She would open her mouth as if to reply, but her eyes would cloud over and she’d turn away. But at least then they had been happy, living together in the small house. “Me and you, son,” she would say. “That’s how it is, me and you.” And he had been glad to have her. In school he had always been a loner. Not that anyone actually bothered him much. They just seemed to think that it was better if he went his way and they went theirs. Fine with him.

But then his mother started to change. She said that something in the house was “weighing on her”. That there was something in the air itself that left her unable to think straight. She started to forget things. Little things at first, then it seemed as if she forgot almost everything, wandering through the house, vague and forgetful.

Owen read on until the light changed, almost as if a rain cloud had arrived overhead, the light dark but silvery, so that he could still see the letters on the page. He listened for the sound of the rain falling, but there was nothing, not even the sound of the wind. In fact, a stillness seemed to have fallen outside, so complete that you couldn’t hear the sound of birds or insects. Owen decided to investigate. He slipped on his jacket and heaved the old door open. He was careful to replace the branches that hid the door, even though he was aware of their loud rustling in the still air. He paused. There was a sense of expectancy. He began to climb towards the old swing, which was the highest point overlooking the river.

It took ten minutes to get up to the level of the swing tree. The air itself was dense and heavy, and Owen was breathing hard. He skirted the ridge until he got to the swing. It was a piece of ship’s cable which had been hung from the branch of an ancient oak protruding over a sheer drop of fifty metres to the river. The rope part of the cable had almost rotted away to expose the woven steel core. No one knew who had climbed the branch to put the cable there, but Owen knew what it felt like to swing on it. It was both terrifying and exhilarating. You knew that if you lost your momentum or your grip there was nothing to save you from the long drop to the stones of the river far below. Local children had used it as a test of nerve for years. For Owen, it wasn’t the bone-crunching impact of the stones that he feared, but the clammy touch of the water.

For some reason he couldn’t explain he felt that there was someone watching. Almost without thinking, he crouched down behind a heap of old stones and peered out over the river. As he did so he saw a part of the bank below him start to move. At least he thought it was part of the bank, but as he looked closer he saw that it was in fact a man. He was wearing some kind of uniform, which might have been blue to begin with but was now faded to a greyish colour. There were no insignia on the uniform except for heavy epaulettes on the shoulders. The man’s hair was close-cropped and steely grey. In one hand was a narrow, metallic tube, almost gun-shaped, and on his belt there were oddly shaped objects – thick glass bulbs with narrow, blunt, metal ends.

There was something else strange about him and it took Owen a little while to work it out. Then he realised what it was. Even though the man was obviously fully grown he was barely a metre and a half tall and just a little taller than Owen himself. The man was staring intently across the river. A small knot of hazel trees on the slope meant that Owen couldn’t see what he was looking at, but a dip in the ground led towards the man’s position and Owen crept along it.

As he got closer, he could see how tense the man was, how his left hand gripped the metal tube so that his knuckles were white. As Owen drew level with him, he could see that he was looking in the direction of Johnston’s farm and scrapyard. Owen knew that Johnston’s scrapyard had been getting bigger, but he hadn’t looked at it for a long time and now he saw that it seemed to have expanded to cover field after field. At the fringes of the scrapyard he could see small black figures moving busily to and fro. And as he watched, a figure in white emerged from the fields of scrap and stood facing in the direction of the river. Owen heard a sudden intake of breath from the man in front of him.

“The Harsh!” he exclaimed then went silent as the cloaked figure raised his right hand in the air. Owen heard a voice that did not seem to be human, a cry that swelled and seemed to be both angry and triumphant, and full of youthful arrogance and ancient fury, a cry that seemed to flow like a raging river until Owen covered his ears and pressed his face to the ground.

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the cry stopped. Owen looked up. The man in front of him had not moved. If the cry had shaken him, he did not show it. He seemed to be waiting for something. The wind had stopped and every branch and leaf was still. The birds and insects made no sound. Even the noise of the river faded away into silence. The man waited and Owen waited with him. The silence seemed to stretch on and on. Owen’s muscles were taut and his hands were clenched into fists though he didn’t know why. And then it came, soundlessly and all-enveloping. A kind of dark flash, covering the sky in an instant, sweeping across the land and plunging everything momentarily into total blackness like the blackness before the world began. And then, just as suddenly, it was gone and the trees and grasses seemed to sigh, the very stones of the land seemed to sigh, as if something precious had gone for ever.

“It has begun,” the little man said softly to himself, his voice weary. And then there was another great cry, but this time filled with terrible triumph. Owen felt a chill run down his spine and he gasped. In a second, the man had turned and taken several swift steps towards him, brandishing the metal tube. But when Owen stood up, he stopped and rubbed his chin thoughtfully.

“So,” he said, as if to himself, “it is to be you. I suppose it had to be.”

Owen waited, suppressing the impulse to run. The man strode up to him and took him by the arm.

“We must hurry,” he said. “We have a lot to do.”

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d2791428-f9ec-56ac-9bfa-d2b3b1a7fc7d)

Owen didn’t resist. He felt completely bewildered. When the man released his arm he followed. They were going in the direction of the old Workhouse, the small man moving with great speed through the tangles of willow and hazel scrub along the river. After a few minutes, Owen realised that they were following faint paths through the undergrowth, paths that he had never noticed before, but that seemed to be well-travelled. Every so often, the man would disappear from sight, but he never got too far ahead. Owen would round a bend to find him waiting.

“What’s your name?” Owen said breathlessly as he hurried up to him for the third or fourth time.

“My name…” the man said, stroking his chin and leaning back against a tree as though the matter of his name was worth interrupting his headlong progress for, that it was something which merited sitting down and thinking about.

You either know your name or you don’t, Owen thought impatiently. “My name’s Owen,” he blurted out, hoping to hurry the man along.

“I know your name,” the man said in a tone which left Owen in no doubt that he was speaking the truth. “They call me the Sub-Commandant.”

A sudden cold breeze made the trees around them rustle. Owen shivered. The man straightened up quickly.

“Let’s go,” he said urgently and started out again. Owen followed, almost running.

After ten minutes they were close to the Workhouse. To Owen’s surprise the narrow paths had started to widen and there was fresh-cut foliage to either side of them. The grass had been stripped from the ground and he could see that the surface of the path underneath was cobbled. But that wasn’t all. As they approached the Workhouse, he could hear the sounds of people at work, hammers tapping, wood being sawn, the rumble of masonry. When he rounded the corner he stopped and blinked and rubbed his eyes in amazement. The side of the hill leading to the Workhouse was swarming with people, many of them wearing the same uniform as the Sub-Commandant. And instead of there being a smooth stone face, archways were beginning to appear in the rock. Archways and windows, more and more of them. Men were unblocking entrances and passing the stones from them from hand to hand down the cliff. Other men were using the cut stones to construct a wall at the bottom of the hill. In the oak wood on the other side of the Workhouse, teams of women were working with saws at the trees.

