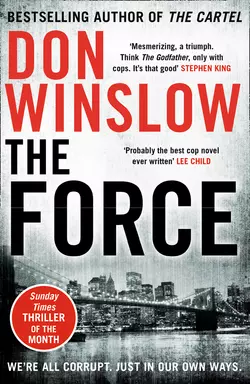

The Force

Don Winslow

‘Probably the best cop novel ever written’ Lee ChildFrom the New York Times bestselling author of The Cartel – winner of the Ian Fleming Steel Dagger Award for Best Thriller of the Year – comes The Force, a cinematic epic as explosive, powerful, and unforgettable as The Wire.Everyone can be bought. At the right price…Detective Sergeant Denny Malone leads an elite unit to fight gangs, drugs and guns in New York. For eighteen years he’s been on the front lines, doing whatever it takes to survive in a city built by ambition and corruption, where no one is clean.What only a few know is that Denny Malone himself is dirty: he and his partners have stolen millions of dollars in drugs and cash. Now he’s caught in a trap and being squeezed by the FBI. He must walk a thin line of betrayal, while the city teeters on the brink of a racial conflagration that could destroy them all.

Copyright (#ulink_f99616aa-7ff3-5986-9f50-f9e05378102e)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

First published in the United States by William Morrow,

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Samburu, Inc 2017

Don Winslow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008227487

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2017 © ISBN: 9780008227500

Version: 2018-01-09

During the time that I was writing this novel, the following law enforcement personnel were murdered in the line of duty. This book is dedicated to them:

Sergeant Cory Blake Wride, Deputy Sheriff Percy Lee House III, Deputy Sheriff Jonathan Scott Pine, Correctional Officer Amanda Beth Baker, Detective John Thomas Hobbs, Agent Joaquin Correa-Ortega, Officer Jason Marc Crisp, Chief Deputy Sheriff Allen Ray “Pete” Richardson, Officer Robert Gordon German, Master-at-Arms Mark Aaron Mayo, Officer Mark Hayden Larson, Officer Alexander Edward Thalmann, Officer David Wayne Smith Jr., Officer Christopher Alan Cortijo, Deputy Sheriff Michael J. Seversen, Trooper Gabriel Lenox Rich, Sergeant Patrick “Scott” Johnson, Officer Roberto Carlos Sanchez, Trooper Chelsea Renee Richard, Master Sergeant John Thomas Collum, Officer Michael Alexander Petrina, Detective Charles David Dinwiddie, Officer Stephen J. Arkell, Officer Jair Abelardo Cabrera, Trooper Christopher G. Skinner, Special Deputy Marshal Frank Edward McKnight, Officer Brian Wayne Jones, Officer Kevin Dorian Jordan, Officer Igor Soldo, Officer Alyn Ronnie Beck, Chief of Police Lee Dixon, Deputy Sheriff Allen Morris Bares Jr., Officer Perry Wayne Renn, Patrolman Jeffrey Brady Westerfield, Detective Melvin Vincent Santiago, Officer Scott Thomas Patrick, Chief of Police Michael Anthony Pimentel, Agent Geniel Amaro-Fantauzzi, Officer Daryl Pierson, Patrolman Nickolaus Edward Schultz, Corporal Jason Eugene Harwood, Deputy Sheriff Joseph John Matuskovic, Corporal Bryon Keith Dickson II, Deputy Sheriff Michael Andrew Norris, Sergeant Michael Joe Naylor, Deputy Sheriff Danny Paul Oliver, Detective Michael David Davis Jr., Deputy Sheriff Yevhen “Eugene” Kostiuchenko, Deputy Sheriff Jesse Valdez III, Officer Shaun Richard Diamond, Officer David Smith Payne, Constable Robert Parker White, Deputy Sheriff Matthew Scott Chism, Officer Justin Robert Winebrenner, Deputy Sheriff Christopher Lynd Smith, Agent Edwin O. Roman-Acevedo, Officer Wenjian Liu, Officer Rafael Ramos, Officer Charles Kondek, Officer Tyler Jacob Stewart, Detective Terence Avery Green, Officer Robert Wilson III, Deputy U.S. Marshal Josie Wells, Patrolman George S. Nissen, Officer Alex K. Yazzie, Officer Michael Johnson, Trooper Trevor Casper, Officer Brian Raymond Moore, Sergeant Greg Moore, Officer Liquori Tate, Officer Benjamin Deen, Deputy Sonny Smith, Detective Kerrie Orozco, Trooper Taylor Thyfault, Patrolman James Arthur Bennett Jr., Officer Gregg “Nigel” Benner, Officer Rick Silva, Officer Sonny Kim, Officer Daryle Holloway, Sergeant Christopher Kelley, Corrections Officer Timothy Davison, Sergeant Scott Lunger, Officer Sean Michael Bolton, Officer Thomas Joseph LaValley, Deputy Sheriff Carl G. Howell, Trooper Steven Vincent, Officer Henry Nelson, Deputy Sheriff Darren Goforth, Sergeant Miguel Perez-Rios, Trooper Joseph Cameron Ponder, Deputy Sheriff Dwight Darwin Maness, Deputy Sheriff Bill Myers, Officer Gregory Thomas Alia, Detective Randolph A. Holder, Officer Daniel Scott Webster, Officer Bryce Edward Hanes, Officer Daniel Neil Ellis, Chief of Police Darrell Lemond Allen, Trooper Jaimie Lynn Jursevics, Officer Ricardo Galvez, Corporal William Matthew Solomon, Officer Garrett Preston Russell Swasey, Officer Lloyd E. Reed Jr., Officer Noah Leotta, Commander Frank Roman Rodriguez, Lieutenant Luz M. Soto Segarra, Agent Rosario Hernandez de Hoyos, Officer Thomas W. Cottrell Jr., Special Agent Scott McGuire, Officer Douglas Scott Barney II, Sergeant Jason Goodding, Deputy Derek Geer, Deputy Mark F. Logsdon, Deputy Patrick B. Dailey, Major Gregory E. “Lem” Barney, Officer Jason Moszer, Special Agent Lee Tartt, Corporal Nate Carrigan, Officer Ashley Marie Guindon, Officer David Stefan Hofer, Deputy Sheriff John Robert Kotfila Jr., Officer Allen Lee Jacobs, Deputy Carl A. Koontz, Officer Carlos Puente-Morales, Officer Susan Louise Farrell, Trooper Chad Phillip Dermyer, Officer Steven M. Smith, Detective Brad D. Lancaster, Officer David Glasser, Officer Ronald Tarentino Jr., Officer Verdell Smith Sr., Officer Natasha Maria Hunter, Officer Endy Nddiobong Ekpanya, Deputy Sheriff David Francis Michel Jr., Officer Brent Alan Thompson, Sergeant Michael Joseph Smith, Officer Patrick E. Zamarripa, Officer Lorne Bradley Ahrens, Officer Michael Leslie Krol, Security Supervisor Joseph Zangaro, Court Officer Ronald Eugene Kienzle, Deputy Sheriff Bradford Allen Garafola, Officer Matthew Lane Gerald, Corporal Montrell Lyle Jackson, Officer Marco Antonio Zarate, Corrections Officer Mari Johnson, Correctional Officer Kristopher D. Moules, Captain Robert D. Melton, Officer Clint Corvinus, Officer Jonathan De Guzman, Officer José Ismael Chavez, Special Agent De’Greaun Frazier, Corporal Bill Cooper, Officer John Scott Martin, Officer Kenneth Ray Moats, Officer Kevin “Tim” Smith, Sergeant Steve Owen, Master Deputy Sheriff Brandon Collins, Officer Timothy James Brackeen, Officer Lesley Zerebny, Officer Jose Gilbert Vega, Officer Scott Leslie Bashioum, Sergeant Luis A. Meléndez-Maldonado, Deputy Sheriff Jack Hopkins, Correctional Officer Kenneth Bettis, Deputy Sheriff Dan Glaze, Officer Myron Jarrett, Sergeant Allen Brandt, Officer Blake Curtis Snyder, Sergeant Kenneth Steil, Officer Justin Martin, Sergeant Anthony Beminio, Sergeant Paul Tuozzolo, Deputy Sheriff Dennis Wallace, Detective Benjamin Edward Marconi, Deputy Commander Patrick Thomas Carothers, Officer Collin James Rose, Trooper Cody James Donahue.

Epigraph (#ulink_36a381a1-b174-5861-a83c-ac0612635e3d)

“Cops are just people,” she said irrelevantly.

“They start out that way, I’ve heard.”

