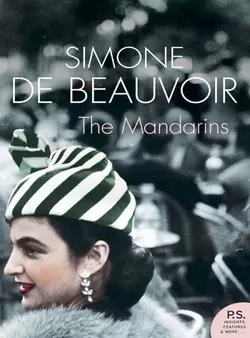

The Mandarins

Simone de Beauvoir

A Harper Perennial Modern Classics reissue of this unflinching examination of post-war French intellectual life, and an amazing chronicle of love, philosophy and politics from one of the most important thinkers of the twentieth century.An epic romance, a philosophical argument and an honest and searing portrayal of what it means to be a woman, this is Simone de Beauvoir’s most famous and profound novel. De Beauvoir sketches the volatile intellectual and political climate of post-war France with amazing deftness and insight, peopling her story with fictionalisations of the most important figures of the era, such as Camus, Sartre and Nelson Algren. Her novel examines the painful split between public and private life that characterised the female experience in the mid-20th century, and addresses the most difficult questions of gender and choice.It is an astonishing work of intellectual athleticism, yet also a moving romance, a love story of passion and depth. Long out of print, this masterpiece is now reissued as part of the Harper Perennial Modern Classics series so that a whole new generation can discover de Beauvoir’s magic.

SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR

The Mandarins

Translated by Leonard M. Friedman

With an introduction by Doris Lessing

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_c00472be-881c-5b9c-b541-b999973a39ac)

Harper Perennial

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This Harper Perennial Modern Classics edition published in 2005

Harper Perennial

Previously published in paperback by Flamingo 1993 (as a Flamingo Modern Classic) and 1984 (reprinted five times)

First published in France in 1954 by Librairie Gallimard

under the title Les Mandarins First English translation published in Great Britain by Collins 1957

Copyright © Librairie Gallimard 1954

English translation copyright © Collins 1957

Introduction copyright © Doris Lessing 1993

PS section copyright © Jon Butler 2005 except ‘Equals Not Sequels’ by Kathy Lette

© Kathy Lette 2005

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © MAY 2018 ISBN 9780007405589

Version: 2018-05-16

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

DEDICATION (#ulink_0d45eb04-4a45-50f8-b264-7b43fb8718e3)

To Nelson Algren

CONTENTS

Title Page (#u578df9aa-6ba0-59ab-bf02-c73e47f4beba)

Copyright (#u67e63b26-7b4c-53ec-9fdb-044f73b77583)

Dedication (#u3751c132-a7fc-5c83-b573-7cdacb3e1c87)

Introduction (#u56dd54ee-419e-5570-8f94-5178678da272)

Chapter One (#u5d1ec673-ba53-5a3f-9002-36333c2640d0)

Chapter Two (#ub801d923-2208-5154-9ddb-cb41a0dd8206)

Chapter Three (#u324cca4b-2d05-53e5-a2d7-dfa287856128)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

P. S. Ideas, Interviews & Features … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Biography (#litres_trial_promo)

Did You Know? (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Equals Not Sequels (#litres_trial_promo)

After the War: The Intellectual ‘Mandarins’ of Paris Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

If You Liked This, You Might Like … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_5774fb07-7c92-5c3c-9ff1-f8428a0a689f)

by Doris Lessing

Even before The Mandarins arrived in this country it was being discussed with the lubricious excitement used for fashionable gossip. Everyone knew the novel was about the political and sexual lives of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and their friends, a glamorous group for several reasons. First, they were associated with the French Resistance, and of all the heroic myths of the Second World War the Resistance was the most potent. Then, they were French, and it is hard now to explain the degree of attractiveness France had for the British after the war. It was only partly that we knew our cooking and our clothes to be inferior, that they had a style and panache we lacked. The British had been locked up in their island for the long years of the war, could not refresh themselves outside it, and France wore the features of some forbidden Paradise. And, too, intellectual communism, intellectuals generally, were glamorous in a way they never have been here, not least because what The Mandarins were debating along the Left Bank were questions about the Soviet Union scarcely acknowledged in socialist circles here, or, if so, only in lowered voices. There was another reason why The Mandarins was expected to read like a primer to better living, and that was the relationship between Sartre and de Beauvoir, presented by them, or at least by Sartre, as exemplary. It was close and matey, like a marriage, but without the legalities and obligations of one, while both partners had absolute freedom to pursue sexual adventures they fancied. This arrangement, needless to say, appealed particularly to men, and innumerable sceptical women were lectured by actual or possible mates on how they should take a lesson from Simone, a woman above the petty jealousies that disfigure our sex. As it turned out, women were right to be sceptical, but there was for us too an attraction in that comradely relationship over there in Les Deux Magots and the Flore, where Jean-Paul and his long-term woman Simone together with all his petites amies, where Simone and her steady, Jean-Paul, and her other little loves, male and female, all forgathered daily to partake of lofty intellectual fare, watched by hundreds of reverential disciples. But it turned out there was nothing of this ideal relationship in the novel, and the Simone figure, Anne, was presented as a dry and lonely woman, in a companionable marriage, resigned to early middle age.

Sartre then stood for an adventurous optimism about science. There was a film about him, showing him stepping out of a helicopter, then the newest of our toys, hailing the brave new world of technology, the key to unlimited progress. We needed this kind of re-evaluation, after watching for the years of the war how war used our inventions and discoveries for destruction.

And then, there was Existentialism. Just as most communists had never read more of Marx than The Communist Manifesto, most people attracted by Existentialism had read Sartre’s plays and novels. Thus diluted, it was agreeable latter-day stoicism that steadily confronted the terrors of the Universe while refusing the weakminded consolations of religion; courageous, solitary, clear-minded.

The Left Bank was, quite simply, the intellectual centre of the world, no less, and here was The Mandarins, a guide to it written by one of its most glittering citizens.

But Paris was only the half of it. Simone de Beauvoir had had a much publicized affair with Nelson Algren, and the novel describes it. Algren, then, was famous for The Man with the Golden Arm, and A Walk on the Wild Side, cult novels romanticizing the drug and crime cultures of big American cities. Drugs, crime and poverty were as glamorous as, earlier, had been La Vie Bohème with its TB, its drunkenness, the misery of poverty. The bourgeoisie have always loved squalor – in fiction. (In those days the words bourgeoisie, bourgeois, petit-bourgeois tripped off all our tongues a dozen times a day, but now it is hard to use them without being overcome by staleness, by boredom.) To be bourgeois was bad, middle-class values so disgusting that people dying of drugs, or in prison for selling drugs, or with lives wasted by poverty were in every way preferable, full of poetry and adventure that cocked a snook at capitalism and the middle class. Where Simone de Beauvoir loved and was loved by Nelson Algren it was the symbolical mating of worlds apparently opposite but linked by a contempt for the established order, and a need to destroy it.

All that has gone, no glamour left, and to read The Mandarins without those flattering veils has to be a sobering experience. What remains? For one, the politics of that time. Young people are always asking, But how was it possible that people could support the Soviet Union at all? Here it all is, the debates, the agonizings, the betrayals, the hair-splittings, the compromises and the self-deceptions. What it was all based on, what was never questioned, was the belief that no matter how terrible the Soviet Union was, it had to be better than capitalism, bound to be the future of the whole world once the infant communism was over its teething troubles. Another never-questioned pillar was that whatever decisions one made, whatever stance one took, were of importance to the whole world: the future of the world was at stake, dependent on the ‘correct’ or otherwise decisions of those people who – as the phrase then went – knew the score. Initiates – that was what they were, or how they saw themselves.

These politics already have something of the flavour of ancient religious squabbles, but the novel will continue to be read, I think, for an ironical reason: its brilliant portraits of women.

There is Josette, the sweet, passive beauty who was a collaborator with the Germans because of a rapacious and brutal mother, quite one of the nastiest women in fiction. There is Paula who will not admit that her great love is in fact ditching her, and lives in a state of delusion, claiming him for herself. Above all, there is Nadine, daughter as it were of this group of mandarins, sullen, angry, always resentful because of past but unspecified wrongs, unscrupulous, manipulative, unlovable and unloving, and finally getting her man by the oldest trick in the book. She is a psychological black hole, absorbing into itself all life, joy, pleasure, love. Never has there been a more unlikeable character, nor a more memorable one, for she dominates the book, even when she is off-stage. And finally, there is Anne Dubreuilh herself, the psychiatrist, whose kindness, patience and commonsense on behalf of others do not seem to do much for her own happiness.