Owen realised that he had stopped walking and the Sub-Commandant was now far ahead. He started to run after him, but stopped again when he saw the Workhouse. There were people in every window, smoke rising from its chimneys, and from the highest window a black banner with nothing on it stirred in the cold wind.

He realised that he could no longer see the Sub-Commandant, and that people were casting curious glances at him. He moved forward, calmly at first and then with increasing panic. On a small rise in the shadow of the Workhouse he saw a man who seemed to be directing the work. He was much taller than the others and was wearing a black suit. The suit was shabby and worn through to the lining, but his hair was cropped and steely grey, and his deep-set, penetrating eyes told you that this was no tramp. As Owen stared at him, he saw the Sub-Commandant emerge from the crowd at the base of the rise. Owen started towards them. As he did so, the tall man turned and saw the Sub-Commandant. The two men looked into each other’s eyes for a long time, then the tall man strode forward and they embraced. Owen pushed through the people at the bottom of the rise. The tall man turned to look across the river, still holding the Sub-Commandant affectionately by the elbow.

“It has been a long sleep this time,” he said.

“It has been a long watch, Chancellor,” the Sub-Commandant replied.

“A long weary one, by your face,” the tall man said, glancing at him shrewdly.

“I am tired, but there’s no time for that. The Harsh have had a long time to prepare.”

“I was worried about that,” said the tall man. “We must be quick in our own preparations.”

The tall man’s eyes swept over the crowd until they reached Owen. It was almost a physical sensation; one that left him feeling uncomfortable, as if his most secret thoughts were suddenly visible. But just as suddenly the sensation stopped and the tall man’s eyes were sad.

“I suppose it had to be,” he said, sighing, “although I would have preferred somebody else.”

“These decisions aren’t in our hands,” the Sub-Commandant said.

“I know, but I hope we do not have to pay a price for it.”

Once again, Owen felt that searching gaze sweep over him.

Suddenly, a cry went up from the direction of the river. There was a flash of blue light and a sudden smell of burning in the air.

“It begins,” the Sub-Commandant said quietly.

“A feint, I would say, nothing more. But we have to be ready. I’ll talk to you later.”

The tall man grasped the Sub-Commandant’s shoulder and strode quickly off. Owen realised that he had moved up the hill as the two men spoke until he found himself standing beside the Sub-Commandant. Despite the man’s small stature, Owen had the sensation of being sheltered and protected, more so as the man rested his hand on his shoulder.

“I have a lot to do,” he murmured, then called, “Cati! Cati!”

A small figure detached itself from a group under the Workhouse walls and ran towards them. Despite the steepness of the slope, the figure came at full speed, taking great leaps and sliding dangerously on the scree. As the figure got closer Owen could see that it was a girl, her long black hair plaited at the back. She was wearing a uniform like the others, but it was covered in badges and brooches. Underneath a peaked cap, her hair was tied in brightly coloured braids. Her green eyes watched him warily.

“Cati,” the Sub-Commandant said, “I want you to look after young Owen here.”

“But I was going to go down to the forward posts, Father!” she exclaimed. “It looks like the Harsh are going to try to cross there!”

“There will be no crossing,” the Sub-Commandant said sternly. “At least not yet, but you must do what you are told, Cati. This is no time for disobedience, especially from you.”

The girl bit her lip. There were tears in her eyes and two bright points of colour burned high up on her cheeks.

“Yes, Father,” she said quietly. The Sub-Commandant turned to her and Owen could see his eyes soften. He put his hands on her shoulders and leaned his forehead against hers. Owen could not hear what he said, but the girl smiled and he could feel the current of warmth between them. The small man cupped the girl’s face in his hands and kissed her forehead, and then he turned and was gone. The girl turned to Owen.

“Now, young Owen,” she said, putting her hands on her hips, “I hope you’re a bit tougher than you look. Come on!” Without looking to see if he was following, she turned and ran back towards the Workhouse, swarming up the slope with fierce agility. Not having a choice, Owen followed. Even so, he found it hard to keep up with her.

As he ran, the workers looked up at him curiously, men and women dressed in many different uniforms. Some of them were grey and worn like the Sub-Commandant’s. Others were ornate and colourful. The faces that looked up at him were as varied. There were stern-looking people with straw-blond hair and hooked noses. There were smaller, dark men and women with a cheerful look in their eye who wore copper-coloured uniforms and looked as if they would be happier putting down their burdens and joining the two children. There were small, squat people, men with dark curly hair and beards, and others – so many that Owen’s head hurt.

“Where did everyone come from?” he said, catching up with Cati. “What’s happening? I mean…” He stopped. He didn’t know which questions to ask first. He felt a sudden impulse to return to the Den, pull the bushes over the entrance and hide. It was all too strange that one minute the riverbank should be just as it always was, and an hour later it looked like a huge armed outpost preparing for war.

“The people have awoken from the Sleep. Or some of them have,” Cati said as they passed a group of women who were looking around with dazed eyes, while others rubbed their hands and feet, softly calling their names.

“But where did you all come from? I mean you weren’t here an hour ago.”

“We were, you know. Two hours ago. Two years ago. Two hundred years ago. Asleep in the Starry.”

“What’s the Starry… ?” Owen began. But he couldn’t go on. There was too much to ask.

“Are you hungry?” Cati said. “Come on.” She turned sharply left and plunged through an ornate doorway made of a brassy metal with strange shapes etched into it; what seemed like a spindly, elongated aircraft with people sitting on top, tiny men with tubes like the one the Sub-Commandant had carried. There were tiny etched fires and people falling. Cati reached through the doorway and grabbed his shoulder. “Come on!”

Owen found himself on a wide stone stairway which spiralled downwards. Every few steps they met a man carrying a barrel or a box on his shoulder, or women walking with rolls of cloth and stores of one kind or another. They all smiled at Cati and she spoke to them by name. The stair seemed to go on for ever, until eventually it opened out into a broad corridor which appeared to be a main thoroughfare, for people of every kind were moving swiftly and purposefully through it. Owen felt dizzy. The corridor was lit with an eerie blue light, but he couldn’t see where it was coming from.

Cati dived through a side door and Owen found they were now in a vast kitchen. It stretched off into the distance, a place full of the hubbub of cooking, with giant ovens lining one wall, roof beams groaning under the weight of sides of beef and men stirring great pots. People were baking, stewing, carving, spitting, and all the time shouting and cursing, their faces shining with the heat. To one side of the kitchen, Owen saw a giant trapdoor lying open and a team of coopers opening endless barrels that were being passed up from what must have been a huge cellar below. He saw round cheeses with oil dripping from them, herrings pickled in brine, sides of bacon. There were barrels of honey and of biscuits, and casks of wine carried shoulder high across the kitchen. As he watched, Cati darted across the top of the barrels with a piece of bread in each hand. Before the men could react, she had thrust the bread into the honey and skipped away laughing.