—RAYMOND CHANDLER, FAREWELL, MY LOVELY

Contents

Cover (#uf24522dc-0d03-589c-9058-2288d0aec014)

Title Page (#ua331d4c1-07b9-5187-b31a-31a8969c8d11)

Copyright (#u816c7074-bcea-5ab5-9c6e-ff4645afb75a)

Epigraph (#ub00d72f9-44d0-527a-8178-c56936162bc8)

The Last Guy (#uc2af6c64-97b5-5b7b-af34-d6dd50bcb734)

Prologue: The Rip (#uae325a4e-64d1-5560-a3a7-88e10b1f4bb4)

Part 1: White Christmas (#u20701876-7b21-53b7-add4-a842c987de0c)

Chapter 1 (#u845151c9-fdc2-5222-866c-51a63bdbbbc1)

Chapter 2 (#ufa352ef7-5bae-5883-96fd-c1c1c226fc10)

Chapter 3 (#uc81c3fc7-3ff8-576b-b92a-6ea2f8b5f75e)

Chapter 4 (#u3a1d40ff-a44f-598e-9195-ce08b25713fb)

Chapter 5 (#u7b54d63c-3f9c-5c95-b7c0-23480e803520)

Part 2: The Easter Bunny (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3: Fourth of July, the Fire This Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Don Winslow (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

THE LAST GUY (#ulink_76cf0110-9311-5813-85a2-4a789fca93ca)

The last guy on earth anyone ever expected to end up in the Metropolitan Correctional Center on Park Row was Denny Malone.

You said the mayor, the president of the United States, the pope—people in New York would have laid odds they’d see them behind bars before they saw Detective First Grade Dennis John Malone.

A hero cop.

The son of a hero cop.

A veteran sergeant in the NYPD’s most elite unit.

The Manhattan North Special Task Force.

And, most of all, a guy who knows where all the skeletons are hidden, because he put half of them there himself.

Malone and Russo and Billy O and Big Monty and the rest made these streets their own, and they ruled them like kings. They made them safe and kept them safe for the decent people trying to make lives there, and that was their job and their passion and their love, and if that meant they worked the corners of the plate and put a little something extra on the ball now and then, that’s what they did.

The people, they don’t know what it takes sometimes to keep them safe and it’s better that they don’t.

They may think they want to know, they may say they want to know, but they don’t.

Malone and the Task Force, they weren’t just any cops on the Job. You got thirty-eight thousand wearing blue, Denny Malone and his guys were the 1 percent of the 1 percent of the 1 percent—the smartest, the toughest, the quickest, the bravest, the best, the baddest.

The Manhattan North Special Task Force.

“Da Force” blew through the city like a cold, harsh, fast and violent wind, scouring the streets and alleys, the playgrounds, parks and projects, scraping away the trash and the filth, a predatory storm blowing away the predators.

A strong wind finds its way through every crack, into the project stairwells, the tenement heroin mills, the social club back rooms, the new-money condos, the old-money penthouses. From Columbus Circle to the Henry Hudson Bridge, Riverside Park to the Harlem River, up Broadway and Amsterdam, down Lenox and St. Nicholas, on the numbered streets that spanned the Upper West Side, Harlem, Washington Heights and Inwood, if there was a secret Da Force didn’t know about, it was because it hadn’t been whispered about or even thought of yet.

Drug deals and gun deals, traffic in people and property, rapes, robberies and assaults, crimes hatched in English, Spanish, French, Russian over collard greens and smothered chicken or jerk pork or pasta marinara or gourmet meals at five-star restaurants in a city made from sin and for profit.

Da Force hit them all, but especially guns and drugs, because guns kill and drugs incite the killings.

Now Malone’s in lockup, the wind has stopped blowing, but everyone knows it’s the eye of the storm, the dead quiet lull that comes before the worst of it. Denny Malone in the hands of the feds? Not IAB, not the state’s attorneys, but the feds, where no one in the city can touch him?

Everyone’s hunkered down, shitting bricks and waiting for that blow, that tsunami, because with what Malone knows, he could take out commanders, chiefs, even the commissioner. He could roll on prosecutors, judges—shit, he could serve the feds the mayor on the proverbial silver platter with at least one congressman and a couple of real estate billionaires as appetizers.

So as the word went out that Malone was sitting in the MCC, people in the eye of the hurricane got scared, real scared, started to seek shelter even in the calm, even knowing that there are no walls high enough, no cellars deep enough—not at One Police, not at the Criminal Courts Building, not even at Gracie Mansion or in the penthouse palaces lining Fifth Avenue and Central Park South—to keep them safe from what’s in Denny Malone’s head.

If Malone wants to pull the whole city down around him, he can.

Then again, no one’s ever really been safe from Malone and his crew.

Malone’s guys made headlines—the Daily News, the Post, Channels 7, 4 and 2; “film at eleven” cops. Recognized-on-the-street cops, the-mayor-knows-your-name cops, comped seats at the Garden, the Meadowlands, Yankee Stadium and Shea, walk-into-any-restaurant-bar-or-club-in-the-city-and-get-treated-like-royalty cops.

And of this pack of alphas, Denny Malone is the undisputed leader.

Walks into any house in the city, the uniforms and the rookies stop and stare, the lieutenants give him a nod, even the captains know not to step on his shoes.

He’s earned their respect.

Among other things (Shit, you want to talk about the robberies he stopped, the bullet he took, the kid in that hostage situation he saved? The busts, the takedowns, the convictions?), Malone and his team, they made the biggest drug bust in the history of New York.

Fifty kilos of heroin.

And the Dominican who was trafficking it gone.

Along with a hero cop.

Malone’s crew laid their partner in the ground—bagpipes, folded flag, black ribbons over shields—and went right back to work because the slingers and the gangs and the robbers and the rapists and the wiseguys, they don’t take time off to grieve. You wanna keep your streets safe, you gotta be on those streets—days, nights, weekends, holidays, whatever it takes, and your wives, they knew what they signed up for, and your kids, they learn to understand that’s what Daddy does, he puts the bad guys behind bars.

Except now it’s him in the cage, Malone sitting on a steel bench in a holding cell like the dirtbags he usually puts there, bent over, his head in his hands, worrying about his partners—his brothers on Da Force—and what’s going to happen to them now that he’s put them neck deep in shit.

Worrying about his family—his wife, who didn’t sign up for this, his two kids, a son and a daughter who are too young to understand now, but when they’re old enough are never going to forgive why they had to grow up without a father.

Then there’s Claudette.

Fucked up in her own way.

Needy, needing him, and he’s not going to be there.

For her or for anybody, so he doesn’t know now what’s going to happen to the people he loves.

The wall he’s staring at doesn’t have any answers, either, as to how he got here.

No, fuck that, Malone thinks. At least be honest with yourself, he thinks as he sits there with nothing in front of him but time.

At least, at last, tell yourself the truth.

You know exactly how you got here.

Step by motherfucking step.

Our ends know our beginnings but the reverse isn’t true.

When Malone was a kid, the nuns taught him that even before we’re born, God—and only God—knows the days of our lives and the day of our death and who and what we’ll become.

Well, I wish he’d fucking shared it with me, Malone thinks. Given me a word, a tip, dimed me out, ratted on me to myself, told me something, anything. Said, Hey, jerkoff, you took a left, you should have gone right.

But no, nothing.

All he’s seen, Malone isn’t a big fan of God and figures the feeling is mutual. He has a lot of questions he’d like to ask him, but if he ever got him in the room, God’d probably shut his mouth, lawyer up, let his own kid take the jolt.

All this time on the Job, Malone lost his faith, so when the moment came when he was looking the devil in the eye, there was nothing between Malone and murder except ten pounds of trigger pull.

Ten pounds of gravity.

It was Malone’s finger pulled the trigger, but maybe it was gravity that pulled him down—the relentless, unforgiving gravity of eighteen years on the Job.

Pulling him down to where he is now.

Malone didn’t start out to end up here. Didn’t throw his hat in the air the day he graduated the Academy and took the oath, the happiest day of his life—the brightest, bluest, best day—thinking that he’d end up here.

No, he started with his eyes firmly on the guiding star, his feet planted on the path, but that’s the thing about the life you walk—you start out pointed true north, but you vary one degree off, it doesn’t matter for maybe one year, five years, but as the years stack up you’re just walking farther and farther away from where you started out to go, you don’t even know you’re lost until you’re so far from your original destination you can’t even see it anymore.

You can’t even get back on the path to start over.

Time and gravity won’t allow it.

And Denny Malone would give a lot to start over.

Hell, he’d give everything.

Because he never thought he’d end up in the federal lockup on Park Row. No one did, except maybe God, and he wasn’t talking.

But here Malone is.

Without his gun or his shield or anything else that says what and who he is, what and who he was.

A dirty cop.