The Mandarins is a novel that chronicles its time, but with all the advantages and disadvantages of immediacy, for large parts of it are like the hot, quick impatience of reporting.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_ae248210-dda5-5581-b118-c04f9fcf89ff)

Henri found himself looking at the sky again – a clear, black crystal dome overhead. It was difficult for the mind to conceive of hundreds of planes shattering that black crystalling silence! And suddenly, words began tumbling through his head with a joyous sound – the offensive was halted … the German collapse had begun … at last he would be able to leave. He turned the corner of the quay. The streets would smell again of oil and orange blossoms, in the evening there would be light, people would sit and chat in outdoor cafés, and he would drink real coffee to the sound of guitars. His eyes, his hands, his skin were hungry. It had been a long fast!

Slowly, he climbed the icy stairs. ‘At last!’ Paula exclaimed, hugging him tightly, as if they had just found each other again after a long, danger-filled separation. Over her shoulder, he looked at the tinselled Christmas tree, reflected to infinity in the large mirrors. The table was covered with plates, glasses, and bottles; bunches of holly and mistletoe lay scattered at the foot of a step-stool. He freed himself and threw his overcoat on the couch.

‘Have you heard the wireless?’ he asked. ‘The news is wonderful.’

‘Is it?’ Paula said. ‘Tell me, quickly!’ She never listened to the wireless; she wanted to hear the news only from Henri’s mouth.

‘Haven’t you noticed how clear the sky is tonight? They say there are a thousand planes smashing the rear of von Rundstedt’s armies.’

‘Thank God! They won’t come back, then.’

‘There never was any question of their coming back,’ he said. But the same thought had crossed his mind, too.

Paula smiled mysteriously. ‘I took precautions, just in case.’

‘What precautions?’

‘There’s a tiny room no bigger than a cupboard in the back of the cellar. I asked the concierge to clear it out for me. You could have used it as a hiding place.’

‘You shouldn’t have spoken to the concierge about a thing like that; that’s how panics are started.’

She clutched the ends of her shawl tightly in her left hand, as if she were protecting her heart. ‘They would have shot you,’ she said. ‘Every night I hear them; they knock, I open the door, I see them standing there.’ Motionless, her eyes half closed, she seemed actually to be hearing voices.

‘Don’t worry,’ Henri said cheerfully, ‘it will not happen now.’

She opened her eyes and let her hands fall to her sides. ‘Is the war really over?’

‘Well, it won’t last much longer,’ Henri replied, placing the stool under one of the heavy beams that crossed the ceiling. ‘Want me to help you?’ he asked.

‘The Dubreuilhs are coming over early to give me a hand.’

‘Why wait for them?’ he said, picking up a hammer.

Paula put her hand on his arm. ‘Aren’t you going to do any work?’ she asked.

‘Not tonight.’

‘But you say that every night. You haven’t written a thing for more than a year now.’

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘I feel like writing now, and that’s what counts.’

‘That newspaper of yours takes up too much of your time; just look at how late you get home. Besides, I’m sure you haven’t eaten a thing since noon. Aren’t you hungry?’

‘No, not now.’

‘Aren’t you even tired?’

‘Not at all.’

Those searching eyes of hers, so constantly devouring him with solicitude, made him feel like an unwieldy and fragile treasure. And it was that feeling which wearied him. He stepped up on the stool and with light, careful blows – the house had long since passed its youth – began driving a nail into the beam.

‘I can even tell you what I’m going to write,’ he said. ‘A light novel.’

‘What do you mean?’ Paula asked, her voice suddenly uneasy.

‘Exactly what I said. I feel like writing a light novel.’

Given even the slightest encouragement, he would have made up the story then and there, would have enjoyed thinking it out loud. But Paula was looking at him so intensely that he kept quiet.

‘Hand me that big bunch of mistletoe,’ he said instead.

Cautiously, he hung the green ball, studded with small white berry eyes, while Paula held out another nail to him. Yes, he thought, the war was really over. At least it was for him. This evening was going to be a real celebration. Peace would begin, everything would begin again – holidays, leisure trips, pleasure – maybe even happiness, but certainly freedom. He finished hanging the mistletoe, the holly, and the puffs of white cotton along the beam.

‘How does it look?’ he asked, stepping off the stool.

‘Perfect.’ She went over to the tree and straightened one of the candles. ‘If it’s no longer dangerous,’ she said quietly, ‘you’ll be going to Portugal now?’

‘Naturally.’

‘And you won’t do any work during the trip?’

‘I don’t suppose so.’

She stood nervously tapping one of the golden balls hanging from a branch of the tree, waiting for the words she had long been expecting.

‘I’m terribly sorry I can’t take you with me,’ he said finally.

‘You needn’t feel sorry,’ she said. ‘I know it’s not your fault. And anyhow, I feel less and less these days like traipsing about. What for?’ She smiled. ‘I’ll wait for you. Waiting, when you know what you’re waiting for, isn’t too bad.’

Henri felt like laughing aloud. What for? All those wonderful names – Lisbon, Oporto, Cintra, Coimbra – came alive in his mind. He didn’t even have to speak them to feel happy; it was enough to say to himself, ‘I won’t be here any more; I’ll be somewhere else.’ Somewhere else! Those words were more wonderful than even the most wonderful names.

‘Aren’t you going to get dressed?’ he asked.

‘I’m going,’ she said.

Paula climbed the stairway to the bedroom and Henri went over to the table. Suddenly he realized that he had been hungry. But he knew that whenever he admitted it a worried look would come over Paula’s face. He spread himself some pâté on a slice of bread and bit into it. Resolutely he told himself, ‘As soon as I get back from Portugal, I’ll move to a hotel. What a wonderful feeling it will be to return at night to a room where no one is waiting for you!’ Even when he was still in love with Paula, he had always insisted on having his own private four walls. But in ’39 and ’40, while he was in the army, Paula had had constant nightmares about falling dead on his horribly mutilated body, and when at last he was returned to her, how could he possibly refuse her anything? And then, what with the curfew, the arrangement turned out to be rather convenient, after all. ‘You can leave whenever you like,’ she would say. But up to now he hadn’t been able to. He took a bottle and twisted a corkscrew into the squeaking cork. Paula would get used to doing without him in less than a month. And if she didn’t, it would be just too damn bad! France was no longer a prison, the borders were opening up again, and life shouldn’t be a prison either. Four years of austerity, four years of working only for others – that was a lot, that was too much. It was time now for him to think a little about himself. And for that, he had to be alone, alone and free. It wouldn’t be easy to find himself again after four years; there were so many things that had to be clarified in his mind. What for instance? Well, he wasn’t quite sure yet, but there, in Portugal, strolling through the narrow streets which smelled of oil, he would try to bring things into focus. Again he felt his heart leap. The sky would be blue, laundry would be airing at open windows; his hands in his pockets, he would wander about as a tourist among people whose language he didn’t speak and whose troubles didn’t concern him.

He would let himself live, would feel himself living, and perhaps that alone would be enough to make everything come clear.

Paula came down the stairs with soft, silken steps. ‘You uncorked all the bottles!’ she exclaimed. ‘That was sweet of you.’

‘You’re so positively dedicated to violet!’ he said, smiling.

‘But you adore violet!’ she said.

He had been adoring violet for the past ten years; ten years was a long time.

‘You don’t like this dress?’ Paula asked.

‘Yes, of course,’ he said hastily. ‘It’s very pretty. I just thought that there were some other colours which might become you. Green, for example,’ he ventured, picking the first colour that came to mind.

She looked at herself in one of the mirrors. ‘Green?’ she said, and there was bewilderment in her voice. ‘You really think I’d look well in green?’

It was all so useless, he told himself. In green or yellow he would never again see in her the woman who, that day ten years earlier, he had desired so much when she had nonchalantly held out her long violet gloves to him.

Henri smiled at her gently. ‘Dance with me,’ he said.

‘Yes, let’s dance,’ she replied in a voice so ardent that it made him freeze up. Their life together had been so dismal during the past year that Paula herself had seemed to be losing her taste for it. But at the beginning of September, she changed abruptly; now, in her every word, every kiss, every look, there was a passionate quivering. When he took her in his arms she moved herself hard against him, murmuring, ‘Do you remember the first time we danced together?’

‘Yes, at the Pagoda. You told me I danced very badly.’

‘That was the day I took you to the Musée Grévin. You did not know about it. You did not know about anything,’ she said tenderly. She pressed her forehead against his cheek. ‘I can see us the way we were then.’