“Here,” Cati said, thrusting one of the pieces of bread into his hand. The bread was warm and nutty, and the honey was rich and reminded him of hot Summer days spent running through heather moorlands.

“Hello, Contessa,” he heard Cati say. Owen turned to see a woman standing beside the girl. She was tall and slender, and her ash-blonde hair hung to her waist. She was wearing a plain white dress which fell to her ankles. Her eyes were grey and ageless. Despite the heat of the kitchen, her brow was smooth and dry, and despite all the cooking and frying and battering, there wasn’t a trace of a stain on her white dress.

“Hello, Wakeful,” the woman said. Her voice was deep and low.

“Contessa is in charge of food and cooking and things,” Cati said. “We have to live off supplies until we can plant and get hunting parties out.”

“Hunting parties?” Owen said, thinking of the neat fields and little town with its harbour and housing estates. “There’s nothing to hunt around here. I mean, it’s the twenty-first century. You buy stuff in shops.”

Cati and Contessa exchanged a look, then Cati reached out and touched Owen’s sleeve. Almost casually, she pushed her finger against the cloth and it gave way, ripping silently. Contessa and Cati exchanged a look. Owen stared, wondering why she had torn his sleeve, and how she had managed to do it so easily.

“I know it’s all very strange,” Contessa said gently, “but if you search in your heart, down deep, I think you’ll find that in a way, it mightn’t be so strange after all.”

Before he could answer, Cati leapt to her feet. “Quick!” she shouted, spraying them both with crumbs. “They’ll be raising the Nab. I nearly forgot. Come on!” Tugging at Owen’s arm, she ran off.

“Go on,” Contessa said. “It’s worth seeing.” Owen thought there was something he should say, but his mind was blank. With a quick smile he ran after Cati. Contessa watched him go, her face kind but grave.

“Like your father before you, you will be tested,” she murmured. “Like your father.” With these words, sorrow seemed to fill her face. With a sigh, she turned back to the bustle of the kitchen.

When Owen emerged on to the corridor, he saw that Cati was almost lost in the crowds ahead. He dashed after her, but the flaps of leather coming loose on his trainers made it hard to run. Cati dived through another doorway and Owen, following, found himself on yet another twisting staircase rising upwards.

“Hurry up!” Cati shouted back to him. He was panting for breath when he emerged into daylight at the top. He stumbled on the top step and shot forward, landing flat on his face to find himself looking down the sheer wall of the Workhouse to the ground hundreds of metres below. A hand on his collar hauled Owen back. Cati was surprisingly strong and she practically lifted him to his feet before he pushed her hand away.

“I’m all right,” he said, trying to sound gruff. “Leave me alone. I can look after myself.” If she was offended by his tone, she didn’t show it. She met his eyes for a few seconds and he felt that he was being judged by an older and wiser mind, but he thought he saw sympathy there as well. “What is so important anyway?”

She pointed behind him. Owen realised that they were standing on a flat platform in the middle of the Workhouse roof. The slates on the roof were buckled and covered in mildew, and the stonework was weathered and cracked. In the middle of the platform was a large round hole.

“It’s a hole,” he said. “I can see that.”

“Listen,” she said. At first, he could hear a faint rumbling deep in the hole. Then there were deep groaning and complaining noises, as if some very old machinery was grumbling into life. There was a boom which sounded a long way away and then the rumbling got louder and Owen started to feel tremors in the ground beneath his feet. As the rumbling grew, the whole building seemed to shake and pieces of crumbling stone began to fall from the parapet.

“What is it?” He looked at Cati, but her attention was on the vast gaping hole in front of them. More loud groanings and creakings and protesting sounded from the hole, followed by a long, ominous shriek.

“Stand back!” Cati shouted above the noise.

Just as he did, a vast cloud of steam burst upwards and then, with terrifying speed, what looked like the top of a lighthouse shot from the hole – a lighthouse which seemed to be perched on top of a column of brass, which was battered and scarred and scratched and dulled as though it was ancient. Owen realised that the thing was coming out of the hole section by section, like a telescope, the sections sliding over each other with deafening groans and shudders and bangs, the whole structure swaying from side to side so that he thought it would fall on top of them. Cati gripped his arm.

“Jump!” she yelled, propelling him forward. The stained brass wall reared up dizzily in front of him and he saw himself rebounding off it, being flung over the parapet.

“Grab hold!” Cati shouted, just as Owen was about to hit the wall. Terrified, he glanced down and saw a brass rail coming towards him at great speed. He grabbed it with both hands and Cati pushed him over it, until he landed on his back on a narrow walkway as the platform shot upwards, swaying and groaning sickeningly.

After what seemed like an eternity, the platform heaved and clanged to a halt. Owen raised himself cautiously on one elbow and looked through the railing. It was a long way down. The figures on the ground below them were tiny. He turned and looked up. The little turreted point that resembled the top of a lighthouse was maybe twenty metres above him. Despite the battered look of the rest of the structure, the glass gleamed softly as if it had just been polished.

“What is it?” he said, his voice sounding a bit more shaky than he would have liked.

“This is the Nab,” Cati said.

“What’s that up there?”

“That? That’s the Skyward,” she said, almost dreamily.

“What’s it for?”

“For seeing, if it lets you. For seeing across time.”

“You could have killed us,” he said, “jumping like that.”

“Don’t be cross,” she said. “I knew you wouldn’t jump on your own.” Owen opened his mouth then closed it again. There didn’t seem to be anything to say. He looked around and saw that the platform they were on joined two sections of a winding staircase which led to the Skyward. He got to his feet, holding on to the rail. A sudden gust of wind caused the whole structure to sway gently. Owen took a firmer hold and looked out across the river.

Where Johnston’s yard had been there were trenches and tall figures in white, although the pale mist that came and went made it difficult to get a proper look at them. But there was no mistaking the defences that had been thrown up on his own side of the river. Earthworks topped with wooden pallisades. Deep trenches. And down near the river, hidden by trees, the flicker of that blue flame. Further in the distance he saw the sun touch the horizon, an orange ball, smouldering and ominous. It reminded Owen that he should be home and his eyes turned to the house on the ridge at the other side of the river.

He blinked and looked again, thinking that he was looking in the wrong place, but he knew from the shape of the mountains in the distance that he was not. He was looking for his house. The long, low house with the slate roof and the overgrown garden that his mother once kept. The house at the end of the narrow road with several other houses on it. No matter how much he blinked he could not see them. The road, the other houses, his own house where his sad mother wandered the rooms at night – they were all gone, and in their place a wood of large pine trees grew along the ridge. As if they had always grown there.