PROLOGUE (#ulink_bcfbdc03-71ad-598b-8a0d-11fd3c95c7ea)

(#ulink_bcfbdc03-71ad-598b-8a0d-11fd3c95c7ea)

Lenox Avenue,

Honey.

Midnight.

And the gods are laughing at us.

—LANGSTON HUGHES, “LENOX AVENUE: MIDNIGHT”

Harlem, New York City

July 2016

Four A.M.

When the city that never sleeps at least lies down and closes its eyes.

This is what Denny Malone thinks as his Crown Vic slides up the spine of Harlem.

Behind the walls and windows, in apartments and hotels, tenements and project towers, people are sleeping or can’t, are dreaming or are beyond dreams. People are fighting or fucking or both, making love and making babies, screaming curses or speaking soft, intimate words meant for each other and not the street. Some try to rock infants back to sleep, or are just getting up for another day of work, while others cut kilos of heroin into glassine bags to sell to the addicts for their wake-up shots.

After the hookers and before the street cleaners, that’s the window of time you have to make a rip, Malone knows. Nothing good ever happens after midnight, is what his old man used to say, and he knew. He was a cop on these streets, coming home in the morning after a graveyard shift with murder in his eyes, death in his nose and an icicle in his heart that never melted and eventually killed him. Got out of the car in the driveway one morning and his heart cracked. The doctors said he was dead before he hit the ground.

Malone found him there.

Eight years old, leaving the house to walk to school, he saw the blue overcoat in the pile of dirty snow he’d helped his dad shovel off the driveway.

Now it’s before dawn and already hot. One of those summers when God the landlord refuses to turn the heat down or the air-conditioning on—the city edgy and irritable, on the brink of a flameout, a fight or a riot, the smell of old garbage and stale urine, sweet, sour, sickly and corrupt as an old whore’s perfume.

Denny Malone loves it.

Even in the daytime when it’s baking hot and noisy, when the gangbangers are on the corners and the hip-hop bass beats hurt your ears, and bottles, cans, dirty diapers and plastic bags of piss come flying out of project windows, and the dog shit stinks in the fetid heat, he wouldn’t be anywhere else in the world.

It’s his city, his turf, his heart.

Rolling up Lenox now, past the old Mount Morris Park neighborhood and its graceful brownstones, Malone worships the small gods of place—the twin towers of Ebenezer Gospel Tabernacle, where the hymns float out on Sundays with the voices of angels, then the distinctive spire of Ephesus Seventh-Day Adventist and, farther up the block, Harlem Shake—not the dance but some of the best damn burgers in the city.

Then there are the dead gods—the old Lenox Lounge, with its iconic neon sign, red front and all that history. Billie Holiday used to sing there, Miles Davis and John Coltrane played their horns, and it was a hang for James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Malcolm X. It’s closed now—the window covered with brown paper, the sign dark—but there’s talk about opening it again.

Malone doubts it.

Dead gods don’t rise again except in fairy tales.

He crosses 125th, a.k.a. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Urban pioneers and the black middle class have gentrified the area, which the Realtors have now christened “SoHa,” a blended acronym always being the death knell of any old neighborhood, Malone thinks. He’s convinced that if real estate developers could buy properties in the bottom levels of Dante’s Inferno they’d rename it “LoHel” and start throwing up boutiques and condos.

Fifteen years ago, this stretch of Lenox was empty storefronts; now it’s trendy again with new restaurants, bars and sidewalk cafés where the better-off locals come to eat, the white people come to feel hip and some of those condos in the new high-rise buildings go for two and a half mil.

All you need to know about this part of Harlem now, Malone thinks, is that there’s a Banana Republic next to the Apollo Theater. There are the gods of place and the gods of commerce, and if you have to bet who’s going to win out, put your money on money every time.

Farther uptown and in the projects it’s still the ghetto.

Malone crosses 125th and passes the Red Rooster, where Ginny’s Supper Club resides in the basement.

There are less famous shrines, nonetheless sacred to Malone.

He’s attended funerals at Bailey’s, bought pint bottles at Lenox Liquors, been stitched up in the E-room at Harlem Hospital, played hoops by the Big L mural in Fred Samuel Playground, ordered food through the bulletproof glass at Kennedy Fried Chicken. Parked along the street and watched the kids dance, smoked weed on a rooftop, watched the sun come up from Fort Tryon Park.

Now more dead gods, ancient gods—the old Savoy Ballroom, the site of the Cotton Club, both gone long before Malone’s time, ghosts from the last Harlem Renaissance haunting this neighborhood with the image of what it once was and can never be again.

But Lenox is alive.

It actually throbs from the IRT subway line that runs directly underneath its entire length. Malone used to ride the #2 train, the one they called “The Beast” back then.

Now it’s Black Star Music, the Mormon Church, African American Best Food. When they get to the end of Lenox, Malone says, “Go around the block.”

Phil Russo, behind the wheel, turns left onto 147th and drives around the block, down Seventh Avenue and then another left onto 146th, and cruises past an abandoned tenement the owner gave back to the rats and the roaches, chasing the people out in the hope that some junkie cooking up will burn it down and he can collect the insurance and then sell the lot.

Win-win.

Malone scans for sentries or some cops cooping in a radio car, bagging a little sleep on the graveyard shift. A sole lookout stands outside the door. Green bandanna, green Nikes with green shoelaces make him a Trinitario.

Malone’s crew has been watching the heroin mill on the second floor all summer. The Mexicans truck the smack up and deliver it to Diego Pena, the Dominican in charge of NYC. Pena breaks it down from kilos into dime bags and distributes it to the Domo gangs, the Trinitarios and DDP (Dominicans Don’t Play), and then to the black and PR gangs in the projects.

The mill is fat tonight.

Fat with money.

Fat with dope.

“Gear up,” Malone says, checking the Sig Sauer P226 in the holster on his hip. A Beretta 8000D Mini-Cougar rests in a second holster in the small of his back just below the new ceramic-plate vest.

He makes the whole crew wear vests on a job. Big Monty complains his is too tight, but Malone tells him it’s a looser fit than a coffin. Bill Montague, a.k.a. Big Monty, is old school. On his head, even in summer, is his trademark trilby, with its stingy brim and a red feather on the left side. His concession to the heat is an XXXL guayabera shirt over khaki slacks. An unlit Montecristo cigar perches in the corner of his mouth.

A Mossberg 590 pump-action 12-gauge shotgun with a twenty-inch barrel loaded with powdered ceramic rounds sits at Phil Russo’s feet by his high-polished red leather shoes with the skinny guinea toes. The shoes match his hair—Russo is that rare redheaded Italian and Malone jokes that there must have been a bogtrotter in the woodpile. Russo answers that’s impossible because he isn’t an alcoholic and he don’t need a magnifying glass to find his own dick.

Billy O’Neill carries an HK MP5 submachine gun, two flashbang grenades and a roll of duct tape. Billy O’s the youngest of the crew, but he has talent, street smarts and moves.

Guts, too.

Malone knows Billy ain’t gonna cut and run, ain’t gonna freeze or hesitate to pull the trigger, if he needs to. If anything, it’s the opposite—Billy might be a little too quick to go. Got that Irish temper along with the Kennedy good looks. Got some other Kennedy-esque attributes, too. The kid likes women and women like him back.

Tonight, the crew is going in heavy.

And high.

You go up against narcos who are jacked on coke or speed, it helps to be pharmacologically even with them, so Malone pops two “go-pills”—Dexedrine. Then he slips on a blue windbreaker with NYPD stenciled in white and flips the lanyard with his shield over his chest.

Russo orbits the block again. Coming back around on 146th, he hits the gas, races up to the mill and slams the brakes. The lookout hears the tires squeal but turns around too late—Malone’s out the door before the car stops. He shoves the lookout face-first into the wall and sticks the barrel of the Sig against his head.

“Cállate, pendejo,” Malone says. “One sound, I’ll splatter you.”

He kicks the lookout’s feet out from under him and puts him on the ground. Billy is already there—he duct-tapes the lookout’s hands behind him and then slaps a strip over his mouth.

Malone’s crew press themselves against the wall of the building. “We all stay sharp,” Malone says, “we all go home tonight.”

The Dex starts to kick in—Malone feels his heart race and his blood get hot.

It feels good.

He sends Billy O up to the roof to come down the fire escape and cover the window. The rest go in and head up the stairs. Malone first, the Sig in front of him, ready. Russo behind him with the shotgun, then Monty.

Malone don’t worry about his back.

A wooden door blocks the top of the stairs.

Malone nods at Monty.

The big man steps up, jams the Rabbit between the door and the sill. Sweat pops on his forehead and runs down his dark skin as he presses the handles of the tool together and cracks the door open.