And so could he. They had stood together on a pedestal in the middle of the Palais des Mirages and everywhere around them they had seen themselves endlessly multiplied in a forest of mirrored columns. Tell me I’m the most beautiful of all women … You’re the most beautiful of all women … And you’ll be the most glorious man in the world …

Now he turned his eyes towards one of the large mirrors. Their entwined dancing bodies were infinitely repeated alongside an endless row of Christmas trees, and Paula was smiling at him blissfully. Didn’t she realize, he asked himself, that they were no longer the same couple?

‘Someone just knocked,’ Henri said, and he rushed to the door. It was the Dubreuilhs, heavily laden with shopping bags and baskets. Anne held a bunch of roses in her arms, and slung over Dubreuilh’s shoulder were huge bunches of red pimentos. Nadine followed them in, a sullen look on her face.

‘Merry Christmas!’

‘Merry Christmas!’

‘Did you hear the news? The air force was able to deliver at last.’

‘Yes, a thousand planes!’

‘They wiped them out.’

‘It’s all over.’

Dubreuilh dumped the load of red fruit on the couch. ‘Here’s something to decorate your little brothel.’

‘Thanks,’ Paula said coolly. It annoyed her when Dubreuilh called her studio a brothel – because of all the mirrors and those red draperies, he said.

He surveyed the room. ‘The centre beam is the only place for them; they’ll look a lot better up there than that mistletoe.’

‘I like the mistletoe,’ Paula said firmly.

‘Mistletoe is stupid; it’s round, it’s traditional. And moreover it’s a parasite.’

‘Why not string the pimentos along the railing at the head of the stairs,’ Anne suggested.

‘It would look much better up here,’ Dubreuilh replied.

‘I’m sticking to my holly and my mistletoe,’ Paula insisted.

‘All right, all right, it’s your home,’ Dubreuilh conceded. He beckoned to Nadine. ‘Come and help me,’ he said.

Anne unpacked a pork pâté, butter, cheese, cakes. ‘And this is for the punch,’ she said, setting two bottles of rum on the table. She placed a package in Paula’s hands. ‘Here, that’s your present. And here’s something for you,’ she said, handing Henri a clay pipe, the bowl shaped like a bird’s claw clutching a small egg. It was the same kind of pipe that Louis used to smoke fifteen years before.

‘Remarkable,’ said Henri. ‘How did you ever guess that I’ve been wanting a pipe like this for the past fifteen years?’

‘Simple,’ said Anne. ‘You told me.’

‘Two pounds of tea!’ Paula exclaimed. ‘You’ve saved my life! And does it smell good! Real tea!’

Henri began cutting slices of bread which Anne smeared with butter and Paula with the pork pâté. At the same time, Paula kept an anxious eye on Dubreuilh, who was hammering nails into the railing with heavy blows.

‘Do you know what’s missing here?’ he cried out to Paula. ‘A big crystal chandelier. I’ll dig one up for you.’

‘Don’t bother. I don’t want one.’

Dubreuilh finished hanging the clusters of pimentos and came down the stairs.

‘Not bad!’ he said, examining his work with a critical eye. He went over to the table and opened a small bag of spices; for years, on the slightest excuse, he had been concocting that same punch, the recipe for which he had learned in Haiti. Leaning against the railing, Nadine was chewing one of the pimentos; at eighteen, in spite of her experiences in the various French and American beds, she still seemed in the middle of the awkward age.

‘Don’t eat the scenery,’ Dubreuilh shouted at her. He emptied a bottle of rum into a salad bowl and turned towards Henri. ‘I met Samazelle the day before yesterday and I’m glad to say that he seems inclined to go along with us. Are you free tomorrow night?’

‘I can’t get away from the paper before eleven,’ Henri replied.

‘Then stop by at eleven,’ Dubreuilh said. ‘We have to go over the whole deal, and I’d very much like you to be there.’

Henri smiled. ‘I don’t quite see why.’

‘I told him that you work with me, but your actually being there will carry more weight.’

‘I doubt if it would mean very much to someone like Samazelle,’ Henry said, still smiling. ‘He must know I’m not a politician.’

‘But, like myself, he thinks that politics should never again be left to politicians,’ Dubreuilh said. ‘Come over, even if it’s only for a few minutes. Samazelle has an interesting group behind him. Young fellows; we need them.’

‘Now listen,’ Paula said angrily, ‘you’re not going to start talking politics again! Tonight’s a holiday.’

‘So?’ Dubreuilh said. ‘Is there a law against talking about things that interest you on holidays?’

‘Why do you insist on dragging Henri into this thing?’ Paula asked. ‘He knocks himself out enough already. And he’s told you again and again that politics bore him.’

‘I know,’ Dubreuilh said with a smile, ‘you think I’m an old reprobate trying to debauch his little friends. But politics isn’t a vice, my beauty, nor a parlour game. If a new war were to break out three years from now, you’d be the first to howl.’

‘That’s blackmail,’ Paula said. ‘When this war finally ends its coming to an end, no one is going to feel like starting a new one.’

‘Do you think that what people feel like doing means anything at all?’ Dubreuilh asked.

Paula started to answer, but Henri cut her off. ‘Look,’ he said. ‘It’s not that I don’t want to. It’s just that I haven’t got the time.’

‘There’s always time,’ Dubreuilh countered.

‘For you, yes,’ Henri said, laughing. ‘But me, I’m just a normal human being; I can’t work twenty hours at a stretch or go without sleep for a month.’

‘And neither can I!’ Dubreuilh said. ‘I’m not eighteen any more. No one is asking that much of you,’ he added, tasting the punch with a worried look.

Henri looked at him cheerfully. Eighteen or eighty, Dubreuilh, with his huge, laughing eyes that consumed everything in sight, would always look just as young. What a zealot! By comparison, Henri was often tempted to think of himself as dissipated, lazy, weak. But it was useless to drive himself. At twenty, he had had so great an admiration for Dubreuilh that he felt himself compelled to ape him. The result was that he was constantly sleepy, loaded himself with medicines, sank almost into a stupor. Now he had to make up his mind once and for all. With no time for himself he had lost his taste for life and the desire to write. He had become a machine. For four years he had been a machine, and now he was determined above all else to become a man again.

‘I wonder just how my inexperience could help you,’ he said.

‘Oh, inexperience has its advantages,’ Dubreuilh replied with a wry smile. ‘Besides, just now you have a name that means a lot to a lot of people.’ His smile broadened. ‘Before the war, Samazelle was in and out of every political faction and all the factions of factions. But that’s not why I want him; I want him because he’s a hero of the Maquis. His name carries a lot of weight.’

Henri began to laugh. Dubreuilh never seemed more ingenuous to him than when he tried being cynical. Paula was right, of course, to accuse him of blackmail; if he really believed in the imminence of a third world war, he would not have been in so good a mood. The truth of the matter was that he saw possibilities for action opening before him and he was burning to exploit them. Henri, however, felt less enthusiastic. Clearly, he had changed since ’39. Before then, he had been on the left because the bourgeoisie disgusted him, because injustice roused his indignation, because he considered all men his brothers – fine, generous sentiments which involved him in absolutely nothing. Now he knew that if he really wanted to break away from his class, he would have to risk some personal loss. Malefilatre, Bourgoin, Picard had taken the risk and lost at the edge of the little woods, but he would always think of them as living men. He had sat with them at a table in front of a rabbit stew, and they drank white wine and spoke of the future without much believing in what they were saying. Four of a kind, they were then. But with the war over they would once again have become a bourgeois, a farmer, and two mill hands. At that moment, sitting with them, Henri understood that in the eyes of the three others, and in his own eyes as well, he was one of the privileged classes, more or less disreputable, even if well-intentioned. And he knew there was only one way of remaining their friend: by continuing to do things with them. He understood this even more clearly when in ’41, he worked with the Bois Colombes group. At the beginning things didn’t go very well. Flamand exasperated him by incessantly repeating, ‘Me, I’m a worker, you know; I think like a worker.’ But thanks to him Henri became aware of something he knew nothing about before, something which, from that time on, he would always feel menacing him. Hate. He had taken the bite out of it; in their common struggle, they had accepted him as a comrade. But if ever he should become an indifferent bourgeois again, the hatred would come to life, and with good reason. Unless he showed proof to the contrary, he was the enemy of several hundred million men an enemy of humanity. And that he did not want at any price.