“It’s gone,” Owen said, his voice trembling. “The house is gone, my mother…”

He felt Cati’s arm around his shoulder.

“It’s not gone,” she said, “not the way you mean it. In fact, in a way it was never really there in the first place. Oh dear, that wasn’t really the right thing to say…”

That was enough. Tearing himself away from her, Owen started to run, clattering down the metal stairs of the Nab, out on to the roof and then down the stone stairs inside the Workhouse. He could hear Cati calling behind him, but he didn’t stop. Whatever was going on in this place, it was nothing to do with him. He was going to cross the river and get his mother. On he ran, through the busy main corridor now, elbowing people aside, shouting at them to get out of his way so that they turned to stare after him. The corridor cleared a little as he approached the kitchen, and he was running at full tilt, Cati’s cries far behind, when the sole of his right trainer came off and caught under his foot. Arms flailing, he tried to stay upright, but it was no good. With a ripping sound, the sole of the left trainer came off and Owen went crashing to the ground, his head striking the stone floor with a crunch.

He lay there for a moment, sick and dizzy. He put his hand to his head, feeling a large bump starting to rise. He opened his eyes and saw a pair of elegant slippers. He looked up to see Contessa peering down at him with concern. Cati skidded to a halt beside them.

“I didn’t tell him… I mean, I said it would be explained…” she stammered. Contessa held up a hand and Cati stopped talking. Owen sat up and Contessa knelt beside him.

“Our house,” he said hopelessly, “my mother, they’re gone…”

“I know,” Contessa said gently. “I know. Here. Drink some of this.” She pulled a small bottle from under her robes and put it to his lips. The liquid tasted warm and nutty.

“I have to go,” he said. “She might be frightened…” But as he spoke, everything seemed to become very far away, even his own voice. His eyelids felt heavier and heavier. He had to fight it. He had to go home. But it seemed that his brain refused to send the order to his legs to move. Instead, strong arms enveloped him and lifted him, and as they did so, he fell asleep.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_68c106c3-0068-5dcb-8688-4fb7078af867)

Owen felt himself coming out of sleep as though he was swimming to the surface of a warm sea. He opened his eyes. It was dark, but it was a strangely familiar dark. Then he realised – he was in his Den. It all came flooding back to him – the Workhouse, Cati. Perhaps he had been asleep and dreamed the whole thing! He felt along the back wall for the store of candles he kept there and lit one. He pulled the sleeping bag around him and sat very still. That was it, he decided. It had all been a very real dream. He felt cold and he moved to pull his sleeve down over his forearm. As he did so, the seam disintegrated and the sleeve came away in his hand. He looked down on the floor and saw his trainers, both soles half torn away. It hadn’t been a dream! He remembered sitting on the chest in his bedroom that morning and longing for something strange and exotic. Well, what had happened was certainly strange, but he wasn’t so sure if he wanted it as much.

He tried to arrange what he knew in his head. The Sub-Commandant. Cati and Contessa. The Workhouse and the Nab. But it was no good. He couldn’t make any sense of it. Owen jumped to his feet, and as he did so, he felt his clothes falling away. He looked down. His trousers were hanging in rags; his jacket and T-shirt seemed to have disintegrated.

Owen looked round the walls of the Den. The posters he had hung on the wall had faded, the images indistinct and the paper yellowed. The metal objects did not seem to have suffered as badly, although he noticed that the plastic on the cassette player had faded and warped. Only the brass boat propeller he had found in Johnston’s yard seemed to be the same as ever. He tugged at the rotting fabric of his T-shirt in disgust. He couldn’t go out without clothes. Then he noticed a neat pile of clothes in the doorway. Owen unfolded it. It seemed to be a uniform of the same faded fabric as the Sub-Commandant had been wearing. There was a pair of boots made of some material which seemed like leather but was not, and which fastened to the knee with brass clips. He imagined what would happen if any of the town children saw him in those clothes – how they would laugh – but a sudden draught on his bare skin made him shiver. He realised that he had no choice but to put on the clothes.

Five minutes later, Owen looked at himself in the mirror. He seemed to look much older. The uniform was a good fit, although it was frayed here and there. He thought he looked like a soldier, somebody who had been in a long war far from home. He heard a noise behind him and he turned. Cati was standing in the doorway.

“It suits you,” she said.

“This is my place. You have no right to come in here without asking,” said Owen, suddenly defensive.

“I was only trying to help. You needed clothes.”

“I don’t need anything of yours!” he said angrily. “I just want to be left alone.”

“Next time I will leave you alone,” she snapped back. There were red spots high on her cheeks. “Next time I will leave you alone and you can go around in your bare skin.”

They glared at each other for a minute. Then Owen saw a muscle twitch in Cati’s face. He felt his own face begin to crease. A few seconds later they were helpless with laughter.

Owen laughed until his sides ached. He and Cati collapsed on the old bus seat, wiping their eyes. They sat for a moment in companionable silence, then Cati leapt to her feet without a word and went back outside. When she came back, she was carrying a basket. Delicious smells rose from it and Owen realised that he was ravenous.

“Contessa sent it,” Cati said. She opened the basket and set out the contents neatly on the top of the dressing table. There was fresh, warm bread and sealed bowls of hot stew. There were roast potatoes, cheese sauce and all sorts of pickles which Owen didn’t think that he would like and then discovered he did. They ate without talking, finishing up with two bowls of a delicious substance which was something like custard and something like cream. Owen lay back on the bus seat feeling that suddenly life did not look so bleak after all. But Cati leapt to her feet again.

“Come on,” she said briskly. “We have to go to the Convoke.”

“I’m too full for a Convoke now, whatever it is.”

“I think you’d better come,” Cati said, suddenly serious.

“You need to know about your mother, apart from anything else.”

His mother! Owen sprang to his feet and hurried after her. Outside, it was a cold, crisp night and he could see his breath hanging in the air. He hurried after Cati through the shadows of the trees.

“We’ve got time,” she said. “There are two parts to this Convoke… and you’re not allowed into the first part.”

“Why not?”

She hesitated then spoke softly as if she was afraid that she might be overheard. “Well… it’s actually about you.”

“About me?”

“Yes. It’s about whether you should be allowed to attend or not. And other things.”

“Why wouldn’t I be allowed to attend?”

“You’ll find out.”

Owen was puzzled. What was so special about him that they would waste time talking about whether or not he could attend the Convoke?

“Do you really want to hear the first bit?” Cati asked. “Really?”

“I suppose,” he said. “if it’s about me, maybe I’d better.”

“There’s a secret way into the chamber,” she said. “I found it ages ago. Come on.”