Malone steps through, swings his pistol in an arc, but no one’s in the hallway. Looking to the right, he sees the new steel door at the end of the hall. Machata music plays from a radio inside, voices in Spanish, the whir of coffee grinders, the clack of a money counter.

And a dog barking.

Fuck, Malone thinks, all the narcos got ’em now. Just like every chick on the East Side has a yapping little Yorkie in her handbag these days, the slingers got pit bulls. It’s a good idea—the spooks are scared shitless of dogs and the chicas working in the mills won’t risk getting their faces chewed off for stealing.

Malone worries about Billy O because the kid loves dogs, even pit bulls. Malone learned this back in April when they hit a warehouse over by the river and three pit bulls were trying to jump through the chain-link fence to rip their throats out but Billy O, he just couldn’t bring himself to pop them or let anyone else do it, so they had to go all the way around the back of the building, up the fire escape to the roof and then down the stairs.

It was a pain in the ass.

Anyway, the pit bull has made them but the Domos haven’t. Malone hears one of them yell, “Cállate!” and then a sharp whack and the dog shuts up.

But the Hi-Guard steel security door is a problem.

The Rabbit ain’t gonna crack it.

Malone gets on the radio. “Billy, you in place?”

“Born in place, bro.”

“We’re gonna blow the door,” Malone says. “When it goes, you toss in a flashbang.”

“You got it, D.”

Malone nods to Russo, who aims at the door’s hinges and fires two blasts. The ceramic powder explodes faster than the speed of sound and the door comes down.

Women, naked save for plastic gloves and hairnets, bolt for the window. Others crouch under tables as money-counting machines spit cash onto the floor like slot machines paying off with paper.

Malone yells, “NYPD!”

He sees Billy through the window to his left.

Doing exactly shit, just staring through the window. Jesus Christ, throw the grenade.

But Billy doesn’t.

The fuck’s he waiting for?

Then Malone sees it.

The pit bull’s got puppies, four of them, curled up in a ball behind her as she runs to the end of her metal chain, snapping and growling to protect them.

Billy doesn’t want to hurt the puppies.

Malone yells through the radio. “Goddamn it, do it!”

Billy looks through the window at him, then he kicks in the glass and lobs the grenade in.

But he throws it short, to avoid the goddamn dogs.

The concussion shatters the rest of the glass, spraying shards into Billy’s face and neck.

Bright, blinding white light—screams, yells.

Malone counts to three and goes in.

Chaos.

A Trini staggers, one hand to his blinded eyes, the other shooting a Glock as he moves toward the window and the fire escape. Malone hits him with two rounds in the chest and he topples into the window. A second gunman aims at Malone from beneath a counting table but Monty hits him with a blast from his .38 and then a second one to make sure he’s DOA.

They let the women get out the window.

“Billy, you okay?” Malone asks.

Billy O’s face looks like a Halloween mask.

Gashes on his arms and legs.

“I been cut worse in hockey games,” he says, laughing. “I’ll get stitched up when we’re done here.”

Money’s everywhere, in stacks, in the machines, spilled on the floor. Heroin is still in coffee grinders where it was being cut.

But that’s the small shit.

La caja—the trap—a large hole carved into the wall, is open.

Stacked, floor to ceiling, with bricks of heroin.

Diego Pena sits calmly at a table. If the deaths of two of his guys bother him, it doesn’t show on his face. “Do you have a warrant, Malone?”

“I heard a woman scream for help,” Malone says.

Pena smirks.

Well-dressed motherfucker. Gray Armani suit worth two large, the gold Piguet watch on his wrist five times that.

Pena notices. “It’s yours. I have three more.”

The pit bull barks wildly, straining against her chain.

Malone is looking at the heroin.

Stacks of it, vacuum wrapped in black plastic.

Enough H to keep the city high for weeks.

“I’ll save you the trouble of counting,” Pena says. “One hundred kilos even. Mexican cinnamon heroin—‘Dark Horse’—sixty percent pure. You can sell it for a hundred thousand dollars a kilo. The cash you’re seeing should amount to another five million. You take the drugs and the money. I get on a plane to the Dominican, you never see me again. Think about it—when’s the next time you can make fifteen million dollars for turning your back?”

And we all go home tonight, Malone thinks.

He says, “Take your gun out. Slow.”

Pena slowly reaches into his jacket for his pistol.

Malone shoots him twice in the heart.

Billy O squats and picks up a kilo. Slicing it open with his K-bar, he dips a small vial into the heroin, gets a pinch and dumps it into a plastic pouch he takes from his pocket. He crushes the vial inside the test bag and waits for the color to change.

It turns purple.

Billy grins. “We’re rich!”

Malone says, “Hurry the fuck up.”

There’s the sound of a pop as the pit bull breaks the chain and lunges toward him. Billy falls back, throwing the kilo into the air. It mushroom-clouds and then falls like a snow shower into his open wounds.

Another blast as Monty kills the dog.

But Billy’s flat on the floor. Malone sees him go rigid, then his legs start to spasm, jerking uncontrollably as the heroin speeds through his bloodstream.

His feet pound on the floor.

Malone kneels beside him, holds him in his arms.

“Billy, no,” Malone says. “Hold on.”

Billy looks up at him with empty eyes.

His face is white.

His spine jerks like an uncoiling spring.

Then he’s gone.

Freakin’ Billy, beautiful young Billy O, as old now as he’s ever gonna get.

Malone hears his own heart crack, and then dull explosions and at first he thinks he’s been shot, but he doesn’t see any wounds so then he thinks it’s his head blowing up.

Then he remembers.

It’s the Fourth of July.

PART 1 (#ulink_d4d102f3-fc57-5676-81c1-460ba6ed61d8)

(#ulink_d4d102f3-fc57-5676-81c1-460ba6ed61d8)

Welcome to da jungle, this is my home,

The birth of the blues, the birth of the song.

—CHRIS THOMAS KING, “WELCOME TO DA JUNGLE”

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_864de6f3-8a27-53f1-96b2-5e497bc5b6bc)

Harlem, New York City

Christmas Eve

Noon.

Denny Malone pops two go-pills and steps into the shower.

He just got up after a midnight-to-eight and needs the uppers to get him going. Tilting his face toward the showerhead, he lets the sharp needles sting his skin until it hurts.

He needs that, too.

Tired skin, tired eyes.

Tired soul.

Malone turns around and indulges in the hot water pounding on the back of his neck and shoulders. Running down the tattooed sleeves of his arms. It feels good, he could stand there all day, but he has things to do.

“Time to move, ace,” he tells himself.

You have responsibilities.

He gets out, dries off, wraps the towel around his waist.

Malone is six two and solid. Thirty-eight now, he knows he has a hard look to him. It’s the tats on the broad forearms, the heavy stubble even when he shaves, the short-cropped black hair, the don’t-fuck-with-me blue eyes.

It’s the broken nose, the small scar over the left side of his lip. What can’t be seen are the bigger scars on his right leg—his Medal of Valor scars for being stupid enough to get himself shot. That’s the NYPD, though, he thinks. They give you a medal for being stupid, take your badge for being smart.

Maybe the badass look helps him stay out of the physical confrontations, which he does try to avoid. For one thing, it’s more professional to talk your way through. For another, any fight is going to get you hurt—even if it’s just your knuckles—and he doesn’t like getting his clothes messed up rolling around in God only knows what nasty shit is down there on the concrete.

He’s not so much on the weights, so he hits the heavy bag and does the running, usually early morning or late afternoon depending on work, through Riverside Park because he likes the open view of the Hudson, Jersey across the river and the George Washington Bridge.

Now Malone goes into the small kitchen. There’s a little coffee left from when Claudette got up, and he pours a cup and puts it into the microwave.

She’s pulling a double at Harlem Hospital, just four blocks away on Lenox and 135th, so another nurse can spend time with family. With any luck, he’ll see her later tonight or early in the morning.

Malone doesn’t care that the coffee is stale and bitter. He’s not after a quality experience, just a caffeine kick to jump-start the Dexedrine. Can’t stand the whole gourmet coffee bullshit anyway, standing in line behind some millennial asshole taking ten minutes to order a perfect latte so he can take a selfie with it. Malone dumps in some cream and sugar, like most cops do. They drink too much of it, so the milk helps soothe their stomachs while the sugar gives them a boost.

An Upper West Side doctor writes Malone scrip for anything he wants—Dex, Vicodin, Xanax, antibiotics, whatever. A couple of years ago, the good doc—and he is a good guy, with a wife and three kids—had a little something on the side who decided to blackmail him when he decided to break it off.