Now he had to prove himself. The trouble was that the struggle had shifted its form. The Resistance was one thing, politics another. And Henri had no great passion for politics. He knew what a movement such as Dubreuilh had in mind would mean: committees, conferences, congresses, meetings, talk, and still more talk. And it meant endless manoeuvring, patching up of differences, accepting crippling compromises, lost time, infuriating concessions, sombre boredom. Nothing could be more repulsive to him. Running a newspaper, that was the kind of work he enjoyed. But, of course, one thing did not preclude the other, and as a matter of fact they even complemented each other. It was impossible to use his paper as an excuse. Henri did not feel he had the right to look for an out; he would only try to limit his commitments.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘I can’t refuse you my name. I’ll put in a few appearances, too. But you mustn’t ask much more of me.’

‘I’ll certainly ask more of you than that,’ Dubreuilh replied.

‘Well, at any rate, not straight away. From now until I leave, I’ll be up to my ears in work.’

Dubreuilh looked Henri straight in the eyes. ‘The trip still on?’ he asked.

‘More than ever. Three weeks from now, at the latest, I’ll be gone.’

‘You’re not serious!’ Dubreuilh said angrily.

‘Now I’ve heard everything!’ Anne exclaimed, giving Dubreuilh a bantering look. ‘If you suddenly got an urge to go somewhere, you’d just pick yourself up and go, and you’d tell people it’s the only intelligent thing to do.’

‘But I don’t get those urges,’ Dubreuilh replied, ‘and that’s precisely wherein my superiority lies.’

‘I must say that the pleasures of travelling seem to me pretty much overrated,’ Paula said. She smiled at Anne. ‘A rose you bring me gives me more pleasure than the gardens of the Alhambra after a fifteen-hour train journey.’

‘Travel can be exciting enough,’ Dubreuilh said. ‘But just now it’s much more exciting being here.’

‘Well, as for me,’ Henri said, ‘I’ve got so strong an urge to be somewhere else that I’d go by foot if I had to. And with my shoes full of pebbles!’

‘And what about L’Espoir? You’ll just take off and leave it to itself for a whole month?’

‘Luc will get along quite well without me,’ Henri replied.

He looked at the three of them in amazement. ‘They don’t understand,’ he said to himself. ‘Always the same faces, the same surroundings, the same conversations, the same problems. The more it changes, the more it repeats itself. In the end, you feel as if you’re dying alive.’ Friendship, the great traditional emotions – he had valued them all for what they were worth. But now he needed something else, and the need was so violent that it would have been ridiculous even to attempt an explanation.

‘Merry Christmas!’

The door opened. Vincent, Lambert, Sézenac, Chancel, the whole gang from the newspaper, their cheeks pink from the cold. They had brought along bottles and records, and at the top of their voices they were singing the old refrain they had so often sung together during the feverish August days:

We’ve seen the last of the hun,

The bastards are all on the run.

Henri smiled at them cheerfully. He felt as young as they, and yet at the same time he also felt as if he had had a small hand in creating them. He joined in the chorus. Suddenly the lights went out, the punch flamed up, sparklers flared and Lambert and Vincent showered Henri with sparks. Paula lit the tiny candles on the Christmas tree.

‘Merry Christmas!’

Couples and small groups continued to arrive. They listened to Django Reinhardt’s guitar, danced, drank; everyone was laughing. Henri took Anne in his arms. In a voice filled with emotion she said, ‘It’s just like the night of the invasion; the same place, the same people.’

‘And now it’s all over.’

‘For us, it’s over,’ she corrected.

He knew what she was thinking. At that very moment Belgian villages were ablaze, the sea was foaming over the Dutch countryside. And yet here in Paris, it was a night of festivities, the first Christmas of the peace. There had to be festivities, sometimes. Because, if there weren’t, what good were victories? This was a holiday; he recognized that familiar smell of alcohol, of tobacco, of perfume and face powder, that smell of long nights. A thousand rainbow-tinted fountains danced in his memory. Before the war there had been so many nights – in the Montparnasse café where they all used to get drunk on coffee and conversation, in the old studios that smelled of still-wet oil paintings, in the little dance halls where he had held the most beautiful of all women, Paula, tightly in his arms. And always at dawn, accompanying the metallic sounds of morning, a gentle ecstatic voice inside him would whisper that the book he was writing would be good and that nothing in the world was more important.

‘You know,’ he said, ‘I’ve decided to write a light novel.’

‘You?’ Anne looked at him in amusement. ‘When do you begin?’

‘Tomorrow.’

Suddenly there was in him the urgent hurry to become again what he had once been, what he had always wanted to be – a writer. Deep inside him he knew again that uneasy joy that came with ‘I’m starting a new book.’ He would write of all those things that were just now being born again: the dawns, the long nights, the trips, happiness.

‘You’re in fine fettle tonight, aren’t you?’ Anne said.

‘I am. I feel as if I’ve just come out of a long dark tunnel. Don’t you?’

She paused a moment and then answered, ‘I don’t know. In spite of everything, there were some good moments in that tunnel.’

‘Yes, I suppose there were, at that.’

He smiled at her. She was looking pretty tonight, and he found her appealing in her severely tailored suit. If she hadn’t been an old friend – as well as Dubreuilh’s wife – he would willingly have tried his chances. He danced with Anne several times in succession and then with Claudie de Belzunce who, in plunging neckline and bedecked with the family jewels, had come slumming among the intellectual elite. Next time he danced with Jeanette Cange, then Lucie Lenoir. He knew them all too well, those women; but there would be other parties, other women.

Henri smiled at Preston who, somewhat unsteadily, was walking towards him across the room. He was the first American acquaintance Henri had come upon during the liberation of Paris in August, and they had fallen happily into each other’s arms.

‘Had to come and celebrate with you,’ Preston said.

‘Then let’s celebrate,’ said Henri.

They drank and then Preston began speaking sentimentally about New York nights. He was quite drunk and he leaned heavily on Henri’s shoulder. ‘You must come to New York,’ he said, and it sounded like a command. ‘I guarantee that you’ll be a huge success.’

‘Wonderful,’ said Henri. ‘I’ll come to New York.’

‘As soon as you get over, rent yourself a small plane,’ said Preston. ‘Best possible way to see the country.’

‘But I don’t know how to fly.’

‘Nothing to it. Easier than driving a car.’

‘Then I’ll learn to fly,’ said Henri.

Yes, decidedly, Portugal would be only a beginning. After that, there would be America, Mexico, Brazil, and maybe even Russia and China. In every place in the world Henri would drive cars again, would fly planes. The blue-grey air was great with promises; the future stretched away to infinity.

Suddenly a silence fell over the room. Henri saw with surprise that Paula was sitting down at the piano. She began to sing. It had been a very long time since that had happened. Henri tried to listen to her with an impartial ear; he had never been able to form a true opinion as to the value of that voice. Certainly it wasn’t mediocre; at times it even sounded like the echo of a bronze bell, muffled in velvet. Once again he asked himself why, exactly, she had given up singing. At the time, he had looked upon it as a sacrifice, an overpowering proof of her love for him. Later he was surprised to find that Paula continually avoided every opportunity that would have challenged her, and he had often wondered if she hadn’t used their love simply as a pretext to escape the test.

There was a burst of applause; Henri applauded with the others.

‘Her voice is still as beautiful as ever,’ Anne said quietly. ‘If she appeared in public again, I’m certain she’d be well received.’

‘Do you really think so?’ Henri asked. ‘Isn’t it a little late?’

‘Why? A few lessons …’ Anne looked hesitantly at Henri. ‘You know, I think it would do her good. You ought to encourage it.’

‘Perhaps you’re right,’ he said.

He studied Paula, who was smiling and listening to Claudie de Belzunce’s gushing compliments. No doubt about it, he thought. It would change her life. Being without anything to do was not doing her any good. And wouldn’t it just simplify things for him. And, after all, why not? Tonight everything seemed possible. Paula would become famous, she would devote herself to her career. And he would be free, would travel wherever he liked, would have brief, happy affairs here and there. Why not? He smiled and walked over to Nadine; she was standing next to the heater, gloomily chewing gum.

‘Why aren’t you dancing?’

She shrugged her shoulders. ‘With whom?’ she asked.

‘With me, if you like.’

She was not pretty. She looked too much like her father, and it was disturbing to see that surly face on the body of a young girl. Her eyes, like Anne’s, were blue, but so cold they seemed at once both worn-out and infantile. And yet, under her woollen dress, her body was more supple, her breasts more firm, than Henri had thought they would be.