Cati turned on to a path which seemed to lead under the hill. Owen had noticed a gully there before, but it had been choked with trees and undergrowth. Now it had been cleared and the path was smooth underfoot. The path sloped downwards and high walls reared on either side, their ancient stones covered in moss and ferns and lichen.

“Where are we going?” Owen said, realising he was whispering.

“You’ll see.”

Cati moved swiftly on. It became darker and darker, but she did not falter and Owen began to wonder if she could see in the dark.

After what felt like a long time, Cati stopped so suddenly that Owen ran into her. As his eyes became accustomed to the dark, he saw that they were standing in front of a vast door made of brass and wood, so old and gnarled that it looked like stone. Again, it was decorated with spidery shapes that looked like a child’s drawings of boats and planes. As Owen examined it, he realised that the drawings glowed faintly with a blue light he had seen everywhere that day.

Cati took a key from her pocket, a tiny key for a door so vast, but as she held it up he could see that it was ornately worked with complicated-looking teeth. She fitted it into a tiny aperture and turned it, once, twice, three times. There was a sound like heavy, oiled bolts being drawn and then the huge door swung silently open. Cati stepped inside and Owen followed. As they did so, the door closed soundlessly behind them. They were now standing in a narrow passage lit by faint blue light coming from the opening at one end. There was an odd smell, musty and old, but sweet as well.

Cati slowly stepped through the opening. Owen hesitated, then with a backwards glance at the closed door, stepped forward also.

He found himself in a vast chamber, stretching off as far as the eye could see. The ceiling, high above them, was speckled with points of blue light so that it seemed that they stood under a clear night sky. But that was not all. The chamber was filled with innumerable flat couches, each with a single sheet and a pillow. Most of the beds were empty, but as Owen’s eyes got used to the dim light, he saw that some of them were still occupied. He looked for Cati, but realised that while he had been standing lost in awe she had moved quietly off. He watched as she moved slowly among the occupied beds which were scattered among the empty ones. The sleepers seemed to be of all ages, young and old, fair and dark. She stopped by one bed as Owen went towards her. He saw that the figure in the bed was a young man, a little older than him. He had curly dark hair and his breathing was deep and even. Cati reached out and touched his hair, smiling sadly.

“What is this place?” Owen asked.

“The Starry, where we sleep until we are called.”

“Who are these people then?”

“Friends, most of them. When we get the call we are supposed to wake, but some do not wake and we do not know why.”

Owen saw that the black-haired boy and two other children – girls with brown hair – were lying in a circle round a woman with work-worn hands and a pleasant face that seemed to be smiling even as she slept. Cati put her hand on the woman’s shoulder and bent to kiss her. Owen wanted to ask who she was, but Cati seemed to be almost in a dream and he didn’t want to disturb her. He noticed that each pillow had a small blue cornflower placed on it.

“It is our sign of remembering,” Cati said. “A sign that we do not forget our friends.”

The sweet, musty smell in the air seemed to be getting heavier. If sleep had a smell, this is what it would smell like, Owen thought to himself. His eyelids felt as if there were weights attached to them. The empty beds began to look very inviting.

Suddenly, he felt Cati shaking his shoulders. “The Convoke,” she said urgently. “Come on. If you stay here, you’ll sleep.”

She led him towards a small doorway which opened on to another one of the winding staircases that were a feature of the Workhouse. The staircase was dark and apparently unused; cobwebs brushed their faces as they climbed, but there must have been a window to the outside world for Owen felt cold fresh air on his face, chasing away the sleep that had stolen over him in the Starry.

“What is the Starry for?” he said. “Why are they all sleeping? They look as if they’ve been asleep for years.”

“They have,” said Cati, sounding sad, “but that’s another thing that needs to be explained.” And she would say no more about it.

At the top of the staircase was another corridor, then another staircase, then they were under the Workhouse roof. Owen ducked his head to avoid the huge timber beams supporting the roof, half choking on the dust which rose in great clouds under his feet. Just as he was about to ask where they were, Cati turned and put her fingers to her lips. Following her, he got on to his hands and knees and crawled forward. He saw light coming through a gap in the stone wall in front of him. Cati disappeared into the light and he followed to find himself in a tiny wooden gallery suspended, it seemed, in mid air over great buttresses which went down and down until they reached the floor far below. Owen gasped and grabbed Cati’s arm. She made a face at him to be quiet and pointed. Far below them, the Convoke had started.

It was a while before Owen’s eyes adjusted to the light and he could make out the scene below. The first thing he noticed were the banners which hung from the ceiling, enormous cloth banners in faded colours which seemed hundreds of metres long. Then he saw that the banners framed a great hall of flagged floors and pillars and stone walls. Massive chains hanging from the roof held globes of blue light and in its glow he could see figures on the ground, some standing, others sitting on a raised dais, and many more standing in a circle around them. He could see that one of the standing figures was the Sub-Commandant and even from far above Owen could tell that the small man was pleading with the figures on the dais.

To the right of these figures was a fireplace where great logs burned, and in front of the fireplace a figure sprawled in a chair. It was too far away to see who it was and Owen was distracted just then as the Sub-Commandant began to speak. His voice was low and even, but there was an intensity to it and Owen guessed that there was some dispute going on.

“You are talking about history in this, Chancellor, but we aren’t certain about what took place,” he said. Owen could just see Chancellor shake his head as if in sorrow.

“I think that you are the only one who doubts what happened, Sub-Commandant,” Chancellor said. “We had the Mortmain and with it the security of the world, or at least as much as was in our power to guarantee. But the Mortmain is gone.” His voice was mellow, but full of authority, a leader gently rebuking a much-loved but erring lieutenant. Even from his perch in the rooftop, Owen could feel that the crowd in the hall was swayed by him.

“We cannot judge the future by the past,” the small man said. “There are many things that we don’t know.”

“I agree that there are many things we do not know,” Chancellor said, “but we have to work with what small knowledge we have. I feel that the boy should not be admitted to our counsel.”

The crowd began to murmur this time. Glancing sideways, Owen could see that Cati looked worried. Chancellor leaned back in his chair. He did not look triumphant, but weighed down by the gravity of the situation. Suddenly, Owen heard a woman’s voice – a ringing voice with a tone of harsh amusement to it.

“The boy should be allowed in,” the voice said.

“You have been listening to our arguments, Pieta?” Chancellor asked. The woman made a scornful sound.

“I have no need to listen to your talk, Chancellor,” she said. “I know what is right and so does the man who has watched for us these long years. The boy is allowed into the Convoke by right of who he is.” Owen realised that the voice was coming from the chair by the fire.

“Would we leave him outside, parentless and confused?” the Sub-Commandant said softly.

“Is that your final position, Pieta?” Chancellor asked. His voice was low and there was a hint of anger in it. There was no reply from the chair, but Owen heard a bottle clinking against a glass and there seemed to be a kind of finality to the sound.