Malone had a talk with the girl and explained things to her. Handed her a sealed envelope with $10K and told her that was it. She should never contact the doc again or Malone would put her in the House of D where she’d be giving up her overvalued cooch for an extra spoonful of peanut butter.

Now the grateful doctor writes him scrip but half the time just gives him free samples. Every little bit helps, Malone thinks, and anyway, it’s not like he could have speed or pain pills show up on his medical records if he got them through his insurance.

He doesn’t want to phone Claudette and bother her at work, but texts to let her know that he didn’t sleep through the alarm and to ask how her day is going. She texts back, Xmas crazy but OK.

Yeah, Christmas Crazy.

Always crazy in New York, Malone thinks.

If it ain’t Christmas Crazy, it’s New Year’s Eve Crazy (drunks), or Valentine’s Day Crazy (domestic disputes skyrocket and the gays get into bar fights), St. Paddy’s Crazy (drunk cops), Fourth of July Crazy, Labor Day Crazy. What we need is a holiday from the holidays. Just take a year off from any of them, see how it works out.

It probably wouldn’t, he thinks.

Because you still got Everyday Crazy—Drunk Crazy, Junkie Crazy, Crack Crazy, Meth Crazy, Love Crazy, Hate Crazy and, Malone’s personal favorite, plain old Crazy Crazy. What the public at large doesn’t understand is that the city’s jails have become its de facto mental hospitals and detox centers. Three-quarters of the prisoners they check in test positive for drugs or are psychotic, or both.

They belong in hospitals but don’t have the insurance.

Malone goes into the bedroom to get dressed.

Black denim shirt, Levi’s jeans, Doc Marten boots with steel-reinforced toes (the better to kick in doors), a black leather jacket. The quasi-official Irish-American New York street uniform, Staten Island division.

Malone grew up there, his wife and his kids still live there, and if you’re Irish or Italian from Staten Island, your career choices are basically cop, fireman or crook. Malone took door number one, although he has a brother and two cousins who are firefighters.

Well, his brother, Liam, was a firefighter, until 9/11.

Now he’s a twice-annual trip to Silver Lake Cemetery to leave flowers, a pint of Jameson’s and a report on how the Rangers are doing.

Usually shitty.

They always used to joke that Liam was the black sheep of the family, becoming a “hose-monkey”—a firefighter—instead of a cop. Malone used to measure his brother’s arms to see if they’d gotten any longer lugging all that shit around and Liam would shoot back that the only thing a cop would heft up a flight of stairs was a bag of doughnuts. And then there was the fictional competition between them about who could steal more—a firefighter on a domestic blaze or a cop on a burglary call.

Malone loved his little brother, looked after him all those nights the old man wasn’t home, and they watched the Rangers together on Channel 11. The night the Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1994 was one of the happiest nights in Malone’s life. Him and Liam in front of the TV set, on their knees the last minute of the game when the Rangers were holding on to a one-goal lead by their fingernails and Craig MacTavish—God bless Craig MacTavish—kept getting the puck down deep in the Canucks’ zone and time finally ran out and the Rangers won the series 4–3 and Denny and Liam hugged each other and jumped up and down.

And then Liam was gone, just like that, and it was Malone who had to go tell their mother. She was never the same after that and died just a year later. The doctors said it was cancer but Malone knew she was another victim of 9/11.

Now he clips his holster with the regulation Sig Sauer onto his belt.

A lot of cops like the shoulder holster but Malone thinks it’s just an extra move to get your hand up there and he prefers his weapon where his hand already is. He clips his off-duty Beretta to the back of his waistband, where it nestles into the small of his back. The SOG knife goes into his right boot. It’s against regs and illegal as shit, but Malone doesn’t care. He could be in a situation some skels take his guns and then what’s he supposed to pull, his dick? He ain’t going down like a bitch, he’s going out slashing and stabbing.

And anyway, who’s going to bust him?

A lot of people, you dumb donkey, he tells himself. These days, every cop’s got a bull’s-eye on his back.

Tough times for the NYPD.

First, there’s the Michael Bennett shooting.

Michael Bennett was a fourteen-year-old black kid who was shot to death by an Anti-Crime cop in Brownsville. The classic case: nighttime, he looked hinky, the cop—a newbie named Hayes—told him to stop and he didn’t. Bennett turned, reached into his waistband and pulled out what Hayes thought was a gun.

The newbie emptied his weapon into the kid.

Turned out it wasn’t a gun, it was a cell phone.

The community, of course, was “outraged.” Protests teetered on the edge of riots, the usual celebrity ministers, lawyers and social activists performed for the cameras, the city promised a complete investigation. Hayes was placed on administrative leave pending the result of the investigation, and the hostile relationship between blacks and the police got even worse than it already was.

The investigation is still “ongoing.”

And it came behind the whole Ferguson thing, and Cleveland and Chicago, Freddie Gray down in Baltimore. Then there was Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Philando Castile in Minnesota, on and on.

Not that the NYPD didn’t have its own cops killing unarmed black men—Sean Bell, Ousmane Zongo, George Tillman, Akai Gurley, David Felix, Eric Garner, Delrawn Small … And now this rookie had to go and shoot young Michael Bennett.

So you got Black Lives Matter up your ass, every citizen a journalist with a cell-phone camera at the ready, and you go to work each day with the whole world thinking you’re a murdering racist.

Okay, maybe not everybody, Malone admits, but it’s definitely different now.

People look at you different.

Or shoot at you.

Five cops gunned down by a sniper in Dallas. Two cops in Las Vegas shot to death as they sat at a restaurant eating lunch. Forty-nine officers murdered in the United States in the past year. One of them, Paul Tuozzolo, in the NYPD, and the year before the Job lost Randy Holder and Brian Moore. There have been too many over the years. Malone knows the stats: 325 gunned down, 21 stabbed, 32 beaten to death, 21 deliberately run over by cars, 8 blown up in explosions, and none of that counts the guys dying from the shit they sucked down on 9/11.

So yeah, Malone carries something extra, and yeah, he thinks, there’d be any number of people ready to string you up, they found you with illegal weapons, not the least of which would be the cop-hating CCRB, which Phil Russo insists stands for “Cunts, Cocksuckers, Rats and Ballbusters,” but is actually the Civilian Complaint Review Board, the mayor’s chosen stick for beating up on his police force when he needs to deflect attention from his own scandals.

So the CCRB would hang you, Malone thinks, IAB—the goddamn Internal Affairs Bureau—would sure as shit hang you, even your own boss would cheerfully put a noose around your neck.

Now Malone sucks it up to call Sheila. What he doesn’t want is a fight, what he doesn’t want is the question, Where are you calling from? But that’s what he gets when his estranged wife answers the phone. “Where are you calling from?”

“The city,” Malone says.

To every Staten Islander, Manhattan is and will always be “the city.” He doesn’t get more specific than that, and fortunately she doesn’t press him on it. Instead she says, “This better not be a call telling me you can’t make it tomorrow. The kids will be—”

“No, I’m coming.”

“For presents?”

“I’ll get there early,” Malone says. “What’s a good time?”

“Seven thirty, eight.”

“Okay.”

“You on a midnight?” she asks, a tinge of suspicion in her tone.

“Yeah,” Malone says. Malone’s team is on the graveyard, but it’s a technicality—they work when they decide to work, which is when the cases tell them to. Drug dealers work regular shifts so their customers know when and where to find them, but drug traffickers work their own hours. “And it isn’t what you think.”

“What do I think?” Sheila knows that every cop with an IQ over 10 and a rank over rookie can get Christmas Eve off if he wants, and a midnight tour is usually just an excuse to get drunk with your buddies or bang some whore, or both.

“Don’t get it twisted, we’re working on something,” Malone says, “might break tonight.”

“Sure.”

Sarcastic, like. The hell she thinks pays for the presents, the kids’ braces, her spa days, her girls’ nights out? Every guy on the Job relies on overtime to pay the bills, maybe even get a little ahead. The wives, even the ones you’re separated from, gotta understand. You’re out there busting your hump, all the time.

“You spending Christmas Eve with her?” Sheila asks.

So close, Malone thinks, to getting away. And Sheila pronounces it “huh.” You spending Christmas Eve with huh?

“She’s working,” Malone says, dodging the question like a skel. “So am I.”

“You’re always working, Denny.”

Ain’t that the large truth, Malone thinks, taking that as a good-bye and clicking off. They’ll put it on my freakin’ headstone: Denny Malone, he was always working. Fuck it—you work, you die, you try to have a life somewhere in there.

But mostly you work.

A lot of guys, they come on the Job to do their twenty, pull the pin, get their pension. Malone, he’s on the Job because he loves the job.

Be honest, he tells himself as he walks out of the apartment. You had to do it all over again you wouldn’t be nothin’ but a New York City police detective.