‘This is the first time we’ve danced together,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘You dance well, you know.’

‘And that surprises you?’

‘Not particularly. But not one of these little snot-noses here knows how to dance.’

‘They hardly had the chance to learn.’

‘I know,’ she said. ‘We never had a chance to do anything.’

He smiled at her. A young woman is a woman, even if she is ugly. He liked her astringent smell of eau de Cologne, of fresh linen. She danced badly, but it didn’t really matter; there were the youthful voices, the laughter, the trumpet taking the chorus, the taste of the punch, the evergreens with their flaming, sparkling blossoms reflected in the depths of the mirrors, and, behind the curtains, a pure black sky. Dubreuilh was performing a trick; he had cut a newspaper into small pieces and had just put it together again with a sweep of his hand; Lambert and Vincent were duelling with empty bottles; Anne and Lachaume were singing grand opera; trains, ships, planes were circling the earth, and they could be boarded.

‘You dance pretty well yourself,’ he said politely.

‘I dance like a cow. But I don’t give a damn; I hate dancing.’ She looked at him suspiciously. ‘Jitterbugs, jazz, those cellars that stink of tobacco and sweat, do you find that sort of thing entertaining?’

‘From time to time,’ he replied. ‘Why? What do you find entertaining?’

‘Nothing.’

She spoke the word so fiercely that he looked at her with growing curiosity. He wondered if it was pleasure or disappointment that had thrown her into so many arms. Would true passion soften the hard structures of her face? And what would Dubreuilh’s head on a pillow look like?

‘When I think that you’re going to Portugal … well, all I can say is that you have all the luck,’ she said bitterly.

‘It won’t be long before it’s easy for everyone to travel again,’ he said.

‘It won’t be long! You mean a year, two years! How did you ever manage it?’

‘The French Propaganda Service asked me to give a few lectures.’

‘Obviously no one would ever ask me to give lectures,’ she muttered. ‘How many?’

‘Five or six.’

‘And you’ll be roaming around for a month!’

‘Well,’ he said gaily, ‘old people have to have some rewards.’

‘And what if you’re young?’ Nadine asked. She heaved a loud sigh. ‘If something would only happen …’

‘What, for instance?’

‘We’ve been in this so-called revolutionary era for ages. And yet nothing ever seems to change.’

‘Well, things did change a little in August, at any rate,’ Henri replied.

‘As I remember it, in August there was a lot of talk about everything changing. And it’s just the same as ever. It’s still the ones who work the most who eat the least, and everyone goes right on thinking that’s just marvellous.’

‘No one here thinks that’s marvellous,’ Henri protested.

‘Well, anyhow, they all learn to live with it,’ Nadine said irritably. ‘Having to waste your time working is lousy enough, and then on top of it you can’t eat your fill … well, personally, I’d rather be a gangster.’

‘I agree wholeheartedly; we all agree with you,’ Henri said. ‘But wait a while; you’re in too much of a hurry.’

Nadine interrupted him. ‘Look,’ she said, ‘the virtues of waiting have been explained to me at home at great length and in great detail. But I don’t trust explanations.’ She shrugged her shoulders. ‘Honestly, no one ever really tries to do anything.’

‘And what about you?’ Henri asked with a smile. ‘Do you ever try to do anything?’

‘Me? I’m not old enough,’ Nadine answered. ‘I’m just another butter ration.’

Henri burst out laughing. ‘Don’t get discouraged; you’ll soon be old enough. All too soon!’

‘Too soon! There are three hundred and sixty-five days in a year!’ Nadine said. ‘Count them.’ She lowered her head and thought silently for a moment. Then, abruptly, she raised her eyes. ‘Take me with you,’ she said.

‘Where?’ Henri asked.

‘To Portugal.’

He smiled. ‘That doesn’t seem too feasible.’

‘Just a little bit feasible will do fine,’ she said. Henri said nothing and Nadine continued in an insistent voice, ‘But why can’t it be done?’

‘In the first place, they wouldn’t give me two travel orders to leave the country.’

‘Oh, go on! You know everyone. Say that I’m your secretary.’ Nadine’s mouth was smiling, but her eyes were deadly serious.

‘If I took anyone,’ he said, ‘it would have to be Paula.’

‘But she doesn’t like travelling.’

‘Yes, but she’d be happy being with me.’

‘She’s seen you every single day for the last ten years, and there’s a lot more to come. One month more or less, what earthly difference could that make to her?’

Henri smiled at her. ‘I’ll bring you back some oranges,’ he said.

Nadine glowered at him, and suddenly Henri saw before him Dubreuilh’s intimidating mask. ‘I’m not eight years old any more, you know.’

‘I know.’

‘You don’t! To you I’ll always be the little brat who used to kick the logs in the fireplace.’

‘You’re completely wrong, and the proof of it is that I asked you to dance.’

‘Oh, this thing’s just a family affair. I’ll bet you’d never ask me to go out with you, though.’

He looked at her sympathetically. Here, at least, was one person who was longing for a change of air. Yes, she wanted a great many things, different things. Poor kid! It was true she had never had a chance to do anything. A bicycle tour of the suburbs: that was about the sum total of her travelling. It was certainly a rough way to spend one’s youth. And then there was that boy who had died; she seemed to have got over it quickly enough, but nevertheless it must have left a bad scar.

‘You’re wrong,’ he said. ‘I’m inviting you.’

‘Do you mean it?’ Nadine’s eyes shone. She was much easier to look at when her face brightened.

‘I don’t go back to the newspaper on Saturday nights. Let’s meet at the Bar Rouge at eight o’clock.’

‘And what will we do?’

‘That will be up to you.’

‘I don’t have any ideas.’

‘Well don’t worry, I’ll get one by then. Come and have a drink.’

‘I don’t drink. I wouldn’t mind another sandwich though.’

They went to the buffet. Lenoir and Julien were engaged in a heated discussion; it was chronic with them. Each reproached the other for having betrayed his youth – in the wrong way. At one time, having found the excesses of surrealism too tame, they jointly founded the ‘para-human’ movement. Lenoir had since become a professor of Sanskrit and he spent his free time writing obscure poetry. Julien, who was now a librarian, had stopped writing altogether, perhaps because he feared becoming a mature mediocrity after his precocious beginnings.

‘What do you think?’ Lenoir asked, turning to Henri. ‘We ought to take some kind of action against the collaborationist writers, shouldn’t we?’

‘I’ve stopped thinking for tonight,’ Henri answered cheerfully.

‘It’s poor strategy to keep them from being published,’ Julien said. ‘While you’re using all your strength preparing cases against them, they’ll have all the time in the world to write good books.’

A heavy hand came down on Henri’s shoulder: Scriassine.

‘Take a look at what I brought back. American whisky! I managed to slip two bottles into the country, and I can’t think of a better occasion than this to finish them off.’

‘Wonderful!’ said Henri. He filled a glass with bourbon and held it out to Nadine.

‘I don’t drink,’ she said in an offended voice, turning abruptly and walking off.

Henri raised the glass to his mouth. He had completely forgotten what bourbon tasted like; he did remember, though, that his preference used to be Scotch, but since he had also forgotten what Scotch tasted like, it made no difference to him.

‘Who wants a shot of real whisky?’

Luc came over, dragging his large, gouty feet; Lambert and Vincent followed close behind. They all filled their glasses.

‘I like a good cognac better,’ said Vincent.

‘This isn’t bad,’ Lambert said without conviction. He gave Scriassine a questioning look. ‘Do they really drink a dozen of these a day in America?’

‘They? Who are they?’ Scriassine asked. ‘There are a hundred and fifty million Americans, and, believe it or not, not all of them are like Hemingway heroes.’ His voice was harsh and disagreeable; he seldom made any effort to be friendly to people younger than himself. Deliberately, he turned to Henri. ‘I came over here tonight to have a serious talk with Dubreuilh. I’m quite worried.’

He looked preoccupied – his usual expression. He always created the impression that everything happening where he chanced to be and even where he chanced not to be – was his personal concern. Henri had no desire to share his worries. Offhandedly, he asked, ‘What’s worrying you so much?’

‘This movement he’s forming. I thought its principal objective was to draw the proletariat away from the Communist Party. But that’s not at all what Dubreuilh seems to have in mind,’ Scriassine said gloomily.

‘No, not at all,’ Henri replied.