Chancellor sighed. “You have the right to ask much for your defence of us…”

“Yes. I have the right, Chancellor.”

“I appreciate your reservations, Chancellor,” Contessa interjected gently, “but I think justice demands that the boy be brought before us.”

“You appeal to justice, Contessa, but are you certain that the boy does not appeal to another part of you?” This new speaker stood up. He was a long-haired man dressed in a uniform of sombre but rich red. As he spoke, he swept his hair back over his shoulder. A silence fell over the hall. Contessa did not reply, but Owen could feel a chill stealing over the hall.

“That settles it,” the woman they called Pieta said. “Bring the damn boy and bring him now. If our resident peacock starts scheming about the thing, we’ll never hear the end of it.” The man in the coloured uniform glared at Pieta and made to speak again, but Chancellor held up his hand.

“Sub-Commandant.” His tone was commanding.

“I sent Cati to get him,” the Sub-Commandant said. “In case he was required,” he added smoothly. Chancellor turned his gaze to the Sub-Commandant. Owen shivered. He could only imagine the scrutiny of those piercing eyes.

“While we are waiting,” Contessa said, “we should discuss those who will not wake. The numbers have risen. We’re desperately weak, Chancellor.” Owen realised that she must have interrupted in order to break Chancellor’s searching gaze at the Sub-Commandant. He felt Cati’s elbow dig him in the side.

“Come on,” she hissed. “Quick!”

Owen and Cati crawled back through the gap in the stone wall. They ran as fast as they could down the staircases, Owen’s clothes covered in cobwebs and hands and elbows grazed from the rough stone walls as he tried to keep his balance. They practically fell out of the stairway into a brightly lit hall, dishevelled and filthy. A young man in the same richly coloured uniform as the long-haired man grabbed Owen under the arm and lifted him to his feet. His face seemed friendly but serious.

“Hurry,” he hissed. “You do not keep the Convoke waiting.”

The wooden door in front of them swung open and Owen was propelled into the hall.

Owen stopped dead. Every eye in the hall was fixed on him. He could see Chancellor standing on the dais. The young man gestured to him impatiently. Somehow, Owen managed to put one foot in front of the other, the crowd parting in for him as he did so. He felt his heart beat faster and faster, and as he approached the dais, his foot caught the hem of a woman’s cloak. He would have fallen had not a hand reached out and grabbed his elbow. Owen turned and found himself looking into the eyes of a tall older man with a beard and a terrible scar which looked like a burn on one side of his face. The man grinned and winked at him, managing to look both villainous and friendly at the same time. The sight gave Owen heart. At least he wasn’t without friends in the hall. He pulled himself upright and strode to the dais where the Sub-Commandant addressed him.

“You are welcome to the Convoke, young Owen. Have you anything to ask us?” But before Owen could open his mouth the man with the long hair broke in.

“He’ll have time enough for questions. For the moment I want to ask him a few things about himself and how he got here.”

For the next ten minutes Owen found himself answering questions about where he came from, his school, his friends, his age and how well he knew the area around the Workhouse. Such was the piercing quality of the man’s eyes and his air of command that it was impossible not to reply.

Chancellor was particularly interested in Johnston’s scrapyard. Contessa asked him about his home and about his mother, and listened sympathetically as he tried to make things with his mother sound better than they actually were, while feeling that he was letting her down with every word.

“Do you have any great fears, things that terrify you for no apparent reason?” Chancellor asked. His voice was casual, but Owen could feel that the whole Convoke was intent upon the answer. In his mind the image of a deep, still pool of black water formed, and he saw himself bending over it and realising that there was no reflection. He felt a single bead of sweat run down his spine and his voice dropped to a whisper.

“N-no,” he stammered. Before he had time to wonder why he had lied, the man in the red uniform stood up.

“I’ve had enough of this. Where is the Mortmain? Tell us that, boy. Return it to its rightful owners!”

“Enough, Samual!” the Sub-Commandant said. He didn’t speak loudly, but his voice cut through the tension in the room like a whiplash. The man in red sat down again, grumbling.

“That subject should not have been mentioned,” the Sub-Commandant went on. “Let the boy ask his questions now.”

Owen looked around. A thousand questions swirled in his mind. “Where am I?” he said and then, with his voice getting stronger, “Who are you? And what has happened to… to everything?”

“I will try to answer,” Chancellor said, getting to his feet. “There are three parts to your question. As to where you are, you are in the Workhouse, the centre of the Resisters to the Harsh and the frost of eternal solitude that they wish to loose upon the earth. We are not the only Resisters. There are pockets elsewhere, perhaps even in other lands, but all hinges on us, on our strength and strategy.” There was pride in his voice, even vanity, but sorrow as well.

“As to who we are,” he went on, “we are the Wakeful. We sleep the centuries through until we are called. You could say we are the custodians of time. Like everything else, time has a fabric or structure. And sometimes that fabric is weakened or attacked and requires repair or defence. But we do not have much time to explain things, and others can tell you more of us. The most important of your questions is the last. What has happened?”

“I will answer that,” the Sub-Commandant said, “since the boy and I both witnessed it, although he did not know it at the time.”

“The floor is yours,” Chancellor said stiffly.

Once more Owen could feel the people in the hall bend their attention to the slender figure, as if he was going to relate a terrible story that they had heard before but felt compelled to hear again.

“You may perhaps have learned that time is not a constant, that it is relative.” Owen nodded, hoping that he looked clever. The words that the Sub-Commandant used were familiar from school, but to tell the truth he hadn’t been listening when these things were talked about, and he hadn’t understood what he had heard.

“What happened today is an extension of that. Do you remember when you saw that dark flash in the sky?” Owen nodded. “The process is complex and subtle, and many events took place both together and apart. But to put it in the simplest possible terms, a terrible thing has happened. A thing that our enemies have sought to achieve for many eras.”

The Sub-Commandant paused. The whole hall seemed to hold its breath and Owen realised that although they knew in their hearts what had happened, it had yet to be confirmed to them. The Sub-Commandant’s face was stern and grey and age showed in it, great age.

“They have started the Puissance,” he said. “the Great Machine in the North turns again and time is flowing backwards.”

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_877e7191-699f-5bdb-a429-f541e12a25eb)

A shuddering sigh flowed through the hall. Owen stared blankly at the Sub-Commandant. How could time flow backwards? What sort of machine were they talking about? He didn’t know how long he stood there until the Sub-Commandant stepped forward and gripped him by the shoulders.

“It’s a lot for you to understand and I won’t trouble you with any more tonight. You’ll have questions and we’ll answer them as best we can. But for now, I think it is best if you rest.”

“Wait!” The man they called Samual rose to his feet. “I have a few more questions.” He moved up close to Owen and walked round him, studying him, his eyes glittering with dislike. “What is your understanding of your father’s death?” he barked.