The best job in the whole freakin’ world.

Malone pulls on a black wool beanie because it’s cold out there, locks up the apartment and goes down the stairs onto 136th. Claudette picked the place because it’s a short walk to her work, and near the Hansborough Rec Center, which has an indoor pool where she likes to swim.

“How can you swim in a public pool?” Malone has asked her. “I mean, the germs floating around in there. You’re a nurse.”

She laughed at him. “Do you have a private pool I don’t know about?”

He walks west on 136th out to Seventh Avenue, a.k.a. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, past the Christian Science Church, United Fried Chicken and Café 22, where Claudette doesn’t like to eat because she’s afraid she’ll get fat and he doesn’t like to eat because he’s afraid they’ll spit in his food. Across the street is Judi’s, the little bar where he and Claudette will get a quiet drink on the odd occasions their downtimes coincide. Then he crosses ACP at 135th and walks past the Thurgood Marshall Academy and an IHOP where Small’s Paradise used to be down in the basement.

Claudette, who knows about these things, told Malone that Billie Holiday had her first audition there and that Malcolm X was a waiter there during World War II. Malone was more interested that Wilt Chamberlain owned the place for a while.

City blocks are memories.

They have lives and they have deaths.

Malone was still wearing the bag, riding a sector car, when a mook raped a little Haitian girl on this block back in the day. This was the fourth girl this animal had done, and every cop in the Three-Two was looking for him.

The Haitians got there before the cops did, found the perp still on the rooftop and tossed him off into the back alley.

Malone and his then partner caught the call and walked into the alley where Rocky the Non-Flying Squirrel was lying in a spreading pool of his own blood, with most of the bones in his body broken because nine floors is a long way to fall.

“That’s the man,” one of the local women told Malone at the edge of the alley. “The man who raped those little girls.”

The EMTs knew what was what, and one of them asked, “He dead yet?”

Malone shook his head and the EMTs lit up cigarettes and leaned on the ambulance smoking for a good ten minutes until they went in with a stretcher and came back out with the word to call the medical examiner.

The ME pronounced the cause of death as “massive blunt trauma with catastrophic and fatal bleeding,” and the Homicide guys who showed up accepted Malone’s account that the guy had jumped out of guilt over what he’d done.

The detectives wrote it off as a suicide, Malone got a lot of stroke from the Haitian community, and most important, no little girls had to testify in court with their rapist sitting there staring at them and some dirtbag defense attorney trying to make them look like liars.

It was a good result but shit, he thinks, we did that today we’d go to jail, we got caught.

He keeps walking south, past St. Nick’s.

A.k.a. “The Nickel.”

The St. Nicholas Houses, a baker’s dozen of fourteen-story buildings straddled by Adam Clayton Powell and Frederick Douglass Boulevards from 127th to 131st, make up a good part of Malone’s working life.

Yeah, Harlem has changed, Harlem has gentrified, but the projects are still the projects. They sit like desert islands in a sea of new prosperity and what makes the projects is what’s always made the projects—poverty, unemployment, drug slinging and gangs. Mostly good people inhabit St. Nick’s, Malone believes, trying to live their lives, raise their kids against tough odds, do their day-to-day, but you also have the hard-core thugs and the gangs.

Two gangs dominate action in St. Nick’s—the Get Money Boys and Black Spades. GMB has the north projects, the Spades the south, and they live in an uneasy peace enforced by DeVon Carter, who controls most of the drug trafficking in West Harlem.

The border between the gangs is 129th Street, and Malone walks past the basketball courts on the south side of the street.

The gang boys aren’t out there today, it’s too freakin’ cold.

He goes out Frederick Douglass past the Harlem Bar-B-Q and Greater Zion Hill Baptist. It was just down the street where he got the rep as both a “hero cop” and a “racist cop,” neither of which tag is true, Malone thinks.

It was what, six years ago now, he was working plainclothes out of the Three-Three and was having lunch at Manna’s when he heard screaming outside. He went out the door and saw people pointing at a deli across the street and down the block.

Malone called in a 10-61, pulled his weapon and went into the deli.

The robber grabbed a little girl and held a gun to her head.

The girl’s mother was screaming.

“Drop your gun,” the robber yelled at Malone, “or I’ll kill her! I will!”

He was black, junkie-sick, out of his fucking mind.

Malone kept his gun aimed at him and said, “The fuck do I care you kill her? Just another nigger baby to me.”

When the guy blinked, Malone put one through his head.

The mother ran forward and grabbed her little girl. Held her tight against her chest.

It was the first guy Malone ever killed.

A clean shooting, no trouble with the shooting board, although Malone had to ride a desk until it was cleared and had to go see the departmental shrink to find out if he had PTSD or something, which it turned out he didn’t.

Only trouble was, the store clerk got the whole thing on his cell-phone camera and the Daily News ran with the headline JUST ANOTHER N****R BABY TO ME with a photo of Malone with the log line “Hero Cop a Racist.”

Malone got called into a meeting with his then captain, IAB and a PR flack from One Police, who asked, “‘Nigger baby’?”

“I had to be sure he believed me.”

“You couldn’t have chosen different words?” the flack asked.

“I didn’t have a speechwriter with me,” Malone said.

“We’d like to put you up for a Medal of Valor,” said his captain, “but …”

“I wasn’t going to put in for one.”

To his credit, the IAB guy said, “May I point out that Sergeant Malone saved an African American life?”

“What if he’d missed?” the PR flack asked.

“I didn’t,” Malone said.

Truth was, though, he’d thought the same thing. Didn’t tell it to the shrink, but he had nightmares about missing the skel and hitting the little girl.

Still does.

Shit, he even has nightmares about hitting the skel.

The clip ran on YouTube and a local rap group cut a song called “Just Another Nigger Baby,” which got a few hundred thousand hits. But on the plus side, the little girl’s mother came to the house with a pan of her special jalapeño cornbread and a handwritten thank-you card and sought Malone out.

He still has the card.

Now he crosses St. Nicholas and Convent and walks down 127th until it merges where 126th takes a northwest angle. He crosses Amsterdam and walks past Amsterdam Liquor Mart, which knows him well, Antioch Baptist Church, which doesn’t, past St. Mary’s Center and the Two-Six House and into the old building that now houses the Manhattan North Special Task Force.

Or, as it’s known on the street, “Da Force.”

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_57cd81c0-8610-5667-88b3-fc176188c51f)

The Manhattan North Special Task Force was half Malone’s idea to begin with.

A lot of bureaucratic verbiage describes their mission, but Malone and every other cop on Da Force know exactly what their “special task” is—

Hold the line.

Big Monty put it somewhat differently. “We’re landscapers. Our job is to keep the jungle from growing back.”

“The fuck are you talking about?” Russo asked.

“The old urban jungle that was Manhattan North has been mostly cut down,” Monty said, “to make room for a cultivated, commercial Garden of Eden. But there are still patches of jungle—to wit, the projects. Our job is to keep the jungle from reclaiming paradise.”

Malone knows the equation—real estate prices rise as crime falls—but he could give a shit about that.

His concern was the violence.

When Malone first came on the Job, the “Giuliani Miracle” had transformed the city. Police commissioners Ray Kelly and Bill Bratton had used “broken windows” theory and CompStat technology to reduce street crime to an almost negligible level.

Nine/eleven changed the department’s focus from anticrime to antiterrorism, but street violence continued to fall, the murder rate plummeted and the Upper Manhattan “ghetto” neighborhoods of Harlem, Washington Heights and Inwood started to revive.

The crack epidemic had largely reached its tragic Darwinian conclusion, but the problems of poverty and unemployment—drug addiction, alcoholism, domestic violence and gangs—hadn’t gone away.

To Malone, it was like there were two neighborhoods, two cultures grouped around their respective castles—the shiny new condo towers and the old project high-rises. The difference was that the people in power were now literally invested.

Back in the day, Harlem was Harlem, and rich white people “just didn’t go there” unless they were slumming or looking for a cheap thrill. The murder rate was high, muggings and armed robberies and all the violence that came with drugs was high, but as long as blacks were raping, robbing and murdering other blacks, who gave a fuck?

Well, Malone.

Other cops.

That’s the bitter, brutal irony about police work.

That’s the root of the love-hate relationship cops have with the community and the community with the police.

The cops see it every day and every night.

The hurt, the dead.

People forget that the cops see first the victims and then the perpetrators. From the baby some crack whore dropped into the bathtub to the kid beat into stupefaction by his mother’s eighteenth live-in boyfriend, the old lady whose hip gets broken when a purse snatcher knocks her to the sidewalk, the fifteen-year-old wannabe dope slinger gunned down on the corner.