Dejectedly, he thought, ‘This is just the kind of conversation I’ll be letting myself in for for days on end, if I get mixed up with Dubreuilh.’ From his head to his toes, he again felt an overpowering desire to be somewhere else.

Scraissine looked him straight in the eyes. ‘Are you going along with him?’

‘Only a little way,’ Henri answered. ‘Politics isn’t exactly my meat.’

‘You probably don’t understand what Dubreuilh is brewing,’ Scriassine said, giving Henri a reproachful look. ‘He’s trying to build up a so-called independent left-wing group, a group that approves of a united front with the Communists.’

‘Yes,’ Henri said. ‘I know that. So?’

‘Don’t you see? He’s playing right into their hands. There are a lot of people who are afraid of Communism; by winning them over to his movement, in effect he’ll be throwing their support to the Communists.’

‘Don’t tell me you’re against a united front,’ Henri said. ‘It would be a fine thing if the left started splitting up!’

‘A left dominated by the Communists would be nothing but a sham,’ Scriassine said. ‘If you’ve decided to go along with Dubreuilh, why not join the Communist Party? That would be a lot more honest.’

‘Completely out of the question. We disagree with them on quite a few points,’ Henri answered.

Scriassine shrugged his shoulders. ‘If you really do disagree with them, then three months from now the Stalinists will denounce you as traitors to the working class.’

‘We’ll see,’ Henri said.

He had no desire to continue the discussion, but Scriassine fixed him insistently with his eyes. ‘I’ve been told that L’Espoir has a lot of readers among the working people. Is that true?’

‘Yes.’

‘Which means you have in your hands the only non-Communist paper in France that reaches the proletariat. Do you realize the grave responsibility you have?’

‘I realize it.’

‘If you put L’Espoir at Dubreuilh’s service, you’ll be acting as an accomplice in a thoroughly disgusting manoeuvre,’ Scriassine said. ‘Dubreuilh’s friendship doesn’t matter here,’ he added, ‘you’ve got to go the other way.’

‘Listen, as far as the paper is concerned, it will never be at anyone’s service. Neither Dubreuilh’s nor yours,’ Henri said emphatically.

‘One of these days, you know, L’Espoir is going to have to define its political programme,’ Scriassine said.

‘No. I refuse to have any predetermined programme,’ said Henri. ‘I want to go on saying exactly what I think when I think it. And I’ll never let myself become regimented.’

‘That kind of policy won’t stand up,’ Scriassine said.

Luc’s normally placid voice suddenly broke in. ‘We don’t want any political programme; we want to preserve the unity of the Resistance.’

Henri poured himself a glass of bourbon. ‘That’s all a lot of crap!’ he grumbled. Old, worn-out cliches were all that Luc ever mouthed – The Spirit of the Resistance! The Unity of the Resistance! And Scriassine saw red whenever anyone mentioned Russia to him. It would be better if they each had a corner somewhere where they could rave by themselves! Henri emptied his glass. He needed no advice from anyone; he had his own ideas about what a newspaper should be. Obviously, L’Espoir would eventually be forced to take a political stand – but it would do it entirely independently. Henri hadn’t kept the paper going all this time only to see it turn into something like those pre-war rags. Then, the whole press had been dedicated to fooling the public; the knack of presenting one-sided views in a convincing, authoritative manner had become an art. And the result soon became apparent: deprived of their daily oracle, the people were lost. Today, everyone agreed more or less on the essentials; the polemics and the partisan campaigns were out. Now was the time to educate the readers instead of cramming things down their throats. No more dictating opinions to them; rather teach them to judge for themselves. It wasn’t simple. Often they insisted on answers, and he had to be constantly on his guard lest he gave them an impression of ignorance, doubt, or incoherence. But that was precisely the challenge – meriting their confidence rather than robbing them of it. And the fact that L’Espoir sold almost everywhere in France was proof enough that the method worked. ‘No point in damning the Communists for their sectarianism if you’re going to be just as dogmatic as they are,’ Henri said to himself.

‘Don’t you think we could put this discussion off to some other time?’ Henri asked, interrupting Scriassine.

‘All right,’ Scriassine answered. ‘Let’s make a date.’ He pulled a note-book from his pocket. ‘I think it’s important for us to talk over our differences.’

‘Let’s wait until I get back from my trip,’ Henri said.

‘You’re going on a trip? News-hawking?’

‘No, just for pleasure.’

‘Leaving soon?’

‘Very soon,’ Henri answered.

‘Wouldn’t you call that deserting?’ Scriassine asked.

‘Deserting?’ Henri said with a smile. ‘I’m not in the army, you know.’ With his chin, he pointed to Claudie de Belzunce. ‘You ought to ask Claudie for a dance. Over there … the half-naked one dripping with jewellery. She’s a real woman of the world, and, confidentially, she admires you a lot.’

‘Women of the world are one of my weaknesses,’ Scriassine said with a little smile. He shook his head. ‘I have to admit I don’t understand why.’

He moved off towards Claudie. Nadine was dancing with Lachaume, and Dubreuilh and Paula were circling around the Christmas tree. Paula did not like Dubreuilh, but he often succeeded in amusing her.

‘You really shocked Scriassine!’ Vincent said cheerfully.

‘My going on a trip seems to shock damned near everyone,’ Henri said. ‘And Dubreuilh most of all.’

‘That really beats me!’ Lambert said. ‘You did a lot more than any of them ever did. You’re entitled to a little holiday, aren’t you?’

‘There’s no doubt about it,’ Henri said to himself. ‘I have a lot more in common with the youngsters.’ Nadine envied him, Vincent and Lambert understood him. They, too, as soon as they could, had rushed off to see what was happening elsewhere in the world. When assignments as war correspondents were offered them, they had accepted without hestitation. Now he stayed with them as for the hundredth time they spoke of the exciting days when they had first moved into the offices of the newspaper, when they had sold L’Espoir right under the noses of the Germans while Henri was busy writing his editorials, a revolver in his desk drawer. Tonight, because he was hearing them as if from a distance, he found new charm in those old stories. In his imagination he was lying on a beach of soft, white sand, looking out upon the blue sea and calmly thinking of times gone by, of faraway friends. He was delighted at being alone and free. He was completely happy.

At four in the morning, he once again found himself in the red living-room. Many of the guests had already gone and the rest were preparing to leave. In a few moments he would be alone with Paula, would have to speak to her, caress her.

‘Darling, your party was a masterpiece,’ Claudie said, giving Paula a kiss. ‘And you have a magnificent voice. If you wanted to, you could easily be one of the sensations of the post-war era.’

‘Oh,’ Paula said gaily, ‘I’m not asking for that much.’

No, she didn’t have any ambition for that sort of thing. He knew exactly what she wanted: to be once more the most beautiful of women in the arms of the most glorious man in the world. It wasn’t going to be easy to make her change her dream. The last guests left; the studio was suddenly empty. A final shuffling on the stairway, and then steps clicking in the silent street. Paula began gathering up the glasses that had been left on the floor.

‘Claudie’s right,’ Henri said. ‘Your voice is still as beautiful as ever. It’s been so long since I last heard you sing! Why don’t you ever sing any more?’

Paula’s face lit up. ‘Do you still like my voice? Would you like me to sing for you sometimes?’

‘Certainly,’ he answered with a smile. ‘Do you know what Anne told me? She said you ought to begin singing in public again.’

Paula looked shocked. ‘Oh, no!’ she said. ‘Don’t speak to me about that. That was all settled a long time ago.’

‘Well, why not?’ Henri asked. ‘You heard how they applauded; they were all deeply moved. A lot of clubs are beginning to open up now, and people want to see new personalities.’

Paula interrupted him. ‘No! Please! Don’t insist. It horrifies me to think of displaying myself in public. Please don’t insist,’ she repeated pleadingly.

‘It horrifies you?’ he said, and his voice sounded perplexed. ‘I’m afraid I don’t understand. It never used to horrify you. And you don’t look any older, you know; in fact, you’ve grown even more beautiful.’

‘That was a different period of my life,’ Paula said, ‘a period that’s buried forever. I’ll sing for you and for no one else,’ she added with such fervour that Henri felt compelled to remain silent. But he promised himself to take up the subject again at the first opportunity.

There was a moment of silence, and then Paula spoke.

‘Shall we go upstairs?’ she asked.

Henri nodded. ‘Yes,’ he said.