Owen froze. It was something he tried not to think about. “There was an accident…” he stammered.

“Suicide,” Samual said. “Wasn’t that it?”

“No…” said Owen.

“Is there a point to all of this?” Contessa asked, her voice cold. She obviously didn’t approve of Samual’s questioning, but he ignored her.

“Have you ever heard of Gobillard et Fils?” he demanded sharply, his face almost pressed against Owen’s now, his eyes eager.

Gobillard et Fils, Owen thought. That’s what was written on the trunk in his bedroom! How did this man know about that? He could feel Chancellor and the others watching him intently.

“No…” he stammered, “no… I’ve never heard that name before…” The lie was out before Owen knew what he was saying. Why had he not admitted that he’d heard the name before? The blood rushed to his face. Would someone notice?

He was saved by the Sub-Commmandant. “The boy is not a prisoner to be interrogated, Samual. That is enough.”

Samual looked for a moment as if he would defy the Sub-Commandant, then he thought better of it and turned away.

“You may go, Owen,” the Sub-Commandant said gently.

Owen’s mouth was dry and his head was spinning, but he knew that there was one question he must ask before he was made to leave the hall. He turned towards the Sub-Commandant and his voice was no more than a whisper.

“Please,” he said, “what has happened to all the people?” There was a long silence then Contessa spoke.

“You are thinking about your mother, of course. I will explain it as we understand it. In turning back time, the Harsh intend to go back to a time before people. The minute they started the reversal, the people disappeared as if they had never been. So nothing has happened to them, but they have never been. Except for us, stranded on an island in time – as you now are.”

“If we stop the Harsh you’ll get your mother back!” It was Cati’s voice. She had somehow evaded the watchers on the door. “You’ll get her back and it’ll all be the same again!”

Contessa gave Cati a stern look, but Owen thought he could see the ghost of a smile hovering around her lips. “That is true. We have stopped them before.”

“But this time is different,” Chancellor said. “The Harsh are stronger than ever and we are weaker. I cannot see how we can overcome them.”

“We are the Resisters,” the Sub-Commandant said softly, “and it is our duty to resist, come what may.”

Chancellor looked as if he was about to say something more, but in the end he only shook his head and sighed.

“Cati,” Contessa said, “you should not be here, but as you are I would like you to take Owen out of the Convoke. We have many other issues to discuss.”

Cati took Owen gently by the arm and the crowd parted again for them as they walked towards the door. Owen wanted to ask more questions. What was the Starry? And what had the Mortmain – whatever it was – to do with him? And why were the Resisters so interested in him anyway?

Owen glanced towards the armchair beside the fire. To his surprise, the owner of that harsh voice was much younger than she sounded. Pieta was slim with blonde hair and a girlish face. She was asleep, snoring gently, and wearing a faded uniform similar to his own, but attached to her belt was an object unlike anything he had ever seen before. It looked like a long, coiled whip, but this whip was made of light – a blue light shot through with pulses of energy so that it seemed a living thing. Beside the woman was an empty bottle and a glass. As Owen stared, she opened one eye and looked directly at him. Her eye was bloodshot and bleary, but Owen felt instantly that she knew everything there was to know about him.

Pieta’s lips curved in a brief smile, weary and sarcastic, then her eyes closed again and Owen felt Cati haul him towards the door, which opened for them as they reached it and closed gently but firmly behind them.

Owen felt numb. He had never thought about time before, or the fact that it might possible for it to go backwards. “What did Contessa mean by an island in time?”

“That’s where the Workhouse is – on an island in time,” Cati said. “Time is like a river flowing around us, but the Workhouse never really changes. And we don’t change either.”

“You mean you don’t get older or anything?”

“’Course we get older,” Cati said with a heavy sigh, as though she was explaining to an idiot. “It’s just that we grow old at the same rate as normal people, no matter what time does. You look like you need air.”

“I need…” Owen began. But what did he need? A way to understand all of this? Sleep to still his racing mind? A place to hide until it all went away and things returned to as they were before? He was tired, his eyes felt grainy and his limbs fatigued, but an idea was beginning to take shape.

Outside, a mild, damp wind was blowing drizzle in from the direction of the town and you could smell the sea on it.

“Do you want to talk?” Cati sounded anxious.

“No,” he said. “No thanks, I’m really tired. I need to sleep, I think.”

“You can sleep here. Contessa will find you a bed.”

“No!” said Owen, more sharply that he intended. “I want to go back to the Den.”

“I understand,” she said. “I’ll walk there with you.”

“I want to be on my own,” he said stiffly.

Cati watched as Owen turned abruptly away and walked towards the path to the Den. He felt bad. He didn’t want to offend her, but there was something he had to do. As soon as he had rounded the first corner in the path, he dived off it into the trees.

Owen climbed steadily for ten minutes. He knew the landscape well, but it was dark and the rain made it murky, and there seemed to be trees where no tree had grown before. By the time he reached the swing tree, his hands were scratched from brambles and there was a welt on his cheek where a branch had whipped across it. He got down on his belly and crawled to the edge of the drop. He looked across the river, but it was shrouded in gloom. Down below, could just make out what seemed to be trenches and defensive positions which had been dug the whole length of the river.

As Owen looked closer, he saw that they were hastily dug in parts and in other places there were none. He studied the defensive line and saw that it was at its weakest under the shadow of the trees, in the very place where he had crossed that morning. Silently, Owen slipped over the edge and began to slither down the slope, any noise that he made smothered by the insistent drizzle.

At the bottom of the slope he made his way quietly through the trees. Almost too late Owen realised that there was now a path running along the edge of the river. He shot out of the trees into the middle of the path and as he did so he heard a man clearing his throat. Quickly, he dived into the grass at the verge and held his breath. Two men rounded the corner. Both were bearded and carrying the same strange weapon as the Sub-Commandant. They looked alert, nervous even, and their eyes kept straying to the river side of the path – which was just as well, as Owen was barely hidden by the sparse grass at the edge of the trees. They walked past him as he held his breath and pressed his face into the wet foliage. Within seconds, they had rounded the next corner and were gone.

Owen stood up, shaking. He took a deep breath. He had avoided the patrol through luck and he realised that it might not be long before another one came along. He darted to the other side of the path and plunged through the undergrowth towards the river.

It was dark on the riverbank; only the sound of the water told him where it was. He felt his way along the bank until he found the old tree trunk that he had climbed across that morning. Suddenly, he felt sick and dizzy at the thought of crossing the black water. He grabbed the tree trunk firmly. If he didn’t start across now, his courage would fail him completely.

Breathing hard, Owen swung himself on to the log. It was wet and slick to the touch. Inching forward, he glanced down and saw the water glinting beneath. He shut his eyes and moved again. The sound of the water grew louder and louder. He opened his eyes. With a start, he realised that he was halfway across.