The cops feel for the vics and hate the perps, but they can’t feel too much or they can’t do their jobs and they can’t hate too much or they’ll become the perps. So they develop a shell, a “we hate everybody” attitude force field around themselves that everyone can feel from ten feet away.

You gotta have it, Malone knows, or this job kills you, physically or psychologically. Or both.

So you feel for the old lady victim, but hate the mutt who did it; you sympathize with the storeowner who just got robbed, but despise the mope who robbed him; you feel bad for the black kid who got shot, but hate the nigger who shot him.

The real problem, Malone thinks, is when you start hating the victim, too. And you do—it just wears you down. Their pain becomes yours, the responsibility for their suffering weighs on your shoulders—you didn’t do enough to protect them, you were in the wrong place, you didn’t catch the perp earlier.

You start blaming yourself and/or you start blaming the victim—why are they so vulnerable, why so weak, why do they live in those conditions, why do they join gangs, sling drugs, why do they have to shoot each other over nothing … why are they such fucking animals?

But Malone still fucking cares.

Doesn’t want to.

But does.

Tenelli ain’t happy.

“Why does this dick have to bring us in Christmas Eve?” she asks Malone as he comes through the doors.

“I think you answered your own question,” Malone says.

Captain Sykes is a dick.

Speaking of dicks, the prevailing opinion is that Janice Tenelli has the biggest one on Da Force. Malone has watched the detective repeatedly kick a heavy bag right where the nuts would be and it made his own package shrivel.

Or expand. Tenelli has a mane of thick black hair, a won’t-quit rack and a face straight out of an Italian movie. Every guy on Da Force would like to have sex with her, but she’s made it very clear she don’t shit where she eats.

All evidence to the contrary, Russo insists on insisting, to Tenelli’s face, that the married mother of two is a lesbian.

“Because I won’t fuck you?” she asked.

“Because it’s my dearest-held fantasy,” Russo said. “You and Flynn.”

“Flynn is a lesbian.”

“I know.”

“Knock yourself out,” Tenelli said, jerking her wrist.

“I haven’t wrapped a single gift,” she tells Malone now, “the in-laws are coming over tomorrow, I have to sit and listen to this guy make speeches? Come on, straighten him out, Denny.”

She knows what they all know—Malone was here before Sykes came and he’ll be here after he leaves. The joke is that Malone would take the lieutenant’s exam except he couldn’t take the pay cut.

“Sit and listen to his speech,” Malone says, “then go home and make … What are you making?”

“I dunno, Jack does all the cooking,” she says. “Prime rib, I think. You doing your annual Turkey Run this year?”

“Hence the term ‘annual.’”

“Right.”

They’re filing into the briefing room when Malone spots Kevin Callahan out of the corner of his eye. The undercover—tall, skinny, long red hair and beard—looks baked out of his mind.

Cops, undercover or otherwise, aren’t supposed to do dope, but how else are they supposed to make buys and not get made? So sometimes it turns into a habit. A lot of guys come off undercover straight into rehab and their careers are fucked.

Occupational hazard.

Malone walks over, grabs Callahan by the elbow and walks him out the door. “Sykes sees you, he’ll piss-test you straightaway.”

“I have to log in.”

“I’ll sign you out on a surveillance,” Malone says. “You get asked, you were up at the Ville for me.”

The Manhattan North Special Task Force house is conveniently located between two projects—Manhattanville, just across the street uptown, and Grant, across 125th Street below them.

Come the revolution, Malone thinks, we’re surrounded.

“Thanks, Denny.”

“Why are you still standing here?” Malone asks. “Get your ass up to the Ville. And, Callahan, you mess up again, I’ll piss you myself.”

He goes back in and takes a folding metal chair in the briefing room next to Russo.

Big Monty turns around in his chair and looks at them. He holds a steaming cup of tea, which he manages to sip even though his unlit cigar is jammed in the corner of his mouth. “I just want to enter my official protest regarding this afternoon’s activities.”

“Noted,” Malone says.

Monty turns back around.

Russo grins. “He ain’t happy.”

He is unhappy, Malone thinks, happily. It’s good to shake the otherwise unflappable Big Man up every once in a while.

Keeps him fresh.

Raf Torres walks in with his team—Gallina, Ortiz and Tenelli. Malone doesn’t like that Tenelli is with Torres, because he likes Tenelli and thinks that Torres is a piece of shit. He’s a big motherfucker, Torres, but to Malone he looks like a big, brown, pockmarked Puerto Rican toad.

Torres nods to Malone. It somehow manages to be a gesture of acknowledgment, respect and challenge at the same time.

Sykes walks in and stands behind the lectern like a professor. He’s young for a captain, but then again he has rabbis at the Puzzle Palace, brass looking out for his interests.

And he’s black.

Malone knows that Sykes has been tagged as the next big thing, and that the Manhattan North Special Task Force is a high-profile box for him to tick on his way up.

To Malone he looks like some precocious Republican Senate candidate—very crisp, very clean, his hair cut short. He sure as hell don’t have any tattoos, unless there’s an arrow pointing up his asshole reading This Way to My Brain.

That isn’t fair, Malone thinks, checking himself. The guy’s record is solid, he did some real police work on Major Crimes in Queens and then became the Job’s designated precinct janitor—he cleaned up the Tenth and the Seven-Six, real dumping grounds, and now they’ve moved him here.

To check another box on his sheet? Malone wonders.

Or to clean us up?

In either case, Sykes brought that Queens attitude with him.

Squared away, by the book.

A Queens Marine.

Sykes’s first day on command he had the whole Task Force—fifty-four detectives, undercovers, anticrime guys and uniforms—come in, sat them down and made a speech.

“I know I’m looking at the elite,” Sykes said. “The best of the best. I also know I’m looking at a few dirty cops. You know who you are. Soon, I’ll know who you are. And hear this—I catch any of you taking as much as a free coffee or a sandwich, I’ll have your shield and gun, I’ll have your pension. Now get out, go do your jobs.”

He didn’t make any friends, but he made it clear that he wasn’t there to make friends. And Sykes had also alienated his people by taking a vocal stand against “police brutality,” warning them he wouldn’t tolerate intimidation, beatings, profiling or stop and frisk.

How the fuck does he think we maintain even a semblance of control? Malone thinks, looking at the man now.

The captain holds up a copy of the New York Times.

“‘White Christmas,’” Sykes reads. “‘Heroin Floods the City on the Holidays.’ Mark Rubenstein in the New York Times. And not just one article, he’s doing a series. The New York Times, gentlemen.”

He pauses to let that sink in.

It doesn’t.

Most cops don’t read the Times. They read the Daily News and the Post, mostly for the sports news or the T&A on Page Six. A few read the Wall Street Journal to keep up on their portfolios. The Times is strictly for the suits at One Police and the hacks in the mayor’s office.

But the Times says there’s a “heroin epidemic,” Malone thinks.

Which is only an epidemic, of course, because now white people are dying.

Whites started to get opium-based pills from their physicians—oxycodone, Vicodin, that shit. But it was expensive and doctors were reluctant to prescribe too much for exactly the fear of addiction. So the white folks went to the open market and the pills became a street drug. It was all very nice and civilized until the Sinaloa Cartel down in Mexico made a corporate decision that it could undersell the big American pharmaceutical companies by raising production of its heroin, thereby reducing price.

As an incentive, they also increased its potency.

The addicted white Americans found that Mexican “cinnamon” heroin was cheaper and stronger than the pills and started shooting it into their veins and overdosing.

Malone literally saw it happening.

He and his team busted more bridge-and-tunnel junkies, suburban housewives and Upper East Side madonnas than they could count. More and more of the bodies they’d find slumped dead in alleys were Caucasian.

Which, according to the media, is a tragedy.

Even congressmen and senators pulled their noses out of their donors’ ass cracks long enough to notice the new epidemic and demand that “something has to be done about it.”

“I want you out there making heroin arrests,” Sykes says. “Our numbers on crack cocaine are satisfactory, but our numbers on heroin are subpar.”

The suits love their numbers, Malone thinks. This new “management” breed of cops are like the sabermetrics baseball people—they believe the numbers say it all. And when the numbers don’t say what they want them to, they massage them like Koreans on Eighth Avenue until they get a happy ending.

You want to look good? Violent crime is down.

You need more funding? It’s up.

You need arrests? Send your people out to make a bunch of bullshit busts that will never get convictions. You don’t care—convictions are the DA’s problem—you just want the arrest numbers.

You want to prove drugs are down in your sector? Send your guys on “search and avoid” missions where there aren’t any drugs.

That’s half the scam. The other way to manipulate the numbers is to let officers know they should downgrade charges from felonies to misdemeanors. So you call a straight-up robbery a “petit larceny,” a burglary becomes “lost property,” a rape a “sexual assault.”