Paula sat down on the bed, removed her earrings, and slipped her rings off her fingers. ‘You know,’ she said, and her voice was calm now, ‘I’m sorry if I seemed to disapprove of your trip.’

‘Don’t be silly! You certainly have the right not to like travelling, and to say so,’ Henri replied. The fact that she had scrupulously stifled her remorse all through the evening made him feel ill at ease.

‘I understand perfectly your wanting to leave,’ she said. ‘I even understand your wanting to go without me.’

‘It’s not that I want to.’

She cut him off with a gesture. ‘You don’t have to be polite.’ She put her hands flat on her knees and, with her eyes staring straight ahead and her back very straight, she looked like one of the infinitely calm priestesses of Apollo. ‘I never had any intention of imprisoning you in our love. You wouldn’t be you if you weren’t looking for new horizons, new nourishment.’ She leaned forward and looked Henri squarely in the face. ‘It’s quite enough for me simply to be necessary to you.’

Henri did not answer. He wanted neither to dishearten nor encourage her. ‘If only I had something against her,’ he thought. But no, not a single grievance, not a complaint.

Paula stood up and smiled; her face became human again. She put her hands on Henri’s shoulders, her cheek against his. ‘Could you get along without me?’

‘You know very well I couldn’t.’

‘Yes, I know,’ she said happily. ‘Even if you said you could, I wouldn’t believe you.’

She walked towards the bathroom. It was impossible not to weaken from time to time and speak a few kind words to her, smile gently at her. She stored those treasured relics in her heart and extracted miracles from them whenever she felt her faith wavering. ‘But in spite of everything, she knows I don’t love her any more,’ he said to himself for reassurance. He undressed and put on his pyjamas. She knew it, yes. But as long as she didn’t admit it to herself it meant nothing. He heard a rustle of silk, then the sound of running water and the clinking of glass, those sounds which once used to make his heart pound. ‘No, not tonight, not tonight,’ he said to himself uneasily. Paula appeared in the doorway, grave and nude, her hair tumbling over her shoulders. She was nearly as perfect as ever, but for Henri all her splendid beauty no longer meant anything. She slipped in between the sheets and without uttering a word, pressed her body to his. Paula withdrew her lips slightly, and, embarrassed, he heard her murmuring old endearments he never spoke to her now.

‘Am I still your beautiful wisteria vine?’

‘Now and always.’

‘And do you love me? Do you really still love me?’

He did not have the courage at that moment to provoke a scene, he was resigned to avow anything – and Paula knew it. ‘Yes, I do.’

‘Do you belong to me?’

‘To you alone.’

‘Tell me you love me, say it.’

‘I love you.’

She uttered a long moan of satisfaction. He embraced her violently, smothered her mouth with his lips, and to get it over with as quickly as possible immediately penetrated her.

When finally he fell limp on Paula, he heard a triumphant moan.

‘Are you happy?’ she murmured.

‘Of course.’

‘I’m so terribly happy!’ Paula exclaimed, looking at him through shining tear-brimmed eyes. He hid her unbearably bright face against his shoulder. ‘The almond trees will be in bloom …’ he said to himself, closing his eyes. ‘And there’ll be oranges hanging from the orange trees.’

II

No, I shan’t meet death today. Not today or any other day. I’ll be dead for others and yet I’ll never have known death.

I closed my eyes again, but I couldn’t sleep. Why had death entered my dreams once more? It is prowling inside me; I can feel it prowling there. Why?

I hadn’t always been aware that one day I would die. As a child, I believed in God. A white robe and two shimmering wings were awaiting me in heaven’s vestry and I wanted so much to break through the clouds and try them on. I would often lie down on my quilt, my hands clasped, and abandon myself to the delights of the hereafter. Sometimes in my sleep I would say to myself, ‘I’m dead,’ and the voice watching over me guaranteed me eternity. I was horrified when I first discovered the silence of death. A mermaid had died on a deserted beach. She had renounced her immortal soul for the love of a young man and all that remained of her was a bit of white foam without memory and without voice. ‘It’s only a fairy tale,’ I would say to myself for reassurance.

But it wasn’t a fairy tale. I was the mermaid. God became an abstract idea in the depths of the sky, and one evening I blotted it out altogether. I’ve never felt sorry about losing God, for He had robbed me of the earth. But one day I came to realize that in renouncing Him I had condemned myself to death. I was fifteen, and I cried out in fear in the empty house. When I regained my senses, I asked myself, ‘What do other people do? What will I do? Will I always live with this fear inside me?’

From the moment I fell in love with Robert, I never again felt fear, of anything. I had only to speak his name and I would feel safe and secure: he’s working in the next room … I can get up and open the door … But I remain in bed; I’m not sure any more that he too doesn’t hear that little, gnawing sound. The earth splits open under our feet, and above our heads there is an infinite abyss. I no longer know who we are, nor what awaits us.

Suddenly, I sat bolt upright, opened my eyes. How could I possibly admit to myself that Robert was in danger? How could I ever bear it? He hadn’t told me anything really disturbing, nothing really new. I’m tired, I drank too much; just a little four-o’clock-in-the-morning frenzy. But who’s to decide at what hour one sees things clearest? Wasn’t it precisely when I believed myself most secure that I used to awaken in frenzies? And did I ever really believe it?

I can’t quite remember. We didn’t pay very much attention to ourselves, Robert and I. Only events counted: the flight from Paris, the return, the sirens, the bombs, the standing in lines, our reunions, the first issues of L’Espoir. A brown candle was sputtering in Paula’s apartment. With a couple of tin cans, we had built a stove in which we used to burn scraps of paper. The smoke would sting our eyes. Outside, puddles of blood, the whistling of bullets, the rumbling of artillery and tanks. In all of us, the same silence, the same hunger, the same hope. Every morning we would awaken asking ourselves the same question: Is the swastika still flying above the Senate? And in August, when we danced around blazing bonfires in the streets of Montparnasse, the same joy was in all our hearts. Then the autumn slipped by, and only a few hours ago, while we were completing the task of forgetting our dead by the lights of a Christmas tree, I realized that we were beginning to exist again each for himself. ‘Do you think it’s possible to bring back the past?’ Paula had asked. And Henri had said, ‘I feel like writing a light novel.’ They could once again speak in their normal voices, have their books published; they could argue again, organize political groups, make plans. That’s why they were all so happy. Well, almost all. Anyhow, this isn’t the time for me to be tormenting myself. Tonight’s a holiday, the first Christmas of peace, the last Christmas at Buchenwald, the last Christmas on earth, the first Christmas Diego hasn’t lived through. We were dancing, we were kissing each other around the tree sparkling with promises, and there were many, oh, so many, who weren’t there. No one had heard their last words; they were buried nowhere, swallowed up in emptiness. Two days after the liberation, Geneviève had placed her hand on a coffin. Was it the right one? Jacques’s body had never been found; a friend claimed he had buried his notebooks under a tree. What notebooks? Which tree? Sonia had asked for a sweater and silk stockings, and then she never again asked for anything. Where were Rachel’s bones and the lovely Rosa’s? In the arms that had so often clasped Rosa’s soft body, Lambert was now holding Nadine and Nadine was laughing the way she used to laugh when Diego held her in his arms. I looked down the row of Christmas trees reflected in the large mirrors and I thought, ‘There are the candles and the holly and the mistletoe they’ll never see. Everything that’s been given me, I stole from them,’ They were killed. Which one first? He or his father? Death didn’t enter into his plans. Did he know he was going to die? Did he rebel at the end or was he resigned to it? How will I ever know? And now that he’s dead, what difference does it make?

No, tombstone, no date of death. That’s why I’ve been groping for him through that life he loved so tumultuously. I hold out my hand towards the light switch and hesitantly withdraw it. In my desk is a picture of Diego, but even though I looked at it for hours I would never find again under that head of bushy hair, his real face of flesh and bones, that face in which everything was too large – his eyes, nose, ears, mouth. He was sitting in the study and Robert had asked, ‘What will you do if the Nazis win?’ And he had answered, ‘A Nazi victory doesn’t enter into my plans.’ His plans consisted of marrying Nadine and becoming a great poet. And he might have made it, too. At sixteen he already knew how to turn words into hot, glowing embers. He might have needed only a very little time – five years, four years; he lived his life so fast. Huddled with the others around the electric heater, I used to enjoy watching him devour Hegel or Kant; he would turn the pages as rapidly as if he were skimming through a murder mystery. And the fact of the matter is that he understood perfectly everything he read. Only his dreams were slow.