Owen fixed his eyes on the far bank. He had started on his hands and knees, but now he found himself on his belly, slithering along the wet trunk. It was when he was three quarters of the way across that he felt it – a slight flexing of the tree trunk, barely noticeable, as if there were now some extra weight bowing the wood. He risked a glance back over his shoulder. There was something on the trunk behind him; something small and fast-moving. Panting, Owen tried to move faster, scrambling for grip. He looked behind again. It was halfway across now and gaining fast. He gulped for air and it sounded like a sob. Then he got to his feet and tried to jump the last couple of metres. Just as he jumped, Owen was hit hard and fast from behind. He felt himself gripped and turned in the air, and as he hit the muddy bank with an impact which drove the air from his lungs, a small powerful hand grabbed him first by the hair, then covered his mouth and his nose so that he couldn’t draw the shuddering breath that his aching lungs needed.

“Stupid boy!” Cati hissed furiously. “Where do you think you’re going?”

It was several minutes before Owen could get enough air to enable him to talk. Cati crouched beside him, staring intently into the dark.

“We have to get away from here,” she whispered urgently.

“I’m not going back,” he said. “I’m going home.”

“It’s not there any more! You’ll be caught or killed looking for something that’s gone. Listen to me.”

“That’s the problem,” said Owen. “I’ve been listening to everyone about time turning back and people sleeping for years and great engines and people disappearing. But I have to see. I have to see that my house is gone. I have to see that… that…” He gulped and turned his head away, hoping that she wouldn’t see the tears in his eyes. Stumbling to his feet, he wiped his eyes with the sleeve of his jacket.

“I have to see,” he repeated.

Cati gave him a long, level look, then seemed to come to a decision. “All right, but I better come with you.”

“You can’t,” he said. “I’m going on my own.”

“Don’t be silly. You made enough noise going through the trees to wake the whole Starry, and you left a trail a blind man could see. If I come with you, at least we have a chance of getting back. Not much of a chance, mind you.” Cati seemed almost cheerful about the prospect.

“Come on then,” she said. “Might as well get it over with.” And set off at a crouch, moving fast and silent. Owen had no choice but to follow her along the riverbank.

A few minutes later he thought he had lost her, then almost tripped over her. Cati was squatting on the ground.

“Careful,” she hissed. “Get down here.” She had a twig in her hand. “Look.”

Owen squinted in the darkness. He could just about see the two parallel lines she had drawn in the earth.

“This line is the river,” she said, “and this one is the Harsh. We’re in between, here. And the place where your house used to be is here, just in front of their lines. We can get to it, if we’re really quiet and really lucky. But you have to do what I tell you, all right?”

Owen nodded dumbly. He hadn’t really thought through what he had set out to do, and now he was feeling foolish and headstrong. Cati had called him a stupid boy and he was starting to feel like one.

“Let’s go!” Cati said. He followed her, moving slowly now. They turned left and started to climb the hill towards the Harsh lines. There was more cover than he had expected. Where once there had been open fields there were now deep thickets of spruce and copses of oak and ash trees. Progress was slow. Cati whispered that there might be patrols about, and more than once she glared at him as he stood on a dry twig or tripped over a low branch. He did not recognise anything in the place where he had once known every tree and ditch, although sometimes he stumbled over something that might have been the crumbling foundation of an old field wall.

After what seemed like hours, Cati turned to him and held her finger to her lips. They stepped into a clearing – a patch of low scrub. With a start, Owen looked around him. There was no real way of telling, but his heart said there could be no doubt; he was standing in the place where his house had been.

Was that flat piece of ground with saplings growing in it the place where the road had been? And was that young sycamore the same gnarled tree that had stood outside his bedroom window? Owen moved forward carefully until his foot struck something. Pushing back the vegetation he found the remains of a wall. He moved along the wall until he reached a corner and then another corner. It was the right size and shape as his own house. In fact, he was standing underneath the window to his own room, if it had been there. The room with the model hanging from the ceiling, and the guitar, and the battered trunk he had stood on to climb out of the window.

“I don’t understand,” he whispered. “If time is going backwards, how come the sycamore tree is getting younger, but the house is getting older? Surely the house would turn back into bricks and stuff.”

“Living things get younger as time goes backwards,” Cati said, “but things built by man just decay. It has always been like that.”

Owen began to notice that the grass and weeds were criss-crossed with scorch marks, and that the leaves of low-hanging trees were blackened and dead. Cati reached up and broke off a leaf which crumbled in her hand.

“The Harsh have been here,” she whispered fearfully, “searching for something by the look of it. We have to go.”

But Owen wasn’t ready. He moved his foot and something clanked against it. He put his hand down into the undergrowth and groped around until his hand closed on an object. He held it up. It was the hand mirror that his mother used when she brushed her hair. The brass back was tarnished and the glass was spotted and milky in places, but it was the same mirror, and as he looked at it, he could picture his mother brushing her hair, her lips pursed, whistling tunelessly to herself. The glass was becoming yet more faded, until he realised that his eyes had misted over.

Cati said something, but he didn’t hear her. And he was only barely aware of the cold that started to steal over him. It wasn’t until he heard a faint crackling that Owen glanced up at a small twig which hung in front of him. As he looked, it seemed that hoar frost crept up the leaf from the tip, then to another leaf and then another, until the stem itself froze and cracked with a gentle snapping sound as the sap expanded.

Owen looked around. The crackling sound was caused by dozens of leaves and twigs snapping in the same way. He turned to Cati, but she was staring off into the trees and her face was a mask of fear. He followed her terrified gaze. Far off, but moving inexorably closer, were two figures, both white, both faceless, and seeming to glide without effort between the trees. Cati’s voice when it came was no more than a whimper.

“The Harsh,” she said. “They’re here.”

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_9128c20b-16d3-5086-b74b-2ac6f9442f5c)

The cold seared Owens lungs. Somehow he knew that the Harsh were talking to each other in mournful voices full of desolate words that were just out of earshot. The pitch of the voices rose to make a noise like the howling of wolves being carried away on an icy wind and Owen wondered if they had been spotted.

“Come on,” he said to Cati in an urgent whisper. “Run!” But it was no good. She seemed to be paralysed with terror. “Please, Cati,” he said. “I think they’ve seen us.”

“No,” she moaned, “they don’t see well. They can smell us though. They can smell the warmth.”

Owen grabbed Cati by the arm and hauled her to her feet. She stumbled after him. The Harsh were moving sideways, slipping through the trees. They were going to cut Owen and Cati off from the river. Cati wasn’t resisting him, but she wasn’t helping either. Owen thought he could hear the voices again and he felt a chilly dread steal over him, a sense that things were lost and that there was no point in running. He realised that this must come from the Harsh and was why Cati was paralysed with terror.