Boom—crime is down.

Moneyball.

“There’s a heroin epidemic,” Sykes says, “and we’re on the front lines.”

They must have really cracked Inspector McGivern’s nuts at the CompStat meeting, Malone thinks, and he passed the pain along to Sykes.

So he hands it off to us.

And we’ll pass it down to a bunch of low-level dealers, addicts who sell so they can score, and fill the house with a bunch of arrests so Central Booking will flow with puke from junkies jonesing, and bog down the court dockets with quivering losers pleading out and then going back to jail to score more smack. Come out still addicted, and start the whole cycle all over again.

But we’ll make par.

The suits at One Police can say as much as they want that there are no quotas, but every guy on the Job knows there are. Back in the “broken windows” days, they were writing summonses for everything—loitering, littering, jumping a subway stile, double-parking. The theory was if you didn’t come down on the small stuff, people would figure it was okay to do the big stuff.

So they were out there writing a lot of bullshit C-summonses, which forced a lot of poor people to take time off work they couldn’t afford to go to court to pay fines they couldn’t pay. Some just skipped their court days and got “no-show” warrants, so their misdemeanors escalated to felonies and they were looking at jail time for tossing a gum wrapper on the sidewalk.

It provoked a lot of anger toward the police.

Then there were the 250s.

The stop and frisks.

Which basically meant that if you saw a young black kid on the street, you stopped him and shook him down. It caused a lot of resentment, too, and got a lot of negative media, so we don’t do that anymore, either.

Except we do.

Now the quota that isn’t is heroin.

“Cooperation,” Sykes is saying, “and coordination are what makes us a task force and not just separate entities officed in the same space. So let’s work together, gentlemen, and get this thing done.”

Rah fuckin’ rah, Malone thinks.

Sykes probably doesn’t realize that he’s just given his people contradictory instructions—work their sources and make heroin arrests—doesn’t even get that you work your sources by popping them with drugs and then not arresting them.

They give you information, you give them a pass.

That’s the way it works.

What’s he think, a dealer is going to talk to you out of the goodness of his heart, which he doesn’t have anyway? To be a good citizen? A dealer talks to you for money or drugs, to skate on a charge or to fuck a rival dealer. Or maybe, maybe, because someone is fucking his bitch.

That’s it.

The guys on Da Force don’t look too much like cops. In fact, Malone thinks as he looks around, they look more like criminals.

The undercovers look like junkies or dope slingers—hoodies, baggy pants or filthy jeans, sneakers. Malone’s personal favorite, a black kid called Babyface, hides under a thick hood and sucks on a big pacifier as he looks up at Sykes, knowing the boss isn’t going to say shit about it because Babyface brings home the bacon.

The plainclothes guys are urban pirates. They still have tin shields—not gold—under their black leather jackets, navy peacoats and down vests. Their jeans are clean but not creased, and they prefer Chelsea boots to tennis shoes.

Except “Cowboy” Bob Bartlett, who wears shitkicker boots with skinny toes, “the better to go up a black ass.” Bartlett’s never been farther west than Jersey City, but he affects a redneck drawl and aggravates the shit out of Malone by playing country-western “music” in the locker room.

The “uniforms” in their bags don’t look like your run-of-the-mill cops either. It ain’t what they wear, it’s in their faces. They’re badasses, with the smirks as pinned on as the badges on their chests. These boys are always ready to go, ready to dance, just for the fuck of it.

Even the women have attitudes. There ain’t many of them on Da Force, but the ones who are take no prisoners. You got Tenelli and then there’s Emma Flynn, a hard-drinking (Irish, go figure) party girl with the sexual voracity of a Roman empress. And they’re all tough, with a healthy hatred in their hearts.

The detectives, though, the gold shields like Malone, Russo, Montague, Torres, Gallina, Ortiz, Tenelli, they’re in a different league altogether, “the best of the best,” decorated veterans with scores of major arrests under their belts.

The Task Force detectives aren’t uniforms or plainclothes or undercovers.

They’re kings.

Their kingdoms aren’t fields and castles but city blocks and project towers. Tony Upper West Side neighborhoods and Harlem projects. They rule Broadway and West End, Amsterdam, Lenox, St. Nicholas and Adam Clayton Powell. Central Park and Riverside where Jamaican nannies push yuppies’ kids in strollers and start-up entrepreneurs jog, and trash-strewn playgrounds where the gangbangers ball and sling dope.

We’d better rule, Malone thinks, with a strong hand, because our subjects are blacks and whites, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Haitians, Jamaicans, Italians, Irish, Jews, Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, who all hate each other and who, in the absence of kings, would kill each other more than they already do.

We rule over gangs—Crips and Bloods and Trinitarios and Latin Lords. Dominicans Don’t Play, Broad Day Shooters, Gun Clappin’ Goonies, Goons on Deck (seems to be a theme), From Da Zoo, Money Stackin’ High, Mac Baller Brims. Folk Nation, Insane Gangster Crips, Addicted to Cash, Hot Boys, Get Money Boys.

Then there’s the Italians—the Genovese family, the Lucheses, the Gambinos, the Ciminos—all of which would get totally out of control if they didn’t know there were kings out there who would cut off their heads.

We rule Da Force, too. Sykes thinks he does, or at least pretends to think he does, but it’s the detective kings who really call the shots. The undercovers are our spies, the uniforms our foot soldiers, the plainclothes our knights.

And we didn’t become kings because our daddies were—we took our crowns the hard way, like the old warriors who fought their way to the throne with nicked swords and dented armor and wounds and scars. We started on these streets with guns and nightsticks and fists and nerve and guts and brains and balls. We came up through our hard-won street knowledge, our earned respect, our victories and even our defeats. We earned our reps as tough, strong, ruthless and fair rulers, administering rough justice with tempered mercy.

That’s what a king does.

He hands down justice.

Malone knows it’s important they look the part. Subjects expect their kings to look tight, to look sharp, to wear a little money on their backs and their feet, a little style. Take Montague, for instance. Big Monty dresses like an Ivy League professor—tweedy jackets, vests, knit ties—and the trilby with a small red feather in the band. It goes against the stereotype and it’s scary because the skels don’t know what to make of him, and when he gets them in the room, they think they’re being interrogated by a genius.

Which Monty probably is.

Malone has seen him go into Morningside Park where the old black men play chess, contest five boards at a time and win every one of them.

Then give back the money he just took from them.

Which is also genius.

Russo, he’s old school. Sports a long red-brown leather overcoat, a 1980s throwback that he wears well. Then again, Russo wears everything well, he’s a sharp dresser. The retro overcoat, custom-tailored Italian suits, monogrammed shirts, Magli shoes.

A haircut every Friday, a shave twice a day.

Mobster chic, Russo’s ironic comment on the wiseguys he grew up with and never wanted to be. He went the other way with it; as a cop, he likes to joke, he’s the “white sheep of the family.”

Malone always wears black.

His trademark.

All Da Force detectives are kings, but Malone—with no disrespect intended to our Lord and Savior—is the King of Kings.

Manhattan North is the Kingdom of Malone.

Like with any king, his subjects love him and fear him, revere him and loathe him, praise him and revile him. He has his loyalists and rivals, his sycophants and critics, his jesters and advisers, but he has no real friends.

Except his partners.

Russo and Monty.

His brother kings.

He would die for them.

“Malone? If you have a moment for me?”

It’s Sykes.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_ed19cdd0-5212-5c9f-9b8e-4fc735422ecd)

As I’m sure you know,” Sykes says in his office, “just about everything I said in there was bullshit.”

“Yes, sir,” Malone says. “I was just wondering if you knew it.”

Sykes’s tight smile gets tighter, which Malone didn’t think was possible.

The captain thinks that Malone is arrogant.

Malone doesn’t argue with that.

A cop on these streets, he thinks, you’d better be arrogant. There are people up here, they see you don’t think you’re the shit, they will kill you. They’ll cap you and fuck you in the entry wounds. Let Sykes go out on the streets, let him make the busts, go through the doors.

Sykes doesn’t like it, but he doesn’t like a lot about Detective Sergeant Dennis Malone—his sense of humor, his tat sleeves, his encyclopedic knowledge of hip-hop lyrics. He especially doesn’t like Malone’s attitude, which is basically that Manhattan North is his kingdom and his captain is just a tourist.

Fuck him, Malone thinks.

There’s nothing Sykes can do because last July Malone and his team made the largest heroin bust in the history of New York City. They hit Diego Pena, the Dominican kingpin, for fifty kilos, enough to supply a fix for every man, woman and child in the city.

They also seized close to two million in cash.