He had come one day to show Robert his poems, which was how we first got to know him. His father was a Spanish Jew who was stubbornly determined to continue making money in business even during the Occupation. He claimed the Spanish consul was protecting him. Diego reproached him for his luxurious style of living and his opulent blonde mistress; he preferred our austerity and spent almost all his time with us. Besides, he was at the hero-worshipping age; and he worshipped Robert. The moment he met Nadine, he impetuously gave her his love, his first, his only love. For the first time she had a feeling of being needed; it overwhelmed her. She immediately made room in the house for Diego and invited him to live with us. He had a great deal of affection for me as well, even though he found me much too rational. At night, Nadine insisted upon my tucking her in, the way I used to when she was a child. Lying next to her, he would ask me, ‘And me? Don’t I get a kiss?’ And I would kiss him. That year, we had been friends, my daughter and I. I was grateful to her for being capable of a sincere love and she was thankful to me for not opposing her deepest desire. Why should I have? She was only seventeen, but both Robert and I felt that it’s never too early to be happy.

And they knew how to be happy with so much fire! When we were together, I would rediscover my youth. ‘Come and have dinner with us. Come on, tonight’s a holiday,’ they would say, each one pulling me by an arm. Diego had filched a gold piece from his father. He preferred to take rather than to receive; it was the way of his generation. He had no trouble in changing his treasure into negotiable money and he spent the afternoon with Nadine on the roller coaster at an amusement park. When I met them on the street that evening, they were devouring a huge pie they had bought in the back room of a nearby bakery; it was their way of working up an appetite. They called up Robert and asked him to come along too, but he refused to leave his work. I went with them. Their faces were smeared with jam, their hands black with the grime of the fairground, and in their eyes was the arrogant look of happy criminals. The maître d’hôtel must have surely believed we had come there with the intention of squandering some ill-gotten gains. He showed us to a table far in the rear of the room and asked Diego with chilly politeness, ‘Monsieur has no jacket?’ Nadine threw her jacket over Diego’s threadbare sweater, revealing her own soiled, wrinkled blouse. But in spite of it all, we were served. They ordered ice cream first, and sardines, and then steaks, fried potatoes, oysters, and still more ice cream. ‘It all gets mixed up inside anyhow,’ they explained to me, stuffing the food into their mouths. They were so happy to be able for once to eat their fill! No matter how hard I tried to get enough food to go around, we were always more or less hungry. ‘Eat up,’ they said to me commandingly, as they slipped slices of pâté into their pockets for Robert.

It wasn’t long after this that the Germans one morning knocked at Mr Serra’s door. No one had informed him that the Spanish consul had been transferred. Diego, as luck would have it, had slept at his father’s that night. They didn’t take the blonde. ‘Tell Nadine not to worry about me,’ Diego said. ‘I’ll come back, because I want to come back.’ Those were the last words we ever heard from him; all his other words were drowned out forever, he who loved so much to talk.

It was springtime and the sky was very blue, the peach trees a pastel pink. When we would ride our bicycles, Nadine and I, through the flag-decked parks of Paris, the fragrant joy of peacetime weekends filled our lungs. But the tall buildings of Drancy, where the prisoners were kept, brutally crushed that lie. The blonde had handed over three million francs to a German named Felix who transmitted messages from the prisoners and who had promised to help them escape. Twice, peering through binoculars, we were able to pick out Diego standing at a distant window. They had shaved off his woolly hair and it was no longer entirely he who smiled back at us; his mutilated head seemed even then to belong to another world.

One afternoon in May we found the huge barracks deserted; straw mattresses were being aired at the open windows of empty rooms. At the café where we had parked our bicycles, they told us that three trains had left the station during the night. Standing by the barbed-wire fence, we watched and waited for a long time. And then suddenly, very far off, very high up, we made out two solitary silhouettes leaning out of a window. The younger one waved his beret triumphantly. Felix had spoken the truth: Diego had not been deported. Choked with joy, we rode back to Paris.

‘They’re in a camp with American prisoners,’ the blonde told us. ‘They’re doing fine, taking lots of sun baths.’ But she hadn’t actually seen them. We sent them sweaters and chocolate, and they thanked us for the gifts through the mouth of Felix. But we stopped receiving written messages. Nadine insisted upon some sort of sign to prove they were still alive – Diego’s ring, a lock of his hair. But it was just then that they changed camps again, were sent somewhere far from Paris. It became increasingly difficult to locate them in any particular place; they were gone, that was all. To be nowhere or not to be at all isn’t very different. Nothing really changed when at last Felix said irritably, ‘They killed them a long time ago.’

Nadine wept frantically night after night, and I held her in my arms from evening till morning. Then she found sleep once more. At first Diego appeared every night in her dreams, a wretched look on his face. Later even his spectre vanished. She was right; I can’t really blame her. What can you do with a corpse? Yes, I know. They serve as excuses for making flags, heroic statues, guns, medals, speeches, and even souvenirs for decorating the home. It would be far better to leave their ashes in peace. Monuments or dust. And they had been our brothers. But after all, we had no choice in the matter. Why did they leave us? If only they would leave us in peace! Let’s forget them, I say. Let’s think a little about ourselves now. We’ve more than enough to do remaking our own lives. The dead are dead; for them there are no more problems. But after this night of festivity, we, the living, will awaken again. And then how shall we live?

Nadine and Lambert were laughing together, a record was playing loudly, the floor was trembling under our feet, the blue flames of the candles were flickering. I looked at Sézenac who was lying on the rug, thinking no doubt of those glorious days when he strutted down the boulevards of Paris with a rifle slung over his shoulder. I looked at Chancel who had been condemned to death by the Germans and at the last moment exchanged for one of their prisoners. And Lambert whose father had denounced his fiancée, and Vincent who had killed a dozen of our home-grown Nazi militiamen with his own hands. What will they all do with those pasts of theirs, so grievous and so brief? And what will they do with their shapeless futures? Will I know how to help them? Helping people is my job; I make them lie down on a couch and pour out their dreams to me. But I can’t bring Rosa back to life, nor the twelve Nazis Vincent killed. And even if I were somehow able to neutralize their pasts, what kind of future could I offer them? I quiet fears, harness dreams, restrain desires; I make them adjust themselves. But to what? I can no longer see anything around me that makes sense.

No question about it, I had too much to drink. After all, it wasn’t I who created heaven and earth; no one’s asking me to give an accounting of myself. Why must I forever be worrying about others? I’d do better to worry a little about myself for a change. I press my cheek against the pillow; I’m here, it’s I. The trouble is there’s nothing about me worth giving much thought to. Oh, if someone asks who I am, I can always show him my case history; to become an analyst, I had to be analysed. It was found that I had a rather pronounced Oedipus complex, which explains my marriage to a man twenty years my elder, a clear aggressiveness towards my mother, and some slight homosexual tendencies which conveniently disappeared. To my Catholic upbringing I owe a highly developed super ego – the reason for my puritanism and my lack of narcissism. The ambivalent feelings I have in regard to my daughter stem from my aversion to my mother as much as to my indifference concerning myself. My case is one of the most classic types; its segments fall neatly into a predictable pattern. From a Catholic point of view, it’s also quite banal: in their eyes I stopped believing in God when I discovered the temptations of the flesh, and my marriage to an unbeliever completed my downfall. Politically and socially Robert and I were left-wing intellectuals. Nothing in all this is entirely inexact. There I am then, clearly catalogued and willing to be so, adjusted to my husband, to my profession, to life, to death, to the world and all its horrors; me, precisely me, that is to say, no one.

To be no one, all things considered, is something of a privilege. I watched them coming and going in the room, all of them with their important names, and I didn’t envy them. For Robert it was all right; he was predestined to be what he was. But the others, how do they dare? How can anyone be so arrogant or so rash as to serve himself up as prey to a pack of strangers? Their names are dirtied in thousands of mouths; the curious rob them of their thoughts, their hearts, their lives. If I too were subjected to the cupidity of that ferocious mob of ragpickers, I would certainly end up by considering myself nothing but a pile of garbage. I congratulated myself for not being someone.

I went over to Paula. The war had not affected her aggressive elegance. She was wearing a long, silk, violet-coloured gown, and from her ears hung clusters of amethysts.

‘You’re very lovely tonight,’ I said.

She looked at herself quickly in one of the large mirrors. ‘Yes, I know,’ she said sadly. ‘I’m lovely.’